Abstract

This article explores how competing images of Jewish corporeality and gendered identity are emerging in Israel through classical ballet by religious girls and women. It traces the cultural, political, and religious implications of this in the context of masculine Zionist ideals of the valorization of the corporeal. Focusing on a group of pioneering Israeli women it traces how they have reshaped the study of ballet into a liberatory yet modest practice for Orthodox women across a range of Israeli religious communities. The revolutionary efforts that linked the founding of the state of Israel with a new body are viewed through a revised feminist perspective, one within the paradigm of a religious counterrevolution. Just as the laboring body of the secular folk dancer of the Yishuv has stood for socialism, egalitarianism, and muscular Judaism while relegating the religious body to the sidelines, it is possible now to read an image of the return of the religious, via the feminized body of classical ballet, as emblematic of the new Jewish woman of Orthodox communities. I argue that through the study of ballet a politics of piety is operating among Orthodox Jewish women making it a medium through which they are changing assumptions about agency, patriarchal norms, and nationalist politics.

1. Introduction

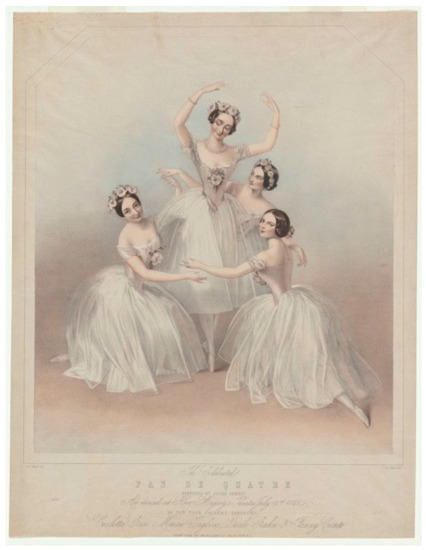

It is Autumn 2010, and I am nearing the end of several months of living in Jerusalem on a Fulbright Fellowship. I’ve spent time guest lecturing at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance and interviewing emigrees from the Former Soviet Union about the historic dearth of ballet in Israel. Most importantly, I am seeing as much local dance as I can, the majority of it contemporary. One afternoon I accompany a colleague to an informal modern dance showing in a busy studio in a Haredi neighborhood, Shoshi Broide’s Dance School, Zichron Yakov Street, Romemma, Jerusalem. While I wait for the demonstration to begin, a small flyer on a bulletin board in the lobby of the studio catches my attention. This flyer (Figure 1) advertises an upcoming concert with an image that is instantly familiar: a copy of the iconic lithograph for Jules Perrot’s 1845 ballet, Pas de Quatre. I am puzzled why here of all places I should find a reference to ballet and curious why such a choreographically conservative work had been chosen to market the event. I knew the ballet and this lithograph commemorating it well, and I knew it was generally regarded by dance historians as a minor piéce d’occasion for the four reigning ballerinas of the Romantic Era. Yet, as I studied the flyer, I discovered it had been curiously modified. A.E. Chalon’s original print (Figure 2) captured the celebrity Romantic ballerinas of the era; Carlotta Grisi, Marie Taglioni, Lucille Grahn and Fanny Cerrito, arranged coyly kneeling together in the pose that opens and closes the ballet. In the original lithograph the women’s thighs and legs are teasingly visible through their gauzy tulle skirts and the plump white flesh of their breasts peek out from low bodices while their bare arms softly entwine as the women gaze seductively toward the viewer. The version before me in the Jerusalem dance studio, however, was deliberately altered from this original.

Figure 1.

Poster for Concert.

Figure 2.

Original Pas de Quatre Print.

I study the flyer more intently, parsing the strange tension it displays compared to the original poster. The designer of the flyer has added an entirely new layer of body concealing undergarments: slips, long sleeves and high necklines to shield the very flesh and sexualized parts of the female anatomy the original flaunts. This remade image represents the collision of Jewish Orthodox codes of modesty for covering women’s bodies bumping up against the physical display of women’s bodies that traditional ballet champions. Through this image the secular and flirtatious Romantic ballerina has undergone a metaphoric conversion into Orthodox Judaism, effectively from the gender codes of one sisterhood into the equally proscribed rules of another. In donning the Orthodox woman’s modesty preserving clothing, which includes concealing the bare flesh of female arms to below the elbows, raising necklines to above the collarbone, and covering legs down to the midcalf, and the hair with a wig or scarf if one is married, the image of the Romantic ballerina in this flyer deliberately mutes the body parts deemed sensual in the female dancer during the nineteenth century. The designer of the flyer has not only filled in the customary transparent tulle skirt, so the contours of the women’s thighs are no longer discernable but even the sly smiles and flirtatious eyes of the ballerinas in the original print seem ever so slightly muted and de-sexualized into a downward rather than outward gaze. The figures’ make-up is lightened, and the original sensuously full pink lips have been narrowed into a more serious colorless line.

Next to this image a text in Hebrew reads:

“Divertissement: The “Religious Girls Dancing Ballet Project Under the artistic direction of Nadya Timofeyva Supported by the Dance Department-Office of Culture and Sport and the Jerusalem Fund [in bold]:Performance intended for women onlySunday 9 December 2010, 12 Tevet 5771 at 22:30 Rebecca Crown Hall, Jerusalem Theatre”

I am intrigued. Here is a pairing of the dance genre I had been searching for–ballet but performed by a community I had never considered: “Religious Girls”. I have so many questions: I wonder how these regulations competing for control of the female body represented here negotiate obedience to a Jewish past through religion and at the same time summon toward a Jewish future through ballet. I ponder why this specific image was deliberately chosen to gesture toward ballet and at the same time to mute that reference by rescripting it to conform to Jewish Orthodox codes of extreme modesty in attire and self-presentation. What is the significance of this taking place in the holy city of Jerusalem in 21st century Israel?

A few days later I am part of a dense crowd of women and girls jammed into the small downstairs lobby of the Rebecca Crown Theater in Jerusalem, part of the fortunate who have secured a ticket to the sold-out concert of Religious Girls Dancing. As the start time for the concert arrives the lobby doors to the theatre remain closed and the feeling of anticipation in the crowd heightens as new arrivals without tickets search for anyone selling extras. Only women, and boys under the age of 5, are permitted to observe the performance and once the doors finally open everyone spills inside filling the 1000 seats quickly. It is clear that not just this debut performance of the religious women dancers of Nadya Timofeyeva’s Jerusalem Ballet Center itself is of interest but the very occasion of it happening at all is clearly consequential.

The mixed repertory evening program presented a range of brief and clearly adapted ballets, all modified versions of repertory staples, presumably to avoid a minefield of copyright issues. They included a small cast dancing some ensemble phrases that strongly resembled George Balanchine’s Serenade; a woman’s variation with the buoyant styling of August Bournonville’s choreography; and snippets resembling Michel Fokine’s Les Sylphides, and his The Dying Swan as well as Kirti’s fan variation from the Act III pas de deux in Marius Petipa’s and Alexander Gorsky’s Don Quixote. At the performance men are nowhere in evidence, either on stage or in the audience. The only males in the theatre are infants and toddlers and a handful of security guards who sit respectfully with their backs to the stage facing the perimeter walls of the theatre so that they do not break the modesty barrier by observing the religious girls and women dancing. All of the women dancers are dressed according to the laws of tznius, modesty in dress covering the parts of the body that should not be exposed following the stricture in Jewish Orthodoxy emphasizes the soul over the body as a statement of an individual’s essence.

There is an urgency and seriousness about how ballet is being wielded here. The audience is focused, expectant and saluting with applause and shouts achievements that go beyond the technical virtuosity of a balance on pointe being held or a leap sustained for several seconds in the air, the very fact of the performance itself happening seems to be the focus of its own celebration. As I will discover, this inaugural concert showcasing Orthodox women performing ballet presents ballet as a very serious medium for working through non-trivial issues between the secular body and the religiously observant one; between a self-authoring of female identity and stepping into an already very proscribed one. The women here are circumscribed by two orthodoxies: one is aesthetic the other religious. Ballet and the halakha, or “way” of observant Judaism: One, ballet, has an aesthetic code followed with the rigor of a devotional practice, the other, Jewish Orthodoxy, includes a set of bodily behaviors followed in obedience to devotional rules. Like the modified poster I initially observed advertising this event, the performance itself represents competing codes. The cultural and political implications of how these codes renegotiate identity between religion, art, feminism, and the body for the Orthodox Jewish woman is the subject of this exploration.1

I have chosen to revisit this performance now, 12 years later, because of the rich vantage point offered by the current global explosion happening in ballet as a newly politicized medium and to complicate many of the overly simplistic mainstream media and Netflix portraits now trending that are sensationalizing Orthodox lives as aberrant. I use new scholarship drawn from three disciplinary methodologies useful for thinking about embodied narratives. These include Dance Studies, Political and Conflict Studies and Religious Studies. My use of Dance Studies here is informed by close readings of embodied practices and performance with attention to Israeli dance scholars Dina Roginsky’s and Henia Rottenberg’s recent scholarship on dance relations, practices, and bodily capacities to represent conflict in Israel, as well as Hodel Ophir’s work on dance as symbolic physical expression for performing agency and nationalism among Palestinian girls in Israel (Roginsky and Rottenberg 2020). I read this through the feminist theory of Saba Mahmood, who in her analysis of Islamist cultural politics articulates the relationship between embodied religious rituals and the ethics and politics of female agency, an approach I argue that has applications for Jewish Orthodox women practicing ballet as well (Mahmood 2015, p. 21). Although Mahmood’s focus is the Islamic revivalist movement, her tracing of how secularism transforms the life of religious minorities and pious practitioners has relevance for Orthodox Jews in Israel. Mahmood argues that secularism does not just shape those who embrace it, but it also transforms those who resist it and that in trying to separate religion and the state, (as the Zionist founders of Israel did), the state ends up de facto involved in religious life through its policing of boundaries between the secular and practices of religious piety. “Secularism never escapes its own religious histories, nor does it ever achieve autonomy from the religious formations it aims to regulate”, she cautions (Mahmood 2015, p. 23).

Political theorist and ethicist Michael Walzer’s framework of The Paradox of Liberation, provides an additional important methodological frame for reading the role of ballet performed by Orthodox women by adding the context of religious fundamentalism. Here too secular formulations have an impact on Orthodox behaviors, in this instance the oppositional force of secular Zionism on which Israel was founded. In his reflection on religion and politics, Walzer identifies a pattern whereby successful secular national liberation movements are often challenged by religious revivals, and he sees the ideologies of the rising power of what he labels the “Ultra-Orthodox” in Israel as evidence of this. “[T]he shunned and silenced religious element in nation-states founded as secular–Israel is a paradigmatic case”, he writes, “…are rising up and marking their return in the form of “national & religious fundamentalism”. This fundamentalism and Ultra-Orthodoxy he argues, are both reactions to attempts at modernist transformation (Walzer 2015, p. 9). To a certain degree their success is carved out of secular Zionism’s failings.

Just as the secular Zionists of the first decades of Israel’s founding embraced folk dances like the Hora as part of the engineered identity of the muscular New Jew, a paradigm that is now fading, I believe this turn toward ballet by Orthodox women carries a political charge as a riposte against secular Zionism as an historic and now diminishing social construction. Effectively their embrace of ballet might be read as dance fundamentalism. Secular Zionism was deliberately written on the body and as Sociologist Dina Roginsky has researched, Israeli folk dances were hardly sui generis, they were based on adopted gestures and steps from a range of cultural sources, the Yemenite step the Circassian cross-step, the waltz step, Polka, etc. But the two that were the most fundamental for Israeli folk dance were “the Yemenite step and the Debka step”, specifically the Arab Debka (Roginsky 2020, p. 23). It was constructed through a nationalist imaginary consciously shaped to be the anthesis of the religious Jewish male body–the very body the Ultra-Orthodox in Israel have adopted. As Israeli gender scholar Yohai Hakak asserts, the early Zionist movement was influenced by other European nationalist movements that adopted and revived Hellenistic body culture as their mascot and part of their new robust nationalism.

What this meant was that the femininity of the traditional Jewish male body, a function of years of Yeshiva studies and exclusion from mainstream physical labor practices, was rejected with the establishment of the State of Israel in favor of the new attributes of the Zionist body. “The body of the new Jewish male was supposed to be tall, muscular through exercise and tanned from the physical labor under the hot sun”, Hakak writes. “The Jewish male was supposed to be assertive and self-confident–this is still a paradigm for most Jewish Israeli males, particularly in view of the centrality of military service in Israeli society” (Hakak 2009, p. 106). In contrast he argues, “Haredi rabbis saw the establishment of the State of Israel as a manifestation of this masculine anti-traditional assertiveness, some deeming it to be a great sin”. This new Zionist body was distressing Hakak argues, because by its very attributes it was refuting the image and values of the Ultra-Orthodox male body. Hakak asserts that with the establishment of the State of Israel the very institution that produced this body, Yeshiva studies, “became the only normative path for every Ultra-Orthodox young man” (Hakak 2009, p. 104). While Hakak’s research is focused on these tensions between the male Haredi and Zionist body, much of his argument also applies to the female Haredi body versus the female Zionist body. “Under the shelter of these total institutions was constructed an ideal male model with many of its attributes identified in western culture as feminine”. Hakak goes on to explain. “He is expected to be gentle in his body; his skin, pale from not being exposed to the sun due to his intense religious studies; his back hunched over from leaning over his books. He is expected to avoid violent confrontations with other men, to limit his sexuality to marital relations and subdue himself to the will of God” (Hakak 2009, p. 104). The Haredi women are surrounded by a similar set of concerns regulating their sexuality, comportment, what they can and cannot wear, how to groom themselves and encompass in their daily life their submission to the will of God.

The main attributes of the Haredi body that Hakak references repeatedly center around bodily and emotional discipline and self-regulation particularly in regard to sexuality. While his focus is the male, it is interesting that the majority of these qualities and behaviors also align with what the professional study of ballet requires. It is the subduing of the needy body into the strongly self-regulated one that allows a dancer to turn herself into an instrument of art in ballet. These include: the control of bodily needs, desires, urges, adherence to specific forms of dress and passivity/non-violence and gentleness in obedience to these strictures. Subduing oneself to the will of ballet then, has echoes of subduing oneself to the will of God. “Bodily restraint is perceived as a condition for the flourishing of spiritual life, an objective that can best be achieved through the study of the Torah and, mainly the Talmud”, Hakak writes of the Haredi male. He also notes a certain ambivalence in the Jewish attitude towards the body which on the one hand prohibits monasticism, unlike Christianity and other religions, but insists on discipling the body and training it in resisting earthliness by policing its carnality to render it spiritual. In an interview with Dr. Talia Perlstein, head of the Department of Dance at Orot Yisrael College in Elkana, Samaria, the leading Religious-Zionist college for religious women, she said succinctly when asked about the affinity of Orthodox women for ballet, “They like rules”. (Perlstein 2018, p. 3) Reflecting in another context more broadly about religious women’s embrace of dance in Israel she linked it with “… an expression of change and renewal taking place in religious society, one which is inseparable from the forging of a modern Jewish feminine identity.”(Israel National News (Arutz Sheva Staff 2017, p. 1)).

2. Dance Pedagogy and Ballet Fundamentalism

Initially I bracketed off this Jerusalem ballet performance as perhaps just an anomaly since, other than my colleague who had taken me to the studio where I saw the flyer, none of the secular Israelis I mentioned the performance to afterward had attended nor did they know much about it other than that it seemed to be the first of its kind. I learned that the organizer, adapter of the choreography and teacher of the dancers was Nadya Timofeyeva, the Russian-born and Bolshoi-trained ballerina and daughter of the famed 1960s Bolshoi star Nina Timofeyeva. Both women had emigrated to Israel in 1991 and began teaching at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance as part of the first wave of Jews arriving from the Former Soviet Union. Nadya reported that they were shocked at the lack of ballet training and ballet companies they found, “It was like another planet”, she said in an 2018 interview with me (Timofeyeva 2018). Eventually, in 2003 Nina retired from JAMD and she and her daughter opened a private ballet school in Jerusalem. They built a cluster of three studios in the windowless basement of the Teddy Stadium in Jerusalem. “They started arriving as soon as we began teaching”, Timofeyeva said, referring to the Orthodox religious children and particularly young women who came to the school wanting to study ballet. She was impressed by the young Orthodox women’s work ethic and enthusiastic embrace of the discipline of ballet. She estimated that within a few years up to 30% of her students were Orthodox. Eventually however, she found she had to restrict her classes for religious students to older girls because it was too difficult emotionally to have to exclude the religious children from the many class recitals and performances that are an integral part of ballet training. Religious prohibitions on even young girls performing before audiences where adult males were present made their participation impossible. It was out of admiration for the work ethic of the religious women, and for the older ones in their persistence in dancing while pregnant, that led to her personally subsidizing that first religious women dancing concert in 2010 and to edit the classic ballet repertoire to avoid tutus and partnering while deliberately choosing a works that were modest and did not have flirtation or seduction. “I was the only one I know of who made a performance to show that religious women do have the power to build a company”, Timofeyeva explained. (Timofeyeva 2018) While she has never staged another concert of religious women dancing again, her efforts have been an inspiration for several of her religious students who have since pursued teaching and staged showings of their own students’ dancing.

Over the next decade I interviewed Nadya multiple times, observed her classes and rehearsals and also spoke with several of her dancers. In 2012 I spoke with Rachel Abrams, who was one of the leading dancers in the 2010 concert and the Israeli-born daughter of two American parents. “Growing up I felt very frustrated that I couldn’t perform”, Abrams said speaking from Brooklyn, noting the impossibility for Orthodox girls and women to perform before audiences with men in them. Abrams added, “I wasn’t aware I was talented. But I saw other girls working hard to get into schools and companies and I wanted to get on a high level. But I knew it was impossible for me to be in a professional company because I was Haredi, and I can’t perform with guys or study with male teachers or do any partnering”. Abrams was 27 years old when we spoke and she was in Brooklyn because family felt that her pursuit of ballet had delayed her finding a match and getting married long enough and past the point most young Haredi women have already become mothers. “We are very pure in the ballets we do”, Abrams says of her own performing of classical ballet and also that of the students in the ballet classes she used to teach on her own for Haredi women. “I think the religious community is very interested in ballet because it is conservative”, she says. “I find that because it is more conservative it’s more connected to the Haredi world. It’s gentler and people know it’s very noble and beautiful”, Abrams said. “The contemporary dance would not be suitable”.

Several women told me that in some Orthodox communities being a young woman who was involved in dance carried its own liability of deeming one less desirable as a potential bride because it hinted at someone who pushed boundaries. While hyper-sexualized forms of vernacular dance are not acceptable at all, ballet carries a different set of associations as being modest and graceful. Still some unmarried women found it a better strategy to kept secret the fact that they studied ballet. Not all the encounters between Orthodox women and ballet have been happy ones. A few of the women I interviewed told me about having to hide their slipping away to dance studios when they were young and being punished and forbidden from pursuing dance when their parents found out. In narratives that echo the story of Giselle and the perilous pull of dance for young women, some of these encounters resulted in sanctions by their Orthodox family and communities for involvement with dance and that the elevated body carriage and sense of pride about their transforming bodies was construed by some outside of ballet as arrogance and a misplaced emphasis on looks rather than inner qualities. Daniella Bloch, who was a professional level ballet and contemporary dancer in the U.S. before emigrating to Israel and was the artistic director of Nehara, the leading contemporary dance company of all Orthodox women. In 2017 Bloch closed her company in order to focus on training the next generation of professional level dancers at Givat Washington, a new high school conservatory for Orthodox girls where her rigorous ballet classes are a core part of this training. She speaks of the challenges of teaching Orthodox girls in not just technique but the essential presentation of self that is part of professional level ballet: “There is a DNA in Orthodox women from their education of modesty so that they don’t have a sense of being in the world with assurance- a “this is me” presence Bloch lamented as she stood in the regal, head high and shoulders back strong yet modest carriage of a ballerina (Daniella 2018).

“I am starting from Zero, I teach ballet twice a week”, she says before teaching a beautifully paced and high-level ballet technique class for seven 9th and 10th grade girls.

“But they are so inhibited in their bodies, inhibited within the body, it is from the DNA of being Orthodox, to be inhibited in the body”, Daniella explains adding that it may take a generation to realize her dream of building a strong base of Orthodox ballet dancers. “I am working so hard to do things like teach them to attack! When they stretch their leg out (as she gestures shooting her arm stiffly forward as if it were a foot in a pointe shoe). It is so hard”. Her tone in the classroom has the demanding strictness of a professional New York ballet studio, the kind Daniella grew up in and her students wear the pink tights and black leotards of a ballet conservatory with some of the women adding long skirts for modesty. They are all slender and eager and despite starting comparatively late to learn ballet, they know the positions and steps as she calls out the terms in French. Bloch offers frequent corrections, wanting a very tight fifth position here, the preparation for a pirouette turn is broken down in detail that is very clear and systematic. Her vision for high level ballet performed by religious girls is clear and in process.

3. Ballet’s Complex History in Israel

As I pursued my research, I was also conscious of earlier histories of dance and politics in Israel and how folk dance had aligned with Zionism and the secular Jewish identity of the Jewish state from its initial days. Historically, ballet has been seen as outside these cultural conversations in which a Jewish Israeli national memory and future have been charted. In 1949 Shulamit Roth, a dancer trained in the contemporary mode of Ausdrucktanz, (1930s German Expressionist dance) editorialized in the leading Hebrew daily, Haaretz, against fledgling attempts to seed ballet in the new nation. In May 1939, (a prophetic moment given what was happening with Nazi aggression in Europe), a decade earlier, she warned of the dangers of German physical culture training in a lecture she presented to a meeting of physical education teachers. She cautioned them against using this German system of training because: “[i]t creates citizens who are neither independent nor free. It creates an inflexible body which is a machine–whose muscle bulk is substantial–but it has been subverted and devoid of pleasure. A body which has been separated from its soul cannot be made healthy”, she concluded drawing a direct line between extremely disciplined movement training and morality. (Roth 1939) A decade later ballet would be in her sightlines for its unsuitability because of its elitist historic legacies. Ballet, unlike German physical culture training, built bodies that had an aesthetic and moral grace, so instead it was its classed nature Roth targeted.

The following is from Roth’s 1949 Haaretz editorial:

“The tradition of the ballet is something strange to the Jew, and strange to the Jewish artist. This is the tradition of the courts of the princes from the 18th–19th centuries. This is the style of etiquette in the courts of kings in the Rococo period. This has been preserved as a wall and shield from the voices of a new time and its demands. These demands are the social and personal freeing of the individual. It’s interesting that although there is a big contrast between the new Russian people and the style of the court ballet–the ballet has been preserved in Russia”. Haaretz(Roth 1949, June 17)

As Roth’s editorial attests, the place of ballet in Israel was contested from the beginning, and unlike expressive dance, it would take decades to begin to overcome these reservations–something that is still in process. Everything about ballet, from its hierarchical body posture and social order, historical lineage and use of stage space as a mirror of courtly deportment appeared counter to early Zionist tenants. Roth was giving voice to a growing desire that the new nation needed a representative dance form free from all European influences and associations. She was writing with a consciousness of how in Israel dance was being recruited to be part of the machinery scripting the ideal citizen. Since the 1930s, more than a decade before the founding of Israel, resident physical education teachers like Roth had judged dance in Palestine for its service to Zionist political and social goals. Ballet had too many negative associations as an elitist European cultural practice.

Like a Fly Trying to Push against the Enormous Elephant of Modern Dance

Part of the reason the ballet performance I witnessed had been so unexpected was that Israel had been inhospitable to ballet practically and politically since the arrival of the first Russian ballet dancer, Rina Nikova, in the 1920s. As Professor Sari Elron has shown in her important research on Nikova, this Russian-born dancer who trained at the conservatory in St. Petersburg with Nikolay Legat, initially visited Palestine in 1924 as a tourist with her father. When he returned to Russia, she remained. “I made up my mind to develop ballet there against the exotic, captivating background that the country then seemed to me”, Nikova said (Ronen 1990). Performing on makeshift stages of tables covered with blankets, she soon found replicating the ballet of Russia was impossible. Her compromise was to create what she called her “Biblical Ballet” group in 1933, a group of young Yemenite women who presented songs and dances from Yemenite folklore restaged in a theatrical setting. Although Nikova used ballet in training her dancers, they never performed ballet.

Mia Arbatova, a ballet dancer from Riga, followed Nikova. Arbatova came to Israel in 1934 on a dance tour with her husband and returned four years later to seed ballet. This task she once said was “like a fly trying to push against the enormous elephant of modern dance” (Ingber 1975, p. 12). “Ballet was certainly not loved here–it was very, very low down on the list of dance entertainment”, she said. “While I tried to propagandize for ballet, I knew people who looked on ballet as a kind of horrible four-legged creature… Not one book on ballet was to be found in Israel, no films, no guest dancers. There was nothing to help me support my work to develop the art of ballet” (Ingber 1975, p. 12). Instead Arbatova became a teacher. Not until the first decade of the 21st century, however, did it become possible to read a strong alternative narrative through dance–one in which the practice of classical ballet in Israel can be seen as a resistive cultural text confronting the gender coding of the Jewish state as masculine and aggressively athletic. In this context, it is possible to being to see why that 2010 performance I witnessed was so groundbreaking.2

4. Studying Israeli Orthodox Women: My Positionality

While my position as a secular Jewish woman and Dance Studies scholar helped some to mitigate my status as an outsider doing research about Orthodox women doing ballet, as an American I was very conscious of not wanting to be judgmental or essentializing about Israeli Orthodox communities.3 I was respectful of attiring myself modestly, conscious of what parts of my body needed to be covered and wearing dark conservative dresses rather than pants. I found that this helped facilitate my interviewing and class observation opportunities. I also found myself needing to think about what to do with my feminist point of view in regard to the halakha rules governing modesty of a woman’s body–some might view these reflexively as a shaming of a woman’s body, since one interpretation is that men cannot control their sexual urges and the onus is on the woman to not incite or arouse. I wanted to work from within a respect for Haredi culture and religious practice and to be sensitive to their complexity.

What would it mean to see ballet not as an example of female docility and obedient physicality but as an opportunity to rethink both how religious practice shapes the female body and the standard assumptions about ballet as a complex body technology differently? Over the past several years these questions have propelled my research into classes and performances globally from Orthodox communities in Jerusalem, the settlements, in the U.K. in Stamford Hill and Golders Green, in the U.S. in Williamsburg, Crown Heights, Monsey, Teaneck, Maryland and Los Angeles. I have interviewed dozens of dancers, students, teachers, parents and Rabbis. I have found the circulation of baal teshuva American women with early experience in ballet, often in the secular world initially, has been instrumental to seeding ballet in Ultra-Orthodox communities in Israel.

Ballet can often be framed as colonialist and a reinforcement of gender, class, and social hierarchies, but I explore this intersection of ballet and Orthodoxy from a more open perspective: What motivates these Orthodox women to take up ballet? What are their stories, how can I tell their multiple narratives? My goal is to come from a place of love and curiosity rather than judgement. My focus has been on making my questions about curiosity–every religion has paradoxes and for me the challenge is how to talk about ballet in the Orthodox communities in a way that will enable me to discover as much as possible about it. As a dance historian doing a close reading of specific dances, choreographers, teachers, the task of contextualizing them is a reflexively familiar way to proceed–but here my object of study and inquiry is something much more elusive. It is the interior experience of meaning and the forces that inform a decision to turn to ballet as a cultural practice and then what unfolds within that are part of what interests me. What Judith Hamera in Dancing Communities in another context has called dance as “vital urban infrastructure:” the way that study in dance produces generative and unexpected alliances across multiple dimensions of difference” (Hamera 2007, p. xi). So how to study these dimensions?

5. The Global “Opening” of Ballet

Even as an outsider in the Orthodox communities in Israel I recognized that what was happening in the “Religious Girls Dancing” concert was something radical for ballet.

Now a decade later it is possible to understand this performance more clearly as a forerunner of a massive shift underway in the artform: a rapidly expanding global trend that sees ballet being repurposed as an important medium for radically renegotiating identities. Ballet dancers drag a long and conservative history with them each time they step onstage. Yet, recently some of the most radical challenges in dance are coming from disabled ballerinas pirouetting in wheelchairs, male dancers in tutus and pointe shoes, non-binary, and Asian and Black dancers offering important alternatives to the white heteronormative model of traditional ballet. The movement that began more than a decade ago in Israel of Orthodox women studying and performing ballet viewed retrospectively from 2022 can now be seen as a vanguard action, a forerunner of these current global repositionings of ballet as a daring future-facing art form. More than any other dance genre it has become one where the politics of nationality, religion, class, gender, race, and ableism are publicly scrutinized. These issues are being provocatively illuminated by classically trained dancers like South African artist Dada Masilo who inverts the presumed whiteness and heterosexuality of ballet in her gender-bending Swan Lake and Giselle mashups and also by Black British activist dancer Alice Sheppard whose aerial performances from her wheelchair showcase the beauty of differently abled bodies dancing. So, it is within the context of these explosions of the category of ballet that this article situates the cultural, political, and religious implications of Orthodox women studying ballet.

6. Israeli Orthodox Ballet: Liberatory While Pious

The gender architects behind this development in Israel are a group of pioneering Israeli women including: Nadya Timofeyeva, Talia Perlstein, Daniella Bloch, Irena Markish, Shoshanna Brody and Rachel Abrams, among others who were, and in many instances still are, reshaping the study of ballet into a liberatory yet still pious practice for Orthodox women. They belong to this growing international community of ballet teachers and choreographers who are recasting ballet as a site from which to address pressing social issues of equity, inclusion, piety and self-authorship from the position of an art form that for centuries has been considered an exemplar of the static, imperialist, idealized, heteronormative, white, Christian body.

In looking at the impact of the work these women have been doing with ballet in religious communities in Israel I identify four significant ways in which Orthodox women doing ballet is functioning as counterrevolutionary and presenting challenges to both Jewish Orthodoxy and Israeli Zionism. First, these women are reclaiming the body and finding ways to open it to aesthetic pleasures and expression while still being respectful of Halakha. Additionally, they are aligning with the religious community in Israel by negotiating a qualified resistance and acceptance of Zionism but doing it through a radically alternative dance form and one that imparts to them, in a stealth mode, body liberation. They are also taking a dance form usually dismissed as being about subjugation of women and making it a means to liberation as they resist the more rigid rules of their own ultra-orthodox society. Finally, the female Orthodox dancers are broadening the category of what a ballet body is, it can be pregnant, nursing, postpartum, and while it is still serving reproductive mandates it is also a medium for art. As with the clothing modifications on the Romantic Era lithograph, these women are signaling how they can go out in the world, tread between two social orders, and not lose who they are. In short, they are negotiating a hybrid, hyphenated, and expanded identity through ballet. In a curious parallel, secular Israeli women who want to be ballet dancers also have to content with their own hybridity–the two to three years of obligatory military service required of every Israeli man and woman over the age of 18–the prime years of training and performing in a dancer’s life.4

6.1. Reclaiming the Body and Finding Ways to Open It to Aesthetic Pleasures and Expression While Still Being Respectful of Halakha

Orthodox women doing ballet are taking back the body, reclaiming a place for the feminized religious body through dance. The result is a physical presence that is gendered without being sexualized. Regulated, yet also proudly physical, visible and with agency. Through ballet these women are charting a middle course tzniut (a conduct of modesty and discretion) but with the lifted body carriage, shoulders back, head held high and long neck of the vertical alignment that ballet privileges. Irena Markish, the Russian trained ballet teacher at Orot College, was one of several ballet teachers of Orthodox women who mentioned the challenge of opening their young students’ hunched body posture by having them lift their shoulders and raise their heads, instead of the forward rounded position young girls shy about their developing breasts often assume. “God gave you this”, Markish says”, don’t be ashamed, stand proudly”. (Markish 2018, p. 4) It’s an injunction about art but also about life and one that uses ballet to shift from a more fear-based approach to the body’s sexual dimensions to one of self-ownership and pride without vulgarity or immodesty.

One facet of reclaiming the body Markish notes is the new attention to developing and training one’s muscles and through corrections by touching that is instructive not sexual. This is the norm in dance but an anomaly for many in the religious community. “Of course, the first lesson, I explain to them that there’s a lot of teaching. I mean, I’m touching, and explaining to them”, Markish said. “And of course, it’s very important for me to know if someone doesn’t want me to touch her, you know, to correct her with my hands. She only has to tell me and of course I will respect it”. She continued, “For me it’s very important to explain to them, to teach them, to show them which muscle they have to use because they don’t know anything about their bodies”. In the dance studio Markish frequently draws a line from lessons in the study of ballet to lessons for life: “When I’m teaching [in Orot], the first thing I say is: “Control your body; You control your life. Control your muscles, you know how to control your way in your life. I also say to them, ‘If you want to be strong, you need a strong back.’ And all of them love it, she says.

Deborah Feldman, the author of Unorthodox, the book and Netflix series about her escape from her Orthodox community, calls the Orthodoxy she grew up in in the Satmar community, “fear driven”, particularly its heightened anxiety around the female body and women’s sexuality. “You grow up and you learn that the body is disgusting and that you are disgusting because you are somehow connected to your body”, she asserts. “But yet you have to use your body to service the community, so you are always living in this contradictory state that your body is terrible, but your body is important”. Reducing this fear around the body is an important part of the early negotiation in ballet training for religious girls. Markish recounted how she was cautioned by the director when she began teaching at Orot college to carefully vet any videos of professional dance performances because the women students could not look at a man in tights. She also had to negotiate with women would not wear pants without a layer of skirts over them, covering that masked the body so completely that Markish could not see their legs to correct them.

6.2. They Are Aligning with the Religious Community in Israel by Responding to through a Form That Is Radical Yet One That Imparts, in a Stealth Mode, Body Liberation

The phenomenon of Orthodox women performing ballet thus has the potential to be a serious medium for working through tensions between secularity and religious orthodoxy, agency and embodiment. I am taking care not to essentialize the Orthodox body and to recognize that there are differences in the religious subgroups that comprise this society. Paradox and tension are at the core of curiosity about Orthodox women doing ballet: the pious chaste body intersecting with dance, an art form premised on displaying the female body. Hodel Ophir noted a similar paradox around issues of power and agency in dance training for Palestinian girls and women circumscribed by gender restrictions in their religious community. As she notes: “But in dance there exists a paradox in which oppression restriction and limitation are presented in a body that demonstrates the exact opposite: high levels of aptitude freedom and power” (Ophir 2020, p. 64).

What makes the phenomenon of Orthodox women studying ballet in Israel so fascinating is that it is neither exclusively an action of resistance to Zionism nor of placid compliance with Jewish Orthodoxy. Orthodox women doing ballet in Israel might be considered its own counterrevolution-a religious one. Following Walzer, I define counterrevolution in the 21st century as “the rise of the shunned and silenced religious element in nation-states that were founded as secular”. On a purely physical level the aesthetic attributes of ballet are diametrically opposed to both the communal folk dancing initially associated with the early Zionist project in Israel and, more recently, also with the aggressive and wildly dis-regulated body of Ohad Naharin’s Gaga aesthetic which globally has replaced the Hora as the dance form most emblematic of Israeli dance. Instead of the grounded, weighted, anyone-can-join-in ethos of folk dance and the sexualized, aggressively athletic body of Israeli contemporary dance, ballet takes years of study to quiet and shape the body into a gravity resisting figure performing roles that are highly gendered and many of whose narratives are de facto primers in the social hierarchy of European elites. Even with the elimination of male partners the choreography, gestures and manner of women doing ballet can still carry these references.

Just as the secular Zionists of the first decades of Israel’s founding embraced folk dances as part of the engineered identity of the new Muscular Judaism, this turn toward ballet by Orthodox women also carries a political charge. The practice of ballet by Orthodox women and girls is by necessity a sequestered phenomenon. For many in the secular world, the lives of Orthodox Jews generally remain closed and protected and their engagement with the arts hidden. Recently Netflix series like Unorthodox and Shtisel tease with theatricalized glimpses inside the Haredi Communities in Israel. These series cultivate the public’s voyeuristic gaze by presenting the social structures of Orthodox communities as stifling to individual agency and women’s freedom with their own bodies. In both of these series art becomes a conduit for escape–literal in the former and metaphorical in the latter. Singing for Esther Shapiro, the heroine of Unorthodox, and painting for Akiva Shtisel the contemplative male protagonist of Shtisel, are proxies-symbolic arenas in which resistance is registered as the maverick authoring of an individual voice and viewpoint. Instead, in my reading of the politics of Orthodox women doing ballet I find the nuanced framing of Orit Avishai’s theorization of how religious affiliation empowers women opens an understanding of the doing of ballet within religious rules of modesty as an act of compliance and agency. Avishai (2008, p. 411) Avishai asserts that “Agency is located in the strategic use and navigation of religious traditions and practices to meet the demands of contemporary life”. By associating agency with observance, the “doing religion” approach Avishai formulates avoids the false dichotomy that pits compliance against agency. (p. 429)

6.3. The Tensions That Orthodox Women Doing Ballet Illustrate Are Varied and Instructive

These religious ballet dancers are broadening the category of what a ballet body is, it can be pregnant, nursing, postpartum or anywhere along this continuum and yet it is still serving art as well as reproductive mandates. As with the clothing modifications to the Romantic Era lithograph from that inaugural concert, religious girls and women doing ballet are signaling how they can go out into the world and not lose who they are in their faith. Dancers are “doing religion” while negotiating a hybrid, hyphenated, or expanded identity through studying ballet. Markish, coming from the context of traditional Russian ballet, expressed her surprise at the women’s determination to continue dancing through pregnancies and motherhood: “They enjoy the experience. They wanted to be there so much. They really dance, not for the sake of the audience: for me, performance is to perform for the audience. But they were always there for the sake of dance. And it amazed me, because I remember the first year one of the girls I was teaching there, she was dancing on the stage the first year. She was 9 months pregnant. And I never saw a pregnant dancer. And you know, definitely not in the classical ballet. She was jumping, and she was rolling around. And I was looking, and wondered: “What would happen if she had it now?” Markish marveled. (Markish 2018. Tel Aviv, Israel) Instead of the eternally pre-pubescent body of ballet Orthodox women performing are meeting the even more difficult challenge of repeatedly finding and losing their dancing form and technical strength as frequent pregnancies and children keep pulling them away and yet they keep coming back, stretching the boundaries of who can dance and when.

Although Nadya never produced another concert of “Religious Girls Dancing” she did not stop offering ballet to Orthodox women. Beginning several years ago, a new demographic of women in Jerusalem approached her about creating a ballet class for them. They are older Orthodox women ranging in age from their late 50s to 70s with a few younger mothers in their late 20s and 30s also joining in. LM is a 59-year-old mother of 11 children who discovered ballet as a mature woman. “My friends think I am crazy”, she says. “It’s very special to be able to still dance”, she says. “I am very grateful. I am an architect with a large family, and this is the highlight of my week, coming to these classes”, she confides. “Ten years ago, I started coming. It’s a special atmosphere here. It’s like when women dance at a wedding. It doesn’t feel like a ballet school it has special energy here”. LM said she feels free in the ballet class. I watch as she stands at the margins of the room, removes her sheitel (her wig to signal that she is married and observes Orthodox rules of modesty) and knots a scarf around her head before she steps to the barre for the start of class. SM, another mother, parks her sleeping 6-month-old baby girl at the side of the studio in a stroller while she takes class. The feeling in the room is one of an intimate female space, a bit transgressive perhaps in the way the women relax into their bodies and also take pleasure in the beauty and physical accomplishments of one another, but at the same time it is marked by a quiet dignity and respectfulness very different from the typical raucous commercial ballet school. As the class progresses it is amusing to watch how the women keep coaxing Nadya to demonstrate more and more fully the phrase she is teaching. When she finally does, they can gaze admiringly at her lean, muscled ballerina’s body in tight black jeans and red short sleeved tank top and with high arched black sneakers as she sails into the air and lands with a silent clean finish, her feet in a tight fifth position her lithe form lifted and elegant. A small round of applause breaks out. Dance Studies scholar Judith Hamera has observed how in dance “Technique constructs intimate, familiar places for a politics of self and community…” a politics that “discloses way of escaping from and relocating to different subject positions…” (Hamera 2007, p. 61). With their own bodies, and in the joy they take in being spectators of Nadya performing so fully the very phrase they are struggling to master, the Orthodox women here are participating in what Hamera identifies as one of the gifts of ballet training, its capacity to invite “a complex geography of fantasies: dreams of physical and social virtuosity shot through with longing that both masters and exceeds technique” (p. 69).

7. Conclusions

Mixed in with these pleasures and fantasies, technique class in ballet is a catechism of dozens of repetitions of positions, movement phrases, anglings of torsos, articulation of feet. Similarly, the repetitive daily actions of Orthodox observance, prayer, the covering of the body to honor modesty, the subtle, composed presentation of self as an inward rather than outward expression, imprint the body. Ballet as a highly disciplined and codified dance genre resonates well with rule-based religious observance, as several dance teachers noted. Orthodox Judaism and traditional ballet uphold gender binaries shaping & regulating the performance of identities. There is predictability and the containment of boundaries in both–Ballet with its pink pointe shoes and hyperfeminized images of female dancers has been used for decades globally as a means to instill the performance of modest and chaste femininity in girls and this too aligns with Orthodox values.

Feminist and queer assessments of religion and sexuality often assume that regulation and affirmation of sexuality are incompatible. Ballet in Orthodox communities offers another viewpoint. In place of a presumed incompatibility of the carnal and the pious can Orthodox women’s practice of ballet lead us into a more generous alternative perspective? Can ballet offer Orthodox women a site where sexuality, physical liveness and desire do not necessarily have to be unhinged to be sanctified? It is fascinating that the religious community of women has found a connection to the body in an art form in which so many others have found estrangement. Does ballet as a dance genre have deep codes for regulating sexuality by implicitly seeming to showcase it? Might it be the antithesis of female sexuality in fundamentalist religious models where surface modesty mutes, but also simultaneously heightens curiosity about the female body by naming it as a danger that needs to be controlled? In contrast, the woman in ballet teases with an illusory availability, yet she is shielded by layers of aesthetic protocols governing the representation of desire, gender, intimacy, and sex.5 Thinking more deeply about how ballet works in this regard, as a physical art practice built on a sophisticated system of gender containment deemed compatible with Jewish religious orthodoxy, may in turn invite discoveries about ballet itself. Jews have been defined either as a diaspora, a condition said to be inimical to originality or distinctiveness, or as a nation without art, that is until Zionism prompted a self-conscious effort to create it. Might it in fact be because of Zionism and the establishment of the state of Israel that the religious can now embrace ballet and by extension make art? The labor of pioneering a self-conscious creation of Jewish art was begun by Zionism and religious orthodoxy is following in the wake with ballet as one of the art forms being explored.

As Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jonathan Karp have noted “While Jews are not the only diaspora, they are the paradigmatic one, such that the Jewish art question becomes a prime site for exploring what a diasporic aesthetic might be…” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Karp 2005, p. 6). Looked at within this frame Orthodox women doing ballet are new models of juggling multiple affiliations and subjectivities, uncertainties, and ambivalences. These are prime aspects of diasporic art making. They possess what WEB DuBois referring to the African American experience, designated a “double consciousness”. Local, and translocal, these dancing girls and women are similarly connected to two vast imagined communities: Orthodox Judaism and ballet. The body they are negotiating in the spaces between may well change the contours of both worlds.

Author’s note: I would like to extend a special thank you to the Fulbirght Scholars Program for my 2010 award that made possible my initial research in Israel, the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance for hosting me and Dr. Vered Aviv and Dr. Dana Bar for their warm collegial support during my stay. I also extend special thanks to Nadya Timofeyeva and her students for inviting me into their classes and rehearsals and to the many religious women and girls who welcomed my questions. Jennifer Homans and the staff of the NYU Center for Ballet and the Arts deserve exceptional thanks for an Autumn fellowship that allowed me to deepen and develop this material in an invigorating scholarly community.

Funding

This research was funded by The Fulbright Scholars Program and the Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Throughout this essay I strive to avoid essentializing or stereotyping concepts of secular Zionism and Israeli orthodoxy and ultra-orthodoxy, recognizing that they are extremely fluid concepts. I thank an anonymous reader for highlighting this. |

| 2 | It is important to note the vital and pioneering work done by the French born Israeli dancer and founder with her husband, Hillel Markman of The Israeli Ballet in 1967. Although their repertoire and dancers were essentially secular they certainly had some cultural impact before the arrival of the ex-Soviet ballet teachers in the 1990′s. |

| 3 | The word “haredi” is a catchall term, either an adjective or a noun, which covers a broad array of theologically, politically, and socially conservative Orthodox Jews, sometimes referred to as “Ultra-Orthodox”. What unites haredim is their absolute reverence for Torah, including both the Written and Oral Law, as the central and determining factor in all aspects of life. Consequently, respect and status are often accorded in proportion to the greatness of one’s Torah scholarship, and leadership is linked to learnedness (Ingber 2011a, 2011b). |

| 4 | Although professional level athletes, dancers and musicians can request special accommodation to continue their training part time while fulfilling their military obligation, this is not the same as the exclusive fulltime conservatory preparation dancers without military obligations enjoy. |

| 5 | “To walk and wear your body with pride is not a customary thing (in Orthodoxy)” one woman told me. |

References

- Arutz Sheva Staff. 2017. Orot College: Pioneers in Opening Dance Dept. in a Religious College, First to Receive Coveted Prize. Israel National News, December 10. [Google Scholar]

- Avishai, Orit. 2008. Doing Religion in a Secular World: Women in Conservative Religions and the Question of Agency. Gender and Society 22: 409–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniella, Bloch. 2018. Interviewed by Janice Ross. Jerusalem, Israel. October 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hakak, Yohai. 2009. Haredi Male Bodies in the Public Sphere: Negotiating with the Religious Text and Secular Israeli Men. Journal of Men, Masculinities and Spirituality 3: 100–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hamera, Judith. 2007. Dancing Communities: Performance, Difference and Connection in the Global City. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ingber, J. Brin. 1975. Ballet Finally Moves Front. Detroit: Israel Dance. [Google Scholar]

- Ingber, Judith Brin. 2011a. Vilified or Glorified? Nazi versus Zionist Views of the Jewish Body. In Seeing Israeli and Jewish Dance. Edited by Ingber J. Brin. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, pp. 251–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ingber, J. Brin. 2011b. Seeing Israeli and Jewish Dance. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara, and Jonathan Karp. 2005. The Art of Being Jewish in Modern Times. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Saba. 2015. Religious Difference in a Secular Age: A Minority Report. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Markish, Irina. 2018. Interview with Janice Ross. Tel Aviv, Israel. October 20. [Google Scholar]

- Ophir, Hodel. 2020. Performing Nationalism. In Moving Through Conflict: Dance and Politics in Israel. Edited by Dina Roginsky and Henia Rotttenberg. London: Routledge, pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Perlstein, Talia. 2018. Interview with Janice Ross. Tempe, Arizona. October 14. [Google Scholar]

- Roginsky, Dina. 2020. About Arabs, Jews and dances, Dance relations in Palestine and in the state of Israel. In Moving Through Conflict: Dance and Politics in Israel. Edited by Dina Roginsky and Henia Rottenberg. London: Routledge, pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roginsky, Dina, and Henia Rottenberg. 2020. Moving Through Conflict: Dance and Politics in Israel. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ronen, Dina. 1990. Rina Nikova: Jewish Women’s Archive: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia. Available online: http://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/nikova-rina (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Roth, Shulamit. 1939. Haaretz. Tel Aviv, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Shulamit. 1949. Haaretz. Tel Aviv, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Timofeyeva, Nadya. 2018. Interview with Janice Ross. Jerusalem, Israel. October 20. [Google Scholar]

- Walzer, Michael. 2015. The Paradox of National Liberation: Secular Revolutions and Religious Counterrevolutions. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).