Abstract

In the 7th century BCE, the Kushite king Tanwetamani commissioned his “Dream Stela”, which was to be erected in the Amun Temple of Jebel Barkal. The lunette of the stela features a dualistic artistic motif whose composition, meaning, and significance are understudied despite their potential to illuminate important aspects of royal Kushite ideology. On the lunette, there are two back-to-back offering scenes that appear at first glance to be nearly symmetrical, but that closer inspection reveals to differ in subtle but significant ways. Analysis of the iconographic and textual features of the motif reveals its rhetorical function in this royal context. The two strikingly similar but meaningfully different offering scenes represented the two halves of a Kushite “Double Kingdom” that considered Kush and Egypt together as a complementary geographic dual, with Tanwetamani presiding as king of both. This “Mirrored Motif” encapsulated the duality present in the Kushite ideology of kingship during the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, which allowed Tanwetamani to reconcile the present imperial expansion of Kush with the history of Egyptian activity in Nubia. The lunette of the Dream Stela is therefore political art that serves to advance the Kushite imperial agenda.

1. Introduction: Imperial Art

In the 7th century BCE, Tanwetamani ascended the throne of the Kingdom of Kush. At the time, this polity stretched from Upper Nubia to the Nile Delta. Tanwetamani was the last king in what, in Egyptological terms, is known as the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty. An Egypt-centric view may consider Tanwetamani the abrupt end of a short-lived dynasty, but from a Kushite perspective, he was far from the last in a line of rulers of the Kingdom of Kush. In his position as ruler, Tanwetamani inherited a kingdom composed of what was up to this point defined by the Egyptian state as two separate and often oppositional entities, namely Kush and Egypt. Millennia of Egyptian imperialism had portrayed Nubia and Nubians as an “Other”, distinct and subordinate to Egypt.1 The reversal of this longstanding power dynamic created the opportunity for the rulers of the Kingdom of Kush to develop their own imperial ideology.

The creation of a Kushite imperial ideology was fundamentally a creation of a new form of imperial power that could be used to rule over the Kushite “Double Kingdom” of Nubia and Egypt.2 This new imperial ideology involved the creation of a social identity fitting for Kushite royalty. As royals, their identity—the “idea of the self as understood against the social context”3—was “of necessity created, displayed and maintained in many media, and under a variety of circumstances”.4 In this case, the kings of Kush defined their connection to the gods, their legitimate claim to rule, and their relation to Nubia and Egypt. In this way, imperial ideology was inseparable from identity.

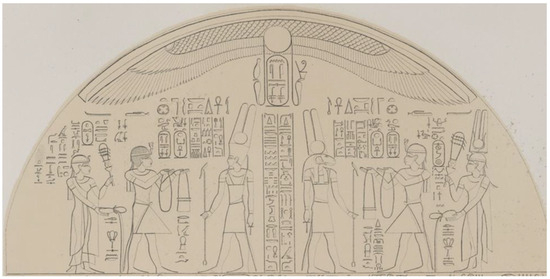

One method the rulers of Kush used to communicate and enshrine the identity necessary for imperial power was through the propagandistic display of a certain artistic motif. Tanwetamani was one such Kushite king, and the scene on the lunette of Tanwetamani’s Dream Stela encapsulates this practice. The stela was first published by Auguste Mariette and Gaston Maspero, and is now in Cairo.5 The scene on the lunette records the ideological foundation of the Kushite Double Kingdom and its kingship. The lunette is symmetrical or “mirrored”, composed of two offering scenes with the gods back-to-back in the center. In each scene, Tanwetamani, accompanied by a royal woman, offers to an aspect of Amun-Re. Two columns of text divide the two halves of the scene. The winged sun disk is above the whole arrangement.

However, there are key differences between corresponding sections of the two halves. Though Tanwetamani is the offering-bearer on both sides, he presents a different offering and a different royal woman accompanies him on the right versus the left. Further, Amun-Re is depicted with a ram head on the right and a human one on the left. These more noticeable iconographic differences join textual differences between the otherwise closely matching inscriptions on each side. These differences are essential to the function of the scene as a statement about the conceptual foundation of the kingdom and Tanwetamani’s role in his capacity as the current embodiment of kingship.

Analysis of the lunette shows that Tanwetamani used this particular motif to construct a royal ideology, based around dualism, that would propagate imperial power. From the royal Kushite perspective, they ruled a “Double Kingdom”, with Kush and Egypt being its constituent halves.6 The king embodied the aspects of Kushite and Egyptian kingship, with both geographic identities combining into one imperial whole. The motif displayed on the lunette reified this imperialistic worldview and thus manufactured power through the art’s interrelation of identity and duality.

2. Imperial Power in the Great Amun Temple of Jebel Barkal

“Imperialism” is a complicated and much-theorized subject, even when confined to the ancient world.7 Generally, scholarship focused on Egyptian imperialism in Nubia, rather than the reverse seen during the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.8 The use of the term “imperialism” here designates the collection of systems of power that allowed for the control of Kush and Egypt by a single Kushite ruler.9 This Kushite control was “imperial” because it was founded on forceful expansion into Egypt and hegemonic control over territory.

The Dream Stela was strategically placed at the center of a site long used to manufacture imperial power through monumental art. The stela was found in the first court of the Great Amun Temple of Jebel Barkal. The temple as a whole is now known as B 500 after Reisner’s system.10 This temple was originally built under Thutmose III in the context of Egyptian imperial expansion into Nubia, but was reconfigured by Piye, the Kushite king who subjugated Egypt militarily.11 Piye’s building program involved memorialization of his conquest of Egypt through the decoration program of the first courtyard.12 In addition, Piye brought Thutmose III’s Victory Stela, originally located in another temple, into B 500, setting it up next to his own Sandstone Stela, in which he declares his divine right to rule over Kush and Egypt.13 He later added his Great Triumphal Stela to the same location.14 With these additions and arrangements, Piye transformed a temple directly linked to Egyptian imperial control over Nubia to a site memorializing Kushite imperial expansion into Egypt.

Tanwetamani, the last king of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, continued the artistic tradition of power manufacture in the Great Amun Temple. Tanwetamani erected the Dream Stela in the first court of B 500 in the first half of the seventh century BCE, in proximity to the stelae of Thutmose III and Piye, the most recent of which was then approximately 90 years old. László Török suggests that the inclusion of Thutmose III’s stela in B 501 along with Kushite stelae “manifest[ed a Kushite] archaizing interpretation of legitimacy based on continuity”, by “not [italics in original] drawing any border between the Egyptian and Kushite past”.15 While such legitimating tactics were surely a factor, it is notable that this positioning created juxtaposition by placing the stela of an Egyptian king who imperially subjugated Kush next to that of a Kushite king who ruled imperially over Egypt. This juxtaposition subverted the xenophobic mainline of earlier Egyptian propaganda, asserting instead a parity between Kush and Egypt as two halves of a whole. This Kushite ideology was most particularly salient for the lunette of the Dream Stela.

3. The Dream Stela of Tanwetamani

By 1872, Auguste Mariette and Gaston Maspero published detailed line drawings of the texts of five stelae found in the Great Temple of Amun.16 One of these stelae was Tanwetamani’s Dream Stela, carved from grey granite (Figure 1).17 The authors gave the stela its name because the main text relates Tanwetamani’s experience of a prophetic dream that promised him kingship of Egypt. The authors do not specify the exact findspot for this collection of stelae, but in Reisner’s excavation and publication of the site he states that these stelae were found “in B 501 or in cache outside B 500”.18 This judgement was presumably a result of his theory that the Dream Stela once stood in B 501 or in front of Pylon I, a conclusion based on the empty sockets present for stelae in these areas.19 This corroborates Török’s reconstruction that the Dream Stela stood alongside the relocated Thutmose III Victory Stela in B 501.20

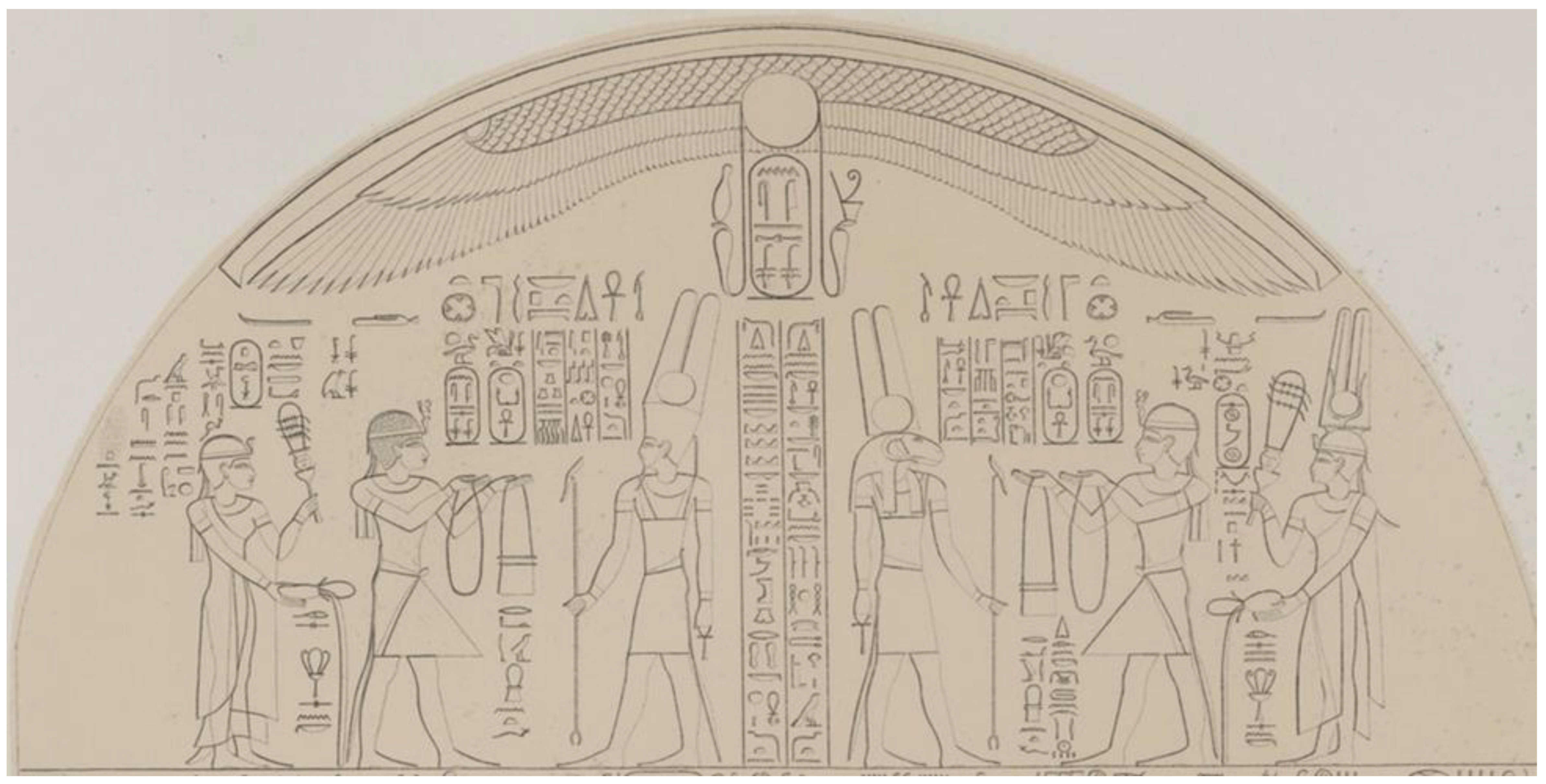

Figure 1.

The lunette of the Dream Stela of Tanwetamani. From B 501 of the Great Amun Temple, Jebel Barkal, c. 670 BCE. From (Mariette and Maspero 1889, Plate 7).

Assuming this reconstruction is correct, by placing the stela in B 501, Tanwetamani was participating in the dynastic tradition of constructing power through art at Jebel Barkal. In this paper, I argue that the Dream Stela clearly articulated the unique royal ideology and social identity of the rulers of the Kingdom of Kush: these rulers conceived of their Double Kingdom as composed of two complementary geographic halves, Kush and Egypt, rather than a Nubia subordinated to a northern imperial power. This ideology is conveyed on the Dream Stela through the scene on its lunette.

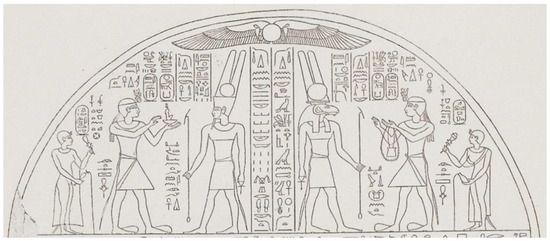

On one hand, the lunette on the Dream Stela is intentionally reminiscent of the lunette on the Victory Stela of Thutmose III (Figure 1 and Figure 2).21 The lunettes of both stelae depict what was called a “double” or “symmetrical” scene, and is here referred to as “mirrored”.22 The clear visual similarity between the two lunettes links Tanwetamani to Thutmose III, associating the earlier king’s power with the latter’s and, as Török noted, uniting the Kushite and Egyptian pasts. On the other hand, the imperial context of Thutmose III’s stela—and the inverse political situation at the time of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty—was not ignored. Though the layout of both lunettes is superficially similar, the lunette on the Dream Stela differentiates itself from that of the Victory Stela through artistic intricacy, complex symbolism, and its specific relevance to the Kingdom of Kush. Thus, the lunette of the Dream Stela uses its artistic form to produce and legitimate Kushite imperial power specific to its historical context.

Figure 2.

The lunette of the Victory Stela of Thutmose III. Relocated to B 501 of the Great Amun Temple, Jebel Barkal, originally erected c. 1430 BCE. From (Reisner and Reisner 1933).

4. Description of the Lunette

The lunette of the Dream Stela is the site of the art that effects Tanwetamani’s royal power. The lunette is well preserved and filled with a mirrored scene. The winged sun disk appears at the top above the mirrored halves. Each half consists of an offering scene featuring three figures such that the gods from the two scenes stand back-to-back with two columns of inscription in between them. On the right half, a ram-headed Amun-Re receives a pendant necklace from Tanwetamani, while Qalhata, his mother, stands behind the king shaking a sistrum and pouring a libation. Tanwetamani wears the double uraeus and Qalhata a single one. Amun-Re is identified as “Lord of the Throne [sic] of the Two Lands, resident in Jebel Barkal”.23 Tanwetamani is labelled with his nswt-bjtj and sA-ra names, while Qalhata is called “King’s Sister, Lady of Nubia [tA-stj]”, and her name is written in a cartouche. A caption in front of Tanwetamani’s legs clarifies that he is making the offering to “his father”. Finally, the righthand central text column records the speech of this criocephalic Amun-Re: “I have given you appearing as King [nswt-bjtj] on the Horus-throne of the living, like Re, forever”.24

The arrangement on the right side is largely mirrored over the central axis onto the left side, but with modifications. In the left scene, Tanwetamani offers Maat to an anthropocephalic Amun-Re, while Piankhyere, the king’s wife, stands behind him, wearing a uraeus, shaking a sistrum, and pouring a libation.25 On this side, Amun-Re is identified as “Lord of the Throne [sic] of the Two Lands, resident in Karnak”. Tanwetamani’s main caption is unchanged from the right side. Similar to Qalhata, Piankhyere is given a cartouche, but she is described as “King’s Sister and Wife, Lady of Egypt”.26 The caption in front of Tanwetamani’s legs specifies that he offers to “his father Amun [sic] so he may be given life”.27 Lastly, the lefthand central text column records the speech of this anthropocephalic Amun-Re, who has “given you all lands, every foreign land, and the Nine Bows, gathered under your sandals forever”.28

In aggregate, the lunette presents striking mirrored symmetry that is disrupted by differences between the iconography and texts on the left and right halves. The mirrored nature of the lunette alone suggests the primacy of dualism, but the differences between the left and right halves cement that theme by creating meaningful dualistic pairs. While such parallelism is also found in Egyptian art, the Dream Stela’s symbolism and themes are specific to the Kingdom of Kush. Therefore, not only the content, but also the layout of the lunette conveys royal ideology.

5. The Lunette as Representative of the Double Kingdom

The scene on the lunette is a rhetorical statement of the royal ideology of Tanwetamani in his role as ruler of the Kingdom of Kush. As such, it as art used to construct the basis of royal power. In order to arrive at this conclusion, it is necessary to understand the significance of certain iconographic and textual features on the lunette, pay particular attention to the small changes between the left and right sides, and consider the spatial distribution and arrangement of such features and small changes. An analytical process combining all three steps shows that each half of the lunette corresponds to one half of the Kingdom of Kush, the right for Kush and the left for Egypt (see Figure 3 for a diagram indicating the relevant features). Certain textual and iconographic elements indicate this split, and in so doing build upon and reinforce each other to present a picture of the “essentials” of “Tanwetamani-king-of-Kush” and “Tanwetamani-king-of-Egypt”. Further, the king’s presence on both halves asserts his position as king of both lands that together make one kingdom just as the halves make one scene.

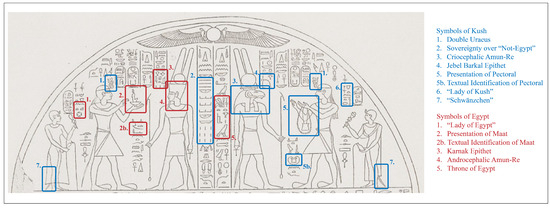

Figure 3.

The lunette of the Dream Stela with iconographic and textual features numbered and highlighted. Those in blue are references to Kush and those in red to Egypt. Adapted from (Mariette and Maspero 1889, Plate 7).

There are four pairs of these features: (1) the identity of Amun-Re, (2) the offering made by Tanwetamani, (3) what Amun-Re promises the king in return, and (4) the identity and titles of the royal woman accompanying the king.

On the right half, Amun-Re is ram-headed, or criocephalic. This aspect of the god is captioned “resident in Jebel Barkal”. This epithet indicates that this criocephalic Amun-Re is geographically specific to the most sacred site in Kush, the very place the stela was erected. Interestingly, the god is also referred to as “Lord of the Throne of the Two Lands”. The singular writing of “Throne” is unusual, as the epithet normally uses the plural “Thrones”. The singular here and in other contexts was viewed as a mistake.29 However, Timothy Kendall argues the singular was a deliberate choice by Kushite kings when referring to Amun-Re of Jebel Barkal in order to “redefine Napata’s [i.e., Jebel Barkal’s] mountain as the only active font of kingship”.30 Kendall’s conclusion is compelling, but complicated by the other half of the lunette, where the anthropocephalic Amun-Re is titled “Lord of the Throne [sic] of the Two Lands, resident in Karnak”. The depiction and caption show that the anthropocephalic Amun-Re is associated with Karnak in contrast to the criocephalic Amun-Re of Jebel Barkal. In other words, the right displays Amun-Re of Kush and the left Amun-Re of Egypt.31

An additional layer of geographical significance could potentially be inferred from the positioning of the two aspects of Amun-Re in relation to cardinal directions. It is possible that the stela was set up in B 501 with its back to the west. This would place the Nubian Amun-Re on the south side of the lunette facing north and the Egyptian Amun-Re on the north side of the lunette facing south. This arrangement would further associate the two aspects of Amun-Re with their respective homes. Such an orientation is suggested for similar stelae also found in and around B 501.32 Regardless, Tanwetamani follows the precedent set by Piye’s transformation of B 500 into a space for the display of Kushite royal power, erecting a stela that visually communicates Kushite power over the Double Kingdom.

The second pair of mirrored features is comprised of the offerings made by the king. On the right side, Tanwetamani offers a pendant and necklace. This is the standard iconographic depiction of the Kushite “pectoral”, as is confirmed by the caption below. This pectoral is distinctive of the Kingdom of Kush and is commonly offered to Amun-Re in art dating from the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty and later Napatan Period.33 Thus, while not as explicitly geographic as Amun-Re epithets, the pectoral is still strongly specific to Kushite kingship. On the left side, the king presents Amun-Re with a statuette of Maat. This statuette and the concept it embodied are not specific to the Kingdom of Kush, and were depicted in offering scenes in Egyptian contexts since Thutmose III.34 The presentation of Maat on the left side therefore contrasts with the presentation of the pectoral on the right side, once again suggesting geographic theming of the right with Kush and the left with Egypt, artistically representing imperial control over both lands.

The third pair of dual features is found in the speeches of the two aspects of Amun-Re. On the right side, the criocephalic Amun-Re promises Tanwetamani “appearing as King [nswt-bjtj] on the throne of Horus…”. The use of the phrase “nswt-bjtj”, which traditionally referred to the duality of Egyptian kingship, is striking, as is the clarification that the kingship offered is on the “throne of Horus”. These phrases imply that this Kushite Amun-Re is presenting kingship over Egypt to Tanwetamani. The inverse is found on the left side, where the Egyptian Amun-Re promises Tanwetamani “every land, every foreign land, and the Nine Bows, gathered under your sandals forever”. Dominion over “foreign lands” is one of the traditional aspects of Egyptian kingship, and the Nine Bows refers to Nubia specifically. In effect, Egyptian Amun-Re presents control of “not-Egypt”, with special attention to Nubia, to Tanwetamani. However, the use of the phrase “under your sandals” invokes the Egyptian tradition of imperial domination of such foreign lands rather than the type of kingship that would rule over Egypt. The message of this Amun-Re is therefore twofold: on one hand, violent control over foreign lands is a staple of Egyptian kingship, but on the other, Tanwetamani’s political context places him as an indigenous ruler of his own land, now rendered not foreign. Still, when combined with the gift of the criocephalic Amun-Re, the promise of rule over foreign lands could be read to simply mean rule over “not-Egypt”. In such a case, the right side of the lunette would show Kushite Amun-Re offering the king control over the Egyptian half of the Kingdom and Egyptian Amun-Re offering control over the Kushite half. The gods offering control of the opposite half of the Kingdom form a sort of interlocking construction, where the aspects of the gods exist in a symbiotic relationship, not hostile but complementary.35

The fourth and final pair of linked features is the identity of the woman accompanying Tanwetamani. On the right side, the king as accompanied by Qalhata, who is called the “King’s Sister, Lady of Nubia [tA-stj]”. Despite not being mentioned explicitly on the lunette, Qalhata is known to be the mother of Tanwetamani, though her relationship to other Kushite royals is disputed.36 The title “King’s Sister” refers to her being the sister of Taharqa, which is corroborated by Assyrian letters.37 With her placement on the right half of the lunette and her titles, Qalhata is associated with Nubia or Kush.

On the left side of the lunette, the reading of the name of the woman accompanying Tanwetamani is disputed, with possibilities including Piankharty,38 Piankhyere,39 and Piye-Arty.40 As with Qalhata, her exact position in the royal family is unclear. She was the wife and sister of Tanwetamani, as confirmed by the title on the lunette.41 However, it is unclear if she is the same person as Arty, a wife and sister of Shabataka.42 Whatever the case, she is the coeval of Tanwetamani, as opposed to Qalhata, who is his elder. The placement of Piankhyere on the left side and her title “Lady of Egypt” associate her with Egypt and contrast her with Qalhata.

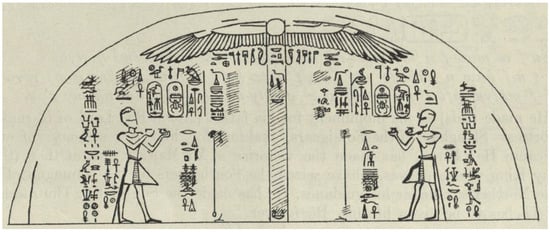

The contrast in identity and placement of the two women suggests several things. First, and most securely, their titles reinforce the overall split on the lunette between a Kushite right side and Egyptian left side. More speculatively, their arrangement suggests a connection between the position of the king’s mother and Kush on one hand, and between the king’s wife and Egypt on the other. Two other stelae originally from the same temple provide insight here. The Annals of Harsiyotef was found in the same cache as the Dream Stela in 1862, and stood in B 501 during the Meroitic Period.43 The stela’s lunette features mirrored symmetry such as that of the Dream Stela, with the king and a royal woman before an aspect of Amun-Re on each side (Figure 4). Additionally similar to the Dream Stela, Harsiyotef’s wife stands on the left half with Amun-Re of Karnak while his mother, who is also titled “Lady of Kush [kS]”, stands on the right side before Amun-Re of Jebel Barkal. Harsiyotef reigned about 250 years after Tanwetamani, so any connection between the two stelae would come from the intentions of Harsiyotef and not necessarily the political realities of Tanwetamani’s time. But the arrangement of royal women on the later stela seems to support the suggestion that the king’s mother was connected to Nubia, and his wife to Egypt.

Figure 4.

The lunette of the Annals of Harsiyotef. Likely from B 501 of the Great Amun Temple, Jebel Barkal, first half of 4th century BCE. From (Budge 1904).

The Stela of Nastasen, also likely from B 501, complicates the geographic connections suggested by the Dream Stela and Annals of Harsiyotef.44 The lunette of the Stela of Nastasen is arranged in the same scheme as the other two, with mirrored symmetry and a royal woman accompanying the king on each side (Figure 5). This time, however, Nastasen’s wife, “Lady of Egypt”, is on the right side with Amun-Re of Jebel Barkal, while his mother, “Lady of Kush [kS]”, is on the left with Amun-Re of Karnak. Thus, while the position of the king’s wife and mother switch sides, and therefore aspects of Amun-Re, their titles preserve their connection to Nubia and Egypt, respectively.

Figure 5.

The lunette of the Stela of Nastasen. From B 501 of the Great Amun Temple of Jebel Barkal, second half of the 4th century BCE. From (Lepsius [1849–1859] 1973).

Nastasen ruled over 300 years after Tanwetamani, and so over 50 years after Harsiyotef, but the two later stelae were clearly inspired by the Dream Stela, given their arrangement and placement.45 Both later kings continued to use the Great Temple of Amun as a site for creation and display of royal power, as evidenced by their stelae. The persistence of the association of the king’s mother with Nubia and wife with Egypt on the later stelae seems to indicate that their placement on the Dream Stela was not random. Furthermore, their titles, combined with the commonly accepted importance of royal women in the Kingdom of Kush, raises the question of if these women had some political role in their respective regions beyond symbolic connection. E. Y. Kormysheva argued for the involvement of the king’s mother as an embodiment of Isis in the king’s enthronement ceremony and for her power in the royal court in Napata.46 Similarly, Inge Hofmann suggested that the amulet found in the tomb of Neferukakashta, a wife of Piye, showing Isis suckling a woman, indicated that Neferukakashta ruled as “regent” in Nubia while the king attended to Egypt.47 Angelika Lohwasser dismisses Hofmann’s suggestion that Neferukakashta operated as regent in Nubia, though it is unclear if she rejects the notion of regency or only Neferukakashta’s hypothetical role in it.48 Kormysheva argues that the suckling woman must be a king’s mother, and that her presence in a suckling scene “places the king’s mother in a position equal to the ruling king”.49 Kormysheva’s assertion is compelling and would mesh with Hofmann’s notion of a female “regent” with some level of real political power over part of the empire. “Regency” on the level with the ruling king would perhaps be too far, but the amulet may suggest that the titles given to the royal women on the stelae are not entirely idealized.

Regardless of any real political power the “Lady of Nubia” and “Lady of Egypt” had over their associated realms, the lunette of the Dream Stela reinforces its geographic theming through the connection of two royal women to two halves of one kingdom. While the amulet from Neferukakashta’s tomb may suggest that the king’s mother’s title “Lady of Nubia” was associated with real political power, there is little besides the stelae discussed above to connect the king’s wife to a similar position over Egypt. Nevertheless, this reading of the royal women connects directly to the understanding of the lunette as a statement of the dualism central to imperial Kushite ideology that considered Nubia and Egypt component halves of a Double Kingdom.50

The four pairs of features explicitly differentiated between the right and left sides of the lunette are the core elements in the rhetorical message. The criocephalic Amun-Re and his Napatan epithet combine with the pectoral offering and Qalhata’s titles to designate the right the “Kushite side”, whose positionality is deepened by Amun-Re’s promise to place Tanwetamani-king-of-Kush on the throne of Egypt. In contrast, anthropocephalic Amun-Re of Karnak combine with the offering of Maat and Piankhyere’s titles to designate the left the “Egyptian side”, reinforced by Amun-Re’s promise of foreign lands and the Nine Bows to Tanwetamani, king of Egypt. The mirrored arrangement of the whole lunette and the connection of features on one side to their “missing half” on the other communicates the position that these two halves are one whole just as Kush and Egypt are. Tanwetamani presides as king over one imperial polity.51

However, there is one final aspect of the lunette of the Dream Stela that adds an important slant to the balanced dualism outlined above. Throughout the lunette, no matter the side, Tanwetamani and the royal women display signs of Kushite royalty. On both sides, Tanwetamani wears a double uraeus, with one cobra wearing the White Crown and the other the Red, and a headdress with two streamers. The two cobras of the double uraeus are understood to represent the two halves of the Kingdom of Kush, Nubia and Egypt, though this interpretation is contested.52 Regardless, the elements of the king’s headdress are understood to be characteristically Kushite, though the double uraeus is not unattested before the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.53 Similarly, both royal women wear a particular kind of tight dress and a cap with one uraeus, both associated with Kush.54 Even more significantly, they wear fox tails or “Schwänzchen”, which is distinctly Kushite, and operates as a feminine counterpart to the king’s bull’s tail.55 Both women also pour libations directly to Amun-Re, which is common for Kushite representations but rare in Egyptian art.56 These several elements iconographically mark the royals as Kushite, including in their representation on the Egyptian side of the lunette. The persistence of royal “Kushiteness”, even in their role as rulers of Egypt, suggests that, while the two halves of the lunette, and therefore the two halves of the kingdom, are complementarily bound into one whole, the royal position as rulers of Kush is given subtle primacy. This inflection gives the Kushite ideology of kingship a more typically imperial bent: though Egypt is theirs, Kush is put first.

6. Conclusions: Duality for Imperial Power

Analysis shows that the lunette encapsulated parts of the royal Kushite ideology created for the administration of their imperial kingdom. Duality was central to this ideology and was the central focus of the lunette of the Dream Stela. The Nubian and Egyptian halves of the Kingdom of Kush combined complementarily to form a unified whole, just as the two halves of the lunette combined to create one scene. The dual aspects of king of Nubia and king of Egypt were embodied in one man, Tanwetamani, who was legitimated by regional aspects of Amun-Re. However, even as king of Egypt, Tanwetamani was a Nubian king, as shown by the persistence of Kushite regalia on the half otherwise dedicated to Egypt. This worldview was revolutionary in the context of the past relationship between Nubia and Egypt. Instead of a conquered “foreign land”, Nubia was now the imperial center, and the half of the empire that was given a slight edge in rhetoric communicating an otherwise balanced dualistic relationship.

In its articulation of imperial ideology, the lunette of the Dream Stela also provides insight into royal roles beyond that of the king. The royal women on the lunette not only reaffirm the stela’s Kushite perspective through their dress and action, but their titles suggest their connection to one or the other half of the kingdom. The extent of their political power in their respective domains is, however, speculative.

Furthermore, the rhetoric of dualism central to the lunette affords an important opportunity for the understanding of royal Kushite identity from an emic perspective. Since the main function of the scene on the lunette involves the iconographic illustration of Kush and of Egypt, the features chosen to represent this duality are those self-selected by Kushite royalty to be particularly indicative of their positional identity as kings of both Kush and Egypt.

The motif on the lunette of the Dream Stela manufactured imperial power for the rulers of the Kingdom of Kush through the conveyance of the ideological foundations of that power. These ideological foundations were intrinsically connected to the social identity constructed by those same rulers. Ideology and identity together were on display in royal propaganda, including that located in the Great Amun Temple at Jebel Barkal. The scene on the lunette of the Dream Stela is a clear instance of an artistic motif being used to enshrine and promote these imperialistic views, with the additional dimension of doing so through a reimagining of old Egyptian paradigms. In this way, art was a tool for power.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The lived experience for Nubian and Egyptian people was more nuanced, but this work is concerned with state myths of royal ideology, both in the Egyptian and Kushite imperial context. |

| 2 | Studies discussing the formation of imperial power include (Spalinger 2023), and (Sabbahy 2021) |

| 3 | (Eltze 2017, p. 61). |

| 4 | See Note 3, p. 62. |

| 5 | Cairo JE 48863. (Mariette and Maspero 1889). More recently treated by Nicolas-Christophe Grimal, Quatre stèles napatéennes au Musée du Caire: JE 48863–48866 (Grimal 1981). Included in Karl Jansen-Winkeln, Inschriften Der Spätzeit III: Die 25. Dynastie. (Jansen-Winkeln 2009). |

| 6 | Jeremy Pope notes that the lived reality of the population of the Kingdom of Kush was not necessarily reflective of the royal conception of two elegantly unified halves, but more heterogeneous. Still, he writes that “[i]n the apparent absence of centralized institutions and national administrative hierarchy… the propagandistic functions of Kushite political theology may help to explain in part how the royal center related to local aristocracies and fostered national unity within an exceptionally diverse realm”. See (Pope 2014, p. 283). |

| 7 | For the application of the term “imperialism” to ancient contexts, see, e.g.,: (Boozer et al. 2020), (Zangani 2022), (Bellomo 2021), (Burton 2019, pp. 1–114) and (Morris 2018). |

| 8 | E.g., (Lemos and Budka 2021, pp. 401–18); (Bestock 2020); (Ferreira 2019); (Smith 1995). |

| 9 | The notion of systems used in combination to imperially control Egypt is shown in chapters V–VIII of Pope (2014). |

| 10 | (Reisner 1917, p. 214). |

| 11 | (Török 2002, pp. 54–55). |

| 12 | Same to Note 11, pp. 68–69. |

| 13 | For the location of the stela, see Note 11, Image of the Ordered World, pl. I. For more on the Sandstone Stela, see (Reisner 1931, pp. 89–100); (Eide et al. 1994, pp. 55–62). |

| 14 | For the display of Piye’s Victory Stela, see (Török 2002, p. 370). For other Twenty-Fifth Dynasty and New Kingdom stelae in 501, see (Török 2002, pp. 299, 299, notes 166–167). |

| 15 | See Note 14, pp. 298–99. |

| 16 | (Schneider 2015, p.45). |

| 17 | (Mariette and Maspero 1889, p. 2). |

| 18 | (Reisner 1931, p. 82). |

| 19 | See Note 18, p. 88. |

| 20 | (Török 2002, p. 298). |

| 21 | For more on the similarity of the Victory Stela of Thutmose III to later Kushite stelae, see Roberto (Gozzoli 2003, pp. 204–12) and (Hsu 2020, pp. 85–95). |

| 22 | See (Porter et al. 1952), 11 for “double-scene” and (Hermann 1940, p. 38). |

| 23 | FHN translates this phrase with the plural “Thrones”. Maintaining the singular is preferrable, as discussed below. |

| 24 | FHN I, 195. |

| 25 | For Piankhyere’s name, see below, Notes 38–40. |

| 26 | The specifics of this translation are discussed in Note 29. |

| 27 | Here the text specifies that this god is Amun, not Amun-Re as elsewhere on the lunette. FHN I, 194. |

| 28 | See Note 27, pp. 193–94. |

| 29 | This view was noted by (Török 1997, p. 303, n. 541). |

| 30 | (Kendall 1999, p. 71). |

| 31 | Angelika Lohwasser has discussed the duality inherent in this contrast between form of Amun-Re. See (Lohwasser 2001, pp. 340–41). |

| 32 | Török, pp. 457–58, p. 495, in (Eide et al. 1996). |

| 33 | For the pectoral, see (Jost 2003). |

| 34 | (Teeter 1997, p. 7). |

| 35 | A similar construction of the gifts of Amun-Re is found on the Nastasen Stela in Figure 5. |

| 36 | For evidence of her relation to Tanwetamani, see (Breyer 2003, pp. 18–19). Török identifies Qalhata as the wife of Shabaka. See (Török 1995), Table II. Dunham and Macadam identify her as the wife of Shabataka, see (Dunham and Macadam 1949, p. 146). |

| 37 | (Breyer 2003, p. 19). |

| 38 | Dunham and Macadam (1949, p. 146). |

| 39 | FHN I, 207. |

| 40 | (Lohwasser 2001, p. 178). For linguistic analysis, see (Breyer 2003, pp. 23–31). |

| 41 | Török believes that the titles should be transcribed snt Hmt nsw (“Sister-Wife of the King”) rather than the snt nsw Hmt nsw (“Kings Sister and King’s Wife”) of FNN I, 194, in Török, The Birth of an Ancient African Kingdom, 107. |

| 42 | Dunham and Macadam (1949, p. 146). For the opinion they are different people, see (Lohwasser 2001, p. 179), and (Breyer 2003, p. 24). For summary and discussion, see (Breyer 2003, p. 24). |

| 43 | FHN II, 457. |

| 44 | FHN II, 471. |

| 45 | Dunham and Macadam suggest that Nastasen was the son of Harsiyotef, but Török disputes this as they were “separated… by two or three ruler generations”. See Dunham and Macadam, 145, Török, “Nastasen. Evidence for Reign”, in FHN II, 468. |

| 46 | (Kormysheva 1999, pp. 239–40, 246). |

| 47 | (Hofmann 1971, pp. 37–38). |

| 48 | (Lohwasser 2001, p. 172). |

| 49 | (Kormysheva 1999, p. 241). |

| 50 | The duality of the masculine king and feminine mother or wife is also notable, as is the notion of generational duality, i.e., the elder (mother) and younger (king and wife). For these notions, see (Lohwasser 2001, pp. 338–41). |

| 51 | Pope illustrates that the methods used to administer Kushite control over territory were varied and adapted to the particular needs of the area. This variance does not preclude the unity of the kingdom under one Kushite ruler. See (Pope 2014, pp. 275–92). |

| 52 | See (Breyer 2003, p. 63), for a summary of and counter to Török’s argument that the double uraeus does not represent Nubia and Egypt. |

| 53 | For the double uraeus and streamers as markers of Kushite kingship, see (Török 1987, pp. 6–7, 11). For attestations od the double uraeus before the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, see (Russmann 1974), pp. 37–41. |

| 54 | For dress, see Breyer, 61–62 and (Lohwasser 1999, pp. 587–89). For the cap and uraeus, see (Lohwasser 2001, pp. 219–20). |

| 55 | (Lohwasser 1999, pp. 589–91). |

| 56 | (Lohwasser 2001, pp. 263–64). |

References

- Bellomo, Michele. 2021. Antonio Gramsci between Ancient and Modern Imperialism. In Antonio Gramsci and the Ancient World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bestock, Laurel. 2020. Egyptian Fortresses and the Colonization of Lower Nubia in the Middle Kingdom. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Edited by Bruce Beyer Williams and Geoff Emberling. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 271–88. [Google Scholar]

- Boozer, Anna L., Bleda S. Düring, and Bradley J. Parker. 2020. Archaeologies of Empire: Local Participants and Imperial Trajectories. School of Advanced Research, Advanced Seminar. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breyer, Francis. 2003. Tanutamani: Die Traumstele und ihr Umfeld. Ägypten und Altes Testament. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Budge, Ernest Alfred Wallis. 1904. The Gods of the Egyptians, or, Studies in Egyptian Mythology. London: Methuen & Co., vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Paul J. 2019. Roman Imperialism. Brill Research Perspectives in Ancient History 2: 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham, Dows, and M. F. Laming Macadam. 1949. Names and Relationships of the Royal Family of Napata. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 35: 139–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, Tormod, Tomas Hägg, Richard Holton Pierce, and László Török, eds. 1994. Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD.: Vol. I: From the Eighth to the Mid-Fifth Century BC. Bergen: Klassisk Institutt, Universitetet i Bergen, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, Tormod, Tomas Hägg, Richard Holton Pierce, and László Török, eds. 1996. Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD.: Vol. II: From the Mid-Fifth to the First Century BC. Bergen: Klassisk Institutt, Universitetet i Bergen, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Eltze, Elizabeth. 2017. The Creation of Royal Identity and Ideology through Self-Adornment: The Royal Jewels of the Napatan and Meroitic Periods in Ancient Kush. In Constructing Authority. Prestige, Reputation and the Perception of Power in Egyptian Kingship: 8. Symposium Zur Ägyptischen Königsideologie/8th Symposium on Egyptian Royal Ideology, 1st ed. Edited by Tamás A. Bács and Horst Beinlich. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Eduardo. 2019. The Lower Nubian Egyptian Fortresses in the Middle Kingdom: A Strategic Point of View. Athens Journal of History 5: 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzoli, Roberto. 2003. Piye Imitates Thutmose III: Trends in a Nubian Historiographical Text of the Early Phase. In Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century: Proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists, Cairo, 2000. Edited by Lyla Pinch Brock and Zahi Hawass. Cairo and New York: American University in Cairo Press, vol. 3, pp. 204–12. [Google Scholar]

- Grimal, N.-C. 1981. Quatre Stèles Napatéennes Au Musée Du Caire, JE 48863-48866: Textes et Indices. Mémoires Publiés Par Les Membres de l’Institut Français d’archéologie Orientale. Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, vol. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, Alfred. 1940. Die Stelen Der Thebanischen Felsgräber Der 18. Dynastie. Ägyptologische Forschungen. Glückstadt: Augustin, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, Inge. 1971. Studien Zum Meroitischen Königtum. Monographies Reine Élisabeth. Bruxelles: Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Shih-Wei. 2020. A Comparison of Figurative Language in Royal Inscriptions: A Case Study of the Stelae of Thutmose III and Pi(Ankh)y. In Ancient Egypt 2017: Perspectives of Research. Edited by Joanna Popielska-Grzybowska, Maria Helena Trindade Lopes, Ronaldo Guilherme Gurgel Pereira and Jadwiga Iwaszczuk. Warsaw: Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences (IKŚiO PAN), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen-Winkeln, Karl. 2009. Inschriften Der Spätzeit III: Die 25. Dynastie. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, Melanie. 2003. Ikonographie und Bedeutung Einer Hybriden Pektoralgruppe. In Menschenbilder—Bildermenschen: Kunst und Kultur Im Alten Ägypten. Edited by Tobias Hofmann and Alexandra Sturm. Norderstedt: Books on Demand, pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Timothy. 1999. The Origin of the Napatan State: El Kurru and the Evidence for the Royal Ancestors + Appendix: The Kurru Skeletal Material in the Museum of Fine Arts. In Studien Zum Antiken Sudan: Akten Der 7. Internationalen Tagung Für Meroitische Forschungen Vom 14. Bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/Bei Berlin. Edited by Petra Andrássy and Steffen Wenig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 3–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kormysheva, Eleonora. Y. 1999. Remarks on the Position of the King’s Mother in Kush. In Studien Zum Antiken Sudan: Akten Der 7. Internationalen Tagung Für Meroitische Forschungen Vom 14. Bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/Bei Berlin. Edited by Petra Andrássy and Steffen Wenig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 239–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, Rennan, and Julia Budka. 2021. Alternatives to Colonization and Marginal Identities in New Kingdom Colonial Nubia (1550–1070 BCE). World Archaeology 53: 401–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepsius, Richard. 1973. Denkmäler Aus Aegypten Und Aethiopien Füfte Abteilung. Geneva: Editions de Belles-Lettres, vol. 10. First published in [1849–1859]. [Google Scholar]

- Lohwasser, Angelika. 1999. Die Darstellung Der Tracht Der Kuschitinnen Der 25. Dynastie. In Studien Zum Antiken Sudan: Akten Der 7. Internationalen Tagung Für Meroitische Forschungen Vom 14. Bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/Bei Berlin. Edited by Petra Andrássy and Steffen Wenig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 586–603. [Google Scholar]

- Lohwasser, Angelika. 2001. Die Königlichen Frauen Im Antiken Reich von Kusch: 25. Dynastie Bis Zur Zeit von Nastasen. Meroitica, Schriften Zur Altsudanesischen Geschichte und Archäologie. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Mariette, Auguste, and Gaston Maspero. 1889. Monuments divers recueillis en Égypte et en Nubie. Paris: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Ellen. 2018. Ancient Egyptian Imperialism. Hoboken and Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, Jeremy. 2014. The Double Kingdom under Taharqo: Studies in the History of Kush and Egypt, c. 690–664 BC. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Bertha, Rosalind L. B. Moss, and Ethel W. Burney. 1952. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings VII: Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner, George A. 1917. The Barkal Temples in 1916. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 4: 213–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, George A. 1931. Inscribed Monuments from Gebel Barkal. Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 66: 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, George A., and Mary B. Reisner. 1933. Inscribed Monuments from Gebel Barkal. Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde 69: 24–39, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russmann, Edna R. 1974. The Representation of the King in the XXVth Dynasty. Monographies Reine Élisabeth. Bruxelles: Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Brooklyn: The Brooklyn Museum, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbahy, Lisa K. 2021. Kingship, Power, and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt: From the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Thomas. 2015. The Gebel Barkal Stelae and the Discovery of Ancient Nubia: Auguste Mariette’s Inspiration for Aïda. Near Eastern Archaeology 78: 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Stuart Tyson. 1995. Askut in Nubia: The Economics and Ideology of Egyptian Imperialism in the Second Millennium B.C. Studies in Egyptology. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. [Google Scholar]

- Spalinger, Anthony. 2023. Fortresses as Ideological Images of Power. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 109: 159–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeter, Emily. 1997. The Presentation of Maat: Ritual and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, vol. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Török, László. 1987. The Royal Crowns of Kush: A Study in Middle Nile Valley Regalia and Iconography in the 1st Millennia B.C. and A.D. BAR International Series; Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, vol. 338. [Google Scholar]

- Török, László. 1995. The Birth of an Ancient African Kingdom: Kush and Her Myth of the State in the First Millennium BC. Cahiers de Recherches de l’Institut de Papyrologie et d’Égyptologie de Lille, Supplément. Lille: Université Charles-De-Gaulle, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Török, László. 1997. The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Handbuch Der Orientalistik, Erste Abteilung: Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten/Handbook of Oriental Studies, Section 1: The Near and Middle East. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Török, László. 2002. The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art: The Construction of the Kushite Mind, 800 BC7–300 AD. Probleme Der Ägyptologie. Leiden, Boston and Köln: Brill, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Zangani, Federico. 2022. Globalization and the Limits of Imperialism: Ancient Egypt, Syria, and the Amarna Diplomacy. Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).