Abstract

This paper contextualizes Okudzhava’s song “And We to the Doorman” (AWD), initially marginal in the Soviet poetic mainstream. It explores its shifts in tone, irregular rhythms, colloquial language, and semi-criminal undertones. AWD’s structure, with uneven stanzas and no clear refrain, reveals underlying symmetry and recurring themes. The meter is predominantly iambic but varies. Unconventional verse endings and various rhyme schemes, including distant chains, characterize its prosody. The narrative touches on social cohesion and class conflict. The style reflects a challenging attitude toward privilege, employing rhetorical devices and indirect threats. The melody aligns with thematic elements, featuring repetitive patterns and a spoken quality. Semantically, AWD presents an ambiguous message on class struggle and moral issues. In sum, this analysis uncovers Okudzhava’s song’s formal complexities, thematic nuances, and stylistic innovations.

1. Introductory Remarks

Bulat Okudzhava (1924–1997), an eminent Soviet troubadour and literary luminary of Georgian and Armenian lineage, emerged as a preeminent figure in the cultural context of his era. Hailing from Moscow, his ascent to fame and eminence burgeoned within the confines of the Soviet milieu, where he assumed a pivotal role within the semi-underground bardic movement. This grassroots cultural renaissance, marked by the melodic musings of amateur minstrels and poetic savants, unfolded in clandestine venues, ranging from dimly lit cafés to intimate soirees, where uncensored verses found resonance. Okudzhava’s indelible mark on the epoch stemmed from his amalgamation of poetic finesse and melodic virtuosity, transcending the ossified strictures of genre and political orthodoxy.

His oeuvre showed a remarkable capacity to encapsulate the Zeitgeist, offering a panorama of the Soviet mode of life, its triumphs and tribulations. His literary and musical creations served as a subtle form of cultural subversion, channeling the collective voice of the populace, articulating their aspirations, reveries, and vexations against the backdrop of an autocratic regime.1 Central to Okudzhava’s artistic oeuvre was his seamless fusion of verse and melody, crafting compositions that were both intellectually enriching and emotionally evocative. His lyrical musings, imbued with introspective profundity, delved into the labyrinthine corridors of human sentiment, exploring themes of love, bereavement, wistfulness, and existential quandary. The legacy of Bulat Okudzhava in the annals of global music is that of a bard of/for the masses, whose resonant melodies endure thanks to the power of artistic expression.

Okudzhava’s lyrical oeuvre stands out as an amalgam of folkloric, balladic, and bardic elements with a distinctive Soviet-era ethos. The melodic contours of his compositions exhibit a propensity towards simplicity, unembellished chord progressions, and iterative motifs. This ostensible simplicity not only enhances their aesthetic allure but also fosters heightened audience engagement, underscoring their sociocultural resonance. His lyrics are replete with vivid imagery, exquisite poetry of grammar and flights of metaphorical imagination, and occasionally trenchant social critiques. They epitomize the poet’s astute observational acumen and literary finesse, transcending the confines of conventional verse.

Central to Okudzhava’s creative praxis is a palpable sense of intimacy and authenticity, conveyed by his soulful renditions and the sonority of guitar accompaniment. Infusing his performances with a conversational cadence, he ensnares listeners with an aura of sincerity and emotional profundity, forging a connection with the audience, while sociopolitical commentary is veiled beneath the veneer of poetic subtlety. Many of his compositions serve as implicit indictments of the prevailing governmental dictates, while at the same time articulating the collective aspirations and thus imbuing his music with an undercurrent of latently insurgent fervor. The scholarly exegesis of Okudzhava’s corpus calls for an array of interdisciplinary approaches. Literary critics have identified the manifold literary techniques, thematic preoccupations, and sociohistorical underpinnings of his compositions.2 In turn, musicologists have focused on the intricacies of Okudzhava’s melodic contours, harmonic configurations, and rhythmic modalities. Moreover, some scholarly inquiries have extended to the performative dimensions of the bard’s vocal tonality, guitar proficiency, and stage persona, offering insights into his artistic persona and communicative strategies. Modern scholarly studies of Bulat Okudzhava are a showcase of interdisciplinary exploration in the humanities, where the special fields of literature, musicology, performance studies, and cultural historiography converge to do justice to the enigmatic treasures of his oeuvre.

The main analysis of my essay will not touch upon musical or musicological issues specifically; rather, the aim of my paper is to contextualize Okudzhava’s specific song, initially perceived as marginal and provocative within the Soviet poetic mainstream. It focuses specifically on structural reading of “And We to the Doorman” (AWD), highlighting its paradoxical shifts in tone, irregularities in rhythm and rhyme, colloquial vocabulary, and semi-criminal undertones. From a structural point of view, AWD exhibits a complex stanzaic arrangement with uneven lengths and a lack of a clear couplet–refrain pattern. However, underlying this disorder is a certain order, with symmetrical divisions and recurring motifs. The meter of AWD is predominantly iambic but varies in length and fluctuation. Prosodically, the text features unconventional verse endings and a mix of masculine, feminine, and dactylic clausulae. Rhyming in AWD showcases a duality, with various rhyme schemes and patterns observed throughout the text, including distant chains and internal rhyming. The composition is marked by a deliberate duality, balancing irregularity with correct versification. The narrative of AWD revolves around the protagonist’s arrival at a restaurant with friends, exploring themes of social cohesion, class inequality, and conflict with the establishment. The style of the text reflects the main character’s challenging attitude towards privilege, conveyed through authoritative tone, rhetorical devices, and even (in)direct discursive threats. The melody of AWD is characterized by repetitive patterns and a monotonous, spoken quality. The text highlights the recurrence of certain rhythmic–melodic motifs and their alignment with thematic elements. Finally, the semantics of AWD presents an ambiguous ideological message, with themes of class struggle and moral ambiguity. The protagonists’ challenge to the establishment is juxtaposed with their own aspirations for privilege, complicating the moral stance of the song. Overall, the analysis provides a comprehensive examination of Okudzhava’s song, uncovering its formal complexities, thematic nuances, and stylistic innovations.

2. The Problem

“And We to the Doorman…” (hereafter referred to as AWD) is an early, 1957–1958, piece by the renowned Russian “bard” Bulat Okudzhava (1924–1997)3—early and, in light of his further career, quite atypical.4 I first heard it—as a tape recording—around 1959. The impression was twofold: the song sounded interesting and catchy, yet there was something slightly off about it. This ambivalence, despite my general admiration for Okudzhava’s oeuvre5, resurfaced when I revisited the song recently: it was as if my initial reaction was reconfirmed. However, the more I listened to the song and reflected upon it, the more I was fascinated by its poetic originality, and this called for an in-depth analysis.

To put my perception in historical context, I will quote some statements about AWD made by the author himself and some of his younger contemporaries. I will then focus on the various levels of the song’s structure to try and do justice to its merits, before resuming the discussion of the song’s overall thematic message.

- Bulat Okudzhava (talking to an interviewer):

Q. You had an early song, ‘Come on, doormen, open the doors…’. From whose perspective is it preformed?

A. From that of an ordinary impoverished young man of my generation who went out to a restaurant. And he doesn’t like the way the snobbish bums and whores there are looking at him and his girlfriend.

I recall a censuring meeting of official figures, chaired by the then cultural Party-boss, Leonid Ilyichev. And from the lectern he said: “Okudzhava has a song glorifying the ‘golden youth’…” He paused a bit and I said loudly from my seat: “I don’t have such a song.”—He [shot back]: “What about the doorman at the restaurant…?”—I: “This song celebrates not the golden youth, but ordinary youth.”—He, confusedly: “And I was told…” <…>

Q. But you did happen <…> to tell all kinds of hooligans that they shouldn’t be looking at your girlfriend in that peculiar way and that you would stand up for her accordingly?

A. I did.

Q. Including with your fists?

A. Why not?

Q. And what about being an intellectual <…> and your favorite idea of abhorring keep the bolodviolence?

A. To defend your woman is strength, not violence. An intellectual should doubt himself, practice self-irony, passionately love knowledge <…> and yet be able to punch a scoundrel in the face (Bykov 1997).

- Stanislav Rassadin (literary critic):

Those [official critics] who trashed Okudzhava <…> were not all that wrong <…> The most <…> ingenuous of his songs received a staggering but, if you think about it, legitimate interpretation. They were accused of ‘vilification’: for example, the student song “And we to the doorman…” was declared almost a hymn to ‘golden youth’ (which <…> if it did exist, could be found not among the characters of our bard’s songs, but rather in the families of his big-wig apparatchik attackers)… (Rassadin 1990, pp. 20–21).

- Dmitry Bykov (poet, journalist, literary critic):

- -

- Since almost the entire intelligentsia <…> was persecuted <…> it developed quasi-criminal habits: an a priori distrust of <…> ‘the bosses’ <… and > contempt for <…> those who sold out for jail rations <…> Most of this urban intelligentsia <… > was brought up in the courtyards, where rather suspicious moral codes prevailed—and the cult of the courtyard became the basis of the Sixties mythology <…> That’s why the bosses <…> disliked Okudzhava’s songs <…> branding them semi-criminal <…>. That applied especially to songs like “And we to the doorman…,” where <…> nonconformism and self-esteem are shown against the background of a restaurant scandal <…> The Party bosses <…> realized that under the cover of the semi-criminal courtyard folklore there was developing a different, alternative code <…> a potential for resistance, albeit as yet innocent and not politicized (Bykov 2009, pp. 133–34). Okudzhava <…> systematically <…> downplayed his own authorial image <…> That is why quotations from his lyrics became popular memes, a part of everyday Russian speech: because in his case the distance between the author and the listener <…> was minimal <…> as he addressed issues that used to be unmentionable <…> It is hard to believe now that once <…> it took courage to stop ignoring the realities of everyday life (Bykov 2009, p. 310).

Overall. Okudzhava’s speaker <…> can admit that his beloved’s brooch is a rented one. He speaks on behalf of people for whom a private room in a restaurant, booked once a month, after the paycheck, was the height of luxury; at the same time, unlike the hero-narrator of the “gangsta” song <…> he would not let himself to be rude. And should he swear, the curse word will sound all the more striking <…> because it stands out sharply against the background of his nice discourse <…>. “Bitch” and “scum” sound so strong here precisely because the protagonist is repressed and shy, and it is a big deal for him to walk “swaggering into a private room” (Bykov 2009, p. 303).

- Ilya Ioslovich (poet, mathematician):

- -

- “We to the doorman” was in those days a declaration of independence (e-mail communication to the author, 18 November 2021).

- Andrei Aryev (literary critic, editor):

- -

- Apparently, there are, so to speak, ‘aesthetic phantoms’ that keep haunting you throughout your life <…> Still, the song, for my current taste, is somewhat too fancy. But one of the ineradicable <…> human qualities is our ingratitude. In our student years, we used to sing “And we to the doorman…” almost with rapture, in any case ‘with a feeling of deep satisfaction’. We were—without noticing it, like Okudzhava’s protagonist himself,—sort of snobbish, eager to join the semi-criminal underworld and the ‘golden youth’ cohorts (e-mail communication to the author, 21 November 2021).

- Alexander Zhurbin (composer):

- -

- This song <…> stood apart. It was unusual thematically (a restaurant for a boy like me was a forbidden place, a place of debauchery), and the word “scum” was practically a profanity. I sang many Bulat Okudzhava songs in front of my parents, but I wouldn’t dare to sing this one, it was considered ‘obscene’ <…> Also, I always had the feeling that he somehow <…> failed to bring it to perfection, but simply improvised it somewhere at a friends’ place, and so it stayed that way… But it turned out to be a beautiful—and mysterious—one (e-mail communication to the author, 29 October 2021).

- Vladimir Novikov (literary critic):

- -

- Okudzhava’s songs were initially perceived as a marginal and provocative phenomenon <…> in relation to the Soviet poetic mainstream <…>. For example, the song ‘And we to the doorman…!’ <…> is marked by paradoxical shifts on all levels: a conversational intonation, accented verse, irregular rhyming, down-to-earth vocabulary, semi-criminal presence of the ‘lyrical hero’ <…>. On the level of rhythm, Okudzhava achieves a fruitful compromise between colloquiality and melodiousness. On the lexical-semantic level, he achieves a musical confluence of contrasting elements (Novsikov: 121).6

3. The Text

Here are the lyrics of the song,7 already accompanied with columns of its major formal characteristics that I will be discussing in what follows:

| Strophes | Lines | Text | Clausulae | Rhymes | Feet |

| < Чacть 1-я > | |||||

| I | 1 | A мы швeйцapy: «Oтвopитe двEpи! | F | X [E] | 5 |

| 2 | У нac кoмпaния вeceлaя, бoльшAя, | F | X [A] | 6 | |

| 3 | пpигoтoвьтe нaм oтдeльный кaбинEт!» | M | A [E] | 6 | |

| II | 4 | A Любa cмoтpит: чтo зa кpacoтA! | M | B [A] | 5 |

| 5 | A я гляжy: нa нeй тaкaя бpOшкa! | F | C [O] | 5 | |

| 6 | Xoть нaпpoкaт oнa взятA, | M | B [A] | 4 | |

| 7 | пycкaй пoтeшитcя нeмнOжкo. | F | C [O] | 4 | |

| 8 | A Любe вcлEд глядит oдин бpюнEт. | M (+INT) | A [E] | 5 | |

| III | 9 | A нaм плeвaть, и мы вpaзвAлoчкy, | D | D [A] | 4 |

| 10 | пoкинyв paздeвAлoчкy, | D | D [A] | 3 | |

| 11 | идeм ceбe в oтдeльный кaбинEт. | M | A [E] | 5 | |

| IV | 12 | Ha нac глядят бeздeльники и шлЮxи. | F | X [U] | 5 |

| 13 | Пycть нaши жEнщины нe в жEмчyгe, | D (+INT) | X [E] | 4 | |

| 14 | пocлyшaйтe, пopA yжe, | D | X [A] | 3 | |

| 15 | кoнчaйтe вaши «ax» нa cтo минУт. | M | E [U] | 5 | |

| V | 16 | Здecь тpяпкaми пoпaxивaeт тAк… | M | F [A] (=B) | 5 |

| 17 | Здecь cмoтpят дpyг нa дpyгa cквoзь чepвOнцы. | F | G [O] (=C) | 5 | |

| 18 | Я нe любитeль вcякиx дpAк, | M | F [A] (=B) | 4 | |

| 19 | нo мнe cкaзaть eмy пpидËтcя, | F | G [O] (=C) | 4 | |

| 20 | чтo я eмy пoпopчy вecь yЮт, | M | E [U] | 5 | |

| 21 | чтo нaши дEвyшки зa дEнeжки, | D (+INT) | X [E] | 4 | |

| 22 | пpeдcтaвь ceбe, пacкyдинa бpюнEт, | M | A [E] | 5 | |

| 23 | oни ceбя нe пpoдaЮт. | M | E [U] | 4 | |

- Latin transliteration:

| Strophes | Lines | Text | Clausulae | Rhymes | Feet |

| < First part > | |||||

| I | 1 | A my shveitsaru: “Otvorite dvEri! | F | X [E] | 5 |

| 2 | U nas kompaniia veselaia bol’shAia, | F | X [A] | 6 | |

| 3 | prigotov’te nam otdel’nyi kabinEt! | M | A [E] | 6 | |

| II | 4 | A Liuba smotrit: chto za krasotA! | M | B [A] | 5 |

| 5 | A ia gliazhu: na nei takaia brOshka! | F | C [O] | 5 | |

| 6 | Khot’ naprokat ona vziatA, | M | B [A] | 4 | |

| 7 | puskai poteshitsia nemnOzhko. | F | C [O] | 4 | |

| 8 | A Liube vslEd gliadit odin briunEt. | M (+INT) | A [E] | 5 | |

| III | 9 | A nam plevat’, i my vrazvAlochku, | D | D [A] | 4 |

| 10 | pokinuv razdevAlochku, | D | D [A] | 3 | |

| 11 | idem sebe v otdel’nyi kabinEt. | M | A [E] | 5 | |

| < Second part > | |||||

| IV | 12 | Na nas gliadiat bezdel’niki i shliUkhi. | F | X [U] | 5 |

| 13 | Pust’ nashi zhEnshchiny ne v zhEmchuge, | D (+INT) | X [E] | 4 | |

| 14 | poslushaite, porA uzhe, | D | X [A] | 3 | |

| 15 | konchaite vashi “akh” na sto minUt. | M | E [U] | 5 | |

| V | 16 | Zdes’ triapkami popakhivaet tAk… | M | F [A] (=B) | 5 |

| 17 | Zdes’ smotriat drug na druga skvoz’ chervOntsy. | F | G [O] (=C) | 5 | |

| 18 | Ia ne liubitel’ vsiakikh drAk, | M | F [A] (=B) | 4 | |

| 19 | no mne skazat’;’ emu pridiOtsia, | F | G [O] (=C) | 4 | |

| 20 | chto ia emu poporchu ves’ uiUt, | M | E [U] | 5 | |

| 21 | chto nashi dEvushki za dEnezhki, | D (+INT) | X [E] | 4 | |

| 22 | predstav’ sebe, paskudina briunEt, | M | A [E] | 5 | |

| 23 | oni sebia ne prodaiUt. | M | E [U] | 4 | |

- Literal interlinear translation:

| <Part 1> | ||

| I | 1 | And we [say] to the doorman: “Open the doors! |

| 2 | We are a cheerful big party, | |

| 3 | have a private event room ready for us! | |

| II | 4 | And Liuba looks: what a beauty [is all this]! |

| 5 | And I look: she has such a brooch on! | |

| 6 | Although it’s rented, | |

| 7 | let her have a little fun. | |

| 8 | And after Liuba a dark-haired dude is staring. | |

| III | 9 | And/But we don’t care—and in a swagger, |

| 10 | having left the dear old locker-room, | |

| 11 | are heading for [our] private event room. | |

| <Part 2> | ||

| IV | 12 | Parasites and sluts are staring at us. |

| 13 | OK, our women aren’t wearing pearls, | |

| 14 | [hey] listen up, it’s high time you figured [us] out, | |

| 15 | enough of your hundred minutes’ long ‘ahs’! | |

| V | 16 | Here it smells of fancy rags so much… |

| 17 | Here, they eye each other through ten-ruble bills [greenbacks]. | |

| 18 | I’m not a fan of all kinds of brawls, | |

| 19 | but I’ll have to tell him | |

| 20 | that I’ll ruin all his comfort, | |

| 21 | that our girls, for money, | |

| 22 | imagine that, you bastard, | |

| 23 | they don’t sell themselves. | |

4. Stanzaic Structure

A glance at the printed text of AWD immediately catches the quantitative unevenness of the stanzas’ length: 3-5-3-4-8, totaling a remarkably uneven (prime!) number: 23 lines. And the ear registers right away the absence of a clear-cut couplet–refrain pattern, which distinguishes this Okudzhava song from most of the rest.

But through this disorder a certain order does show: the final 8 lines are a sum of 4 + 4 (i.e., two more or less regular quatrains), while the initial 3 + 5 lines also add up to 8, so that, on the whole we get an 8-3-4-8 sequence.

Moreover, the last line of the 5-line stanza II (8 A Liube vsled gliadit odin briunet, “And after Liuba a dark-haired dude is staring”) can be grouped with stanza III,8 which would then turn into a regular quatrain, so that the overall text would form a 3-4-4-4-8 sequence.

To be sure, the characteristic symmetry of the two three-liners (lines 1–3 and 9–11) would be lost, or at least blurred, since stanza I does contains three lines indeed, while stanza III can only wink at it with its duality as an either three- or four-liner. In fact, such “flickering” permeates the entire structure of AWD.

5. Meter

The AWD is mostly iambic, but the lines vary in length: 5-6-6, 5-5-4-4-5, 4-3-5, 5-4-3-5, 5-5-4-4-5-4-5-4. There is, though, a deviation from the iambic meter in I, 3 (prigotoov’te nam otdel’nyi kabinet, “have a private event room ready for us!”): the first syllable of the first foot is truncated (the correct iamb would be: Tak prigotoov’te nam otdel’nyi kabinet).9

No particular order is observed in the arrangement of longer and shorter lines; each stanza manages that in its own way. Thus, it is not a regular multi-footed iamb, but a free one, like that used in fables and verse comedies, the pointedly “conversational” genres, conveying the “live” speech of characters/storytellers.

One aspect of prosody is the organization of verse endings, or clausulae, and in this respect AWD is also rather unconventional. To the irregularly alternating masculine (M) and feminine (F) endings, dactylic (D) clausulae are added: FFM MFMFM DDM FDDM MFMFMDMM.10 Notably, the dactylic (and thereby longest) endings cap three-foot (shortest) and four-foot (rather short) lines, to an extent moderating in this way the variation in line lengths.

Thus, at this level as well, the overall picture is one of certain looseness—of, as it were, partial, casual isorder.

6. Rhyming

Similar duality is evident here, too. The rhyme scheme looks as follows: XXA BCBCA DDA XXXE FGFG EXAE. That is, out of the 23 lines:

- 6 (more than a quarter!) remain blank (X);

- 8 feature alternate rhymes: lines 4/6 (rhyme A), 5/7 (B), 16/18 (F), 17/19 (G);

- 4 feature enclosed ones: 8/11(A), 20/23 (E);

- 2 form couplets: 9/10 (D)—within a proper, enclosed quatrain (ADDA); but when enclosed rhyming recurs in stanza V, the middle endings (lines 21–22) remain blank;

- There are two cases of distant chains: 3 8-11-22 (rhyme A); 15-20-23 (rhyme E).

The poem begins with two unrhymed lines, and all the blank clausulae remain different throughout the text: 1 dvEri (doors)-2 bolshAia (big)-12 shliUkhi (sluts)-13 zhEmchuge (pearls)-14 poRA (high time)-21 dEnezhki (money).

Most rhymes (B, C, D, F, G), too, appear only once—except for the remarkable exception: rhyme B: кpacoтA (beauty)/взятA (rented) is phonetically similar to F: tAk (so much)/drAk (brawls), as are the neighboring rhymes C: brOchka (brooch)/nemnOzhko (a little fun) and G: chervOntsy (ten-ruble bills)/pridiOtsia (have to [tell him]). And there are two blank endings (13 zhEmchuge and 21 dEnezhki) that echo each other distantly.

Distant chains (linking three to even four endings) comprise some of the key rhymes: the first (A) and the last (E). They are both masculine (in -Et and -Ut), and they complete their stanzas:

- 3 kabinEt (room) closes the first stanza; 8 briunEt (dark-haired dude), the second; 11 kabinEt, the third; and 22 briunEt almost completes the fifth;

- 15 minUt (minutes) closes the fourth stanza, 20 uiUt (comfort) completes the first quatrain of the fifth stanza, and 23 prodaiUt (sell) closes its second quatrain.

- Let us note also:

- The tautological repetition of both members of rhyme A (kabinEt/briunEt) in lines 3, 8, 11, 22;

- The non-final position of the last occurrence of briunEt in line 22;

- The climactic reunion of the two key rhymes A and E in the final lines 22–23.

Worth note are also the three instances of internal rhyming. It first appears in Part 1 of the text: 8 vslEd (after)/briunEt (dark-haired dude), and then twice in Part 2: 13 zhEnzhchiny (women)/zhEmchuge (pearls); 21 dEvochki (girls)/dEnezhki (cash).

The latter two pairs stand out thanks to the semantic, prosodic, and phonetic similarities between them, as well as their similar position: in the blank lines with dactylic endings. They are also similar in their “density,” which correlates them with the only coupled (and also dactylic) interlinear rhyme: 9/10 vrazvAlochky (in a swagger)/razdevAlochku (locker room).

Finally, all three internal rhymes (one masculine and two dactylic) are united by the common stressed E, as if aligning them with the five E-clausulae: 1 dvEri-3 kabinEt-8 briunEt-11 kabinEt-22 briunet.

7. Composition

The overall design of the text is also dual—and, for all its unconventionality, deliberately and pointedly so. The “prosaic” irregularity (of the length of stanzas, lines, and clausulae, as well as of the rhyming/blankness of lines and semi-lines) is combined with a largely correct versification.

From beneath the apparent chaos there emerges an underlying order: a rather symmetrical division of the text into comparable halves: the first 11 lines and the second 12.

In the first half, rhyme A dominates (beginning with 3 kabinEt), initiating—after two blank lines (1, 2)—that part’s rhyme scheme, which ends up being closed on an emphatically tautological note (11 kabineEt).

In Part 2, a similar role is played by rhyme E (starting with 15 minUT): it, too, opens a rhymed sequence and comes after some blank lines (this time three, in lines 12, 13, and 14); omitting just one of those, say, 14 porA uzhe (it’s high time), would make the symmetry complete.

However (and this adds contrast to symmetry), in Part 1, as many as five lines begin with the conjunction A (And/but), which is totally absent from part 2.11

The symmetry of the two parts—numerical (11/12 lines) and structural (2 or, in ascending order, 3 initial blank lines followed by the key rhyme)—is supported by the phonetic similarity of these rhymes: all of them masculine, ending in consonants: - (N)T. The similarity of the consonants sets off the contrast of the rhyming vowels E/U, and this pattern culminates in the final juxtaposition of endings: 22 briunEt/23 prodaiUt. The two parts of the poem also echo each other in the way the stressed vowels in the blank endings of their initial lines prepare the appearance of the key rhymes: 1 dvEri → 3 kabinEt; 12 shliUkhi → 15 minUt.

The symmetry is picked up in the stanzas immediately following the key first rhymes. In both parts, these are more or less regular quatrains with alternate, partly similar, rhyme schemes:

(4–7 krasotA - brOshka - vziatA - nemnOzhko; 16–19 tAk - chervOntsy - drAk - pridiOtsia).

In the subsequent quatrains (concluding the respective parts of the text), the rhymes are both times enclosed: 8–11 briunEt - razvAlochku - razdevaAlochku - kabinEt; 20–23 uiUt - dEnezhki - briunEt - prodaiUt). While in Part 1, all the lines of the second stanza are rhymed, in Part 2, the corresponding stanza carries two blank lines (17, 18) in the middle. But the similarity is enhanced by the presence of dactylic clausulae: in Part 1, there are two such rhymed endings (10 razvAlochku/11 razdevAlochku), in Part 2, just one blank one (21 dEnezhki).

The two parts are also similar in the way the word briunEt is placed at the end of line 22, so that two quatrains from different parts of the poem form a distant rhyme (11 kabinEt/22 briunEt). Moreover, as a result, the penultimate line of the final quatrain tautologically rhymes with the last one of stanza II (8 briunEt/22 briunEt).

Symmetry is combined with a crescendo. Hence the extra, 12th, line in Part 2 and the syntactically complete eight-liner at the end of this part, with lines 18–23 constituting a single compound sentence. This crescendo is not merely quantitative: qualitatively it showcases the “victory,” as it were, of Part 2 over Part 1. On the level of form, the key -Ut rhymes displace those in -Et, while thematically, the shift from the penultimate, only distantly rhymed word briunEt (repeated from the first part of the poem) to the final 23 oni sebia ne prodaiUt (they do not sell themselves) marks the triumph of “our” spiritual element, over “their” materialistic one.

8. Narrative

The story of the protagonist’s arrival, with a bunch of pals (connoting the so-called unofficial “youth” subculture of the early Thaw), including his girlfriend Liuba (whose first name unobtrusively connotes “love”—in Okudzhava’s song and the Russian song tradition in general) to an expensive restaurant and their impending conflict with its morally suspicious crowd of regulars (who connote thriving Soviet establishment) is told by the protagonist in the first person. The narrator is obviously quite subjective and perhaps somewhat unreliable, but the narrative is quite transparent—and, again, bipartite.

In Part 1, the protagonists relish entering the coveted territory of the privileged “beautiful life”, with its symbolic attributes (an obliging doorman, a private room, the beauty of the interior, a brooch), and brag about their newly found confidence in gaining a place under the sun. A muffled foreshadowing of the conflict to come in Part 2 can be discerned in the mention of the antagonist, the “dark-haired dude” who seems to be hitting on Liuba. But the antagonist is allotted only one line out of 11, his claims on Liuba do not go beyond a lustful gaze (to speak in the terms of Matthew, 5, pp. 27–28), and the self-confident protagonists do not feel threatened.

In Part 2, the conflict comes to the fore, but even there it does not result in real action: in the spirit of the typically Okudzhavian duality/modality, the tension remains at the level of intentions and glances.

Glances, in particular loving ones, often unrequited, mutual exchanges of glances, as well as glances that miss their objects, constitute one of Okudzhava’s favorite motifs.12 In AWD, they form a five-item series: 4 And Liuba looks… 5 And I look… 8 And… a dark-haired dude is staring… 12 Parasites and sluts are staring… 17 they eye each other through ten-ruble bills. In this series, the antagonist appears for the first time and in an ambiguous, partly positive light: Liuba admires the restaurant, the protagonist admires her brooch, and the dude admires Liuba.

But in Part 2, for all the virtuality of the glances, the narrative’s temperature rises sharply. To begin with, the antagonists’ admiration for our Liuba is exaggerated (to the degree of 15 a hundred minutes’ long “ahs”), as is the theme of the restaurant crowd’s vulgarity (they are parasites, sluts, owners of pearls and money bills, buyers of love/sex). And the speaker of the poem, its lyrical persona, is now ready to fight back, preferably in a moral way (18 I am not a fan of all kinds of brawls), but, if need be, by going physical (20 I’ll ruin all his comfort).

9. Style

Ambiguity also permeates the verbal fabric of AWD, presented as the direct speech of the protagonist, who is thus not just a talking character, but the actual speaker of the piece, a poet, and a likely exponent of the author’s position. Let us outline the characteristic features of his voice.

First of all, it sounds like a challenge to the unfairly privileged masters of the universe—the regular patrons of the restaurant. This can be heard not only in the democratic (demagogic?) tenor of the protagonist’s speeches, but also in their authoritative tone and phrasing. Let us note:

- (1)

- The boldly “invasive” opening of the text: contrary to a normal order of presentation, the first line begins in medias res, in response to someone’s omitted remark, so that the speaker’s tirade, in fact, the entire poem, bursts into the prestigious restaurant—and, as it were, into Russian poetry—right from the street.13

- (2)

- The way the five initial semi-adversative A-conjunctions14 turn, in the second part of the text, into a bluntly antithetical No (19 but I will have to tell him).

- (3)

- The vigorous rhetorical series of concessive phrases: 6 Although… 7 let… 13 OK… 18–19 I’m not a fan of … but I’ll have to…

- (4)

- The insistence on the imperative mood, at first relatively harmless, “unobtrusive,”15 but increasingly overbearing—patronizing and even aggressive: 1 Open … 3 have… ready… 7 let her have… fun (looking down on “her” = Liuba)… 14 listen up it’s high time … 15 enough of your… 22 imagine that…

- (5)

- The humiliating way of nicknaming the opponents: dude, parasites, sluts, and even you bastard—the most offensive one, addressed to the antagonist (albeit so far only mentally).

- (6)

- The projection of provocative physical posturing into similar verbal games/performances, as in 9 we don’t care—and in a swagger…, 10 the dear old locker-room… The protagonists’ pointedly self-asserting half-sportsmanlike, half-perp walk, is followed by the renaming of the restaurant’s cloakroom (where only outer clothes are checked in) into a sports club’s locker-room (inside which one actually enters and from which, having thoroughly changed clothes, leaves)—justifying the use of the swaggering pokinuv (having left). Moreover, at the next step, this locker-room is described as an intimately diminutive, dear old one, razdevAlochku, rhyming nicely with the similarly diminutive vrazvAlochku.

- (7)

- Attempts at high poetic diction, starting with the bookish-romantic version of “Open…!” (Otvorite, rather than its realistically everyday synonym Otkroite), cf. especially the two tropes:

- -

- 6 Here it smells of fancy threads/rags so much……: phraseologically, of course, the verb popakhivaet (reeks) implies big and dirty, i.e., illegal, money, but at the same time it is as if the clothes themselves stank—in both a subtle metaphor and a crude put-down;

- -

- 17 Here, they eye each other through ten-ruble bills, also a figure of speech (incidentally, developing the motif of “exchanging glances”).

- (8)

- The vulgarly pretentious turns of phrase, typical of the restaurant regulars’ semi-criminal lingo and thus contrasting with flights of poetic diction, such as: 15 enough of your hundred minutes’ long ‘ahs’! (reminiscent of the notorious “Odessa dialect”); and 20 I’ll ruin all his comfort.

- (9)

- The pointedly indirect, would-be polite and even elegant final threat of violence, not really provoked by the antagonist, who, after all, had only looked at the pretty Liuba. The protagonist does not direct his allegedly necessary (19 I’ll have to tell…) harangue to the antagonist, but rather shares his brewing emotions with us, the song’s listeners, in a pretentiously oblique allegorical mode (20 that I’ll ruin all his comfort),

- (10)

- And finally, the rudely blunt, albeit still imaginary attack, with a second-person imperative and a straightforward insult (22 imagine that, you bastard), quite ungrammatically breaking through the elaborately complex hypotaxis (with two subordinate clauses properly introduced by the conjunction chto (that): 20 that I’ll ruin… 21 that our girls…

10. Melody

So far, I have stayed within literary-critical grounds, while it is obvious that much of AWD’s success is due its musical side—something I am not qualified to analyze. I’ll only touch upon one musical effect, noticeable to a layman.

What I have in mind is a characteristic rhythmic–melodic pattern recurring throughout the song. Indeed, one cannot help noticing the series of similarly accented and intoned fragments to which some of the most important words of the lyrics are set: kompAniia—vesElaia—potEshitsia—vrazvAlochku—idiOm sebe—ne v zhEmchuge—poslUshaite—porA uzhe—za dEnezhki—predstAav’ sebe—paskUdina. Rhythmically, all of these are four-syllable segments with a stress on the second syllable: ta-TA-ta-ta (known in versification as peons II). This recurrent pattern is already recognizable in the lyrics, as it quite naturally emerges from their iambic meter, especially the lines with dactylic clausulae (-A-a-a).

Sometimes, though, the boundaries of such four-note musical segments do not coincide with those of the actual words in the verse lines. Remarkably, in such cases the wording is “re-spliced” by the musical arrangement, as syllables are cut off or added on: bol’shAia+pri-—<pri>gotOv’te+nam—<na>-prokAt+ona—vziatA+puskai—plevAt’+i+my—pokInuv+raz-—<raz>devAlochku—<na>shi+zhEnshchiny—<na>shi+dEvushki—briunEt+oni.

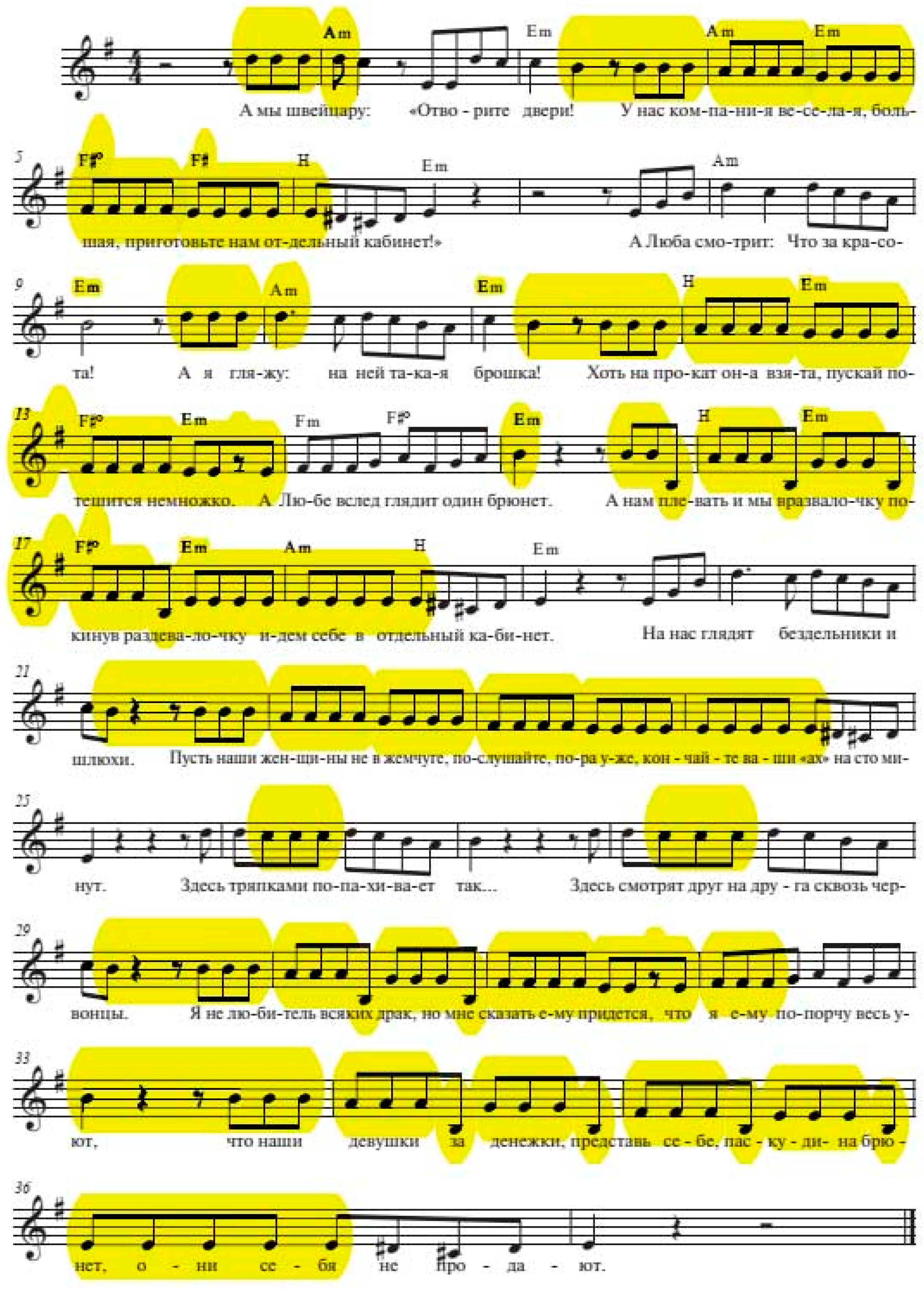

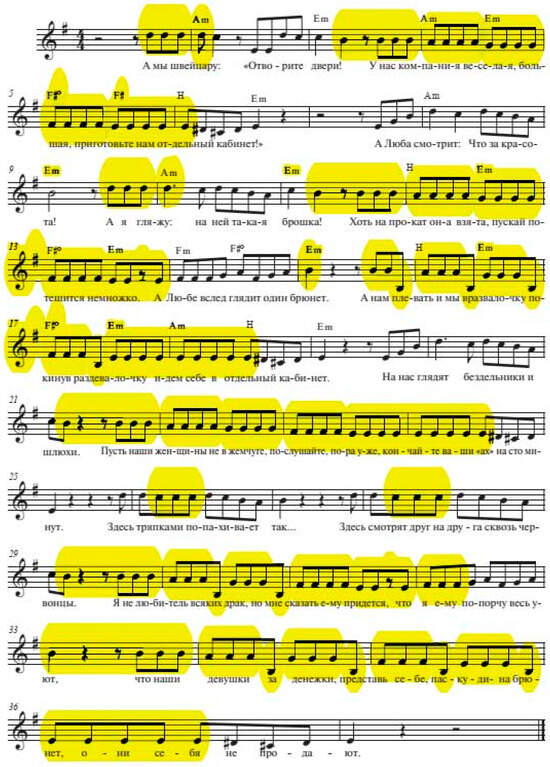

As we turn directly to the song’s musical notation,16 another recurrent pattern stands out: there are many sequences of identical notes (highlighted by me in the notation), see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The musical notation of a fragment.

Indeed, the cases where there are three or more identical notes in a row add up almost exactly to two thirds of the total 225 notes (=syllables of the text). These 151 static, repetitive, “musically uninteresting,” sequences outweigh heavily the 74 “dynamic” ones, responsible for moving the melody up and down.

Furthermore:

- (1)

- These monotonous sequences (in musical terms, the four A’s, four G’s, etc.) often coincide with the four-syllable segments.

- (2)

- Such foursomes (or quartiles) often follow one another in such a way that every subsequent one is sung one musical tonality lower: after four A’s (6 <napro>kAt ona vziA<ta>) come four G’s (6–7 -<vzia>tA puskai po<teshitsia>), then four F’s (7 <po>tEshitsia ne<mnOzhko>), i.e., there are three single-note sequences in a row, descending musically at a minimal pace (one second of a tone at a time);

- (3)

Thus, the song’s poetical–musical leitmotif would seem to be a bar consisting of four identical notes and beginning with a strong accent: TA-ta-ta-ta (i.e., also a peon, but peon I rather than II). This presumed leitmotif, however, would not reflect the song’s insistence on downward melodic movement, nor do the lyrics feature any TA-ta-ta-ta words/phrases.

The fact is that AWD is consistently off-beat: it starts with three pre-bar notes (which are prosodically non- or low-stressed syllables): 1 A my shvei<tsAaru>… The intros of the subsequent lines are also similarly pre-bar/off-beat: 4 A Liuba <smOtrit>; 9 A nam ple<vAt’>. This pre-bar beat pattern echoes the syntactic, narrative, and intonational “irregularity” of the song’s in medias res beginning.

Remarkably, some of these three-note pre-bar intros are also single-note ones (sometimes also repeating the preceding note); see, for example, the four Bs on the highlighted syllables: 1–2 <dvE>ri! U nas kom<pAniia>. In this way, the pre-bar pattern is effectively interwoven with the recurrence of monophonic intra-bar foursomes: the last three notes of one single-note foursome form a pre-bar introduction to the next. That would justify defining the leitmotif of AWD as peon IV.

In any case, there is the insistent multiplicity of single-note sequences, informing the song with a somewhat monotonous, un-melodious, “spoken” kind of sound.19

Moreover, the four-note intros are also repeated quite intensely:

- -

- First (in lines 2–3), there comes a series of five such intros (from u nas kompAniia to prigotOv’te nam otdEl’nyi);

- -

- Then (in lines 5–6), another five from khot’ naprokAt to nemnOzhko;

- -

- Then (lines 9–11), a six-pattern-long series: from A nam plevAt’ to idiOm sebe v otdEl’nyi kabinEt, where the last two foursomes are on the same musical note (E);

- -

- Then (lines 13–15) comes another sixfold repetition: from Pust’ nashi zhEshchiny to konchAite vashi <’Ah’>, again with two foursomes on the same note (again E);

- -

- Then (lines 18–19), the number of repetitions returns to five: from Ia ne liubItel’ to pridiOtsia, chto;

- -

- And at the end (lines 21–23) it again reaches six: from chto nashi dEvushki to briunEt, oni sebiA.

This crescendo of monotonous repetitions, varied only by the minimal and steady downward movement, conveys the protagonists’ frustratingly stubborn mood of self-assertion. In Part 1, this attitude is more or less understandable, as it is, so to speak, defensive and self-contained; but in part 2, it becomes pronouncedly aggressive, remaining all the while tediously monotonous—to the point of being boring. The longest repetitions are among the final ones, clearly delimited by word boundaries, set to a clear rhythmical–melodical pattern, and semantically the sharpest: 14 poslUshajte—14 porA uzhe—21 za dEnezhki—22 predstAav’ sebe—22 paskUdina—22–23 brjunEt oni. These leitmotif peons II carry AWD’s thematic message by combining several of its major formal characteristics: pre-bar intros, repetition of notes and sequences, minimal downward melodical movement, and focus on key words (often peonic).

11. Concluding the Discussion: Poetic Semantics of the Performance

The overall ideological–emotional message of the song is marked by the same ambiguity as its formal structures, and one wonders whether that is a product of the young bard’s deliberate strategy or his artistic immaturity.

To put it very briefly, the confrontation between the “poor but nobly selfless” protagonists and the “rich, self-serving and cynical” antagonists cannot but reveal both parties’ commitment to similar values: posh restaurant life with its doormen, private event rooms, expensive jewelry, and control over pretty women.20 The protagonists, that is, my (we), are of course within their rights, but is that enough for a meaningful poetic statement? A moralistic emphasis is allegedly there, but it is not as unambiguous as it is commonly accepted—witness the contemporaries’ mixed opinions cited in the beginning of this essay.

The challenge posed by the protagonist (and, indeed by the speaker and most likely by the author) to the antagonists and thereby to the Soviet establishment in general is quite obvious. And yet, there are no signs of the protagonist and his party’s predilection for something essentially different, be it classical music, hiking in the mountains, political dissidence, study of a forbidden subject, say genetics, or secret reading of Boris Pasternak’s prohibited novel Doctor Zhivago. And remarkably, today the Web is dominated not by Okudzhava’s own authorial rendition of the song, but by its deliberately off-color, “gangsta” versions, for example, one by Alexander F. Sklyar.21

In light of all this, the opposition “honest poverty vs. wicked wealth,” perfectly legitimate itself and quite relevant to the times of AWD’s creation, is if not invalidated, at least somewhat devalued. The class struggle attitude boiling down to a redistribution of material values is an age-old theme that it has been instructively treated in literature—just think of Anton Chekhov’s “Anna at the Neck,” where the underdog at first looks at the masters of life with envious indignation but lo and behold ends up joining the top-dog torturers.

In 1958, the time had not yet come for the songs of Vladimir Vysotsky, who would treat this, shall we say, Zoshchenkovian topos in good taste and with a grain of irony. As for Okudzhava, in his later work, he would not go in that direction, trusting his inner tuning fork and naturally tending to distinguish himself from his poetic competition (the way Boris Pasternak in his time had deliberately suppressed the “Mayakovskian” overtones of his own early diction).

In his early period, Bulat Okudzhava was known to vacillate between patriotic, Komsomol, Red Army, working-class, courtyard, and semi-criminal styles. Only later would he develop his trademark meta-sentimentalist poetics. As for AWD, it will remain a telling—consistently ambiguous—evidence of his quest for stylistic maturity.

The analytical scrutiny of Bulat Okudzhava’s “poetic semantics” has uncovered a set of interwoven ideological, emotive, and performative features. The inherent discursive ambivalence permeating the thematic content and structural framework of his compositions results in a dialectical discourse that problematizes the nature of this ambivalence—as a deliberate stratagem or an exuberant manifestation of the fledgling bard’s artistic whimsy. The opposition of the protagonists’ “noble destitution” and the antagonists’ “cynical opulence” serves as a source of subtle irony. While a moralistic undercurrent permeates the narrative fabric, the interpretative latitude afforded by its inherent ambiguity generates a plurality of conjectures, as evidenced by the wide range of opinions espoused by Okudzhava’s contemporaries. The confrontation transcends the mere realm of narrative discord, becoming a symbolic gauntlet hurled at the established societal mores and implicitly challenging the cultural hegemony of the Soviet regime. However, the absence of a coherent alternative ideological paradigm on the part of the protagonists signals the song’s critical limitations, attenuating its central opposition. In the broader panorama of Soviet cultural deployment, the enduring resonance of Okudzhava’s amalgamation of song, verse, and poetics in general, alongside its manifold reinterpretations, underscores its timeless pertinence that transcends generational chasms. The enduring significance of the song resides not solely in its critique of societal norms, but also in its reflection of Okudzhava’s artistic odyssey and the broader sociocultural landscape that engendered it.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | On the underground and experimental Soviet music, see, in particular: (Hakobian 2017; Ioffe 2022; Schmelz 2009; Sitsky 1994; Smirnov and Pchelkina 2011; Taruskin 1997; Vorobiev and Sinaiskaia 2007). For general comments and suggestions, I am grateful to Dennis Ioffe, Lada Panova, and Igor Pilshchikov; special thanks for musicological advice go to P.A. Berliand, A.B. Zhurbin, B.A. Katz, V.A. Frumkin, and M.I. Shvedova—A. Z. |

| 2 | See, for instance: (Boiko 2013; Rozenblium 2015; Burov 2018; Smith 1988; Novikov 2017; Bogomolov 2019). |

| 3 | On the phenomenon of Soviet-time Russian bard song, see (Novikov 2017; Bogomolov 2019). |

| 4 | That AWD is in a class of its own is an unexpectedly confirmed by the fact that it is not included in the authoritative two-volume American edition of the bard’s corpus: (Okudzhava 1982, 1986) (comprising 65 + 28 = 93 songs). |

| 5 | For additional scholarly discussions of Okudzhava, see, in particular: (Aleksandrova 2021; Bogomolov 2004; Freidin 2000; Boiko 2013; Rozenblium 2015; Burov 2018; Smith 1988; Shragovits 2013; Zholkovskii 2005). |

| 6 | In fact, the verse in AWD is not accented, it is almost perfectly correct free iambic. |

| 7 | See (Okudzhava 2001, pp. 145–46) (and V.N. Sazhin’s commentary on pp. 617–18); one can listen to the author’s performance of the song here: Available online: https://youtu.be/CFPaQV59HFo (Accessed on 30 March 2024). |

| 8 | In fact, in online versions of the lyrics, the lines are sometimes grouped in this way. |

| 9 | Such variation of anacruses in disyllabic meters is acceptable in Russian poetry, but only in nursery rhymes and light verse (see Gasparov 1989, p. 188). |

| 10 | A modest rearrangement of stanzas II and III would increase the regularity of the alternations: FFM MFMF MDDM FDDM MFMFMDMM. |

| 11 | Noted in (Nikolaeva 2000, p. 467). |

| 12 | “Glancing, gazing, staring” was a recurrent motif in Okudzhava’s songs of the period; an extensive list of 1957–1964 examples can be seen in (Zholkovskii 2022, p. 272). |

| 13 | To be sure, such deliberate “irregularity” has a venerable tradition, cf. the beginning of the poem “Groza, momental’naia navek…” (A storm, instantaneous forever) by Okudzhava’s favorite poet Boris Pasternak: A potom proshchalos’ leto/S polustankom… (And then summer was saying goodbye/To the whistle-stop…). In prose, a classic example of an abrupt beginning the first phrase of Anton Chekhov’s short story “Anna at the Neck”: Posle venchaniia ne bylo dazhe legkoi zakuski (After the wedding there was not even a light snack…). As will be argued, musically, AWD also starts in an unconventional way: with three off-beat notes. |

| 14 | Incidentally, the conjunction A was Okudzhava’s favorite: in the poems of the 1950s (i.e., in texts No. 1–131 of the academic collection: Okudzhava 2001, pp. 89–197), it occurs 143 times (almost exclusively at the beginning of lines): in 13 cases, twice in one text; in 13 cases, three times in one text; in 4 cases, four times; in 2, five times; and in another 2 cases, six times in one text. Thus, the majority of the lyrics (107 out of 143) feature this conjunction more than once. On pp. 142–47 of the collection (i.e., around and including AWD, the conjunction A is used 20 times, of which on two occasions (in AWD and in “Nurse Maria”)) it opens the text. On the whole, AWD is one among the five Okudzhava texts beginning with A. My guess is that this conjunction (absent in most European languages) appealed to Okudzhava precisely due to its intermediate, ambiguous, half-way, “compromise”, position between the polar opposites И (And) and Нo (But). |

| 15 | I am borrowing this formulation from N.A. Krymova, who pointed out that “… the verbs in the imperative mood in Okudzhava’s poems are devoid of imperativeness. The ‘mood’ is not one of ‘ordering’ or ‘instructing’ the reader but rather that of ‘unobtrusive suggestion’ [nenaviazchivoe vnushenie]” (Krymova 1986, p. 362; see also Dubshan 2001, pp. 20–21). But in AWD the “unobtrusiveness,” which has not yet become programmatic in Okudzhava, does give way to its opposite. |

| 16 | I have not found a published musical notation of the song and am using one made at my request by P.A. Berliand, who, for the sake of convenience, has transposed the A minor of the author’s performance a quint higher—to E minor. |

| 17 | In the musical notation, the bars are separated by vertical lines, and I show them with a similar sign: |. |

| 18 | The musical notation clearly shows that such bars contain four identical notes of equal duration (four eighths) plus four identical notes a tone lower. |

| 19 | A clear parallel to such an increasingly aggressive monotonous sequencing is in Okudzhava’s “Song about midnight Moscow.” There, the opening lines of all the stanzas are sung on the same note, and in stanza II, the series reaches its climax, When the leaden rains/were beating up so on our backs [lu-pI-li tAk po nA-shim spI-nam], /that no leniency could be expected, the most “cruel” line is emphasized by a deliberately slow, syllable by syllable, chanting (see above the highlighted line in Russian). The difference is that, while in AWD the sequences descend, here, they ascend. A similar monotony can be observed, as suggested by V.A. Frumkin, also in the opening and concluding lines of the song “Byloe nel’zia vozvratit”’ (One can’t bring back the past…). |

| 20 | On Okudzhava’s personal views regarding women in particular, see (Okudzhava 1988). |

| 21 | See, e.g., available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1R2zQj9fSVA/ (accessed on 29 March 2024). |

References

- Aleksandrova, Maria. 2021. Tvorchestvo Bulata Okudzhavy i mif o zolotom veke. Moskva: Flinta. [Google Scholar]

- Bogomolov, Nikolai. 2004. Bulat Okudzhava and Mass Culture. Russian Studies in Literature 41: 5–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bogomolov, Nikolai. 2019. Bardovskaia pesnia glazami literaturoveda. Moscow: Azbukovnik. [Google Scholar]

- Boiko, Svetlana. 2013. Tvorchestvo Bulata Okudzhavy i russkaia literatura vtoroi poloviny XX veka. Moskva: RGGU. [Google Scholar]

- Burov, Aleksandr. 2018. Bulat Okudzhava: Shtrikhi k lingvisticheskomu portretu: Monografiia. Piatigorsk: Piatigorskii Gos. Universitet. [Google Scholar]

- Bykov, Dmitry. 1997. Beseda Dmitriia Bykova s Bulatom Okudzhavoi. Profil № 6. Available online: https://ru-bykov.livejournal.com/3533084.html (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Bykov, Dmitry. 2009. Bulat Okudzhava. Moscow: ZhZL. [Google Scholar]

- Dubshan, Leonid. 2001. “O prirode veshchei”. Okudzhava 2001: 5–55. [Google Scholar]

- Freidin, Iury. 2000. Slovo dlia muzyki: Peremennaia anafora i variantivnyi refren: Ob odnoi pesennoi osobennosti stikhotvorenii Bulata Okudzhavy. Russian Literature 48: 131–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparov, Mikhail. 1989. Ocherk Istorii Evropeiskogo Stikha. Moscow: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Hakobian, Levon. 2017. Music of the Soviet Era, 1917–1991. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2022. The Experimental Sounds: From Historical Musical Avant-Garde to Cultural Underground(s). Edited by Mark Lipovetsky, Ilia Kukui, Klavdia Smola and Tomas Glanc. Oxford: The Oxford Handbook of Soviet Underground Culture, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krymova, Natalia. 1986. “Svidanie s Okudzhavoi”. Druzhba narodov 5: 260–64. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaeva, T. 2000. Neznamenatel’nye slova i tekst. 1. ‘A my shveitsaru: Otvorite dveri!’ in Nikolaeva T. Ot zvuka k tekstu. Moscow: Iazyki russkoi kultury, pp. 462–68. [Google Scholar]

- Novikov, Vladimir. 2017. Literaturnye mediapersony XX veka: Lichnost’ pisatelia v literaturnom protsesse i v mediinom prostranstve. Moscow: Aspekt Press. [Google Scholar]

- Okudzhava, Bulat. 1982. 65 Songs. Edited by Vladimir Frumkin. English Translated by Eve Shapiro. Ann Arbor: Ardis. [Google Scholar]

- Okudzhava, Bulat. 1986. 28 Songs. Edited by Vladimir Frumkin. English Translated by Tania Wolfson, Kirsten Painter and Laura Thompson. Ann Arbor: Ardis, Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Okudzhava, Bulat. 1988. Devushka moei mechty: Avtobiograficheskie povestvovania. Moskva: Moskovskii rabochii. [Google Scholar]

- Okudzhava, Bulat. 2001. Stikhotvoreniia. Edited by V. N. Sazhin and D. V. Sazhin. St. Petersburg: Akademicheskii Proekt. [Google Scholar]

- Rassadin, Stanslav. 1990. Prostaki, ili Vospominaniia u televizora. Iskusstvo kino. № 1. pp. 14–30. Available online: https://disk.yandex.com/i/5-cxVyftorMGF (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Rozenblium, Olga. 2015. Bulat Okudzhava i avtorskaia pesnia (Bulat Okudzhava and the Author Song). Russian Literature 77: 175–89. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, Peter. 2009. Such Freedom, If Only Musical: Unofficial Soviet Music During the Thaw. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shragovits, Evgeny. 2013. Rabota mozga i poeticheskii tekst: Analiza poeticheskogo teksta na primere Bulata Okudzhavy. Novyj mir 12. Available online: https://magazines.gorky.media/novyi_mi/2013/12/rabota-mozga-i-poeticheskij-tekst.html (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Sitsky, Larry. 1994. Music of the Repressed Russian Avant-Garde, 1900–1929. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, Andrey, and Liubov’ Pchelkina. 2011. “Russian Pioneers of Sound Art in the 1920s.” Red Cavalry. Creation and Power in Soviet Russia between 1917 and 1945. Edited by Rosa Ferre and La Casa Encendida. Madrid: Communicatrix. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Gerald. 1988. Okudzhava Marches on. Slavonic and East European Review 66: 553–64. [Google Scholar]

- Taruskin, Richard. 1997. Defining Russia Musically. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobiev, Igor, and Anastasia Sinaiskaia. 2007. Kompozitory russkogo avantgarda. Moscow: Kompozitor. [Google Scholar]

- Zholkovskii, Alexander. 2005. “Rai, zamaskirovannyi pod dvor: Zametki o poeticheskom mire Okudzhavy” in Zholkovskii A. In Izbrannye stat’i o russkoi poezii. Moscow: RGGU, pp. 109–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zholkovskii, Alexander. 2022. A my shveitsaru: ‘Otvorite dveri!’: K strukture netipichnogo teksta Okudzhavy. Zvezda 1: 259–73. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).