Abstract

Ruins serve as a poignant reminder of loss and destruction. Yet, ruins are not always physical, and they are not always best understood through visual language—the sense memory of loss extends for displaced people far beyond crumbling monuments. Exploring the sonic element of loss and displacement is key to understanding the way people relate to the spaces they have to leave. This article explores the particular disjuncture of staging and commemorating Arabness in Tel Aviv, the “Hebrew City.” The disjuncture of being Arab in Tel Aviv is apparent to any visitor who walks down the beach promenade, and this article examines the main sites of Arab contestation on the border with Jaffa. Most apparent to a visitor is the Hassan Bek Mosque, the most visible Islamic symbol in Tel Aviv; I describe the process of gaining admission as a non-Muslim, and of discussing the painful and indelible memory of 1948 with worshipers. Delving deeper into the affective staging of ruin, I trace Umm Kulthum’s famous concert in Jaffa (officially Palestine at the time), and examine the way her imprint has moved across the troubled urban border of Tel Aviv-Jaffa. A ruins-based analysis of the urban sites of disjuncture in Tel Aviv, therefore, offers a glimpse into underground sonic subcultures that hide in plain sight.

“Know that if a wound begins to recover, another wound crops up with the memorySo learn to forget and learn to erase itMy darling everything is fatedIt is not by our hands that we make our misfortunePerhaps one day our fates will cross when our desire to meet is strong enoughFor if one friend denies the other and we meet as strangersAnd if each of us follows his or her own wayDon’t say it was by our own willBut rather, the will of fate.”

These are the closing words of “al-Atlal” (“The Ruins”), the poem written by Ibrahim Nagi, immortalised by Egyptian musical legend Umm Kulthum in her 1966 rendition. It is a masterpiece of Arab music, invoking themes of decay and unrequited love, and it expresses the pain of rupture and loss. Walking through what was once Manshiyya, the neighbourhood that connected Tel Aviv and Jaffa until it was razed following the War of 1948, recalls the poem’s uneasy relationship: two cities, Tel Aviv the “Hebrew” and Jaffa the Arab, cities joined together by fate, ripped apart by history, then sown back together by the victors. Separated in 1934 but officially and rhetorically conjoined by a hyphen since 1950, one may wonder what these cities are to each other? Sisters? Strangers? Inseparable enemies?

Prior to 1948, Manshiyya was the northernmost neighbourhood in Jaffa hugging the Mediterranean. Following the exile of its residents in 1948 (Kadman 2015; Khalidi 1992), it was razed by the Israeli government. The population was mostly Muslim, and relations with Jewish residents and immigrants transpired in Arabic through trade. At the same time, any long-standing claim to rootedness in the land such as those of the fellahin, the expelled Palestinian peasants in rural areas, is doubtful. Most of the residents of Manshiyya migrated there from near regions of the Ottoman Empire beginning in the 1870s. Many arrived as workers and administrators for the Empire, often from Egypt (Jacobson and Naor 2016, p. 128). Over the course of a century, they built a neighbourhood on the northern border of Jaffa, in which tin-roof houses went right to the shoreline, and historic aerial photographs indicate that it was among the densest segments of greater Jaffa.

When the Jewish suburbs of Jaffa were incorporated into the new city of Tel Aviv (established in 1909), Manshiyya remained part of Jaffa, only incorporated into Tel Aviv after the total victory of the Israelis in the battle for Jaffa in April/May 1948. That battle, which saw the exile (fleeing or expulsion) of 95% of Jaffa’s population, turned the formerly Ottoman-ruled Arabs into stateless Palestinian refugees. Manshiyya is, therefore, a microcosm of Tel Aviv-Jaffa (or even Israel-Palestine more broadly) in so far as its landscape represents a history of pain and complexity (Bernstein 2012, p. 134). Barbara Mann’s formulation of a “fractured synechdoche” is apt (Mann 2015, p. 88), defined as “a part whose relation to the whole of the nation is incomplete or flawed.”

Among Tel Aviv-Jaffa’s neighbourhoods,1 Manshiyya is now known more for being an urban void than for its architecture. Prior to 1948, it was a dense neighbourhood (once northern Jaffa, now southern Tel Aviv) in which local Arabs and newer Jewish arrivals—both Ashkenazi and Sephardi/Mizrahi2—frequently mixed with one another (Jacobson and Naor 2016, p. 137). Today, the area comprises a series of beachfront parking lots connected by hotels and very few new developments. Much of the evidence of Arab life before the establishment of the State of Israel has been razed and paved over, and the people who inhabited it scattered across the Middle East. Yet, in the words of “al-Atlal,” “if one friend denies the other… we meet as strangers…” In this urban void, among the scattered ruins, incongruous relationships of people thrown together by fate play out. On Fridays, Arab3 taxi drivers from across Israel visit a mosque—Hassan Bek—that is all that remains of their parents’ and grandparents’ neighbourhood. French Jewish immigrants whose grandparents were once called Moroccans find themselves once more in a space where they coexist with Arabs.4

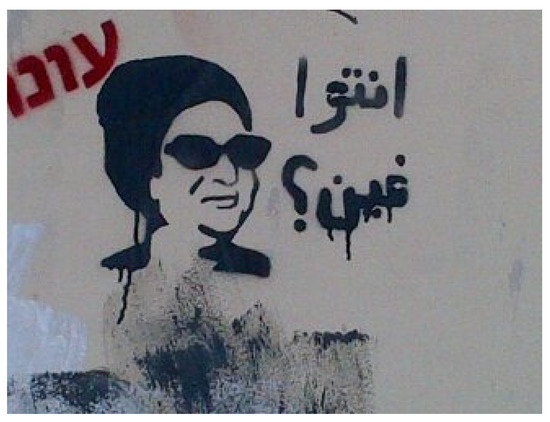

This article explores this border space, the phantom of Manshiyya, through its sensory, aural and discursive traces, and the double metaphor of ruin as both ghostly but extant reality and sign of loss and absence. In May 1935, Egyptian musical legend Umm Kulthum made a trip to Jaffa, then the cultural capital of Mandate Palestine, launching a tour of the Levant. The Jaffa concert became something of legend, and yet there is little more than a trace of it in the records and archives. Attendees are no longer available for interview, but in place of first-hand testimony, there are stories of “Umm Kulthum in Jaffa” that have become common currency among Jews, Israelis, Arabs and Palestinians (see Figure 1). These stories, like those of Hassan Bek, “the last mosque in Tel Aviv,” and the memories of music and ritual they evoke, restore something of the lost world of Manshiyya. They are a struggle against ruin as absence and erasure, namely the military and ideological strategy pursued by the Israeli authorities of clearing the land of landmarks and people. By freighting the remains of Manshiyya with these stories, memories and sensations, I hope, in a modest way, to help preserve the space from more recent forms of ruin making. However, I also wish to draw attention to ruins as what remains after erasure. These traces of the past, revived and reconfigured by more recent demographic and cultural transformations, “make[s] the […] city readable.” (de Certeau 1984, p. 92). They prompt people, such as my Hebrew-speaking research consultants, to say about a seeming void “there was something here” (haya mashehu po).

Figure 1.

Umm Kulthum’s face stamped on a wall as street art in Tel Aviv. Photo courtesy of the author.

If one follows Josh Kun’s directive to listen for buried histories, the sonic cues of ruin are everywhere (Kun 2000). A border between Tel Aviv and Jaffa is fragile not just because the urban geography of the two cities is unstable, but because the sensory experience of the “joined” cities bleeds gradations of Arabic language, culture and ethnicity that traverse and blur the border. With the painful memory of loss from “al-Atlal” as a backdrop to the “fractured synechdoche” (Mann 2015) of the “paper border” (Aleksandrowicz 2013), this article focuses on the way that sound, and particularly the intense sense memory of local sounds, shapes a border that is undefined and largely unpoliced. Employing ethnographic methods of the semi-structured interview, observation, and discourse analysis, the project of analysing the Arab sounds of Manshiyya is an attempt to capture the sensory dynamic of ruin.

As a methodology, exploring the complex dynamics of ruin within urban space in Tel Aviv-Jaffa requires walking its streets. In de Certeau’s framing, “Walking affirms, suspects, tries out, transgresses, respects, etc., the trajectories it ‘speaks’” (de Certeau 1984, p. 100), and Ziad Fahmy expresses this adeptly in his new book:

“De Certeau’s depiction of street life ‘down below,’ captures an embodied, extra-visual sensory knowledge that ordinary urban dwellers have of their immediate environment … By ‘listening in’ to street life, we can partly reveal how people lived their everyday lives and, more importantly, clarify how they dealt with state authorities in their mundane struggles over the use and ownership of public streets. Compared to other approaches, a sensory approach is also more embodied and intimate”.(Fahmy 2020, p. 23)

To probe Manshiyya’s sensory landscape is to immerse oneself in the zones of distinction between the Hebrew and the Arab in this disjoined city, and to engage with the discourses surrounding peoples’ sense memory and family narratives. In the sections that follow, I explore the border in Tel Aviv-Jaffa in the context of ruin and rebuilding, and I share descriptions of several sites of intense sonic sense memory for residents. In discussions of the Hassan Bek Mosque, the sea, and Umm Kulthum’s 1935 concert in Jaffa (Tel Aviv?), we recount the variety of struggles to resist erasure in a zone characterised today by silence and absence.

1. Ruin and Rebuilding

The transformation of a dense neighbourhood of Arab houses into a site of ruins (harisot) transpired in two stages. First was the expulsion in April and May 1948, in which the population of Manshiyya was redistributed across Jaffa, Ramle, Gaza, Jordan, and further afield (Golan 1995). The second stage transpired across the 1950s and 1960s, of razing the houses and paving the streets, building parks and hotels over some of the empty space, and transforming it thoroughly into a non-place (Augé 1995). Many of the remaining Jaffa residents have lived eventful lives, often including strained and adversarial relationships with the state. Abu George is one such figure, something of a legend in Jaffa, a Christian whose experience of 1948 was nothing short of extraordinary. His father was the lighthouse watchman (migdalor) at the port in the north of Tel Aviv, and during the war, he was hidden by Jewish neighbours who worried that the family would be expelled. After the war, the family re-settled first in Salama, a village northeast of Jaffa, then in the neighbourhood of ‘Ajami, where he has been a fixture for decades. Abu George describes the emptying of Manshiyya:

“They destroyed it all: all all all (hem harsu hakol—hakol hakol hakol). Some Hinnawi houses remain,5 but most of the land was sold. New people moved in, people I knew, Israelis. Sometimes people would go out and when they came back someone else was [living] there.”(Interview, February 2018, Jaffa)

The first part of this statement, the emphasis on total destruction, appears indisputable to anyone who casts an eye on this neighbourhood. The second part of his account reveals, however, that the border between even Manshiyya and its surrounding Jewish neighbourhoods was vague and subject to exemptions from destruction for new Jewish immigrants. I asked Shimon, a tour guide-historian, and he explained it this way:

“In the 40s and 50s, there was a great migration from Greece. They settled in Jaffa. There was a big Aliyah from Bulgaria. They settled in Jaffa. In Jaffa, there were a lot of empty houses. So the government—or they went there from the transit camp (ma’aberet) Bat-Yam—there was a big transit camp there—or the state said to the ma’abarot ‘go to those Arab houses, they’re not coming back.’”(Interview, February 2018, Tel Aviv)

The absentee property law of 1950 (referenced implicitly) benefited Jewish immigrants for the most part,6 but Abu George’s family was also resettled in an abandoned or “empty” house. They were moved first to Salama, a village that has now been restyled as a Jewish neighbourhood of Kfar Shalem. As Abu George explains, after 1948, “Salama, suddenly, didn’t have a church or Christians,” and they were moved to ‘Ajami along with most of Jaffa’s remaining Arab population. Abu George concurs about the impact of Bulgarian immigration, but it comes out differently. He says:

“Anyone who wanted to stay, and it was legal, stayed. The Bulgarians stayed. They built from Yefet down to Sderot Yerushalayim—full of Bulgarians today—you can buy bourekas there until today.”(Interview, February 2018, Jaffa)

His qualification that anyone who was permitted to stay did so is striking, since he himself was resettled in ‘Ajami. Additionally, it is also fascinating that he can move so fluidly from destruction to the rebuilding of the neighbourhood, and especially how Jaffa and south Tel Aviv developed in the early years of the State of Israel. He says, “Things changed in ’67. Building started. Ashkenazim, Greeks—they moved out to Herzliya and Petach Tikva. North north north (tzfona).” (Interview, February 2018, Jaffa)

As for remembering life before 1948, the picture is complicated. We have, through the memories of Jewish resident Yosef Eliyahu Chelouche, plenty of detail about daily life in the neighbourhood,7 including the local soundscape, and his great-grandson Tomer Chelouche dispenses family stories freely:

“If you had walked around the streets (see Figure 2), you would have heard children running around, to Chelouche Bridge, they’d run there twice a day to see the train pass, it made a lot of noise, and they’d try to drop a stone into the conductor’s box, I don’t know if they succeeded, but they tried. Tuesday was the only day of the week where they didn’t play in the street, it was much quieter, because Tuesday was laundry day and they hanged the clothes in the street so it was a quieter day.” Figure 2. Nameplate for Chelouche Street in Neve Tzedek. Photo courtesy of the author.(Interview, February 2018, Tel Aviv)

Figure 2. Nameplate for Chelouche Street in Neve Tzedek. Photo courtesy of the author.(Interview, February 2018, Tel Aviv)

Abu George remembers this, too, and he remembers the way the neighbourhoods around Manshiyya were demarcated ethnically: “On Chelouche there were a lot of Europeans from Poland, that was the centre for Europeans. Shabazi was mixed.” (Interview, February 2018, Jaffa).

However, Tomer continues that the memories are complex for his family:

“There was actually forgetting (hashkacha), because there’s really been an effort to erase (limkhok) Manshiyya. What we have today as Chelouche House isn’t actually the family’s first house outside of Jaffa, but the second house outside of Jaffa. The first was in the neighbourhood of Manshiyya, and the one we identify today is the second one, which was in Neve Tzedek.8 So it’s doubly interesting (me’anyen pa’amayim). First it’s interesting because Manshiyya was founded as a neighbourhood for the rich. And whether they were Jewish or Arab, rich people built a house in Manshiyya—it was a luxe neighbourhood on the shoreline, but it wasn’t the shore, it was Manshiyya. And the house that was the Chelouche house in Manshiyya remained until the War for Independence, and then it was destroyed I think, not during the war but after. (He [Aharon Chelouche] eventually wanted a bigger house so he built in Neve Tsedek and that was their second house.) What’s interesting is that he wanted to build a house outside of Jaffa and he went to Manshiyya, but he eventually decided he wanted to live among his Jewish brothers and moved to Neve Tsedek. That’s important in our understanding of Jewish-Arab relations in that period.”(Interview, February 2018, Tel Aviv)

Nearly everyone I interviewed confirms that life was ethnically segregated even before the Battle for Jaffa, with the notable exception of the bars, cafes and brothels (see Bernstein 2012, p. 123, Jacobson and Naor 2016, pp. 136–42). Brothels came up frequently in interviews, describing the relationships between (often orphaned) young Jewish women and Arab men (and see Zochrot 2010). That aesthetic of grit and disrepute transitioned easily in the 1950s and 1960s into a reputation for the area as undesirable aesthetically and ethnically. In interview, my research consultants mentioned the rise of housing estates (shikunim) and the notorious rubbish dump (mizbala) of northern Jaffa as represented in the film Salah Shabati (see Erez 2018, p. 98). Ruin, therefore, became the aesthetic of Manshiyya, with moral ruin being part of its mythologising.

The ethnic and class-based sorting in this border neighbourhood does not apply exclusively to the Israeli–Palestinian binary, either. In his article on “Salomonico” and the bourekas films, Oded Erez examines the transition through the 1960s for immigrants from Salonica from Greek to Mizrahi (Erez 2018, p. 97), mostly facilitated through media portrayals by class bias, or what Amy Horowitz calls “Style as a culture map” (Horowitz 2008, p. 135). Ziad Fahmy goes a step further, arguing that musical taste and street sounds, as part of classist propaganda that marginalises the working class culturally and discursively, constitute “the intersection of modernity, class formation, and state power” (Fahmy 2020, p. 216) in Egypt. It is, therefore, worth noting that all of the Jewish frontier neighbourhoods surrounding the border zone are too expensive today for even the average Tel Avivan, as they are being rebuilt by upper-class French immigrants bringing professional qualifications and paying in Euros. They are coded as European, having adhered to Fahmy’s formula above, but their parents were born in north Africa and they pray in the Sephardi liturgy. Rabbi Avraham Lemmel, the Ashkenazi rabbi of Tziyon Lev synagogue, the French synagogue in Neve Tzedek, explained their liturgy to me in this way:

“Some of the tunes [niggunim] we sing as the Tunisians do: when we bring out the Sefer Torah [Torah scroll]. We make some tunes Iraqi because of the place,9 some Moroccan, some Tunisian. Kriyat hatorah [chanting from the Torah scroll] depends on who comes that day. Most of the time it is Moroccan, it is Tunisian, Iraqi, Algerian.”(Interview, February 2018, Jerusalem)

The blending together of different north African liturgies is part of a wider story of a class-based ethnic sorting that has characterised south Tel Aviv for decades. Yet, the arrival of each wave of immigrant, far from being inevitable, is part of the aesthetic of rupture that shapes Manshiyya and its immediate surroundings. The everyday bordering that happens at the street level in Manshiyya, then, is a kind of synechdoche for Israel-Palestine, aptly representing the history of ethnic and class relations in a mixed city (Rabinowitz and Monterescu 2008; Qaddumi 2013).10

2. The Grey City

Tel Aviv and Jaffa are inextricably linked,11 one emerging from and dominating the other (Rotbard 2005), like Israeli and Palestinian nationalisms (Khalidi 1997). The forcible linking of them by the municipality in 1950 into the city of Tel Aviv-Jaffa created what Michel de Certeau calls an “asyndeton” (de Certeau 1984, p. 101), an elision that uses the hyphen as a placeholder for a shared experience of rupture. As an asyndeton of fragmentation, ruin and rebuilding in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Manshiyya today “retains only selected parts of it that amount almost to relics.” (de Certeau 1984, p. 101). While the border between the two cities is invisible and largely undefined for the Israelis who can move freely and acquire property on either side of it, Manshiyya is a sort of allegory for the fate of two national projects that want different things on the same piece of land. Yet, since there is no official indication of entering or leaving either one,12 the urban border of Tel Aviv-Jaffa is established entirely at the phenomenological level.

The sounds of the Arabic language, of the absence of the call to prayer, and of Sephardi liturgy (nusach) all play a role in the negotiations of otherness that render this border neighbourhood valuable and controversial. The relentless momentum of gentrification in Jaffa could well render both the Zionist and Palestinian claims on Manshiyya obsolete, but the importance of Arabness as a symbolic currency and rouser of political emotions remains. Among the Palestinian residents of what is effectively a reconstituted city, the intensity of sense memory, and the themes of unrequited love and ruin, take on national-allegorical dimensions. They act as a poignant reminder of what Ziad Fahmy calls the “lived public culture” (Fahmy 2020, p. 4) that the Palestinian people lost in the last century.

Even notwithstanding its complicated relationship with Jaffa, Tel Aviv’s circumstances are curious. Israelis tend to label it secular and liberal, whereas the polarised debate over national borders from the academy increasingly describes it as a colonial city that upholds a settler-colonial regime through its embrace of European culture.13 This political discourse often describes it as a city built on the ruins of Palestinian villages, which is factually incomplete but contains some truth (see Levine 2005).14 Meanwhile, the literature from the Israeli school of critical geography debates the city’s urban development street by street, differentiating that which was built as part of Jaffa in 1887 from that which was built a hundred metres away in 1910, or two hundred metres from there as part of Tel Aviv in 1925. Shimon, tour guide-historian, describes succinctly that this was not an overnight seizure but a gradual build-up:

“Tel Aviv was established in 1909. Jaffa is a five thousand-year-old city. Jews lived in Jaffa until the nineteenth century with Arabs. In 1887, some Jews who found it difficult to live among the Arabs, created a separate neighbourhood for Jews…In Jaffa. So they established a neighbourhood for Jews in Jaffa and that’s Neve Tzedek.15 Secular. Not religious. And three years later, they established another neighbourhood that was religious that was called Neve Shalom. Neve Tzedek and Neve Shalom were part of Jaffa, and they broke off to Tel Aviv in 1924. In the 20s, very rich families came from Greece, they bought land (karka) in north Jaffa, that was Jaffa. The head of the family was called Florentin so they called it Florentin. Florentin joined Tel Aviv in 1948. So that was a Greek neighbourhood, and gradually from the 40s, people came who were Persian, Algerian, Moroccan, and they settled in the industrial area and set up a market (shuk)—a Persian shuk—and today that’s shuk Levinsky.”(Interview, February 2018, Tel Aviv)

This narrative describes an organic inflow of Jewish migration, and it leaves out the details of the zone being completely emptied of Palestinians (“Arabs” as they were called then or continue to be called by Israelis today) and never quite rebuilt. Nor does he mention that it is extremely likely that it will be rebuilt in part or entirety over the next decade amidst the expansion of Tel Aviv’s property bubble. When it is eventually rebuilt, it will be rebuilt as Tel Aviv, the only part of 1947’s Jaffa to be called Tel Aviv, and little will remain of the Arab neighbourhood from before the state. Every person I interviewed reminds me that the Hassan Bek mosque remains, although it is forbidden from broadcasting the call to prayer. Yet, it is striking that so many of the characters who have clashed over urban space in Tel Aviv-Jaffa historically (Palestinians, Jews, and Israelis) were Arabic-speakers who shared elements of a common culture, whether Palestinian, or Mizrahi or newer arrivals with roots in north Africa who present as European (see Belkind 2020 for more on collaborative projects in Jaffa). Each group wears the label “Arab” differently, and possesses an opposing attitude towards the state and history, but each brings the pain of displacement and erasure. What I found in interviews with the different kinds of people who inhabit this unusual border zone is that everyday sounds—what Ziad Fahmy calls Street Sounds—possess the affective power to trigger intense sense memory that reveals the slippage of ethnicity, identity and bordering on this invisible and unpoliced border.

The complex, perhaps even “predatory” relationship between Tel Aviv and Jaffa (Rotbard 2005) is covered in detail by a critical school of Israeli geographers. In a David Harvey—Sharon Zukin axis of “right to the city” literature (Harvey 2008; Zukin 2011) that is inspired by Lefebvre (1968) and de Certeau (1984), Israeli geographers and urbanism critics frame the urban space of Israel’s cities as part of a political battle over national identity, intra-ethnic strife, and ultimately, class cleansing. Oren Yiftachel and Haim Yacobi make clear that the treatment of Mizrahi Jews who were housed in council estates (shikunim) or development towns (arei pituakh) are victimised by a state that that sees them as a problem like the Bedouin or Palestinians (Yiftachel and Yacobi 2003; Yacobi 2009). Architect Sharon Rotbard directed this critique at Tel Aviv itself with his monumental White City, Black City (Rotbard 2005), which argues that the aesthetic modernism of Bauhaus Tel Aviv erases the agency of Jaffa as well as the poor Tel Aviv neighbourhoods such as Neve Sha’anan, Hatikvah, Shalma Road, and Shapira. Daniel Monterescu offers a parallel and targeted argument about Jaffa’s gentrification as bohemian but ideologically-driven encroachment on the last remaining Arab spaces (Monterescu 2015), what Nimrod Luz provocatively calls “topocide” (Luz 2008, p. 1041). A sonic and multi-sensory reading of Manshiyya offers testimony to the bi-lateral, although not necessarily symmetrical, process by which, even today, Palestine is erased from the city and Jews erased from Arab history.

3. The Hassan Bek Mosque

The Hassan Bek Mosque, sometimes called “the last mosque in Tel Aviv”,16 is among the most intriguing structures in Tel Aviv-Jaffa because the words one uses to describe its existence and location are relational. Today, few people would dispute that it is located in Tel Aviv, but prior to 1948 it was right in the centre of Manshiyya, which is to say Jaffa. Indeed, this is really the only section of Jaffa that is now considered to be Tel Aviv, and as the only remnant of Palestinian life there, it is unique. Passers-by who are not Palestinian—Israelis or tourists—often wonder whether it remains operational, since one never hears the call to prayer. It mainly enters Israeli consciousness when it is associated with a security threat, like after the Dolphinarium bombing in 2001,17 but for Palestinians, it serves as a poignant symbolic reminder of the capacity for stories of ruin, loss and erasure to be silenced.

The Hassan Bek Mosque was built in the last days of the Ottoman Empire (1914–1917), by the eponymous governor who wished to counterbalance the impact of Jewish building in the area (Luz 2008, p. 1039). Its existence is confusing to passers-by, and at key moments of urban unrest, it has been a focal point for potential destruction. Sociologist Nimrod Luz describes what happened to the mosque after the dramatic events of 1948 (2008): after the Irgun captured Manshiyya on 29 April 1948,18 and Jaffa surrendered on 13 May 1948,19 the mosque fell into disuse for some decades. A newly-formed Rabita (Jaffa-based committee) fought for it not to be torn down through the 1970s only to see the minaret collapse in 1983. After renovation, it resumed services as an active mosque, and eventually affiliated with the northern branch of the Islamic Movement.20 Local strife ensued following a major terrorist attack in 2001, when Jewish youths accused the mosque of offering shelter to the attackers. Additionally, crucially, it is not permitted to broadcast the call to prayer.21 For Palestinians in Jaffa and beyond, it serves as a living reminder of a fight not to be erased, while for many Jewish Israelis, it remains a landmark defining ongoing security challenges.

Today, the Hassan Bek Mosque hosts prayers five times a day despite a total absence of Muslims living within a mile of it. Theirs is the only active minaret to be found north of Eilat Street, and I was amazed from my first visit by the creative navigation of mobility required to keep the mosque active:

I approached just after the end of Asr, the afternoon prayers, and saw rows of taxis parked outside. The worshipers were all taxi drivers, coming in from all over the Tel Aviv region! I lurked outside for a minute until a driver talking on his phone waved me over. As I approached, I saw that he had an angular beard, and wore a ring with a symbol of crossed swords.22 I presumed some kind of Hamas affiliation. He addressed me politely in Hebrew, clearly aware that I must be a researcher. I told him that I am interested in the mosque, and he asked why. When I answered that I am researching Manshiyya, he told me I should go inside. It is as though Manshiyya is a shibboleth, a magic word: using it with local Palestinians is an efficient way of identifying oneself as accepting of alternative narratives of 1948, of acknowledging Palestinian expulsion. He tells me to approach the gate and ask for Mohammed. Minutes later, after navigating my way through a few different individuals named Mohammed, I was inside the mosque; in the men’s section, looking at photos of old Manshiyya that are labelled “the ethnic cleansing of Jaffa.” I had heard that Jews were not permitted inside, so I was hesitant when Mohammed told me to come in. I had brought a headscarf, but it was not quite enough, so he provided me with a long robe. Clutching the scarf with one hand and my camera with the other made for awkward manoeuvring, but Mohammed told me that I would be better off returning another day in any event. If I returned on Friday for noontime services, when there would be five or six hundred people, I would even find some women to talk to, too. (Field notes, 2018, Tel Aviv.)

I planned to return that Friday, but in the meanwhile, I had interviews lined up. I asked Erez, the member of a prominent Israeli family, about the mosque, and his narrative revealed a great deal of anxiety about how it came into existence:

“My family was worried that after the Ottomans joined the war, they would expel the Jews from Eretz Israel. The Ottoman governor didn’t really support the idea. How they managed (hitslikhu) to stay in Tel Aviv another few years, until the end of the war, there were food shortages, it was a difficult situation, and in 1917 as the British were approaching via Sinai in the direction of Eretz Israel, they came up with the idea—the Ottomans—to expel all the residents (toshvei) of Tel Aviv to the interior of the country, to Petach Tikvah, to the north of the country, to distance them from the British so that they wouldn’t make contact. My family was expelled during that period around the same time that they were seeking building materials (dorshim chomrei bniyah) for this mosque, Hassan Bek. It was during these most difficult years of the war, it was hard to get ahold of materials to build the mosque. What’s really interesting is there’s a picture in the American Library of Congress of gravestones from the Jewish cemetery that they took and put to use in the building of the mosque.”(Interview, February 2018, Tel Aviv)

One understands immediately the full impact of this statement—that the mosque was built with Jewish gravestones—and checking its veracity felt urgent. I found the photo on the Library of Congress website,23 and it is vague—there are stones that are perhaps gravestones, and perhaps Jewish, lying alongside the emerging structure. They do not resemble those found in Trumpeldor Cemetery half a mile away, though. I consulted with my colleague Yair Wallach, an expert in “urban text” (street names, inscriptions, and graffiti) from the same era in Jerusalem, who recommended consulting Parashat Khayai, the memoirs of Yosef Eliyahu Chelouche (1931). Chelouche did not mention this despite being quite critical of Hassan Bek, so one could not claim concrete evidence. Consulting the internet, I found links to this story that parallel stories of the “ethnic cleansing of Jaffa,” and I realised that the fact of the mosque’s existence is quite unsettling to some Israelis. This rumour of the gravestones, as a folk memory, renders the mosque inappropriate and illegitimate, as the nearby Etzel Museum is for Palestinians.24 In both cases, the fact of the building’s existence is an affront to locals or past locals.

When I did return to the mosque that Friday, I walked up to the gate and asked for Mohammed, who brought me a robe and escorted me inside again. I noted that the women I met spoke little Hebrew, which made for a striking contrast with the men who were all fluent. Inside, Mohammed introduced me to a young man named Ahmed, who declined my request to record our conversation (my first such experience in a decade of interviewing). I asked him why he thought the building survived the war in 1948 when the rest of the neighbourhood was destroyed, and he put his hands up to the sky.25 I smiled politely, so he said that surely I believe in God, too. I smiled again, and he asked, incredulous, whether I thought that we just come from dust and end in dust. I deployed a stock answer—that Jews and Muslims believe in the same God—and he was satisfied. However, his reference to the end of days intrigued me, so I asked him what he thought the end was like, and he answered something—now in Arabic—about fire. I read his answer, and his pressing me for an assertion of belief in God, as evidence of a Salafi worldview (adherence to originalism of text and law). I wanted to know more but sensed that I risked overstaying my welcome, and thanked him for his time, assuring him and his companions that I would return the following week.

A few days later, an Israeli colleague emailed to ask how my initial visits went. I replied that I was grateful to be allowed inside, but was uneasy that I did not have a full grasp of their ideology and expected they might lean Salafi. He replied briefly: “glad it went well. They are Salafis through and through.” It is unlikely that I would visit a Salafi mosque in London—it might feel unsafe. At the Hassan Bek Mosque, however, the mosque’s ideology conveys explicitly what it is resisting: the erasure of the memory of the neighbourhood prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. Their affiliation with an outlaw political organisation might not be defensible for Israeli researchers, but it is an explicit statement that they reject any attempt to censor a charged political ideology. As Maoz Azaryahu and Rachel Kook explain in their study of Palestinian street names in Israel: “Notwithstanding the terrorist connection, the commemoration of ‘Izz al-Din al-Qassam as the only ‘local’ Palestinian hero underlined Islamic resistance as an historically continuous tradition” (Azaryahu and Kook 2002 p. 208).26

From the perspective of an “existence is resistance” Palestinian political trope, this building refuses to be a ruin, and that makes it unique in this part of town. However, at the same time, what renders the mosque idiosyncratic as a tool of resistance is its silence, its inability to project itself beyond its own walls. The mosque plays an important sensory role in Manshiyya’s expression of disjuncture, as Abigail Wood argues about religious rite in the Old City of Jerusalem, “not through textual exegesis but rather through embodied experiences of disgust, focus or wonder, and reconfigured through unspoken practices of piety or through the heavy hand of acoustic force” (Wood 2014, p. 301). Tourists do not know that it is an active mosque because they never hear the call to prayer. This conveys how important sound is in the negotiation of power in space, and it reinforces the danger that sound poses to ideologies of separation. The mosque is there, but people outside its walls need not ever know that. It is part of Jaffa, but it can be Tel Aviv, too, if it does not intrude on the discourse of Tel Aviv as Jewish, Hebrew/Hebrewist, and secular. As a buffer between two warring national stories, Manshiyya negotiates the sensory experience of ruin visibly, but its silence renders it discursively invisible.

4. The Sea

Moving through Manshiyya and noting the intensity of sensory experience in a place that is so empty of landmarks,27 one notices that the sonic experience changes dramatically from one end of the neighbourhood to the other. From the southern (Jaffa) end, one is close enough to Old Jaffa’s iconic clock tower to hear church bells and the call to prayer, but at the northern end, the Hassan Bek mosque is forbidden to broadcast the call to prayer. On the western end, one reaches the sea, the Holy Land’s only uncontested border.28 The sensory difference between space designated as Muslim and space inhospitable to Muslims/Arabs is stark, and transpires primarily at the level of the sonic and sensory. So in interviews with Palestinians and Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews, tour guides and rabbis, I ask which local sounds stand out for them—not necessarily how they would characterise the local soundscape, but what sound for them equates with Tel Aviv-Jaffa. For Abu George, as for everyone else, the spectre of the Mediterranean Sea (yam tichon) has shaped this region throughout history, and indeed, it has a near-mystical impact on people. He says:

“The cleanest and most authentic sound I hear in Jaffa is the sound of the sea, and the clock at the churches, and the call to prayer (muezzin), although they can’t always play it. I feel for whoever doesn’t love the sea. You can feel it in your body—wow (khaval al hazman). The sea is positive energy. I’m crazy about the sea (ani met al hayam).”

This poetic formulation is rooted in the landscape. Abu George associates his urban surroundings not with the soundscape imported by people (as even the call the prayer is), but with topography and environment.29 For Palestinians, the primordial narrative of connectedness to nature is a major theme in claims to territory (see Khalidi 1997). One understands implicitly, though, that an Ashkenazi Israeli giving Abu George’s answer might sound orientalist. As a discourse like the others presented about this part of town, it works to compensate for the confiscation of Arab space and marginalisation of Arab sound by establishing one group’s superior rootedness.

Abu George notes that the sea has been Jaffa’s main topographical feature for thousands of years. As far back as the biblical references to it (which are not reliable as sources, but which convey useful knowledge about the city’s place in history), the sea, the port, and fish have been defining elements of the city strategically and culturally. Its coastal location is, according to Itamar Radai, a key reason why the Jaffa population was so easily dominated in April 1948, in contrast to Jerusalem’s mountainous landscape that made for easier mobilisation of guerrilla tactics (Radai 2016). While the beach no doubt constitutes an important element of Tel Aviv’s urban identity, lending itself to tourism, nightlife and gay culture, the urban discourse about Tel Aviv as a beach city makes a striking contrast with Jaffa as a port city on the sea.

The contrast is especially striking in defining the urban characters of Tel Aviv and Jaffa in the spaces by the sea in Manshiyya. The Clore beach, where families from Jaffa swim, or the Clore Park, where Arab families barbeque on weekends,30 are the spaces on the Tel Aviv side of the urban border where Palestinians (for the most part, Palestinian-Israelis) circulate more or less freely. The only part of Tel Aviv where Palestinians move in groups are the spaces by the sea (more or less), where couples take evening walks and young people sit on rocks listening to the waves. After speaking with Abu George, I began thinking about this difference: when people in TAJ (Tel Aviv-Jaffa) speak of the beach or the sea, how much do they mean one rather than the other? Their evaluation, and their choice of word (hof for beach, yam for sea), is based on their sensory perception. For the feeling of the sun on one’s back, they go to the beach, but to stare into the open abyss, they go to the sea. Either way, the crashing sound of the waves, the screams of seagulls, and the calls of vendors make up the sense memory of living by the sea.

The sea is central to Tel Aviv-Jaffa’s urban identity and to its economy (Azaryahu 2007, p. 192), and Manshiyya’s fate is tied to the function of the beach in daily life. The facts of why the neighbourhood was never rebuilt or repopulated, like in Haifa or Jerusalem,31 or indeed in Jaffa, are well known. As Shimon, tour guide-historian, explains:

“In the sixties, there was in Tel Aviv a head of the municipality, who built a lot of civic buildings, he was the biggest builder in Tel Aviv. He was called Yehoshua Rabinovitz.32 He came up with a plan to join up (lekhaber) Tel Aviv and Jaffa. Which is to say, ‘Tel Aviv breaks off from Jaffa at the neighbourhood of Manshiyya.’ What Rabinovitz did, he said ‘I’ll take Manshiyya, and I’ll turn it into Tel Aviv’s central business district.’33 They built hotels, and then in 1961/62/63/64, until the 70s, they begin to plan Manshiyya, and they built two hotels and office buildings, everything that’s there now. And then in 1973 was the Yom Kippur War, and Rabinovitz lost the election, and Chich became the mayor.34 And what did he say? ‘I don’t want to build up Manshiyya, because it will cut Tel Aviv off from the beach.’ And he moved the business district to the Ayalon—to Azrieli.”(Interview, February 2018, Tel Aviv)

We can discern in this narrative the echoes of Le Corbusier’s high-modernist plans for urban design, as described by James Scott (1998, p. 104). Tel Aviv’s urban design is based primarily on the principle of tabula rasa, or what Simon Webster describes in the case of Abu Dhabi: that “high modernism facilitated the political goals of legibility and control” (Webster 2015, p. 140). Yet, even the creation of something from nothing, the common narrative of the construction of Tel Aviv, is anchored in and faithful to access to the sea.

In de Certeau’s formulation, the tactic of walking the city and feeling the presence of the sea is key to knowing and reading the city: “To plan a city is both to think the very plurality of the real and to make that way of thinking the plural effective; it is to know how to articulate and be able to do it” (de Certeau 1984, p. 94, italics his). For Tel Aviv, the beach is a defining feature—the boardwalk, the cafes, and the hotels turn the coastline into an economy for leisure and tourism, one that Palestinian citizens of Israel use extensively. It is easy to walk through Charles Clore Park and forget that the houses’ foundations once lay just beneath the landscaped park. Additionally, in that respect, the microcosmic element of Manshiyya’s history emerges against a backdrop of war, statehood and rights. The sea is not considered to be a space of danger like it is in Gaza or across the Mediterranean for people traversing the sea, but it is, for Palestinians, a space for working through the historical weight of war and empire. The sound of the crash of waves on the rocks and the screeching of seagulls might be a widespread code for leisure and contemplation, but, in this space, it is also a site for navigating a dialectic of aesthetics and economics, and of history and belonging.

5. The Concert

While tangible ruins weigh especially on the Palestinian residents of Jaffa, the allegorical ruins, the ruins of the heart as conveyed by Umm Kulthum, weigh equally heavily for Mizrahi Jews who severed ties to their countries of birth to join a society that for decades denigrated them. As I asked my research consultants about Manshiyya, they often mentioned Umm Kulthum, with people in Jaffa especially mentioning that she visited in the 1930s. They said it in a number of different ways, sometimes getting the date or venue wrong, and often dropping it into a description of the soundscape in a haphazard way. Bringing her up seems to be a signpost for connoisseurship and expertise, and in the context of the situation on the ground in Tel Aviv and Jaffa, talking about it feels intimate and urgent, as though my research consultants are themselves grappling with the thinness of the border.

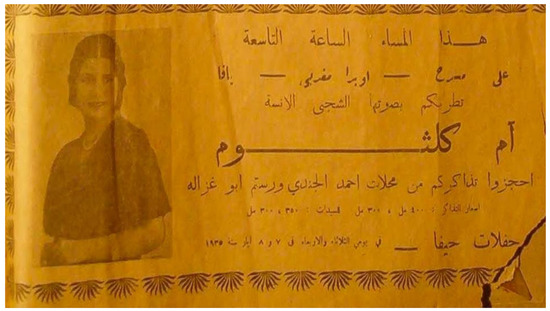

I collected idiosyncratic material about Umm Kulthum, encountering listening practices that were often intense. Yet, the details of her concert were difficult to pin down, with only fleeting information on the internet in English, often with errors about date or location. The Arab media was more helpful:35 the London-based newspaper Al Hayat reports that the concert took place in early May 1935 at the Moroccan Opera Theater on Allenby, known in Israel as the Mugrabi, and that women paid less than men for tickets (see Figure 3). Al Hayat found the announcement in the personal library of Jerusalem memoirist Wasif Jawhariyyeh.36

Figure 3.

Advert for Umm Kulthum concert in Jaffa 1935. From the personal library of Wasif Jawhariyyeh.

Those same archives indicate that Umm Kulthum’s contemporaries and competitors Mohamed Abdel Wahab and Farid al-Atrash often started their tours in Jaffa, too. The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs has an article in Arabic that claims an additional (previous) October 1931 performance. That same article makes a point to claim that former Sephardi chief rabbi Ovadiah Yosef, an Arabic-speaker who was born in Baghdad, was a fan.37

From the work of Virginia Danielson (1997), we know a lot about Umm Kulthum’s concerts, especially in her late period of 1967–1975 (see also Lohman 2010). Her Thursday night concerts were national events in Egypt, with the whole nation huddling around the radio to listen. She often chose her repertoire at the last minute, even taking requests from the audience, requiring flexibility and close listening of her male ensemble (Danielson 1997). She would choose maybe three pieces, spending an hour on each, stretching out “al-Atlal” or “Alf Leila WaLeila” through repetition and improvisation. In her final years, sometimes the concert would go on for six hours instead of three, and sometimes she would sing two pieces instead of three, or even just one on occasion. Audience participation was crucial in facilitation of musical ecstasy (tarab). This signature style is described in poignant detail in the literature, yet it refers to the performances late in life by an established virtuoso. How well developed was the style in 1935? Was she recognised by the locals as a singular figure? None of this is captured in the above documents.

Perhaps the concert was not the momentous event in 1935 that it is now in my research consultants’ descriptions. However, just as they mention gentrification and brothels with a remarkable frequency that reveals unease, one must also consider the dynamics of discomfort over this concert. Indeed, each of these media portrayals has an agenda, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs not least of all. Some are almost comically prejudicial: the Al Hayat article laments the existence of the Umm Kulthum café in Jaffa; following Laura Lohman’s description of the phenomenon of Umm Kulthum cafés worldwide (Lohman 2010, p. 163), Al-Hayat disapproves of any imagined connection between Umm Kulthum as belonging to Israeli culture.

The most awkward fact about the concert is its location: a thirteen-minute walk from the Hassan Bek Mosque if we walk up the unfortunately-named Hakovshim (“the conquerors”), it was held at a theatre on Allenby Street, which is most definitely Tel Aviv rather than Jaffa. It took place before the 1936 uprising, so it would be anachronistic to retroactively ascribe her solidarity for Palestinian nationhood, but it is fair to say that this is a historical detail that feels uncomfortable, because it means that the audience was not entirely Arab. Additionally, Umm Kulthum’s importance today to Mizrahi Jews cannot be overstated.

Amy Horowitz (2010), Regev and Seroussi (2004), and Galit Saada-Ophir (2006) vividly describe the taboo for Mizrahi immigrants in the 1950s and 1960s of continuing to embrace Arab culture after fleeing Arab regimes. Decades on from their arrival, Mizrahi music is a core anchor of Israeli pop music, with Eyal Golan and Sarit Hadad consistently topping the mainstream charts. Lebanese pop music, Egyptian hip hop, Andalusian music, and the oud tradition of Baghdad are all alive and well in a place that most Arab musicians cannot or will not visit on a tour (Belkind 2020; McDonald 2013). Indeed, Umm Kulthum’s best-known tour, more than thirty years after the show at the Mugrabi, raised money for the Palestinian cause following the 1967 war. However, today, young and old Hebrew-speakers look to Umm Kulthum as the pinnacle of Arabic singing, and they are as likely to use her original source material in teaching maqam as they are to remix it for drag night (see Monterescu 2015, p. 274). Laura Lohman writes eloquently in her book about Zehava Ben’s imagining of a shared heritage, and of Sapho singing “Inta Omri” as a peace song during the Oslo years. These portrayals can generally be considered as part of a left-wing attempt to champion Arab culture in a state that often directly devalues it. Yet, the assumption that listening to Umm Kulthum with love is a strictly left-wing endeavour ignores the political reality that many Mizrahi Jews continue to love Arab culture even as they vote for right-wing parties. Everyone carries the weight of history differently on this amorphous border.

My friend Dr. Moshe Morad sometimes mentions that his father, Emil Morad, would say that in the 1950s, they (immigrants from Iraq) would listen to Umm Kulthum “with the windows closed.” This evocative metaphor portrays the binary (Jew/Arab) that Mizrahi populations defy. Music making is full of conflicted binaries, and the twentieth century is full of cases of Jewish musicians from Muslim lands—the Al-Kuwaiti brothers, or Layla Murad—who contributed hugely to a national (Arab) culture and eventually emigrated or converted in the moment of conflict between Zionism and postcolonialism (see Seroussi 2014; Wenz 2020). The mutual processes of erasure that remain ongoing across Israel and the Arab world—that is, Israeli erasure of Palestinian culture, and pan-Arab erasure of Jewish history (apart from Morocco, perhaps)—remain the backdrop against which Mizrahi Jews listen to Umm Kulthum. Yet, in the stories in circulation about her concert, well before Manshiyya’s destruction, the stickiness of definitions and borders stands out. The location of her concert may be a well-established fact, and objecting to describing it accurately might be anachronistic, but the circulation of stories about the concert today reveals a sense of ambivalence over the bordering of Arab and Jewish culture that happens at the street level in everyday life in Manshiyya.

6. Conclusions

These three modes of sonic intensity—the sea, the mosque and the concert—are experienced in different ways by the diverse groups of people who navigate this frontier neighbourhood. The aesthetic of ruin and rebuilding manifests itself in additional ways today, and that might include sensoria of cranes and drills, perhaps a reminder of the 1950s. With a housing bubble driving the working-class to the suburbs, and affluent immigrants settling in Tel Aviv, the will to use empty space to build housing is slowly transforming the social dynamics of southern Tel Aviv. Yet, this cluster of neighbourhoods has been through this process repeatedly over the past century. Tomer Chelouche, great-great-grandson of Aharon Chelouche, explains that his family remained in Neve Tzedek “with difficulty” (bekoshi) through the twentieth century, and he describes the early years of the state like this:

“There was a process where a lot of people came and it was chaos (balagan). The State of Israel more than doubled itself (yoter mehichpila et atsma) in the first couple of years of the state. And just a few years after that were a million and a half people. A lot of times people just came into empty houses and started to live in them.”(Interview, February 2018, Tel Aviv)

Thinking about the disjuncture between Tel Aviv’s Arabic-speaking population and its aesthetic modernism, European tastes, and class cleansing, one can discern a process of asserting cultural capital as an equal partner to economic capital. Evidence is apparent on the streets of Tel Aviv, on avenues such as King George and Nahalat Binyamin, which were always gritty and unattractive, and are “cleaning up” rapidly. The whole white city is becoming whiter even as the black city becomes blacker (see Hankins 2013), with urban geographers such as Sharon Rotbard arguing from an architectural perspective that the image of a UNESCO-approved White City overshadows (literally) a gritty and deprived under-city of Jaffa and its surrounding neighbourhoods. As residents who remember 1948 age, and people who have lived through decades of a neighbourhood in flux, it seems that the struggle between two national projects might, at the street level, give way to a fight between working-class residents and upper-class immigrants. This process of swapping an aesthetically or politically undesirable population for a more prestigious one is, as Ziad Fahmy demonstrates in the case of Cairo, a class struggle as much as a national project (Fahmy 2020).

The spaces that constitute Manshiyya bear the fault lines of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and of a right-to-the-city class struggle that centres around different shades of inclusion in Arab culture. The mosque that cannot project, the stories traded about a legendary concert, and the call of the sea trade in a dialogue over the pain of erasure shared by the groups who have inhabited the neighbourhood over the last century. The Palestinian exile/expulsion remains an open wound for Palestinians, while Mizrahi Jews have been marginalised both by their countries of origin and by a state that for decades did not see them as citizens of value. These groups live alongside one another as neighbours, but more often consider the others interlopers who supplanted one group’s right to the city.

The direct line that can be drawn, through Arab locals, to working-class new immigrants who are eager to become Israeli, to culturally European immigrants who have thoroughly erased many signs of their own Arabness, mirrors the urban process through which Tel Aviv has whitened over the past two decades. What is happening in Manshiyya—the replacement of undesirable residents (Palestinians) with semi-desirable citizens (Mizrahim) and more recently with desirable citizens who were actively recruited (French immigrants)—melds a national project of Zionism with the aesthetic project of urban development. The barren cityscape and its thoroughly Arab soundscape illustrate how citizens across a spectrum of Arabness navigate the sensory disjuncture of being Arab in the “Hebrew city.” Whether listening to Umm Kulthum in secret, passing the mosque and wondering why it does not seem operational, or listening to the sea, the street-level experience of Manshiyya triggers intense feelings of exclusion and erasure for Mizrahi and Palestinian citizens.

Tomer Chelouche, the Tel Aviv-born great-great-grandson of Aharon Chelouche, the Algerian-born founder of Neve Tzedek, does not think of the heavy weight of history the same way. “Manshiyya,” he says “only matters today to academics.” Everyone else is just trying to make life work on either side of a paper border. As a parting question, I ask Tomer whether any of Chelouche’s six hundred descendants live in the neighbourhood now. “No way,” he says, “who can afford it?” What better illustration of the immortal line from al-Atlal: “know that if a wound begins to recover, another wound crops up with the memory, so learn to forget and learn to erase it.”

Funding

This research was funded by Seed Corn Funding, SOAS University of London.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of SOAS University of London (2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Much is made of the hyphen, and Manshiyya is the physical/geographical hyphen. Barbara Mann calls the hyphen “that seam which both distinguishes and links them” (Mann 2015, p. 91). |

| 2 | Sephardi is the term for Jews with Spanish ancestry. Following the expulsion in 1492, they dispersed, mainly across the Ottoman Empire (and to Amsterdam), so many Jews from north Africa, Turkey and Greece, and as far as Aleppo identify as Sephardi according to their religious rite. Mizrahi (“Oriental”) is a more generic term in Israel for the Jewish of Muslim lands. |

| 3 | The Palestinian citizens of Israel, numbering well over a million, are referred to by different names. Many call themselves Palestinians of 1948 Palestine, or ‘48 Palestinians, and they are occasionally referred to as Palestinian-Israelis. Israelis often call them Israeli Arabs (or just aravim in Hebrew). When I refer to this group, I am sometimes referring to their status before the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, and particularly when discussing them as Arab citizens of the Ottoman Empire, Palestinian is perhaps an anachronistic term. For clarity, I sometimes refer to the group of Palestinian residents of Manshiyya and Jaffa as “Arab,” with full acknowledgement that some Jews label themselves as ethnically Arab, too. |

| 4 | There is a strand of scholarship in Middle East Studies that argues that the Jews of Arab lands have always felt Arab, and that Zionism upended a peaceful existence in the Arab world. Abigail Jacobson and Moshe Naor engage this debate with sensitivity (Jacobson and Naor 2016) through an exploration of daily interactions between neighbours. I will not delve too deeply into these debates except to say that the concept of Arabness is defined in any number of ways by readers. |

| 5 | The Hinnawi family is a prominent Christian family from Jaffa known as butchers and wine merchants. My Hebrew-speaking research consultants mention them, too, as important figures in the life of Jaffa, and Deborah Bernstein explains that they owned Café Lorentz on Shabazi Street (Bernstein 2012, p. 123). |

| 6 | The Absentees’ Property Law of 1950 gave the State of Israel stewardship over the property of Arab refugees. The State took license quickly to renovate property and transform it into housing for new Jewish immigrants (see Tamari and Hammami 1998). |

| 7 | Yosef Eliyahu Chelouche was a founder of Tel Aviv, having grown up in a prominent north African family in the new suburbs of Jaffa. His father, Aharon Chelouche, is known as the founder of Neve Tzedek. He (Yosef Eliyahu) was a memoirist of life in Mandate Palestine and was critical of the Ottoman Empire in its last days of administration in Palestine. |

| 8 | Neve Tzedek was the Jewish neighbourhood next to Manshiyya. It was founded in 1887 by Aharon Chelouche, and it was populated by Jews of different backgrounds. Today it is the centre for the French gentrification of south Tel Aviv. All of the neighbourhoods on the Tel Aviv-Jaffa border, including Manshiyya, Neve Tzedek, Florentin and Kerem Hateimanim are referred to in the literature as “frontier neighbourhoods” (Jacobson and Naor 2016). |

| 9 | The synagogue was, until 2014, Iraqi, and like many Sephardi/Mizrahi synagogues in south Tel Aviv, on the decline. |

| 10 | A total of 9% of Palestinians in Israel live in mixed cities (Qaddumi 2013, p. 9). |

| 11 | In three different interviews, they are described as joined-up cities, cities that the municipalities attempted to join together (lekhaber). |

| 12 | Most literature about Palestine describes the disciplining state as an omnipresence in Palestinian lives, through a system of checkpoints and walls (see Belkind 2020 or McDonald 2013 for how that impacts music making). Since Jaffa is part of Israel, there is no such border, and yet Palestinians do not generally circulate in groups in Tel Aviv (apart from the beach). This particular urban border is established discursively and almost entirely self-policed. |

| 13 | A claim made by the Boycott, Divest and Sanctions (BDS) movement that has gained momentum on university campuses in the diaspora. |

| 14 | While much of the land in the historic Ahuzat Bayit district (Tel Aviv’s first official neighbourhood) was purchased legally, other neighbourhoods, such as Salama, were Palestinian villages that were depopulated after 1948. Noam Leshem (2017) goes into brilliant detail. |

| 15 | In everyday life, the border between Neve Tzedek and Manshiyya was undefined, too, and they are often considered under the same narrative of the frontier neighbourhoods. |

| 16 | With a major wave of labour migration to Tel Aviv over the past three decades, there are plenty of unofficial “underground” mosques in Tel Aviv’s poorer neighbourhoods, in addition to Pentecostal Churches (see Hankins 2013). Migrant workers from Southeast Asia and asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa make up a substantial portion of south Tel Aviv’s Shapira and Neve Sha’anan neighbourhoods. |

| 17 | The bombing of the nightclub in June 2001 occurred metres away from the mosque and claimed twenty-one victims, mostly young Israelis from the former Soviet Union. Hamas claimed responsibility for it. |

| 18 | The Battle for Jaffa took several stages, but concluded just as the 1948 War was getting underway. Manshiyya was captured several weeks prior to the fall of Jaffa, and the two Zionist factions (Irgun and Haganah) vied for dominance. |

| 19 | Haim Lazar’s book (Lazar 1961) is extremely detailed and widely cited despite preceding the new school of Israeli historiography by several decades. |

| 20 | The northern branch was ruled illegal in 2015, and its leader Raed Salah is serving a two-year sentence in an Israeli prison. The northern branch headquarters is in Umm al-Fahm, a major centre for ’48 Palestinian life. |

| 21 | In the last Knesset session, the “muezzin bill” made its way through parliament, proposing to limit “noise pollution” between 11pm and 7am. It is widely considered to target mosques more than any other kind of urban noise. |

| 22 | These are indicators of support for the Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots, such as Hamas, and of stringent Salafist theological readings. The two do not necessarily go hand in hand across the Arab world, but the northern branch draws spiritually from the Islamism of the Muslim Brotherhood, and therefore with an activist (as opposed to quietist or Jihadist) strand of Salafism, reflected in their boycotting of Israeli elections. |

| 23 | <https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.13709/?sp=231> (accessed on 30 August 2021). |

| 24 | The Etzel Museum is located in a ruined house on the Manshiyya shore that has been renovated as a museum commemorating the Irgun’s achievements in the Battle of Jaffa. One needs to show identity documents to Israeli military personnel to enter. Sharon Rotbard critiques it at length in White City, Black City as an example of an axis of aesthetic and ideological warfare over the residents of Jaffa (Rotbard 2005). |

| 25 | Charles Hirschkind’s work on the way that bodily gesture constitutes moral entrainment (Hirschkind 2006) has set the standard for ethnographic work on Islamic practice. |

| 26 | The Arab town in Israel of Umm al-Fahm (population: 38,000) voted for the Islamic movement in 1988. Local government subsequently changed street names to reflect Arab history accordingly (Azaryahu and Kook 2002, p. 206): sixty-five streets were re-named, sixty-three of them after early figures in Islamic history, especially from Spain. |

| 27 | Naming streets is not a universal practice in the Arab world, and Yair Wallach’s chapter on naming in Jerusalem in the 1920s demonstrates the way that ideology and language are used to transform space into text (Wallach 2020, pp. 135–38). According to Maoz Azaryahu and Rachel Kook, only seven streets in Jaffa had names before 1948 (Azaryahu and Kook 2002, p. 197). This assertion is contradicted, however, by the Zochrot report that gives names to the streets by the train station, the mosque, etc. (Zochrot: 11). |

| 28 | Maps of Israel-Palestine are controversial, with the more hard-line ideological factions agreeing on borders but disagreeing on names for the ruling nation-state. How to fit a potential two-state solution, bi-national state, the Golan Heights, and so forth onto a map is politically challenging. The only absolute border is the sea to the west. For that matter, disputes over fishing with Gaza and gas fields with Lebanon render the sea controversial, too, but the sea is consensually defined as the western border for Israel-Palestine. |

| 29 | It is nevertheless interesting that he equates the call to prayer with the sea, and in the language of the scholarship of nationalism, it assimilates the call to prayer into the landscape. |

| 30 | One interviewee characterised this as an Arab activity, noting, “They do barbeques (al ha’esh), Jews don’t do barbeques.” |

| 31 | Repopulated by new Jewish immigrants or by returning Arabs after the war was over. |

| 32 | The former Labour Minister was deputy mayor from 1959–1969 and mayor 1969–1974. |

| 33 | The plan was to call the area “Ahuzat hahof” (Zochrot: 6). |

| 34 | Shlomo Lahat was (Likud) mayor 1974–1993. |

| 35 | Thanks to Dr. Clara Wenz for helping me to source material in Arabic. |

| 36 | <https://www.almodon.com/culture/2017/11/25/%D8%A3%D9%85-%D9%83%D9%84%D8%AB%D9%88%D9%85-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B1%D8%AD%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%87%D8%A7-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%88%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%A5%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%A7%D9%85> (accessed on 30 August 2021). <https://www.alaraby.co.uk/%D8%AD%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%BA%D9%86%D8%AA-%D8%A3%D9%85-%D9%83%D9%84%D8%AB%D9%88%D9%85-%D9%88%D9%81%D9%8A%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%B2-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%AF%D8%B3> (accessed on 30 August 2021). Wasif Jawhariyeh was a prominent Jerusalem-based memoirist and musician. His memoirs offer rich detail about everyday life in mandate Palestine (Tamari and Nassar 2014). |

| 37 | <https://mfa.gov.il/MFAAR/IsraelExperience/ArtCultureAndSport/Pages/Um-Kul-Thum-returns-to-Jaffa.aspx> (accessed on 30 August 2021). Ovadia Yosef was born in Baghdad and served as the Chief Sephardi rabbi in Israel from 1973–1983. He was highly revered as a jurist (posek) of Jewish law, and retained immense influence over Mizrahi Jewish life well into his retirement. |

References

- Aleksandrowicz, Or. 2013. Paper Boundaries: The Erased History of the Neighborhood of Neveh Shalom. Teorya U-Vikoret (Theory and Criticism) 41: 165–97. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, Marc. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azaryahu, Maoz. 2007. Tel Aviv: Mythography of a City. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azaryahu, Maoz, and Rebecca Kook. 2002. Mapping the Nation: Street Names and Arab-Palestinian Identity: Three Case Studies. Nations and Nationalism 8: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkind, Nili. 2020. Music in Conflict: Palestine, Israel and the Politics of Aesthetic Production. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Deborah. 2012. South of Tel Aviv and North of Jaffa: The Frontier Zone of ‘In Between’. In Tel Aviv, the First Century: Visions, Designs, Actualities. Edited by Maoz Azaryahu and Selwyn Ilan Troen. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 115–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chelouche, Yosef Eliyahu. 1931. Parashat Hayai. Tel Aviv: Babel Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson, Virginia. 1997. The Voice of Egypt”: Umm Kulthum, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erez, Oded. 2018. Music, Ethnicity, and Class between Salonica and Tel Aviv-Jaffa, or How We Got Salomonico. Journal of Levantine Studies 8: 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, Ziad. 2020. Street Sounds: Listening to Everday Life in Modern Egypt. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Golan, Arnon. 1995. The Demarcation of Tel Aviv-Jaffa’s Municipal Boundaries Following the 1948 Wars: Political Conflicts and Spatial Outcome. Planning Perspectives 10: 383–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankins, Sarah. 2013. Multidimensional Israeliness and Tel Aviv’s Tachanah Merkazit: Hearing Culture in a Polyphonic Transit Hub. City and Society 25: 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2008. The Right to the City. New Left Review II: 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschkind, Charles. 2006. The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, Amy. 2008. Re-routing roots: Zehava Ben’s journey between shuk and suk. In The Art of Being Jewish in Modern Times. Edited by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jonathan Karp. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 129–43. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, Amy. 2010. Mediterranean Israeli Music and the Politics of the Aesthetic. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, Abigail, and Moshe Naor. 2017. Oriental Neighbors: Middle Eastern Jews and Arabs in Mandatory Palestine. Waltham: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kadman, Noga. 2015. Erased from Space and Consciousness: Israel and the Depopulated Palestinian Villages of 1948. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khalidi, Walid. 1992. All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington, DC: The Institute for Palestine Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Khalidi, Rashid. 1997. Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kun, Josh. 2000. The Aural Border. Theatre Journal 52: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, Haim. 1961. The Conquest of Jaffa. Shelah: Tel Aviv. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1968. Writings on Cities. Translated by Eleonore Kofman, and Elizabeth Lebas. London: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Leshem, Noam. 2017. Life After Ruin: The Struggles over Israel’s Depopulated Arab Spaces. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Mark. 2005. Overthrowing Geography: Jaffa, Tel Aviv, and the Struggle for Palestine, 1880-1948. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lohman, Laura. 2010. Umm Kulthum: Artistic Agency and the Shaping of an Arab Legend, 1967–2007. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luz, Nimrod. 2008. The Politics of Sacred Places: Palestinian Identity, Collective Memory, and Resistance in the Hassan Bek Mosque Conflict. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26: 1036–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mann, Barbara E. 2015. An Apartment to Remember: Palestinian Memory in the Israeli Landscape. History and Memory 27: 83–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, David. 2013. My Voice is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Monterescu, Daniel. 2015. Jaffa Shared and Shattered: Contrived Coexistence in Israel/Palestine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qaddumi, Dena. 2013. Advancing the Struggle for Urban Justice to the Assertion of Substantive Citizenship: Challenging Ethnocracy in Tel Aviv-Jaffa. DPU Working Paper No. 150. London: UCL Development Planning Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, Dan, and Daniel Monterescu. 2008. Reconfiguring the ‘Mixed Town’: Urban Transformations of Ethnonational Relations in Palestine and Israel. International Journal of Middle East Studies 40: 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radai, Itamar. 2016. Palestinians in Jerusalem and Jaffa, 1948: A Tale of Two Cities. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Regev, Motti, and Edwin Seroussi. 2004. Popular Music and National Culture in Israel. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rotbard, Sharon. 2005. Ir Levana Ir Sh’chora (White City, Black City: Architecture and War in Tel Aviv and Jaffa). London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saada-Ophir, Galit. 2006. Borderland Pop: Arab Jewish Musicians and the Politics of Performance. Cultural Anthropology 21: 205–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Himan Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seroussi, Edwin. 2014. Nostalgic Zionist Soundscapes: The Future of the Israeli Nation’s Sonic Past. Israel Studies 19: 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamari, Salim, and Rema Hammami. 1998. Virtual Returns to Jaffa. Journal of Palestine Studies 27: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamari, Salim, and Issam Nassar, eds. 2014. The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904–1948. Northampton: Olive Branch Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, Yair. 2020. A City in Fragments: Urban Text in Modern Jerusalem. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Simon J. 2015. Reflexive City: Space and Imaginaries in Abu Dhabi. Ph.D. dissertation, London School of Economics, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wenz, Clara. 2020. Yom Yom Odeh: Towards the Biography of a Hebrew Baidaphon Record. Yuval: Studies of the Jewish Music Research Centre XI: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Abigail. 2014. Soundscapes of Pilgrimage: European and American Christians in Jerusalem’s Old City. Ethnomusicology Forum 23: 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacobi, Haim. 2009. The Jewish-Arab City: Spatio-politics in a Mixed Community. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yiftachel, Oren, and Haim Yacobi. 2003. Urban Ethnocracy: Ethnicity and the Production of Space in an Israeli ‘Mixed City’. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21: 673–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zochrot. 2010. Remembering al-Manshiyya-Jaffa (in Hebrew and Arabic). Available online: www.zochrot.org (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Zukin, Sharon. 2011. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).