Abstract

This essay proposes operative creativity as a conceptual and artistic response to the shifting roles of images in the age of algorithmic perception. Departing from Harun Farocki’s seminal artwork Eye/Machine, which first introduced the operative image as functioning not to represent but to activate within machinic processes, it traces the transformation of images from representational devices to machinic agents embedded in systems of simulation and realization. Although operative images were initially engineered for strictly technological functions, they have, from their inception, been subject to repurposing for human perception and interpretation. Drawing on literature theorizing the redirection of operative images within military, computational, and epistemic domains, the essay does not attempt a comprehensive survey. Instead, it opens a conceptual aperture within the framework, expanding it to illuminate the secondary redeployment of operative images in contemporary visual culture. Concluding with the artwork Terms and Conditions, co-created by Ruti Sela and the author, it examines how artistic gestures might neutralize the weaponized gaze, offering a mode of operative creativity that troubles machinic vision and reclaims a space for human opacity.

1. Introduction

The concept of “operative image” has been widely acknowledged and integrated into the discourses of art, visual culture, media theory, and digital media as a rhetorical and analytical construct for articulating a distinct mode of representation. The definition was first introduced in 2001 through an experimental art piece called Eye/Machine, created by German filmmaker Harun Farocki. This installation consists of three films, where Farocki examined the transformation of the status of images as they transition into machine vision representation, particularly in military, industrial, and other contexts (2001–2003) (Farocki 2000).

In one of the installation’s most emblematic sequences, Farocki analyzes footage captured by a camera mounted on a guided munition commonly referred to as a “smart bomb.” It is within this context that he introduces the term operative image: an image that is not produced “to entertain nor inform” but rather functions as an active component within a technological operation. These are not images that merely represent an object; they are images that perform, embedded in and instrumental to the execution of a task.1

From its inception, the association between operative images and the representation of information has been understood as inherently complex, prompting a departure from purely aesthetic considerations rooted in mimetic traditions. Instead, critical attention has shifted toward a more nuanced interrogation of the intersections between the technological and the visual, with a particular emphasis on the logics of machine vision and its operative functions. When anthropocentric frameworks dominated visual assessment, operative images were often dismissed as lacking in visual richness, relegated to a category “the images are not interesting to look at as images.”2 Artist Trevor Paglen aptly described them as images “made by machines for other machines.” (Paglen 2016). Media theorist Jussi Parikka argues that such images hold intrinsic operational agency, also playing a pivotal role in structuring the visual regimes of contemporary culture. He adds that it is through their varied instantiations in cinema, the plastic arts, digital media, and scientific visualization that the material infrastructures of technical images, where data, perception, and machinic operations converge can most effectively be discerned (Paglen 2016, pp. 70, 90, 167, 200).

Indeed, recent literature clearly emphasizes the crucial role of operative images in comprehending the visual world, particularly in the rapidly evolving domain of artificial intelligence. Within the subfield of machine learning, operative images are not merely passive inputs, but constitute an active epistemic infrastructure through which algorithmic systems are trained to infer, classify, and decide, often without recourse to pre-programmed rule sets. Their significance lies not only in their technical utility but in their role as mediating agents in a paradigm shift from representational logic to computational vision, marking a profound transformation in how machines register and act upon the world. Operative images thus serve as a vital conduit for exploring the zones of overlap between human and machine vision, while also illuminating the limits of what machines can log or render perceptible. As German film historian Thomas Elsaesser noted, operative images maintain a crucial function as mediating instruments, wherein “operational images correspond [to] operating instructions for life.” (Parikka 2023, pp. 15, 95). Nevertheless, engaging critically with this category of imagery necessitates a shift beyond anthropocentric frameworks that privilege the human visual field as the central axis of analysis. Instead, it calls for attunement to an emerging paradigm, what media theorist Joanna Zylinska describes as a condition in which “photography is becoming more and more detached from human agency and human vision and the creation of images by machines, for machines.” This turn toward nonhuman imaging systems compels us to reconsider the epistemic and ontological stakes of visuality in the age of algorithmic perception (Parikka 2023, p. 18; Elsaesser 2017, p. 223).

Given the expansive scope of discourse surrounding operative images, this essay does not seek to provide an exhaustive account. Rather, it aims to open a conceptual aperture into contemporary debates on images that no longer merely represent the world but actively participate in its operationalization. For this purpose, it foregrounds key developments that have established the operative image as central to the nexus of technological simulation and machinic realization. While initially engineered to serve technological ends, such images have, from their very inception, been subject to repurposing for human perception and interpretation. Tracing these trajectories situates the present intervention within a broader genealogy of recontextualizations, in which images oscillate between technical function and cultural meaning.

Against this backdrop, the essay advances its distinct contribution: the proposal of operative creativity as a conceptual extension. This notion illuminates the secondary redeployment of operative images, originally designed as active components within technological systems, through creative intervention. Such interventions may range widely, from propagandistic mobilization to critical resistance, yet in every case, they mark the operative image’s repurposing for renewed encounter within a human perceptual field.

Such redeployments aimed at human viewers also reopen the question of definition, where that operative image seems to activate the very boundaries that claim stability. As is often the case when theoretical language attempts to grasp a phenomenon that exceeds its own discursive limits, the task of defining operative images remains fraught with ambiguity. This difficulty is heightened by rapidly shifting technological environments, which continuously reshape the conditions under which such images emerge and function. In his critical analysis of Harun Farocki’s work and the interpretive arc surrounding the term, media theorist Volker Pantenburg observes that while the operative image forms part of an apparatus of activation, “there is no such thing as the operative image” in the singular. Rather, it should be understood as a “constellation of heterogeneous ideas.” Pantenburg proposes that varying degrees of operativity exist. In its most restricted sense, operative imagery, particularly algorithmically generated data visualizations or pattern-recognition processes devoid of pictorial output, may be considered a “pure form of functional data display,” an “embodiment of computational procedure.” (Zylinska 2017, p. 2; Pantenburg 2016). In such cases, even the term image may be redundant. More expansive interpretations, however, encompass a diverse range of media forms, electronic, cinematic, or otherwise, that serve to support or initiate operations, whether military, mechanical, or interpersonal. These images not only mediate actions but may themselves possess the capacity to activate them. As varied as the definitions of operative images may be, so too are the existing and potential forms of their repurposing, underscoring the breadth of possibilities that animate their ongoing theoretical and practical reconfiguration. While human role is receding in machinic image cultures, accounting for repurposing becomes vital for understanding how such images still carry and reorient embedded values.

This essay follows a trajectory that opens with the conceptual emergence of the term in experimental art and concludes with a contemporary artistic intervention, where both reclaim the operative image as a creative and critical tool. This structure is intended to illuminate how operative images, often generated through cameras, sensors, and algorithmic systems, are mobilized toward both instrumental and symbolic ends, directed not only at machinic environments, but also toward human perception. At stake is the capacity of art to both expose and potentially transform the logics of activation embedded within such images.

Serving as the point of departure, the chapter Activating the Definition of the Term in Language introduces the concept of the operative image as it was first articulated in an experimental artwork from the early twenty-first century. It traces the historical and theoretical foundations of the term within visual culture, highlighting the repurposing of operative images in military contexts, especially during the Gulf War. This section situates the term within a broader genealogy of visual regimes that shift the image from mimetic representation to systemic activation, marking a threshold where simulation begins to replace referentiality.

The second chapter, Technical Images: From Image to Data, expands the discussion by examining algorithmic and machinic forms of operative imagery, also referred to as invisual, unrepresentable to the human eye, and inward-facing rather than outwardly displayed. This chapter charts the evolution of these images beyond their military genealogy, situating them within contemporary practices of data visualization, sensing technologies, and computational aesthetics. It explores the interplay between operative image design and shifting configurations of information and technology. The operative image, in these contexts, is understood as a prototype of a “nonhuman image”, a visual element generated, processed, and sometimes interpreted autonomously. While human agency remains involved in their conceptualization and deployment, these images are shaped by algorithmic protocols that determine not only the devices and processes of their creation but also our perceptual and interpretive engagement with them. When mediated through designated human-facing interfaces, the operative image ceases to be a capture of a past event and becomes instead a speculative configuration of a potential present, actively recalibrated for perceptual engagement. The final chapter, The Nutrulised Operative Image, returns to artistic practice to explore how art might redeploy operative images to resist, subvert, or rewire the machinic logics in which they are imbricated. While the term was originally theorized through Farocki’s critical engagement with images that masked the violences of war under the guise of machinic neutrality, this concluding section focuses on a contemporary work by artists Ruti Sela and Maayan Amir. Their intervention attempts to neutralize the operative logics embedded in visual technologies that aid weaponized systems. In doing so, the work proposes a form of operative creativity, one that does not merely reflect the workings of simulation and realization but actively intervenes in their conditions of possibility. This final discussion opens a speculative space to reflect on the entanglement of the human and the nonhuman in systems of perception, control, and creative production.

The motivation for this essay lies in the increasing relevance of operative images across fields as varied as warfare, logistics, design, and cultural production, particularly under the accelerating influence of artificial intelligence. As these images become more pervasive, complex, and invisible to untrained observers, their expanding repurposing for diverse human-oriented interactions grows in parallel. Within this evolving landscape, the role of art and theory in making them intelligible, and in creatively engaging their logics, becomes all the more urgent. Operative creativity, then, names not only a condition of contemporary art, but also a demand placed upon it: to navigate, decode, and reimagine the thresholds where simulation meets realization, and where images cease to represent and begin to act.

This endeavor is motivated by a growing need to approach operative images through a creative lens, one that can unpack their epistemological, aesthetic, and political implications beyond instrumental logics. As this mode of representation has sparked lively cross-disciplinary debates in recent decades, rethinking it from within the domain of artistic practice becomes increasingly vital. With operative images continuing to permeate contemporary culture and becoming ever more sophisticated in the age of artificial intelligence and the rise of generative image production, engaging them creatively offers a critical pathway for shaping our understanding of visuality, agency, and mediation today.

2. Activating the Definition of the Term in Language

In a 2004 article, Harun Farocki introduced the key aspect of the term “operative images.” The article began with an examination of two image sequences consisting of footage captured by a camera mounted on a missile during its trajectory to intercept targets. These images were disseminated to the media by coalition forces during the Gulf War in 1991. According to Farocki, the type of images that make up these traces represented a novel phenomenon that had become known only a decade earlier, in the 1980s, coinciding with the emergence of cruise missiles (Farocki 2004, p. 13). To uncover the unique perspective defining the visual field of operative images, Farocki delved into a historical precedent predating this technology, referencing a concept from early 20th-century American cinema termed “Phantom Shots.” (Farocki 2004, p. 13). This concept denoted cinematic shots taken from vantage points inaccessible to human photographers and cameramen, such as capturing scenes from the bottom of a moving train. The development of weapon technologies capable of generating visual output without human presence not only expanded the range of observation points on the battlefield but rather, as Farocki maintains, laid the foundation for the rise of a new culture of the representation of the battlefield. During the transition to the representation of the war through operative images, the possibility of presenting the battlefield as a sort of ghostly site devoid of human presence was expanded (Farocki 2004, p. 15). As suggested by the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, who analyzed television broadcasts of this conflict, this visual transformation even allowed for the reality of the war to be negated, rendering it a “Nowar” through visual means (Baudrillard 1995, p. 28).

Apart from the aforementioned visual aspect, which puts emphasis on what has become a kind of hidden, Farocki’s principled criticism revolves around how the reutilization of operative images facilitates the fusion between warfare tactics and war reporting tactics. 17 (Farocki 2004, p. 15). This notion aligns with the writings of theorist Judith Butler, who contends that a human spectator, in witnessing the visual output produced by the bomb is, in essence, incorporated into the “extended apparatus of the bomb itself.”3 Merely viewing these images implicates the viewer in a reenactment of the war. The ethical implications of this phenomenon were also raised by Farocki, drawing on Paul Virilio’s diagnosis that such repurposing of operative images turns their force back upon the spectator, placing the viewer not merely as a detached onlooker but as a target, caught within the very field of control and violence the images serve (Stahl 2018, p. 6). This process has been further accelerated and expanded due to significant advancements in target interception technologies in the latter decades of this century. In his book Through the Crosshairs: War, Visual Culture, and the Weaponized Gaze, media researcher Roger Stahl argues weapon technologies now function as communication channels, channeling war observation directly to citizens through the lens. The fusion between the eye and the weapon is complete, and their functions are inseparable (Stahl 2018, p. 6). As a result, what was once considered the “civilian eye,” reliant on third-party accounts of the battlefield, has now become a “first-person witness” and can be seen as an extension of the weapon itself (Der Derian 2000, p. 772).

The extensive theoretical discourse surrounding operative images has been developed in recent decades. It discusses their dual use as tools of war for directing attacks and as instruments designed to shape public perception. The era of the emergence of a new operational aesthetic is characterized by the visual portrayal of “bloodless, humanitarian, and hygienic wars.” (Virilio 1989, p. 16).

Over the years, the separation of war culture from direct battlefield view has evolved, with representational technologies transforming the battlefield into a cinematic “sight” since the mid-20th century. However, in the 1990s, the abundance and prosperity of the production means of operative images and the added value they presented, propelled the rise of a logic of “clean war.” (Baudrillard 1995, pp. 3, 7,13, 40, 55, 56, 62; Parikka 2023, p. 23).

These images became instrumental in assimilating military ideologies among civilians, often with the backing of Army public relations specialists’ efforts, including support for Hollywood film productions that included the use of this type of imagery.4 Stahl further contends that modern warfare, employing advanced weaponry, represents the prevailing Western perspective on conflicts today (Stahl 2018, p. 4). Thus, operative images, originally “supposed to replace the work of the human eye,” have become a critical component of the visual narratives through which military activities are conveyed in the media (Farocki 2004, p. 17). While much attention has been given to images that guide weapon systems and simultaneously mediate warfare for human observers, effectively shifting the target audience from machine to human, Farocki insists that researchers must not lose sight of the image’s original addressee: the weapon machine itself. He issues a cautionary reminder that beyond the visible realm, operative images embody an “unconscious visible.” (Farocki 2004, p. 18). Additionally, Farocki speculates that the war between machines will likely persist long after humanity’s existence, underscoring that operative images serve as a juncture between human and machine perception, and their future destination is actually also beyond humanity itself (Farocki 2004, p. 15).

Thus, if the creative repurposing of operative images in war campaign in the media so far sustains a proximity to their original deployment, yet as Farocki reminds us, this continuity also entails an awareness of the irreducible gap between their machinic function and their human reception.

3. Technical Images: From Image to Data

Situated at the forefront of critical theory, operative images emerged in military contexts whose extensive impact, both concrete and symbolic, secured the term’s acceptance in professional literature. In light of the extensive scope of technical images, which emerged from a wide variety of fields, the insight was established that the research canvas must expand and discuss the genealogy of operative images, also beyond vision systems military. From this perspective, multiple histories can be traced for operative images, encompassing their diverse applications in machinic processes as well as their various forms of repurposing (Parikka 2023, pp. 12, 15).

On a theoretical level, it turns out that the need to conceptualize photography intended for technical use preceded the appearance of the linguistic definition introduced by Farocki at the beginning of the 21st century. An early expression of this can be found, for example, in an article from 1975 published in the art magazine Art Forum. As part of this essay, the theorist and artist Allan Sekula examined aerial photographs from the First World War while proposing to classify photographs with a functional purpose under the heading “applied photography.”5 Already in the very act of trying to establish a distinct photographic category for this type of picture, has become emerged the necessity of a linguistic tag, which would be the sign that always points to the original purpose of the image. This implies that the recognition of the function for which the images were intended is necessary in order to identify “the variety of their possible readings as well as the hidden conditions […] within which [their] meaning is prepared.” (Uliasz 2021, p. 1237). Sekula emphasized that especially in operative images that specify an indexical and dedicated relationship to the object, any “humanistic” interpretation must also take into account the active role of the images in transmitting data (Uliasz 2021, p. 1238).

In addition to this, the current research literature indicates that the ancient lineage of the operative images can be traced not only within the history of photography but even in a variety of histories where the visual image serves a computational function, and more generally is a means of exporting information and communication between machines even before the computer era. Parikka suggests that the roots of operative images can be found as early as the seventeenth century, and that their roots can be traced in the products related to geodetic measurements, a field in applied mathematics dealing with the measurement of the earth’s surface. Such attempts aimed to construct a picture of the world that harnessed machinic precision for human readability, effectively repurposing technical measurement into an informed perspective. What’s more, the tendency to validate knowledge on a calculative basis while prioritizing quantifiable metrics was developed by the Enlightenment school in the eighteenth century, is also fertile ground for their development. Following the change in the means of production in the nineteenth century, it is possible to find a connection between operative images and the overall trend of “industrialization of vision.”6 Be that as it may, this approach sees the images as “only one stop in the long chain of routes and operations of images” over the years, and therefore suggests that the term should be expanded to include other pictorial representations, starting with diagrams and tables, and ending with later inventions such as types of simulations and 3D images (Parikka 2023, pp. 8, 17). Within the field of media archaeology, it is common practice to analyze diverse visual infrastructures developed across different historical periods and for varied purposes as a unified category by virtue of their shared operational logic: the machine as the primary recipient. Grouping such media apparatuses according to this distinctive characteristic offers critical insight into the genealogy of contemporary visual information cultures (Parikka 2023, p. 24). In this field, contrary to the common discussion about visual images as a means of representation that promotes observation, these images are described as a kind of “actions and occurrences” that promote images of a given state of affairs, which is the product of patterns and templates, toward automatic mechanical decision-making and not in the mimetic sense of reflecting reality. Thus, these images are attributed to “have an epistemic force, while they also are involved in an intervention in the world, whether directly or indirectly.”7 This expanded trajectory leads us to cybernetics, a scientific field dedicated to the study of communication among humans, animals, and machines, particularly in the context of automatic control systems, whether organic or inorganic, from the human nervous system to electrical and computerized networks.8 Within this framework, we witness the emergence of the algorithmic operative image, images that are not merely perceived but are actively operationalized by algorithms (Farocki 2004; Hoelzl and Marie 2015, p. 100; Uliasz 2021, p. 1237; Parikka 2023, p. 23).

In her article “Seeing Like an Algorithm: Operative Images and Emergent Subjects,” Rebecca Uliasz contends that the postwar development of cybernetics, particularly in the design of feedback systems between humans and machines, catalyzed a paradigmatic shift in the ontological status of the image. As machine-to-machine communication increasingly eclipsed the need for human participation, visual images were no longer defined primarily by their representational content. Instead, their function became operational: images now act within computational systems rather than simply signifying content for human perception. Drawing on Farocki’s concept of the operative image, Uliasz argues that algorithmic vision fundamentally displaces the human subject as the privileged viewer and interpreter of visuality. From their inception, operative images have presented limited or opaque visual content to the untrained human eye. As Uliasz writes, “images become invisible with their absorption into data sets, the universe of raw matter through which algorithms touch reality.” (Parikka 2023, p. 7).

Uliasz highlights that algorithmic systems often operate as black boxes, not merely in the sense of being technically opaque, but as systems of which the logic and operation are fundamentally abstracted from human view. While machine learning models may output intelligible results, the processes by which visual inputs are transformed into decisions or actions remain largely impervious to interpretation. While Farocki examined operative images that were often presented to the professional human eye through visualizations and simulations, Uliasz shows that today within the emerging paradigm in the field of media theory, the operative image is visually not connected directly to a representation intended for human beings. In this sense, it sometimes even “disappears completely,” (Uliasz 2021, p. 1235), thus “images break from representation in the sense that they no longer mean what they appear to mean, and sometimes don’t even appear at all.” (Uliasz 2021, p. 1235). Similar to Farocki’s original definition, which focused on the transition from representation to activation, algorithmic vision changes the original conception of the image’s purpose. But this time, it is a turning point, after which the image inevitably becomes something that is necessarily different from an image, while the act of representing the object is converted into active participation in its production. In the case of the algorithmic activation image, this permutation, not only changes the process of absorption of the image by its mechanic recipients, but “the ability to know an object in the world becomes a function of the statistical distribution of pixels on a screen.” Uliasz makes it clear that the harnessing of visual data operates as a tool of subjectivation, and operative images are repurposed into instruments of governmental control. As she writes, “algorithmic vision technologies… remake the body as a function of sovereign power, a life signature given form through a recognized face… No longer bearing a primarily representative function, we see the power of algorithmic vision today is its ability to craft an algorithmic subject that is always open to contingency.” (Uliasz 2021, pp.1237–1238). In order to capture it in words, the consequences of moving the focus of attention from the plane of representation to the field of computation, Parikka makes use of the linguistic battle (invisual/visual) to describe a type of visuality directed inward. By reversing the directions of the act of representation, outside the face, he seeks to establish a distinguishing means that will be used to identify the type of images characterized by a “mathematical function”, that is, an image of which the face is directed to the world of “data and platforms”.

Beyond a simple division of contrast between the visible and the invisible to the human eye, the invisual signifies an image that is the product of mathematical construction, involving technical–cultural production. (Parikka 2023, p. 61). The image does not necessarily function as a system of signs, but as a system of signals and noises that can be produced for interpretation based on pattern recognition and cataloging. (Parikka 2023, pp. 57, 58, 60, 61). As a result, operative images of this type are endowed with the aesthetics of computer vision that harnesses statistical knowledge in favor of changing goals: “A statistical distribution of characteristics becomes a base unit of an “aesthetic,” a recognizable trait for machine/computer vision and other systems that mobilize such an aesthetic as epistemically relevant.” (Parikka 2023, p. 58).

Moreover, referring to the way in which operative images work in a computerized layered device of the platform, media researcher Adrian Mackenzie and art researcher Anne Munster emphasize that the very concept of the act of seeing as an act of observation carried out from the position of individuals has become problematic. In their opinion, it is now about multiple practices and forms of observation which are mediated and distributed by methods of data collection, analysis, and processing of “image ensembles.” Therefore, in order to fix the nature of the operative image, it is no longer necessary to refer to optics or sensory experience but must be understood as a computational entity that is frequently subjected to cataloging and formatting methods. Their appearance on the platform does not take place only in the presence of an observing subject, but also as a means that can be observed within artificial network architectures, including deep learning networks. Therefore, it is no longer a case about seeing a machine as simple, but about a perceptual change resulting from the visual activation of the platforms themselves (MacKenzie and Munster 2019).

Today, operative images are also a link between human beings and the ability to navigate the world. The examination of operator images as an integral part of a platform and their perception as an algorithmic construction that often produces a networked image, one that is linked to a host of other computerized data9, hastened researchers to locate their presence as a basic element among mechanisms that transform environments in the world into an image (Uricchio 2011; Parikka 2023, p. 129). Ingrid Hoelzl and Rémi Marie, in their book Soft Images: Towards a New Theory of the Digital Image, examine operative images that no longer represent an “event of a possible past” but in fact present a kind of event of a “possible present.” Hoelzl and Marie discuss the images that operate against the background of the analysis of the Google Street View service provided as part of the computer program: Google Earth and the mapping platform Google Maps, which allows for viewing panoramic photographs as well as satellite photographs covering large areas of the world. In their research, they describe a systematic turning point in relation to the visualization of the image, manifested in the transition from measuring the world through geometry, to reconstructing it through the algorithm, which they claim turned the image itself into an operator, based on a renewed understanding of the world as a database (Hoelzl and Marie 2015, p. 3). The two maintain that the image is no longer a fixed and passive form of representation but constitutes a networked multiplatform. In this case, the operative image is no longer a stable representation of the world, but a programmed representation of a database, which is updated in real-time. It no longer functions as a symbolic representation but takes part in a synchronous presentation of data. For them, “[t]he image is not only part of a programme, but also contains its own ‘operation code’: it is a program in itself.” (Hoelzl and Marie 2015, p. 4). Huzel and Marie claim that Google’s ongoing project to create a total image of the world has changed both the status of the image and our experience in the world. According to them, the increase in the use of Google Maps as a default, and therefore also in active images for real-time navigation needs around the world, is based on the ability to produce a combination between cartography, photography, and technical tools. Thus, they are represented as if they were always in the same symbolic space, which is actually related to the ability to carefully calculate a global database.

In this case, the images are connected to a map and an interactive database, to GPS, and to a host of other components that make up the platform. This implies that the image is not only a navigational photographic space, where the users can move through graphic elements that help them find their ways such as arrows and a compass but that the image is also hardware that is constantly updated for navigation purposes that the users can notice on the screen in real-time. According to Hozel and Mari, this is a paradigmatic example of an operator image as originally defined by Farocki; but in this case, since the images are part of a wider circle of data exchange, and since the users’ path feeds data back into the database in real-time, the operator image is not just a user service for navigation purposes. The researchers claim that this is a type of “reverse operativity” which reveals the problematic side of the algorithmic redirect. This means that while we use the images that makeup Google’s street view for our needs, they use us for the needs of returning data to the expanding database (Cetina 2003, p. 8).

The investigation of operative images, therefore, entails a critical inquiry into the mechanisms that configure their processing and the infrastructures that sustain their production and circulation, as well as into the modes through which they are creatively reintroduced to human perception (Farocki 2004, p. 17; Barad 1999). In light of this, the investigation of operative images opens a critical arena for examining not only the reciprocal entanglements between humans and machinic operations, but also the emerging possibility that machines themselves may orchestrate the reintroduction of such images for human perception, thereby shaping, and perhaps even governing, the terms of their cultural resonance and affective impact (Hoelzl and Marie 2015, p. 84; Uliasz 2021, p. 1239).

4. The Neutralization of Operative Images

Categorically, the activation of images can differ from each other in terms of their characteristics, language of representation as well as the nature of the activation applications. Nevertheless, “intelligent”10 images of this type have a common goal, which is to activate the machine. While the term emerged from a work of art that examined images belonging to this genre in order to clarify the relationship between humans and the machines, Farocki’s gesture simultaneously repurposed these operative images as material for critical and creative inquiry. In defining the image as a means of operating a deadly mechanical mechanism of war, it already became evident that it could also serve as a reporting channel from the battlefield, one capable of blocking or “switching off” unwanted looks for the human viewer. In this sense, if we rely on the influential assertion of the father of modern warfare theory, Carl von Clausewitz, that “war is not merely a political act, but also a real political instrument, a continuation of political commerce, a carrying out of the same by other mean,” we can see how the operative image was adopted as a tool to support the militant agenda through visual means.11 Thus, and as described above, a literature review found that operative images is also a means for mobilizing the civilian eye in the service of a policy that justifies military action.

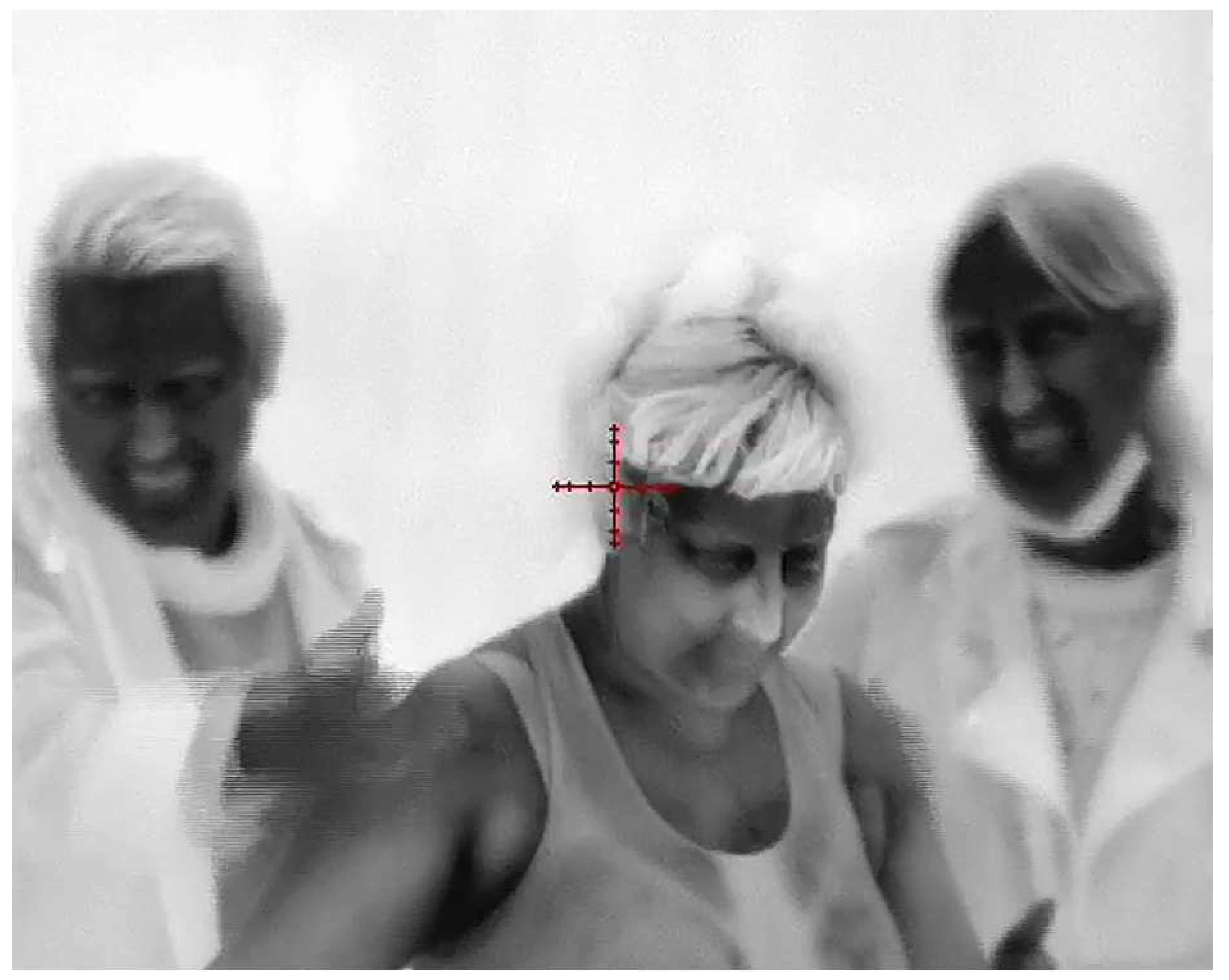

The artwork Therms and Conditions (2022) (Figure 1 and Figure 2), created by artists Ruti Sela and myself, was photographed using a thermal lens.12 Thermal imaging detects bodies by sensing the infrared radiation they emit, translating differences in heat into visual data. This technology is widely used to identify living beings in darkness or obscured environments. In military contexts, it serves as a critical component of weapon-targeting systems, enabling the precise detection and tracking of human bodies as heat signatures. One way to evade such detection is by merging with another body, effectively blending into an alternative heat source. This convergence interferes with the thermal outline, complicating efforts to isolate and lock onto a single target. The work was photographed while strolling on a winter night when strangers were asked to help us to keep warm. Through the crosshair, the work presents short encounters during which passers-by are observed while they are asked, through friction, to help us return body heat.

Figure 1.

Ruti Sela and Maayan Amir, Therms and Conditions, 01:33 min, infrared thermography, 2022.

Figure 2.

Ruti Sela and Maayan Amir, Therms and Conditions, 01:33 min, infrared thermography, 2022.

The notion of the camera as a weapon has become commonplace, a conceptual device intended to charge its visual output with power and force. Nevertheless, through repeated symbolic use, the metaphor has lost its critical edge; the aim has been missed, and the expression worn thin. In other words, the once-poetic association between image-making and death has dissipated, the violence now concealed, no longer a generative terrain for thought. While “operative images” that serve military objectives are not necessarily produced by traditional cameras, their capacity to visually mute scenes of destruction and killing has, it seems, become the default mode of representation.

In his article On the Autonomy of the Political, Israeli sociologist Yehouda Shenhav defines the political process as “an appeal expressed, by act or omission, in front of a hierarchical system of power, whether it is a system of government or a system of culture. The appeal of the political against authority seeks to expose it as an expression of power or violence and asks it to identify itself as such, and not as it seeks to present itself, as a natural system or a legitimate system of rational power (Shinhav 2009, p. 182). In his opinion, “the political act is an unusual move of appeal. It expresses an exceptional position (“state of exception”)… the appeal expresses a refusal to differentiate itself according to the demand of some disciplinary system… and it relies on the exposure of polarization” (Shinhav 2009, p. 182).

In contrast to the use of operative images as both enablers of killing machines and instruments for obscuring the visibility of violence in order to legitimize lethal action, the artwork presented here invites reflection on art’s capacity to neutralize the operative image, and, by extension, the weapon itself. Disruption of machine vision is carried out by appealing to a minimal human common denominator, a representative gesture that, at least symbolically, can put the mechanism out of action. At the same time, in the actual capture of the situation through the crosshair, it becomes difficult to discern whether the movement belongs to a friend or an enemy, thereby disrupting the possibility of straightforward classification and polarization. By introducing the idea of bodily merging, the work generates a visual ambiguity that as if unsettles the identification system’s capacity to isolate and intercept a singular subject, thereby calling into question the very conditions under which acts of targeting are deemed legitimate. The artistic move is formulated against the activation mechanism of the image, while the resulting image is in constant fluctuation between threat and comfort, between heat and cold, between comedy and horror, between mechanical and human, and between life and death. The neutralization of the operative image thus visually suspends the ability to interpret it within a single genre.

Through a minimal, yet affective, interaction, Therms and Conditions seek to address the porous boundary between activation and representation. If operative images operate within a regime that privileges action over appearance, the work proposes a return to the visible, not as transparency, but as a field of ambiguity and affect. Positioned at the intersection of simulation and realization, it mirrors the logic of thermal targeting while subtly derailing its operative function. In doing so, it opens up the possibility for art to intervene not just aesthetically, but structurally, in the visual protocols of machine vision. What emerges is a form of operative creativity, a mode of making that does not reject the computational outright but has the power to reroute its logics toward alternative ends. Rather than restoring a lost mimetic image, the work gestures toward a different ontology of the image, one that resists legibility, troubles categorization, and insists on relational opacity.

In this article, we saw that the search for operative images leads us to look back to a time before the invention of the photographed image, to a lineage of visual representations that were not necessarily mimetic or figurative but sought to quantify and measure the world through computational and abstract configurations. Early instances revealed a relative proximity between the technical function of images and the ways they were presented, for example, in military contexts where images both guided weapons and simultaneously represented the battlefield to publics. This continuity underscored how operative images could be repurposed to mobilize perception in accordance with desired interests.

Nevertheless, with the advent of machine learning and algorithmic processes, operative images have increasingly shifted toward functioning as encrypted code, signals, and data streams, forms that far-exceed human readability. Here, the gap between machinic function and human representation has grown, as the operative image often disappears into computational infrastructures. It is precisely within this gap that repurposing acquires renewed significance, through practices such as data visualization, operative images are creatively interdicted, reintroduced, and redirected toward human spectatorship. These acts of representation not only render machinic processes intelligible, but also expose the frictions and contingencies of their redeployment.

Timed against the accelerating expansion of operative images beyond human intentionality through machine learning systems that automate their production and circulation, this essay insists on operative creativity as a way to reckon with this shifting relation, where images once aligned closely with function and representation, but now return in mediated and repurposed forms that condition how human perception, interpretation, and critique are possible.

In light of the discussion presented in the military operational context, it is, therefore, appropriate to consider the repeated utilization of operative images and their unique mechanical properties when they are harnessed to serve one or other ideologies. The discussion stemmed from art and even permeated it, facilitating both the discernment and momentary suspension of machinic operations, and allowing for a redirection of the human gaze toward the eye of the machine, where the act of seeing becomes a site of exchange and mutual address.

The essay discusses the attempt to reuse operative images to operate on humans; images designed to set mechanisms in motion that, alongside their efficacy in directing machines, also risk anesthetizing human vigilance toward the realities they obscure. It is in response to this tension that the present essay proposes to name a practice, operative creativity, that accounts for image cultures in their repurposed form, i.e., practices in which operative images are wrested from their machinic functions and creatively redirected toward human perception, interpretation, and critique. In this sense, it addresses the ways in which images made not to represent are reintroduced into the perceptual field, and it is the full trajectory—from human to machine and back to human—that we must recognize and critically engage. To name this practice is to acknowledge that the future of image cultures lies not only in machinic operation, but also their continual repurposing as sites of encounter, reflection, and intervention.

Funding

This research was funded by Israeli Science Foundation, grant number 2581/20.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable; no new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I called such pictures, made neither to entertain nor to inform, ‘operative images.’ These are images that do not represent an object, but rather are part of an operation.” (Farocki 2004, p. 17). As a source of inspiration for the term, Farocki. points out a distinction between the “language of the objects” and “language of the objects” produced by the French theorist Roland Barthes in his book Mythologies: “I must return here to the distinction between the language of objects and meta-language. If I am a lumberjack and I name the tree that I am chopping down, I say—whatever the form of the sentence may be—the tree, and I do not speak about the tree… If I am not a lumberjack, though, I cannot say the tree, I can only talk of and about it.” (Barthes 1972, p. 146). See also (Zavrl 2017); “The image is a crucial part of movement and guidance”, (Parikka 2023, p. 11). |

| 2 | (Parikka 2023, p. 20). Regarding the “poor image” see also. https://www.pitom.co.il/hito-steyerl/ (accessed on 21 September 2024). |

| 3 | Butler, Judith, and Joan W. Scott, eds. Feminists Theorize the Political, 1992, p. 11. |

| 4 | On the cooperation between the American military and Hollywood see also for example: Der Derian, James. Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment-Network. 2nd ed. Copyright 2009. |

| 5 | Sekula, Allan. “The Instrumental Image: Steichen at War.” Art Forum, December 1975, vol. 14, no. 4. |

| 6 | (Parikka 2023, pp. 15, 16), a trend that also stems from Farocki’s own works; (Elsaesser 2017, p. 221). |

| 7 | Parrika, preface, p. vii. |

| 8 | “Cybernetics.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cybernetics (accessed on 30 June 2023). |

| 9 | Rubinstein, Daniel, and Katrina Sluis. “A life more photographic: Mapping the networked image.” Photographies 1, no. 1 (2008): 9–28. |

| 10 | Harun Farocki, Eye/Machine I, II and III, Video Data Bank: https://www.vdb.org/titles/eyemachine-i-ii-and-iii (accessed on 2 August 2023). |

| 11 | “War is not merely a political act, but also a real political instrument, a continuation of political commerce, a carrying out of the same by other means”, (von Clausewitz 1874). |

| 12 | (Amir and Sela 2022). It was also exhibited in the “Local Evidence” exhibition at the Eretz Israel Museum in 2022. |

References

- Amir, Mayan, and Ruti Sela. 2022. Exhibition at Lonely No More. Center for 21st Century Studies, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA, 1 September 2022–31 May 2023. Available online: www.c21uwm.com/lonely-no-more-exhibit/ (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Barad, Karen. 1999. Agential Realism: Feminist Interventions in Understanding Scientific Practices. In The Science Studies Reader. Edited by Mario Biagioli. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1972. Mythologies. Translated by Annette Lavers. New York: Hill and Wang, p. 146. Available online: http://soundenvironments.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/roland-barthes-mythologies.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1995. The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cetina, Karin Knorr. 2003. From pipes to scopes: The flow architecture of financial markets. Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory 4: 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der Derian, James. 2000. Virtuous war/virtual theory. International Affairs 76: 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaesser, Thomas. 2017. Simulation and the labour of invisibility: Harun Farocki’s life manuals. Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal 12: 214–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farocki, Harun. 2000. Eye/Machine. Installation. Available online: www.harunfarocki.de/installations/2000s/2000/eye-machine.html (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Farocki, Harun. 2004. Phantom Images. Public, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzl, Ingrid, and Rémi Marie. 2015. Softimage: Towards a New Theory of the Digital Image. Bristol: Intellect Books. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, Anna, and Anna Munster. 2019. Platform seeing: Image ensembles and their invisualities. Theory, Culture & Society 36: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglen, Trevor. 2016. Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You). The New Inquiry. Available online: https://thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Pantenburg, Volker. 2016. Working images: Harun Farocki and the operational image. In Image Operations. Edited by Eder J. and Klonk C. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Parikka, Jussi. 2023. Operational Images: From the Visual to the Invisual. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Available online: www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/operational-images (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Shinhav, Yehuda. 2009. Examining political autonomy. The Concept of the Political: Theoretical Analysis and Critical Insights. Journal of European Public Policy 30: 1820–38. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, Roger. 2018. Through the Crosshairs: War, Visual Culture, and the Weaponized Gaze. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. 224p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliasz, Rebecca. 2021. Seeing like an algorithm: Operative images and emergent subjects. AI & Society 36: 1233–41. [Google Scholar]

- Uricchio, William. 2011. The algorithmic turn: Photosynth, augmented reality and the changing implications of the image. Visual Studies 26: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virilio, Paul. 1989. War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- von Clausewitz, Carl. 1874. On War. Translated by Colonel J.J. Graham. New and Revised Edition with an Introduction and Notes by Colonel F.N. Maude C.B. (Late R.E.). 8th impression in three volumes. Reprint, 1909. Project Gutenberg. Available online: www.gutenberg.org/files/1946/1946-h/1946-h.htm#chap25 (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Zavrl, Nace. 2017. Counter-operation: Harun Farocki against the network. Afterimage 45: 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylinska, Joanna. 2017. Nonhuman Photography. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).