External Shocks in the Art Markets: How Did the Portuguese, the Spanish and the Brazilian Art Markets React to COVID-19 Global Pandemic? Data Analysis and Strategies to Overcome the Crisis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. The Health of the Art Markets. Three Countries under Analysis. Findings

3.1. Portugal: What Is the Extent of the Impact of COVID-19 in the Art Markets Sector?

3.1.1. Strategies to Overcome the Crisis and Changing Priorities for the Sector

3.2. Spain: What Is the Extent of the Impact of COVID-19 in the Art Markets Sector?

- -

- capacity measures for commercial spaces that live off their sales have an impact on billing;

- -

- there is a lack of consideration of galleries as a public service of cultural offer;

- -

- the number of galleries and the subsidy amount must be increased, up to about EUR 20,000, since the actual subsidies are insufficient in relation to the work and reality of art galleries;

- -

- the most important thing that will help save the sector would be the elimination of VAT for one year and subsequently its reduction to 10%;

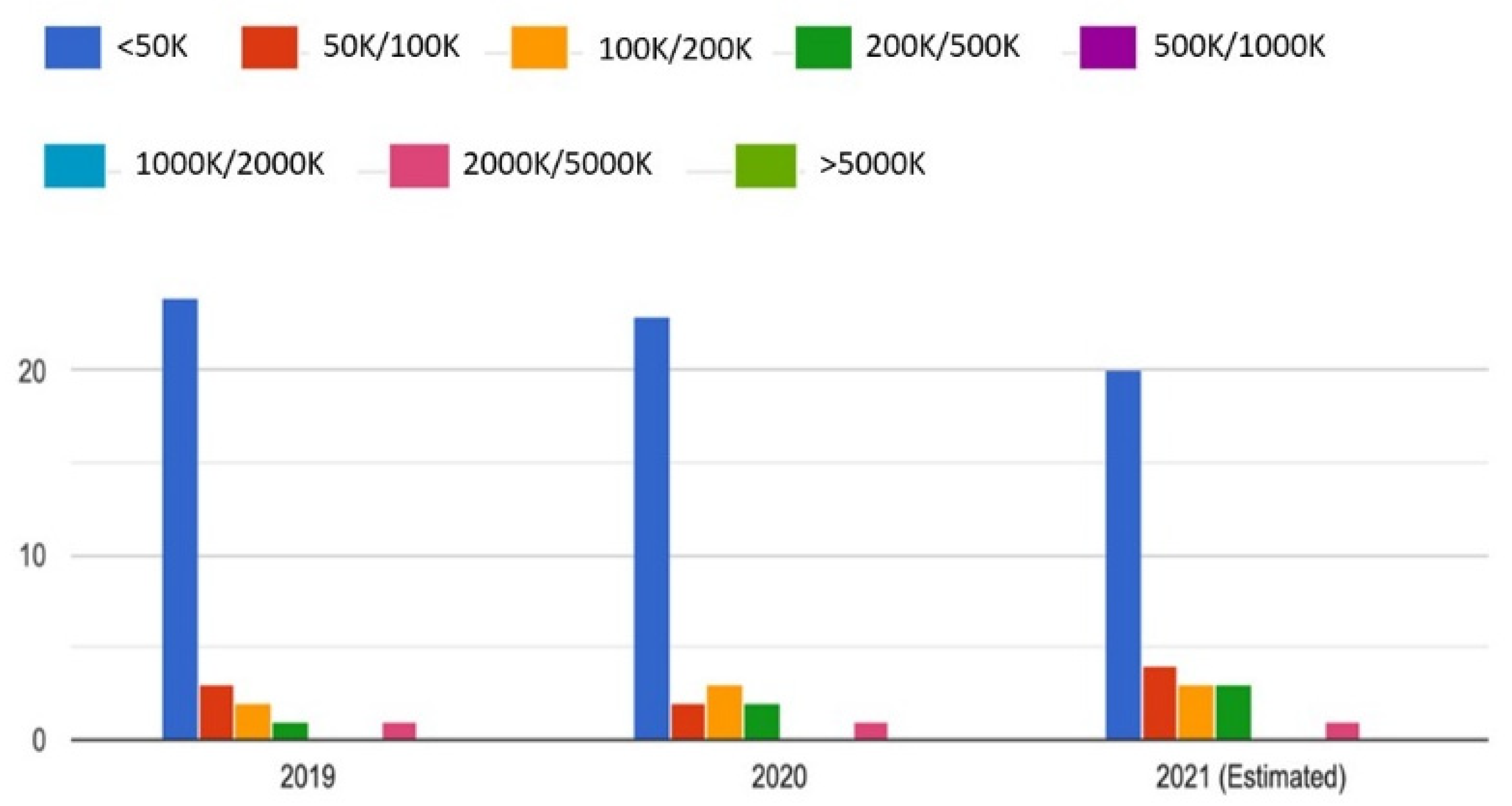

- -

- the needs of small galleries must be taken into account since their scope is the internal market.

Strategies to Overcome the Crisis and Changing Priorities for the Sector

- (a)

- The first group of specific measures for art galleries:

- -

- Approving a subsidy for the production of exhibitions and canceled projects.

- -

- Immediate help of €2000 per gallery.

- -

- Streamlining of grants and contracts or institutional purchases.

- -

- Lines of credit without interest and in the medium or long term. They can help to face not as many of the expenses derived from a specific or special project but the normal operating expenses.

- -

- Financial help to produce exhibitions to be held in art galleries in Spain.

- -

- Increasing the amount dedicated to aiding the promotion of art (participation in fairs), as well as reaching more galleries. Expediting the process of call and concession.

- -

- Taking part in art fairs will be fundamental in order to regain activity. Applying and participating in them normally requires a significant advance payment, in what will undoubtedly be the worst moment of liquidity for galleries. On the other hand, due to the international nature of this crisis, many galleries have already faced the payment of international fairs that have either suffered a lot like those held in Spain or been delayed. Galleries have already paid all the costs of renting spaces in those art fairs, which will be held in what will still be a very complicated time, so it is foreseeable that they will throw more losses. Public aid to favor participation in fairs is therefore essential for the Spanish market. It is very important to point out that the previous measures would benefit the artists themselves and in a very direct way.

- (b)

- The second group of measures in line with other companies and professionals in the sector:

- -

- Postponement of tax payments.

- -

- Continuing with the review and rethinking the cultural expense of 1.5% of all public infrastructure works by the Government, in permanent dialogue with the sector.

- -

- Possibility of suspension for at least one- or two-month fees of the self-employed professionals and self-employed entrepreneurs.

- (c)

- Other measures:

- -

- Encouraging purchases of Spanish museums, public collections and institutions in Spanish galleries.

- -

- Finally, opening a fluid and committed dialogue on the part of the ministry with the gallery sector to deal in depth with some of the eternally pending issues, especially the aforementioned VAT that the Spanish galleries suffer in comparison with the other cultural sectors.

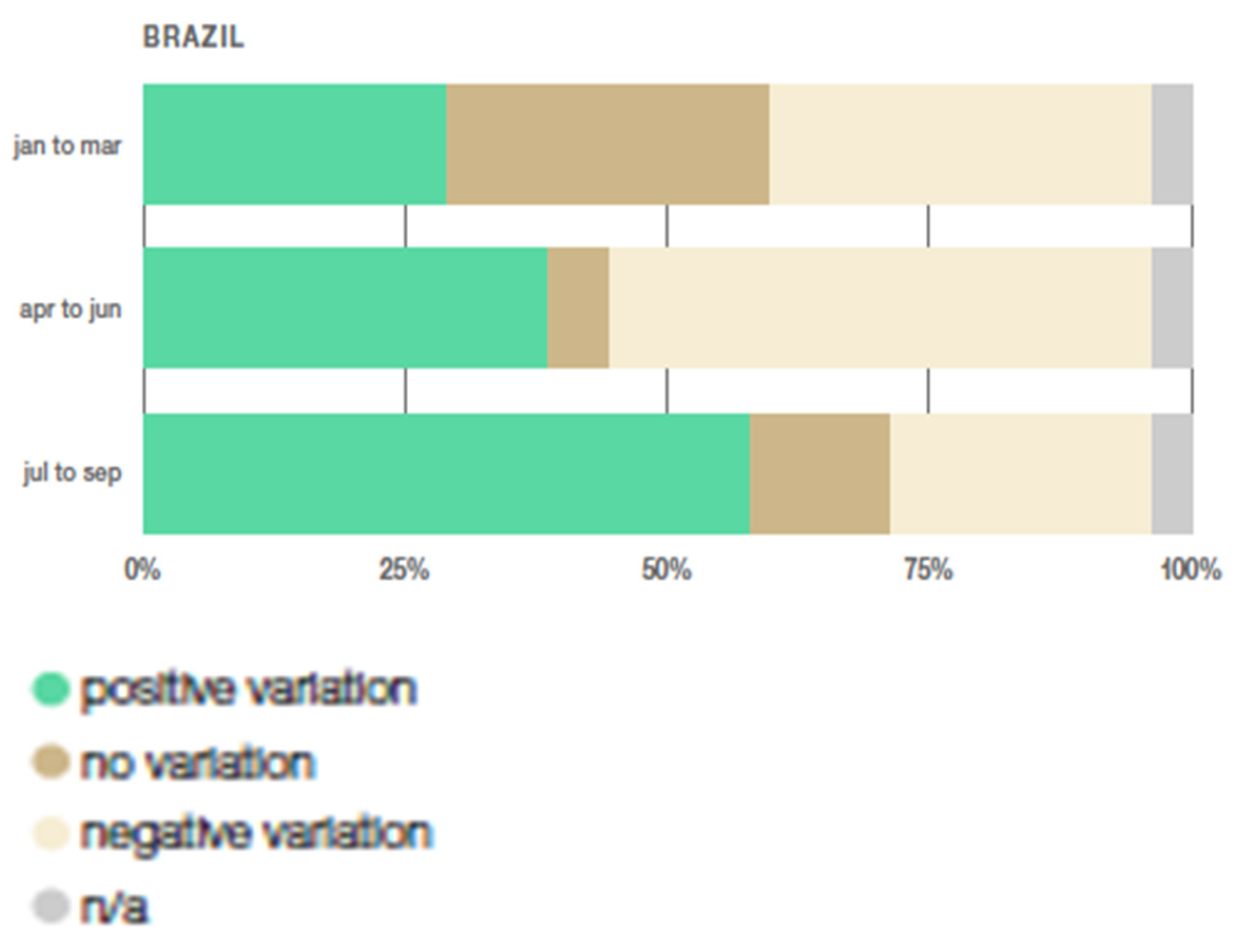

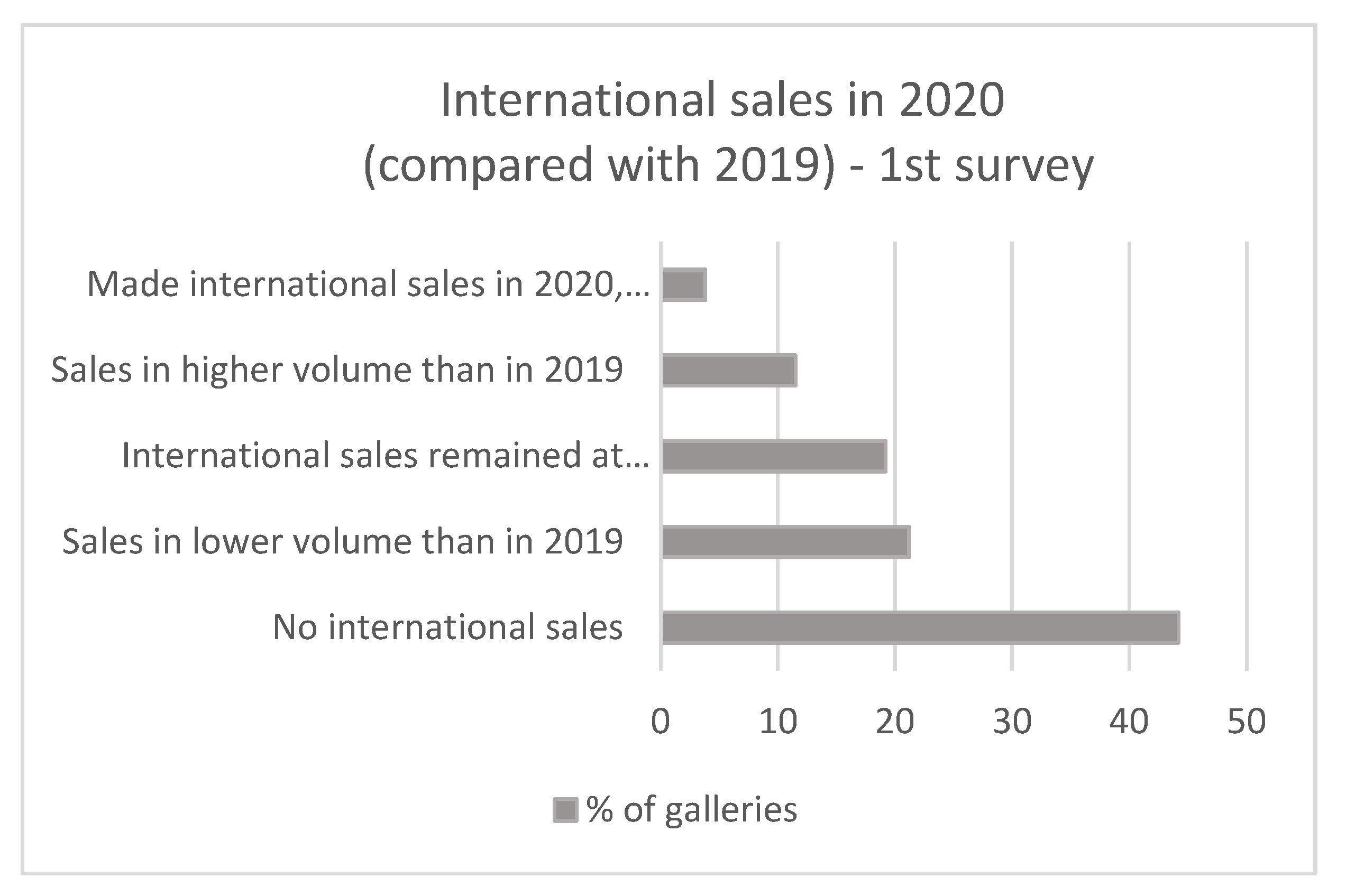

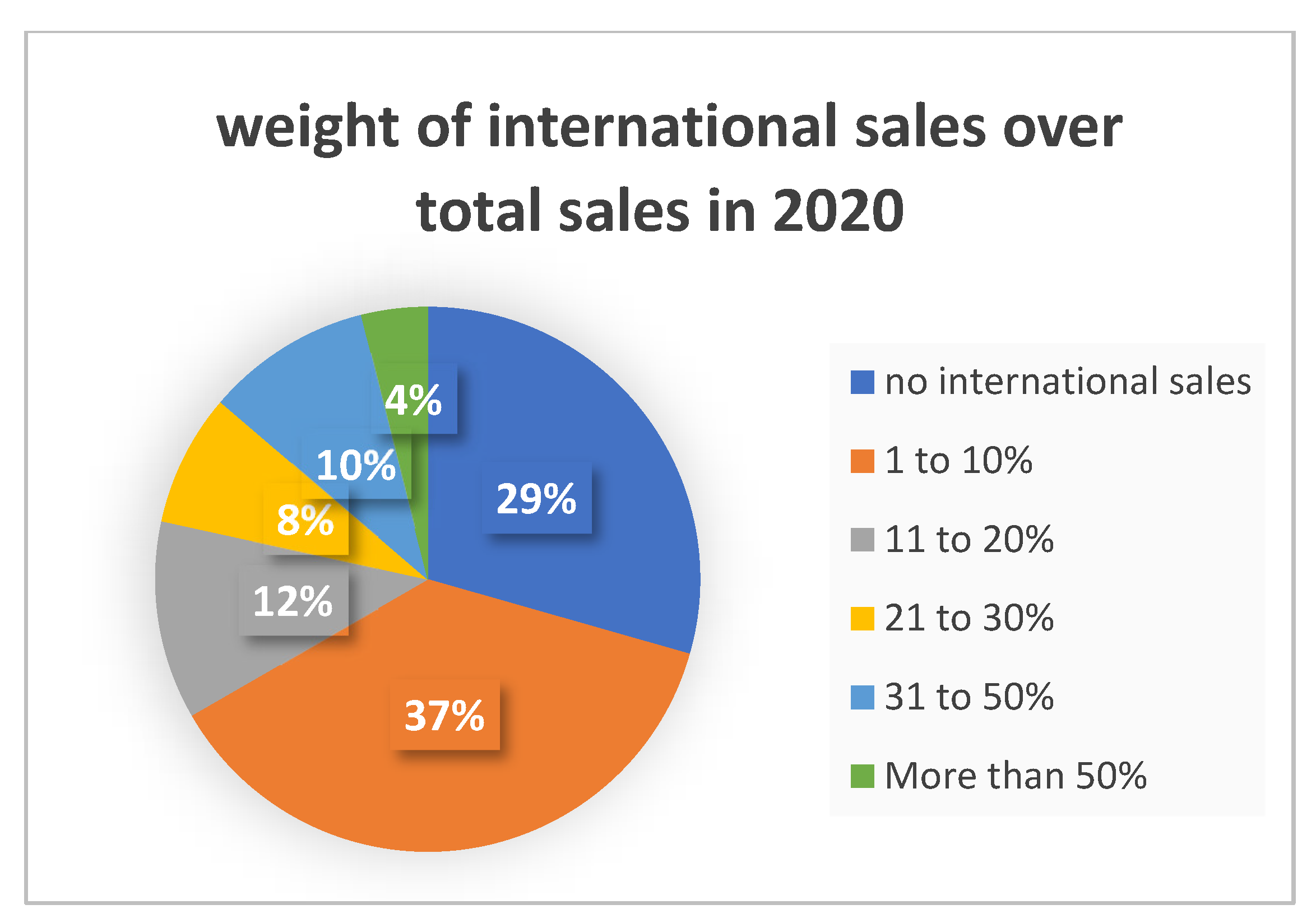

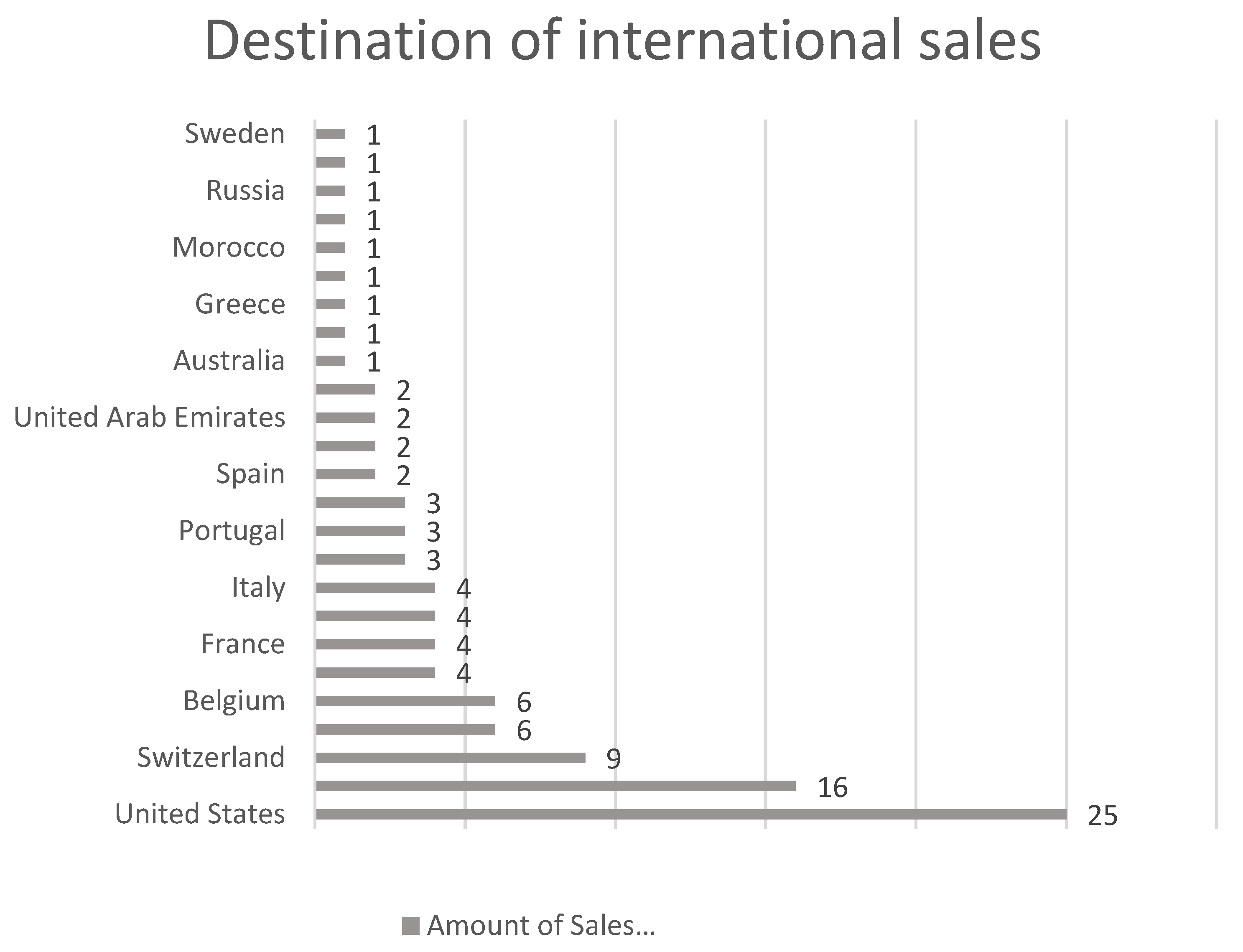

3.3. Brazil: What Is the Extent of the Impact of COVID-19 in the Art Markets Sector?

“In the very first months of the pandemic people did not know what to do, how to react, it was a shock. We expected it would not last … then, we realized that we had to react, to find new ways to work, to help our artists …”35.

Strategies to Overcome the Crisis and Changing Priorities for the Sector

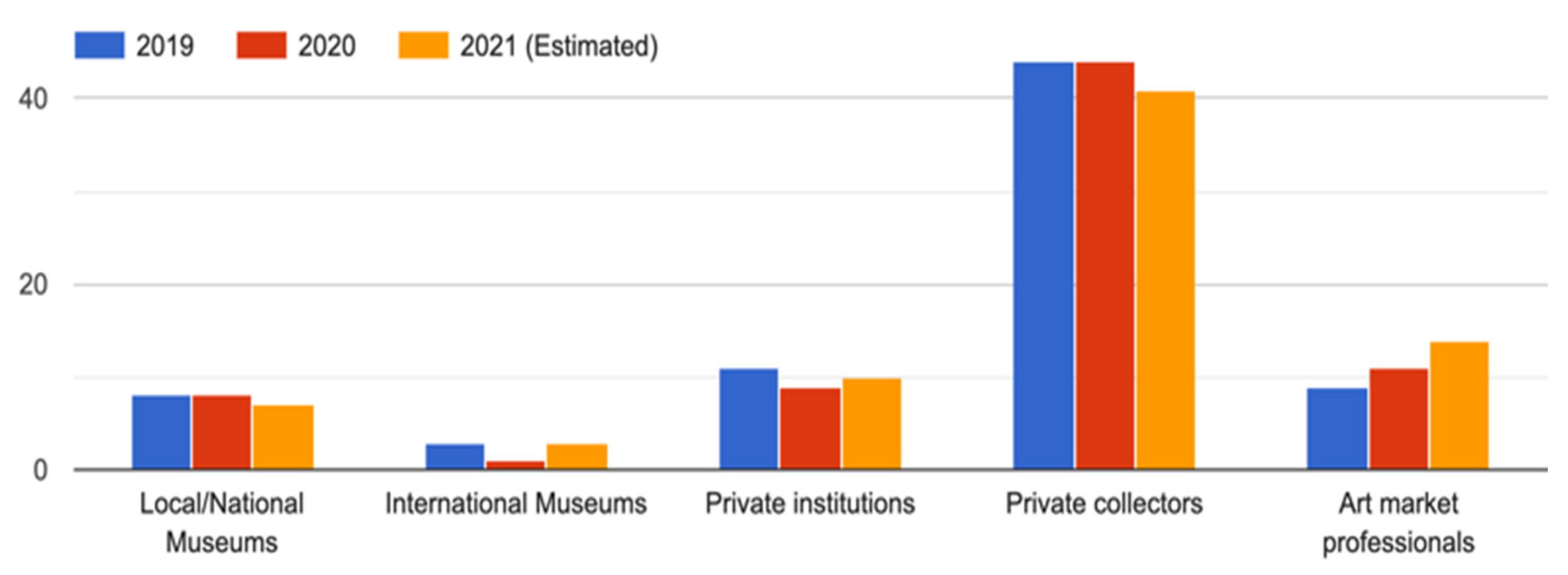

4. Results and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Some examples: TEFAF 2020 was interrupted; Art Basel Hong Kong 2020, ARCOlisboa 2020, SP-Arte 2020, Lisbon Art Antiques Fair, LAAF 2020, and among others, were cancelled; ARCOmadrid 2021 and SP-Arte 2021, among others, were postponed. The global estimate of cancellations in 2020 is 61% (McAndrew 2021, p. 20), but empirical observation indicates that the percentage can be higher. Still, the results of the art markets reports, such as the reports issued by Arts Economics and Dr. Clare McAndrew, must be handled with reservation as the estimated figures on the primary art markets show huge variations due to the lack of information, particularly of private sales. Nevertheless, sometimes academics use this data (Velthuis and Curioni 2015; Zarobell 2017). |

| 2 | None of the three countries would fit the small group of “prescripteurs” of contemporary art (Quemin 2002) or the start system (Quemin 2013a). |

| 3 | For example, the contemporary art fairs, e.g., ARCOmadrid, Drawing Room, JustMad, launched a branch in Lisbon, since 2016 (Duarte 2020). |

| 4 | A recent initiative by 3 Brazilian galleries—Fortes D’Aloia and Gabriel, Galeria Luisa Strina and Sé—is presented in Portugal during the 2021 summer: “O Canto do Bode (The Song of the Goat) is a collaborative exhibition at the Casa da Cultura da Comporta. Three Brazilian galleries from different generations join global initiatives in building new working models in an unprecedented context for the art circuit. In total, 32 artists represented by the galleries, in addition to 4 guest artists, will occupy a former cinema within the historic Casa da Cultura at the Herdade da Comporta Foundation, which becomes a pop-up gallery in the European summer.” Luisa Strina and Fortes, d’Aloia e Gabriel are very well-established Brazilian galleries with a strong international presence, being part of the most prestigious art fairs as Art Basel and Frieze for decades (Fortes, d’Aloia e Gabriel also keeps an office in Lisbon since 2014), and Sé is a younger but internationally ascending gallery. The choice of hosting an event in Portugal is mentioned by gallery owners as part of a plan to strengthen ties with the country and to respond to artists’ expectations. Another example is Nowhere Lisbon, an independent space founded by Brazilian curator Cristiana Tejo and Brazilian artist Marilá Dardot in 2018. Shortly after the beginning of the pandemic, Tejo and Dardot, together with other artists and art market players, launched, from Lisbon, a hybrid commercial initiative called Quarantine, aiming to help artists and social projects to face the crisis. |

| 5 | The team had already organized workshops and lectures between its members, and a conference on the Art Market and the Global South, in Lisbon. For further information about the cluster’s aim, see (Anonymous 2019): “Cluster art market and collection.” Available online: https://ihapgmercado.weebly.com/cluster-amc.html (accessed on 28 May 2021). |

| 6 | We have not segmented the art markets typologies in terms of artistic representation because some of the categories would be under-represented in the three countries, for example, internationally recognized talents (Moureau and Sagot-Duvauroux 2006, pp. 23–27) or the blue-chip category. |

| 7 | The international dimension that participation in art fairs allows is of relevance and contributes to the ranking of the gallery performance and its artists (Quemin 2020, 2013b). Most Brazilian and some Spanish galleries in this study do have that international dimension, while the majority of Portuguese galleries have a local scope. |

| 8 | Mapa das Artes is a yearly update website, created in 2016, with information about galleries, museums and art centers active in the city (Anonymous 2021b). |

| 9 | The phone contact led us to exclude sixteen galleries from the first list because we concluded they had no activity in the years under study. The final number was seventy. |

| 10 | We do not pretend to have gathered all active art galleries in Portugal (there is certainly more than seventy), but we did have the cooperation of the most relevant between this set, and we estimate to have a very representative sample. |

| 11 | This declaration follows up the Decree of the President of the Portuguese Republic, published on 18 March (Decreto do Presidente da República n° 14-A/2020 de 18 de março). |

| 12 | The others cities pointed were: Coimbra, Figueira da Foz, Braga, Ponta Delgada in Ílha dos Açores, Ílhavo, Funchal in Ílha da Madeira. |

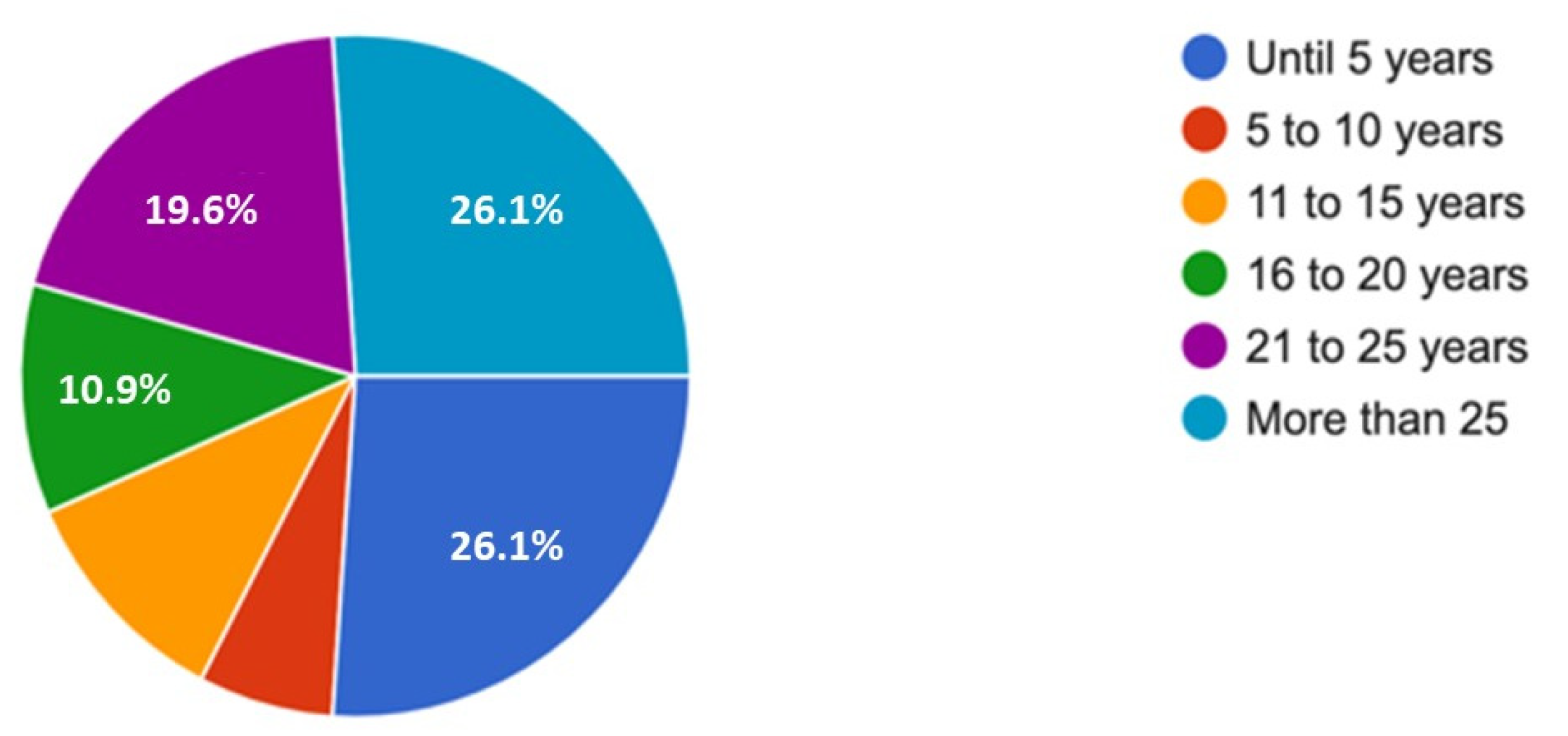

| 13 | In Figure 1, the lowest percentage in orange is 10.9% and in red is 6.5%. |

| 14 | In Portugal, the share of employment in creative and cultural sectors showed figures between 0.5% to 1%. Source OECD 2020 Regional statistics. |

| 15 | To further understand the simplified Lay-off, see the information on the Government website (Anonymous 2021c). |

| 16 | It must be underlined that all the conclusions of this topic are conditioned by the category’s segmentation (intervals of revenue defined in the survey to respect the privacy of the data). |

| 17 | The global sales of art and antiques down 22% from 2019 (McAndrew 2021, p. 17). In France, the primary art market sector also showed a down: a survey conducted by the Comité Professionnel des Galeries d’Art concluded for a total loss of 184 Million Euros between February and June 2020, and one-third of French art galleries were at risk of shutting down (Comité Professionnel des Galeries d’Art 2020). |

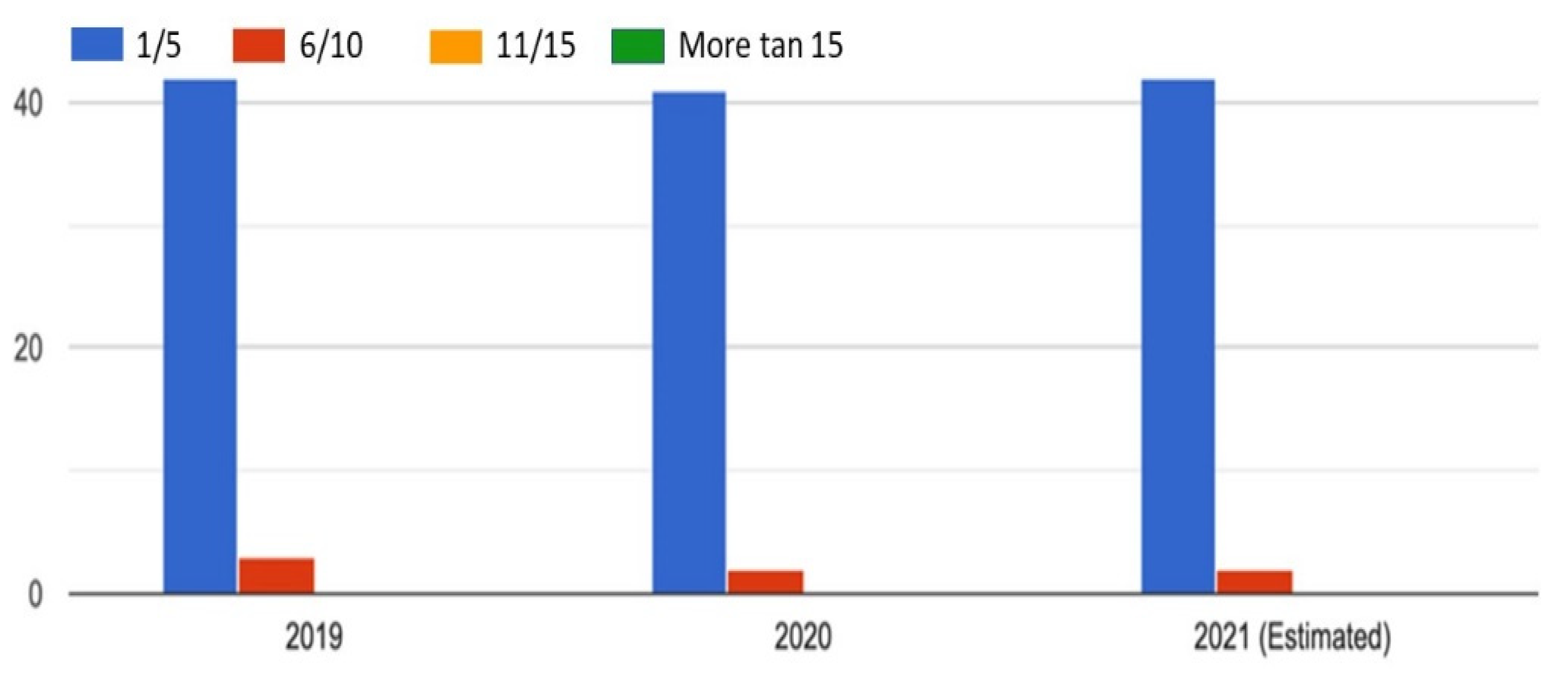

| 18 | These calculations were made using corrections for an estimation of 39 answers for each year. |

| 19 | Internationally, the mega-galleries tend to dominate online sales and to face the crisis easier. The pandemic will probably underline the gap between art market players (Xydas 2020, p. 37). |

| 20 | This information was given to the author by Bruno Múrias through telephone message in 28 April 2021. Plus, he confirms in-presence on 15 May, stating that it was worth it because he sold well. |

| 21 | The Portuguese Association of Art Galleries (APGA) existed already but lost activity; it is known that it was created a new association in 2019, named Exhibitio, but its activity is not known yet. |

| 22 | The Drawing Room Lisbon is focused on drawing and worked successfully for gallerists (Anonymous 2020b). |

| 23 | As previously said, the art fairs for primary markets in Lisbon are branches from Madrid, which reinforces the common market at the Iberian Peninsula. ARCOlisboa, the international art fair for contemporary art, was launched in 2016, as an initiative from IFEMA, a consortium formed by the Madrid Regional Government, the Madrid City Council, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Fundación Obra Social y Monte Piedad de Madrid, with the support of the Ministry of Culture, from Portugal, the Lisbon City Council, and the Portuguese Tourism. The JustLx, devoted to emergent art, is promoted by the Spanish company ArtFairs, and it had its first edition in 2018, in Lisbon, as an ARCOlisboa satellite art fair. |

| 24 | The new acquisitions, and the former collection, will be available among those institutions (apparently, in a political of decentralization scope). See Resolução de Conselho de Ministros n° 50/2021 (2021) (Diário da República n° 91/2021, Série I, 11 May 2021). Abstract: Cria a Rede Portuguesa de Arte Contemporânea e o Curador da Coleção de Arte Contemporânea do Estado (Creates the Portuguese Contemporary Art Network and the Curator of the State Contemporary Art Collection). |

| 25 | Acquisitions have been made annually by a commission, the first between 2016–2019, the second commission acted between 2019–2021 (Matos and Faro 2021). Besides artworks acquisitions, the Municipality launched a specific program for independent workers of the cultural sector, called the Social Emergency Fund. In this context, curators have applied, opening exhibitions in galleries (for example, in the Balcony Gallery). |

| 26 | According to Observatório Português das Atividades Culturais, circa half of artists and professionals of art and culture have a wage of EUR 600 per month, an amount close to the minimum wage (Neves et al. 2021a, p. 8). |

| 27 | Sara and André are a couple of artists who regularly exhibited from 2006. Their artistic practice brings together themes of appropriation, authorships, and criticisms of celebrity in the art world. For this project, inspired in a previous work by Julião Sarmento, from 1977, also named “Survey to 60 artists,” Sara and André surveyed 471 artists by email, addressing four questions about the COVID-19 representation, its impact on artists’ life and work, and how they see the future after the pandemic crisis. There is a published version with the number of participants (263) (Sara and André 2020b) and an online version: Sara and André (2020a). Inquérito a 471 artistas. Contemporânea. Available online: https://contemporanea.pt/edicoes/inquerito-471-artistas/inquerito-471-artistas (accessed on 17 May 2021). |

| 28 | The pandemic crisis showed the need for social protection to artists (and professionals of culture) and the implications it has in this legal frame. According to OPAC, 88% of the inquiries showed a discontinuity contributory career (Neves et al. 2021b). It is under public discussion until 17 June 2021: see the Decree-Law that approves the Statute of Professionals in the Area of Culture. Anonymous (2021d). “Decreto-Lei que aprova o Estatuto dos profissionais na área da cultura”. Available online: https://www.consultalex.gov.pt/ConsultaPublica_Detail.aspx?Consulta_Id=195 (accessed on 17 May 2021). |

| 29 | The idea is to have a monthly art fair, and artists apply to the platform to participate. Mercado P’la Arte also gives ateliers for free (Anonymous 2021e). Simultaneously, it is observed a growing number of collectivities of artists as a resilience strategy, a growth that should be followed in the future. |

| 30 | Although the reports provided by the professional associations IAC and Consortium of Contemporary Art Galleries lack an academic orientation and methodology, they offer data from the primary source par excellence, the galleries themselves and the professionals who manage them. In addition, the fundamental objective for the preparation of these reports during the pandemic was to offer a realistic vision of the situation the sector was going through, which is why we consider them sufficiently reliable for our analysis. |

| 31 | The abrupt closure of galleries in Spain has been referenced in the different reports on the Spanish art market that Dr. McAndrew has published since 2012. While in the 2012 report, an approximate number of 3500 registered art galleries is declared, in the following 2014 report, the number of registered galleries remains at slightly more than 2950, quite lower a figure than the data reflected two years earlier. |

| 32 | The Federal Government is led by the negationist president Jair Bolsonaro. The total of deaths reached 500.000 in June 2020, in the second position after the United States, as well as figured among the 10 countries with the higher percentage of deaths by millions of inhabitants. |

| 33 | Art market player, oral communication with the author, São Paulo, 4 June 2021. |

| 34 | In global market reports, these figures are more often estimates, based only on a fraction of the market, and projected to what is supposed to be the market as a whole. We were more interested in indicators to assess variation of business results than in getting an estimate or a fragile global figure. |

| 35 | Gallery owner, oral communication with author, São Paulo, 5 December 2020. |

| 36 | Gallery owner, oral communication with author, São Paulo, 4 May 2021. |

| 37 | This scenario contrasts, in Brazil, with other cultural sectors, such as the performing arts, which have been suffering irreparable losses and whose entrepreneurs and artists may not be able to go through the crisis and continue their activities in a post-pandemic context (Observatório do Itaú Cultural 2020; Fialho 2020). |

| 38 | Gallery owner, conversation with the author, 28 May 2020. |

| 39 | Latitude—Platform for Brazilian Art Galleries Abroad, is a project aiming the internationalization of the Brazilian Contemporary Art Market, an initiative by the Brazilian Association of Contemporary Art (ABACT) in partnership with the Brazilian Trade and Investment Promotion Agency (Apex-Brasil), using a combination of private and public funds. For more information: http://www.latitudebrasil.org/sobre-nos/apresentacao/ (accessed on 1 May 2021). |

| 40 | Export statistics show consolidated exports for commercial purposes and temporary exports for cultural purposes (participation in exhibitions, for example), so the volume of exports should not be confused with the volume of sales of works of art. In any case, the constant increase in the volume of exports in recent years points unequivocally to a greater international circulation of works of art, partly driven by the movement of art galleries. In 2019, exports surpassed the US$400 million mark, according to the Painel de dados do Observatório do Itaú Cultural, data available at: https://www.itaucultural.org.br/observatorio/paineldedados/ (accessed on 25 May 2021). |

| 41 | It is important to note that this is the average percentage in 2017; for example, for half of the respondent galleries, this percentage reaches 20%, and for a smaller group (eight galleries), 40% (ABACT/Latitude 2018). |

| 42 | In 2020, 23% of galleries surveyed reported sales to international institutions (in 2014, they were 21%; in 2017, 29%). Sales in 2020 were made to the following institutions: Perez Art Museum Miami, National Gallery of Modern Art New Delhi, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Contemporary Art Institute Chicago, Fundación Otazu/Spain, die Mobiliar Art Collection/Switzerland, Museum of Modern Art/New York, Dallas Museum of Art, Centre Georges Pompidou, Fundación Atchugarry/Uruguay. It is certainly not a complete list of institutions because some galleries did not respond to the request of information, but nevertheless, the partial information is sufficient to assess that Brazilian galleries keep reaching international institutions. |

| 43 | Latitude—Platform for Brazilian Art Galleries Abroad, is a project aiming the internationalization of the Brazilian Contemporary Art Market, an initiative by the Brazilian Association of Contemporary Art (ABACT) in partnership with the Brazilian Trade and Investment Promotion Agency (Apex-Brasil) using a combination of private and public funds. For more information: http://www.latitudebrasil.org/sobre-nos/apresentacao/ (accessed on 1 May 2021). |

| 44 | The engagement of artists in the production of digital content led some art market analysts to question the new role of galleries as content producers. The challenge to monetize this kind of content so far suggests that content production will remain a promoting activity rather than a new core business for the gallery sector, but this too early to be sure about it. Some galleries are trying to “sell” digital content, workshops and talks, and the majority offer them for free. |

| 45 | On the contrary, we recall that the global sales of art and antiques reached an estimated $50.1 billion in 2020, down 22% from 2019 (McAndrew 2021, p. 17). |

References

- ABACT/Latitude. 2012. Pesquisa Setorial Latitude. O Mercado de Arte Contemporânea no Brasil. São Paulo: Latitude. Available online: http://www.latitudebrasil.org/pesquisa-setorial/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ABACT/Latitude. 2013. Pesquisa Setorial Latitude. O Mercado de Arte Contemporânea no Brasil. São Paulo: Latitude. Available online: http://www.latitudebrasil.org/pesquisa-setorial/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ABACT/Latitude. 2014. Pesquisa Setorial Latitude. O Mercado de Arte Contemporânea no Brasil. São Paulo: Latitude. Available online: http://www.latitudebrasil.org/pesquisa-setorial/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ABACT/Latitude. 2015. Pesquisa Setorial Latitude. O Mercado de Arte Contemporânea no Brasil. São Paulo: Latitude. Available online: http://www.latitudebrasil.org/pesquisa-setorial/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ABACT/Latitude. 2016. Pesquisa Setorial Latitude. O Mercado de Arte Contemporânea no Brasil. São Paulo: Latitude. Available online: http://www.latitudebrasil.org/pesquisa-setorial/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ABACT/Latitude. 2018. Pesquisa Setorial Latitude. O Mercado de Arte Contemporânea no Brasil. São Paulo: Latitude. Available online: http://www.latitudebrasil.org/pesquisa-setorial/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Afonso, Luís Urbano, and Alexandra Fernandes. 2019. Mercados da Arte. Lisboa: Edições Sílado. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 2019. Cluster Art Market and Collection. Available online: https://ihapgmercado.weebly.com/cluster-amc.html (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Anonymous. 2020a. Galerias de Arte Afetadas Expressam Preocupação com os Artistas. Observador. April 6. Available online: https://observador.pt/2020/04/06/galerias-de-arte-afetadas-expressam-preocupacao-com-os-artistas/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Anonymous. 2020b. Artistas e Galerias Enfrentam Pandemia ‘Altamente Prejudicial’ para o Setor. Observador. November 28. Available online: https://observador.pt/2020/11/28/artistas-e-galerias-enfrentam-pandemia-altamente-prejudicial-para-o-setor/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Anonymous. 2021a. The Art Newspaper. COVID-19: Witch Countries Are Closest to Getting Back to Art Business? Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/analysis/covid-19-in-the-art-world-a-year-on (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Anonymous. 2021b. Mapa das Artes, Lisboa. Arte Contemporânea. Available online: https://mapadasartes.pt/ (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Anonymous. 2021c. Lay-Off Simplificado—Medidas Excecionais e Temporárias de Resposta à Epidemia Covid-19. Available online: https://www.dgert.gov.pt/covid-19-perguntas-e-respostas-para-trabalhadores-e-empregadores-faq/medidas-excecionais-e-temporarias-de-resposta-a-epidemia-covid-19 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Anonymous. 2021d. Decreto-Lei que Aprova o Estatuto dos Profissionais na Área da Cultura. Available online: https://www.consultalex.gov.pt/ConsultaPublica_Detail.aspx?Consulta_Id=195 (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Anonymous. 2021e. Mercado p’la Arte—A New Art Fair. Umbigo Magazine. April 15. Available online: https://umbigomagazine.com/en/blog/2021/04/15/mercado-pla-arte-uma-nova-feira-de-arte/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Anonymous. 2021f. A AAVP—Associação de Artistas Visuais em Portugal. Available online: https://aavp.weebly.com/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Apex-Brasil. 2021. Inteligência de Mercado. Painel de Comércio Brasil—Mundo. Available online: https://paineisdeinteligencia.apexbrasil.com.br/painel-covid-19.html (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Art Dealers Association of America. 2020. U.S. Art Galleries Project 73% Loss in Second Quarter Revenue Due to COVID-19 Developments. Available online: https://www.artdealers.org/sites/default/files/COVID-19%20Impact%20Survey%20of%20U.S.%20Art%20Galleries%20-%20FINAL_1.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Banks, Mark. 2020. The work of culture. European Journal of Cultural Studies 23: 648–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Howard S. 2010. Mundos da Arte. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte. First published 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2011. O Poder Simbólico. Lisboa: Edições, vol. 70, pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, Joana Amaral. 2018. Primeiro Ministro Anuncia Programa a 10 anos para Comprar Arte Portuguesa. Público. October 10. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2018/10/10/culturaipsilon/noticia/estado-vai-ter-programa-anual-para-comprar-arte-contemporanea-portuguesa-1847086 (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Comité Professionnel des Galeries d’Art. 2020. Impact de la Crise Sanitaire Covid-19 sur L’économie des Galleries D’art. Available online: http://www.comitedesgaleriesdart.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/cpga_cp_impact_crise_sanitaire_et_eco_sur_galeries.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Comunian, Roberta, and Lauren England. 2020. Creative and cultural work without filters: Covid-19 and exposed precarity in the creative economy. Cultural Trends 29: 112–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consorcio de Galerías de Arte Contemporáneo. 2020. Balance Económico de la Repercusión del Covid-19 en las Galerias de Arte Contemporâneo en España. Madrid: Unpublished Internal Document. [Google Scholar]

- Consorcio de Galerías de Arte Contemporáneo. 2021. Informe Sobre el Impacto de la Covid-19 en el Sector de las Galerias de Arte Contemporâneo en España, um año Después de Iniciaerse la Pandemia. Madrid: Unpublished Internal Document. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, Adelaide. 2020. The Periphery is beautiful. The rise of the Portuguese Contemporary Art Market in the 21st Century. Arts 9: 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmanhotto, Mônica, and Ana Letícia Fialho. 2020. Latitude Performance Report of Contemporary Art Galleries during the COVID-19 Pandemic. São Paulo: ABACT/Latitude. [Google Scholar]

- Estatísticas da Cultura, INE. 2019. Inquérito às Galerias de Arte e Outros Espaços de Exposições Temporários. Lisboa: Instituto Nacional de Estatística. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz, Marcos Grinspum. 2020. Um ano bom, ao Menos para o Mercado de Arte. Arte!Brasileiros, 21 de Dezembro de 2020. Available online: https://artebrasileiros.com.br/arte/reportagem/um-ano-bom-ao-menos-para-o-mercado-de-arte/ (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Fialho, Ana Letícia. 2019. Mercado de Arte Global, Sistema Desigual. São Paulo: Revista do Centro de Pesquisa e Formação, n° 9. [Google Scholar]

- Fialho, Ana Letícia. 2020. O iminente Colapso do Setor Cultural. Pandemia Evidencia os Limites das Iniciativas Privadas e Aumenta a Necessidade de Políticas Públicas Para a Cultura. Available online: https://www.select.art.br/o-iminente-colapso-do-setor-cultural/ (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Gerlis, Melanie. 2020. Art Market Report Shows the severe Impact of Covid-19. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/ff6530b4-1c40-497c-bd23-c5a70e552401 (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- IAC. 2020. Informe Sobre el Impacto Económico y Profesional de la Crisis del Covid-19 en Las/os Socias/os del IAC. Available online: https://www.iac.org.es/observatorio/comunicados-informes-acciones-iac/informe-impacto-covid-19.html (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Keh, Pei-Ru. 2021. Frieze New York 2021: The Highlights. Wallpaper. May 5. Available online: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/frieze-new-york-2021-preview (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Matos, Sara Antónia, and Pedro Faro. 2021. Flora. Aquisições do Núcleo de Arte Contemporânea da CML e do Atelier-Museu Júlio Pomar (2018–2020). Lisboa: Atelier-Museu Júlio Pomar. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, Clare. 2020. The Impact of Covid-19 on the Gallery Sector—A 2020 Mid-Year Survey. Art Basel & UBS Report. Basel: Art Basel & UBS. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, Clare. 2021. The Art Market 2020. Art Basel & UBS Report. Basel: Art Basel & UBS. [Google Scholar]

- Menger, Pierre-Michel. 2012. Être artiste. Oeuvrer dans L’incertitude. Bruxelles: Al Dante/AKA. [Google Scholar]

- Michalska, Julia, and Anna Brady. 2020. Galleries Worldwide Face 70% Income Crash Due to Coronavirus, Our Survey Reveals. The Art Newspaper. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/galleries-face-70-income-crash-due-to-the-coronavirus (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Ministerio de la Cultura y Deporte. 2020. Anuario de Estadísticas Culturales. Madrid: Ministerio de la Cultura y Deporte. Available online: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/dam/jcr:52801035-cc20-496c-8f36-72d09ec6d533/anuario-de-estadisticas-culturales-2020.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Miranda de Almeida, Cristina, and Benjamín Tejerina. 2020. El tercer espacio del arte. In En Riesgo. Diagnósticos, Propuestas y Luchas en Torno a la Precariedad del Arte Contemporáneo. Edited by Concepción Elorza Ibáñez de Gauna and Nerea Ayerbe. Madrid: Dyckinson, pp. 161–73. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin, Raymonde. 1989. Le Marché de la Peinture en France. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, pp. 40–41. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin, Raymonde. 2007. Mercado de Arte. Mundialização e Novas Tecnologias. Porto Alegre: Editora Zouk. First published 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Moureau, Nathalie, and Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux. 2006. Le Marché de L’art Contemporain. Paris: La Découverte. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, José Soares (Coord.), Rui Telmo Gomes, and Maria João Lima e Joana Azevedo. 2021a. Inquérito aos Profissionais das Artes e da Cultura: Report#2 Relações Laborais e Remunerações. Lisboa: Observatório Português das Atividades Culturais, CIES-Iscte. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, José Soares (Coord.), Rui Telmo Gomes, and Maria João Lima e Joana Azevedo. 2021b. Inquérito aos Profissionais das Artes e da Cultura: Report #3 Enquadramento na Segurança Social e nas Finanças. Lisboa: Observatório Português das Atividades Culturais, CIES-Iscte. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, José Soares. 2020. O sector artístico e cultural, impactos e desafios da crise provocada pela COVID-19, Renato Miguel do Carmo, Inês Tavares, Ana Filipa Cândido (Org.). In Um Olhar Sociológico Sobre a Crise COVID-19 em Livro. Lisboa: Observatório das Desigualdades, pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Observatório do Itaú Cultural. 2020. Dez anos de Economia da Cultura no Brasil e os Impactos da Covid-19. Available online: https://portal-assets.icnetworks.org/uploads/attachment/file/100687/EconomiadaCulturanoBrasileosImpactosdaCOVID-19_PaineldeDados_nov.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Pérez-Ibáñez, Marta. 2018. El Contexto Profesional y Económico del Artista en España: Resiliencia Ante Nuevos Paradigmas en el Mercado del Arte. Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ibáñez, Marta. 2020. Artistas, galerías y resiliencia ante la crisis. La génesis de nuevas tendencias y modelos de negocio en el actual mercado español del arte. In En Riesgo. Diagnósticos, Propuestas y Luchas en Torno a la Precariedad del Arte Contemporáneo. Edited by Concepción Elorza Ibáñez de Gauna and Nerea Ayerbe. Madrid: Dyckinson, pp. 175–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ibañez, Marta, and Isidro López-Aparicio. 2018. Art and Resilience: The Artist’s Survival in the Spanish Art Market—Analysis from a Global Survey. Sociology and Antropology 6: 221–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Quemin, Alain. 2002. L’Art Contemporain International: Entre les Institutions et le Marché. Le Rapport Disparu. Paris: Éditions Jacqueline Chambon ArtPrice. [Google Scholar]

- Quemin, Alain. 2013a. Les Stars de L’Art Contemporain. Notorieté et Consécration Artistiques dans Les Arts Visuals. Paris: Éditions du CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Quemin, Alain. 2013b. International Contemporary art Fairs in a ‘Globalized’ Art Market. In European Societies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Quemin, Alain. 2020. Can Contemporary Art Galleries be Ranked? A Sociological Attempt from the Paris Case. In The Sociology of Arts and Markets, Sociology of the Arts. Edited by Andrea Glauser. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 339–62. [Google Scholar]

- Resolução de Conselho de Ministros n° 50/2021. 2021. Lisboa: Diário da República n° 91/2021, Série I, May 11.

- Robertson, Ian. 2018. New Art, New Markets. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Roque, Mário. 2020a. O mundo Por Estes Dias (O Mercado da Arte e a Covid-19). Available online: https://visao.sapo.pt/exame/opiniao-exame/2020-03-31-o-mundo-por-estes-dias-o-mercado-de-arte-e-a-covid-19/ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Roque, Mário. 2020b. De Volta ao Mercado da Arte Com os Modernistas. Available online: https://expresso.pt/opiniao/2020-06-08-De-volta-ao-mercado-da-arte-com-os-modernistas (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Salema, Isabel. 2020. De Alexandre Estrela a Von Calhau: As Primeiras Compras do Estado com o Novo Fundo Para a Arte Contemporânea. Público. January 8. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2020/01/08/culturaipsilon/noticia/alexandre-estrela-von-calhau-primeiras-compras-estado-novo-fundo-arte-contemporanea-1899675 (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Saltz, Jerry. 2020. The Last Days of the Art World … and Perhaps the First Days of a New One Life after the Coronavirus Will Be Very Different. Available online: https://www.vulture.com/2020/04/how-the-coronavirus-will-transform-the-art-world.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Saltz, Jerry. 2021. Frieze and the Return of the Megafairs. Social Reentry, Sensory Overload, and Some very Good Art at the First Big Event Since … Well You Know When. Art Review. May 12. Available online: https://www.vulture.com/article/jerry-saltz-review-frieze-2021.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Sara and André. 2020a. Inquérito a 471 Artistas. Contemporânea. Available online: https://contemporanea.pt/edicoes/inquerito-471-artistas/inquerito-471-artistas (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Sara and André. 2020b. Inquérito a 263 Artistas. Special Issue. Lisboa: Contemporânea. [Google Scholar]

- Schiuma, Giovanni, and Antonio Lerro. 2017. The Business Model Prism: Managing and Innovating Business Models of Arts and Cultural Organisations. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 3: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Aubyn, Miguel. 2020. O Impacto Económico da Pandemia Covid-19 em Portugal. Madrid: Pensamiento Iberoamericano, n° 9 (Tercera Época), pp. 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Benjamin. 2021. What sold at Frieze New York 2021? Artsy. Available online: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-sold-frieze-new-york-2021 (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Velthuis, Olav, and Stefano Baia Curioni. 2015. Cosmopolitan Canvases. The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xydas, Fotini. 2020. The Art Market Response to a Global Pandemic. Citi GPS: The Global Art Market and Covid-19. Innovating and Adapting. Available online: https://www.privatebank.citibank.com/newcpb-media/media/documents/insights/Citi-GPS-Art-report-Dec2020.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Zarobell, John. 2017. Art and the Global Economy. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

| = = | NA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| After COVID-19 Galleries | |

|---|---|

| Kept the same team | 63% |

| There were dismissals | 18% |

| There were dismissals and hires | 12% |

| There were hires | 7% |

| Galleries in Brazil—Artists Representation | |

|---|---|

| Galleries that kept the same number of artists represented | 67.4% |

| Galleries that increased artists represented | 23% |

| Galleries that decreased artists represented | 9.6% |

| Galleries that changed the way they work with artists | 66% |

| Galleries that did not change the way they work with artists | 34% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duarte, A.; Fialho, A.L.; Pérez-Ibáñez, M. External Shocks in the Art Markets: How Did the Portuguese, the Spanish and the Brazilian Art Markets React to COVID-19 Global Pandemic? Data Analysis and Strategies to Overcome the Crisis. Arts 2021, 10, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030047

Duarte A, Fialho AL, Pérez-Ibáñez M. External Shocks in the Art Markets: How Did the Portuguese, the Spanish and the Brazilian Art Markets React to COVID-19 Global Pandemic? Data Analysis and Strategies to Overcome the Crisis. Arts. 2021; 10(3):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030047

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuarte, Adelaide, Ana Letícia Fialho, and Marta Pérez-Ibáñez. 2021. "External Shocks in the Art Markets: How Did the Portuguese, the Spanish and the Brazilian Art Markets React to COVID-19 Global Pandemic? Data Analysis and Strategies to Overcome the Crisis" Arts 10, no. 3: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030047

APA StyleDuarte, A., Fialho, A. L., & Pérez-Ibáñez, M. (2021). External Shocks in the Art Markets: How Did the Portuguese, the Spanish and the Brazilian Art Markets React to COVID-19 Global Pandemic? Data Analysis and Strategies to Overcome the Crisis. Arts, 10(3), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030047