Abstract

In the third quarter of the eighteenth century, Santo Domingo archbishop Isidoro Rodríguez Lorenzo (s. 1767–1788) issued a decree officializing the day of the cult for the Virgin of Altagracia as January 21 and made it a feast of three crosses for the villa of Salvaleón de Higüey and its jurisdiction, meaning all races (free and enslaved) were allowed to join the celebrations in church. Unrelated to the issuance of this decree and approximately during this time (c. 1760–1778), a series of painted panels depicting miracles performed by the Virgin of Altagracia was produced for her sanctuary of San Dionisio in Higüey, in all likelihood commissioned by a close succession of parish priests to the maestro painter Diego José Hilaris Holt. Painted in the coarse style of popular votive panels, they gave the cult a unifying core foundation of miracles. This essay discusses the significance of the black bodies pictured in four of the panels within the project’s implicit effort to institutionalize the regional cult and vis-à-vis the archbishop’s encouragement of non-segregated celebrations for her feast day. As January 21 was associated with a renowned Spanish creole battle against the French, this essay locates these black bodies within the cult’s newfound patriotic charisma. I examine the process by which people of color were incorporated into this community of faith as part of a two-step ritual that involved seeing images while performing difference. Through contrapuntal analysis of the archbishop’s decree, I argue the images helped model black piety and community membership within a hierarchical socioracial order.

1. The Signifying Event

“… We send the priest of said villa of Higüey, that from now on he does not allow… for the feast of Nuestra Señora de Altagracia to begin before or after 21 January. It is our wish that it is precisely that day, from now on and forever. And by the power of the faculties that we possess, we pronounce it a feast of three crosses in that villa and its jurisdiction…”1—Santo Domingo archbishop Isidoro Rodríguez Lorenzo, date unknown [my translation]

On 21 January 1691, the inhabitants of the eastern portion of the island of Santo Domingo (or Hispaniola), aided by the Spanish Armada de Barlovento, fought against the French over control of the entire island at the infamous Battle of la Limonade in today’s northwest Haiti, near Cap-Haïtien (then Güarico), and won an unlikely victory.2 Famed New Spanish creole Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645–1700) credited the win to the island-born contingent of machete-wielding “lanceros”, as well as to the “valorous” New Spanish reinforcements that arrived in the nick of time under the direction of Gaspar de Sandoval, the New Spanish Viceroy.3 Santo Domingo archbishop Fernando de Carvajal y Rivera (s. 1687–1700) did not credit any one particular saint or Marian advocation, but he did write about the battle to impress upon the Spanish king the worth of his subjects in Hispaniola. Back in the capital city of Santo Domingo, rallying for divine intercession, the miraculous image of the Santo Cristo de San Andrés was brought in procession to the cathedral and placed looking west, where the battle was to be fought.4 At the end of the eighteenth century, the victory battle was still a malleable narrative, with a number of authors attributing it to different divine forces. Luis Joseph Peguero, a cattle rancher from the rural villa of Baní, claimed in his Romanses (1762) that the victory was owed to the Virgin of Las Mercedes. There had been, according to sources, a lienzo (canvas) with the sacred image of Nuestra Señora de la Merced in the battlefield.5 Last but not least, the lanceros from cattle ranching regions, many allegedly from the villa of Salvaleón de Higüey in the eastern-most edge of the island, and who fought at la Limonade under Antonio Miniel, Captain of the Militias, appropriated the battle as a victory they had themselves effected through the help of the Virgin of Altagracia, a miraculous painted icon with her home sanctuary in Higüey.6 French Jesuit priest Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix likewise wrote that soldiers chanted the name of the Virgin of Altagracia in battle.7 Although no written declaration for this attribution survives, the pilgrimage to the sanctuary in Higüey to thank the Virgin every year since 1691, on or around January 21, is evidence that they believed this victory was owed to none other than their resident wonderworking icon.

The turning point for the definitive attribution of the victory came in the second half of the eighteenth century via a decree drafted by Santo Domingo archbishop Isidoro Rodríguez Lorenzo (s. 1767–1788), in which he officially declares the Day of the Virgin of Altagracia to be 21 January. Nicolás de Albor, treasurer for the sanctuary of Higüey, had written to the archbishop to complain that the festive crowds, especially from the interior, were dwindling since nobody knew exactly when the festivities began or ended. The archbishop penned the decree in response, officializing the cult day to prevent “hearts from turning cold” (entibiarse los corazones). Associating the cult to this important day pegged the Hispanic patriotism of the 1691 victory battle to the charisma of the Virgin of Altagracia. The painted icon was until that point not known for dispensing an exclusive type of miracle, such as protection against natural disasters, or known to privilege any one particular constituent group. That is to say, it did not have a specific charisma. Santo Domingo cathedral canon Gerónimo de Alcócer’s Relación sumaria de la Isla española (1650) attests there had long been an interisland pilgrimage to touch and kiss the painting, and a deposition of miracles had been made in 1569 to support the construction of the thatch-roof sanctuary into stone. Capuchin friar Cipriano de Utrera (1886–1958) speculated the icon had become popular because many travelers going to Puerto Rico from Hispaniola preferred to disembark from the Yuma river mouth in Higüey in order to avoid the more visible and dangerous port of San Diego in Santo Domingo. Travelers probably visited her sanctuary in town to dedicate a vow before boarding the pirate-infested waters of the Caribbean. Scholars agree that her cult (though not the painted icon, a Hispano-Flemish nativity) had arrived at the island with Governor of the Indies Nicolás de Ovando by 1503 (Figure 1). In an interesting twist that joins the beginnings of the story of the Altagracia cult in Hispaniola with the history of the Afrodiasporic experience in the Americas, Ovando built the first hospital of the Americas in Santo Domingo on the same spot where he found “a pious black woman” (negra piadosa) tending to the sick in a hut. He named the Hospital San Nicolás de Bari and its first chapel was dedicated to the Virgin of Altagracia.8

Figure 1.

Unknown, Virgen de la Altagracia, oil on panel, c. 1510–1515, Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Altagracia, Higüey, Dominican Republic. Used with permission from Obispado de Higüey.

The archbishop’s proclamation of the Virgin of Altagracia’s intercession in favor of a Hispanic victory “attained by those of this island” is one where people of color seemingly do not play a role.9 However, by reading the decree contrapuntally, we see that black presence and participation was fundamental to the decree’s goal of reenergizing the cult. That is, the decree’s chief concern with preventing “hearts from turning cold” was directly linked to the ability of the celebrations to amass a large number of people. Given that people of color were the demographic majority in the island, declaring the day a “feast of three crosses” (fiesta de tres cruces) in the liturgical calendar and freeing everyone from labor obligations would encourage wider participation.10 Regardless of whether it happened as planned, the decree wording was an acknowledgment that black presence in the celebrations was crucial to saving the cult from extinction.

Scholarship on the medallions merely describe the images as proto-costumbrista depictions typical of popular religious visual culture. This essay proposes to read their resonance against lived reality. Furthermore, this essay contributes to the dialogue on the role of miracle cycles and the creolization of blacks in the Spanish Americas. The work of María Elena Díaz on the Virgin of El Cobre in Cuba exposed how images of blacks as witnesses in miracles associated to thaumaturgic sites in the Americas were not as common as ones with Indians.11 As in the legendary story of the Virgin of Guadalupe and the indio Juan Diego, Indians were incorporated as “civilized” members of creole society, even when they asserted agency through claims of difference. A role in the narrative opened a path toward their “cultural mestizaje” in the late colonial period, as Díaz argues. In contrast, “slaves and blacks hardly ever appeared in [miracle] stories associated with major New World images and shrines. Even in the circum-Caribbean region, where the black population was larger, the absence of blacks from this religious genre is conspicuous.”12 The exclusion can serve as point of departure to explore the possibilities and limitations of the genre of the Marian miracle as a practice of social incorporation in the Americas.

This essay discusses the role of art in configuring a community of faith around creole patriotism, and how people of color gradually folded into that community. Creole patriotism refers to pride in being a descendant of Spaniards born in the Americas. “Creole” (criollo/a), in the context of this essay, refers to a Spanish subject, nominally white, and born in the Americas. According to David Branding, creole patriots were descendants of conquistadors who developed a consciousness in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries after the Indian encomienda system was faded out and they lost hopes of becoming a landed nobility.13 Creole clerics especially wrote histories and sermons that aggrandized their lands, holdings, and the local miraculous cults, with a view towards “transforming the colonies into kingdoms.”14 The realization of difference between the crown’s treatment of creoles and that of peninsulares (Spaniards born in the mainland) grew sharper as a result of the Bourbon reforms enacted by King of Spain Charles III (1759–88) which removed creoles from prominent government positions in the Americas. Blacks were in a precarious position because enslaved labor was the pillar on which the colonies were maintained, but crown, colony, and church (with its complex dynamic between the secular and regular clergy) did not always agree on the procurement and management of free and enslaved populations of color. Hispaniola was an interesting case because free blacks and castas outnumbered the enslaved since the mid-sixteenth century, and the issue of their control became a growing source of anxiety for the dominant classes. In this essay, we identify a ritual of incorporation of black bodies into a creole community of faith in late colonial Hispaniola that, while not intentional, addressed combined institutional needs. Welcomed into the sanctuary under a non-segregated feast of three crosses, people of color would potentially see images that reinforced in them pious behavior, a notion of their place in the socioracial hierarchy, and a sense of belonging as well as of deference to colonial authority. In addition, since the date was 21 January, the celebration would help instill in black subjects a patriotic zeal.

2. The Altagracia Medallions as Curatorial Project

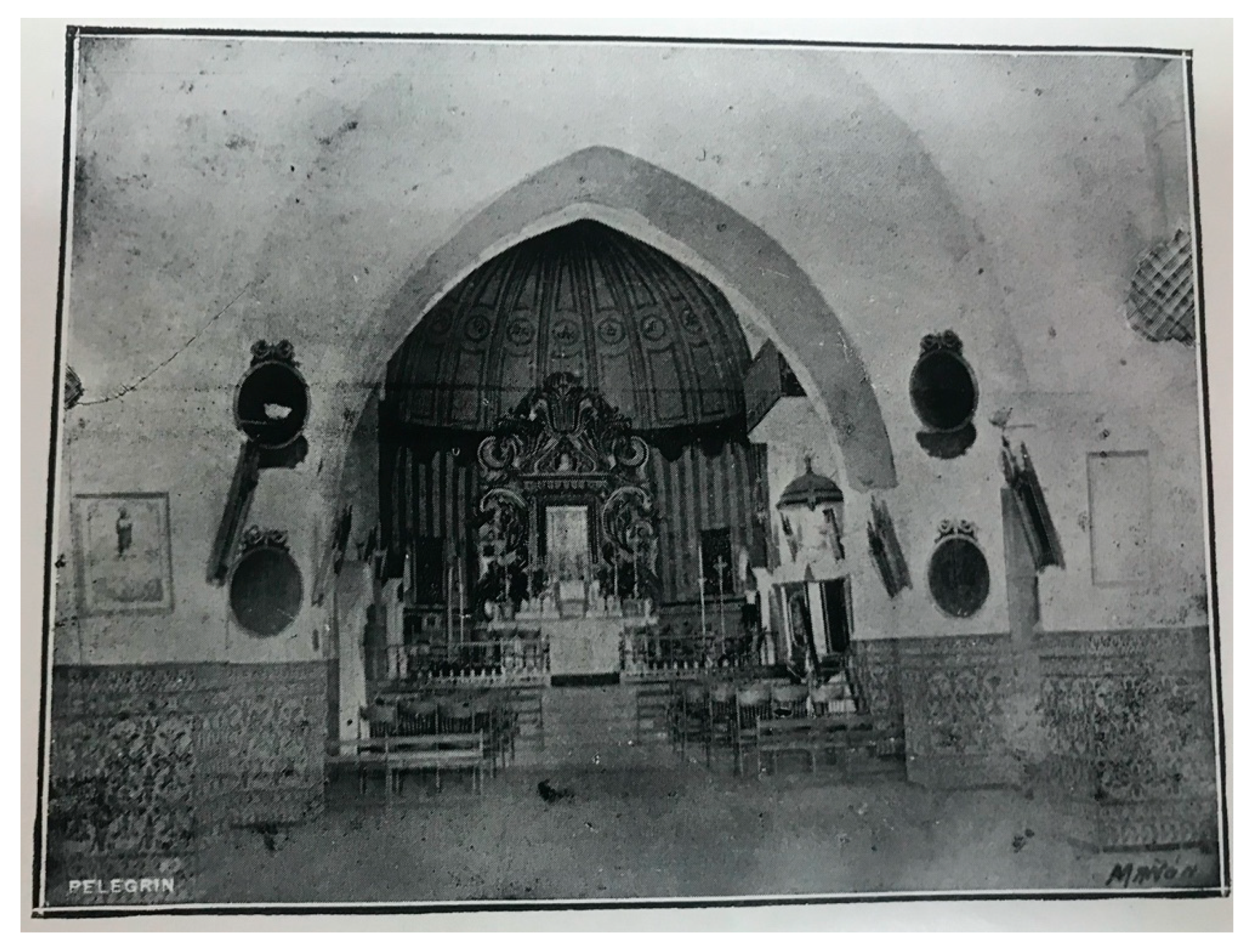

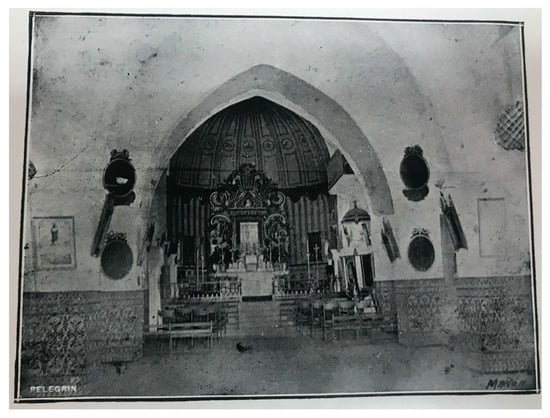

It is during the third quarter of the eighteenth century, specifically between 1760 and 1778 as attributed by Eugenio Pérez Montás, that a series of painted panels were produced for the sanctuary of San Dionisio in the villa of Salvaleón de Higüey depicting miracles performed by the Virgin of Altagracia.15 Although the earliest date they appear in sanctuary inventories is on 8 November 1861 as “twenty-seven retablos of oval shape, representing the miracles, all with golden fr… and adornments, except four that have them ar…” (veinte y siete retablos de forma ovalada, representando los milagros, todos con marc… y adornos dorados, menos cuatro que los tienen ar…) signed by Fr. Pedro Texidor and Delegate Mayor Andrés Páez, the iconography and dates of events depicted in the extant sixteen units confirm Pérez Montás’ attribution of 1760–1778.16 Picturing collective and individual miracle stories, sixteen panels survive in their entirety, with three additional ones for which only the lunettes survive.17 Only four lunettes were found intact, attached to medallions and with their original inscriptions. The missing lunettes were reproduced during restauration, and the matching texts found on period documents.18 On account of the rather large size of the medallions (2.5 ft height × 2 ft width, the largest one being 2.4 ft height × 3 ft width), the number of units, and the opulent and standardized frames, the series was meant to compete with, streamline, or substitute the numerous and no-doubt dizzying array of ex-voto and paintings on display at the sanctuary. It is unclear whether the painted mural votives that had covered the sanctuary walls since at least 1650 had been whitewashed yet.19 The medallions were part of an effort to build and maintain the painting’s reputation as a wonderworking icon by giving it a core foundation of miracles. This photograph taken from the album of the coronation of the Virgin of Altagracia celebrated in 1922 shows the medallions in situ in the early twentieth century (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A view of the main altar in the San Dionisio sanctuary, with Altagracia medallions displayed, c. 1923. Album de la coronación. Used with permission from Archivo Histórico Diocesano de Santo Domingo.

Scholars attribute Diego José Hilaris Holt as the painter of the series because he appears in one of the panels, dedicating the commissioned series to the Virgin for curing him from an ailment—and turning all the cycles, as Sergio Barbieri observes, into votive offerings.20 Hilaris Holt either worked in different time spurts or completed at one point a majority of the “recordatorios de prodigios”, as Barbieri calls them. The majority of the commission could have been helmed by (or realized within the orbit of) Spanish creole parish priest Ignacio de Alarcón, who performed in various capacities for the San Dionisio sanctuary at approximately the same juncture, including as sacristán mayor and rector.21 Alarcón, according to his relación de méritos, had been serving at the sanctuary from 1766 to 1788, and was pursuing a vacant canonry position in the Santo Domingo cathedral in 1789, but had been unsuccessful.22 For reasons that remain unclear, the archbishop interfered with his application, “stimulated by his conscience”, because in his estimation he was a subject who was “absolutely undignified because he is ignorant, unapplied, and of reprehensible customs…” The archbishop only kept him in the priesthood, he adds, “because there is nobody else to assign, and only because there is an aid that helps curb him.”23 Moreover, he adds, he has not confided this to the Cámara because “the experience shows him the inconveniences that follow.”24 The Altagracia medallions align with Alarcón’s recorded attempt at “edifying the parishioners” which would reinvigorate higüeyano pride, facilitated by a slight rise in wealth and population for the region. By 1783, however, Alarcón’s wish to move away from the rural villa was already evident in his pessimistic tone. In a report on matters of the sanctuary, dated 20 January 1783, Alarcón states that “in the last five years there has been no increase in population nor in culture and none is likely expected” (en este ultimo quinquenio ni de Poblacion ni de Cultura se ha experimentado augmento alguno ni probablemente se espera).25

Granted the title of Villa in 1508, Higüey was located in the southeastern-most corner of Hispaniola, and it was a very poor locale throughout the colonial period. Locals had long depended on the cult to the Virgin of Altagracia for basic survival (Figure 3). In 1598, when the Mercedarians threatened to take over the sanctuary to form an ecclesiastical province, locals wrote a letter to the Cabildo of the cathedral complaining that their livelihood depended on the pilgrimage economy.26 In 1600, to compel the crown to grant them enslaved workers for agriculture, the locals boasted about the prestige of the sanctuary and the cult. In the eighteenth century, the entire island experienced a growth in population. New villas were established with Spanish immigrants, fugitives kept arriving from neighboring Saint Domingue no doubt boosting population numbers, and Santo Domingo governor José Solano Bote, in 1771, negotiated an agreement to foment agriculture whereby Hispaniola received enslaved laborers from Saint Domingue in exchange for cattle, which stimulated the economy.27 The eastern region, comprising Higüey, El Seibo, Samaná, Sabana de la Mar, Bayaguana, and Monte Plata, with an economy of cattle-ranching and subsistence farming, grew more than 100% from 1742 to 1782–83.28 Higüey was a destination for many residents from the neighboring French colony of Saint Domingue who chose the farthest corner of the island to escape the generalized chaos after the revolution fires exploded in Cap-Français in 1791.29 In terms of demographics for late colonial Higüey, the information is inconsistent, but the nominally white (peninsular or creole) population, as well as the number of enslaved workers, was minimal. Higüey registered as of 1739, a total of “318 free and enslaved peoples, out of which ten or twelve were white, and the rest either black or mulatto.”30 One of the medallions reflects the notion that people of color outnumbered whites in Higüey. The medallion about the fire that broke out in the villa shows only black bodies around a light-skinned priest (Figure 4). The racialized discourse of the rural comes into focus when compared to the “Empty Chest” medallion, which depicts mostly white bodies in the urban space of the capital city of Santo Domingo (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

The villa of Salvaleón de Higüey is marked by the San Dionisio Sanctuary at the southeastern-most edge of the island. Map of Hispaniola by Andrés Morales, in Peter Martyr, De Orve Novo Decades, 1516. From Emilio Rodríguez Demorizi 1979, comp. Mapas y planos de Santo Domingo (1979), p. 5. Copyright: Editora Taller.

Figure 4.

The fire, Altagracia medallion, oil on panel, c. 1760–1778, Museo de Altagracia, Higüey. Used with permission from Museo de Altagracia.

Figure 5.

Empty chest, Altagracia medallion, oil on panel, c. 1760–1778, Museo de Altagracia, Higüey. Used with permission from Museo de Altagracia.

The standardized frames and the single-artist commission of the medallions reveals a concern with capturing the attention of parishioners and presenting to them a chronological and unified story. One of the medallions even says in the inscription: “and this was the first [miracle].”A pedagogical concern with clarity and brevity of sermons for the cognitive coherence of church goers was a constant concern, as mentioned in a pastoral visit by Antonio de la Concha Solano in 1740 to the San Dionisio sanctuary.31 Given the concern with clarity and brevity in sermons, it is possible to align the medallions with the tenets of post-tridentine reform in the Spanish colonies. It is highly likely that in Hispaniola, just as was done in nearby Colombia and in New Spain, the church published edicts on taking down votives, expressing the Vatican’s disapproval after the Council of Trent of the many distracting votives surrounding miraculous images and sculptures in thaumaturgic sites. In this regard it makes sense that the Altagracia medallions did not picture free-flowing apparition images of the Virgin on billowing clouds. She is shown as a painted icon, firmly secured on the sanctuary altar in a retablo, expressing a restraint in visionary iconography that aligned with sermons from Hispaniola creole and Jesuit priest and lawyer Antonio Sánchez Valverde (1729–c.1791). In a sermon Valverde gave in Madrid, he reprimands Christians for believing in false miracles while in the same breath defending the culto externo (exteriorized or unrestrained baroque piety) against the “unenlightened philosophes” of France and northern Europe.32

We can also explain the panels as a local visual history project that responded to the greater freedoms and motivations of Spanish colonial subjects to produce their own histories after the Seven Year’s War (1759–1763). England emerged as the superpower in the region, and Spanish creoles in the Americas were thus stimulated to reassess their colony-metropolis relations, strengthening or reimagining associations and loyalties. The earliest histories of Hispaniola written by creoles date from this period in the second half of the eighteenth century. The manuscript by cattle rancher Luis Joseph Peguero, La Historia de la Conquista de la isla española de Santo Domingo (1762), responds to what he viewed as a lack of information about the island in sources by early Spanish chroniclers who did not know the island first-hand. The historical essay by Antonio Sánchez Valverde, Idea del valor de la isla española de Santo Domingo (1785), is also revisionist in that it strives to educate the crown on the unexploited environmental and mineral wealth of the colony. However, we should not confuse the development of a creole consciousness with a separatist spirit. In fact, Valverde’s essay is the work of an enlightened creole who attempts to strengthen ties with Spain.33 That said, scholars locate the development of a Hispaniola creole consciousness much earlier, in the writings of archbishop Fernando de Carvajal y Rivera (s. 1687–1700) in the aftermath of the battle of La Limonade of 1691, when he famously complained to the crown that the poor islanders who had fought for Spain and delivered a win were not rewarded the same as the well-equipped Spaniards who had fought and lost in Flanders.34

The largest Altagracia medallion which reproduces one of the earliest and perhaps the foundational miracle (the “Empty Chest” legend) operates in a dual royalist and creole framework (Figure 5). It depicts the time when the icon was being transported to the Santo Domingo cathedral and it disappeared from the chest to return to its home sanctuary in Higüey. The Bourbon flag hoisted on the transporting canoe reifies the genealogy of the cult as Spanish in origin, regardless of where it moves, while the story about the icon resolutely returning to her home sanctuary in the villa of Higüey establishes the cult as one that is inextricably bound to the villa and its sanctuary.

Four out of the sixteen extant miracle cycles feature black bodies. This essay centers them to locate their place in a community of faith whose titular miraculous icon incorporated a creole patriotic charisma. They are featured acting in various capacities: as a domestic page, an oxcart puller, a drummer boy amid a community of people of color, and an enslaved laborer. Research has not been able to locate them in historical records and they are regarded as proto-costumbrista and accessorial depictions that paint a picture of everyday life. I argue they carried an important weight in the project, and constituted part of a collaborative effort between artist and a close succession of parish priests who culled miracles from different sources (oral memory, written records, and symbolic and representational votives), bringing them into the eighteenth century with period clothing and characters that increased credibility and functioned to a pedagogical effect. For example, in the cycle about a priest and vicar named Juan Domínguez who accidentally sat on a hammock and suffocated a child, the black domestic servant that acts as a witness was painted in despite the written legend not mentioning her presence (Figure 6). She appears very prominently, her red earrings matching the child’s red waistcoat and articulating a visual connection between the two. A similar story was listed in an Altagracia miracle deposition of 1569; but a “José” (not a Juan) Domínguez is recorded as priest in Higüey only in 1733.35 Thus, this type of accident was either a common occurrence throughout the colonial period and/or the 200-year-old deposition record served as inspiration for the parish priest and the artist’s development of this new miracle story.

Figure 6.

Child asphyxiation accident, c. 1760–1778, oil on panel, Museo de Altagracia, Higüey, Dominican Republic. Used with permission from Museo de Altagracia.

The foregoing reflections were prompted by a desire to articulate a context for the combustive moment in which Afrodiasporic peoples, officially welcomed into the sanctuary under the feast of three crosses, encounter their images. If the medallions were on display before, do black and mixed-race church goers see the images in a new light? The fact that the medallions were a curated project, made to be on display and to engage with a viewing public, positions it as a project that marked the advent of modern visual culture and viewing practices in the island.36 The birth of a new viewing public was taking place in Europe in the late eighteenth century in the secular realm via exhibition practices in salons and galleries. Gabriel de Saint Aubin’s depiction of the Salon of 1767 and Johann Zoffany’s The tribuna of Uffizi (1772–78) portray this initiation in taste in Paris and Florence, respectively. But modernity and its institutions, as Pamela Voekel argues, often had religious origins.37 While black representation lends a sense of local flavor and truthfulness to the accounts in the Altagracia medallions, they also served as mirrors that could allow black viewers to see themselves reflected in this foundational story. Seeing the images within a public congregation that welcomed them in prefigured the democratizing social and civic experience of visiting museum and gallery exhibition halls.

3. Oval Frames and Memorialization

Except for the “Empty Chest” panel which follows conventions for urban images of the Hispanic world as studied by Richard Kagan, the Altagracia cycles reproduced traditional votive panel prescriptions as defined by Lenz Kriss-Rettenbeck, which included four visual elements: the inscription, the asking person, the event or accident, and the spiritual entity.38 However, the Altagracia medallions are not votive paintings per se.39 As mentioned earlier, the medallions were part of a single, top-down curatorial project, and were not commissioned or deposited by individual miracle beneficiaries. The costly gilded frames represented an extraordinary commission out of reach for most non-institutionally-backed donors. Different from the square frame serving as a window to an extended past-present, the oval frame expresses a concern with memorializing the past. Taking Erving Goffman’s notion literally in Frame Analysis (1974) that frames are “cognitive structures that guide perception”, we posit that the Altagracia medallion frames themselves were important producers of knowledge.40 Popularly called “medallions” because they resemble the fashionable brooch pins worn by society ladies in colonial times, the Altagracia miracle cycle series boasted Louis XVI-style carved giltwood oval frames with a ribbon bow at the pediment possibly crafted from the emerging wood industry that Rudolf Widmer has studied.41 Gilded frames were items that could be produced in the island considering the Santo Domingo governor Francisco Rubio did not hesitate to order some “marcos dorados” (gilded frames) for a pair of royal portraits that had just arrived from Cádiz. The portraits were meant for display at the Sala de Audiencia of Santo Domingo.42 Similar ribbon bow gilded frames surround the portraits of the twelve apostles in the sacrament chapel at the Santo Domingo cathedral, which scholars date to the end of the eighteenth century (Figure 7).43

Figure 7.

Images of the apostles (a–d). Francisco Velásquez, medallions, end of 18th century, oil on panel, Cathedral of Santa María la Menor, Santo Domingo. From Arte Sacro Colonial en Santo Domingo (2002), p. 48. Copyright: Fundación de la Zona Colonial, Inc. 2002.

The Altagracia medallions engage in a type of memorialization practice that played on their form and materiality. As corporeal objects expected to hang on walls they evoked the stability of built infrastructure, while the cartouches or lunettes that labeled the images direct the viewer to surrender any interpretative attempt. Moreover, ovals, recalling the contour of the human face, help carry forth messages of propaganda, from commemorative medals that solidified empires to the miniature medallion portraits that advertised and rekindled long-distance romantic affections.

This memorialization practice was a global phenomenon in the eighteenth century, performed for a wide range of purposes that included generating official versions of a story. Witness this practice in the façade of the Palazzo Salvadori in Trento, Italy. This was a Renaissance urban palace that commenced construction in 1515 on the grounds of an old Jewish synagogue. Two marble medallions by the sculptor Francesco Oradini (1698–1754) were added to the façade in the mid-eighteenth century to commemorate the rumored infanticide of Simon of Trent (Figure 8). Simon had disappeared in Easter of 1475 and the Franciscans believed he had been the victim of a ritual killing perpetrated by the Jewish. Many Jews were tortured and executed as a result, and Simon became a miraculous saint with a large cultic following.44 It is quite telling that the medallion format involved in generating authoritative versions of tales is also associated to the miracle-making industry. This makes one wonder whether miracle claims were an alluring endpoint to community disputes, since, as unexplainable phenomena, miracles offered an opportunity to end the discussion with no need for further deliverance of proof.

Figure 8.

Francesco Oradini, medallion depicting the imagined martyrdom of Simon of Trent, marble, mid-eighteenth century, Palazzo Salvadori, Trento, Italy (Created by Andreas Caranti, CC BY-SA 2.0).

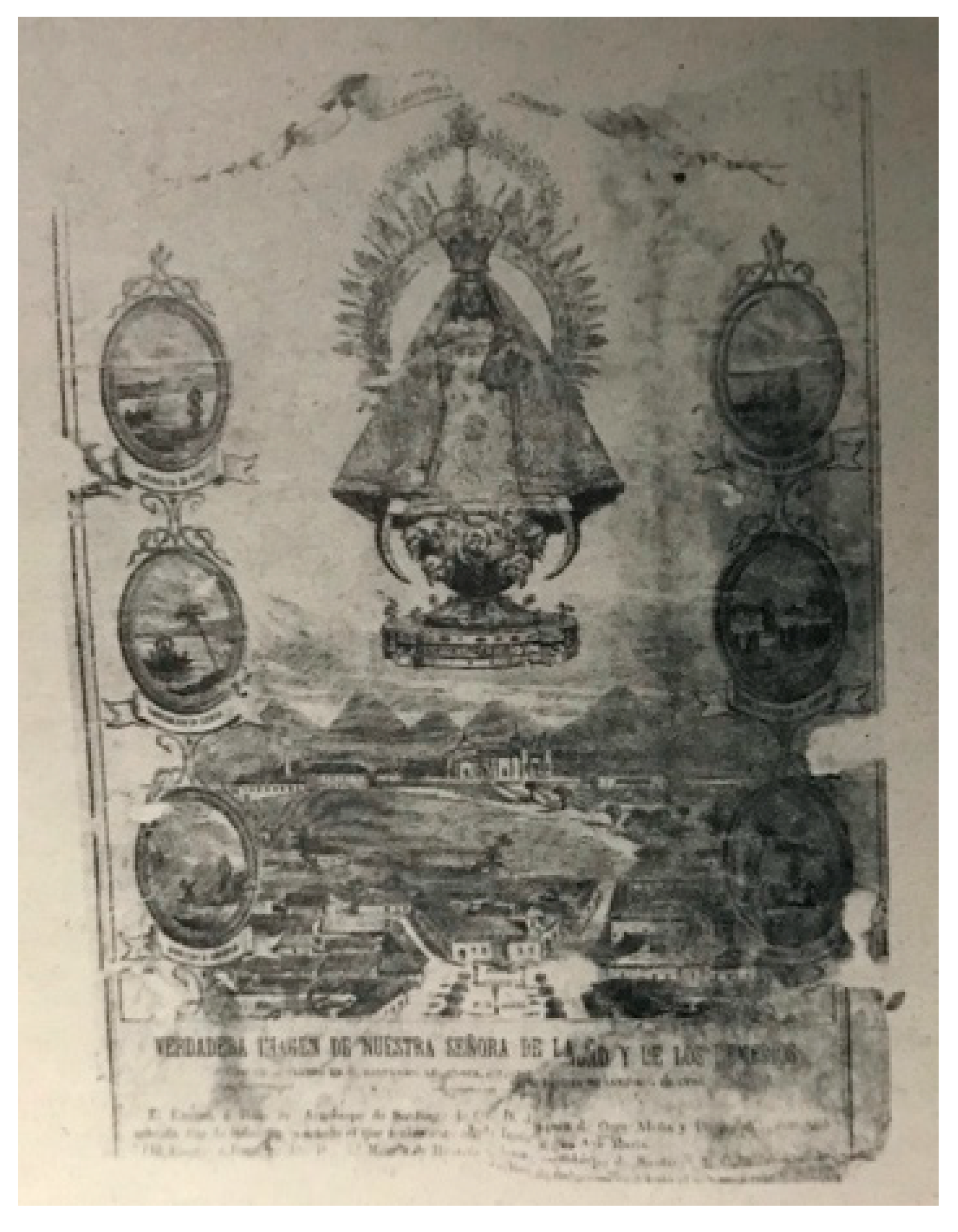

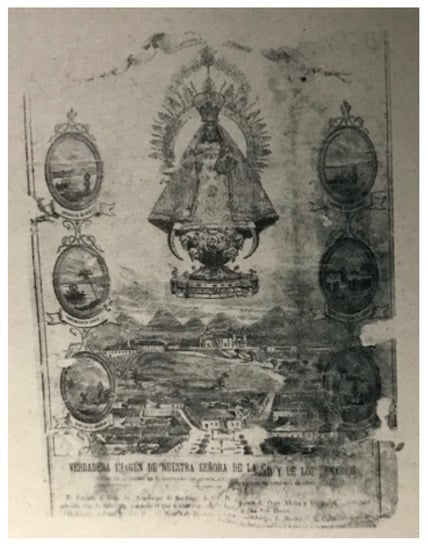

Closer to home, the Altagracia medallions are remarkably similar to another memorialization practice documented in Cuba between 1792 and 1823, or earlier. The first broadsheet ever created for the Virgen de La Caridad del Cobre features six miracle vignettes surrounding an effigy of the Virgin, all floating above a bird’s-eye-view of the rural village of El Cobre (Figure 9).45 The six miracle vignettes are shown framed in a style strikingly similar to the Altagracia medallions: mounted in oval frames with a legend scroll at the bottom and a decorative molding crowning the top.

Figure 9.

Nuestra Señora de la Caridad y de los Remedios, c. 1792–1823, Cuba. Image reproduced from Olga Portuondo Zúñiga 1995, La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre: Símbolo de Cubanía (1995).

Bishop Osés Alzua (1792–1823), a bishop for Santiago (the eastern region of Cuba), commissioned the printing of the broadsheet of the Virgin as El Cobre demanded privileges for their political designation as villa and toiled to rehabilitate its mines. Bishop Osés Alzua championed progress and free trade for the eastern region, which had been economically relegated by Habana and the metropolitan authorities, and he energetically supported the popular cult of the Virgin of La Caridad del Cobre.46 Although we do not know the precise dissemination context for the broadsheet, its commission issues from a desire to institutionalize the miraculous history of the Virgin of La Caridad del Cobre and to promote its site-specificity in order to raise the profile of the eastern provinces of Cuba. Independently of whether the medallions were actually produced, the broadsheet with the representation of the medallions indicates they played a role in cult promotion and in a community’s formulation of political–spatial claims.

4. The Miracle of the Enslaved Mute: Black Piety and Community Membership

“Matías de Meneses visited this shrine on 7 February 1756. He brought a 33-year-old slave born mute [sic]. After praying the third of the Rosary he spoke and requested Matías a license to get married. The master [sic], understanding that it was a trick played by the devil, asked [the enslaved person] to pray the Hail Mary, which he performed so clearly and exceptionally that everyone understood it. Witnesses to this miracle were Manuel Hormas de Melo and Alonso Hidalgo and sister Mariana, and they praised the Lord.”—Inscription of an Altagracia medallion, c. 1760–1778, Museo de Altagracia, Higüey (my translation)

One of the Altagracia medallions depicts the story of a man born mute, who, on a visit with his enslaver in 1756 to the San Dionisio sanctuary in Salvaleón de Higüey miraculously regained his voice and petitioned for authorization to marry (Figure 10).47 In the panel, Matías de Meneses, a creole slaveowner, kneels while facing the painted icon of the Virgin of Altagracia and presenting to her a black man, prostrated by his side. This image pictures black personhood (being able to speak) as an outcome of the Christian civilizing mission; attainable through the mediation of the creole master, who is positioned in between the enslaved mute and the Virgin’s painted icon. The panel models the type of deference and docility expected of people of color inside the San Dionisio sanctuary in Salvaleón de Higüey.48

Figure 10.

Enslaved Mute, Altagracia miracle medallion, oil on panel, c. 1760–1778, Museo de Altagracia, Higüey, Dominican Republic. Used with permission from Museo de Altagracia.

The Código negro carolino of Santo Domingo (henceforth the Black Code), although never enacted into law, was commissioned in 1783 to Santo Domingo court judge Agustín Ignacio Emparán y Orbe as Spain was readying to liberalize the slave trade in 1789.49 Emparán received feedback from hacendados, clerics, and colonial authorities, and drafted the document in eight months. The Black Code recommendations aimed at making both free and enslaved blacks better agricultural workers, and religious education was prescribed to this effect. Learning the Christian Doctrine would make of people of color “honest, laborious, and reasonable beings… adapted to the colonial system… and root out pride and arrogance.”50 One medallion depicts a black oxcart puller, reflecting a common occupation among black subjects, one which they were encouraged to take up. The Black Code can be read as a guide to the mentality of colonial agents who struggled with managing blacks, especially in rural and dispersed settlements.

The acculturation potential of black bodies is a visual marker that can be found in the surviving religious paintings of enslaved peoples in the Spanish Caribbean: José Campeche y Jordán’s Exvoto de la Sagrada Familia (Exvoto of the Holy Family), 1778–80, in Puerto Rico, and José Nicolás de Escalera’s Familia del Conde de Casa Bayona (Family of the Count of Casa Bayona) (1770’s), in Cuba (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The black subjects in José Campeche’s Exvoto de la Sagrada Familia kneel behind a figure that commands authority and acts as a portal to hallowed space, just as the enslaved mute and Matías de Meneses in the Altagracia medallion (Figure 11). The kneeling Carmelite nun is pictured facing a vision of the Holy Family, closely followed by three possibly enslaved servants, decorously dressed, who carry her flower offerings.51 While the work was probably commissioned for private, devotional use given its portable size, the composition of blacks ushered into the Christian community speaks to a conventional mode of representation. The three figures bearing flowers gain integrity through the mediation of the nun, who introduces them to the holiest of companies. Their dignified representation, with gracious attire that de-emphasizes their laboring condition, visualizes the possibility of their transition into Christian civilization.52

Figure 11.

José Campeche y Jordán, Exvoto de la Sagrada Familia, oil on wood, 18th century. Colección del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña.

Similarly proposing that the attainment of personhood follows attachment to an authority figure who mediates integration into the Christian community is José Nicolás de Escalera’s Familia del Conde de Casa Bayona (Family of the Count of Casa Bayona) (Figure 12). The image was painted for the Santa María del Rosario church, in what had formerly been the Bayona family’s property outside of Havana in Cuba. In the lower right margin we find the image of an enslaved black man sitting in a pose that evokes, as Agnes Lugo-Ortiz points out, an enlightened thinker. It is a flattering depiction that deviates from European conventions of slave portraiture.53 The slave, who had helped the Count of Bayona heal from gout, has apparently been rewarded for his loyalty by being represented in this family portrait.54 The image is one of four canvases in the pendentives located below the dome of the church, and tells the story of the origin of the rosary. According to the legend, the Virgin gave the rosary to Santo Domingo de Guzmán, the founder of the Dominican order, in a miraculous apparition. The Dominicans played a vital role in the Christianization of the Americas and, as Lugo-Ortiz expounds, the image of the enslaved man sitting reverentially under a sculpture of Santo Domingo, whose book opens directly to his face, is not casual. The composition speaks critically to issues of “language and conversion, and of the spiritual transformation of subjectivity through the introjection of “the Word.”55 In other words, as the slave learns to read the Bible, surely joining in public recitation of the rosary, he becomes whole.

Figure 12.

José Nicolás de Escalera, Familia del Conde de Casa Bayona (Family of the Count of Casa Bayona), 1770’s. Oil on canvas. Church of Santa María del Rosario, Cuba. Photo by Ramsés Hernández Batista. Courtesy of Agnes Lugo-Ortiz.

These works picture black personhood as the outcome of the Christian civilizing mission, attainable through the master’s mediation. Taken together, they form a discrete archive on the Catholic indoctrination of blacks and its relation to the achievement of a first-rate, if nominal, personhood. The works also open paths to seeing the different negotiations between church and colony in the Spanish Caribbean as the creole dominant classes struggled, to different degrees, with reproducing plantation economies á la Saint Domingue.

Within the memorialization project of the Altagracia medallions, it is possible to find spaces of black autonomy as they overlay onto the broader narrative of a Spanish colonial origin story.56 In the “enslaved mute” panel, literary analysis can help us make out spaces of agency in the black man’s intent to marry and in his utterance of a Hail Mary in Castilian. On the one hand, slave marriage increasingly occupied the minds of Bourbon-era colonial reformers because of the mobility it afforded free and enslaved people of color. An enslaved laborer could relocate to the spouse’s plantation and their children potentially escalate in social status if the spouse was a liberto(a) (a manumitted free person of color). Enslaved subjects would sometimes sue if not granted authorization to marry, while others would bypass permission altogether.57

Church and colony disagreed over how to handle slaves and the institution of marriage. While the church demanded that the sacrament of marriage among slaves be respected, colonial agents largely refused.58 Bourbons had addressed marriage laws for Spanish subjects from the peninsula and the colonies in the “Pragmática Sanción para evitar el abuso contra matrimonios desiguales” in 1776, but blacks and castas were overlooked until a revision was published in 1803.59 In Hispaniola, marriage between enslaved blacks and liberto(a)s as well as interracial marriage was a very big bone of contention between the colonial government and the church.60

Chapter 26 of the Black Code promoted slave marriage on the basis of procreation and slave appeasement, reasoning that “the scarcity of blacks in the coasts of Guinea, Senegal, and others, will make them more exceptional and expensive to purchase, which made it urgent [to] promote their marriage, the most suitable method to curb their escape and soften their harsh lot and condition” (emphasis my own).61 No male slaves would be denied permission to marry, save if it was with a female slave who lived outside the plantation. The Altagracia panel with Matías de Meneses and the enslaved man can be read in dialogue with this historical juncture when colony and metropolis recognized the need to reconcile the terms for slave marriage.

Moving on to a second space of black autonomy in the “enslaved mute” panel, speaking Castilian in orthodox form or as the legend suggests, “clara y distintamente” (clearly and exceptionally), was a way of performing Hispanic belonging. According to Fr. José Luis Sáez in his La iglesia y el negro esclavo en Santo Domingo: una historia de tres siglos (1994), “in the Spanish Caribbean, ladino designated the black subject born in Spanish territory who spoke Castilian with fluidity, while bozal was the newcomer from Africa who, after the first year in the colony still spoke with glitches in an Afro-Hispanic patois.”62 Speaking without a perceptible foreign accent allowed the black slave to fashion him or herself in the colonial world as native or creole, a step up in the social ladder.

One documented instance of a person of color fashioning a sense of belonging to a Hispano-Catholic community via her recitation of words of Scripture took place in Santo Domingo between 1684 and 1695. A black woman, despaired upon seeing her friend jailed, looked for, and presumably uttered or threatened to utter, the biblical words of the consecration, causing so much anxiety in the vicar-general that he sent her to prison.63 In uttering those powerful words, the black woman fashioned her Hispano-Catholic belonging perhaps as a form of reproach or as a way to claim spiritual protection for herself and for her jailed friend. Underpinning the anxiety of colonial society at large was no doubt the realization that people of color could master the Castilian language and Catholic praxis to the point where they could subvert them at will. This subversion took the form of lawsuits and witchery.64

Having identified these spaces of autonomy in the enslaved mute’s utterance of a prayer in Castilian and in his potential negotiation of mobility through the institution of marriage, the Altagracia panel now emerges as counter-dialogue to the grand memorializing project of the entire Altagracia panel series in which black subjects are not featured as conscious witnesses and narrators of miracles. It is as if a different story developed in between word and image, over and against the background of the official narrative. Mikhail Bakhtin’s (1895–1975) notion of “heteroglossia” is helpful here to consider how the enslaved man’s recitation of the Hail Mary in Castilian symbolically competes with the echo of the inscriptions on the medallion lunettes. Just as the black woman in Santo Domingo endeavored to utter the words of the consecration to claim protection, so does the enslaved mute recite out loud a Hail Mary claiming a safe haven, a belonging to the creole community based on practices he had learned to master. Sensorially, the black man’s voice pierces through as competing testimony. Bakhtin coined the term heteroglossia from the Greek “other” and “speech” for his work on the genre of the novel in 1934. The term refers to the “different kinds of speech or other signs, the tension between them, and their conflicting relationship within one text.” 65 Seeing the word-image relations in the Altagracia medallions as utterances that compete as testimonials allows us to pick up on muted agencies for a type of record that entangled the legal and religious practice of delivering testimony.

5. “To Prevent Hearts from Going Cold”: Presence and Representation at the San Dionisio Sanctuary

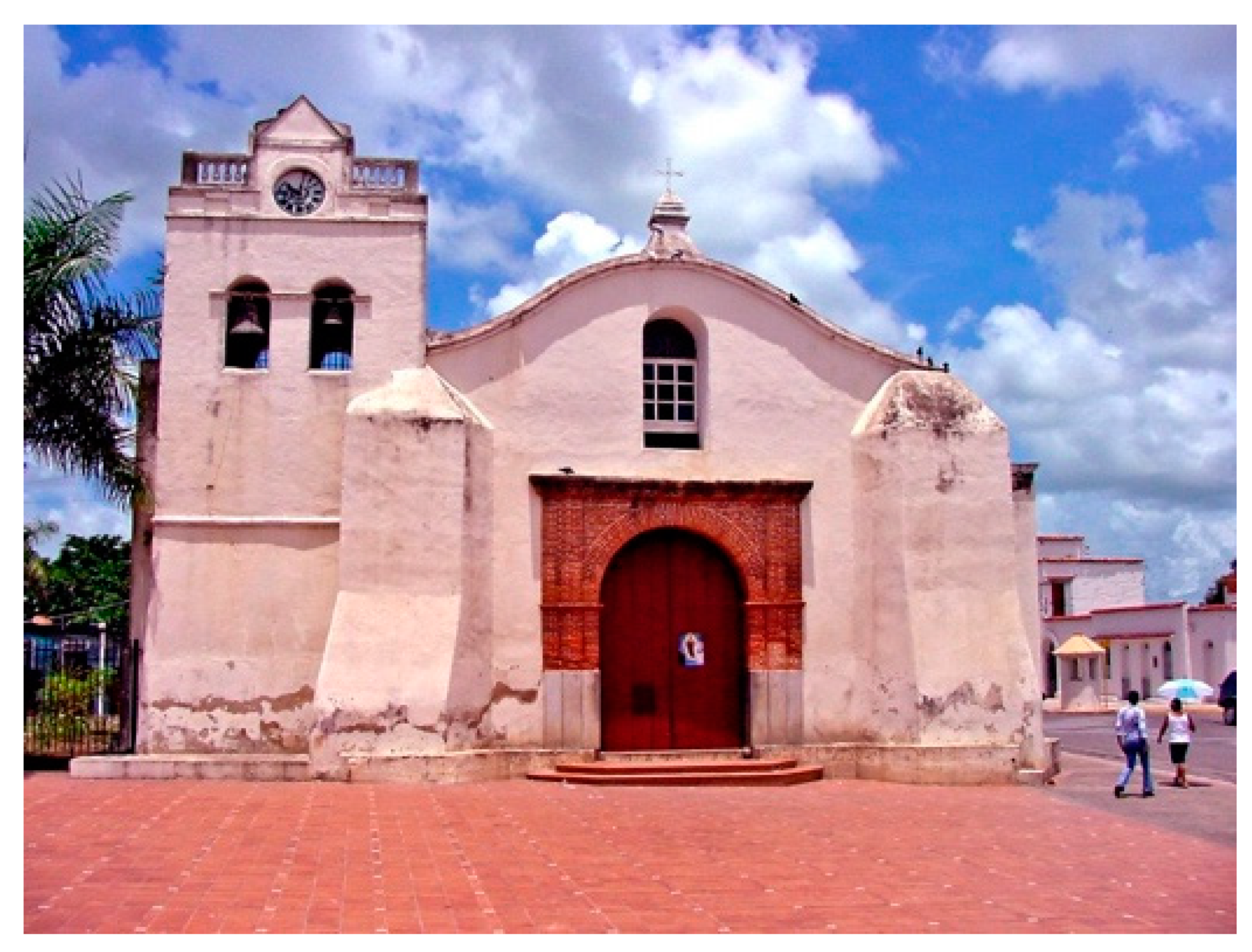

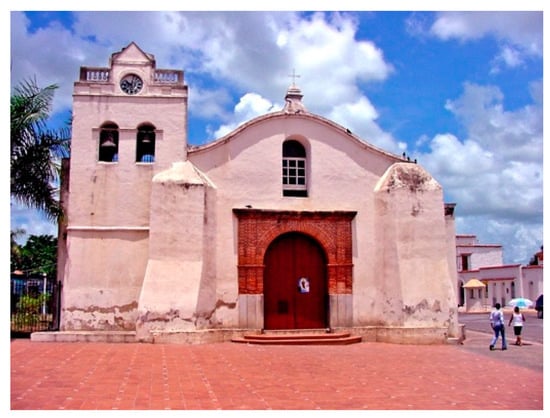

The decree of Santo Domingo archbishop Isidoro Rodríguez Lorenzo was discovered by capuchin friar Cipriano de Utrera (1886–1958) as a single manuscript sheet inside a chaplaincy record book of the parish of Bayaguana.66 The decree is invoked in altagraciano scholarship as the document responsible for the change of the cultic day of the Virgin of Altagracia from 15 August to 21 January. It is not studied, however, in relation to the archbishop’s decision to make said day a fiesta de tres cruces, which mandated non-segregated celebrations and thus supported the decree’s aim of revitalizing the cult. To “further stimulate the will of the faithful” (para más excitar el ánimo de los devotos), those in attendance would receive eighty days of indulgences each time they adored with devotion the Virgin’s miraculous icon, and eighty more days for each time they prayed a Hail Mary.67 The sanctuary of San Dionisio was the center of life in the villa of Salvaleón de Higüey, as it was the only stone and brick building amidst a sea of thatch-roof huts or bohíos (Figure 13).68 Celebrating at the sanctuary under the call for a desegregated congregation, racial dynamics otherwise intact, people of color would have probably gazed with an ambivalent heart at the Altagracia medallions. While they were marginally included as part of the cult’s foundation story, the situation magnified the gap between the ubiquitous black presence in Hispaniola and its meager representation.69 In perfect orchestration, the archbishop’s decree welcomed black presence while the medallions reinforced in black viewers a notion of their place in a socioracial hierarchy, a model of pious behavior, and a sense of deference to authority. What is more, since the date was 21 January, the celebration would help instill in black subjects a patriotic zeal.

Figure 13.

San Dionisio sanctuary, 1572, Higüey, Dominican Republic. Image created by Josue Collado, https://www.pbase.com/image/65323407, accessed 11 June 2021.

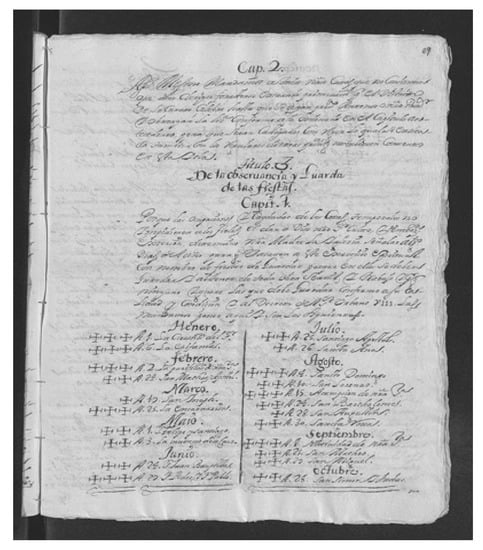

In remembering the battle of La Limonade, where Spanish creoles fought in the name of Spain against French incursion and won, celebrants reinscribed the cult with patriotic charisma and produced what Maurice Halbwachs termed “collective memory.” That said, the feasts of three crosses under which the celebrations would take place would be to the immediate detriment of hacendados, given the great number of feast days that already freed slaves from work. Hacendados argued that resources were stretched too thin in the island, and that they already worked “shoulder to shoulder” with the enslaved in the fields. One of those interviewed for the report in the Black Code lamented that, although his majesty had managed to get Pope Benedict XIV to issue the Venerabiles Fratres on 15 December 1750 to reduce the number of feast days, Santo Domingo archbishop Fray Ignacio de Padilla (s. 1743–1753) declared that slaves were exempt and that the Breve did not revoke privileges which they still enjoyed under the one issued prior by Paulo III (Subimis Deus in 1537).70 He went on:

“The excessive fiestas that slaves have during the day are, I believe, the reason for the backlog of work in the haciendas, since there are now 93 yearly, and only 6 favor the slavemaster, which are the ones named fiestas de una cruz…71—Antonio Mañón, Black Code, 1784.

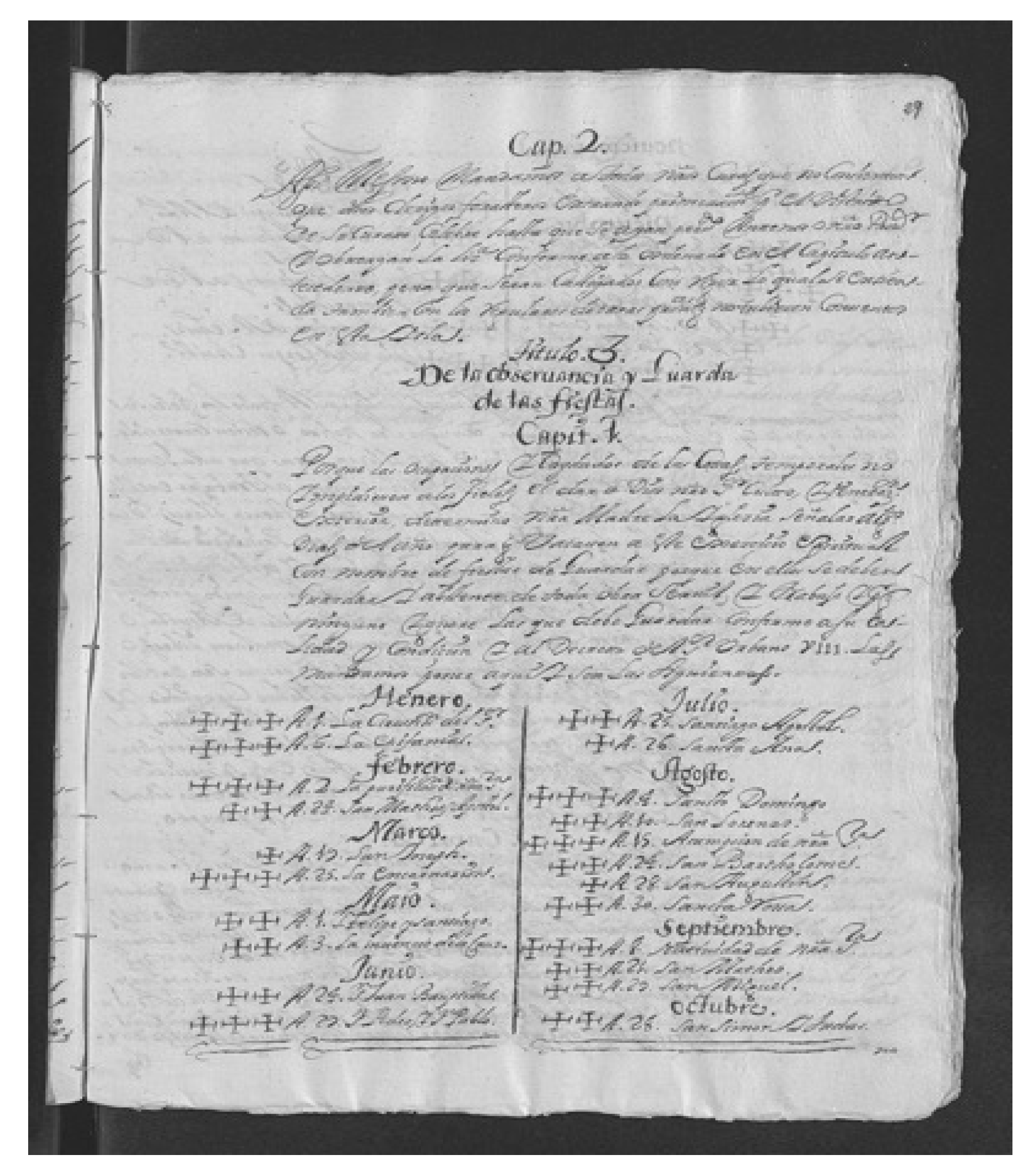

Feasts in the liturgical calendar could be marked with one, two, or three crosses, which designated which socioracial groups could attend a service and thus upheld scales of socioracial difference.72 A large number of church festivities marked for Hispaniola as early as 1683 were feasts of three crosses (Figure 14). Out of 31 religious holidays, 12 were tres cruces, 17 were dos cruces, and five were of una cruz. The synod of Santo Domingo of 1683 cites a legitimation based in ancient tradition that supported the celebration of feast days. There were so many weekly vigils, feasts, and fastings that notices needed to be read on Sunday mass after the offertory to remind parishioners. In Santa Bárbara and Ciudad de Santiago, tenientes curas were additionally mandated to print and publish these notices so that people had no excuse for not attending.

Figure 14.

Liturgical calendar with feast days in Hispaniola as of 1683, “Titulo 3. De la Observancia y guarda de las fiestas”, in Proemio Yquicion de la Sancta Synodo, Folio VI, Number 247 to 301 (1683 to 1699), Santo Domingo 93, Archivo General de Indias. Used with permission from Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. Archivo General de Indias.

Regardless of the hacendados’ displeasure with the great number of feasts of three crosses exempting the enslaved from work, these were tools that maintained the hierarchical system underwriting the success of enterprises operating with enslaved labor. Under the feasts of three crosses, a multicultural group would congregate in the same church and perform their difference, thus learning codes of subordination in embodied experience.73 The regimen of feasts in addition produced the mechanisms with which to enforce codes of subordination. Sermons could be crafted to target audiences, with specific information delivered to slaveowners when their slaves were not present, and vice-versa. The number of crosses that designated groups did so according to a mutating idea of race that addressed the experience of colonialism. While Pope Paul III’s Breve of 1537 dedicated two-cross masses generically to “blacks, mulattos, and slaves,” the 1683 Synod of Santo Domingo made the designation more specific, writing in “indios and mestizos, blacks from Angola or from any part of Oriental India, and free or enslaved mulattoes of the city of Santo Domingo because they were very capable.”74

The feasts of one, two, and three crosses described a stratified pyramid whereby the people targeted under the feasts of one cross (the nominal whites) were at the top of the echelon, the people designated under the feasts of two crosses followed in rank, and the feasts of three crosses collected the lowest tier of society. The feasts of three crosses joined all groups, but instead of desegregating, these cultural markings reinscribed difference, reinforcing the proposals of the Black Code aimed at “separating the races.” The invention and the reworking of the definition of race was common currency at the moment. In the last quarter of the eighteenth century, as scientific enlightenment sought ways to legitimate transatlantic slavery, the idea of race was being disentangled from ethnic membership and construed on biological terms. The Hispaniola creole Luis Joseph Peguero, in his Historia de la conquista (1762), covers events in Hispaniola from 1701 to 1762, and includes a summary of racial typologies in the island, reflecting an encyclopedic concern with classifying and building a racial imaginary.75

The Black Code tried to separate free and enslaved people of color to disrupt the mutual aid relations that existed among them:

“I see the need for the Code to include all the classes of blacks, giving them their respective place in the laws, because if we only legislate on the slaves, the problem would still persist because of all the relations and correspondence [mentioned before].”76

The code expressed calls to disrupt relations between enslaved, maroons, and free people of color living in the city of Santo Domingo and in the campos de haciendas, mandating it was illegal for either to lodge or feed one another. There was a call to contain all the city blacks in Santo Domingo’s Santa Barbara church since people of color affirmed their differences in the festivities they celebrated through brotherhoods (cofradías). Records from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries confirm the establishment in the Santo Domingo cathedral of the brotherhoods of the Holy Spirit, Saint Cosme and Saint Damian, Our Lady La Candelaria, Saint Mary Magdalene, and Saint John the Baptist.77

6. Conclusions

The Altagracia medallions are a curated project that prefigured the democratizing and civic experience of viewing images in congregation in public gallery and exhibition halls in Hispaniola. They represent a recollection of the major miracles performed by the Virgin of Altagracia of Salvaleón de Higuey, and some of them include black bodies. As people of color were officially welcomed into the San Dionisio sanctuary to celebrate the Altagracia feast day in a non-segregated manner, and as these subjects encountered these images, how did they perceive them? Does the invitation lead these subjects to see themselves as part of the cult’s foundation story, or does the invitation emphasize the ironic need of black presence to reenergize the cult? While we cannot speculate, this essay creates a context for this potentially combustive moment of encounter. Analyzing the images iconographically, we see how they model black piety and community membership. The images communicated that creole masters were the intermediators with the divine, and that black personhood could be achieved through them. Moreover, the black bodies are depicted performing historically sanctified occupations for people of color and, in this way, reinforce their productive roles in the economy as the Bourbons attempted to form the perfect black agricultural laborer. The ritual of seeing the images and performing difference at the sanctuary on the feast day of the Virgin of Altagracia becomes part of the spectacle of crafting a proto-citizenship during the age of the Hispanic enlightenment in the Caribbean. It was a ritual of incorporation into colonial society that, albeit arbitrarily, addressed the need of the colony, the church, and the metropolis to balance black presence and representation in Hispaniola.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation, the International Dissertation Semester Research Fellowship from the Graduate School at Florida State University, and by the Penelope Mason Dissertation Travel Award from the Department of Art History at Florida State University.

Acknowledgments

Images are courtesy of the Museo de Altagracia and Obispado de Higüey, Archivo Histórico Diocesano de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, and Centro Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museología. Thank you to the anonymous reviewers and editors of this special issue of Arts, the conferences where this paper was allowed to mature, and to my advisor Paul Niell for his insights and encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Audiencia de Santo Domingo. 1684–1695. Santo Domingo. Seville: AGI, vols. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Audiencia de Santo Domingo. 1695. Santo Domingo. Seville: AGI, vols. 93, November 22. [Google Scholar]

- Audiencia de Santo Domingo. 1744. Santo Domingo. Seville: AGI, vols. 319, July 7. [Google Scholar]

- Audiencia de Santo Domingo. 1744–1752. Santo Domingo. Seville: AGI, vols. 942. [Google Scholar]

- Audiencia de Santo Domingo. 1789. Consultas y providencias eclesiásticas. In Santo Domingo. Seville: AGI, vols. 1104, January 26. [Google Scholar]

- Audiencia de Santo Domingo. 1683–1699. Proemio yquicion de la Sancta Synodo. In Santo Domingo. Seville: AGI, vols. 93, pp. 247–301. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, Sergio. 2012. Los Medallones: 16 pinturas del siglo XVIII. Santo Domingo: Editora Búho. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, Carlos Larrazábal. 1998. Los negros y la esclavitud en Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo: Librería La Trinitaria. [Google Scholar]

- Bossy, John. 1983. The Mass as a Social Institution, 1200–1700. Past and Present 100: 29–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, Mark. 1975. Relaciones de méritos y servicios: A source for Spanish-American Group Biography in the Eighteenth Century. Paper presented at the Second Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies, Saint Louis University, Baguio, Philippines, October 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano de Utrera, Fray. 1933. Nuestra Señora de Altagracia: Historia documentada de su culto y su Santuario de Higüey. Santo Domingo: Padres Franciscanos y Capuchinos. [Google Scholar]

- De los Santos, Danilo. 2003. Memoria de la Pintura Dominicana: Raíces e Impulso Nacional. Santo Domingo: Grupo E Leon Jiménez. [Google Scholar]

- De Sigüenza y Góngora, Carlos. 2002. Carlos de Sigüenza y Gongora: Obras históricas. Ciudad de México: Editorial Porrúa. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, Carolyn. 1999. Inka Bodies and the Body of Christ: Corpus Christi in Colonial Cuzco, Peru. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, María Elena. 2002. The Virgin, The King, and the Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba, 1670–1780. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edward, Erika Denise. 2020. Hiding in Plain Sight: Black Women, the Law, and the Making of a White Argentine Republic. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Natalie, Ben McCann, and Peter Poiana. 2015. The Doubling of the Frame–Visual Art and Discourse. In Framing French Culture. Adelaide: University of Adelaide. [Google Scholar]

- Fleury, John. 2006. Historia de Nuestra Señora: La Virgen de la Altagracia. Santo Domingo: Editora Corripio. [Google Scholar]

- Folger, Robert. 2011. Writing as Poaching: Interpellation and Self-Fashioning in Colonial “Relaciones de méritos y servicios”. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación de la Zona Colonial, Inc. 2002. Arte Sacro Colonial en Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo: Amigo del Hogar. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero Castro, Francisco. 2011. Origen, desarrollo e identidad de Salvaleón de Higüey. Santo Domingo: Editora Nacional. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández González, Manuel. 2002. La vida cotidiana de un pueblo de bohíos: Higüey en el siglo XVIII. Paper presented at the Encuentro Internacional Arquitectura Popular en el Medio Rural: Las Casas Pajizas, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain, October 31–November 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández González, Manuel. 2008. El Sur dominicano (1680–1795) Tomo I: El Sureste. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Ediciones Ideas. [Google Scholar]

- Hontanilla, Ana. 2015. Sentiment and the Law: Inventing the Category of the Wretched Slave in the “Real Audience” of Santo Domingo, 1783–1812. Eighteenth-Century Studies 48: 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irisarri Aguirre, A. 2003. El informe del obispo Joaquín de Óses y Alzúa: Un intento ilustrado de promocionar el oriente cubano. Temas Americanistas. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Vyacheslav. 1999. Heteroglossia. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 9: 100–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Fredricka. 2013. Tavolette votive: Form, Function, Context. In Votive panels and popular piety in early modern Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 22–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann, Joseph A. 1986. The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum sollemnia). Translated by Francis A. Brunner. New York: Benziger, 2 vols. pp. 1951–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, Richard. 2000. Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kriss-Retenbeck, Lenz. 1972. Ex voto: Zeichen, Bild und Abbild im christlichen Votiv-Brauchtum. Zürich and Freiburg-im-Breisgau: Atlantis. [Google Scholar]

- Lora, Quisqueya. 2012. Transición de la esclavitud al trabajo libre en Santo Domingo: El caso de Higuey (1822–1827). Santo Domingo: Academia Dominicana de la Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Ortiz, Agnes. 2013. “Between Violence and Redemption: Slave Portraiture in Early Plantation Cuba”. In Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World. Edited by Lugo-Ortiz Agnes and Angela Rosenthal. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 201–226. [Google Scholar]

- Magin, Christine, and Falk Eisermann. 2009. Two Anti-Jewish Broadsides from the Late Fifteenth Century. In The Woodcut in Fifteenth-Century Europe. Edited by Peter Parshall. Washington: Studies in the History of Art, vol. 75, pp. 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Malagón Barceló, Javier. 1974. Código negro carolino (1784). Santo Domingo: Editora Taller. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Alier, Verena. 2009. Marriage, Class and Color in Nineteenth Century Cuba: A Study of Racial Attitudes and Sexual Values in a Slave Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- More, Anna. 2013. Baroque Sovereignty: Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora and the Creole Archive of Colonial Mexico. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Memén, Fernando Antonio. 2010. El indio y el negro en la visión de la iglesia y el estado en Santo Domingo (Siglos XVI–XVIII). Revista de Historia de América 143: 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Polanco Brito, Hugo E. Exvotos. 2010. Promesas y Milagros de la Virgen de la Altagracia. Santo Domingo: Banco Central. [Google Scholar]

- Portuondo Zúñiga, Olga. 1995. La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre: Símbolo de Cubanía. Havana: Oriente. [Google Scholar]

- Rípodaz Ardanaz, Daisy. 1977. El matrimonio en Indias: Realidad social y regulación jurídica. Buenos Aires: Fundación para la Educación, la Ciencia, y la Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Demorizi, Emilio. 1979. Mapas y planos de Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo: Editora Taller. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Demorizi, Emilio, ed. 2008. Relaciones Históricas de Santo Domingo Volumen I. Santo Domingo: Sociedad Dominicana de Bibliófilos. [Google Scholar]

- Román Fernández, Mercedes, and Javier Martín Silva. 2000. Una muestra literaria del siglo XVIII como testimonio de una realidad en las antillas españolas: La sociedad de castas. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, Cuaderno dieciocho, vol. 1, pp. 283–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, Máximo, Jr. 1994. Praxis, historia y filosofía en el siglo XVIII: Textos de Antonio Sánchez Valverde (1729–90). Santo Domingo: Np. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez, Jose Luis. 1994. La Iglesia y el Negro Esclavo en Santo Domingo: Una Historia de Tres Siglos. Santo Domingo: Amigo del Hogar. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Mery, Moreau. 1944. Descripción de la parte española de Santo Domingo. Translated by C. Armando Rodríguez. Santo Domingo: Editora Montalvo. [Google Scholar]

- Salmoral, Manuel Lucena. 1995. El texto del segundo código negro español, también llamado carolino, existente en el archivo de indias. Estudios de Historia Social y Económica de América 12: 267–324. [Google Scholar]

- Seed, Patricia. 1988. To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: Conflicts over Marriage Choice, 1574–1821. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla Soler, María Rosario. 2008. Santo Domingo: Tierra de Fronteras (1750–1800). Escuela de Estudios Hispanoamericanos: University of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, Hilary K. 2016. “Donated before the Gods: Popular Display of Edo-Period Ema Tablets”. In Exvoto: Votive Giving Across Cultures. Edited by Ittai Weinryb. New York: Bard Graduate Center. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, Doris. 1993. Foundational Fictions: The National Romances of Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, René. 1988. José Campeche y su tiempo. Austin: Museo de Arte de Ponce. [Google Scholar]

- Twinam, Ann. 1999. Public Lives, Private Secrets: Gender, Honor, Sexuality, and Illegitimacy in Colonial Spanish America. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde, Antonio Sánchez. 1783. Sermones panegíricos y de misterios. Madrid: J. Ibarra. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde, Antonio Sánchez. 1785. Idea del valor de la Isla Española y utilidades que de ella puede sacar su monarquía. Madrid: Pedro Marín. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Ugarte, Rubén. 1956. Historia del Culto de María en Iberoamérica y de sus Imágenes y Santuarios más celebrados. Madrid: Talleres Gráficos. [Google Scholar]

- Voekel, Pamela. 2002. Alone Before God: The Religious Origins of Modernity in Mexico. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Widnmer Sennhauser, Rudolph. 2001. El Higüey en el siglo XVIII. Los inicios de la industria maderera en Santo Domingo (1780–1800). Estudios Sociales 34: 123. [Google Scholar]

- Wisnoski, Alexander III. 2014. It is Unjust for the Law of Marriage to be broken by the Law of Slavery: Married Slaves and their Masters in Early Colonial Lima. Slavery & Abolition. A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies 35: 234–52. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The decree was transcribed by friar Cipriano de Utrera (1886–1958). See (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, pp. 85–88). However, no citation is offered, and thus the original decree has not been located. |

| 2 | Primary sources on this battle are at the Archivo General de Indias (AGI) in Seville, in files Santo Domingo 65. Also, see De Sigüenza y Góngora 2002. |

| 3 | See De Sigüenza y Góngora (2002) and More (2013). |

| 4 | De Sigüenza y Góngora 2002, p. 141. |

| 5 | De Sigüenza y Góngora 2002, p. 143. |

| 6 | According to Utrera, the villa of Higüey made a vow to celebrate the date after 1691. See (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 84). |

| 7 | (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 85). Other authors who attributed the victory for Altagracia include Fr. Le Pers and Valverde. See Rodríguez Demorizi (2008) p. 25. |

| 8 | The anecdote survives in a letter that Santo Domingo archbishop Fernando de Carvajal y Rivera sent to King Charles II on 2 December 1695 in response to the King’s solicitation of information on the establishment of the hospital. See files at the Archivo General de Indias (AGI) in Santo Domingo 93. |

| 9 | (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 85). |

| 10 | See the demographic study by CUNY’s The First Blacks in the Americas project, last accessed 30 May 2021, http://firstblacks.org/en/summaries/demographics-01-long-term-growth/. |

| 11 | In Vargas Ugarte (1956) Amerindians are common protagonists. |

| 12 | See (Díaz 2002, p. 97). |

| 13 | Cañízares-Esguerra (2002), p. 206. |

| 14 | Ibid. |

| 15 | Danilo de los Santos cites Hugo Polanco Brito, María Ugarte, and Eugenio Pérez Montás, who go by dates on the legends and the historical episodes they allude to. Pérez Montás especifically puts them between 1760 and 1778. See De los Santos 2003, pp. 65–67. |

| 16 | The inventories of the San Dionisio parish are at the Archivo Histórico Diocesano de Santo Domingo. |

| 17 | (Barbieri 2012, p. 72). |

| 18 | Monseñor Fr. Bernardino de Milia, Capuchin, secretary of the apostolic delegate visited the sanctuary in 1879 and transcribed all the legends from the sanctuary’s “memorias” and exvotos. See Utrera, “Compendiosa relación del estado del santuario y parroquia de Higüey y de su archivo, hecha el 8 de diciembre por el párroco Eugenio Polanco” Nuestra Señora, (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 55). |

| 19 | Gerónimo de Alcócer, a canon at the Santo Domingo cathedral, wrote Relación sumaria de la Isla española (1650), where he states that the sanctuary walls were full of votive murals. The manuscript was discovered at the Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid and transcribed by María Ugarte in 1941. |

| 20 | (Barbieri (2012), p. 9). |

| 21 | Cipriano de Utrera lists Ignacio de Alarcón as sacristán mayor in Higüey since 1761, and as rector from 1765 to 1787. See (Cipriano de Utrera 1933). |

| 22 | Relaciones de méritos y servicios were bureaucratic letters of support to obtain a reward or a merced from the crown. These were either written by the individual in question or by an endorser. A canonry at the metropolitan cathedral had vacated, carrying a stipend (prebenda) of 824 pesos annually. Ignacio Alarcón was suggested as second choice to the Cámara de Indias in a relación de mérito dated 26 January 1789. It read: “Mr. Ygnacio Alarcón, 34-year-old American presbytery, of legitimate birth. He has served for three years the chaplaincy for the Hospital de Santo Domingo, the Sacristy at the villa of Higüey in the same archbishopric, and in 1766 he obtained priesthood [serving in Higüey] on the suggestion of the Cabildo, a position which he continues with zeal, activity and to educate his parishioners. [My translation]. See Audiencia de Santo Domingo 1789, 26 January 1789. On using Relaciones de méritos as source for Spanish colonial research, see Folger 2011 and Burkholder 1975. |

| 23 | See Audiencia de Santo Domingo 1789, 26 January 1789. |

| 24 | Audiencia de Santo Domingo 1789, 26 January 1789. |

| 25 | (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 49). |

| 26 | This had also happened in Camagüey, Cuba, where Mercedarians wanted to form a convent in an Altagracia shrine. See Fleury 2006, p. 62. |

| 27 | (Valverde 1785, p. 116, and Lora 2012, p. 28) |

| 28 | (Sevilla Soler 2008, p. 44). |

| 29 | (Hernández González 2002, p. 165). |

| 30 | This according to a pastoral visit by Santo Domingo archbishop Domingo Alvarez Abreu. Primary sources providing demographics on late 18th c. Higüey are unreliable, but they coincide in their tally that castas and blacks far outnumbered white creoles and peninsulares, and that the enslaved workforce was minimal. Sources include: (Valverde 1785; Saint-Mery 1944; Guerrero Castro 2011; Hernández González 2008; Sevilla Soler 2008; Hernández González 2002; Widnmer Sennhauser 2001). Also, Ignacio de Alarcón reports in 1783 a total of 508 parishioners for the sanctuary. See (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 50). |

| 31 | (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 41). |

| 32 | Sánchez Valverde 1783, p. 139–97. |

| 33 | See (Rossi 1994). |

| 34 | Audiencia de Santo Domingo 1695, 22 November 1695. |

| 35 | See (Polanco Brito 2010, p. 107). |

| 36 | I was inspired by Hilary K. Snow’s work on ema tablets from Edo-Japan. She argues that object size, display site and practice, and donation context are important factors that marked their transition from religious artifacts into objects for visual-artistic consumption. See (Snow 2016). |

| 37 | (Voekel 2002). |

| 38 | (Kriss-Retenbeck 1972 and Kagan 2000). |

| 39 | For a comprehensive study on votive panels, what they are, when they emerged, their iconography, and production context, see Jacobs 2013. |

| 40 | Edwards et al. (2015), p. 3–29. |

| 41 | (Widnmer Sennhauser 2001). |

| 42 | Audiencia de Santo Domingo 1744–1752, vols. 942. |

| 43 | De los Santos 2003, p. 125. |

| 44 | See (Magin and Eisermann 2009, pp. 190–203). |

| 45 | Dating back to the seventeenth century in Spanish sources, the Virgin of la Caridad del Cobre was a devotion with a special link to the open-pit copper mine and enslaved blacks that had been confiscated from private hands by the Crown in 1670 in the town of Santiago del Prado, Cuba. According to ordained priest Onofre de Fonseca’s Historia de la Aparición Milagrosa de Nuestra Señora de la Caridad del Cobre (c. 1701–3), two male Indians and a black male youth (Juan y Rodrigo de Hoyos, and Juan Moreno) discovered circa 1612 an effigy of the Virgin floating in the water while collecting salt near the Bay of Nipe. The sculpture soon settled in a shrine in nearby Santiago del Prado (today El Cobre) after the Virgin numinously expressed her desire to reside there. Free and enslaved people of color established a deep connection with the Virgin of La Caridad and used her to gain a collective voice in colonial society. In 1677, about to be sold to Havana to build military fortifications, they fled to the mountains and wrote a plea to the King demanding constitution into a pueblo, citing their creolité (nativeness) and their identity as townspeople of El Cobre (cobreros). An important piece of evidence furnished was the testimony of by then 85-year old Juan Moreno, one of the original witnesses of the miracle. As primitive devotees of the Virgin of La Caridad, their history was thus firmly anchored to the foundational story of the town, and therefore they felt secure they could not be sold back into private hands. See (Díaz 2002). |

| 46 | Irisarri Aguirre (2003), p. 16. |

| 47 | Sergio Barbieri found the miracle text in period documents. See footnote No.16. |

| 48 | Modes of expected behaviour for parishioners were contained in the pastoral visits, and images that acted as moralizing tales served similar roles. Recommendation #9 from pastoral visit of Antonio de la Concha Solano in 1740 to San Dionisio sanctuary prescribed that “nobody, independent of socioracial status (calidad) should lean on the altar nor the women should sit on these…” See (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 41). |

| 49 | The original is kept at the Archivo Nacional de Cuba, filed under Asuntos Políticos—3. 97 A. One of the testimonies is at the AGI, and another one at the Biblioteca de Palacio de Madrid. For an analysis of the ambiguity in the Black Code of 1784, see (Hontanilla 2015). |

| 50 | See Chapter II on Education and Good Customs, (Pérez Memén 2010). |

| 51 | René Taylor claims the painting honors the Carmelite nun Margarita de la Concepción who granted legal freedom to a slave, while others claim the black figures constitute the nun’s dowry. See Taylor 1988, p. 17. Also, see “Exvoto de la Sagrada Familia by José Campeche y Jordán,” https://artsandculture.google.com/story/exvoto-de-la-sagrada-familia-by-jos%C3%A9-campeche-y-jord%C3%A1n-instituto-de-cultura-puertorriquena/aAWB87qdFEO1JA?hl=en, Google Arts & Culture, accessed last 1 June 2021. |

| 52 | I thank Adam Harris Levine for bringing to my attention the work of María Elba Torres Muñoz, who addresses Campeche’s treatment of the black figures in this painting, highlighting the artist’s positionality as a mulatto and how the colors of the clothing evoke afrodiasporic knowledges. |

| 53 | (Lugo-Ortiz 2013, p. 206). |

| 54 | Lugo-Ortiz 2013, p. 219. |

| 55 | Lugo-Ortiz 2013, p. 213. |

| 56 | In thinking about creole origin stories, I was inspired by the notion of foundational fictions. See Sommer 1993. |

| 57 | The Synod of Santo Domingo of 1683 mentions enslaved people marrying without their masters’ consent. See Audiencia Santo Domingo 1683–1699, pp. 247–301. |

| 58 | See (Wisnoski 2014). |

| 59 | A rich body of literature on marriage in the Spanish Americas includes Erika Denise Edward 2020; Rípodaz Ardanaz 1977; Martínez Alier 2009; Seed 1988; Twinam 1999). |

| 60 | (Sáez 1994, p. 56). |

| 61 | Salmoral 1995, p. 304. |

| 62 | (Sáez 1994, p. 28). |

| 63 | “A black woman induced by seeing her friend jailed, looked carefully for the words of the consecration, according to five witnesses who were summoned, and since there are witches and spells around here my vicar-general and I are treading carefully to remedy this wrong seeing that everything here is hushed down my vicar-general sent her to prison and asked the secular arm for help.” [my translation]. See Audiencia de Santo Domingo 1684–1695, vols. 93. |

| 64 | The words of the consecration echo the words that Jesus uttered when he consecrated wine and bread at the Last Supper by exclaiming: “This is my flesh… This is my blood…” (Luke 22: 19–20). Preceding the Eucharist, the consecration is the moment in mass when the miracle of transubstantiation takes place, i.e., when the host and wine transform into the body and blood of Christ. When a priest utters these words, he embodies Christ and enacts the miracle of transubstantiation. Understanding the mystery of this miracle, known in Christian theology as the Real Presence, was an important line dividing Christian denominations since the Reformation. Accepting Real Presence as an infallible dogma bound the community of the Roman Catholic Church and its members. The words of the consecration were recited by clergy in an inaudible whisper and were not even printed because of fears that if “common folk knew the exact words of the canon they would undoubtedly use them for conjuring and charming…” See Bossy (1983), 29–61; and Jungmann 1986, p. 1951–55. |

| 65 | (Ivanov 1999). |

| 66 | The last piece of the decree was missing, which is why the exact date of the decree is unknown. However, John Fleury suggests it was signed in 1783. See Fleury 2006, p. 512. |

| 67 | (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 87). |

| 68 | Hernández González 2002, p. 106–12. |

| 69 | A letter dated 7 July 1744, signed by Santo Domingo residents, expresses concern that afro-descendants were being ordained, see (Audiencia de Santo Domingo 1744, Santo Domingo 319). Also, see the preliminary reports by Hispaniola authorities on the drafting of the Black code and their opinion on the situation of people of color in the island. See Malagón 1974, p. 87–113. |

| 70 | (Malagón Barceló 1974, p. 89). |

| 71 | Malagón Barceló 1974, p. 89. |

| 72 | Fr. Domingo Fernández Navarrete explains the regulations in the Diocesan Synod of 1683 in Santo Domingo. See Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 87. |

| 73 | Similarities can be drawn between the feasts of three crosses and Corpus Christi celebrations. Dating back to the thirteenth-century Roman Catholic Church, Corpus Christi was a celebration of signs of difference that divided social groups into the vanquished and the victorious. It celebrated the consecrated host and the triumph over heresy. It typically involved processions and plays in the Iberian peninsula where Christ _as blessed sacrament_ conquered non-Christian characters, such as Arabs, Moors, and Turks. In the Americas, Indians were used, and in Santo Domingo, African subjects carried “máscaras de diablos” (devil masks). For Corpus Christi in Viceregal Peru, see Dean 1999. |

| 74 | (Cipriano de Utrera 1933, p. 87). |

| 75 | (Román Fernández and Silva 2000, pp. 283–93). |

| 76 | “… Concibo la necesidad de que el Código y Reglamento abracen todas las clases que proceden de negros, dándoles su respectivo lugar en las leyes pues si solamente se determine sobre los esclavos, quedaría (a mi entender) toda la dificultad en pie, por la relación y correspondencia [expuesta anteriormente]” [my translation] See (Malagón Barceló 1974, p. 95). |

| 77 | See (Blanco 1998, pp. 134–35). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).