1. Introduction and Preliminary Analyses

In 2007, French-Canadian artist Gregory Chatonsky completed

Vertigo@home, an audiovisual work that reimagines Scottie’s peregrinations through San Francisco in Alfred Hitchcock’s

Vertigo, using Google Streetview. Recalling pilgrimages that still exist to the film’s original shooting locations, Chatonsky leads us from the streets of Nob Hill to the Bay by following the white directional arrows of the navigation interface. Scottie (played by James Stewart) is, however, never visible, nor is any concrete action depicted.

Vertigo is rather restituted or reassembled from a point of view that hangs over the streets and avenues, through the slightly elevated mechanical gaze of the Street Views cars that capture images of urban space (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Whenever the character is meant to enter a private residence, the screen turns black, marking the limit of what the navigation cameras can capture. The video thus takes on the aesthetics of a first-person video game or of a San Francisco-based round of GeoGuessr,

1 particularly suited to a city that has itself been a pioneer in the development of urban cartographic visualization technologies.

2 While the original narrative can no longer unfold, its path is maintained, especially as the soundtrack of

Vertigo accompanies Chatonsky’s mechanical stroll, ensuring a sense of continuity between the shots.

3 Scottie and Madeleine/Judy (both played by Kim Novak) are however replaced by anonymous passers-by, inadvertently caught by the Street View camera as they drift through the original film’s iconic locations (some places of the 1950s are still recognizable, while others have disappeared).

Although based on a rather simple procedure,

Vertigo@home is emblematic of Chatonsky’s prolific and very diverse artistic practice. First, it is a perfect example of the artist’s post-cinematic works based on strategies of reuse, which he produced in large numbers between 2001 and 2008, and which continue to inform his production today alongside larger-scale projects that extend beyond the strict domain of reuse. Second, this experimentation reflects his sustained interest in reconfigurations that explore increasingly sophisticated technologies of vision and their evolving possibilities. In 2021, Chatonsky produced

Vertigo@home 2.0, which differs significantly from his former reconfiguration despite its nearly identical title. Based on automated image generation, this 2.0 version entirely unfolds as illustrations that result from the AI’s interpretation of a scene-by-scene summary of Hitchcock’s film.

4 This piece is then presented as a one-minute video composed of cryptic, colorful mutated imagery.

From the very beginning, a robotic voice accounts for John Scottie Ferguson’s rooftop chase across San Francisco, then evokes his sudden acrophobia, as well as other key elements of

Vertigo’s original storyline. Each part of this condensed narrative is accompanied by a flow of images that evolve according to their own internal logic, gradually morphing through small visual fragments that coexist in a multi-dimensional space. The result looks like a hybrid patchwork with disfigured faces and distorted patterns. Parts of police cars embedded in a cityscape of rooftops and skyscrapers can be discerned, as well as cables of the Golden Gate Bridge entangled with passers-by, then dissolving into the waters of the Bay (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Elements that may be reminiscent of the trunks of Muir Woods’ redwoods also merge with dark silhouettes, when a spiral staircase appears to draw in mouths and eyes, recalling the spiral motif central to the original plot. Vertigo is recomposed as a succession of interwoven fragments from which key Hitchcockian motifs emerge, as if surfacing from a machinic unconscious that feeds on the virtually infinite reservoir of online imagery.

Completed fourteen years apart,

Vertigo@home and

Vertigo@home 2.0 reflect Chatonsky’s effort to excavate new layers of interpretation of Hitchcock’s film through the prism of non-human perception. While he could have selected any other scenes from cinema history, he seized upon

Vertigo as a recurring test-object—though more as a running joke than a tribute

5—tracing a kind of natural lineage over the years. An overview of this set of reworkings indeed not only offers a global perspective on rapidly evolving visualization technologies but also provides a vision of the expanding digital archive of Hitchcock’s film. Since no work in the history of cinema has generated as much commentary and analysis as

Vertigo, this expansion can be considered part of the film itself, which functions as a fetish or neuralgic object, that inevitably evokes a memory beyond its own boundaries. Hitchcock’s film has also already been the subject of numerous reappropriations within the found footage tradition,

6 which demonstrate that its images resist being fixed within a single experience or stable meaning (

Ravetto-Biagioli and Beugnet 2019, p. 245). Situated within this long tradition of re-readings, Chatonsky’s auto-generated reconfigurations however take

Vertigo to a further stage of transformation, as it reemerges only indirectly, deprived of its own images, through the vast synthesis of an infinity of visual materials.

Before turning to

The Kiss series, forming the central focus of this paper, it is worth considering another of Chatonsky’s early reconfigurations, which further confirms his attempt to reveal latent digital contents of the 1958 feature film. Completed in 2015,

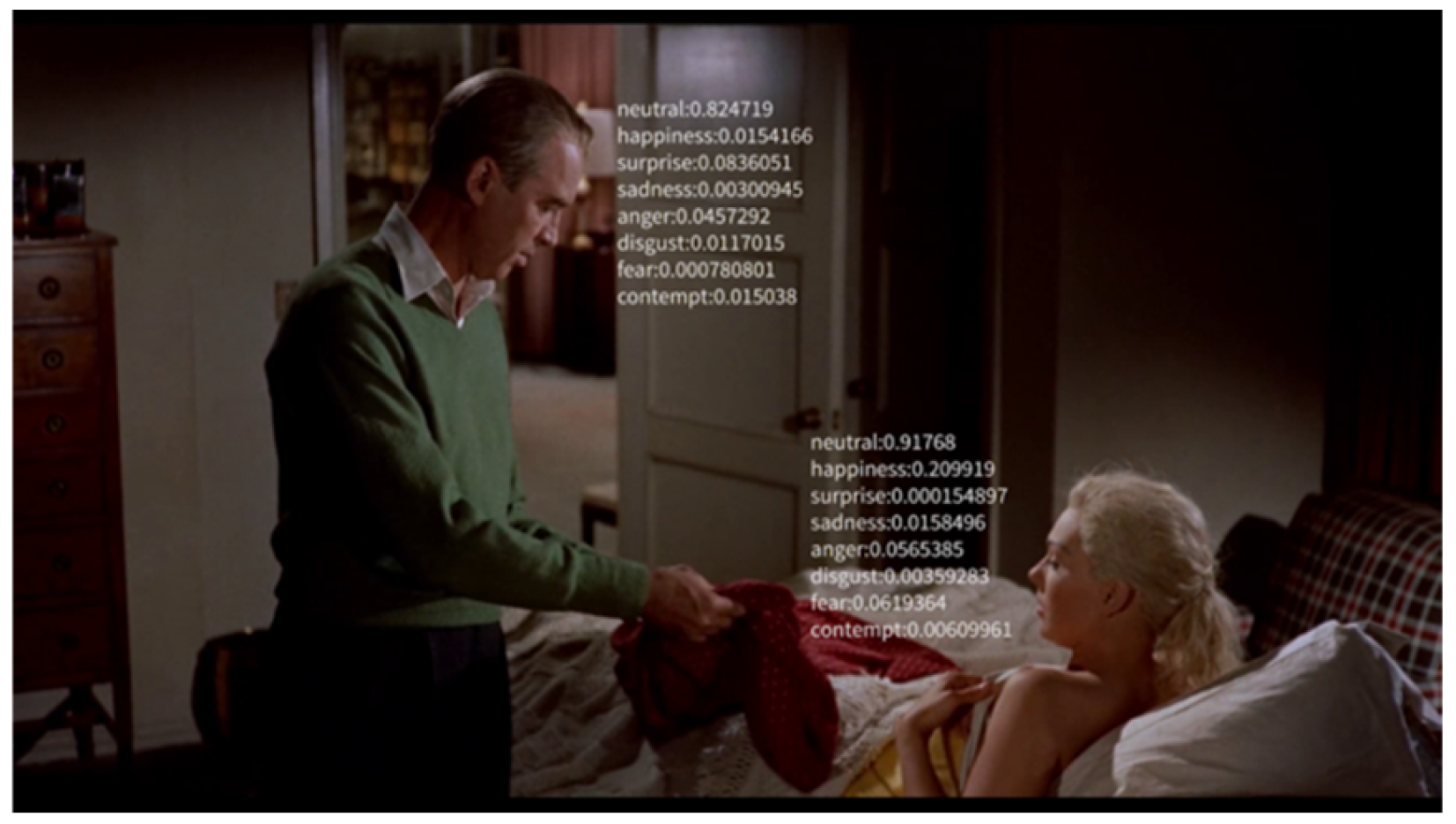

Prediction is presented on the artist’s website as a three-minute video, which shows the scene in which Madeleine/Judy wakes up in Scottie’s apartment after he has rescued her from drowning. The scene is kept in its integrity, but the protagonists are systematically accompanied by six lines of code. Each consists of about ten digits inscribed directly onto the shots, corresponding to different emotional states: neutrality, joy, surprise, sadness, rage and disgust (

Figure 5).

7 When they share the frame, Scottie and Madeleine seem to be conversing in this encrypted language, as a silent dialogue that may either complement or contradict their spoken exchanges, still audible all along (

Figure 6).

Chatonsky had excerpts from

Vertigo read by an IBM software connected to a Watson computer program, originally designed for job interviews and capable of converting human emotions into numerical sequences. The emotional subtitle

8 that results from such a process reveals how the machine detects and interprets feelings, as a logical sequence of numbers, while complicating our own apprehension of the characters’ inner selves. As our gaze shifts back and forth between faces and figures, we may question our own capacity to accurately understand the protagonists or to interpret the information revealed by the machine. However, technological decomposition also fails decipher the emotional enigma of the scene and to fully capture Madeleine/Judy, who resists the “lie detector” logic of facial recognition. The numerical data cannot reveal the double game she plays at this moment (as she pretends to have no memory of the drowning) and throughout the film (the fact that she plays the role of Madeleine).

Rather than offering a helpful deciphering,

Prediction9 then mainly shows the collision between two forms of visions: our organic apprehension of the protagonists and the AI’s interpretation, which tells an alternative story to the original film through an encrypted emotional scenario. Prior to the development of automated image production and six years before

Vertigo@home 2.0,

Prediction gives a visibility to elements contained in the original film (the characters’ emotions), but in a form that can only be exposed thanks to digital technology (their coding or encryption) and that remains beyond the artist’s full anticipation. The short video materializes what could be conceived as

Vertigo’s digital unconscious: elements drawn from the film but detached from the usual human rules that structure the visible.

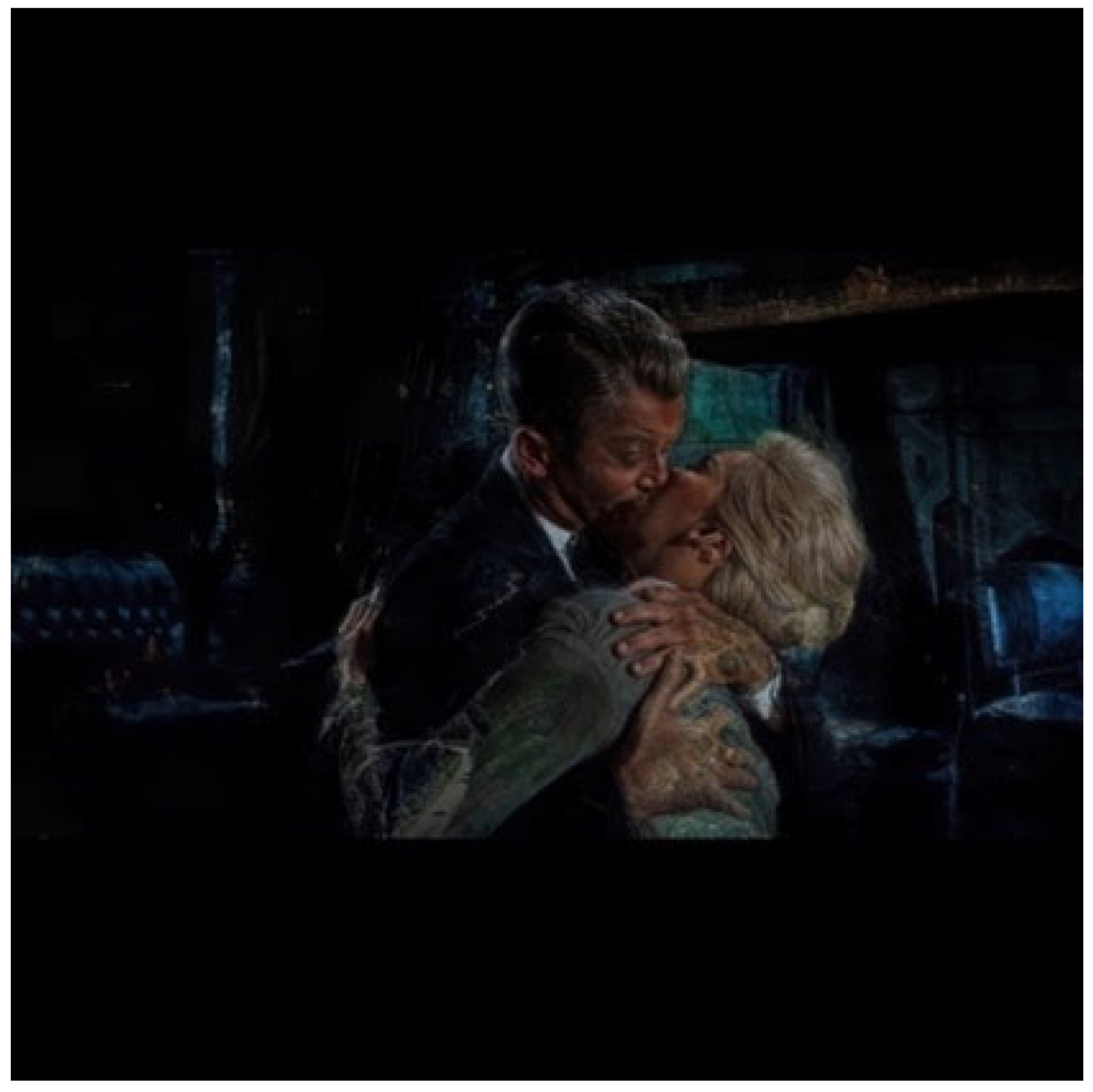

By 2015, the year

Prediction was completed, and as computational modes of visual production advanced, Chatonsky began to narrow his focus to one particular scene from Hitchcock’s film. He indeed directed his attention to the kiss between Kim Novak and James Stewart in the Empire Hotel, corresponding to the last union between the two protagonists, although it does not occur at the very end of the narrative (13 min before the finale). This scene, which portrays the return of the beloved Madeleine via Judy’s imposed transformation, apparently provides particularly fruitful material for manipulation. The singular distortion of space and time it establishes (shifting from the present to a resurrected past), its emblematic green neon light and the camera’s 360-degree movement around the entwined bodies endow the scene with a particular density. The swirling effect that characterizes it also creates a paradigmatic space of fantasy and drift, encouraging the emergence of alternative readings.

10The Kiss, which currently comprises seven pieces, has received little academic attention so far. The objective is thus to examine the different ways in which the sequence’s latent potentials are explored via 3D-transcriptions, video, and still image compositions, primarily using AI-based image-generation software. Through the unfamiliar monstrous figures and hallucinatory motifs that result from digital visualizations,

11 Vertigo is reconstructed as a memory that can indefinitely be reinterpreted and opens up to new aesthetic horizons.

12 Chatonsky’s incursion into the film’s underlying dimensions seems facilitated by the fact that

Vertigo visibly lends itself to the science of interpreting the unconscious, as few other films do. Since the narrative is shaped around Scottie’s fascinations and obsessions, as well as the multiple manifestations of fantasy, the unconscious indeed constitutes a thematic unit in the film, calling for tentative interpretations and visualizations of what cannot be expressed. The exploration of these potential unarticulated elements thus leads to the apparition of unexpected sporadic arrangements that defy human logic, whose irregularities underscore the specificity of machine imagination. By machine imagination, I refer, following Deleuze and Guattari (

Deleuze and Guattari 1972;

Guattari 1979), to a productive machine that organizes flows of images, desire or bodies, without any predetermined configuration, but rather following an open and “unconscious” rhythm of circulation. Regarding

The Kiss, the series indeed originates from a machinic system that connects and condenses, from Hitchcock’s

Vertigo, a heterogeneous flow of visual material inaccessible to the human perception, according to an evolving and unintelligible logic. It thus digitally opens access to the unthought dimensions of existing images, which may be understood as the film’s digital unconscious.

2. Vertigo’s Latent Volumetric Forms

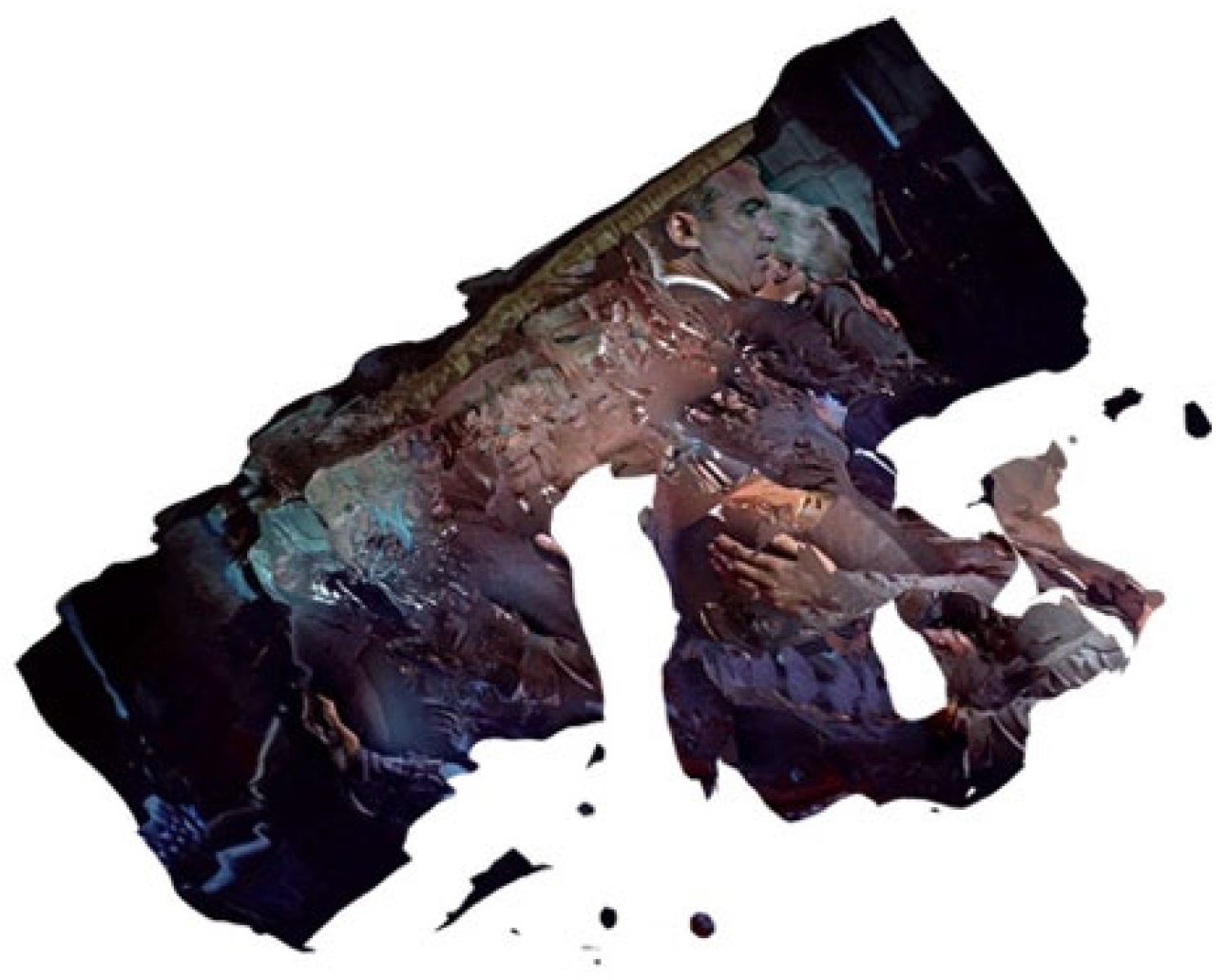

Chatonsky’s first reconfiguration of the kiss differs from the rest of the series.

The Kiss 1 takes the form of a small sculpture (rather than a short video or a set of still images) created using a photogrammetry software capable of reconstructing a three-dimensional model from multiple photographic images. The artist first generated an oblong structure from the original

Vertigo excerpt, giving an overview of the main volumes that make up the scene, primarily the space occupied by bodies and objects in the setting. The resulting visual reveals the spatial positions of the protagonists, as they escape the chronological evolution of the sequence and are rather deployed into space.

13 This temporary stage takes on the appearance of a topographical map of the lovers’ embrace, that remains quite difficult for the human eye to decipher. While the bodies melt into one another, Kim Novak’s blond bun or James Stewart’s distracted eye stand out at certain points of the dark-colored mass, suggesting the ongoing process of spatial unfolding. Chatonsky then simplified the resulting diagram to obtain a multi-sided volume, more suitable for the 3D-transcription he had in mind (

Figure 7). Through 3D printing, he converted the kissing scene into a small abstract sculpture about thirty centimeters high, 15 cm wide and 10 cm deep, that no longer retains any figurative remnant of the original scene (

Figure 8).

Breaking from the indexicality of

Vertigo’s cinematographic image,

The Kiss 1 visualizes a digital reinterpretation of the appropriated excerpt, resulting in what can be considered as a paradigmatic post-cinematographic object, an object created beyond the specificities of traditional cinema and that rather evokes forms of images born with the digital age. Despite being entirely the product of some processes of coding and synthesis, it takes on the appearance of an organic spiral form wrapped around itself, reminiscent of a wave or a drape, distantly echoing the entangled bodies of the scene. The structure, then, not only materializes the trace left in our memory by the spiral effect but also grants a singular presence to Madeleine’s ghost, physically fusing with the body of the film, while symbolically becoming within reach or almost tangible. The white surface of the structure, which could evoke a plaster cast, also amplifies the impression of revealing the constitutive evanescence of the characters, as it can be perceived as their negative imprint. Through this multi-step transposition, Chatonsky succeeds in capturing and even amplifying the flow at the heart of the original scene, giving both a sense of Scottie and Judy’s movement and of time winding back on itself. As this flow is originally difficult to fully perceive while the film unfolds, it is here clearly “incorporated and materialized in the very structure of the generated 3D model.”

14 This discorrelated (

Denson 2020) version of the sequence does not conform to human models of vision anymore, but to purely digital protocols and extended modes of machinic visualization.

Irregularities, small peaks and reliefs can also be seen on the apparently smooth sculpture. Although they seem disconnected from the original work, these elements still correspond to different aspects of the sequence, which the machine remains able to link to specific elements of the mise-en-scene by reversing the creative process, though entirely opaque to the viewer. Chatonsky’s post-cinematographic experiments then uncover the digital potentials of Vertigo and give shape to its spectral figures, as gradually confirmed in subsequent works, from The Kiss 2 to The Kiss 7, which continue to regenerate key motifs of this spiral scene, its setting and its characters.

3. Technological Hallucinations

It took Chatonsky several years to complete his second reworking of the kiss scene, this time using AI-based text-to-image generators, which he personally adapted and refined. Such systems operate through auto-implemented algorithms that convert linguistic prompts into synthetic images, resulting from the vast datasets used to train the software. In 2022, Chatonsky shared three different versions online produced through this process:

The Kiss 2,

3 and

4, all based on comparable variations using prompts derived from the

Vertigo script yet responding to specific sets of generative rules. Since prompts produce different results even when starting from a similar base, the outcome always constitutes a unique exploration of the latent space, which brings forth one of its possible images, along with the points and trajectories within it.

15Chatonsky’s first text-to-image reworking of Scottie and Madeleine’s union,

The Kiss 2, assembles surreal and grotesque images that flow smoothly into one another. The prompt at the source of the recomposition—about which Chatonsky shares little information—probably commanded, among other things, the central presence of purple

16 and the appearance of elements specific to the film within the kiss scene itself. Disfigured faces and melting hands materialize from ruins and clouds of purple smoke (

Figure 9), dissolving into strange modulations, while Judy and Scottie emerge in fluid metamorphoses, freed from the stability inherent to the human body. Some parts remain vaguely reminiscent of elements we might associate with the original film, as a trunk that rises in front of an unreal city, evocative of Muir Woods, or like parts of a stone wall, reminding San Francisco Mission Dolores. These fragments are in fact the result of a synthetic actualization of the vast archive of images circulating online, generated and synthesized by the machine from the protagonists’ final embrace.

As the artist points out regarding the first part of his series, the aesthetic of this one-minute video, designed to be projected as a loop, is highly representative of what experimenters produced with text-to-image generators around 2020–2021. The specific distortions and recurring motifs such as hands or smoke, which could evoke the sensation of an LSD trip, indeed appear to be temporal indicators of this brief period. This reconfiguration consequently persists as the trace of a machinic unconscious deeply inscribed in its moment of creation, which belongs less to the original Vertigo than to the tools that revisit it, themselves rapidly surpassed by technical evolutions.

The third piece of the series also presents a 3-min continuously morphing assemblage, whose aesthetic remains quite close to that of the previous essay. This time, Chatonsky injected the complete synopsis of

Vertigo into the embrace scene (slightly extended as it begins with Scottie’s entrance into the Empire room).

The Kiss 3 ultimately contains the entire plot of Hitchcock’s film in condensed form and “metabolize[s] the whole film”, which is “automatically reinterpreted from a latent space of possibilities.”

17 In other words, the kiss is reconstituted from a virtual open space fueled by Internet databases, while retaining the visual framework of the original scene. The condensation or compression effect inherent to this third composition also lies at the very core of

4 Vertigo, a found footage piece created by Les Leveque some twenty years earlier, in 2000. Far from Chatonsky’s complex digital processes, this short film is based on the repetition, four times, of each shot from Hitchcock’s

Vertigo, rotated through every possible orientation, to create the illusion of a circular motion on screen. Leveque interwove these four versions of the same shot and sequenced them at an extremely rapid pace, condensing the entire film into just under ten minutes.

4 Vertigo thus contains the whole of the original film, not through the software reinterpretation but through reorientation and compression, blurring visibility while preserving the original framing and color palette. Here,

Vertigo reemerges as a kind of psychedelic flash, where cinematic elements and faces collide with one another.

By contrast, in Chatonsky’s

The Kiss 3, heterogeneous fragments detached from the original narrative not only collide but also dissolve. Within its new digital environment, a building that evokes the bell tower of San Juan Bautista meets small nuns in purple veils and aged figures. The mineral, vegetal, and animal intermingle, as characters change into dogs or stones (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). As distinctions between forms of being cease to operate, the music helps vaguely to situate us within the chronology of the source film. At the intersection of machinic automation and artistic reappropriation, and as initiated with

The Kiss 2, the indexical images of

Vertigo shift toward alternate realities, whose constant movement illustrates both the perpetual incompleteness of artificial memory and the unlimited possibilities of reconfiguration, once again revealing the film’s inaccessible unconscious, produced and made available by the machine.

While such distortions function as a marker of this specific moment in image generation, Chatonsky’s fourth experiment marks a clear aesthetic shift, despite having been produced the very same year. This time, he entered the script into Stable Diffusion, an AI system capable of generating images from textual descriptions, in order to obtain a succession of still images (shifting his focus away from the kiss scene to consider the film in its entirety). His aim was for a new film to take shape through a completely new set of images, as if it were an alternative version of reality, to borrow Chatonsky’s words, “sometimes close to its textual description, sometimes further away.”

18 As he did not retain any visual elements from the original,

The Kiss 4 gives the impression that the moving images of

Vertigo have been transposed to a silent series of square-format paintings, accompanied by subtitles that seem to echo the prompts behind the images, thus revealing part of the textual material from which the images are generated.

19All the stills in the series are marked with a strange déjà-vu quality, having no trace in any existing reality but being produced from the accumulated data of humanity’s collective heritage. The effect of resemblance produced by

The Kiss 4 arises mainly from the bourgeois interiors typical of the 1950s, which constitute the main visual frame, as well as from West Coast landscapes, which are easy to situate within a familiar space-time.

Vertigo is also being dreamed up within aesthetic frameworks and periods that are foreign to him, as some scenes evoke, for example, the style of certain canvases by René Magritte, presenting simplified figures whose silhouettes stand out against an azure sky (

Figure 12). This rapprochement between Hitchcock’s films and the pictorial tradition is central in the work of French artist Laurent Fiévet, particularly in his 2014 video diptych

Carlotta’s Way and

Returning Carlotta’s Way. In these works, Fiévet superimposes slowed-down excerpts from

Vertigo onto fragments from Diego Velázquez’s

Las Meninas (1656). The resulting palimpsest invites a fresh reading of the motifs present in each work and highlights multiple instances of accidental correspondences, giving the impression that certain gestures and elements echo one another, such as the golden curls of Velázquez’s young girls intertwining with Kim Novak’s hair. In this way, a cinematic effect permeates the painter’s work, while the suspended shots from

Vertigo are enriched, appearing to absorb

Las Meninas.

As for

The Kiss 4, it does not absorb a single painting in particular, but rather a whole series of pictorial traditions that cannot be specifically identified, and “that profoundly alters its temporal status” (

Somaini 2023, p. 94), while remaining connected to the visual style of the source film. We are indeed facing certain aspects of the 1950s reimagined from a contemporary perspective by AI, infused with aesthetic models that came after the production of

Vertigo, all filtered through the lens of the machine. Familiar faces also seem to have continued to evolve or age since the moment of their original incarnation, and now reappear subtly altered or seemingly in disguise as in a Proustian “Bal des têtes” (

Proust [1927] 1990). Moreover, as the duration of

The Kiss 4 may vary depending on the presentation format (as it can be presented as a two-minute online video, or be displayed as loops of varying lengths in exhibition spaces), it appears less as a finished piece and more as an open process, in the fantasy of an infinite, evolving memory.

Despite the presence of clichés (the characters adopt conventional postures, the men have slicked-back hair and women tightly wound chignons) the short series of still images progressively reveals the possibility of challenging Hitchcock’s archetypes. Without knowing to what extent the artist intentionally guided the prompts to work against stereotypical patterns often reproduced by generative images, a vast number of generated versions of Madeleines appear in all skin tones and hair colors, echoing Judy’s original transformation (

Figure 13). We are facing stills that do not fully escape dominant logics of representation but at least disorient them by disrupting the iconic Hitchcockian blonde. With this specific reworking, Chatonsky explores the marginal zones of the latent space, where new forms of visibility for minoritized existences can be invented. Indeed, racialized characters become central figures within the recomposed images, occupying space and moving through an environment that remains heavily codified. In doing so, they emerge as agents of a renewed history of Hollywood classicism, no longer shaped exclusively around the white standard and the implicit norms that dominated classical Hollywood production (whiteness as the ideal of beauty and the stereotyping of racial minorities), but rather opening the narrative to all. While AI is itself shaped by aesthetic and political norms that perpetuate canonical models (since it feeds on them),

The Kiss 4 creates space for identities that are often erased or misrepresented in mainstream imagery.

This fourth work in Chatonsky’s series thus resonates even more strongly with the central themes of Vertigo: the construction of identity and the adaptability of (feminine) bodies. Above all, the unfolding of Madeleine across a wide range of identities echoes the film’s unconscious: the heroine does not merely duplicate herself but multiplies without apparent limit, no longer confined to a single, fixed standard of beauty but successively embodying multiple ideals. In doing so, her haunting power is intensified, as a materialization of the protagonist’s fantasies. While parts of Vertigo’s aesthetic unconscious continue to be revealed, a more political use of text-to-image generators opens up, showing the potential reinterpretation and reactivation of the film’s memory beyond the norms that shape both the dominant Hollywood language and that of auto-generated images. The Kiss 4 thereby critically reactivates our involuntary memory of Vertigo (what persists in our mind and escapes the control of the original director), while creating alternative ways of remembering and reimagining its legacy.

4. Aging and Expanding

The Kiss 5 visually resembles the second and third reconfigurations but remains marked by the shift operated in

The Kiss 4, as it also underlines the potential aging or evolution of the characters. Right after the opening of the 5-min video, Scottie indeed appears with a thick gray mustache, Madeleine as a glowing green specter, or with hardened features that accentuate the potential passage of time since the first occurrence of

Vertigo (

Figure 14 and

Figure 15).

This fifth opus is also marked by its exploratory dimension of a partly re-created tangible space-time. New movements are indeed introduced, as the gaze shaped by the AI’s reading sweeps across a room of altered dimensions or lingers on details such as green pillows, absent from the original version. As the characters blend into one another, their gestures are elongated, the music is slowed down, creating a moment of suspension within the spiral movement. Coupled with the reinvention of the spatio-temporal thread of this scene, this unexpected slowness underscores Chatonsky’s attempt to stop and complete the existing images in other directions. The emergence of a quasi-narrative suggests, following the same movement, the possibility of taming the film’s unconscious, to give it a logical form, the original moment from Vertigo remaining fully present within new locations that extend just beyond the limits of the original set. The visual artist Nicolas Provost also explored the intertwining of Scottie and Judy’s bodies in his 2007 short film Gravity. He, too, seemed intent on extending their embrace beyond its original frame, blending the two characters with other iconic couples from film history, such as the lovers in Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour (1959), all spinning together. By rapidly sequencing these different shots, Provost does not extend the kiss scene spatially, but deploys or diffracts it across the history of cinema.

While Provost and Chatonsky’s works resonate with each other, it is precisely the expansion of

Vertigo’s geographical boundaries that characterizes

The Kiss 6, the first production of a unique still in his entire series. In this second 2024 restructuration, Chatonsky extracted an image from the kissing scene using an open-source software based on Stable Diffusion XL, enabling the editor to increase the definition of the original shot and to create unexpected details within the initial image. The machine produces in this way an artificial pareidolia, projecting new visual fragments onto the embrace according to the shapes and movements it identifies within it. Portions of the embrace are perceived as winding roads, the black background as a vast city at night, and the original image as a whole becomes invaded with fragments of dark landscapes (

Figure 16).

At first sight, the kiss unfolds as a striking quasi-dystopian vision of a futuristic city, traversed by cables and neon. The famous coastal Highway 1, for instance, is part of a petrified version of Scottie and Judy’s textured bodies, and the hotel room has morphed into a composite nocturnal setting. An aerial view of a San Francisco neighborhood collides with the recognizable green light, giving shape to a distorted dream projected directly onto the embrace. The new spiral of still images illustrates both the data set of images collected online and the possible distorted evolutions of the spectators’ memory, along with their potentially infinite mental associations. The “palette” of transformations then appears virtually infinite, each singular image capable of being transformed into a generative resource by the latent space, potentially containing a multiplicity of other images or possible worlds.

In the most recent iteration in the series,

The Kiss 7, we can still have a glimpse of the embrace amid textures of hair, silk, purple or gray smoke, lush green forests and animal parts. Recalling the psychedelic hallucinations of the earlier works, strange faces are intertwined with unexpected details: hanging pendulums, veiled women, birds and small witches (

Figure 17). If they are likely guided by the prompt, they produce the effect of disparate elements emerging from the machine’s dream as it re-visualizes the original scene, especially as the music, distorted and slowed down, no longer helps to find the original path.

The Kiss 7 gives the impression of overflowing memory that exceeds both the initial scene and all previous experiments, a sense that will likely be confirmed by the forthcoming version that may appear online.

5. Conclusions

From a graspable piece (

The Kiss 1) to an anachronistic pictorial transcription (

The Kiss 4), and across a series of hallucinatory trips (

The Kiss 2,

3 and

7), Chatonsky reveals the infinite depth and layering of

Vertigo, as well as the spaces that can expand beyond its foundational base (

The Kiss 5 and

6). Image-generation software gives a visibility to the afterlife of Hitchcock’s film—a potentially aging production—in the digital age, transforming its iconic kiss scene into an inexhaustible reservoir of latent forms to be actualized (even if an entire dimension of visual actualizations is left in the inscrutable regions of the latent space). While the seven versions of

The Kiss illustrate the way contemporary technologies reshape our relationship to familiar images of the past, as if they could now endlessly adapt and transform, an inevitable sense of strangeness emerges. As Kriss Ravetto observes (

Ravetto-Biagioli 2019), this digital uncanny effect is no longer

unheimlich in Freud’s sense, but rather arises from the machine’s capacity to anticipate, produce and shape our future visualities, almost independently of human intent. Within the emerging digital archive to which

The Kiss series contributes, traces of our iconographies persist, yet they are marked by a form of machinic uncanniness that disrupts any full understanding or apprehension of their mode of operation, even though it ultimately originates in what we ourselves have produced. By reinterpreting an emblem of cinema history through these uncanny nonhuman apparatuses, Chatonsky’s reworking exceeds, in many ways, traditional logics of reuse, not through the direct reappropriation of images but through the exhibition of their digital synthesis. Far from replacing conventional found footage practices, this logic nevertheless encapsulates or distills in its own way a broader essence of

Vertigo, which aligns both with the impressions the film has left on us and with what the software retains through processes that transcend the boundaries of cinema and of reuse itself. Digital uncanny

Vertigo thus emerges, which machinically illuminates our own reception of the original film.

In this evolving series, Chatonsky explores the digital dimension of the film’s unconscious to capture the materiality of the embrace, exhaust its possible forms, probe its underlying structures and semantic density, and even reveal the potential political ferment of its staging, particularly by unsettling the stereotypes of the Hitchcockian imaginary. Primarily, the artist engages with the latent digital substance of the original work, understood as everything the initial creation could neither anticipate nor contain, and all that escapes the rationality or control of its author. In this sense,

The Kiss gives form to a digital extension of the “optical unconscious” of

Vertigo’s images, in a way reminiscent of what

Rosalind Kraus (

1993), following Walter Benjamin, described as the repressed forces that traverse canonical images and that are brought to light by experimental practices. In Chatonsky’s series, the machine’s automatism indeed disrupts pure visibility, allowing a set of uncontrolled visions to resurface from within the material substrate, which are translated into the formless substance produced by the software itself. From this substance, Chatonsky renews the spectacle of the protagonists’ union, generating a new form of fascination by bringing to the surface, through the machine, all that this emblematic cinematic kiss can still express.

By exploring these unrealized potentials,

The Kiss also encourages us to trace parallel histories of cinema, which acknowledge both the original film’s re-emergence as an infinite visual memory and the aesthetic imprint of all these technological innovations. The spiral of possibilities that opens up from the source-scene finally comes to reflect the looping logic of automated image-generation systems, within which our visual culture is gradually becoming a continuous feedback loop (

Somaini 2023, p. 75). These systems repeatedly return to the same set of images, moving further away from it while generating new ones. In the age of machine imagination,

Vertigo seems caught in its own vertigo, wrapping itself within its expanded memory.