Abstract

Among the antiquities of the archaic period of Forest-Steppe Scythia, a group of elite burials of women, possibly endowed with priestly functions during their lifetime, stands out. Until recently, only two unrobbed burial complexes were known to contain the main burials of women of high social rank, in whose graves golden costume elements were found—primarily expressive details of headdresses. The barrows (kurgans) were discovered at the end of the 19th century when amateur excavations were actively carried out on the right bank of the Dnipro. As a result of research conducted by the author at the Skorobir necropolis (in the area of the Bilsk fortified settlement, on the left bank of the Dnipro), two similar graves were recently discovered, which provided new material that significantly expanded the known geographical distribution of this phenomenon. The materials are closely analogous to the previously discovered elite female burials of the Middle Dnipro (barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka, barrow 35 near the village of Bobrytsa) and allow us to highlight a number of stable elements of the funeral costume of noble women and the sets of objects that complemented them. In this article, we consider the social and cultural significance of female attire in elite burials and delimit the chronological framework of this previously understudied phenomenon within the first half of the 6th century BCE. The new finds offer unprecedented insight into the form and meaning of one type of female headdress which researchers have tried to reconstruct for over a century.

1. Introduction

Among the burial mound complexes of the 7th–6th centuries BCE discovered in the territory of Forest-Steppe Scythia are burials of women who probably had high social status during their lifetime (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 141; Skoryi 1990, pp. 69–70; Daragan 2011, pp. 615–16; Hellmuth Kramberger 2015, pp. 152–53), as is indicated not so much by the large size of the burial chambers or the body’s central location (the burials were the main ones) but by the characteristic set of accompanying equipment as well as the features of the funeral costume. In ancient societies, funeral costume traditionally performed several functions—it reflected the worldview of the people of different regions and their aesthetic preferences and therefore presented a complex system of visual signs (Yatsenko 2006, p. 5).

The main element of the funeral costume was a headdress decorated with gold plaques of various types and gold earrings, breast jewelry in the form of beads, pendants, bracelets, and pins. The costume complex was complemented by various accessories (a mirror, a stone dish, etc.). The consistent combination of elements of women’s clothing with specially designed gold objects distinguishes such assemblages from those of other burials.

Given that a greater number of these complexes have now been excavated, and their geographic range has expanded significantly, it is possible to trace the features of this stable tradition that existed in the territory of Forest-Steppe Scythia in a rather narrow chronological range of the Scythian archaic period.

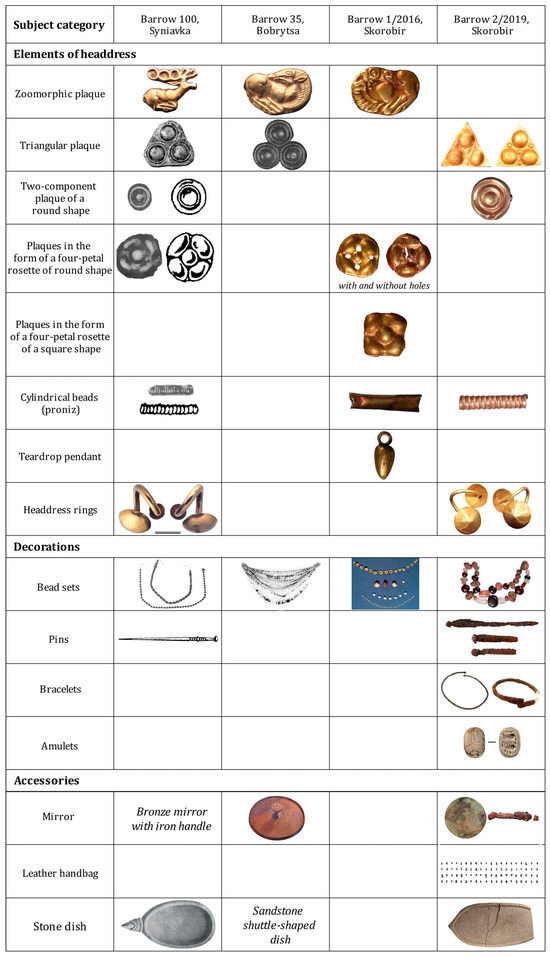

For the first time in many years, the information that was obtained in the late 19th century, and became the starting point for identifying a special group of elite female burials of the archaic period in the area of Forest-Steppe Scythia, can be supplemented with materials from new excavations carried out in the territory of the Dnipro Left Bank Forest-Steppe, in the vicinity of the Bilsk fortified settlement. Now, we can significantly expand our previous knowledge and take a fresh look at the problem of women’s headdresses. To do this, within the framework of the article, data from the last century are compared with the results of modern research. The explanations are complemented by a summary comparison table, as well as a 3D reconstruction created based on the most compelling new data about one of the headdresses.

2. Barrow Complexes with the Remains of a Funeral Costume in Materials from the Dnipro Right Bank

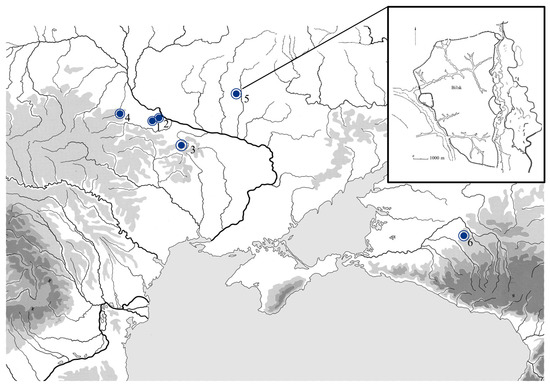

Since the main sources for studying the local population’s funeral costume are archaeological, the four barrows excavated in the territory of the Dnipro Forest-Steppe give us the most complete picture of this cultural expression (Figure 1). Two were discovered at the end of the 19th century through amateur excavations. As the integrity of their burial chambers was not violated by robbers, researchers had valuable information at their disposal for studying the features of the funeral costume of the Early Scythian period.

Figure 1.

Archaeological sites discussed in the article. 1—barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka; 2—barrow 35 near the village of Bobrytsa; 3—barrow “Repiakhuvata Mohyla”, near the village of Matusov; 4—Perepiatykha barrow; 5—Bilsk hillfort; 6—Kelermesskaya burial ground.

2.1. Kurgan 100 (Mohyla Ternovka) near the Village of Syniavka

Located in the Ros River basin, in the territory of the Dnipro Right Bank Forest-Steppe (Figure 1: 1), and excavated in the fall of 1897 by Yevhen Znosko-Borovsky (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 92; Khanenko and Khanenko 1900; Kovpanenko 1981, p. 13), the barrow was 4 m high and 93 m across; the burial chamber was a 4 × 3.5 m pit lined with wood and oriented along the west–east line. The type of wooden structure is difficult to establish due to the brief description presented in the original publication (Kovpanenko 1981, p. 67). The barrow was not robbed; however, to understand how reliable this information was, it is important to note that the bottom of the burial chamber consisted of an undifferentiated mass of black earth, sand, and wood dust due to groundwater. “The earth and wood saturated with water turned the bottom of the grave into solid mud” (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 139). This situation calls into question the usefulness of the recorded details of the design of the headdress and the funeral costume as a whole, which has already attracted scientists’ attention (Klochko 2008, p. 29); however, there is no reason to question the general accuracy of their findings.

According to published information, four people were buried in the grave, among them, three adults (two women and a man) and one child. The main burial was of a woman wearing a headdress, placed in the center of the grave with her head oriented to the west, the others were laid perpendicular to her, with their heads to the north. Thus, the dependence and subordination of the accompanying persons are established by the location of the skeletons and the objects left with them. According to Halyna Kovpanenko (1981), it is the burial of an elite woman, accompanied by a concubine with a child and a bodyguard (pp. 74–75). The high status of the buried woman was also emphasized by Yevhen Znosko-Borovsky: “Apparently, high-ranking local female persons were buried here, with all the attributes of their greatness.” He also draws attention to the fact that “only whole objects were placed in the grave, such as earrings and a gold band with gold necklaces. In the same way, the dishes are of local, ancient types” (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 141). Furthermore, data are presented on the location of the gold plaques on the skull, which, according to the author, had been recorded accurately (p. 140). These locations later served as a powerful argument to justify various possible options for the appearance of the deceased’s headdress. Other details recorded during excavations also turned out to be important for the reconstruction of the funeral costume. Thus, the published text not only indicates the location of various decorations but also describes the appearance of the gold plaques and notes their number for different types: 11 in the form of “circles,” 31 in the form of “deer plaques.” It is important, for example, to observe that a gold nail-shaped pin (Figure 2: 1, e) lay under the skull, and two nail-shaped spiral pendants of gold (Figure 2: 4) were at the temples, and it was noted that they were on a headband (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 140). There were three necklaces on the buried woman’s neck: one of 24 gold plaques in the form of rosettes, the second of 14 gold piercings alternating with 14 gold round plaques, between which there were three beads made of rock crystal and one of carnelian (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 140, Figure 71); the third consisted of 26 beads made of semi-precious stones and glass and 84 faceted amber beads (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 140, Figure XVII: 8, 10; Kovpanenko 1981, p. 51, Figure 41: 5–16). In the first publication of the materials, drawings were also included to give a general idea of the jewelry set related to women’s funeral costumes (Figure 2: 1). The information about certain accessories (a stone dish and a bimetallic mirror) is also important. While these objects were found near another female skeleton, they undoubtedly related to the tradition of leaving such objects in women’s graves.

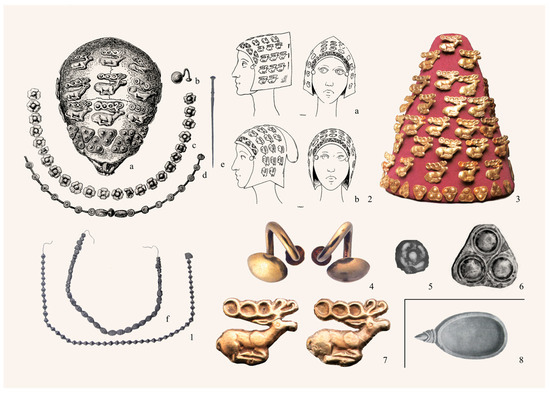

Figure 2.

Funeral complex of barrow 100 Syniavka. 1—objects found during excavations: a—location of gold plaques on the skull; b—gold earring; c—gold plaques in the shape of a rosette; d—necklace made of gold piercings and beads; e—gold pin; f—necklace. 2—appearance of the headdress after the reconstruction of Tetyana V. Miroshina. 3—appearance of the headdress after reconstruction by Liubov S. Klochko. 4—gold earrings. 5—golden plaque in the shape of a rosette. 6—gold triangular plaque with three inscribed circles. 7—zoomorphic golden plaques. 8—stone dish. 1, 5, 6, 8—after Khanenko and Khanenko (1900), Bobrinskoy (1901), Yatsenko (2006), Hribkova (2014). 2—after Miroshina (1977). 3, 4, 7—after Reeder (2001). 4—after Klochko et al. (2021).

Based on the presence of rare forms of molded pottery in the grave and the absence of Greek imports, the head of the excavations dated the burial to the Cimmerian period, 10th–9th centuries BCE, though Alexey Bobrinskoy did not agree, attributing it to the later, Scythian period (Bobrinskoy 1901, pp. 140–42). Halyna Kovpanenko placed this complex among the antiquities of the 6th century BCE, proposing a date in the first half of the century (Kovpanenko 1981, p. 130). Recently, various attempts at dating the barrow have been proposed in the scientific literature; it is attributed either to the second half of the 7th century BCE (Daragan 2010, pp. 106–8; Daragan 2011, p. 615) or to the first half of the 6th century BCE (Makhortykh 2019, p. 356). The latter date, in our opinion, is more convincing since it is consistent with the materials of our excavations. In addition, a bronze mirror with an iron side handle found in the barrow1 (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 140; Kovpanenko 1981, p. 114) indicates the possibility of attributing the complex even to the second quarter of this century.

2.2. Kurgan 35 near the Village of Bobrytsa

Kurgan 35 is located in the Ros River basin, in the territory of the Dnipro Right Bank Forest-Steppe (Figure 1: 2), and was excavated at the end of the 19th century by Yevhen Znosko-Borovsky (Kovpanenko 1981, p. 13). Znosko-Borovsky’s diary, published after his death by Alexey Bobrinskoy (1901, p. 92), contains basic information about the barrow. At the time of excavations, the barrow was 5 m high. Though they recorded traces of looting, they did not reach the grave (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 112), which allows us to trace the features of the funeral rite. The burial took place in a square pit of 5.6 × 5.6 m and 2.8 m deep. The burial chamber was a wooden crypt with five supporting pillars for the ceiling and a gently sloping entrance (6 m long dromos) on the south side. It was a double burial, as the excavator reports: “At the bottom of the grave there were two buried people lying in an extended position on their backs. The primary body was in the center and was turned with its head to the west, while the body which accompanied it lay at the northern wall, perpendicular to the main body, with its head to the south” (Kovpanenko 1981, p. 13). The main burial was female. Elements of the funeral costume, primarily the headdress, have been recorded. “On the forehead of the main buried person, which was preserved, lay a bandage composed of two types of gold plaques: along the bottom of the forehead there were 15 gold plaques in a row, each composed of three circles. Above them—but in what order, it is difficult to say—lay plaques with the image of a recumbent horse, with its legs bent under itself and its head bent onto its back. There are 19 such plaques. All of them are stamped on one side” (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 113). Two necklaces were found in the chest area:2 the upper one consisted of 32 beads made of carnelian, topaz, agate, rock crystal, and chrysolite; the lower one consisted of 40 beads of various shapes and combinations, including two large amber beads that were heavily burned. By the right shoulder, there was a cluster of small beads forming a set three meters long. A charred wooden quiver covered with leather was found to the right of the skeleton, containing 21 bronze arrowheads with “hooks”; nearby lay a bronze ring and poorly preserved iron fragments. To the left of each buried individual was a bronze mirror with a central handle (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 113, Figure 62). The excavators made other observations that are significant in reconstructing the appearance of the headdress. For instance, the diary entries note that “some of the plaques were inside one another, it is likely that the material to which they were affixed had burned and curled the plaques as a result. There are no holes for sewing on the plaques, no lobes, and no traces of soldering are visible, and therefore we can only assume that these plaques were either glued or that each was covered with a fabric border and attached separately. An elegant mirror, precious necklaces, whitewash and rouge cannot be recognized as belonging to the second structure” (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 114).

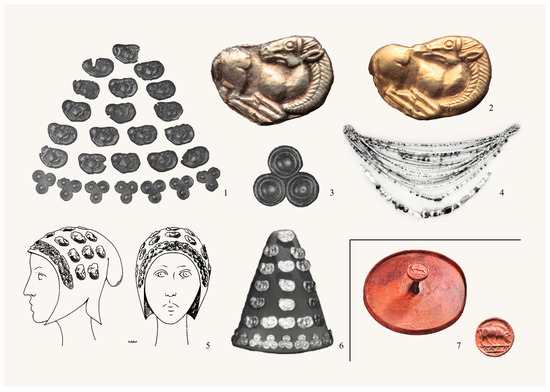

The dating of the complex is determined by the burial goods: first of all, a bronze mirror with a central handle (Figure 3: 7), a stone dish, and some types of sewn-on plaques that have a fairly wide range of analogies (Kovpanenko 1981, pp. 113–14; Skoryi 1990, pp. 59–62; Fialko 2006, p. 67, Figure 3; Kuznetsova 2018, pp. 453–54; Makhortykh 2019, p. 354), allowing us to date the burial between the end of the 7th and the first half of the 6th centuries BCE.

Figure 3.

Funeral complex of barrow 35, Bobrytsa. 1—gold plaques—headdress decorations. 2—zoomorphic golden plaques. 3—gold triangular plaque in the form of triple circles. 4—necklace. 5—appearance of the headdress after the reconstruction of Tetyana V. Miroshina. 6—appearance of the headdress after reconstruction by Liubov S. Klochko. 7—bronze mirror with an image of a boar on the central handle. 1, 3—after Khanenko and Khanenko (1900). 2, 7—after Reeder (2001). 4, 6—after Klochko (2012). 5—after Miroshina (1977).

2.3. Kurgans near the Villages of Perepyatykha and Matusov

Some materials for the reconstruction of women’s headdresses of the archaic period came to light in the excavations of two barrows: Repiakhuvata Mohyla (the village of Matusov) and Perepiatykha in the Dnipro Right Bank, in the Tyasmin River basin (Figure 1: 3–4). In one of them (Repiakhuvata Mohyla, tomb 1), a different, simpler type of headdress is attested, although complemented by temple ornaments in the form of nail-shaped spirals and bronze nail-shaped pins (Illinska et al. 1980, pp. 35, 39; Klochko 2008, p. 24). In the Perepyatykha barrow, according to researchers, there is no certainty that the elements of the costume (silver and gold appliqué plaques, plates, earrings) belong to the same set. However, the fact that the buried person was of the highest nobility is not disputed (Skoryi 1990, pp. 12, 69–72; Klochko 2008, pp. 27, 35–36; 2012, pp. 423–24), although in both cases, the female burials were not the primary ones. In addition, gold appliqué plaques and gold plates carved along the contour of the griffin figure were found not in the area of the skull of the woman’s skeleton (bone no. 4) but near the broken clay vessel with cremation remains, located near her feet (Skoryi 1990, p. 12). It is also possible that these appliqué plaques were used to decorate a vessel (Daragan 2010, p. 88). Thus, the most complete and fairly well-described (for their time) complexes should be recognized as the two barrows excavated by Yevhen Znosko-Borovsky.

3. Interpretation of Excavated Materials

The information obtained through excavations offered a fairly complete picture of the funeral rites of elite female burials in Forest-Steppe Scythia and allowed us to propose various reconstructions of headdresses as the main element of the funeral costume.

When studying archaeological sources, one of the most important methodological approaches remains typology. Typological classification allows us to identify the main decorative elements, consider options for their combination, and trace the stable tradition of decorating headdresses as the main part of women’s funeral costume in a certain territory in a relatively short period of time, namely, in the first half of the 6th century BC.

3.1. Social Status of the Buried

One of the first who drew attention to the similarity of these two archaeological complexes was the original excavator, who emphasized that representatives of the local aristocracy were buried in them (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 20). The identification of the buried with the local elite, according to researchers, was indicated by the size of the barrow and graves, the presence of dependent persons, the wealth of grave goods, the abundance of jewelry, and a headdress decorated with gold plaques (Miroshina 1977, p. 87; Klochko 2008, p. 35; Daragan 2010, p. 108). The semantics of images of horned animals (deer, mountain goat) depicted on gold plaques are associated with the military class in the Iranian world (Vertiienko 2018, pp. 422–23). In this regard, it seems significant that in one of the graves, there were weapons (a quiver, a bow with arrows) and a horse skeleton, which are likely the attributes of noble female priestesses associated with the cult of the warriors and are likely endowed with the special powers of this warrior deity (Vertiienko 2018, p. 423)3. If this is the case, they were not Amazon warriors, as Yevhen Znosko-Borovsky assumed (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 114)4. It has also been suggested that images of a deer or mountain goat could serve as unique markers, indicating that the buried women belonged to specific social groups (Hellmuth Kramberger 2015, p. 153).

Other appliqué plaques, in the form of triangles with circles inscribed in them (Figure 2: 6), as well as triple circles cut along the contour (Figure 3: 3), were apparently a more common decorative element. Such plaques are widespread in the early Scythian period on various objects, including funeral dishes and clothing (Miroshina 1977, p. 89; Fialko 2006, pp. 64–65; Daragan 2010, pp. 87–91).

3.2. Reconstructions of Headdress

The fairly detailed description of the burials, together with the location of the finds, the available sketches of their appearance (Figure 2: 1 and Figure 3: 1–4), as well as the publication of photographs of the rarest items (Khanenko and Khanenko 1900), provided reliable data on the overall quantity and types of jewelry (Bobrinskoy 1901). In combination, this evidence served as the basis for several reconstructions of female funeral headdresses in Forest-Steppe Scythia.

According to the initiator of the excavations, the women buried in barrows 100 near the village of Syniavka and 35 near the village of Bobrytsa wore headscarves or headbands, which were fastened at the back of the head with a pin (Bobrinskoy 1901, pp. 138–40). While the version presented in the scientific literature of the beginning of the last century (Rostovtsev 1925, pp. 494–95) looked quite convincing, Varvara Illinska and Oleksii Terenozhkin (Illinska and Terenozhkin 1971, p. 144) later suggested low tiaras decorated on the front with gold plaques. Tatyana Miroshina (1977) subsequently tried to make some clarifications to the existing interpretations. Paying attention to the size of the gold plaques and their location, the researcher proposed two possible options for the appearance of female funeral attire (Figure 2: 2 and Figure 3: 5), defining them as caps reminiscent of those worn by the Saka (Miroshina 1977, pp. 83–86, Figures 8–9)5. According to Liubov Klochko (2008, p. 29), the author of the latter reconstruction based her proposal only on the drawing given in Alexey Bobrinskoy’s publication, due to the lack of other field documentation. In addition, the visibility of the zoomorphic images on the plates was not taken into account, since the golden elements should have been perceptible above all on the front side of the ceremonial headdress, demonstrating that the woman belonged to a certain social circle. To ensure clear visibility, the headdress should be reconstructed in a different shape altogether, including a more rigid base (Klochko 2008, p. 30). Sergey Yatsenko also criticized Tatyana Miroshina’s reconstructions (Yatsenko 2006, p. 53), noting that headdresses such as caps or kerchiefs have no analogies in the societies of ancient Iranians, and the combination of a felt cap (bashlyk) with temple pendants and a pin on the back of the head requires additional proof.

In developing possible options for the appearance of women’s headdresses, almost all researchers have proceeded from the fact that the gold appliqué plaques found in both barrows did not feature through holes for sewing or loops on the reverse that were usual in later periods. The lack of fastening devices made it possible to inquire about the material from which the headdress was made, as well as the technique of attaching gold elements, which may have involved the use of adhesive solutions (Miroshina 1977, pp. 79–80; Kovpanenko 1981, p. 116; Skoryi 1990, pp. 42–43). This technique may indeed be characteristic of the Early Scythian time (Klochko 2008, p. 27).

For the manufacture of ceremonial headdresses, felt was most likely selected, while triangular plaques could be attached to a forehead band. Yet the use of other, alternative materials cannot be ruled out (Miroshina 1977, pp. 79–80). Sergey Yatsenko also considers the variant of the headband more acceptable for the archaic period (Yatsenko 2006, pp. 53–54). In the case of the headbands that Alexey Bobrinskoy reportedly discovered on the skulls of women (1901, pp. 113, 140), despite the lack of a clear record of finds in the water-filled burial of kurgan 100 near the village of Syniavka, and in the fire-ravaged grave in barrow 35 near the village of Bobrytsa, some recurring patterns in the combination and number of individual elements of the costume can be traced, since both burial complexes had escaped previous looting. We can, to a certain degree of certainty, assume that the gold earrings found in the skull area (Figure 2: 1, b and Figure 4), the gold pin (Figure 2: 1, e), and the set of triangular plaques from kurgan 100 near Syniavka could have come from a headband decorated with patches of appliqués in the shape of triangles. The idea of decorating items with juxtaposed rows of triangular plaques with three sets of concentric circles can be seen on other items from burials of the Early Scythian period. For example, the neck and shoulders of a black-polished pot found in a barrow near the village of Hlevakha were decorated with similar plaques, arranged in one row and grouped in threes, which formed a pattern of triangles with multidirectional (up and down) vertices (Terenozhkin 1954, pp. 95–96; Fialko 2006, pp. 61–62, 64, Figure 2). The earlier burial complex of Kleinklein (Austria) contained a bronze face mask with a forehead band decorated with multidirectional triangles (Fialko 2006, pp. 70–72, Figure 5). In view of this find, it seems likely that this motif, possibly associated with the idea of masculinity and femininity, is of Western origin and that its popularity in the territory of Forest-Steppe Scythia in the early Scythian period was due to the strong influence of the Hallstatt culture circle on the local population. Local people not only borrowed the idea of using the individual elements in the decoration (triple triangles) but also included them in the semantics of funeral rituals, employing them in the design of burial items in the funeral set of persons of high social rank, primarily women who belonged to the priestly class (Fialko 2006, p. 69; Daragan 2010, pp. 108–9; 2011, p. 615; Hellmuth Kramberger 2015, p. 152).

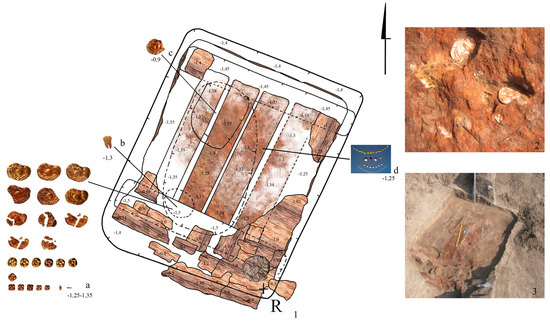

Figure 4.

Kurgan 1/2016. Skorobir Necropolis. 1—general plan of the burial indicating the location of the costume elements. a, c—gold elements. b—human tooth. d—beads. 2—gold plaques, recorded during the clearing of the burial. 3—general view of the burial. Drawing and photograph by Iryna B. Shramko, Stanislav A. Zadnikov.

Probably, triangular plaques with impressed concentric circles or in the form of three triple circles were associated with solar cults (Illinska 1971, pp. 73–79)6. However, they still cannot be considered “a characteristic element of the ceremonial headdress of the archaic type” (Miroshina 1977, p. 89), since they were used more widely for decorating clothes and vessels. Nail-shaped spiral temple ornaments (Figure 2: 4), in this case, could be attached to the headband. They are made of round gold wire, to which two shields of different diameters are attached (Klochko et al. 2021, p. 29). Since such earrings were found only in female burials, they could serve as a kind of ethnocultural marker of the costume of a certain region (Klochko 2007, pp. 87–89; 2008, p. 24).

In barrow 35 near the village of Bobrytsa, triangular plaques in the form of stacked concentric circles could have been used differently, for example, in combination, in the decoration of a hat or headscarf, as indicated by the absence of earrings and a pin near the head in the grave, although the latter could have fastened a hairstyle rather than a headband.

The authors who studied the materials of these archaeological complexes came to a consensus that, in both cases, the gold decorative elements could have been used to decorate various headdresses: a headband decorated with applied triangular plaques glued to the base, a hat decorated in the Scythian animal style; at the same time, the use of a headscarf is not excluded (Miroshina 1977, p. 85; Klochko 2008, p. 26). Thus, it can be assumed that, in each barrow, three types of headdresses (headband, headscarf, and cap) could have been worn together (in any possible combination) as a social and ethnocultural marker of women’s costume, although the presence of a headscarf or veil is archaeologically difficult to substantiate (Klochko 2008, pp. 26–28). In any case, the three elements can be considered as a kind of “ensemble,” a unified whole, indicating the high position of a woman in society, who had a priestly status during her lifetime; however, such compositions are not reflected in the reconstructions proposed by the previous authors (Figure 2: 2, 3, and Figure 3: 5, 6).

Having considered all possible options for women’s headdresses of the archaic period (headbands, headscarves, and hats), Liubov Klochko concluded that the most plausible option is a high conical hat (Klochko 2008, pp. 29–33) covered with a cape (Klochko 2012, pp. 417–26). This type of headwear reflected the Scythian tradition of producing hats that had a special sacred meaning (Klochko 2008, pp. 30, 34–35, 37). In a later period, conical hats were traced in a wider range of archaeological material (Klochko 1986). Researchers of the Saka archaeological culture came to the same conclusion when studying the headdress from the Issyk mound, drawing attention to the convergence of this phenomenon across a large geographical area (Akishev and Akishev 1980). The size and shape of the headdress in each individual case were determined by the number of gold plaques and their sizes. We should point out that Liubov Klochko assessed the specific options for placing gold elements on a hat of this shape based on their presentational role in the design of ceremonial funeral attire (Figure 2: 3 and Figure 3: 6). For instance, a hat from barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka could have a height of 30 cm, and the one from barrow 35 near the village of Bobrytsa 20 cm (Klochko 2008, pp. 32–33). Gold appliqués attached to the base of the conical hat, conveying the image of a recumbent deer or mountain goat with its head turned back, not only emphasized the shape of the front part of the headdress but also carried considerable semantic load as solar symbols (Klochko 2008, p. 34; Hribkova 2014, p. 102) comparable to the triangular plaques made of stacked circles (Hribkova 2012, p. 148). The zoomorphic images (mountain goat, deer with legs drawn up) in the decoration of the headdresses discussed above emphasize the Iranian connections in the funeral costume of the population of Forest-Steppe Scythia, which should be associated with broader cultural affiliations among the nomadic Scythians (Klochko 2008, p. 37; Toleubaev 2016, p. 853; Andreeva 2018, pp. 119–20, Figure 2.38).

3.3. Other Elements of the Funeral Costume and Accessories

Twenty-four gold plaques in the form of four-petalled rosettes were found during the excavations of barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka. They may have decorated the collar of the funeral dress, since they were located in the neck area, above necklaces with beads made of amber and semiprecious stones. As in the examples discussed above, the construction of the plaques suggests that they may have been glued to the fabric (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 140).

The costume was complemented by chest ornaments—necklaces made of gold plaques and beads, as well as pins that could be used to secure hairstyles or headscarves but likely not to clothes. These items could have served as a kind of amulet or indicator of belonging to a certain social group or clan (Klochko 2008, p. 25). The necklaces, which included beads made from semi-precious stones, rock crystal, amber, and paste, undoubtedly had a special semantic meaning. The selection of beads and their combination in the necklace were obviously not random. As in the other elements of the costume, the deliberate selection of the items is clear first and foremost from their arrangement, which was determined less by the external characteristics of the products than by their protective properties as a kind of amulet (Miroshina 1977, p. 24).

Among the accessories of the female funeral set were, in almost all cases, two main attributes: a bronze or bimetallic mirror and a stone dish. Both items belong to the category of ritual cult objects, placed more often in women’s than in men’s graves; they could be located either near the head or next to the body of a person (Kuznetsova 2002, p. 9; Makhortykh 2019, pp. 347–48).

In general, the traditional funeral costume of noblewomen with priestly functions in Forest-Steppe Scythia was characterized by a number of stable features of both the burial itself, the accompanying equipment, and the funeral costume. Its obligatory attribute was a headdress decorated with gold elements, which probably reflected the specific functions of a woman in the sacred sphere, perhaps indicating a local ethnocultural feature or affiliation. In addition to the type of headdress appropriate to their status, the standard set for persons of this rank probably included breast decorations in the form of necklaces made of amber, semi-precious stones, paste, and even gold elements. Bracelets and pins could also be included in the set. The collar of the dress may also have been decorated with gold plaques. The funeral ensemble also regularly included a mirror and a stone dish, possibly intended for use as a palette.

4. The Funeral Costume Complex in the Materials Discovered in the New Excavations at the Skorobir Necropolis

The burial ground is located on the left bank of the Sukha Hrun River (a tributary of the Psel River), to the west of the ancient settlement, and is one of its largest necropoleis. The first barrows were excavated back in 1906 (Gorodtsov 1911). Subsequently, more than 20 barrows of different periods were studied, with burials of the Early Scythian era predominating (Shramko 1994, p. 102; Makhortykh 2013, pp. 223–24).

4.1. General Information about the Bilsk Hillfort

The settlement is located on a watershed plateau between the rivers Vorskla (left tributary of the Dnipro) and Sukha Hrun (right tributary of the Psel). It is known as the largest fortified settlement of the early Iron Age in Europe, the seat of a tribal union, and an important craft, trade, and political center of Forest-Steppe Scythia (Shramko 1987). Materials from long-term excavations indicate the complex ethnic and social composition of the population that inhabited the site (Boiko 2017). Most scientists consider it possible to identify the Bilsk hillfort with the city of Gelon, described by Herodotus (4.108) (Havrysh and Kopyl 2010).7 The settlement was founded between the last third and the end of the 8th century BCE by settlers from the right bank of the Dnipro, bearers of the Middle Hallstatt Basarabi culture (Shramko 2006; Shramko 2021). Objects from the early Scythian cultural complex appear in cultural deposits of the last quarter to the late 7th century BCE, and especially the first half of the 6th century BCE. Among the most expressive of these are bone and antler objects decorated in the formal idiom known as the “Scythian animal style” (Shramko et al. 2021). The features of Scythian material culture stand out clearly against the general background of remains left by the local sedentary population. This population continued to maintain contact with the circle of Hallstatt cultures (Shramko and Zadnikov 2021), the western regions of the Forest-Steppe, and the Greek centers of the northern Black Sea region, with which they began trading as early as the third quarter of the 7th century BCE (Shramko 2021, pp. 192–94; Zadnikov and Shramko 2022, pp. 882–85).

4.2. Research of Barrows in the Southern Part of the Necropolis

During the study of the barrows in the southern part of the burial ground, two female burials were recently discovered, containing elements of the funeral costume of the local elite.8

Burials of women of high social rank are quite rare. Thus, in the many years of research on this burial ground, only a few examples of gold objects or imported prestige items have come to light, indicating the special status of the buried person (Shramko 1994, pp. 103, 107). Of the 11 archaic period barrows we excavated, decorative elements of funeral headdresses were found in three, and two used gold plaques of various types.

4.2.1. Kurgan No. 1/2016

One burial dating back to the Early Scythian period was discovered in this barrow (Shramko 2017, p. 368; Shramko and Zadnikov 2017, p. 47). The burial chamber was a wooden crypt with plank flooring (Figure 4). The wooden structure was damaged during looting in antiquity; however, we can get an idea of its former appearance from the fragments of decayed wood found in the chamber. Most likely, the floor had been covered with thick boards, and the ceiling was supported by three rows of logs of medium thickness on which three ceramic vessels had been placed (Shramko 2017, pp. 371–72). Despite the severe destruction of the grave and the absence of bone remains, more than 30 gold plaques, one piercing, and a pendant were discovered where the skull must have been placed, based on the find spot of the teeth which were preserved. The gold plaques were of different types. Some were stamped with a full-figured image of a recumbent mountain goat with its head turned back, while others had four-petalled rosettes (Shramko 2017, pp. 375–76, Figure 7: 1–5). Since the elements of the funeral costume, especially the headdress, were incomplete, it is difficult to offer a convincing reconstruction. However, this funeral complex can undoubtedly be correlated with the previously discovered elite female burials from the Dnipro Right Bank Forest-Steppe discussed above, particularly with barrow 35 near the village of Bobrytsa.

Headdress Details

Gold appliqué plaques with a full-figure image of a recumbent mountain goat with its head turned back (Figure 5: 1) were found at the bottom of the grave, in the area of the skull. The intact specimens (4 pieces overall) were 3.6 cm long, 2.5 cm high (or wide), and 0.01 cm thick (Shramko 2017, p. 375). Several items were found in the fill of the tomb (19 fragments). The plaques were made of thin gold sheets, the images stamped on a relief matrix with the figured emblems oriented to the left. The quality of the impression differs among the plaques. Similar headdress elements are quite well known in the territory of Forest-Steppe Scythia (Illinska 1968, p. 38, pl. XXIV: 22; Illinska 1971, p. 75, Figure 2; Kovpanenko 1981, p. 13, Figure 10; Bandrivsky 2010, pp. 151–54, Figure 6). Most of them were found in the barrows of the Middle Dnipro region, on both the right and left banks of the Dnipro, outlining the boundaries of their distribution area. What is important for us is that such plaques were part of a set of decorative elements of a woman’s funeral costume discovered in barrow 35 near the village of Bobrytsa (Figure 3: 1–2), where they were probably also associated with the design of the headdress.

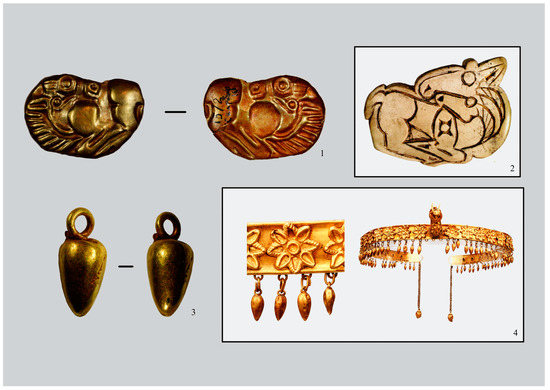

Figure 5.

Elements of a funeral costume from barrow 1/2016 of the Skorobir necropolis. 1–4—gold plaques. 5—golden thread. 6—gold pendant. 7—amber beads. 8–9, 11–12—beads made of glassy mass (paste). 10—golden glass beads. Drawing and photograph by Iryna B. Shramko, Stanislav A. Zadnikov.

The scientific literature justifiably takes the view that this series of plaques depicts not horses but mountain goats (Vynohrodska 2000, pp. 17–23, etc.). In our opinion, the Skorobir specimens are somewhat different from others, representing one of the variants of this motif (Shramko 2017, p. 376). On the front and back sides of the plaque (Figure 6: 1), one can see a paired image (two eyes and two ears are clearly visible), bringing it closer to the idea conveyed on the plate from barrow no. 2 near the village of Zhabotyn (Figure 6: 2) in the Middle Dnipro region (Viazmitina 1963, pp. 158–69, Figure 4). However, this is only one way of interpreting the image, since there are other possibilities (Polidovych 2017).

Figure 6.

Golden elements of the headdress from barrow 1/2016 and analogies to them. 1—zoomorphic golden plaque. 2—bone plaques from mound 2 near the village of Zhabotyn. 3—gold pendant. 4—gold pendants on a diadem from barrow 3/III Kelermesskaya. 1, 3—after Iryna B. Shramko. 2—after Lifantii and Strelnyk (2021). 4—after Alekseev (2012).

Six plaques in the form of a four-petal rosette, measuring 1.3 × 1.3 cm, have a rounded outline (Figure 5: 2), with the edges of the petals forming a solar diamond-shaped sign. Four holes, 0.15 cm in diameter, cm were punched through the edges, allowing it to be attached to a backing. One of the plaques (Figure 5: 3) had no holes. Comparable gold appliqué plaques in the shape of a four-petal flower (Figure 2: 1, c and Figure 2: 5) were found in barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka, in the Middle Dnipro region (Khanenko and Khanenko 1900; Kovpanenko 1981, pp. 51–52, Figure 41, 7). Kurgan no. 1/2016 also produced five plaques in the form of a stylized flower of square shape with petals worked in relief (Figure 5: 4). Like some of the examples discussed above, they do not feature holes. Three plaques measure 1.2 × 1.2 cm, the other two 1 × 1 cm. We recently discovered similar plaques, also without holes, in a female burial from the first quarter of the 6th century BCE in barrow 1/2021 in the Skorobir necropolis (Shramko 2023, p. 182, Figure 9: 1–8).

Similar gold items were also found in the burial complexes of Psel region: in barrow 13 near the village of Popivka and barrow 1 near Gerasimovka (Illinska 1968, p. 60, pl. LII, 17–25; p. 55, pl. XLV, 33; 1971, p. 75, Figures 2, 17, etc.).

Among the elements of the headdress in barrow 1/2016 of the Skorobir necropolis were two-part drop-shaped pendants made from a smooth gold sheet, one of which (Figure 5: 6), weighing 0.12 g, was found during the excavations (Shramko 2017, p. 377). The junction of the two parts is clearly visible, and one features a soldered-on loop-shaped wire eyelet (Figure 6: 3) of 0.8 cm long and 0.3 cm wide, while the soldered eyelet is 0.15 cm in diameter. Similar pendants were found as part of a golden diadem in the royal barrow 3III of the Kelermesskaya burial ground in the Kuban, which was decorated with a griffin (Galanina 1977, p. 186, 227–28, Table 30; Alekseev 2012, p. 105). The pendants are not only similar in appearance but show the same dimensions and manufacturing techniques. This may indicate a single production center and the same pattern of use of this gold element in the funeral costume. The hollow pendants found in barrow no. 1 of the Novozavedennoe-II burial ground in the Kuban (Maslov and Petrenko 2021, pp. 80, 90, Figure 1: 2) were similar, but slightly different in shape (conical) and manufacturing technique (rolled from gold foil with a soldered lid and loop). It can also be noted that among the numerous gold pendants of various types found during the excavations of the Artemision at Ephesus, similar teardrop-shaped specimens came to light (Pülz 2009, p. 70, 149, Taf.18, kat. 148).

The woman buried in the Skorobir necropolis could also have worn a headband with gold drop-shaped pendants, or the pendants may have been attached to the edge of a conical cap. This design of the headdress, along with the use of appliqué plaques in the form of rosettes, may be associated with a West Asian tradition (Maslov and Petrenko 2021, pp. 80–81). In any case, such golden decorative elements indicate a connection with the Caucasus, where jewelry workshops serving nomads could have existed, as well as an Eastern tradition mainly expressed in the design of this headdress. It is important to note that in the territory of Forest-Steppe Scythia, for the Early Scythian period, such an element of headdress decoration as a drop-shaped pendant is not yet known.

Plaques decorated in the animal style had a sacred meaning, and women of high social rank whose headdresses were decorated with such plaques may have been priestesses, belonging to the elite strata of society.

Chest Decorations

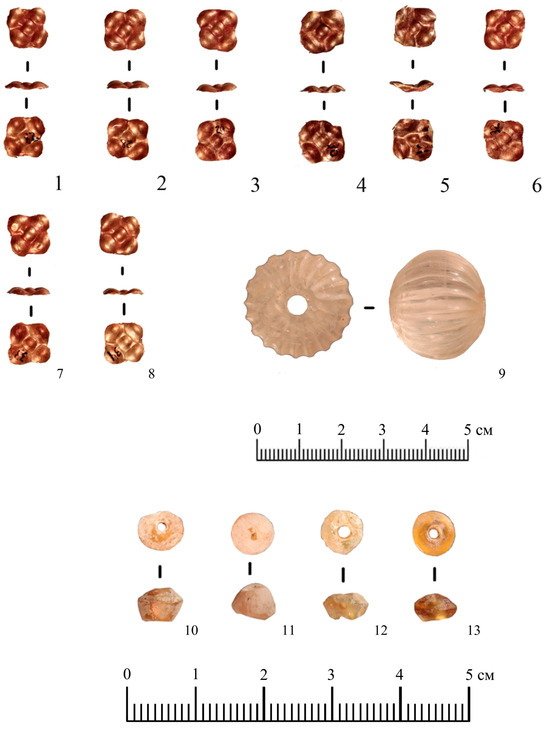

The funeral costume was complemented by necklaces of beads made from semi-precious stones, amber, opaque golden glass, and paste (Figure 5: 7–12). Based on an analysis of the entire set of burial goods, we dated the burial to the first quarter of the 6th century BCE (Shramko 2017, p. 378). The basis for dating was, firstly, the golden-colored biconical glass beads (Figure 5: 10). This type of bead is well known from the materials of the Yagorlyk settlement and was probably made in local, northern Black Sea workshops (Kolesnychenko et al. 2019, pp. 25–26; Kolesnychenko 2022, p. 54), from where they could have come to the Bilsk hillfort. Biconical beads made of translucent yellow glass were also found in the fill of a dugout constructed in the first quarter of the 6th century BCE on the Western fortification of the settlement (Shramko et al. 2021, p. 369, Figure 11: 8). Further examples of this type came to light in the female burial of barrow no. 1/2021 in the Skorobir necropolis (Figure 7: 10–13) (Shramko 2023, p. 182, Figure 9: 10–13), along with a grooved bead made of rock crystal (Figure 7: 9) and eight gold square appliqué plaques (Figure 7: 1–8) similar to those found in barrow no. 1/2016 (Shramko 2017, Figure 7: 4–5).

Figure 7.

Decorations of a funeral costume from barrow 1/2021 of the Skorobir necropolis. 1–8—gold plaques. 9—rock crystal bead. 10–13—golden glass beads.

The variety of gold elements discovered in barrow 1/2016 attests to the complexity of the funerary headdress. Various decoration techniques were used in its production, since some plaques with perforations were sewn onto their support, while others were glued. The presence among the gold items of a drop-shaped pendant with a soldered loop and a piercing tube may indirectly indicate that the headdress included a forehead band. But alternatives cannot be ruled out, since the teardrop-shaped pendant could have been attached to the edge of a conical cap or been part of an imported gold headdress, perhaps a crown, brought to the settlement by nomads. Since the barrow was almost completely robbed in antiquity, it is difficult to offer a graphic reconstruction of this part of the costume. We can only say that all the gold jewelry belonged to the headdress and that the ceremonial funeral costume was complemented by a necklace made of various beads.

4.2.2. Kurgan No. 2/2019

This barrow occupies a special place among others studied in recent years because it was not robbed. All the objects left in the grave at the time of the burial remained in situ, which makes it possible to trace the peculiarity of the funeral rite. The barrow is tentatively dated to the second quarter of the 6th century BCE (Shramko and Zadnikov 2020, p. 10), perhaps even the middle of the century. The basis for proposing this date was a bronze mirror with an iron handle, a stone dish, a quiver set, parts of a horse bridle, and other objects that have analogies among other finds of this period (Illinska 1968, pp. 41–45; Kuznetsova 2018, p. 452, Figure 5; Makhortykh 2019, pp. 352–56; Andruh and Toschev 2022, pp. 411, 413–14, etc.).

In antiquity, the barrow had a diameter of about 15 m; its original height cannot be established, since at the time of excavation, the kurgan was almost completely plowed by farmers. The burial chamber had a sub-square plan, with dimensions of 4.8 × 4.5 m (Figure 8: 1). In some areas at the bottom, remains from the floor were preserved; parallel grooves for logs that served as a basis for the wooden structure can be traced along the northern and southern walls. The grave was covered with massive logs (average diameter about 0.3 m), laid perpendicularly in three rows.

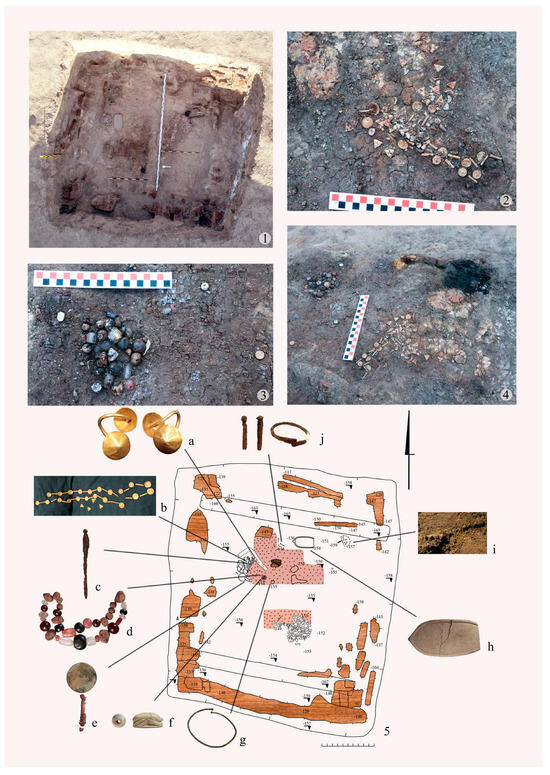

Figure 8.

Kurgan 2/2019. Skorobir Necropolis. 1—general view of the burial. 2–4—details of the funeral costume and a mirror in the process of being cleared. 5—general plan of the burial indicating the location of elements of the costume and accessories. a—earrings. b—forehead decoration. c, g, j—pins and bracelets. d—necklace. e—mirror. f—earthenware beads and piercings. h—stone dish. i—remains of a leather handbag. Drawing and photograph by Iryna B. Shramko, Stanislav A. Zadnikov.

The burial contained the partial remains of the skeleton (only the crushed skull bones and decayed pelvic bones were preserved) of one person, who was laid outstretched on their back, with the head oriented to the west. The bones had almost completely decayed, since the grave was not deep and the wooden ceiling had collapsed.

The set of objects left on and near the body of the buried person, as well as the location of the skull and pelvic bones, suggest that a young woman was buried in the grave, perhaps a teenager given that her reconstructed height amounted to only 1.3–1.4 m. A set of pots, clay spindle whorls, a sandstone dish, and a mirror were intended for the deceased. The weapons and parts of a horse’s bridle found in a compact arrangement in the southeastern corner of the grave (Figure 8: 1) can be interpreted in different ways. Either they emphasized the special status of the buried woman or they were associated with another, symbolic burial (cenotaph) of a man in the open area to her right, possibly a relative of the deceased who had died in a foreign land. Since the “military kit”—consisting of an akinakes, spear, quiver, and bronze arrows in addition to the horse bridle—was deposited at some distance from the body, it is impossible to interpret the burial we discovered as the grave of an armed woman, or Amazon, which, according to Elena Fialko, was buried with personal weapons (Fialko 2023, p. 22).

Elements of a Funeral Costume

All items that could be related to the design of the ceremonial costume were found on or around the buried woman’s skull, chest, and hands (Figure 8: 5). There was a bronze bracelet, located where the woman’s right hand most likely lay (Figure 8: 5, g; Figure 9: 11). To the left of the almost completely decayed skeletal remains, level with the pelvic bones, were two iron pins and a bracelet (Figure 8: 5, j). To the right of the skull was a bronze mirror with an iron handle (Figure 8: 5, e). Another iron pin was found between the mirror disk and the skull (Figure 8: 5, c and Figure 9: 1, 3). In the chest area, there was a cluster of beads (Figure 8: 5, d).

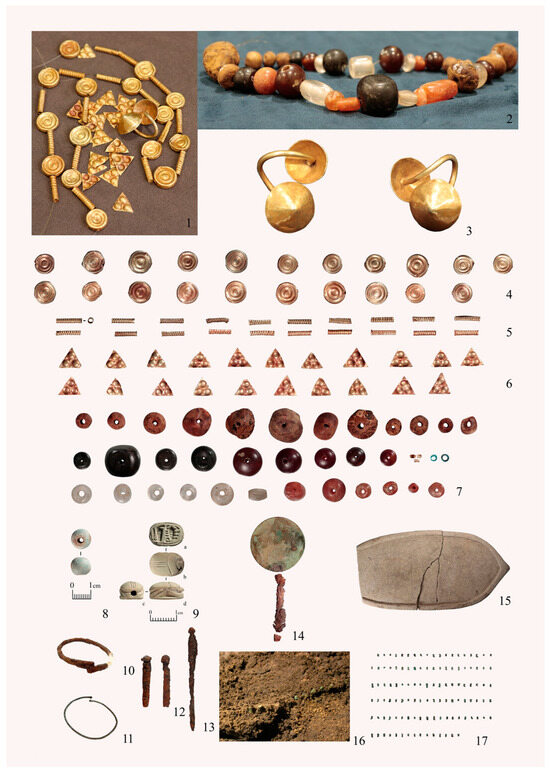

Figure 9.

Details of a funeral costume and accessories from barrow 2/2019 of the Skorobir necropolis. 1—golden forehead decoration. 2—necklace. 3—earrings. 4–5—round piercings and cylindrical piercing tubes. 6—plaques-applications. 7—beads made of amber, semi-precious stones and rock crystal. 8–9—faience beads and piercings. 10—iron bracelet. 11—bronze bracelet. 12–13—iron pins. 14—bronze mirror with an iron handle. 15—stone dish. 16—remains of a leather handbag. 17—bronze rivets from a leather handbag.

Jewelry Made of Bronze and Iron

Bracelets were found where the right and left forearms would have been. One of them, measuring 5.1 cm × 6.6 cm, is made of bronze twisted wire with conical ends and a diameter of 0.25 cm (Figure 9: 11). The woman probably wore it on her right hand. Vladimira Petrenko classified the twisted wire bracelets as type 16, noting that all documented examples date back to the 4th century BCE (Petrenko 1978, p. 56), but they obviously first appeared in the archaic period, since we found a fragment of a twisted bracelet with a conical end in the Early Scythian deposits of ash pit no. 28 of the western fortification of the Bilsk hillfort (Shramko 1995, p. 175, Figure 1: 24). Vladimira Petrenko included another fragment of a twisted bronze bracelet, found on the surface of this settlement, in the summary table (Petrenko 1978, Table 43: 16). The dating of the Western fortification limits the upper date of the possible existence of this object to the middle of the 5th century BCE.

Due to severe corrosion, the iron bracelet and nail-shaped pins did not have clear outlines. After restoration, their contours became discernible (Figure 9: 12–13). The head of one of the pins is close to hemispherical (type 13 according to Petrenko), and in the other two, the head is conical, more closely analogous to the iron pins that Vladimira Petrenko included in type 16. According to the researcher’s observation, pins with caps of such shapes appeared in the 6th century BCE and existed throughout the Scythian period (Petrenko 1978, pp. 14–15). The ends of the iron bracelet (Figure 9: 10) were riveted and overlapped with each other slightly.

An iron pin with a conical head (Figure 9: 13), lying near the occipital part of the skull (Figure 8: 5, c), could have been used to secure a leather headband or, less likely, one of fabric. The combination of nail-shaped pins and temple pendants among the grave assemblages in the burial mounds of the Middle Dnipro region led Sergei Yatsenko to reconstruct the women’s headdress as a diadem as opposed to a high hat or bashlyk (2006, pp. 53–54). Diadems are well known in elite burials of the Early Scythian period (Galanina 1997, pp. 132–36; Maslov and Petrenko 2021, p. 82). In some cases, they were not worn independently but used as an addition to a conical cap (Kisel 2003, pp. 50–52, 128).

Beads

In the chest area (Figure 8: 5, d), there was an accumulation of beads made of semi-precious stones, rock crystal, amber, white paste (Figure 8: 3), and faience (Figure 8: 5, f and Figure 9: 8–9), which were probably part of the necklace (Figure 9: 2). An unexpected find was a faience pierced bead in the shape of a scarab beetle (Figure 9: 9). Such decorations were previously unknown at inland sites in the northern Black Sea region of such an early period. The fragments of two “Eye of Horus” amulets from kurgan no. 14/1975 at the Skorobir necropolis are of a similarly early date (Shramko and Tarasenko 2022, p. 145, Figures 2 and 3). Egyptian faience amulets could have been brought to the site by nomads who had taken part in the West Asian campaigns south of the Caucasus. Even though the Greek colonies may have received other imports from Egypt (that is, the workshops of Naucratis), the scarab from barrow 2/2019 does not belong to their production (Shramko and Tarasenko 2022, p. 150).

Accessories

To the left of the decayed bones of the skeleton, level with the pelvic bones, lay a sandstone dish (Figure 8: 1 and 5, h) with a set of pottery and clay spindle whorls deposited next to it.

The sandstone dish, measuring 43 × 21.8 cm, had an oval shape; one end of the object was pointed, while the other was cut straight across, possibly broken off (Figure 9: 15). The item was discovered broken into three pieces. No traces of organic matter were observed on the surface of the dish. It is interesting that, just as in the “Repiakhuvata Mohyla” barrow (Illinska et al. 1980, pp. 40, 48, Figure 21), the dish was found in the northeastern corner of the burial. Sandstone dishes are quite common in early Scythian burials, but the specimen found in barrow no. 2/2019 belongs to a typological group that became widespread in the second and third quarters of the 6th century BCE (Makhortykh 2019, p. 356). Fragments of stone dishes were also found in the cultural deposits of the Bilsk hillfort (Shramko 1987, Figure 43: 7), and further examples were recorded in barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka and kurgan 35 near the village of Bobrytsa (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

A bronze mirror is one of the main accessories which accompany women’s burials. Mirrors found in barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka and kurgan 35 near the village of Bobrytsa belonged to different types (Kovpanenko 1981, pp. 112–14). The mirror with a central handle from Bobrytsa (Figure 3: 7) is earlier. The mirror from barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka was lost, but Yevhen Znosko-Borovsky’s description (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 140) puts it closer to the type found in barrow no. 2/2019 of the Skorobir burial ground (Figure 9: 14). The bronze disks of both mirrors had iron handles. On the Skorobir specimen, two rivets are visible, which helped attach the disk to the handle. The mirror itself was in a wooden case (Figure 8: 4), on which the imprints of a fabric lining were preserved. According to Tatyana Kuznetsova, this type of mirror could have appeared in Scythia no earlier than the second quarter of the 6th century BCE, which serves as a terminus post quem for the burial in which it was excavated (Kuznetsova 2017, pp. 103–14; 2018, p. 455).

Among the rare and even unique items that complement the female funeral costume is a leather handbag, the dark brown debris of which was recorded in the northeastern corner of the burial chamber (Figure 8: 5, i). The bag was likely closed with a flap, using a clasp similar to that found on a quiver; but for the time being, this detail of the reconstruction remains hypothetical. When the clearing took place during fieldwork, the object was preliminarily contoured on an area of 20 × 20 cm and removed in a block of soil matrix. In the restoration workshop,9 it was possible to trace the location of bronze rivets on one of the sections of the object (Figure 9: 16), which established that one side of the bag was probably about 10 cm long and that the shape of the whole item was close triangular with a rounded lower part, about 10 × 15 cm. The bag was sewn from two pieces of leather, fastened with bronze rivets which were also decorative. During clearing, 115 miniature bronze rivets were found (Figure 9: 17) composed of short, round rods 0.4 cm long and 0.2 cm in diameter. A similar bronze rivet (0.35 cm high and 0.1 cm in diameter) was found in one of the barrows of the Early Scythian period in the Peremirky tract, west of the western fortification of the Bilsk hillfort; according to the excavators, it was fastened to the bone plates of an iron knife (Kulatova and Suprunenko 2010, pp. 24–25, Figure 16: 4).

Gold Costume Elements

A distinctive feature of this burial is a set of appliqué plaques and piercings in geometric shapes as well as earrings made of a yellow metal (Figure 9: 1). These gold objects were used to decorate funeral headdresses. Some plaques and threads remained in situ, others were displaced from their original location. However, all of them were found among the frontal bones of the skull, partially displaced to the facial area (Figure 8: 2). The arrangement of gold elements (round pierced plaques and pierced tubes) clearly indicated the type of head decoration: a headband in the form of a ribbon. In some cases, it was possible to trace the location of the triangular plaques (Figure 9: 6), with their apices facing in opposite directions. Cylindrical piercings (Figure 9: 5) alternated with round “checkered” piercings (Figure 9: 4), consisting of two halves. It can be assumed that the headdress was also complemented by gold temple pendants with conical caps at the ends (Figure 9: 3), found on opposite sides of the skull. In total, during the excavation, 62 gold plaques were discovered: 21 triangular, 21 round piercings, and 20 cylindrical piercing tubes (Figure 9: 4–6). Most of them were recorded in situ.

Appearance of the Headdress

Unfortunately, the supports to which the plaques were affixed in ancient times were usually made of organic materials and are therefore hardly ever preserved in the burial mounds of the northern Black Sea region. As a result, the ceremonial female headdress of the archaic period has been reconstructed in a variety of ways in the scientific literature (Figure 2: 2–3 and Figure 3: 5–6) (Miroshina 1977, p. 85, Figure 7; p. 86, Figures 8 and 9; p. 88, Figure 11; Klochko 2012, pp. 417–26). More complex sets of plaques that combine various elements in complementary ways cannot be ruled out (Yatsenko 2006, p. 53).

Since the female burial in barrow no. 2/2019 of the Skorobir necropolis had escaped looting, we were able to record the location of the golden elements (round and cylindrical) of the piercings, in the form of two parallel rows (Figure 9: 2). Golden triangular plaques, decorated with three large and three small hemispherical convexities, were located above two rows of piercings, but they did not form a clear complete pattern; it was only possible to understand their relative position. It is very probably that the woman was wearing a leather headband, onto the base of which triangular plates were glued. Below, longitudinally, two gold threads were attached to the strap. Undoubtedly, the main additional elements of the dress were two gold earrings or temple pendants.

A 3D digital model of the possible appearance of the headdress was made, based on the study of the complete set of gold decorative elements (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

3D reconstruction of a woman’s headdress and necklace from mound 2/2019 of the Skorobir necropolis. The reconstructions differ in the length and position of the temporal rings: 1. Placement of temple rings in the temple area (fastening distance is less). 2. Placement of temple rings in the ear area (fastening distance is greater). 3. Close-up view with the placement of the temporal rings in the temple area. Digital Drawing by Valentin S. Shramko.

The lower part of the headdress was decorated with two rows of parallel elements, consisting of alternating plaques and piercings of two types: (1) round composite ones, decorated with concentric circles, 0.1 mm thick, 1.8 cm in diameter, with a hole diameter of 0.4 cm, and (2) hollow, corrugated cylindrical tube, 1.45 cm long, 0.4 cm thick, with a hole diameter of 0.3 cm (Figure 9: 4–5).

Round, two-piece piercings were made from thin gold sheets using the stamping technique. The two halves were soldered together. A hole was punched through the finished product. Cylindrical tubes were made of thin corrugated sheets, the ends of which were connected into a joint or, in most cases, overlapped one after the other.

The plaques used in alternating designs were short in length, corresponding to the distance between the temples. Consequently, the sizes of individual elements and their quantity were selected to give the overall composition of the headdress a balanced appearance. The dimensions and number of decorative elements significantly limit the size and shape of the reconstructed headdress.

The arrangement of the triangular plaques on the upper part of the headband in the form of a ribbon is determined equally by the local decorative tradition and by the dimensions of the headband and the length of the leather ribbon indicated by the surviving decorative elements. The plaques, which have a maximum size of 1.25 cm × 1.3 cm and a thickness of 0.5 mm, were made using the stamping technique and were decorated with three large hemispherical impressions and four small ones (Figure 9: 6). It is important to note that the plaques were stamped onto a thin gold sheet using two different dies to form the pattern. At the same time, the location of the hemispheres imprinted with stamps on different plaques is slightly irregular; some carelessness is noticeable in the work of the craftsperson.

The reconstruction of the headdress as a headband with decorative plaques is confirmed by the presence of two gold earrings found in the area of the skull. This type of decoration is specifically associated with this form of headdress and excludes other options. In addition, our proposed version of reconstruction is supported by the discovery of an iron nail-shaped pin near the occipital part of the skull, which was probably used to fasten the ends of the band. Such fasteners would be useless and incompatible with other types of headgear. The only alternative interpretation is a pin used to secure the hairstyle.

Of course, the main element of the funeral costume of barrow no. 2/2019 was the headband in the form of a ribbon, which indicated the status of the buried woman. However, the completeness of the costume composition was achieved through other components: a necklace made of various beads, bracelets and pins, and an amulet, which completed the ceremonial vestments and helped create a unified image of the traditional costume of elite women of the early Scythian period, buried in compliance with a specific ritual.

The closest analogies to such a set come from the costume complex we examined from barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka (Figure 2 and Figure 11). These two burials probably date back to the same time. In addition, they demonstrate a stable combination of golden elements of the headdress. Only these barrows contained pierced plaques complemented by gold earrings, triangular appliqué plaques, and skull pins. This can hardly be coincidental. The arrangement of the elements of the headdress, reliably recorded during the excavations of barrow 2/2019, allows us to quite safely assume that the headdress from barrow 100 near the village of Syniavka (Figure 2: 1a) was indeed a forehead band, as the original excavator originally claimed (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 140). The headdress from barrow 35, near the village of Bobrytsa, showed some differences in the set of decorative elements—notably, the absence of piercings and earrings (Figure 3 and Figure 11). However, in general, these cases allow us to talk about a coherent burial tradition that persisted over an extended period of time in the territory of Forest-Steppe Scythia. Its range encompassed not only the Dnipro Right Bank, where it probably had some local basis (Klochko 2008, 2012), but also the territory of the Dnipro Left Bank Forest-Steppe, where it is so far most fully represented in the materials of elite female burials of one of the necropoleis of the Bilsk hillfort.

Figure 11.

Comparative table of elements of funeral costume and accessories from barrows of Forest-Steppe Scythia. Images after Khanenko and Khanenko (1900); Bobrinskoy (1901); Kovpanenko (1981); Reeder (2001); Klochko (2012); Hribkova (2014); Klochko et al. (2021); Iryna B. Shramko, Stanislav A. Zadnikov.

5. Conclusions

For the first time since the end of the 19th century, the golden details of a female headdress of the Early Scythian period were recorded in an archaeological context in the Ukrainian Forest-Steppe. Because these materials were brought to light in an undisturbed burial, we obtained a fairly complete picture, confirming the assumptions made by a number of previous authors about the high social status and potential priestly function of women belonging to the local elite. The main features of this group of burials were the stable elements of the ceremonial (funeral) costume, which included a headdress decorated with gold appliqué plaques and piercings, supplemented in some cases with gold earrings or temple ornaments, sets of bead necklaces, pendants, metal bracelets, and nail-shaped pins. The funeral tradition involved leaving some accessories near the deceased, among which a bronze or bimetallic mirror and a stone dish should be especially highlighted. In one case, the remains of a leather handbag decorated with bronze cylindrical rivets were recorded.

In our opinion, the headdresses from kurgans 100 near the village of Syniavka, 35 near the village of Bobrytsa, and 1/2016 Skorobir could have had the appearance of conical hats; there were probably also headbands. In barrows 100 near the village of Syniavka and 2/2019 of the Skorobir necropolis, they consisted of ribbon-shaped headbands. Headscarves could have been used in all burials. Interestingly, all examples are characterized by a combination of Scythian animal-style decorative elements (appliqué plaques depicting a deer with bent legs and a mountain goat with its head turned back), the Asia Minor tradition of decorated ceremonial headdresses and headbands (golden drop-shaped pendants and rosette plaques), and the Hallstatt tradition of decorative geometric patterns (triangular appliqué plaques, triple circles). The use in the decoration of round pierced “checkers” and triangular geometric plates with hemispherical convexities in the center, along with plaques showing concentric circles in relief and other appliqué plaques of various types, may indicate that the local Forest-Steppe environment had absorbed Western traditions, ideas gleaned from the cultures of the Hallstatt circle, with which they had quite close contacts as researchers have repeatedly demonstrated (Fialko 2006, p. 61; Daragan 2010, pp. 96–106; 2011, p. 615; Shramko and Zadnikov 2021). However, since archaeological sources from the late 19th century do not provide reliable field documentation, and new excavations do not yet provide a complete picture, all proposed options for reconstructing the appearance of an archaic female headdress from these burial complexes can only be accepted as hypothetical.

Drawing on the new discoveries of 2019, we can demonstrate with a high degree of certainty that all burials contained headdresses in the form of a headband, for example, a ribbon-shaped leather headband.

A review of materials from four burial mounds of the Early Scythian period—including those from new excavations in the Dnipro Left Bank Forest-Steppe—confirms the previously stated assumption about the existence in the territory of Forest-Steppe Scythia of a group of women who occupied a special place in society, belonging to the local elite and, possibly, performing priestly functions during their lifetime. The funeral ceremony involved dressing this category of the deceased in a costume richly decorated with gold elements and a headdress complemented by a necklace made of semi-precious stones, amber, glass, and paste; Egyptian amulets; metal bracelets and pins; and gold earrings. In three out of four cases, a bronze mirror was left near the deceased; in one case, a leather handbag with bronze studs. Of course, like most female burials of the archaic period, our examples also included a stone dish, a set of molded ceramic vessels, and clay spindle whorls among the offerings. The period of such a stable funeral tradition with the noted types of funeral equipment, as well as a ceremonial funeral costume with a headdress for noblewomen, should, in our opinion, be confined to the first half of the 6th century BCE.

We can agree with Marina Daragan that such a tradition undoubtedly finds correspondences in the Hallstatt world, has Western features, and persisted for a relatively short time (Daragan 2010, p. 616; Daragan 2011, pp. 607–12, 617–8). In the northern Black Sea region, this tradition apparently took shape no earlier than the beginning of the 6th century BCE, and in the territory of Forest-Steppe Scythia, it became widespread in the first half of this century, primarily in the Middle Dnipro region, on the right and left banks of the Dnipro. Materials from new excavations indicate that representatives of the local aristocracy may have been buried in more modest burial chambers than previously thought; their burials were simple, without accompanying persons. In addition to purely female items of funeral equipment, attributes of warriors were also left in the grave, notably bridles and weapons, which could well have belonged to representatives of the aristocracy of any gender.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article: The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Not preserved. |

| 2 | Halina Kovpanenko’s monograph (1981) erroneously states that the necklace was worn around the neck (p. 13). |

| 3 | Ganna Vertienko comes to this conclusion based on a deep analysis of Iranian mythology, from which it follows that the military force (ama) was located above the horns of ungulates (or in the area above the forehead). Hence, it is important to pay special attention to the exaggerated depiction of the horns of such animals, as they may indicate the concentration of such power inherent in the military deity and warriors. Consequently, according to the researcher, products and objects with such images could endow their owners with military force or associate them with a military deity. In cases like ours, the presence of military ammunition in the burial is not accidental, and does not necessarily mean the woman’s participation in hostilities. |

| 4 | According to Yevhen Znosko-Borovsky, the fact that the main buried woman belonged to the Amazons was indicated by the presence in the grave of weapons (bows and arrows), parts of a horse bridle, the burial of a horse, and the absence of “actually male weapons”, such as a spear or sword. Based on the totality of features, the researcher dated the artifact complex to the Sarmatian period (Bobrinskoy 1901, p. 114). |

| 5 | Other researchers also paid attention to the similarities of the headdresses among the European Scythians, Asian Sakas and Persians of the Achaemenid period (Yatsenko 2006, pp. 38–39; Toleubaev 2016, p. 851). |

| 6 | According to Varvara Illinska, such plaques were a kind of emblem of the daily solar arc. In general, the set of ceremonial headdresses, in her opinion, had a magical meaning associated with the cult of the sun and its ritual symbolism (Illinska 1971, pp. 77–78). |

| 7 | Herodotus 4.108. “... The Budinoi are a very great and numerous race... in their land is built a city of wood, the name of which is Gelonos, and each side of the wall is thirty furlongs in length and lofty at the same time, all being of wood; and the houses are of wood also and the temples; ...” (Herodotus 2008). |

| 8 | Excavations of barrows in the southern part of the Skorobir necropolis have been carried out since 2013 by the Scythian expedition of the V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University (Kharkiv, Ukraine) together with the Historical and Cultural Reserve “Bilsk” (Kotelva, Ukraine). |

| 9 | The leather product was cleaned by specialist restorer Serhei Omelnik. |

References

- Akishev, Kemal A., and Alisher K. Akishev. 1980. Proiskhozhdenie i semnatika Issykskogo golovnogo ubora. In Arkheologicheskie issledovaniya drevnego i srednevekogo Kazakhstana. Edited by Kemal. A. Akishev. Alma-ata: Nauka Kazakhskoy SSR, pp. 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Alekseev, Andrey Yu. 2012. Zoloto skifskih tsarey v sobranii Ermitazha. Sankt Peterburg: Izdatelstvo Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, Petya. 2018. Fantastic Beasts of The Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach To Animal-Style Art. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2963 (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Andruh, Svetlana I., and Hennadii N. Toschev. 2022. Ranneskifskiy kompleks mogilnika Mamay-Goryi v Nizhnem Podneprove. Stratum Plus 3: 405–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bandrivsky, Mykola S. 2010. Obrazotvorchi tradytsii na zakhodiukrainskoho lisostepu u VII—Na pochatku VI st. do nar. Khr.: Vytoky i prychyny transformatsii. Arkheolohycheskyi Almanakh 21: 145–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bobrinskoy, Alexey A. 1901. Kurganyi i sluchaynyie arheologicheskie nahodki bliz mestechka Smelyi. Sankt Peterburg: Tip. Glavnogo upravleniya Udelov, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

- Boiko, Yurii M. 2017. Sotsialnyi sklad naselennia baseinu r. Vorskly za skifskoi doby. Kyiv: TsP NAN Ukrainy i UTOPiK, IKZ «Bilsk». [Google Scholar]

- Daragan, Maryna M. 2010. Pamyatniki ranneskifskogo vremeni Srednego Podneprovya i Galshtatt: Poisk hronologicheskih reperov. Revista Archeologica, cerie noua 2: 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Daragan, Maryna M. 2011. Nachalo rannego zheleznogo veka v Dneprovskoy Pravoberezhnoy Lesostepi. Kyiv: KNT. [Google Scholar]

- Fialko, Olena E. 2006. Ob odnom tipe zolotyih ukrasheniy skifskogo vremeni. Arkheolohichnyi litopys Livoberezhnoi Ukrainy 1: 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fialko, Olena E. 2023. Amazonky: Mify ta realnist. Kyiv: Instytut arkheolohii NAN Ukrainy. [Google Scholar]

- Galanina, Lyudmila K. 1977. Skifskie drevnosti Podneprovya (Ermitazhnaya kollekciya N. E. Brandenburga). In Svod arheologicheskih istochnikov. D 1–33. Moscow: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Galanina, Lyudmila K. 1997. Kelermesskie kurgany. «Carskie» pogrebeniya ranneskifskoj epohi. Moscow: Paleograf. [Google Scholar]

- Gorodtsov, Vasiliy A. 1911. Dnevnik arheologicheskih issledovaniy v Zenkovskom uezde Poltavskoy gubernii v 1906 godu. In Trudyi XIV Arheologicheskogo sezda. Moscow: Tipografiya G. Lissnera i D. Sobko, vol. III, pp. 93–161. [Google Scholar]

- Havrysh, Petro, and Valerii Kopyl. 2010. Zahadka starodavnoho Helona. Poltava: Dyvosvit. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth Kramberger, Anja. 2015. Hronologiya i rasprostranenie zolotyih nashivnyih blyashek v ranneskifskoe vremya (VIII–VII vv. do n.e.). Stratum Plus 3: 143–66. [Google Scholar]

- Herodotus. 2008. The History of Herodotus. Volume 1 (of 2). Translator: G. C. Macaulay. The Project Gutenberg EBook of The History of Herodotus, by Herodotus. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2707/2707-h/2707-h.htm#link42H_4_0001 (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Hribkova, Hanna O. 2012. Typolohiia plastyn-aplikatsii z kurhaniv dniprovskoho lisostepu z kolektsii Muzeiu istorychnykh koshtovnostei Ukrainy. Pratsi Tsentru pamiatkoznavstva 22: 136–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hribkova, Hanna O. 2014. Olen ranneskifskogo vremeni na plastinah-applikatsiyah iz skifskih kurganov Ukrainskoy lesostepi. In Muzeini chytannia. Materialy naukovoi konferentsii “Iuvelirne mystetstvo—pohliad kriz viky”. Edited by Liudmyla V. Strokova. Kyiv: TOV “Feniks”, pp. 101–8. [Google Scholar]

- Illinska, Varvara A. 1968. Skifyi dneprovskogo lesostepnogo Levoberezhya: Kurganyi Posulya. Kyiv: Naukova dumka. [Google Scholar]

- Illinska, Varvara A. 1971. Zoloti prykrasy skifskoho arkhaichnoho uboru. Arkheolohiia 4: 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Illinska, Varvara A., and Oleksii I. Terenozhkin. 1971. Skifskyi period. In Arkheolohiia URSR. II. Kyiv: Naukova dumka, pp. 8–184. [Google Scholar]

- Illinska, Varvara A., Borys M. Mozolevskyi, and Oleksii I. Terenozhkin. 1980. Kurgany VI v. do n.e. u s. Matusov. In Skifiya i Kavkaz. Edited by Oleksii I. Terenozhkin. Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, pp. 31–63. [Google Scholar]

- Khanenko, Bohdan I., and Varvara M. Khanenko. 1900. Drevnosti Pridneprovya. Kyiv: Typohrafyia i fotohraviura S. V. Kulzhenko, Issue 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kisel, Vladimir A. 2003. Shedevryi yuvelirov Drevnego Vostoka iz skifskih kurganov. Sankt-Peterburg: Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie. [Google Scholar]

- Klochko, Liubov S. 1986. Rekonstruktsiia konusopodibnykh holovnykh uboriv skifianok. Arkheolohiia 56: 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Klochko, Liubov S. 2007. Shpylky u vbranni naselennia Skifii. In Muzeini chytannia. Materialy naukovoi konferentsii “Iuvelirne mystetstvo—Pohliad kriz viky”. 11 – 12 hrudnia 2006. Edited by Liudmyla V. Strokova, Liubov S. Klochko, Svitlana A. Berezova and Yurii O. Bilan. Kyiv: TOV “KHIK”, pp. 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Klochko, Liubov S. 2008. Zhinochi holovni ubory plemen Skifii za chasiv arkhaiky. In Muzeini chytannia. Materialy naukovoi konferentsii “Iuvelirne mystetstvo—Pohliad kriz viky”. 12–14 lystopada 2007. Edited by Liudmyla V. Strokova, Liubov S. Klochko, Svitlana A. Berezova and Yurii O. Bilan. Kyiv: TOV “Feniks”, pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Klochko, Liubov S. 2012. Uboryi skifskih zhrits (pamyatniki perioda arhaiki iz Dneprovskogo lesostepnogo Pravoberezhya). In Peregrinationes Archaeologicae in Asia et Europa Joanni Chochorowski Dedicatae. Edited by Wojciech Blajer. Kraków: Archeobooks, pp. 417–26. [Google Scholar]

- Klochko, Liubov S., Yurii O. Bilan, Svitlana A. Berezova, and Yevheniia O. Velychko. 2021. Serezhky u vbranni naselennia Skifii (z kolektsii Muzeiu istorychnykh koshtovnostei Ukrainy). Kyiv: TOV Feniks. [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnychenko, Anzhelika M., Oleh Yatsuk, Mafalda Costa, José Mirão, and Pedro Barrulas. 2019. Vid chornoho moria do Karpat: Problema vyrobnytstva ta rozpovsiudzhennia sklianoi produktsii Yahorlytskoi maisterni. In Pontica et Caucasica II. Interdisciplinary research on the antiquity of the Black Sea. Abstracts of the conference. Warszawa: University of Warsaw, pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]