Abstract

Within the fields of aesthetics and psychology, there is a long tradition of arguing that affect precedes cognition. A verbalized thought following upon a feeling and associated with it does not translate the feeling precisely or adequately. In fact, as C. S. Peirce would argue, the thought itself projects its own affect, which is independent of its logic. The essence of affect or feeling will always elude linguistic capture. This essay argues that experiences of belief and doubt are affective sensations, and both can be graphed on a scale of sensuous intuition or cognitive guessing (which, again, projects affect). The failure of language to grasp what we refer to as instances of emotion, feeling, sensation, affect, belief, doubt, and the like is more of an intractable problem for philosophical aesthetics than it is for the aesthetics of the art experience. Examples of the art of Cy Twombly, Barnett Newman, Donald Judd, Bridget Riley, and Katharina Grosse are invoked to argue through the gap between thought and feeling.

Attempts at addressing mute feeling by resorting to verbalization fall wide of the mark or fail utterly. Robert B. Zajonc, a prominent psychologist who focused on affect, ventured a long-shot notion in 1980: “Perhaps we have not developed an extensive and precise verbal representation of feeling just because in the prelinguistic human this realm of experience had an adequate representation in the nonverbal channel.”1 On affect and all aspects of emotion, I presume then that I ought to reawaken my lizard brain for consultation. A degree of access to the experience of feeling comes nevertheless from a lineage of highly evolved philosophical and literary voices—among them, Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, Wilhelm Wundt, Marcel Proust, Samuel Beckett, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Julia Kristeva, and Gilles Deleuze.2 At times, a visual artist who comments on another visual artist—an artist assuming the role of critic—does as well as these specialists in language, since artists are both sensitive to, and practiced in, sensation. They seem able to experience feeling while lingering over its nuances, without slipping into conceptual clichés.3

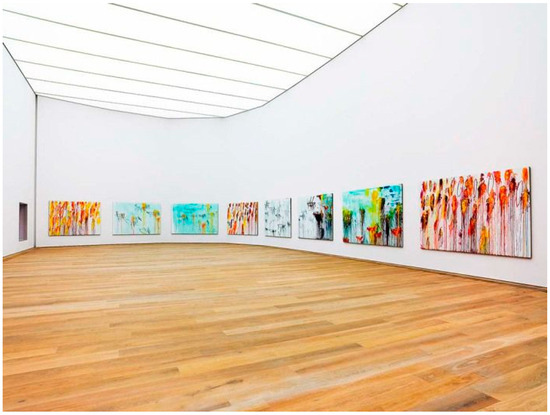

Listen to painter Katharina Grosse as she recalls her emotional response to Cy Twombly’s Lepanto cycle (2001), a set of twelve works located in the Museum Brandhorst, Munich (Figure 1). Her uncritical reaction to the visual sensation of these paintings becomes a piece of art criticism in the telling, necessarily distanced from the initial experience, the nonverbal now rendered verbal by an act of cognitive translation. Engaged with Twombly’s installation, Grosse becomes as energized as she imagines he must have been as he produced it:

Twombly never loses time. Everything is urgent. … Twombly’s paintings make me extremely alert. … Hardly had I seen the [Lepanto] paintings than I immediately knew that something atrocious had happened here. … I sensed the full extent of the horror before even learning that in this battle that lasted just a single day, 40,000 men perished and the entire Turkish fleet was all but destroyed. Harsh and brutal suffering resides in these images, at once clear and encrypted. And Twombly shows it exactly like this so as to rid the emotions of their logical and historical functions and render them to us without bias.4

Figure 1.

Cy Twombly, Lepanto cycle, 2001 (detail). Brandhorst Museum, Munich. Dimensions various. © Cy Twombly Foundation, New York.

The emotions to which Grosse alludes lack a fixed origin, as if passing fluidly through the ether; they cannot be definitively grounded in Twombly, or in Grosse herself, or in the colors and textures of the Lepanto paintings; nor do they belong to a historical event, despite Grosse’s musings. The encompassing feeling is devoid of an associated logic and resists the introduction of spatial and temporal boundaries. Grosse refers to something “atrocious” having happened—a vague enough term to cover a broad range of “bad,” “disturbing,” “shocking,” even “traumatic.” She experiences the atrociousness “here,” rather than there. I wonder how spontaneously, perhaps only half-consciously, she chose this adverb, with its connotation of immediate presence. Here—not there. Here collapses the distance between the historical battle and the sensation of atrociousness that seems to saturate the gallery holding the twelve Lepanto paintings. In addition, while facing various examples of Twombly’s art, Grosse refers to being “able to experience myself as something apart from my own name.”5 She becomes an entity that escapes its socially constructed identity, a self fully open to affect, free to go where it takes her. She is as untethered as the sensation she feels, which is not “her” feeling but something other. She does not possess the feeling; if anything, it possesses her. She alludes to atrociousness in retrospect, but, in her immediate experience, the emotion has no name.

1. Affect over Cognition

During the later twentieth century, psychologists commonly argued that people experience affect before and apart from any associated cognition. Put simply, feeling precedes thought, including any thought that may seem to accompany the feeling or reflect on it, whether subjectively or objectively.6 The position has a nineteenth-century variant, articulated by William James in 1884: “If we fancy some strong emotion, and then try to abstract from our consciousness of it all the feelings of its characteristic bodily symptoms, we find we have nothing left behind, no ‘mind-stuff’ out of which the emotion can be constituted, and that a cold and neutral state of intellectual perception is all that remains.”7 “Strong emotion” consists entirely of feeling, with no cognitive component (no identifying designation). In our condition of embodied sentience, we may have the impression that thinking must coincide with feeling, yet such an impression proves false (at least among James and many later psychologists). This impression, itself a feeling, nevertheless remains true and actual. It was felt, undeniably. The sense of simultaneity derives from our inability to reflect on feeling without introducing a second, parasitic intimation, the thought of the feeling. A verbalized thought takes feeling as its object, often expressed as a predicate adjective: “I feel anxious,” or, more elaborately, Grosse’s feeling “that something atrocious had happened here.” We feel the emotion and give it a name, but the name amounts to no more than an approximation, limited by the resources of conventional, rational language. Feeling and thinking (in words) are incommensurable. To maintain affect before cognition, we need somehow to experience the “anxious” or the “atrocious” without consciously selecting such descriptive labels or acknowledging to ourselves that it is we, with all our cultural baggage, who experience this emotion. Feeling precedes not only thinking but also self-identity.

The pragmatist Charles Sanders Peirce, philosophical ally of James, treated the experience of feeling quite deferentially, regarding it as unprocessed sensation about which little could be properly stated. Feelings or sensations that fail to refer to an indexical cause, a teleological purpose, a habitual practice, or a guiding concept will also fail or evade the language that would contain them. But here the verb “to fail” is misleading, for failure suggests success as a possible alternative; and feelings felt in isolation have nothing at which to succeed, nothing to accomplish, no communicable information to convey. Primal feeling is a phenomenon that no individual consciousness acknowledges as its exclusive possession. Possession implies control. Grosse’s intimation of atrociousness reflects back on her experience but is not its controlling, explanatory equivalent. Though some might argue that no sensation, feeling, or emotion ever arrives unprocessed and without at least some degree of recognition—some capacity to be effectively named and delineated—Peirce, on his part, dodged the problem by assigning feeling to his category of Firstness. Before Firstness, there is nothing, no Null-ness. In the non-relational reality of Firstness, feeling is isolated, even from itself, not as if quarantined, but pre-quarantined. In its essence, it is untouchable, unrelatable, incomparable: “By a feeling I mean an instance of that kind of consciousness which involves no analysis, comparison or any process whatsoever … that sort of element of consciousness which is all that it is positively, in itself, regardless of anything else. … [We cannot] gain knowledge of any feeling by introspection, the feeling being completely veiled from introspection, for the very reason that it is our immediate consciousness.”8 A feeling as such does not become an object of memory, for remembering establishes distance from the recollected feeling; we would experience the sensation of remembering the feeling rather than the feeling itself. A feeling violated, its spell broken by a person’s becoming able to reflect on it, does not constitute an aspect of Firstness but already an instance of Secondness, where subjects recognize themselves along with the objects that interact with them or resist them. As Secondness, the feeling becomes my feeling or your feeling; it becomes subject to being the object of a consciousness: “The First is too tender an idea to be laid hold of without destroying it; the slightest admixture of the idea of Second renders it no longer the positive First.”9

How to handle the fragility of feeling by means of language, which tends to generalize, conventionalize, and sometimes rigidify its objects of interpretation? How to address pictorial, sensory art through verbal criticism? In relation to the feelings that art generates, critical language is imprecise and even coarse. Its inadequacies are mitigated if it has little orientation or prejudice of its own to guide it. The ground of critical, philosophical argument, one would imagine, ought to be logical and phenomenological neutrality, a blank-slate condition that can be sensed. Critical interpretation ought to feel right by satisfying a tacit standard of intellectual integrity and objectivity. We judge reasoning as reliable because of its affect.

“Let us not pretend to doubt in philosophy what we do not doubt in our hearts,” Peirce wrote.10 Like academic psychologists and art critics a century or so later, Peirce set affect over cognition. To paraphrase: let us not claim by logical argument what we cannot accept emotionally, that is, believe “in our hearts.” When we act with a pretense to full objectivity, we accomplish no more than proving rationally what our hearts have already caused us to believe. We will have gotten nowhere beyond where we started, having become rationally convinced of what we were already emotionally convinced. If we were to conclude otherwise, we would be internally divided. Reason risks incoherence when it doubts what emotions have already committed to belief. I would not attempt to convince Grosse that a sense of the atrocious did not apply to Twombly’s Lepanto paintings. She felt this. She knew it not as a fact of reasoning but as her residue of feeling.

2. Reasonable Doubt

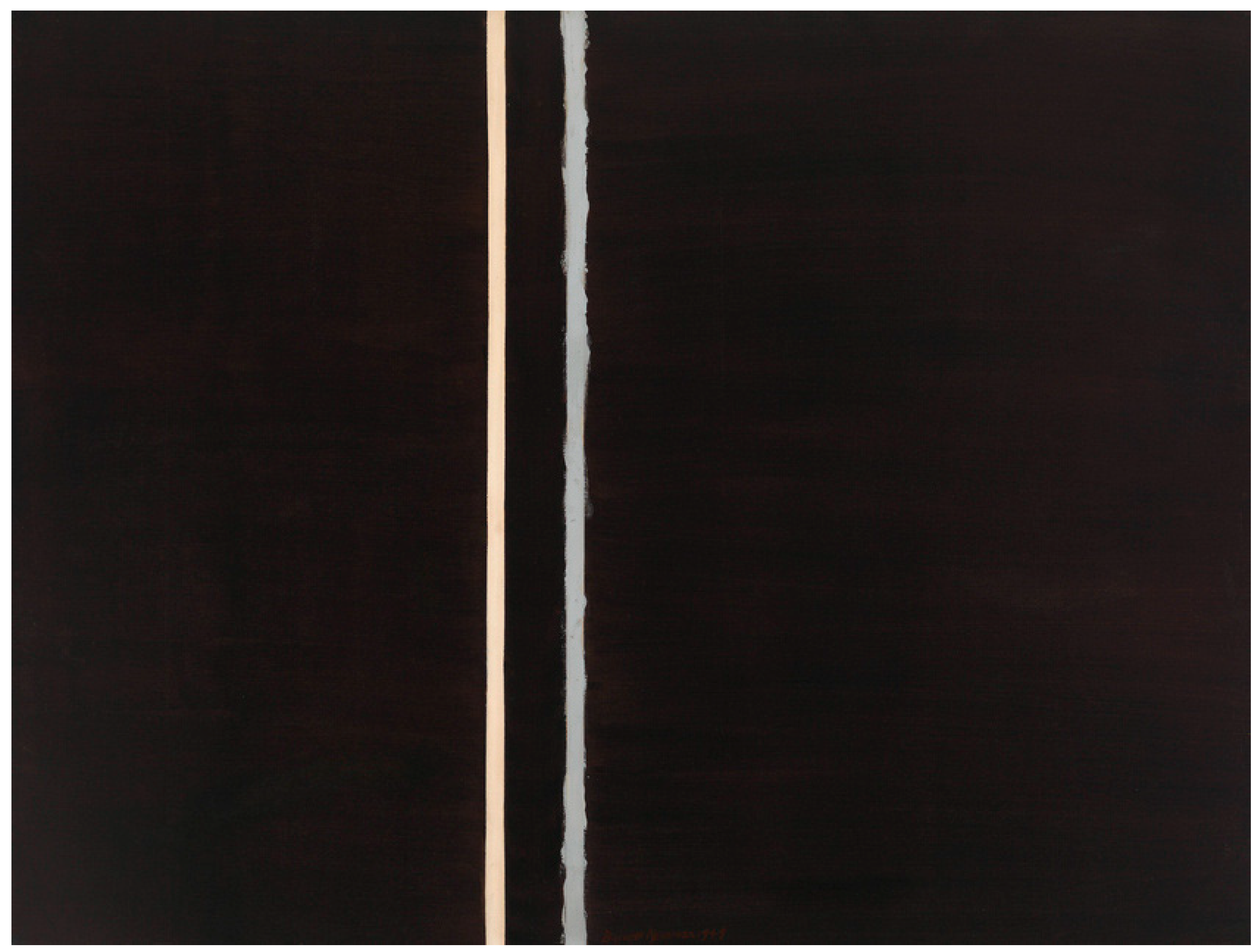

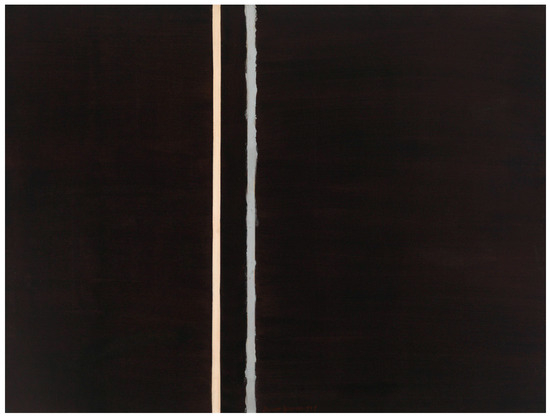

Critical writing, like visual imagery, has a feel to it. I have sometimes used the figure of chiasmus as an example of a logical and rhetorical form that causes the writer, as well as the reader, to feel both intelligent and satisfied. This is the sensation, the feeling, the affect that accompanies the logical form of the thought.11 I might even experience the feeling before having succeeded in grasping the thought. Chiasmus is useful in wriggling out of an intellectual cul-de-sac. Statements about art, a difficult topic, often assume chiasmic form. In 1966, Barnett Newman said: “Just as I affect the canvas, so does the canvas affect me.”12 The mirroring symmetry of his sentence has an emotional appeal, like symmetry in a human face, even though Newman seems ambivalent about symmetry in art, sometimes featuring it and sometimes not at all (Figure 2). The philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy provides a more ambitious version of chiasmus in locating aesthetic emotion at the origin of humanity: “Man began in … a gesture. At this [gesture], man trembled, and this trembling was him.”13 We can paraphrase to make the structure more obvious: man was the being who trembled; trembling was the essence of man. Or, still more obvious: man was trembling; trembling was man. Entity X is to entity Y, as Y is to X. It will always look and sound good. It will always feel good. As for the thought that Nancy expressed in this manner, the trembling was a feeling that, as in my extension of Peirce, experienced the “man” as much as the “man” became man (human) by experiencing trembling.

Figure 2.

Barnett Newman, The Promise, 1949 Oil on canvas. 51 1/2 × 68 1/8 in (130.8 × 173 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © Barnett Newman Foundation/Courtesy Barnett Newman Foundation, New York.

The ground of philosophy is whatever prejudiced position a person actually occupies—absolute for the individual but for no one else. Accordingly, Michael Polanyi (among his many distinctions, a philosopher of science) reached a clever conclusion in 1958: “Doubts, which we now sustain as reasonable on the grounds of our own scientific world view, have … only our beliefs in this view to warrant them.”14 So, the sense of a reasonably held doubt depends on irrational faith or belief in the tenets of modern science—the same modern science that establishes reasonable doubt as a critical method. In short, our capacity to doubt is linked to belief in the proper status of doubting, which has its reasonable limitations. Faith in reason encourages a process of reasoning that either leads to doubt or dispels it. Either way, the process itself will seem reasonable because of the faith that validated its use—doubt or no doubt.

Polanyi’s reference to “reasonably held doubt” opens a related line of inquiry centered on a legal principle. A trial jury is not supposed to reach a guilty verdict unless the evidence indicates certainty beyond any reasonable doubt. The presumption is that doubt arises in degrees. A significant degree of belief terminates an inquiry or argument, whereas a degree of doubt keeps an inquiry or argument open. A legal prosecution introduces as much scientifically tested evidence as it can and applies logic to it. In response, the defense seeks to create an atmosphere of doubt, at least a reasonable degree of doubt—doubt with some rational foundation as opposed to a mere emotional tremor of suspicion. Yet, if the proceedings generate nebulous doubt—doubt as a First feeling—applications of reason may become largely ineffectual. One common strategy is to question the certainty with which any eye-witness testifies. A witness relies on sensory input, a form of feeling. Imagine that a witness saw a running shadow and judges retrospectively that it must have been the shadowy form of the person accused of the crime. The attorney for the defense will probably avoid questioning the fact that the witness saw something shadowy, but will instill doubt with respect to the interpretation of the form. Was it really the shadow of a man? Could it not have been a woman?

In 2001, coincidentally the year of Twombly’s Lepanto, a film written and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, The Man Who Wasn’t There, portrayed a brilliant yet spurious legal defense. The strategy amounted to converting a tenuous fact to a tenuous feeling—that is, converting belief in the shaky logic of things to a situation of shadowy doubt. The Coen’s narrative is set in 1949, when an intellectually adventurous trial lawyer has just discovered the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. He ignores the qualification that it applies to particles so small that the energy or force of the light that would allow them to be observed is sufficient to cause them to change position, relative to the scale of investigation. Expanding the pragmatic scope of the principle (shifting it from the physical sciences to the human sciences), the lawyer decides that all sensory observation must change the nature of what is observed. Even everyday sights will be affected. A present-day academic involved with critical theory or, for that matter, a theorist of 1949, might agree with the lawyer. Any observational position, as well as any application of descriptive or interpretive language, alters the perception of the object of interest. Attention to things changes their situation not only locally but in the order of the cosmos (Secondness re-experiences Firstness with an ineradicable difference).

Explaining his discovery to the defendant, the lawyer summarizes it memorably: “Your looking changes things. … The more you look, the less you know.” So, the more information the prosecution introduces to the jury, the more opportunity the defense has to raise reasonable doubt. The implication for critical thought is this: the more extensive the commentary, the more doubtful the conclusion, if one is ever reached. Lines of critical commentary accumulate yet fail to converge, leaving in the margins of discourse a feeling or affect that nags at any attempt to clarify the central logic of a given situation. By invoking indeterminacy as a defense, the lawyer aims to deflect the jury from an ideologically conditioned course of reason that he assumes it would otherwise follow to a verdict of guilty (given the unfavorable momentum of the evidence, the objective hopelessness of the case, the authority of the legal system). He wants the jury to sense an aura of unfocused doubt. His strategy is to have undeniable affect influence an array of rearrangeable facts.

3. Intuition

Where doubt arises, there can also be belief—both are feelings. The rhetorical form of chiasmus takes a rational shortcut, its strong affect compensating for its gaps in logical entailment. What we call intuition may operate in an analogous manner: intuition is a mode of thinking that feels like feeling. Some years ago, I decided that Donald Judd must have worked by intuition. (Perhaps the play of intuition accounts for the unnamable feelings that his various “untitled” objects continue to provoke in me.) Key to my interpretation was a statement from a lecture Judd gave at Yale University in 1983: “I’ve always considered the distinction between thought and feeling as, at the least, exaggerated … Emotion or feeling is simply a quick summation of experience, some of which is thought, necessarily quick so that we can act quickly … Otherwise [by reason devoid of emotion] we could never get from A to Z, barely to C, since B would have to be always rechecked. It’s a short life and a little speed is necessary.”15

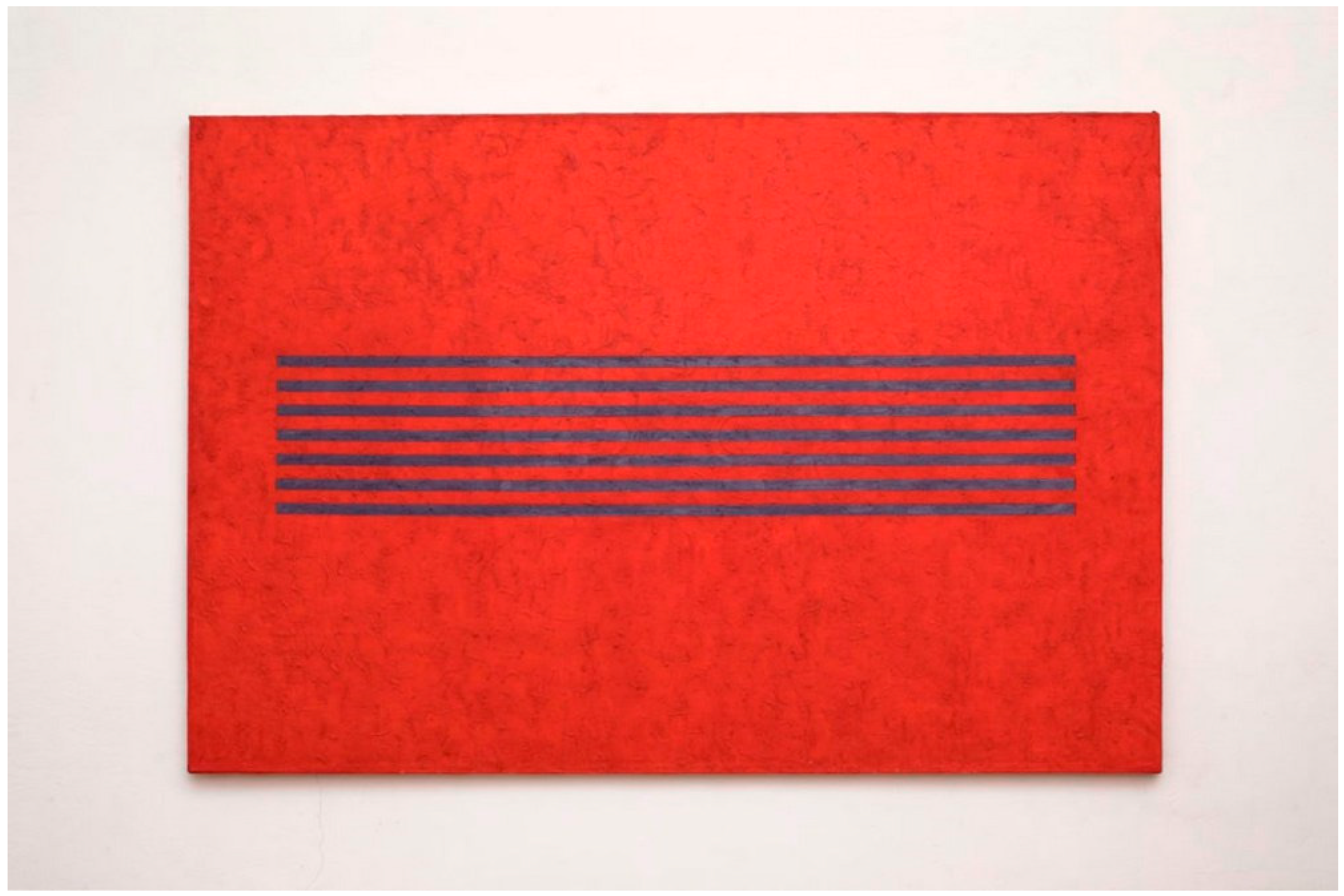

Bear in mind that works by Judd elicit multiple sensory observations independent of any realizations of logical or hierarchical order. Judd’s art does not assume the form of a premise and a set of facts leading to a conclusion—we might say instead that his art consists only of facts, nothing more than material and perceptual facts in interaction. We normally think of a whole as constituted of structured elements of some kind. But the readily identifiable elements of a work by Judd—for instance, a red rectangular prism coupled with a gray metallic pipe, asymmetrically positioned and set into a channel (Figure 3)—resist forming a composition of dominant and subordinate parts, even though one element may be larger than the other or one may be supporting the other. Each part will appear as present to sense as is the whole. Because Judd’s constructions counter any potential compositional order, we perceive both the parts and the whole for what they are: they exist together, but are also unconnected, like the before and after of an intuitive leap. This so-called, hard-core minimalist relied on feeling to adjust and complete a work.

Figure 3.

Donald Judd, untitled, 1963. Cadmium red light oil on plywood with iron pipe. 22 1/8 × 45 3/8 × 30 1/2 inches (55.2 × 115.3 × 77.5 cm). Donald Judd Art © Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC.

4. The Silence of Art

My experience of Judd’s art encourages me to extend his aesthetic intuition. I begin to doubt conclusions based solely on facts, though I accept the facts that I sense and feel. It may be that the factual elements of rational discourse never form a general argument that will be coherent for analogous cases. Generalization, like theorization, has its limits. Sensory facts that seem related to each other remain as unconnected as the two sides of a chiasmic comparison or the packets of energy that Heisenberg was trying to observe. A stable relationship may appear but will remain on the level of appearance, no more than a tentative supposition, derived from sensation—a feeling. The ultimate relationship of entities remains anyone’s guess. If this is so, where do we turn to discover reliable connections?

For an artist, this question may have an answer different from its answer for a critical interpreter. Art involves connectedness of a sort unlikely to be experienced in rational argumentation. Artistic practice is aesthetic and emotional; art appeals openly to feelings. Rational argument also appeals to feelings—it has its aesthetic attractions, its embellishments, its turns of phrase—but it attempts to disguise its rhetoric for the sake of its logic. If, by Polanyi’s claim, we understand that the practice of experimental science allows doubt to appear, we also know that—by the social conventions of discourse—a properly reasoned argument should not resort to appeals to feeling. We leave it to objects of art to solicit sensory appreciation. When they hold a viewer’s sensory and emotional interest, we deem them successful (as art, not necessarily as advocacy).

Some would demand much more than interest from a work of art: a structured body of information, the support of a thesis or a political position, or the makings of a penetrating cultural gesture, whether affirming or subversive. Judd, however, became notorious for claiming that art need only be interesting.16 In his usage, this word was not the anodyne term that it is in colloquial American English. It referred instead to a connection that a work might establish with the disposition of the viewer’s psychic and emotional state, itself induced by the work. Judd customarily recorded his thoughts, his interests, as verbal notes to himself. In 1990, he stated that sensory perception did not lend itself to systematic analysis: “We sit and look out and see, listen, and know, but cannot analyze doing it. If you think of it, you can’t do it. One reason is that it’s all very large and whole, and not discrete data. This is another gap, disconnection, that cannot be directly closed. Analysis has to work around it and on little parts of the whole.”17 No obvious mathematical, compositional, or structural principle explains the positioning of Judd’s gray pipe embedded in a red rectangular prism. To think of a principle would distract from the feel of the work. I see the two parts both together and separately, as if their connection—which is no proper, functional connection at all—were established only in my act of seeing. The work requires no further binding than this existential one, because an immediate impression of the two parts as the whole is unavoidable. Though I have just indulged in a bit of analytical reasoning about Judd’s juxtaposition of a metallic pipe and a wooden prism, Peirce (in a statement already invoked) would caution me to go no further: “By a feeling I mean an instance of that kind of consciousness which involves no analysis, comparison or any process whatsoever … which has its own positive quality which consists in nothing else [no message, no thesis], and which is of itself all that it is.”18

Judd’s note of 1990 reiterates a common phenomenological observation: “We look … and know, but cannot analyze doing it. If you think of it, you can’t do it.”19 Or, if you feel it, you cannot cognize it. This realization is not far from the Heisenberg-like lawyer’s “looking changes things.” Nor is it far from Peirce’s unfathomable jump from Firstness to Secondness: “First, feeling, the consciousness which can be included with an instant of time, passive consciousness of quality, without recognition or analysis. Second, consciousness of an interruption … I have a sense of a saltus, of there being two sides to that instant.”20 Like Peirce, Judd addresses the gap between immediate sensation and its forms of cognitive reflection. His statement of 1990 continues with a variation on Ludwig Wittgenstein: “Art [is] a slight sound in the silence. Wittgenstein’s Tractatus ends: … ‘What we cannot speak about we must consign to silence.’ Well, a little, consign to Kunst [art].”21 Art conveys what philosophical discourse cannot. Judd claims that rational analysis fails to remedy the lack of connection between sensation and its description, yet art itself, its feeling, establishes connections in situations where language remains mute.

5. Degrees of Belief and Doubt

I have cited Peirce and Polanyi, and through Judd’s statement, Wittgenstein. Like many other philosophers, including the ancients, these moderns investigated the tension between sensing and interpreting, between feeling and reasoning, between affect and cognition, between rhetoric and logic. I have also invoked the legal principle of reasonable doubt. If a prosecution team tries to establish a logical chain of events and human motivation to prove that an individual committed a criminal act, a lawyer for the defense works in the opposite direction, demonstrating that what looks logical amounts to a matter of personal feeling, and the implication of a feeling, the meaning of a feeling, can always be doubted. We do not doubt that we have a sensory experience or an emotional feeling; but we puzzle over what any feeling signifies within a social world of prescribed modes of behavior. A legal defense works to transform dispassionate facts (“I’m certain that I saw him”) into the passionate feelings that led to such sanitized judgments (“he’s a bad guy, so he must be the one that I saw”). The strategy is to divide feeling from thought and convert relatively weak beliefs into strong doubts.

Peirce wrote: “Belief and doubt may be conceived to be distinguished only in degree.”22 Why the qualification, “only in degree”? Colloquially, we commonly exchange the expression “I believe” for the expression “I think” or even the expression “I see.” If all thoughts and visions amount to beliefs—experiences that a person is certain of having had, that cannot be doubted—then the feeling of doubt itself becomes a very weak form of belief. In other words, we experience our doubt as a nuance of the same cognitive emotion we know as belief. So, if doubt and belief have a share in the same emotion or feeling, what is its identity? How should we name it? Peirce would associate this range of feeling with the experience of hypothetical thinking or what he sometimes called abduction. In turn, abduction is linked to intuition. The situation becomes more familiar if we regard this cognitive emotion as guessing. Doubt is a mode of guessing. Belief is an alternative mode of guessing. Some guesses induce conviction (belief); others induce mere hopefulness or anticipation (doubt). Neither a belief nor a doubt is permanently secure. The nature of doubt is to be a gradation of belief and that of belief to be a gradation of doubt (chiasmus again: we often conceive of dualistic relationships as reciprocal). People will say, “I believe this absolutely; I have no doubt whatever.” Such a statement lies at one end of the spectrum of feelings associated with guessing. Peirce referred to hypothetical thinking or guessing as “sensuous”; it was a form of thought close to its foundation in nameless emotion.23 Belief and doubt are affective emotions.

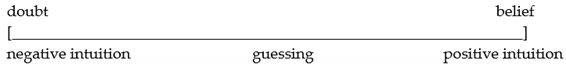

A diagram illustrates how the issue might be regarded as a matter of degree. Guessing, intuitive guessing, occupies a range from doubt at one pole to belief at the other. If both doubt and belief are themselves intuitions, then, by cultural convention, doubt has a negative valence and belief has a positive valence.

The scale of doubt and belief bears on the recent history of art. The categories currently used to define the broad lines of this history—modernism, postmodernism, the contemporary—tend to figure in polemical arguments, instilling belief in the value of one mode over another, where the ambivalence of doubt would preserve flexibility for continuing observation. To enter into the historical argument, we need to generalize (which ought to raise our doubt in reaction, for general categories obliterate perceptible differences). Assume that the decades of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s were guided by a theory of modernist practice, even though this notion remains largely unexamined. If we accept the existence of an aesthetic practice specifically “modernist,” a sympathetic account would acknowledge that it entailed exploring the creative potential that remained within the various traditional media (drawing, painting, printmaking, sculpture, photography, film).

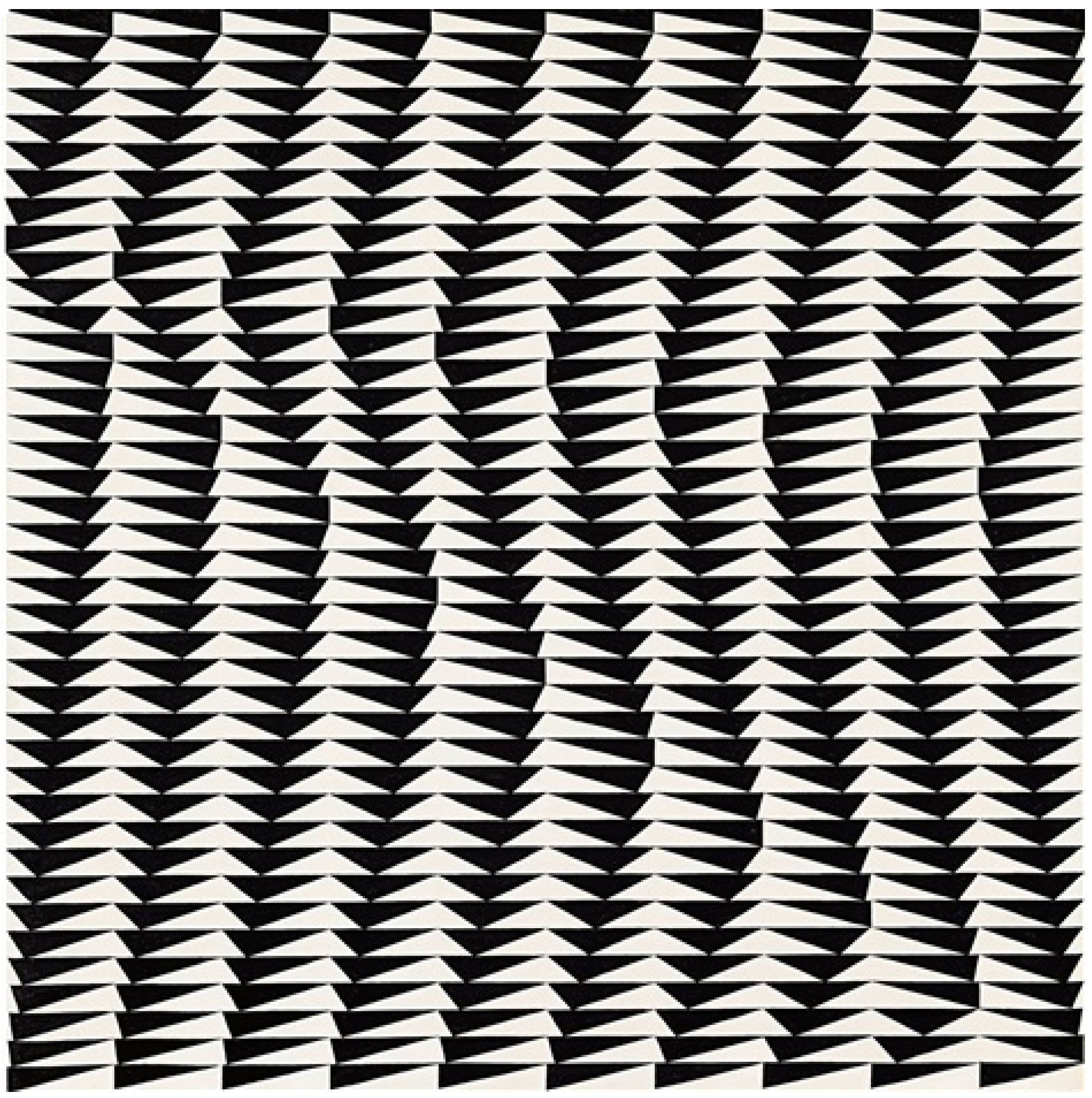

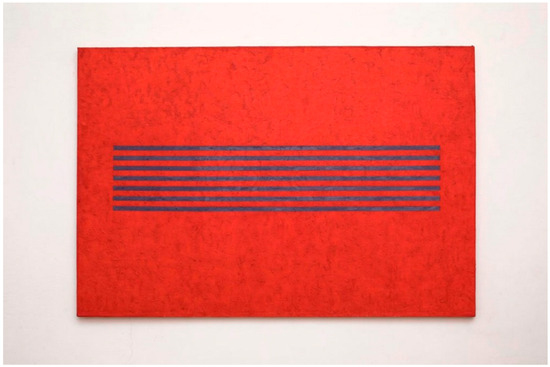

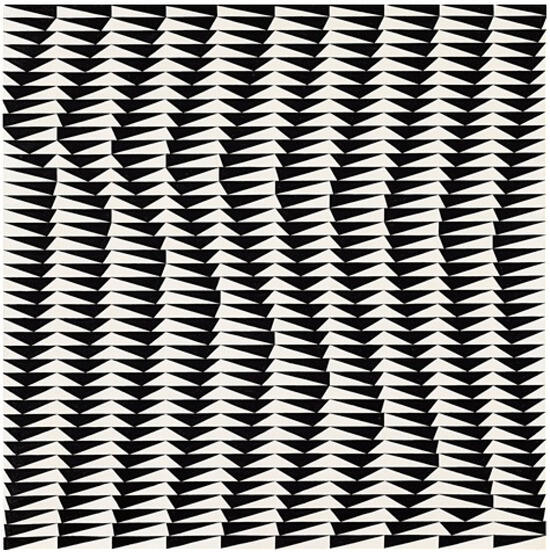

A modernist painter active during the 1950s or early 1960s, as Judd was, would not regard as serious practice acts such as throwing a can of paint into the air or painting on the surface of a living body. So-called modernists did not intend to subvert or abandon the medium but to probe and extend it. As a painter, Judd experimented with the juxtaposition of forms that could stand against each other as polar equals, without relying on allusions to figure and ground, near and far, or dominant and subordinate, for these theoretical dualities would prejudice perception. He would set a band or area of one color and texture against a field of another color and texture, aiming to intensify a viewer’s awareness of both (Figure 4). His practice did not reject the value of the art of the past, but recognized the responsibility of his current generation of artists to contribute something of their independent thinking to contemporary culture (not better, but different). With similar motivation, but with her independence too, Judd’s contemporary Bridget Riley devoted much of her early career to exploring what could be done with simple graphic figures, such as skewed triangles. The paintings that resulted, though based on known elements of design, were radically new (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Donald Judd, untitled, 1962. Oil and wax on canvas. 69 × 101 3/4 × 2 1/8 inches (175.3 × 258.5 × 5.4 cm) (unframed). Donald Judd Art © Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 5.

Bridget Riley, Shift, 1963. Emulsion on hardboard. 30 × 30 in. (76.2 × 76.2 cm). © Bridget Riley 2024. All rights reserved.

Analogously, for the sake of the historical argument, assume that the decades of the 1970s, 1980s, and perhaps even the 1990s were guided by a theory of postmodernist practice. This entailed mixing media, violating the boundaries of genres, flouting the protocols of authorship, and allowing the development of a narrative or literary message to dominate the materiality of the medium. Reflections on the concept of art outweighed concerns for the feeling of art, of its aesthetic, sensory experience.

During the most recent decades, the past thirty years or so, artists and art historians have continued to refer to theories of modernism, postmodernism, and the like, but without themselves following any particular theory religiously. We may have been living through a period of less certainty, less unanimity with respect to theoretical orientation. We are less convinced that rejecting one ideological position only to assume another (say, substituting postmodernism for modernism) results in more pertinent and beneficial forms of art, whether aesthetically or politically. If each of us is somewhat more tolerant of positions of doubt, then collectively we may feel free to discuss the sensory qualities of Judd’s color without reverting to a theory of minimalism, let alone modernism. This fluid reorientation would represent a welcome shift in critical interest. Perhaps we can perceive that Judd, when working in three dimensions (Figure 6), retained a painter’s involvement with the sensory fundamentals of color, rather than its potential for symbolism.24 We can appreciate the volumetric world of color that Judd unveiled without worrying whether this artist, as politically informed and committed as any, was pursuing the political implications of his process of industrial fabrication or his wide-ranging industrial chromatics. Such concerns would introduce a host of ideological complications, as we would need to weigh one attitude toward political life against another, limited in our judgment by our preexisting personal beliefs. The critical inquiry might be engaging, but would lead us into ourselves and away from an experience that Judd’s object was offering—a chance to be out of ourselves, a chance to escape the overruling influence of our social identities. I think of Twombly’s effect on Grosse, who becomes “able to experience myself as something apart from my own name.”25

Figure 6.

Donald Judd, untitled, 1989. Painted aluminum. 59 × 295 1/4 × 65 inches (150 × 750 × 165 cm). Donald Judd Art © Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

6. Theories Fail

I sometimes (not always) regard the present moment of art history and art criticism as one of theory-in-general.26 When I refer to “theory” in this manner, I do not mean the ideological baggage we all bring with us—specific to a time, place, and station in society—the ideological orientation that Peirce called a prejudice, informing an individual’s thoughts and actions. Such ideological preconditions accompany life within a cultural order. By “theory,” I mean instead certain elaborate discursive structures, the selective province of academics and public intellectuals, such as those associated with poststructuralist criticism, postmodernist art, and postcolonial politics. This theory is not enforced under threat of penalty, like a theory of allegiance to the state; an individual can take academic theory or leave it. The danger in accepting such theory is that its hypotheses may bring firm answers to vague questions. A critic begins to naturalize the constructed theoretical order, exchanging its fictions for the real chaos of experience—repositioning the scale or bar that I identify with guesswork. With a commitment to a theory, even a theory of doubt, we tend to shift the bar to tilt toward the end labeled “belief.” Adherence to a chosen theory promises to reward the loyalist with intellectual security. The obvious alternative, equally extreme, is to purge all theory, attempting to see and feel without direction or prejudice of any kind, as if to act solely on instinct. Noting the ironic advantage of committing less energy to conceptual thought than is customary, Heinrich von Kleist remarked over two centuries ago: “The intellect cannot err where none is present.”27 In Firstness, none is present. Sensory Firstness provides certainty, but lacks a definite self and its world of beliefs to be affirmed by it.

It may be that we need to accept uncritically, mindlessly, some degree of theoretical generalization, as Peirce argued. This we acknowledge as our prejudice. It is also fair enough to claim, as many have done, that only another blinding ideology displaces a blinding ideology. Surely, this is a pessimistic attitude toward cultural affairs, yet artists are often optimistic people. The three artists that have served as primary examples—Newman, Judd, and Riley—express pessimism about culture, but are optimistic about art. Is there something that resists the conceptual principles of a theory without amounting to another theory? Consider returning to a moment not long ago, when postmodernists were convinced that they were theoretically justified in denying the aesthetic pretensions of modernists. Many critics who favored postmodernist practice believed that cultural communication was a matter of the dissemination of existing images, whereas the modernists who preceded them were said to believe that art had its foundation in personal sensation. The advantage of recirculating existing imagery is that it can be treated ironically, subversively, as a factor of critique. The advantage of beginning with idiosyncratic sensation, as opposed to socially derived iconography, is that such a beginning remains ever new. Fanciful or not, this was one of the utopian attractions of abstract art in the postwar era: it mitigated the tyranny of representational imagery, overburdened with cultural connotations, the aesthetic dregs of a political order corrupted by fascist elements. Radically abstract art—like Newman’s, Judd’s, and Riley’s—returned sensation to the body, to its immediate vision and intimate touch. Members of a younger generation of abstractionists, such as Grosse, have followed in the same spirit (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Katharina Grosse, Untitled, 2017. 94 1/2 × 152 3/4 in (240 × 388 cm). © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Artists, whether “abstract” or “representational,” often react to cultural pressures by enhancing the sensory qualities of their work, as if to provide physical immunity to ideological mind-control. The physical has a tonic effect on the mental. Sensation clears the mind. Viewing one of Riley’s stripe paintings (Figure 8), I might be tempted to study it analytically, to comprehend its effect through the chemistry of its complex pigment mixtures. According to Riley, however, the last thing a viewer should do is worry about the singular science of her art. It is sufficient to name the colors as red, green, blue, and yellow. Forget about identifying them more precisely, Riley says—just look at them.28

Figure 8.

Bridget Riley, Arioso (Blue), 2013. Oil on linen. 59 1/8 × 101 1/4 in (150 × 257.2 cm). © Bridget Riley 2024. All rights reserved.

Along with Riley, Judd recognized that seeing a color or a shape and naming it are incommensurable actions: “A rectangle is a shape itself; it is obviously the whole shape.”29 Seeing a rectangle reveals the obviousness to which Judd referred—the recognition of a certain existence. A rectangle is rectilinear; yes, it does have right angles. But I ignore this general, theoretical definition when I feel the geometric form in its decontextualized, isolated wholeness, its actuality. Often, circumstances cause us to perceive right angles as other than subtending ninety degrees. We might doubt that a form is symmetrical or prismatic on the basis of a given point of view. This is one of the lessons of Judd’s works that consist of multiple volumetric units of equal dimensions: their placement dictates that only one among the several right-angled forms will appear “right” (Figure 9). Most likely, it would be the unit at eye level, which occupies a physiologically privileged position. In experience, no two entities, despite geometric equality, are equivalent.

Figure 9.

Donald Judd, untitled, 1966. Galvanized iron. 10 units, each 9 × 40 × 31 inches (22.9 × 101.6 × 78.7 cm). Donald Judd Art © Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Yet, some would say: the body is itself a cultural construction; no entity exists outside a conceptual system; no existence is obvious and self-sufficient; nothing stands apart from its category or type; the singularity or wholeness or exclusivity of experience is mythical. Furthermore (the argument goes), because observation is always guided by concept, we fail to observe anything that would appear to lie outside all plausible variation of the existing conceptual framework. When one experience seems equivalent to another, a concept (a generalizing category) has done its work. During the 1960s, Judd perceived that theoretical generalizations—however reasonably intentioned and formulated to debunk other, competing theories—were being pushed too far. They were threatening the specific sensory values of art, of art with feeling, with affect.

7. Affect Is Never Doubted

By Judd’s understanding of critical practice among his contemporaries, the problem for art became all the more aggravated subsequent to the 1960s. Just as sensation suffered depersonalization, so thought itself became unanchored, given the prevalence of challenges to traditional notions of authorship.30 Perhaps most troubling, theorists reasoned that because thinking finds expression in a communal language, the thoughts of individuals are not their own. The self, if there is one, must differ from itself because it thinks in alien terms. We pass from feelings not our own (Firstness) to thoughts not our own (approached by Peirce as his category of Thirdness, generalized, relational thinking). The very structure of language forces this realization on those willing to confront it.31 Language escapes the possession of its writers and even its live speakers. This theoretical position not only removes the authority of individuals from their personal beliefs, but also undermines the force of an individual’s experience of doubt. Those who author statements of either doubt or belief, venturing guesses, become mere vehicles of language, passive conductors of semiotic energy already in circulation.32 The theorist who questions such a system is left in the position of introducing resistance to existing lines of cultural transmission that will remain anyway. Critical theory of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries relegated its theorist to functioning as still another participant in the system, distinguished only by being more self-aware and more troubled by the present situation.

The critical trend that annoyed Judd developed in part within an area of literary study where resistance to interpretive conventions had, ironically, a chance of fostering a broad critique of ideology. Literary theorists were challenging the longstanding practice of interpreting texts biographically and psychoanalytically. Interpretation of this sort attended to the heroic creator far more than to the generative thing created as it entered the public domain. Roland Barthes’s celebrated essay of 1968, “The Death of the Author,” was, at its core, hardly antithetical to Judd’s interests, both intellectual and aesthetic. It preserved his concern for the sensory immediacy of what he liked to call a “particular, definite object.”33 Barthes made this claim: “It is language which speaks, not the author. To write is … to reach that point where only language acts [and] every text is eternally written here and now.”34 Recall Grosse’s use of “here” and transfer it to the feel of a text. A reader’s reading here determines the meaning—a collaborative effect of the written text and its present sensory absorption (an effect also of intertextuality: all previous writing and all previous reading converging on a present moment). I am freely applying a theory of immediate sensation to the consumption of literary texts. Analogous to Barthes, Judd discouraged viewers of his art from concluding that every fact that happened to relate to him, as the personal creator of the object, must contribute to its experience. The primary meaning of a work lay in the liberating sensation it afforded—the “here and now” of the object, as opposed to the past history of its creator, the circumstances of its creation, and the cultural connotations of its forms and materials. Consider again Judd’s journal note of 1990: “We look … and know, but cannot analyze doing it.”35 Because we cannot analyze, we might doubt the ultimate contextual meaning of what we see, but we cannot doubt that we see. Nor can we doubt that we doubt. We cannot doubt a sensation, a feeling, an affect.

An artist or author experiences the feel of color or of language as an intimate, immediate fact. Aesthetic invention is a flash of intuitive guesswork. It happens “here and now.” This here-and-now is phrasing that both Barthes and Judd liked to use—Barthes the feeling reader, Judd the feeling viewer. If Judd’s art implies a theory analogous to Barthes’s sense of textuality, it is one that acknowledges the sensory materiality of temporal experience. Artists like Judd—and Riley as well—work, in fact, from a belief. They believe that an immense reserve of experience exists outside the present limits of conceptualization and intellectual understanding.36 We may already be tapping into this reserve, but without enough sensitivity for it to affect our emotional soul. We look, yet not always with discovery or edification. Sometimes, looking fails to generate change; little registers.

Judd regarded the process of art as its own first principle; it justified itself in experience. To theorize art is merely to guess at principles, to hypothesize from a perspective that, rather than become rigidified in belief, should remain subject to doubt. A perspective changes with the next act of looking (“looking changes things”). Art consists only of feeling; its reason is felt, not reasoned. The rational interpretation of a work of art, or even a work of philosophy, amounts to one of its eventual affects. Reaching for a suitable conclusion to his Yale lecture, Judd set each of these matters of consideration—reason, feeling, guessing, art—into a unifying statement: “The function of ‘reason’ is [that] it estimates, understands and uses all that’s known and felt, guessing sometimes, to finally help make a new kind of art.” If Judd had a single aim or principle, it was to operate with “thought and feeling as one.” He realized the need for this integration because he felt it. It ached, it hurt: “The division between thought and feeling is part of course of the Christian one of body and soul, an itch to be elsewhere being easier to promote than scratching at home. But when my soul aches my head hurts, so I think body and soul are right here, here and now. They are not going to leave one by one, but together for nowhere.”37 Joined in a work of art—in its making as well as in its appreciation—thought and feeling need go nowhere else.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data in support of this argument is readily available at the publicly accessible cited sources, except for the statement quoted from the author’s personal conversation with Bridget Riley.

Acknowledgments

This essay, now considerably altered and expanded, stems from a conference presentation given at the Freie Universität Berlin, the Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry (“The Pleasure of Doubt in Art, Aesthetics, and Everyday Life,” 19–21 June 2014). The Berlin lecture, in accord with the conference theme, centered on the play of doubt in critical writing, using work of Benjamin Buchloh as a contrary example of critical absolutism. The present essay, oriented to feeling and affect as Peircean Firstness, shares with the Berlin lecture the importance of one of Peirce’s pronouncements: “Belief and doubt may be conceived to be distinguished only in degree.”

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | (Zajonc 1980). |

| 2 | Evaluators of this paper have suggested other possibilities, including Ludwig Wittgenstein (on saying and showing, mentioned below) and Susanne Langer (on a life of feeling). I might also add Henri Bergson (on matter and memory), John Dewey (on art as experience), and Roland Barthes (on the traumatic image). There are still more. |

| 3 | Regarding the differing perspectives and aims of artists and philosophers, a telling exchange occurred between Susanne Langer and Barnett Newman at a conference in 1952. Newman strictly opposed the “abstract” to the “real” (which was each artist’s imaginative creation), whereas Langer argued that the real, given in nature, could be abstracted. Newman implied, somewhat unfairly, that Langer was exchanging feeling for conceptualization (discussion session, Fourth Annual Woodstock Art Conference, Woodstock, NY, 23 August 1952, audiotape, Woodstock Art Association archives, copy on deposit with the Barnett Newman Foundation, New York). |

| 4 | (Grosse 2017). |

| 5 | (Grosse 2017). |

| 6 | Zajonc attributed the belief that “feelings come first” to a number of his predecessors. He also wrote: “One might be able to control the expression of emotion but not the experience of it itself. … The reason why affective judgments seem so irrevocable is that they ‘feel’ valid”; (Zajonc 1980, pp. 154, 156–57). |

| 7 | (James 1884). |

| 8 | (Peirce 1906, vol. 1, pp. 152–53). |

| 9 | (Peirce 1886, p. 305) (capitalization added for consistency). See also, (Peirce 1891, vol. 6, pp. 25–26): “First is the conception of being or existing independent of anything else. Second is the conception of being relative to, the conception of reaction with, something else. Third is the conception of mediation, whereby a first and second are brought into relation. …. In psychology, Feeling is First, Sense of reaction Second, General conception Third, or mediation.” |

| 10 | (Peirce 1868, vol. 5, p. 157). |

| 11 | Compare with (Peirce 1906, vol. 1, p. 155): “Every operation of the mind, however complex, has its absolutely simple feeling, the emotion of the tout ensemble.” |

| 12 | (Newman 1966, p. 189). |

| 13 | (Nancy 1994b, p. 74). In French: “silence calmement violent … L’homme en a tremblé: et ce tremblement, c’était lui”; (Nancy 1994a, p. 127). Newman (among many others) had made the same association, tracing the tradition of art back to the emergence of humanity in a moment of emotional expression, motivated by “the terror of the unknowable”; (Newman 1947b, p. 108). See also (Newman 1947a, p. 158): “Man’s first cry was a song … not a request for a drink of water.” |

| 14 | (Polanyi [1958] 1962, p. 275). |

| 15 | (Judd 1983, p. 344). |

| 16 | See, for example, (Judd 1969b, p. 205). |

| 17 | Judd, manuscript note, 18 November 1990, Donald Judd Writings, 626. |

| 18 | (Peirce 1906, vol. 1, p. 152). |

| 19 | See note 17 above. |

| 20 | Peirce, “A Guess at the Riddle” (c. 1890), Collected Papers, 1:200-01 (punctuation altered for clarity). More on Peirce’s First and Second: the two categories need not imply sequence, but rather two types of psychic phenomena. First or Firstness corresponds to what Peirce calls monadic “quality” represented as an iconic sign; Second or Secondness corresponds to dyadic “fact,” represented as an indexical sign; see Peirce, “The Logic of Mathematics; an Attempt to Develop My Categories from Within” (c. 1896), “The Icon, Index, and Symbol” (c. 1893–1902), Collected Papers, 1:230–40, 2:156–65. Peirce’s reference to “two sides to that instant” (in “A Guess at the Riddle”) addresses a continuity from Firstness to Secondness that cannot be experienced with precision; it represents, to resort to a metaphor, a dawning of articulate consciousness. Peirce preserves the separate identity of Firstness and Secondness as two cognitive/emotional states, while he also points to the unidentifiable moment of passage from one to the other. |

| 21 | Judd, manuscript note, 18 November 1990, Donald Judd Writings, 626 (capitalization added). Judd refers here to Wittgenstein ([1921] 1961). Judd’s introduction of the word “kunst” (properly, Kunst) may reflect his respect for German theories of art. |

| 22 | Peirce, “The Logic of 1873: Investigation” (c. 1873), Collected Papers, 7:195. |

| 23 | “Hypothesis [guessing] produces the sensuous element of thought”: Peirce, “Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis” (1868), Collected Papers, 2:387 (original emphasis). |

| 24 | See (Judd 1993, p. 857): “Color of course can be an image or a symbol, as in the peaceful blue and white, often combined with olive drab, but these are no longer present in the best art. By definition, images and symbols are made by institutions.” |

| 25 | (Grosse 2017). |

| 26 | Compare with the notion of art-in-general developed in (de Duve 2023). |

| 27 | (von Kleist 1810, p. 214). |

| 28 | Bridget Riley, in conversation with the author, 7 March 2014. |

| 29 | (Judd 1964, p. 136). |

| 30 | On the cultural refuge taken in “aesthetic integrity,” see (de Man 1982, p. 92). |

| 31 | See (de Man 1982, p. 98). |

| 32 | For a sophisticated form of the argument (more than a mere reversal of active and passive roles), with the authority of speech displaced by the play of graphematic writing, see (Derrida 1971, pp. 307–30). |

| 33 | (Judd 1969a, p. 211). |

| 34 | (Barthes 1968, pp. 143, 145) (original emphasis). Compare with the fundamental point, often argued during Judd’s lifetime, that the mode of representation, not the individual who deploys it, establishes the potential for meaning: “Instead of containing or reflecting experience, language constitutes it”; (de Man 1956, p. 231). |

| 35 | See note 17 above. |

| 36 | See, for example, (Riley 2007, p. 195): “Comprehension is not everything, the unaccountable has a place in our lives … Seurat, involuntarily perhaps, has presented us with the mysterious.” |

| 37 | (Judd 1983, pp. 339–40, 350) (emphasis added). |

References

- Barthes, Roland. 1968. The Death of the Author. In Image—Music—Text. Translated by Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- de Duve, Thierry. 2023. Duchamp’s Telegram: From Beaux-Arts to Art-in-General. London: Reaktion. [Google Scholar]

- de Man, Paul. 1956. The Dead-End of Formalist Criticism. In Blindness and Insight. Translated by Wlad Godzich. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Man, Paul. 1982. Sign and Symbol in Hegel’s Aesthetics. In Aesthetic Ideology. Edited by Andrzej Warminski. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1971. Signature Event Context. In Margins of Philosophy. Edited and Translated by Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosse, Katharina. 2017. C. T. S. T. Translated by J. W. Gabriel. Edited by Louise Neri. Gagosian Quarterly, Spring, p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 1884. What Is an Emotion? Mind 9: 193. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, Donald. 1964. Specific Objects. In Donald Judd Writings. New York: David Zwirner Books. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, Donald. 1969a. Aspects of Flavin’s Work. In Donald Judd Writings. New York: David Zwirner Books. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, Donald. 1969b. Complaints: Part I. In Donald Judd Writings. New York: David Zwirner Books. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, Donald. 1983. Art and Architecture. In Donald Judd Writings. New York: David Zwirner Books. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, Donald. 1993. Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular. In Donald Judd Writings. New York: David Zwirner Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 1994a. Les Muses. Paris: Galilée. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 1994b. Painting in the Grotto. In The Muses. Translated by Peggy Kamuf. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barnett. 1947a. The First Man Was an Artist. In Selected Writings and Interviews. Edited by John P. O’Neill. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barnett. 1947b. The Ideographic Picture. In Selected Writings and Interviews. Edited by John P. O’Neill. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barnett. 1966. The Fourteen Stations of the Cross, 1958–1966. In Selected Writings and Interviews. Edited by John P. O’Neill. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1868. Some Consequences of Four Incapacities. In Collected Papers. Edited by Charles Hartshorne, Paul Weiss and Arthur W. Burks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1886. First, Second, Third. In Writings of Charles S. Peirce: A Chronological Edition, Volume 5, 1884–1886. Edited by Christian J. W. Kloesel. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1891. First, Second, Third. In Collected Papers. Edited by Charles Hartshorne, Paul Weiss and Arthur W. Burks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1906. Phaneroscopy. In Collected Papers. Edited by Charles Hartshorne, Paul Weiss and Arthur W. Burks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, Michael. 1962. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, Bridget. 2007. Seurat as Mentor. In Georges Seurat: The Drawings. Edited by Jodi Hauptman. New York: Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist, Heinrich. 1810. On the Puppet Theater. In An Abyss Deep Enough: Letters of Heinrich von Kleist with a Selection of Essays and Anecdotes. Edited and Translated by Philip B. Miller. New York: Dutton. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1961. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Translated by D. F. Pears, and B. F. McGuinness. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, p. 151. First published 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc, Robert B. 1980. Feeling and Thinking: Preferences Need No Inferences. American Psychologist 35: 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).