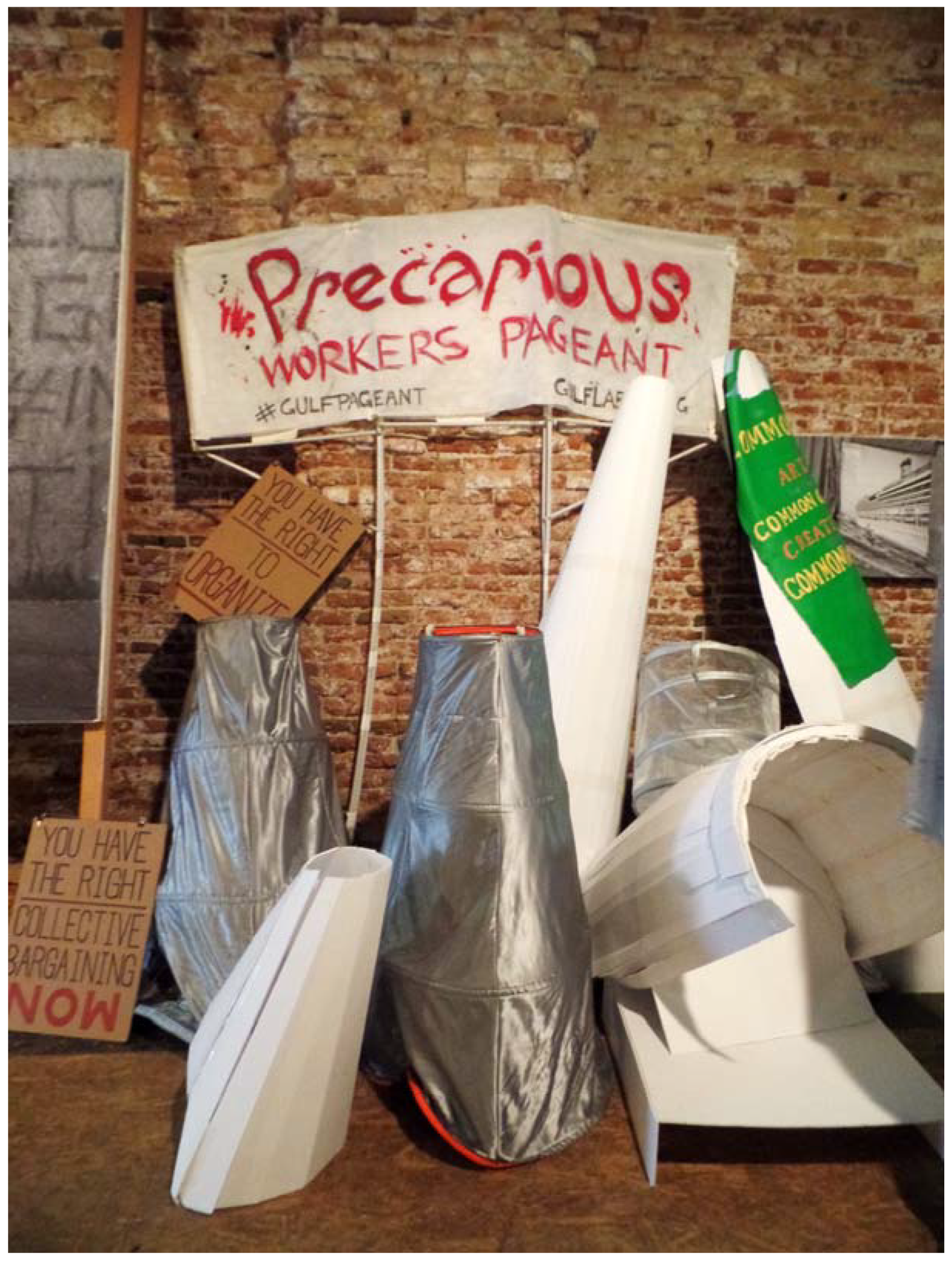

Precarious Workers Pageant, Venice B. 2015© Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

In this interview, NYC-based artist, writer, educator, and activist Gregory Sholette talks about the Precarious Workers Pageant project, reflecting on its aesthetic and political dimensions. He addresses the emergence of public spectacles generated by Russian Futurists and other avant-garde artists after the 1917 October Revolution as an inspiration to the project and the connections with carnivals as both a type of protest as well as a celebration. He also focuses on the aestheticization of the social event itself through activist art, precariousness, and the importance of activist aesthetics today.

1. Introduction

The Precarious Workers Pageant was a collaborative project involving members of the Workers Art Coalition, Aaron Burr Society, Occupy Museums, G.U.L.F. (Global Ultra Luxury Faction), and Social Practice Queens. It took place during the Venice Bienniale 2015 and its main subject was the labor conditions and the plight of migrant laborers working in the Guggenheim Museum, designed by Frank Gehry, on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi.

The construction of this building—which was on hold for several years and now scheduled for completion in 2025—has been accompanied by protests from human rights and labor organizations. These groups have denounced the labor conditions of migrant workers from South Asia and North Africa who traveled to the region for jobs that are extremely exploitative, “with employers confiscating their passports, withholding salaries, and enforcing grueling around-the-clock work schedules” Cascone (2021). One of those organizations is the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition, which has kept pressure on the Guggenheim Museum for over five years through meetings and public demonstrations.

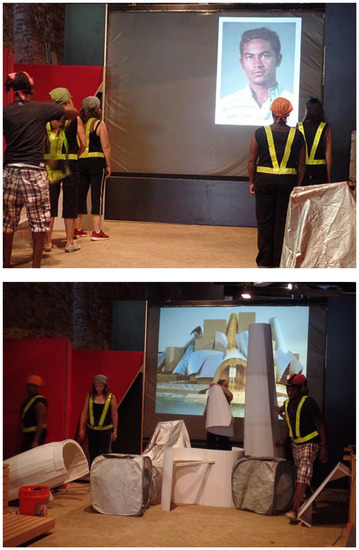

In Venice, members of the associations participating in the pageant joined together to celebrate the work of Gulf Labor. Calling for an end to the use of migrant labor at the forthcoming museum, the project began with a performance inside S.a.L.E. Docks Cultural Center, where a model of Gehry’s proposed architecture was deconstructed into pieces. Then, the pieces were carried outside in a cacophonous demonstration over canals, passed the Peggy Guggenheim Museum, and finally stopped at the square in front of Gallerie dell’Accademia. There, the pieces were reconstructed to form a temporary public commons. Inside this alternative Gehry space, a group of speakers addressed the struggle for social justice that is faced today by all precarious workers including art workers.

The performers of this collective performative experiment who had deconstructed the model of Frank Gehry’s proposed Guggenheim Museum posed the question “Who Builds your Architecture?”. They had fabricated portable, modular pieces out of the model of the museum such that these could be carried by individual participants through the streets of Venice. They paid attention to the symbolic meaning of the emergence of abstraction in the early 20th century, saying that “What we want to do is call attention to the fact that you can’t disconnect the utopian vision of the early avant-garde in its interest in abstraction from those shapes and forms without doing violence to the concept” Sholette (2015).

As guest editors of the Special Issue Eight Hours Labour, Eight Hours Recreation, Eight Hours Rest: What We Will Need Is More Time for What We Will (?)

We interviewed Gregory Sholette, an artist, writer, activist, and member of Gulf Labor, about this project and the interconnections with his theoretical work.

Precarious Workers Pageant, Venice, Italy—7 August 2015. Shot taken at 6.30 min and edited by Setare S. Arashloo.

Vimeo link: https://vimeo.com/159525389 (accessed on 27 December 2021)

Gregory Sholette is an NYC-based artist, writer, educator, and activist whose art and research investigations focus on activist art, collective cultural labor, and counter-historical representation.

2. Interview

Guest Editors: The Precarious Workers Pageant project was held in Venice during the 2015 Biennale. However, it was not part of the official event. Why did you choose this location for the performance?

Gregory Sholette: Three reasons led us to situate the Precarious Workers Pageant (PWP) event in the Dorsoduro neighborhood of Venice during the hot Summer of 2015. First, the Gulf Labor Coalition (GLC) had already been invited by the late curator and poet Okwui Enwezor to participate in his Biennale that year. Our (GLC’s) contribution included a series of informational panels focused on art, labor, and capital as well as the book High Culture/Hard Labor published by OR Books (https://gulflabour.org/venicebiennale2015/ accessed on 27 December 2021). At Okwui’s request, we also provided a wall banner that he hung in the Arsenale. He later told me at an event that the Guggenheim administrators were very unhappy with him over GLC’s inclusion. Looking back now, I realize that this was the last time we would ever speak: Okwui died in 2019. Additionally, the Dorsoduro in Venice was the location of the S.a.L.E. Docks Cultural Center, which was hosting our performance (Figure 1). It is also where the Peggy Guggenheim Museum is located. It was at this museum branch that Global Ultra Luxury Faction (G.U.L.F. is a splinter group of GLC) made a marine landing in May of 2015, the week of the Bienniale’s opening, and then proceeded to occupy the institution’s dock on the Grand Canal for the better part of a day. This occupation achieved the results that we were seeking, which was to finally meet with Guggenheim Trustees rather than only with museum director Richard Armstrong, who seemed incapable of moving the human rights goal forward, despite his years of assuring us that he was sympathetic to our concerns. Following our day-long occupation of the Peggy Guggenheim house, their Board of Trustees finally promised to meet with Gulf Labor and to discuss ways they might build their new Abu Dhabi museum using fair labor contracts developed by pro-worker NGOs such as the International Labor Organization and the Woodworkers International. However, Gulf Labor was then put in a delicate position regarding negotiations with the Guggenheim. The Trustees insisted that Gulf Labor hold off on any new interventions in their museum spaces in the lead up to any meeting. For me, this meant that a last minute reframing of PWP was necessary.

Figure 1.

Precarious Workers Pageant, S.a.L.E. Docks, ©Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

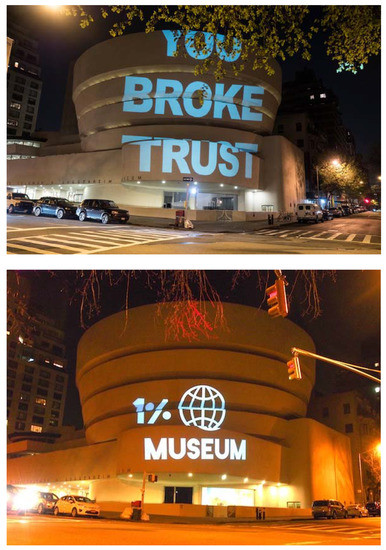

At this point, in the Spring of 2015, the project had already been in the works for over a year, including fabricated props, regular rehearsals at my college, and financial support from a City University grant I received through the Center for Humanities (Figure 2). No one wanted to see it terminated, but our agreed self-moratorium on actions meant that I had to transform the PWP into an independent project with no official connection to Gulf Labor (although some members of the group were participants). Therefore, PWP not only was not officially a part of “All The World’s Futures”, the 56th Venice Biennale of Art but also was not officially a project of the Gulf Labor Coalition either. As it turned out, the three-hour meeting with the Guggenheim Trustees that finally took place in February of 2016 ultimately led nowhere and appears to have been agreed upon in bad faith from the start on the part of the Guggenheim. Only a few months after the meeting, the museum broke off all negotiations with GLC as well as with our humanitarian NGO partners1. We carried out one more public action in collaboration with The Illuminator by projecting our indignation with the Trustees directly on the façade of the museum on 5th Avenue in NYC2 (Figure 3). However, the project did not move forward. As much as I would love to give GLC, G.U.L.F., and PWP credit for this, in reality, it seems that, with the collapse of crude oil prices at the time, the Abu Dhabi Guggenheim project was put on hold. Now that appears to be changing again with the recent announcement that the museum will be completed in 20253.

Figure 2.

Precarious Workers Pageant meeting, © Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

Figure 3.

Global Ultra Luxury Faction (G.U.L.F.) and The Illuminator projection messages on the outside of Guggenheim Museum, NYC, © Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

Guest Editors: The most visible part of the project was the pageant you organized. When we see the images of the participants walking along the canals and streets and, afterwards, performing outside the Gallerie dell’Accademia, the parallels with a demonstration are clear. There are posters, chants, music, and speeches. On the other hand, mainly because of the props—the deconstructed abstract elements of Gehry’s building—the pageant seems to summon the carnivalesque, which according to Mikhail Bakhtin, is used to produce a symbolic inversion in the context of demonstrations. Why did you call it a pageant (in the sense of a procession) and not a demonstration? What is the role of aesthetics in this project?

Gregory Sholette: I really enjoy this connection that you have made here with Bakhtin and agree that the invocation of carnival as both a type of protest as well as a celebration was very important to the concept of PWP; I will address the specific historical reference of the project’s visuality in a moment, but the question of activist aesthetics is very important today, and even more so, I think, than in 2015, following the sweeping monument take-downs (what I call monumenticide) and the public protests of the Black Lives Matter movement that same year. Visualize this rise in an assertive, visually grounded public resistance. It is almost inescapable as these optics of opposition are amplified via the mass media, tweets, Instagram, Facebook, and other social networking platforms. I do not believe anyone today can deny the emergence of an “aesthetics of protest” in recent years, one whose material and sensual reality is manifested in a complex way.

For, what do we see? Bodies self-choreographed in exquisite public movements, bold graphic political imagery carried through streets, exclamatory texts, aural sound eruptions, and chants that electrify social spaces—the power of such protest aesthetics unfolding as it does within a spectacularized society is a phenomenon particular to our present moment. The diverse aesthetic sensations generated by the sweeping events of Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring, up to the urban protest actions against white supremacy following the police murder of George Floyd: these do not merely involve putting artistic forms to use for political movements but are simultaneously both a political and an aesthetic phenomenon in their own right. Additionally, in this sense, the art of protest is also a significant overturning of Walter Benjamin’s heedful anti-authoritarian thesis in which he suggests that Fascism aestheticizes politics as a militarized mass spectacle while communism politicizes culture in order to reveal the unequal property relations and forms of exploitation particular to capitalist society. As I see it, and as I argue in my new, forthcoming book The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art (Sholette 2022), this recent inversion of Benjamin’s thesis results from a phenomenon that was only in its infancy during his lifetime (1892–1940). What the philosopher glimpsed in its embryonic stage and what the Situationist International confronted decades later is the full-on aestheticization of the social itself. This process now unfolds everywhere, including inside the workplace, in the classroom, within the home (if one has a home), via the Internet and cellular communications devices, and in all of the affective spaces between us as well as perhaps even in our minds, as we encounter new advertising technologies that are capable of encroaching on the very territory of our unconscious dream lives4.

What I am saying, therefore, is that, when life becomes an unending capitalist consumer pageant, when even news reporting is a form of entertainment, then the horizon of potential resistance is also radically altered. Thus, the aesthetics of political protest and the art of public demonstrations has become more of a continuum with activist art rather than a separate area of mediated or representational practice. This change is, to my mind, a truly remarkable situation in which the implications are not yet fully understood or even predictable.

Guest Editors: In the video of the project, in a voice over, you say that “For the early 20th century avant-garde, abstraction was a way of pointing to a different kind of society”. You clearly make this connection with the present, recovering the abstract forms of Gehry’s project. The understanding we make of this is that you want to show how, on the one hand, this language was appropriated by capitalism to exploit workers and to take advantage of the vulnerability of migrants under the guise of the avant-garde. On the other hand, there also seems to be a tribute to what the avant-garde of the beginning of the 20th century represented as a social proposal. Can you comment and develop your intentions when you made the association between abstract language and the proposal of a different society?

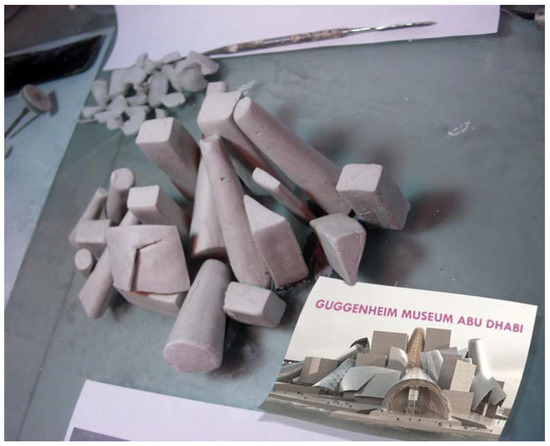

Gregory Sholette: PWP’s primary inspiration came from the startling public spectacles generated by Russian Futurists and other avant-garde artists after the 1917 revolution. One of the aims of these street performances was to transform familiar urban spaces into radically re-imagined places of mass cultural participation. Perhaps the best known of these public projects was the reenactment of the “storming” of the Winter Palace in St Petersburg (Petrograd at the time) that Lenin considered the turning point in the Bolshevik revolution. Additionally, I put storming in quotes because the actual event was in fact uneventful, more like a turning over of power from one group of soldiers to another. However, three years later, in 1920, the theater director Nikolai Evreinov recreated this event with a far grander and heroic vision using sets created by painter Yuri Annekov and employing a cast of thousands that included, along with citizens; students; ballet dancers; and circus acrobats, a battalion of bayonet-wielding Red Army soldiers brought in from the German front just for this production. (I recommend this overview of the event by Peter Lowe: https://www.pushkinhouse.org/blog/2018/11/25/the-1920-mass-spectacle-which-blurred-the-lines-between-of-the-october-revolution accessed on 27 December 2021). This was a more realistic version of street spectacle than the futurists’ version of these pageants of course. The latter employed gigantic geometric shapes in city plazas, although in all of these performative events, the re-imagining of communal space was central, along with an explicit or implicit narrative about the possibilities of an emerging future that is positively and radically different from the past. For many artists, abstraction was the language of this revolutionary tomorrow, perhaps because the use of geometric shapes seemed to offer a complete break with centuries of representational art, although there is interesting scholarship on the possibility that this same geometric aesthetic linked backwards to the tradition of Russian icon painting. In any case, the aesthetic of PWP in 2015 was drawn in part from these early 20th century avant-garde participatory projects. However, it invoked a critical twist within them. Frank Gehry’s architecture also invokes this same geometric and abstract tradition, but in the context of Abu Dhabi in particular, this vanguard aesthetic offers a façade that is also a charade of sorts (Figure 4). It recalls a moment when the working classes and peasants attempted to break free of their servitude to capitalism and the bourgeoisie but, now, in conditions completely subsumed by global capitalism and the bourgeoisie. It is also made possible, let me add, by the environmentally malevolent petroleum industry of the United Arab Emeritus. Therefore, PWP deconstructed the deconstructivist vision of Gehry and the Guggenheim, seeking to symbolically free abstraction from this historical contortion(Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Precarious Workers Pageant, Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum mockup clay copy © Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

Figure 5.

Precarious Workers Pageant, Vaporetto Mockup 1%, © Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

Guest Editors: Finally, in front of the Gallerie dell’Accademia, one of the participants says that all of you are in solidarity with migrant workers from Abu Dhabi and “think what we can do that also is related to our own situation as precarious art workers”. In your book, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (Sholette 2010), you reflect on how the commodified art system works, where the vast majority of artists are marginalized, although they are essential to the survival of the mainstream (or the most distinguished within the mainstream). Do you see a relationship between the marginalization of most artists and their precarious working conditions? In this project, how do you establish the connection between precarious art workers and other precarious workers?

Gregory Sholette: I believe you are referring to PWP participant Nitasha Dhillon, who makes the link between precarious labor and artistic labor and who is part of the groups MTL, G.U.L.F. (Global Ultra Luxury Faction), and Decolonize this Place, collectives that have produced substantial theorizations about the questions you raise, acknowledging the contradictions of being in a space of privilege as Western world artists while seeking to reveal the similarities with precarious labor in the Global South (Figure 6). Here, for example, is one such insight from G.U.L.F.:

We recognize that our work, our creativity, and our potential are channeled into the operations and legitimization of the system. We work—often precariously—as both exploiters and exploited, but we do not cynically resign ourselves to this morbid status quo.(Global Ultra Luxury Faction 2015)

Figure 6.

Precarious Workers Pageant, © Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

Even as capitalism today celebrates a profound and historic victory over almost all other forms of human production (including socialist modes of labor and electronically networked communities as much as art and older artisanal crafts), the system is being rocked by one economic and political crisis after another. Additionally, into that scandalized space steps the possibility of counter-production and counter-practices that are always present within or at the margins of the marketplace. This shadow zone also sometimes bears a certain resemblance to forms of avant-garde art, as much as it does extra-parliamentary forms of collective dissent that have long haunted and at times directly confronted capitalism. Think of this as a type of dark matter archival agency, a species of invisible cultural labor that nevertheless is essential to the maintenance and reproduction of the system of high culture as a normative whole. Put differently, this aesthetic of protest provides a militant embodiment to the mass of generalized human labor that has been made precarious and ultimately redundant by neoliberal capitalism (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Precarious Workers Pageant, © Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

Still, I am not suggesting that artists represent some privileged category with regard to precariousness, but note that what truly distinguishes the political economy of art under capitalism is first its necessary overproduction of artistic labor. Think of the endless turning-out of university-approved art degrees, and second is the way this very same glut of art and artists serves to invisibly maintain and reproduce the mainstream art world. This is a formula that art historian Carol Duncan first observed in 1984, at the dawn of art’s globalization, in a provocative essay entitled “Who Rules the Art World?” (Duncan 1983) (My re-reading of her text is here: http://www.gregorysholette.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Sholette-What-Do-Artists-Want-.pdf accessed on 27 December 2021). Things have gone from bad to worse ever since, yet thankfully, there is also push back stemming from the 2008 economic collapse that seems to have made visible these previously concealed precarious workers that were for so long simply taken for granted by most art world institutions. Today, the actual conditions of artistic production are becoming a topic of heated discussion. Non-salaried and junior museum staff members, many of whom studied art or art history, and some of whom are still working artists, are challenging their employers across the United States by denouncing toxic board members and by forming unions to demand better pay and working conditions.

What I want to suggest, therefore, is that the common status most artists share as a productive surplus, or what I have elsewhere described as precarious artistic dark matter, is also precisely where this emerging aesthetics of protest is taking root, including in its decolonial activist formation. If this is so, then I think it also suggests a significant change in artistic subjectivity itself, as activist artists today are less influenced by a bygone avant-garde imaginary than by their own immediate circumstances involving repetitions and redundancies as much as the dynamic repurposing and reactivation of a dark matter archive filled with fragmented and boisterous interventions, experiments, compromises, as well as minor victories and outright failures (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Precarious Workers Pageant, © Gregory Sholette and used with permission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.C.; methodology, C.P.C., A.D., C.M. and H.E.; investigation, C.P.C., A.D., C.M. and H.E.; resources, C.P.C., A.D., C.M. and H.E.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.C.; writing—review and editing, C.P.C., A.D., C.M. and H.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under the project [SFRH/BPD/116916/2016].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | For further information see: Gulf Labor Artist Coalition (2016). |

| 2 | For further information see: Embuscado (2016). |

| 3 | For further information see: NewsHome (2021). |

| 4 | Coors Brewing Company is working on a means of infiltrating dreams with commercials for its beer. See: Gabbatt (2021). See also: https://www.science.org/content/article/are-advertisers-coming-your-dreams (accessed on 27 December 2021). |

References

- Cascone, Sarah. 2021. After Delays, Protests, and a Pandemic, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Has a New Date for Its Debut: 2026. ArtNet. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/guggenheim-abu-dhabi-20113519 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Duncan, Carol. 1983. Who Rules the Art World? In The Aesthetics of Power: Essays in Critical Art History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 172–80. [Google Scholar]

- Embuscado, Rain. 2016. Protest Group Lights Up Guggenheim’s Facade with Message for 1 Percent. ArtNet. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/light-projections-guggenheim-museum-gulf-484280 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Gabbatt, Adam. 2021. Nightmare Scenario: Alarm as Advertisers Seek to Plug into Our Dreams. The Guardian. July 5. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/jul/05/advertisers-targeted-dream-incubation. (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Global Ultra Luxury Faction. 2015. On Direct Action: An Address to Cultural Workers. e-flux Journal. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/65/336530/on-direct-action-an-address-to-cultural-workers/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Gulf Labor Artist Coalition. 2016. Gulf Labor Responds to Guggenheim Breaking off Negotiations. Available online: https://gulflabour.org/2016/gulf-labor-responds-to-guggenheim-breaking-off-negotiations/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- NewsHome. 2021. By 2025, Abu Dhabi Has Committed to Building the Long-Awaited Guggenheim Museum. Available online: https://allnewshouse.com/by-2025-abu-dhabi-has-committed-to-building-the-long-awaited-guggenheim-museum/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Sholette, Gregory. 2010. Dark Matter Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sholette, Gregory. 2015. Protest and Performance at the Venice Bienniale Venice, Italy. August 7. Available online: http://www.gregorysholette.com/precarious-workers-pageant/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Sholette, Gregory. 2022. The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art. London: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd., Available online: https://www.lundhumphries.com/products/the-art-of-activism-and-the-activism-of-art (accessed on 27 December 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).