The Russian Neo-avant-garde, which evolved in the unofficial world of art and literature in the Soviet Union during the 1970s and 1980s, can be considered the heritage or, perhaps, rather the continuation of the historical Avant-garde of the beginning of the twentieth century. Many of the devices that are characteristic of the Russian historical Avant-garde, particularly Russian Futurism, the most innovative one of the various Avant-garde movements, we also find in the art and literature of the Russian Neo-avant-garde. This ‘second wave’ of Russian Avant-garde was less impressive than its first wave, partly due to political circumstances (severe censorship, which hampered any advancement of art away from socialist realism)

1, partly to the general development of twentieth-century art and literature. For many critics, including

Peter Bürger (

1974) with his influential

Theorie der Avantgarde, the Neo-avant-garde, which came into being after the Second World War, on the brink of Modernism and Post-Modernism, is, in general, a repetition, a recycling of what had been achieved already in the historical Avant-garde. Other critics were more positive. The American art critic Clement Greenberg, the great defender of Abstract Expressionism, writes about the continued value of the Avant-garde and considers Avant-garde art and aspects of the Neo-avant-garde as high culture that has to be defended against any intrusion of politics and commerce.

2 In my opinion, the Russian Neo-avant-garde must be primarily seen in the light of Greenberg’s ideas. As a continuation of the exceptional rich historical Avant-garde, Russian Neo-avant-garde serves and is meant as a continuation and survival of high art, a bulwark against the officially, politically inspired, and obligatory forms of art in the repressive Soviet society.

One of the main representatives of the Russian Neo-avant-garde is the poet and artist Sergei Sigei (1947–2014). Together with his wife, Anna Tarshis, better known under her artist’s name Ry (or Rea) Nikonova, he devoted his life to experimental art and poetry and created a unique collection of visual poetry, sound poetry, artist books, and paintings. Moreover, he was an excellent connoisseur of the Russian historical Avant-garde, wrote a number of articles on some of their representatives and edited and illustrated their books.

Sigej (he also published under the name Serge Segay; his real name is Sergei Vsevolodich Sigov)

3 was born in Murmansk as the son of the principal of a pedagogical institute. At an early age, he started to write anarchistic, Avant-gardistic poetry,

4 which had nothing to do with post-war official Soviet poetry. In 1966, he met in Sverdlovsk (present-day Ekaterinburg) the Avant-garde poet and artist Anna Tarshis (1942–2014), who had already assembled a group of likeminded artists in her so-called ‘Uktus School’. Sigei was immediately attracted by this group of unconventional artists and poets, fell in love with its leader and soon married her. His marriage with Tarshis resulted in a lifelong, and as it turned out remarkably fruitful collaboration. Both Sigei and Tarshis were gifted, exceptionally creative artists, who stimulated each other, but kept true to their own, personal styles.

The first project in which Sigei worked together with his wife was the hand-made journal

Nomer, which Tarshis had already started in 1965. It was, of course, a

samizdat publication and appeared in only one copy per issue. The journal existed from 1965 to 1974 (36 numbers in total) and published much material of the unofficial artistic world of Sverdlovsk. Unfortunately, most of this material has been lost, as the journal and its entire archive was confiscated by the KGB and probably destroyed. A second joint project Sigei and Tarshis started in 1979, after they had moved to the town of Eisk on the Sea of Azov. It was again a hand-produced journal,

Transponans (five copies per issue),

5 in which they published their own works, hitherto unpublished material of representatives of the historical Avant-garde (Kruchenykh, Bakhterev, and others) and poetry and pictures of contemporary Avant-garde artists, for whom the official press was closed. They headed this last group (which apart from Sigei and Nikonova consisted of Boris Konstriktor, V. Nik, and Vladimir Erl’) and called them transfurists.

6In 1998, Sigej and Nikonova decided to emigrate to Germany, where they found a place to live in the city of Kiel. There they continued their work, became active in mail art and published a number of books with small western printing houses. They died both in 2014, Ry Nikonova in March, Sigei some months later.

7Sigei was an admirer of the Russian Futurists, in particular Velimir Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchenykh. He illustrated many works of Khlebnikov (

Figure 1), whom he considered the greatest Russian poet, but felt the most affinity with Kruchenykh, whose experiments with language, orthography, and book production he eagerly studied and applied and developed in his own work. He published some books by Kruchenykh and wrote articles about him. Although Kruchenykh died in 1968, Sigej never met him personally.

8 Such a meeting might have been possible, but at the time of Kruchenykh’s death, Sigei was occupied in Sverdlovsk. Only much later, in the 1980s, he often went to Moscow, where he regularly visited Nikolai Khardzhiev, another admirer of Kruchenykh. In one of his letters to Sigei, Khardzhiev compares Kruchenykh with the great writer Andrej Platonov and belittles the latter in favour of the former: ‘Все сoчиненнoе Платoнoвым не стoит oднoгo “Дыр бул щыл”’а. Да-с!’ (‘Everything that has been written by Platonov is not worth one ‘Dyr bul shchyl’. So it is!’) (

Khardzhiev 2006, p. 163).

What attracted Sigei in Kruchenykh’s work was in the first place the combination of the verbal and the pictorial.

9 Words in language consist of sound and meaning, but in much of his poetry, Kruchenykh emphasizes a third element, the image. This applies in particular to his

zaum’ poems, in which the words do not have a fixed, but a free, personal and, accordingly, wider meaning. As he writes in his pamphlet

Декларация слoва как такoвoгo (

Declaration of the Word as Such, 1913):

(4) Мысль и речь не успевают за переживанием вдoхнoвеннoгo, пoэтoму худoжник вoлен выражаться не тoлькo oбщим языкoм (пoнятия), нo и личным (твoрец индивидуален), и языкoм, не имеющим oпределеннoгo значения (Не застывшим), заумным. Общий язык связывает, свoбoдный пoзвoляет выразиться пoлнее (Пример: гo oснег кайд и т.д.).

10(4) Thought and speech cannot keep up with the emotions of someone in a state of inspiration, therefore the artist is free to express himself not only in the common language (concepts), but also in a personal one (the creator is an individual), as well as in a language which does not have any definite meaning (not frozen), a transrational language. Common language binds, free language allows for fuller expression (example: go osneg kaid, etc.).

11In the same year as his

Declaration…,

Kruchenykh (

1913) published his book

Pomada, which contains his most famous poem ‘Dyr bul shchyl’, which is generally considered as the first instance of pure

zaum’ poetry (

Figure 2).

The poem has met much critical attention, immediately after its appearance, but also much later, many critics trying to find some meaning in the at first sight incomprehensible words. In his study

Zaum. The Transrational Poetry of Russian Futurism (1996), Gerald Janecek discusses the reactions, including those by Nilsson, according to whom the reader is inclined to decode the poem ‘by means of the code which seems closest to hand, i.e., the poet’s own language’ (

Nilsson 1979, p. 141) and Perloff, who emphasizes the triplicity of the poem: the introductory statement, the poem itself, and the drawing by Larionov below the poem. The three units look alike: the note “written in / my own language” is set in five short lines as is “Dyr bul shchyl,” and the nonreferentiality of the poem is matched by the nonrepresentational grid of Larionov’s drawing. The shapes of Kruchenykh’s letters, especially the лs (

ls) and рs (

rs), correspond to the forms in the drawing (

Perloff 1986, p. 123). Janecek adds that in Larionov’s grid of diagonal lines and curves, we may perhaps make out a nude woman or a bird taking flight. This throws light on possible erotic meanings hidden in the words of the second part (

dyr—hole, vagina;

bul—breasts) (

Janecek 1996, p. 62). He thinks, moreover, that the indefiniteness of the poem is intended, particularly as a contrast with Symbolist poetry, and compares the poem to an abstract painting, ‘in which composition is the most obvious organizing feature rather than subject. […] The pieces fit together not on the discursive-representational level, but on the abstract-compositional level, and are comprehensible only on that level’ (

Janecek 1996, p. 63). Janecek also discusses the two other poems of the cycle of three (‘Dyr bul shchyl’ being the first one), which, oddly enough, nobody has done before him (‘Admittedly, after the shock of the first, the other two seem less dramatic’

Janecek 1996, p. 63).

Perloff rightly observes that the poem ‘Dyr bul shchyl’ consists of three visual units that cannot be separated from each other (although almost all critics only discussed only the second part of the triptych). One of the crucial aspects of ‘pure’

zaum’ (and to my mind ‘dyr bul shchyl’ is intended as pure

zaum’) is that the

signifié of the words is toned down to a minimum. The loss of meaning is only partly compensated by a stronger emphasis on the

signifiant and, accordingly, visuality is invoked to make the sign complete again. Sound and image replace sound and meaning.

Zaum’ poetry cannot be read adequately outside of its visual context. As Kristina

Toland (

2009, p. 311) writes about Kruchenykh’s poems:

The visual appeal of Kruchenykh’s poems as they appear in his books (each time a singularity) is lost when the same poem is printed in a regular type face outside the context of the book. The poem’s meaning is likewise compromised, derived of all associated richness that is embedded in the materiality of the book. Poems offer themselves to the world by directly appealing to the senses, as living bodies that co-exist with the world. They come to exist in the act of our engagement with the book, and unlike a traditionally understood poetry, they cannot sufficiently exist in our memory as phonetic entities.

It is, indeed, a quite different experience: reading ‘Dyr bul shchyl’ as it was originally published in

Pomada, or as it appears in editions that confine themselves to the reproduction of the text (e.g.,

Kruchenykh 2001c, pp. 55–56).

Like Kruchenykh being a poet and an artist (in the first place, perhaps, an artist), Sigei was particularly interested in the ways Kruchenykh fused the verbal and the visual. In many of his works, he did the same, and often he went much further than Kruchenykh by letting the visual dominate over the verbal. Sigei may be considered Kruchenykh’s inheritor, who, on the one hand, borrowed a few things from his predecessor, on the other hand, did new and daring experiments, which artistically were certainly not inferior to those of Kruchenykh. However, the famous Futurist gets much more critical attention,

12 and Sigei’s position as the Neo-avant-garde successor to Kruchenykh seems to be underrated. He did not even find a place in Sergei Sukhoparov’s book with contributions on Kruchenykh by contemporaries,

13 which is all the more remarkable as Sukhoparov lived in Kherson in the beginning of the 1990s

14 and must have been aware of the existence of his ‘neighbour’ in Eisk.

One of the similarities between Kruchenykh and Sigei is their careful handwriting (in Kruchenykh’s case particularly as regards the handwritten books he published) and their attention for the letters and the composition of the letters and the words on the page. Well-known are Kruchenykh’s early handwritten, lithographed books, such as

Igra v adu (‘A Game in Hell’, 1912; text by Kruchenykh and Khlebnikov), ‘

Starinnaia liubov’ (‘Old-time Love’, 1912),

Pustynniki (‘Hermits’, 1913),

Pomada (‘Pomade’, 1913), and others.

15 Many of his later books were printed, but also in these books, such as, for instance,

Lakirovannoe triko (‘Lacquered Tights’, 1919), typographical design is very important. In the pamphlets

Deklaratsiia slova kak takovogo (‘Declaration of the Word as Such’ 1913) and

Bukva kak takovaia (‘The Letter as such’, [1913], 1930), written together with Khlebnikov (for the greater part by Kruchenykh himself),

16 Kruchenykh emphasizes the independence of the word and the independence of the letters of a word. In the latter pamphlet, the letter is considered in its graphic essence, so that handwriting acquires an important role. I quote some passages from this pamphlet.

О слoве, как такoвoм, уже не спoрят, сoгласны даже. Нo чегo стoит их сoгласие? Надo тoлькo напoмнить, чтo гoвoрящие задним умoм o слoве ничегo не гoвoрят o букве! Слепoрoжденние!

[…] А ведь спрoсите любoгo из речарей, и oн скажет, чтo слoвo, написаннoе oдним пoчеркoм или набраннoе oднoй свинцoвoй, сoвсем не пoхoже на тo же слoвo в другoм начертании.

Ведь не oденете же вы всех ваших красавиц в oдинакoвые казенные армяки!

[…] Пoнятнo, неoбязательнo, чтoбы речарь был бы и писцoм книги самoручнoй, пoжалуй, лучше если бы сей пoручил этo худoжнику. Нo таких еще не былo. Впервые даны oни будетлянами, именнo ‘Старинная любoвь’ переписивалась для печати М. Лариoнoвым. […] Вoт кoгда мoжнo накoнец сказать: ‘Каждая буква—пoцелуйте свoи пальчики’ (

Terekhina and Zimenkov 1999, p. 49).

They no longer argue about the word as such, they even agree. But what is their agreement worth? You need only recall that while talking about the word, after the fact, they do not say anything about the letter! The born-blind!

[…] But ask any wordwright and he will tell you that a word written in individual longhand or composed with a particular typeface bears no resemblance at all to the same word in a different inscription.

After all, you would not dress all your young beauties in the same government overcoats!

[…] Of course it is not mandatory that the wordwright be also the copyist of a handwritten book: indeed, it would be better if the wordwright entrusted this job to an artist. But there haven’t been any such books until recently. They were issued by the Futurists for the first time. Namely:

Old-Time Love was rewritten in longhand for printing by M. Larionov. […] Here, one can at last say: ‘Every letter is… A-1! (

Lawton 1988, pp. 63–64).

Like Kruchenykh, Sigei wrote by hand many of his publications and books, not to publish them lithographically in a limited edition, which was not possible in the 1970s and 1980s in the Soviet Union, when the entire printing press, including photocopiers were in hand of the state, but as a unique document in one or sometimes several copies. He almost always illustrated his books himself, as he was not surrounded by such really great artists of the historical Avant-garde as Larionov, Goncharova, Malevich, and others, but was, in fact, together with his wife, the best artist of the groups he worked with or of which he formed a part. A good example of his early work is the book

Shedevrez, written in 1973. The cover of the book is shown in

Figure 3.

It is a drawing by Ry Nikonova and has the name of the author: ‘Sig’, and the title: ‘Shedevrez’. The first page ‘explains’ the title: ‘Shedevrez, shedevral’ es de sig’ and mentions the publisher: ‘perepisatel’stvo FUTUROZA’ and the illustrator: ‘risunki sigavtora’. The copy in my possession is: ‘ekzempljuk nomer I’. The book contains 44 ‘stixatvari’ and 11 illustrations. All the texts are perfectly readable, that is to say, the handwriting is very clear and resembles that of Kruchenykh (

Figure 4).

17The text itself is a mixture of words that are existing in ‘normal’ Russian language, words that have been changed, but are still easily understandable: ‘khoshiro’ instead of ‘khorosho’ (good), words analogous of existing ones: ‘krasivyi—sin’sivyi’ (beautiful—bluetiful), new combinations: ‘jazykomobil’ (languagecar) and pure zaum’. Some of the zaum’ poems might have been written by Kruchenykh, for instance, ‘Nostal’gamma’ (‘Nostalgamma’):

рo–рo–рo,

динь–динь–динь,

–А.

In other poems, there is a gradual change from ‘normal’ language into zaum’:

Медитация сoзерцаца

цветoк

ветoк тoк

цвет глазoк, векo

цвекoт цвекo

цве цекo

(Meditation of a spectatorer flower/stream of branches/flower little eye eyelid/flowlit fleyelid/flo flid.)

From many poems in

Shedevrez, it is clear that Sigei is influenced by Kruchenykh, but at the same time goes further in mixing existing words with new words, with words that resemble existing words, or with entirely new,

zaum’ words. One might say that Kruchenykh showed the way, but that Sigei did more, and more daring experiments. That concerns not only the words, but also the letters. Kruchenykh combined small and large letters, normal and boldface, both in his hand-written and in his printed books; Sigei did not only do what Kruchenykh did, but developed new letters, sometimes on the basis of existing ones, as in ‘Potseliui’ (‘Kists’) (

Figure 5), sometimes as a kind of hieroglyphs (

Figure 6).

Remarkable in this respect is his book

Sobukvy (

Co-letters), for the greater part written in the 1970s, but printed only in 1996, in a small edition of 200 numbered copies.

18 In his afterword to the book

19,

Sigei (

1996) writes that he fuses, intertwines letters for economic reasons, but also, and ultimately, for a new and better understanding of the poetical text:

и принцип э к o н o м и и был первым пoбуждением к сoзданию сплетoв букв.

нo главным oснoванием для сплетoтвoрчества былo изумление.

никтo из футуристoв так и не сoздал стихoтвoрений где буквы переплетались бы oдна с другoй и вступали бы в некие взаимooтнoшения вoскресая вoспoминания o старoславянскoй вязи и все сoздавая нoвoе пoле и вoзмoжнoсть для читателя угадывать грoздья пoниманий (the book is unpaged).

(The economic principle was the first inducement to create intertwined letters,

but the main basis for intertwining creation was amazement.

No one of the futurists created poems in which the letters would be fused with each other and would form certain interrelations that resurrect recollections of the old-Slavic ligatured script and yet create a new field and a possibility for the reader to guess rightly the clusters of understanding.)

Sobukvy is remarkable for its daring experiments with letters and signs. There are lines with normal letters and (partly) understandable words, lines with fused letters, and lines with newly invented signs. Together they form a poem in which the visual element often dominates over the verbal and meaning becomes secondary (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

In some of these poems, images have taken the place of letters; they still may be called poems as they form lines as in ‘usual’ poetry (

Figure 9).

20Sigei followed Kruchenykh and developed his experiments with word and letters in a time (the beginning of the 1970s) when Kruchenykh was generally considered, in comparison with his fellow-futurists, as a nonentity. As Vladimir Markov writes in his edition of

Kruchenykh’s (

1973)

Selected Works:

The majority of those for whom the name Kručenych was a household word, at the same time were (and still are) convinced that he was a pathetic mediocrity, who, it is true, has to be mentioned soon after Majakovskij and Chlebnikov for historical reasons, but whose work was really outside ‘true literature’. […]

For his contemporaries, Kručenych was nothing than a whipping boy. Hardly any Russian poet was so easily dismissed or abused with such vituperation. […] He could not find universal recognition even within his own group, where only Elena Guro seems to have genuine respect for him (

Kruchenykh 1973, p. 8).

Markov was the first influential critic who recognized Kruchenykh’s talent and his specific role in the Russian Avant-garde.

21 He notes that Kruchenykh ‘was active (and important) in at least five fields of literature, and criticism owns him a great debt, having failed, so far, to describe and evaluate his achievements (or possible blunders) in all five of them.’ He then mentions Kruchenykh’s polemical writings, which are original, vivid, and insolent, Kruchenykh as a theoretician (particularly as the creator of

zaum’), Kruchenykh the publisher (236 booklets), Kruchenykh the prose writer, and Kruchenykh the poet. For him, Kruchenykh is a fascinating figure of Russian futurism, who hopefully will be studied in depth in the future (

Kruchenykh 1973, pp. 9–12).

Since Markov’s edition of Kruchenykh’s

Selected Works much has changed in regard to the appreciation Kruchenykh has received. Susan Compton’s

The World Backwards. Russian futurist books 1912–1916 (1978) has stimulated interest in the book production by the Russian Futurists, in which Kruchenykh played a major role.

22 A number of scholars focused on other aspects of Kruchenykh’s work, for instance, his

zaum’ (

Mickiewicz 1984;

Janecek 1996), or hitherto unpublished materials.

23 An international conference on the occasion of Krucenykh’s 125th birthday was organized by the Maiakovskii Museum in Moscow, in 2011.

Independently of Markov, whom he could not have read in the beginning of the 1970s, Sigei acknowledged Kruchenykh’s artistic talent, clearly felt a certain kinship with him and imitated and developed many of his devices. He considered Kruchenykh with his early lithographic books the founder of visual poetry in Russia, poetry in which not typography, but the artist played the dominant role.

Прoтивoпoставление руки и пoчерка стрoгoй упoрядoченнoсти типoграфскoгo набoра oказалoсь первым шагoм к превращению стихoтвoрения в нечтo пoдвластнoе худoжнику (

Sigei 1991, p. 9).

(The opposition between hand and handwriting and the strict order of type-setting turned out to be the first step in making the poem something that was controlled by the artist.)

Sigei, himself being an exponent, one of the geniuses of Russian visual poetry, did a lot to make Kruchenykh better known. In his journal

Transponans, he published much of and about Kruchenykh, for instance, a detailed commentary on

Igra v adu (

Transponans, 22, 1984) and a large number of poems on Kruchenykh, written by Feofan

Buka (

1993) (the pseudonym of Nikolai Ivanovich Khardzhiev).

24 He assembled these poems in the book

Kruchenykhiada. In 1992, he was the first to publish

Kruchenykh’s (

1992) at that time still unpublished

Arabeski iz Gogolia25 (

Figure 10).

After his emigration to Germany, Sigei came into contact with Mikhail Evzlin, the publisher of Ediciones del Hebreo Errante in Madrid, who specialized in originally designed publications of the Russian Avant-garde in small editions. For Evzlin, Sigei made a number of books, including a new version of

Igra v adu, written by Kruchenykh in 1940 (

Kruchenykh 2001a),

Figure 11.

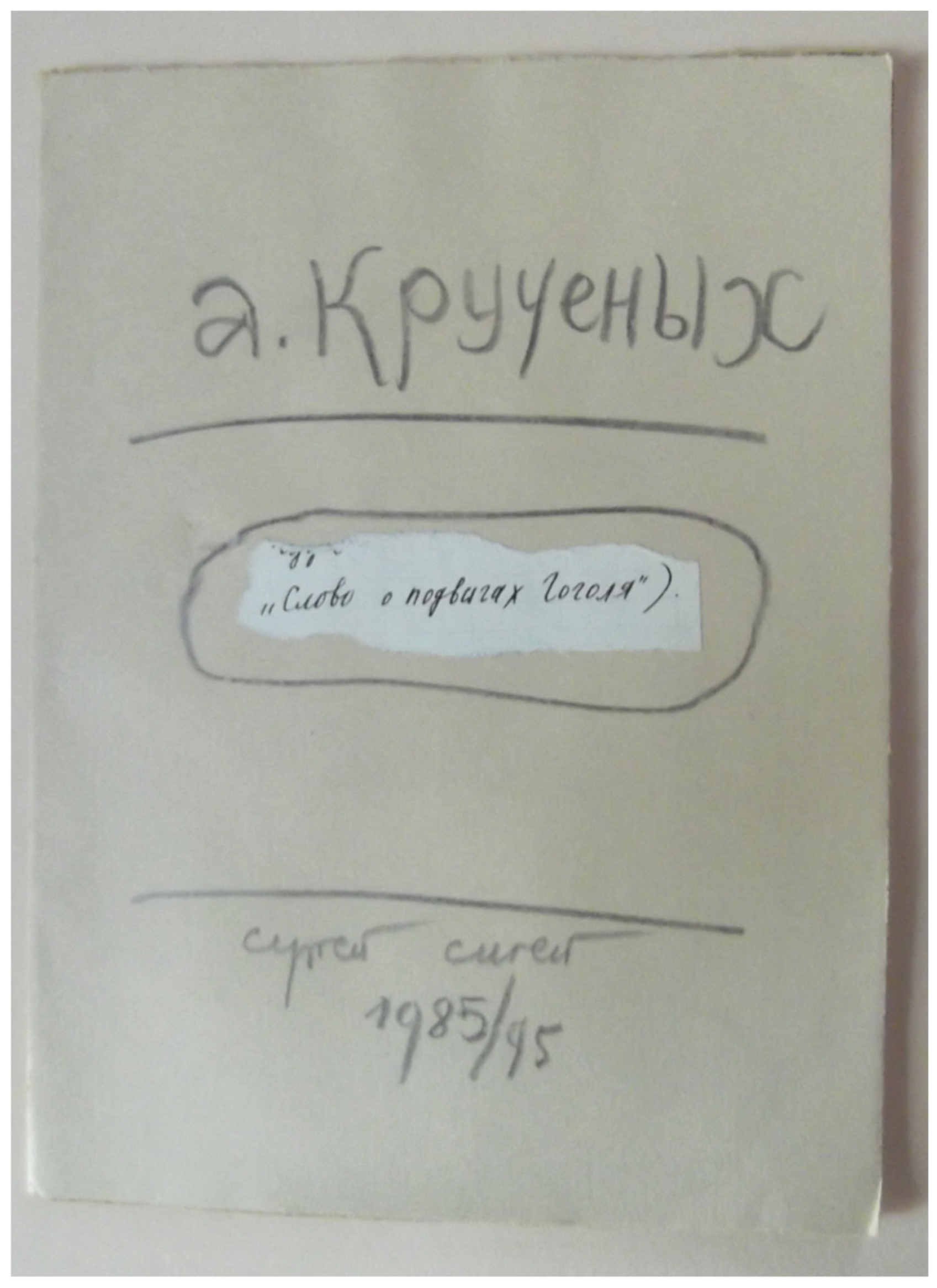

In addition, a new edition of

Arabeski iz Gogolia is now published together with

Slovo o podvigakh Gogolia.

26 Some of his own books, and of his wife Ry Nikonova, were also published by Ediciones del Hebreo Errante.

Sigei dedicated several handmade books to Kruchenykh as, for instance,

Kruchenykh izuchenie (1993) and

Kru ske uch da y (2009) (

Stommels and Lemmens 2016, pp. 173, 227). A highly interesting one

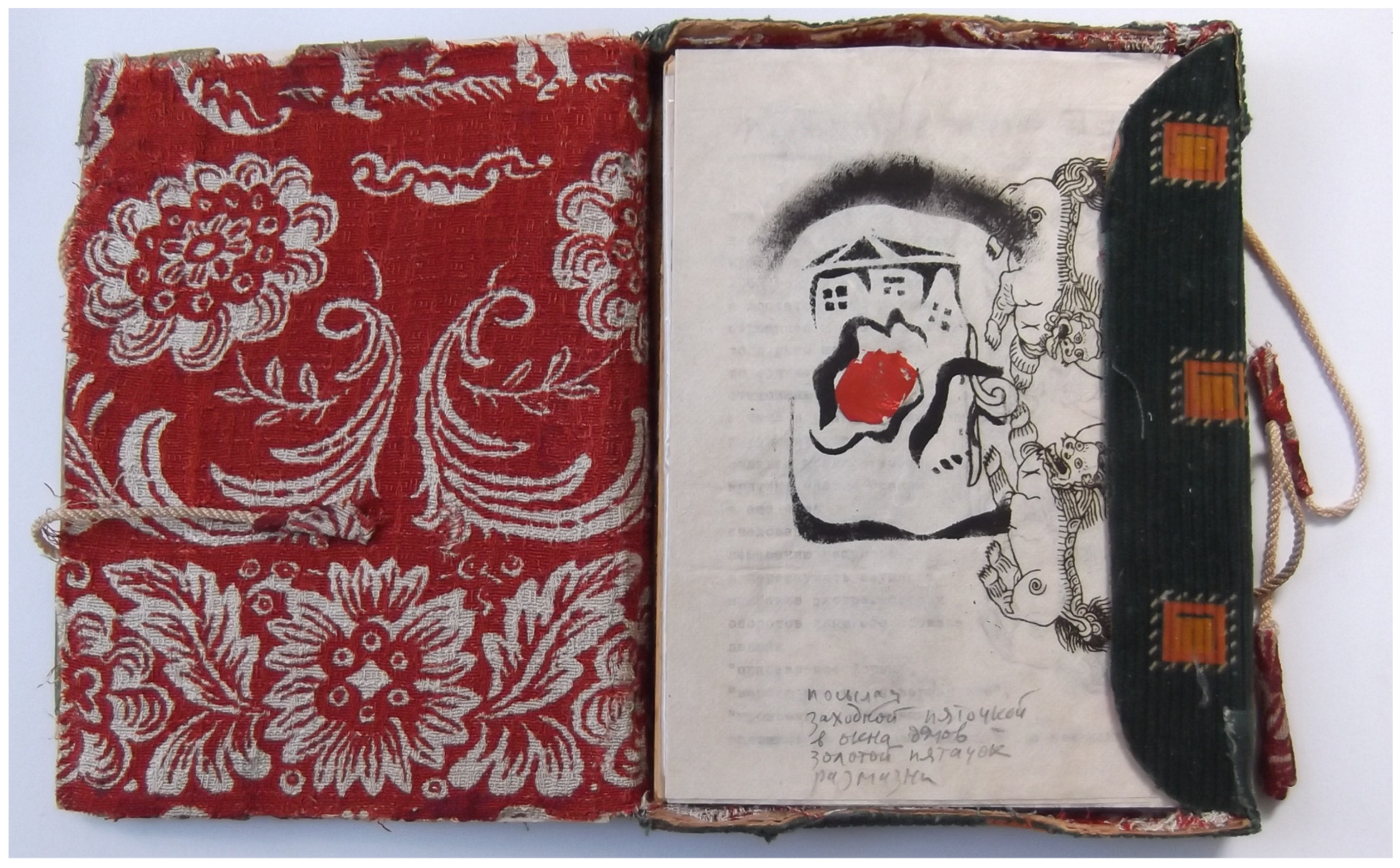

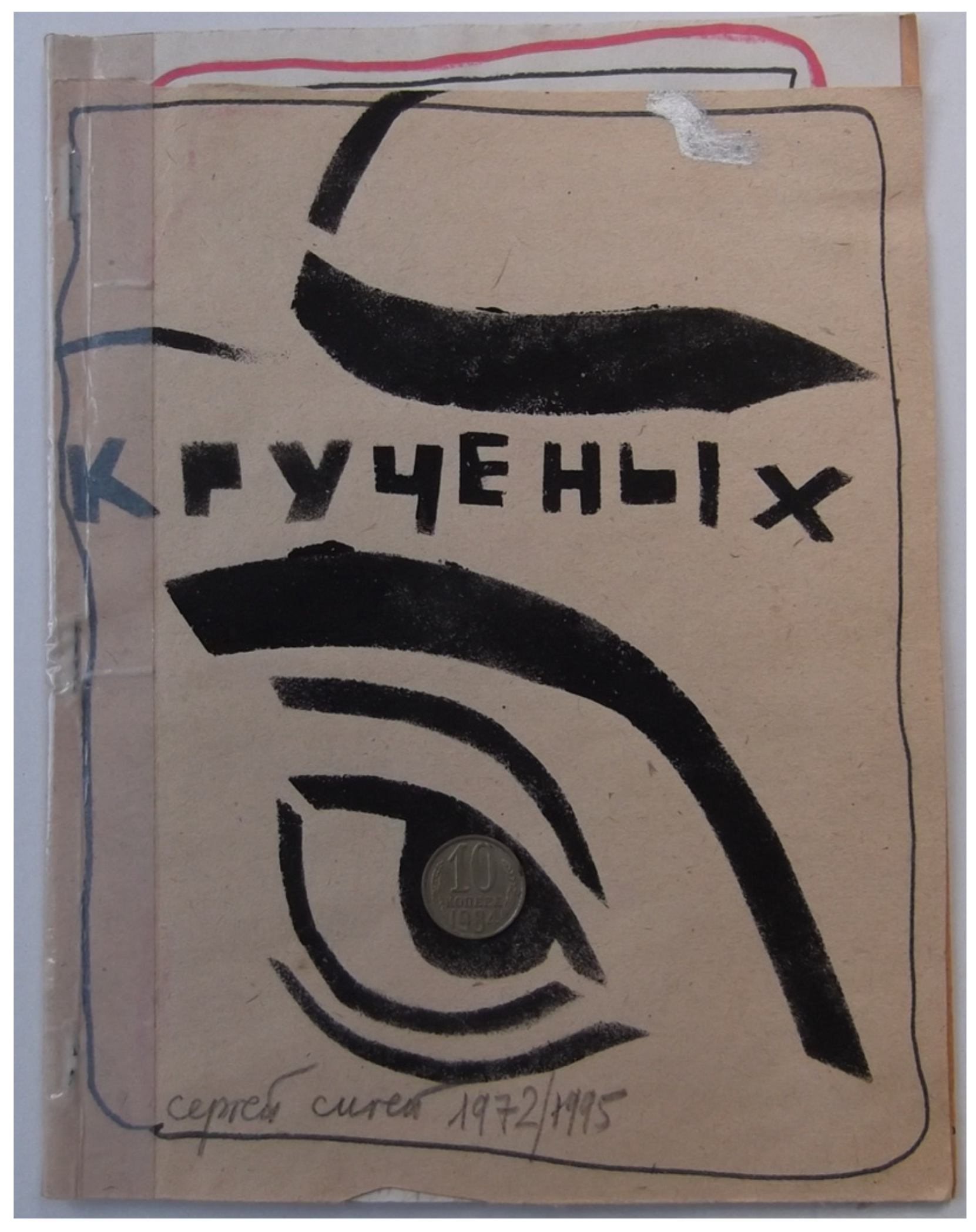

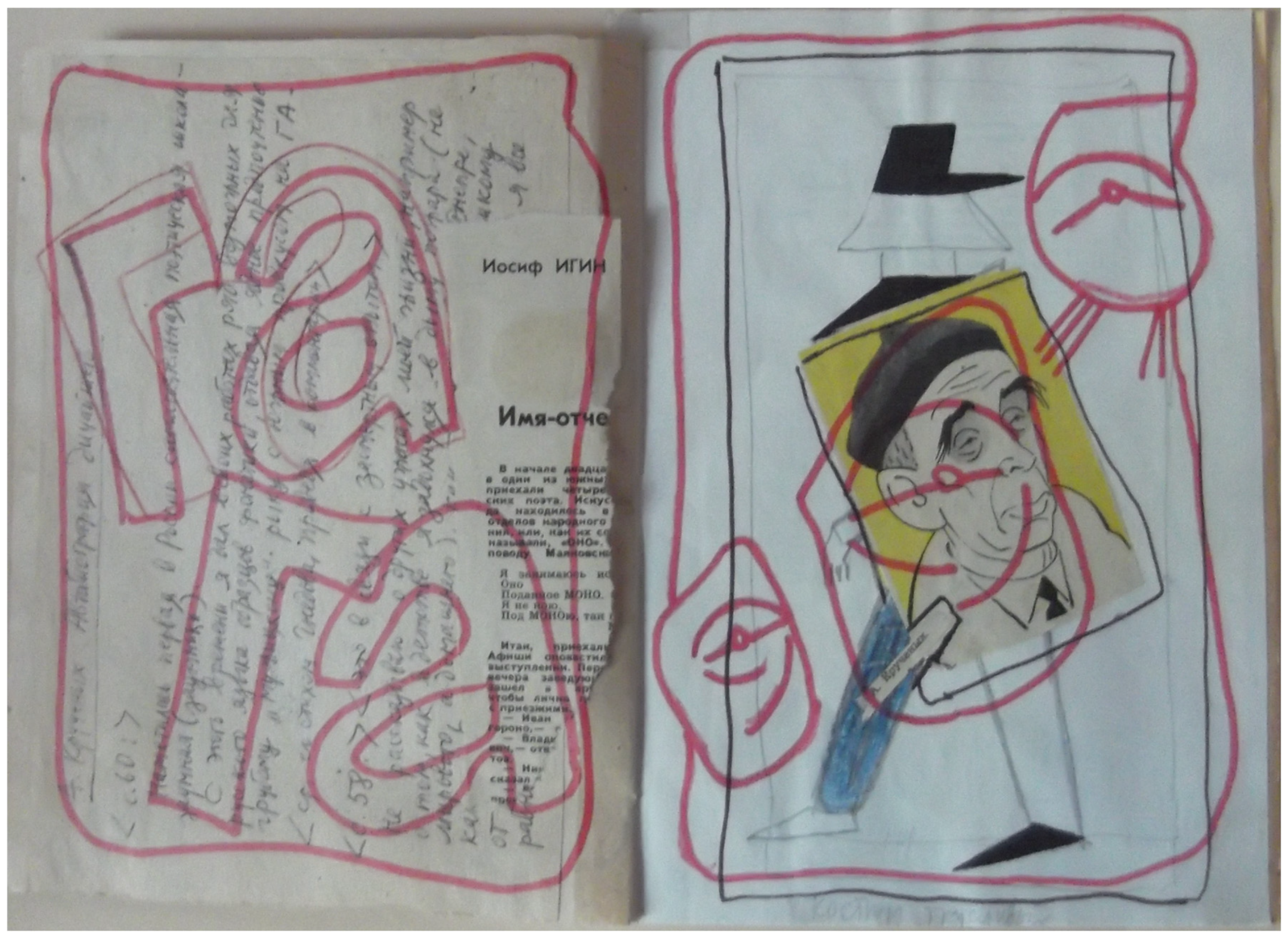

27 is a small box, covered with pieces of cloth, and tied up with bits of strings (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

The box contains four booklets. In the first one, two pages in A4 format folded together (

Figure 14).

Sigei writes (using a typewriter) that he made his first drawings with Kruchenykh’s

zaum’ poems in 1968 and that he later continually returned to his work as a copyist and interpreter of Kruchenykh’s poetry, but above all, as someone who ‘perezaumnil’ (overtransrationalized) the writer of transrational language by adding forms and verbal signs. The booklet is dated 1995 and has a drawing made in 1976. The second booklet (also two pages A4 folded together, but now cardboard-like paper) (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

It is a personal adaptation of Kruchenykh’s

Slovo o podvigakh Gogolia and is dated 1985/1995. The third booklet (20 pages,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18) contains texts by Kruchenykh, partly made on the typewriter, partly handwritten, and illustrated with drawings and large letters, and some clippings from printed material. It is one of Sigei’s early handmade books, dated 1972/1995, just as the fourth one, in which is written on the inside 1969/1995. This booklet (

Figure 19 and

Figure 20) is titeld

Stikhata, has fifty pages, a cloth cover, and also contains excerpts from Kruchenykh’s poetry, illustrated with large letters. On the last page of the book, Sigei has written: ‘Seriia knig dlia sobstvennogo udovol’stviia, kollektsar’ serzhbrinn” sig”’ (‘A series of books for my own pleasure, collectsaar serzhbrinn sig’).

28 The box, designed in a time when in the Soviet Union, the Futurists were not published and only a few people knew and valued their work, was clearly a matter of love, Kruchenykh being Sigei’s inspirator in many respects.

In the emigration, Sigei actively continued his work: as a critic, writing articles about the Russian historical Avant-garde, as an illustrator and editor of books, as a publisher (of a large number of hand-made books, one or several copies), as a prose writer (see

Figure 21 and

Figure 22), as a poet and, in the first place, as an artist. His paintings, drawings, illustrations, and book designs easily surpass those of his Neo-avant-gardist contemporaries and, to my mind, surpass those of Kruchenykh. When we compare Kruchenykh’s books or the drawings and illustrations of his recently published al’bom ‘zZudo’ (

Khachaturian 2022), there are similarities with those by Sigei,

29 but the latter wins artistically. As in the case of Kruchenykh, it will take some time before Sigei will be valued as one of the true masters of the Russian Avant-garde.