Fugoppe cave is located on the island of Hokkaido, in the north of the Japanese archipelago. Petroglyphs found here and at another cave a short distance away are unique in Japan and lack a comparative dating context. Direct dating methods for the Fugoppe Cave petroglyphs are ruled out, as materials that could be tested by direct methods have not been recovered. Therefore, to establish reasonable dating for these works, a relative dating method is required, and has been employed here, based on a range of evidence compiled over the years since their discovery in 1950 (

Figure 1).

The main techniques employed for the petroglyphs at Fugoppe are abrasion and pecking (

Figure 2). Pecking is common in the context of North-east Asian rock art, which would allow the comparison of Fugoppe with other examples from the area. Abrasion, on the other hand, is so unusual that it is difficult to assign a date to Fugoppe from this evidence (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Map of Hokkaido, indicating Fugoppe Cave.

Figure 1.

Map of Hokkaido, indicating Fugoppe Cave.

Figure 2.

Examples of technique: abrasion (left) and pecking (right).

Figure 2.

Examples of technique: abrasion (left) and pecking (right).

Figure 3.

Abraded figure, showing red pigmentation.

Figure 3.

Abraded figure, showing red pigmentation.

Figure 4.

Abraded quasi-human figures.

Figure 4.

Abraded quasi-human figures.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show examples of the Fugoppe petroglyphs. The quasi-human figures were made by abrasion techniques, including chipping, slicing, diagonal cutting and similar methods. The sharp edging of outlines is an original feature. There are remains of red ochre within abraded parts, leading to the supposition that the Fugoppe figures possessed fuller red coloration at their execution; however, direct dating of the ochre remnants has yet to be attempted.

The mixed presence of these two techniques, I suggest, may have been due the nature of the rock surface. The artists here, as elsewhere, may have first attempted pecking on the fresh walls, without achieving good results; the rock at Fugoppe is a kind of hard igneous rock called hyaloclastite, unsuitable for pecking to make clear figures. Hence, the art makers may have developed the technique of abrasion here to improve their results. At nearby Temiya Cave (see below), the only technique used was pecking. My speculative scenario would involve travelers with a rock-art tradition arriving in Hokkaido from the Eurasian Continent, using their accustomed technique first at Temiya, before developing the new abrasive techniques at Fugoppe (see Notes 1 and 2).

At Fugoppe, these two techniques were probably employed at around the same time, the artists having adapted their methods according to the quality of rock surface. From an art-historical perspective, the Fugoppe figures have a stylistic unity across the available rock surface, which extended around 5 m from bottom to top. In my view, all the artworks at Fugoppe are likely to have been created within a single generation, i.e., 20–30 years. Including the Temiya Cave examples, Hokkaido’s petroglyphs may indicate a unique culture encountering the Japanese archipelago by chance; if so, it is necessary to consider when this event, which resulted in rock art of a type unknown elsewhere in Japan, occurred. This is the main purpose of this paper.

When the Fugoppe petroglyphs were discovered in 1950, during the first survey of the site, most of the rocks support with engraved figures were covered by layers of natural and archaeological debris, such as discarded shells and earthenware fragments. The ceramic debris was dated by archaeologists to Hokkaido's Post-Jomon era,

ca.1900–1300 BP (

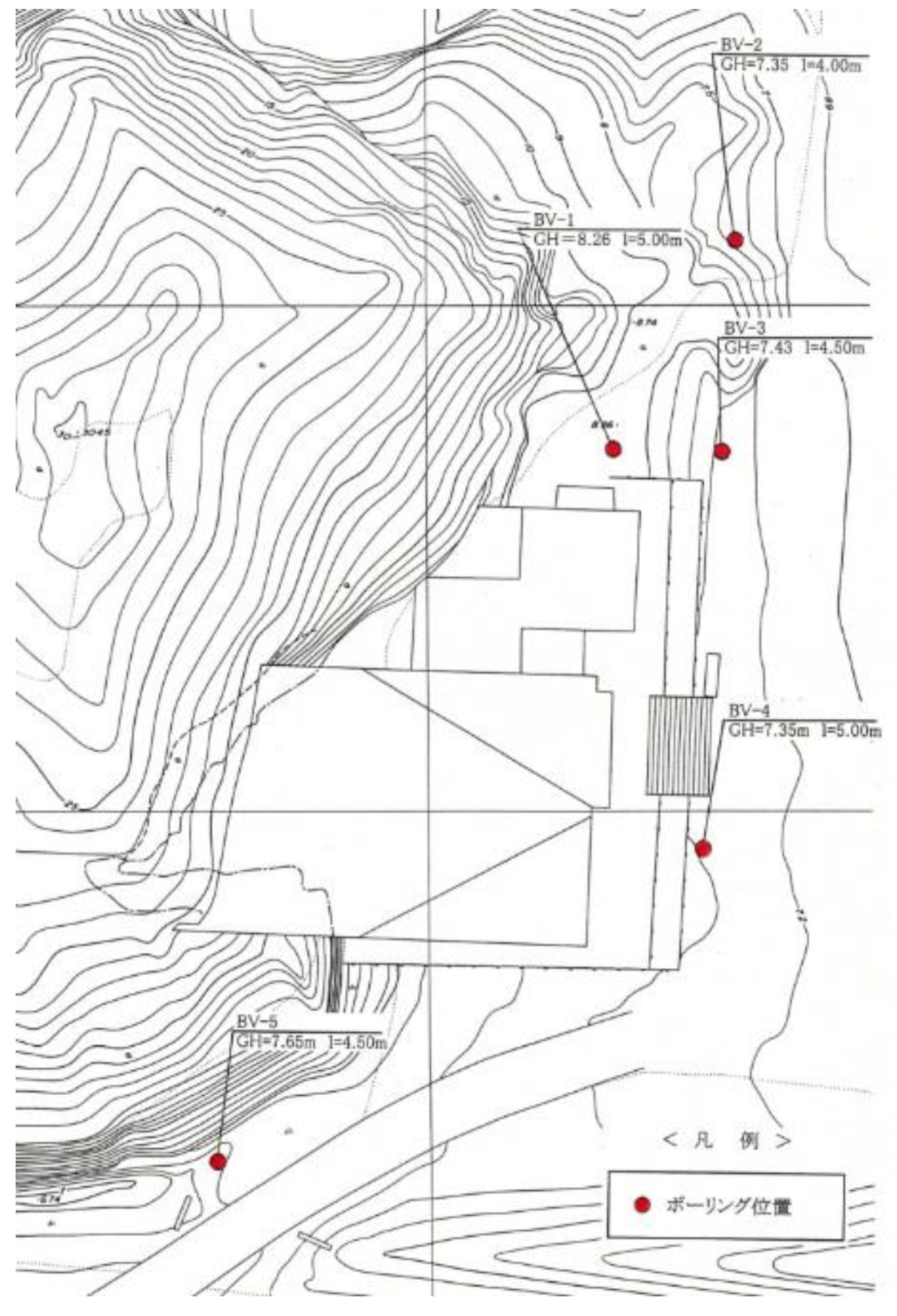

Figure 5). In 1999, our research team took five bored samples around the site (

Figure 6). The team geologist concluded that the cave itself was made by wave action when warming climates led to the sea encroaching on to the land (even today, Fugoppe Cave is only 200 m from the seashore); this occurred at intervals around 6000, 4000 and 2000 years ago. Thus, the latest date for the cave’s creation is 2000 BP, and indeed no trace of earlier human presence has been found; 2000 BP is therefore the oldest possible date for the creation of the petroglyphs.

Figure 5.

Soil covering (shaded areas).

Figure 5.

Soil covering (shaded areas).

Figure 6.

Bore locations (red points).

Figure 6.

Bore locations (red points).

In addition, we submitted four pieces of shell for AMS dating, which indicated absolute dates of about 2000 BP (

Table 1). Together with the bore results, our archaeologists interpreted the sterile layer as accumulating after the last marine advance of 2000 years ago (

Table 2). Following this, the site and surroundings stabilized and then came to be occupied by people of the Post-Jomon era for around 600 years, between 1900 and 1300 BP, as suggested by the seashell and earthenware debris.

Table 1.

Table of AMS (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry) dating.

Table 1.

Table of AMS (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry) dating.

| No. | Materials | Raw data | Calibration | Historical Date |

|---|

| Beta-140911 | Sea shell | 1620 ± 30 | 2040 ± 30 | 3rd Century AD |

| Beta-140912 | Sea shell | 1590 ± 30 | 2030 ± 30 | 3rd Century AD |

| Beta-140913 | Sea shell | 1670 ± 30 | 2110 ± 30 | 3rd Century AD |

| Beta-140914 | Sea shell | 1600 ± 40 | 2020 ± 40 | 3rd Century AD |

Table 2.

Table of chronology, Hokkaido and Honshu (rest of Japan).

Table 2.

Table of chronology, Hokkaido and Honshu (rest of Japan).

| Hokkaido | Honshu |

|---|

| Jomon(~BC2C) | Jomon(~BC3C) |

| | Yayoi(BC3C~AD3C) |

| Post-Jomon(BC2C~AD7C) | |

| C2D Style(AD3C~4C) | Kohun(AD3C~AD7C) |

| Satsumon(AD7C~AD12C) | Historical Ages(AD7C~) |

In the original 1951–1952 excavation, around 60 fallen petroglyph rocks were discovered; these are now deposited in the Hokkaido Historical Museum at Sapporo (

Figure 7). According to the official report published in 1970 by the Fugoppe Cave Excavation Party (FCEP), the rocks were discovered from all the archaeological layers present, and from all areas of the site. Some rocks are large, but portable, while the rest are quite small.

Figure 7.

Rock with petroglyphs.

Figure 7.

Rock with petroglyphs.

One rock, according to a note attached by its discoverer, lay at the deepest level, near a massive rock estimated by an archaeological geologist to have fallen in an earthquake about 1900 years ago (

Figure 8). It seems reasonable to suppose that this rock was dislodged by the earthquake, and I believe it is likely that all the petroglyphs were already in place at the time of the earthquake. In

Figure 8, the point marked ‘0 cm’ is at the same level as the massive rock; 12 other petroglyph rocks were found scattered at considerable variations of depth, from 30–290 cm. Because of the instability of the rock surfaces at Fugoppe, I argue that the decorated rocks would have been coming loose and falling from the walls continually over centuries. The lowest layer also contained fragments of earthenware from the early Post-Jomon period,

ca.1900 BP. More rock fragments and earthenware had accumulated at depths around 3 m up to the time of the cave’s main occupation, about 1700 years ago. This suggests that when people first occupied the site, the petroglyphs were already present and falling, and over the occupation period continued falling to the then-current level of occupation.

Figure 8.

Plan of excavation, showing location and depth of scattered petroglyph rocks.

Figure 8.

Plan of excavation, showing location and depth of scattered petroglyph rocks.

The occupants seem to have paid scant attention to these petroglyphs, if indeed they noticed them at all. There is evidence that some of the rock in the cave had been used for tool-making purposes, and the overall implication, to my mind, is that the petroglyphs held no intrinsic value to this community; they did not feel the scattered rocks were worth moving, and indeed they were sometimes prepared to use them for their own purposes, regardless of the carvings. To them, perhaps, the petroglyphs were ephemeral graffiti.

From this evidence, and from the fact that the archaeological layers were continuous and showed steady development in earthenware style, it is possible to conclude that the figures were executed by people around 1900 BP–earlier visitors than those who occupied the site from 1700–1500 BP.

Within Japan, controversy remains on this point. Between myself, as an art historian, and Japanese archaeologists, there is a wide divergence in the dating of Fugoppe’s petroglyphs. Archaeological focus tends to be on the major occupants of the site – in this case, the people who made the pottery complex named Kohoku C2D style, which comprises more than 80% of the remains from Fugoppe. Kohoku is an abbreviation of KOki HOKkaido (Later Hokkaido) Culture, and the duration of Kohoku C2D style covered the two centuries between 1700–1500 BP. Archaeologists in general have a tendency to assume that the dominant occupants of a site are responsible for its principal cultural heritage, in this case the distinctive petroglyphs.

While this is a reasonable assumption in general, in this instance I would propose that the petroglyphs are not the work of the site's dominant cultural identity. We may cite as an example the concept of sanctuaries in Franco-Cantabrian parietal art, where the venues for rock art seem to have been kept clean, leaving only artworks without other remains of everyday life. Thus, we cannot necessarily attribute artistic phenomena to the dominant people occupying the sites.

Getting a relative date for prehistoric art is not a simple process, but a complicated matter of combining circumstantial evidence. To conclude this brief dating survey, I would strongly argue that the evidence described above implies that the petroglyphs from Fugoppe Cave were made before 1900 BP, rather than the customary dating of Japanese archaeologists to the so-called Kohoku C2D era, i.e. 1700–16,00 BP.

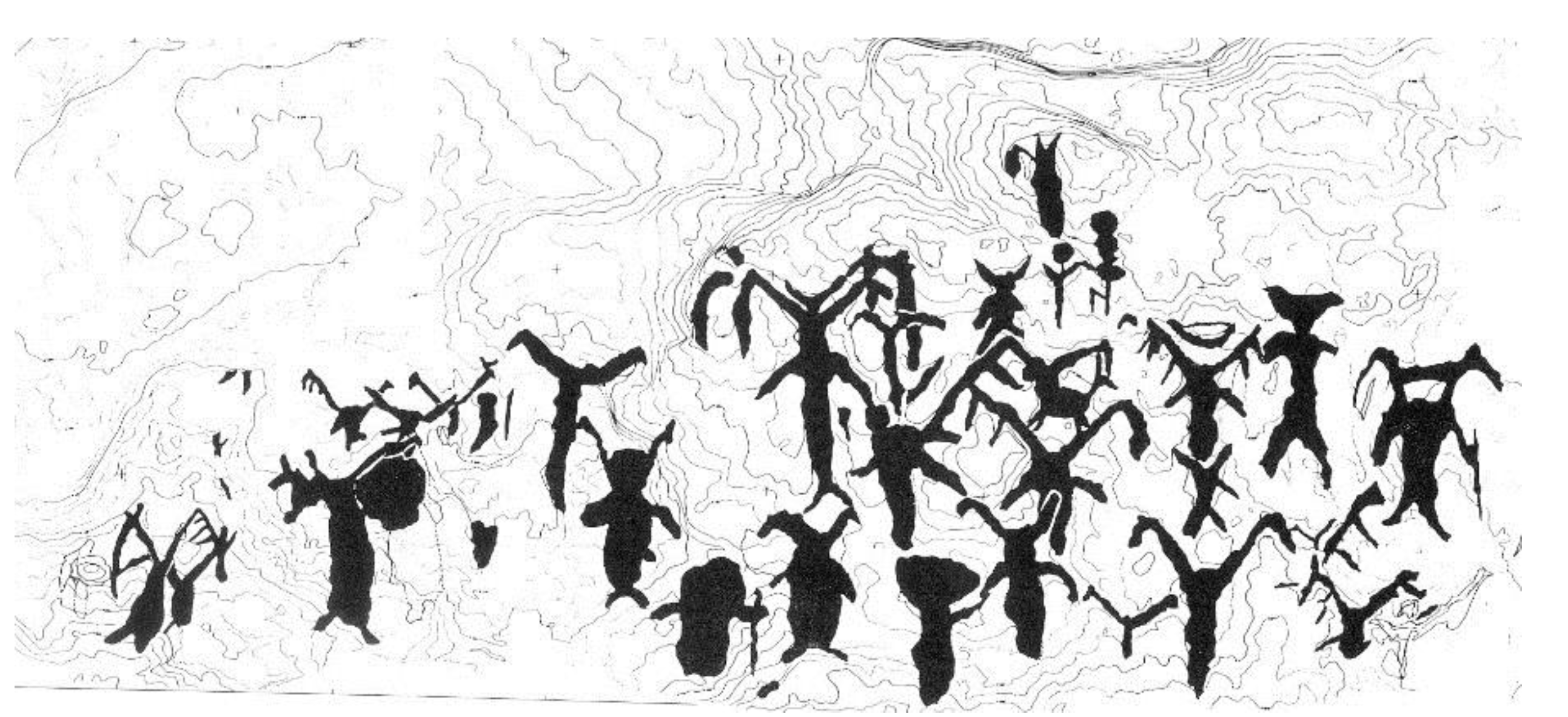

The question then is, who were the artists of Fugoppe Cave? In 1866, petroglyphs were found in Temiya Cave, 15 km away. Among these carvings were 35 human figures (

Figure 9) with similar stylistic features to the Fugoppe figures. Although the Temiya petroglyphs were made by pecking only, whereas a variety of techniques were employed at Fugoppe, this is likely to be due to the relatively harder and abrasion-resistant nature of the Temiya rock. The two caves are, I would argue, contemporary, and used by people of the same culture.

Figure 9.

Petroglyphs from Temiya.

Figure 9.

Petroglyphs from Temiya.

This may address why we have not found such rock art in other parts of Japan. Is it because other petroglyphs have all weathered away, or perhaps that population expansion has destroyed them without realizing their existence? We have to wonder whether it is only in Temiya and Fugoppe that such petroglyphs were ever to be found in Japan, and thus whether their creators were from outside the Japanese archipelago.

Notes

Fugoppe Cave was created by wave action, resulting in the kind of horizontal lines seen in the right-hand illustration in

Figure 2. This is not horizontal stratification in the hyaloclastite, which seems to have been unsuited to pecking when discrete forms were required.

Abrasion is a locally unusual technique and at first glance some of the human figures might seem to be natural fissures. However, fieldwork indicates that these are artificial designs, averaging 10–30 cm in size; relative consistency in scale and design indicates they are of human rather than natural creation.