Abstract

The present research analyses the role of the Egyptian artist within the context of New Kingdom art, paying attention to the appearance of new details in Theban tomb chapels that reflect the originality of their creators. On the one hand, the visibility of the case studies investigated is explored, looking for a possible explanation as to their function within the tomb scenes (such as ‘visual hooks’) and offering a brief experimental approach. Tomb owners benefitted from the expertise and originality of the artists who helped to reaffirm their status and perpetuate their funerary cults. On the other hand, iconography can include examples of the innate creativity of artists, including ancient Egyptian ones. The presence of such innovative details reflects the undeniable creativity of artists, who sought stimulating scenes which were sometimes emulated by contemporaries and later workmates. Significantly, some of these innovative details reveal unusual poses and daily-life character, probably related to the individuality of the artists and their innovative spirit. In other words, the creative impulse is what leads artists to innovate. In this sense, creativity must be understood as the dynamic of the visual arts that determines constant evolution of styles.

1. Introduction

The art of ancient Egypt may be considered, in my opinion, one of the most sophisticated expressions of the search for beauty by humankind,1 and it has been admired and appreciated since Graeco-Roman times. The New Kingdom period stands out as an extraordinary stage within Pharaonic art, in terms of intense production, evolution of styles, and creativity. In particular, the art from the Theban necropolis offers an exceptional possibility to understand the creative process, although this vast corpus of images has been traditionally studied only from an iconographical and textual point of view. The present research hopes to show its potential using a different approach, namely focusing on innovation, originality, and emulation in funerary pictorial art as a reflection of elite power in the New Kingdom.

The role of Egyptian artists has been a rather neglected topic within the discipline of Egyptology until recent times. On the one hand, several studies have focused on their importance and individuality (Andreu 2002; Andreu-Lanoë 2013; Laboury 2013), their role as creators of the royal tombs in the New Kingdom (Valbelle and Gout 2002), as well as their social relevance as artists (and not mere artisans) and their self-depictions (Harrington 2015; Devillers 2021, 2023; Devillers and Sykora 2023). On the other hand, the practices of Egyptian painters regarding the phenomenon of copy and emulation have been recently explored, for instance, focusing on Theban artists (Den Doncker 2017, 2022), or on funerary provincial art such as the necropolis in Elkab and its Theban connections (Devillers 2018). A similar approach was developed in the analysis of the transmission of motifs and iconography located in different areas (i.e., the Memphite area) and later periods (Pieke 2022). Furthermore, some studies have analysed the weight of originality within Theban tombs, something that appears to be a complex and nuanced phenomenon (El-Shahawy 2010).

The importance of the aesthetic dimension of Egyptian funerary art should also be taken into account, not only for artists as creators but also for beholders2 (Kemp 1998). Firstly, the aesthetic dimension was relevant for artists who produced original and appealing scenes with balanced compositions and attractive colours, presumably trying to create artworks that could satisfy their own expectations. The role of the so-called ‘scribes of contours,’ or draftsmen, responsible for sketching the decorative program of the tomb chapels, was likely crucial in this search for aesthetic satisfaction. Secondly, art producers tried to meet the demands and the needs of their patrons, to meet those elite desires for a personal and unique memorial monument. Elites and non-elites were part of a social arena that used art production to highlight status and position, or, in other words, to distinguish themselves from the rest of the population and to reaffirm their power vis-à-vis each other. In ancient Thebes, building an impressive and enormous tomb was restricted to the most powerful elite, and those belonging to the lower elite had to look for other ways of creating an attractive funerary monument. For both types of commissioners, having an expert artist was probably a valuable tool to create appealing monuments, thus enhancing their chances of perpetuating their funerary cult. Thirdly, aesthetic satisfaction may have been one of the interests of ancient Egyptians when visiting a tomb-chapel, admiring the scenes, seeking to delight their senses, and even leaving graffiti to show satisfaction and express the beauty of the monuments using formulaic expressions such as “they found it very beautiful in their hearts” (Den Doncker 2012, p. 27). It is well known that private Theban tombs could be visited, although they were not accessible to all, and would have been secured by sealed wooden doors most of the time. With great likelihood, family members with priestly roles would have had the greatest level of interaction with the deceased tomb owner, together with other relatives and friends who visited the tomb in relation to the funerary cult and at certain festivals (Harrington 2015, p. 144). For all those types of potential audience members, but especially for occasional visitors, attractive tomb decoration would have been a relevant factor (even in some way could have determined the periodicity of visits and therefore the perpetuation of the memory of the deceased).

The aim of this paper is to analyse the presence of innovative details in New Kingdom Theban tombs, which prove the originality (defined as the quality of being novel or unusual) and individuality of the artists and could have been functioned as intentional artistic resources, used to attract the attention of the beholder and working as ‘visual hooks’. The term Blickpunktsbilder, or ‘focal point representation’ (Fitzenreiter 1995; Engelmann-von Carnap 1999, pp. 410–17), has been used in a broad sense to describe the significance of the images, as several scholars have noted that the images located on the focal walls often included innovative or accomplished rendering with sophisticated colouring. These scenes (usually located on the back walls of the transverse hall) were relevant to show the deceased’s status, identity, relationships, and also social environment. (Hartwig 2004, pp. 16–17, 51). Roland Tefnin had already explored the rhetorical use of ‘visual hooks’ as mimesis, and the complexity of some New Kingdom Theban scenes that reveal a rhetoric of the image (Tefnin 1991, pp. 64, 71). For the purpose of the present research, a more concise use of the term ‘visual hooks’ may be appropriate, referring specifically to the artistic resources used to attract the gaze of the viewer.

The individuality of Egyptian artists seems to have been crucial to create innovative details, which do not seem to add significant religious or sociological meanings, but which would catch the attention of the beholder and eventually enhance visits to the tomb-chapel. Therefore, tomb owners, as part of the elite, would benefit from the expertise and originality of the artists, which served to reaffirm their status and perpetuate their funerary cult. Whatever the precise function of new artistic details, they seem to show the creativity of the Egyptian artists, immersed in a constant process of innovation which was intrinsic to the work of any artist.

2. Creativity and Emulation

Seeking proportionality and balance seem to have been two main concerns of the Egyptian artists. The study of the stages of the tombs’ decoration, reflected in the details of unfinished scenes with corrections to the figures, clearly shows the attempts of the Egyptian artists to produce the most perfect and proportioned figures, as well as balanced and appealing scenes (Bryan 2001). But apart from the search for proportion detected in the images, artists seem to have consciously looked for innovative elements, looking for a satisfaction in the realm of aesthetics, developing their creativity, and producing an artistic play. In this regard, we may recall the theorical approach of Johan Huizinga, who introduced the concept of ‘Homo ludens’ and the idea of play as a quality of freedom. Huizinga emphasises the competitive nature of plastic arts, proposing a freedom factor that proved how individuality of creation is contained within any artistic performance. Besides, competition is part of the social dimension in the plastic arts (Huizinga 2007, pp. 214–15). Therefore, the ludic aspects of new details, unusual poses, or amusing figures located in Theban funerary art may reveal the individuality of the artist and his desire to distinguish himself among others. Also, patrons seem to have developed a process of competition in the construction and decoration of their tombs, trying to emulate the achievements of their relatives (or their predecessors in their positions in the administration).

The scenes usually included on Theban tomb-chapels played an outstanding function in the religious sphere, but their aesthetic dimensions might have also been somehow relevant for the Egyptian artists. Many of the features recorded in Theban paintings seem to correspond with the ideas of art and the world of perception proposed by the movement known as the Gestalt, particularly the studies of Rudolf Arnheim. His ideas regarding balance, composition, rhythm, colour, and the simplicity of shapes show the complexity of figurative art (Arnheim 1995, pp. 51, 79). For instance, balance is a pivotal element in Egyptian compositions, as exemplified in the ‘fishing and hunting in the marshes’ scenes and their mirror images, like the well-known scene in the tomb of Nakht, TT 52 (Davies 1917, plate XXIII). A sense of visual rhythm seems to be a remarkable feature in the usual rows of people depicted in registers, in which artists include groups of repetitive series of figures, sometimes separated by a figure in a different or rare pose, as seen in the scene of eight Cretan emissaries represented in the tomb of Rekhmire (Davies 1943, plate XIX). The use of colours was connected to symbolism in Egyptian art (Baines 1985), but during the 18th Dynasty an aesthetic and complex use of colour was developed, probably linked to the discovery of new pigments (Ragai 1986, p. 75).

Creativity was a rather problematic topic within Egyptology, as Dimitri Laboury recently summarised: “the issue (or non-issue) of creativity in this artistic production has almost always been tangled and even confused with that of tradition, in the long-lasting preconceived idea of the so-called immutability of Ancient Egyptian Art (…). The two concepts involved, tradition, on the one hand, and creativity, on the other, actually do not contradict nor exclude one another, but, on the contrary, articulate with each other. Just as nothing can be considered new if it is not compared to something older, tradition does not impede creativity but constitutes the necessary background for its development” (Laboury 2017, p. 230).

Egyptian funerary painting and relief were strongly linked to tradition, as the scenes represented in a tomb had to fulfil specific functions that were related to religious rites, the funeral of the deceased, the symbolism of regeneration, or to the self-representation of the tomb owner. Every single tomb was a new challenge and had to be redefined separately in principles of conception and composition, conforming to such traditional themes. As remarked by Pieke, despite the given traditions and defined artistic conventions, many images show certain influences and shifts of perspective. Thus, themes, motifs, types, iconographies, and styles refer to different frames of tradition and reference, as well as to individual choices made by artists and/or patrons (Pieke 2022, p. 50). Regarding the Theban necropolis, it has been stated that no tombs are exactly alike (Robins 2016, p. 202). Within the traditional repertoire, artists had to adapt scenes to each tomb, emulating the ones decorated by their predecessors. The process of emulation and copying of specific scenes has been recently studied by Dimitri Laboury, who introduced the concept of intericonicity, sometimes also called interpictoriality. This can be defined as ‘the shaping of an image’s meaning or form by another image, acknowledging the fact that any image exists within a network of other images, with which it has diverse forms of relations that determine its meaning and form, as well as its very existence’ (Laboury 2017, p. 248). The variations in the transmission of an image should not be considered like errors in a duplicative and mechanical process, but as tokens of creativity.

As Den Doncker has pointed out, “the ancient Egyptian creative process seemingly worked like a puzzle, so that painters should be now considered as composers of patchworks specialised in quoting standard iconographic repertoires, the concept of copy appears to have lost its full meaning, or at least its accuracy” (Den Doncker 2017, p. 335). Regarding the present research, the variations of an image and any new details will be studied within the framework of the concept of intericonicity, considering them as examples of originality and creativity. Furthermore, original iconographic elements could have worked as ‘visual hooks’, that is, details or poses which attracted the attention of the beholder. The presence of ‘visual hooks’ in the Theban tombs has been already proposed, for instance, in the analysis of the funerary monuments dated to the reigns of Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III. In several tombs, the texture of the painting in combination with innovative and amusing motifs placed at eye level were used in the paintings to draw the viewer to the scene (Hartwig 2004, p. 51).

In the following pages, some examples of innovative details will be analysed in order to detect their diffusion within the repertoire of the Theban tombs, to gauge their uniqueness, and to understand their role as artistic resources.

3. Innovative Details: ‘Visual Hooks’ and Originality

3.1. Case Study 1. ‘Standing Girl in Three-Quarters Pose’

The tomb of the vizier Rekhmire is one of the best-known constructions in the necropolis, especially appreciated for its extensive decoration and the quality of the craftsmanship. It was published in the mid-twentieth century (Davies 1943) and has been the topic of extensive research dealing with the historicity of some of the scenes depicted as well as included texts such as the Duties of the Vizier. More recently, TT 100 has been the focus of new approaches dealing with the sources of inspiration for the decorative program (Den Doncker 2017, pp. 346–49) or with its architecture in relation to landscape (Muñoz Herrera 2023).

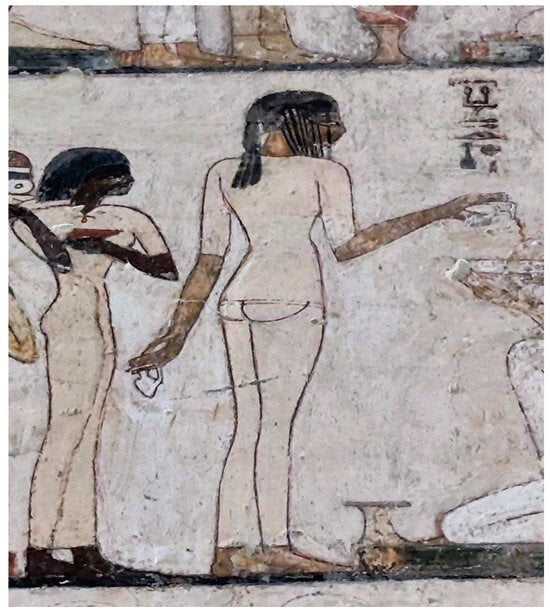

The decoration of the corridor of the tomb of Rekhmire includes the typical banquet scene so common in Theban tombs (east end of the left wall), in this case composed of eight registers due to the unusual height of TT 100 (Davies 1935, pl. XXVI, PM I.1, p. 213, (18), III). In the sixth register (from bottom to top), several women are depicted sitting and being attended by standing female servants, creating a rather repetitive composition. In a middle position within the sixth register, one female servant is rendered in a rare pose: she is standing pouring a liquid into the cup of a lady, but she is depicted in a three-quarter pose (Davies 1943, p. 62, pl. LXIV). The pose suggests the idea of bodily rotation (Figure 1), increased by the presence of the left foot in the foreground. The tomb of Rekhmire includes other examples of human figures depicted in poses that do not correspond to Egyptian canonical representations of the human figure: for instance, in the scene of the inspection of works, which includes a group of sculptors and workers, the head of one of the sculptors is seen from behind (Volokhine 2000, p. 36, Figure 35). In fact, TT 100 comprises several examples of very rare details of human positionality, which prove the originality of the group of artists who worked on the decoration.

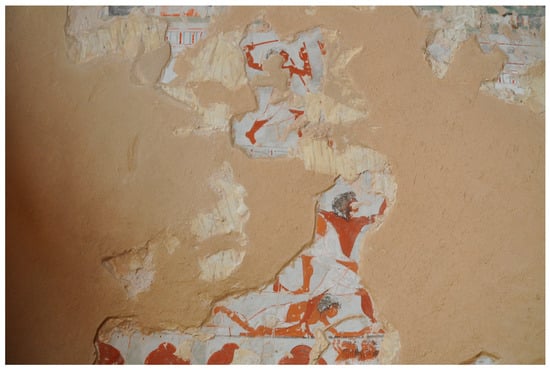

Figure 1.

Detail of a banquet scene, east end of the left wall at the corridor, Tomb of Rekhmire, TT 100 (Photograph by the author).

To my knowledge, the maidservant in three-quarter view seems to be a unique depiction of a figure standing in this rare pose, maybe connected to the fact that tombs in which direct copies of TT 100 iconographic units are well attested have the peculiarity of being poorly preserved, especially TT 29 (Den Doncker 2017, p. 349). But the interest of this detail here focuses on its possible role as a ‘visual hook’ in TT 100. The sixth register includes five groups of figures, mainly ladies sitting or squatting, and the figures of the maidservants serve as vertical breaking points in the overall horizontal, register-based composition. It seems that the inclusion of this ‘anomalous’ figure of a servant in a three-quarter pose seems to engage the viewer, revealing the originality of the artist. In this regard, we could mention the research by Valerie Angenot on the ‘vectoriality’ of the Old Kingdom, a concept used to designate the movement of the gaze suggested either by a vector (by example of temporal type) or by the plastic (Angenot 1996, p. 7). Different models of vectoriality seem to have been noticed, such as spiral, broken, chiasmus, boustrophedon, etc., revealing a remarkable variety. The movement of the gaze suggested by the plastic can be a means of expressing the idea of completeness desired by the artist (Angenot 1996, p. 21).

The depiction of the serving girl is placed on the higher part of the tomb of Rekhmire, 317 cm from the floor’s surface, not at eye level. It could not have been seen at first sight, but only appreciated after a careful ‘reading’ of the scene. Unlike other tombs, Rekhmire’s tomb-chapel enjoys sufficiently good natural lighting for the decoration, at least in the location of the banquet scene, to be clearly visible without artificial support. The high position of this girl in a three-quarter pose, working as a ‘visual hook’, would serve to draw the visitor’s eye to the upper registers of the scene, whose position is abnormally high due to the atypical architectural configuration of the long hall. Being a unique detail, it may have increased the attractiveness of the scene.

Significantly, Tefnin analysed the maidservant in TT 100 in an interesting work focused on the Egyptian image, remarking that this unusual figure was not an attempt to introduce a real sense of depth, but an original combination of different points of view, guided by a certain free search, a pure play with the shapes. Noteworthy for Tefnin was the presence of the left foot in the foreground, which might be considered a tentative form of illusionism and therefore assumed to have been a mistake, but if we admit that the artist’s whim consisted of playing freely with the means of representation, without being tied to an absolute fidelity to reality, the image can be fully understood (Tefnin 2000, pp. 33–34). To sum up, the unusual pose of the girl seems to be an example of the artist’s freedom that may have attracted the gaze of the beholder.

3.2. Case Study 2. ‘Man Resting in a Chariot’

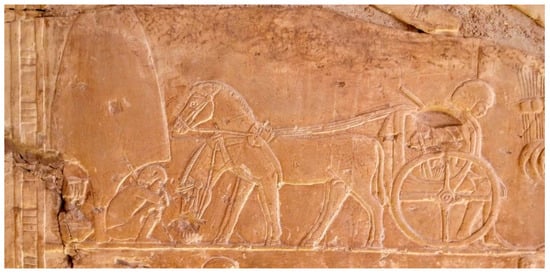

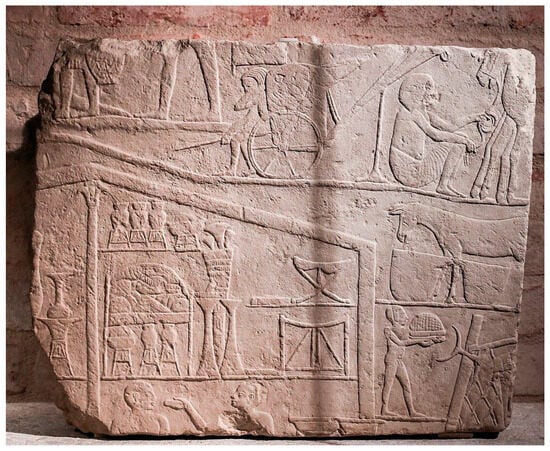

This section will deal with a very unusual detail recorded first in the Theban tomb of Khaemhat, TT 57, dating to the time of Amenhotep III (Hussein Ali Attia 2022), an interesting monument decorated in relief. The iconographical program includes a scene where the tomb owner is giving offerings and surveying the fields on the east wall of the transverse hall (Hussein Ali Attia 2022, p. 115, pl. 25, PM I.1, p. 116, (13), III). This type of agricultural scene with chariots is also located in other tombs, specifically in 16 tombs, 11 from the 18th Dynasty, 4 from the Ramesside period, and 1 from the Late period (Hussein Ali Attia 2022, p. 115), but the one in TT 57 has several original details (El-Shahawy 2010, p. 63). In this harvesting scene, an interesting detail is represented: a chariot driver of two horses is depicted in an unusual pose. The man is squatting and looking down, resting his head on his arms (holding in one hand the reins and a whip, and a stick in the other hand). It seems his head is nodding, suggesting he is asleep (Figure 2). The placement of this unusual man, located on the fourth register (from bottom to top), is at eye level, assuming a standing position of the beholder. The iconographic element of this resting man is located at 121 cm from floor level (bearing in mind that the total height of the transverse hall is 280 cm). In my opinion, the purpose of this original detail is two-fold: it may have functioned as a ‘visual hook’, attracting the attention of the viewer to the end of the composition, and it seems to reinforce the spontaneous character of this ‘daily life’ scene.

Figure 2.

Detail of the east wall of the transverse hall, Tomb of Khaemhat, TT 57. (Photograph by the author).

Interestingly, the detail of a man resting on a chariot is found in another Theban tomb: the unlocated tomb of Nebamun, TT E2, (presumably from Dra Abu el-Naga), well known from the dislodged fragments kept in the British Museum collection. Although the exact date of the original tomb-chapel has not been confirmed, it seems to belong to the reign of Amenhotep III, based on the style. One of the fragments of the tomb decoration shows two registers belonging to an agricultural scene within the context of the crop assessment (EA37982). The fragment shows two registers, a horse-drawn chariot with a man standing above, and a cart drawn by onagers beneath. On the lower register, a man is sitting on the floor of the chariot with his legs dangling over the edge; he is resting and looking down (Parkinson 2008, pp. 110–15). The pose of this man is very similar to the one from TT 57, although the figure from the British Museum fragment seems to be resting rather than sleeping (Figure 3). Unfortunately, the exact position on the fragment within the wall cannot be confirmed, but it has been tentatively proposed that the original wall may have had four registers, the fragment with chariots having been located in the second upper register (Parkinson 2008, p. 112, Figure 118). Furthermore, the intention of the artist who painted this scene seems to have been to emphasise the contrast between the active pose of the man in the upper part and the passive attitude of the man in the lower part. Given the similar date of both tomb-chapels (TT 57 and the one belonging to Nebamun) and the striking similarities between the iconographic element of a man sitting on a chariot, it may be assumed that one of them is inspired by the other. Furthermore, the detail of the sleeping man on a carriage may have been copied in TT 302, a Ramesside construction located in Dra Abu el-Naga, where the image of a charioteer sleeping was also included (PM I.1, p. 381, (1), II). Unfortunately, the tomb is still unpublished, and the photographs of the scene kept in the University of Pennsylvania Archive have not been useful to trace the motif.3

Figure 3.

Fragment from the tomb of Nebamun (EA37982, © The Trustees of the British Museum).

Surprisingly, another unusual iconographic element of a man resting on his chariot is located outside the Theban necropolis, more specifically in the Memphite tomb of Horemheb. A fragment corresponding to the north wall of the first courtyard, now kept in Berlin (Neues Museum ÄM 20363), shows a man sitting on a carriage looking down, with his head resting on his arms (Martin 1989, p. 38, pl. 28–29). The context is completely different, as the whole scene shows a military encampment connected to the activities of Horemheb as Generalissimo of Tutankhamun. The relaxed position of this man increases the daily-life character of the military scene (Figure 4). Although the scene is not currently in situ, this original detail seems to have been located on the upper register, presumably at eye level, as the whole scene has been reconstructed with three preserved registers. The similarity between this scene and the one recorded in TT 57 is striking (perhaps related to the mobility of artists), and the creators of the Memphite tomb seem to have employed this original pose of the assistant of the charioteers as a ‘visual hook’ in order to pull in the gaze of the viewer.

Figure 4.

Fragment from the Memphite tomb of Horemheb, corresponding to the north wall of the first courtyard, now kept in Berlin (Neues Museum ÄM 20363). Wikimedia Commons.

3.3. Case Study 3. ‘Sleeping Man under Tree’

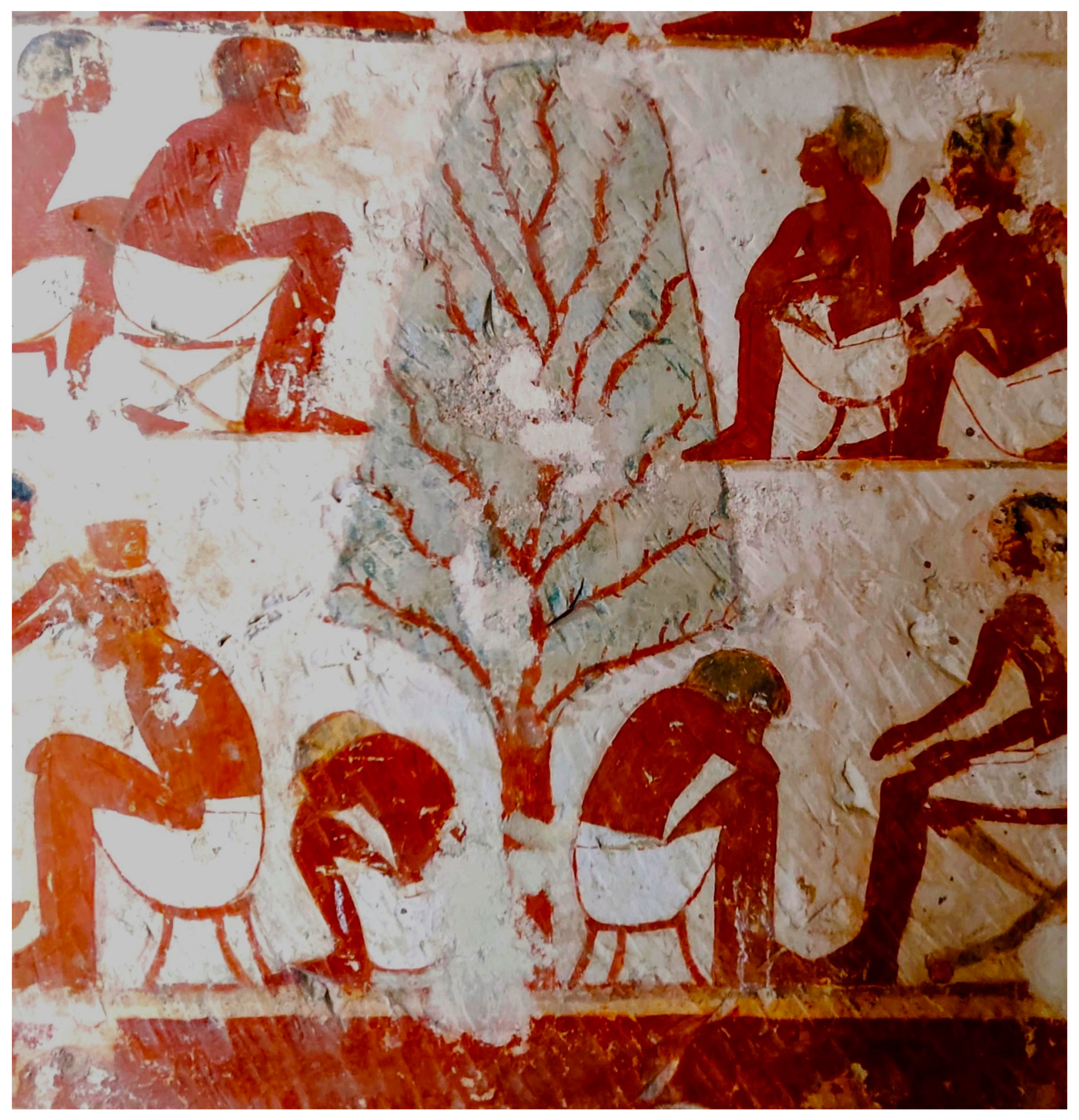

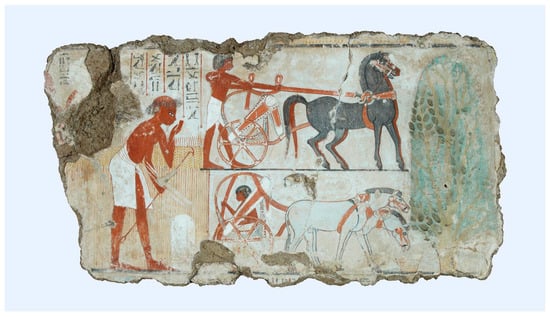

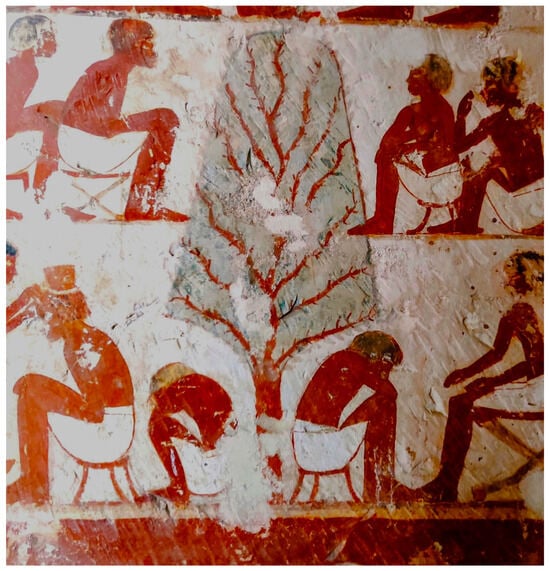

Human figures depicted resting or sleeping are present in Egyptian funerary art, as seen in the previous pages, but a specific new detail of a sleeping man under a tree can be traced in a few Theban tombs dated to the 18th Dynasty. The tomb of Userhat (TT 56), dated to the reign of Amenhotep II, provides the first example of this iconographic element, located on the south wall of the transverse hall (Beinlich-Seeber and Shedid 1987, PM I.1, p. 112, (11), IV). The context is a scene dealing with the inspection of troops, in which two registers depict a rare detail: several recruits waiting to have their heads shaved. Among the group of soldiers, two men are depicted sleeping under a tree, the one to the right is sitting on a stool and resting his head on his arms, while the one on the left is squatting on the floor in the same pose as his partner (Figure 5). This rare detail appears in the lowest register, breaking the repetitive depiction of the seated soldiers waiting to have their hair cut and adding a daily-life character to the scene. The lowest register is located 61 centimetres up from floor level (the total height of the wall being 258 cm), meaning it is clearly below eye level but easily seen when seated in the transverse hall.

Figure 5.

Detail of right wall on the transverse hall. Tomb of Userhat, TT 56. (Photograph by the author).

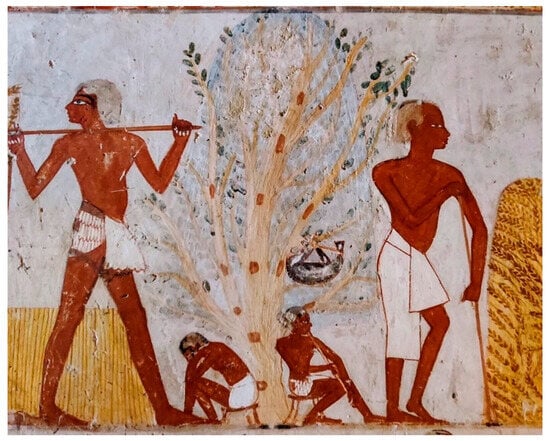

The new iconographic element appears in three other Theban tombs roughly contemporary, dated to the reign of Amenhotep III: TT 69, TT 57, and the ‘lost tomb’ of Nebamun, providing an example of intericonicity. In fact, the detail was rendered in two similar versions in TT 56 (two soldiers being depicted sleeping), but in the rest of the tombs it is registered only once, adapted from the model in TT 56. It is remarkable that the type of figure is presented differently, as the image of a sleeping man under a tree appears now in agriculture scenes. This new detail is located in the tomb-chapel of Menna, TT 69, probably dated to the reign of Amenhotep III (Hartwig 2013, p. 19, PM I.1, p. 135, (2), II), in the context of an agricultural scene in which the tomb owner is overseeing the reaping and carrying of grain in the broad hall or transverse hall (Broad Hall Left side). At the right end of the third register, two men are depicted under a tree: one is playing a reed pipe, while the other is asleep (Figure 6). This recumbent man shows an unusual pose: he is squatting on a small stool and resting his head on his arms, clearly sleeping (Hartwig 2013, p. 33, Figure 2.3a). It is located on the third register from the bottom, slightly below eye level and near the end of the wall, very close to a unique detail of two girls fighting. The inclusion of this original detail seems to catch the attention of the beholder within this common agricultural scene, reinforcing the daily-life character of the imagery.

Figure 6.

Detail of transverse hall (Broad Hall Near Left) Tomb of Menna, TT 69. (Photograph by the author).

The same iconographic element is found in the tomb of Khaemhat, TT 57, very close to the detail analysed in the first case study (man resting on a chariot). In a scene of surveying the fields, on the east wall of the hall, there is a tree to the extreme left and to the right of the tree there is a squatting person sitting on a small cushion in the shade (Figure 2). He seems to be asleep, as he is resting his head on his arms and leaning on a stick (Hussein Ali Attia 2022, p. 115, PM I.1, p. 116, (13), III). The sleeping man is represented in the fourth register (from bottom to top), at eye level, assuming a standing pose of the viewer. The original detail of this resting man is located at 121 cm from floor level (having in mind a total wall height of 280 cm).

Finally, a fragment kept in Berlin shows the same rare detail of a sleeping man under a tree (ÄM 18539). Although its exact origin is not known, Manniche has convincingly demonstrated that the fragment belongs to the ‘lost tomb’ of Nebamun, TT E2, being part of the same agricultural scene represented in several fragments from the British Museum collection. In fact, several fragments in Berlin seem to correspond to this agricultural scene from Nebamun (Manniche 1988, pp. 147–49). This particular fragment depicts three men reaping in a cornfield, a man sitting under a tree in the middle (maybe an overseer of harvesters, identified as Penruiu in a caption), and a fifth man standing holding a branch, probably to drive the animals (Manniche 1988, pl. 49; Parkinson 2008, p. 112, Figure 118). The scene preserved on the fragment in Berlin is strikingly similar to the one in the tomb of Menna, even with the same type of men reaping in the fields. The pose of the man in the middle matches perfectly with the image in TT 69: he is squatting on a brick or cushion, holding a stick, and resting his head on his arms, showing his eyes closed, clearly asleep. Noteworthy is the contrast of the image of the man asleep in a passive and relaxed pose with the movement and active duties performed by the men around.

Given the earlier date of the tomb of Userhat in relation to the rest of the tombs in which the details of a sleeping man have been recorded, it may be argued that the image in TT 56 served as inspiration for the rest, even though the artists included the figure in a completely different type of scene. Although the examples of this rare iconographic element are very similar, there are specific details and slight variations in each tomb, such as the presence or absence of a stool, or the type of dress, exemplifying the phenomenon of emulation rather than mere copying.

Furthermore, the intericonic relation of the Theban tombs TT 56, TT 69, TT 57, and TT E2 (‘lost tomb’ of Nebamun) was one of the relevant conclusions of the research by Dimitri Laboury, after his comprehensive analysis of several motifs, such as the iconographic concept of a harvesting worker jumping on a rod in order to close the lid of a bag brimful of grains (Laboury 2017, pp. 236–37). It has been possible to trace the ‘copies’ of motifs among the Theban artists working on those tombs (or being more concise, the process of inspiration and emulation). Intericonicity in Theban tombs has been also studied by Alexis Den Doncker, who has considered the phenomenon of indexicality, exploring the artistic intentionality and indexical value to apparent copies, as well as the role of the artist: “Did he mean to show implicitly how well he elaborated on the model, thereby showing off his artistic skills among his peers in some kind of internal artistic emulation dialogue? Or, on the contrary, did he try to disguise too conspicuous similarities with the model, considering they would have been deemed inconvenient—if so, according to what?” (Den Doncker 2022, p. 54). The motivations behind the emulation of certain details attested in Theban tombs (such as the elements analysed in TT 56, TT 69 or TT 57) are difficult to elucidate.

3.4. Case Study 4. ‘Single-Stick Fighting’

The topic of men taking part in fighting performances with sticks, often named dancing with sticks, is rarely depicted in Theban tombs (TT 19, TT 24, TT 31, TT 366, PM I.1, p. 469). Therefore, it does not seem to have been a favourite element for artists and tomb-owners, even though it was also rendered on Ramesside ostraca (i.e., Deir el Medina ostraca with a lively scene of two fighting men, Musée du Louvre, E 25340).

On some occasions, stick-fencing scenes are found in Theban tombs, but they seem to represent a different type of activity, such as in the tomb of Kheruef (TT 192), where men are rendered fencing with papyrus stalks within the communal activities of the sed-festival of king Amenhotep Ill (Piccione 1999, pp. 341–43, PM I.1, p. 299, (7), II). Fighting scenes are rare in New Kingdom art, whether performative fighting with sticks or wresting. In the case of wrestling (fighting which involved a grappling of bodies), it seems wrestling activities are connected to Nubians in Egyptian art (Carroll 1988, pp. 122–24) as recorded in TT 74 (Brack and Brack 1977, p. 41, Pl. 8, 28, 32¸¸ PM I.1, p. 145, (5), II), where a group of Nubians are depicted marching holding a standard which has two wrestlers on it. An interesting scene can be also found in the tomb of Merire II at el-Amarna on its east wall, in which foreign people are represented paying tribute to the royal couple (Davies 1905, pl. 38). The tribute presented by the Nubians includes not only typical products, but also the performance of dances and Nubian athletes in pairs shown in combat (wrestling, stick fencing, and maybe boxing).

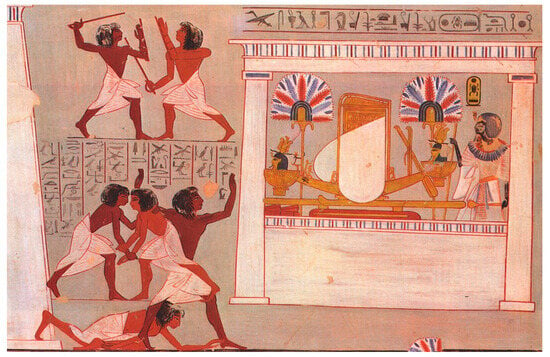

However, among the few depictions of fighters with sticks in Theban tombs there is a scene located in the transverse hall of TT 19 at Dra Abu el-Naga, the tomb of Amenmose dated to the reign of Seti I/Rameses II (Foucart 1935; Menéndez and Vivas Sainz 2023, PM I.1, p. 33, (4), I) which is remarkable for its originality. In fact, the scene was copied by Robert Hay in the nineteenth century,4 providing us with its best state of preservation (Foucart 1935, pl. XIII). Later, Nina Davies made tracings of the tomb in 1909,5 as well as some drawings after the request of Gardiner, which compared the state of the scenes with the drawings by Hay, one of which was a wrestling scene.6 The scene was also copied by Marcelle Baud and included in the publication of TT 19 (Foucart 1935, pl. XV).

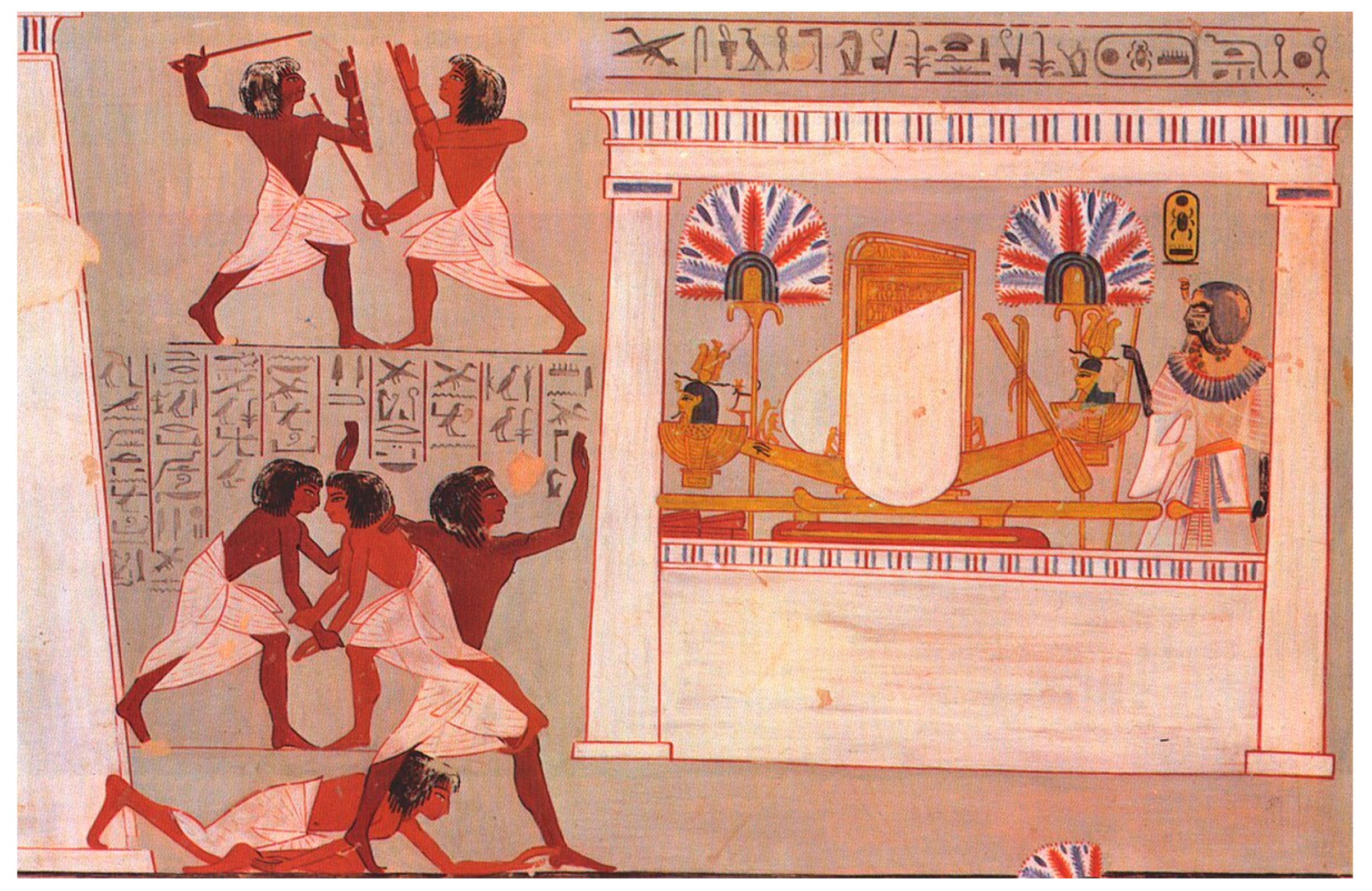

The most complete source of information for this scene comes from the coloured drawing made by Wilkinson (after the Metropolitan Museum Graphic Expedition from 1930–31), which depicts in detail most of the southwest wall (Figure 7). Wilkinson’s drawing (Metropolitan Museum of Art collection, Accession Number: 32.6.1) shows a group of fencers and wrestlers performing their activities in an open area between two pylons in a temple, in particular in the second court of the mortuary temple of Thutmose III.

Figure 7.

Detail of the scene on the southwest wall, TT 19, tomb of Amenmose, XIX Dynasty. Facsimile from the MET collection (Accession Number: 31.6.5). Wikimedia Commons.

The composition is located on the upper register and arranged in two sub-registers, one showing a pair of stick fighters and the other two pairs of wrestlers. These games of fencing and wrestling took place during the festival of Amenhotep I (Piccione 1999, p. 344). The lower sub-register shows an original scene with four men fighting: one pair is wrestling in close body contact grabbing each other, while the other pair seems to show the supremacy of one of the fighters (one man is raising both arms in a victorious attitude, while his opponent is laying on the floor). The intensive movement is noteworthy, as well as the overlapping of the two pairs of wrestlers and their twisted poses. Interestingly, the same victorious pose over a fallen opponent is found in the tomb of Merire II at el-Amarna (Davies 1905, pl. 38) within a wrestling scene performed in front of King Akhenaton, seated on his throne celebrating tribute from Nubia with festivities including sport competitions. It seems these games dramatised Egyptian superiority over Nubians, as the wrestling and fencing activities are performed between an Egyptian and a Nubian, maybe depicting several moments of the same fight (Carroll 1988, pp. 123–24).

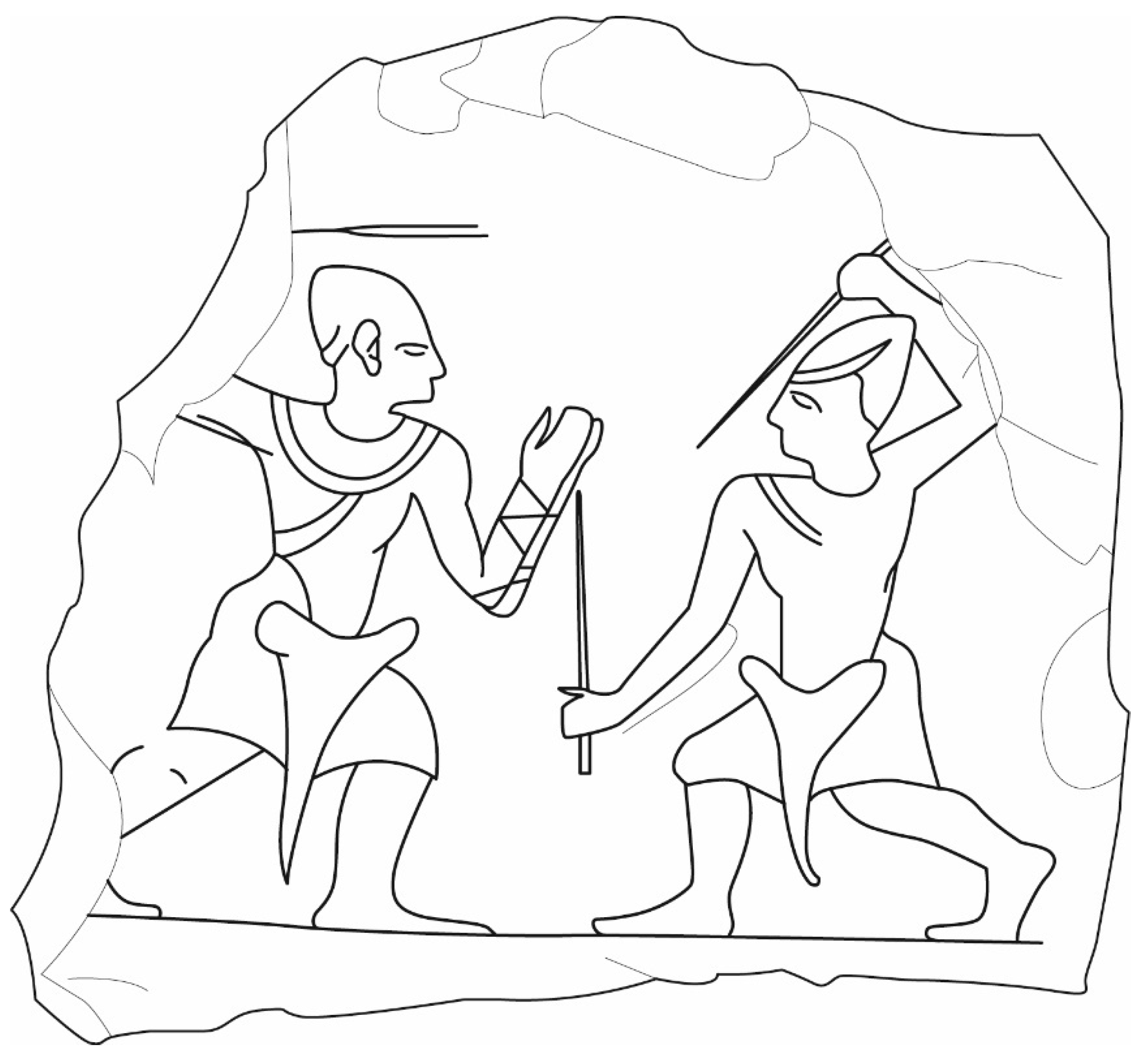

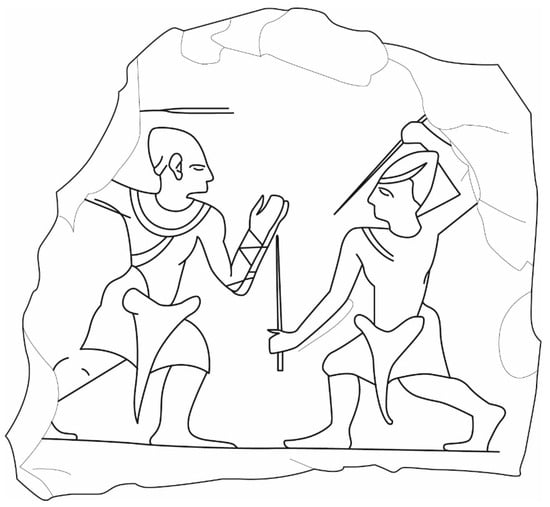

The two fencers with sticks are depicted in TT 19 in the upper sub-register facing each other, holding the weapons with their right hands, a detail that is currently badly damaged (Figure 8). The artists seem to have been precise, including a very rare detail: each wrestler wears short sticks tied with ropes to his left forearm, probably used to protect this area from blows and potential injuries. As far as I know, the only parallel to this rare detail of body protections can be found on a Ramesside ostracon from Deir el Medina (Figure 9) that depicts two soldiers fighting with sticks (Decker and Herb 1994, p. 571, pl. CCCXXII).

Figure 8.

Detail of the scene on the southwest wall. Tomb of Amenmose, TT 19, current state (Photograph courtesy of Gema Menéndez).

Figure 9.

Wrestling scenes on an ostracon, private collection. (Decker and Herb 1994, pl. CCCXXII, M 11). Drawing made by Gema Menéndez.

To my knowledge, there is no similar scene to the one observed in TT 19 in any other Theban tomb, which reveals that the particular attention to detail expressed by the artists working on this tomb-chapel is remarkable. It is also worth mentioning that the scene is located on one of the focal walls of the tomb (the southwest wall, just on the left side when entering) but on the upper register, so that the detail could only have been observed in a standing position (the height of the wall being circa 180 cm).

The presence of this unusual scene of stick dancing located in TT 19, replete with twisted poses and rare details, may have been used as a ‘visual hook’ to catch the attention of the beholder and highlight the depiction of competitions within the second court of the mortuary temple of Thutmose III for the festival of the deified Amenhotep I. Moreover, the depiction of this appealing composition may have been a way to reinforce the importance of the festival by guiding potential viewers to this original detail. Again, the detailed and rather realistic character of this rare scene is noteworthy (a feature common to the rest of the unusual elements within the scope of this paper), and it could even be argued that the artists responsible for the tomb decoration may have seen this kind of activity performed during festivals and on special occasions.

4. Visual Reception of New Iconographic Elements: An Experimental Approach

Even for modern visitors to Egyptian tombs, the contemplation of funerary paintings and reliefs can be an extraordinary experience. In the same way, such reception makes us feel closer to the people who lived in Egypt during the second millennium B.C and stared at those artworks too. But we tend to forget how different the experience must have been. Nowadays, Theban private tomb-chapels are usually artificially illuminated, meaning the perception of the decoration is quite different from ancient times. Ancient visitors may have entered those monuments carrying oil-lamps, which improved the natural light in the tomb but also created specific lighting conditions. A few studies have tried to recreate the atmosphere of the painters and sculptors working in a tomb, such as the experimental research developed by the Belgian mission (Tavier 2012, p. 211), but this point of view has not often been considered when thinking about the beholders. The recent research conducted by Megan Strong shows the potential of experimental archaeology, for instance, when dealing with the perception of colour in different types of light conditions: “the light from lamps or hand-held lighting devices would have flickered, moved, and interacted with the carved and/or painted surfaces of the wall. They would have created shadows and varying levels of darkness, only illuminating small portions of a tomb at a time. This not only would have impacted upon the viewer’s experience of a space or an object as a whole, but on their perception of colors, as well” (Strong 2018, p. 178). Her interesting study suggests “that the layering of yellow ochre and orpiment on surfaces which would have been lit by artificial lighting, may have been a conscious choice by the ancient Egyptian artist in order to enhance the visual perception of a piece” (Strong 2018, p. 181).

Ancient visits to private tombs are recorded in textual sources, for instance graffiti clearly demonstrating that some monuments were a focus of attention (Ragazzoli 2013). Recent studies have even proved the importance of the location of graffiti and their role as evidence of human reactions to images (Den Doncker 2012). Theban tombs were visited throughout the year by relatives and friends as part of the funerary cult devoted to the deceased, but more specifically during festivals such as the Festival of the Valley and the New Year’s Festival. During both festivals, a banquet was performed by the family, which was even depicted in the decoration of the tomb-chapels themselves (Fukaya 2019, p. 4). On these occasions, including both ordinary funerary cult activities and festivals, tombs were gathering places where people congregated in the courtyards and the transverse halls of the tombs. During their stay in the tomb-chapels, visitors must have stood or sat on the floor to perform cultic activities, talk, or rest (or even eat). For instance, the banquets that took place in the Theban tombs during the Festival of the Valley involved people seated, and each tomb was perhaps furnished with mats, chairs, and tables for temporary use. Leading family members were probably invited into the tomb and sat there at a banquet (as the scene in TT 56 shows), while others remained outside, as it would have been rather natural to spread stools in the courtyard or in a close open-air area outside a tomb in order to accommodate more attendees (Fukaya 2019, p. 74). Therefore, the line of sight and human perception of the scenes in a given tomb-chapel must have been completely different when standing or sitting, a factor that may have been taken into account by Egyptian artists when organizing the distribution of scenes. Besides, many graffiti made on Egyptian monuments suggest a seated position of the author thereof, because such informal texts or pictures could have been made in varied circumstances (Navratilova 2017, p. 649, Figure 1). Having these issues in mind, my approach will deal with the contemplation of some Theban tombs when standing or seating, trying to recreate the perception in ancient times.

Brief experimental research was conducted in situ in December 2023 within the Theban necropolis, focusing on TT 57, TT 56, and TT 69 (monuments open to the public), and especially the walls containing the innovative iconographic elements analysed in the preceding pages. Some caveats from this experimental research need to be mentioned here. The person developing the field research is 161 cm high (5 ft 3 in) and was wearing flat boots. The average height of the population in ancient Egypt is difficult to establish, but several studies could be mentioned. According to Zakrzewski, the average stature was 157.5 cm (or 5 ft 2 in) for women and 167.9 cm (or 5 ft 6 in) for men, being the heights slightly lower than today’s population (Zakrzewski 2003). Analysis based on the human remains from el-Amarna show similar data: adult females were 154.02 cm (5 ft 0.5 in) on average, while males were 163.75 cm (5 ft 4.5 in) (Kemp et al. 2013, p. 71).

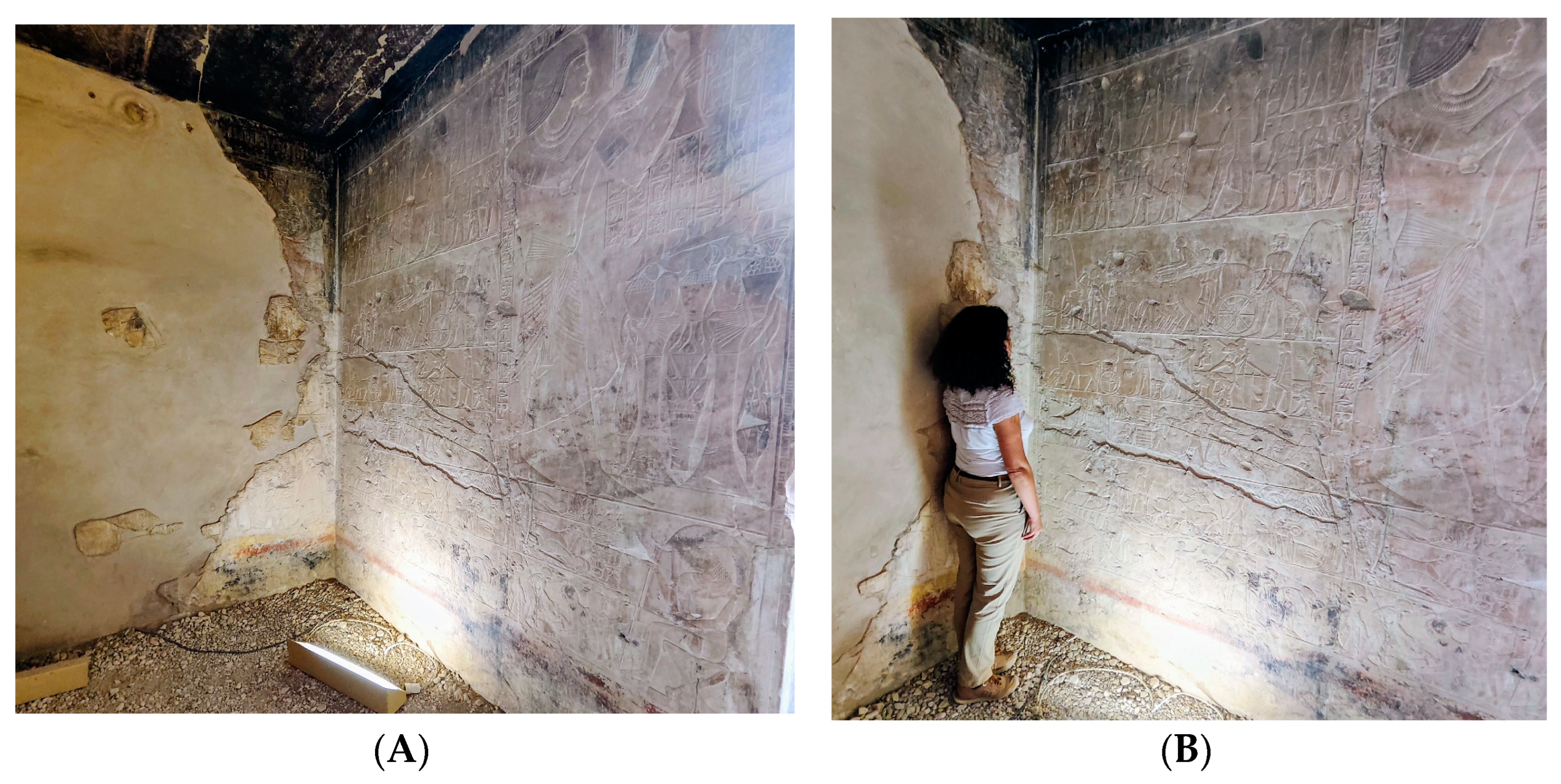

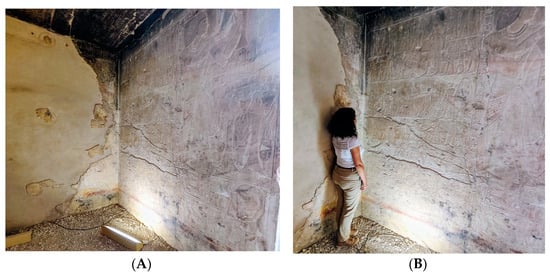

The tomb of Khaemhat provides two unusual details recorded in the same register of the east wall in the transverse hall (fourth register from bottom to top, the total height of the wall being 280 cm approximately), which is 121 cm high from the floor level, at eye level for a standing person (Figure 10). The transverse hall of TT 57 is a rather narrow space (170 cm wide), similar to contemporary Theban tombs.

Figure 10.

Tomb of Khaemhat, TT 57. Transverse hall. (A). General view of east wall. (B). General view of east wall with a person standing. (Photographs by the author).

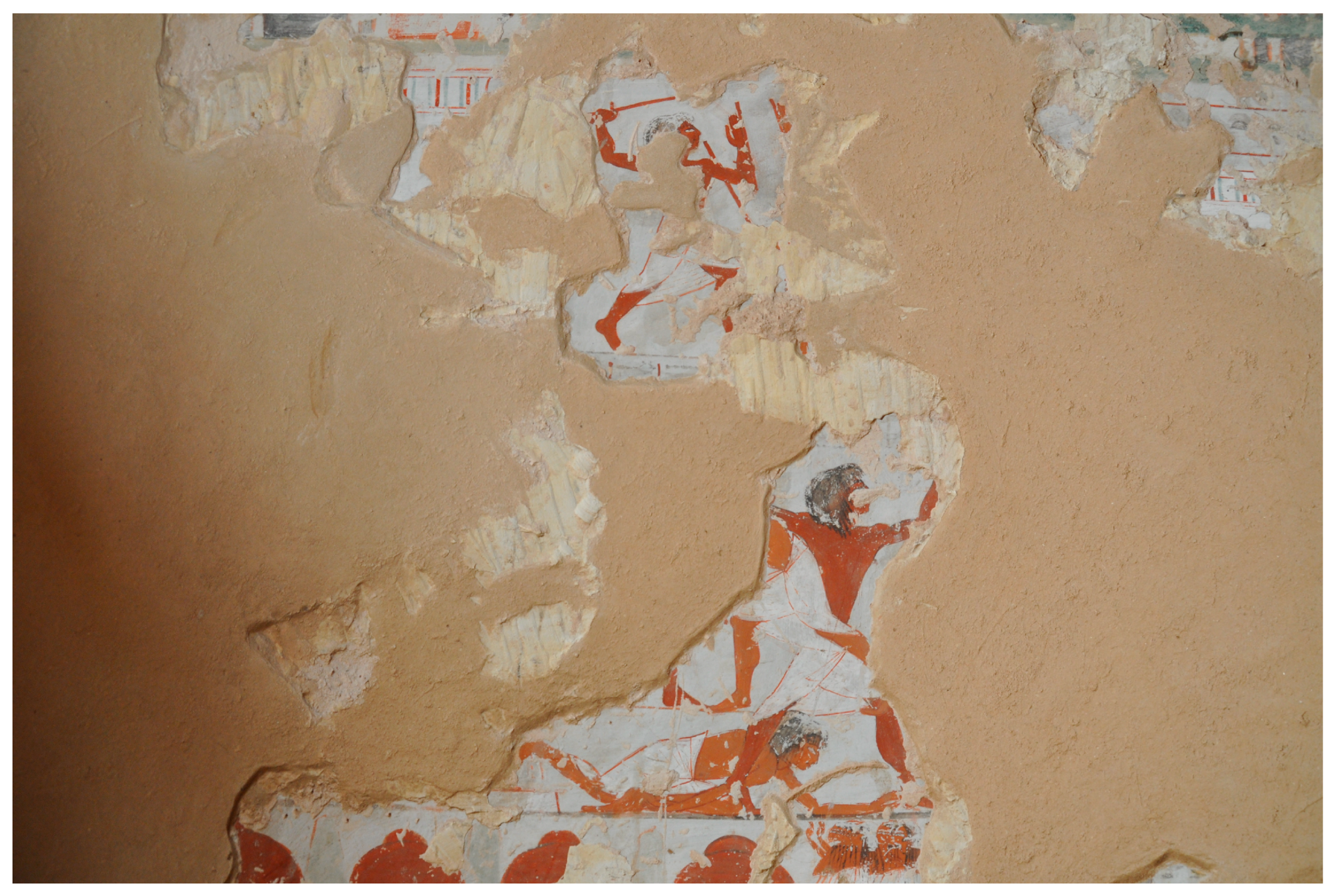

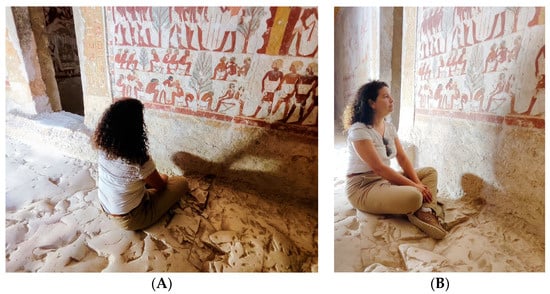

However, ancient Egyptian private tombs were gathering places where people could meet and sit down. The eye level logically changes completely with a seated pose, as inferred from the experimental research developed in TT 56 and TT 69. For instance, a seated individual could easily focus their attention on the unusual icon located on the south wall of the transverse hall of TT 56 (Figure 11), which is a narrow space (199 cm wide). The total height of the south wall is 258 cm high, and the image of a sleeping man under a tree is located in the first register (from bottom to top).

Figure 11.

Tomb of Userhat, TT 56. Contemplation of the scene in south wall with the rare detail, while seated: (A). back view of the beholder, (B). side view. (Photographs by the author).

The detail of a sleeping man located in TT 69 is found in the transverse hall (Broad Hall Left), in a rather narrow hall 189 cm wide. The total height of the wall is approximately 215 cm, and the new iconographic detail is located on the second register (from bottom to top), exactly 93 cm above the floor level. This rare detail is clearly not at eye level but could be easily viewed when the individual was seated (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Tomb of Menna, TT 69. Contemplation of the scene (in the Broad Hall Near Left) with new icon, while seated on the floor. (Photograph by the author).

Several preliminary conclusions may be drawn from this brief experimental study. The innovative details analysed in this research could be observed at eye level not only from a standing position but also while seated. It seems ancient Egyptian artists considered how the scenes in private tomb-chapels could be viewed from different perspectives and kept in mind that tombs were gathering places, especially on festive occasions. The transverse hall of tomb-chapels has been considered part of the public space of such monuments and a logical area for gathering, where people could sit, perform cultic activities, and rest, enjoying the scenes. Moreover, the rare poses and original details located on the lower registers of the walls reflect a relaxed attitude (i.e., men sleeping), maybe mimicking the relaxed poses of the beholders. Among these beholders, it seems reasonable to include artists who visited tomb-chapels during their construction and decoration, or afterwards, perhaps looking for innovative details to inspire themselves. If fact, the phenomenon of emulation of some of these new details points out that there were active and enthusiastic beholders of tomb scenes.

5. Conclusions

The originality and individuality of ancient Egyptian artists is a complex and controversial topic, which has been addressed recently in order to upset the traditional view of those artists as mere artisans developing a repetitive work deprived of creativity (Laboury 2013). Recent studies have reclaimed the importance of painters’ artistic freedom, which manifests itself in many ways, remarking that artistic changes were constantly happening in ancient Egypt and were most often the results of conscious agency and a will to experiment (Sartori 2023, p. 500). Valerie Angenot has analysed the transgression of the usual system of registers, pointing out that examples multiplied during the New Kingdom, when baselines, registers, or squares were amusedly transgressed by Egyptian artists, being often the symptoms of good artistic and social health, as is often the case when recreation mixes with creation (Angenot 2010, p. 41).

The subject of innovation could benefit from more specific studies focused on artistic resources employed to create innovative compositions, rather than reinterpreting the symbolism of the scenes or their historical value (and of course, it is relevant to examine the social, religious, and cultural circumstances of artists and patrons). In his suggestive paper published in 1991, Roland Tefnin remarked upon the convenience of studying innovation in ancient art, “la part de l’innovation, de la créativité pure des imagiers, leur capacité àu inventer formulations inédites pour d’anciennes idées iconographiques, ou pour de nouvelles. C’est á ce niveau sans doute que s’ouvre l’espace des choix véritablement artistiques et que la dimension poétique des codes stylistique et iconographique prend toute sa valeur…et sa saveur!” (Tefnin 1991, p. 72). The humble aim of this paper has been to explain the presence of original and rare details that might be understood as ‘tokens’ of the originality of the artists. These new iconographic elements were emulated in other compositions, but they are not exact copies. It is necessary to underscore that the act of creating a new tomb decoration necessarily implied a stimulus for the creativity and originality of the artists. Those artists produced, either consciously or unconsciously or both, new tokens with unusual details, which were imitated by their workmates during and after their creation. Furthermore, the emulation of new details may reflect the circulation of people within the Theban area, as well as the possible involvement of certain artists or schools of painters in several decorative programs at the same time.

When analysing the idea of creativity of human beings, two main streams should be considered. On one hand, the stream which considers that every aspect of the human mind (including artistic talent) is conditioned by the social and material environment, following the ideas of so-called Dialectical Materialism7 (Elias 1991; Gramsci 2007). On the other hand, another stream argues that aspects related to human talents (such as creativity) are essentially linked to our own human nature, that is, to phylogenetic aspects. It is relevant to point out that neither of these streams can fully explain the fact of artistic creativity. In the particular case of ancient Egypt, it if difficult to explain why an artist created an unexpected element, which could be exemplified in the original details analysed in the present research. For instance, the inclusion of the rare pose of the girl in the banquet scene in TT 100 might be a response by the artist to create a discordant element. Or maybe not. From my point of view, such a detail could be the result of an impulse, perhaps uncontrolled, a phenomenon that is inherent to the condition of the artists themselves: the creative impulse.

The ‘invention’ of new elements is an intrinsic phenomenon of the creative process, especially intense in the work of certain artists: the process of creation implies searching for new details. Artists who introduced innovations and changes could reasonably be considered distinguished among their colleagues, and they were thus emulated. Ancient Egyptian artists seemed to compete to obtain the aesthetic pleasure of the beholders, as well as their own pleasure, avoiding mere copies of previous scenes and reinterpreting them each time, following the creative impulse. It may be argued that the new details analysed in this paper may have been used by painters and sculptors just to amuse themselves and/or to amuse the beholders of the tomb decoration (whatever their status), but it seems that these elements are instead a sign of the innovative character of their creators. Although we do not have specific data about the reactions of the beholders of these new iconographic elements analysed in the present research (the deceased relatives, friends, or people linked to the funerary cult), it is unquestionable that other artists admired them. The evidence of emulation of new specific details found in Theban tombs indicates that the Egyptian artists observed and recreated them in other scenes, a relevant phenomenon in Thebes (especially having in mind the close geographical position of tombs with similar rare details). In fact, the emulation of details seems to have been rather based on visual memory, as there was no physical support for the copying of scenes aside from sketches on ostraca. Besides, the process of emulating new elements may suggest the importance of emotions experienced by artists contemplating the original elements produced by colleagues, which would stimulate them in the emergence of further innovative details. In some sense, creativity is a contagious phenomenon.

The use of unusual details which may have worked as ‘visual hooks’ in funerary Egyptian art is not exclusive to the Theban necropolis and can be traced in other periods and areas. The research conducted by Gabrielle Pieke in late Old Kingdom chapels from the Memphite region has demonstrated the circulation of motifs, for instance, in the representations of the very rare motif of the tomb owner painting, found in the tombs of Mereruka, Khentica, and Ms (Pieke 2017, p. 275, Figure 16). Furthermore, this phenomenon seems to have resurged also in the New Kingdom Memphite cemetery, even showing the circulation of certain motifs to other areas such as el-Amarna (Staring 2021).

The process of innovation, intrinsic in artistic work, is exemplified in new details, later emulated. As Laboury suggested, “exceptional details, just like more usual or traditional motifs, occur from one monument to another, creating a reticular structure of cross-references. All together, these picture units form a—virtual—common iconographical thesaurus, which is never attested as a whole, nor closed to modifications and additions. On the contrary, it is systematically reinterpreted by each artist, who makes his own selection within this open range of possibilities and gives his personal interpretation of it. And, hence, it is clearly within this process of re-composition, or formal interpretation of a corpus inherited from the tradition(s), that the artist’s creativity operates and is therefore to be sought and analysed” (Laboury 2017, p. 238).

The idea of discordant elements that introduce a somehow different rhythm is also relevant to many of the scenes analysed, because unusual details break the rather repetitive figures rendered in a composition, as in the agriculture scene in TT 69 or in the inspection of troops in TT 56. In other words, the creative dynamic might have resulted in the appearance of rare elements, for instance, within the context of traditional representations of rows of elite members banqueting (i.e., TT 100), or within the agriculture scenes depicted in most of the Theban tombs from the 18th Dynasty (i.e., TT 69).

Furthermore, the location of original elements is an outstanding aspect. First, they are found on secondary characters within the tomb scenes (assistants, soldiers, peasants, etc.), in the context of all the options left up to the artists (probably out of the sphere of the suggestions and requirements of the tomb owner). The details are mostly located in the transverse hall, the most public area of the tomb-chapels, which contain the most important scenes. As Nicola Harrington has recently proposed, artists used specific colours (i.e., yellow, with a clear solar connection) to enhance the importance of certain scenes, as well as placing coloured paint and detailed hieroglyphs for the name and titles of the tomb owners and their wives in specific scenes that contrast with the monochromatic schemes in the rest of the scenes (Harrington 2015, p. 147). In addition, other outstanding iconographic elements, such as the kiosk with the image of the king, are also usually given a yellow background, probably to emphasize the close relationship of the deceased with the monarchy, thus emphasizing his status in the eyes of visitors, as well as indicating sacred space (Harrington 2015, p. 147). Rare poses or unusual details may have been used by artists in a similar fashion to highlight some scenes, maybe guiding the audience and enhancing the experience of the memorial monuments. Furthermore, the experimental approach developed in situ using a few Theban tombs suggests that artists understood that tomb scenes could be viewed from different perspectives, standing or seated. This approach could enrich our understanding of the visual perception of funerary decoration by ancient Egyptians, considering the different cultic activities performed in the tomb-chapels and the poses of the beholders involved.

Not only colour was used to enhance certain areas in the composition: Hugues Tavier and Alexis Den Doncker’s research has demonstrated that the use of varnish had an aesthetic function, being specifically located in motifs that usually illustrate the high social status and prestige of the tomb owner and his family: skin complexion, hair/wigs, clothes, jewellery but also objects like gifts, funerary equipment, and offerings. However, in some cases, almost every figure within the iconographic programme, as well as other decorative features, were varnished, suggesting the aesthetic quality of the whole chapel decoration (Den Doncker and Tavier 2018, p. 17). Besides, they have noted a significant development in the way painters apparently sought to depict olfactory realities (for instance, scented ointments, perfumes, unguents, or balsams), suggesting the physical materialisation of scents (certain varnishes such as pine resins) applied onto certain motifs appeared to the painters as a practical solution to the issue of their iconographic representation (Den Doncker and Tavier 2018, pp. 18–19).

The style of the unusual iconographic elements is, on some occasions, particularly characteristic for its attention to human attitudes and details, as revealed by the relaxed poses within the frame of daily-life situations (as with the sleeping men under a tree attested in TT 56, TT 57, and TT 69, or on a chariot in TT 57 and the BM fragment). The date of the first appearance of several of these new daily-life iconographic elements seems to occur sometime between the reigns of Amenhotep II and Amenhotep III, depicting situations which may be considered ‘spontaneous’ attitudes but are rather the result of a focus on the individuals and their behaviours (maybe included by the artist to reflect human situations that could engage the beholder), and perhaps related to the emergence of the characteristic Amarna style. That is, they may be considered precedents of the new way of rendering daily-life scenes of the Amarna art attested in many talatat scenes, (for instance, representing people holding a conversation). The emergence of the new way of representing human behaviour created during the Amarna era may not have been a sudden process, but rather a feature that germinated in the mid-18th Dynasty and evolved during a few generations of artists. The mid-18th Dynasty funerary decoration developed in Thebes is remarkable for the high quality and their innovative character, as the research by Melinda Hartwig focused on the painted tomb chapels dated from the reign to Thutmose IV to Amenhotep III has demonstrated (Hartwig 2004). Some of the examples of new iconographic elements analysed in this research correspond roughly with that period and may be understood as evidence of the creativity and individuality of painters in this productive Theban mileau, who started to depict traditional scenes paying attention to daily-life situations and human behaviour. As has already been proved, the Amarna style did not disappear completely after the abandonment of Akhetaten but is still traceable in the early Ramesside period style in the presence of certain attitudes or specific details. The spread of styles or details could be related to the mobility of the artistic workforce (El-Shahawy 2012), especially relevant during the Amarna era and afterwards. Indeed, the case study from TT 19 analysed in the present paper, with the unusual scene of fencing and wrestling, recalls the spontaneous scene from the tomb of Meryre II at el-Amarna with a strikingly similar composition.

The artistic relationship between Memphis and el-Amarna in the late 18th Dynasty has been demonstrated by Nico Staring in his substantial work recently published, suggesting that it is quite likely that a selection of the skilled workforce moved north after the abandonment of Akhetaten (Staring 2021, p. 30). Therefore, the mobility of the population is also traceable in iconographic sources: “With the (temporary) move of the capital to Amarna, iconographic traditions travelled along with the relocating population. Iconographic motifs that had originated from Memphis blended with traditions from elsewhere, including from Thebes, and when people moved back from Amarna to their towns of origin, such as Memphis, new ideas hopped along with them, bringing about a continuity of artistic traditions that had changed along the way” (Staring 2021, p. 62).

The question of the intentionality of the new iconographic details analysed in this research is, indeed, a difficult topic. From my point of view, artists may have included these elements in order to engage the beholder, trying to guide his/her gaze to certain areas in the composition or to engage him/her in a more time-taking contemplation of the scenes. Besides, the daily-life character of some of these rare details is noteworthy, which might create a specific connection with the beholder. By showing everyday situations that unexpectedly occur in real life (i.e., a man sleeping under a tree), the artist escaped from the traditional representation of the scenes and created a somehow realistic situation focusing on individuals and their behaviours, which may have caught the attention of the beholder. Artists were constantly reinterpreting the traditional repertoire, as it has been recently remarked: “In Ancient Egyptian Art, as well as in any other kinds of art, creativity is the art of engaging, dealing and—in the end—playing with the tradition(s)” (Laboury 2017, p. 254).

Art and power are intrinsically joined through the whole History of Art. Through the paintings and reliefs which decorated their funerary monuments, Egyptian elite members transmitted their religious ideas, together with their achievements, showing their desire to receive a posthumous cult and perpetuate their memories. Thus, the power of images, especially important in a mainly illiterate society, was unquestionable. The artistic resources could have been employed by artists to draw the attention of the beholders (to rare poses or unusual details without a relevant symbolic meaning), creating a remarkable tool of attractive art that consequently enhanced visits to the tomb-chapel and even manufactured the popularity of certain places. But aside from its usefulness within the funerary realm, the presence of original details reflects the innate creativity of those artists to seek out stimulating scenes, which thus sometimes provoked emulation by contemporaries and later workmates (as has been demonstrated in this paper). In this sense, creativity must be understood as a dynamic of the visual arts that determined the constant evolution and innovation of styles. Therefore, the role of ancient Egyptian artists (particularly the so-called ‘scribes of contours’) can be considered an outstanding source of information about the transmission and emulation of new ideas and iconographic elements, as well as the evolution of styles. In other words, Egyptian artists continue to shape our knowledge of ancient Egypt.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Gema Menéndez and Antonio Muñoz, among other helpful colleagues, for their valuable suggestions on the draft version of this paper. I would like to thank Antonio Gómez Laguna and Juan Candelas Fisac for their assistance in the brief experimental research conducted on the Theban tombs.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Beauty is a difficult concept to be defined, but is first and foremost a philosophical idea. For most of its history, the idea of beauty has been discussed without any detailed understanding of human biology or psychology, but neurobiological researches have recenly tried to give a new approach: For instance, it seems that beauty responses appear to involve the activation of pleasure signals that are common to other forms of hedonic valuation. As it has been recently suggested, beauty is not uniquely human: “findings from psychological, neuroscientific, and biological research suggest that beauty should be conceived as a form of basic hedonic valuation (that humans share with other animals): only sensory objects that elicit hedonic pleasure are experienced as beautiful. Hedonic valuation, responds to similar features, such as fluency, symmetry, and complexity, and it is modulated by similar factors, such as time, social imitation, and available alternatives. Besides, it seems that beauty has a substantial impact on affect, behavior, and choices” (Skov and Nadal 2021, pp. 51–52). |

| 2 | In this sense, aesthetic could be understood as a particular taste for or approach to what is pleasing to the senses and especially sight. |

| 3 | University Museum of Philadelphia photos 34916 and 34918 (mentioned in Porter and Moss 1960) do not show the charioteers, maybe due to a wrong citation of the photos belonging to TT 302. |

| 4 | British Library MSS 29812-60. |

| 5 | Davies MSS. 10.8.1-2. |

| 6 | Gardiner MSS AHG/20.2; PM I (2), 33 (4). |

| 7 | Dialectical materialism is a philosophical approach to reality, developed from the theories and writings of Karl Marz and Friedriech Engels (who partly followed the ideas of the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel). For them, materialism meant that the material world, perceptible to the senses, has objective reality independent of mind or spirit. Furthermore, dialectical materialism does not deny the reality of mental or spiritual processes but affirms that ideas could arise only as products and reflections of material conditions. |

References

- Andreu, Guillemette. 2002. Les Artistes de Pharaon: Deir el-Médineh et la Vallée des Rois. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Andreu-Lanoë, Guillemette. 2013. Introduction. In L’art du Contour: Le Dessin dans l’Égypte Ancienne. Edited by Guillemette Andreu-Lanoë. Paris: Musée du Louvre, pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Angenot, Valerie. 1996. Lire la paroi. Les vectorialités dans l’imagerie des tombes privées de l’Ancien Empire Égyptien. Annales d’Histoire de l’Art et d’Archéologie XVIII: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Angenot, Valerie. 2010. Cadre et organisation de l’espace figuratif dans l’Égypte ancienne. In Cadre, Seuil, Limite. La Question de la Frontière dans la Théorie de l’art. Edited by Thierry Lenain and Rudy Steinmetz. Brussels: La Lettre Volée, pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Arnheim, Rudolf. 1995. Arte y Percepción Visual. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 1985. Color Terminology and Color Classification: Ancient Egyptian Color Terminology and Polychromy. American Anthropologist 87: 282–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinlich-Seeber, Christine, and Abd el-Ghaffar Shedid. 1987. Das Grab des Userhat (TT 56). Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Brack, Annelies, and Artur Brack. 1977. Das Grab des Tjanuni-Theban Nr. 74. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen 19. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Betsy. 2001. Painting Techniques and Artisan Organization in the Tomb of Suemniwet, Theban Tomb 92. In Colour and Painting in Ancient Egypt. Edited by William Vivian Davies. London: British Museum Press, pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Scott. 1988. Wrestling in Ancient Nubia. Journal of Sport History 15: 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1905. The Rock Tombs of El Amarnah, II. Archaeological Survey of Egypt 14. London: Egypt Exploration. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1917. The Tomb of Nakht at Thebes. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Arts Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1935. Paintings from the Tomb of Rekh-mi-Re’ at Thebes. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1943. The Tomb of Rekh-Mi-Rē’ at Thebes. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, Wolfgang, and Michael Herb. 1994. Bildatlas zum Sport im Alten Ägypten. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Den Doncker, Alexis. 2012. Theban Tomb Graffiti during the New Kingdom. Research on the Reception of Ancient Egyptian Images by Ancient Egyptians. In Art and Society. Ancient and Modern Contexts of Egyptian Art. Proceedings of the International Conference held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 13–15 May 2010. Edited by Katalin Anna Kothay. Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Den Doncker, Alexis. 2017. Identifying-copies in the Private Theban Necropolis. Tradition as Reception under the Influence of Self-fashioning Processes. In (Re)productive Traditions in Ancient Egypt. Proceedings of the Conference Held at the University of Liège, 6–8 February 2013. Ægyptiaca Leodiensia 10. Edited by Todd Gillen. Liege: Presses Universitaires de Liège, pp. 333–70. [Google Scholar]

- Den Doncker, Alexis. 2022. Visual Indexicality in the Private Tomb Chapels of the Theban Necropolis: On Flipping Iconographic Units as a Compositional Tool. Prague Egyptological Studies 29: 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Den Doncker, Alexis, and Hugues Tavier. 2018. Scented resins for scented figures. Egyptian Archaeology 53: 16–10. [Google Scholar]

- Devillers, Alisée. 2018. The Artistic Copying Network around the tomb of Pahery in Elkab. In The Arts of Making in Ancient Egypt. Edited by Gianluca Miniaci, Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Stephen Quirke and Andreas Stauder. Leiden: Brill, pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Devillers, Alisée. 2021. La représentation figurative des praticiens de la Hmw.t./Pour une approche iconographique des artistes de l’Égypte antique. Ph.D. thesis, University of Liège, Liége, Belgium. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Devillers, Alisée. 2023. Un art sans artiste… vraiment ? Pour une approche iconographique: Les (auto)représentations des praticiens de la Hmw.t. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Congress of Egyptologists (ICE XII). 3rd–8th November 2019. Edited by Ola El-Aguizy and Burt Kasparian. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, vol. I, pp. 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Devillers, Alisée, and Toon Sykora. 2023. Enhancing Visibility—Djehutihotep’s painter Horameniankhu. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, pp. 53–81. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, Norbert. 1991. The Symbol Theory. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shahawy, Abeer. 2010. Recherches sur le décoration de les tombes Thébaines du Nouvel Empire. London: Golden House. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shahawy, Abeer. 2012. Thebes-Memphis: An interaction of iconographic ideas. In Ancient Memphis. ‘Enduring Is the Perfection’. Orientalia Lovaniensa Analecta 214. Edited by Linda Evans. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 133–45. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann-von Carnap, Barbara. 1999. Die Struktur des Thebanischen Friedhofs in der Ersten Halfte der 18. Dynastie. Analyse von Position, Grundrissgestaltung und Bildprogramm der Graber. ADAIK 15. Berlin: Achet. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzenreiter, Martin. 1995. Totenverehrung und soziale Repräsentation im thebanischen Beamtengrab der 18. Dynastie. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 22: 95–130. [Google Scholar]

- Foucart, Georges. 1935. Tombes Thébaines. Nécropole de Drâ Abû’n-Nága. Le tombeau d’Amonmos. Memoires l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale du Caire 57. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Fukaya, Masashi. 2019. The Festivals of Opet, the Valley, and the New Year Their Socio-Religious Functions. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Gramsci, Antonio. 2007. Prison Notebooks 3. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, Nicola. 2015. Creating visual boundaries between the ‘sacred’ and ‘secular’ in New Kingdom Egypt. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 30: 143–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Melinda. 2004. Tomb Painting and Identity in Ancient Thebes, 1419–1372 BCE. Turnhout: Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth—Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Melinda. 2013. The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT 69). The Art, Culture and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. ARCE Conservation Series 5; Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga, Johan. 2007. Homo Ludens. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein Ali Attia, Amani. 2022. Tomb of Kha-em-Hat of the Eighteenth Dynasty in Western Thebes (TT 57). Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Wolfgang. 1998. The Work of Art and Its Beholder. The Methodology of the Aesthetic of Reception. In The Subject of Art History: Historical Objects in Contemporary Perspectives. Edited by Mark A. Cheetham and Keith P. Moxey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 180–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Barry, Anna Stevens, Gretchen R. Dabbs, Melissa Zabecki, and Jerome C. Rose. 2013. Life, death and beyond in Akhenaten’s Egypt: Excavating the South Tombs Cemetery at Amarna. Antiquity 87: 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2013. De l’individualité de l’artiste dans l’art égyptien. In L’art du contour. Le dessin dans l’Egypte ancienne. Edited by Guillemette Andreu-Lanoë. Paris: Musée du Louvre éditions, pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2017. Tradition and Creativity. Toward a Study of Intericonicity in Ancient Egyptian Art. In (Re)productive Traditions in Ancient Egypt. Proceedings of the Conference Held at the University of Liège, 6–8 February 2013. Agyptiaca Leodiensia 10. Edited by Todd Gillen. Liege: Presses Universitaires de Liege, pp. 229–58. [Google Scholar]

- Manniche, Lise. 1988. Lost Tombs: A Study of Certain Eighteenth Dynasty Monuments in the Theban Necropolis. London: Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Geoffrey Thorndike. 1989. The Memphite Tomb of Horemheb, Commander-in-chief of Tut’ankhamûn. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez, Gema, and Inmaculada Vivas Sainz. 2023. La tumba de Amenmose e Iuy en Dra Abu el-Naga (TT 19). Nuevo proyecto y una propuesta de estudio artístico. Revista del Instituto de Historia Antigua Oriental 24: 114–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Herrera, Antonio. 2023. Architectural Landscape. A New Interpretation of the Sloping Ceiling of Rekhmire’s Tomb Chapel (TT 100). Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie VII, Historia del Arte 11: 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navratilova, Hanna. 2017. Miscellanea graffitica. In Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2015. Edited by Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens and Jaromír Krejcí. Prague: Faculty of Arts, Charles University Prague, pp. 649–73. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, Richard. 2008. The Painted Tomb-Chapel of Nebamun. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piccione, Peter. 1999. Sportive fencing as a ritual for destroying the enemies of Horus. In Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilizations 58. Edited by Emily Teeter and John Larson. Chicago: The Oriental Institute, pp. 335–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pieke, Gabrielle. 2017. Lost in transformation. Artistic creation between permanence and change. In (Re)productive Traditions in Ancient Egypt. Edited by Todd Gillen. Liège: Presses Universitaires de Liège, pp. 259–304. [Google Scholar]

- Pieke, Gabrielle. 2022. Remembering forward. On the Transmission of Pictorial Representations in Tomb Decoration up to the New Kingdom. In Perspectives on Lived Religion II. The Making of Cultural Geography. Edited by Lara Weiss, Nico Staring and Huw Twiston Davies. Leiden: Sidestone press, pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Bertha, and Rosalind Moss. 1960. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings I: The Theban Necropolis, Part 1, Private Tombs. Oxford: Griffith Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ragai, Jehane. 1986. Colour: Its significance and production in Ancient Egypt. Endeavour 10: 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazzoli, Chloé. 2013. The social creation of a scribal place: The visitors’ inscriptions in the tomb attributed to Antefiqer (TT 60), with newly recorded graffiti. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 42: 269–323. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, Gay. 2016. Constructing elite group and individual identity within the canon of 18th Dynasty Theban tomb chapel decoration. In Problems of Canonicity and Identity Formation in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Edited by Kim Ryholt and Gojko Barjamovic. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, pp. 201–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, Marina. 2023. Between Freedom and Formality The Visuality of New Kingdom Theban Tombs. In ICE XII. Proceedings of the Twelfth International Congress of Egyptologists, 3rd—8th November 2019, Cairo. Bibliothèque générale 71. Edited by Ola el-Aguizy and Burt Kasparian. Cairo: IFAO, pp. 909–50. [Google Scholar]

- Skov, Martin, and Marcos Nadal. 2021. The nature of beauty: Behavior, cognition, and Neurobiology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1488: 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staring, Nico. 2021. The Memphite Necropolis through the Amarna Period: A Study of Private Patronage, Transmission of Iconographic Motifs, and Scene Details. In Continuity, Discontinuity and Change. Perspectives from the New Kingdom to the Roman Era. Edited by Filip Coppens. Prague: Charles University, pp. 13–73. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, Megan E. 2018. Do You See What I See? Aspects of Color Choice and Perception in Ancient Egyptian Painting. Open Archaeology 4: 173–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavier, Hughes. 2012. Pour une approche experimentale de la peinture thebaine. In Art and Society. Ancient and Modern Contexts of Egyptian Art. Proceedings of the International Conference held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 13–15 May 2010. Edited by Katalin Anna Kothay. Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 209–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tefnin, Roland. 1991. Éléments pour une sémiologie de l’image égyptienne. Chronique d’Egypte 66: 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefnin, Roland. 2000. Reflexiones sobre la imagen egipcia antigua: La medida y el juego. In Arte y sociedad del Egipto antiguo. Edited by Miguel Ángel Molinero Polo and Domingo Solá Antequera. Madrid: Editorial Encuentro, pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Valbelle, Dominique, and Jean-François Gout. 2002. Valbelle, Dominique, and Jean-François Gout. 2002. Les Artistes de la Vallée des Rois. Paris: Éditions Hazan. [Google Scholar]

- Volokhine, Youri. 2000. La Frontalité dans l’iconographie de l’Égypte Ancienne. Geneva: Société d’égyptologie. [Google Scholar]