1. Introduction

A global fashion wave sparked by Alexander the Great and Aśoka the Great reshaped Chinese decorative aesthetics, initiating a millennium-long material revolution and cultural reinterpretation. The story begins in the second century BCE, when Han-dynasty envoys set sail from Hepu 合浦, carrying gold and silk to the kingdom of Huangzhi 黄支 (Kanchipuram) in South India to procure “luminous pearls,

bi liuli 璧流离, and exotic stones” (

Ban 1962, p. 1671). At roughly the same time, envoys to the kingdom of Jibin 罽宾 (Kashmir) in northwestern India recorded the local specialty,

bi liuli (

Ban 1962, p. 3885). Thus began the eastward flow of

bi liuli (also rendered as

liuli 琉璃 or

liuli 瑠璃) along both the maritime and overland Silk Roads. Prized for its radiance and exotic origin, it became a coveted luxury and a potent status symbol among Han elites. In the first century BCE, the official Huan Kuan 桓宽 noted that “jade, coral, and

liuli are all treasures of the state” (

Huan 1992, p. 28), epitomizing its exalted status.

For over two millennia,

liuli has frequently appeared in ancient Chinese historical records and has become a significant motif in Chinese literature and art. However, scholarly consensus on the etymology of

liuli and the material it denotes remains elusive. Some argue that it is a transliteration of the Sanskrit

vaiḍūrya; others suggest a derivation from Latin

vitrum; still others propose that it is an indigenous Chinese term. The materials identified with

liuli are equally varied, including nearly a dozen candidates such as lapis lazuli, cat’s-eye chrysoberyl, beryl, sapphire, turquoise, glass, and glazed ceramics (e.g.,

Chavannes 1907, p. 182;

Laufer 1912, pp. 111–12;

B. Xiao 1984;

X. Luo 1992;

W. Zhang 1986;

H. Zhang 2010, pp. 1–23;

Zhao 2013;

Q. Li 2010;

Z. Li 2014;

Qi and Li 2018, pp. 3–13). These studies have limitations in both sources and methods: early sinologists and historians relied primarily on texts, whereas later archaeologists focused on material finds, often without effective cross-referencing between the two. Religious texts and visual materials have also been largely overlooked. Crucially, few studies have placed the popularity of

liuli within transcultural circuits and contact zones or undertaken systematic East–West comparisons across texts and artifacts.

This study brings

liuli into view within Indian Ocean networks connecting the Mediterranean, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and China (

Beaujard 2019;

Sen 2014). Through a transcultural—rather than merely cross-cultural—lens, the study integrates historical texts, Buddhist scriptures, archaeological scholarship, and visual evidence to argue that

liuli was co-produced via Indian Ocean trade networks. The approach builds on Welsch’s concept of transculturality (

Welsch 1999), as elaborated in art history and archaeology (

Juneja 2011;

Autiero and Cobb 2021), and engages Subrahmanyam’s “connected histories” (

S. Subrahmanyam 1997). Empirically, it draws on recent maritime archaeology and Indian Ocean studies that highlight multinodal exchanges linking South Asia, Southeast Asia, and China (

Manguin et al. 2011;

Bellina 2017;

Ray 2003;

Autiero 2015). Building on this framework, this study shows how Chinese Buddhist and court actors selectively adopted scriptural prescriptions and luxury conventions and translated them into local media, transforming

liuli into a transcultural artifact whose materials and meanings were reshaped through mobility, translation, and selective adaptation.

2. Defining Liuli: Texts and Materials

Given that

liuli is absent from Chinese texts before the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and first appears specifically as a treasure from Jibin and Huangzhi, the most plausible explanation is that it is a transliteration of a word from one of those regions. During the Han, Huangzhi was located near modern Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu (

Fujita 1936, pp. 83–117), and Jibin was in the Kabul River valley (

Yu 1992, pp. 46–61), which together establishes a South Asian origin for

liuli.

Buddhist texts further confirm this connection. Ancient Chinese Buddhist translators and commentators frequently attributed

liuli to Tianzhu 天竺 (the ancient Chinese term for India). The monk Huilin 慧琳 (737–820), an expert in Sanskrit–Chinese philology) stated that “

liuli is a term from Tianzhu, rendered in Sanskrit as

vaiḍūrya” (

Huilin n.d., p. 464c). A comparison of Chinese Buddhist texts with Sanskrit, Pali, and Gandhari sources reveals that

liuli generally corresponds to

vaiḍūrya in Sanskrit,

veluriya in Pali, and

veḍuriya in Gandhari.

In South Asia,

vaiḍūrya first appears in Pāṇini’s

Aṣṭādhyāyī (c. 4th century BCE), where it refers to a gemstone processed in the town of Vēḷūr (

Master 1944, pp. 304–6). Because the root

vēḷ means “white,” some scholars speculate that

liuli may have originally referred to a white gemstone (

Biswas 1994, pp. 141–42). However,

vēḷ can also mean “pure, luminous, bright” (

Burrow and Emeneau 1984, pp. 499–500). Buddhist sūtras consistently emphasize

liuli’s purity and radiance: “like the priceless and perfectly polished

vaiḍūrya gem, pure and luminous” (

Ratnamati n.d., p. 834c); and “the luster of the

vaiḍūrya jewel surpasses that of all

kācamani gems” (

Xuanzang n.d., p. 1020a). Similar descriptions are found in Pali scriptures (

Fausbøll 1879, p. 418;

Rhys Davids and Carpenter 1903, p. 244). This defining property of purity and radiance imbued

liuli with profound religious significance, as in texts comparing the mind’s innate purity to an untainted

liuli jewel lying in mud (

Dharmakṣema n.d.b, p. 68a). Therefore,

liuli most likely denoted pure, luminous natural gemstones, with luster being its hallmark characteristic.

On the other hand, Kauṭilya’s

Arthaśāstra (c. 4th–3rd century BCE) provides crucial information on the color of

vaiḍūrya. It lists

vaiḍūrya among vital treasury assets, describing its colors as resembling “blue lotus,

śirīṣa flower, water, bamboo leaf, parrot’s wing, turmeric root, cow’s urine, cow’s fat” (

Olivelle 2013, pp. 123, 527–28). The blue lotus is light blue; the

śirīṣa flower, water, and bamboo leaf are green; the parrot’s wing is yellow–green; turmeric root is yellow tinged with green; cow urine is pale yellow; and cow fat is white tinged with yellow. This suggests that

vaiḍūrya was primarily a blue–green gemstone.

The description in the

Arthaśāstra explains why, in the 3rd century CE, the Chinese scholar Meng Kang 孟康 described

liuli as “jade-like in blue-green color 青色如玉” (

Ban 1962, p. 3885) and why Buddhist scriptures refer to

liuli as a “blue-green jewel 青色宝”, using it metaphorically for water and vegetation: “The water in rivers, pools, wells, and springs is clear and full, like blue-green

liuli” (

Dharmakṣema n.d.a, p. 457c). Thus,

vaiḍūrya (

liuli) referred to pure, transparent, lustrous gemstones in blue or green hues.

The Indian term

vaiḍūrya, particularly its Prakrit or Dravidian forms, is the etymological source for numerous Western words, such as uch as Persian and Arabic

bêlûr/

bolur/

ballūr/

billaur/

bulūr, Greek

berullion/

brullios/

beryllos, Latin

beryllus, and English

beryl (

Winder 1990, pp. 28–29). These terms universally refer to beryl—hence Western scholars’ identification of

liuli with beryl.

Beryl is a beryllium–aluminum cyclosilicate with the basic formula Be3Al2(SiO3)6. It crystallizes in the hexagonal system, often forming natural hexagonal prisms, and is transparent to translucent with a vitreous luster. In its pure state, beryl is colorless (the variety goshenite), but trace elements like iron, manganese, or chromium impart a rich variety of colors, including blue aquamarine, green emerald, golden heliodor, and pink morganite. On this basis, beryl closely matches the color, luster, and transparency attributed to liuli (vaiḍūrya) in textual sources.

Archaeological evidence further solidifies the link between

liuli and beryl. Tombs dating to the 2nd century BCE–4th century CE in southern China have yielded gemstone beads sourced from South Asia, including beryl beads (

Dong et al. 2019;

Luo et al. 2016). For instance,

Figure 1 shows representative examples from Han tombs at Hepu (modern Hepu County, Guangxi), including aquamarine, heliodor, and goshenite (

Xiong 2015, p. 97). Significantly, Hepu was the very port from which Han envoys departed for Huangzhi in South India to purchase

liuli. These gemstone beads are therefore very likely to be the physical specimens of

liuli mentioned in Han records. Furthermore, these archaeological finds explain why the 3rd-century scholar Zhang Yi 张揖 defined

liuli simply as beads (

Qian 2016, p. 731)—this was its most common form when it first entered China.

However, without precise instruments or modern mineralogy, ancient observers often grouped gemstones by appearance rather than composition. This is evident in Pliny’s

Natural History, where he classifies Indian beryl by color—including a golden-hued

chrysoberyllus and a paler

chrysoprasus (

Eichholz 1962, pp. 225–27). From a modern mineralogical perspective,

chrysoprasus is often interpreted as chrysoprase (a chalcedony, SiO

2), while

chrysoberyllus likely included chrysoberyl (BeAl

2O

4) and heliodor (yellow beryl). Although chrysoprase and chrysoberyl are mineralogically distinct from beryl, their yellow–green hues readily invited misidentification. Some chrysoberyls also display chatoyancy (the cat’s-eye effect), which may explain descriptions in

Ratnaparikṣā, a 6th-century Sanskrit lapidary treatise, where

vaiḍūrya is said to show shifting colors and a single band of light—hence some scholars equate

vaiḍūrya (

liuli) with cat’s-eye chrysoberyl (

Finot 1896, pp. 43–45). Tamil lexica corroborate this semantic mapping, with

vaiṭūriyam (from Skt.

vaiḍūrya) commonly glossed as cat’s-eye and included among the

navamaṇi (nine jewels).

Even today, visual confusion is easy without analytical tools. When the beads in

Figure 1 were first excavated, archaeologists identified them as variously colored rock crystal. Only later did scientific analysis reveal that they were actually beryl, rock crystal, and chalcedony. Despite belonging to different minerals, they share strong visual similarities and their colors correspond remarkably well with the descriptions of

liuli in the

Arthaśāstra. Therefore, this study suggests that

liuli encountered by Han Chinese cannot be strictly equated with a single modern gemstone species. Instead, it should be understood—with due caution—as a general term for transparent or lustrous blue–green gemstones, primarily represented by beryl.

3. Networks of Gem Trade: Eurasian Routes Behind Liuli

The liuli beads from Hepu are material witnesses to the sweeping Eurasian jewelry trade and aesthetic trends of the latter half of the first millennium BCE—a circulation made possible by supply-side dynamics: Mediterranean demand, Mauryan statecraft, monsoon sailing, and Southeast Asian transit hubs.

The formation of this far-reaching circulation system can be traced back to the 4th century BCE. Alexander the Great’s eastern campaigns ignited Mediterranean demand for South Asian gems (

Harrell 2011, pp. 151–52). Situated on Eurasia’s prime gem belt, South Asia yielded aquamarine, emerald, ruby, sapphire, diamond, garnet, chalcedony, pearls, and tortoiseshell—all new luxuries for the Mediterranean world. From this point onward, references to Indian gems appear with increasing frequency in Western writings. Theophrastus’s

On Stones (c. 314/315 BCE), the earliest detailed Western work on gems, mentions pearls from India (

Caley and Richards 1956, pp. 52–53). The poet Addaeus of Macedon speaks of a renowned gem engraver who carved a statue of the goddess Galene from Indian beryl, whose sea-green hue perfectly suited the deity of calm seas (

Paton 1917, pp. 301–3). Posidippus of Pella (3rd century BCE) also mentions “sparkling beryl” (

Kosmetatou and Acosta-Hughes n.d., p. 2).

The influx of new materials influenced Mediterranean aesthetics. Greek jewelers, working in a cosmopolitan milieu, incorporated diverse exotic gems into single pieces, creating a vivid polychrome style. A Hellenistic necklace in the Cleveland Museum of Art (

Figure 2), combining moonstone, garnet, chalcedony, emerald, pearl, and onyx, exemplifies this trend. This pursuit of color saturation and gem diversity profoundly influenced subsequent Eurasian jewelry aesthetics.

The expansion of the Mauryan Empire under Aśoka (3rd century BCE) likely further stimulated the gem trade. His empire—reconstructed from the distribution of his edicts and standard historical geography—overlapped with major gem-producing regions: Rajasthan’s emerald (beryl) belt, Odisha’s beryl–rock crystal–chrysoberyl belts, and the Panna diamond fields of central India (

Thapar 2012;

Lahiri 2015;

IBM 2016;

Das et al. 2020;

Government of Odisha 2006;

Rau 2007;

MECL 2023). Concurrently, the

Arthaśāstra brought gems and minerals under state supervision, standardizing inspection, storage, weights, measures, roads, and customs. Taken together, these institutional reforms facilitated the movement of high-value goods across regions.

As Mauryan influence extended southward through the Deccan corridors—even if the Tamil polities largely remained beyond direct imperial control—connections with southern gem sources intensified. A grammatical note in Pāṇini’s

Aṣṭādhyāyī (c. 4th century BCE) links

vaiḍūrya to a workshop site called Vēḷūr, often identified with the Tamil region—evidence of early north–south knowledge exchange (

Master 1944;

Biswas 1994). Later texts place

vaiḍūrya on Vidūra mountain, commonly identified with the Shevaroy Hills in Salem District; modern surveys attest to the presence of beryl and rock crystal across the wider Salem–Erode–Coimbatore belt (

GSI 2006,

2013;

Biswas 2001). Ptolemy’s Geography likewise names the small South Indian kingdom of Punnāṭa as a beryl source, traditionally placed in southern Karnataka along the Kaveri–Kabini corridor, adjacent to the Coimbatore–Kongu route (

McCrindle 1885;

Rice 1909).

Against this backdrop of state policy and southward-oriented corridors, references to

vaiḍūrya grew more frequent in late first-millennium BCE texts. The

Arthaśāstra classifies pearls, rubies, beryl, sapphire, rock crystal, and diamonds as treasury assets, highlighting their economic value. In the

Mahābhārata and

Rāmāyaṇa, which took shape across this period,

vaiḍūrya appears more frequently than any other gemstone, with pearls ranking next, signaling its cultural and material significance (

Kanungo 2017, p. 27). Notably, luminous pearls and

liuli are also the very items Han envoys report purchasing at Huangzhi in South India, highlighting these items as interregional luxury staples of the time.

Building on the internally forged corridors described above, archaeological and textual sources attest to seaborne movements of South Indian gems from the late first millennium BCE. By the early first century CE, those inland–coastal networks had coalesced into a broader Indian Ocean trading system, as Roman merchants—riding the monsoon—sailed directly to west-coast ports such as Muziris and Nelcynda, exchanging Mediterranean goods for pearls, ivory, tortoiseshell, diamonds, sapphires, “transparent gems,” and Chinese silk (

Casson 1989, pp. 75, 81, 85). Given the proximity of these outlets to beryl-rich provinces, those “transparent gems” almost certainly included

vaiḍūrya.

The trade in gems, spices, and silk caused a substantial outflow of Roman precious metals. Pliny famously lamented the vast sums of Roman coinage flowing annually to India, China, and Arabia. Archaeological evidence supports this: Roman coins from the 1st–3rd centuries CE cluster in South Indian sites such as Karur, Vellalore (near Coimbatore), and the Madurai region—consistent with corridors linking coastal marts and the Salem–Erode–Coimbatore gem belt (

Krishnamurthy 1994;

Nagaswamy 1995;

Ray 2003;

GSI 2006,

2013). As direct trade expanded, Greco-Roman writers recorded increasingly specific details about Indian gems, from Pliny’s notices on Indian beryl to Ptolemy’s identification of Punnāṭa as a beryl source.

From the South Asian side, Sangam-age Tamil texts provide matching evidence:

Paṭṭiṉappālai portrays Kāvēripūmpattinam (Puhar) as a maritime entrepôt with busy harbors, warehouses, customs houses, and inflows of imported valuables, while the Buddhist

Maṇimēkalai preserves extended gem lists and coastal itineraries—literary corroboration that dovetails with the Periplus and the coin distributions (

Zvelebil 1973;

Hart and Heifetz 1999;

Hart n.d.).

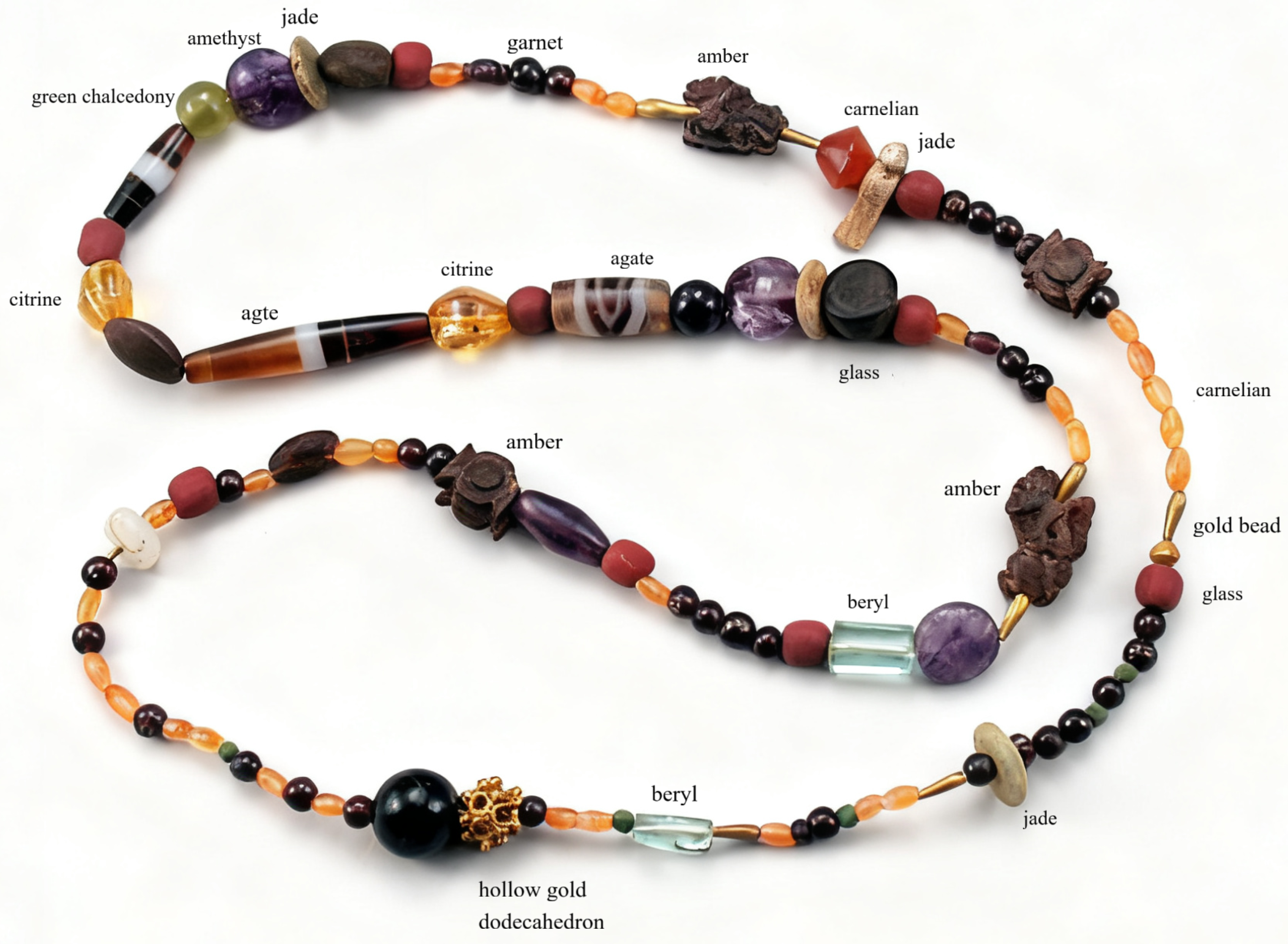

Archaeological evidence from Southeast Asia further reveals an eastward extension of the Indian gem trade. Key sites in Peninsular Thailand and Vietnam—notably Khao Sam Kaeo in southern Thailand, Sa Huynh sites in central Vietnam, and Óc Eo–culture sites in the Mekong Delta—have yielded finished and semi-finished ornaments alongside small raw fragments (

Figure 3). Finds include carnelian, agate, garnet, rock crystal, and—at some sites—beryl. Technological and compositional analyses connect many of these beads to South Asian production techniques—drilling, etching, heat-treatment—and to long-distance circulation routes. Farther south at Sungai Mas (Kedah, Bujang Valley), artifacts and compositional studies indicate local working and redistribution within an Indo-Pacific network (

Francis 1990,

2002;

Glover and Bellina 2001,

2011;

Bellina 2003,

2017;

Ramli et al. 2012).

The co-occurrence of South Asian, Mediterranean, and Chinese imports within the same strata at sites like Khao Sam Kaeo demonstrates that Southeast Asia served as both a processing hub and transit corridor, beyond its role as a consumer market (

Glover and Bellina 2011;

Bellina 2017). This is vividly illustrated by semi-finished carnelian and agate beads from the site, worked with South Asian techniques and closely matching finished beads from contemporary South Chinese tombs, marking Southeast Asia as a key relay station in the long-distance circulation of bead types and forms (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Taken together with the westbound trade described in the

Periplus Maris Erythraei, these eastward circuits position Southeast Asia as a critical hinge linking South Asian source regions to the South China coast.

By this stage, a vast Indian Ocean gem trade network—stretching from the Mediterranean to the Indochinese Peninsula—had clearly taken shape. South Asian gems, Roman precious metals, and Southeast Asian processing centers and shipping hubs together formed a vibrant early globalized economy. This well-established network set the stage for the grand entrance of the next major player from the East.

4. Foreign Gemstones and the Remaking of Han–Jin Aesthetics

The “starting point” of cross-regional gem exchange into South China predates Emperor Wu’s missions to Huangzhi. From the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) onward, burials in South China have yielded small numbers of foreign glass beads, faience beads, and gemstone beads, indicating that long-distance routes for prestige objects were already emerging. The unification wars of the late third century BCE—especially the Qin conquest of Lingnan 岭南 (roughly modern Guangdong and Guangxi)—likely further stimulated these channels.

Soon after, the Qin general Zhao Tuo 赵佗 (r. ca. 203–137 BCE) carved out an autonomous kingdom of Nanyue 南越 in Lingnan, with its capital at Panyu 番禺 (modern Guangzhou). In the early Western Han, when Han envoys visited Nanyue, Zhao Tuo bribed them with jewels of great value (

Sima 1982, pp. 2698–99). In light of maritime archaeological finds from South and Southeast Asia, these jewels most plausibly included imported gemstone and glass products. The burial of the Nanyue King at Guangzhou (interred 122 BCE) sharpens this picture: alongside a jade suit and local bronzes, the tomb contained a persianizing lobed silver box, African elephant ivory, and aromatics traceable to the Arabian Peninsula. Such an assemblage indicates that by the early second century BCE, Panyu already participated in a mature maritime luxury network linking South China with the Indian Ocean world.

By the time Sima Qian 司马迁 composed the

Shiji 史记 (

Records of the Grand Historian) at the end of the second century BCE, Panyu was portrayed as a southern metropolis where “beads, ivory, rhinoceros horn, tortoiseshell, fruits, and cloth converged” (

Sima 1982, p. 3268), with beads listed first—an ordering that underscores the prominence of the gem trade in the regional economy. Archaeology corroborates this: numerous Western Han (206 BCE–9 CE) tombs in Guangdong and Guangxi have yielded thousands of beads of South and Southeast Asian types, revealing how firmly foreign luxuries had entered local elite assemblages. Multiple sites and tomb groups across Yunnan, Hunan, and Jiangxi provinces have produced similar South Asian–type gemstone beads, highlighting the breadth of this phenomenon (

Xiong 2018, pp. 90–110;

Guangzhou Municipal Institute of Cultural Heritage and Archaeology 2020;

Hunan Provincial Museum 2018, pp. 129–44). In other words, by the Qin–Western Han transition, a network for foreign gem exchange was already in place; Emperor Wu’s envoys to Huangzhi were extending, rather than creating, these maritime corridors.

Within this context, foreign gemstones began to reshape Han elite aesthetics. Literary sources offer a vivid glimpse of this influence. Ge Hong 葛洪 (283–343 CE), in

Xijing zaji 西京杂记 (

Miscellanies of the Western Capital), records the rise of this fashion in Chang’an 长安 (the Han capital, today’s Xi’an): “During Emperor Wu’s reign (r. 141–87 BCE), the kingdom of Shendu 身毒 (an early Chinese term for India) presented a chain harness made entirely of white jade, with agate for the bridle and luminous white

liuli for the saddle. In a dark room, the saddle glowed for over ten

zhang 丈 (≈23 m), as bright as daylight. From then on, the elite in Chang’an competed in lavishly carved saddle and horse ornaments. Some sets of these decorations cost a hundred gold pieces, and were embellished with white

Tridacna shells from the South China Sea and ornate patterns of purple-gold.” (

Ge 2006, p. 79). Hyperbole aside, the anecdote encapsulates how imported gems circulating through southern ports could stimulate new forms of conspicuous ornament at the imperial center.

Corroborating this picture archaeologically, a pendant set from a Western Han tomb in Guangzhou (

Figure 4), composed of beryl, rock crystal, agate, amber, and carnelian, shows how high-luster, vividly colored gems stood out within the generally formal, regulated Han decorative system and became objects of display and competition. Perhaps the most telling parallel comes from the tomb of Liu He 刘贺 in Jiangxi Province. The briefly reigning emperor was buried not only with multiple white-jade ornaments from the indigenous repertoire but also with beads of agate, carnelian, rock crystal, and amber (

S. Li 2017, pp. 9–28;

Xu 2023, pp. 87–88). In both material and form, these beads closely match the pendant set from the Guangzhou Han tomb; similar examples from Hunan and Guangxi are usually interpreted as imports from South and Southeast Asia (

Dong et al. 2019;

Luo et al. 2016). Together, texts and finds show how foreign gemstones were paired with long-cherished white jade—dense with local symbolic value—and integrated into a reconfigured Han imperial aesthetic (

Figure 5).

This remaking operated not only at the level of materials but also through more specific preferences in cutting, form, and gem lore. Pliny notes that India was a prime source of beryl and Indians preferred to retain beryl’s natural hexagonal prism shape, believing it enhanced the stone’s color through light reflection on its facets. Long, slender crystals were especially valued—regarded as the only true precious stones—and were left unpierced and strung rather than set in gold. The most flawless specimens were left unpierced but capped with a domed gold cover at one end (

Eichholz 1962, pp. 225–27). This taste for displaying the crystal form became an international aesthetic, visible in prismatic beryl beads from sites such as Hepu and Guangzhou, as well as in emerald necklaces from the Roman Empire (see

Figure 6).

Emerald, the vivid green variety of beryl, gained exceptional prominence in the early centuries CE, partly due to intensive mining of deposits in Egypt’s Eastern Desert (at sites such as Mons Smaragdus and Wadi Sikait) under Ptolemaic and later Roman control (

Harrell 2004). In Roman-Egyptian mummy portraits, elite women are often depicted wearing necklaces of hexagonal emerald prisms (

Figure 7)—a form also commonly found in burials. Similar necklaces preserved in museum collections further confirm the popularity of this style.

In South Asia, emerald was likewise revered. Sanskrit texts designate it as

marakata and surround it with elaborate origin myths, such as the belief that it formed from the saliva or body of the divine bird Garuḍa (

Huilin n.d., T. 2128, 54: 641c). The Latin

smaragdus and Sanskrit

marakata are often treated as belonging to a related lexical family for bright green stones, reflecting a shared vocabulary across the Mediterranean and South Asia. This relationship points to dense, long-term exchanges of gem knowledge between these regions, rather than a simple one-way borrowing. A material reflection of these interconnections can be seen in a gold necklace (The British Museum, acc. no. AF.323) from Roman Tunisia, set with green emeralds probably from Egyptian deposits and blue sapphires sourced from South Asia.

Chinese writers also recognized emerald as a prestigious foreign gem linked both to India and to the Rome Empire. They adopted the term

munan 木难 for emerald, a designation clearly linked to Latin

smaragdus and Sanskrit

marakata (

H. Zhang 1934).

Xuanzhong ji 玄中记 (

Mysteries within the Universe, c. 3rd–5th CE) notes that

munan comes from Daqin 大秦 (a Chinese term for the Roman Empire) (

F. Li 1960, p. 3595), a remark consistent with Roman control of the Egyptian emerald mines in the early centuries CE (

Harrell 2004, pp. 69–76).

Nanyue Zhi 南越志 (

Records of Nanyue, c. 5th century CE) repeats the Garuḍa-origin legend and adds that the people of Daqin greatly valued this gem (

F. Li 1960, p. 3595). Taken together, these concise but precise accounts show that Chinese scholars understood emerald as having a dual identity—mythologically grounded in India yet commercially associated with Rome—indicating that the Afro-Eurasian networks shaping Chinese elite aesthetics transmitted not only gemstones and cutting styles but also the stories and meanings attached to them.

Chinese literature absorbed these foreign luxuries as markers of feminine beauty and elite identity. The 1st-century poet Xin Yannian 辛延年 depicts a foreign girl “with Lantian 蓝田 jade upon her head and Daqin beads behind her ears” (

Huang 2008, p. 262), while 3rd-century Cao Zhi 曹植 evokes a beauty whose “bright beads adorn her jade-like form, coral interspersed with

munan” (

Cao 2008, p. 117). Both Daqin beads and

munan refer specifically to emerald. Xin’s contrast between the intense color of imported gems and the soft lustre of jade finds a direct material parallel in the pairing of white jade and foreign gemstones in Liu He’s tomb. Cao Zhi’s combination of red coral (also associated with Daqin) and green emerald, meanwhile, echoes the polychrome style of Roman necklaces (

Figure 8). Through such literary reframing, the visual and material vocabulary of a connected Afro-Eurasian gem trade was woven into Chinese aesthetic culture, showing how imported ornaments helped redefine Han–Jin decorative ideals.

5. From Gemstone to Glass: Imitation and Reclassification of Liuli

The prosperity of the gem trade inevitably spurred imitation, beginning in the source regions. Pliny records Indian artisans dyeing rock crystal to imitate beryl. Mediterranean artisans were equally adept; counterfeit emeralds (as in

Figure 9) were widespread. Counterfeiting became so rampant that it entered Buddhist sūtras as a moral lesson: “Merchants in Jambudvīpa should be aware: this land of treasures holds many counterfeit

liuli that closely resemble genuine ones. Be sure to test them carefully before taking them—otherwise, you may return home only to regret it” (

Yijing n.d., p. 801a).

A more widespread method of counterfeiting involved glass. Glass emerged over four thousand years ago along the eastern Mediterranean, and from the beginning was used to imitate various gemstones and even adopt their names. At the time, lapis lazuli was popular along the eastern Mediterranean, so glass was often opaque and deep blue, and was also referred to as lapis lazuli. To distinguish the two, Egyptians often emphasized the word “genuine” when referring to lapis lazuli, while Akkadians differentiated between “lapis lazuli from kiln” and “lapis lazuli from the mountains” (

Whitehouse 2016, p. 19).

By the end of the first millennium BCE, transparent and semi-transparent gemstones gained popularity and became models for glass simulants. Around the turn of the Common Era, the Roman glass industry developed rapidly, mastering the replication of colors and translucency for a wide variety of gems. The Roman-Egyptian industry, based on natron glass, achieved mass production of transparent vessels and sheets, supplying raw glass across the Mediterranean and providing the material basis for gemstone imitation (

Nicholson and Shaw 2000;

Jackson et al. 2018).

In the first few centuries of the Common Era, glass counterfeiting of

liuli became trans-Eurasian. Hepu Han tombs yielded both genuine gems and imitations: pale green hexagonal glass beads perfectly replicated beryl morphology (

Figure 10). Scientific analysis identifies them as medium potash-lime-alumina glass imported from South Asia (

Xiong 2018, p. 84). Arikamedu, an ancient port in Tamil Nadu, India, served as a vital hub for trade with Rome. Glass beads unearthed at this site were primarily blue and green, followed by red—colors clearly intended to imitate gemstones like beryl and ruby, which were highly valued at the time (

Biswas and Biswas 1996, p. 306).

Such imitation beads spread across the Old World: hexagonal glass beads from Roman-era London (Museum of London, MSL87[252]<565>) and Naucratis, Egypt (BM 2509.10), show a rich green with relatively low transparency and were likely intended as imitations of emerald. Meanwhile, examples from Jiangchuan (Yunnan), Zagunluk (Xinjiang), as well as Ban Don Ta Phet and Óc Eo in Southeast Asia—dating from the 4th century BCE to the 2nd century CE—closely resemble those from Hepu with their relatively transparent, pale blue-green tone, probably imitating aquamarine (

Gan et al. 2009, pp. 27, 305;

Glover and Bellina 2011, pp. 33–34). Beyond merely illustrating the interconnected web of trade and artistic imitation surrounding

liuli across the Silk Roads—both overland and maritime—these cases speak to a deeper chromatic language of desire. The nuanced variations in hue among imitation products reveal distinct regional visual cultures and aesthetic predilections for specific varieties of gemstone

liuli, reflecting localized ideals of beauty and value.

Texts and archaeology show that glass imitations were cheaper than genuine gems. A passage from the

Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra (c. 1st century CE onwards) contrasts precious, naturally occurring

vaiḍūrya with cheap, man-made

kāca (glass), stating that a fool would abandon a priceless

vaiḍūrya for a kāca imitation (

Xuanzang n.d., pp. 891b, 1015c). Archaeology in Southeast Asia and South China shows that glass beads (especially small Indo-Pacific beads) were widespread and common, found in tombs across social strata, while stone beads like carnelian, agate, garnet, and beryl were rarer, more carefully composed, and often associated with higher-status burials.

The widespread use of glass imitations labeled

liuli was likely a key factor in the term’s semantic shift in China. In the 2nd century BCE, the

bi liuli brought back by Han envoys from India were most likely natural gemstones. However, genuine pieces were rare, expensive, and mostly small beads, limiting their prevalence. At the same time, artificial versions—also labeled

liuli—were flooding in; benefiting from lower cost and diverse forms (as in

Figure 11, whose color is similar to that of the beryl-imitating beads in

Figure 10), they rapidly achieved far greater ubiquity than the genuine gems. Thus, the sacred gem name

liuli was gradually transferred onto glass and later, within China, onto glazed ceramics.

Texts document this semantic drift. In the 3rd century CE, Wan Zhen 万震, in the

Nanzhou yiwu zhi 南州异物志 (

Records of Strange Things from the Southern Regions), wrote that “

liuli is produced with natural soda ash sourced from the shores of the Southern Sea,” a description that clearly points to glassmaking in southern China and to products intended to imitate beryl (

Ouyang 1985, p. 1441).

Shishuo xinyu 世说新语 (

A New Account of the Tales of the World) records that Western Jin emperor Wu (r. 265–290 CE) used “

liuli for window screens” that were “as transparent as if nothing were there,” (

Liu 2007, p. 97) a passage generally understood to refer to imported or imitated Roman-style window glass (

Velo-Gala and Garriguet Mata 2017).

Nan Qishu 南齐书 (

Book of Southern Qi) notes that Northern Wei palaces had “

liuli tiles” (

Z. Xiao 1972, p. 986), where the term denotes glazed ceramic. By the 7th century, the scholar Yan Shigu 颜师古, criticizing Meng Kang’s definition of

liuli as a blue-green gemstone, stated that Daqin produced

liuli in ten colors, “all made by smelting mineral liquids,” showing that even erudite scholars of the Tang era now understood

liuli exclusively as man-made glass rather than as a natural gem (

Ban 1962, p. 3885).

Along with glass products came the transfer of glassmaking technology. In the fifth century, a merchant from the Da Yuezhi 大月氏 (the Great Yuezhi, a Central Asian polity) brought advanced glassmaking techniques to the Northern Wei court, producing “multi-colored

liuli” that was said to have made glass cheaper in China (

S. Wei 1974, p. 2275), though this technology appears to have been lost later. In the late sixth century, the Sui court artisan He Chou 何稠 (possibly of Sogdian descent) is recorded as producing green

liuli and is credited with reviving the technique (

Z. Wei 1973, p. 1596). In the early seventh century, the noble girl Li Jingxun 李静训 was buried with several green glass vessels. As she was raised in the palace and the vessels are of Chinese shapes, they might be examples of He Chou’s revived green

liuli.

The girl also wore ornate jewelry, including a pair of bracelets inlaid with green glass (

Figure 12). Their design evokes contemporary Byzantine bracelets set with emeralds, notably the square green glass settings that mirror the common square-cut emeralds in Western jewelry. Her family maintained Western connections: her great-grandfather’s tomb yielded Western objects, including a gilded silver ewer with repoussé Roman figural scenes (

F. Luo 2000, pp. 311–30). In particular, the girl’s burial necklace is believed to have connections with Byzantium (

Kiss 1984). Taken together, her bracelets were likely imitations of Byzantine designs. Crucially, while Western elites still coveted natural gems, Chinese elites increasingly embraced artificial brilliance, pioneering new material aesthetics.

Because local glassmaking remained unstable, high-quality foreign glassware retained prestige until the Tang. Indigenous lead–barium glass was brittle, prone to weathering, and mostly used for small ornaments or jade imitations, unable to rival the transparency and craftsmanship of imported Western vessels. By contrast, soda-lime glass from West Asia—arriving via the Silk Roads and distinguished by its elegant forms and crystal clarity—was regarded as an imported luxury, reserved for political elites and sacred or ritual contexts and symbolizing power, wealth, and long-distance connections. In the sixth century, the Northern Wei prince Yuan Chen 元琛, known for his extravagance, boasted of owning a “

liuli bowl” from the Western Regions. A Sasanian-style glass cup (

Figure 13) from the eighth-century Hejiacun hoard in Xi’an is explicitly labeled “琉璃杯 (

liuli cup)” on its inventory slip; its discovery amid large stores of gold, silver, and gems underscores its high status (

Shaanxi History Museum et al. 2003, p. 214).

After the tenth century, glass entered more routine use in China. Song-period (960–1279 CE) finds and compositional analyses indicate reliance on locally developed recipes—above all high-potassium and potash–lead glasses—alongside continued imports. Glassblowing techniques, introduced earlier from Western and Central Asia, were by this time integrated into Chinese workshop practice, supporting higher output and lowering production costs. At the same time, the social landscape shifted from aristocratic to literati-official culture, and ceramics—with their warm, jade-like qualities and strong indigenous aesthetic associations—better suited elite taste. Consequently, while imported or finely made glass vessels retained a measure of prestige, glass overall gradually yielded pride of place to ceramics within the hierarchy of high-status materials (

An 2011;

Gan et al. 2011;

Henderson et al. 2018).

Texts from the Song dynasty attest to the democratization of glass. Contemporary records frequently document glassware in wine shops, pharmacies, and street vendors’ stalls, marking its descent from courtly display to everyday commerce. This trend was accelerated by sumptuary laws banning pearls and jade, which prompted common women to adopt glass jewelry as a substitute (

Tuotuo 1977, p. 1430). The frequent discovery of such ornaments in non-elite Song tombs provides final confirmation that these once-noble objects had become common adornments.

6. Buddhism’s Role in the Dissemination and Evolution of Liuli

Buddhism emerged in the latter half of the first millennium BCE and interacted closely with the expanding gem trade. Buddhist texts frequently recount sea voyages in search of treasures; in many narratives the Buddha or Bodhisattvas appear, in former lives, as gem merchants. Gold, silver,

liuli 琉璃, coral, amber, mother-of-pearl, and agate became the Seven Treasures (Skt.

saptaratna), offered and interred in stupas. At the Amaravati and Bhattiprolu stupas (Andhra Pradesh), excavations yielded numerous offerings of beryl, crystal, and other gems (

B. Subrahmanyam 1998, pp. 70–71;

Rea 1894, pp. 11–14).

In Buddhist art, Bodhisattvas, deities, and nobles wear elaborate gemstone ornaments, and Gandharan sculpture renders these materials with striking accuracy. A 3rd–4th-century Bodhisattva from Pakistan (

Figure 14) bears strands of beads around the head, with a larger polyhedral prism at the center that recalls a hexagonal beryl crystal. Placing a special bead in the center of a headdress or necklace was common in India; Ajanta paintings show this central stone as often blue or green, sometimes with white highlights to signal transparency and luster.

This distinctive bead likely corresponds to the

jizhu 髻珠 (topknot jewel) of Buddhist texts. The most famous example belongs to Indra and is described as a “

liuli bead” formed from Garuḍa’s heart, a legend that almost certainly associates it with emerald (

Fazang n.d., p. 135b). Texts further indicate that Indian princes and nobles wore such topknot jewels as emblems of rank: when Prince Siddhārtha renounced the world, he removed his crown and topknot jewel (

Guṇabhadra n.d., p. 633b); Xuanzang 玄奘 records King Harṣa donating his crown, necklaces, and topknot jewel and then recovering them—rituals of relinquishing and restoring sovereignty (

Huili and Yancong 2000, p. 112).

Buddhism also transmitted gem culture and styles. In the Kizil Caves (Xinjiang), deities’ headdresses typically center on a blue or green jewel.

Figure 15 shows a vīra whose headdress, necklace, and earrings use rectangular green beads with black lines indicating faceting; the central green stone ultimately derives from the Gandharan polyhedral bead and functions as a topknot jewel. The bead’s color and polyhedral form make an emerald identification plausible, while the alternation of green polyhedral beads and red beads echoes both Cao Zhi’s “coral interspersed with

munan” and Mediterranean red–green bead strings.

In another Kizil mural, the portraits of the Kucha king and queen are depicted not in standard Buddhist attire but in what is likely their actual court regalia (

Zhou 2009, p. 205). Yet their headdresses still display a central green jewel, indicating actual adoption of the topknot-jewel type (

Figure 16). The queen’s jewel is a circular cabochon rather than a prism, which may suggest local adaptation of the Indian tradition.

Buddhism was not only a witness and transmitter of

liuli culture; it actively reshaped its meanings, uses, and chromatic symbolism. To this day, Buddhist temples often display images with gilded bodies and deep blue hair. This palette is not arbitrary but scriptural: sutras describe the hair, eyebrows, and pupils of Buddhas as the color of

liuli, sometimes specified as dark indigo—clearly not the hue of beryl. This seeming discrepancy stems from Buddhism’s assimilation and reinterpretation of ancient Mediterranean gem aesthetics: in Egyptian and Mesopotamian traditions, divine hair was described as lapis lazuli blue and even fashioned from lapis (

Zheng 2021). Through this process,

liuli shifted from a gemstone referent to a sacral blue chroma and a privileged material in Buddhist imagery and practice.

Lapis lazuli mining and East–West trade date back to prehistory, and for millennia they played a crucial role. However, by the latter half of the first millennium BCE, their status and popularity declined significantly, so much so that the term sappîr, once referring to lapis lazuli, became the name for sapphire. During its formation and spread, Buddhism was influenced by Near Eastern and West Asian religions. The ancient role of lapis lazuli in West Asia was absorbed and substituted in Buddhism by the newer liuli. This is precisely why some scholars, studying liuli through Buddhist texts, concluded it was lapis lazuli.

When Buddhism gained wide popularity in China after the 3rd century CE,

liuli in Chinese usage had already come to mean glass. It was therefore natural to use glass in offerings to Buddhas, relics, and monasteries. Thousands of glass objects from the relic crypt of the Northern Wei pagoda at Dingxian, Hebei attest to high-value

liuli donations by imperial and noble patrons (

Hebei Sheng Wenhua Ju Wenwu Gongzuodui 1966). In a Tang mural of Mogao Cave 159, a Bodhisattva holds a

liuli bowl closely comparable to the glass cup from Hejiacun (

Zhao 2014). The Famen Temple pagoda yielded twenty fine glass vessels—domestic and imported—explicitly recorded on a stele as

liuli offered by the Tang emperor to the Buddha’s relics (

Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology 2007, pp. 211–20).

The widespread flourishing of Buddhism in China between the 3rd and 10th centuries imbued the frequently mentioned

liuli with profound sacred significance, elevating it to a key motif in literature, art, and architecture. A telling example is the imperial ambition to construct palaces of blue-green

liuli. This stemmed from Buddhist sutras’ descriptions of pure lands and Wheel-Turning Kings’ realms as being made of this substance—a material representation meant to visually identify the emperor’s domain with the Buddha-land and his person with the Buddha (

Zheng and Guo 2025). Consequently, the high value accorded to glass during this period must be attributed not only to its technical novelty and exotic status but also to these potent religious associations.

The concept of

liuli palaces was ultimately realized in glazed ceramic, not in gemstones or glass. Before the 10th century, glaze and glass shared the name

liuli due to their visual and technical similarities. This changed after the Song dynasty, when the two materials decisively diverged. Domestic glass production matured into a distinct industry for everyday objects, while glazed ceramic became the preeminent architectural material, evident in the colored tiles of Yuan, Ming, and Qing palaces and temples. Its opaque, vivid appearance and structural role cemented a unique architectural identity. As a result,

liuli became the specific name for glazed ceramic, while glass came to be known as

boli 玻璃—a term likely borrowed from the Indian

spaṭika (for crystal-clear gems) via Buddhism. This semantic shift cemented glazed ceramic’s status as the legitimate

liuli, leading to its natural integration into Buddhist art and practice, as exemplified by a glazed reliquary from the Northern Song pagoda foundation at Fahai Temple in Mixian, Henan (

Jin 1972).

The millennial transformation of liuli thereby concluded. In the modern Chinese lexicon, the term is firmly anchored to the glazed ceramics of the Forbidden City. Its ancient identity as beryl, most notably emerald, faded from collective memory and was rechristened after the Song dynasty as zhumula 助木剌—a loan from Persian-Arabic zumurrud. This ultimate renaming mirrors the realignment of Eurasian trade networks, a pivotal change that opens a new chapter in the history of material exchange.

7. Conclusions

Liuli—first a term for lustrous South Asian gemstones—entered China and came to name the green glaze on Song-dynasty roof ridges. This long material-and-semantic shift shows how closely Eurasian worlds were connected. From the late first millennium BCE, Alexander’s eastern campaigns, Aśoka’s consolidation, and Qin–Han expansion opened routes that moved gemstones, techniques, and color ideas across Afro-Eurasia. Emerald prisms in Mediterranean dress, beryl strands from Hepu, and jeweled headdresses in Kucha together mark a shared taste for brilliant color and light.

Prestige, however, encouraged substitution. As Roman–Egyptian glass achieved gem-like color and translucency, liuli in circulation increasingly arrived as manufactured brilliance. In China, this was not passive borrowing but transcultural co-production: Buddhist and courtly actors selected scriptural and luxury motifs, adapted them to local media, and transformed their meanings and uses. As a result, liuli’s referent shifted—from gemstone to imported glass and, by the Song, to architectural glaze—reshaping both ritual sightlines and built form. In this sense, liuli names not a fixed substance but a mobile signifier whose value lies in its rematerialization within new regimes of making and seeing.

Production and consumption patterns clarify the social gradient. From the late first millennium BCE, liuli—then gemstones and their glass look-alikes—appears in China mainly in elite settings, especially high-status tombs. In the early centuries CE, as glassmaking and trade boomed, glass beadwork lost value at the lower end: local imitation brought glass beads and small ornaments into modest burials. At the top of the hierarchy, by contrast, high-clarity West Asian glass stayed scarce and prestigious, serving royal display and religious ritual from the Han through the Sui–Tang. Only after the Song did better technology and changing taste broaden access: urban workshops standardized formulas and shapes, and glassware and ornaments entered everyday use. In short, liuli moved from exotic import to urban commonplace—not by a simple, one-way diffusion, but through a long coexistence of elite imports and local imitations that gradually reconfigured Chinese decorative arts across ranks and sites.

Read through a transcultural lens, this case shows how names, colors, and materials travel as entangled biographies. The Indian prismatic topknot jewel becomes, in Kucha, a local cabochon; the Buddhist ideal of the “liuli palace” takes material form as glazed architecture; Near Eastern, lapis-coded divinity is remapped as a sacral blue-green in Buddhist imagery. From Gandhāran topknot jewels to Song glazed tiles, liuli illustrates how selection, adaptation, and creative transformation generate new artistic ecologies. Its significance lies less in policing “authenticity” than in showing how circulation, translation, and rematerialization forge durable, distinctly Chinese forms within a connected Eurasian world.