Abstract

Hand stencils and prints are found globally in rock art, reflecting the sine qua non role of the hand in human evolution. The body itself is the tool, and it affords the registering, in the form of a trace, of what perceptual psychology terms an “ecological self”. More than a “signature”, a hand mark is uniquely “proprio-performative”, combining inscription of individuality with direct address. The first part of this paper looks at what might get in the way of a universally readable primary meaning by methodically addressing issues of technique and cultural specificity. Having cleared the ground, it proceeds to make its argument for hand stencils and prints as constituting a special category of rock art imagery. It does this by having recourse to ideas currently under discussion in cognitive psychology: awareness of self-agency and body-ownership, as well as the notion of perceived looming in pictures. Finally, an appeal is made to the claim for a key mirror neuron role in communication. Because they are traces of actions eliciting mirror-neuronal responses, hand marks are seen as affording a readily accessible external term in an exchange of meaning on which a system of graphic communication might be built.

1. Introduction

The intricate architecture of the human hand, which endows our species with manipulative dexterity outside the range of its nearest relatives, makes it our principal organ for exploring the world. In his classic 1980 text, Hands, John Napier went as far as asserting that the function of the sapiens sapiens hand in the cardinal act of negotiating environments gives it “advantages over the eye”, for “it can see around corners and it can see in the dark”. What is more, its operation from the end of manoeuvrable arms allows for directed movement at a distance from the body ([1], p. 8). The mutual reinforcement of haptic and visual information in perception is supported by the theory of J. J. Gibson (1904–1979)—influential in the study of vision and related systems—who affirmed: “Many of the properties of substances are specified to both vision and active touch”. Gibson argued that once we become aware of the “exploratory”, as well as the more obtrusive “performatory” function of the hand, i.e., its role in seeking information as well as performing actions, it comes into focus for us as “a sense organ” ([2], p. 104, p. 123). The present paper relies on insights drawn from perceptual psychology and cognitive science about these functions, asking questions about how it is we recognize ourselves as originating an action, and what we understand about ourselves from our interactions with the world. It argues that hand stencils and prints register the hand’s exploration of an affordant surface by capturing an image of the performatory act. This records the agent’s ownership of that act and opens up the possibility of direct address to another person as well as offering options for symbolic forms of communication.

2. The Hand’s Evolution

The hand’s capacities have been with us since the time of our ancient antecedents. Recent evidence from 3.39 Ma bones bearing cut marks, found at Dikka, Ethiopia [3,4], suggest that australopithecines—who appear to have possessed the hands necessary to use pebble choppers to pound, chop and dig ([5], p. 455)—did in fact use such tools. However, the earliest finds of manufactured tools, from Gona, Ethiopia, date from about 2.5 million years ago [6]. When in 1960 hand bones suggesting grasping capabilities [7,8] were found at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, with apparently manufactured tools dated at around 1.75 million BP, a benchmark was set for investigating the relationship between primate hand morphology and possible tool use. Although “Oldowan tools” which predate Homo habilis—“Oldowan” and “habilis” both named as a consequence of the 1960 discoveries—have been found with australopithecine remains, archaeologists have not wanted to make claims for a tool-making species exhibiting smaller brain size than that of the habilines. With the appearance of Homo erectus about 1.5 million years ago came the long-lasting, more specialized Acheulian toolkit, and with Homo sapiens, especially in the last 100,000 years, tools which were even more task-specific ([9], pp. 110–115).

From the point of view of comparative primate hand morphology, the hominin hand possesses a number of special attributes. These include an opposable thumb—which apes also possess—and rotational abilities in the index and fifth fingers. Marzke and Marzke characterize the modern human hand as allowing flexibility in the thumb’s opposition to the other four fingers without compromising thumb-to-index finger grips. Affecting the hand’s control over an object, human thumb length is longer in relation to the index finger than for our near relatives [8], and grip is aided by ample and malleable pulp-contact at finger ends [8,10]. Humans grip more powerfully than other primates ([11], p. 108).

It was the hand as performatory which preoccupied Darwin when, with the 1871 publication of the Descent of Man, he drew attention to its critical role in determining our place in the ecosystem:

Man could not have attained his present dominant position in the world without the use of his hands, which are so admirably adapted to act in obedience to his will... But the hands and arms could hardly have become perfect enough to have manufactured weapons, or to have hurled stones and spears with a true aim, as long as they were habitually used for locomotion and for supporting the whole weight of the body...([12], p. 279)

The drawing of a connection between bipedalism and the freeing of the hand for tool use is currently under intense discussion as biologists seek to throw light on the relationship between these evolutionary events, with questions asked about the “when and how” ([13], p. 1566) of the adaptive sequence. In 1964, while assessing Homo habilis fossils found at Olduvai Gorge in collaboration with (Louis) Leakey and Tobias, Napier noted both differences and resemblances when habilis hand bones were compared with those of sapiens sapiens ([7], p. 8). Since then research has focused on the evolution of hand morphology, although a scarcity of hand bone fossil evidence makes this difficult—despite improved techniques in comparative analysis [8,14]. Recent investigation has raised the question of a correlated evolution of hands and feet, with Rolian et al. [13] arguing for parallel development. Anatomical inquiry emphasizing biomechanics has led to neurophysiological investigations, with experiments by, for example, Peeters et al. [15] pointing to an evolved human brain area, which relates to causal awareness in tool use. In experiments with macaques, Gross et al. [16] accidentally triggered a specific neuronal response to a waved hand in the inferotemporal cortex (the processing area for objects). Following this, a substituted monkey or human hand shadow produced the same result. It has long been recognized that the representation of the human hand, together with that of the face, takes up a large area of the brain, as proportionally illustrated by Penfield and Rasmussen in 1950 ([17], p. 44, Figure 17).

The hand is emerging as central to the evolution of human communication, with Arbib supplying the “missing link” in the emergence of language by arguing for the recruitment of mirror neurons—which developed in relation to grasping actions—in response to an enlarging repertoire of manual gestures [18]. Rizzolatti et al. have reviewed evidence from brain-imaging experiments in support of motor system resonance while observing an action (“the direct-matching hypothesis”), claiming a common activation location for “observed arm or hand actions” and speech, viz. Broca’s area, “a region traditionally considered to be exclusively devoted to speech production”. They justifiably see this as suggesting “an interesting evolutionary scenario, linking the origin of language with the comprehension of hand actions” ([19], p. 664) [20]. Arbib has proposed a proto-Broca’s area possessed by Homo habilis and erectus that primed the species for language-readiness. On this neurolinguistic hypothesis, a role for vocalization recedes, and manual gesture comes to the fore as having a foundational role [18].

The capacity of the hand, either as direct instrument in the case of finger flutings, stencils and prints, or for the manipulation and manufacture of tools, is understood in rock art studies, but only a small number of rock art researchers focus on its role in cognitive evolution. Indeed the hand in all its aspects is inescapably chief protagonist in any story of rock art. Setting the scene for the advent of art, Lorblanchet links several important symbiotic factors (“une symbiose de processus”) in which it is not easy to disentangle cause and effect. These are a postural shift to bipedalism, hands freed for tool-manufacture and mouth freed from merely obtaining food, increased dexterity in the employment of hands, and an altered brain ([21], p. 58). Whatever the complications of this symbiosis, the hand is to be understood as crucial to survival and integral to species definition (Figure 1).

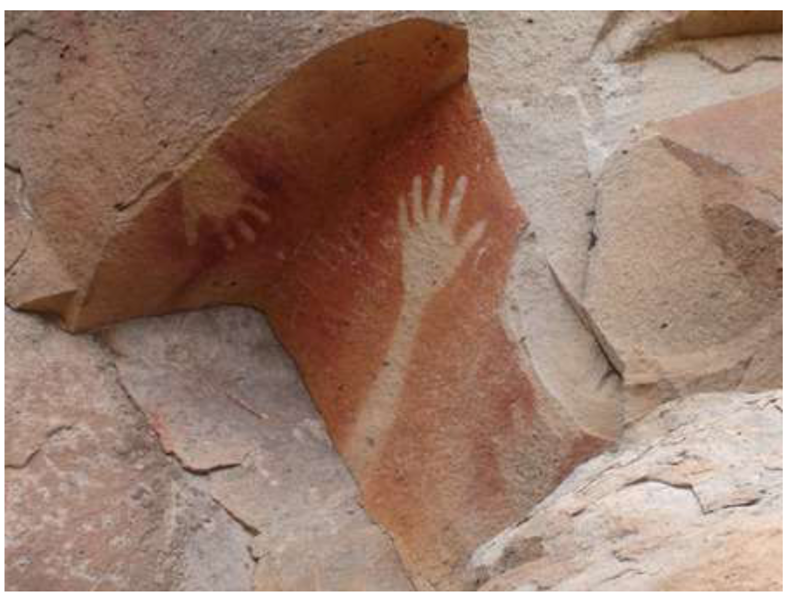

Figure 1.

Painted hand, Madhya Pradesh.

3. The Longevity of Hand Stencil- and Print-Making

In view of this, should it surprise us that perhaps the most tantalizing manifestation of human marking around the world, with an antiquity of its own, is the stenciling and printing of the human hand? In mid 2012 the 27,000+ BP date for Cosquer, France ([22], pp. 78–79) appeared to be overtaken by El Castillo, Spain, when Pike et al. [23] published their uranium-series calculation of at least 37.3 thousand years for a hand stencil and 40.8 for a red disc. Aware of the difficulties of this type of dating analysis, Bednarik [24] recommends caution in accepting the result. Still, the Pike et al. claim raises the possibility, supported by broader evidence of robust populations, that the images were made by Neanderthals [23]. Marzke and Shackley, describing Neanderthal hands, assert their skeletal similarity to those of modern humans, but note possession of “large muscles” ([5], p. 454). It is astonishing to think that in one instance we might be looking at the image of a Neanderthal hand and in another that of a contemporary modern who is nonetheless an inheritor of this particular rock art tradition. It is a fact that in Australia both stencils ([25], pp. 74–75; [26], p. 12) and positive prints ([27], p. 30, p. 32) have been made by Aboriginal people within living memory. There is also evidence of tribal groups in Central India continuing hand printing practices at rock art sites ([28], p. 380).

A 37.3 thousand minimum date aside, taphonomic considerations [29,30] prompt us to rule out hypothesizing a time-frame for the first appearance of hand stencils and prints. Their genesis must be in the exploratory activity of the hand as it leaves a trace of itself; their antiquity as long as that of the hand which was capable of making a mark. The unanswerable question is: when did casual marks become intentional? In the present context, another question might be asked: is there a rationale for focusing on stencils and prints? After all, directly imprinted hand images, either positive or negative, have obvious affinity with other hand-made marks not involving tools. Findings at Cosquer suggest that stenciled and printed hands were contemporaneous with finger flutings ([22], p. 63). What puts them in a different category from finger flutings like those of Cosquer or (to give Australian examples) Koonalda or Karlie-ngoinpool caves, is their quasi-representational iconic character. A clear and distinct image of a hand will be recognized as a hand. Like stencils and prints, flutings retain visual testimony of how (and by whom) they were made. What gives the former a special status among early rock art forms, and one that opens out a separate line of inquiry into their defining features, is their iconicity. This cannot be said for all variations of the hand mark. For example, images of the palms of hands, such as we find at Chauvet, will not qualify as iconic. The makers of these palm-blobs may well have been identifiable by others within the group attending to the size and other characteristic features of the prints, but the fact that their production by pads rather than palms lends itself to creating non-hand images—for example, for producing the profile of an animal ([31], p. 157, p. 71)—means that they are very different in kind from the hand-recognized-as-hand class of image. This is also the case for the triangular “masked stencils”, ancient or recent, occurring in Arnhem Land, Australia [32]. However, the category of the iconic hand will extend to hands with bent fingers, provided the aim is not to depict a quite different iconic image such as a bird or animal head. The general class of recognizable hand images will of course include painted, drawn and petroglyph representations. However, only stencils and prints have the special quality of directly replicating the hand that made them.

Accordingly, taking their iconicity as a given, but with no intention of dismissing the subject of their possible use within a language of symbols, I propose to look again at a range of matters which have concerned students of this particular category of hand images. My aim in addressing issues of technique and cultural specificity is to rule out what does not bear on my argument and to foreground what does. I shall also examine what hand stencils and prints have in common with those of the human foot. When I make my case for a special proprio-performative category for rock art hand marks, ancient and modern, I shall explain why painted, drawn or petroglyph hand images are excluded.

4. Technique

From Régnault’s “tamponnage” application method to Breuil’s tube of bone (cf. the claimed blow-pipe technique of Lascaux), the technique of making hand stencils has been a hot issue in rock art studies ([33], p. 46; [34], p. 45, p. 144)—until, that is, the majority of Anglophone researchers settled down to the view represented in IFRAO’s Rock Art Glossary English definition which specifies a spraying of pigment “usually from the mouth”. It is interesting that the key verb used in the French definition of “main en negative” is not the equivalent of “to spray” (“vaporiser” or “atomiser”), but “répandre” (“spread” or “diffuse”)—with no mention of “la bouche” ([35], p. 16, p. 88). This seems to leave the matter undecided, with the French definition reflecting the French debate. Breuil’s collaborator at Gargas, Cartailhac, proposed that dry powdered color was projected onto a moist surface, thus becoming fixed. Other methods have been canvassed: Groenen suggested the use of a vaporizer made of two small tubes at a right angle, and Lorblanchet, with the experience of working in Australia, where such a method had been recorded, mixing of saliva and pigment in the mouth prior to spitting ([36], p. 121). Barrière and Sueres, who examine all these proposals, opt for a version of the Lorblanchet suggestion [33]. Breuil had previously referred to blowing from the mouth “in the manner of the Australians” ([34], p. 45), suggesting this as an Aurignacian method. Something of this conversation about technique is surely reflected in Keyser and Klassen where stencils at Wyoming sites are said to have been made by “blowing paint through a tube or spitting it directly from the mouth” ([37], p. 7). In Santa Cruz, Argentina, Breuil lives on in the ochred tube model exhibited at the Cueva de las Manos tourist center—justified by the find during excavations of a tube, stained red and bearing signs of use ([38], p. 245)—although researchers at Cueva de Las Manos also take up the spreading/spraying from the mouth option ([39], p. 27). A bone tube carrying remnants of ochre was also found at Les Cottés, Vienne ([36], p. 119).

From Australian ethnography, two accounts are worth mentioning. The first can possibly be sourced to the 1880s, when a boy growing up with Aborigines on the Darling River, western New South Wales, might have observed at close hand the blowing-from-the mouth method he advances half a century later. McCarthy quotes G. K. Dunbar’s recollection: “women and children expressed their desire for the creation of some artistic object by filling the mouth with a mixture of kopi (white clay) and blowing it over the hand placed against a rock” ([40], p. 74). The second is Herbert Basedow’s 1925 testimony of a method, which, he confidently asserts, “is met with all over the continent”:

The person puts a small handful of ochre or pipe-clay into his mouth and crunches it to a pulp; then he fills his mouth with water and thoroughly mixes the contents. He holds the hand he wishes to stencil against a flat surface, spacing the fingers at equal distances, and spurts the contents of his mouth all about it. A short while after, the hand is withdrawn. The area which it covered remains in its natural condition, whilst the space surrounding it has adopted the color of the ochre or clay.([41], p. 321)

A more recent Australian account of this method being used in the Kimberley in the 1930s is cited by Mulvaney ([26], p. 17), and Tresize ([42], p. 198), familiar with Cape York practices, takes it as a given.

Common to these descriptions is the assumption that the human hand is held to the rock face to register its form. While speculation about what is a global activity suggests that it might have involved varying techniques across space or time—and must mean different things in different situations ([21], p. 218; [43], p. 98)—we can be sure that the act of leaving a recognizable trace of one’s hand on a surface by direct contact is what ultimately facilitates an investment of cultural meaning. This is not a matter for dispute and provides one of the planks in my argument for a special category of rock-marking for hand stencils. I would also add prints (called “impressed hands” in some contexts [44]) to the category, since they satisfy the criteria of surface contact and the capture of idiosyncratic form through trace. Unlike the “negative imprint” (the expression employed by Basedow), the “positive” does not provoke dispute about its execution. Basedow’s straightforward Australian description is unlikely to meet with opposition: “At times... the hand is smeared with ochre and smacked again [sic] a surface to obtain a positive” ([41], p. 322).

5. Cultural Specificity

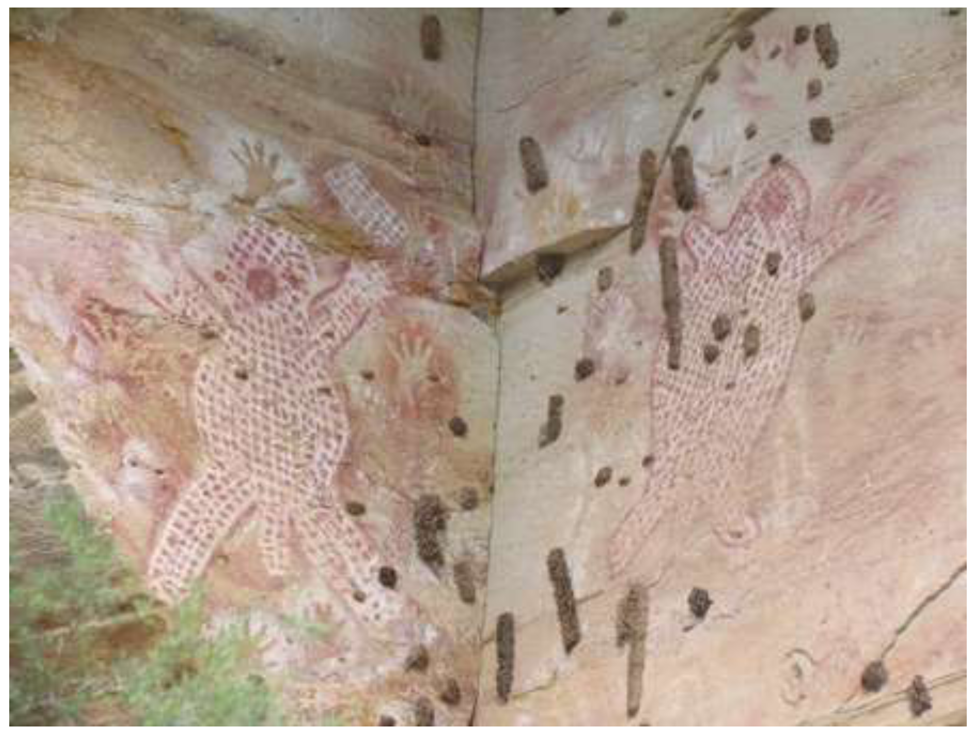

While ethnography relating to hand stencils and prints can throw light on a range of cultural attitudes and practices, it is a level of meaning prior to cultural meaning which interests us here, viz. the one which is accessed when a hand mark is recognized as a hand fixed in the moment of its making. This prior meaning, iconic but in a way that is special, is accessed universally and is what allows an individual stencil or print a “signature” quality. This last feature is reflected in ethnographic sources discussed below, and evidences a bringing into play of the hand image’s first order of meaning, its self-referential character, i.e., its reference to its own making. Variations in the manner this prior meaning is taken up and elaborated in the case, for example, of decorated hands in Arnhem Land, Australia (Figure 2)—or put aside, which is the case with the investment of symbolic meaning—will always be of interest to researchers. What bears on my argument for proprio-performative reception is the way cultural differences which in any instance might be determined by placement and formal properties—including size, color, decoration, digital variations, choice of right or left hand, and association with other motifs—might influence the likelihood of hand stencils and prints being read as hands, and specifically as hands belonging to a particular individual. In due course, it will be necessary to unpack this notion of the image’s particularity by reference to the further notion of stencils and prints as freeze-frames of an individual act. In the meantime, all that needs to be kept in mind is the readability of the image as a given specific hand. Before proceeding to my argument for a category of the proprio-performative, I shall deal with a range of possible ifs and buts.

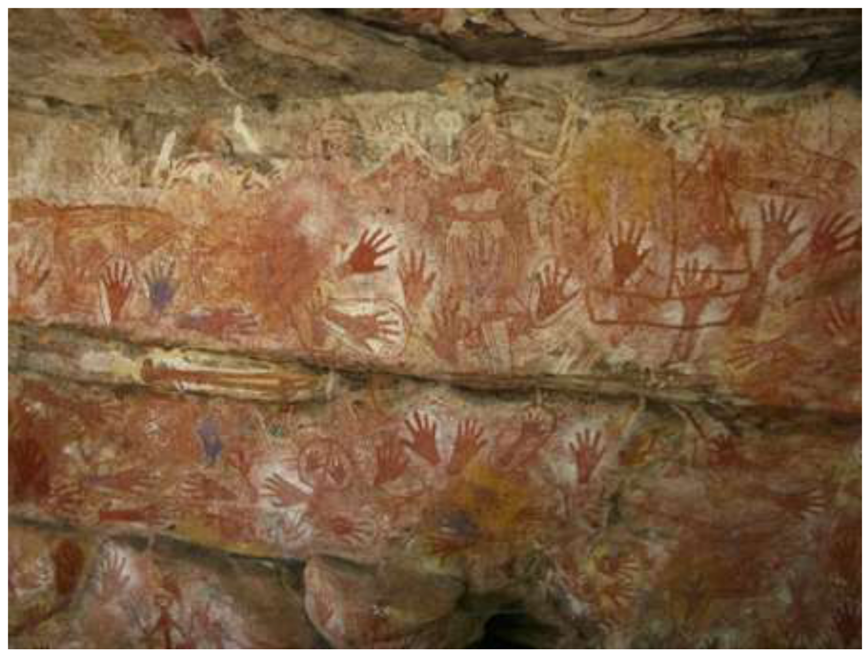

Figure 2.

Decorated hands, “Major Art” site, Mt Borradaile, Arnhem Land, Australia.

5.1. Placement

Cultural meaning may be expressed through the location, positioning and spatial distribution of images. At Carnarvon Gorge, in the central Queensland sandstone belt, Australia, and at Cueva de las Manos fronting the Pinturas River, in Santa Cruz, Argentina, spectacular use is made of affordant cliff faces to produce imposing panels of stenciled images, chiefly of hands. Carnarvon is notable for surfaces crowded with superimposed images as well as displays where there appears to be a purposeful arrangement of discrete stencils made, if not contemporaneously, then within a continuity frame of cultural connection. At Cathedral Cave, Carnarvon, for example, an arrangement of stenciled images around an opening in the rock might suggest ritual placement. An investiture of symbolic meaning does not, however, override a primary reading of the hand stencils as individualized hands. At Cueva de las Manos there are hand stencil panels made up of superimposed images, and others, which allow the stencils to stand out in isolation. Around the world, stencil or print sites utilizing more intimate spaces sometimes present themselves as composed assemblages, while at other times frequent re-inscription is evident. Sometimes the impact of an image will be accentuated through its position in a framing niche, as at Gargas where a notable stencil with shortened fingers is naturally framed ([34], p. 248, Figure 267). At Cosquer stencils displaying digital length variation are found on limestone draperies ([22], p. 71).

Universally, whether the negative and positive hands are placed as solitary register or layered palimpsest, their readability as hand marks is not affected. Indeed, in Australia, many instances have been recorded where cultural meaning is inextricably linked to the actual recognition of the maker’s identity and I shall return to this when discussing the frequently-encountered notion of hand stencils and prints as “signatures” (Figure 3). Gunn appeals to Clegg’s view that placement will depend on the existence of previous images [43], something observed at some Montana hand-print sites by Greer and Greer [44]. However, on the basis of observations made at central Australian sites, Gunn predicts bands of stencils occurring at levels suggestive of a correlation between the height of stencilers and hand size. Exceptions are noted, one of them being an infant’s hand high up on a ceiling, which would have involved lifting of the child by an adult ([43], p. 109). Mulvaney recounts Aboriginal stories from the Kimberley of children being held up while hand stencils are made ([26], p. 14). At “Baby’s Feet Cave”, New South Wales, Australia, a pair of stenciled feet is included at height within a panel of hand stencils. The question of the relationship between hand and feet images and whether or not feet should be included in the proposed proprio-performative category will be considered in due course.

Figure 3.

“Art Gallery”, Carnarvon Gorge, Queensland, Australia. Courtesy B. Witemeyer.

Greer and Greer suggest functions for handprints in the Smith River area, central Montana, that would appear to be defined by setting and association. Most often hands are found at “open bluff marker sites” which address those who approach them, conveying information about “trail routes, hunting grounds, or tribal identities”. Painted in blatant color, such sites “act as a sign or a billboard” ([44], p. 69; [37], p. 171). From his survey of hands at Franco-Cantabrian sites, Leroi-Gourhan ([45], p. 58), looking for evidence of symbolic use, concludes that, in general, there is no pattern to stencil location within caves as this differs from site to site. There are many instances of hand stencils superimposed over other images in ways that suggest an intention to connect with previous images. This will be discussed under the heading “Association with other images”.

Placement is discussed in the global literature from many points of view, ranging from assertions of symbolic arrangement to inquiry into the makers’ stature and age. Some placements may enhance the communicative potential of hand marks, like the “framed” hand at Gargas or the central Montana displays at “billboard” sites. Documented instances of obtrusive or accentuated exhibition lend support to my argument for an immediately accessible (though culturally useable) primary, i.e., non-culture-specific, meaning.

5.2. Size

The only point that needs to be made in respect to size is that, allowing for distortions resulting from affine effects occurring when the hand is angled somewhat, as well as under-spray in stencil-making and smudging in the case of prints, hand traces will approximate the sizes of the hands that made them. Predictably, stencils will be slightly larger and prints smaller ([43], p. 109). This is what gives researchers license to speculate about age, sex, and stature. An important study in this regard is Gunn [43]. This reviews both the literature of hand size research in Australia and that relating to Aboriginal stature across the country. It presents the results of examining variations in the size of stencils and prints made by a single hand when compared to actual hand-size, and—from measurements taken of stencils at central Australian sites for comparison with hand morphology data collected by Tindale between 1929 and 1935—concludes that the variability of stencil and print hand length is such as to make this comparison difficult. The length of middle fingers proved to be the most reliable predictor in the case of stencils and on this basis some separation in terms of age was achieved. Sex on the other hand could not be determined except in the case of the largest stencils (middle finger in excess of 9 cm) considered to be male because there are no recorded female hands of this size (pers. comm., 22 April 2013). Measuring hand length is recommended for prints ([43]; [46], p. 322].

Bednarik applauds Gunn’s caution, while pointing out the serious flaws in attempts by Chazine and Noury to sex hand stencils at a Borneo site by applying Manning’s index finger/ring finger ratio [47,48]. Finger length differences between males and females expressed as the “2D/4D ratio” are sourced to prenatal hormone exposure and have been used in a variety of anthropometric studies. The ratio’s possible usefulness in predicting the sexual identity and stature of the makers of rock art hand impressions was discerned by Freers [46] shortly after Manning et al. published their 1998 paper [49] on 2D/4D as a predictor of fertility. Freers’ 2001 article for American Indian Rock Art outlined his procedure in testing an anthropometric methodology incorporating 2D/4D comparisons devised to sex San Luis Rey Style hand prints at a Californian site. Results appeared to validate ethnographic accounts at the same time as they pointed the way to interpretative refinements. However, Freers sounds a note of warning: “Minor deviations in positioning can readily change the designation of 2D/4D relative length” ([46], p. 330). In response to Chazine and Noury [48] and Snow [50], Manning himself collaborated with archaeologists to take up the challenge of “who painted the images?” in relation to palaeoart and he could not be clearer about the pitfalls of attempting to discern authorship by means of the ratio alone [51]. If it is treated as a circuit-breaker to the issue of hand-size overlap between males and females, as well as between youths and females, then the 2D/4D ratio too has a problem of male-female overlap. Other problems identified by Manning were the difficulty in achieving accurate measurements of stenciled hands and controlling for ethnic differences in the process of establishing a normal range. Manning was not confident that the “sexing software” (Kalimain©) developed by Noury could avoid compounding measurement problems. The Manning article is invaluable, not only for its specific critique, but for confronting general issues relating to hand sites, such as possible sources of dimension distortion in stenciled hands, artwork representing different time frames at the same site, or ambiguity relating to right hand/left hand identifications—right hands being more indicative of ratio difference.

The use of 2D/4D is ongoing, despite the efforts of Brůžek et al. [52], in the specific context of critiquing Chazine and Noury [48] and Snow [50], to dissuade people from trying. They argue that, without knowledge of the population in question, hope of determining sex is “illusory” [52]. At this point in time, Freers continues to pursue his project of bringing together ethnography and anthropometric data obtained in part by 2D/4D for a determination of author-profiles: both stature and sex [53]. Using an updated version of their software and continuing to appeal to Manning’s ratio, Chazine and Noury are engaged in producing further predictions for Borneo sites [54]. Robins and Nowell have taken up Manning’s suggestion of replication studies to test the useability of 2D/4D. A sample of 400 children using blow pipes has produced positive results in terms of accuracy when the ratio measured from soft tissue is compared with that of stencils. However, the challenge of addressing the issue raised by Brůžek et al. [52,55] remains.

Large or small (Bednarik claims juvenile authorship for Franco-Cantabrian cave art [47]), robust or gracile (Neanderthal authorship is hypothesized at El Castillo [23]), male or female, the issue for the present argument is, however, simply the readability of images as hands. As indicated above, and crucially for the proprio-performative thesis, hands are read as belonging to someone—whether or not that someone can be identified. This is the assumption behind all efforts to judge characteristics through stencil and print measurement.

5.3. Color

Use of color has been around for a very long time, for body decoration or other purposes. On current sub-Saharan evidence, Beaumont and Bednarik tentatively postulate pigment use arising as much as a million years ago [56]. Africa certainly has the most abundant and oldest safe evidence of pigment use. At Wonderwerk Cave, central South Africa, a richly-productive site with evidence of occupation from 800,000 to 900,000 years ago, pigment material of possible ~1.1 Ma age has been found ([57], p. 44). Sites in Kenya and Zambia support African antiquity ([58], p. 96), and in this issue of Arts, Bednarik underlines the importance of evidence of haematite traces on the significant middle Acheulian Tan-Tan figure from Morocco (see also [58], p. 96; [59]). A find of 100,000 year-old shells used in the mixing of ochre at Blombos cave, South Africa [60], evidences early human art activity as well as cultural continuity with the present. Mulvaney ([26], pp. 15–17) gives a detailed account of recently-recorded ochre-gathering practices carried on in the Kimberley, Australia, including the use of boab nut containers for pigment preparation. For the elaborate procedures of Arnhem Land, Australia, see the “Pigments, brushes and techniques” section in Chaloupka ([61], pp. 83–86). The relevant question here is: what does color bring to hand stencils and prints? Bahn and Vertut ([36], p. 169) observe that the palette of European Palaeolithic art “was limited and usually involved a straight choice between red and black”. Petru adds white, while allowing for the disappearance of unstable color (Bednarik’s “taphonomic logic”). She remarks pertinently: “If elaborated speech emerged with modern humans, then improved communication through color is probably part of modern human behavior” ([62], p. 204).

At the polychrome hand stencil site, Cueva de las Manos, color is amazingly varied in its white, black, yellow, red, violet, and occasional green effects (for pigment analysis see Wainwright et al. [63]), and exuberantly displayed in what in some instances could be non-accidental placements. For example, situated above crowded panels, as if to attract special attention, is a single hand stencil in green (Figure 4). Gradin et al. ([64], pp. 18–19) speculate that specific colors might have been used to identify membership of a tribal group. This is the case for color use in Arnhem Land where the privileging of particular colors relates to “group expression” as well as individual seniority ([61], p. 86).

Figure 4.

Cueva de las Manos, Santa Cruz, Argentina. (For green stencil see top centre.)

Leroi-Gourhan hypothesizes symbolic alternating red and black color use for stencils at Gargas [65]. Some sites, like Carnarvon Gorge, feature only one pigment, in this case mostly red applied to greyish white sandstone walls. Tresize notes a replacement of red hand stencils by white, suggesting highly speculatively a “taboo”, in Quinkan country, Cape York, Australia, occurring “when people were able to return to country abandoned to searing drought for many millennia” ([42], p. 199). Color is, of course, a feature of positive prints as much as stencils, as the 100 Hands site in Utah illustrates, inviting similar conjecture about the reasons for its use (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Positive prints, 100 Hands site, Utah, USA.

Does color, then, interfere with what I have termed primary hand readability? The answer is clearly “no”. A hand mark records a specific hand regardless of the color of the pigment used, and at Cueva de las Manos, despite variety and profusion in hand presentation, there are many indications that, over and above apparent compositional arrangements, the single mark was important in its own right. Even where stencils are placed on surfaces already painted—“thus leaving a beautiful polychrome effect” ([39], p. 27)—there will be those that still stand out in sharp relief against the palimpsest background with its elusive specters of past stencil applications (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cueva de las Manos, Santa Cruz, Argentina.

An issue arises for the present argument when the so-called “decorated hands” of western Arnhem Land are considered. At “Major Art” shelter at Mt Borradaile, Australia—also notable for an abundance of superimposed hand stencils in striking color—original negative images have been transformed by the addition of intricate designs. The idea that color matters in this process is reinforced by the use of “Reckitt’s Bag Blue” (i.e., washing blue obtained from missionaries) in place of ochre for some hands, thus extending color range. Chaloupka ([61], p. 214) describes similarly embellished hands found at other locations in the region, claiming that the decorative tradition stems from representations of gloves observed during the contact period. Other representational options, however, are not ruled out, and another explanation for such “glove-like” images has been offered by Taçon who draws on information from Arnhem Land supplied by Cannon Hill’s Bill Neidjie on the subject of repainting extant stencils of the dead: “some stencils have been painted with clan designs and x-ray features, such as finger bones, to produce striking images by which to honor and remember particular individuals” ([66], p. 138). The practice in southern Arnhem Land is to obliterate pictures, including stencils, made by the dead by over-painting them with red ochre before replacing them with fresh images. If this does not happen, then “the original picture must be left to wear out” ([67], pp. 245–246). We can conclude from this that in all instances the likely motive is to remove traces of individual identity. However, in the case of such “decorated hands” we do not need ethnography to tell us this, as it is a matter of perception. Although hand size will continue to give some indication of owner identity, attention to the potently-evocative facsimile of the originator’s hand recedes. It is for this reason that this sort of image is, as I intend to argue, to be excluded from the proprio-performative category. Once decorated, and depending of course on the nature and extent of the decoration, the hand image no longer addresses the viewer in the same way. It is no longer a trace, but a picture of a hand (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

“Decorated hands”, Mt Borradaile, Arnhem Land, Australia.

5.4. Decoration

With decoration, there is a point at which the very particular trace of an individual hand disappears. In the Australian case given above, the stencil is now altered and in such a way that it has not become, by virtue of the infill, the equivalent of a print. A print is as readable as an animal track encountered in real life. With the cues for individual ownership weakened or erased, the adorned hand is aptly described as “glove-like”. Embellishment functions as a mask, or, to use a culturally-loaded word with different color connotations, a “shroud”. Its function is to cover over. In a word, the stencil looks less like a stencil and more like a picture. However, it is essential for a stencil that it not be a picture, even as it retains that iconic quality.

Another version of the embellished hand is to be found in the enhancing of a positive print. This is the “patterned hand” encountered in Australia and elsewhere (Figure 8). In this case, the patterning is not so much an obscuring of the original hand image, as a visual distraction. Prints “with an unusual form of internal decoration” at Levi Range, central Australia, were examined by Gunn [68]. Various hypotheses were put up and actually tested, with the result that similar images to those at the site were replicated by “scraping” onto the “pigmented hand”. The Levi Range positives are remarkably similar to those of Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, recorded by Grant. These are said to be achieved by “drawing whorls, zigzags, and straight lines on the wet palm with a stick” prior to printing ([69], p. 158, Figure 4.7; p. 169, Figure 4.17). Manhire describes “decorated” hand images, “somewhere between a print and a painting”, from the south-western Cape, South Africa, made “by scraping off a pattern, usually nested curves or “U” shapes, on the already paint smeared palm or hand” ([70], p. 98, p. 99; see also van Ryssen [71]). Malotki and Weaver distinguish between “stylized” (i.e., nested U’s), lined or “striated”, and “patterned” positives (bearing scrolls, checks and zigzags)—and give examples of these from the American southwest ([72], pp. 54–55). “Stylized” for Greer and Greer is something different again, involving distortions of shape. They also remark that, at one Montana site on the Musselshell River (Reighard), after application of paint to the wall, “many had the palms (and sometimes the fingers) pecked out by a small sharp object” ([44], p. 63, p. 67). Bahn provides an illustration of the “nested arc motif” on prints at Seminole Canyon, Texas ([73], p. 112). Unusual hand images from Esselen Big Sur country, California, have been documented by Breschini and Haversat. While these look like patterned prints, however, careful examination suggests they have been “painted using a brush” ([74], p. 142).

Figure 8.

“Patterned hands”, central Australia. Courtesy R.G. (“ben”) Gunn.

What is important is that—as with decorated negatives—canonical form, i.e., the recognizable shape of the human hand, is not overridden: crafted positives still remain recognizable as images of human hands—despite any fuzziness due to smudging or dribbled ochre. However, the effect of the patterning is to suppress the prints’ readability as individual hands in favour of attention-grabbing display. This sets patterned positives apart as a collection of distinctive images referring to something over and above both their individuality and their general readability as hands. In fact they appear to lend themselves to group (clan/moiety) identification. Clan identification has also been suggested for decoration resembling body-painting within stencil outlines found at some Borneo sites [54]. In this case the stencils’ personal forms are not obscured. Likewise, suppression of identity cues need not come into play when the vacant area in the centre of a print is simply filled in “to make it more homogenous and complete” ([44], p. 62). To sum up: the masking of an individualized act which comes into play in the case of decorated negatives and the element of visual distraction with patterned positives will affect the way such images are viewed when considered as candidates for inclusion in the proprio-performative category. The full significance of the notion of stencils and prints as the record of an action will emerge in due course.

5.5. Digital Variations

Breuil on Gargas hand stencils: “Many seem to be mutilated as if phalanges had been cut off” ([34], p. 256). Because of its centrality in the discourse, we are obliged to begin with the theory of deformed (either “mutilated” or diseased) hands—dated as it might be. Reports of finger amputations in Australia were made in the colonial period (e.g., Tench in 1789, [75], p. 49; Collins in 1798, [76], p. 458) and by later ethnographers like Roth ([77], p. 184) and Basedow ([41], pp. 253–254)—in 1897 and 1925, repectively—and may have contributed to the mutilation thesis. Finger amputations were in fact referred to as “mutilations” by some early anthropologists ([78], p. 746). Grant ([69], p. 168) accepts it unquestioningly, while Bahn ([73], p. 113) simply states pro and contra viewpoints. In 1967 Leroi-Gourhan complained that the mutilation hypothesis, “acceptée par la majorité des préhistoriens... est passée dans la tradition scientifique, sans verification approfondie” (“accepted by most prehistorians and... passed into scientific tradition without being subjected to strict verification”). He put up arguments against both mutilation and the idea of pathological deformation ([65], p. 108; [79], p. 20). Opinion did change, however, and since lengthy discussion of the limited practice of ritual amputation in Australia ([80]; [81], p. 14; [82], pp. 3–4), replication experiments (Groenen [83], pp. 101–111; see also Walsh [80]), and the instancing of transposable signals from gestural languages of the Kalahari and Australia ([84], p. 215; [80]), most commentators have come to accept that, for the most part, digital variations have been accomplished by bending fingers and were used to codify symbolic meaning [65]. Reviewing what began as a heated, largely French debate, Clottes and Courtin ([22], pp. 67–69) put forward a strong argument against the idea of mutilated or deformed fingers in favour of Leroi-Gourhan’s “transposition directe des symbols gestuelles du chasseur” ([65], p. 121). They illustrate just how speculative the theory always was by pointing to the fact that “no skeleton known from the upper Palaeolithic displays hands with incomplete, amputated, mutilated, or deformed phalanges” ([22], p. 67). We have witnessed the same turnaround in Australia with Morwood asserting confidently that “partially missing or distorted fingers are clear manipulations of hand position, as used in historic times for sign-talk during hunting or periods of enforced silence” ([85], pp. 166–167).

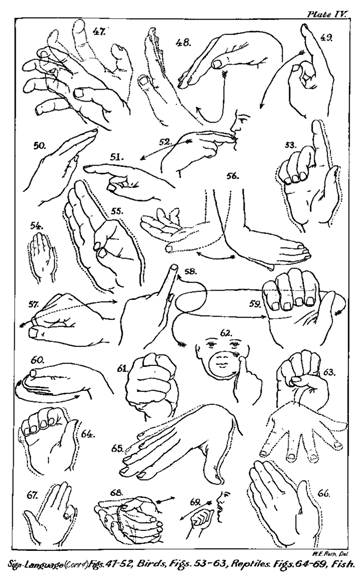

It has been pointed out that it is difficult to match static stencil images with the dynamic signs (Figure 9) which occur in gestural language [82,86].

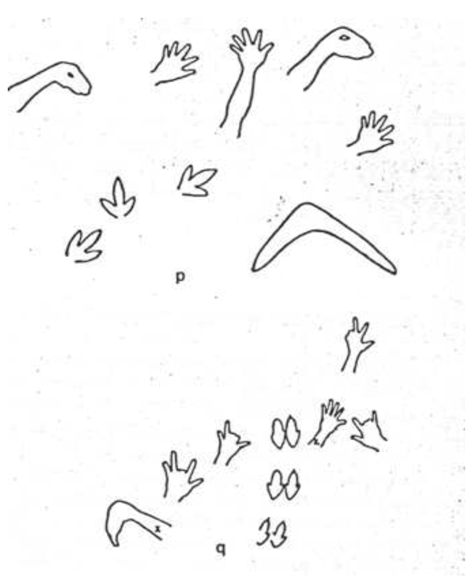

Figure 9.

Samples of gestural signs denoting birds, reptiles and fish, as illustrated by W. E. Roth, Plate IV, Ethnological Studies among the North-West-Central Queensland Aborigines, 1897.

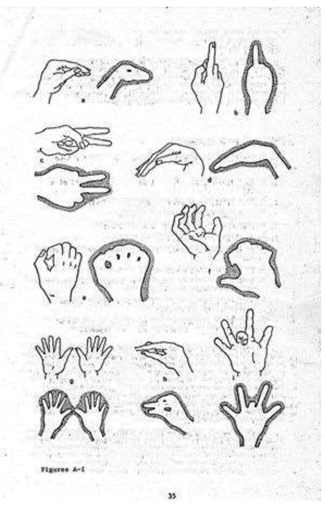

Nevertheless this is what Walsh [80] managed to do with some degree of convincingness. One illustration from central Queensland of what we should be now willing to call “transposed sign language” will suffice to show the kind of images for which Walsh was seeking to find gestural equivalents (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Candidate stencils for transposed gestural signs, Central Queensland Sandstone Belt, Australia. Courtesy C. Sefton.

I have not been able to match images from this panel displaying digital variation with the Roth illustrations ([77], pp. 71–90; Plates II-X) Walsh draws on for comparison, except perhaps for his “b”, visible as a hand with one finger extended upwards (Figure 11), which Walsh himself appears to think matches a Roth figure (his Figure 143. Spear: Wommera-spear [77]). Wright [82] extended Walsh’s exercise by making a comparison of stencil variants encountered in western central Queensland with signs denoting faunal totems recorded in six source texts, including Roth (Figure 9). His conclusion was that such signs feasibly account for around 40% of his sample and, conversely, that mutilation accounts for less than 9%. From such investigations we can allow that there exist a number of images which are quite distinctive in shape and might qualify as signs. However, their meaning as signs cannot be verified without cultural knowledge. We can only guess, like Walsh using available ethnography from an area 600 km distant, and Wright from even further afield. We need not conclude that all meaning will elude us, that we cannot “‘read’ rock art” [87], for we can recognize stencils as replicas of hands even when they refer to gestural signs, and this is what is important for my argument. Hand stencils are universally understood as hands. As traces of hand actions they are as recognizable as animal tracks, even when fingers are bent. With digital manoeuvring we see a hand with contorted fingers and additionally see the canonical form of e.g., a bird’s head. And if we are proficient in a gestural language we will read and decipher any supererogatory meaning invested in a particular configuration of bent fingers, canonically suggestive (like the bird’s head) or otherwise.

Figure 11.

G.L. Walsh, “Mutilated Hands or Signal Stencils?”. Australian Archaeology 1979, 9, p. 35. (Example “b” is seen top right.)

To return to the example of the single-fingered stencil (Figure 10 and Figure 11): there will be exceptions to hand recognizability. Excised from its context, Walsh’s Example “b” might not be recognized as a hand without ethnographic input, but this particular image presents an extreme case of occluded elements which could cause it to be confused with other shapes. That our perception can at times be bamboozled does not alter the fact that we rely on it to negotiate our way in the world. Habitually we recognize hands in numerous postures—with bent or folded fingers—and it is not more difficult to detect their forms in the stencils than it is to recognize hands in real life. Therefore, with the proviso that we can suppress our awareness of the canonical form of hands, that is, their recognizability as hands, when switching our attention to symbolic meaning—or when attending to a canonical alternative of the bird-head variety—hand stencils retain their own iconic status, retrievable at any moment.

Demonstrably, in the absence of other markers, their function as communication from an individualized source depends on their recognizability as hands. At the same time, with these and other examples it is a case of “a particular someone saying this”. Regardless of digital variation and its possible symbolic import, individual traits (hand size etc.) are apparent, which means that a reading of individual identity, even if unspecified, is part of the meaning. I suggest that while ethnography cited below may allow us to specify identity, it is the fact of the stencil’s individuality, rather than actual personal identification (presupposing cultural knowledge) which is of interest to the present argument.

5.6. Choice of Right or Left Hand

This record of the making of a hand stencil by anthropologist Daisy Bates was made between 1904 and 1912, although it had to wait until 1985 for publication by the National Library of Australia:

In drawing the white hand, charcoal or red ochre is softened or moistened in the mouth and the clean bare hand pressed against the surface of some white or light colored rock, with the fingers of the hand well stretched out. The charcoal or ochre mixture is then blown or squirted against the back of the hand and well between the fingers and thumb and when the hand is withdrawn a perfect impression is left on the rock, enhanced by the dark surrounding of red or black as the case may be.([88], p. 272, italics mine)

Bates distinguishes between colored images in black or red, and white images. All are called “impressions”, but it is clear that by “drawn” white hands she means stencils. There has been an issue in rock art studies as to whether the palm or back of the hand is used to make stencils ([89], pp. 99–100; [33], p. 50; [22], p. 70; [44], p. 61). Like Bates as quoted above, Basedow also specifies palm-to-surface in stenciling by spraying from the mouth ([90], p. 238). What both have to say about this matter is given support by a remark by Flood to the effect that contemporary Aborigines place the palm against the surface ([91], p. 103).

When rock art researchers record a predominance of left hands (which is almost always the case), they are assuming on an intuitive basis what Bates, Basedow and Flood claim from observation, viz. palm-to-surface application. Layton ([25], p. 75) inadvertently supplies pictorial evidence to support this view with his photograph of the maker of a stencil identifying where she put her hand on the rock.

Assuming the jury still to be out on the issue of palm-to-surface, Clottes and Courtin ([22], pp. 69–70) sensibly choose to call a left hand one whose the thumb turns to the right. Adopting this as a convention allows us to bypass the issue of palms or backs of hands. Clottes and Courtin go further than this, however, by suggesting that at Cosquer and Gargas the “form of the images” rules out the dorsal possibility. By closely examining an awkwardly-placed hand image at Gargas, Barrière and Sueres set out to dispose of the notion of the right or left hand applied dorsally to produce the effect of its opposite. Clearly the orientation of a depicted wrist or arm will help in making a judgment in a specific instance. Where the sceptically-proposed “inversion acrobatique” of Barrière and Sueres would have to be assumed for back-of-the-hand execution, we are surely justified in ruling it out ([33], p. 50). Nevertheless, we can never be entirely certain. For argument’s sake this stencil from Mt Borradaile (Figure 12), unusual in having the thumbs turned outwards (cf. the more commonly found paired hands with thumbs turned inwards), might have been achieved by putting the right hand to the wall to produce the stencil on the left-hand side, then flipping it on its back for the one on the right. Alternatively, arms might have been crossed in the making of this atypical image. Judging by the position of the wrists this seems more likely.

Figure 12.

Paired stencils with thumbs outwards, Mt Borradaile, Australia.

I have raised this issue merely to put it aside as irrelevant to my argument, for the simple reason that my focus is what we perceive when confronted by such an image. Whether or not the image is produced by the back of the hand or palm facing forward, the canonical form of a hand is produced and the image is thus recognizable as a hand. To state the matter more precisely: because the canonical form resulting from a left hand placed palm-to-surface and a right hand in dorsal position is exactly the same, and in being exactly the same can be read either as a left hand with back to viewer or a right hand viewed frontally, the question of whether an image was made with a left or a right hand is immaterial. (The exercise can be thought through beginning with the right hand palm-to-surface.) To say this is to argue that with stenciled hands we are encountering an effect where an ambiguity is routinely present and a perceptual switch is a routine option. For a discussion of the operation of reversal mechanisms see Dobrez and Dobrez [92] on the subject of Kihlstrom’s Arizona Whale-Kangaroo (a version of the celebrated Rabbit-Duck), where the perceptual response to an ambiguity is analogous to the hands case—although the case of hands does not involve a lateral switch.

Consider for a moment my relationship with my own shadow, viz. what I see when I look at my own shadow. When I observe the silhouette of my body cast in front of me in a certain posture—for argument’s sake, with arms raised and palms facing away from me—I can match the silhouette with the position of my own body and observe how my thumbs are turned towards it. When I do this matching exercise I am seeing myself from the back, as someone would see me if following behind. On the other hand, we all know the colloquial expression “afraid of her own shadow”. This idea involves more than the metaphor which has been extensively used in literature to convey the notion of psychologically double or split personalities (e.g., Dr Jeckyll and Mr Hyde), for fear of one’s shadow is an actual perceptual possibility having cognitive ramifications. If I were to approach a wall, with the illumination still behind me, my own image would loom up before me and, in this moment, I would face myself as other. Regardless of the effect it might have on my amygdala, what is important is that now a reversed image of myself appearing to me as an other confronts me. In other words a perceptual switch causes me to see my left hand as a right one facing me, and my right hand as a left one facing me. This could be labelled the “mirror effect”, but shadow is a much better analogy, since with a mirror there is never the possibility of a back view, the optics being different in each case. This said, once the shadow of my hand or, by analogy, the stencil trace of my hand on the rock, is viewed as confronting me, I do then experience the mirror effect, now meeting myself as other. I shall return to the notion of a “perceptual switch” when elaborating my argument for the proprio-performative.

5.7. Association with Other Motifs

One outcome of Wright’s inquiry into the relationship between hand stencils and sign language was the raising of an important question about the significance of associated images. Davis, commenting on Wright [82], pointed out that “associations are a central aspect of hand imprinting in Franco-Cantabrian parietal art” ([86], p. 17). Responding to this, Wright agreed that “an interpretation derived from a motif in isolation from other motifs with which it is associated, may lead to a misunderstanding of both the context and the symbolism within the artistic system” ([82], p. 17). With regard to central Queensland sites, Walsh speaks of “composite panels comprising ‘signal’ stencils, boomerang stencils and occasional sets of stenciled animal feet”, drawing the conclusion that they are “so strikingly obvious in their composition and semi-isolated positioning” they must carry “specific” meaning ([80], p. 39). In other words, we are to see the association as extending the range of the sign system (Figure 13).

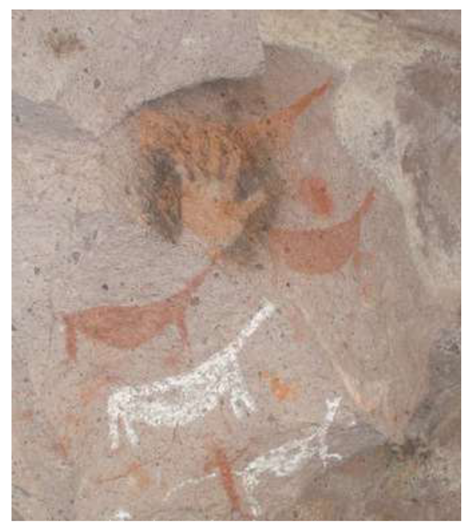

Figure 13.

Walsh’s “composite panel” examples from central Queensland, Australia.

Carnarvon stencil corpora include transposed sign language hands comprising “stock” hands, hands with forearms (among such images there are conjoined forearms with hands at either end), hands with bent fingers, feet, and other objects, generally of intimate use, viz. of the “bodily auxiliary” class theorized by cognitive psychologists, Tsakiris et al. ([93], p. 657): weapons, tools, utensils, pendants, and, in a departure from the method producing iconic trace, nets made by building up the image from triangles formed by spraying ochre between two fingers. However, a layering of stencils mostly forbids the disentangling of possible associations.

At Pinturas River sites, Patagonia, stencils include choique (Rhea Americana) feet, guanaco hooves and human feet ([64], p. 19; [39], p. 29), in panels where there are also hunting scenes, geometrics, static animals in profile and frontal anthropomorphs. Analysis of superimpositions, considered in relation to archaeological evidence and pigment analysis [63,94], has enabled construction of a sequence stretching over more than 8 millennia. The occurrence of stencils placed over animal figures might lead us to speculate that these are sites of increase. Illustrating their point with an image of hand stencil superimposition on a guanaco, Onetto and Podestá speak plausibly of a “revitalizing” of panels over a lengthy period ([94], pp. 73–74). Lest we always arrive at this conclusion about motives for superimposition, Mulvaney provides an illustration from the Kimberley, Australia, of the way hand prints placed on human figures may have been used at a site for negative effect, viz. defacement: in one instance positives, in the form of both hands and forearms, are placed over a figure “on a single axis (elbow joint to elbow joint)” ([26], p. 17).

Associations of hand stencils with an imposing human figure and other objects, viz. the drawn profile outline of a kangaroo, no longer visible, “two tomahawks, a waddy, and three boomerangs”, at a site thought to be a ceremonial (bora) ground at Milbrodale, New South Wales (Figure 14), were recorded by Mathews in the 1890s ([95], p. 90–91; [96]). Pigment analysis is needed to establish a relationship between the giant “Baiame” (Sky Hero) and the stencils, one of which is clearly superimposed on the figure. Indeed, it is quite possible that at this site we are looking at two distinct episodes. This would not, however, preclude intended association. Moore observes that the stencils are “positioned very deliberately” and—unlike many “jumbled and superimposed stencils” in the region—appear “to tell a definite story” ([97], p. 320). With some echoes of Howitt ([78], p.388), Elkin [98] or Eliade [99] on the subject of medicine-men who can “fly”, he proposes a rather extravagant and unlikely reading of the association based on the acceptance of a dynamic and naturalistic relationship between images. Such a relationship is not generally claimed for composite stencils:

The white stripes, which have puzzled most viewers, seem to be dangling from the arms like wing feathers. If my assumption is correct, then the boomerangs are obviously being thrown at this awe-inspiring figure by the stencilled hands.([97], p. 321)

While most of the Milbrodale imagery described by Mathews is still apparent, and therefore open to future clarification, accelerated deterioration through dust pollution is deplorably imminent, as AGL Energy Limited is planning a core hole, access tracks, and infrastructure for coal seam gas exploration a mere 1.4 km to the north of the shelter [100].

Figure 14.

Milbrodale Baiame with associated stencils including hands, central Hunter Valley, New South Wales, Australia.

There are many examples from around the world of associations involving varied superimposition (Figure 15 and Figure 16). Describing the extraordinarily layered “lady of the Deighton” panel in Quinkan country, Cape York, Australia, Tresize notes that “three white hand stencils had been placed on or near her body” ([42], p. 110). These, along with other painted images and pecked grooves, suggest many visits over time, some of them purposefully registered. Keyser and Klassen remark on a notable X-ray grizzly bear with surrounding and superimposed handprints at Whitetail Bear site, Montana ([37], p. 159; see also [44], pp. 65–66, p. 162)—an association which is repeated elsewhere at Foothills Abstract sites—and propose initiation rituals taking place at a bear site with adjacent prints on the lower Musselshell River ([37], p. 173). Again from Australia, Tresize mentions encountering “deliberately placed” stencils at significant Cape York sites—one of them purportedly displaying the hand stencils of seven guerrilla warriors following the line of a repainted snake in a sorcery composition aimed at a black police trooper ([101], p. 16). Superimpositions can be layered in the opposite way to these examples of stencil over figure, i.e., figure over stencils, and may indicate random association. On the other hand Clottes and Courtin note Cosquer hand stencils (placed on a difficult-to-access surface) over which was engraved a “wounded” horse some thousands of years later ([22], p. 73). Since the stencils in question qualify as “gestural language” possibles, and the motif “intersection” might well have been deliberate, the hypothesis must be entertained that such symbols were readable over a long period of time.

Figure 15.

Superimposed hand, Charcamata, Santa Cruz, Argentina.

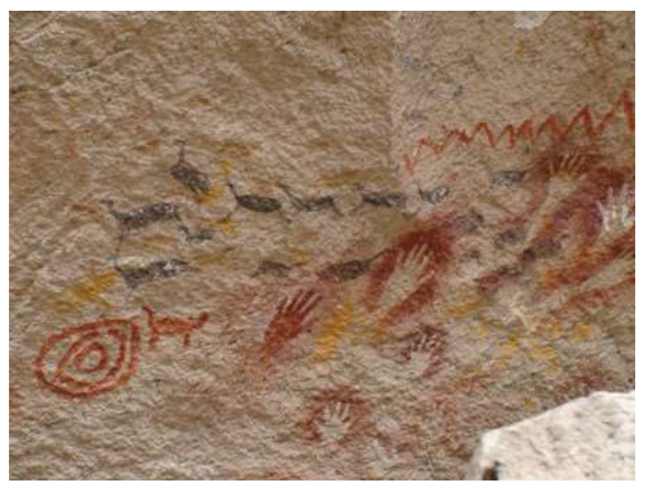

Figure 16.

Associated images, Cueva de las Manos, Santa Cruz, Argentina.

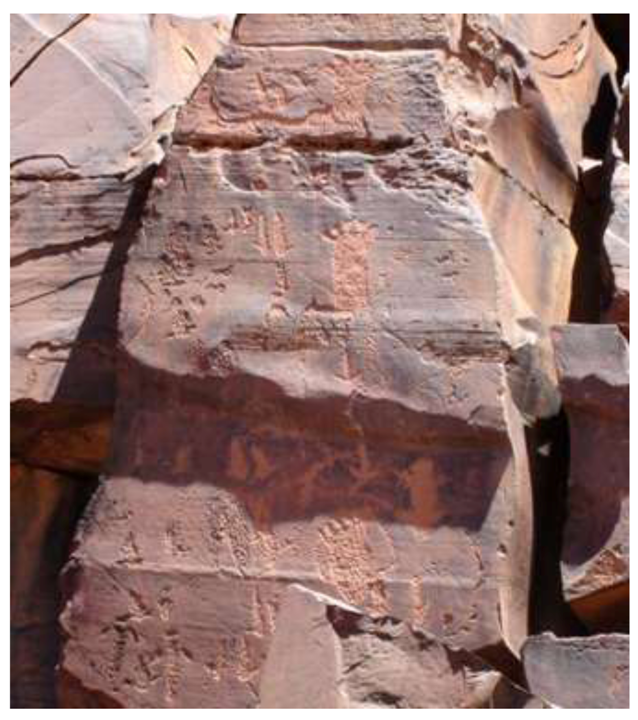

Importantly, the way stencils are associated with one another can be an indicator of probable symbolic meaning. From Australia, this Mt Borradaile ceiling panel (Figure 17) suggests more than an exercise in patterning for its own sake, since both complete and incomplete stencils are present in a line-up which, if read in the direction the hands are pointing, culminates in a fanning out of stencils in varied array. On the grounds of the repetition of the same “clenched or missing forefinger”, Roberts and Parker ([27], p. 31) postulate a single stenciler, which could well be the case, as the dimensions of the complete hands appear to match those of the more frequent incompletes. Bouissac argues that if single individual authorship could be postulated for a set of hand images the notion of a sign system at work “would be considerably reinforced” ([102], p. 93).

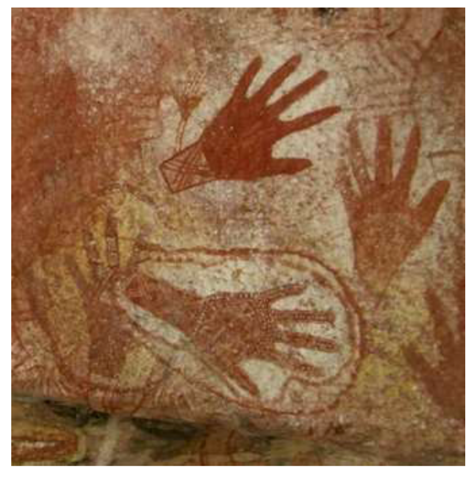

Figure 17.

Ceiling panel, Mt Borradaile, Arnhem Land, Australia.

It is interesting to find a record by Keyser and Klassen of the occurrence of “stylized” hands (sometimes with digital oddities) as well as feet, described as “simulated prints rather than the outline of a real handprint or footprint”, in the Plains Indian Pecked Abstract Tradition, where they occur in numbers in association with geometric or maze motifs ([37], pp. 142–143). In view of Walsh’s “composites”, might this suggest a coded symbolic meaning? At times associated Foothills Abstract tradition “hands” with unusual features are interpreted as shamanic “shape-shifters” as in the case of a painted image equally suggestive of a human hand or bear paw ([37], pp. 169–170). As I have already remarked in my discussion of decorated and patterned hands, the more remote a hand image is from direct register of an action, the less it bears on my present concerns. As soon as imagery becomes “simulated”, i.e., derivatively mimetic or, alternatively, time-consuming, as is the case with pecked images, it ceases to manifest the immediate trace-quality of prints and stencils whose forms, like animal tracks, retain pictorial memory of an act. This, as we shall see, will disqualify images which in effect “quote” stencil and print impressions from my proposed category.

6. The Case for a Special Category

Where, then, does this clearing of the ground get us in terms of a case for a special category for hand stencils and prints? To answer this question we need to look more closely at what a hand stencil is, i.e., how it is to be characterized for purposes of categorization. So far it is clear that stencils and prints express something individual, both as a record of a particular act—and this is a point yet to be fully elaborated—and as testimony to a particular human identity. Though in practice these are not separable, we can distinguish them, the one referring to an individual event, the other to an individual identity specifiable via cultural information. Once the notion of a particular “act” has been elaborated, we can refer to these as the stencil’s or print’s “act-identity” and its “author-identity”—always bearing in mind that the two work in tandem. It is also important to understand that the present argument is more concerned with the first, though it cannot avoid reference to the second. What about issues of “decorated”, “patterned” and “gestural language” hands canvassed above? We have seen how decorated stencils of the Arnhem Land variety, while retaining the canonical form of hands, seek to obliterate the distinctive features which enable them to be read as belonging to an author. Following decoration, such hands require a coming into play of cultural memory for recognition of ownership: I will remember that I decorated the stencil made by my relative who has died, but his autograph no longer remains. Patterned prints are like decorated stencils to the extent that they distract from individual authorship, i.e., they are a departure from straightforward facsimile, while their canonical form remains that of hands. So-called “mutilated hands”, or transposed gestural language stencils, are readable both as human hands and as exhibiting individuality: witness the Mt Borradaile example where Roberts and Parker ([27], p. 31) discerned a single author in a line-up of such stencils—a proposition measurement might help verify. We also found that cultural variation in such attributes as placement, size and pigment use will not affect hand readability, either at the level of canonical form or of individuality. Again, it helps to think of this individuality as both the record of an event, and authorship, the record of the person responsible for it. Any picture is referable back to the activity of its making and to a particular maker. However, stencils and prints, as (inevitably) assumed from the start of this article, are not pictures of hands. Their individual quality is of a special kind. This is what now needs to be gradually investigated.

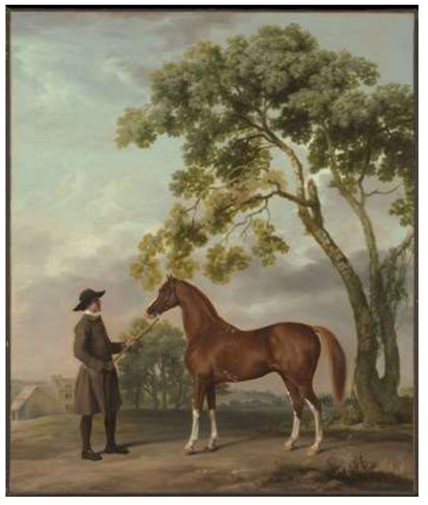

If we consider canonical form alone, there is no difference between a hand mark and any other readable image: I read a hand stencil as a hand, and a bison image as a bison, a kangaroo as a kangaroo, a bear as a bear. On the further question of particular identification: clearly, I read Stubbs’ painting Lord Grosvenor’s Arabian Stallion with a Groom, c. 1765 as a picture of both a horse and a particular horse (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

George Stubbs, British (1724–1806). Lord Grosvenor’s Arabian Stallion with a Groom, c. 1765. Oil on canvas. 99.3 × 83.5 cm. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth.

However, reading a hand stencil or print as that of a particular person is not the same thing as identifying a particular Stubbs horse. The particularity of the former has a direct quality, which makes it quite different from the latter. The difference is certainly tied to what rock art researchers are in the habit of describing as the “signature” quality of a stencil or print, viz. those features like finger width and length which cue individual identity. At the same time, the idea of a “signature” may be understood in various ways, not all of them helpful. I shall argue that the hand mark as belonging to a particular individual does indeed qualify it as belonging to a special category of images, but that this needs to be understood in a way that goes considerably beyond the usual idea of an autograph. Let us begin, though, by examining received versions of the proposition that hand stencils and prints amount to “signatures”.

6.1. “Signatures”

The term “signature” is frequently encountered in rock art studies of hand marks, not necessarily with backup from ethnography or with theoretical questioning. When ethnography is taken into account, particular sources are not necessarily cited. Grant makes the general comment that “modern Pueblo Indians consider the handprint as a kind of signature”, supporting his observation with a contemporary example (a plasterer marking his finished work) and an appeal to discoveries of Mayan handprints on pre-Columbian masonry ([69], p. 168). Obviously, it is in those places where there has been a continuation of the practice of hand-marking that ethnographic insights can be sought. Australia, for example, is a privileged zone of maintained stenciling activity. Roberts and Parker [27], who appeal to the notion of signature while writing about rock art at Mt Borradaile in Arnhem Land, are probably relying for their interpretation of the purpose of hand prints and stencils on Forge [103] who in turn cites Taçon—whose own source is traditional owner of Deaf Adder Gorge sites in Arnhem Land, Bill Neidjie ([66], pp. 137–138). Or, alternatively, their source is Bill Neidjie through Mt Borradaile’s campsite manager Max Davidson ([27], p. 4). Whatever the case, they are confident that stencils and prints are “signatures; the brand of a particular individual who may have had special associations with the particular area” ([27], p. 30). It is “signature” understood in this sense that I have termed “author-identity”.

Often the authority for assertions of individual inscription will be Herbert Basedow’s report in The Australian Aboriginal (1925) of the stencils, or “hand shadows”, of the Worora peoples of the Kimberley. Basedow’s claim was that it is “beyond dispute” that Aboriginal people “possess the faculty of being able to recognize the hand-marks of their relatives and tribesmen, even though they may not have been present when they were made” ([41], pp. 321–322). The naming of stencils as “shadows” (“wongili”), so evocative of individual ownership, is also recorded by Peterson ([104], p. 16) writing about the Murngin of north-east Arnhem Land. In the context of delineating an Arnhem Land practice, subsequently backed up by ethnography from the region, Basedow (1935) once again brought into focus the hand stencil as a “record of individuality”:

It is the belief of a native of the north-west that the spirits of departed tribes-people desire to be revered by those nearest to them; and for that reason they keep a tally of their visits made to the sepulchral caves. By placing the imprint of his hand upon the wall, the native leaves evidence of his call... Each hand-mark can be recognized, not only by the person who made it but by every member of the tribe, with wonderful precision and reliability.

Basedow further remarked that this capacity for precise recognition should not surprise us in connection with people expert in tracking, pointing out that, in addition to hands, stencils are sometimes made of “the visitor’s feet” ([90], pp. 238–239): in other words, feet too can function as signature. Foot-stenciling, although rarely occurring in the rock art record, is not unique to Australia: it has, for example, been recorded in the Sahara at Wadi Sora ([87], p. 29) and in the last to be humanly occupied territory of Patagonia ([39], p. 29). Peterson lists both hand and foot stencils among the ways the Murngin men of north-east Arnhem Land leave “evidence of their presence in a particular place” ([104], p. 16). In his 1925 book Basedow adds stencils of “private belongings” (emphasis mine) to foot stencils, raising the possibility that a sense of personal inscription can also extend to objects which might be regarded as extensions of the self ([41], pp. 321–322). The previously mentioned stenciling of baby’s feet might be said to satisfy this requirement, on the grounds of intimate relationship: an infant is not independent of its parent (Figure 19). Flood notes a similar image of baby’s feet from Cape York, Australia ([105], p. 412).

Figure 19.

Baby’s feet stencils, Mudgee, New South Wales, Australia.

When Moore addressed the question of what he described as “an almost total ignorance of the rationale and significance” of hand stencils, he offered, as a summary of his research of the Australian published record, seven categories of their identified use: (1) “individual signature”/marking a visit; (2) memorialization; (3) address to ancestor spirits; (4) communication with others; (5) historical record; (6) symbolic inscription of myth; (7) invocation of sorcery ([97], p. 318, p. 322). From a global standpoint Bahn similarly prioritized signature: “they could be signatures, property marks, memorials, love magic, a wish to leave a mark in some sacred place, a sign of caring about or being responsible for a site, a record of growth, or a personal marker—‘I was here’” ([73], p. 115). For Tresize, hand stencils at Cape York are “mankind’s signature” ([42], frontispiece), but they also serve the function of individual inscription: “Hand and foot stencils they [Aborigines] regarded as signatures” ([81], p. 14).

The “ownership” or recognizability of stencils has had relevance in the Australian Aboriginal land rights context. Layton, who worked on the Cox River (Alawa/Ngandji) Land Claim between 1979 and 1981 ([106], p. 238), witnessed Clara Tonson’s identification of hand stencils at a Gulf country site, including her own, and those made by made people she knew in commemoration of victims of colonial violence ([25], pp. 75–76)—thus attesting to their function as autographs.

Unfortunately, people are liable to read the notion of a hand stencil as a signature very narrowly and reductively: something like the “I was here” idea. The assumption is that, since hands carry visible traces of personal identity, they amount to nothing more than an autograph. However, with hand stencils (and prints) we are not just reading identity cues. Hand marks are already more than a signature of the kind we put on a check or other document. In this sense Bouissac is right when, investigating the part it might have had in the emergence of symbolic systems, he rejects an appeal to restricted “‘deictic’ meaning” of the “‘I am so and so, and I was here’” variety ([102], pp. 91–92). At the same time, we cannot simply dismiss the hand mark’s quality of personal immediacy. Rather we need to reinterpret, and deepen our understanding of, this quality as something over and above mere “signature”. In this connection it is my aim to begin by proposing a universally accessible primary meaning relating to the biological source of hand images, viz. their issuance from the motions of exploratory/performatory bodies.

6.2. The “Ecological Self”

Exchanges between philosophers and cognitive scientists about notions of “ecological self-awareness” [107,108] or the “ecological self” [109], the “specification of the self as a place” [107], awareness of “self-agency” and “body-ownership” ([93,110,111], and the role of proprioception (awareness of the position of and forces within different parts of the body) in self-recognition [112], suggest a new approach to stencils and handprints. Both positives and negatives should be seen as marks recording acts of self-recognition in relation to the environment, self-recognition in the sense of an awareness that I am doing this, i.e., having this effect on the world. The fact that such marks remain as traces of an individual act endows them with a special status, one which derives from their visually-readable register of their makers’ embodied and environed life. This is what I wish to focus on at this point in the argument: the stencil/print not simply as a record of identity or personal presence (“I am X” or “X was here”), i.e., the “author-identity” of the image, but the image as the record of an individual action or event. We recall that, while stencils and prints do not depict hands, they have the “canonical form” [92,113] of hands, thus allowing them to be read as hands, not merely human hands in general but the hands of particular people. However, this is not the whole story, and perhaps not even the critical point. What makes the stencil/print unique as an image? I have already alluded to this by referring to its “immediacy”, its providing a “direct” record of something. This directness is tied to the image as a trace of the action that produced it. A stencil differs from a depiction, say the Mona Lisa, both as a record of the event of its making and as a record of the identity of its maker. To begin with, it records not various events but a single event. Therefore, it has the immediacy of that single act. Moreover, it is self-referential in a way the Mona Lisa is not. What of the self-portrait by Leonardo (the famous one in Turin)? That would be a picture of, not a direct trace of the author. The stencil is critically a trace, direct in that it is a trace of an (authored) event, and peculiarly of the event as event. All pictures refer back to the act that produced them, but not in this way. What is unique about stencils is the fact of iconicity intimately one with its making, the act that endures as a trace. However, what brings such uniqueness into play? What exactly is involved when I leave an image of my hand on a rock surface? It might be asked: do we need to go beyond our quotidian appreciation of ourselves in the world to understand something as obvious as a visual autograph? The fact is that there is a growing literature on the subject of human body awareness that may help to deepen this understanding, ultimately providing evidence for a link between “perception of one’s own and others’ bodies” ([114], p. 4). If we are interested in the way hand marks—so frequent in rock art, so straightforward in their manufacture and so transparent in their iconic readability—function both to specify self-recognition in the act of marking (as “act-identity” and not merely “author-identity”) and, in due course, for person-to-person communication, cognitive psychology and neuroscience are promising fields. I shall begin with an examination of the act of making a stencil or print.

Logically, this means we first need to look at the “ecological self” engaged in the spaces we occupy in a specific environment by attending to the manner in which we make use of its affordances (to employ Gibson’s word). These will be affordances for shelter and nourishment, for facilitated locomotion and, relevant for the present context, occasions for self-reflection and, concomitantly, communication. When we approach the topic of hand-marking from the perspective of what Shontz chooses to call the “embedded self” ([115], p. 94), the human body itself comes into focus as a the sole tool employed in an interaction with the environment—a hand on the rock wall, minerals ejected from the mouth—to produce a mark which affords an opportunity for self-recognition. At this point, we, as rock art researchers, are compelled to engage in a new conversation with cognitive psychologists about the way a perceiving self perceives itself. From this point of view, our preoccupation will be the emergence of a specified self, which has its origins in “an awareness of where we are, what we are doing, and what we have done” ([109], p. 9).