Abstract

This article describes the development and public performances of La Liga de la Decencia, a new play presented as part of the 2023 New Works Festival at the University of Texas at Austin. Inspired by the cabaret scene and teatro de revista of the 1940s in Mexico City, La Liga de la Decencia combines live performance and video art to explore how hegemonic gender and social norms shaped by the emergent nationalism of postrevolutionary Mexico continue to oppress femme and queer bodies today across the US–Mexico border. Through satire, parody, and dance, La Liga de la Decencia problematizes the social, class, and gender norms as established by the cultural elite and the state. Following research-based theatre as an inquiry process, this article describes how writing and directing this play allowed for a deeper understanding of the dynamics of a historical period. By mixing facts, fiction, and critical commentary, La Liga de la Decencia investigates history through embodiment.

1. Introduction

I kept adjusting my top. In my attempt to “look the part” of a 1940s cabaretera at a sleazy cabaret, I put on a tight lace corset and placed a red rose in my hair. In my role as a waitress/usher, I welcomed patrons into the black box theatre-turned-cabaret by offering them a glass of sparkling cider.1 I only spoke to them in Spanish—even though only about half of the audience could really understand me—and explained that the popcorn they had on the small table in front of them was there for them to eat, yes, but also to throw at the actors.

Once the show began, I stayed close to the exit doors, which not only helped me fulfill my front-of-house duties but also positioned me in a place where I could really watch the audience watch the play. From my position, I also modeled audience behavior by throwing handfuls of popcorn, one after the other, at the actor wearing the large piñata head crafted after President Manuel Ávila Camacho (Figure 1) “¡Pinche corrupto!” I yelled, which encouraged the patrons to throw kernels at the actor as well. Defeated, President Camacho exited the stage, leaving a graveyard of palomitas behind him.

Figure 1.

Bruce Gutierrez as the emcee and Gabriel Gómez Reyes as President Ávila Camacho in Jessica Peña Torres’ La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Thomas Allison, Courtesy of University of Texas at Austin. April 2023.

La Liga de la Decencia premiered in Spring 2023 as part of University of Texas at Austin’s Department of Theatre and Dance’s New Works Festival. A week-long biennial engagement, the festival “is not just an event, but a celebration of the continuously ongoing process of creating new work”(The New Works Festival 2023). Student-produced, directed, and performed, the festival presents more than thirty new pieces of theatre, dance, music and experimental, installation, and mixed-media art and welcomes a diverse audience including UT- and non-UT-affiliated people, undergraduate and graduate students, faculty and staff, as well as Spanish-speakers and non-Spanish speakers.

Since opening night, the show felt different from other works that I have created or collaborated on. Because the setting was that of a cabaret and not a theatre, there was no fourth wall, no expectation of bourgeois rules of decorum (i.e., avoiding loud chewing, talking, etc.), and the overall atmosphere was that of a site of socialization (a nightclub or bar) and not of a place of passive observation—a cabaret demands the audience’s active engagement. Such place-based differences made me experience the play both as a patron (throwing popcorn, yelling at the characters, etc.) and as the playwright. Surprisingly, a part of me that only turns on when I am on stage myself activated: the actor’s double conscience.2 In this double reality, I could continue fulfilling my role as a cabaretera while simultaneously observing the audience’s reactions. Since the piece addressed the kind of demographic attending the performances (most likely educated, progressive Texans) I was curious of their response: what would they think of the material? Would they understand the cultural-specific nuances the play discussed? How would they feel about the critical tone? And being quite honest, would they ultimately enjoy/appreciate our work?

La Liga de la Decencia built off my 2020 show México (expropiado),3 in which I played a farcical depiction of late dancer and choreographer Amalia Hernández, founder of one of Mexico’s most influential dance companies: Ballet Folklórico de México. As part of the cultural elite of the postrevolutionary period, Hernández used her connections, privileged positionality, and ballet and modern dance training to build a lasting repertoire based on the dance traditions of the diverse regions of the territory of what is now called México. In México (expropiado), I satirized the origins of ballet folklórico in the mid-1950s, specifically how Hernández appropriated Indigenous dances and adapted them to the concert stage, the heteronormative and gendered representation of characters such as el charro and la china poblana, and the exoticization of Afro-Mexicans through racist representations. Through text and movement—theatre and dance—I aimed to complicate popular understandings of lo mexicano as pictured in the ballet folklorico repertoire.

In La Liga de la Decencia, a term now colloquially used to describe the socially ultra conservative in Mexico, I focused on the 1940s for the many similarities this era shares with the present time—specifically around themes of morality, surveillance, and censorship. Utilizing cabaret and the teatro de revista form, La Liga de la Decencia explored the social, gender, and class dynamics of postrevolutionary Mexico by asking the following questions: How do hegemonic social norms shaped by the emergent nationalism of the postrevolutionary period continue to oppress femme and queer bodies today? How do these norms travel across the US–Mexico border? Performing is a way of knowing and, through this piece, the ensemble, creative team, and myself were able to embody historical research to investigate notions of censorship, morality, and oppression. By performing this new work, we both formulated and delivered a direct critique to both the American and Mexican nationalistic systems that oppress our own brown, femme, and queer bodies.

Using research-based theatre (Belliveau and Lea 2016) as an inquiry process for this article, I describe how writing and directing this play allowed me to more deeply understand the dynamics of the historical period I was researching through newspaper clips, documentaries, academic articles, photographs, and films, while exploring issues of gender, class, race, sexuality, and nationalism as they are still prevalent today. By mixing fact, fiction, and critical commentary, La Liga de la Decencia gave me the opportunity to investigate history through embodiment. Finally, this article is an opportunity to honor my friend and colleague Tenzing Ortega, who recently passed away and collaborated through his design in the production of La Liga de la Decencia.

Through a combination of excerpts of the script, description of the live performances, a historical overview of the time period, testimony from some members of the creative team, and personal reflections after the closing of the production, I provide evidence of the research I undertook for the writing and directing of La Liga de la Decencia. I begin with an excerpt of the opening scene, which sets up the time and place of our play: a cabaret/teatro in Mexico City in 1945.

SCENE 1

| EMCEE steps on the stage. Dances to the intro of |

| “Danzón Nereidas”. He is wearing a tuxedo and bowtie. |

EMCEEBuenas noches damas y caballeros, bienvenidos sean todos ustedes a La Ópera de París, el lugar más perfecto para pasar una buena noche en esta bella, brillante, insaciable capital del vicio, la Ciudad de México.

| He notices his audience are mostly gringos so he |

| rolls his eyes and continues in an aside. |

EMCEEAy, excuse me, I forgot today I’m in el gabacho. I will continue in English but please keep in mind that for this play we’re in Mexico, where we (mostly) speak Español.

| He resumes his introduction. |

Hello, hello! Welcome ladies and gentlemen to La Opera de París! The most perfect place to spend your night in vice capital, Mexico City. Help yourselves to our signature drink, a Cuba Libre! Not that Cuba is very free as of now, pero pos we keep toasting so that they too can overcome some of that shit we already got out of, no? Let me hear it for our democracy! Yes, yes! Ay, no me pongan esa cara! At least we got ourselves a presidente, not a dictator or a führer, am I right? Démosle un fuerte aplauso al Oficial Mayor, nuestro «presidente caballero», Manuel Ávila Camacho.

| An actor wearing a giant piñata head of |

| Camacho enters the stage. The performers |

| backstage boo effusively. Some throw rotten |

| tomatoes at him. The EMCEE, in a rehearsed |

| rush, directs Ávila Camacho backstage. |

| The EMCEE composes himself. |

EMCEEAy, pero it’s not my fault! He won fair and square! O eso es lo que nos dicen que digamos. Let’s remember, remember that in this country, we are free! Libres! Free to elect, free to reject, and free to collect! Así es, mis bellos miembros de esta sociedad cosmopolita, we are free indeed! Thanks to our brothers across the ocean who helped defeat the fascists. So we must celebrate. Y hablando de Cuba…Let’s welcome to our arrabal, I mean burdel, I mean… cabaret…¡María Antonieta Pons y sus rameras, I mean, rumberas!

| A rumba dance ensues. Four dancers join the |

| EMCEE on stage. One of them is dressed as a |

| sexy María Antonieta Pons in the Konga Roja |

| film. The other dancers are dressed in sequence, |

| feathers, and crystals. The dance ends. |

2. La Liga de la Decencia: Synopsis

It is 1945 and Mexico is traversing a time of relative political stability. A cabaret in la colonia Obrera welcomes audience members from all walks of life to enjoy a night out in vice capital, Mexico City. Leading the troupe is a nameless emcee, a middle-aged barrio-educated man who presents a variety of acts on a dusty wooden stage. Among the characters he introduces are María Antonieta Pons (a Cuban dancer from Mexican cinema films) and her rumberas, Blanca Nieves and her siete hermanos (of the 1937 Disney film),4 the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, two Aztec Eagle pilots of the Mexican Air Force (who fought alongside American forces in WWII), and Xiadani, who the emcee introduces as a Tehuana (an Indigenous woman of Oaxaca, Mexico).

One night, as the cabaret is booming with a lively audience, the emcee begins hearing and seeing strange images and sounds depicting a mix of cartoons, forbidden films showing nudity, and nationalist propaganda. The show turns into a search to find whoever is causing the interruptions. Through a final monologue, the emcee reveals truths about himself while urging the audience not to leave him, as La Liga de la Decencia, an organization that polices people’s behavior, is bound to apprehend him (Figure 2).

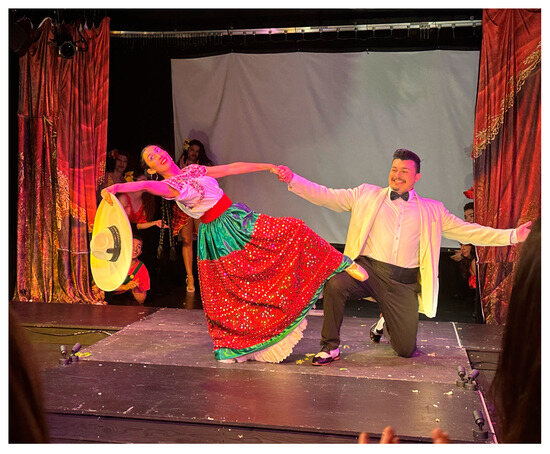

Figure 2.

The cast of La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Thomas Allison, Courtesy of University of Texas at Austin. April 2023.

3. The History, Politics, and Social Background of La Liga de la Decencia

I grew up in Reynosa, Tamaulipas, a Mexican border town where nothing happened.5 In my childhood and teenage years, I watched TV and read magazines that positioned Mexico City as the place where everything happened. Artists, celebrities, music concerts, dance, and theatre companies were all based in the capital city. I yearned for an opportunity to participate in the frenzy, and it was not until my mid-twenties that I had the chance to experience the city for the first time when I moved there to dance professionally in a ballet folklórico company. I lived in la Ciudad de México for a total of five years, where I became inspired to research the characters I had learned to play as a ballet folklórico dancer (i.e., la china poblana and la Tehuana). Through my work in México (expropiado), I became interested in learning how these characters ended up on stage in the first place. Teatros de revista, with origins preceding ballet folklórico, seemed like a good place to begin investigating the complicated and layered genealogies of these characters. For instance, although the ballet folklórico dances had not been created for the concert stage specifically, there were recurrent tropes that kept appearing in revista, specifically that of la tehuana and la china poblana.

In addition, I became very interested in investigating the political climate in which these characters, tropes, and dances began to develop given how long they have remained on the theatrical stage and how integral they have become to nationalistic and popular conceptions of mexicanidad (Mexican identity). The 1940s was a decade of complicated social relations between classes in Mexico, and the policies of the time reflected such conflicts. Because the play’s development took place in Austin, TX, moreover, I felt compelled to look closely at the changing relationship between Mexico and the United States during this period, specifically after U.S. involvement in the Second World War. After careful consideration, I decided to examine three important political and social themes of the 1940s: the hegemonic dominance of the ever-ruling Partido de la Revolución Mexicana (PRM, now Partido Revolucionario Institucional or PRI), the social control of La Legión Mexicana de la Decencia (or La Liga de la Decencia), and the Mexico–US relationship, specifically related to immigration.

The 1940s, Class Tensions, La Liga de la Decencia, and WWII

The first half of the twentieth century was a time of notable social transformation in Mexico. After the armed phase of the revolution had ended (1910–1920), thousands and eventually millions of people migrated from the pueblos to the city. The economic growth generated by industrialization produced a blossoming middle class that became better positioned to access recreation. In Mexico City, entertainment became polarized between those activities referred to as “sano divertimento,”6 such as parks, theaters, and art galleries, and those associated with vice and sin, such as dance halls, cabarets, and nightclubs (Ceja Andrade 2019).

Torn between adapting to the global trends that pushed for a modern Mexico while preserving “buenas costumbres” or traditional moral values, Mexican society started establishing a series of binaries that reinforced class systems, such as feminine/masculine, national/international, decent/indecent, and moral/immoral. Those seen in public places during nighttime, such as vedettes, padrones (pimps), and homosexuals, among others, were characterized as “immoral” for ostensibly contributing to society’s downfall. Thus, the cabaret became synonymous with the brothel and the dancer with the sex worker (Ceja Andrade 2019, pp. 281–82).

Popular media, such as newspapers and magazines, served as means to educate the masses on the difference between what became categorized as “decent” and “indecent” behavior. In her book El mapa “rojo” del pecado. Miedo y vida nocturna en la Ciudad de México 1940–1950, historian Gabriela Pulido Llano explores how a discourse of fear permeated not only people’s imaginary, but also the press and the prolific film industry in Mexico. More than one hundred films were released throughout the 1940s that furthered the idea that people, especially women, who followed a path of vice and sin were destined to a disastrous demise. These films belonged to a genre that came to be known as cabaretera or fichera and which contributed to Mexico’s época de cine de oro (golden age of film). Some of the examples of these films include Mientras México duerme, La insaciable, Pecadora, Mujeres de cabaret, La bien pagada, and Aventurera, among others. The films featured the character of the fallen woman, a fragile being in need of a benevolent, strong male figure—often representing the state—who would save her from the dangers of the nightlife. Most frequently, these films concluded with the female protagonist experiencing a tragic end (Pulido Llano 2018).

One of the organizations that rigorously regulated societal behaviors during this period was La Liga de Decencia. Following the Cristero Rebellion (1926–1929), the Catholic Church sought to fortify its position in Mexico in response to the separation of church and state established by the 1917 constitution. In 1929, Mexico’s Archbishop, Monsignor Pascual Díaz y Barreto, founded Acción Católica Mexicana (ACM). Shortly thereafter, the Legión Mexicana de la Decencia (Mexican Legion of Decency or LMD) was established through the initiative of the Orden de Caballeros de Colón (Ramírez Bonilla 2023, pp. 124–25). According to Pope Pius XI, the Legión was a “crusade for public morality aimed at revitalizing the ideals of natural and Christian righteousness” (Pulido Llano 2018, p. 55). Historian Laura Camila Ramirez Bonilla asserts that the Legión was the ACM’s branch responsible for overseeing culture, entertainment, and general conceptions of the family, based on the moral surveillance of the film industry. From 1931 to 1954, the Legión classified 10,826 films, documentaries, and theater performances, with 20 percent assigned the category “C” (reproachable for indecency). Motives for categorizing a spectacle under this classification included attacks on the family unit (adultery, divorce, and free love), offenses to the Catholic faith, crude language, nudity, depictions of suicide, and inappropriate diversions (such as dancing). To enforce censorship, the Legión asked its devotees to sign a promise to reject “malos espectáculos” (evil or bad spectacles). As a result of the activism of the predominantly conservative laity, the Legión gained significant traction in both public and political spheres, solidifying the place of the Catholic Church in Mexican society. Through the strict categorization and censorship of spectacles, the Legión aimed to strengthen the Catholic Church’s tenuous relationship with the state and to “re-Christianize” the Mexican population in an era of modernization (Ramírez Bonilla 2023, pp. 135–37.)

Popularly known as La Liga de la Decencia, the Legión gained significant influence during this period, partly attributed to President Manuel Ávila Camacho’s (1940–1946) more permissive stance regarding the Catholic Church’s role in the public sphere and the membership of his wife, the first lady, Soledad Orozco. One of the most well-known actions taken by La Liga, for instance, was the prohibition of the screening of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs for how the protagonist of the animated film incited a life of immorality by living with seven men. They had a similar response to the statue “Diana Cazadora” by artist Juan Fernando Olaguibel. Originally commissioned by Ávila Camacho, La Liga de la Decencia believed that the figure of a nude woman in public would incite lasciviousness, so they ordered that the statue be covered with a loincloth.7 (Figure 3) La Liga de la Decencia championed other principles including indecency in live performance and film, a strict dress code for men and women, and the eradication of the “sin” of homosexuality (Rangel 2023).

Figure 3.

“Fuente de la Diana Cazadora sobre Paseo de la Reforma.” Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Mexico City, Mexico. 1950.

For the middle class, it became imperative to stay as distanced from the life of sin and immorality as possible to maintain social ranking. María Fernanda Lander explains that buenas costumbres helped urbanites feel closer to Europe by emulating their code of conduct in a time where an increasing kinship to Europeans elevated status. In postrevolutionary Mexico, this desire translated to the need to demonstrate a specific set of characteristics that could help the new nation thrive in a modern future. For middle-class Mexicans, Lander wrote, “morality, virtue and good customs would become the instruments of the regulatory character that the cultured Hispanic American society imposed on itself.” One of the most influential guides for good customs was El Manual de urbanidad y buenas maneras (1854) by Venezuelan author Manuel Antonio Carreño (1812–1874). Carreño’s manual, however, did not seek to educate the working class so that they, too, could become “virtuous.” Rather, the meticulous code of conduct aimed to differentiate who, among the middle class, was capable of giving the nation a “civilized identity” (Lander 2002, pp. 85–86).

Given the growing gap between the middle and the working class, there were two types of places where people could go for entertainment: the great theaters in the west of the city and las carpas and teatros de revista. Regarded as “el género chico” (low brow), these popular theaters became a space to call out politicians, present risqué musical numbers featuring female nudity, and serve the nationalist sentiment of the postrevolutionary period. After the period known as “el porfiriato” ended in 1911,8 actors began to utilize their platform with more liberty in the carpas of neighborhoods such as Tepito, Garibaldi, Santa María La Redonda, and the markets of Lagunilla and La Merced. Sometimes precariously erected on electrical cables and with very poor sanitation, carpas became the space where anyone from a housewife to a sex worker could enjoy themselves. It was not only a sociable place, but it was also where actors and spectators could subvert gender roles and, most importantly, express their political discontent (Sluis 2016, p. 53).

Derived from the Spanish Zarzuela9 and the French revue, teatros de revista (which began appearing in the late 1870s) served as the spaces where everyday folks could see themselves reflected on stage (Vázquez 2020). Following the print magazine format, revistas did not follow a single unifying theme, but presented individual acts that included comedy, dance and musical numbers, satire, and the introduction of stock characters that mocked politicians and the elites. Opposite to the “high art” performed in the theatres of the west of the city, the revista genre was crude, overtly political, and unafraid to challenge the status quo (Sluis 2016, pp. 46–47).

In teatros de revista, a “jefe de familia”10 would direct, perform, produce and “would even sweep the floor”.11 The audience, well versed in the matters discussed on stage, would yell, whistle, and show antipathy to the actors. The musicalípticos (musicals) presented in these theaters, scandalized La Liga de la Decencia because of how much skin the female dancers showed on stage. For the critics of the time, revistas represented a threat to the social order for how they created new, diverse publics hailing from disparate social and racial backgrounds, which disrupted established gender and class norms. The City’s Departmento de Diversiones Públicas (Department of Public Diversions), for instance, worked with the Department of Public Health to regulate spectacles to ensure that the spaces conformed to not just health and safety regulations, but that their content also adhered to moral standards (Sluis 2016, p. 49).

By the mid-1940s, however, teatros de revista began shutting down due to various factors, including the pressure exerted by La Liga de la Decencia and the city inspectors, who believed that revistas exhibited “vulgar dancers, bad music, and grotesque dance”.12 In addition, the overtake of the American-imported sketch shows and the growing popularity of television and film contributed to their downfall. Since actors started migrating to film and television, publics, too, began enjoying the comedy offered in the teatros through their own home screens, thus, teatros de revista slowly began to disappear.13

Some of the images that circulated in popular culture, including in “el género chico,” were inspired by the nationalist sentiment of the postrevolutionary period. Adapted from westernized conceptions of Mexico, such representations came to embody the nation as “domestic exotics” for national and international dissemination. The domestic exotic was a source of inspiration for indigenismo and mestizaje ideologies. Indigenismo, on one hand, asserted that the roots of modern Mexican identity lied in its Indian culture (Hershfield 2008). Described by J. Jesús María Serna Moreno, indigenismo is a “group of policies developed concerning Indigenous people by national powers, constituted or not in nation state” (Serna Moreno 2001, p. 87). Influenced by indigenismo, artists began incorporating images of the “domestic exotic” into their works. Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, for example, painted emblematic murals in places such as the National School of Agriculture at Chapingo near Texcoco (1925–1927), in the Cortes Palace in Cuernavaca (1920–1930), and the National Palace in Mexico City on commission by the national government (1929–1935) (Biography n.d.). The muralists, inspired by the image of the “Indian” as imagined by the cultural elites, portrayed Indigenous men and women in relationship to colonization and the revolutionary movement (Hershfield 2008, p. 138).

The image of the Tehuana and her traje (regalia), for instance, was incorporated into the insurgent national identity through film and printed media. Non-Indigenous women began wearing the emblematic traje and were featured in postcards, posters, magazines, and movies as markers of Mexico’s pre-colonial past. One of the most notable examples is Hollywood star Lupe Velez, who personified a Tehuana in the popular film La Zandunga (1938), directed by Fernando de Fuentes (Figure 4). Scholars such as Francie Chassen-López and Alexa Matta-Abbud have concluded that this popularized image of the Tehuana, however, was constructed for a male gaze that not only exoticized Zapotec women but also essentialized and mythified their famous clothing (Abbud 2021, pp. 86–106; Chassen-López 2014, pp. 281–314). As a former ballet folklórico dancer, I myself wore the traje to perform the cuadro de Oaxaca, the dance suite representing the region. I was not aware at the time, regrettably, of how the Tehuana and her image had been appropriated for decades by elite Mexicans. My current artistic work addresses such issues of cultural travesty—which I will describe later.

Figure 4.

Lupe Velez in La Zandunga (1938). Screen capture from clip. Clip|Tele N. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gJiBZIdzBEQ. Accessed on 1 September 2023.

On the other hand, Mestizaje became the most powerful and dominant ideology of the postrevolutionary period. Arguing that the mixing of indigenous and Spanish roots would give way to a new race, mestizaje influenced the creation of characters such as el charro and la china poblana, which placed the mestizo as another type of “domestic exotic.” Maria del Carmen Vázquez Mantecón notes that la china poblana, as a symbol of Mexican identity, represented the “grace and virtue of the Mexican woman”, who served as the object of heterosexual male desire by balancing a dichotomy between wife or prostitute (Vázquez Mantecón 2000, p. 124). This character also appeared frequently in the writing of 19th-century authors who described her as a mestizo woman who did not conform to social standards but rather enjoyed the freedom of her love encounters. Similar to how la china poblana became a romanticized version of the Mexican woman, el charro became “the symbol of the ideal Mexican man” (Mendoza-García 2016, p. 319). After the revolution ended in 1920, a nationalistic discourse called for the romanticized construction of a specific image of the charro as a strong, skilled, hard-working man to represent male vigor. The images of la Tehuana, el charro, and la china poblana circulated widely in popular media, thus influencing popular conceptions of Mexican identity.

Contrary to the recurrent social changes, the political sphere was much more unyielding. Partido de la Revolución Mexicana or PRM (now Partido Revolucionario Institucional or PRI) dominated the political landscape from the end of the revolution around 1920 to the end of the twentieth century. In 1940, for instance, PRM candidate Manuel Ávila Camacho became President Lázaro Cárdenas’ pick to continue the hegemony of his party. Even though Cárdenas had promised the country fair elections, he decided to secure the party’s continued mandate through the appointment of Ávila Camacho as his successor, which made voters suspicious of the transparency that the PRM had claimed. According to Albert L. Michaels’s account, Cárdenas thought that Ávila Camacho, popularly known for being “moderate,” was the only candidate capable of keeping the different military and working-class factions united under the threat of fascism from Europe (Michaels 1971). With his election, PRM remained in power until the end of the century and thus, censorship and repression perdured as the norm through many more decades.14

World War II, in fact, had become highly relevant to Mexican politics. The sinking of two Mexican tankers by German U-boats in 1942 led Mexico to declare war to the Axis powers. Even though the relationship between Mexico and the U.S. had deteriorated after President Cárdenas expropriated oil from American companies in 1938, the U.S. invited Mexico to train Mexican combat flyers. In 1944, with President Ávila Camacho’s blessing, Mexican pilots of Escuadrón 201 joined their American counterparts in training and then in combat in the final months of the war, forever changing the military and political relationship between two neighboring countries. Escuadrón 201 has been Mexico’s only military unit to ever engage in combat outside the country’s national borders (Malloryk 2021).

Using the historical and political atmosphere of Mexico as background, I began to think how one event related to the next and, especially, how they affected the real bodies of the people living under the PRM’s regime. While La Liga de la Decencia certainly established moral and social codes, it was the state that actively enforced policies to secure Mexico’s position, especially in relation to the U.S., during a time of global tensions. How could I incorporate such research into a festival piece? Moreover, how could staging a fictional theatrical work help me make sense of a period that continues to impact the way we perceive ourselves as Mexicans and Mexican Americans? I began writing monologues and short scenes that explored some of the events I was encountering as means to complicate the notions of Mexican identity that were often set to erase and oppress the bodies of Indigenous, femme, and queer folks. Below is a continuation of the script, in which I satirize some of the guidelines imposed by La Liga de la Decencia.

EMCEELadies and gentlemen, let’s offer a round of applause to the señoritas! Aside from being the most sensual dancers of the Mexican film industry, they are the unofficial ambassadors of La Liga de la Decencia!

| The four dancers curtsy first to the right, then to |

| the left, then they turn around and bow facing |

| the back, their butts to the audience. |

EMCEEMuy decentes nuestras señoritas. Now, please tell me, Miss Pons: what is La Liga de la Decencia’s mission? Para los que no lo sepan aún.

MARIA ANTONIETA PONS(Reciting into the microphone) To preserve the morals and good customs of Mexican society.

| The dancers pantomime the next section. |

EMCEEThat’s right. Miss Pons and her rumberas are making sure we go back to the old days, you know? The days of virtue and morality, the days of the buenas costumbres. We mustn’t forget that the most important thing that will keep our nation strong is our values. Yes! Yes! We must strive to preserve our integrity, our rectitude…

| With this last word, the dancers make a gesture |

| suggesting anal coitus. |

EMCEEIt’s important that we bring back order to this decaying society… the film industry is polluting our minds and hearts with images of immorality… sensual touching and caressing on the screen! No, no, no! And here in the city, los hombres… que andan con otros hombres! Los homosexuales!

| Dancers gasp! Then wink at the audience. |

EMCEEDios nos libre de esas joterías (he crosses himself). Y lo peor… qué es eso de que women want to wear pants! Imagínense.

| Dancers show off their butt (they are not |

| wearing pants, all right!) |

EMCEEBut how will we ever become an upstanding society, Miss Pons? Aren’t we doomed already?

MARIA ANTONIETA PONSWe are working on three basic principles to bring back decency to our society. Please welcome the Board of education!

| The dancers produce paddles and look |

| menacingly at the audience. |

EMCEE¿Y cuáles son esos principios?

| The dancers pantomime the following |

| principles. |

MARIA ANTONIETA PONSNumber one: To prohibit the showing of kisses on the mouth in the movies!

EMCEEMe parece muy bien…

MARIA ANTONIETA PONSNumber two: to establish a moral dress code different for men AND women.

EMCEEExcelente…

MARIA ANTONIETA PONSAnd number three: to absolutely eradicate the disease of homosexuality.

The dancers applaud.

EMCEE(Relieved) Ah… of course, of course! La Liga de la Decencia has a sound plan to keep our society afloat! Muchísimas gracias for all your charity work, Miss Pons. ¡Qué haríamos sin usted!

María Antonieta Pons shrugs.

EMCEEWe’d be lost, that’s for sure. Démosle un fuerte aplauso, a big round of applause to Miss Pons and her rumberas: the unofficial ambassadors for La Liga de la Decencia!(Figure 5) Figure 5. Jeremy Benavides as Maria Antonieta Pons and Gabi Carrasco, Elyse Rosario, and Valentina Reyes as Rumberas in Jessica Peña Torres’ La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Alan Márquez. April 2023.

Figure 5. Jeremy Benavides as Maria Antonieta Pons and Gabi Carrasco, Elyse Rosario, and Valentina Reyes as Rumberas in Jessica Peña Torres’ La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Alan Márquez. April 2023.

4. La Liga de la Decencia, the Play

Following the teatro de revista format, La Liga de la Decencia is presented through acts announced by an emcee. In each act, a new character explores a relevant historical, social or political theme of the 1940s through dance and comedy. In the following section, I describe the live performance as presented at the 2023 Cohen New Works Festival.

The play begins with the emcee, adeptly played by Bruce Gutierrez, who welcomes the audience to “La Opera de París,” a cabaret/teatro in Mexico City in 1945. The first character we meet is President Manuel Ávila Camacho, played by an actor wearing a giant piñata head who only enters the stage to be effusively booed by the ensemble and is “popcorned” by the audience.15

Shortly after, the emcee introduces María Antonieta Pons, the Cuban-Mexican actress of rumbera films such as Konga Roja (1943), and her three rumberas, who dance to “Soy Cubana” in a display of feminine sexuality. Played by Jeremy Benavides in drag, Pons satirically teaches us about La Liga de la Decencia, of which she is an “unofficial” member. With the help of her rumberas (Valentina Reyes, Gabi Carrasco, and Elyse Rosario), she explains the important rules that La Liga believes will help keep the morals of Mexican society. Through sensual dance, satire, and cross-dressing, Pons and her rumberas subvert the basic precepts that the conservative Liga de la Decencia sought to impose.

The second act introduces us to Blanca Nieves y sus siete hermanos of the 1937 Disney film. Blanca Nieves was played by Andie Flores, a talented local performer best known for her creative personification of the hyper-feminine through drag and her obsession with embarrassment. The hermanos were portrayed by Brandt Agosto-Medina, Emilio Mejía, and Gabriel Gomez Reyes who carry four puppets of the rest of the seven hermanos amongst them. Wearing a tight-laced blue corset, a short yellow petticoat, tall red heels and false voluminous breasts, Blanca Nieves entices her seven hermanos through her seductive dancing. Moving to Artie Shaw’s “Whistle While You Work,” a big band jazz tune inspired by the film’s soundtrack, the seven hermanos try over and over again to reach for Blanca Nieves’ breasts and buttocks to no avail. When Blanca Nieves suddenly uncovers her (false) breasts, the hermanos faint from love, and Blanca Nieves takes advantage of their frail condition to take what she can from their pockets. She is only able to find one bill in the smallest of the hermanos’ pockets in time for the dance to end in a group tableaux. The emcee reminds folks that her film was not allowed to screen in Mexico for not upholding buenas costumbres and thanks her for coming all the way from the United States. He then invites the audience to dance to José Urfé’s danzón “El Bombín de Barreto.” Pons, her rumberas, Blanca Nieves, and the hermanos invite patrons to join them on the dance floor.

We then meet the famous Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, played by dancer and choreographer Venese Alcantar, who dances “Jarabe Tapatío” dressed as china poblana in pointe shoes, just as Pavlova did on her visit to Mexico. Her performance is remembered through the following passage, read by one of the hermanos:

It is comforting to see that our national dances, which until now were cultivated in barrio theaters, in the artistic pilgrimage of Anna Pavlova, will be exported, and that foreign audiences, by applauding them, will know that Mexico, the country of wonderful vitality, has its own art, which is at an immense distance from the ill-intentioned calambur of the popular actor and from the insipid obrillas16 in which the most abominable pelafustans of our social bottoms appear as a regulatory subject.17

Offering the counterpart to Anna Pavlova is Xiadani. Wearing the emblematic traje de Tehuana, Xiadani (portrayed by Esmeralda Treviño) is presented as “María,” who has come all the way from a pueblo in Oaxaca to the big, capital city hoping to sing at Teatro de la Ciudad, one of the most prestigious venues in town. Until she gets her shot, says the emcee, she serves as a waitress in his cabaret; contrary to her colleagues, she does not perform in seductive costumes but is only allowed to wait on the patrons.

When Pavlova begins to exit dancing to Camille Saint-Saëns “The Dying Swan,” a strange array of images and sounds are displayed on stage. Saint-Saëns’ melodic music is interrupted by sounds of static and archival news clips portraying the U.S. declaration of war to the Axis powers. Pavlova’s balletic movements suddenly turn into short, disjointed contractions and her demeanor changes from a wide smile to an expressionless countenance. Shortly after, the images and sounds stop, “The Dying Swan” resumes, and Pavlova continues her graceful exit. It seems as though no one has noticed the disruptions but the emcee who, while confused, carries on the night’s show.

After admiring Pavlova’s performances for making Mexico’s dances similar to Europe’s, the emcee asks Pons, her rumberas and the hermanos to pass around copies of El Manual de Carreño to the audience. This is their chance, says the emcee, to become educated like the Europeans. A volunteer audience member is asked to read the following passage from Carreño’s manual:

Through a careful study of the

rules of urbanity, and by contact

with cultured and well-educated people,

we come to acquire what is especially called

good manners or good customs,

which is nothing more than decency, moderation and opportunity

in our actions and words,

and that delicacy and gallantry

that appear in all our external movements,

revealing the softness of customs and the culture of understanding.18

Instructed by the emcee, the audience turns to page five of the manual, where they will be able to learn how to become “decent”. Surprisingly, page five is blank, giving the cast and the audience no hope to become “decent” indeed. A display of what happens when there is no possibility for virtue ensues, as the characters of the cabaret perform a sultry dance to Desi Arnaz’s “Rumba Matumba”. In the midst of their burlesque dancing, a second disruption of strange projections and sounds makes the characters freeze. The projections show a collage of video, audio, and images including clips from the censored film La Mancha de Sangre (1937)19, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, and The Three Caballeros (1944), archival footage of a celebration of Mexican Independence in 1943, featuring a gymnastic display by 50,000 athletes spelling the phrase “Unidad Nacional”,20 a documentary film about Texas’ contributions to American efforts in World War II, and reconfigured war propaganda posters with phrases such as “Loose Talk Can Cost Lives”. The projections suddenly cease, and the characters unfreeze to resume their rumba dancing. Perplexed, the emcee proceeds with the show.

He brings out Blanca Nieves once more to report about the latest presidential elections. Before she can tell us about the fraud committed by Partido de la Revolución Mexicana through gibberish—she cannot speak—the emcee interrupts her and gets her escorted off stage.21 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Bruce Gutierrez as the emcee, Andie Flores as Blanca Nieves, and Valentina Reyes as Rumbera in Jessica Peña Torres’ La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Thomas Allison, Courtesy of University of Texas at Austin. April 2023.

The show continues with the introduction of two Aztec Eagle pilots of Escuadrón 201, who have been recruited by the U.S. Airforce to fight alongside the Allies in the Pacific theatre. Portrayed by Agosto-Medina and Mejía, the pilots enter the stage marching to a steady drum roll that marks their disciplined steps and they proceed to carefully pantomime military drills that convey their performance in the war. They sit in chairs while a projection of archival footage covers a backdrop to show the point of view from their cockpit. Simultaneously, a voice-over narrates some of the moments in combat as reported in an AirForce Times article:

V.O.As he crossed the steep ridgeline while leading his flight of four P-47s, 1st Lt. Carlos Garduno rolled his Thunderbolt over, put the nose down into a steep dive, and then leveled out his wings. With the target in his sights, his airspeed at virtual terminal velocity and the altimeter unwinding, he pickled his two 1000-pound high-explosive bombs over the Japanese warehouses.

With both hands Lt. Garduno pulled the stick back into his lap, his plane clearing the water at the bottom of the dive with only 500 feet to spare. As he climbed back to altitude, he looked over his shoulder delighted to see columns of black smoke shooting up from the target. Unexpectedly, he also noticed a roiling ring of white water on the Vigan beach 300 feet from the shore. A Japanese anti-aircraft gunner had claimed his wingman, Fausto Vega, on his 20th and last birthday.22

Their masculine display, however, is paired with contrasting stereotypically feminine movement as soon as the emcee begins to describe their “valor” and suggestively touches their shoulders, backs, and rears. Satirizing the efforts of the Mexican pilots, the emcee bestows them with the “los más guapos de la guerra”23 award and directs the entire cast and audience to sing the Mexican National Anthem in their honor. One of the hermanos brings a large Mexican flag on stage, and the whole cast proceeds to passionately chant “Mexicanos al grito de guerra, el acero aprestad y el bridón, y retiemble en sus centros la Tierra, al sonoro rugir del cañón”.24 The procession becomes an overt jibe at the nationalism of the time (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Brandt Agosto-Medina and Emilio Mejía as Pilots of Escuadrón 201 and Bruce Gutierrez as the emcee in Jessica Peña Torres’ La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Thomas Allison, Courtesy of University of Texas at Austin. April 2023.

Once more, the strange video projections disrupt the act and a distorted version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” displaces the Mexican national anthem. The characters freeze while a cacophony of the following elements take over the stage: videos of President Ávila Camacho speaking to a crowd; the image of a waving American flag,; audio of a newsperson speaking of migrant child labor in 2023; disfigured elements of the WWII propaganda poster “Americans All: Let’s Fight for Victory”; archival clips of farm workers (braceros); hundreds of immigrants breaking through the Ciudad Juárez–El Paso border in March 2023; media reporting events from the two Americans who were killed in Tamaulipas, Mexico, in 2023 with the news ticker reading “Our Border has Become a War Zone” and “NY Times Investigation Finds Migrant Children Exploited”; women protesting femicides in Mexico; images of Robb Elementary school in Uvalde, TX (where the third deadliest mass shooting occurred just last year); and juxtaposed videos of Mexican President Andres Manuel López Obrador and Republican Congressman Dan Crenshaw fighting about fentanyl trafficking across the border.

The disturbing images and sounds cause the emcee to lose his cool. He begins to angrily unravel and question whether someone in the audience is causing these disruptions. In the midst of his anger, the characters unfreeze and watch incredulously as their leader becomes aggressive. Xiadani gets worried and tries to appease him. The emcee tries to silence her but she stands her ground. She reveals that she is not really a Tehuana, but a barrio girl who has been dressed as an Indigenous woman for the American audience’s gaze. Xiadani, in fact, has never left the city, despises wearing the Tehuana traje as a costume and being “paraded” in front of the audience as an exotic fruit for them to consume. Xiadani is not a Tehuana, after all, but a woman obligated to dress the part, to don a costume that can fool audience members into thinking she might indeed be a Tehuana from Oaxaca.

After a heated argument, the emcee fires all the characters and forcibly kicks them out of the space. Through a final monologue, he reveals truths about himself while urging the audience not to leave him, as La Liga de la Decencia is bound to apprehend him. The show ends when two people in black suits come through the door before a blackout.

5. Historical Research as Embodied Practice

Creating La Liga de la Decencia for the 2023 New Works Festival involved two processes: writing the script and staging the play. To write the script, I looked at archival sources and historical accounts, which I then combined with my own fiction writing. Some of the sources that informed the writing were films of the period, such as La Mancha de Sangre (1937) and Salón México (1949), as well as WWII propaganda posters and Carreño’s manual. I also spent time searching through diverse sources such as newspapers, archival footage and documentary films detailing historical events, including Ávila Camacho’s election, Pavlova’s visit to Mexico, and the involvement of the pilots of Escuadrón 201 in the war.

The historical accounts and archival sources inspired a series of characters and scenarios which were based both on my research and my imagination—fact and fiction. For example, I looked at historical accounts detailing why La Liga de la Decencia blocked the screening of Blanca Nieves for allegedly transgressing society’s morals by living with seven men. I imagined that the actors in our own teatro de revista would criticize the censorship they experienced by creating a burlesque dance number in which the protagonist was an overly sensual Blanca Nieves that indeed searched for the love of seven men (albeit four of them represented through puppets) as a way to protest oppression. Teatro de revista actors, after all, were adept at addressing social issues by pushing boundaries at every opportunity. In addition, including Blanca Nieves in the play gave us the opportunity to share with the audience that a movie that we might think of today as innocuous, would be seen in 1940s Mexico as a work worth prohibiting.

Another instance in which I mixed historical research and fiction was through the character of Anna Pavlova. Pavlova dressed as china poblana, specifically, served to examine the nationalist sentiment of the postrevolutionary period in Mexico. Anna Pavlova’s performance of “Jarabe Tapatío” in la Plaza de Toros indeed moved intellectuals to yearn for a transformation of the nation’s folk dances. For the elites, Anna Pavlova dignified Mexican dances through her skillful adaptation, as evidenced in the newspaper passage read in the play. Her performance influenced the creation of ballet folklórico as a new concert dance genre that infused ballet and modern dance with the diverse dances of Mexico. Looking to disidentify with the practices of choreographers of the twentieth century (i.e., Amalia Hernández), Alcantar and I worked to satirize Pavolva’s historical performance by exaggerating the “balletic” aspects of the dance—such as the wide turnout, back extensions, turns, and kicks. Alcantar combined the parodical execution with whimsical facial expressions and an odd accent that placed Pavolva’s character nowhere near Russia nor Mexico. Through Pavlova’s character, we aimed to criticize the prevalent choreographic practices that distort and exoticize folk dances in Mexico (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Venese Alcantar as Anna Pavlova and Bruce Gutierrez as the emcee in Jessica Peña Torres’ La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Bella Varela. April 2023.

Unlike Pavlova, who proudly wears the china poblana traje as a costume, Xiadani reluctantly sells the image of the exotic Indigenous woman. Through her character, I explore how mestizo women all over Mexico learned to wear Indigenous peoples’ clothing as a costume to present as “other” to foreign audiences, a form of travestismo cultural25 (cultural travesty). Although some might believe they are honoring the culture of their Indigenous ancestors by wearing these garments—and not going beyond the very superficial action of “dressing as”—folks might be actually perpetuating a violent practice of cultural appropriation that only serves to exoticize Indigenous peoples. For Indigenous peoples, their trajes are not a costume that allows them to dress as someone else, but a part of their identity. By creating the character of Xiadani, who does not feel comfortable wearing regalia from a community to which she does not belong, I wanted to complicate the audience’s understandings of traditional clothing, who gets to wear it and, when we wear it as a costume, what happens to our identity and to the trajes (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Esmeralda Treviño as Xiadani in Jessica Peña Torres’ La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Thomas Allison, Courtesy of University of Texas at Austin. April 2023.

As discussed earlier, I combined historical facts and characters with fictional scenarios to illustrate the complexity of the social and political landscape in Mexico during the 1940s and to explore how these same issues remain relevant in today’s context. Underscoring all scenes, moreover, was a representation of the state’s influence over every aspect of everyday life: from manipulating national elections, through establishing the kind of films audiences had access to, dictating how concert dance should represent Mexican identity, and to censoring the type of clothes people could wear. In other words, including characters from both real life and those inspired by real-life events helped me create a world where I could examine many of facets concerning the elite and the state’s oppression over the Mexican people on a cabaret stage.

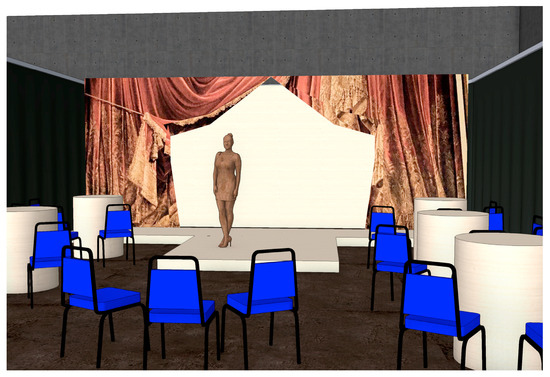

For the staging process, I was supported by a talented creative team and ensemble that not only brought to life my research, but also further complicated the social issues I set to explore. The scenic design, for instance, was created by the late Tenzing Ortega. Since Ortega lived in Mexico City for most of his life, he was able to visually interpret the setting of the play. We spent most of our discussions figuring out budgets and possible resources, since he did not need a “translation” for the Mexican theatre scene. On the contrary, his wealth of experience and knowledge about Mexico’s dance halls, night life, and entertainment greatly enriched the overall design of the piece. For instance, he proposed the idea to stage the work in a small black box theatre so we could adapt the space to that of a cabaret. His design featured a small “T” shaped stage, a sort of thrust, so that the audience could sit around small tables, very close to the performers (Figure 10). Ortega also collaborated with Bella María Varela in the design of a curtain imitating that of the Paris Opera House, which gave our cabaret its name. Ortega’s impact will stay with us beyond this project. Descansa en paz, querido amigo.26

Figure 10.

Tenzing Ortega’s scenic design for La Liga de la Decencia. April 2023.

The music of the show, as well, helped us craft a very specific environment for the audience, since it was mostly sourced from archival materials of the 1940s. Supported by ethnomusicologist and professor Jacqueline Avila, media artist Eliot Fisher (Sound Designer) researched archival versions of old vinyl records focusing on danzón and rumba pieces such as Acerina y su Danzonera’s “Danzón Nereidas”, José Urfé’s “El Bombín de Barreto”, María Antonieta Pons’ “Soy Cubana”, and Desi Arnaz’s “Rumba Matumba”, to recreate the Mexican cabaret scene of the 1940s. In most cases, these tracks were sourced from unmastered digitized versions, which communicated period-specific texture and timbre—critical aural information—“even before a note of any of the songs played”(Fisher 2023). In tandem to the dance hall music, audiences were exposed to scores inspired by the nationalism I aimed to examine; “Jarabe Tapatío”, “Mexicanos, al Grito de Guerra”, and “The Star Spangled Banner” were some of the songs that we included.

The projections created by performance and media artist Bella María Varela, furthermore, greatly supported the dissonance between the satirical tongue-in-cheek actions of the characters and the morality proposed by La Liga de la Decencia. Her work, which focuses on exploring the southern border through a lens of pop culture and social media, queerness, and white privilege, became key in the team’s understandings of the relationship between Mexico and the U.S., especially as we tried to bridge two timelines: the WWII era and the present time. Varela’s archival research, similar to Fisher’s and Ávila’s, provided a solid foundation for the unequivocal critique we aimed to convey, specifically towards the end of the play. Her collage work in the form of videos, audio, and images from archival films, documentaries, cable news footage, and posters, served to draw parallels between the social climate of the war era and the present day. Varela commented:

I pulled imagery of immigration, elections, military, and sexuality from pop culture and the media and edited the clips into videos in an experimental and semi chaotic manner to show how messy and blurry the borders between these two countries and time periods truly are. For me personally, the videos are calling out the hypocrisy of xenophobia and racism in the U.S. towards immigrants from Mexico and Central America.(Varela 2023)

The imagery and sounds that Varela carefully curated and (re)mixed helped us establish a strong critique of the present moment (Figure 11). Bridging Mexico’s history of oppression and the imposition of “decent behavior” via select groups form the 1940s to the current climate not only in Mexico but also in the U.S. became significant to explore with the festival’s audience, especially given our location in the heart of Texas, where expanding censorship is currently taking place. In Texas, new laws surveil and seek to silence many of the performances and identities featured in La Liga de la Decencia. The character of María Antonieta Pons, specifically—who is written to be played by an actor in drag—inadvertently became part of a controversial political issue. Senate Bill 12—better known as the “drag ban”—was set to prohibit “sexually oriented performances” where minors were present, with a fine of up to $10,000 per violation” beginning 1 September 2023.27 Interestingly, I had written Pons’s role before the “drag ban” had been proposed in Texas; by the time the play opened on 3 April 2023, however, the legislation was already well underway. Proceeding with the play as written and rehearsed meant we were already pushing a boundary that we had not thought to pursue. Without planning it, we were becoming more like the artists of teatro de revista we were portraying.28

Figure 11.

Jeremy Benavides, Venese Alcantar, and Andie Flores with Bella Varela’s projections for La Liga de la Decencia. Photo by Thomas Allison, Courtesy of University X. April 2023.

Another instance in which the play and reality blurred occurred on opening night, when the emcee asked for an audience volunteer to read a passage of Carreño’s manual. Khristián Méndez Aguirre, a graduate student and colleague, was called upon to read. As soon as he saw the excerpt, however, he refused to comply with the task and the emcee proceeded to read it himself. Later, Khristián mentioned to me he was not sure if the activity was satirical or if we, as a company, really wanted the audience to faithfully study the manual. His reaction to the text was so visceral that as soon as he had been handed it, he mimicked breaking it in two, and when he was asked to read it, he could not proceed given his solid disagreement with the material. As the playwright, watching a colleague reject the manual informed me of how contemporary audiences might feel about the moralizing discourses perpetuated not only by the church but also by the state.

The following excerpt is part of the last monologue of the play, which addresses the Texas audience directly and bridges the two timelines (1940s–today) and geographic/cultural places (Mexico–U.S.).

EMCEEYou might not think that now, but this place did a lot of good for a lot of people. I mean, what do you think these dancers did before I paid them to dance? Wha, what did you think they had access to? Two of the hermanos, Eric and Luis, can’t even read. They’re all coming from pueblos, Michoacán, Veracruz, Nayarit… so no, they couldn’t really aspire to much. And Xiadani? What, you think I really don’t know her name? We come from the same place: la calle… I’m working my ass off to save these people, to give them a chance. Because, what will happen if I don’t?

They’ll end up here, in Texas. That’s right. Or in Florida, or in Martha’s fucking Vineyard. And guess what? Sometimes there’s no liberals to welcome them with food and clothes and jobs. So what happens? They end up ostracized from society and… I know it’s no excuse for what I’ve done but guess what? You’re here, so now you gotta hear me out. Y sabes qué… don’t tell me the sweet story of how you, yes, you and you and you and you love immigrants. Fuck that. Have you met one? And I don’t mean your educated white-passing Latino neighbor in Mueller who works at Salesforce. I mean the unaccompanied minors, the asylum seekers who don’t know a shit of English.

I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to put the blame on you. Please don’t go. I am sorry. De verdad, no… no se vayan. Por favor. I know you’re just trying to do the right thing. I believe you are doing the right thing. I am sorry. Please, please…The moment you exit those doors, they’ll come for me. They’ll charge me with subversion and that will be the end. And I don’t have anywhere to go. I can’t go back to Mexico. I can’t go back to mi carpa. I can’t go back to… La Liga de la Decencia. And what will happen to Andrea? And Xochitl, and Mayra, and Luis, and Eric, and Xiadani… They need me!Blackout

6. Conclusions

How does historical and archival research become alive in a work of fiction? What does that performance do in the body, especially for brown, queer, and femme students at an R1 university in Texas? Writing and directing La Liga de la Decencia was an experience that allowed me to navigate important questions around censorship, morality, and policing not only in Mexico but also in the United States, where it is becoming a norm to silence folks who are not white, Christian, heterosexual, and cisgender. By performing history, I aimed to investigate prevalent notions of the nation as embedded in characters and tropes of the 1940s while provoking the audience’s perceptions of Mexican identity. One of the largest challenges the creative team and I discovered through the public performances was that some audience members felt “lost” in our culturally and geographically rooted piece; it appeared as though we needed to offer further exposition of their southern neighbor. Kairos Looney, our dramaturg, offered some thoughts when I approached them about this specific feedback. They replied:

Prevailing feedback worried, ‘What about the audience members who did not get it? If La Liga is for them, too, what will you change to open up and provide them entry points to the culturally specific signs they do not recognize and process?’ In response, as a dramaturg on the project, I wonder why the imperative of accommodation falls to the creator of the piece, rather than the saturated audience. Consider instead: saturated audiences need to learn how to not get it. Here saturation is a “gumming up”, an accumulation of signs that cannot be metabolized by the subject. For the saturated audience, the sheer density of references (i.e., resplendent worlding) acts as a match to their racial conditioning to set aflame embodiments of alienation, resistance, and even resentment. I want the saturated audience to practice finding pleasure in not knowing, in how their internalized racial mythologies crack open. Or, perhaps, in taking the initiative to do a google before they show up (Looney 2023).

As a queer Latinx international graduate student, I was nervous on opening night, specifically when the emcee began delivering his last monologue, where I as a playwright expressed my views on immigration, especially of folks coming from the southern border. I reside in the United States legally, under a visa that allows me to pursue a doctoral degree and work a white-collar job that provides me health insurance, among other benefits. I recognize that most other immigrants, in fact, arrive in the U.S. without any of these opportunities and are relegated as “aliens” by most, even sometimes by those who think of themselves as progressive. Presenting this bilingual play in Austin, TX, where legislation polices brown, queer, femme, and trans bodies, as a queer Latinx international student, was a complicated dance between my academic and artistic research, personal freedoms, and the compliance I must submit to as a desirable foreigner in the United States.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Rebecca Rossen and Michael Meiburg DeWhatley for their feedback in the writing of this piece. I also want to thank my colleagues of the Performance as Public Practice program at UT Austin for attending dress rehearsals and public performances and for offering their valuable insights, including Yuge Ma, Alejandra Martorell, Whitney Mosery, Eliot Fisher, Kairos Looney, Khristián Méndez-Aguirre, siri gurudev, Henry Castillo, Erin Valentine, Yunina Barbour-Payne, Shannon Woods, and Professor Roxanne Schroeder-Arce. Lastly, I want to thank all the collaborators of La Liga de la Decencia for their input and creativity. The piece was largely shaped in community. Creative team: Jacqueline Avila—Musical Dramaturg; Marina DeYoe-Pedraza—Puppet Artist and Choreographer; Eliot Gray Fisher—Sound Designer; Kairos Looney—Dramaturg; Carmen Martinez—Scenic Construction; Claudia Morales—Costume Construction; Tenzing Ortega—Scenic Design; Roxanne Schroeder-Arce—Faculty Advisor; Davina Silva—Assistant Director; Stephanie Shaw—Stage Manager; Gavin Strawnato—Lighting Design; Bella María Varela—Multimedia Director (Video Art, Costume Design, Cabezudo and Scenic Construction); Kenzie Wells—Cabezudo construction. Cast: Bruce Gutierrez—Emcee; Esmeralda Treviño—Xiadani; Venese Alcantar—Anna Pavlova; Jeremy Benavides—María Antonieta Pons; Andie Flores—Blanca Nieves; Brandt Agosto-Medina—Pilot 1/Hermano 1; Emilio Mejia—Pilot 2/Hermano 2; Gabriel Gomez Reyes—English Speaking Hermano; Gabi Carrasco—Rumbera 1; Valentina Reyes—Rumbera 2; Elyse Rosario—Rumbera 3; Bella Varela—Understudy.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I really wish I could have served them hard liquor but being at a university limited my free offering to our audience. |

| 2 | Theorized by Konstantin Stanislavski in An Actor Prepares (1936), the actor’s double conscience is a dual state of mind where an actor is immersed in both the role they are performing and the reality of their surroundings. |

| 3 | An original evening-long piece of dance theatre, México (expropriated)—which premiered as a web project in 2020, during the pandemic, and on stage in Mexico City in April 2022—is my attempt to rechoreograph the ballet folklórico form as established by Hernández in the 1950s. |

| 4 | Because some characters were based on the Disney film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, we used their names in Spanish for the public performances. After considering the history of the word, especially how it has been used as a derogatory term to refer to little people, I use the rhyming word “hermanos” to refer to Blanca Nieves’ (Snow White’s) seven friends. |

| 5 | That was, of course, my childhood impression of my hometown. I now know Reynosa had a thriving nightlife and I am excited to write about it sometime in the near future. |

| 6 | Translation: Healthy enjoyment. |

| 7 | It was not until 1968 that the cover-up was removed. Since the statue was damaged, a replica was ordered and it now stands proudly nude in Paseo de la Reforma. Fernanda Salinas (2022). |

| 8 | “El porfiriato” is the period of Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship (1876–1880; 1884–1911). Like other dictatorships in Latin America, this period was characterized by both modernization and political repression. Encyclopedia Britannica (2023). |

| 9 | Zarzuela is a musical and theatrical genre prominent in late 19th and early 20th century Spain. Exhibiting a “utopian impulse”, zarzuela humorously inverted societal norms. Initially critiquing the liberal order of the mid-19th century, later zarzuelas championed national and social harmony while cautioning against potential dystopian scenarios arising from labor and gender demands or regional separatism. Carlos Ferrera (2015). |

| 10 | Translation: Head of household. |

| 11 | Socorro Merlín. “Documental: Los Teatros del Pueblo” (My translation). |

| 12 | Archivo Histórico del Distrito Federal, Mexico City, Diversiones Públicas, “Teatros”, vol. 812, file 1661/24. In Sluis, Deco Body, Deco City, p. 55. |

| 13 | Álvaro Vázquez. “Documental: Los Teatros del Pueblo”. |

| 14 | Learning that Cárdenas had orchestrated a fraudulent election at the end of his term changed my own perspective of such a highly regarded historical figure; since that event was not included in the federal government-issued history textbooks I read through grade school. Cárdenas had been instrumental in perpetuating the hegemony of PRI, which ended when Vicente Fox of Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) won the presidential election of 2000. |

| 15 | Through this short bit, we sought to break the standard etiquette of theatre spaces and establish the mood for our cabaret: a place of casual socialization without a fourth wall. Ávila Camacho’s appearance and rejection by the ensemble, as well, helped us inform the audience about the political climate of the time. |

| 16 | Translation: little plays (with disdain). |

| 17 | Luis E. Rodriguez for El Universal Ilustrado quoted in Ximena Rojas (2021). My translation. |

| 18 | Manuel Antonio Carreño, El Manual de Urbanidad y Buenas Maneras. (Venezuela: 1877), p. 32. |

| 19 | Directed by Adolfo Best Maugard, La Mancha de Sangre featured the first full female nude in Mexican film and was censored. |

| 20 | Translation: National Unity. |

| 21 | In this scene, we provide a glimpse of the political climate of the time, and a critique to the PRM for not only defrauding voters, but for silencing those who dared oppose them publicly. |

| 22 | AirForce Times, quoted on Santiago A. Flores. Mexicans at War: Mexican Military Aviation in the Second World War, 1941–1945. Latin America@War. Helion and Company. 2019. |

| 23 | Translation: the most handsome pilots of the war. |

| 24 | Translation: Mexicans to the cry of war, prepare the steel and the bridle, and the Earth tremble in its centers, to the sonorous roar of the cannon. |

| 25 | Rodriguez and Domínguez (2016) define travestismo cultural: “This is defined as the appropriation of the image of the other, its assimilation and adaptation, as an alternative to build a new ego entity, which is only possible from the lenitive abandonment of a part of one’s own sign-symbolic tools (that is, the entire cultural arsenal). of a people or civilization, its reflection in the different forms of social order and its incidence in shaping man, that is, religion, moral forms, gastronomy, language, art, architecture, customs, traditions, etc.), depending on to reach the imaginary stability generated by miscegenation”. (My translation). |

| 26 | Tenzing Ortega, prolific designer, passed away less than four months after the performances of La Liga de la Decencia. He leaves behind a rich legacy for his work in dozens of theatrical events both in Mexico and the U.S. |

| 27 | SB 12: Relating to the authority to regulate sexually oriented performances and to restricting those performances on the premises of a commercial enterprise, on public property, or in the presence of an individual younger than 18 years of age; authorizing a civil penalty; creating a criminal offense. |

| 28 | As of the publishing of this article, Senate Bill 12 has been found unconstitutional by a federal judge. U.S. District Judge David Hittner found Senate Bill 12 “impermissibly infringes on the First Amendment and chills free speech”. Alejandro Serrano and Melhado (2023). |

References

- Abbud, Alexa Matta. 2021. Tehuanismo: La invención del imaginario de las mujeres de Tehuantepec. Designio. Investigación en Diseño Gráfico y Estudios de la Imagen 3: 86–106. [Google Scholar]

- Belliveau, George, and Graham W. Lea. 2016. Research-Based Theatre: An Artistic Methodology. Bristol: Intellect Books. [Google Scholar]

- Biography. n.d. Diego Rivera: The Complete Works. Diego Rivera Foundation. Available online: www.diego-rivera-foundation.org/biography.html (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Ceja Andrade, Claudia. 2019. Gabriela Pulido Llano, El mapa ‘rojo’ del pecado. Miedo y vida nocturna en la Ciudad de Mexico, 1940–1950. Signos históricos 21: 280–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chassen-López, Francie. 2014. The Traje De Tehuana as National Icon: Gender, Ethnicity, and Fashion in Mexico. The Americas (Washington 1944) 71: 281–314. [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedia Britannica. 2023. s.v. “Porfiriato”, last modified February 16. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Porfiriato (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Ferrera, Carlos. 2015. Utopian Views of Spanish Zarzuela. Utopian Studies 26: 366–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Eliot. 2023. University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA. Personal communication. August 17. [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield, Joanne. 2008. Imagining La Chica Moderna Women, Nation, and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1917–1936. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lander, María Fernanda. 2002. El Manual de urbanidad y buenas maneras de Manuel Antonio Carreño: Reglas para la construcción del ciudadano ideal. Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies 6: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, Kairos. 2023. Email message to author. August 23. [Google Scholar]

- Malloryk. 2021. Curator’s Choice: Aztec Eagles over the Pacific: The National WWII Museum: New Orleans. The National WWII Museum|New Orleans. September 26. Available online: https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/aztec-eagles-mexican-air-force (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Mendoza-García, Gabriela. 2016. The Jarabe Tapatío: Imagining Race, Nation, Class, and Gender in 1920s Mexico. In The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Ethnicity. Edited by Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 319–43. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, Albert L. 1971. Las elecciones de 1940. Historia Mexicana 21: 80–134. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido Llano, Gabriela. 2018. El mapa “rojo” del pecado: Miedo y vida nocturna en la Ciudad de México, 1940–1950. Primera edición. Ciudad de México: Secretaría de Cultura, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Bonilla, Laura Camila. 2023. Recristianizar para salvar. La Legión Mexicana de la Decencia como Proyecto Cultural en el Modus Vivendi. Signos Históricos 25: 122–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel, Salvador. 2023. La Liga de La Decencia. Tribuna de Querétaro. Available online: https://tribunadequeretaro.com/opinion/columnistas/solo-para-nostalgicos/la-liga-de-la-decencia/ (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Rodriguez, Fernando Almaguer, and Nancy Ricardo Domínguez. 2016. Travestismo Cultural y Mestizaje Latinoamericano: Apuntes Para Un Análisis Antropológico. Revista Alternativas 17: 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Ximena. 2021. El Día Que Anna Pavlova Se Vistió de China Poblana. México Desconocido. September 4. Available online: https://www.mexicodesconocido.com.mx/el-dia-que-anna-pavlova-se-vistio-de-china-poblana.html#:~:text=Anna%20Pavlova%2C%20una%20de%20las,Imperial%20Ruso%2C%20visit%C3%B3%20nuestro%20pa%C3%ADs (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Salinas, Fernanda. 2022. La Historia de La Diana Cazadora y Su Flecha Perdida En Cdmx. Grupo Milenio. February 12. Available online: https://www.milenio.com/cultura/diana-cazadora-historia-monumento-flecha-perdida-cdmx (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Serna Moreno, J. Jesús María. 2001. México, un Pueblo Testimonio: Los Indios y La Nación en Nuestra América. Mexico City: UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, Alejandro, and William Melhado. 2023. Texas’ ban on certain drag shows is unconstitutional, federal judge says. Texas Tribune. September 26. Available online: https://www.texastribune.org/2023/09/26/texas-drag-queen-law-unconstitutional/ (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Sluis, Ageeth. 2016. Deco Body, Deco City: Female Spectacle and Modernity in Mexico City, 1900–1939. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- The New Works Festival. 2023. Department of Theatre and Dance. University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://theatredance.utexas.edu/event/cohen-new-works-festival-2023 (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Varela, Bella María. 2023. University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA. Personal communication. August 18. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Mantecón, María del Carmen. 2000. La China Mexicana, Mejor Conocida Como China Poblana. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 22: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, Álvaro. 2020. Documental: Los Teatros del Pueblo. Clío. May 8. Video. Available online: https://youtu.be/UvugfF0nnjQ (accessed on 14 August 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).