Abstract

This article explores the official exhibition of Austrian art held in May 1930 at The Society for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in Warsaw. Showcasing 474 artworks by 100 artists, the exhibition spanned the years 1918–1930, a period marked by Austria’s efforts to overcome post-war political isolation. The article examines the exhibition’s rhetoric and its critical reception in Warsaw within the broader context of Polish–Austrian diplomatic relations, influenced by Austria’s challenging political and economic situation and the priorities of the Second Polish Republic. The introductory essay in the exhibition catalogue, authored by Hans Tietze, emphasized Vienna’s seminal role as a cultural center at the crossroads of European artistic trends. This approach aligned with the cultural diplomacy of Johannes Schober’s government, which aimed to underscore a rhetoric of openness to the cultures of other nations, particularly the successors of the Habsburg Empire. This contrasted with the later identity policy of the Bundesstaat Österreich, which elevated Tyrol as emblematic of the core German–Austrian identity constructed in the new state. The analysis reveals that the exhibition represented the peak of Polish–Austrian cultural relations during the interwar years, suggesting the potential for broader engagement. However, this potential was short-lived, ultimately thwarted by the Anschluss of Austria to Germany in 1938.

1. Introduction

The main title of the article is a quote from Hans Tietze, a renowned art historian and critic, who described post-imperial Austria’s position on the geocultural map of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s as a unique crossroads of cultural trends. I refer to this statement because the following text is dedicated to the official exhibition of Austrian art that took place in Warsaw in 1930, in which Tietze participated as a commentator on both the Habsburg-era cultural domain and the contemporary art scene in Austria. I consider this exhibition a particularly significant case to investigate because it allows us to trace the development of Polish–Austrian cultural relations after the historical turning point of 1918. Moreover, it exemplifies the shifts in the cultural policy of the new Austria in correlation with the changing conditions on the state’s political scene.

The primary focus of the discussion in this article is on the implicit criteria and assumptions that governed the selection of visual material for display and the mode of presentation of the Austrian art world. I aim to answer the following questions: How inclusive was the exhibition’s scenario, and what were its biases? What was the rationale behind the formula chosen for the Warsaw display? What was the critical reception of the exhibition? Analyzing the reviews of the event will serve as a litmus test for the effectiveness of the adopted curatorial strategy in relation to the aims of the exhibition organizers and Austria’s diplomatic agenda during this period. Exploring the critical response will also reveal the artistic priorities and sensitivities of Polish critics.

2. An Overview of Polish Presence in Vienna

Austria was one of the three powers, alongside Russia and Prussia, that successively partitioned the territory of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, 1793, and 1795, leading to the complete loss of Polish sovereignty. Nevertheless, despite the political and economic subjugation of the Austrian partition under Habsburg rule, the splendor of Vienna attracted Poles no less than that of Rome, Paris, or Munich. In this respect, it is worth emphasizing that the Poles made a significant contribution to the political culture and artistic life of the Habsburg capital (Forst-Battaglia 1983; Buszko 1996; Taborski 2001, pp. 66–115; Kucharski 2001; Pesendorfer and Fischer 2002; Cwanek-Florek 2006). Polish nationals held high positions at the imperial court and, from 1867 onwards, took up important ministerial posts, including Prime Minister (Agenor Gołuchowski Senior, Alfred Potocki, and Kazimierz Badeni) and Ministers of the Interior, Finance, Foreign Affairs, Agriculture, Railway, as well as Religious Affairs and Education. From 1871 to 1918, Poles were continuously appointed as Ministers for Galicia. They also ascended military ranks, participated in parliamentary work, engaged actively in public life, and were involved in industrial and commercial ventures. Additionally, they were part of the capital’s social, financial, legal, intellectual, and artistic elites. They published articles in both the German- and Polish-language press, and established Polish political, economic, and educational associations and organizations. Aristocrats residing in the capital city on the Danube—such as Józef Maksymilian Ossoliński (director of the Imperial Court Library), the Czartoryskis, the Lanckorońskis, the Potockis, the Lubomirskis, the Dzieduszyckis, the Madeyskis, the Gołuchowskis, the Badenis, and the Bilińskis—made significant contributions to the rich, multiethnic culture of the Habsburg Empire’s capital by providing artistic patronage, running artistic salons, hosting artists, collecting artworks, and organizing concerts and theatrical performances (Taborski 2001, pp. 52–65; Forst Battaglia 2014, pp. 165, 167–73; Cwanek-Florek 2014, p. 275).

Considered a major musical center of Europe, Vienna was visited by prominent Polish and Polish–Jewish composers and virtuosos such as Henryk Wieniawski, Mieczysław Karłowicz, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Karol Szymanowski, Ignacy Friedman, Artur Rubinstein, and Bronisław Hubermann (Forst Battaglia 1989, p. 238). The metropolis on the Danube also hosted a plethora of eminent Polish writers, poets, and playwrights, including Franciszek Karpiński, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Maria Konopnicka, and Stanisław Przybyszewski. Vienna was where Tadeusz Rittner, born to a Polish–Austrian family, pursued his career as a writer, playwright, and publicist (Forst Battaglia 2014, pp. 170–71).

Outstanding painters who studied or temporarily stayed in Vienna in the 19th century included late Romantics such as Artur Grottger, Henryk Rodakowski, Leopold Löffler, Franciszek Tepa, and Aleksander Kotsis (the last three studied under Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller), and representatives of the younger generation like Włodzimierz Tetmajer, Józef Mehoffer, and Henryk Gotlib (Taborski 2001, pp. 141–46; Forst Battaglia 2014, pp. 173–74). Jan Matejko (1838–1893), the world-renowned author of the monumental historical painting Jan III Sobieski at Vienna (1882–1883), which was displayed in Vienna on 12 September 1883 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the victory of the Polish and Imperial armies over the Ottoman Empire, often exhibited his works in Vienna and was awarded the Literis et Artibus medal by Emperor Franz Joseph. Portraitists Tadeusz and Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz, Wojciech Kossak, Henryk Rauchinger, Kazimierz Pochwalski (professor at the Akademie der bildenden Künste), and his student Bolesław Jan Czedekowski enjoyed great popularity with the court, and the aristocratic, political, and social circles of the Austrian capital (Cwanek-Florek 2014, pp. 271–72). Stanisław Roman Lewandowski was a sculptor who permanently lived in Vienna and wrote accounts of the city’s cultural life for the Polish press.

The late 19th century saw numerous exhibitions of Polish art in Vienna as a result of cooperation between two art associations founded in 1897: the Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs–Wiener Secession and the Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich ‘Sztuka’ (Sztuka Society of Polish Artists) (Cavanaugh 2000). Until 1918, the Sztuka Society was the main intermediary link between the artistic milieus in Vienna and the two main cultural centers in the Crownland of Galicia—Cracow and L’viv (the administrative capital of the Austrian partition of Poland). The society embraced selected Polish artists from all three partitions to enable the presentation of Polish art at different venues of the ‘domestic’ (strictly speaking, cross-frontier) and international art scenes as a national brand, rather than under the aegis of the three ruling powers.1 Given the focus of this article on Polish–Austrian artistic relations after 1918, it is noteworthy that several adherents of ‘Sztuka’ were members of the Wiener Secession and the Hagenbund (Bisanz 1980, pp. 29–41; Cavanaugh 1987, pp. 79–98; Krzysztofowicz-Kozakowska 2006, pp. 218–59; Brzyski 2011, pp. 4–16; Kudelska 2015, pp. 307–16). In fact, ‘Sztuka’ maintained more intensive and successful contacts with Viennese exhibiting institutions than with any other comparable organizations in Berlin, Brussels, Munich, Paris, or Saint Petersburg.

Although the activity of ‘Sztuka’ showed signs of decline in the interwar decades (the association disbanded in 1950), Polish cultural bonds with the Austrian successor of the kaiserlich-königlich monarchy proved to be durable, and the society played an important role in maintaining these ties during the 1920s and 1930s. Other organizations also contributed to this continued exchange between the wars. In both 1927 and 1928, the Towarzystwo Szerzenia Sztuki Polskiej wśród Obcych (Society for the Promotion of Polish Art among Foreigners) mounted an extensive display of Polish art in Vienna (Nowakowska-Sito 2001, p. 146). In return, on 10 May 1930, an exhibition of Austrian art was opened at the premises of the Towarzystwo Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych (the Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts, hereafter referred to as Zachęta) in Warsaw (Treter 1930, p. 237).2

An equally noteworthy research context for the 1930 Warsaw exhibition is the phenomenon of cultural diplomacy. This developed intensively on the European continent during the interwar period and was seen as a useful soft power instrument subordinated to political and economic goals (Nye 2004; Chitty 2017). Self-promotional strategies pursued by the governmental agencies of the newly established nation-states in Central Europe represented an important cultural factor that remains significantly under-researched in contemporary art historiography. Although scholarly interest in the interwar art scenes of this region is growing, there remains a notable gap in examining the touring art exhibitions exported by particular Central European states and circulated throughout the continent. The dynamics of showcasing visual arts across geopolitical borders fostered a dense network of cultural exchange between major centers and peripheral localities. Organized through bilateral and multilateral international agreements between relevant institutions, traveling exhibitions were emblematic of the official cultural policies of political entities and acted as a means of soft power diplomacy, primarily highlighting national distinctiveness. During the 1920s and 1930s, identity themes and the unique cultural characteristics of individual nations were central to both curatorial practices and critical discourses (Kossowska 2017, pp. 67–318).

At this point, a short outline of the political situation in post-war Austria and the resulting relationships between Austria and the Second Polish Republic will elucidate several aspects of the self-presentation strategy adopted by the organizers of the 1930 Warsaw exhibition.

3. Polish–Austrian Political Relations until the 1930s

Resulting from the defeat of Austria–Hungary during World War I, the collapse of the Habsburg Empire led to a fundamental reconfiguration of the political map of Central Europe. Several nations formerly subordinated to the monarchy—such as Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, and the previously privileged Hungarians—gained sovereignty within the boundaries of multiethnic political entities. Austria, however, with its diminished territory and weakened economy, counted post-war losses (Kozeński 1970, p. 144). From a multinational power with a dual legal and administrative system, it transformed into a small and politically insignificant country. Nevertheless, the newly constituted Austrian state strove to gain a new position on the reshaped political stage of the continent and strengthen its connections within the European cultural circuit (Batowski 1982). By deploying soft power tools, Austrian policymakers sought to end the international isolation in which the country found itself as a defeated power. Austrian artistic milieus aimed to revive the key role Vienna had played as a cultural center before the war, attracting artists of various nationalities from both within and beyond the Empire, almost as strongly as Paris, Berlin, and Munich (Clegg 2006, pp. 9–26, 225–31; Husslein-Arco et al. 2014; Chrastek 2016).

It was in the interest of the newly constituted Second Polish Republic, following the end of the Great War, to uphold the provisions of the Peace Treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. These treaties defined the political status of Deutschöstereich (German-Austria, renamed Republik Österreich in October 1919), specifically prohibiting Austria’s accession to the German Reich (Wereszycki 1986, p. 289; Balcerzak 1974, pp. 187–213; Balcerzak 1992, pp. 103–20). For Poland, as one of the victorious powers, the consolidation of the Versailles system on the continent was essential for ensuring political sovereignty and future economic development. Despite Austria’s dire economic situation, a sovereign Austrian Republic was deemed crucial by Polish authorities for maintaining the new political order in Central Europe (Balcerzak 1974, p. 149).3

Amidst economic crisis, territorial disputes with Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, border conflicts with Italy, and separatist movements in provinces bordering Switzerland and Germany (Tomkowski 2000, pp. 15–40), the idea of unification with Germany, favored by the Social Democrats and advocated by Austrian Pan-Germans, gained popularity in Austria (Kozeński 1970, pp. 52–71). However, a majority of Austrian society did not identify with the German nation and did not view Anschluss as a path to national unification (Kozeński 1967, p. 73). An alternative proposal—federation with the Danube states—Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Hungary—was also promoted, primarily by the Christian Social Party.4 Successive governments in Warsaw staunchly opposed both scenarios. Austria’s annexation by Germany posed a threat by potentially strengthening the Reich, which harbored revisionist ambitions towards Poland and could undermine the geopolitical stability established by the Versailles Settlement (Kozeński 1967, pp. 202–35). Conversely, the concept of federalism—a federation of politically autonomous Danubian states—was seen as a modern adaptation of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, regardless of whether the Habsburg dynasty would play a role in this arrangement. Thus, it was in Poland’s interest to support an autonomous Austrian Republic.

Maintaining proper political relations with the Second Polish Republic was also important for Austria, as Poland stood as France’s key ally in Eastern Europe and supported the political framework established by the Versailles Settlement. Additionally, post-imperial Austria was tied to Poland as a successor state in terms of post-war financial settlements and economic relations. Despite recurrent negative sentiments toward Poland, particularly concerning the Polish–German border (Kołodziejczyk 1978, pp. 61–90) perpetuated by the Anschluss-oriented Viennese press, successive governments in Vienna endeavored to normalize bilateral relations. Following the Social Democratic Party’s loss of power, which viewed Warsaw authorities as adversaries of Germany and proponents of nationalist tendencies, Polish–Austrian relations improved. Upon assuming power in 1920, the Christian Socials sought financial and economic assistance for the impoverished republic not only from Western powers but also from Central European countries, including Poland. Consequently, the first Polish–Austrian trade convention was signed in September 1922 (Balcerzak 1992, p. 107).

Economic relations were further strengthened when Chancellor Ignaz Seipel and Foreign Minister Alfred Grüneberger visited Warsaw in September 1923. The normalization of bilateral relations was solidified in April 1924 with Poland’s ratification of the peace treaty signed with Austria in Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1919. In April 1926, Polish Prime Minister Aleksander Skrzyński visited Vienna, which helped alleviate periodic tensions arising from anti-Polish sentiments among certain Austrian political factions. During this visit, a conciliation and arbitration treaty was signed in accordance with League of Nations standards. One of the outcomes of these diplomatic efforts was the revitalization of cultural relations (Balcerzak 1992, p. 109).

However, Polish governmental circles were keenly aware of the political tensions and conflicts between the Christian Socials and Social Democrats, which destabilized the political landscape in Austria and often revived the ever-recurring concept of Anschluss (Hoor 1966, p. 47; Kozeński 1970, pp. 72–90). A memorandum drafted by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in March 1929 unequivocally rejected both the Anschluss and the federalization of the Danube States, which could have restricted trade relations with Poland.5 Despite these challenges, bilateral relations improved under the government of Johannes Schober, who assumed leadership of the state in September 1929.

Under Schober, a non-partisan politician who opposed Austria’s accession to the German Reich, a favorable political climate for cultural exchange prevailed (Tomkowski 2000, pp. 15–40). Soft power instruments, such as exhibitions, were clearly intended to ease diplomatic tensions and sustain economic exchange between Poland and Austria. The Austrian art exhibition, inaugurated on 10 May 1930, took place at Zachęta, the leading national gallery for modern art at the time. The event was highly significant, underscored by the participation of Ignacy Mościcki, President of the Second Polish Republic, and officials from both Poland and Austria at the opening ceremony. On the Austrian side, the project was supported by Heinrich von Srbik, Minister of Education in Schober’s government and a prominent historian known for his advocacy of the theory of ‘gesamtdeutsche Geschichte’ (total German history).6 Central to his scholarship was the idea of uniting the German people, historically divided by Austro-Prussian and international conflicts, into a cohesive whole. This raises an intriguing question: did Srbik’s patronage influence the content of the exhibition, or did Schober’s efforts towards reconciliation with Poland take precedence?

It is reasonable to assume that any reflection of Srbik’s pan-Germanic and pro-Anschluss convictions in the exhibition scenario would have severely impacted its reception in Warsaw and had significant political repercussions. Importantly, Austrian cultural decision-makers had utilized export art exhibitions to promote the country’s apparently neutral political image as early as the Great War.7 Was this strategy also applied in Warsaw?

4. Hans Tietze’s Insights into Austrian Art

The main organizer of the event, the Ständige Delegation der Künstlervereinigungen (Permanent Delegation of Artists’ Associations), entrusted the role of the exhibition’s curator to Teodor Klotz-Dürrenbach (1890–1959), who also participated in the show with several oil paintings and prints. Monumental in scope and abundant in exhibits (474 works by 100 painters, sculptors, printmakers, and designers), the display presented art created between 1918 and 1930. Hans Tietze, a renowned art historian representing the Wiener Schule der Kunstgeschichte (Lachnit 2005, pp. 98–110; Wagner 2010, pp. 440–43; Marchi 2011, pp. i–xiii, 14–46), was an ideal candidate to introduce the Polish audience to the contemporary Austrian art world.

Tietze’s understanding of art history differed from the attitudes of historiographers who sought to find indigenous German roots in Austrian culture and promote German national identity. He modified the universalist theses of Alois Riegl’s cultural theory, placing artistic activity within social reality and maintaining a broad intellectual horizon that excluded nationalist views and the concept of Mitteleuropa—total German domination of Central Europe.8 Choosing Tietze as a guide to the contemporary Austrian art scene ensured a politically neutral overview of the exhibition, based on a scenario reflecting the multiethnic tradition of the Habsburg monarchy rather than the Germanic genealogy of Austrians.

Referring to the fact that the historical, cultural, and social ties among the nationally, ethnically, and religiously heterogeneous population of the Habsburg Empire left a lasting mark on society, Tietze stated the following in the introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue: “There appeared a type of Austrian who, being in fact German, [on the one hand] obliterated many of the rough qualities of their race through numerous relationships with foreigners; on the other hand, they enriched their character with many features acquired from them.” (Tietze 1930b, p. 5).

Influenced by Wilhelm Dilthey’s ‘descriptive psychology’ and Benedetto Croce’s idealistic philosophy, Tietze broadened the notion of Kunstwollen to encompass manifestations of social and cultural life seen from a historical perspective.9 Consequently, he assigned an active social role to art, perceiving it not only as a carrier of social and national content but also as a factor shaping social and national self-awareness (Tietze 1925a). However, the focal point of his theory, as developed in the treatise Die Methode der Kunstgeschichte (Tietze 1913), was the ‘psychic processes’ of individual creativity. Drawing on Dilthey’s hermeneutics (Dilthey 1996, p. 236), Tietze argued that “the intuitive study of the psyche proves once again to be an indispensable tool for the historian” (Tietze 1930b, p. 443).

Moreover, the Vienna theorist was actively engaged in the contemporary art scene, convinced that only personal experience with present-day art allows an art historian to effectively investigate the art of the past.10 In observance of the ‘evolutionary’ paradigm of art historical models promoted by Franz Wickoff and Alois Riegl, he presented domestic modern art as a continuation of the tradition of the Habsburg monarchy (Tietze 1930b, p. 5). Yet, in line with his interest in the psychology of artistic creation and its cultural context, he perceived contemporary artistic phenomena as manifestations of essential characterological traits of Austrian society. According to him, the psychological dispositions that distinguished Austrians included perseverance, sincerity, and kindness, as well as skepticism and a lack of determination to act; additionally, the absence of fanaticism and chauvinism were also significant (Tietze 1930b, p. 5). Consequently, Tietze regarded typically Austrian values, as incarnated in the visual arts, to be the “lightness and liberty of creativity, suppleness and grace that blur extreme contradictions” (Tietze 1930b, p. 6), regardless of the programmatic affiliations and aesthetic predispositions of particular artists. Simultaneously, he emphasized the lack of inclination towards theoretical reflection among Austrian artists, who focused primarily on creative practice while expressing a genuine joy of life.

Nevertheless, despite employing in-depth methodological knowledge in his theoretical writings,11 Tietze refrained from explaining to the Polish audience how typical Austrian mental features had been transposed into particular morphological qualities of artworks.12 While the importance he granted to the psychological exploration of individual artistic creativity in Methode der Kunstgeschichte was indispensable for the interpretation of a work of art, it was not sufficiently explanatory regarding the psychological portrayal of society as a whole.13 Evidently, he attached utmost importance to intuitive comprehension.

Most Warsaw critics adopted Tietze’s socio-psychological methodological approach to the exegesis of Austrian art. On one hand, they lacked detailed knowledge about contemporary artistic trends in post-war Austria; on the other hand, they might have already been familiar with Tietze’s views on artistic creativity and methods of its study, particularly his imperative to value the expressive aspects of art, its emotional content, and its social conditions, since Methode der Kunstgeschichte was employed in the Polish university curriculum as a textbook on historiographic research procedures during the interwar period. This was particularly true for Mieczysław Treter (1883–1943), an eminent aesthetician, art critic, exhibition curator, museologist, and art scene animator, who served as head of TOSSPO, the aforementioned organizer of the Polish presentations in Vienna. Treter developed his career in Warsaw but originated from the Lviv intellectual and academic milieus, which maintained numerous scientific and cultural contacts with Vienna (Kossowska 2024, pp. 155–86).

Treter pointed out that the ‘national soul’—encompassing psychological traits such as the “proverbial Viennese charm, cheerfulness, gentle carelessness, and sincere, captivating affirmation of life”—was distinctly manifested in the form of the exhibited works (Treter 1930, p. 238). Meanwhile, the critic Konrad Winkler, known for his avant-garde pedigree, described Austrians as follows: “Austrian Germans have little in common with the nature of the Germanic race; they are characterized by their cheerful and carefree disposition, coupled with prudence, diligence, a preference for order, and a genuine sense of beauty” (Winkler 1930a, p. 8).14 Winkler concluded that “these virtues were also reflected in art,” although he did not explore the validity of directly translating collective characterological features into morphological properties of artworks (Winkler 1930a, p. 8). Wacław Husarski summarized the Austrian artistic profile on display as “typically pleasant, harmonious, and tasteful, exhibiting moderation and susceptibility to conservatism, avoiding risky experiments while skillfully applying established values” (Husarski 1930, p. 239).15 Even Wiktor Podoski, critical of the artwork selection and exposition arrangement, acknowledged the ‘carefree cheerfulness’ evident in Austrian everyday objects. However, he refrained from identifying ‘distinctive racial features’ in Austrian painting (Podoski 1930a, p. 8).16

Notwithstanding the challenging-to-grasp uniqueness of Austrian culture due to its multiethnic society, Tietze, guiding the Warsaw audience through the intricacies of the domestic art scene, aimed to delineate the specificity of Austrian art in both semantic and morphological terms.

“Despite the fact that Austrian artists include representatives of foreign nations—Italians and Dutchmen, Northern Germans and Czechs, Poles and Hungarians, who settled permanently in Austria a long time ago—Austrian art remains independent and distinct. Even though it does not strive to develop its own idiosyncratic type at all cost, it can nevertheless leave its genuine mark on foreign influences,” argued the critic.(Tietze 1930b, p. 6)

Considering the multiculturalism typical of the Habsburg Empire and the ethnic mosaic of the First Austrian Republic, Tietze credited Austria with being the unifying force of artistic tendencies from various parts of the continent. Unlike many Central European followers of the Wiener Schule, who focused on the national idioms of universal Kunstwollen (Bakoš 2013, pp. 125–200), Tietze advocated for a statist concept—the definition of the cultural specificity of the state rather than the nation, thus avoiding the issue of the Germanic origins of Austrians.17

Referring to the post-war reorganization of Vienna’s museums, which he conducted himself, Tietze wrote the following: “Austria’s raison d’être has been and still is to be the cultural mediator between the North and the South, the East and the West [..], this remains the fundamental goal of our land” (Tietze 1923, p. 12).18 According to the Viennese theorist, a fully original and indigenously Austrian artistic idiom had not been formed; instead, what was created was a conglomerate of influences, a multicultural amalgam, which was covered with a raster of good taste and moderation. Tietze maintained that moderate realism and modest decorativeness were typically Austrian features displayed by such masters as the outstanding Baroque architect Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, the representative of the second generation of the Nazarenes, Moritz von Schwind, and the renowned academic Hans Makart.19 It would be difficult to uncritically comment on this opinion, based on the a priori assumption of the existence of aesthetic moderation in Austrian art. The monumentality of Fischer von Erlach’s classicizing Baroque, the complex narrative of Schwind’s multipart compositions, as well as the exuberant decorativeness and sensuality of Makart’s painting, do not confirm Tietze’s diagnosis.

Tietze considered Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1793–1865) (Howard 2006, pp. 38–39), the rebellious academic who meticulously observed nature and life in the provinces, to be a typical Viennese, “not an Austrian in the broader sense of the word” (Tietze 1930b, p. 6). As a subcategory of Austrianness, ‘Vienneseness’ was thus meant to connote the elaborate naturalism, pervasive narration, and aura of sentimentalism evoked by Waldmüller’s paintings, which exemplified the Biedermeier style adapted to bourgeois taste. The vast majority of participants in the Warsaw exhibition represented Vienna (as will be discussed further). Therefore, it is worth considering whether Tietze’s category of Vienneseness could be translated into contemporary art. Yes, it could be, in the sense that several contributors to the presentation at Zachęta depicted provincial landscapes and scenes of everyday life that were quite distinct from the Viennese metropolis. Although they differed significantly from Waldmüller’s detailed depictions of the domestic countryside, most of their works fell within the neorealist trend, demonstrating a thorough observation of the surrounding reality.20

A good exemplification of this creative stance can be found in the rural landscapes and rustic motifs painted softly and freely by Franz von Zülow (1883–1963) (e.g., Grain and Granary), whose insightful perception of nature was appreciated by Jan Kleczyński (Kleczyński 1930b, p. 18). Von Zülow had strong ties to Vienna; he was born there, received his artistic education, and became part of Gustav Klimt’s circle of acolytes. However, in the mid-1920s, he began seeking attractive painterly motifs in the countryside. The interconnection between Vienna, which remained the artistic center during the interwar period, and various regions of the country was thus brought to the fore in the Warsaw exhibition, in line with the national government’s policy of stimulating economic and cultural development in various regions of Austria (Secklehner 2021, pp. 204–5). Nevertheless, artists active in provincial centers, which Tietze considered representative of Austrian identity, were mostly omitted. Moreover, Tietze explained the concept of Austrian identity to the Warsaw audience in a very general manner.

5. The Turning Point of 1918

Although Tietze perceived contemporary Austrian culture as a continuation of the Habsburg tradition, the introduction of 1918 by the exhibition organizers, the Ständige Delegation der Künstlervereinigungen, served as a demarcation line in the Warsaw scenario. This was an attempt to depict interwar Austrian art not as an epilogue of turn-of-the-century Vienna, but as a manifestation of the reorientation process in Austrian culture. The deaths of Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), Egon Schiele (1890–1918), Koloman Moser (1868–1918), and Otto Wagner (1841–1918) in that same year marked the end of the innovative era and revolutionary ferment in Vienna’s artistic life (Vergo 1975; Schorske 1980; Varnedoe 1985). Consequently, the audience at the Zachęta gallery could not contemplate the works of Klimt and Schiele, nor the coloristically striking canvases of Albert Paris von Gütersloh (1887–1973) and the young Anton Faistauer (1887–1930), members of the Neukunstgruppe, a progressive artist league founded in 1909 by Schiele. Similarly, the works of Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980) and Max Oppenheimer (1885–1954), exemplary of the most radical formulas of early twentieth-century modernism, were not presented (Werkner 1986).21

In contrast, traditionalist trends dominated the exhibition. Notably, attitudes referring to past conventions of representation were already prevalent at the Kunstschau 1920, an exhibition held at the Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie in June 1920. This exhibition resonated well with conservative circles, even though it still featured works by pre-war avant-gardists such as Schiele, Moser, Klimt, and Franz Metzner (1870–1919). Adalbert Franz Seligmann noted the following in the Neue Freie Presse: “One sees no Cubists, no Futurists, no Kinetists, nor any of those expressionists who have entirely freed themselves from representation and seek to convey their feelings merely through abstract lines, planes, and colors” (AFS 1920, p. 3).

In Anton Faistauer’s book Neue Malerei in Österreich (Faistauer 1923), one can find reasons for departing from expressionist imagery, which the author associated with radicalism, leading to over-intellectualization and abstraction in painting. According to the author, susceptibility to excessively progressive artistic influences could result from the lack of a firmly rooted “Austrian” identity, a consequence of the multiplicity of ethnic groups and communities in the former empire (Clegg 2006, p. 231). Supposedly, the exclusion of expressionist idioms in favor of neorealist and neoclassicist exemplars in the Warsaw scenario was intended to demonstrate the state of social and moral stabilization in the ‘new Austria’ and to manifest new paradigms of Austrians’ national self-identification.22

As previously mentioned, most artists who participated in the exhibition were based in Vienna, while a few painters were connected with other centers such as Graz (Constantin Damianos, Leo Fellinger, Martha Elisabeth Fossel, Erich Hönig von Hönigsberg, Leo Scheu, Wilhelm Thöny, Franz Trenk, Rudolf Zelenka) and Klagenfurt (Max Bradaczek, Adolf Christl, Ernst Riederer). This selection of participants indicated that the exhibition was designed based on a centralist model that marginalized provincial centers, which, in fact, began to develop and strengthen after 1918. Due to the lack of documentation of the Warsaw event, which was supposedly destroyed during World War II, the rationale behind this decision remains unclear, especially concerning artists of non-avant-garde profiles who left ‘red Vienna’ in the post-war period to settle in the provinces (Gruber 1991).23 Yet, the reason for this decision by the organizer could have been either a simplification of logistics during the preparation of the show or financial limitations.24

One of the most powerful examples of the curatorial strategy of neglecting artistic circles outside Vienna, and of eliminating radical modernist trends, was the omission of works by artists belonging to the so-called Nötscher Kreis. The members of this group, formed in the picturesque Carinthian municipality of Nötsch in the Gailtal Valley, maintained relations with Schiele and Kokoschka, thus expanding the impact of expressionism. Although they retained a traditional thematic repertoire (figurative compositions, portraits, landscapes, and still lifes), painters such as Sebastian Isepp (1884–1954), Franz Wiegele (1887–1944), Anton Kolig (1886–1950), Anton Mahringer (1902–1974), Gerhart Frankl (1901–1965), and Arnold Clementschitsch (1887–1970) focused their attention on the expressive qualities of the pictorial matter. They employed sharp chromatic contrasts, shape-deforming contours, and texturally thickened color patches to reflect the artist’s mental state, primarily anxiety (Lachnit et al. 1998).

Considering the strategy adopted by the exhibition’s organizer, the exclusion of Herbert Boeckl (1894–1966), the most prominent representative of Austrian interwar modernism (Husslein-Arco et al. 2009, pp. 335–96), is not surprising. Boeckl, who came from Carinthia and was initially an adherent of the Nötscher Kreis, took Kokoschka’s impulsive manner of painting as a point of reference. His works from the early 1920s were distinguished by luminous reds clashing with blues and the tactile qualities of thick impastos. In the second half of the decade, Boeckl associated intense chromatic tones with the structural discipline of Paul Cézanne, whose works he saw in Berlin and Paris. Starting in 1928, Boeckl was active in Vienna, where he became so highly regarded that in 1934, he was offered and eagerly accepted a professorship at the Academy of Fine Arts. The absence of Boeckl’s works from the exhibition at Zachęta anticipated the marginalization of his artistic position in the second half of the 1930s, particularly under the National Socialist regime of Arthur Seyss-Inquart.

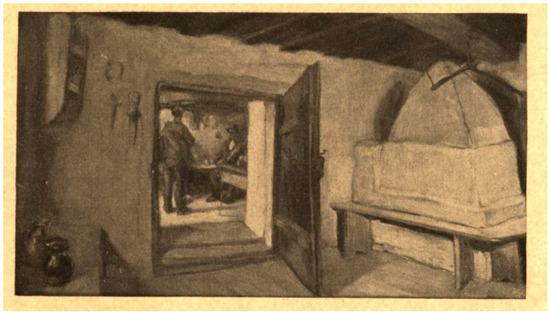

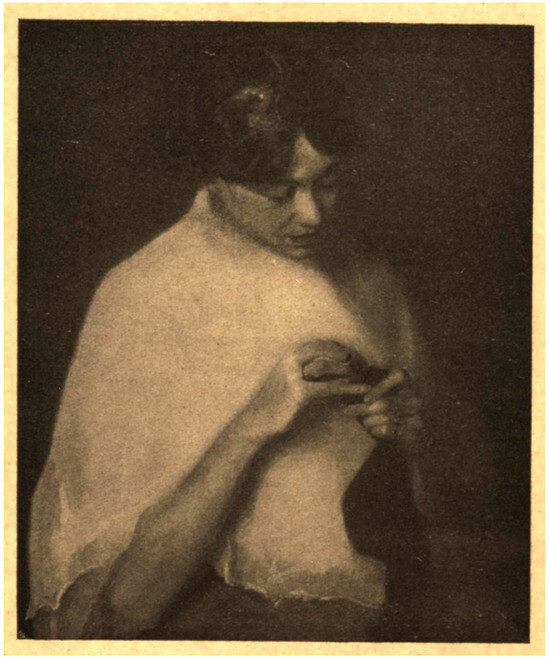

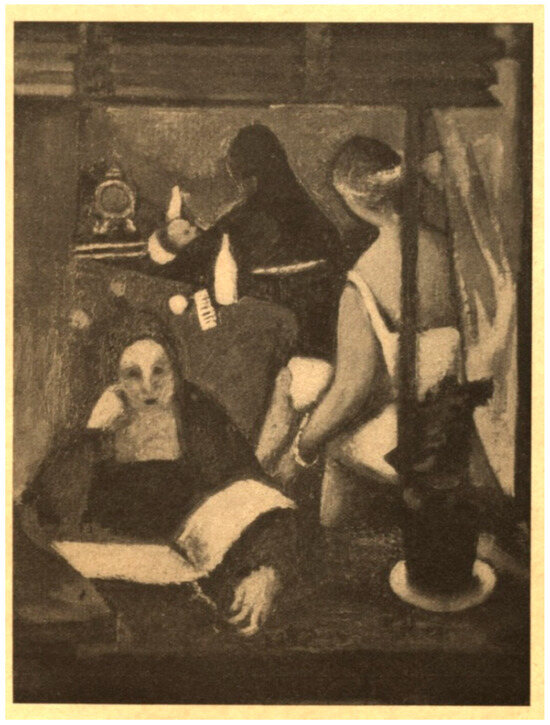

Although Tietze maintained that the qualities of contemporary Austrian art were “understandable when viewed from the point of view of its historical connection with the past” (Tietze 1930b, 5), he treated the past instrumentally, adapting its interpretation to the current cultural policy of the Republic of Austria, which adhered to traditional values. He did not consider the expressionist idioms of Schiele’s and Kokoschka’s associates, or Kineticism, which transposed the experiments of Cubism and Futurism,25 to be the distinctive features of twentieth-century Austrian art. Rather, he claimed that the distinctive feature lay in a moderate, decorative realism (Figure 1. Erwin Pachinger, Rustic Interior; Figure 2. Ernst Bucher, At Work). Consequently, the Cezannesque tectonics of composition and the expressionist treatment of visual form—features that shaped much of Austrian modernism during the interwar decades—were hardly apparent in the artistic material presented in Warsaw. This was due to the fact that, as Tietze explained, the main aesthetic category related to contemporary Austrian art was moderation.

Figure 1.

Erwin Pachinger, Rustic Interior, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

Figure 2.

Ernst Bucher, At Work, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

6. The Concept of Aesthetic Moderation

Polish reviewers noted various shades of moderate realism in portraiture, appreciating the ability to convey psychological truth alongside physiognomic mimetism (Siedlecki 1930, p. 239; Kleczyński 1930, p. 18). Jan Kleczyński listed several portraits that, in his opinion, met the criterion of objective observation, including Portrait of Former Minister Dr. V. Matai by Albert Janesch (1889–1973), Portrait of Poet Richard Billinger by Sergius Pauser (1896–1970), and Prince Alexander Dietrichstein-Nikolsburg by John Quincy Adams (1874–1933).26

Critics also considered the realistic figurative representation a positive value in the portrait sculptures on display, such as those by Alfred Hofmann (1879–1958) and Otto Hofner (1879–1946) (Czyżewski 1930, p. 239). However, the most acclaimed sculptures were Franz Barwig’s (1868–1931) animalistic works, which were decoratively stylized and adept at capturing the silhouettes of animals in motion and at rest (Treter 1930, pp. 238–39; Siedlecki 1930, p. 239; Winkler 1930a, p. 8).27 Even if the critics lacked extensive knowledge of contemporary Austrian art, their intuition did not fail them in this respect. By the end of his life (he committed suicide in 1931), Barwig, a professor at the Vienna Kunstgewerbeschule, had achieved international renown as an outstanding exponent of Art Déco and new classicism (Hubert et al. 1984, pp. 68–69).

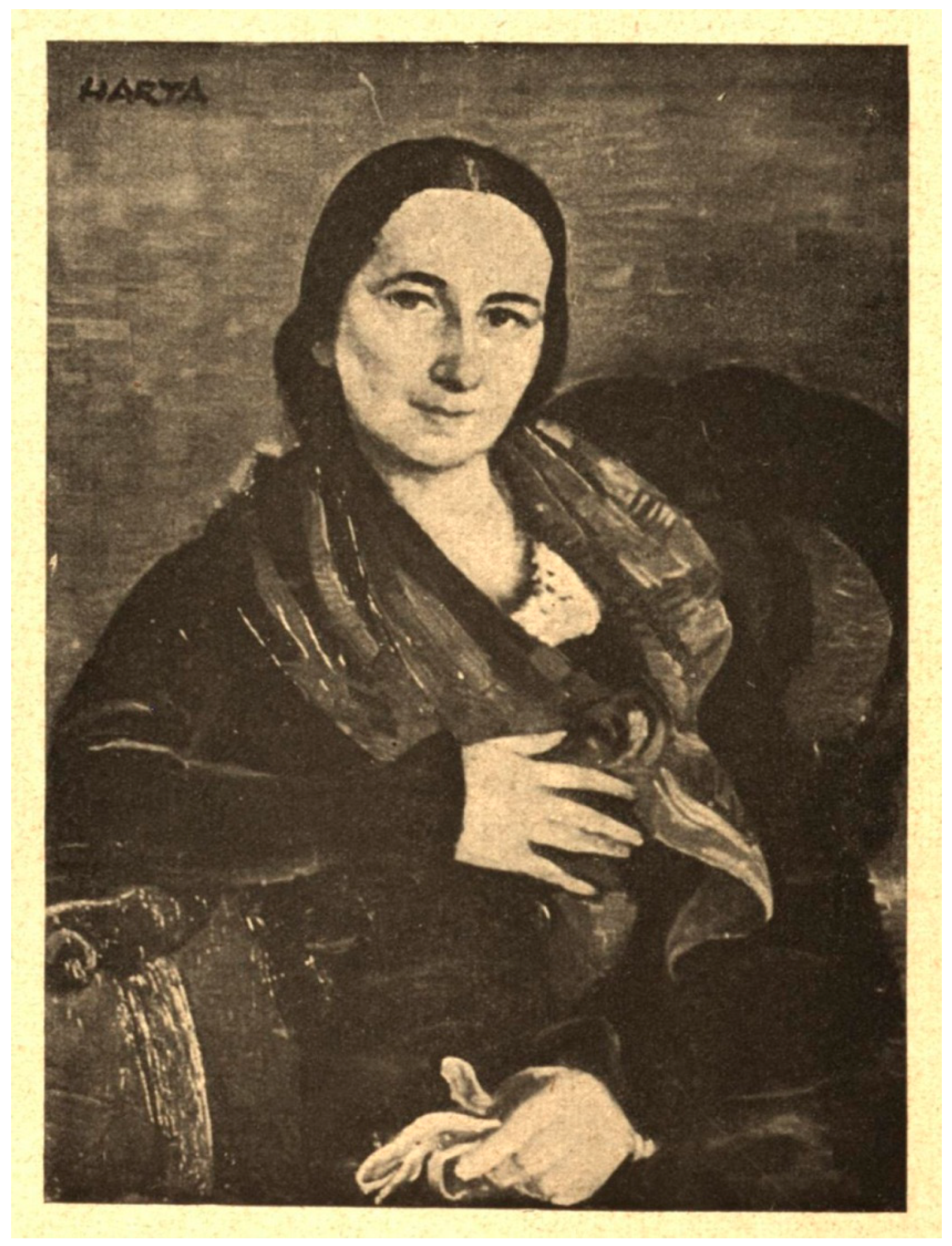

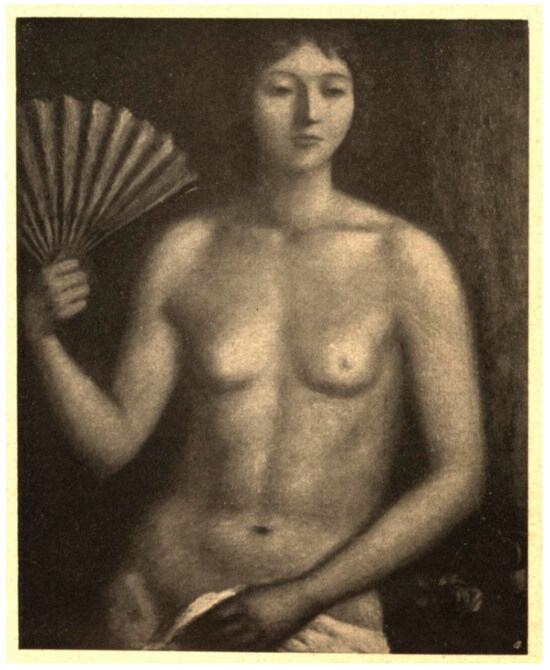

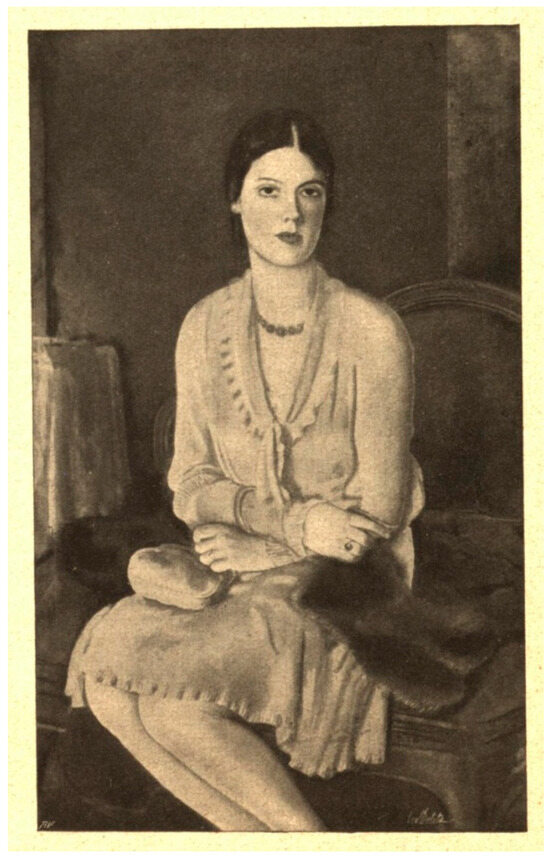

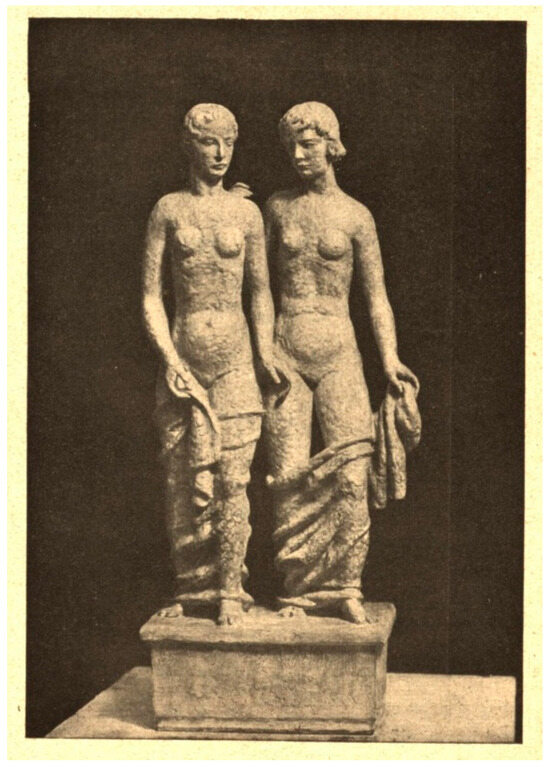

The principles of new classicism—a movement that quickly spread beyond Italy and France to influence many European art scenes, including Poland—were well-known and easily recognizable to critics in Warsaw. However, the dispersion of works that could be classified under the ‘umbrella’ of new classicism at Zachęta led to a lack of consolidation of the trend in the critical commentaries. Wiktor Podoski identified classical features in Adolf Curry’s painting Girl with a Fan (1879–1939), but did not perceive them in Leo Delitz’s Portrait of a Lady (1882–1966), despite the painting’s style aligning with the classicizing wing of Neue Sachlichkeit and the conventions of depiction used by Novecento Italiano artists (Figure 3. Adolf Curry, Girl with a Fan; Figure 4. Leo Delitz, Portrait of a Lady) (Podoski 1930a, 8). Similarly, Jakob Löw’s bronze sculpture Two Women (1887–1968), which evoked clear associations with ancient Greek sculpture, was also not associated with new classicism (Figure 5. Jakob Löw, Two Women).

Figure 3.

Adolf Curry, Girl with a Fan, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

Figure 4.

Leo Delitz, Portrait of a Lady, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

Figure 5.

Jakob Löw, Two Women, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

Critics who evaluated the exhibition positively emphasized the high level of Austrian artistic culture and aesthetic taste, their technical mastery across various media, and their moderation in adopting the norms of realism and assimilating modernist idioms (Husarski 1930, pp. 239–40; Podoski 1930b, p. 7). Reviewers agreed that by focusing on technical skills, the Austrians avoided engaging in theoretical speculations and meta-commentaries. This avoidance, however, stifled their exploratory passion and the drive for innovation and progressiveness (Winkler 1930b, p. 240; Kleczyński 1930b, p. 18). The main reason for such conclusions was that the exhibition’s organizers prevented the Polish audience from encountering the diverse factions of the Austrian avant-garde, offering only a single room for works representing a very moderate variant of this broad and multifaceted movement (Treter 1930, p. 238).

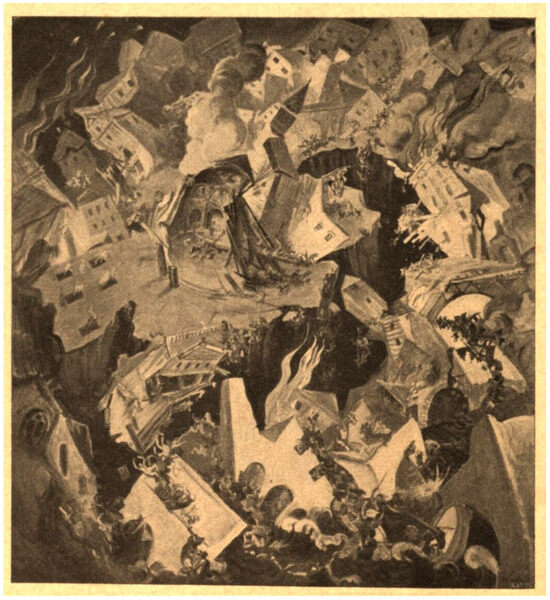

Franciszek Siedlecki perceived a specific idiom of modernist syntax in Oskar Laske’s (1874–1951) apocalyptic vision, where the primitivist form and elaborate narrative, divided into several simultaneous episodes, evoked the art of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whom Laske admired (Siedlecki 1930, p. 238). However, the whirling pictorial space of The End of the World was closer to the expressionist deformation in James Ensor’s imagery, another important point of reference for the artist (Figure 6. Oskar Laske, The End of the World).28 Nonetheless, the idiosyncratic style Laske created was difficult to categorize definitively. Due to stylistic references to Netherlandish art, it was situated closer to the poetics of magical realism than to early twentieth-century expressionism. In turn, those Warsaw critics who highly appreciated his works (Bird Market, Shark on the Beach) recognized the artist’s distinctiveness in the context of the very moderate modernism presented at Zachęta (Winkler 1930b, p. 240).

Figure 6.

Oskar Laske, The End of the World, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

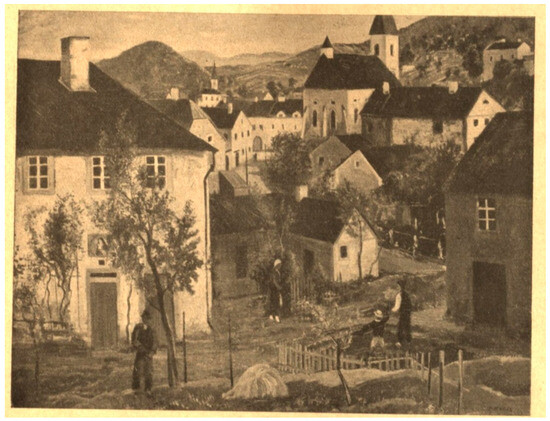

In addition to Laske, this small group of modernists included Ernst Huber (1895–1960), a self-taught painter like Laske, who captivated critics with his primitivist approach to depicting native landscapes (Figure 7. Ernst Huber, Village in Upper Austria) (Siedlecki 1930, p. 239). Wilhelm Thöny (1888–1949) drew Tytus Czyżewski’s attention with his painting City by Night, a work aligned with expressionist aesthetics, notable for its dark color palette and impasto texture (Czyżewski 1930, p. 239).

Figure 7.

Ernst Huber, Village in Upper Austria, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

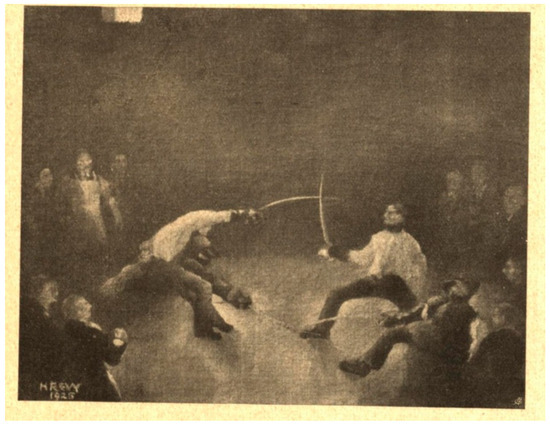

Czyżewski also identified several other artists as part of a group he, somewhat inaccurately, labeled ‘leftist modernists’: Heinrich Révy (1883–1949), a Croatian by origin; Louise Merkel-Romée (1888–1977), of Jewish–Polish descent; Frieda Salvendy (1887–1968), with a Slovak background; Henryk Rauchinger, a Pole settled in Vienna; and Alois Leopold Seibold (1879–1951), a Viennese artist. Révy’s painting Fencers was executed in a primitivist style and exemplified a ‘middle path’ between the extremes of radical modernism and orthodox traditionalism (Figure 8: Heinrich Révy, Fencers).29

Figure 8.

Heinrich Révy, Fencers, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

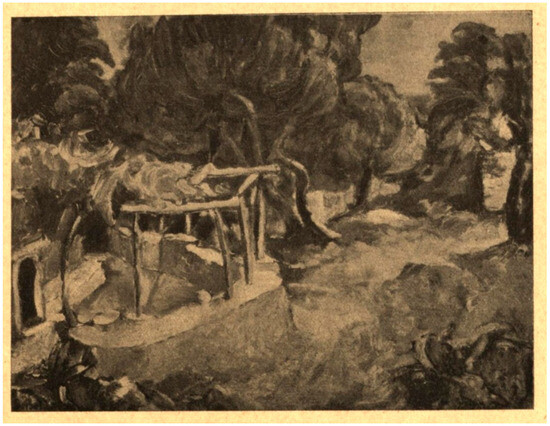

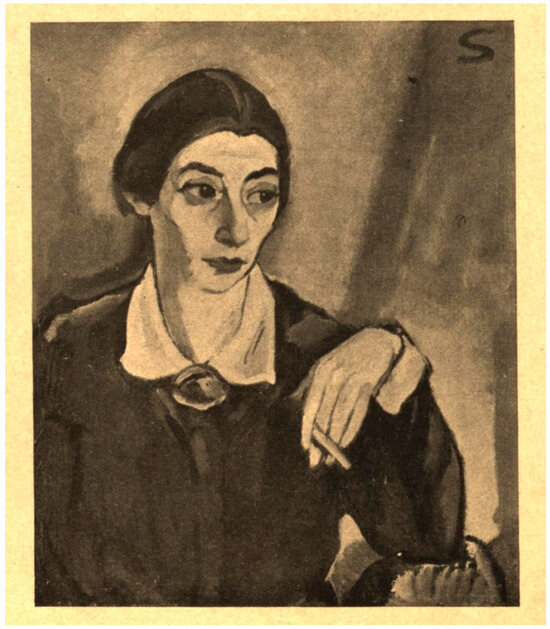

In the party distinguished by Czyżewski, only Seibold retained the gloomy chromatic range and free brushstrokes of the expressionists (Figure 9. Alois Leopold Seibold, In the Olive Grove). Nevertheless, his artistic output at Zachęta was primarily exemplified by prints—etchings and lithographs. Both Merkel-Romée and Salvendy were among the very few female artists associated with the Hagenbund, as their works aligned perfectly with the league’s program, which rejected the decorativeness of the Secession and the dramatic tension of expressionist depiction (Figure 10. Frieda Salvendy, Portrait of Mrs G.B.L.).

Figure 9.

Alois Leopold Seibold, In the Olive Grove, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

Figure 10.

Frieda Salvendy, Portrait of Mrs G.B.L., reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

In both Tietze’s interpretation and the reception by Warsaw critics, moderate modernism was associated with the exclusion of abstraction as well as cubist, futurist, and expressionist distortions of form. Instead, it favored figuration that, while emphasizing the specificity of artistic language, adopted a cautious and measured approach to innovation and experimentation (Oberhuber 1982; Natter 1993). A defining feature of this moderate modernist imagery was its sketchy pictorial style, characterized by free brushstrokes, simplified forms with flat areas of color in varying textures—ranging from impasto to more subdued applications—discontinuous contours, the silhouette treatment of human figures, and a geometrized approach to architectural elements, often confined within a narrow picture frame. In fact, the boundary between certain strains of moderate modernism and neorealism had become increasingly blurred.

Some proponents of the Hagenbund—an association that, while initially overshadowed by the Vienna Secession, gained more prominence in the Viennese art scene after 1918—distanced themselves from the 19th-century origins of the realist trend. They sought to create new formulas of depiction, often perceived through the lens of ‘museum art’, and frequently referencing Pieter Bruegel the Elder. These approaches were, in some cases, similar to the German Neue Sachlichke (Reichhart 1977; Koller et al. 1984; Ammann 1993, pp. 16–24; Schröder 1995; Bertsch 2000). In the second half of the 1920s, Rudolf Wacker, Rudolf Lehnert, Franz Sedlacek, Karl Sterrer, Franz Lerch, Ernst Nepo, Otto Rudolf Schatz, Georg Jung, Herbert von Reyl-Hanisch, Albin Egger-Lienz, and Alfons Walde developed their own idioms of New Objectivity.30 Among these artists, only Franz Sedlacek (1891–1945) was included in the Warsaw exhibition. The Zachęta gallery showcased two of his works: Winter Landscape and Wanderer by the Sea, which embodied a unique idiom of magic realism. This style was rooted in a primitivist aesthetic with early Renaissance roots and employed a solid technique inspired by the paintings of the old Netherlandish masters (Spiegler 2014).

The idioms of neorealism were also represented at the exhibition by Carry Hauser (1895–1985) and Sergius Pauser, artists who dramatically altered their pre-war artistic language. The expressionist nerve in Hauser’s work faded out in the late 1920s (Cabuk and Husslein-Arco 2012). He had been an adherent of the progressive Freie Bewegung31 from 1919 to 1922 and a member of the Hagenbund from 1925 to 1938. In the 1930s, Hauser completely abandoned modernist aesthetics in favor of decorative and lyrical realism with Renaissance genealogy, as seen in works like Madonna I, Madonna II, and The Holy Family (Winkler 1930b, p. 240). Another paradigm of new realism dominated Pauser’s mature work. In his youth, the artist, a graduate of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, highly appreciated the art of Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckmann, and Otto Dix, and maintained connections with Paul Klee (Pauser 1996). However, upon returning to Austria in 1924, Pauser entirely relinquished expressionist imagery and developed a pictorial formula akin to the classicizing wing of the German New Objectivity, yet reflecting the artist’s intensified sensitivity to color, exemplified by works such as Girl, Portrait of Poet Billinger, and Fishing Port.

7. National Landscape and Embracing the Other

As previously mentioned, Viennese artists primarily depicted provincial landscapes rather than metropolitan environments. Such an approach to the thematic range complied with the policy of regionalism, which gained prominence in the First Austrian Republic (Secklehner 2021, p. 205). The artworks predominantly featured picturesque landscapes from Upper and Lower Austria, Carinthia, and Styria. Examples included Richard Harlfinger’s Freistadt, Josef Dobrowsky’s Hirschbach, Ernst Huber’s Village in Upper Austria, Franz Windhager’s Landscape from Upper Austria, Anton Nowak’s In Staatz, Sergius Pauser’s Castle in Hausenbach, Franz Trenk’s Tauernsee, and Max Bradaczek’s Castle in Carinthia. These representations showcased rural homesteads, lake valleys, and Danube gorges, castles perched on rocks, towns nestled in mountain slopes, and snow-covered forests. Such views were meant to be easily identifiable with the geographical, natural, and architectural uniqueness of the Austrian Republic. In contrast, the Viennese metropolis was a relatively rare subject (e.g., Ferdinand Kruis’ Votivkirche in Vienna), with the notable exception of the vibrant, bustling amusement park Prater (e.g., Christian L. Martin’s In the Viennese Prater and Sergius Pauser’s Viennese Prater at Night).

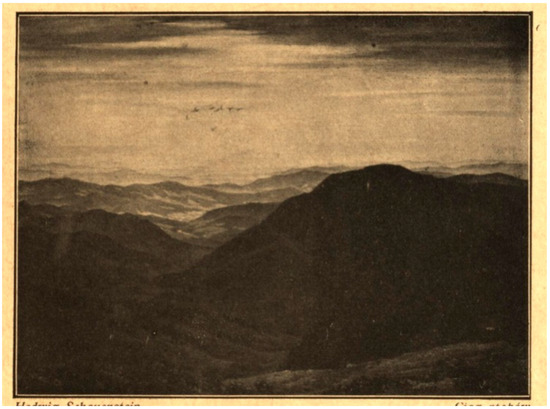

Among the federal states of Austria, Tyrol was the least frequently represented in the galleries of Zachęta. In this context, the painting by Christa Deuticke-Szabo (1894–1958), featuring the alpine peak of Kitzbüheler Horn, was an exception. Another example of mountainous motifs was Hedwig Schauenstein’s (1896–1988) luminous, panoramic depiction of monumental mountain ranges from a bird’s-eye view. This work appealed to Franciszek Siedlecki, an artist and critic with a symbolist background, who was sensitive to landscapes evoking metaphysical connotations (Figure 11. Hedwig Schauenstein, Flight of Birds).

Figure 11.

Hedwig Schauenstein, Flight of Birds, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

The absence of alpine motifs in the exhibition’s scenario was indicative of the cultural diplomacy employed by Johannes Schober’s cabinet, aimed at the Polish audience.32 This aspect of Schober’s cultural policy becomes particularly significant when compared to the export exhibition Tiroler Künstler, which was displayed in several German cities, including Düsseldorf, Hamburg, and Munich, from 1925 to 1926, where it achieved considerable success. At that time, the art of Tyrolean artists was seen as an important element of national identity and a tool of soft power on the international stage. The exhibition was crafted to manifest regional specificity, perceived as an intrinsic cultural feature of New Austria (Secklehner 2021, pp. 221–22). It was relocated to Budapest in 1927 and later featured in Zurich in 1928. Just a few years later, the nationalist Ständestaat regime appropriated the promotion of Tyrol for its own purposes, endowing the region with emblematic significance in the new Austrian identity, blending folk tradition with modern alpine culture, as seen in touristic ventures and mountaineering clubs (Secklehner 2021, pp. 208–15).

Equally notable about the exhibition held in Warsaw was that its scenario did not confine landscape and genre subjects to domestic themes, despite the focus on indigenous culture and the cultivation of the vernacular being prevalent trends in interwar Europe. The inclusion of landscapes depicting Czech (Valerie Czepelka), Slovak (Tibor Gergely, Rudolf Konopa, Wilhelm Legler, Frieda Salvendy), Slovenian (Georg Mayer-Marton), and Croatian (Alois Leopold Seibold) regions could partly reflect the emotional attachment to their motherlands among those artists, who were not native German Austrians. Conversely, this choice might have also stemmed from nostalgia for the once-extensive multinational and multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire. Moreover, it might be seen as evidence of the Hagenbund’s willingness to cooperate with artists of non-German derivation from the successor states (Clegg 2006, p. 230; Husslein-Arco et al. 2014). A member of the Permanent Delegation of Artists’ Associations, the Hagenbund might have contributed to the selection of exhibits shown in Warsaw. Additionally, the Warsaw exhibition at Zachęta attracted attention to landscapes painted during study trips to picturesque locations in France (László Gábor, Felix Albrecht Harta, Erich Miller-Hauenfels), Italy (Franz Elsner, Jehudo Epstein, Tibor Gergely, Georg Mayer-Marton, Otto Trubel, Henryk Rauchinger), Germany (Ferdinand Kruis, Hans Frank), the Adriatic coast of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (Georg Mayer-Marton), and even Egypt (Alfred Gerstenbrand). Such a diversification of representations transcending national borders was intended to exemplify Austria’s openness to other cultures and to affirm the Europeanness of Austrian art.33

8. Foreign Models

As with other official exhibitions organized by European nation states, Warsaw critics raised questions about the (un)significance of foreign influences in the works of the guest artists.34 Tytus Czyżewski, an artist with modernist affiliations, explored this issue by examining artworks he labeled as impressionist, demonstrating that the Austrian variant of the trend was distinct from the French model (Czyżewski 1930, p. 239). Nonetheless, he mistakenly attributed the influence of Courbet to Josef Dobrowsky’s (1899–1964) painting Girls by a Window (Figure 12. Josef Dobrowsky, Girls by the Window). In the 1920s, Dobrowsky,35 one of the most outstanding interwar Austrian painters of Czech origin, painted chromatically saturated landscapes and genre scenes primarily related to the pictorial conventions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Dobrowsky and Zemen 2007). Indeed, it was this primitivist style that was evident in Girls by a Window.

Figure 12.

Josef Dobrowsky, Girls by the Window, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

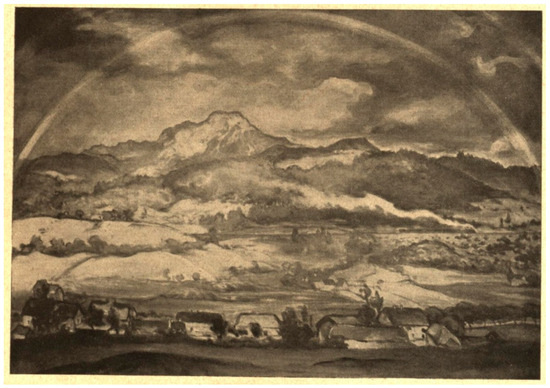

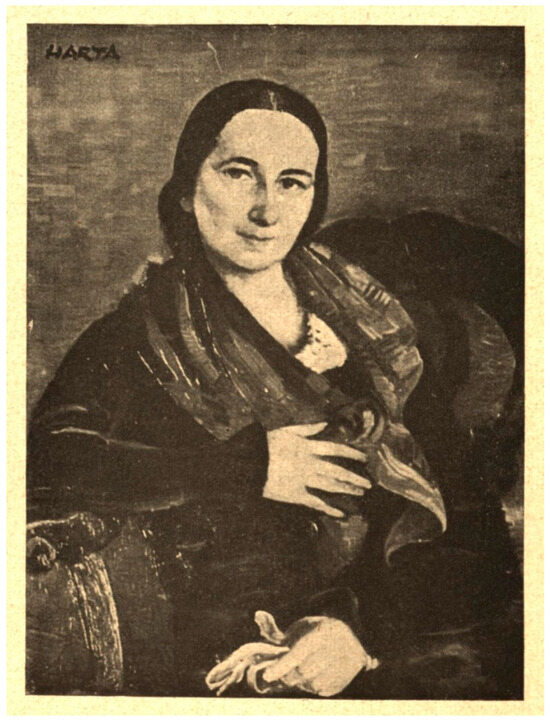

Czyżewski was mostly interested in colorists whose palettes appealed to his taste, favoring post-impressionist idioms of depiction. Thus, he approvingly listed such names as Adolf Christl (1891–1974), Ferdinand Kitt (1887–1961), Georg Mayer-Marton, Felix Albrecht Harta, and Richard Harlfinger (1873–1948).36 However, the dark, saturated chromatic gamut of Harlfinger’s paintings and their symbolic overtones implied a close relationship with expressionism rather than with the aestheticizing modernism of Parisian origin (Figure 13. Richard Harlfinger, Rainbow). On the other hand, the French influences in Félix Albrecht Harta’s works were undeniable. Born in Budapest and educated as a painter in Munich and Paris, the young Harta belonged to Klimt’s circle, where he embraced the poetics of expressionism. However, several stays in France led him to change his style to post-impressionism. The warm, bright color palette complemented the Cezannesque compositional structure in Harta’s Cagnes sur mer, which was highly acclaimed by Czyżewski. In turn, his Portrait of Madam Sz., awarded the Austrian National Prize in 1929, clearly revealed the impact of Manet (Figure 14. Felix Albrecht Harta, Portrait of Mrs. Sz.).

Figure 13.

Richard Harlfinger, Rainbow, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

Figure 14.

Felix Albrecht Harta, Portrait of Mrs. Sz., reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

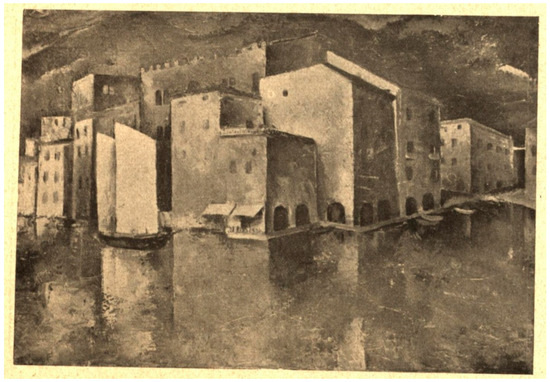

The Cezannesque discipline is also evident in Georg Mayer-Marton’s landscapes (Figure 15. Georg Mayer-Marton, Port in Malcesine), which were praised by several Warsaw reviewers (Podoski 1930a, p. 7; Winkler 1930b, p. 8). Born in Győr, Hungary, Mayer-Marton graduated from the academies of fine arts in Vienna and Munich. His excellent reputation in interwar Austria led to his appointment as vice-president of Künstlerbund Hagen (Schmidt 1986). To complete the list of Austrian painters who drew upon the French art scene, impressionism in particular, Konrad Winkler also mentioned Franz Elsner (Lago Maggiore) and Lászlo Gábor (Cross de Cannes).

Figure 15.

Georg Mayer-Marton, Port in Malcesine, reproduced from Przewodnik po wystawie Towarzystwa Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych nr 54. 1930. Warszawa: TZSP.

Winkler attempted to explain the Austrians’ susceptibility to French artistic impact. As a former member of the avant-garde group Formiści [Formists] (1917–1922), he perceived France as the cradle of modern art.

“[..] as far as French art is concerned, this influence seemed all the stronger as it was exerted on similar levels of the nation’s spiritual and mental life as in France. By no means is the spiritual affinity of these two different nations accidental. The old, sophisticated culture of southern nations, similar climate, close proximity to Italy, and ancestral bonds with France and Spain provided Austrian artists’ instincts and plastic preferences with almost Romanesque features,” argued the critic.(Winkler 1930b, p. 8)

Thus, Winkler combined the premises of Hippolyte Taine’s philosophical determinism with elements of Europe’s dynastic history and the idea of universal Kunstwollen, which materializes in national stylistic idioms, as advocated by several Central European followers of the Wiener Schule (Bakoš 2004, pp. 79–101; Bakoš 2013, pp. 11–40, 125–47, 168–217; Bartlova 2013; Filipová 2013). Perceived in this way, the amalgam of borrowings was an integral part of Latin culture, considered the common heritage of Italians, Frenchmen, Spaniards, and Austrians, in line with the logic of Winkler’s argumentation. At this point, it is worth quoting a broader passage from the critic’s essay, as it exemplifies the interwar historiographic and critical discourses that often manipulated factual data to justify and support contemporary ideologies.

“It was of this tradition of Charles V and the likes and other patrons of the Italian Renaissance on the lands of Austrian feudal lords–further of the tradition of the Classicists–eclectics and much delayed epigones of the Italian Baroque, such as Fischer von Erlach [..], that this art was born, perhaps too moderate and not very independent–nevertheless, deeply cultural, lively, tasty, and light in form and structure due to its warm color tones and nodding enthusiastically with all the joy of life and the sun,” concluded Winkler.(Winkler 1930b, p. 8)

In his opinion, as well as in the interpretation of other Polish commentators who followed Tietze, the specificity of Austrian art lay in its evocation of typically Austrian spiritual features, which originated from Latin culture.

9. Austrianness

Wiktor Podoski was the only critic to analyze the relationship between official state patronage and the artistic milieus in interwar Austria (Podoski 1930a, p. 9). He correctly observed that these relations were affected by the shift from an imperial monarchy to a territorially limited and economically weakened republic. The role and mission of the patron, once held by the imperial court, its aristocratic branches, and the Church, were assumed by the secular state. This new cultural policy had a broader scope and greater social significance than the aesthetic preferences of the nobility (Podoski 1930a, p. 8).37

For Podoski, one of the vehicles for mass access to art was the rapidly developing industry of applied arts. Due to the importance of this leading branch of Austrian industry, he was dissatisfied with the way designers’ products were displayed at Zachęta. “These bits of accessories gathered in one, very nicely arranged, room do not tell us anything. They are advertising exhibits of various Viennese companies. For no obvious reason, they are placed extremely low down, almost at floor level, which makes them very difficult to see. In a nutshell—a typical shop window,” he complained (Podoski 1930a, 8). Podoski was associated with the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, where, only since the mid-1920s, the faculty had begun to implement a curriculum aimed at elevating applied arts to the same status as fine arts.38 Thus, the display of applied arts in such a commercial format might have surprised him.

Additionally, he was outraged by the anonymity of the designers. “The catalogue, where all [names—author’s note] should be found, does not even contain the slightest mention of them. Only company names are given,” he noted (Podoski 1930a, p. 8). His interest in contemporary Austrian design was stimulated by the memory of the exemplary artistic craftsmanship of the Viennese Kunstgewerbeschule and Wiener Werkstätte, neither of which were featured in the Zachęta catalogue, despite Tietze praising their contributions—along with the input of the Werkbund—to the formation of modern Austrian design (Tietze 1930b, p. 6). Porcelain ware, glass products, faience, and enamels from companies such as Maria Schwamberger-Riemer, Wilma Schalk, Friedrich Goldscheider, Rie Gomperz, Augarten Porzellan Fabrik, and Bimini Fabrik attracted the attention of visitors, while also arousing controversy. The polemic among reviewers did not concern the artistic quality of Austrian design, but rather the anonymity of the designers, as Podoski remarked. For some critics, this anonymity was proof of the artists’ modesty and service to society (Kleczyński 1930, p. 18). However, for Podoski, it was a symptom of the appropriation of creative thought by the owners of commercial companies (Podoski 1930a, p. 8).

While the design typical of the Wiener Werkstätte and their followers was considered a distinctive feature of Austrian culture, the question of the Austrianness of the visual arts was difficult to resolve unambiguously. For several Polish critics, the dominant aspect of the artistic material presented at Zachęta was realism—moderate realism, in some variants decorative and color-oriented, yet for others, it was something more akin to Neue Sachlichkeit. Konrad Winkler considered “the predilection for calm, realistic traditional art” to be a typical feature of Austrian artworks (Winkler 1930a, p. 8). Jan Kleczyński added: “a lot of realism, but without impressionist spotting, common sense, little fantasy, moderate decorativeness—this is a concise description” (Kleczyński 1930, p. 17). Following Tietze’s attempt to place Austrian art in a social context, Kleczyński underscored that the aforementioned aesthetic characteristics were linked with bourgeois modesty and contrasted them with the outdated culture of the courtly splendor of the Habsburgs.

However, Austrian neorealism was not regarded in Warsaw as an artistic convention exclusively suited to expressing Austrianness. In both Tietze’s interpretation and the opinions of Polish reviewers, realism conveyed typically Austrian mental traits, alongside muted neoclassicism and restrained modernism. The recognition of moderation as a defining characteristic of contemporary Austrian art excluded extreme tendencies and attitudes, whether radically modernist (expressionism, Kineticism, and abstraction) or deeply conservative. Nevertheless, prominent art experts such as Mieczysław Treter, Wacław Husarski, Franciszek Siedlecki, and Konrad Winkler concluded that the display at Zachęta provided an adequate and comprehensive overview of the contemporary Austrian art scene (Podoski 1930a, p. 9; Treter 1930, p. 238; Husarski 1930, p. 239; Winkler 1930b, p. 240). Regarding the omitted areas, Warsaw commentators seemed to treat them as marginal or outdated.39

Moreover, they did not address the psychological simplifications and sweeping generalizations in Tietze’s introductory essay. Advocates of the concept of national art, like Treter, adopted a socio-psychological optic compatible with the psychocentric and essentialist interpretation of Austrian art proposed by Tietze. Consequently, in their quest to identify the essential features of Austrian identity expressed through artistic phenomena, the Warsaw critics, like Tietze, did not avoid significant lapses and flaws in their argumentation.

Nevertheless, from today’s historical perspective, it is clear that the curatorial strategy of the Zachęta exhibition, while biased, avoided the pitfalls of an ethno-nationalistic optic. The central concept shaping the Austrian presentation was the ‘middle way,’ which sought to neutralize extremes and uphold Vienna’s role as a cultural hub at the crossroads of European artistic trends—a role successfully fulfilled during the Habsburg era. Viewed through this lens, post-WWI Austria was seen as “the cultural mediator between the North and the South, the East and the West,” as Hans Tietze claimed (Tietze 1923, p. 12). Despite being supportive of contemporary avant-garde trends, Tietze skillfully conformed to the prevailing cultural policy and maintained the official rhetoric of the Austrian state. While he reduced the concept of the Austrian spirit to mere psychological stereotypes, he underscored that “in its merits and drawbacks, Austrian art is a truthful reflection of the character of the nation” (Tietze 1930b, p. 7).

Evidently, the Austrian presentation at Zachęta, along with Tietze’s elucidation of the material on display, perfectly fit into the framework of interwar cultural diplomacy, which relied on the instrumental treatment of official art exhibitions touring European cultural centers. In the case of many expositions contributing to this circulation, the heavy emphasis on identity paradigms resulted in the exclusion of several segments of the art scene, as the tendentiously constructed self-image of society was aligned with the current political agenda (Kossowska 2017).

10. Conclusions

The analysis of the Warsaw presentation reveals that the showcased visual material exemplified the goals of cultural diplomacy conducted during the First Austrian Republic. The exhibition aimed to highlight both the specific features of native art and its international connections, thereby emphasizing Austria’s significant position within European cultural trends. The exposition at Zachęta underscored the importance that Schober’s government placed on the rhetoric of openness to the cultures of other nations, particularly the successors of the Habsburg Empire. This approach contrasts fundamentally with the identity policy pursued in Austria during the 1930s.

From 1934 to 1938, the regionalist policies that developed in the 1920s were subordinated to the ideology of the nationalist and corporatist Vaterländische Front (Fatherland Front), the leading force in the Bundesstaat Österreich (Federal State of Austria, also known as the Ständestaat) (Secklehner 2021, pp. 52, 201–26). The authoritarian government, installed by Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, advocated a fascist-oriented, conservative policy that embraced Catholicism and folk traditions (Kriechbaumer 2002).

The study of the Austrian exhibition strategy from 1930 is particularly compelling because it highlights significant differences between the cultural diplomacy of Schober’s government and the cultural policy of the Ständestaat. The cultural policymakers of the Ständestaat did not prioritize Upper Austria, Lower Austria, Styria, or Carinthia as representative regions of Austria. Instead, they promoted the federal state of Tyrol, emphasizing its alpine landscapes, mountain resorts, flourishing tourism, local traditions, and the Catholicism practiced by the native population, including farmers and villagers. The regime elevated Tyrol to be emblematic of the core German–Austrian identity constructed in the new state (Barth-Scalmani et al. 1997, pp. 30–61; Secklehner 2021, pp. 52, 201–26).

In the latter half of the 1930s, the political landscape of the Second Polish Republic also shifted significantly as an authoritarian regime solidified its control. During this period, artistic exchanges between Poland and Austria came to a halt. The exhibition discussed in this case study represented the peak of Polish–Austrian cultural relations during the interwar years, briefly suggesting the possibility of broader cultural engagement. However, this was merely a manifestation of a short-lived political reset, ultimately thwarted by the Anschluss of Austria to Germany in 1938.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Research material has been archived at the Special Collections Department at the Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The narrow circle of the founding members of ‘Sztuka’ included artists of well-established reputation: Józef Chełmoński, Teodor Axentowicz, Julian Fałat, Jacek Malczewski, Józef Mehoffer, Antoni Piotrowski, Jan Stanisławski, Włodzimierz Temajer, Leon Wyczółkowski, and Stanisław Wyspiański. For detailed information on the association’s membership and activities, see (Krzysztofowicz-Kozakowska et al. 1995; Baranowa 2001). |

| 2 | The Zachęta Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts was founded in Warsaw in 1860 to support and promote Polish art during the time of the partitions by creating a collection of national art, providing scholarships to young artists, organizing exhibitions and competitions, and publishing works on native art. However, in the interwar period, Zachęta became a bastion of conservatism, sustaining outdated tastes and a preference for 19th-century conventions in visual arts. |

| 3 | The territory of the Republic of Austria was reduced from 676,000 km2 to 83,800 km2, while the population decreased from 51.5 million to 6.2 million inhabitants, the vast majority of whom were ethnic German Catholics (Kozeński 1967, p. 23). |

| 4 | The best exemplification of this tendency was Elemér Hantos’s treatises on the economic integration of Mitteleuropa, published between 1925 and 1935 (Kozeński 1967, p. 52). |

| 5 | The confirmation of the importance Austria attached to this concept was Chancellor Schober’s address delivered to the League of Nations in October 1930, proposing an economic plan within the framework of the Danube States agreement (Balcerzak 1974, p. 112). |

| 6 | From 1922 onwards, Heinrich von Srbik was Professor of History at the University of Vienna. After the Anschluss, he was appointed President of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna and gained membership in the German Reichstag. A fanatical German nationalist, Srbik advocated the concept of establishing a pan-German Reich, which would encompass an economically and politically united Mitteleuropa, ranging from the Baltic to the Adriatic Sea. His historical philosophy was consistent with Nazi ideology, although he did not propagate pure racism (Ross 1969, pp. 88–107; Sked 2018, pp. 37–57). |

| 7 | The Austrian Propaganda-Ausstellung traveled to Stockholm and Copenhagen in the autumn and winter of 1917–1918 (Clegg 2006, p. 284). |

| 8 | Born into the family of a Jewish lawyer, Tietze lived in Prague until 1893. This background influenced his fate after the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938. He and his wife, Erica Conrat, were forced to emigrate, first to London and later to the USA. |

| 9 | Tietze clarified his theoretical position, which was announced in Die Methode in (Tietze 1924, 1925b). |

| 10 | Tietze was an enthusiast of the avant-garde, particularly Oskar Kokoschka’s expressionist painting. In 1912, he published a review on Der Blaue Reiter Almanac, and in 1920, he joined the Gesellschaft zur Förderung Moderner Kunst in Wien. Within the framework of this association, in 1924, he organized an exhibition of Russian avant-garde works in the Neue Galerie, featuring the works of Wassily Kandinsky, Alexander Archipenko, and El Lissitzky. In 1930, he published his reflections on modern art in Die Kunst in unserer Zeit (Tietze 1930a). |

| 11 | On Tietze’s methodological approach, see (Lachnit 2005, pp. 98–110; Wagner 2010, pp. 440–43). |

| 12 | The complex issues of the relationship between the psychophysiological experience and the socially and culturally shaped mind of the viewer that occurs during the perception of an artwork has been discussed in (Marchi 2011, pp. ix–xii). |

| 13 | For an analysis of the collective societal psychology of Austrians, see (Johnston 1983, pp. 45–75). |

| 14 | Konrad Winkler (1882–1962) was a painter and art critic. From 1919 to 1921, he co-edited the journal Formiści (Formists) with Tytus Czyżewski and Leon Chwistek. The journal served as an organ of Formiści, one of the pioneering avant-garde groupings in interwar Poland. |

| 15 | Wacław Teofil Husarski (1883–1951) was an art historian, art critic, and painter. From 1902 to 1906, he studied at the Académie Julian and the Académie Colarossi in Paris, also attending lectures at the École Libre des Sciences Politiques et Sociales. In 1924, he joined the Polish group Rytm (Rhythm), which assembled artists with a classicizing profile. In the post-WWII period, he practiced monument conservation and held a professorship in art history at the University of Łódź. |

| 16 | Wiktor Podoski (1901–1970) was a printmaker and art critic. In the interwar period, he was a member of the group Ryt (Cut), which focused on graphic artists specializing in the woodcut technique. He also belonged to Blok Zawodowych Artystów Plastyków (The Block of Professional Visual Artists), known for its traditionalist program. |

| 17 | Tietze presented this stand during the 13th International Congress of the History of Art in Stockholm in September 1933 (Schmidt 1983, p. 47). |

| 18 | Quote after (Clegg 2006, p. 272). |

| 19 | Tietze claimed that great individuals played a decisive role in the evolution of art (Marchi 2011, pp. 27, 45). |

| 20 | The article is illustrated with black-and-white reproductions of some of the artworks discussed, borrowed from the exhibition catalogue. The fundamental issue regarding the absence of color illustrations in the text is that the catalogue entries related to specific works are so vague and insufficiently detailed that it becomes difficult to identify the exact objects and the collections in which they are housed. |

| 21 | Paradoxically, Tietze appreciated Kokoschka’s expressionist art already in 1909 when he commissioned the young twenty-three-year old artist to paint him a wedding portrait with his wife Erica Conrat (Hans Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat, Museum of Modern Art, New York). On the relationship between Tietze and Kokoschka, see (Soussloff 2000, pp. 61–82). Viennese expressionism also strongly influenced the concepts of Max Dvořák. In 1921, Dvořák published a foreword to the portfolio Oskar Kokoschka: Variationen über ein Thema (Dvořák 1921) Wien: Lany and Strache, 1921. For an insightful analysis of this text, see (Aurenhammer 1998, pp. 34–40). |

| 22 | The tradition-oriented tendencies that discarded not only non-figurative idioms but also the achievements of expressionism were influenced by the neo-humanist ideology centered on the French-led slogan rappel à l’ordre, which spread throughout Europe in the interwar decades. The dominance of traditionalist conventions of representation in the material presented in Warsaw should, therefore, be understood in the context of the rise of neoclassicist and neorealist idioms in the visual arts since the 1920s, as a counter-reaction against avant-gardism (Kossowska 2017, pp. 67–317). |

| 23 | I was unable to find materials regarding the organization of the Austrian exhibition in Warsaw in the Vienna archives, but analyzing the cultural policy of Johannes Schober’s cabinet in light of such documentation remains an open question. |

| 24 | The examination of the Warsaw exhibition also raises questions about the curator’s personal preferences and the relationships, animosities, and alliances within the artistic milieus. Since the documentation of organizational procedures has not been preserved in Polish archives, it is difficult to determine whether the artistic priorities of individual decision-makers significantly influenced the construction of the exhibition scenario. However, in my opinion, export exhibitions were so essential in creating a particular country’s soft power instruments that the organizers’ personal aesthetic predilections had to be aligned with the general policy of the country. Considering the overall concept of the exhibition at Zachęta, it was crucial to create an image of the national artistic scene that would strengthen the political message of the state authorities. |

| 25 | Enjoying its heyday in the 1920s, Wiener Kinetismus relied on the experiences of Cubism and Futurism, while also incorporating the geometric knowledge imparted through primary education in Austria–Hungary. Created by Austrians, Hungarians, and Czechs, the movement was an offshoot of Viennese Art Nouveau, distinguished by its geometric ornamentation. Reflecting this trend, the imagery of Kinetismus was characterized by the fragmentation of geometrized forms and rhythmic compositions that conveyed the dynamics of movement (Bast et al. 2011). |

| 26 | Jan Kleczyński (1875–1939) was a well-known writer, art critic, and columnist, as well as an outstanding chess player. |

| 27 | For an overview of Barwig’s art, see (Husslein-Arco and Fellinger 2014). |