Abstract

The article examines the correlation between the stylistic iconography of traditional Ukrainian embroideries and the experiments in modernist painting that led to the emergence of abstraction, Suprematism in particular. The focus is made on the artistic output of the embroidery workshops in the villages of Verbivka and Skoptsi, both located on the territory of present-day Ukraine, in the early 1910s. These studios, led by Natalia Davydova and Alexandra Exter, and Yevheniia Prybylska, respectively, engaged ‘leftist’ artists and local artisans to produce a new type of embroidery, relinquishing the mere stylization characteristic of other kustar studios in the Russian Empire. While scholars in Ukraine have undertaken extensive research to highlight the centrality of the Ukrainian context in progressive artists’ engagement with folk embroidery on the territory of the Russian Empire, internationally this phenomenon is still largely viewed under the generalized imperialist term of the ‘Russian avant-garde’. Using existing scholarship as the foundation, the present article seeks to redress this misconception. It also recognizes the long overdue need to situate the handicrafts revival movement in Ukraine within the broader framework of the engagement with vernacular culture by the nationally minded intelligentsia in East-Central Europe, while contrasting it with similar undertakings in Russia proper.

Keywords:

Ukrainian embroidery; abstraction; Suprematism; Verbivka; Skoptsi; Alexandra Exter; Kazimir Malevich Before any significant displays of modern art took place in Kyiv, one of the cultural events with a lasting impact was The South-Russian Exhibition of Applied Arts and Handicrafts, staged by the city’s Museum of Industrial Arts and Science.1 The show, which was masterminded by the archaeologist and Museum’s director Mykola Biliashivskyi, opened in February 1906 after almost a year of research and preparation.2 This was the first exhibition of this kind to be presented in the Ukrainian lands of the Russian Empire, containing examples of handicraft production gathered from all Ukrainian regions, including Halychyna (Galicia), which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. The regional diversity equalled the diversity of showcased material—pottery, embroidery, peasant drawings, wood and stone carving, weaving, Easter eggs, and other local crafts. While many of the items were collected specifically for the exhibition, the show also contained objects from the Museum’s holdings as well as loans from numerous collections of private individuals.3 Among the organizers and lenders was the young artist Alexandra Grigorovich, soon to be known under her married name as Alexandra Exter.4

The South-Russian Exhibition of Applied Arts and Handicrafts marked the beginning of Exter’s in-depth engagement with Ukrainian folk art, embroidery in particular, which she continued to promote for the rest of her life. Exter’s commitment to Ukrainian folk traditions went hand in hand with her espousal of some of the twentieth century’s most radical art experimentations, from Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism. Concurrently with exhibiting her progressive artworks in Europe and the Russian Empire, Exter also oversaw the artistic direction of the embroidery workshop in the village of Verbivka, in today’s Ukraine. While promoting the modernization of the centuries-long practice, Exter was also keen to employ the compositional and chromatic principles of traditional Ukrainian embroidery to expand the visual language of modern art. Through the work of Exter and a close circle of her associates, this article considers the unexpected creative link between the traditional and the innovative, with the ensuing contribution of the Ukrainian vernacular culture to the development of abstract art.

Alexandra Exter’s interest in Ukrainian folk art was sparked through her friendship with Natalia Davydova, a Ukrainian noblewoman, artist, collector, and patron of the arts, peasant handicrafts in particular. Born Hudym-Levkovych, Davydova came from a family of ennobled Cossacks. Her mother, Yuliia Hudym-Levkovych, was one of the early promoters and supporters of Ukrainian handicrafts, having set up an embroidery workshop in her village of Zoziv in 1906.5 Davydova, therefore, became acquainted with the embroidery technique in her youth and practiced it herself. Following in her mother’s footsteps, in 1912 she organized a studio dedicated to the collection and recreation of traditional models of Ukrainian embroidery in her own country estate of Verbivka.6 Exter became actively involved with the workshop, undertaking research trips to find original examples for artisans to copy and eventually supplying her own designs for craftsmen to create new embroidery while respecting the medium’s traditions (Kovalenko 2010, vol. 1, p. 25).

At first glance, such promotion of local folk art by the upper classes in Ukraine appears in line with the broader handicrafts revival undertakings within the Russian Empire and across Europe, as inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement in England.7 In Russia, like elsewhere, this sought to soften the threat of modern life to the traditional ‘rural’ way of living by creating local employment for the peasantry and lessening the lure of factory jobs in urban centres. The proponents of the movement also strove to preserve examples of traditional peasant production that were increasingly replaced by factory-manufactured items. In her important study of the kustar revival in late imperial Russia, Wendy Salmond contrasts Polish and Irish, ‘for whom the renaissance of handicrafts was directly associated with the struggle for political autonomy and home rule’, with Russians, who, she argues, used the revival of peasant crafts as a tool to promote harmony in the multinational empire (Salmond 1996, p. 5). The aspirations of the Russian elite, however, should not be conflated with those of other nationalities within the realm of Moscow. While Salmond acknowledges that the Russian Empire consisted of ‘disparate and discontented nationalities’, little differentiation is made in her study between the socio-political aspirations of various workshops that existed on its territory (Salmond 1996, p. 5). As such, she describes the workshops in Ukraine, including Davydova’s Verbivka and her mother’s Zoziv, as similar to those in Russia without attending to their different political and cultural agendas.8 Such an approach is symptomatic of a broader issue—international scholarship’s historical lack of desire to recognize the Russian Empire, and its subsequent iteration as the Soviet Union, as a colonizer. This has precluded a more nuanced reading of the art production on the terrains of these empires, which is also underlined by the routine application of the all-embracing term ‘Russian avant-garde’ to denote the modernist art of these multinational empires.9 By highlighting the specificity of the Ukrainian context, the present study contributes to the on-going efforts to challenge the existing Russo-centric interpretations of art history in the post-Soviet region. Several recent publications on the kustar revival in late imperial Russia have provided a more accurate analysis. Alla Myzelev, for example, indicates that the Ukrainian intelligentsia was reluctant to receive funding from such governmental bodies as the Main Department of Land Management and Agriculture (abbreviated in Russian as GUZiZ), founded in 1905, since ‘reviving peasant handicrafts under the auspices of G.U.Z.I.Z. (sic) was directly equivalent to trading Ukrainian culture and heritage for Russian’ (Myzelev 2007, p. 193). Similarly, in her study of women collectors of handicrafts across the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century, Hanna Chuchvaha emphasizes that those coming from Ukraine worked within ‘the rich cultural context of Ukrainian national revival and the growth of a national consciousness’ (Chuchvaha 2020, p. 59).

Back in 1906, the use of ‘South-Russian’ in the title of the Kyiv exhibition was not coincidental. In the imperial context, Ukrainian lands under the rule of the Russian Empire were officially referred to as the ‘South-Russian provinces’ or ‘South-Western krai [region]’. Unofficially, however, Russian cultural colonialism was propagated by the moniker Malorossia or Little Russia, which was applied to Ukraine. Originally a geographical term denoting the distance from Constantinople to the historical Rus lands, which today constitute the territory of Ukraine and Belarus, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was increasingly used to indicate the subservience of the Ukrainian language and culture to the ‘greater’ Russian ones. As the historian Serhii Plokhy outlines, this led to the emergence of the so-called ‘Little Russianism’—‘a tradition of treating Ukraine as “Lesser Russia” and the Ukrainians as part of a larger Russian nation’ (Plokhy 2016, p. 119). Such a degrading appellation, which Russians continue to use today for Ukraine and Ukrainians, played an important role in Russia’s attempts to strip Ukraine of its national identity.

In light of the aforementioned arguments, it might be more fitting to view the engagement of the nationally conscious Ukrainian nobility and intelligentsia with the local vernacular culture as corresponding to the revival movements in the Austro-Hungarian, rather than Russian, Empire. In his review of the use of peasant design in Austria-Hungary, David Crowley outlines how ‘other’, non-titular nations of the Dual Monarchy reconfigured their approach to the peasantry in an attempt to challenge and undermine the existing imperial structures (Crowley 1995, pp. 5–6). Similarly, pursuing a patriotic agenda of their own, while the use of the Ukrainian language was forbidden by the Ems Ukaz, the pro-Ukrainian landowning elite was eager to use folk art to formulate and reassert the distinctiveness of Ukrainian culture within the imperial context.10 Olha Kosach published one of the earliest studies on the subject in 1876—Ukrainskiy narodnyi ornament. Vyshivka, tkani, pisanki [Ukrainian Folk Ornament: Embroideries, Textiles, Easter Eggs].11 The book summarized Kosach’s inspection of the folklore culture in the Volhynia region of Western Ukraine in an attempt to determine to what extent Ukrainian ornamentation was original as opposed to being borrowed from other nations. She concluded that the studied examples of Ukrainian ornaments did not display fragmentation of themes and inconsistency of combinations, thus attesting to their ingenuity (Kosach 2018, p. 41, re-printed edition). Kosach also argued for the unity of ornamentation found in Volhynia, a region that was considered Polonized in the public opinion within the Russian Empire, and the ‘Southern Russian provinces’, stating that her collected materials served as evidence of ‘purely Ukrainian traits in the creations of the Volhynia population’ (Kosach 2018, p. 25).12

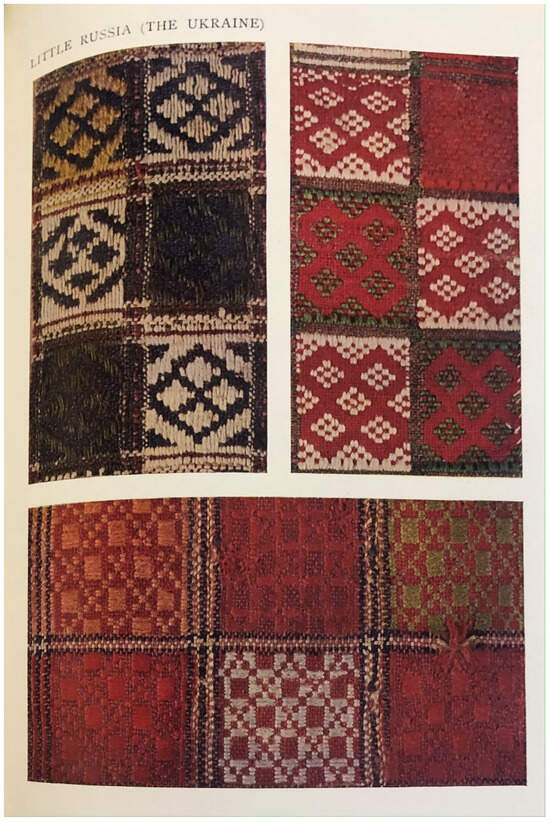

In the book’s section on embroidery, Kosach compared Ukrainian ornaments with those of other Slavic cultures, Russians and Yugoslavs in particular. She contended that there were two main differences between the Russian and Ukrainian examples. In terms of pattern, Ukrainians used more geometrized ornaments that were derived from floral motifs with limited incorporation of realistic elements. Kosach observed that while the Ukrainian style developed themes of pure ornamentation and simplified forms, the Russian took on a pictorial character and was marked by the abundance of figurative images, such as birds, people, horses, lions, dragons, and griffins (Kosach 2018, pp. 109–10). When it came to colour, Russian embroidery tended to be monochromatic, with the sole use of red, whereas Ukrainians deployed a broader plethora of hues (Kosach 2018, pp. 109–10, 120). Examples of Ukrainian embroideries with geometrized motifs and contrasting colours, as described by Kosach, made their way into the collection of the Kyiv Museum of Industrial Arts and Science. In 1912, Charles Homes edited a Special Issue ‘Peasant Art in Russia’ as part of his Arts and Crafts London magazine The Studio (Biliashivskyi 1912). The issue contained a separate section dedicated to the handicrafts of Little Russia (The Ukraine), featuring photos of items from the Kyiv Museum. Those showcasing the hand-woven materials used for Ukrainian skirts (Figure 1) can serve to illustrate Kosach’s arguments.

Figure 1.

‘Hand-woven Material Used for Skirts’, plates no. 370–372, ‘The Peasant Art of Little Russia (The Ukraine)’, in The Studio, 1912. The British Library.

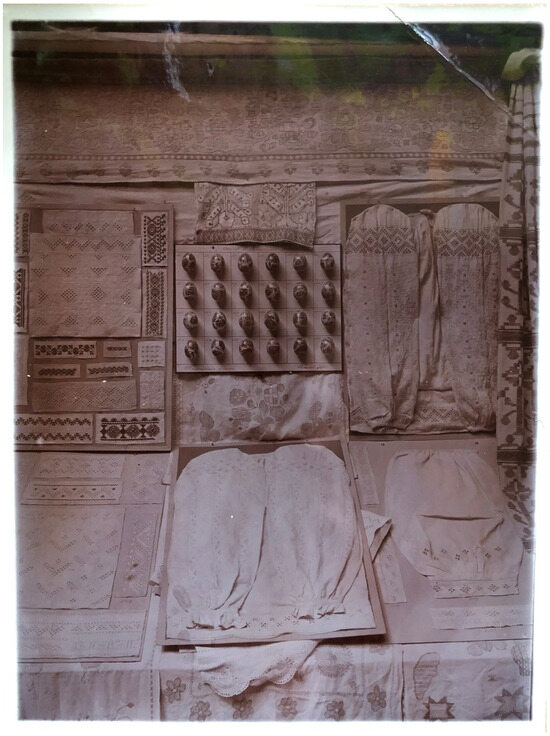

Many members of Ukrainian intelligentsia and landowning nobility, including Olha Kosach, participated in staging the 1906 exhibition at the Kyiv Museum of Industrial Arts and Science that showcased the wealth and breadth of folk art produced in Ukrainian lands. Alexandra Exter was brought in by Natalia Davydova to assist with the selection of embroidery and pottery.13 In addition to her work on the selection committees, Exter also organized and paid for one of the rooms within the exhibition, which recreated an interior of a wealthy eighteenth-century Ukrainian or, as it was called at the time, ‘Little Russian’ house. The room, constructed based on Exter’s drawings, contained traditional ceramics and textiles, as well as Cossack weaponry, and it can be partially seen in the middle of one of the few surviving photos from the exhibition (Figure 2). Exter also devised the display for carpets and embroideries. In his extensive monograph on the artist, Georgiy Kovalenko describes this presentation in the following way:

Carpets were hung on the walls, touching the ceiling and each other. They were all of different lengths, and their lower limits formed an angular, stepwise line. Along it, rows of Easter eggs formed a sort of frieze. Embroideries were displayed beneath this frieze. The great majority of them were embroidery on shirts, and shirts were not shown in their entirety, they were folded so that only the embroidered zones were shown.(Kovalenko 2010, vol. 1, p. 29)

Figure 2.

Installation Shot, The South-Russian Exhibition of Applied Arts and Handicrafts, 1906, photo credit I. Knypovych. Archive of The National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art, Kyiv.

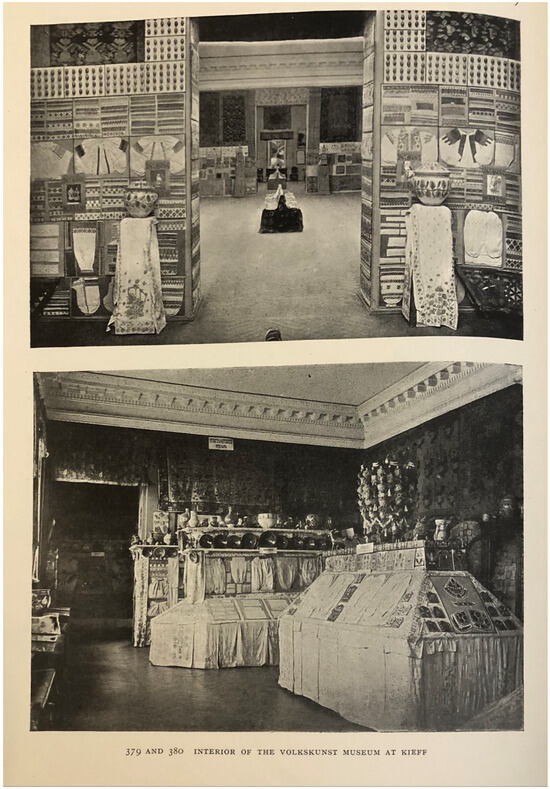

While no photographs from the exhibition exactly matching this depiction have been found in the archives, some of the available images do fit the above report. The presentation of folk art from the Podilia region in central Ukraine (Figure 3) combines some of the outlined elements—walls covered with carpets, friezes with Easter eggs, an asymmetrical and somewhat overlapping array of embroidered shirts and rushnyky (hand towels). A very similar set-up can also be seen in a photograph from the aforementioned issue of The Studio, featuring the interior of the ‘volkskunst museum at Kieff’ (Figure 4, top), which aligns with the fact that many of the exhibits from the 1906 show were transferred to the ethnographic collection of the Museum.14 Both the re-constructed Ukrainian interior and the overall display created an immersive experience, a total artwork in a sense, which can be viewed as a precursor to Exter’s explorations in theatre design in the late 1910s and early 1920s.15

Figure 3.

Installation Shot, The South-Russian Exhibition of Applied Arts and Handicrafts, 1906, photo credit I. Knypovych. Archive of The National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art, Kyiv.

Figure 4.

Interior of the ‘Volkskunst Museum at Kieff’, plates no. 379–380, ‘The Peasant Art of Little Russia (The Ukraine)’, in The Studio, 1912. The British Library.

The year 1906 turned out to be an important one for Exter’s artistic development also in another respect—she visited Europe, including Paris, for the first time.16 While this trip introduced her to some of the newest trends in art, it is important to remember that, by then, she was already intimately acquainted with Ukrainian folk traditions. In 1907, Exter settled in Paris more permanently, enrolling to take classes in both Académie Julian and Académie de la Grande Chaumière. She soon discovered the art of Henri Matisse and other Fauvists, with their colouristic freedom and abundance. One might reasonably speculate that Exter was drawn to their paintings because they reaffirmed her own chromatic preferences acquired through exposure to Ukrainian folk art. However, it was not only the colours of peasant handicrafts that inspired Exter, she was also keen to adopt their compositional elements. The art critic Yakov Tugendkhold, in his 1922 monograph on the artist, observed that Exter’s paintings were always conceived as ‘densely filled, evenly saturated with forms carpets’ (Tugendkhold 1922, p. 12). Decades later, this astute remark prompted Georgiy Kovalenko to research and highlight the inspiration that Exter sought in Ukrainian decorative traditions.

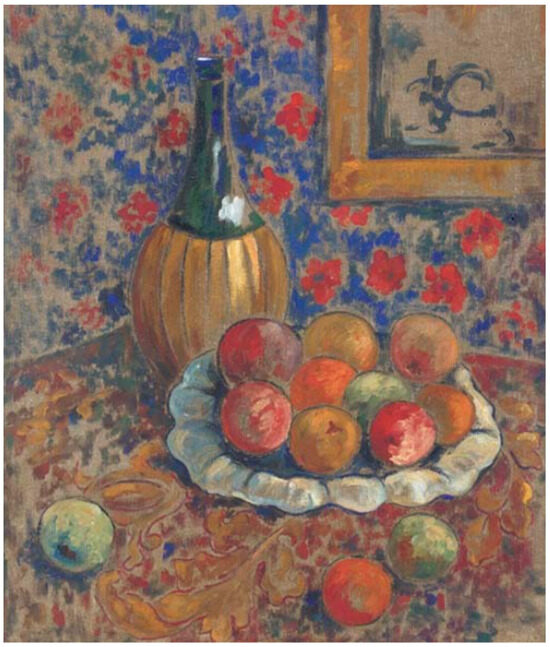

When analysing Exter’s works from her early period, Kovalenko asserts that her backgrounds tend to be Matisse-like while she models her objects after Cézanne (Kovalenko 2010, vol. 1, pp. 65–67). Whilst agreeing in principle with such an analysis, it could also be suggested that Exter’s treatment of the background was in line with the decorative traditions of Ukrainian folk art. The artist herself attested to this by stipulating that ‘[an] essential characteristic of this kind of art [drawings for fabrics, carpets, embroideries] is the flat treatment of forms in ornaments, be they floral, animal, or architectural’ and that a decorative composition is characterized by its subservience to rhythm, which is simpler and more symmetrical than that of a painterly composition (Exter 1918, p. 18). Some of these principles can be detected in Still Life with Carafe and Fruit (ca. 1907) (Figure 5). A bottle and a dish full of fruit are placed on a table covered with intensely ornamented cloth that is set against a brightly coloured wallpaper of floral motifs. The overall chromatic scheme is somewhat faded, but it conveys an inherent compositional rhythm through the use of contrasting colours—the orange-red flowers of the wallpaper set against the deep green of the glass bottle and the patches of the same colour on the tablecloth; the golden-yellow of the picture frame on the wall, the bottle holder and the leafy motifs of the tablecloth as contrasting the cobalt blue background of the wallpaper and smears of the same colour used on the glass of the bottle and the tablecloth. Although Exter uses different floral motifs for the wallpaper and the tablecloth, the fabric nonetheless appears to pass from the surface of the table to the wall and onto the framed painting hanging on it. The use of white for the fruit dish in the middle of the table anchors the composition and gives its stability. A compelling case can, therefore, be made that Exter’s initial inspiration was drawn from the Ukrainian decorative designs, before being re-confirmed and developed into an artistic system through her exposure to art practices in the West, first Fauvism and later Cubism.

Figure 5.

Alexandra Exter, Still Life with Carafe and Fruit, ca. 1907, oil on canvas, 54 × 45.7 cm. Private collection.

In the 1910s, Exter continued to split her time between the West and the East, regularly returning to her native Kyiv. She reached a new level of engagement with Ukrainian folk art in 1914, when Davydova invited her to take over as the artistic director of the Verbivka embroidery studio. Exter and Davydova wanted to move away from pure imitation and preservation of existing forms to allow for the emergence of a new type of embroidery. Their ambition was to abandon the established practice of creating designs that replicated old embroideries, characterized by the chromatic dullness that they acquired with time. Instead, Exter wanted to explore the brightness and dynamism of peasant drawings, embroideries and Easter eggs, while retaining certain simplified compositional elements of folk art. Due to her in-depth research in the field, she recognized that such an approach was aligned with original principles that dictated the choice of colour, line and composition in traditional handicrafts (Exter 1918, p. 18). Exter and Davydova also encouraged the introduction of peasant artisans to the creative process, acknowledging their potential as individual artists and not mere craftsmen. Practically, the pursuit of modernization was achieved through the incorporation of embroidery into contemporary design and fashion—belts, scarfs, theatre purses, and gowns. Conceptually, the realm of traditional embroidery was expanded by inviting ‘leftist’ artists to capture their artistic explorations in sketches for embroidery, which were transferred to needlework charts and sewn by peasant women working in the studio.

Such a quest to modernize embroidery in Ukraine was not only limited to Verbivka. In 1910, another noblewoman Anastasiia Semyhradova opened a higher primary school with a dedicated embroidery workshop in her estate of Skoptsi.17 She invited the artist Yevheniia Prybylska, a friend of Exter’s whose work she promoted, to oversee the workshop’s artistic direction. Born in Rybinsk in today’s Yaroslavl region of Russia, Prybylska studied at the Kyiv Art School. After graduating in 1907, she spent countless hours at the Kyiv Museum of Industrial Arts and Science, where she studied and copied examples of Ukrainian folk art from its vast collection (Prybylska 2014, p. 104).18 Semyhradova’s original intention was for the Skoptsi studio to re-create the antique ornaments based on drawings made in local churches and museums to be used mainly for utilitarian purposes, such as for shirts and towels. Prybylska, however, gradually started to introduce the production of decorative embroidered items, including cushions and textiles for furniture. Similarly to Exter and Davydova, Prybylska not only created designs that peasant artisans re-produced in embroidery, but she also taught craftsmen the core artistic principles, thus encouraging their development as artists in their own right.

A shift occurred in Prybylska’s artistic practice in 1914 that had a direct implication on the embroidery produced at Skoptsi. That year, the decorative items from the workshop were exhibited at Salon d’Automne in Paris as part of the Russian folk art section organized by Tugendkhold. Prybylska went to Paris to oversee the installation and was exposed to the examples of French decorative art exhibited at the Salon. She was particularly drawn to the textile designs of Raoul Dufy, who was at the time studying old French prints with their large primitive flowers. Prybylska became inspired by Dufy’s innovative explorations in colour and ornamentation, in which he sought heightened expressionism and decorativeness of forms, as well as pure colours. Unsurprisingly, Dufy was fascinated with drawings by Ukrainian peasants that Prybylska showed him and encouraged her to continue collecting this ‘fresh material’, as he called them (Prybylska 2014, p. 106). Upon her return from France, Prybylska decided to relinquish designs that replicated old embroideries with their subdued palette. As Exter pointed out, henceforth Prybylska’s work adhered to the roots and laws that dictated chromatic and compositional choices in traditional folk art (Exter 1918, p. 18). Since very few of her original works or photos of them have survived, it is difficult to analyse the specifics of this change within Prybylska’s practice. A fragment of a decorative panel designed by the artist and dated between 1913 and 1915 (Figure 6) is likely to represent a moment of transition—the colours become brighter and bolder and, while rendering a rather traditional floral arrangement, Prybylska uses a symmetrical structure and geometrized elements to create a more dynamic composition.

Figure 6.

Yevheniia Prybylska, Fragment of a Decorative Panel, 1913–1915, embroidery on silk. The National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art, Kyiv.

Such an engagement of modernist artists with folk traditions in Ukraine developed concurrently with the emergence of Neo-Primitivism in Russia proper. However, there was a conceptual difference in the use of folk art by Russian artists and those working in Ukraine. For the likes of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, as Wendy Salmond outlines, ‘[…] it was the contemporary artist’s task to emulate only the essence of its [peasant art’s] primitive spirit, not its pedestrian forms. Nor was it his or her task to fight against the decline of folk art by actively intervening in its protection’ (Salmond 2002–2003, p. 12). Such ‘emulation of the essence’ pursued a twofold agenda. On the one hand, the incorporation of the elements of ‘low’, peasant culture served as the necessary épatage to shock the bourgeoisie. On the other, the use of local folklore provided means to differentiate Russian artists from their Western counterparts, it was their version of the ‘exotic other’ that they did not have to import from the decadent West. Such strategies appear to be alien to Davydova, Exter and Prybylska in their work with peasant artisans in Verbivka and Skoptsi. Their approach was less calculated since they maintained that examples of traditional techniques should be collected, studied and reinvigorated through new forms, as opposed to simply inspiring the avant-garde.

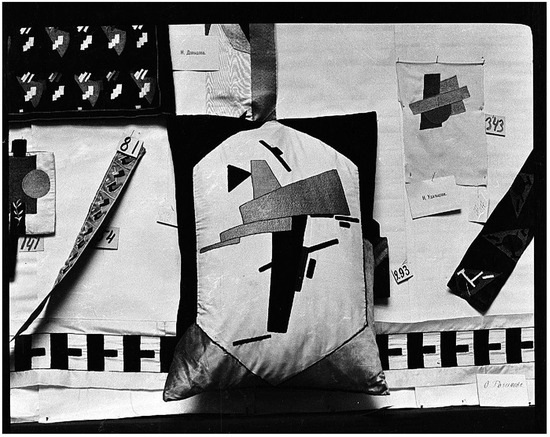

A turning point for the development of both the Verbivka and Skoptsi studios was the exhibition Contemporary Decorative Art. Embroideries and Carpets Based on Artists’ Sketches that opened at the Lemercié Gallery in Moscow in November 1915. Verbivka was represented by embroideries executed by peasant women from the workshop based on designs by Exter, Davydova and Prybylska as well as a cohort of ‘leftist’ artists soon to be associated with Suprematism, including Kazymyr Malevych himself as well as Ksenia Boguslavskaya, Nina Henke, Vera Popova, and Ivan Puni (Pougnay). The workshop also showcased three embroideries based on sketches by a peasant artisan Yevmen Pshechenko, alongside thirty-three sketches drawn by him, which was the first time that a local craftsman was shown as an artist in his own right at a major ‘leftist’ exhibition. At the same time, Skoptsi displayed carpets and textile designs based on sketches by Prybylska from 1910 and 1913, as well as her post-Paris work of 1914–1915 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Yevheniia Prybylska, Installation Shot of the Exhibition Contemporary Decorative Art. Embroideries and Carpets Based on Artists’ Sketches, 1915. Archive of The National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art, Kyiv.

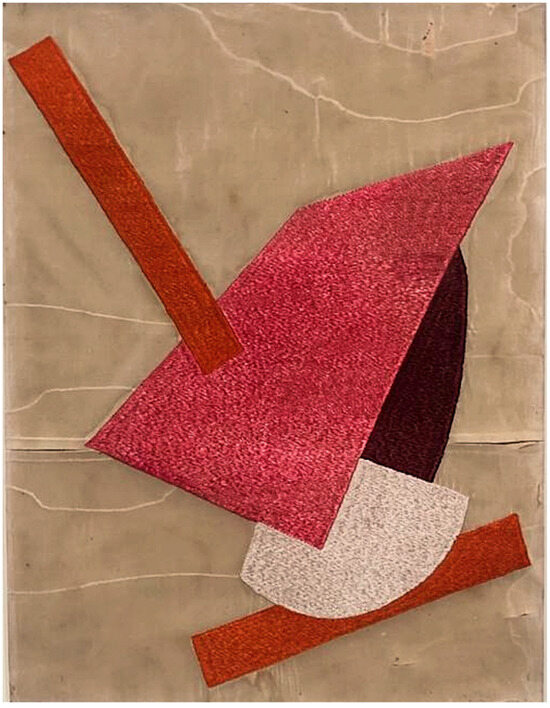

The question arises as to the rationale that prompted some of the most radical artists of the day to engage with folk embroidery, most notably its Ukrainian examples. Exter maintained that decorative designs for embroideries and carpets were legible to contemporary artists because they approached these as colouristic tasks with sophisticated rhythms and complex compositions (Exter 1918, p. 18). In his review of the 1915 exhibition, Tugendkhold grasped a similar intention when stating that ‘[h]ere the non-objective colourfulness returns to its original source’ (Tugendkhold 1915, p. 6). Such an approach also aligns with Malevych’s concept of tsvetopis (colourpainting)—the pure notion of colour obtained once the illusion of depicting things is removed and clear two-dimensional surfaces are used instead (Malevych 1917 in Railing 2014, p. 84).19 In Suprematism, Malevych treated colours as individual units with their boundaries unmixed and clearly separated. It can, therefore, be argued that embroideries allowed artists to inspect the texture of colour, its density, spatiality and mass, thus looking to solve some of the main tasks in twentieth-century painting—the correlation of colours, the texture of volumes and the precise delineation of colour planes. Such work with colour can be examined through a rare survival from the time—the 1916 Suprematist embroidery executed by the Verbivka workshop based on the design of Nina Henke (Figure 8).20 The piece consists of five brightly coloured interlinked geometric forms. There are two inclined orange bars, one placed horizontally at the bottom of the composition and another vertically at the top. The latter pierces an irregular pink rectangle, which dominates the design and is flanked by two semi-circular forms, one of deep burgundy colour and another white. The pink and white forms in particular showcase the effect of light reflecting in the silk threads, adding to the dynamism of the composition, while the density of stitches throughout the embroidery allows for textural depth and volume. The sharp outlines of each form and the interplay of their colours help achieve chromatic saturation and vibrancy. The overall impression is that of radiating colour and dynamism.

Figure 8.

Nina Henke, Suprematist Embroidery, 1916, silk threads on moiré, executed by the Verbivka workshop. Private collection.

The link between Ukrainian embroidery and Suprematism is further emphasized by the fact that the Contemporary Decorative Art exhibition had preceded by one month the opening of The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 in Petrograd, the first public showing of Malevych’s Suprematist canvases. Observing such a timeline, Charlotte Douglas has stated that, ‘Suprematism first appeared in public not as paintings, but as needlework or sketches for needlework’ (Douglas 1995, p. 42). Patricia Railing echoes this, noting that what initially united the artists around Malevych and Suprematism was Davydova’s and Exter’s commission to create Suprematist designs for embroideries to be produced in Verbivka (Railing 2014, p. 60). Malevych was keen for Suprematism to have a broad application outside the constraints of easel painting. The journal Supremus, which he was looking to publish as the voice of the new movement, was meant to include a separate ‘Decorative Section’.21 Malevych, who was born in Kyiv to Polish parents and grew up in Ukrainian villages, was accustomed to Ukrainian peasant art from early childhood. In his unfinished autobiography of 1933, the artist reflected on this exposure, stating that he saw the main difference between country peasants and city workers in the former’s constant engagement with art, be it by painting their houses or creating their own clothes with the use of embroidery (Malevych [1976] 2017 in Bilousova 2017, p. 10). In the same manuscript, he also remarked that his mother was practicing embroidery and lace weaving, the techniques that he learned from her (Malevych [1976] 2017 in Bilousova 2017, p. 19).

The text of the 1933 autobiography was first published in 1976 in Stockholm, prompting the re-examination of Malevych’s early life and the potential influence of peasant art on his artistic development. Dmytro Horbachov, a Ukrainian-Soviet art historian, was one of the first researchers to draw attention to the link between Malevych’s Suprematism and Ukrainian folk art. He has, for instance, stated that ‘[…] the closest analogy to his Suprematism are the geometric paintings in the peasant khaty [Ukrainian peasant houses] of Podilia, Easter eggs with their astrological signs, patterns on plakhtas [traditional Ukrainian female clothing] […]’ (Nayden and Horbachov 1993, pp. 221–22).22 While such a statement may seem conjectural and somewhat unaligned with the broader philosophical musings of the artist, a visual correlation can nonetheless be observed between the stylistic elements of traditional Ukrainian ornament and tenets of non-representational art. Even Kosach used the word ‘non-objective’ when describing ornaments commonly found in traditional Ukrainian embroideries in her 1876 study (Kosach 2018, p. 41). Almost forty years later, in his 1915 thesis ‘From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism’, Malevych would argue for the departure from predmetnost (objectness) and utilitarianism towards the creation of forms that are inherent in the material itself. As such, he propagated the concept of intuitivnyi razum (intuitive reason), which would construct forms consciously yet in a manner unobstructed by utilitarian reason. This in turn would lead to the rejection of the subject, thus releasing the colour and texture, which for Malevych constituted the essence of painting.23

The next, and last, occasion to showcase the collaboration between Malevych’s group and the Verbivka workshop occurred in the winter of 1917 in Moscow, a few weeks after the Bolshevik takeover of the city. The exhibition Verbovka (the Russian-language version of Verbivka) opened at the Mikhailova Salon on today’s Pushkin Street, presenting approximately 400 works designed by sixteen artists and produced by peasant artisans from the workshop. New members of the Supremus Society—Olga Rozanova, Liubov Popova and Nadezhda Udaltsova—joined the group of artists who were involved in the 1915 show. Many of the exhibited items were designed based on the visual vocabulary developed by the Society. While Malevych contributed only three sketches in 1915, two years later he expanded his participation to designs for seventeen items, including nine pillows and four handbags (Douglas 1995, p. 45). An installation shot showing a pillow embroidered based on his work has survived (Figure 9) as well as the painting Untitled (ca. 1916) that exactly matches the design (Figure 10). Based on a newspaper photo from the Contemporary Decorative Art exhibition, Aleksandra Shatskikh has suggested that a sketch of this painting was first displayed at the 1915 show to be then re-worked into a design for the appliqué embroidery exhibited in 1917 (Shatskikh 2012, pp. 88–92). The quality of the cited image makes it difficult to verify this claim, but either a sketch for the painting or the painting itself was likely adapted to create the needlework. Furthermore, the fact that the artist chose to execute the design both as the painted canvas and the embroidered cushion attests to his profound interest in embroidery as an artistic medium. The design presents a complex composition with multiple elements of predominantly orange-red and blue tones, while the two largest components that dominate it by forming a T- or cross-like shape are rendered in deep green and black colours. Since the original cushion has not survived, it is difficult to analyse the difference between the application of colours and the achieved effect in the painting vis à vis the embroidery. However, one notable distinction can be observed: the cushion features cut-out corners that create something like a frame for the composition, which are absent in the painting. It remains unknown whether this was Malevych’s explicit instruction or an initiative on the part of the artisan who sewed the cushion. Another difference between the painting and the cushion is that the latter is a mirror image of the former. Shatskikh explains that the design of the ornament was transferred to the reverse of the fabric with the face side thus becoming a mirror image of the composition (Shatskikh 2012, p. 89). However, the commissioning process and logistics of Malevych’s, and other artists’, collaboration with the workshop require further research to better understand the resulting artistic output.

Figure 9.

Kazymyr Malevych, Suprematist Composition Cushion, 1916, executed by the Verbivka workshop, exhibited at the second Modern Decorative Arts Exhibition in Moscow, 1917, photo credit Oliver Sayler. Online museum UA Heritage: The DNA of Ukrainian Avant-Garde Embroidery.

Figure 10.

Kazymyr Malevych, Untitled, ca. 1916, oil on canvas, 53 × 53 cm. Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York).

The exhibition at the Mikhailova Salon became the last public showing of items produced in Verbivka based on avant-garde designs. With the unfolding of the historical events, 1917 turned out to be the final year of the workshop’s functioning. The Bolsheviks destroyed the estate of Davydova and her family in early 1919 and she immigrated to Germany in 1920. Exter continued to engage with textiles in her work for Nadezhda Lamanova’s fashion workshop in Moscow in the early 1920s, creating constructivist designs while applying elements of Ukrainian folk costumes. Exter left the Soviet Union in 1924 to settle in Paris. The studio in Skoptsi also ceased its operation during the Civil War, with Semyhradova giving away all her lands and relocating to Moscow. From 1918 to 1922, Prybylska oversaw the handicrafts school in Poltava and then also moved to Moscow, where she continued to engage with folk art by organizing exhibitions and running production workshops. She preserved her collection of drawings by Ukrainian peasants that would be donated to the National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art in Kyiv in the 1980s.

The heyday of both the Verbivka and Skoptsi workshops lasted for mere two years. During this time, however, an incredible amount of work was accomplished, leading to the development of new embroidery and new art. Even though there were many alignments in the work of the two workshops, it is also important to acknowledge where they diverged. While Prybylska recognized the need to move away from mere stylization in the production of embroidery, she continued to employ the medium within the limits of representation. Exter and Davydova, on the other hand, explicitly aimed to explore spontaneous co-influences and interactions between traditional Ukrainian embroidery and emerging non-objective art. Hence, their collaboration with Malevych and his associates united under the banner of Suprematism. Even though extensive archival research has already been conducted, allowing to reconstruct this important episode in the development of avant-garde art in Ukraine and Russia, further studies are nonetheless required to better understand the logistics of artists’ collaboration with artisan workshops. The current article, while acknowledging the imperial networks of art production, emphasizes the specificity of the Ukrainian context in the activities of the described studios, thus contributing to the on-going efforts to recognize modernist art produced in Ukraine as an autonomous phenomenon. The fact that the Suprematist embroideries were created in the workshop in Ukraine, under the supervision of Exter and Davydova, attests to the link between the style of embroidery produced in Ukraine and the experimentation with colours and planes that led to the emergence of abstract art.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The first exhibition showcasing avant-garde art in Ukraine was Zveno (The Link; Ukrainian: Lanka) staged in Kyiv in 1908. It was followed by the international Izdebskyi’s Salons presented in Odesa and Kyiv in 1909–1911. Olena Kashuba-Volvach has published a series of articles dedicated to these first avant-garde displays in Ukraine, see Kashuba-Volvach (2008, 2009). For an English-language overview, refer to Kashuba-Volvach’s essay ‘The Beginning: The First Avant-Garde Exhibitions in Ukraine’ in Akinsha et al. (2022), pp. 24–29. |

| 2 | The unrest in the country following the 1905 revolution caused the prolongation of the exhibition’s preparatory stage since it hindered the collection of the needed materials throughout Ukraine. Natalia Davydova made a reference to this effect in her letter to Biliashyvskyi dated 21 June 1905. The Manuscripts Department of The Vernadskyi National Library of Ukraine: holding no. XXXI, file no. 902, sheet 1. |

| 3 | Based on the exhibition documents preserved in the Biliashyvskyi’s archive at the Manuscripts Department of The Vernadskyi National Library of Ukraine: holding no. XXXI, file no. 2704. |

| 4 | Note on transliteration: to show that the discussed figures belong to the narrative of Ukrainian art history, throughout this article I have favoured the Ukrainian versions of artists’ names, except for emigres with well-established reputations in the West, e.g., Alexandra Exter not Oleksandra Ekster. The Cyrillic script has been rendered by a simplified version of the Library of Congress system, dropping the apostrophe that marks a soft sign and giving the initial letter in Ukrainian names as ‘Ye’ rather than ‘Ie’. The exact date of Alexandra Grigorovich’s marriage to Nikolai Exter is unknown, but it appears to have taken place between April and May 1905. She is mentioned as Grigorovich in the list of attendees of the committee meeting for the organization of the 1906 exhibition on 9 April 1905; a month later, on 16 May, she is referred to as Exter. The State Archive of Kyiv, holding no. 304, inventory no. 1, file no. 3, sheets 1–2. |

| 5 | In the early twentieth century, the village of Zoziv was in the Kipovetskii uezd [county] of the Kyiv province; today it is part of the Lypovets district in the Vinnytsia region of west-central Ukraine. |

| 6 | In the early twentieth century, Verbivka was in the Kamenskii uezd of the Kyiv province; today it is part of the Kamianka town in the Cherkasy region of central Ukraine. I take 1912 as the year when the Verbivka workshop was founded from the introductory note in the 1915 exhibition catalogue Contemporary Decorative Art. Embroideries and Carpets Based on Artists’ Sketches. Embroideries created by artisans from Verbivka, however, were featured in the 1906 exhibition at the Kyiv Museum and alternative dates for the workshop’s founding have, therefore, been suggested. Georgiy Kovalenko, for example, mentions that it was set up as early as 1900, see Kovalenko’s essay ‘Natalia Davydova i ee Verbovka’ in Kara-Vasylieva (2009), pp. 29–47. It seems unlikely though that the date would be incorrect in the 1915 catalogue that was authored by Exter. Possibly, individual works by artisans from Davydova’s estate were exhibited in the 1906 show as collected specifically for the exhibition. |

| 7 | For a comprehensive overview of the links between English and Russian revival movements, see Douglas (2006). |

| 8 | For details of other handicraft workshops that were active on the territory of Ukraine in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, see Kara-Vasylieva and Chehusova (2005). |

| 9 | See Akinsha (2020) for a thorough analysis of how the term ‘Russian avant-garde’ was artificially constructed by the Western scholarship and art market. In her pioneering research on Verbivka, Charlotte Douglas, while acknowledging that the workshop was in Ukraine, nonetheless views its activity exclusively through the framework of the Russian avant-garde, see Douglas (1995, 2006). Attempts have been made by scholars from Ukraine, Kara-Vasylieva and Kovalenko in particular, to shift such a focus to recognize the Ukrainian context of the workshop’s operations, see Kara-Vasylieva (2009), Kovalenko (2010), and Kara-Vasylieva and Kovalenko (2018). In Anglophone scholarship, Alla Myzelev has made a rare effort to contextualize the activities at Verbivka and Skoptsi within the political and cultural changes that were taking place in early twentieth-century Ukraine, which she explicitly views as colonized by the Russian Empire, see Myzelev (2007, 2012). |

| 10 | The Ems Ukaz was a secret decree signed by tsar Aleksandr II in 1876, prohibiting the publication and import of any literature in Ukrainian, as well as public readings and stage performances in the language. Ukrainian-language education was also banned. |

| 11 | Because of the Ems Ukaz, it was illegal to publish in the Ukrainian language at the time of the book’s appearance hence it was printed in Russian. Two further editions of the book appeared in 1879 and 1900. All translations from Ukrainian and Russian in this article are by the author, unless stated otherwise. |

| 12 | The historic region of Volhynia, originally part of the realm of Kyivan Rus, was incorporated into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the sixteenth century. After the third partition of Poland two centuries later, the Russian Empire annexed Volhynia to create the Volhynian Governorate within its borders. |

| 13 | Some of the ideas about Exter’s engagement with Ukrainian folk art were first expressed in my forthcoming essay ‘From Kyiv to Paris: The Cosmopolitanism of Alexandra Exter’ in Akinsha et al. (2022), pp. 18–23. This article is a more in-depth study of the subject. |

| 14 | References to this effect were made in some of the reviews of the exhibition preserved in the Biliashyvskyi’s archive at the Manuscripts Department of The Vernadskyi National Library of Ukraine: holding no. XXXI, file no. 2704. For example, in the short note published in Hromadska dumka no. 38, 19 February 1906. |

| 15 | For a contemporary discussion of Exter’s theatre designs, see Tugendkhold (1922) and Efros (1934); for an in-depth art historical study, refer to Kovalenko (1993) and Railing (2011). |

| 16 | In his 1922 monograph on Exter, Yakov Tugendkhold mentioned that she went abroad for the first time in 1907; Georgiy Kovalenko has since discovered new archival evidence confirming that Exter made her first trip to Paris in early 1906 followed by another visit in the spring of 1907. See Tugendkhold (1922, p. 7) and Kovalenko (2010, vol. 1, p. 49). |

| 17 | In the early twentieth century, Skoptsi was in the Baryshivskyi uezd of the Poltava province; today, the village is called Veselynivka and is located in the Kyiv region, an hour away from the capital. |

| 18 | All biographical information on Prybylska has been taken from her Biography. The original text exists as an undated typescript, identified as written in 1944–45, stored in the private archive of Brigitta Vetrova, the daughter of artists Vadym Meller and Nina Henke-Meller. The text of the Biography was published in two issues of the Ukrainian journal Studii mystetstvoznavchi, see Prybylska (2014, 2015). |

| 19 | From Malevych’s manuscript Colourpainting that he wrote in March 1917, following his lecture ‘Betrothed by the Horizon’s Ring and New Ideas in Art: Cubism, Futurism, Suprematism’ in Moscow one month earlier. I have consulted English-language translations compiled in Railing (2014, pp. 83–86). |

| 20 | While numerous sketches by the avant-garde artists have been preserved in public and private collections, only a handful of original embroideries have survived, including two based on the designs of Nina Henke, both now in private collections. |

| 21 | The idea of publishing ‘an Artistic and Literary Journal’ was announced by Malevych during The Knave of Diamonds exhibition in Moscow in November 1916 and reported on in Apollon (November–December 1916). The first issue was due to feature decorative drawings and objects by Davydova, Malevych, Vera Pestel, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. The journal was never published because of the worsening situation due to World War I and the subsequent revolution in 1917. |

| 22 | Podilia is a region in southwest Ukraine, where Malevych spent his childhood while his father was employed to manage the local sugar refinery factories. |

| 23 | These are based on the opinions expressed by the artist in the two editions of his brochure ‘From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism’, first written in June 1915 and published for the opening of the 0.10 exhibition in December 1915, with the revised version appearing in November 1916 for the first showing of Suprematism in Moscow at the 6th Knave of Diamonds exhibition. I have consulted English-language translations compiled in Railing (2014, pp. 20–58), as well as the original Russian-language texts in Malevych ([1915] 2013, pp. 7–35). |

References

- Akinsha, Konstantin. 2020. Naming the Russian Avant-Garde. In Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake. Questions, Research, Explanations. Edited by Rita Kersting and Petra Mandt. Cologne: Buchhandlung Walther König, pp. 146–55. [Google Scholar]

- Akinsha, Konstantin, Katia Denysova, and Olena Kashuba-Volvach. 2022. In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Biliashivskyi, Mykola. 1912. The Peasant Art of Little Russia (The Ukraine). The Studio. Special Issue ‘Peasant Art in Russia’, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chuchvaha, Hanna. 2020. Quiet Feminists: Women Collectors, Exhibitors, and Patrons of Embroidery, Lace and Needlework in Late Imperial Russia (1860–1917). West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Art, Design History and Material Culture 27: 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, David. 1995. The Uses of Peasant Design in Austria-Hungary in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Studies in the Decorative Arts 2: 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Charlotte. 1995. Suprematist Embroidered Ornament. Art Journal 54: 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Charlotte. 2006. The Art of Pure Design. The Move to Abstraction in Russian and English Art and Textiles. In Russian Art and the West: A Century of Dialogue in Painting, Architecture, and the Decorative Arts. Edited by Rosalind P. Blakesley and Susan E. Reid. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, pp. 86–111. [Google Scholar]

- Exter, Alexandra. 1918. Vystavka dekorativnykh risunkov E.I. Pribylskoy i Ganny Sobachko. Teatralnaya Zhizn 9: 18. [Google Scholar]

- Efros, Abram. 1934. Kamernyj teatr i ego khudozhniki 1914–1934. Moscow: Izdanie Vserossiyskogo Teatralnogo obshchestva. [Google Scholar]

- Kara-Vasylieva, Tetiana. 2009. Vidrodzhenni shedevry. Kyiv: Naukovyi druk. [Google Scholar]

- Kara-Vasylieva, Tetiana, and Georgiy Kovalenko. 2018. Zhivopis igloy. Khudozhniki avangarda i iskusstvo vyshivki. Kyiv: Novyi druk. [Google Scholar]

- Kara-Vasylieva, Tetiana, and Zoya Chehgusova. 2005. Dekoratyvne mystetsvo Ukrainy XX stolittia. Kyiv: Lybid. [Google Scholar]

- Kashuba-Volvach, Olena. 2008. Pro pershyi eksperyment modernism v Odesi. ‘Salony’ Volodymyra Izdebskogo. Artistic Culture. Topical Issues 5: 446–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kashuba-Volvach, Olena. 2009. Neochikuvane mystetstvo. Istoriia vystavky ‘Lanka’. Suchasne mystetstvo 6: 266–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kosach, Olha. 2018. Ukrainskiy Narodnyi Ornament. Vyshivka, tkani, pisanki. Original edition 1876. Kyiv: ADEF-Ukraina. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko, Georgiy. 1993. Aleksandra Ekster. Moscow: Galart. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko, Georgiy. 2010. Alexandra Exter. Edition in 2 volumes. Moscow: Moscow Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Malevych, Kazymyr. 2013. Ot kubizma i futurizma k suprematizmu. In Chernyi kvadrat: Manifesty, deklaratsii, stati. St. Petersburg: Azbuka, pp. 7–35. First published 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Malevych, Kazymyr. 2017. Glavy iz avtobiografii khudozhnika. In Malevych: Autobiografichni zapysky 1918–1933. Edited by Anastasiia Bilousova. Kyiv: Rodovid. First published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Myzelev, Alla. 2007. Ukrainian Craft Revival: From Craft to Avant-Garde, From “Folk” to National. In NeoCraft: Modernity and the Crafts. Edited by Sandra Alfoldy. Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, pp. 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Myzelev, Alla. 2012. Handicraft Revolution: Ukrainian Avant-Garde Embroidery and Meaning of History. Craft Research 3: 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nayden, Oleksandr, and Dmytro Horbachov. 1993. Malevych muzhitskyi. Khronika-2000 3–4: 210–31. [Google Scholar]

- Plokhy, Serhii. 2016. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Prybylska, Yevheniia. 2014. Zhizneopisanie. Studii Mystetstvoznavchi 4: 104–13. [Google Scholar]

- Prybylska, Yevheniia. 2015. Zhizneopisanie. Studii Mystetstvoznavchi 2: 111–24. [Google Scholar]

- Railing, Patricia. 2011. Alexandra Exter Paints, 1910–1924. Forest Row: Artists Bookworks. [Google Scholar]

- Railing, Patricia. 2014. Malevich Writes: A Theory of Creativity. Cubism to Suprematism. New York: Artists Bookworks. [Google Scholar]

- Salmond, Wendy R. 1996. Arts and Crafts in Late Imperial Russia: Reviving the Kustar Art Industries, 1870–1917. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salmond, Wendy R. 2002–2003. The Russian Avant-Garde of the 1890s: The Abramtsevo Circle. The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 60–61: 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Shatskikh, Aleksandra. 2012. Black Square: Malevich and the Origin of Suprematism. Translated by Marian Schwartz. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tugendkhold, Yakov. 1915. Vystavka sovremennogo dekorativnogo iskusstva. Russkie vedomosti 2: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tugendkhold, Yakov. 1922. Aleksandra Ekster kak zhivopisets i hudozhnik stseny. Berlin: Zarya. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).