Abstract

In Pablo Picasso’s formative period in A Coruña (1891–1895), where he was born as an artist, the child and pre-adolescent who at that time signed himself as Pablo Ruiz, already knowing he was a genius, pursued an intense programme of creative activity while devoting himself to drawing and painting. Making use of his facility for reproducing the world around him in images, he also proved to be an incipient devotee of journalism as an instrument of communication and social awareness, a satirical draughtsman and caricaturist, seeking to give his version of events, in line with the magazines and newspapers of the period, and displaying a critical ability unusual in a child, a committed gaze, not devoid of humour and sarcasm, which prefigures the later Picasso with his progressive views, acute intelligence, meta-ironic approach and support for great causes.

1. Picasso’s Beginnings in the Written Press

There is an increasingly deep-seated consensus among experts that in his formative period in A Coruña (Spain) from 1891 to 1895, between childhood and early adolescence, Pablo Picasso conceived practically all the iconography he would frequently employ over the course of his very lengthy eighty-year artistic career. His most reliable biographers, Josep Palau i Fabre and John Richardson, take it as established that he was born as an artist and developed his aesthetic foundations in A Coruña, in the decisive period of residence during the years mentioned, when his father, José Ruiz Blasco, taught at the Provincial School of Fine Art in that city ([1], p. 229; [2], p. 385). Palau argued that by the time Picasso left A Coruña he had become sentimentally and artistically mature and that his production at that time suffices to show us that we were dealing with an extraordinary case, because here we had seen the birth of an exceptional academic draftsman, a caricaturist and caustic chronicler, a portraitist and a landscape artist ([3], p. 68, p. 70). And Richardson places Picasso’s birth as a painter in the portraits from that period, which the artist himself often valued higher than the works from his Blue and Pink periods (“These Corunna portraits are the first Picassos that can be taken seriously as works of art as opposed to juvenilia”) ([4], p. 52). We ought to consider these works on canvas as his first adult creations, in which he focuses on the human figure to capture the vicissitudes of life and as Palau said, “éste ya es el Picasso de siempre; el que, en formas distintas, reaparecerá en todos los meandros de su carrera” [this is the eternal Picasso; the one which, in various forms, would reappear in all the meanders of his career] ([3], p. 60).

It is a period that has been well documented in recent years by the A Coruña journalists and researchers Ángel Padín [5,6] and Rubén Ventureira and Elena Pardo [7], in historiographical terms, and from an aesthetic perspective by the exhibition El primer Picasso. A Coruña, 2015 [Picasso’s Early Period. A Coruña, 2015] [8] curated by the conservator of Museu Picasso in Barcelona, Malén Gual, and the essays of Antón Castro [9,10], as well as the extensive archival and visual work of Enrique Mallen [11]1, all of whom stress the decisive importance of A Coruña in the artist’s future.

While living there, between 1893 and 1894, wanting to communicate with his family in Malaga through drawing, the medium in which he was most proficient ([13], p. 276),2 Picasso produced the illustrated newspapers or magazines Azul y Blanco and La Coruña, with the clear intention of documenting for his relatives what it was like living in the city and in Galicia, trying, through his still naive perceptions, to reflect the local customs, sociological particularities and changing weather conditions, and also including personal anecdotes and his viewpoints on the things closest to him, ranging from what happened in one of his classes to events in what was then a small city with just over 40,000 inhabitants: private and general information to let them know how his life was going in this provincial capital, so different from Malaga, and what it was like in the place that was now home to himself, his father, his mother and his sisters. Of these little newspapers, made by his childish hands and already shown repeatedly in exhibitions [14,15], we have some sheets preserved in museums in Barcelona and Paris, thanks to a donation from the artist in the first case and a settlement of death duties in the second.

As is rightly pointed out by Anne Baldassari, former director of the Picasso Museum in Paris and the person who has most extensively studied his work in the field of journalism [16], the young Pablo, in his multiple perspective, brings a special shrewdness to the task of capturing reality in that dual dimension: through images that illustrate it with journalistic subtlety and through the simultaneous use of writing. In fact, this precocious experience of the little newspapers he published in the city of A Coruña, Azul y Blanco and La Coruña, offers us the first evidence of the extremely close attention Picasso paid to print media, an interest that was to remain active throughout his life, both as a reader and as a participant in publishing and illustrating newspapers and magazines ([16], p. 9). Indeed, he produced a continuation of Azul y Blanco in his first year in Barcelona, 1895, a copy of which is preserved in the Paris museum, but above all he did so on a more professional basis in Madrid when he created the magazine Arte Joven, in 1901, with the Catalan writer Francisco de Asís Soler, sharing in the radicalism of the 1898 Generation or an anarchist position and acting, as he had done in A Coruña, as editor, writer, illustrator and administrator all at the same time.3 Although his collaborations with newspapers from 1899 onwards ([17], p. 167), following A Coruña, took place in Barcelona with illustrations for the journals Joventut, Pèl & Ploma and Catalunya Artística, which, for Raymond Bachollet, an expert in Picasso’s relationship with the press [17], are his first true incursions in this field (“Los dos primeros dibujos de Picasso realmente concebidos para la prensa, aparecieron en Joventut (Juventud)…Había sido invitado a ilustrar dos poemas de Juan Oliva Bridgman…” [The first two drawings by Picasso really conceived for the press, appeared in Joventut…he had been invited to illustrate two poems by Juan Oliva Bridgman…]) [18] in detriment to his creations from A Coruña, as he explains in his abundant literature on the subject [19,20,21], on the contrary to the belief of Pierre Daix [22]. The latter, one of the major specialists on his work, defends that Picasso never abided strictly to the nature of commissioned works, whether this be his early beginnings in Azul y Blanco and La Coruña, as well as Arte Joven, and also the drawings he did for Lettres françaises, on the fourth centenary of the death of Shakespeare in 1964, when he was 84 years old, or for Patriote from Nice, in 1967, “Sus periódicos de infancia—dice—son ya su diario personal y así serán sus trabajos para la prensa durante toda su vida, una peculiar extensión o adaptación de la obra en curso” [His childhood newspapers are his own personal diary and that would also apply to his work for the press throughout his whole life, a particular extension or adaptation of his work in progress] [22].

Raymond Bachollet and Pierre Daix together with Jean Pierre Jouffroy, Georges Tabaraud and Georges Gosselin are responsible for one of the most interesting compendiums on Picasso’s work in the press throughout his life (Picasso et la presse. Un peintre dans l´histoire) [23], taking as the starting point, some of the best exhibitions dedicated to this theme, like for instance the show in 2000 at the Picasso Museum in Antibes (Picasso et la presse) [24].

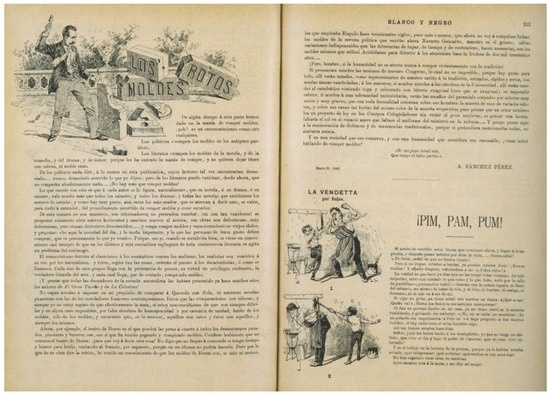

In all cases, we know that Picasso’s interest in the illustrated press arose from his own curiosity about this type of graphic information and is documented, as recalled by Ventureira and Pardo [7] and Baldassari [15] by the presence in the archives of various issues of the magazines Monde Illustré, from 1880, La Ilustración, from 1890, further copies of the Barcelona magazine Un tros de paper, from 1865, and of course the one that most strongly influenced the examples we are concerned with here, from its modernist standpoint, the Madrid magazine Blanco y Negro, which began publication in 1890. It is quite clear, then, that in the A Coruña newspapers the impact of Blanco y Negro (Figure 1)—which his father read ([7], p. 91)—is the most obvious on the basis of its graphic codes and treatment of news, which the child cleverly tried to imitate ([16], p. 10).4

Figure 1.

Blanco y Negro, 48. Madrid, 3 April 1892.

2. Azul y Blanco, the Picassian Origin of Satire and Critical Humour

The first issue of Azul y Blanco [25], with which he began his journalistic output, is dated 8 October 1893,5 a couple of weeks before his twelfth birthday and a few days after the start of the new school year. The title emulates that of Blanco y Negro, and Luis Seoane associates it with the colours of the flag of the port of A Coruña and that of Galicia, whose colours are blue and white ([13], p. 276). In this copy, produced with pen on paper, the manuscript title appears as “Asul y Blanco”, transcribing the Andalusian pronunciation, and there is a sketch of an urban scene, notably including the facade of a balconied house, the back of a travelling stagecoach, and a couple—a soldier and a young lady wearing a hat—with a little dog. On the right, where the date appears, beneath the title, which is repeated, some tubes of paint or bottles with labels centre the composition. Under them is written: Telegramas/Madrid [Telegrams/Madrid], the heading of a text which reads: “A la hora de entrar en máquina este periódico no se recibió ningún telegrama” [At the time of going to press this newspaper has not received any telegrams.] This sketch, which is still very rudimentary, is followed in the same newspaper by others that are more complete, and also more eloquent, such as the one he dates 24 September 1894 (Septiembre 94-24) [26].6

The left-hand sheet is headed by a title: “La canícula de los perros” [The Dog Days of the Dogs], underneath which is a drawing with an unusual trainer and three dogs playing, accompanied by the corresponding text: “En un examen de aritmética El profesor. Si le dan a V.5 melones y se come 4 ¿Cuánto le quedaran? El alumno. Uno/P. Mirelo V. bien q le quedará/A. una indigestión” [In an arithmetic exam. Teacher: ‘If you are given 5 melons and you eat 4, how many will you be left with?’ Pupil: ‘One.’ T: ‘Think carefully. What will you be left with?’ P: ‘Indigestion’].

On the right-hand sheet, under the title, the text runs between the drawings: “Entre aguadores”/Non he vistu pueblu mais embustero que este Madrid/¿Por qué nus harán ir a todus los fuegos? Hombre para apagarlus/¿Entonces para q dice en todas casas “asegurada de incendios” [Between water carriers./‘I’ve never seen a more lying town than this Madrid./Why do they make us go to all the fires?’ ‘To put them out, of course.’/‘Then why does it say “insured against fire” on all the houses’]?

Picasso’s irony and humour as a child transcend the substance of the message and go beyond the content, in that in the second text he imitates the pronunciation of a typical Galician speaking Castilian badly with a strong regional accent. And this fragment from his little newspaper would be enough to make one agree with Brigitte Léal’s view in referring to them, foreshadowing his later work as precursors of jokingly critical sketches, written in a feverish, turbulent, exuberant vein, always rich in poetic and humorous associations ([27], p.10). It is a poetics of hints and ambivalent earthiness, often accentuated, which includes more refined and sociologically exquisite satirical elements, as on the page from the issue of Azul y Blanco dated Sunday 28 October 1894 [28], preserved in the Museu Picasso in Barcelona,7 signed by him in several places on the sheet, in which he reveals an early consciousness of style in the brushstrokes of the figures: agile and sketchy, with gestural and expressionist lines to build the iconography of those newspapers, a model of drawing that he would repeat in his Cuadernos from A Coruña from 18948 and 18959, with isolated compositions combined with the text and devoid of any thematic connection with each other.

In the upper left part there is a section in capitals entitled Telegramas [Telegrams], with a little text underneath: “A la hora de entrar en máquina este periódico no se ha recibido ningún parte telegráfico…” [At the time of going to press this newspaper has not received any telegraphic communications…] Below this, illustrating what he calls Nota de actualidad [Latest News in Brief], between two caricatured drawings of women in profile arguing and a male face in the centre, there is a gentleman wearing a tie, and a text: “Pues Señores no tenemos nada de particular q decir a V.” [Well, ladies and gentlemen, we have nothing in particular to say to you], while the right-hand page, headed by the title and date, underlines the number 20 and continues with another text: “Se publica todos los domingos”. [Published every Sunday.] Underneath this is the following: “Sr. Dn. José Muñoz Estevez/Muy Señor mio y de todo mi respeto y consideración contando a V. en el numero de nuestros suscritores tengo el honor de participarle y desde el dia de hoy comienza otra vez a continuar sus funciones el periódico Azul y Blanco/P. Ruiz” [To Mr José Muñoz Estevez/Dear Sir, With every respect and consideration to you as one of our subscribers I have the honour to inform you that from today the newspaper Azul y Blanco is beginning once again to resume its functions./P. Ruiz.] On the right there is a drawing of a boy with a typical rural Galician beret and the title Un vendedor de periódicos [A Newspaper Seller], while the cartoon below depicts the face of a distinctly Galician countrywoman.

It is notable that on most of the pages in these little newspapers the young Ruiz Picasso, who had beautiful handwriting, makes spelling mistakes and generally does not use accents correctly, and at the same time is very free in his use of punctuation and abbreviations, omitting commas on numerous occasions.

The other page from the 28 October 1894 issue of Azul y Blanco (Picasso Museum, Paris)10 concentrates on graphic features and is closer to the structure of Blanco y Negro, mentioned above, and to its modernist typology, whether in the way the text is associated with the images, as in the Letters Section of the Madrid magazine—some issues of this magazine, over the course of 1892 or 1893, seem to have inspired Pablo—or in the iconographic treatment, very much to the taste of illustrators of the period [29]. The information is presented in the form of short texts with little framed scenes that enable us to visualise the news story with a sparkling touch of irony: “Ya ha empezado a llover así continuará hasta el verano” [It has started raining and will continue until the summer] is the succinct phrase written under the image of a gentleman carrying an umbrella, like the comment on a sketch of a lady with her skirt blowing up: “También ha empezado el viento a caminar a…hasta que no halla Coruña” [The wind has also set off on its way to… until there’s no more Coruña]. And beside it there is an “ANUNCIO: Se compran palomas de casta/dirigirse a la calle de Payo Gomez número 14 piso 2º Coruña” [ADVERTISEMENT: pedigree pigeons bought/apply to 2nd floor number 14 Calle de Payo Gomez Coruña].

At the bottom he draws two women talking to each other and entitles it Dos barbianas [Two free-and-easy ladies], and on the right there are various scenes with drawings of male faces (REVUELTO [MIXED UP], it says in capitals) and others that refer to Una madre de familia [A Mother] (with female figures), Un padre de familia [A Father] (a gentleman with a hat and stick), the Desafío del “Guerra”, [“Guerra” Challenge], probably alluding to the famous bullfighter Guerrita ([7], p. 392, p. 439), talking to another matador, both of them wearing bullfighting costumes, and a conversation between two soldiers, in which one is asking the other how cannons are made.

All the drawings are given a tone of caricature and are a synthesis of the facility for expressing feeling with which the young Picasso observed the city, in a patient analysis which explored the weather conditions that had such a decisive effect on the lives of the inhabitants of Galicia, whose austere temperament he managed to capture, as well as their sociological subtleties, perceived in tiny details, from family life to village gossip and the ever-present power of the military class and the clergy (there is a priest at the top of the page) and the habitual love of bullfighting.

An issue of Azul y Blanco from Christmas 1895 has survived, mistakenly ascribed to A Coruña; presumably he produced it when he was already living in Barcelona,11 as a continuation of those he had done in Galicia, since by that time the family had settled in the Catalan capital. The same ironic tone is still present and the drawings cover both pages (“Azul y Blanco/Número de Navidad” [Christmas Issue] it says on what is presumably the front page), occupied by a scene with soldiers and a figure with a horse on the left and a turkey on the right with an inscription: El héroe de Navidad [The Hero of Christmas] and above it his signature, “P. Ruiz/95”. On the second page, there is another turkey and a religious scene, in which Christ is addressing a seated character.

3. La Coruña, Self-Representation through the World

The second newspaper Pablo “published” in A Coruña was La Coruña. The first issue is dated 16 September 1894 and is preserved in the Picasso Museum in Paris [30].12 It is perhaps the more explicit in terms of the range of information, and together with the sketchiness of its drawings—in ink with hardly any corrections and very brief texts—it again displays the satirical character of the earlier issues of Azul y Blanco. It concludes with the longest known manuscript text written by Picasso as a child and a page totally covered with caricatured drawings, presumably designed to illustrate the sociological information on the city’s fiestas.

The first page, which functions as a front cover, with the number 1 inscribed on it, is headed by the title, dated (Se publica todos los domingos [Published every Sunday], it says) and dedicated to Sor Dn Salvador Ruiz Blasco, his uncle. Underneath there is a box with the indication Director/P. Ruiz [Editor/P. Ruiz] and the image of a Tipo gallego [Galician Type]—this title is written under the drawing—in profile. Next comes a lengthy text to which I shall refer later on. The left-hand page is one of the most expressive: a circle with a triangle inside it surrounding the business address: DIRECCIÓN PAYO GÓMEZ [ADDRESS PAYO GÓMEZ]. And the page contains a number of juxtaposed phrases clarifying the simple drawings: “pin-pan-pun”; the Tower of Hercules: Boceto para una torre de caramelo [Sketch for a Tower of Caramel]; two peasants: Bañistas acuden a vañarse13 (Los de Betanzos). [Bathers going for a bathe (the ones from Betanzos)]; a male figure and two peasant women: Como se bañan los de Betanzos [How people from Betanzos bathe]; what look like some firecrackers and a palette: Cartel de la fiesta [Festival Poster]; and beside a caricature of a rich, well-groomed young man smoking a cigarette: Y alguna q otra corrida cosa poco común aquí [And the occasional bullfight, which is unusual here].

Once again, the shadow of Blanco y Negro, the copiously illustrated modernist Madrid magazine that we know the boy must have seen or read, because his father read it, hovers over the typographic design and general structure: from “Pim, Pam, Pum”, which Blanco y Negro used for humorous purposes and in which Picasso changes the spelling, but not the intentions, just as he had done previously when drawing on quotations from telegrams or manuscript summer letters, everything is invested with that feeling of a synthesis between the humorous drawings and the fragmentary texts.

According to Anne Baldassari [16], the young Picasso had discovered a way of making us understand reality using both visual means and writing, through an expert and at the same time detached knowledge of the semantic codes of the print media of his time. As in illustrated magazines, then in their heyday, the juxtaposition of text and image, titles, headings, articles, cartoons and captions was organised so as to create that specific object, the newspaper, composed of signs offering multiple readings. And through the familiar use of these pastiches, Picasso expressed the humour of his vision of the world and showed evidence of an iconoclastic use of the mass-circulation press, as an object of derision, and especially the urgent, sensationalist style of journalism ([16], p. 30), of which he had such an acute grasp, far removed from the prejudices of maturity and from the perspective of childish innocence.

The boy Picasso’s tone remained ironic and critical, and we should ask ourselves whether this attitude arose by chance, which is very unlikely, or whether it was really because the atmosphere in which his life was unfolding and his upbringing were not characterised by the acquiescence that enables one to accept anything without first questioning it. The origin of this critical questioning and the high degree of sarcasm with which he filtered the news and perceived the life he conveys to us, through images and texts, was fuelled in the freethinking A Coruña atmosphere of Dr Ramón Pérez Costales, his protector and mentor, or even in that of Pérez Costales’s illegitimate son, Modesto Castilla, with whom Picasso seems to have been on good terms, as is evident from the fact that he dedicated some drawings and paintings to him, and whom he depicted in one of his best portraits from this period. But it was also fostered in the street and among the friends he spent time with, shaping a genuinely Galician character, permanently in doubt, constantly enquiring, though not immune from sarcastic humour and ambivalence, reinforced by discipline and obstinacy, during a period of years in which the moulding of his nature began to be definitively consolidated. All this was in addition to the decisive influence of José, his father, an equally subtle freethinker, as Anne Baldassari argues ([16], p. 31), portraying him as someone who moved in bohemian artistic milieu and in liberal and progressive circles in his youth and was noted for his caustic wit, brilliant remarks and a certain number of picaresque adventures.14 And we might take the view that to this atmosphere of political tension, artistic debate and rebellious humour that she sees as the crux of the formative philosophy of early Picasso—which was always to remain with him—we should add his unquestionable critical genius and the sharp, lively disposition to which his fellow student Ramón María Tenreiro already referred, recalling his image and actions, sometimes out of place, at secondary school, the School of Fine Art and the streets and beaches of A Coruña ([31], p. 175).

La Coruña concludes with the longest text that the young Picasso had written in his little newspapers published in the city, in which he gives an account, in the manner of a news article, of the programme for the fiestas in A Coruña, which, as we know, are in August [32]. Pablo, who was not yet thirteen and would not enrol for the following year of his baccalaureate, 1894–1895, which gives us some idea of how little value he attached to these studies that were supposed to regularise his school education, presents us here and there with spelling and phrasing that do not observe the rules.

The title is expressive: Fiestas en la Coruña. And it reads as follows: “Agosto-Día 4. A las doce en punto de la mañana un repique general de campanas doce bombas de palenque y las gaitas del país tocando alegres vises populares anunciarán el comienzo de las fiestas. Bién q. Al amanecer de este día las bandas de guarnición recorrerán las calles principales tocando animadas Dianas militares al mismo tiempo que las gaitas dejan oir alegres Alvoradas.15 A las once se celebrará en la Iglesia de San Gorge explendidamente decorada la solemne Funcion religiosa con asistencia del Exmo. ayuntamiento y principales autoridades con cumplimiento del voto hecho por el pueblo de la Coruña en 19 de Mayo de 1589 al ser librada del asedio q. le tenía puesto la armada inglesa por el hecho heroico de de Maria Mayor Fernandez de la Cámara y Pita16 estando encargado del panegírico el ilustrado y elocuente orador sagrado Sr. Don Antolín Lopez Gomez Magistral de la catedral de Lugo y oficiando de pontifical con asistencia del cabildo, el Exmo. E Ilmo. Sr. Arzobispo de Santiago. A las 5 (?) de la tarde variadas y vistosas cucañas17 terrestres en la alameda del paseo de Mendez Nuñez frente al local de la sociedad del Sporting-Club.- A las 9 de la noche y en los intermedios de la velada musical en dicho paseo se elevaron Globos grotescos y de variadas formas. Al mismo tiempo q. iluminará infinidad de fuegos de aire de sorprendente y variada luceria (Se continuará)”. [August 4th. At twelve noon precisely a general peal of bells, twelve firecrackers and the local bagpipes playing merry popular tunes will announce the start of the fiestas, although the same day at dawn the garrison bands will march along the main streets playing stirring military reveilles while at the same time the bagpipes will sound lively alvoradas [sic]. At eleven o’clock the solemn religious service will be held in the splendidly decorated Church of St George in the presence of the City Council and the leading authorities, in fulfilment of the vow made by the people of La Coruña on 19 May 1589 on being liberated from the siege to which they had been subjected by the English navy though the heroic actions of María Mayor Fernández de la Cámara y Pita. The eloquent and illustrious holy orator Don Antolín López Gómez, chancellor of the cathedral of Lugo, will be entrusted with delivering the panegyric and His Excellency the Archbishop of Santiago will officiate pontifically in the presence of the chapter. At 5 [?] o’clock in the afternoon there will be a variety of spectacular cucañas set up in Méndez Núñez avenue opposite the premises of the Sporting Club society. At 9 o’clock in the evening and in the intervals of the musical soirée in this avenue grotesque balloons of diverse shapes will rise into the air, while at the same time countless rockets will light up the skies with amazing and varied colours. (To be continued).]

The meticulous handwritten description of the festivities that took place on 4 August and that he recounted on 16 September 1894, that is, over a month after the events, was addressed to his family in Malaga to inform them how things were going for the Ruiz Picassos in the city, overcoming the gloomy portents of a long, hard winter, but he also makes it clear, at least, that they did not return to Malaga for the summer and remained in A Coruña, making it possible to provide a more pleasant, festive image of the latter, and this necessarily entailed breaking away from the much-cited unpleasant face of the weather and experiencing quite different conditions, which tend to be moderately warm and fresh in the summer months, reinforced by the joyful bustle of the new season.

So journalistic activity, planned as a special kind of adolescent experience or game, turned out in the end to play a more important part in Picasso’s life than providing a mere documentary record of the child who wanted to tell his family in the south about his life in A Coruña: it was, albeit unconsciously, the starting point of an experience that was to grow in scale in subsequent years, from actual participation in the press, which he never abandoned and which was very prolific in certain periods, such as the 1950s with his contributions to communist newspapers ([16], p. 213)18, to the epic experimentation with journalistic collage in Synthetic Cubism, with newspaper as a medium or papier découpé, for inventing iconographies, among other procedures that constantly recurred until the end of his life.

Adopting a more speculative approach, Michel Melot considers, regardless of the fact that no such association is attested historically, that the young Pablo’s handwritten newspapers could be related to the first truly popular comics (bandes dessinées), which, in many cases, delighted some people and outraged others ([33], p. 83). However, there was nothing definite in the practical significance of those newspapers beyond that perception of “first visions” recorded in the malleable thickness of the printing matrix—that of his conscious or unconscious mind, depending on how one wishes to see it—which “podrían encarnar la permanencia de un universo de imágenes, donde Picasso se autorrepresenta en y a través del periódico del mundo, el periódico de su vida, el periódico de su obra” [could embody the permanence of a world of images, where Picasso represented himself in and through the newspaper of the world, the newspaper of his life, the newspaper of his work], as Anne Baldassari put it ([16], p. 218).

However, Picasso’s newspapers from A Coruña have more to do with these first visions and chronicles perceived by a child who interprets his concerns in picaresque terms and always with a biting sense of humour, which were to leave nobody indifferent thanks to the impact of the solitary, isolated and always expressionist image, than with the first bandes dessinées mentioned by Melot ([33] p. 83), in the tradition of Le Petit Français illustré, journal des écoliers et des écoliers.19 Those stories usually had a theme and the drawings were divided into sequences related to the script of the short text featured below them. As opposed to their realism, highly constructed and nuanced, the isolated drawings by Picasso reinforced a gestural and exclamatory dynamic that underscored the more ironic and critical aspects of the image in the setting of what we understand as the vignette, closer to the impact of the satirical and expressive drawing, always sketchy and laced with humour, which is what he was looking for, over and above telling any story. We believe that the historieta was understood at the time as a “cuento o fábula mezclada de alguna aventura o cosa de poca importancia” [a tale or fable mixed with the odd adventure or things of little importance], which, in the specificity of the Spanish illustrated press of the second half of the nineteenth century, translated as an insignificant story or fabulistic and even theatrical invention ([34], p. 32). This had nothing to do with the goals of Picasso’s vignettes or drawings as a child in his newspapers from A Coruña in which, whenever he wished to add emphasis to the story, he made use of text to make it more explicit.

The Spanish term most closely corresponding to the French concept of bande dessinée20 is the then nascent and incidental historieta, which was subsequently expanded with greater precision in specialised journals in Spain in the final quarter of the nineteenth century in the form of caricatures or aleluya (auca), which earned a respectable status in the classic, ingenious humour of the draftsman Ramón Cilla, in Madrid society, especially in Mundo Cómico (1880) and La Caricatura (1884), counterparts of the French publications Le Monde Comique and La Caricature. Cilla, together with Apeles Mestres, Ramón Escaler and Mecáchis were the major players in this graphic field and its most critical satirical conscience during the closing decades of the century, making use of kinetic signs, the first crude speech bubbles, graphic metaphors and the expressive mobility of the figures, in now mythical publications like Los Madriles, La caricatura and particularly La Semana Cómica ([34], p. 34).

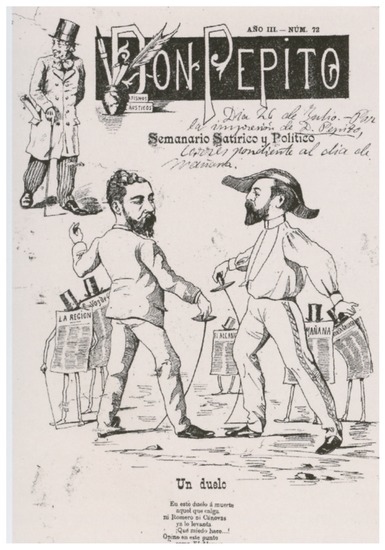

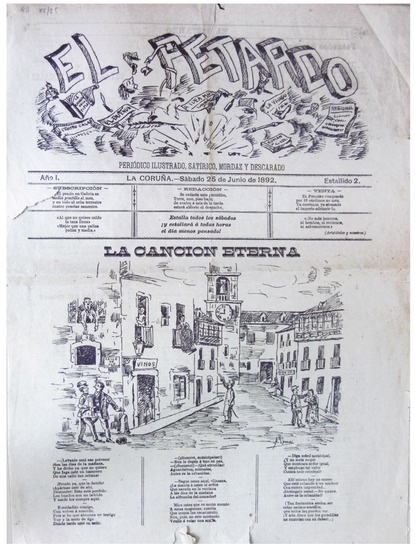

But these illustrations, and also their more well-known authors, which began to make their way into modernist show business, fashion and current affairs journals like La Gran Vía, Nuevo Mundo, La Ilustración Española y Americana, La Ilustración de Madrid, El Museo Universal and La Esfera ([34], pp. 32–34), were unfamiliar to the young Picasso, who only knew Blanco y Negro, his true source of reference, which he had access to thanks to his father. We do know however that the daily newspapers of A Coruña (the most popular being La Voz de Galicia, El Diario de Galicia and El telegrama) barely used any illustrations at all, but there were some highly popular satirical publications in the city such as El Duende, Don Pepito (Figure 2) and El Petardo (Figure 3), which were founded between 1886 and 1892 and made profuse use of caricatures, and this would have been something José Ruiz Blasco and his son Pablo were well acquainted with ([17], p. 173).

Figure 2.

Don Pepito, 27 July 1890. Printed magazine. Biblioteca de Galicia, Santiago de Compostela.

Figure 3.

El Petardo, 25 July 1892. Printed magazine. 40.5 × 30 cm, Real Academia Gallega, A Coruña.

More than the consolidation of a specific style, the previously mentioned characteristics tells us, through an analysis of his “little newspapers”, that the adolescent Ruiz Picasso engaged with the way of thinking of the city and into many of its customs and commonplaces, how he interprets it with humour, but above all how he reproduces a distinctive sociology of fin-de-siècle Galicia, between the weight of the rural and provincial and an urban desire to emerge, looking at the world from the fragmented metonymy of that Coruña which defended the Athenian slogan that no one was a foreigner in the city. Here we can find the seed and the graphic expression of the critical and social rather than political consciousness of the teenager, in line with what Jean-Pierre Jouffroy argues (“Debemos señalar, en primer lugar, que los dibujos de juventud publicados tanto en la prensa española como francesa se refieren más a la crítica social y no a las relaciones directas con la política” [we should point out, first of all, that the juvenile drawings published in the Spanish and French press refer more to social critique and are not directly related with politics]), which, with the odd exception, due to the nature of events and demands, persisted throughout his whole life [35].

4. Activism and Rebellion, Caricature, Sarcasm and Voyeurism

As Ángel Padín reminds us ([5], p. 43), this precocious adolescent, in whom a rebellious child coexisted with an artistically mature young man, first became aware of politics and of commitment to the most deprived members of society through contact with what was then his adopted city, guided by his artistic patron, the politician and doctor Ramón Pérez Costales, but also of the profuse social and cultural activity being pursued there, especially in cultural circles, such as Circo coruñés, which his father, José Ruiz Blasco, frequently attended. And there is something else of fundamental significance in the life of the adolescent, who knew he was going to be an artist, that also emerges in the newspapers: a critical and ideological position, connected with the political awareness just mentioned, a position that was to mark his future and his life commitment for good, and this sprang, we must remember, not only from his family circle, defined by the caustic temperament of his father, José, but also, and above all, from the republicanism and freethinking of the above-mentioned Dr Ramón Pérez Costales, his great champion in A Coruña, but also his mentor and his greatest friend, who was the mirror of his moral formation in those years ([10], p. 217; [4], p. 38; [7], p. 268, p. 283).21 Therein lies the initiation or genesis of a more humane, political and activist Picasso, the one who painted Guernica in 1937, the one who committed himself as an active member of the French Communist Party in the autumn of 1944, and the one who drew the dove that symbolised the First World Congress of Advocates of Peace, held in Paris in 1949, so well revealed in the exhibition at Tate Liverpool, Picasso: Peace and Freedom.22

But beyond the documentary and critical consciousness we find in the childhood newspapers, the more remote beginnings of that adolescent who at that time signed himself as Pablo Ruiz can be traced in his first doodles in his school books, many of which fall into the category of meta-irony, an attitude that was reinforced by his experience of ambivalent Galician existential doubt and drew on humour and double-sided codes to define unprecedented situations. It was this that gave rise to his vocation as a caricaturist. In those now faraway books, on which he drew in class and, more particularly, in the calaboose, he incubated this vocation and this early reflexive and caustic outlook that would end up defining one of the most critical slants of his practice, especially through caricature, with its power to denounce, which he would inevitably take to such striking works as Sueño y mentira de Franco and Guernica, both made during the course of the Spanish Civil War (1937). Picasso himself spoke of the importance in his formation as a draftsman the many hours he spent in the school’s calaboose, as a result of the many punishments he received for his rebellious character and his opposition to regimented study, which would not only try his father’s patience—who absolved him from secondary school in the 1894–1895 school year, at the young age of thirteen—but also to make him understand that his true dedication was art. This rebelliousness and punishment which the adolescent was able to turn to his own advantage, is addressed in some of his biographies and an early one from 1923 by his fellow schoolmate, Ramón María Tenreiro, already alluded to the “perenne huésped de los calabozos en los que la autoridad disciplinaria del director encerraba a los escolares rebeldes” [perennial guest in the calaboose in which the director locked up rebellious students] ([31], p. 175), a peculiar accommodation recalled by Luís Seoane, the artist from Galicia, when he visited him at Sala Pleyel in Paris, in 1949, and to whom Pablo replied that in that place “aprendió más que en ningún otro sitio a dibujar, tal era la frecuencia con que le encerraban” [he learned more than in any other place to draw, so often was he locked up there] ([13], p. 276). Though, obviously, a consequence of being a bad student, in that bare cell unfurnished except for a bench to sit on, the young Ruiz Picasso liked to while away the hours drawing non-stop in his sketch pad or on the pages of his school books ([4], p. 42). These were the books that the child artist carried around with him, illustrated during hours of frenetic activity, trying to make the most of his punishment. They were to remain with him until 1970, three years before his death, when he decided to donate them, together with many other works, to Museu Picasso in Barcelona. A good example of those doodled texts is La literatura preceptiva. Retórica y poética [36], by Emilio Álvarez23, whose cover was illustrated by Pablo with two figures of a man, one of them a priest with biretta, and a horse. He filled the pages with sketchy caricatured silhouettes of children, dolls, characters with guns—after all, he was still a child—sometimes depicting a duel, architecturally building his name, hands and flies, hammers, tools, rifles, scrawls, profiles of a woman, muskets and carbines, bears, more caricatures, bottles and geometrical figures, hands wielding machetes, caricatures of mandarins and Andalucian señoritos, repeated signatures of Pablo Ruiz on the same page, caricatures of Práxedes Mateo Sagasta24 and General Martínez Campos—on pages 64 and 65—and, once again, birds and branches, tree trunks and limbs, repeated heads, lit candles, mules with saddlebags, animals and banners, caravels and cannons, more geometric figures, triangles, cones, sailing boats, daggers, the Eiffel Tower, penguins, dancers, sables and carbines, children’s heads, machetes, women, bearded men …And one donkey mounting another, on page 178 (Borriquillo y borriquilla25) [37], with some very expressive verses (Sin más, ni más, ni más/la burra levanta el rabo./Sin más, ni más, ni más/el burro le mete el nabo [Without further ado/one donkey lifted her tail./Without further ado/the other donkey gave her his turnip]), a drawing speaking of the young man’s irony and humour, which had already awakened to sex, sex he saw on the streets, filtered through humour and caricature, in the exaggerated ambivalent way he had of interpreting it. These doodles, sketches and drawings in his text books were at the very origin of his sense of caricature and his personal newspapers analysed above.

The innocence and mischievousness he displayed in the newspapers enabled him to travel through the secret world of an aestheticised laughter which imagined fantastic little animals and characters also dying from laughter, bulls, doves, dogs or cats and donkeys or Cliper himself, his dog. If we bear in mind that caricature is a form of artistic expression whose language is based on formal exaggeration or actual distortion of the features of a character, to reinforce, in a humorous tone, the critical levels—political, social, religious, cultural—that one wishes to highlight, sometimes emphasising other facets, such as the grotesque, the ridiculous or the satirical, and whose ideal format would be cartoons, we will appreciate the amazing precocity of Picasso, who, from the age of eleven, began to attain unimaginable levels of critical acumen for a child of his age. And as we observe when we confront the little newspapers produced in A Coruña in 1893 and 1894, his references did not stray far from what he could see in the press of the period, especially in the magazine Blanco y Negro, which made very frequent use of caricature and with which Pablo must have been very familiar, from the composition of sections such as the Cartas de veraneo [Summer Letters]—interweaving the caricatured scene with the handwritten text, an option also employed in some issues from 1892—to others in an essentially comic vein, such as “PIM, PAM, PUM!”, also from 1892, already cited above. Its echoes were present in Azul y Blanco and La Coruña, which are reinterpretations of the situation that had attained a high degree of development in nineteenth-century British journalism and especially in France in the time of Napoleon III and Louis-Philippe, with particular attention to the political genre, which achieved mass circulation with the expansion of lithography. It was a procedure that reached Spain and was notably successful in the periodicals cited earlier, thanks to the contributions of specialists or artists—Goya had already made use of caricature in certain works, and this aspect of his poetics led to his expressionism in the Quinta del Sordo, which has a great deal of caricature in it—and it became firmly established in the second half of the nineteenth century, with the names of pioneering figures such as Tomás Pardo (1840–1877) and Francisco Ortego (1833–1881), famous for his contributions in El Fisgón, and especially in Gil Blas, where he consolidated his reputation as a caricaturist and satirical draftsman. Precursors to the names cited earlier. Having said that, caricature was rarely so strong and widespread as in the reign of Isabella II and the regency of María Cristina, the context of Picasso’s childhood, when the situation in Spain was reinterpreted from a critical standpoint, with significant figures such as the previously cited Ramón Cilla and ad hoc newspapers like Madrid cómico. They undoubtedly responded to the flood of French influences in Spain, which were even greater after the law on freedom of the press was passed in 1881 in France, paving the way for the proliferation of highly diverse and abundantly illustrated newspapers [38].

The fact is that the young Picasso, through the levels of critical acuity he had already shown in his drawings in A Coruña, based on a highly ironic reinterpretation of caricature, clearly displayed an ideology that was sarcastic and progressive, to say the least, and that was to characterise him throughout his life. Specialists, such as Michel Melot, already cited above, who analyses this facet in particular, identify these aims in the origin of his artistic revolution from 1907 onwards: “La abundancia y sobre todo la variedad de caricaturas—considerando esta palabra en el sentido más amplio—que se encuentran en los carnets y las hojas de croquis de los primeros años del pintor, entre 1894 y 1905, son ya el signo de que un revuelo se avecinaba…” [The abundance and above all the variety of caricatures—taking this word in the broadest sense—to be found in the notebooks and sheets of sketches from the painter’s earliest years, between 1894 and 1905, are already a sign that an upheaval was on the way…] ([33], p. 82)26. Although there is no attested historical relationship, he even goes so far as to relate these caricatures to the bande dessinée, the comic, of popular origin, and on that basis, stressing the chronology in A Coruña in 1895, he considers that Picasso creates a veritable inventory of ways of drawing, “por lo cual parece querer agotar todos los modelos posibles” [and therefore seems to want to exhaust all the possible models]. They are drawings defined by the elliptical style of press illustrators, with the schematic line that had been imposed by the new printing techniques used by newspapers, which young Pablo’s constantly alert eye had perceived as a different mode of interpretation. While the caricaturised world of the adolescent Picasso responded to the widely accepted definition of the caricature inasmuch as it embraces social satire and humorous drawing based on comic effect and expressive deformation, it also coincides with Werner Hoffmann’s view of it as a total negation of ideal beauty ([39], pp. 426–427). In fact, a large part of the young artist’s caricatures from his time in A Coruña, far from focusing on the forms, left them unfinished and reinforced the sketchiness and gesturalisation of the lines in benefit of the expressive impact of the first glance. In this regard, his references are more of a conceptual than a stylistic order, which is why it is difficult to establish a comparison with other models. In addition, his caricatures at that time had not been made to be published or in response to the current events in a newspaper or journal.

And similarly, in this adolescent period of 1894 and 1895, linked to the world of caricature, there emerged, almost innocently, the theme of the voyeur, which was to be so important throughout his artistic life and was to reappear obsessively in the work of his old age ([33], pp. 86–87). Thus, we find, associated with a caricature, that of a blatant and naive female nude, betraying the subtle, primitive and equally precocious perversity of the apprentice artist manifested in his albums, his textbooks, his little newspapers and the hundreds of loose sheets that have come down to us and enable us to form a reading of Picasso which will only be complete and coherent if his origins in A Coruña are understood in this light.

Now and then the humour comes close to explicitly adopting the philosophy of the cartoon, as we can see in examples such as Los Paraguas [The Umbrellas], a work dated to early 1892, when Picasso was not yet eleven.27 He sardonically portrays a classic A Coruña street scene that could be taking place at any time of year but is probably in winter, on a rainy day—the recurrent weather conditions which obsessed Pablo and especially his family—in which the characters are walking along carrying umbrellas in front of some pigeons. Above the succinct multiple images, schematically rendered in their essential features, the artist has written a dialogue by hand: “D. Juan me alegro de encontrarme a V. porque me he salido de mi casa sin sombrilla y está lloviendo/Pues véngase V. conmigo y le acompañaré hasta su casa” [‘Don Juan, I am glad to see you because I have come out without a parasol and it is raining’/‘Well, come with me and I will walk you home’]: satirical, caricatured scenes that we have already seen in the newspapers, but that acquire a special autonomy when he isolates them in order to underline the most absurd or shocking effects, stressing the exaggeration of the facial features which reinforce the humour or the grotesque postures, as in Caricaturas28 (1894) [40].

The same effect is reproduced in the Caricatura de torero [Caricature of a Bullfighter],29 where he accentuates the distortion of a macrocephalic, almost monstrous face, not something he commonly tends to do in his drawings, which are always restrained, despite his young age. Exaggerating the peculiarity of a face in this way leads him, on other occasions, to intensify the grotesque, as in Torero y monje [Bullfighter and Monk]30 [41], where the characters are very schematically drawn but highly symbolic as representations of two social forces at that time: bullfighters and the Church. In its schematic approach, it reduces the bullfighter’s eyes to numbers. However, as in the albums, its sense of caricature is focused more on the complexity of a drawing elaborated in its visual aspects to express social situations or narrate events. What is curious is that at the top on the left-hand side the paper on which this caricature is executed bears the stamp his father, José Ruiz Blasco, used in his classes, and Pablo was his pupil in the 1892–93 academic year for Dibujo de adorno [Ornamental Drawing], being registered with enrolment number 88. It so happens that the bullfighter’s eyes are two 8s, which may be a cryptic allusion to his enrolment number, just as we can make out two 7s in the monk’s eyes, which would therefore make up the number 77, but we do not know what this could refer to.

His caricatures of families going for a walk make it clear: they may seem humorous in their offhand, clichéd bourgeois representation, but the characters in them are highly elaborated. One case (Familia caricaturizada [Caricature of a Family], 1895)31 recalls the classic scenes by caricaturists in the magazines of the period, such as the previously mentioned Blanco y Negro, with a wealth of highly sculptural realism achieved through the contrasts of light and shade in his exquisite pen work, and in the other (Caricatura de una familia paseando y varios croquis [Caricature of a Family Going for a Walk and Various Sketches], 1895)32 the central composition is copied from the previous one, though he uses the rest of the paper the other way up to draw two deer, two men’s heads and five pigeons and includes two more children in the scene [42]. Both of them reflect the critical subtlety of Pablo’s thought, in that what is caricatured is the social convention itself, treated as a stereotype, an aim repeated in many of his representations of local life, and to a more marked degree in certain parodic dramatisations. This is true of El diálogo y otros croquis [The Dialogue and Other Sketches], in which the scene centres on two gentlemen in suits with hats and sticks, in profile, and of Parodia de un caballero [Parody of a Gentleman]—dated 1894 and 1895 respectively33—where he carries forms or rituals to the point of explicit social absurdity. However, the young Picasso also makes use of the procedure of caricature to emphasise the playful or light-hearted sense of life, as is the case in various drawings preserved in the Museu Picasso de Barcelona: in Caricaturas diversas [Various Caricatures],34 from 1894, he recreates a succession of lively sword fights, superimposed on each other, and in Caricaturas,35 from the same year, the comic representation is staged by adult or child characters, grouped or isolated, almost in miniature, accompanied by a text.

Pablo also applies caricature to other more restrained scenes, and in doing so he comes closer to types of image more in fashion in the newspapers of the period, avoiding exaggerated formal distortion and placing the emphasis exclusively on the precision of the drawing and the conceptual interpretation or on the content itself, which is not without humour and a certain sense of the ridiculous, as we see in El décimo de lotería [The Lottery Ticket]36 [43], where he exchanges the more expressionist and gestural deformation, almost always on the verge of grotesque, which he did for the newspapers and caricatures mentioned above, for a more classic and plastic realism, in consonance with the costumbrista legacy of much of the illustrated press, following the tradition in Spain that reinforced satirical artists, since the mid-nineteenth century, like Landaluze ([34], p. 22) and which he could very well have seen in the satirical journals from A Coruña already mentioned, such as Don Pepito or El Petardo, the only verifiable references that he could have had access to at that time, besides Blanco y Negro.

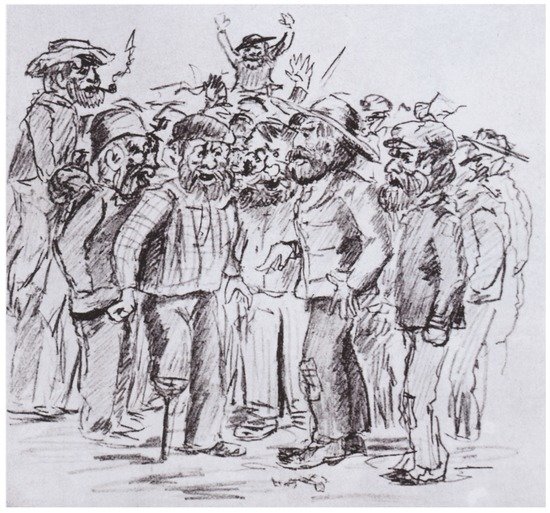

What is more surprising is the late appearance of his more political or ideological caricatures, dated around 1892 and 1893, like Congreso de anarquistas37 (Figure 4), only reproduced many years later in art journals, taking advantage of Picasso’s prestige. The group portrait of the anarchists rebelling has all the ingredients of the satirical drawing, here reinforced by the expressionist lines and a psychological study of the faces of the characters in the foreground, which reveal the precocious maturity of the young artist, able to portray the inner strength of those trade unionists in political and aesthetic terms.

Figure 4.

Pablo Picasso, Congreso de anarquistas, ca. 1893. Reproduced with permission from the Real Academia Gallega, El primer Picasso. A Coruña 2015; A Coruña: Museo de Bellas Artes, 2015, p. 205.

In any case, caricature as an exercise shows us the ability of the then young artist to perceive his ironic vision of the world through drawing, a precociously ideologized vision in terms of critical interpretation. However, the pre-adolescent Picasso was already aware of his magisterial command of this skill in the area of formal experience, which would enable him, years later, to master aesthetic revolutions that depended on having a good professional training in order to be able to express oneself freely. At that time, Pablo Picasso had not yet been born, but only his necessary precursor, who signed himself as Pablo Ruiz or simply P. Ruiz, and that crucially important figure began to define himself when his father decided to endorse his son’s decision to devote himself exclusively to Fine Art and give up the idea of continuing to study for his baccalaureate, in the academic year 1894–1895. That was when the future genius was born, and this is the consensus among experts on Picasso, particularly Josep Palau i Fabre ([3], p. 68, p. 70) and John Richardson ([4], p. 52).

5. A Coruña, the Birth of an Artistic Definition

Not without good reason, John Berger, sensing that this adolescent artist already recognised his own genius as clearly as those around him, acutely comments on the fact that Picasso was a child prodigy, considering that it influenced his attitude to art throughout his entire life. It was therefore one of the reasons, Berger argues, why he was so fascinated by his own creativity and accorded it more value than what he created ([44], p. 52). It is why he saw art as though it were part of nature; by the same logic he saw the distinction between object and image as the natural starting point for all visual art which has emerged from magic and childhood ([44], p. 53).38 However, beyond alleged fascination with himself and magic, which Berger attributes to him, the Pablo Ruiz who lived at such a tender age in fin-de-siècle A Coruña had his feet on the ground and sought to discover the world without interference, at first hand, and so it was that he dared to interpret it with the unprejudiced consciousness of pre-adolescence, with so many critical subtleties. By doing so he managed to create a socio-political and cultural portrait of his world in the metonymy that reflected the city in which he was born as an artist in those decisive years from 1891 to 1895, before he moved to Barcelona and Paris. In the little newspapers, in the satirical and caricatured drawings of those years of youthful rebelliousness in A Coruña, lies the seed of his social and political ideology, as well as his inescapable commitment to the world in which he happened to be living, the first roots of the two extraordinary etchings and eighteen vignettes for Sueño y mentira de Franco and Guernica and all that this work represented in his interpretation of art as a life of activism.

In the exhibition Viñetas en el frente, co-produced jointly in 2011 by Museu Picasso de Barcelona and Museo Picasso Málaga, curated by Salvador Haro, Inocente Soto and Clauste Rafart i Planas [45],39 we had a chance to see how Picasso returned, once again, to the popular vignette and to a highly dynamic and cryptic gestural iconography to denounce the horrors of the Civil War and its main instigator, General Franco. In fact, Sueño y mentira de Franco [46], made by the artist between January and June 1937, at the same time as he was working on Guernica, is the mature expression of those first vignettes he had made in A Coruña against the military insurrection, or its most critical chronicle. Picasso made use of a personal hermeneutics, whose caricaturised images, not exempt from black humour or the more caustic irony of satire and the gags proper to the comic, within the geometric and classical style, expressionist in the deformations, charge against the violence of war in a fragmented narrative that evokes the old aucas from the late nineteenth century. Each one of the vignettes or cartoon strips denounced the massacre of innocents, the barbarism of war and injustice, the destruction of art, violence in all its forms through various allegorical images of a grotesque Franco (with a sword and a flag; a gigantic phallus with a sword and a flag; attacking a classic bust with a pickaxe; dressed as a courtesan, with a flower and a fan; being gored by a bull; praying to a five-peseta coin; wearing a papal tiara and a Moroccan hat; fighting a bull; a woman crying looking to heaven). Some of these figures reappear in Guernica.

We should not forget that the military theme is ever-present in the period of A Coruña, especially after the Rif War fought in Morocco in autumn 1893. His scenes from those battles can be inscribed more within the mentality of an adolescent who sees war from a playful perspective or the viewpoint of a chronicler who was perhaps inspired more by the reproductions of La Ilustración Española y Americana ([17], p. 174) than by a critical position towards the violence of war at the time. However, those numerous drawings, made between 1893 and 1894, are the first graphic depictions by the young Picasso of the violence of war, represented directly and highly expressively, without alluding to cryptic or symbolic and caricaturesque images as he did in that particular double comic strip in Sueño y mentira de Franco. Here he reinforces the schematic and expressionist angle of the narrative, characterised by dynamism and immediacy, but its visual reading, and we can see as much in several models, among so many we could mention from his time in A Coruña, such as La batalla (1894)40 or Escena de una batalla (ca. 1893–1894)41 would suggest that there is a legitimate connection of concepts and forms between what was born at that time and what would come much later, when he took on a strong commitment and critical position against the destruction of war [47].

In this regard, A Coruña would not only mark his future artistic definition, but also the concretion of a part of his character and conception of life inasmuch as it impinges on certain stereotypes that cannot be separated from the culture and customs of a place and its inhabitants, particularly as regards humour and irony, disbelief and ambivalence and even stubbornness. This is where his sense of freedom was developed and also his sense of political progressivism as well as the moral conscience associated with the dispossessed, which was not just nourished in his own home, but in the strong example of his mentor, the oft-cited Doctor Pérez Costales. The city where the child’s and adolescent’s astuteness was fascinated by the history of the English general Sir John Moore and where he perceived the migratory phenomenon and the departure of soldiers for Africa from the privileged and everyday watchtower that saw boats entering and leaving the harbour ([6], pp. 48–49).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Rafael Inglada. “José Ruíz Blasco (1838–1913).” In José Ruíz Blasco (1838–1913). Málaga: Fundación Picasso Museo Casa Natal, 2004, pp. 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Rafael Inglada. “Picasso en A Coruña. La cronología (1891–1895).” In El primer Picasso. A Coruña 2015. A Coruña: Museo de Bellas Artes, 2015, pp. 385–399. [Google Scholar]

- Josep Palau i Fabre. Picasso Vivo (1881–1907). Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- John Richardson. Picasso. Una Biografía. vol. I, 1881–1906. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ángel Padín. Los Cinco Años Coruñeses de Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1891–1895). A Coruña: Servicio de Publicaciones, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ángel Padín. O Picasso Coruñés (1891–1895). A Coruña: Amigos dos Museos de Galícia & Xunta de Galícia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rubén Ventureira, and Elena Pardo. Picasso Azul y blanco. A Coruña: el Nacimiento de un Pintor. A Coruña: Fundación Rodríguez Iglesias & Fundación Emalcsa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de A Coruña-Xunta de Galicia. Catalogue, 2015. El primer Picasso. A Coruña, 2015. A Coruña, Spain: Museo de Bellas Artes, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Antón Castro. “Cuando el niño Pablo Ruiz pintó en A Coruña (1891–1895). Inicio de una revolución estética, la del siglo XX, el siglo de Picasso.” Gallegos 18 (2013): 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Antón Castro. “El Picasso coruñés como inicio inexcusable y referencia de su proyecto revolucionario (1891–1895).” Ars Longa. Cuadernos de Arte 22 (2013): 211–28. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Sam Houston State University: Huntsville, 1997–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Zervos. Pablo Picasso. Catalogue raisonné. Paris: Éditions Cahiers d’Art, 1932, 33 volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Luis Seoane. “La infancia gallega de Picasso.” In Luis Seoane. Textos sobre arte. Santiago de Compostela: Consello de Cultura Galega, 1996, pp. 274–278. [Google Scholar]

- Picasso, Jeunesse et Genèse. Dessins 1893–1905. (Catalogue); Paris: Picasso Museum, 1991.

- O Picasso Joven/Young Picasso. (Catalogue); A Coruña: Fundación Barrié de la Maza, 2003.

- Anne Baldassari. Picasso. Papiers Journaux. Paris: Tallandier, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rubén Ventureira. “Periódicos y caricaturas. El cronista Picasso.” In El primer Picasso. A Coruña, 2015. (Catalogue); A Coruña: Museo de Bellas Artes, 2015, pp. 164–205. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond Bachollet. “Picasso à ses Debuts.” L´Humanité, 4 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond Bachollet. “La Caricature politique.” Le Collectionneur Français, 1989, 7–10, December 1989, 7–9; October 1989, 7–9; November 1989, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond Bachollet. “Picasso et ses Débuts.” Le Collectionneur Français, 1999–2000, nos. 374, 376, 378, 383, 384, 388, 393, 394, 395. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond Bachollet. “Picasso à ses débuts.” In Raymond Bachollet, Pierre Daix, Jean-Pierre Jouffroy, Georges Tabaraud, Pablo Picasso et Gérard Gosselin. Picasso & la Presse. Un Peintre dans l’Histoire. Paris: L´Humanité & Éditions Cercle d´art, 2000, pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre Daix. L´art Dans la Presse. Paris: L´Humanité, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond Bachollet, Pierre Daix, Jean-Pierre Jouffroy, and Georges Tabaraud. Pablo Picasso et Gérard Gosselin. Picasso & la Presse. Un Peintre dans l´Histoire. Paris: L´Humanité & Éditions Cercle d´art, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- “Georges Tabaraud interview.” In Picasso et la Presse. Musée Picasso d’Antibes. (Catalogue); Musée Picasso Antibes/Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2000.

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.93:007. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.94:019. [Google Scholar]

- Brigitte Leal. “L’enfance d’un chef.” In Picasso Jeunesse et Genèse. Dessins 1893–1905. Paris: Réunion des Museées Nationaux, Picasso Museum, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.94:018. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.94:015. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.94:016. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón María Tenreiro. “Una visita a Picasso.” Alfar: Revista de Casa América Galicia 26 (1923): 174–76. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.94:017. [Google Scholar]

- Michel Melot. “Le Modèle imposible. Ou comment le jeune Pablo Ruíz abolit la caricature.” In Picasso Jeunesse et Genèse. Dessins 1893–1905. Paris: Réunion des Museées Nationaux, Picasso Museum, 1991, pp. 58–87. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel Barrero. “Orígenes de la historieta española, 1857–1906.” Arbor 187 (2011): 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Pierre Jouffroy. Un Fondateur de la Deuxième Renaissance. Paris: L´Humanité, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.93:018. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.93:011. [Google Scholar]

- Gérard Gosselin. Picasso La Politique et la Presse. Paris: L´Humanité, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ségolene Le Men. “La recherche sur la caricature du XIXeme siècle: État des lieux.” Perspective 3 (2009): 426–60. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.94:137. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.95:074. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.95:073. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.95:116. [Google Scholar]

- John Berger. Fama y Soledad de Picasso. Madrid: Alfaguara, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador Haro, Inocencio Soto, and Claustre Rafart i Planas. Viñetas en el Frente. (Catalogue); Barcelona: Institut de Cultura/Museu Picasso, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.37:056. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique Mallen. Online Picasso Project. Hunstville: Sam Houston State University, 1997–2017, OPP.93:012. [Google Scholar]

- 1In his Online Picasso Project, Mallen gives the fullest diachronic account of the works from this crucial period in Picasso’s formation, extending Christian Zervos’s classic reference catalogue [12].

- 2Seoane maintained that Picasso produced these hand-made newspapers to send to his relatives in Andalusia, instead of letters.

- 3Their printing works were at Calle Zurbano, 28.

- 4Baldassari says that Picasso’s attraction to these publications is similar to that he felt as a collector of old photographs: portraits, visiting cards, orientalist prints or ethnographic documents and reproductions of works by the old masters.

- 5MPB (Museo Picasso Barcelona): 110.863 R.

- 6MPB: 110.863.

- 7MPB: 110.863.

- 8MPB: 111.489 to 111.512, 112.481 and 112. 482 (La Coruña, 1894–1895).

- 9MPB: 111.396 to 111.425 R, 112.479 and 112.480 (La Coruña, 1894).

- 10MP (Picasso Museum Paris): 403R.

- 11Z. XXI, 15 and Z. XXI, 16. It belongs to a private collection. It could indeed be from A Coruña if we assume that the date given on it, 1895, refers to the Christmas period in 1894–1895, in which case he could have produced it in the new year. Otherwise, and most probably, we are speaking of Christmas 1895, by which time he had settled in Barcelona.

- 12MP: 402R.

- 13Note that he makes a spelling mistake, turning bañarse (“bathe”) into vañarse. He corrects it in the next phrase: Como se bañan los de Betanzos (“How people from Betanzos bathe”).

- 14The director of the Picasso Museum in Paris and expert on the artist goes so far as to say that the caustic irony he employs bears witness to the unconstrained tone that prevailed in the family circle, and urges us to qualify the description often made of his father, who is commonly reduced to the inoffensive figure of a minor academic painter.

- 15The alborada (dawn song) is a classical and popular musical composition in a poetic and lyrical vein devoted to the early morning and closely linked to Galician fiestas and pilgrimages. Some of them became well known and were set to music with words by the late Romantic poetess Rosalía Castro, which the young Pablo must have known, since we know that he not only greatly admired her but read some of her works and even recited them, as Antonio Olano recalls.

- 16Picasso was very familiar with the story of this heroine of the city of A Coruña, and is even accurate in the dates. María Mayor Fernández de Cámara y Pita (1565–1643), better known as María Pita, was indeed the heroine who defended the city in 1589 against the British navy, commanded by the pirate Francis Drake. The siege took place on 4 May, with the attack on the city, whose walls were breached by over 10,000 troops under the command of an ensign. With a cry of “If you have any honour, follow me!”, María Pita not only got rid of the ensign but also managed to encourage the local troops and get the civil population involved in the fight to repel the English.

- 17The cucaña (greasy pole) is a game that was very successful in popular rural fiestas. Competitors tried to climb a pole using their hands and legs.

- 18“La décennie qui s´ouvre en 1950 est marquée par la participation de Picasso á la presse communiste”.

- 19A popular French newspaper founded in 1889, which continued in circulation until the early 1900s. It was aimed at young people and was published in a format of sequences of highly realist drawings with a text below. Published by Armand Colin, Paris.

- 20This term did not arrive to Spain and replace the historieta until the early twentieth century. The term comic arrived even much later ([34], p. 32).

- 21The portrait he did of Dr Pérez Costales in 1895 was one of the paintings from A Coruña that Picasso never wanted to be parted from and that normally hung on the walls of one of his homes.

- 22The exhibition took place in 2010 (21 April–30 August) and clearly showed the artist’s political activism and combative character, though a selection of 150 works.

- 23MPB: 110.927. Imprenta y Librería A. Landín. Pontevedra, 1889, 181 pages (each page: 20.7 × 13 cm). Bound in cardboard, leather spine and embossed in gilded letters. MPB: 11.927.

- 24Sagasta (1827–1903) was an everyday figure during Pablo’s childhood, given that he was Prime Minister during the Regency of María Cristina, after the death of her husband King Alfonso XII.

- 25MPB: 110.927.

- 26This author makes a categorical assertion when he maintains that Picasso’s first drawings contain the seeds of the revolution he brought about in 1907, the Cubist revolution, which he was to make permanent: “regrouping his earliest drawings makes it possible to see how this evolution was already inevitable in his adolescence”.

- 27MPB: 110.860 R. This is the dating of the Museu Picasso de Barcelona, although personally I consider that the work is a little later, because the style of the drawings and the narrative procedure match the period of the newspapers, very much along the lines of the October 1894 Azul y Blanco or the albums.

- 28Z. XXI: 20. Pencil on paper on paper, 20 × 15.5 cm. Private collection.

- 29MPB: 111.491. Dated 1894–95. I shall refer to this caricature when discussing the subject of bulls and bullfighters.

- 30Z.VI: 49. It is usually dated to 1895, but I disagree with this dating and consider that it is from late 1892, when he was attending classes in Ornamental Drawing with his father, during the 1892–1893 academic year, with enrolment number 88. In August that same year he had attended half a bullfight by El Toledano in the A Coruña bullring, an event of which he left a record in several drawings, to which I shall refer later. Ink and pencil on paper, 13.5 × 21 cm. It sometimes appears under the title Español y monje [Spaniard and Monk]. It currently belongs to the Fundación Caixa Galicia Collection in A Coruña. It was acquired from Galería Guillermo de Osma in Madrid and is the reverse of Escena popular gallega, which probably is from 1895.

- 31Z.VI: 37. Indian ink on paper, 18 × 25.5 cm, Picasso Estate/Administration, Paris.

- 32MPB: 110.375. Ink on paper, 19.7 × 27.9 cm, Museu Picasso Barcelona.

- 33MPB: 110.870 and 110.905.

- 34MPB: 110.870 R.

- 35MPB: 110.648.

- 36MPB: 110.377, ca. 1895. Ink on paper, 27.4 × 19.9 cm, Museu Picasso Barcelona.

- 37Could be dated between 1892 and 1893 and was published in Gaceta de Bellas Artes, Real Academia Gallega, A Coruña.

- 38Berger writes: “To exaggerate this distinction, as Picasso does here, until lie and truth are reversed [he defines Art as a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand], suggests that part of him still believes in magic and has remained fixed in his childhood.”

- 39The exhibition confronts the two etchings, each one consisting of nine vignettes, and some other works by Picasso, with those by other artists like Goya—including his Disasters of War—and also John Heartfield, George Grosz and Josep Renau, showing their commitment against war and the violence it leads to. Etching and aquatint on paper, 31 × 42 cm. Similarly to Guernica, they were made for the Spanish Pavilion at the Exposición Internacional de Paris de 1937. An edition of 1000 was produced to raise funds for the Republican side in the Civil War.

- 40Z. XXI, 8. Indian ink on paper, 13.5 × 17.5 cm.

- 41MPB: 110.610. Ink on paper, 13.3 × 20.9 cm.

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).