1. Introduction

The Russian empire’s displays of applied and decorative art at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and its immediate successors have long galvanised scholars for their semantic complexity. Distinctive, eye-catching, and subject to moments of occasional drama in their transportation and installation, these exhibits, joined from 1862 by figurative bronze sculptures, served as a stock mannequin on which contemporary observers embroidered a host of narratives and stereotypes. If the emphases of these accounts varied, a common thread linked the extravagance of the decorative artefacts to Russia’s exoticized status on the periphery of Europe and to the absolutism of tsarist rule.

By contrast, Russia’s first selection of paintings for this fiercely competitive arena failed to ignite the public imagination and has largely evaded the historian’s gaze. Indeed, Russian painting was seen by contemporary as well as later commentators to make a late, apologetic, and underwhelming entrance at the London exhibition of 1862, a full eleven years after the initial event. While the three-dimensional artworks provided a recurrent source of wonderment for their superlative craftsmanship, stupendous materials and, at times, hyperbolic proportions, the paintings were apparently flat in every sense of the word: derivative, lacklustre, and incapable of capitalising on the opportunity that international exhibitions offered to present a national school.

This cutting narrative of the ineffective debut of Russian painting on the international stage proved highly resilient thanks in part to Vladimir Stasov, the dominant art critic of his generation, who insisted that his country’s route to artistic apotheosis lay in critical realism. For Stasov, recent genre paintings that probed the underbelly of Russian life were egregiously overlooked in the submission of 1862, sidelined by fusty officials whose conservative taste still drew them to the anodyne subject matter and slick finish favoured by academic artists. While he welcomed the inclusion of certain anecdotal and satirical scenes, they could not compensate for the pabulum of the overall display.

These views were largely shared by the relatively few British critics who deigned to comment on Imperial Russian painting amid their encomia to the empire’s sculpture and decorative arts. Their dismissive comments set the tone for many later accounts, embedding the idea that Russian painting prior to the twentieth century was of limited consequence—a perception that would prove convenient to those asserting the originality of the avant-garde. Indeed, it has led to the marginalisation of Imperial Russian artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth century as much for undergraduate students and major international museums as for writers of broad histories of art, and is as strong today as it was in 1862.

The difficulties of defining ‘Russian’ played a significant part in shaping the mid-nineteenth-century attitudes that heralded these blind spots and imbalances in western engagement with Russian art. The empire was a multinational state, albeit with Russian as the primary language of business and education. Yet, for the 1862 exhibition, the concept of ‘Russian’ was applied largely in terms of geography rather than ethnicity, serving as a catch-all term that swept up artists and producers from a vast range of backgrounds. Several of the figures discussed here maintained dual identities, and the exhibits were produced by people of many different ethnicities. The famed malachite vases, for example, were made from stone which was mined and worked by ethnic Russians, Bashkirs, and Tatars, among others, and used models designed by foreign European as well as ethnic Russian artists. British critics and commentators were largely ignorant of and certainly made no effort to address this ethnic and cultural diversity in their reviews.

What is more, some of the artists who featured at the 1862 exhibition had names that did not sound Russian, such as Bruni, Moller, and Lagorio. It is possible that British commentators perceived these figures as foreign, despite the fact that they had been born and raised in Russia. Such a misunderstanding would have fuelled the critics’ assumptions that Russian painting, like the work of some manufactories, was indebted to western European example. It could even have influenced their disdain for Russian works that apparently lacked ‘national character’ (could an Italian-sounding artist produce such a thing?), and the prescriptive and predetermined categories that they imposed on Russian art.

These complexities and misapprehensions go some way to explain the muted if not hostile responses to Imperial Russian painting at the London exhibition of 1862. Yet renewed consideration of these artworks suggests that their critical reception speaks to concerns that went well beyond the pictures’ supposed obligation to represent a national school—the rubric against which all the fine art displays were assessed. Notably, a small but significant number of history and portrait paintings by academically trained and often well-travelled artists challenged notions of Russians as primitive and parochial. The technically adventurous of these parried the belief that Russian art was insufficiently mature to experiment in painterly effect. Most audacious of all, they broached unspoken national boundaries by daring to suggest that Imperial Russian artists could innovate in areas on which the success of British painting rested. The attitudes towards Russian painting in 1862 thus invite fresh scrutiny, revealing as they do a disruptive arena in which aesthetic rivalries and chauvinist sensibilities came to the fore.

2. The Narratives of 1851

To establish the baseline for these contested notions of rightful place within European artistic traditions, we need first to revisit perceptions of Russia that circulated and consolidated at the Great Exhibition, the inaugural international exhibition memorably staged in the Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park in 1851.

1 The exhibition’s champions were keen for Russia to participate long before this landmark event opened. In February 1850, Prince Albert, the exhibition’s co-organiser and patron, impressed on Baron von Brunnow, the Russian ambassador to the Court of St James, how he hoped to see in London the likes of Russian fur, leather, Tula steel, malachite, and brocade (

Swift 2007, p. 245). The Russian government in turn was keen to flaunt the empire’s industry and enterprise, despite concerns that the crowds anticipated at the event might foster political radicalism (

Hobhouse 2002, p. 57). Yet the commissioners of the Russian section met with resistance from the manufacturers, industrialists, and artists invited to take part. Striking is the experience of Count Fedor Tolstoi, a renowned still-life painter, medallist, sculptor, and Vice President of the Imperial Academy of Arts, who, charged with assembling a fine art division, made repeated overtures to his colleagues, but ended up being the sole Academician to contribute. Tolstoi’s offer of bas-reliefs, medals commemorating the 1812 victory over Napoleon, and a small bronze model of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, then under construction in Moscow, would receive a fleeting mention in the London press, but was far from the revelation of Russian art that the selectors had had in mind (

Swift 2007, p. 247).

A substantial Russian submission nonetheless took shape, with its first two shipments arriving in London in autumn 1850. But other consignments, late to leave St Petersburg, were delayed by ice floes in the Baltic Sea and a major shipment did not reach Britain until May 1851, by which time the exhibition had opened. The Russian section had to close while the Russian Commissioner to the Exhibition, Gavriil Kamenskii, and his team laboured behind specially erected curtains for fourteen hours at a stretch to install the recent arrivals. A newly extended display reopened to the public on 7 June.

2That same day,

The Illustrated London News took aim at Russia as a bastion of authoritarianism in a damning article emblazoned across its front page, confirming the exhibition to be a battleground for political ideologies as much as it was a showground for the triumphs of modern industry and trade. While St Petersburg was characterised as ‘more than ever the home and centre of absolute conservatism, or conservative absolutism’, London was vaunted as ‘the real capital, not alone of the world’s material civilisation, but of the spiritual idea of progress and improvement’ (

The Old and New Holy Alliance 1851, pp. 503–04).

This opposition between Britain as the centre of entrepreneurial advancement and Russia as a despotic backwater recurred in other accounts (

Fisher 2008, pp. 123–45). Yet the well-worn stereotype was countered (often in the very same publications) by effusive commentary on the luxury goods and decorative arts which occupied about half of Russia’s exhibition space. With their combinations of material splendour, expert workmanship, and astounding ornamentation, these works dominated the coverage of Russia in British guidebooks and the periodical press, as they would at later events.

3According to her diary, even Queen Victoria, a regular and enthusiastic visitor to the Crystal Palace, was impressed:

June 11. To the Exhibition, with our relatives. We went first to look at the Russian exhibits, which have just arrived and are very fine: doors, chairs, a chimney piece, a piano, as well as vases in malachite, specimens of plate and some beautifully tasteful and very lightly set jewelry. … we came home at ¼ to 12, and I felt quite done and exhausted, mentally exhausted [emphasis in the original].

June 12. After breakfast to the Exhibition. Viewed the Russian exhibits […] among which were silk and gold brocades from Moscow, which beat the French and are really magnificent.

4

As the wife of the exhibition’s patron, the queen was well aware of its prime agenda of national showboating. Her direct comparison between Russian and French textiles certainly suggests that the ostensible aim of good-natured competition between nations and empires was well understood.

5A particular showstopper in the Russian section was the work in malachite, which served as a synecdoche for the resplendent and at times outlandish

objets d’art that set in sharp relief the domestic and utilitarian items. Indeed, a major descriptive account of the exhibition published in 1851 summed up the entirety of the Russian display as simply ‘Russia, with its malachite doors, vases, and ornaments’ and ‘Russian cloths, hats and carpets’ (

Virtue 1851, p. xxv). The malachite doors, produced by the Demidov Brothers’ manufactories and standing at over four metres tall and two metres wide, prompted especial incredulity for their opulence and scale. According to

The Illustrated London News:

Our readers have probably made acquaintance with malachite as a precious stone, in brooches, jewel-boxes, and other small articles of ornament, but never dreamt of seeing it worked up into a pair of drawing-room doors. The effect is exceedingly beautiful; the brilliant green of the malachite, with its curled waviness like the pattern of watered silk, and its perfectly polished surface, is heightened by the dead and burnished gold of the panellings and ornaments, and sets one imagining in what sort of fairy palace and with what other furnishing and decoration the room must be fitted to satisfy those who had made their entrance by such precious doors.

This report similarly delighted in the silverware by Ignaty Sazikov, whose large candelabra depicting Dmitry Donskoi after his defeat of the Mongol forces at the Battle of Kulikovo (1380) was discussed more than any other Russian artefact and won a Council Medal, the event’s highest award.

6 The emphasis here on subject matter of national relevance speaks of the need to ‘other’ Russia’s artistic imagination by focusing on a sensational event from Russian history at the expense of other themes and interests evident in the Russian display—a bias that would re-emerge in 1862, as we will see.

The article in The Illustrated London News also enthused about an ebony cabinet topped with an ingenious mosaic depiction of fruit that featured in several accounts. Designed by Baron Petr Klodt, produced by the Imperial Lapidary Works at Peterhof, and lent by Tsar Nicholas I, this apparently included a bunch of currants ‘so true to nature, that the Prince of Wales said, “He should really like to eat them.”’

The writer was nonetheless quick to point out that items of such extravagance presupposed elite patrons of extreme privilege. While the Russian section included objects ‘of great value, from their rarity and workmanship, and of real beauty of material and design’, it was ‘made up entirely of articles for those whose wealth enables them to set no limit to the indulgence of their tastes’ (

The Russian Court 1851, p. 597). The implication that the more practical products displayed by British manufacturers had a moral superiority to the exorbitance of Russia’s exhibits was echoed in other British publications. As

The Times pointedly remarked, the ebony cabinet was ‘worthy in every respect the magnificence of the Autocrat’ (

The Great Exhibition 1851, p. 8). Making explicit the criticism of an authoritarian regime reliant on the system of serfdom for its vast labour requirements, an infamous caricature in a broadsheet entitled

The Productions of All Nations about to appear at the Great Exhibition of 1851 depicted Nicholas I hauling a barrel that was labelled ‘elbow grease from 30,000,000 serfs’ (

Auerbach 1999, p. 168).

Another report in The Illustrated London News extended the geographical compass further still to compare Russia’s political system unfavourably to that of the United States:

The accident that has placed the produce of Russia next to that of the United States is curious and suggestive. The greatest empire next to the greatest republic—pure despotism side by side with perfect self-government, vigorous private enterprise compared with the results of Royal patronage; yet there are strong points of resemblance between the two countries. […] Both have still huge tracts of land to be cultivated. Both are rich in raw produce and natural wealth. But the progress of Russia depends almost on one irresponsible man.

Unlike other observers, this commentator was not seduced by the work in malachite. ‘The malachite vases are not, as they would at first sight appear, solid, but veneered, as it were, on copper.’ Driving home the message of fathomless riches produced for an Epicurean autocrat, the writer concluded that ‘the whole of this collection […] composes a brilliant museum of what may be termed

Royal toys, in contrast to the spades and axes which compose the

heavy steel toys of Birmingham. They are not made for profit or the subject of any export trade’ (

The Contributions of Russia 1851, p. 127). Interesting here is that the writer is not only censuring excessive luxury and indulgence, but also highlighting the contrast between lavish artefacts produced for imperial pleasure and good honest works produced for the marketplace. In fact, many exhibits in the Imperial Russian section were offered for sale by both the Imperial manufactories and private firms seeking new customers and business opportunities. Now evident in public and private collections, these objects attest to the inaccurate British reporting which enabled a false understanding of the intention and consumption of Russian applied arts to take hold.

The writer of

The Illustrated London News report tapped into a further debate that was gathering pace in accounts of the Great Exhibition by claiming that Russian producers imitated foreigners working in Russia, who were seen to brandish a superior artistic toolkit (a view that some Russian commentators shared).

7 ‘It is understood that the porcelain manufactory is under the direction of a Frenchman; and although the Russians have shown great talent in making external copies of various works, they do not as yet much understand the meaning of honest workmanship in articles that require exactness of fit. Indeed, in St Petersburg, almost all work of fine art or taste is in the hands or under the direction of foreigners’ (

The Contributions of Russia 1851, p. 127). The paradox of carping at imprecise handiwork while the empire’s decorative artefacts were repeatedly singled out for their skilful artisanship went unremarked.

The accusation of servile following had already been made in

The Morning Chronicle, compelling Kamenskii to publish a sharp rebuttal in that same newspaper (

Swift 2007, p. 250). Yet British writers continued to disseminate a message of Russian dependence on foreign talent, as Anthony Swift has explored (

Swift 2007, pp. 249–54). ‘The principal manufactories of St. Petersburgh [sic] are either the property of foreigners or of the Crown, in which latter case most of them are placed under the superintendence of foreigners’, proclaimed

The Illustrated Exhibitor on 26 July (

Russia 1851, p. 128). This comment reveals an awareness in Britain of the workshops and studios that flourished under non-Russian leadership, but an ignorance of the extent of native cultural production. In fact, the Academy of Arts (founded 1757) had by now produced generations of highly trained artists and craftsmen, and the likes of Sazikov, an undisputed star at the Great Exhibition, attest to the success of Russian-led firms. Repeat mention in the British press of Russian indebtedness to foreign example thus confirms the resilience of the notions of a still under-developed nation incapable of refined artistry or taste.

In this respect, British commentators revived the shibboleth of Russians as primitive and uncivilised. Particularly instructive is a pamphlet of etched cartoons whose xenophobia was evident from its very title:

Mr & Mrs John Brown’s Visit to London to see the Grand Exposition of All Nations. How they were astonished at its Wonders, Inconvenienced by the Crowds, & frightened out of their Wits, by the Foreigners. Here, Russia was denoted by a bushy-haired, sabre-wearing figure in an image captioned ‘A good natured Don Cossack takes notice of Anna Maria [the fictional Brown family’s daughter], much to her terror.’ Russia was far from alone in being demonised in this way: a group of ‘American Indians’ threw the Browns ‘into a state of extreme terror’, while ‘a party from the Cannibal Islands, after eyeing little Johnny, in a mysterious manner, offer a price for him.’ Some of these people even had the temerity to return the (white) British gaze. ‘Mrs B. is so alarmed at the impudent way the foreigners look at her, that Mr B. indignantly quits the place’ (

Onwhyn 1851;

Auerbach 1999, pp. 173–74).

Equally complicit in racial stereotyping was

The World’s Fair; Or, the Children’s Prize Gift Book, an avowedly colonialist account that revelled in highlighting the obtuseness, villainy, and exploitation that obtained abroad.

8 Russia got off relatively lightly. ‘I don’t think you or I would like to spend a winter in Russia’, the writer averred, but Russians were ‘remarkable for their cheerfulness and contentment, and are so fond of singing, that they are always enjoying a song when at work’ (

World’s Fair 1851, pp. 20–21). Nonetheless, the fact that Russians were clumped together with Indian, Turkish, and Chinese people in the early pages of the book before it segued via Spain and Portugal to ‘civilised’ western countries reinforced Russia’s consignment to an exotic, eastern world.

This trope of viewing Russia through an orientalising lens recurred not only in broadsheets and supposedly humorous accounts structured on racial and ethnic lines, but in specialist publications targeting audiences interested in the visual arts. For

The Art Journal, ‘the Russians have evidently caught from the East their feeling for colour’ with exhibits that carried ‘the impress of the half-oriental, half northern character so peculiar to that vast empire’.

9 For all the droves of Russian artists who had been sponsored by the Academy to study in western Europe by this point, the commentary of 1851 excluded them from any sense of a pan-European community, and instead assigned them a distant, eastern caste. The persistence of such assumptions illustrates the challenge local audiences faced in reconciling the acknowledged quality of the empire’s decorative arts with an engrained understanding of Russia as a backward, barbarous, and semi-Asiatic state.

This, then, was the matrix of, at times, contradictory readings within which British critics comprehended Russian artistic producers in 1851. To British eyes, the Russians’ dexterous fashioning of sumptuous materials was above reproach, even if their technical mastery still needed finessing under foreign supervision. Their work was oriental and exotic at the same time as it stemmed from the autocratic dictate of a westernised court. And there was a whiff of the primitive about them, even though a key exhibit transfixed the Prince of Wales with its virtuosic trompe l’oeil effects, and the queen herself compared Russian brocades favourably with French work. Reflecting ambitions for the Great Exhibition as a supreme showcase of British imperialism (Britain and its colonies accounted for over half of the exhibits and occupied half of the total space), these conflicted messages demonstrate the difficulty local critics had in positioning the creative accomplishments of a distant empire on the international stage.

10For all its weaknesses, the scaffolding these writers constructed for the critical assessment of Russia’s artistic representation in 1851 proved reasonably robust, and much of it was resurrected to frame responses to the 1862 exhibition. It proved fit for purpose to re-engage with the applied and decorative arts and to address the sculpture that made its debut that year, even if adjustments in emphasis and rhetoric were needed to acknowledge the success of many of these works.

By contrast, the selection of paintings in 1862 eluded any clearcut taxonomy. Some of the genre paintings had at least a semblance of the national commitment that British and Russian critics now required. But a slate of history paintings and portraits confounded critics with subject matter and stylistic qualities that not only failed to oblige Stasov’s dogged notion of what constituted Russian artistic autochthony but also strayed uncomfortably onto western European turf. In going against the grain of nationalism that coursed through the London Exhibition of 1862, these cosmopolitan pictorial sensibilities inevitably inflected the critical response and go some way to explain the lacunae as well as the emphases in both contemporaneous and future commentaries on Russian art.

3. The Nationalistic Playbook of 1862

As the hostilities of the Crimean War had foreclosed Russia’s participation in the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855, there was heightened interest in the empire’s re-engagement at the International Exhibition in London in 1862. This opened on 1 May, in premises in South Kensington whose ill-judged design by Captain Francis Fowke met with wide derision in the press.

11 Russia’s decorative arts were again profiled in guidebooks and reviews. For one writer, ‘On the Russian stand, attention should be paid to the candelabras, vases, and handsome Corinthian column in Jasper; the curious letter-weights, inkstands &c.; of jasper and porphyry, ornamented with groups of fruits and flowers ingeniously produced in natural stones; the handsome porcelain vases; and the works in graphite’ (

International Exhibition 1862, pp. 30–31). Such succinct advice was typical of the guidebooks that were rushed off the press in immediate response to the displays, this particular example being designed for the reader who would visit the exhibition just once. But their themes were echoed in more extensive and reflective coverage in commemorative volumes that appeared after the event.

Exemplary in this respect was J. B. Waring’s

Masterpieces of Industrial Art & Sculpture at the International Exhibition, 1862, which was published in three volumes in 1863. This lavish production of coloured plates with attendant text perpetuated the trope of Russia’s exoticism. The ‘ornamental table-glass’ produced by the Imperial Russian Glass Manufactory, for example, ‘bore a certain look of Asiatic richness’ (

Waring 1863, vol. 1, Plate 51). Such hoary categorisations co-existed with fulsome tributes to Russian craftsmen and producers. There were old favourites from 1851, such as the silversmith Sazikov, who ‘appeared in undiminished strength’, and work in precious metals was consistently praised. ‘Nothing could exceed the variety and fancy displayed in the designs of the Russian goldsmiths’ work, or out-match the beauty and delicacy of their execution’ (

Waring 1863, vol 1, Plate 65). Items from the imperial manufacturers were exalted, such as a mosaic of St Nicholas designed by the Baltic German artist Carol Timoleon von Neff and produced by the Imperial Glass Manufactory (

Waring 1863, vol. 1, Plate 97). Embroideries expertly worked ‘with gold and silver thread, and silk of divers colours’ were similarly extolled for an excellence which attested to ‘both ingenuity and experience’ (

Waring 1863, vol. 2, Plate 187).

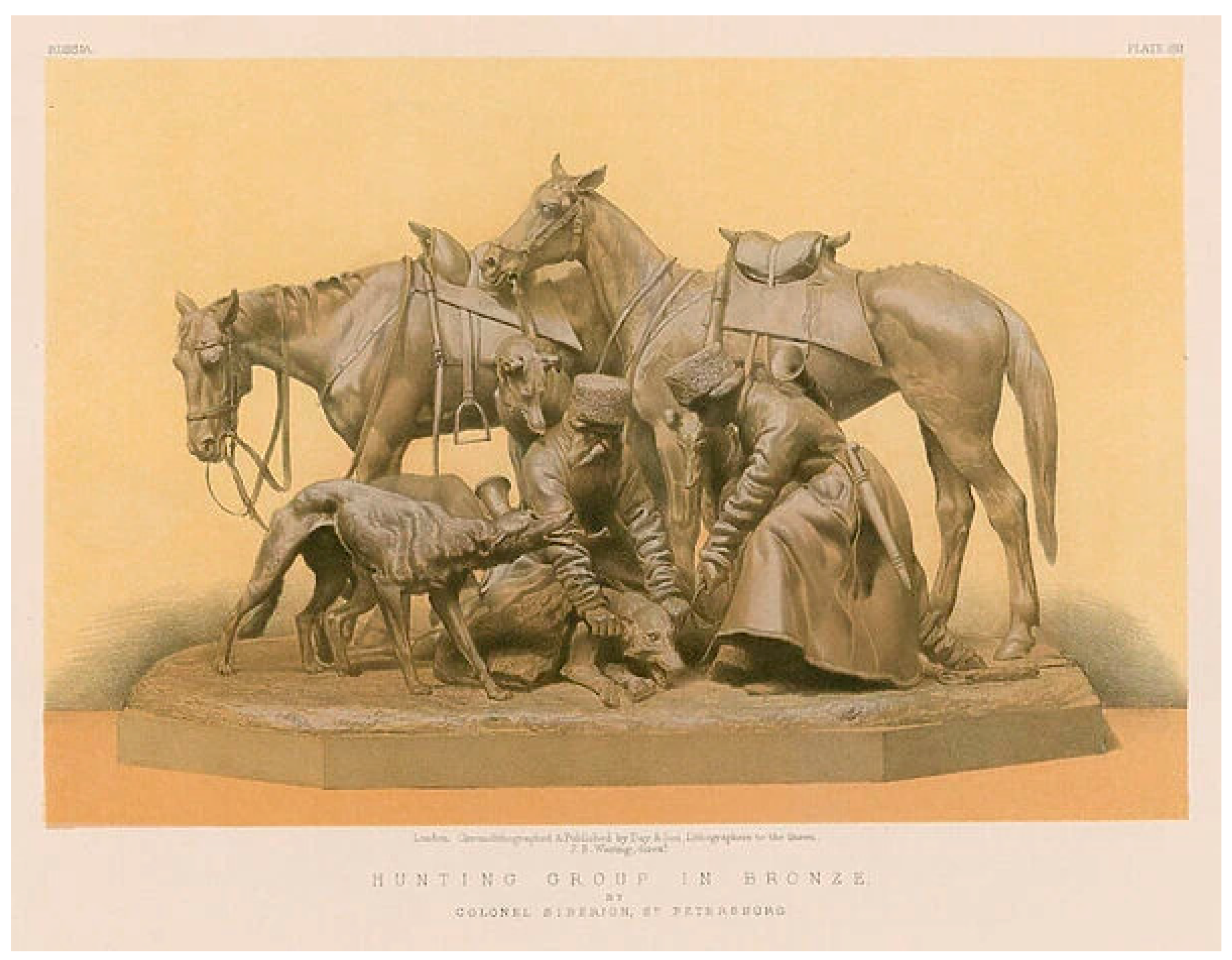

These various reviews confirm that, if the range of media represented had expanded since the Great Exhibition, key terms of discussion were retained. High-quality materials were recognised. Fanciful decoration was relished. Ingenious design was acclaimed. Significantly, these criteria of excellence also applied in Waring’s assessment of the bronze sculptures in their inaugural display. Witness the rhapsodic account of three hunting groups by Nikolai Lieberich, an artist of German origin who, following service as a military officer, had studied under Petr Klodt and been appointed an Academician in St Petersburg the previous year (

Figure 1):

Nothing could exceed the truthfulness, spirit, and fine execution of these charming little groups, which were evidently closely studied from the life, and rendered faithfully all the peculiarities of Russian hunters, their horses and dogs: everything bore the stamp of strongly-marked individuality, and the execution of the most minute parts—the anatomy and veins of the wearied horses, the shaggy-skinned and panting wolf, and the strength, fleetness, and pride of the successful coursing dogs—were portrayed in a manner which, to our mind, found no equal in other works of the same class exhibited by the French, who have so justly obtained the highest reputation in this branch of sculpture.

In the same vein, a report in

The Times panegyrised Lieberich’s bronzes ‘which are, certainly, unequalled for perfection of workmanship, life, and truth by anything of the kind in the Exhibition’ (

Pictures of the International Exhibition 1862, p. 3). Meanwhile,

Ivan Destroying the Heathen Gods by the Academy professor Nikolai Pimenov was extolled by Waring for being ‘characterized by great vigour and simplicity of treatment,’ and ‘entirely free from that exaggerated expression of sentiment which is becoming so common in France’ (

Waring 1863, vol. 1, Plate 220). Russia’s bronzes thus not only achieved distinction within the context of the broader Russian submission, but were seen to outstrip even such an artistic heavyweight as France.

12For many commentators, key to this success was the sculptors’ focus on subjects of historical or local resonance, such as Lieberich’s skilful evocation of ‘the peculiarities of Russian hunters, their horses and dogs’, and Pimenov’s selection from the account in the

Primary Chronicle (a twelfth-century account covering the period 852 to 1110) of Grand Prince Vladimir’s conversion to Christianity in medieval Rus’. As Waring explained, ‘Vladimir became a Christian, and introduced Christianity amongst his people. The Russians inhabiting Kiew [sic], the ancient capital, threw Peroun, their Jupiter, into the river Dnieper; and we here see a young Russian warrior trampling on the idol, which the river god stretches out his hand to receive’ (Waring, like countless writers, conflated the peoples of ancient Rus’ with Russians) (

Waring 1863, vol. 1, Plate 220). The empire’s sculptors here were doing what was expected of them in British eyes: they were sticking to a rulebook that required Russian artists to keep within iconographic territory that was firmly demarcated as Russian. British critics, it would seem, were able to praise the resulting compositions when such niceties were observed. When it came to certain paintings, however, such boundaries were troublingly transgressed.

The pictures selected for London had been assembled by the St Petersburg Academy under the purview of Fedor Iordan, a professor of engraving possibly chosen for the role as he had studied in England in the 1830s. After long debate and the display of a preliminary line-up in the Academy, a final slate of 78 oil paintings, watercolours, and drawings was agreed. These were mainly from the collections of the imperial family, though a handful of private collectors lent key works, among them the young Pavel Tretyakov.

13 The selection was dominated by genre paintings including Aleksei Venetsianov’s

Peasant Girl Receiving Holy Communion (now known as

Dying Girl’s Confession, 1839), Pavel Fedotov’s

The Major’s Courtship (1848) and a version of his

Widow (c. 1850), Konstantin Trutovsky’s

Village Dance in Kursk Province (1860), and Aleksei Chernyshev’s

Organ Grinder (1852: all State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow). Of the landscapists, Ivan Aivazovsky was represented by four pictures, Aleksei Bogoliubov and Mikhail Lebedev by three each, Lev Lagorio by two, and four other artists by a single work. There were also a number of portraits and history paintings by the living artists Fedor Moller and Pavel Chistiakov, as well as earlier Academicians such as Anton Losenko, Fedor Bruni, and Alexander Ivanov, to which we will return.

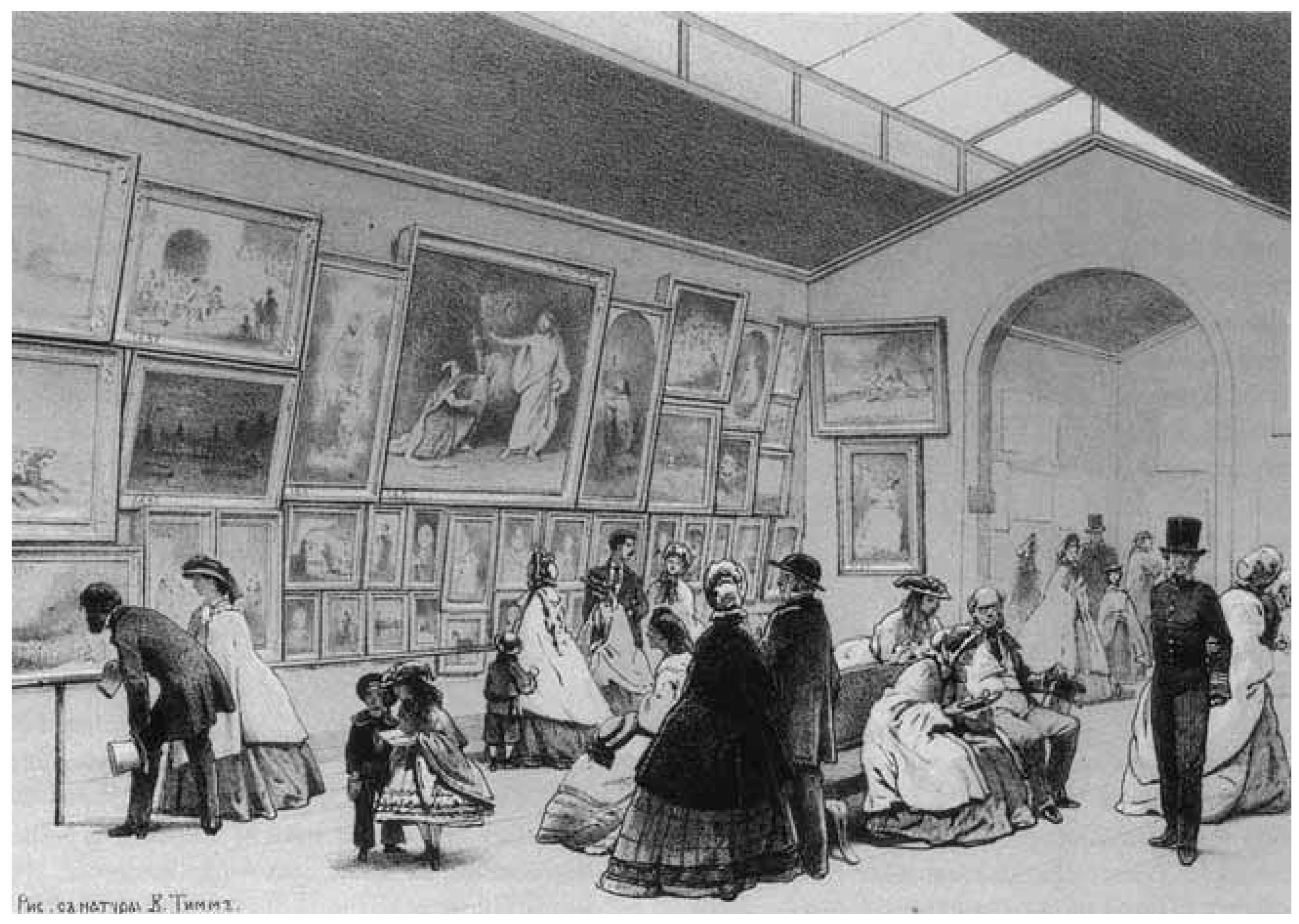

A lithograph published in Vasily Timm’s popular

Russian Arts Bulletin shows the ensemble arranged in London in a typical salon hang, with smaller paintings tessellated at or below eye level while larger paintings were displayed ‘above the line’ (

Figure 2). According to Iordan, the impression was of a coherent national display. ‘One could see the surprise of those viewing the Russian school for the first time’ (

Kondakov 1914, p. 46). But the critical response was lukewarm, with commentators struggling to make sense of images for which they had no context or history. Certain questionable decisions by the Russian selectors contributed to the incomprehension. For a start, they sent strikingly few pictures to this, the largest art display ever assembled.

14 Moreover, fewer than fifty of the Russian pictures were oil paintings, and even these included copies. Fedor Alekseev, for example, was represented by a painting after Bernardo Bellotto’s view of the Zwinger Palace in Dresden (1779–early 1790s, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), rather than by the likes of his acclaimed

vedute of Moscow. The catalogue of Russian items provided only a cursory list with scant secondary information, which Waring contrasted unfavourably to the detailed accounts provided by Austria and Italy.

15 The Russian section also lacked labels in English and was chaotically arranged, which caused Russian visitors to despair (

Dianina 2013, p. 64). The result was a cultural misstep that could not fail to limit the appreciation of Russian art.

Even those who admired some of the paintings continued to insinuate that Russian artists aped foreign ideas. On 31 October,

The Times commended works with quintessential Russian subjects by Venetsianov, Aivazovsky, Timm, Alexander Morozov, Nikolai Sverchkov, and Valerian Iakoby, but tempered this by claiming that Iakoby’s

Peddler Selling Lemons (1858, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) was ‘the best piece of character painting here—a perfect Russian Autolycus’ (

Pictures of the International Exhibition 1862, p. 3). By invoking the story of Autolycus, a classical exemplum of thievery and metamorphosis, this comment reprised the 1851 narrative of Russian creatives beholden to western European precedent. For this, as for other writers, Russia’s slavish imitation continued to preclude the realisation of its own artistic identity. Dmitry Grigorovich, the author of a lengthy account of the British painting galleries, found that the Russian school ‘still has no original character: it imitates now Italy, now France, now Belgium’ (

Grigorovich 1863a, Part I, p. 818). Théophile Thoré, who reviewed the exhibition pseudonymously for publications including

Temps and

L’Indépendence, likewise found the Russians derivative of European developments (

Thoré 1870, vol. 1, pp. 303–9).

This failing was not unique to Russia, however, but was seen to apply to several artistic displays. In a rare column dedicated to Russian art (one of a series on different national schools), J. Beavington Atkinson declared that, ‘As might have been anticipated, for originality we find imitation, and instead of the unity of a national and historic style, we have a discord, in which all the schools of Europe take common part’ (his preamble here of

expecting epigonic behaviour from Russians underlines how pervasive this notion had become) (

Atkinson 1862, pp. 197–98). Even the exhibition’s official art handbook by the critic and poet Francis Turner Palgrave lambasted foreign artists across the board, despite the fact that its purpose was presumably to celebrate the artistic contributions:

it might be rash and unsafe to attempt even a sketch of Painting in the Russia and Scandinavia of to-day […] still less in countries which, like Spain, Italy, and America, appeal so decidedly to the Future. Artists of ability have not been wanting here during this century, yet it is probable that in none of these states has Art yet taken a form which fully represents the nation as it is.

16

So stinging, not to mention diplomatically unwise, was Palgrave’s attack that, following indignant letters to

The Times, the handbook was withdrawn from circulation just weeks after the exhibition opened by red-faced Commissioners who had not read its relentless invective before it went on sale. The unrepentant Palgrave responded by having his publisher Macmillan issue a heavily edited version to sell in nearby bookshops instead (

Nelson 1985, pp. 56–59).

These and other accounts demonstrate the prevalence of a nationalistic agenda in 1862. It was not enough for artists to produce technically and aesthetically impressive paintings or sculptures. They had to respond to native traditions, landscape, and temperament. For many critics, Dutch genre scenes and Nordic landscapes did this well (see

Prasch 1990, pp. 28–29). But the standout winner, occupying no less than half the total space allocated for art at the exhibition, was the British school (often referred to as English at the time, though Scottish artists such as David Wilkie played an important role). In a sublime public relations exercise, the curators of this section constructed a seemingly unassailable narrative whereby Hogarth had initiated a recognisable school which developed unique strengths in portrait, landscape, and genre painting. Commentators of many backgrounds and persuasions readily enforced this teleology. For

The Times, Hogarth was ‘thoroughly and in a word national’.

17 Grigorovich found the works of English genre painters to be ‘imbued with the spirit of national character’, while Constable, Turner, and Richard Parkes Bonington embodied the qualities of English landscapes (

Grigorovich 1863b, Part II, p. 44).

The Illustrated London News proclaimed English art to be ‘simple, spontaneous, natural, domestic, direct’.

18 For Thoré, ‘L’école anglaise prendra désormais son rang dans l’histoire d’art’ (

Thoré 1870, vol. 1, p. 314).

Unsurprisingly, in light of the exhibition’s location in London, this forceful construct set the standard against which all the national displays were judged. Witness Atkinson’s exhortation of Russia, which read: ‘She stands as the hero of the Slavonic races, and the champion of the eastern church, and from out her midst must yet arise an Art,

consonant to her zone, her people, and her faith’ [my emphasis] (

Atkinson 1862, p. 198). Observers of the Russian section largely concurred that genre painting was the prime carrier of such innate national truths. In his popular

Handbook to the Pictures in the International Exhibition, Tom Taylor spoke for many in highlighting ‘the pictures which treat of Russian life and nature,’ among them a painting by Iakoby that was ‘full […] of local truth’ and Alexander Morozov’s ‘meritorious picture of closely-studied Russian peasant life’ (

Taylor 1862, pp. 196–97).

Moreover, to achieve the necessary national distinction, commentators expected of Russian as well as other foreign artists the same rejection of academicism that was seen to underpin the success of the British school (

Prasch 1990, p. 29). Telling here is the commentary accompanying a reproduction in

The Illustrated London News of Sverchkov’s painting

A Village Wedding-Train, part of which can be glimpsed on the left of Timm’s lithograph (see

Figure 2). This account began by noting Russia’s general topicality in light of the improved relations with Britain since the end of the Crimean War and the sociopolitical upheaval that had followed the emancipation of the serfs in 1861 (

A Village Wedding Train 1862, pp. 144–45). But it expressed regret that the artists who had responded to the unrest were not represented at the exhibition, for which the heavy hand of academicism was apparently to blame:

Some of the most recent pictures by Russian painters have contained very significant premonitory indications of popular uneasiness. None such works have, however, found their way into the small selection of pictures by which […] in the International Exhibition, the partial development of art in Russia is illustrated. We must seek elsewhere for any political allusions. All the earlier pictures of the Russian school are the result of academic fostering, or, as we might, perhaps, with more propriety say, forcing; and they exhibit the fruits of foreign study in Italy and Germany.

For this writer, Russia’s route to artistic self-realisation lay in the depiction of uniquely Russian scenes: ‘In Russia, as in nearly all Continental countries, the circumstance which promises most for the establishment of a national school is, that artists are beginning to forsake the academical and exotic subjects and treatment, and to betake themselves to the representation of incidents and scenes of native history and life.’ To the writer’s regret, these were precisely the sort of works that were underrepresented in London, though Sverchkov’s ‘spirited, amusing, and well-painted picture’ was a welcome exception to the rule (

A Village Wedding Train 1862, pp. 144–45). Others agreed, sharing in both the clamour for local flavour and the acclamation for Sverchkov, whose sleighs in frozen landscapes provided British critics with the Russian vision that they craved.

19These attestations were music to Stasov’s ears, corroborating his view that the omission of critical realism from the selection for London had led to an incomplete account of Russian art. In both an article written in immediate response to the Russian display in 1862 and a lengthy retrospective published the following year, he drew on several of the British writers and publications mentioned above to support his case. In this respect, Stasov followed a practice common among Russian critics of mining foreign reviews of Russia’s displays and concentrating on the same objects that these discussed.

20 He cited

The Times in both of his articles, describing the very paintings its correspondent had praised in October 1862 (see above) as ‘notes’ from Russia’s ‘new music’ that had been welcomed in London.

21 He also quoted (albeit very loosely) from Taylor and Palgrave’s handbooks, highlighting Taylor’s disdain for contemporary history painting and Palgrave’s view that Russian painting was insufficiently distinct (though Stasov neglected to mention that Palgrave levied the same charge at other foreign schools—a cavalier use of sources that the Russian critic would later repeat).

22 So it was that mutually reinforcing narratives were selectively merged to promote socially committed genre scenes as the form of painting best suited to incubate a Russian artistic school.

23Where, though, did these critical frameworks leave the Russian paintings displayed in London that failed to toe the line? What space was there in a dominant discourse of national differentiation for works that self-consciously drew on pan-European as opposed to endemic traditions? Crucially, what was to be done with paintings that exuded innovation or even excellence in areas to which the kingmakers of a British school of painting had already laid claim? The fate of Russian history and portrait painting at the exhibition of 1862 offers an illuminating case study in this respect.

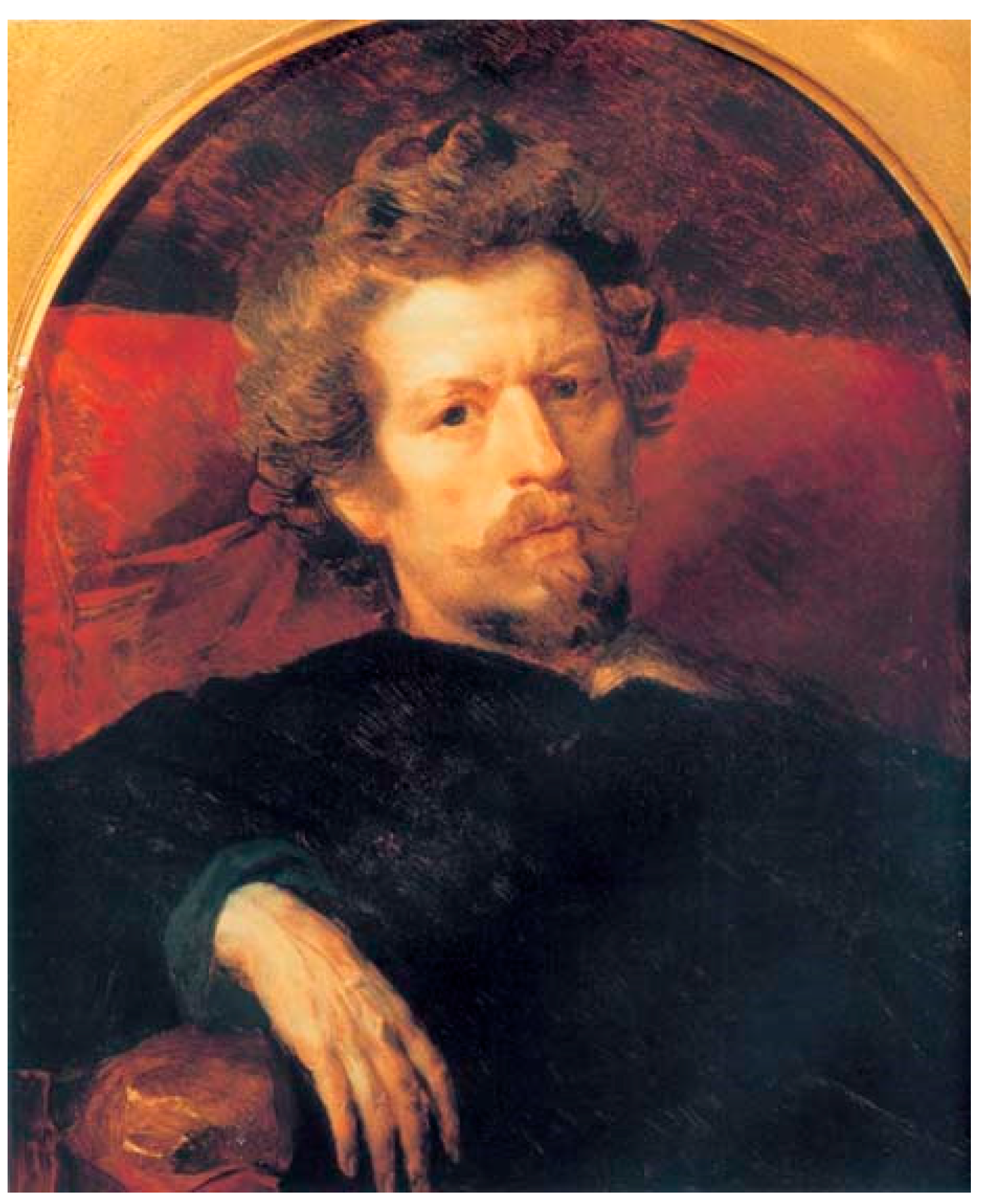

4. History Painting and the Bind of Familiarity

While genre and landscape scenes comprised nearly three quarters of the Russian pictures in London, history painting accounted for just ten works. For reasons that remain unclear, critics rarely bothered with the more recent examples, but occasionally alighted on earlier pictures, such as Anton Losenko’s

St Andrew the First-Called (1764), Fedor Bruni’s

Jesus Christ at Gethsemane (now known as The Gethsemane Prayer, 1834–36), and Alexander Ivanov’s

Appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene (

Figure 3, 1835: all State Russian Museum, St Petersburg). Bruni and Ivanov’s paintings doubtless attracted particular attention as they were given pride of place in the middle of the hang, as Timm’s lithograph attests (see

Figure 2).

As we have come to expect, western European precedent framed the discussion of these pictures. For

The Times’ correspondent, Bruni’s

Christ at Gethsemane ‘looks like secondhand work of the Caracci school’, while Ivanov’s painting ‘will be classed here as a tame picture of the German academic class, but is workmanlike’ (

Pictures of the International Exhibition 1862, p. 3). Taylor similarly deemed Bruni’s

Christ at Gethsemane ‘a clever imitation of the Caracci [sic] in colour and sentiment’, while the artist’s second exhibit, of a Virgin and child, was ‘a curious

pasticcio, in which influences of the modern German art of Dresden are mingled with those of the school of Raphael […] and the two engrafted on the Russian stem.’ Ivanov’s painting, for its part, was ‘a large but tame picture, showing influences of the schools of Overbeck and Hubner [sic]’ (

Taylor 1862, p. 196). The German Johann Friedrich Overbeck was widely known at the time for founding the Nazarene art movement. ‘Hubner’, meanwhile, was almost certainly Rudolf Hübner, a history painter and exponent of the Düsseldorf school.

Taylor was not wrong in drawing these comparisons, as the western European artists he mentioned were routinely studied by Russian painters on their cultural pilgrimages to Italy. It was a matter of honour to pause in Dresden to marvel at Raphael’s

Sistine Madonna (c. 1513–14, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden) (see

Bori 1985, pp. 105–32). As long-term residents in Rome, Bruni and Ivanov knew Annibale Carracci’s frescoes in the Palazzo Farnese. Ivanov was also close to the Nazarenes and made careful note of their comments on his paintings. He particularly admired the way in which Overbeck’s paintings embodied fervently-held religious beliefs and claimed to value Overbeck’s opinion more than that of any other artist.

24 ‘Overbeck the hermit prays, prays in his paintings’, he wrote after seeing

The Triumph of Religion in the Arts (1829–40, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main), a vast canvas on which the German artist worked for more than a decade (

Botkin 1880, p. 46). The socially reticent Ivanov even attended a raucous leaving party for Pieter von Cornelius and depicted Cornelius and Overbeck in his watercolour

A Ponte Molle (1842, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg), a sketch for which confirms the identities of these two artists in Ivanov’s own hand.

25 It was, therefore, no small wonder that Taylor identified similarities between their work. Ivanov’s

Appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene testifies to the way in which he shared the Nazarenes’ preoccupation with devotional painting, their investment in the emotional state of biblical figures, and their admiration for the richly hued colours of the Italian ‘primitives’, evident here in the deep ochre tones of Mary’s robe.

Yet these connections were only ever framed by British critics as derivative, rather than creative engagements with mutable traditions that evolved in different ways. Nor did the British observers bother to consider the moments of distinction in the Russian paintings, despite the fact that Ivanov’s picture especially was far from a routine echo of western paragons. He eschewed the standard academic practice of devising a background that would supplement the main narrative of his painting, giving instead a mere glimpse of sunlit vegetation within the sepulchral envelope of trees. The commanding planimetric staging of Mary and Jesus’s encounter and the deft choreography of their hands was equally Ivanov’s own. Yet such agility passed without comment. No matter that Ivanov and Bruni were highly educated artists who enjoyed imperial patronage and lived extensively abroad (in Ivanov’s case, for twenty-eight years), or that Ivanov’s anti-establishment views challenged any characterisation of him as a fawning disciple. The British interlocutors were incapable of moving beyond a western-centric construct of leader and follower in ways that would have enabled them to assess Russian painting on its own terms.

In surfacing these monodirectional narratives and the simultaneous mechanisms of dismissal and othering at play, it is useful to consider Natalia Majluf’s discussion of Latin American artists as ‘marginal cosmopolitans’ at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. As Majluf writes:

Latin American art has always been received with ambiguity and unease in international contexts. The crucial site of contention centers invariably on the status of a Latin American identity, or of where and how a specifically Latin American difference can be found. In fact, since the nineteenth century, Latin American art has been subjected to a deceptively simple critical strategy: in order to be acceptable in international circles, Latin American art must be made different, for when found to be familiar, it is defined as derivative. In either case artists from Latin America are effectively placed on the margins—outside or beneath the culture of the West.

The same could be said of Russia’s history painters in 1862, the ‘familiarity’ of whose work led British commentators to saddle them implicitly with the label of uncritical sycophants. These observers struggled to find value in the depictions of canonical and frequently painted biblical figures and narratives, not least as these did not confirm Russia’s otherness or allow for the perpetuation of widely shared stereotypes. The British writers had neither the knowledge nor the rhetorical tools to move beyond hierarchies of comparison that unfailingly placed Russian history painters on a lower rung. For now, Russian participation in a dialogic, pan-European process that openly drew on historic as well as modern example remained unexplored.

5. Undermining the Primacy of the British School

If the reception of narrative pictures in 1862 reveals the extent to which the representation of biblical subjects in Russian painting had to be framed as derivative, the stylistic agility in Russian portraiture was equally difficult for British critics to comprehend. Comprising seventeen works, portraiture accounted for nearly a fifth of the pictures in the Russian section. Of these, almost a third were paintings and drawings by someone listed in the catalogue of the Russian pictures as ‘Axenfeld’—one of only three painters not given a first name in this section, but almost certainly the now little-known Jewish artist Heinrich Axenfeld (1824–92) who had already spent many years in France and would acquire French citizenship in 1878. The list of his works included a drawing of a burgomaster after Rembrandt and a copy of Bonington’s history painting

Francis I, Charles V and the Duchess of Étampes (c. 1827, Louvre, Paris: erroneously titled in the catalogue ‘Frances and Charles I. at the Duchess D’Etampes’) (

Catalogue of the Russian Section 1862, p. 119). The charge of unreflexive copying that was repeatedly aimed at the Russian display might here have been well deserved.

But the remaining portraits included several that were no bland simulacrum of a western prototype. Among them were three of a series of seven portraits that the Ukrainian artist Dmytro Levytskyi / Dmitry Levitsky painted of students at the Smolny Institute, the elite girls boarding school founded in St Petersburg in 1764 (1772–76, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg). (As Levitsky used the Russianized spelling of his name during the period when he was producing these paintings and was identified as Levitsky—or Levitzky—in printed sources in 1862, that version will be used here.) These were joined by the serf-born artist Orest Kiprensky’s portrait of his foster father Adam Shvalbe (1804, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg) and a self-portrait by the first Russian painter to achieve fame in western Europe, Karl Briullov (1848, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow). Consideration of these works suggests that, had critics been wise to the blinkered preoccupation with nationalism and the territorialism of the British school that dominated artistic discourse in 1862, they might have been more alert to the compositional and painterly qualities of earlier Russian art.

The Smolny portraits by Levitsky that were exhibited in London were those of Natalia Borshcheva, Glafira Alymova, and Ekaterina Molchanova. Like all the paintings in the series, these registered the skills that girls acquired at a school which gave them precious space to study and mature away from the strictures that early marriage imposed (the legal age for girls to marry was twelve when Levitsky painted these works). Those of Borshcheva dancing (

Figure 4) and Alymova playing the harp (

Figure 5) pointed to the standard accomplishments expected of well-born women, while Molchanova was placed beside a vacuum pump to allude to scientific pursuit (

Figure 6)—an endeavour taken so seriously at the Smolny Institute that by 1825, the wife of the Minister Plenipotentiary from Britain to Russia was marvelling at how much science the girls were taught.

26In some respects, these compositions adhered to established pictorial tradition. The portrait of Alymova evinced the cultural association between women and music which drew on the figure and iconography of St Cecilia, the patron saint of music, and had gained currency in European painting from the late sixteenth century.

27 Meanwhile, Molchanova’s portrait extended the practice popular in eighteenth-century France of suggesting an interest in natural sciences by painting women alongside scientific equipment. Taylor, among other critics, acknowledged Levitsky’s self-positioning in these traditions when he wrote: ‘Catherine Moltchanoff seems to have been a

savante, by the electrical machine placed near her; and Glaphyra Alymoff, by the harp she plays on, must have been a musician or singer. These portraits are painted in a very workman-like style, and are not inferior to the average of contemporary Court-painter’s work in Paris and London’ [sic] (

Taylor 1862, p. 195).

But Levitsky deviated from established practice in the vivacity of his poses, which intimated the joys of girlhood and adolescence in ways that had no equal at the time these pictures were produced. The performative and carefree demeanour of their subjects had certainly yet to be painted in Britain, where such behaviour was frowned on as ‘unfeminine’ and ran the risk of invoking the lax morality of dancers and actresses. Such connotations would only later gain traction in Russia, where the profession of actress was relatively young in the period when Levitsky was working. Unencumbered by the negative associations that appended to balletic or performative poses in western Europe, he was able to pioneer forms of female physicality that embodied the exuberance and promise of young women on the threshold of an adult world.

28Kiprensky and Briullov’s portraits similarly defied classification within rigid western categories and certainly within the academic traditions in which both artists had been trained. Kiprensky’s portrait of his foster father sacrificed the legibility offered by solid form and line to delve instead into the physical properties of paint (

Figure 7). Crafted in a barely differentiated palette of dark brown and flesh tones and with minimal signifiers of personal identity, the portrait shows the artist to be an honourable descendent but no imitator of Rembrandt and Van Dyck, to both of whom he was compared.

29 Like Rembrandt especially, he buries detail in passages of obscurity, but goes further than his illustrious predecessor in merging body with background to deny the viewer any sense of spatial recession.

Briullov, by contrast, maintained a delineation between figure and setting in his self-portrait, but, like Kiprensky, gave scant indication of sartorial detail or anatomical form and deployed a compressed, almost claustrophobic perspective, with little by way of background space (

Figure 8). Even allowing for the unfinished nature of the portrait, he clearly eschewed the classic academic practice of careful, elided brushstrokes in favour of a bold, imprecise approach, perhaps reflecting the effects of the illness that was sapping his energies at the time. The structure of the artist’s hand resting on the arm of the chair draws especial attention to its own materiality, anticipating the modernist strategy whereby intersecting brushwork provides glimpses of bare canvas to emphasise the surface of the support. In avoiding academism and naturalism alike, both portraits refused the polarity that invariably structured the responses to the artistic displays of 1862.

The more innovative aspects of Levitsky, Kiprensky, and Briullov’s works beg the question as to why they received so little notice in London. I would like to suggest that this lay in the threat these could have posed to the notion of British painting as the nonpareil of a national school. With their agile, demonstrative poses, Levitsky’s Smolny portraits anticipated rather than followed developments in Britain, upending the narrative that positioned British artists as trailblazers and Russian artists as acolytes. It was not until 1782 that Gainsborough attempted comparable liveliness to that of Levitsky in his Portrait of Giovanna Baccelli (1782, Tate, London), but even then, his subject actually was a dancer, which accounted for the atypical pose. The depiction of scientific equipment in Molchanova’s portrait of 1776 likewise challenged any claim for ingenuity on the part of Reynolds or Romney when they deployed similar attributes in their portraits of the 1770s and 1780s. Meanwhile, the unconventional execution and compressed spatial registers of Kiprensky and Briullov’s paintings resisted any suggestion that these were mere epigones, demonstrating an exploration of facture and composition as noteworthy as any in British portraits of the time.

This is not to say that Russian artists were immune to British example, as Fedotov’s well-known emulation of Hogarth exemplifies (see

Gray 2001, pp. 23–30;

Stepanova 2014, pp. 118–33). But the paintings by Levitsky, Kiprensky, and Briullov gave British artists a run for their money in affirming portraiture to be creatively generative terrain. For all his antipathy towards academic painting, Stasov was a rare observer to recognise this. For him, the Russian school was closest in character to English painting, as both had asserted their independence first in portraiture, then in the way in which Hogarth, Fedotov, and their successors portrayed the idiosyncrasies of daily life (

Stasov 1937b, pp. 54–55). What is more, he put aside his usual preoccupation with socially responsive content to commend the Russian portraits as equal to their British counterparts.

30 Indeed, Stasov recognised the ‘beauty of form and colour’ in the eighteenth-century British and Russian portraits, though he went on to damn the ‘high-minded arrogance’ and ‘indulgence’ that caused them to neglect the ‘comprehensive truth’ and ‘artlessness of simple life.’ He even registered the spatial innovation in the portrait of Kiprensky’s foster father along with that in Levitsky’s portrait of his father, also exhibited in 1862, when he stated that: ‘modestly looking out of their frames’, these were ‘an exception to the general rule, as rare as they are amazing in talent’ (

Stasov 1937b, pp. 54–55). These comments confirm a more nuanced aesthetic appreciation on the part of the inveterate campaigner for social realism than has often been claimed.

The irony is that it was Russia’s academic portraitists who proved less conformist at the International Exhibition of 1862, contravening the category of ‘unadventurous and retrograde’ that western, and especially British, critics had constructed for them. By contrast, recent genre painters were arguably the

more conventional by veering towards the national aspiration that this most establishment of events required. Such was the force of this dictate that, however imaginative their compositions or brushwork, Russia’s history and portrait painters were largely disregarded for failing to satisfy the clarion cry for national distinctiveness in art. Telling here is Taylor’s damning comment that, ‘Whatever hope there may be for Russian art in the future, rests on work founded upon the life and history of Russia, not on the ambitious academic compositions of Bruloff, Bruni, and Ivanoff. By virtue of the latter, Russia can only take her place in the rear of the academic art of Europe. By the production of a really national school, she may yet conquer a rank in art for herself’ (

Taylor 1862, pp. 197–98). The emphatic prioritisation of national content left formally inventive paintings in the shade, especially if that inventiveness mounted a challenge to the fundaments of the British school.

One might even speculate that the critical neglect of the formal properties of the pictures that represented Russia in 1862 set the pattern of foregrounding anecdotal incident at the expense of stylistic innovation that characterised western engagement with Russian art for decades. However powerful the formal resolutions of later nineteenth-century artists, from the immersive brushwork of Ilia Repin and the raked perspectives of Elena Polenova to the fragmented forms of Mikhail Vrubel and the bold contours and shapes of Valentin Serov’s more radical portraits, western viewers invariably focused on narrative content rather than technique. This one-sided account found firm footing in the historical record, making it that much easier for the lionisation of the avant-garde to take hold.

6. Epilogue

In the years that followed the 1862 exhibition, British commentators began to take note of Russia’s artistic progress. In 1867, Thomas Archer, Director of the Edinburgh Museum of Sciences and Arts, visited the Exposition Universelle in Paris as part of the British government’s fact-finding mission. Having already travelled to Russia, Archer was better qualified than many to comment on Russian art and, in an article devoted to the subject, waxed lyrical on the maturation evident from the display:

Self-conceit and a certain amount of superciliousness are national as well as individual weaknesses; hence it is not much to be wondered at, that the French, as well as other nations, saw with surprise a people whom they had thought proper to assume to be only semi-civilised, developing such indications of true Art and cultivated taste at the Exposition Universelle, as at once proved them to be greatly in advance of more pretentious nations. It was seen unmistakably that Russia has a true school of Art, essentially national, and like that of the Latin race, essentially of religious origin.

This success was not, Archer insisted, because the Russian government had taken excessive measures to impress at the exhibitions in London and Paris, or relied on ‘the treasures of the Tsar […] to show that his country was more advanced than the rest of Europe chose to imagine.’ Rather, Archer’s knowledge of collections and manufactories within Russia convinced him ‘that the works exhibited were not exceptional in any respect, but fairly represented the Art-energies of the country.’ While stating that there were better paintings and sculptures in St Petersburg than those sent to Paris, he nonetheless maintained that ‘enough was shewn [sic] to prove that there is not only one genius but a national school’ and that ‘other nations may greatly benefit by the Art-treasures of that country becoming more fully and widely known’ (

Archer 1868, pp. 116–18). This would soon be the case, as some of the Russian items exhibited in Paris were purchased for the South Kensington Museum in London, whose pioneering collection of art and design had been launched (initially in its predecessor, the Museum of Ornamental Manufactures) with the education of young artists and designers very much in mind (

Hardiman 2018, pp. 1006–15;

Hardiman 2014, pp. 50–81).

By the time of the four annual exhibitions that took place in London from 1871 to 1874, Archer’s sense of Russia’s artistic advancement was acquiring wider currency. While Russian art was not included at the first of these, such was its impact at the second in 1872 that, according to Stasov, a ‘whole crowd of London journals announced in one voice that Russian art has overtaken all of the other schools at the current exhibition, and has impressed and astonished everyone who understands anything at all about art’ (

Stasov 1952, p. 219).

Unlike the national structure of the earlier exhibitions, submissions to these London events were combined and displayed under the headings of ‘Fine Arts’, ‘Manufacturers’, and ‘Recent Scientific Inventions and New Discoveries of All Types’ (

Dibello 1990, p. 45). This arrangement inevitably diluted the impact of individual national displays, but Russian art still made its mark. Paintings from Vasily Vereshchagin’s Turkestan series caused a sensation in 1872 as well as 1873, when he held his first ever one-man show at the Crystal Palace (which by now had been relocated from Hyde Park to Sydenham Hill in south-east London) (

Chernysheva 2014). An article in

The Art-Journal on the sculpture section of 1872 also noted Russian models and bronzes that were ‘remarkable for their spirit and nationality’ and commended Mark Antokolsky, a sculptor of Lithuanian–Jewish descent, for ‘sacrificing everything to character and emotion’ in his bronze statue of Tsar Ivan IV. Lieberich was again singled out, as was Klodt, of whom this critic wrote: ‘Extraordinary life and spirit are shown in this gentleman’s studies of horses, and other works by his hand’ (

The International Exhibition 1872, p. 249). The ekphrasis of Antokolsky’s sculpture along with commendation of his peers confirmed the status that British critics now accorded to Russian artists.

Yet this acclamation in no way augured a consistent upward trajectory of British acceptance and appreciation. On the contrary, when, in 1873, Atkinson published

An Art Tour to Russia, one of the earliest and certainly the most substantial English-language book to date on Russian art, he continued to typecast Russia as a benighted country of backward development and regularly invoked ‘the still barbaric state of Russian art’.

32 To be sure, he praised specific works, including several that had been exhibited in London in 1851 and 1862, among them Levitsky’s portrait of Alymova.

33 But twenty-two years after the Great Exhibition and over a decade since its successor in 1862, Russian art was still pilloried for its derivativeness. ‘[T]he constituent materials […] have been collected from all the capitals of Europe, and for this reason the art which obtains currency is but too often a confused compilation, a jargon of many tongues’ (

Atkinson [1873] 1986, p. 132). Russian sculptors were pitied for the ‘misfortune’ that ‘they seldom succeed in establishing an independent individuality or a distinctive nationality’ (

Atkinson [1873] 1986, p. 20). Levitsky was dismissed as a clone of British portraitists—an accusation underpinned by the erroneous claim that he ‘was said to have formed his style in England, under the influence of Reynolds’.

34 In sum, for Atkinson, ‘Russia is in art still a desert land, producing, save in some few favoured spots, little that can by utmost courtesy rank as fine art’ (

Atkinson [1873] 1986, p. 254).

This classic freewheeling text—the only wide-ranging account available to English-language readers for some time—served to entrench views that Russian art lagged behind western Europe and should rely on naturalism if it was to triumph. ‘[T]he hope of the Russian school does not lie in the direction of the ideal, but in the true and literal transcript of nature’, Atkinson averred (

Atkinson [1873] 1986, p. 168). So it was that the key apprehensions and misapprehensions of 1862 prevailed, with writers refusing to allow for a multiplicity of experience and intent on the part of imperial Russian painters, and insisting that Russia’s route to artistic redemption lay in naturalistic depiction alone. Insufficiently distinctive and insufficiently ‘Russian’, the artists had, apparently, no choice but to turn to topics of local interest to engender an identity of their own. In light of this, it is not surprising that the supposed supremacy of the avant-garde found a strong foothold in critical and popular understanding alike. The pigeonholing of imperial Russian artists that disregarded any earlier formal invention took root in the western imaginary from 1862 and created fertile ground for the putative exceptionalism of the avant-garde to thrive.