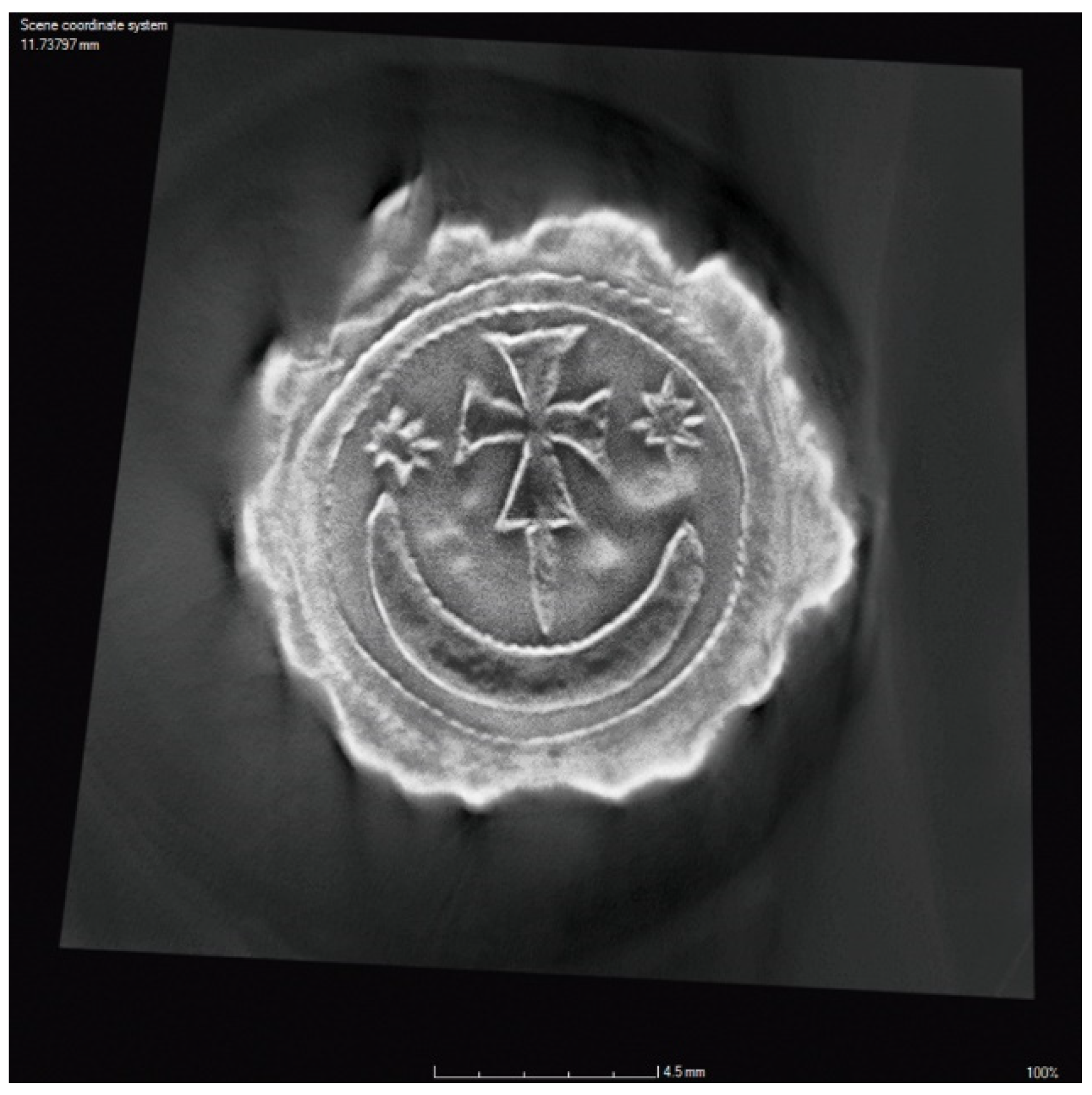

Rings with Heraldic Motives from the Wiener Neustadt Treasure: Imitations of Medieval Signet Rings?

Abstract

:1. General Characterisation of the Wiener Neustadt Treasure

2. The Rings with Heraldic Motifs

3. Signet Rings or “Just” Prestige Objects?

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The treasure was discovered during the digging of a biotope on private property but was not recognised as such at first and it was stored in the cellar for years. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | For the content of the treasure and the results of the interdisciplinary examination, see Kühtreiber et al. (2014). |

| 4 | The treasure from Fuchsenhof (Upper Austria), for example, shows a similarly high number of rings: Krabath (2004, p. 233). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | See Singer (2014a, pp. 134–37) for the details. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Singer (2014a, pp. 147–48) (with further literature). |

| 9 | Singer (2014a, pp. 146–47) (with further literature). |

| 10 | Singer (2014a, p. 149) (with further literature). |

| 11 | Singer (2014a, pp. 149–50) (with further literature). |

| 12 | For examples of similar motives see Singer (2014a, p. 148). |

| 13 | Singer (2014a, pp. 150–51) (with further literature). |

| 14 | Singer (2014a, pp. 155–56) (with further literature). |

| 15 | Zajic (2014a, pp. 250–51) (with further literature). |

| 16 | Singer (2014a, pp. 151–52) (with further literature). |

| 17 | Singer (2014a, p. 152) (with further literature). |

| 18 | For late roman examples cf. (von Bassermann-Jordan 1909, p. 37, Abb. 43; Johns 1996, p. 63, Figure 3.24, 3.25); and for medieval rings with this motif, for instance, Stefan Krabath (2004, pp. 276–78, 562–64, 588–89, no. 249–62, 272). |

| 19 | Zajic (2014a, p. 244) (with further literature). |

| 20 | For more details concerning the Vierdung family see Zajic (2014b, pp. 265–69). |

| 21 | See Zajic (2014a, p. 247) with further discussion. |

| 22 | For instance the inscription on the ring Figure 15: “WOLMICHEINRASGI”. See Zajic (2014a, p. 248, fig 265). |

| 23 | “Meaningless” inscriptions can be found on nine rings of the hoard: Zajic (2014a, p. 238). |

| 24 | For examples of real signet rings see, e.g., Chadour and Joppien (1985, pp. 138–43, no. 213–22) (especially no. 222 with pseudo-inscription!) and Hindman (2015, pp. 180, 144, 212–13, 215, 218, no. 37, 38, 39, 43, 49). |

| 25 | Heraldic motifs were very popular in the Gothic period and can also be found on other jewellery or costume items: Stürzebecher (2015, pp. 66–67). |

| 26 | Zajic (2014a, p. 247) (with further literature). |

| 27 | Maria Stürzebecher argues in the same vein regarding a ring from the treasure of Erfurt (Germany), which picks up a motif known from seals but it was certainly not used as a typar: Stürzebecher (2010, pp. 90–94). |

| 28 | In the treasure from Fuchsenhof, too, only one (visually very similar) ring is explicitly addressed as a signet ring: Krabath (2004, p. 278; 625/Catnr. 317–18). A possible indication of the actual use of this object as a signet ring is the fact that the ring was deliberately broken in the middle (i.e., rendered useless or thus ‘devalued’ in the future). This is not the case with any of the finger rings from the Wiener Neustadt hoard. |

References

- Chadour, Anna Beatriz, and Rüdiger Joppien. 1985. Anna Beatriz Chadour and Rüdiger Joppien, Kunstgewerbemuseum der Stadt Köln-Schmuck II. Köln: Fingerringe. [Google Scholar]

- Hindman, Sandra. 2015. Take This Ring. Medieval and Renaissance Rings from the Griffin Collection. Turnhout: Les Enluminures. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, Nikolaus, ed. 2014. Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt. Horn: Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges. mb H. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, Nikolaus. 2015. Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt: Überlegungen zur Deutung eines außergewöhnlichen Fundkomplexes. In Wert(e)wandel. Objekt und kulturelle Praxis in Mittelalter und Neuzeit. Edited by Claudia Theune and Stefan Eichert. Beiträge zur Mittelalterarchäologie in Österreich. Wien: Österreichische Gesellschaft für Mittelalterarchäologie, vol. 31, pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, Catherine. 1996. The Jewellery of Roman Britain: Celtic and Classical Traditions. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Krabath, Stefan. 2004. Die metallenen Trachtbestandteile und Rohmaterialien aus dem Schatzfund von Fuchsenhof. In Der Schatzfund von Fuchsenhof. Edited by Bernhard Prokisch and Thomas Kühtreiber. Studien zur Kulturgeschichte von Oberösterreich. Linz: Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum, vol. 15, pp. 231–305. [Google Scholar]

- Kühtreiber, Thomas, Marianne Singer, and Nikolaus Hofer. 2014. Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt. Synthese der Forschungsergebnisse. In Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt. Edited by Nikolaus Hofer. Horn: Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges. mb H., pp. 298–321. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Marianne. 2014a. Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt. Eine kulturhistorische Analyse. In Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt. Edited by Nikolaus Hofer. Horn: Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges. mb H., pp. 130–237. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Marianne. 2014b. Objektkatalog des Wiener Neustädter Schatzfundes. In Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt. Edited by Nikolaus Hofer. Horn: Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges. mb H., pp. 340–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stürzebecher, Maria. 2010. Der Schatzfund aus der Michaelisstraße in Erfurt. In Der Schatzfund. Archäologie. Kunstgeschichte. Siedlungsgeschichte. Edited by Sven Ostritz. Die mittelalterliche jüdische Kultur in Erfurt. Weimar: Thüringisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie, vol. 1, pp. 60–212. [Google Scholar]

- Stürzebecher, Maria. 2015. Imitation und Nachahmung. Phänomene gotischer Goldschmiedekunst. In Wert(e)wandel. Objekt und kulturelle Praxis in Mittelalter und Neuzeit. Edited by Claudia Theune and Stefan Eichert. Beiträge zur Mittelalterarchäologie in Österreich. Wien: Österreichische Gesellschaft für Mittelalterarchäologie, vol. 31, pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- von Bassermann-Jordan, Ernst. 1909. Der Schmuck. Leipzig: Klinkhardt & Biermann. [Google Scholar]

- Zajic, Andreas. 2014a. Epigrafische und heraldisch-sphragistische Bemerkungen zum Wiener Neustädter Schatzfund. In Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt. Edited by Nikolaus Hofer. Horn: Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges. mb H., pp. 238–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zajic, Andreas. 2014b. Das historische Umfeld des Wiener Neustädter Schatzfundes. In Der Schatzfund von Wiener Neustadt. Edited by Nikolaus Hofer. Horn: Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges. mb H., pp. 264–73. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hofer, N. Rings with Heraldic Motives from the Wiener Neustadt Treasure: Imitations of Medieval Signet Rings? Arts 2022, 11, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060117

Hofer N. Rings with Heraldic Motives from the Wiener Neustadt Treasure: Imitations of Medieval Signet Rings? Arts. 2022; 11(6):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060117

Chicago/Turabian StyleHofer, Nikolaus. 2022. "Rings with Heraldic Motives from the Wiener Neustadt Treasure: Imitations of Medieval Signet Rings?" Arts 11, no. 6: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060117

APA StyleHofer, N. (2022). Rings with Heraldic Motives from the Wiener Neustadt Treasure: Imitations of Medieval Signet Rings? Arts, 11(6), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060117