Abstract

In the context of the Catholic Reformation serious concerns were expressed about the affective potency of naturalistic depictions of beautiful, sensuous figures in religious art. In theological discourse similar anxieties had long been articulated about potential contiguities between elevating, licit desire for an extraordinarily beautiful divinity and base, illicit feeling. In the later fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, in the decades preceding the Council of Trent, a handful of writers, thinkers and artists asserted a positive connection between spirituality and sexuality. Leonardo da Vinci, and a group of painters working under his aegis in Lombardy, were keenly aware of painting’s capacity to evoke feeling in a viewer. Pictures they produced for domestic devotion featured knowingly sensuous and unusually epicene beauties. This article suggests that this iconography daringly advocated the value of pleasurable sensation to religiosity. Its popularity allows us to envisage beholders who were neither mired in sin, nor seeking to divorce themselves from the physical realm, but engaging afresh with age-old dialectics of body and soul, sexuality and spirituality.

Keywords:

Marsilio Ficino; Neoplatonism; Leonardo da Vinci; beauty; sexuality; spirituality; Catholic Reformation; Milan; sacred eroticism; Judah Abravanel; Dialoghi d’amore; Council of Trent; Gabriele Paleotti; Mary Magdalene; Vittoria Colonna; Titian; Giampietrino; John the Baptist; Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio; Marco d’Oggiono; Francesco Napoletano; Mario Equicola; Niccolò da Correggio; Antonio Fregoso 1. Sacred and Profane

In The Power of Images, David Freedberg bemoaned the tendency of twentieth-century art historical scholarship to overlook the ‘sexual invitation’ of much Italian Renaissance art, often in favour of convoluted and evasive interpretations based on ‘Neoplatonic allegories’.1 In his formulation, the image’s capacity to induce a ‘plainly erotic’ response is at odds with its esoteric, mystical, philosophical or spiritual affectivity.2 It can function one way or the other, but cannot simultaneously do both. Many early modern thinkers would have agreed. The affective potency of beauty, sensuality and desire were widely acknowledged, but when this shaded into concupiscence it obstructed sanctity. In theological terms, exchanges of ecstatic love with the divine were commonly said to necessitate the suppression of bodily sensation and to therefore be the diametric opposite of the physical union of two bodies in sexual intercourse. Renaissance Neoplatonism, although not a rigidly coherent philosophical system, was defined by its emphasis on both beauty and chaste love.3 One of its key proponents, Marsilio Ficino, argued that encounters with a beautiful beloved impelled the soul to recollect the celestial loveliness from which it was derived, prompting its ascent: ‘beautiful things are like divine things and have an affinity with them’, he explained.4 However, he took great pains to emphasise that ‘the desire for coitus (that is, for copulation) and love are… opposite’.5 A fully sensory, embodied response to an attractive individual was a potent spiritual tool, but only if it sparked love that was pure and devoid of eroticism.

In the Tridentine era, reformers, theologians and art theorists sought to reinscribe a clear and impregnable boundary between the sacred and the profane. Grave concern was expressed over the difficulties that many impressionable and uneducated souls encountered in making this distinction. As Cesare Trevisani’s 1569 L’impresa conceded, a kiss could be either a ‘sign of peace to sacred things’ or ‘lustful and lascivious’.6 In 1563, the Council of Trent decreed that ‘all lasciviousness’ in religious images should ‘be avoided’ and ‘that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust’.7 Authorities such as Andrea Gilio and Gabriele Paleotti issued stark warnings of the libidinous potential inherent in some religious imagery.8 This was an era when artists’ skill was measured by their ability to convince beholders that they were in the presence of a living being, and to elicit the desire to touch. In the late fifteenth century, Savonarola had broadcast the dangers inherent in naturalism, censuring ‘painters who make figures that appear alive’ as this could lead to sin.9

This fear was not new: Bernardino of Siena recalled ‘a person who, while contemplating the humanity of Christ suspended on the cross… sensually and repulsively polluted and defiled themselves’.10 But the clamour of voices warning of these dangers intensified in the climate of moral apprehension that defined the Catholic Reformation. Vasari confirmed that pictures of ‘religious and holy subjects… often arouse in men’s minds evil appetites and licentious desires’.11 He told of a man who ‘was displeased with certain painters who were not able to paint anything but lewd things’ and who therefore requested ‘a picture of a Madonna who was virtuous, elderly and did not lead him to lasciviousness’.12 Although the anecdote took the form of an irreverent joke (the man was supplied with a suitably uninviting image of the Virgin sporting a beard), its implications are significant: that images of youthful Virgins were not just able but likely to provoke lascivious thoughts. In another often-referenced tale, Vasari spoke of a Saint Sebastian by Fra Bartolommeo displayed in a church. The figure was ‘naked, with wonderful similitude in the colouring of the flesh, a sweet mien, and with equally fine corresponding beauty of person’.13 The saint’s ‘leggiadria e lascivia imitazione del vivo’ proved the artist’s skill. But it also provoked shockingly sexual responses in worshippers, sending them scurrying to the confessional to unburden themselves of dirty thoughts. The horrified friars had the offending painting removed. The moral was clear: a picture’s capacity to enflame a beholder with sexual desire was in stark opposition to its ability to bring him or her closer to God.

And yet, across the course of the sixteenth century there emerged an insatiable demand for images of rousingly beautiful religious figures. Numerous works of art insistently confronted viewers with expanses of naked flesh—flesh that was not broken, scourged or bleeding, but youthful, supple and soft. Tridentine authorities were not imagining things: images abounded in which, but for carefully placed attributes and narrative framing, Christ or Saint Sebastian could be mistaken for Apollo, the Madonna or Mary Magdalene for Venus. Recognising this perilous overlap, the disquieted owner of a ‘beautiful painting… of a nude Venus… ordered a worthy painter to dress the nude body with a hairshirt’, thus transforming a ‘lascivious’ image into a ‘virtuous’ one of the penitent Magdalene.14 But, as Maria H. Loh highlights in her study of these discourses, ‘the early modern spectator could still sense the spectre of the unreconstructed Venus lingering in the shadows and haunting the imagination that could be disciplined but not entirely controlled’.15 Indeed, very often the spectre of tumescent arousal did not so much linger in the shadows as thrust itself invitingly into the viewer’s perception. As Loh concedes, images such as Orazio Gentileschi’s early seventeenth-century depiction of a sensuous and passive Pentient Magdalene indicate how often ‘the artist trumped the censor’ (Figure 1).16

Figure 1.

Orazio Gentileschi, The Penitent Magdalene, c. 1622/28, Kunsthistoriches Museum. © KHM-Museumsverband.

Why were works of art featuring invitingly lovely holy subjects that contravened the new climate of moral absolutism so popular? Did beholders necessarily expose themselves to sin by commissioning and buying such works, and if so, why? Freedberg encourages us to believe that the reasons lay in bodily impulses which are in inherent conflict with more elevated aims or experiences. Is that really what was going on? These are expansive and complex questions, and to attempt a fulsome answer to them is outside the scope of this article. My intention here is to begin to unfurl some of the histories that preceded and informed mid-sixteenth-century anxiety about sexual responses to religious art. My focus will initially be wide in its temporal scope, taking account of longstanding cultural and theological discourses, before narrowing to examine the iconographic contributions of a handful of artists working in Lombardy in the ambit of Leonardo in the late fifteenth century and early sixteenth century. Tentatively, I shall probe the assumption that for early modern beholders, the sexual and the spiritual were necessarily always in opposition. Carefully, I want to explore the possibility that for some artists and patrons, erotic feeling had the potential to be fruitfully harnessed towards spiritual enlightenment.

2. Sacred Eroticism

In the widely read mid-fourteenth-century Incendium Amoris, Richard Rolle asserted that there were two routes to a state of extreme devotion: ‘one way is to be rapt by love while retaining physical sensation, and the other is to be rapt out of the senses by some vision, terrifying or soothing. I think that the rapture of love is better, and more rewarding’ (my emphasis).17 Despite the influence of Platonism, which taught that the soul yearned for release from the incarceration of corporeal matter, the body and its sensory apparatus were central to early modern religiosity. Aristotelian understanding of the intimate interdependence of body and soul was foundational to Christian doctrines that affirmed the place of somatic matter to spiritual life. Augustine and Bernard of Clairvaux taught that God could be known through the senses, and from the thirteenth century onwards the centrality of incarnational theology to Dominican and Franciscan thought had enormous influence: pilgrims journeyed miles to see fragments of holy bone, the touch of a sacred object to the skin banished sickness, and Christ’s embodiment was eulogised as the ultimate expression of God’s love for mankind.18 Thomistic theology emphasised that the soul found expression through corporeality and that the physical self was vital to spiritual identity. For Aquinas, it was ‘natural’ and ‘fitting’ for man to seek spiritual truths via ‘sensible objects’ and ‘material things’.19 Man was made in God’s image, and the divine had taken human form: it was ‘by the mysteries of His bodily life’ that Christ would ‘recall man to spiritual life’.20 This was powerfully confirmed during the sacrament of the Mass, when devotees absorbed the transubstantiated flesh and blood into their own forms.

The conviction that God could be known in a fully embodied way, and that Christians should open their hearts and souls to the deity’s immense love, shaped discourse in sometimes startling ways. Grasping for language to describe the astonishing experience of proximity to the divine, writers across the ages turned to analogies of erotic arousal and sexual union. In the third century, Origen likened God’s feelings for mankind to passion and compared Christ to Amore or Eros.21 Three centuries later, Pseudo-Dionysius advised that the minds of devout worshippers could penetrate Christ, and his spirit fill their bodies in an exchange of ecstatic love.22 Bernard of Clairvaux urged twelfth-century devotees to ‘Let the Lord Jesus be pleasurable and sweet in your affection’ and compared the ensuing sensation to ‘the wickedly sweet enticements of sensual life’.23 Aquinas, quoting St. John Chrysostom, explained that ‘Christ offers himself to us desiring to touch… Let us mix with that flesh…that he may show us with how much love he burns towards us’.24 For Richard Rolle, ‘the devout mind, inflamed by the fire of Christ’s love and filled with desire for heavenly joys’ would be like a lover, thirsting to ‘achieve his desire… [in] his Love’s arms’.25

It is important to acknowledge that amatory responses to holy figures could be free from the tinge of eroticism: it was possible for feeling that appears sexually charged to modern sensibilities to be avowedly sanctified. Speaking of ideal spiritual love, religious authorities repeatedly invoked discourses of intense amour, without this necessarily indicating concupiscence.26 The eighth-century Carolingian court theologian Saint Alcuin wrote to a bishop: ‘I think of your love and friendship with such sweet memories, reverend bishop, that I long for that lovely time when I may be able to clutch the neck of your sweetness with the fingers of my desires… how I would sink into your embraces… I [would] cover, with tightly pressed lips… your eyes, ears and mouth… not once but many a time’.27 In the twelfth century, Saint Aelred of Rievaulx declared the ‘intimate loves’ of the cloister to be akin to marriage. The tender passion that united Christ with John the Evangelist in ‘heavenly marriage’ provided an irreproachable template for these bonds, as depictions of the (invariably young and beautiful) disciple lying in Christ’s lap at the Last Supper eloquently communicated.28

Yet, despite these unimpeachable examples, Church authorities recognised the encroachment of eros into religious experience. The sixth-century theologian Philoxenos of Mabbug conceded that passion for God could be ‘akin to the passion of fornication’.29 Aelred of Rievaulx acknowledged that the sin of ‘concupiscence of the flesh’ stalked his ideal of deep monastic love and that it was particularly difficult for the young to ‘discern licit from illicit’ sensations.30 This concern crystallised in the sixteenth century, when Saint John of the Cross wrote anxiously that

The overt spirituality of a body did not negate its sexuality. In Venice in 1420, a group of Franciscan friars was arrested for processing naked; the case was passed to the body responsible for investigating sodomy and related crimes.32 Although the friars were not charged, their nudity was censured. Hagiographies spoke of carnal desire for saintly individuals whose purity manifested in arousing bodily beauty. To give just one example, the pious maiden Euphrosyne (one of many young women in such tales who donned male clothing to enter a monastery and avoid marriage) provoked ‘evil thoughts’ among their fellow monks.33…it often comes to pass that, in their very spiritual exercises… there arise and assert themselves in the sensual part of the soul impure acts and motions, and sometimes this happens even when the spirit is deep in prayer… For when the spirit and the sense are pleased, every part of a man is moved by that pleasure to delight…31

Mid-sixteenth-century reformers were newly alert to the imminence that had long existed between the realm of devotion and apparently secular cultural manifestations. Medieval love lyric and the chivalric tradition mined a rich and pervasive vein of correspondence between sexual and spiritual love.34 A form of sacred eroticism suffused tales of self-sacrificial heroes assailed by desire for beautiful virgins, inviting comparison with martyrdom or Christ’s death.35 Origen was not the only one to liken Christ to Amore, and this analogy worked both ways. A religious text contemporary with the Roman de la Rose identified Christ as the chivalric lover who picked the rose from the garden at the story’s denouement.36 Numerous artists and writers drew an equivalence between holy figures and sensuous counterparts: the Virgin as a celestial Venus, Christ as Apollo, Saint Augustine wielding Cupid’s arrows.37

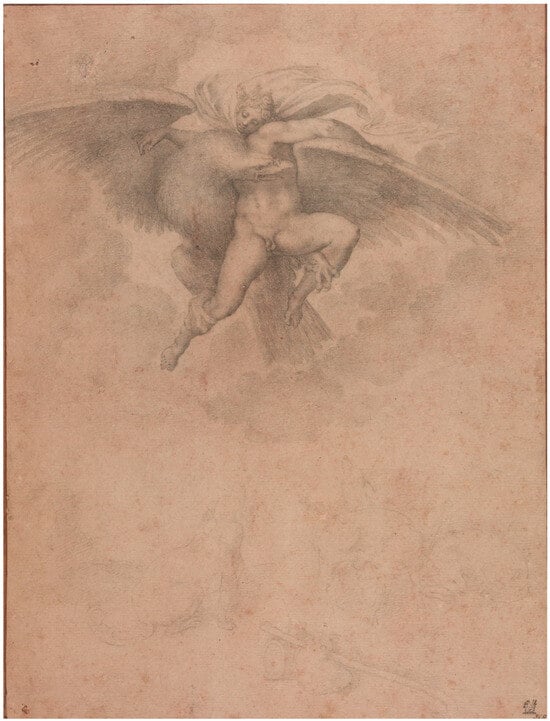

On occasion, devotees conceptualised sanctified relationships (whether with the divine, a spiritual companion, a bosom friend or a lover) in carnal terms that conflated fervent love with sexual feeling. Commentaries on the bridal imagery of the Canticles conferred religious significance on erotic love between man and wife.38 Later, Christian commentators on the Symposium adapted the carnal aspects of Plato’s philosophy (the forceful argument that sexual desire framed and intensified the edifying effects of love), drawing parallels with biblical passages such as the Song of Songs.39 When Ganymede’s rape was read as a metaphor for the ecstatic rapture of the soul, the power of sexual feeling was appropriated for religiosity, rather than being expunged.40 Michelangelo’s presentation drawing of this scene for his beloved Tommaso de’ Cavalieri potently made this analogy by visual means (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Copy after Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ganymede, sixteenth century, Harvard Art Museums © Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gifts for Special Uses Fund.

One of the clearest and most unabashedly positive expressions of this correspondence appears in Judah Abravanel’s influential Dialoghi d’amore, written in the early years of the sixteenth century and published posthumously in 1535.41 The text synthesises aspects of Aristotelian, Neoplatonic and Jewish traditions (among others) and was widely read after its publication.42 In the first dialogue, the lover Philo argues that sexuality is a proper vehicle for the expression of love. He asserts that ‘the union of copulation… makes possible a closer and more binding union, which comprises the actual conversion of each lover into the other, or rather the fusion of both into one… Thus the love endures in greater unity and perfection’.43 ‘Spiritual’ love ‘of wonderous depth’ arising from ‘reason and knowledge’ is acknowledged to be distinct from base carnal desire. Yet, in a daring departure from the usual Neoplatonic reasoning, Philo declares that this pure and admirable love is only increased by ‘carnal joy’.44 Physical consummation is directly analogous to love for God: ‘Who can deny that [this] good love may comprise wonderous and boundless desires? What love is nobler than love of God: what is more ardent and boundless?’45 He reiterated this point in the third dialogue, in a recalibration of the Genesis story’s relationship to Plato’s primordial androgyne.46 The impulse towards sexual union with a virtuous beloved sprung from the same root as yearning for unity with the deity: ‘this desire and love is absolutely virtuous, and the more ardent it is, the more praiseworthy and perfect’.47

Similar positions, if less fully articulated, appear elsewhere in early modern literature. A circle of Lyonnaise literati, including Maurice Scève and Antoine Héroet, produced love poems that drew heavily on Petrarch and Ficino but (at times) downplayed the need for chastity. (Significantly, the erudite printer Jean de Tournes, who introduced the public to their work, published a French translation of Abravanel’s Dialoghi d’amore in 1551.) The works of Jorge de Montomayor, Pierre de Ronsard, John Donne and Edmund Spenser reverberated with analogous themes; in a sonnet addressed to his paramour, Spenser deemed romantic love ‘the lesson which the Lord us taught’ by the example of His powerful love for mankind.48

3. The Beautiful Divinity

Central to the discourses I have outlined was the conviction that extraordinary beauty, itself a manifestation of spiritual perfection, stimulated love for the deity. The Augustinian belief that beauty was a divine attribute indicating ‘God’s presence’ in an object was far-reaching and pervasive; it persistently articulated the indissolubility of body and soul.49 For Richard Rolle, to be ‘inflamed by the fire of Christ’s love’ was to be consumed body and soul by ‘love for the unseen Beauty’, to the point of ecstatic death.50 No self-respecting visionary failed to mention the dazzling loveliness of the holy figures she or he encountered, and ordinary believers were regularly encouraged to meditate on this defining characteristic. Jeanne des Anges, the superior of an Ursuline house in seventeenth-century Loudon, described the guardian angel who appeared to her as a blond adolescent boy ‘of rare beauty’.51 As Caroline Bynum’s pioneering work highlights, The Golden Legend repeatedly deemed saints’ bodies to be free from the decay of aging and asserted that Christ’s ‘holy body’ would never ‘see [the] corruption’ of decrepitude.52 The thirteenth-century French nun and mystic Marguerite of Oingt likewise explained that bodies in the celestial realm were composed ‘of such noble matter that they can no longer corrupt nor grow old’.53 She instructed the faithful to contemplate Christ’s ‘great beauty, so great that he has granted [it] to all the angels and all the saints who are his members, that they may be as clear as the sun’.54 The apocryphal description of Christ supplied in the letter of Lentulus, which was well known in early modern Europe, deemed Him ‘the most beautiful amongst the children of men’.55 The perfection of the embodied Christ’s material form was the ultimate proof of the loving covenant between God and humanity, and yearning for union with Him was a mainstay of pre-modern religiosity. ‘Tell my Beloved I am pining for love’ Rolle beseeched, ‘Come down, Lord. Come, Beloved, and ease my longing’.56 Such rhetoric was commonplace: preachers and priests described Jesus as a transcendently lovely spouse, and numerous visionaries spoke of their bodily hunger for Him and the exquisite pleasure that accompanied its satisfaction.57 The expression of desire for an alluringly beautiful divinity was a well-established, licit aspect of Christian faith.

Aesthetic ideals are never constructed in cultural isolation: ‘beauty’ derives its potency from broad consensus over what constitutes this quality. Religious discourse drew on, and contributed to, parallel secular celebrations of youthful loveliness, each serving to affirm and intensify the other. For both men and women Petrarchan standards dominated: one need not have read the Canzoniere to know that the loveliest individuals were in the first flush of youth, with shining golden hair and a ‘dolce viso’ that was smooth, unblemished and pale. These were the qualities that inflamed desire, as poets and literati repeatedly emphasised. Unsurprisingly, this ideal informed sexual behaviour.58 It also shaped religious practice in myriad ways. In fifteenth-century Florence fanciulli in angelic garb processed around the city and appeared in religious theatricals.59 Chosen for their looks, and consequent ability to evoke divine perfection, these youths possessed the same beauty that was desired in sexual conquests (by both women and older men).

The impossibility of demarcating separate ideals of celestial and erogenous perfection was a particularly acute problem for advocates of Neoplatonism. Rather awkwardly, Ficinian promotion of chaste, elevating love between men and beautiful youths mapped precisely onto contemporary sexual practices.60 This was the correspondence that so troubled mid-sixteenth-century reformers. It was commonly acknowledged that sodomites were attracted to beautiful youths with smooth visages: ‘those who don’t yet visit the barbers’, as one poet wryly put it.61 Gilio’s complaint that Michelangelo’s Sistine Christ ought to be bearded was therefore loaded.62 Reformers’ worst fears were born out by cases such as that of the abbess Benedetta Carlini, which occurred in early seventeenth-century Tuscany. The nuns testified that when Carlini experienced holy visitations she took on the angelic appearance of a particularly lovely boy of around fifteen, fittingly named Splenditello.63 It was in this guise that she had sex with another nun.

4. Images

How did religious imagery participate in and shape these discourses? Affectivity was critical to visual cultures of early modern Catholicism, and so too was beauty. The conviction that depicted loveliness could captivate the attention and induce both intense pleasure and spiritual revelation was widespread.64 In the sixteenth century, Catholic defenders of religious art reiterated this argument with conviction. Gabriele Paleotti advised that the most effective tools available in the effort to shape the soul were ‘well-executed painted panels that impress on our senses the thing that we most desire’ [my emphasis].65 He avowed that ‘while knowledge learned from books is acquired only with great effort and cost, we learn from images with great sweetness and levity’, and declared that the capacity of Catholic imagery to ‘supply delight’ went hand-in-hand with its ability ‘to instruct, and to move the emotions of the observer’.66 Pleasure summoned a worshipper to repeated engagement with a work of art, thereby deepening his or her piety. Yet, (as Gilio’s concern about Michelangelo’s dangerously youthful Christ highlights) the line between licit and illicit loveliness was often so thin as to be indistinguishable, and even the most decorous image could prompt sin in a weak or immoral beholder.

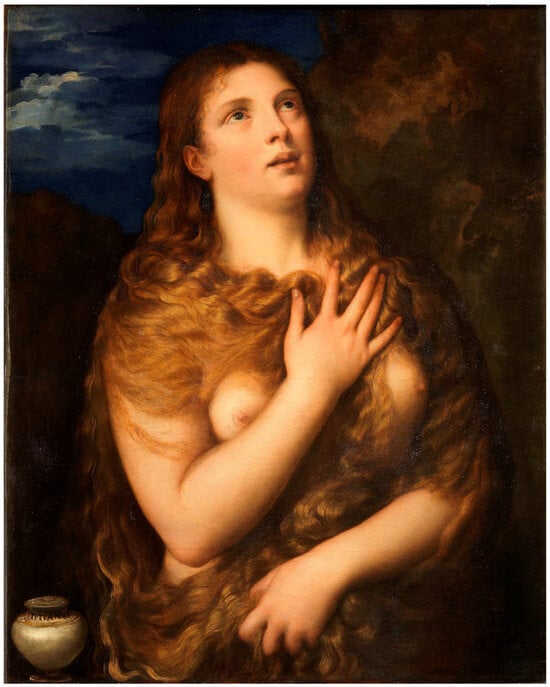

The iconography that has received the most attention from art historians interested in these questions is that of Mary Magdalene. Depictions of the luscious saint in the wilderness, resplendent in her naked loveliness, became increasingly popular over the course of the sixteenth century. Historically, scholarly interpretations have tended to fall into two camps, broadly divided along the lines indicated by Freedberg: either these pictures are read as evocations of the need to attend to the realm of the body and sensuality in order to overcome and transcend it, or they are seen to extend a ‘sexual invitation’ to viewers not much concerned with the state of their souls.67

Isabella d’Este had a particular devotion to Mary Magdalene, and in 1529 the highly educated poet Countess Veronica Gambara wrote to her describing a painting of the saint that she had commissioned from Correggio: ‘the noble and lively grief on her most beautiful face are so marvellous as to stupefy the spectator’.68 Precisely the same combination was emphasised by Isabella’s son Federico Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, when in 1531 he requested from Titian ‘a St. Magdalene as tearful as possible… [and] as beautiful as you can strive to make it’ (lacrimosa più che no si può… che metterte ogni studio farlo bello) (various versions by the painter and his workshop are extant; Figure 3 may be the prototype of the iconography).69 This was probably the picture given as a gift to the noblewoman and poet Vittoria Colonna, who sought to ‘mirror herself’ in the painted figure’s ‘bello esempio’ and was moved to write a poem identifying Christ as the beautiful saint’s ‘true eternal lover’.70 In another sonnet dedicated to the Magdalene, the poet elucidated the connection between her bellezza and her status as an exemplar of ‘burning love’ for Jesus.71 Archbishop Federico Borromeo likewise noted that artists who depicted the saint ‘as a young woman of vibrant freshness’ thereby communicated that she was ‘consumed with love’ for the divine, stimulating similar sensations in beholders.72

Figure 3.

Titian, The Penitent Magdalene, c. 1531–35, Pitti Palace © Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi.

It was incumbent on female beholders, especially at the highest social levels, to avoid any hint of impropriety. This did not prevent them from deriving agency from the commissioning and viewing of works of art, nor did they have to restrict themselves to unambiguously moralising representations. Isabella made confident incursions into debates surrounding the value of Amore—but via the medium of classical mythology, not Christian iconography, and in a more relaxed pre-Tridentine context.73 Colonna was writing in the febrile religious atmosphere of the mid-sixteenth century, and her deep piety, her status as a widow, and the links she cultivated with various theological thinkers set her at a remove from earlier court culture. Although we should remain alive to the queer potentialities Titian’s imagery possessed for female viewers, the Neoplatonic flavour of Colonna’s reformist religiosity led her to place special emphasis on tearful penitence and renunciation of sin. She understood this state to be embodied in the Magdalene’s sensory appeal: to function successfully, the picture had to highlight both the saint’s loveliness and her contrition.74

Other documented Magdalenes by Titian and his workshop confirm that the iconography was equally popular among male aristocratic consumers. Francesco Maria delle Rovere, Duke of Urbino, commissioned one, and the Mantuan noble Giovan Giacomo Calandra another.75 Scholars have often surmised that the pleasure they took in these works of art was more robustly straightforward than Colonna’s. Deeming the idea that they were ‘spiritually edifying’ to be ‘unconvincing’, Franco Mormando speculates that the tale of the penitent Magdalene provided a ‘convenient pretext’ for elite men to own what Susan Haskins has dubbed a piece of ‘pious pornography’.76 Certainly a number of contemporaries focused their concerns about lascivious images on this iconography.77 Yet it does not necessarily follow that some of the most popular religious imagery of the sixteenth century was knowingly created and employed for sinful ends, as a straightforward prompt to concupiscence. In a society where wealthy men had ready access to more explicitly arousing, far less transgressive depictions of delectable Venuses, nymphs and other mythological beauties, it seems incumbent on us to consider alternative possibilities. Without denying the titillating potential of that which is taboo, the intellectual and devotional traditions I have surveyed suggest more nuanced readings of the relationship between physical pleasure and religious experience. We must be alive to the creative vibrancy of early modern visual culture: to artists’ capacity to devise imagery that was complex, multivalent and potently disturbing. As sensitive analyses by a number of scholars have revealed, artists rose to the challenge of interweaving sensory and spiritual in their work.78

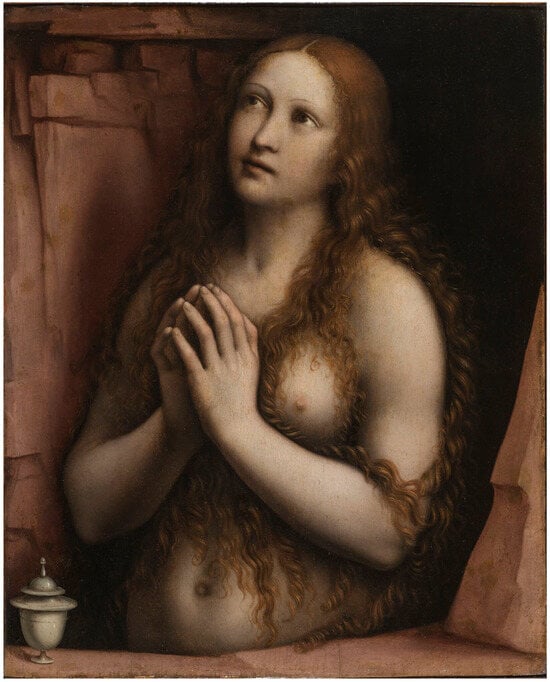

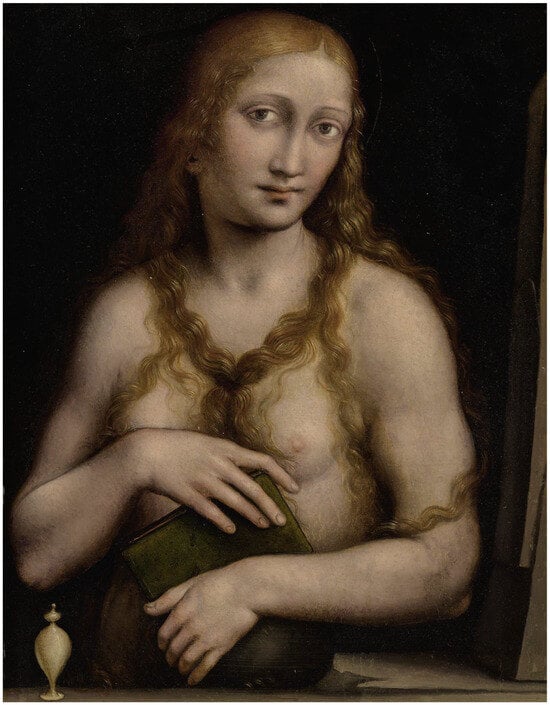

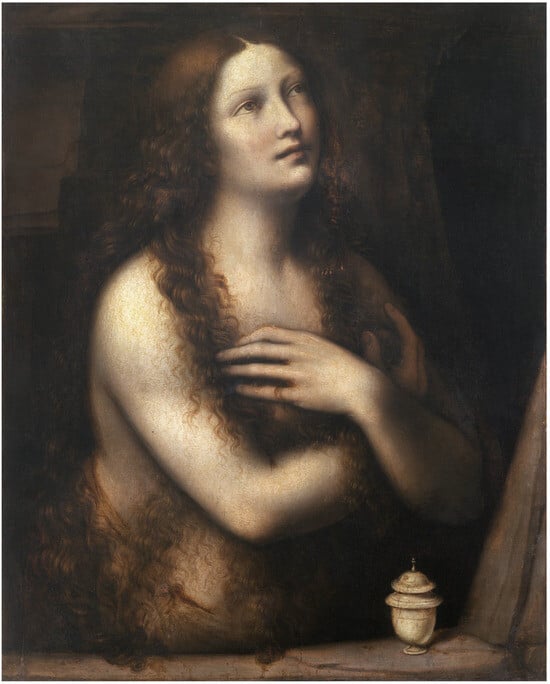

Titian’s popular imagery of the Magdalene had a specific derivation: numerous half-length depictions of the saint, made for domestic devotion, that the Lombard painter Giampietrino and his associates produced in the first half of the sixteenth century (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). In this iconography the saint is often unrobed, her abundant tresses simultaneously concealing and revealing her nakedness. Standing or kneeling in a rocky grotto, she variously reads, contemplates a crucifix, prays or turns her eyes to heaven. In some instances she touches her fingers to her chest, often having gathered her hair in her hand. Although she is doubtless penitent, she lacks the insistently tearful compunction of Titian’s iteration. The focus is on her somatic perfection, encouraging lingering concentration not on her emotional state but on the sensory reality of the encounter with her. In the version in the Hermitage she is clad only in her lustrous mane, and a perfect breast is insistently revealed (Figure 4). In another the naked saint no longer holds up her hands in prayer, and she turns her gaze not to the heavens but directly to the viewer (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Giampietrino (Gian Pietro Rizzoli), Repentant Mary Magdalene, between 1508 and 1549, Hermitage © The State Hermitage Museum/Photo by Pavel Demidov.

Figure 5.

Anonymous, The Penitent Magdalene, first half of sixteenth century, private collection © Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, 2024.

Figure 6.

Giampietrino (Gian Pietro Rizzoli), Half Figure of Saint Mary Magdalene, 1525-30, Brera Gallery © Pinacoteca di Brera, Milano.

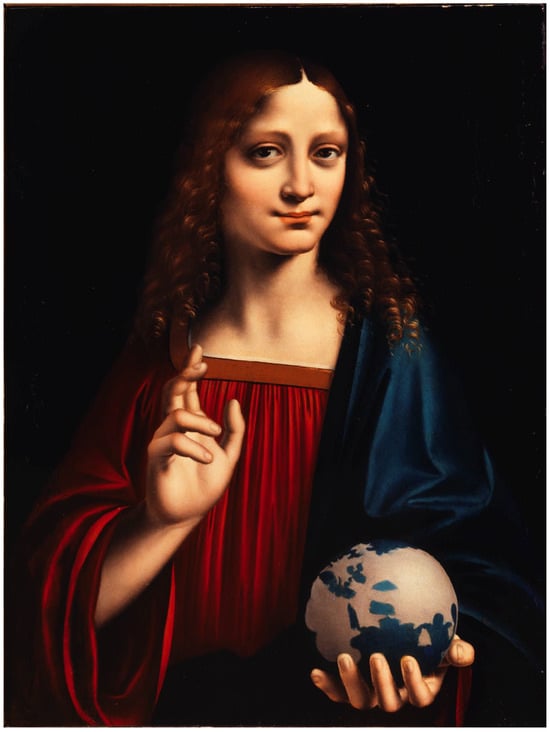

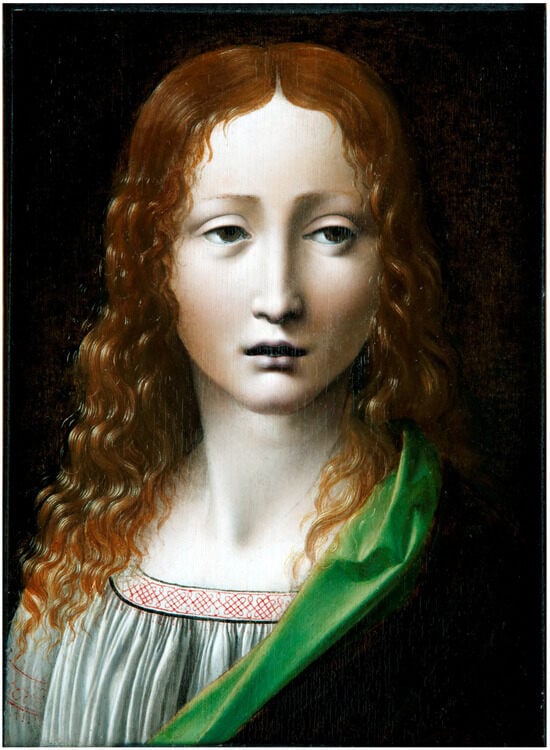

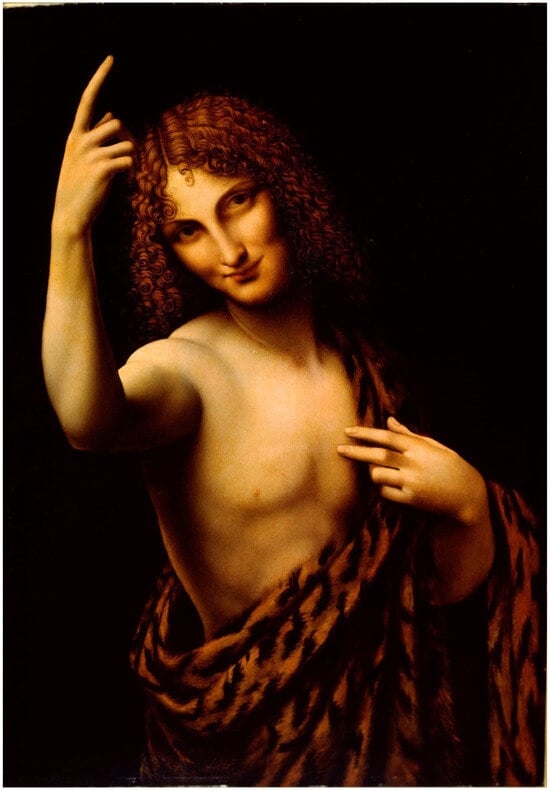

Giampietrino was not the sole progenitor of this striking iconography, which Titian so clearly appreciated. These pictures are intimately related to a body of works that emerged from Leonardo’s Milanese studio in the preceding years. This imagery continued to be popular and influential in northern Italy, and Giampietrino knew it well. The subjects are myriad: the Madonna, Christ, various saints and contemporary sitters (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13). All share a particular youthful, ephebic beauty—the careful construction of Leonardo and artists working under his aegis, including Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Marco d’Oggiono and Francesco Napoletano. The ideal in question is the result of considered and theoretically informed workshop practices. It is deliberately androgynous and was applied to both male and female subjects.79 Some are the forebears of Giampietrino’s Magdalene: near-naked holy figures whose potency derives from their youthful beauty. One subset of images features interchangeably John the Baptist or an angel (deemed the Angel of the Annunciation in the literature) (Figure 12 and Figure 13).80 The Magdalene borrows the gentle touch of fingertips to skin or hair, her tumbling corkscrew curls and her lithe perfection from them.

Figure 7.

Bernardino de’ Conti, Madonna and Child, Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco © Comune di Milano/Anelli 1996.

Figure 8.

Francesco Napoletano, Madonna Lia, Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco © Comune di Milano/Saporetti 2007.

Figure 9.

Marco d’Oggiono, Salvator Mundi, c. 1490s, Galleria Borghese, Rome © Heritage Art/Heritage Images.

Figure 10.

Marco d’Oggiono(?), The Young Christ, c. 1490, Fundación Lázaro Galdiano © Museo Lázaro Galdiano.

Figure 11.

Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Portrait of a Young Man, Possibly Girolamo Casio, c. 1500 ©. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees/Bridgeman Images.

Figure 12.

Leonardo da Vinci and pupil, detail of Horses, machinery and an angel, c. 1503-4, Royal Collection, Windsor. Supplied by Royal Collection Trust/© HM Queen Elizabeth II 2015.

Figure 13.

Studio of Leonardo da Vinci, St John the Baptist, c. 1490–1510, Ashmolean Museum © By permission of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Intimate knowledge of the tastes of courtly patrons in Sforza Milan shaped this iconography; its creators were full participants in a social circle where questions of art, philosophy, theology and literature were debated.81 Members of Leonardo’s Lombard ‘academia’ celebrated this ideal’s appeal, eulogised its enriching potential and adopted it as their emblem (Figure 14). Simultaneously, in this milieu a sexual preference for young, beardless cortigiani with golden curls, pale skin and lovely features was openly professed, even acclaimed. The poet Niccolò da Correggio wrote of ‘burning’ desire for a lovely adolescent and invited his audience to imagine the ‘great benefit’ and ‘mutual pleasure’ that would accompany its satisfaction.82 While acting in a play, the court musician Atalante Migliorotti, a friend of Leonardo’s, was to declare sex with fanciulli to be ‘sweetest, softest, best’.83 Convivial homosocial gatherings enjoyed by court luminaries, including Leonardo and Boltraffio, featured bawdy articulations of same-sex concupiscence alongside erudite debates informed by humanist and artistic discourse.84 Despite some individuals’ aspirations to chaste amour (the courtier and poet Gasparo Visconti who was a key member of this circle was an ardent Neoplatonist), the archetype that proliferated in the work of these artists was widely agreed to be sexually alluring.

Figure 14.

Engraving after Leonardo da Vinci, Profile bust of a young woman with a garland of ivy in a tondo, British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Leonardo cautioned that the painter should constantly have in mind ‘the effect that you wish the figure to produce’.85 He believed that the artist’s generative capabilities could make ‘spectators stop in admiration and delight’, and that the representation of ‘human beauty will stimulate love in you, and will make your senses envious’.86 By placing ‘in front of the lover the true likeness of that which is beloved’ the artist could impel him to ‘kiss and speak to it’.87 But the painter’s creative authority was much greater than this: while the poet could never ‘describe a beauty, without basing [this] description on an actual person, and arouse men to such desires with it’, the artist could prompt love without recourse to existing feelings for a known individual. 88 Crucially, when he ‘wishes to see beauties that charm him it lies in his power to create them’.89 Having acknowledged the painter’s ability to produce an image of such beauty that ‘often the lover kisses the effigy and speaks to it’, Leonardo laid claim to precisely this authority. He recounted that he had ‘happened to make a painting which represented a divine subject that was bought by someone who loved it, who wanted to remove the divine attributes so he would be able to kiss it without misgivings. But in the end his conscience rose above his sighs and his lust, and he was forced to remove it from his house’.90 The story has a sardonic tone, but it highlights the risks run by those who contemplated paintings of extraordinary aesthetic and affective potency in domestic spaces. This was an unsupervised environment in which it was easy to slip from adoration into a startlingly libidinous response.

Yet, an alternative pathway was open to those with the capacity to harness their ‘lust’: the channelling of pleasurable sensation in pursuit of transcendence. This was acknowledged to be a delicate task, and the beholder’s share was weighty. The Sforza poet Antonio Fregoso emphasised that although ‘celestial love’ ruled in the ‘incorporeal world’, that which reigned on Earth was ‘similar’: the two loves were ‘brothers’, ‘one affects the beauty of the soul… one delights itself in the beauty of the body’.91 Both were necessary for true self-knowledge. The humanist Mario Equicola, who frequented the courts of Mantua and Ferrara and visited Milan in the later 1490s, argued that the opinion of those who believe Anteros to signify ‘love opposed and not returned’ was false. Its significance, he declared in the Libro de natura d’amore, his compendium of philosophical positions on love, was ‘mutual, equal and reciprocal love’.92 The devotional pictures issuing from Leonardo’s bottega emerged from the same permissive, erudite courtly climate. Fregoso wrote of the artist’s capacity to produce pictures that could be either ‘adored’ or considered ‘vain things’, eliciting divergent responses from viewers depending on their virtue.93 Unworthy beholders—those who were insufficiently learned and noble—would fail to recognise the invitation to elevation inherent in a dazzlingly lovely figure. Neglecting to interrogate the sensations the representation evoked, they remained fixated on its sensuous charms. The artwork therefore obscured divine truth from those who demonstrated themselves unfit to receive it, whilst guiding the honourable towards God via the pathway of desire and sensation. ‘Sitting and looking at [a] painting’ of a ‘nudo fanciul’, Fregoso reported that the image, which appeared to him ‘alive’, represented ‘holy and celestial Love’. Addressing the youth, he caustically remarked of the beholder who failed to perceive the figure’s value: ‘Either your virtues weren’t evident to him/or his good judgement was corrupted’.94 The poet concluded ‘whoever has painted him so young and so beautiful/I bless his hand, but whoever presumes/to call him blind and a rebel against piety/is profane and blind and lawless’.95

The many idealised, epicene beauties that emerged from the ambit of Leonardo’s workshop in these years fundamentally challenge the idea that Christian truth resided in a world beyond the boundaries of sensory knowledge. These figures’ appeal was embodied and tactile. Supremely confident in their ability to ‘stimulate love in you, and make your senses envious’, they make eye contact, gently smiling or with lips parted in greeting.96 In some paintings a subject’s near-nakedness is emphasised by the caress of soft animal fur against bare skin. Insistent corporeality is underlined by the touch of fingertips to the torso, a gesture that enacted the beholder’s desire for tangible contact with the depicted form, sanctioning fully sensory responses in viewers conditioned to desire attractive youths. Holy figures that touch themselves with one hand and point upwards with the other communicated that the route to heaven was via their bodies (Figure 12 and Figure 13). The sensations they stimulated were a catalyst for contemplation of the bonds of love that united man with a dazzlingly beautiful deity. The aesthetics of the artwork, the embodied act of beholding and its spiritual outcome were imbricated. Marshalling a unique capacity to awaken desire for a beautiful form that was comprehended as spiritual, these pictures asserted the central place of corporeality and sexuality to devotion. In doing so, they proclaimed the skill of their makers: as the art theorist Dolce explained, only a true master could conjure figures that possessed ‘a soft and gentle air, which charms one and sets one on fire’, but that ‘nonetheless invariably preserved… an indefinable quality of holiness and divinity’.97

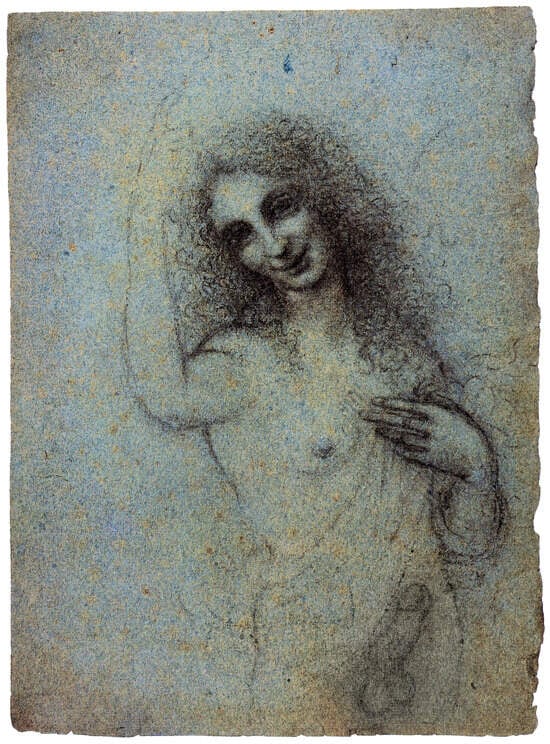

One drawing is especially insistent in its confrontation of carnal love’s proximity to spiritual ecstasy. It is of shadowy provenance; although the possibility of a clever forgery cannot be dismissed outright, a number of scholars have accepted the sheet as the production of an early modern artist who was intimately familiar with Leonardo’s work.98 A smiling epicene figure with a nimbus of tumbling curls is realised in delicate strokes of black chalk (Figure 15).99 One hand is raised in a familiar pointing gesture, and the other gently touches the breast. Unmistakably, the subject is a variation of the Angel of the Annunciation composition; the faint outline of the proper left wing is just visible, confirming that this iteration is angel rather than Baptist. Far more prominent than its celestial status, though, is the figure’s incarnate nature, for alongside its beatific attention and direct address it bestows upon the beholder a tumescent erection. It is possible that what began as a version of the Angel evolved into a bawdier celebration of the effect of the epicene type’s beauty. After all, the wing that signifies that this creature is a celestial being is only very sketchily indicated. Yet for those who knew the prototype, this drawing had the potential to communicate a positive value of a sacred eroticism akin to that articulated in Abravanel’s philosophy. It certainly seems plausible that it could be taken as a powerful statement of the value of integrating sensual experience with contemplative, even spiritual, intent. Whether this was the intention of the maker or not, any viewer familiar with the traditions outlined in this article may have interpreted it in this light.

Figure 15.

Anonymous, Angelo incarnato, sixteenth century, private collection. Digital enhancement © James Grantham Turner.

Emblematic of the affective power of the imagery under analysis is Leonardo’s Saint John the Baptist (Figure 16). Shrouded by sfumato, an eerily beautiful figure emerges from the darkness to communicate with us via enigmatic smile and pointing gesture.100 Inevitably, in the changed climate of later years this iconography attracted criticism. Speaking of a closely related image of the saint in 1625, Cassiano dal Pozzo complained that although it was ‘most delicate’, it ‘does not please because it does not arouse feelings of devotion’.101 Yet its impact reverberated across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Inevitably, when viewers were invited to contemplate depictions of lovely young saints whose extraordinary bodily beauty was on full display, this would have provoked a range of responses. On occasion these surely encompassed the straightforward lust that moralists feared, and on others the conviction that pleasurable sensation had to be denied and overcome to achieve spiritual enlightenment. But the context from which the iconography of the sensually appealing, archetypally perfect epicene youth emerged suggests other possibilities. Intriguingly, these align with ancient Christian traditions and early modern thinkers who advocated the value of amour and desire to devotion, allowing us to envisage beholders who were neither mired in sin nor seeking to divorce themselves from the physical realm but attempting the resolution of these ancient dialectics.

Figure 16.

Leonardo da Vinci, Saint John the Baptist, first quarter of sixteenth century, Louvre, Paris © Heritage Art/Heritage Images.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | (Freedberg 1989, p. 17). |

| 2 | Ibid., p. 19. |

| 3 | On this point see (Hankins 1990, 1, p. 113; p. 117). |

| 4 | (Ficino 1987); (Ficino 1985, p. 130). |

| 5 | Ibid., p. 165. |

| 6 | Cited in (Maggi 2005, p. 331). |

| 7 | (Waterworth 1848, pp. 235–36). |

| 8 | (Gilio 1960); (Paleotti 2002). |

| 9 | (Palmarocchi 1933, 3, 2, p. 98). |

| 10 | Bernardino of Siena, De inspirationibus, cited and translated in (Mills 2002, p. 163). |

| 11 | (Vasari 1966–1987, 3, p. 273). |

| 12 | Ibid., 5, p. 439. |

| 13 | Ibid., 4, p. 97. |

| 14 | Gian Domenico Ottonelli and Pietro da Cortona, Trattato della pittura, e scultura, uso et abuso loro, (Ottonelli and da Cortona 1652, pp. 326–27), cited in (Loh 2013, p. 103). |

| 15 | (Loh 2013, p. 109). |

| 16 | Ibid., p. 108. |

| 17 | (Rolle 1972, p. 166). |

| 18 | See for instance the philosophy of the influential medieval Franciscan theologian John Duns Scotus. |

| 19 | Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 1.1.9. |

| 20 | (Aquinas 1952, ch. 201, p. 216). |

| 21 | On Origen’s interpretation of Christ as the beloved bridegroom of the Canticles see (Stefaniak 1992, pp. 703–6). |

| 22 | See (Screech 1980, p. 56). |

| 23 | Cited in (Carruthers 2006, pp. 1012–13). In doing so, he advocated a turning from the sensual life of the body towards the sensual experience of Christ’s love, saying that ‘sweetness conquers sweetness as one nail drives out another’. In this discourse, the ‘sweetness’ of one was directly equated with that of the other. |

| 24 | Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 3.79.3. |

| 25 | (Rolle 1972, p. 131; p. 164). |

| 26 | On this question see (Boswell 1980); (Hyatte 1994); (Bray 2006). Boswell’s work in particular has stimulated much scholarly debate. |

| 27 | Translated and cited in (Boswell 1980, p. 190). |

| 28 | Aelred of Rievaulx, De speculo caritatis, 3. 109–10. Aelred’s theology is discussed in (Boswell 1980, pp. 221–26, citation at p. 226). |

| 29 | Cited in (Brown 2002, p. 492). |

| 30 | (Aelred of Rievaulx 1977, 2: 56–60, p. 84; p. 83). |

| 31 | Cited in (Mills 2002, p. 152). |

| 32 | (Ruggiero 1985, p. 141). |

| 33 | (Ogden 2021, p. 204). |

| 34 | (Newman 2013). |

| 35 | (Gaunt 2006). |

| 36 | (Newman 2006, p. 265). |

| 37 | (Newman 2013); (Newman 2006). |

| 38 | (Hamburger 1990, especially pp. 70–71, 80–82). |

| 39 | (Kraye 1997, p. 80). |

| 40 | (Barkan 1991, pp. 70–74). |

| 41 | Abravanel, a Jew born in Lisbon, was known in Italy as Leone Ebreo. |

| 42 | (Kodera 1995). |

| 43 | (Ebreo 1929, pp. 49–50); translated in (Friedeberg-Seeley and Barnes 1937, p. 54). |

| 44 | Ibid., p. 56; pp. 61–62. |

| 45 | Ibid., p. 54; p. 59. |

| 46 | Ibid., pp. 362–63. |

| 47 | Ibid., p. 365. |

| 48 | Edmund Spenser, sonnet 68. See (Oram 2010, pp. 87–103). See also (Lefranc 1914); (Perry 1980). |

| 49 | (Stowell 2015). |

| 50 | (Rolle 1972, p. 145). |

| 51 | Cited in (Ferber 2004, pp. 135–43). |

| 52 | (de Voragine 2012, p. 218, see also p. 55 and p. 84); (Walker Bynum 1991, pp. 290–94). |

| 53 | Speculum, cited in (Walker Bynum 1995a, p. 336). |

| 54 | Ibid. |

| 55 | Cited in (Inglis 2008, p. 23). On Christ’s beauty see also (Morello and Wolf 2000); (Verdon 2010). |

| 56 | (Rolle 1972, pp. 78–79). Rolle here incorporated language from Canticles 5:8. |

| 57 | For a survey of some of these texts see (Walker Bynum 1995b, pp. 25–26). |

| 58 | (Rocke 1996); (Ruggiero 1985). |

| 59 | (Trexler 1980); (Ventrone 2003). |

| 60 | See for example (Ficino 1987); (Ficino 1985, p. 165). |

| 61 | (Bellincioni 1876, CXVI, p. 164). |

| 62 | (Gilio 1960, pp. 72–73). |

| 63 | (Brown 1986, p. 122). |

| 64 | See for example (Alberti 1972, pp. 60–61). Mary Carruthers has analysed the complexity of medieval and early modern aesthetic and devotional categories such as beauty (Carruthers 2013). The representation of ugliness or suffering was also understood to have a powerful effect on a viewer, stimulating sensations that could aid devotion such as horror, shock, compassion or compunction. This too could be experienced in a positive, even pleasurable, manner. |

| 65 | (Paleotti 2002, 2, 23, p. 233). |

| 66 | Ibid., 1, 23, p. 74. |

| 67 | (Freedberg 1989, p. 17). |

| 68 | The letter is transcribed in (Gould 1976, p. 186). |

| 69 | (Fabbro 1977, p. 24). See also (Joannides 2016). There is debate among scholars as to whether Federico was acting as intermediary for Colonna or not. |

| 70 | (Colonna 2005, pp. 76–77). See also (Ben-Aryeh Debby 2003, pp. 29–33). |

| 71 | (Colonna 1982, p. 162). |

| 72 | (Borromeo 2010, p. 155). |

| 73 | (Campbell 2004). |

| 74 | On the influence of Neoplatonism on Colonna’s beliefs see (Brundin 2008). |

| 75 | (Joannides 2016). |

| 76 | (Mormando 1999, pp. 107–8); (Haskins 1995, p. 260). |

| 77 | (Delenda 1989, p. 196). |

| 78 | Scholars who have taken up this challenge include (Aikema 1994); (Hart and Stevenson 1995); (Burke 2006); (Stefaniak 1992); (Mills 2014). |

| 79 | This imagery, and its development, meanings and significance, are examined at length in (Corry, forthcoming). |

| 80 | (Corry 2013). |

| 81 | See (Azzolini 2004); (Pederson 2008); (Pederson 2021); (Corry, forthcoming). |

| 82 | (da Correggio 1969, ‘Fabula Psiches et Cupidinis’, canto 171, p. 93). The poem is also discussed in (Campbell 2005, pp. 646–47). |

| 83 | (Poliziano 1992, p. 11). Migliorotti was delayed on his journey to Mantua, where the play was put on in 1490, and did not arrive in time to take the part, see (Pirrotta 1982, p. 289). |

| 84 | (Corry 2022). |

| 85 | Paris MS A 109v, (Farago et al. 2018, ch. 210), (Richter 1939, n. 592). |

| 86 | Urb. 130v-1r, (McMahon 1956, 442), (Kemp 1989, p. 195). Urb. 11r-v, (McMahon 1956, 42), (Kemp 1989, p. 24). He also wrote of how in the natural world the appeal of physical beauty could entice victims into a trap, see Paris MS H 22v, (Richter 1939, n. 1252–53). |

| 87 | Urb. 14r, (McMahon 1956, 33), (Kemp 1989, p. 26). |

| 88 | Urb. 13r-v; (McMahon 1956, 33), (Kemp 1989, p. 28). |

| 89 | Urb. 5r, (McMahon 1956, 35), (Kemp 1989, p. 32). |

| 90 | (Farago 1992, p. 231). |

| 91 | (Fregoso 1976, ‘Pergoletta’, cantos 32–34). |

| 92 | (Equicola 1999, p. 438). Discussed in (Campbell 2005, p. 639) in the context of analysis of debates that circulated concerning the role and place of erotic love in late fifteenth-century Italian court culture. On Equicola see (Kolsky 1991). |

| 93 | (Fregoso 1976, 5a, p. 6). |

| 94 | Ibid., ‘Pergoletta’, canto 3. |

| 95 | Ibid., canto 20. |

| 96 | (Kemp 1989, p. 24). |

| 97 | Dolce, L’Aretino (1557), cited in (Cranston 2003, p. 120). |

| 98 | The drawing’s history and scholarly responses to it are outlined in (Turner 2017, pp. 40–49). |

| 99 | I am grateful to James Grantham Turner for supplying me with his digitally ‘cleaned’ image of the drawing. An area of wash over the genitals was an attempt at censorship which has been electronically removed. |

| 100 | Leonardo’s Baptist is often dated to the closing years of his career, although he may have been working on it for some time before his arrival in France, where Antonio de Beatis saw it in 1517. |

| 101 | Cited in (Haskell 1980, p. 100). |

References

- Aelred of Rievaulx. 1977. Spiritual Friendship. Translated by Mary Laker. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Aikema, Bernard. 1994. Titian’s Mary Magdalen in the Palazzo Pitti: An Ambiguous Painting and Its Critics. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 57: 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, Leon Battista. 1972. On Painting and on Sculpture. The Latin Texts of De Pictura and De Statua. Edited and Translated by Cecil Grayson. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1952. Compendium Theologiae. Translated by Cyril Vollert. St. Louis and London: B. Herder Book Co. [Google Scholar]

- Azzolini, Monica. 2004. Anatomy of a Dispute: Leonardo, Pacioli and Scientific Courtly Entertainment in Renaissance Milan. Early Science and Medicine 9: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan, Leonard. 1991. Transuming Passion: Ganymede and the Erotics of Humanism. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bellincioni, Bernardo. 1876. Le rime di Bernardo Bellincioni. Edited by Pietro Fanfani. Bologna: G. Romagnoli. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Aryeh Debby, Nirit. 2003. Vittoria Colonna and Titian’s Pitti ‘Magdalen’. Woman’s Art Journal 24: 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borromeo, Federico. 2010. Sacred Painting/Museum. Edited by Kenneth Rothwell. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, John. 1980. Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, Alan. 2006. The Friend. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Judith C. 1986. Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Peter. 2002. Bodies and Minds: Sexuality and Renunciation in Early Christianity. In Sexualities in History: A Reader. Edited by Kim M. Phillips and Barry Reay. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 479–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brundin, Abigail. 2008. Vittoria Colonna and the Spiritual Poetics of the Italian Reformation. Aldershot: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Jill. 2006. Sex and Spirituality in 1500s Rome: Sebastiano Del Piombo’s Martyrdom of Saint Agatha. The Art Bulletin 88: 482–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Stephen. 2004. The Cabinet of Eros: Renaissance Mythological Painting and the Studiolo of Isabella D’Este. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Stephen. 2005. Eros in the Flesh: Petrarchan Desire, the Embodied Eros, and Male Beauty in Italian Art 1500–1540. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 35: 629–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, Mary. 2006. Sweetness. Speculum 81: 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, Mary. 2013. The Experience of Beauty in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna, Vittoria. 1982. Rime. Edited by Alan Bullock. Rome: G. Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna, Vittoria. 2005. Sonnets for Michelangelo. Edited and Translated by Abigail Brundin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corry, Maya. 2013. The alluring beauty of a Leonardesque ideal: Masculinity and spirituality in Renaissance Milan. Gender & History 25: 565–89. [Google Scholar]

- Corry, Maya. 2022. The Homoerotics of Power: Art and Desire in Leonardo’s Milan. In The Male Body and Social Masculinity in Premodern Europe. Edited by Jacqueline Murray. Toronto: Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies, pp. 193–227. [Google Scholar]

- Corry, Maya. forthcoming. Beautiful Bodies: Spirituality, Sexuality and Gender in Leonardo’s Milan. Oxford: Oxford Brookes.

- Cranston, Jodi. 2003. Desire and Gravitas in Bindo’s Portraits. In Raphael, Cellini and a Renaissance Banker: The Patronage of Bindo Altoviti. Edited by Alan Chong, Donatella Pegazzano and Dimitrios Zikos. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, pp. 115–31. [Google Scholar]

- da Correggio, Niccolò. 1969. Opere. Cefalo, Psiche, Silva, Rime. Edited by Antonia Tissoni Benvenuti. Bari: G. Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Delenda, Odile. 1989. Sainte Marie Madeleine et l’application du decret tridentin. In Marie Madeleine dans la Mystique, les Arts et les Lettres. Edited by Eve Duperray. Paris: Editions Beauchesne. [Google Scholar]

- de Voragine, Jacobus. 2012. The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton: Woodstock. [Google Scholar]

- Ebreo, Leone. 1929. Dialoghi D’amore. Edited by Santino Caramella. Bari: Gius.Laterza & Figli Spa. [Google Scholar]

- Equicola, Mario. 1999. La Redazione Manoscritta del ‘Libro de Natura D’amore’. Edited by Laura Ricci. Rome: Bulzoni. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbro, Celso. 1977. Tiziano, le Lettere. Belluno: Magnifica Comunità di Cadore Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Farago, Claire. 1992. Leonardo da Vinci’s Paragone: A Critical Interpretation with a New Edition of the Text in the Codex Urbinas. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Farago, Claire, Janis Bell, and Carlo Vecce. 2018. The Fabrication of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Trattato della Pittura’. 2 vols. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ferber, Sarah. 2004. Demonic Possession and Exorcism in Early Modern France. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ficino, Marsilio. 1985. Commentary on Plato’s Symposium on Love. Translated by Sears Jayne. Dallas: Spring Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ficino, Marsilio. 1987. Libro Dell’amore. Edited by Sandra Niccoli. Florence: L.S. Olschki. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, David. 1989. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fregoso, Antonio. 1976. Opere. Edited by Girgio Dilemmi. Bologna: Commissione per i testi di lingua. [Google Scholar]

- Friedeberg-Seeley, F., and Jean H. Barnes. 1937. The Philosophy of Love (Dialoghi D’amore). London: Soncino P. [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt, Simon. 2006. Love and Death in Medieval French and Occitan Courtly Literature: Martyrs to Love. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilio, Andrea. 1960. Degli Errori e degli Abusi de’ Pittori (1564). In Trattati D’arte del Cinquecento fra Manierismo e Contrariforma. Edited by Paola Barrochi. 3 vols, 1960–1962. Bari: Giuseppe Laterza & Figli, vol. 2, pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Cecil. 1976. The Paintings of Correggio. London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 1990. The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland Circa 1300. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hankins, James. 1990. Plato in the Italian Renaissance. 2 vols. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Clive, and Kay Stevenson. 1995. Heaven and the Flesh: Imagery of Desire from the Renaissance to the Rococo. Cambirdge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haskell, Francis. 1980. Patrons and Painters: Art and Society in Baroque Italy. New Haven and London: Harper & Row, Publishers, p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Haskins, Susan. 1995. Mary Magdalen, Myth and Metaphor. New York: Riverhead Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hyatte, Reginald. 1994. The Arts of Friendship: The Idealization of Friendship in Medieval and Early Renaissance Literature. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Erik. 2008. Faces of Power & Piety. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Joannides, Paul. 2016. An Attempt to Situate Titian’s Paintings of the Penitent Magdalen in Some Kind of Order. Artibus et Historiae 73: 157–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Martin, ed. 1989. Leonardo on Painting: An Anthology of Writings by Leonardo da Vinci. Margaret Walker, trans. New Heaven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kodera, Sergius. 1995. Filone und Sofia in Leone Ebreo’s Dialoghi D’amore: Platonische Liebesphilosophie der Renaissance und Judentum. Frankfurt: Peter Lang Gmbh. [Google Scholar]

- Kolsky, Stephen. 1991. Mario Equicola: The Real Courtier. Geneva: Librairie Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Kraye, Jill. 1997. Cambridge Translations of Renaissance Philosophical Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc, Abel. 1914. Le Platonisme et la Literature en France à L’époque de la Renaissance. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, Maria H. 2013. ‘La custodia degli occhi’: Disciplining Desire in Post-Tridentine Italian Art. In The Sensuous in the Counter-Reformation Church. Edited by Marcia Hall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Maggi, Armando. 2005. On Kissing and Sighing: Renaissance Homoerotic Love from Ficino’s De amore and Sopra Lo Amore to Cesare Trevisani’s L’impresa (1569). Journal of Homosexuality 49: 315–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, Philip, ed. and trans. 1956. Treatise on Painting (Codex Urbinas Latinus 1270). 2 vols. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Robert. 2002. Ecce Homo. In Gender and Holiness: Men, Women and Saints in Late Medieval Europe. Edited by Samantha Riches and Sarah Salih. London: Routledge, pp. 152–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Robert. 2014. Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, Giovanni, and Gerhard Wolf, eds. 2000. Il Volto di Cristo. Milan: Mondadori Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Mormando, Franco, ed. 1999. Teaching the Faithful to Fly: Mary Magdalene and Peter in Baroque Italy. In Saints and Sinners: Caravaggio and the Baroque Image. Chicago: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, pp. 107–8. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barbara. 2006. Love’s arrows: Christ as Cupid in late medieval art and devotion. In The Mind’s Eye. Art and Theological Argument in the Middle Ages. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Anne-Marie Bouché. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 263–86. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barbara. 2013. Medieval Crossover: Reading the Secular against the Sacred. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, Amy V. 2021. St Eufrosine’s Invitation to Gender Transgression. In Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography. Edited by Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 201–22. [Google Scholar]

- Oram, William A. 2010. Spenser’s Crowd of Cupids and the Language of Pleasure. In Rhetorics of Bodily Disease and Health in Medieval and Early Modern England. Edited by Jennifer Vaught. Farnham: Routledge, pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ottonelli, Gian Domenico, and Pietro da Cortona. 1652. Trattato della pittura e scultura, uso et abuso loro. Florence: Nella Stamperia di Gio. [Google Scholar]

- Paleotti, Gabriele. 2002. Discorso Intorno alle Immagini sacre e Profane (1582). Vatican City: LEV Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Palmarocchi, Roberto, ed. 1933. Prediche Italiane ai Fiorentini. Perugia: La Nuova Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Pederson, Jill. 2008. Henrico Boscano’s Isola Beata: New evidence for the Academia Leonardi Vinci in Renaissance Milan. Renaissance Studies 22: 450–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederson, Jill. 2021. Leonardo, Bramante, and the Academia: Art and Friendship in Fifteenth-Century Milan. Brepols: Brepols Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, Theodore Anthony. 1980. Erotic Spirituality: The Integrative Tradition from Leone Ebreo to John Donne. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pirrotta, Nino. 1982. Music and Theatre from Poliziano to Monteverdi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poliziano, Angelo. 1992. Stanze, Orfeo, Rime. Edited by David Puccini. Milan: Garzanti. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Jean Paul, ed. and trans. 1939. The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci. 2 vols. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Rocke, Michael. 1996. Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rolle, Richard. 1972. The Fire of Love. Translated by Clifton Wolters. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, Guido. 1985. The Boundaries of Eros: Sex Crime and Sexuality in Renaissance Venice. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Screech, Michael. 1980. Ecstasy and the Praise of Folly. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak, Regina. 1992. Replicating Mysteries of the Passion: Rosso’s Dead Christ with Angels. Renaissance Quarterly 45: 677–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, Steven. 2015. The Spiritual Language of Art: Medieval Christian Themes in Writings on Art of the Italian Renaissance. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Trexler, Richard C. 1980. Public Life in Renaissance Florence. New York and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, James Grantham. 2017. Eros Visible: Art, Sexuality and Antiquity in Renaissance Italy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1966–1987. Le Vite de’ più Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori e Architettori. Edited by Paola Barocchi and Rosanna Bettarini. Florence: Newton Compton Editori. [Google Scholar]

- Ventrone, Paola. 2003. La sacra rappresentazione fiorentina, ovvero la predicazione in forma di teatro. In Letteratura in Forma di Sermone: I Rapporti tra Predicazione e Letteratura nei Secoli XIII–XVI. Edited by Ginetta Auzzas, Gionvanni Baffetti and Carlo Delcorno. Firenze: Olschki, pp. 255–80. [Google Scholar]

- Verdon, Timothy, ed. 2010. Gesu: Il Corpo, il Volto Nell’arte. Milan: Silvana. [Google Scholar]

- Walker Bynum, Caroline. 1991. Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Walker Bynum, Caroline. 1995a. The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200–1336. New York and Chichester: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walker Bynum, Caroline. 1995b. Why All the Fuss about the Body? A Medievalist’s Perspective. Critical Inquiry 22: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterworth, James, ed. 1848. The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Oecumenical Council of Trent. London: Dolman. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).