Abstract

Pilgrims’ badges often depicted works of art located at a cult center, and these cheap, small images frequently imitated monumental works. Was this relationship ever reversed? In late medieval Hamburg, a painted altarpiece from a Hanseatic guild narrates the life of Thomas Becket in four scenes, two of which survive. In 1932, Tancred Borenius declared this altarpiece to be the first monumental expression of Becket’s narrative in northern Germany. Since then, little scholarship has investigated the links between this work and the Becket cult elsewhere. With so much visual art from the medieval period lost, it is impossible to trace the transmission of imagery with any certainty. Nevertheless, this discussion considers badges as a means of disseminating imagery for subsequent copying. This altarpiece and the pilgrims’ badges that it closely resembles may provide an example of a major work of art borrowing a composition from an inexpensive pilgrim’s badge and of the monumental imitating the miniature.

1. Introduction

Pilgrims’ signs, the small badges and ampullae made from inexpensive materials for purchase by the pilgrims who visited the medieval shrines of saints, recalled the pilgrimage destinations in multiple ways (Rasmussen 2021). The relationships between pilgrims’ signs and monumental works of art have been studied since the nineteenth century when the academic study of pilgrimage souvenirs began. Initially, the question was whether pilgrims’ souvenirs could help art historians reconstruct lost works of art from pilgrimage centers, such as apse mosaics (Smirnov 1887; Ainalov [1901] 1961, pp. 230–50). The recognition that small items sold to pilgrims often imitated monumental work is still important in scholarship today, although it is widely understood now that small-scale works are also shaped by concerns particular to their own medium and that references to large-scale works are likely to be selective, inexact, and intentional (Slocum 2018, p. 120; Weitzmann 1974; Grabar 1958; Vikan 1995). Key elements of larger works might be chosen for the badges and ampullae intended to be carried away by visiting pilgrims. For instance, tin and lead pilgrims’ badges record, schematically, the appearances of statues, such as that of the Virgin and Child at Walsingham, or architectural settings, such as the tripartite façade of Magdeburg Cathedral, as noted by Ann Marie Rasmussen in discussion at a recent conference in May 2021. The form of the lost reliquary bust of Thomas Becket can be deduced from the pilgrims’ badges that represent it (Splarn 2021) and many elements of Becket’s great tomb-shrine are recalled by badges, but with the probable addition of an effigy that allowed the badge to identify Saint Thomas in contexts away from Canterbury (Blick 2005). Pilgrims’ badges used in concert with other forms of evidence both archaeological and textual allow reconstructions not merely of discrete objects but of multisensory pilgrimage experiences (Jenkins 2020). What has not been considered is that while pilgrims’ badge images could derive from monumental art, they might also have played a role in composing it. The altarpiece of St. Thomas Becket now in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg may offer an example of a monumental commission that took some of its formal inspiration from a small pilgrim’s badge.

2. The Feast of the Regressio

The shrine of Thomas Becket at Canterbury was one of the most popular pilgrims’ destinations in late medieval Europe. Among European shrines, it ranked third in importance after Rome and Compostela and was more accessible than either to residents of Northern Europe, being easily reached from the ports of Southeast England and a couple days’ ride from London. In 1220, St. Thomas’s corporeal remains were translated into a lavish shrine and chapel in the east end of Canterbury Cathedral, which had been designed to accommodate pilgrims and to celebrate the saint in the most artistically rich setting in Europe (Duggan 2016; Binski 2004). Saint Thomas Becket appealed to a wide range of devotees from all social ranks, and whose interest in the saint ranged from the personal to the political. He was honored not only at Canterbury but at sites throughout Europe, and in some locations, he was celebrated by multiple feasts in the liturgical year. By the fifteenth century, Thomas Becket was firmly established as an international saint.

The most celebrated feast of Saint Thomas Becket was December 29, the date of his assassination in 1170. This is the feast established at least as early as 1173 when Pope Alexander III made Becket’s canonization official (Slocum 2004, p. 137). Fifty years after the murder, the saint’s corporeal remains were translated from the crypt of Canterbury Cathedral into an elevated shrine in a chapel east of the choir, now known as Trinity Chapel. The fifty-year span established a pattern of major celebrations every fifty years, which continued for three centuries (Foreville 1958). This translation occurred on 7 July 2020 and established a second feast for St. Thomas commemorating the Translatio. Celebrating the Translatio in July was opportune. It was a half year away from the existing feast of the saint and it moved the ceremonies out of the busy season surrounding Christmas. July was also ideal for a saint with a major pilgrimage cult, for July was neither the main time for planting nor harvesting, the weather was warm, and the roads were relatively dry. For those who could travel, July was a good time.

A third feast was celebrated in some places. The feast of the Regressio, or Return, commemorated Becket’s return to Canterbury Cathedral after six years of exile in France. Thomas landed at the port of Sandwich on Tuesday, 1 December 1170. The celebration of the Regressio at Canterbury is described in a surviving Customary of the shrine of St. Thomas of 1428, BL Ms. Add. 59616. The Regressio extended a list of important events in Becket’s life that fell upon Tuesdays. Portentous Tuesdays were a theme in Thomas’s biography. His birth, his flight from Northampton, his arrival in France, his return to England, and his martyrdom all occurred on Tuesdays. Two additional Tuesdays were added to the list in the thirteenth century, bringing the total to seven: a vision he experienced at Pontigny and the Translation. Complete liturgical offices existed for the martyrdom, translation, and return, although the Regressio appears to have been celebrated only at a limited number of sites where Thomas was a particularly important saint, naturally including Canterbury Cathedral (Slocum 2004, p. 248).

According to Becket’s biographers, he was welcomed by cheering crowds all along the way from his arrival port of Sandwich to Canterbury. Becket entered the town of Canterbury on horseback but dismounted in the street leading to the Cathedral and walked the final stretch barefoot (Slocum 2004, p. 58; Anonymous I N.d. [ca. 1176], p. 69; Herbert of Bosham N.d. [ca. 1185] p. 478). Becket’s return to Canterbury on December 2nd was likened to Christ’s entry into Jerusalem even in the earliest biographies (Duggan 2004, pp. 3–6). The feast of the Regressio, established later, appears to have taken up the triumphal theme. Falling at the beginning of December, it provided a narrative complement to the Christological seasons of both Advent and Easter.

3. Badges Commemorating the Regressio

The feast of Becket’s Regressio seems to have been commemorated with specially developed pilgrims’ badges. The production of pilgrims’ souvenirs at Canterbury and their use by pilgrims was established in the first decade after Becket’s death. In the first decades of the cult, the predominant type of keepsake was the small, metal ampulla. These ampullae could be filled with “Canterbury water,” water tinged with blood from the saint’s murder and regarded as having strong medicinal properties. The ampullae could be worn suspended around the neck, marking the wearer as a devotee of Saint Thomas. Somewhere around the year 1300, Canterbury badges came into widespread use and quickly displaced the ampullae as the most popular type of wearable sign among Canterbury pilgrims (Spencer 1998, p. 78). Canterbury is remarkable among medieval pilgrimage centers for the variety of its pilgrims’ badges. The most numerous type depicted the head reliquary that was displayed at Canterbury Cathedral. Others represented Becket’s tomb or full-length, iconic figures of the archbishop. There were also narrative scenes of Becket’s murder. Badges of episcopal gloves and slippers are likely badges from Canterbury recalling additional relics of Thomas Becket displayed at Canterbury, as are some of the miniature swords with scabbards and bucklers that were also worn as badges. Some pilgrims’ items were staff-tops representing the saint standing and blessing, perhaps to adorn walking sticks. Additionally, many bells and rattles seem to have had their origins in the Canterbury pilgrimage. The range of Canterbury badges is well represented in the catalogs by Brian Spencer (Spencer 1998; Spencer 1990), in the Kunera Database, and in the online collection of museums with strong badge collections such as the British Museum and the Museum of London.

Two types of pilgrims’ badges appear to have been associated with the Regressio. Both are comparatively large, complex, and finely detailed, presumably making them among the more expensive of the badges available at Canterbury, and both represent narrative scenes of Becket’s homecoming. The first type takes the form of ships and seems to refer to Becket’s arrival at Sandwich on the first Tuesday of December. These typically include a frontal image of St. Thomas standing on the deck, in exaggerated scale, raising a hand in blessing. We cannot say with utter certainty that these ship badges are connected with the feast of the Regressio because St. Thomas’s miracles include a number of maritime rescues, and badges of this sort might have appealed to pilgrims who traveled by sea, but the prominence of the ship theme among the badges and the importance of his return to English shores in his biographies makes it very likely.

The second type of badge shows the archbishop on horseback, and these are more securely associated with the feast of the Regressio at Canterbury. These badges clearly reference images of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem which depict Christ, mounted on a donkey, one hand raised in blessing, passing through the gates of the city, greeted by cheering followers and often by children climbing trees and tossing down boughs to strew before him. These images, canonical by the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries when these badges were popular, have their origins in the adventus processions of the Roman emperors, which artists of the fourth century adapted to contrast Christ’s humility with imperial splendor. Brian Spencer catalogues ship-shaped ampullae and ship badges that include an image of St. Thomas standing on the deck, as well as the equestrian badges all as connected to the feast day of the Regressio, and it allows that they may have caught on as badges from the Canterbury pilgrimage more generally over time (Spencer 1998, p. 79).

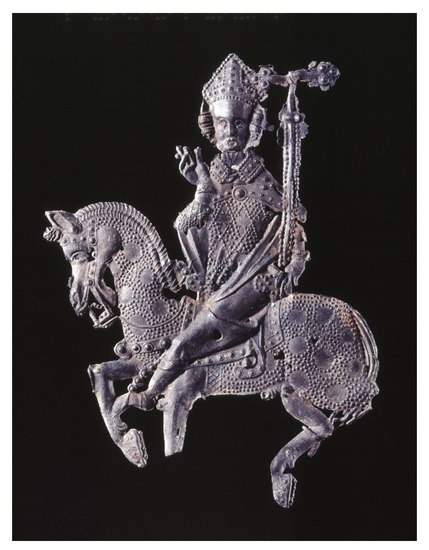

These equestrian badges show Saint Thomas mounted on a high-stepping horse represented in profile (Figure 1) (de Beer and Speakman 2021). There are multiple versions of the badge made from different hand-carved molds, but all adhere to the same basic type. Examples in varying degrees of preservation can be found among the online collections of the British Museum (British Museum Online Collection 2021), the Museum of London (Museum of London Online Collections 2021), and in the database of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS 2021). The horse invariably has spots, which are rendered in lead by smooth circles within a field of raised granules, likely implying a dappled gray. The archbishop’s mount is definitively shown to be a stallion. The animal tends to be led by a groom or other assistant diminutive in scale compared to the horse and its rider; this smaller figure has broken off and been lost from many examples of this type of badge. Becket himself rides astride but his torso and head are shown frontally. He wears episcopal regalia and carries a cross-topped staff in his left hand. His right hand is raised in a loose, two-fingered gesture of benediction. The flourish of his hand simultaneously displays his episcopal ring on the third or fourth finger. Becket’s upper torso and head appear very similar to badges depicting the head reliquary that was displayed in the easternmost Corona Chapel in the cathedral, with facial features such as a cleft chin and jeweled regalia (Splarn 2021).1 The reliquary did not survive the forcible closure of the cult in 1538, but its appearance can be deduced from the consistencies between the many pilgrims’ badges that replicate it. These badges, and presumably the reliquary, show St. Thomas wearing a jeweled miter, with a vertical band of jewels on the central axis and a jeweled band across the brow. Other jewels arranged symmetrically adorn the two halves. He also wears a jeweled collar, which on the equestrian badges is interpreted as the border of a cope. The image is definitively that of a bishop arriving in triumph and splendor.

Figure 1.

Pilgrim badge, lead alloy, height 93 mm, width 76.9 mm, depth 3.8 mm. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

4. Badges and the Altarpiece of the Englandfahrer

These badges of Thomas Becket on horseback may have served as a visual source for a panel in an altarpiece in the Hanseatic city of Hamburg. The panel is one of eight complete surviving panels and one partial panel from an altarpiece painted by Meister Francke for a guild known as the Englandfahrer. The Englandfahrer were merchants based in Hamburg who traded with England. Thomas Becket was their patron saint, and in 1424 they commissioned the work from Meister Francke. In 1436 it was installed in their chapel in the Dominican church of Saint John in Hamburg. The surviving panels are now in the Hamburger Kunsthalle. That so little contextualizing scholarship has addressed this altarpiece is largely due to the frustrating lack of surviving documentation about the work or its patrons. Nevertheless, visual analysis and comparison with the contemporary badges of the Regressio allow new inferences that suggest a visual link to Canterbury.

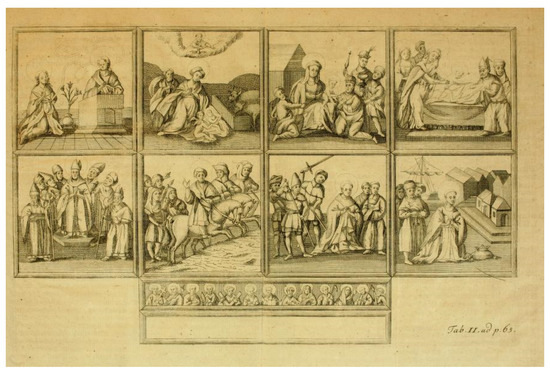

In the altarpiece of the Englandfahrer, the lower left of the surviving panels, originally second from left, depicts a scene of Thomas Becket on horseback (Figure 2). This painting is one of two surviving panels out of an original series of four narrating events from Becket’s life and death. The lost panels from the wings are recorded in an engraving published in 1731 by Nicholas Staphorst (Staphorst 1731, vol. 2, p. 65). From left to right, the panels depicted Becket enthroned and surrounded by a group of ecclesiastics, the scene of Becket and his companions on horseback, a scene of Becket’s assassination, and a scene in a shipyard that may be a posthumous appearance of St. Thomas witnessed by merchants (Figure 3). The rest of the altarpiece includes four panels of the life of the Virgin, paired with the Becket panels, and when fully opened, a cycle of the passion of Christ. The scene of Thomas Becket on horseback appears to be unique among surviving paintings both in its subject and composition. Although it does not depict Becket’s return to English shores per se, it does refer to the events of December 1170 and to Thomas’s return to his see at Canterbury.

Figure 2.

Meister Francke, Thomasaltar, closed position, tempera and oil on oak, each panel 99 × 89 cm, begun 1424. Photo: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany/Bridgeman Images.

Figure 3.

Thomasaltar, engraving showing lost wing panels published in Nicholas Staphorst’s HamburgischenKirchen-Geschichte, 1731. Photo: courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

Becket is shown mounted on horseback, riding with two companions.2 His horse is white, or in equestrian terms, a grey. His nearest companion appears to ride an orange horse, likely suggesting a chestnut color, while the third man is mounted on a darker, dappled gray. As on the badges, Becket wears spurs and pointed footwear. Unlike the badge images, the painting does not show him wearing his jeweled cope and miter, but his horse does wear embellished tack. Jewels on the badges are indicated by a ring and dot pattern, which is easily achieved by carving or drilling a circular depression into the mold and incising a deeper circle within it. When the image is cast, the form is reversed to create a two-level raised dot. On the Regressio badges, this form ornaments not only the archbishop’s costume but also the connection points on the horse’s bridle and the band and central element of a breast collar that stabilizes the saddle. These same ornaments are present in the panel painting, depicted as gold ornaments in ring-and-dot form. Only the point where the bit joins the bridle has been augmented with petals.

The bishop is mounted astride but turns his torso to present a nearly frontal view. He turns his head to further face the viewer. In the painting, this twisting posture is interpreted as a look over his shoulder at the group behind him. Becket raises his right hand, gloved in white, the wrist flexed backwards and the fingers gracefully flourished, thumb uppermost. The gesture differs from some equestrian badges where the bishop is clearly blessing with two fingers but is extremely similar to others where the gesture is more of a wave (Spencer 1998, p. 85). The fingers are positioned so that the bishop’s palm faces the viewer, but his episcopal ring is nevertheless clearly visible.

The similarities between this painted image and pilgrims’ signs of St. Thomas on horseback are striking. They are all the more intriguing due to the unusual subject of the painting. Images of the murder in the cathedral are plentiful, not only in badges but also in manuscripts, wall paintings, Limoges reliquaries, stained glass, and architectural sculpture, seals, and other badges (Borenius 1932, pp. 70–104; Duggan 2020). Meister Francke could have consulted any number of sources in composing the martyrdom scene. When it came to the image of Becket on horseback, his potential sources were few. The most similar image remaining today, apart from the badges, is from the manuscript BL Loan MS 88, known as the “Becket Leaves,” surviving folios from an English illustrated manuscript from c. 1220–1240 (de Beer and Speakman 2021, p. 177; Slocum 2018, pp. 44–45). Folio 2v depicts Thomas departing from kings Henry II and Louis VII (Backhouse and de Hamel 1988, p. 26; Borenius 1932, pp. 41–42, plate XI).3 The composition is comparable, with Becket riding toward the right of the frame while turning back and gesturing toward a cluster of discontented adversaries at the left. In the manuscript, Becket points with a single finger. He rides alone, and the kings at the left and the group of popular supporters at the right of the frame place the scene earlier in the narrative. This rare surviving manuscript may hint at a family of related images in which a mounted Becket gestures to the rear, of which the Regressio badges were a part. Manuscripts, paintings, and stained-glass windows were singular artistic creations. The badges of Becket riding, on the other hand, were cast in re-useable molds and were therefore numerous. The specific details shared between the badges and the Hamburg painting suggest that within such a family of images, the badges are the altarpiece’s nearest kin. It is not difficult to suppose that, when asked to compose this unusual scene for the altarpiece, Francke referenced a pilgrim’s badge that was near at hand in Hamburg. For, while most other known types of Becket images in the fifteenth century were either stationary or exclusive to elite owners, the pilgrims’ badges were highly mobile, inexpensive, and produced in multiples. Access to such images would have been relatively simple. It is also easy to imagine that one or more members of a brotherhood professionally engaged in trade and travel between Hamburg and England might have acquired such a badge on a visit to the shrine of their patron saint, perhaps even during the year 1420, the 200th anniversary of the Translatio.

5. The Assault on Becket’s Horse

If the composition of the panel painting appears to derive from a pilgrim’s badge associated with the Regressio, the tone, is anything but triumphal. Instead of a heroic archbishop returning to cheering crowds, Becket here appears as a traveler harassed by a jeering mob. They point fingers at him and one shows a sword half-way out of its scabbard. The villains have just brutally cut off the tail of Becket’s horse, the stump still dripping blood, perhaps foreshadowing the blood to be shed at his martyrdom. One of the perpetrators holds the amputated tail to his crotch in a mocking, phallic gesture, graphically illustrating the symbolism of tail docking, explained by Andrew N. Millar as the symbolic deprivation of the animal’s owner of masculinity and reputation by the excision of the phallic-like extension from his beast (Millar 2013). The painted scene refers to an event described by five of Becket’s biographers and included in at least two chronicles (Thomas 2012). On Christmas eve 1170, four days before the murder, Robert de Broc, or his nephew John, cut off the tail of a horse belonging to the archbishop. The following day, the archbishop excommunicated Robert, according to FitzStephen, for injuring a horse belonging to one of his servants at Canterbury (Greenaway 1961, p. 147; FitzStephen n.d. [ca. 1174], p. 130). Distancing himself from direct ownership of the beast may have deflected some of the shame intended by the act.

Between Becket’s return from exile on December 1 and his murder on 29 December, he was subject to various restrictions and harassment. Other violence against Becket’s animals had also been perpetrated during his final days at Canterbury, including attacks against his pack horses, against the deer in his park, and against his hunting dogs (FitzStephen n.d. [ca. 1174], p. 126). The biographers describe a division between popular support for the archbishop and those eager to demonstrate their loyalty to the king. Presumably, those committing acts of brutality against Becket’s creatures did so with the hope of currying favor with Henry, an impulse that culminated in the murder of the archbishop himself.

Millar makes the important point that the offense against the horse, more than the other instances of harassment, was reiterated by multiple biographers and chroniclers, and that this indicates how widely the symbolism of tail-docking was understood in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in England (Millar 2013). Its inclusion in this altarpiece shows that it resonated in the fifteenth century in the north of Germany as well. Despite the widespread recognition of the implications of tail-docking, the incident was seldom included in visual narratives of St. Thomas (Slocum 2018, pp. 110–40). This altar panel appears to be the sole example among the surviving corpus and must have been rare, if not unique, at the time of its creation. Without artistic conventions to follow, the artist may have relied on a familiar pilgrims’ badge to forge an authentic link between his painting and the pilgrimage center at Canterbury.

The events occurring in December between Becket’s return to England and his murder do not often appear in art. The archbishop’s return from exile is more typically represented at the port of Sandwich, such as in the narrative sequence in the Queen Mary Psalter, British Library, Royal MS 2.B.vii, c. 1310–1320. Presumably, the equestrian images were associated with the town and cathedral of Canterbury, where he arrived on horseback and where pilgrims would later acquire the badges. Two panels in the Becket wingdow in a southern radial chapel at the east end Chartres Cathedral c. 1215–1225 show the saint mounted, of which one depicts him turning to look outward while approaching an unidentified crenellated gate with doors wide open (Borenius 1932, pp. 45–46; Deremble and Deremble 2003, pp. 128–33).4 It is possible that this scene also represents his return to Canterbury, although its location in the lowest quadrant of the window makes it more likely that it indicates an arrival somewhere earlier in the narrative, before his exile in France, and the overall emphasis of the window’s narrative is more compatible with an earlier event (Slocum 2018, p. 127).

Meister Francke’s painting of Becket on horseback shares some significant elements with his panel in the same altarpiece of Christ carrying the cross. The man who holds the tail of the prelate’s horse stands among a cluster of four men. Two of them point crooked fingers at the riders and two have heavy features and rather short faces. These features also characterize perpetrators against Christ in the altarpiece’s passion scenes, especially in the carrying the cross panel where those jeering at Christ are also depicted pointing. One man propels Christ onward with a wooden baton that is quite similar to one wielded by one of the attacking knights in the panel of Becket’s murder (Figure 2). These visual similarities draw parallels between the torment and execution of Christ and that of Becket. That Becket’s suffering and death was Christ-like and that Becket’s blood was restorative just as Christ’s brought salvation was a theme made explicit in both biographies and liturgies for Becket. For instance, Benedict of Peterborough’s office for the Feast Day of St. Thomas includes the lines, “Pastor caesus/in gregis medio/pacem emit/cruoris precio./O laetus dolor/in tristi gaudio:/grex respirat/pastore mortuo;/ plangens plaudit/mater in filio,/quia vivit/victor sub gladio.” (The shepherd cut down in the midst of his flock has purchased peace at the cost of his blood. O joyful sorrow in sorrowful joy: the flock is revived by the shepherd’s death, the grieving mother applauds her son, who lives and triumphs beneath the sword).” (Reams 2000, p. 566). Within the context of the altarpiece, which includes sequences of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and Thomas Becket, the tail-docking scene articulates the idea of Becket as a type of Christ. However, while Christ was tormented physically, the attacks leading up to Becket’s death were assaults against his social position and mostly took place offstage, so to speak. The mutilation of the horse, exaggerated here by presenting it as an animal being ridden by Becket during the attack, brings the persecutions as close as possible to the body of the bishop himself.

6. Tail-Docking in the Eyes of the Englandfahrer

Why should a guild of merchant traders in Hamburg have felt the need for novel imagery in their altarpiece for Thomas Becket? Why did they select these unusual scenes to represent his vita? So little is known of the Englandfahrer of Hamburg that it is difficult to answer these questions with confidence (Slocum 2018, pp. 77–78). Records from the guild no longer survive, and the Dominican church of Saint John where their chapel, for which this altarpiece was created, was destroyed in 1829, the altarpiece itself having been dismantled in the previous century (Leppien 1999, p. 142). The Englandfahrer were not alone in their interest in Thomas Becket at Hamburg in the first quarter of the fifteenth century, so the merchants may have been part of a broader enthusiasm for St. Thomas in Hamburg at that time Another altarpiece of Thomas Becket was given by a noble patron and alderman, Eric von Tzeven, to the cathedral in Hamburg a year before the merchants’ commission to Meister Francke (Staphorst 1731, vol. 2, pp. 252–53). Becket’s reputation as a saint had several faces. For some, he was a miraculous healer; the pilgrimage cult at Canterbury owed much to this aspect. He also aided ships in distress. For other followers, he was a defender of the rights of the Church against incursions from the crown. In other contexts, he was a defender of the poor or a protector of London. For many, he represented opposition to royal authority.

The tail-docking incident did not carry any liturgical importance on its own, and it was not one of Becket’s Tuesdays. The scene as depicted in the painting is implausible, for one cannot ride placidly along on a horse being subjected to mutilation. Rather, the combination of Becket riding and the animal’s mutilation appears to conflate the events between 1 December and 25 December into a single image that emphasizes the persecutions of Becket in the name of the king. As I have argued elsewhere regarding the fourth panel in the series, the merchants of Hamburg who did business with England may well have selected Thomas as their patron for his resistance to the king (Lee 2020). English kings had supported German merchants in England during the economic rise of the Hanseatic trade. In the first decades of the fifteenth century, however, the kings of England had withdrawn most of their support and had begun collecting taxes from which the German merchants had previously been exempt. If the Englandfahrer were feeling themselves to be poorly treated by the English crown, it would explain why this uncanonical scene that emphasizes the harassment of Becket in the days before his murder might have been chosen as one of the four scenes for this narrative representation.

7. Conclusions

Fitting works of art into stemma is no longer an end goal of art historians and it is not the purpose of the present analysis. It was attempted inconclusively for the Hamburg altarpiece in the early part of the twentieth century, both to trace the expansion of the cult of St. Thomas and to delineate the career of Meister Francke. For both efforts, the altarpiece was deemed unique and therefore unserviceable for indicating connections to works in other locations (Borenius 1932, pp. 58–61, Pl XIX). The claim to uniqueness must be taken with skepticism of course, given that the majority of late medieval works of art have been lost. Moreover, by the fifteenth century, St. Thomas was an established saint throughout most of Europe, whose imagery by this time was shared through a web of sites rather than spreading from a single point of origin. However, despite these caveats, it is worth revisiting the question of image dissemination once more to bring pilgrims’ badges more fully into the discussion. Although researchers such as Borenius were aware of pilgrimage souvenirs, they maintained a conceptual division between so-called high and low art and did not consider the badges to be among the possible sources for a monumental painting.

The close resemblances between the panel in Hamburg and the badges of the Regressio suggest that the copying could be reciprocal. With badges so numerous in England, the Netherlands, and northern Germany, and so easily and intentionally portable, they would have been ideal vectors for carrying visual ideas into and between the Hanseatic cities. The distribution of Canterbury badges in the coastal cities of northern Germany is clearly demonstrated by the Kunera Database (Kunera 2021, which maps the locations where medieval badges have been found. To the Englandfahrer, a fraternity of merchants whose collective identity was invested in travel between the German cities and England, a badge that had itself been carried from Canterbury might have been an especially appropriate foundation for the artwork in their guild chapel. If this was the case, as seems likely but cannot be conclusively proven, then it reverses the expected hierarchy of medium in favor of forging a connection to Canterbury by means of a visual object that originated at the saint’s own center.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Image of a pilgrim’s badge depicting the reliquary bust of Thomas Becket. https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/37256.html. Accessed on 21 July 2021. |

| 2 | Image: Meister Francke, Die Verhöhnung es hl. Thomas von Canterbury, tempera and oil on oak, c. 1426. https://online-sammlung.hamburger-kunsthalle.de/en/objekt/HK-490. Accessed on 21 July 2021. |

| 3 | Image of BL Loan MS 88, fol. 2v https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/65/Becket_and_the_kings_part_-_Becket_Leaves_%28c.1220-1240%29%2C_f._2v_-_BL_Loan_MS_88.jpg. Accessed on 21 July 2021. |

| 4 | Image of Becket mounted, approaching a crenellated gate, stained glass window at Chatres Cathedral. https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3AFCW018AP0701. Accessed on 21 July 2021. |

References

- Ainalov, Dmitriῐ V. 1961. The Hellenistic Origins of Byzantine Art. Edited by Cyril Mango. Translated by Elizabeth Sobolevitch and Serge Sobolevitch. Originally published 1901 in the Bulletin of the Imperial Russian Archaeological Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. First published 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous I N.d. [ca. 1176]. Vita Sancti Thomae, Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi et Martyris, sub Rogerii Pontiniacensis Monachi. In Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury. Edited by James Craigie Robertson. London: Longman and Co., vol. 4, pp. 1–79.

- Backhouse, Janet, and Christopher de Hamel. 1988. The Becket Leaves. London: The British Library. [Google Scholar]

- Binski, Paul. 2004. Becket’s Crown: Art and imagination in Gothic England, 1170–1300. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blick, Sarah. 2005. Reconstructing the Shrine of Thomas Becket, Canterbury Cathedral. In Art and Architecture of Late Medieval Pilgrmage in Northern Europe and the British Isles. Edited by Sarah Blick and Rita Tekippe. Leiden: Brill, pp. 405–41. [Google Scholar]

- Borenius, Tancred. 1932. St. Thomas Becket in Art. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- British Museum Online Collection. 2021. Available online: https://www.BritishMuseum.org/collection (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- de Beer, Lloyd, and Naomi Speakman. 2021. Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint. London: The British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Deremble, Colette, and Jean-Paul Deremble. 2003. Vitraux de Chartres. Paris: Éditions Zodiaque. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Anne. 2004. Thomas Becket. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Anne. 2016. Becket is Dead! Long Live St Thomas. In The Cult of St Thomas Becket in the Plantagenet World, c. 1170–1220. Edited by Paul Webster and Marie-Pierre Gelin. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Anne. 2020. Becket’s Cap and the Broken Sword. Jacques de Vitry’s English Mitre in Context. Journal of the British Archaeological Association 173: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzStephen, William. [1174?]. Vita Sancti Thomae. In Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury. Edited by James Craigie Robertson. London: Longman and Co., vol. 3, pp. 1–154. [Google Scholar]

- Foreville, Raymonde. 1958. Le Jubilé de Saint Thomas Becket du XIIIᵉ au XVᵉ siècle (1220–1470): Etude et documents. Paris: S.E.V.P.E.N. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1958. Ampoules de Terre Sainte (Monza-Bobbio). Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Georgeand Greenaway. 1961, The Life and death of Thomas Becket, Chancellor of England and Archbishop of Canterbury, Based on the Account of William FitzStephen, His Clerk, with Additions from Other Contemporary Sources. London: The Folio Society.

- Herbert of Bosham. [1185?]. Vita Sancti Thomae, Archiepiscopi et Martyris. In Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury. Edited by James Craigie Robertson. London: Longman and Co., vol. 3, pp. 155–534. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, John. 2020. Modelling the Cult of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral. Journal of the British Archaeoloigical Association 173: 100–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunera. 2021. Radboud Universiteit. Available online: https://www.kunera.nl (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Lee, Jennifer. 2020. The Merchants’ Saint: Thomas Becket among the Merchants of Hamburg. Journal of the British Archaeological Association 173: 174–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppien, Helmut. 1999. Meister Francke, Thomas-Altar, 1424–1436. In Goldgrund und Himmelslicht. Die Kunst des Mittelalters in Hamburg. Edited by U. M. Schneede. Hamburg: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Dölling und Galitz Verlag, pp. 141–51. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, Andrew N. 2013. ‘Tails’ of Masculinity: Knights, Clerics, and the Mutilation of Horses in Medieval England. Speculum 88: 958–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museum of London Online Collections. 2021. Available online: https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/collections (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Portable Antiquities Scheme. 2021. Available online: https://www.finds.org.uk (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Rasmussen, Ann Marie. 2021. Medieval Badges. Their Wearers and Their Worlds. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reams, Sherry. 2000. Liturgical Offices for the Cult of Thomas Becket. In Medieval Hagiography, an Anthology. Edited by Thomas Head. New York and London: Garland Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, Kay Brainerd. 2004. Liturgies in Honour of Thomas Becket. Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, Kay Brainerd. 2018. The Cult of Thomas Becket: History and Historiography through Eight Centuries. London: The Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, Jakov I. 1887. Hristiankija mozaiki Kipra. Vizantinjskij Vremennik 4: 1–93. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Brian. 1990. Salisbury & South Wiltshire Museum Museum Catalogue, Part 2: Pilgrim Souvenirs & Secular Badges. Salisbury: Salisbury & South Wiltshire Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Brian. 1998. Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges. Medieval Finds from Excavations in London. London: The Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Splarn, Lucy. 2021. Heads Up: Comparing the Canterbury Collection of Saint Thomas Becket Head Badges with the Lost Head Reliquary. Paper presented at the 56th International Medieval Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo, MI, USA, May 14. [Google Scholar]

- Staphorst, Nicholas. 1731. Historia Ecclesiae Hamburgensis Diplomatica, das ist: Hamburgische Kirchen-Geschichte. Hamburg: Felginer. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Hugh M. 2012. Shame, Masculinity, and the Death of Thomas Becket. Speculum 87: 1050–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikan, Gary. 1995. Early Byzantine Pilgrimage Devotionalia as Evidence of the Appearance of Pilgrimage Shrines. In Akten des XII. Internationalen Kongresses für christilche Archäologie, Bonn, 22–28 September 1991. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, vol. 1, pp. 377–88. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann, Kurt. 1974. Loca Sancta and the arts of Palestine. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 28: 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).