What chaos and rhythm have in common is the in-between-between two milieus, rhythm-chaos or the chaosmos: Between night and day, between that which is constructed and that which grows naturally, between mutations from the inorganic to the organic, from plant to animal, from animal to humankind, yet without this series constituting a progression. In this in-between, chaos becomes rhythm, not inexorably, but it has a chance to. Chaos is not the opposite of rhythm, but the milieu of all milieus

He was feeling his way through obscurities.

—Aldous Huxley, Mortal Coils

1. Introduction

Minóy was the pseudonym of the electronic art musician and sound artist Stanley Keith Bowsza (30 October 1951–19 March 2010). He created some of the most remarkably engrossing, harshly beautiful, and imaginative art music albums released on cassette in the 1980s―that he mailed out from his home in Torrance, California. Though perhaps understandably unknown (he and his noisescapes were celebrated only once in the media, in 1991, when his image appeared on the cover of the July 1991 issue of Electronic Cottage magazine) Minóy was a major figure in the DIY controlled noise music and homemade independent cassette culture scene of the 1980s. His work provides an antithesis to the authoritarian, perfunctory, simulated rigidities of the controlling technical-mechanical world.

It is significant that Bowsza chose his pseudonym Minóy based upon how someone he met mispronounced the name of one of his favorite artists, the deceased Catalan Surrealist Joan Miró. One can detect with this choice early on his embrace of psychic chance operations coupled to the machinic-phantasmagorical: a method-theme that is profoundly explored during his creative career.

Minóy was agoraphobic, but a prolific sound artist intensely active in the music underground between the years 1986 and 1992. During that period he created many mesmerizing audio agglomerations in collaboration with other sound artists and mail artists. To be sure, Minóy was an avid mail collaborator, working with noted experimental American composers such as PBK (Phillip B. Klingler) (as Minóy and PBK but also as Disco Splendor), If, Bwana (as Bwannoy), Agog (as No Mail On Sundays), Zan Hoffman (as Minóy\Zannóy), Dave Prescott (as PM), Not 1/2 (as El Angel Exterminador), and many others. But he is best known for his thick palimpsest-like multi-tracked soundscape solo compositions: machinic-like flamboyant productions that follow the incorporation of multilayered electric sound into music compositional practice similar, at times, to the masterful musique concrète coming out of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales.

2. Minóy: The Desiring-Machine

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, in their book Anti-Oedipus (

Deleuze and Guattari 1984) point us towards the machinic nature of desire. They define desiring-machines as those which function as circuit breakers in a larger circuit of various other machines to which they are connected.

Minóy’s noise music is a form of desiring-machine. It is a labyrinthian droning superimposed collage electronics that produces a machine-like intensity. It is sound art that is highly textured, manipulated, and layered―often creating a sonic painting-like effect with a spatial feel. Frequently, nonperiodic tone clusters sweep across the treble range, moving the contours of the sound, like shifting waves of shimmering colors that glide in an ocean of found sound. Many of his tape releases had only one or two compositions on them, thus allowing him the time to develop a machinic drone theme and hypnotically immerse the listener in what were usually vastly complex long works of audio art.

His challenging, perhaps irritating at times, roaring recordings―such as in Corridors (1985)―were often created by delay echoing and multi-tracking sounds (like field recordings and short-wave transmissions), resulting in rather deep and ambiguous compositions full of feeling. Sometimes, as in Shame On Love (1986), he used a constant murmuring voice along with found sounds or static or shrieks or staccato guitar bursts or the twitter of a toy mouth organ. His commanding but graceful compositions were more often than not delicate yet powerfully embellished soundscapes of sophistication. The work’s transformative affect is typically achieved through an effective cumulative buildup of tense, almost nervous, sounds that cycle through the realm of overload: an overload that compresses and mutates the original sound sources and transforms them into an expanding and indeterminate sonic field. It is a technique of creative destruction highly suggestive of desiring-machines and other forms of cultural social resistance applicable to global technoculture, as it suggests an ultimate triumph of individual originality over machine hegemony.

Minóy first came into my realm of awareness in the snail mail. I never met the man. Out of the blue in 1986 I received in my Lower East Side mailbox a tape from him that I loved immediately: In Search of Tarkovsky (1986). I quickly began trading Tellus Audio Cassette Magazine tapes with him for his work; my favorites being

Doctor In A Dark Room (1985), Nightslaves (1986) and Firebird (1987). These tapes resonated considerably with the overloaded nature of the palimpsest-like gray graphite drawings I was working on then (which were reflective of the time’s concerns around multiple forms of proliferation), but my reception of his music also had to do with my vague impressions of California. No, there was no sun in them, but I could vaguely detect the vastness of the Pacific Ocean, long lazy LSD trips, morning bong hits, and lurking danger. So, I was deeply impressed by his talent, and I was determined to publish something by him on Tellus as soon as I could, for his work reminded me of when I first saw the obscure No Wave performer Boris Policeband play in 1978 at a concert to benefit Colab’s X Magazine. It was entrancing for me how Policeband appropriated police scanner radio transmissions and entwined them with his dissonant violin. But Minóy’s brand of post-minimalist noise music even better echoed my own form of post-minimal chaos art/magic with its emphasis on art-of-noise magical gazing.

1In 1978 I had been reading Aleister Crowley’s book Magick in Theory and Practice (

Crowley 1976). What I conjectured from Crowley―while listening and watching Boris Policeband―was that a noisy aesthetic visualization process could be used to create feedback optic stimulus to the neocortex in a kind of cop free foreseeing, based roughly on the basis of tribal magical gazing. That gazing led me to imagine the Tellus Audio Cassette Magazine and hence become acquainted with the noise music of Minóy. So, I was very pleased to have published Minóy’s dark ambient composition Tango (1985) in 1988 as the lead piece on Side B of Tellus #20, an issue I curated entitled Media Myth. (

Nechvatal 1988).

The question I posed for Media Myth was: how can artists, like Minóy and myself, symbolically turn power codes into artistic abstractions of social merit? Perhaps it was possible because he knew (as demonstrated with his helter-skelter Tango) that these symbolic media codes are positively phantasmagorical. This supposition, it seems to me, played also into the history of abstract art, which teaches us that art may refuse to recognize all thought as existing in the form of representation, and that by scanning the spread of representation, art may formulate a critique of the (so called) ‘laws’ that provide representation with its organizational basis. As a result, in my view, it was machine art’s onus to see what unconventional, paradoxical, summational sense art might make based on an appropriately decadent reading of the media machine.

Such a desiring-machine begins with the presumption that an information-loaded nuclear weapon had already exploded, showering me with bits of radioactive-like informational sound bites, thus drastically changing the way in which I perceived and acted, even in my subconscious dream world. Perhaps that is why Minóy’s In Search of Tarkovsky touched me so deeply, as did Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (1979). Seven years after the making of the film, the Chernobyl disaster occurred (on 26 April 1986) and led to the depopulation of a surrounding area officially called the zone of alienation, as with the Stalker film.

Minóy’s semi-harsh (while weirdly romantic) sound, by virtue of its distinctive electronic constitution of fluidity, floats in an extensive stratosphere of circulation―while also simultaneously is tied to the materiality of the physical ribbon in the cassette machine tape. Hence, the particular constitution of Minóy’s superimposing and overflowing compositions can be seen as a desiring-machinic membrane separating art from the general social power shaped by de-centered overload. This is its historical merit and current relevance.

I would also argue that the phantasmal machinic play found in his noisescapes has political/social ramifications in our media-machine saturated society. His excessive audio abstractions, such as Mass or Shame On Love (both 1986) or Pawbone Kisser Daylight Sins I (1993), can be seen and heard, in a sense, as a representation of representation―that is, when we attempt to think through them as an unlimited field of representation. This would be an attempt at scrutinizing representation in accordance with the sound’s phantasmal non-discursive process as desiring-machine, such as in his Distant Thoughts or The Last Fortune Cookie (both 1986), where he has demonstrated his art as an abstract machine-based metaphysics. Thus, Minóy’s desiring-machine noise music helps us step outside ourselves―and also outside of the mechanics of homogeneous machinic dogmatisms.

Minóy contributes to a desiring-machine noise art in which what matters is no longer sound identities, or logos; but rather dense, phantasmagorical forces developed on the basis of inclusion―bound tightly together and inescapably grouped by a vigor that is fermenting a phantasmagorical discourse which is both nervously desiring and, paradoxically, socially responsible.

3. Ghost in the Machine: A Final Reflection

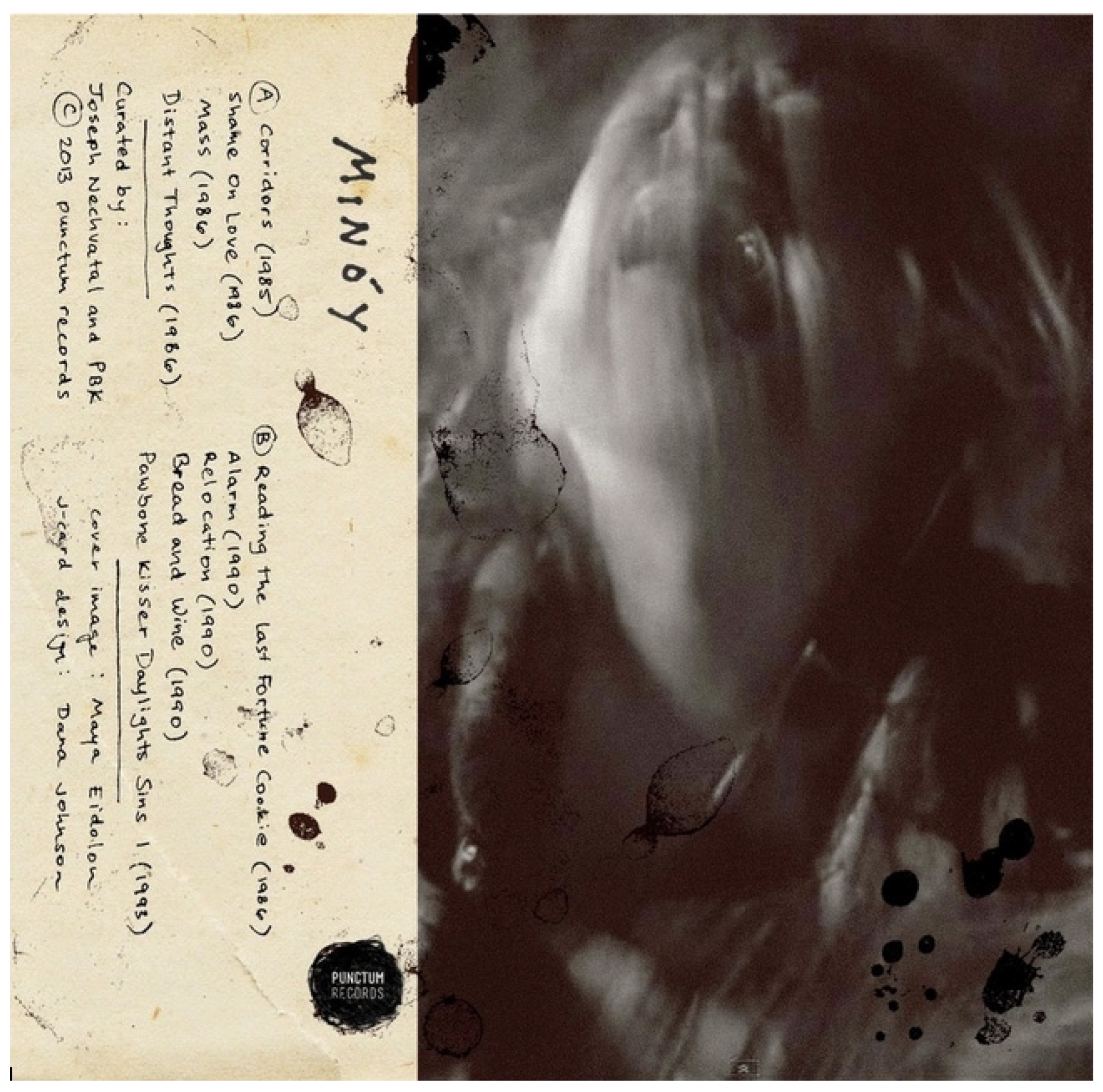

In 2013, composer (and Minóy’s former occasional collaborator) PBK (Phillip B. Klingler) worked out an agreement with Minóy’s partner, Stuart Hass, to obtain Minóy’s archive of recorded work after he passed away in 2010. In it PBK discovered that among Minóy’s master tapes were recordings made in the years after Minóy had stopped distributing his cassettes (it was widely thought that Minóy stopped recording in 1992). In 2014, Punctum Books released some of the best posthumous recorded material on CD and cassette, entitled simply

Minóy (

Figure 1). The

Minóy CD/cassette comprised nine audio compositions that span the years 1986 to 1993, drawn by myself and PBK from this archival material. These tracks were then ordered by myself, in collaboration with PBK. The tracks (spanning 1.2 h) in order are:

Corridors (1985),

Shame On Love (1986),

Mass (1986),

Distant Thoughts (1986),

Reading The Last Fortune Cookie (1986),

Alarm (1990),

Relocation (1990),

Bread And Wine (1990), and

Pawbone Kisser Daylight Sins I (1993). These nine audio recordings were accompanied by a Punctum book on Minóy, that I also edited (

Nechvatal 2014). The book, also entitled

Minóy, contains two written essays by myself, one by Maya Eidolon, and sixty black and white portrait images from the

Minóy as Haint as King Lear series that photographer Maya Eidolon (aka Amber Sabri) created before Minóy’s death.

This bevy of Minóy’s lingering sonic material is a project of personal transformation that also covers much of the sonorous scope of the second half of the 20th century, expanding the boundaries of the musical exploration of complex overtone structures. Minóy is a precise example of expansive post-John Cage abstract sound-music let loose upon the expanding machinic-electronic environment. Of course, Minóy’s sample-based sound-music is noise music. It’s often a bit antagonistic, irritating, and sometimes unpleasant, but it’s also exceedingly considered and put together beautifully with the utmost proficiency and comprehension. Yet a listener must fabricate a forensic fairy-tale out of its counter-mannerist machine mélange, as it keeps slipping in and out of idiosyncratic narration. As such, it recalls Gilbert Ryle’s ‘ghost in the machine’ criticism of René Descartes’ particular tactic of dualist detachment (

Ryle 1949). Minóy tears back that veil.

Minóy’s compositions―at the same time harsh and contemplative―were a direct influence on my

The Viral Tempest double vinyl LP (

Nechvatal 2022) at contains two long sound art compositions:

OrlandO et la tempête viral symphOny redux suite (2020) and

pour finir avec le jugement de dieu viral symphOny plague (2021). The contemplative register of his layered sound-music―achieved through superimposition as opposed to juxtaposition (for example in

Doctor In A Dark Room)―is noticeably different from other sample-based audio artists; such as the early sonic collage works of John Cage (

Williams Mix, 1952,

Fontana Mix, 1958–59 and

Rozart Mix, 1965), James Tenney (

Collage #1—Blue Suede, 1961), Steve Reich (

Come Out, 1966), Terry Riley (

You’re No Good, 1967), Negativland, John Oswald (

Plunderphonics), or Christian Marclay. I find Minóy’s superimposed sound aesthetic closer to that of the droning-fluttering audio décollages of Wolf Vostell and to some early work of Pierre Schaeffer (

Cinq Etudes De Bruits: Etude Violette, 1948), John Cage (

Radio Music, 1956), Pierre Henry (

Après La Mort 2: Mouvement En 6 Parties, 1967), and La Monte Young (

Two Sounds, 1960,

Poem For Tables Chairs Etc. Part 1 & 2, 1960, and

23 VIII 64 2:50:45–3:11 a.m. The Volga Delta From Studies In The Bowed Disc, 1969). Indeed, though exactly the opposite of Young in one way (Minóy’s released public output was prodigious, perhaps only surpassed by that of Merzbow, and Young’s is restrained), like Young, duration (time in terms of the distribution of flows) plays a large part in his compositions of assembly. And like Young, their lengthy layered complexity is a neurological stimulant for the machinic art imagination. Their extended length allows deep subjective perceptions to come to consciousness. As such, they offer a sonically ontological vision of the machine world as superimpositionally saturated. But it also suggests machinic-mentality as open-ended becoming―a machinic-mental place where we take on emergent forms in an intrinsically temporal play of agency. In that sense, Minóy’s machine noise music can be heard as a superimposed block of philosophical propositions that immerse us into rather different conceptions of being in the world.

Such a dynamic sense of machine art as nervous contemplation might suggest the continued potential of art as a tool of social re-configuration, as it subsumes our previous world of machine simulation/representation into a phantasmagorical nexus of overlapping extractions of post-human mentality. Encounters, then, with Minóy’s audio art, one may assume, might create an opportunity for symbolic societal transgression, and for a vertiginous ecstasy of thought.

For Minóy’s machine art conjures up a different ontological interplay of the human and the machinic-nonhuman. His productions speak powerfully of a dense, embodied, material engagement with the world at large. The sound of Minóy has us listening to (and looking for) pure visceral abandonment coupled with emergent aesthetic effects. His superimposed swirls and vortices of chance juxtapositions allows us to be carried away to a place where we are at once both the psychic co-author and the detached explorer of his compositions. Both an active and passive player at work in constructing its connotations.

This is one key point I want to emphasize: how Minóy shows us how originality based in co-directional creativity can still genuinely emerge in our machine-digital age of endlessly recycled culture by remaining in the thick of things. With Minóy we go to the superimpositional place of the intersection of the actual and the virtual―and the human and the machinic-nonhuman―in an open-ended searching process. Subsequently, I would say Minóy’s sonic material thematizes for us a thick ontology of layered becoming, as it entails an assembly between the human and the machinic-nonhuman, as well as an intrinsically sequential and superimpositional becoming at large.

The point to grasp is this: to appreciate Minóy’s machinic droning style of assembly depends on us living in the thick of things. His labyrinthian machine-like art sounds thematizes machine-human assemblies for us. Another general point I want to make here is that we should not be dazzled by Minóy’s machinic-phantasmagorical fields. His machine art merely delivers a well-directed irrational punch of negation to machine logic by tying together open methods of insouciant informality with visceral irony; at turns hip, flamboyant, and abrasively outrageous.