1. Introduction

The drawing Leda and the Swan in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, RCIN 912759, dated 1507, is one of Raphael’s best-known mythological studies and conceivably among the most remarkable portraits on paper dedicated to the figure of Leda. The examination of the drawing from life came about almost by chance. A research visit to Windsor was made to analyse the paper supports of a series of drawings made by Leonardo da Vinci. Due to the busy exhibition schedule of 2019, the year of the celebrations for the 500-year anniversary of da Vinci’s death, some of the drawings selected for investigation were not available for consultation, and these included those relating to the Leda studies. Therefore, the writer decided to survey the most directly related thematic and chronological contribution—Raphael’s Leda—and this intuition proved fortunate. It became evident that the information regarding the physical properties of sheet RCIN 912759 is limited and not easily accessible.

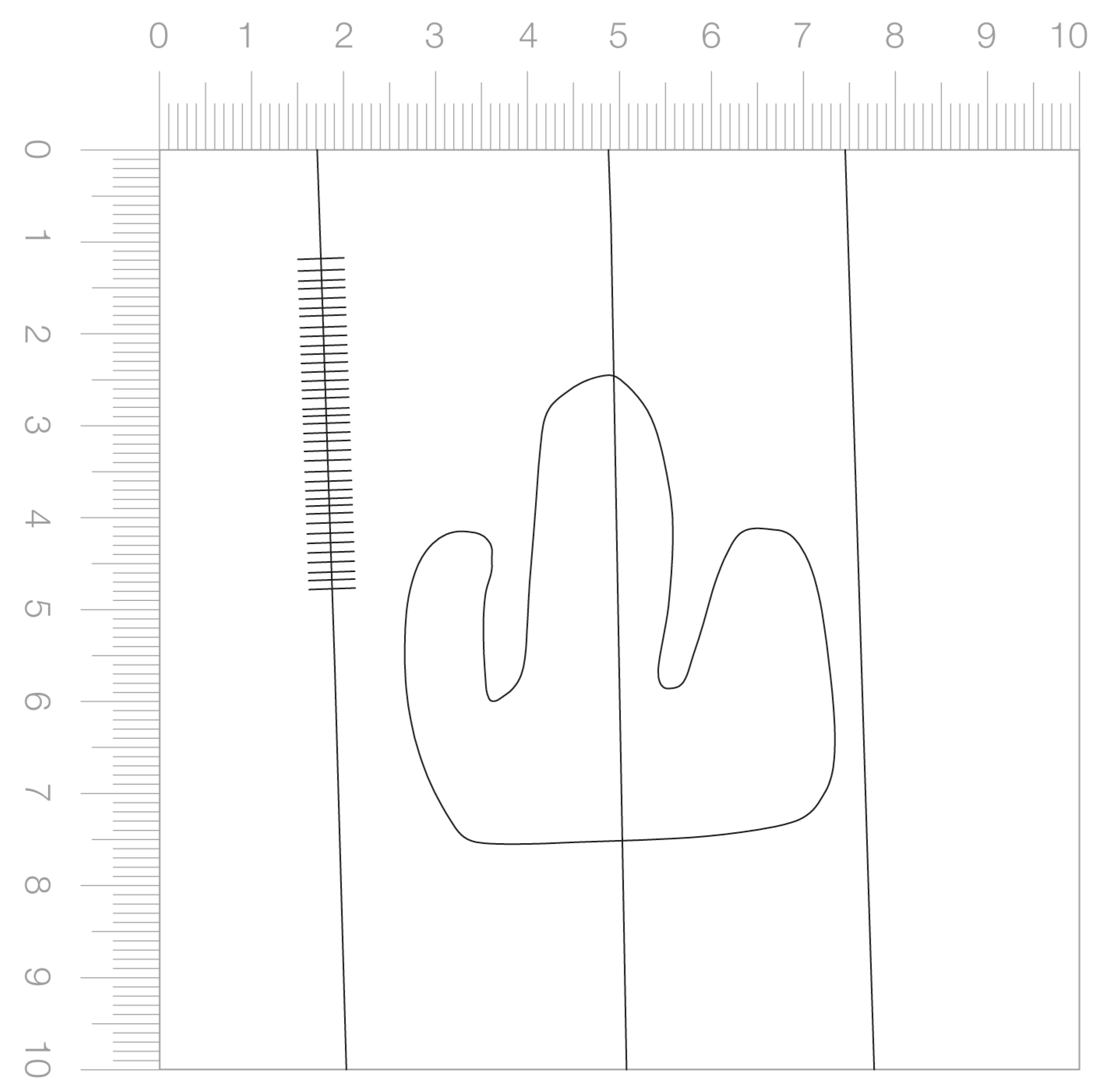

The drawing has been widely analysed from the historical–artistic perspective and is often described and compared, as a copy, to Leonardo da Vinci’s studies regarding the standing Leda. However, the vast bibliography on the subject does not satisfy the needs of those who wish to conduct an in-depth study of the aspects relating to the type of paper chosen by Raphael for his work. This important cognitive gap presents the opportunity to start a new study on the Windsor sheet to detect the codicological parameters necessary to provide new chronological and provenance indications on the document, auxiliary information compared to that provided by the history of art, paleography or examinations of the graphic ductus. These alternative markers of investigation define the impression left on the sheet by the mould of the metal frame originally employed during the papermaking process, especially in the watermark’s graphic appearance. Considering the artistic value of the artefact, the lack of any in-depth study of the paper medium is quite significant, especially in the light of the ever-increasing and efficient use of diagnostic techniques in the cultural heritage domain to interrogate materials for various purposes: study, archiving, monitoring, conservation, restoration and exhibition.

Thus, the idea emerged of focusing on the disciplinary edge between the artistic analysis of the drawing and the technical analysis of the paper, halfway between Raphael’s and Leonardo’s productions, circumscribed within the studies on Leda and between drawings bearing watermarks of the same classification. The article is not intended to be exhaustive, either in terms of a critical commentary on Raphael’s drawing, or in terms of reconstructing the Leonardo sources from which Raphael is said to have derived his work.

2. Hypothesis and Aims of the Essay

The information regarding the physical properties of the paper on sheet RCIN 912759 is modest. This problem affects Raphael’s complete production on paper because there is no systematic investigation regarding the watermarks on his drawings (

Bambach 1999, p. 389, note 54). This lack of knowledge limits research and requires scholars to carry out lengthy bibliographical investigations before finding information on the subject. For example, the

opera omnia on Raphael’s drawings edited by

Knab et al. (

1983) does not have a section on the paper data of the folios. Few editions include notes on watermarks in parallel with the analysis of the drawing. These are generally drawing catalogues created to accompany exhibitions (

Dalli Regoli et al. 2001;

Nanni and Monaco 2007, pp. 226–27) or as an anthology of a specific museum collection. In both cases, it is a matter of research on individual sections of drawings, and not on the artist as a whole. The curators’ choices determine the presence or absence of specific studies on the papers and the degree of depth.

The issue of generating a set of new content on the physical aspects of the document is crucial for implementing dissemination bodies. A key example is that not even the online catalogue of the Royal Collection provides information on the mould lines of sheet RCIN 912759. This fact is highly anomalous because notes on watermarks are available for other documents in the same collection (Leonardo’s sheets).

This study seeks to make the physical data for the paper (RCIN 912759) accessible, on the one hand, by extending the information on the watermark, and on the other, by trying to establish plausible relationships between Raphael’s and Leonardo’s drawings.

The novelty of the work does not consist in presenting an innovative watermark digitisation procedure because the researcher preferred to make use of an already tested and effective data acquisition system. According to an art–design-oriented approach, the contribution of the work is to decode and catalogue the physical properties of Raphael’s paper in quantitative and qualitative terms to provide a valuable basis of information for future research on the sheet.

Based on the watermark’s arborescence (design or motif) analysis, the essay also proposes new elements to contextualise the drawing chronologically and to circumscribe the paper’s geographical area of origin. In order to do so, the author has compared the Raphael watermark with the most similar marks among those registered in the main watermark archives for the central-Italian region (Briquet, Piccard, Niki) and has also established relations with six drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. The work adds to this last consideration a reinterpretation of the concept of comparison between Raphael’s Leda and the iconographic model of Leda developed by Leonardo, elaborating the information obtained from historical sources and classification of watermarks.

4. Leonardo’s Paragone

If one looks closely at the drawing, one notices a fascinating fact: Leda resembles a sculpture. In this case, the surprising volumetric effect not modelled with chiaroscuro effects is given through the figure’s exquisite “di naturale” bearing. The image transcends the double dimension typical of a graphic work because the plasticity of the features and the balanced proportions of the limbs highlight the profound morphological research underlying this stylistic construction, which yields an apparently real Leda according to the physical laws of nature. However, the originality of this compositional structure is not Raphael’s invention. Critics agree that Leonardo’s Leda inspired Raphael.

Leonardo’s

Leda was a lost painting executed on wood, datable to around 1505–1510—but possibly still in process at the time of Leonardo’s death (

Clayton 2018, p. 94). Critics have always considered the attribution of the lost Leda painting to Leonardo to be plausible, yet the issue is still to be resolved. Since it is a missing object and in the absence of direct scientific investigation, Fiorio says:

«we cannot be certain whether Leonardo ever painted a picture of this subject» (

Fiorio 2015, p. 545). For the same reason, it is equally difficult to gauge whether Leonardo worked in terms of total or partial autography, the latter hypothesis admitting the intervention of a pupil (

Zöllner 2016, p.188). Several sources authenticate the existence of the painting. First of all, the work is mentioned in the inventory of Salaì’s possessions after his death (1525) and is recorded as one of Leonardo’s most expensive legacies (

Marani 2019, p. 341). The painting is then mentioned by Anonimo Gaddiano in Milan in 1525 (c. 1540); by Lomazzo on three different occasions, in the

Trattato (1584); in the

Rime (1587); in the

Idea del Tempio della Pittura (1590); and finally, by Cassiano dal Pozzo (

Fiorio 2015, p. 545). The latter saw the painting in the castle of Fontainebleau in 1625, revealing its poor state of conservation:

«Una Leda in piedi, quasi tutta ignuda, col cigno e due uova a piè della figura dalle guscia delle quali si vede esser usciti quattro bambini. Questo pezzo è finitissimo, ma alquanto secco, in ispecie il petto della donna, del resto il paese (paesaggio n.d.c.) e la verdura (vegetazione n.d.c.) è condotta con grandissima diligenza; ed è molto per la mala via, perché com’è fatto di tre tavole per lo lungo, quelle scostate via

han fatto staccare assai del colorito[…]». Translated into approximate English, since the Italian language of the 1600s is not particularly straightforward, it says: «A standing figure of Leda almost entirely naked, with the swan by her and two eggs, from whose broken shells come forth four babies, This work, although somewhat dry in style, is exquisitely finished, especially in the woman’s breast; and for the rest of the landscape and the plant life are rendered with the greatest diligence. Unfortunately, the picture is in a bad state because it is done on three long panels which have split apart and broken off a certain amount of paint». The subsequent fate of the painting is uncertain; it is thought to have been destroyed in the 18th century (

Clayton 2018, p. 94) or to have disappeared from 1775 onwards (

Poggi 1919, pp. 36–38). Leonardo’s Leda is known chiefly through pictorial derivations by pupils or followers (

Fiorio 2015, p. 545).

The material on the subject, collected between original production on paper and copies, suggests a careful and gradual development for Leda’s model, distinguished by revisions and corrections. There is enough material on the subject to believe that Leonardo put a great deal of effort into this new work structure, which led the artist to modify his initial compositional ideas over time. Two different versions of the same theme are known: a kneeling Leda and a standing Leda. The painting attributed to the Lombard painter Giampietrino in Kassel (Staatliche Museen, inv. 1749, no. 850) is currently the only pictorial derivation of Leonardo’s studies for the kneeling Leda, while the replicas depicting the standing Leda are much more numerous. Among the most reliable are the

Leda Spiridon in Florence (Uffizi Gallery, inv. 1890, no. 9953); the exemplar in the Pembroke Collection at Wilton House near Salisbury; and the versions in the Philadelphia Museum and the Galleria Borghese in Rome, the latter of which was attributed for centuries to Sodoma. Variants on paper, not by the hand of Leonardo, in addition to the version by Raphael, include the small sketch by Baldassare Peruzzi on the sheet in the Prints and Drawings Cabinet of the Uffizi (inv. N. 528A) and the drawing by an anonymous artist in the Musée du Louvre in Paris (inv. N. 2563) in red chalk (

Clayton 1999, p. 57).

Leonardo’s autograph traces on the subject survive exclusively in the manuscripts. The sketches from Chatsworth (Chatsworth, Duke of Devonshire Collection Trust, inv. 717) and Rotterdam (Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, inv. I 446) document an interest in the rendering of a kneeling Leda, while the sheets from Milan (Codex Atlanticus, f. 423 recto), Turin (Biblioteca Reale, inv. 15577) and Windsor (RCIN 970129) refer to a standing Leda. Also, in Windsor, there is a beautiful series of studies of female heads and hairstyles that can probably be traced back to drafts of the iconographic model of the lost painting of Leda (RCINS 912515, 912516, 912517, 912518). The sources for creating this work come from the comparison with antiquity. There are explicit references to the statuary of V

enus Pudica (

Nanni 2001, p. 38) and the marble

Ganymede with the Eagle, (

Marani 2015, p. 138) already considered possible models of inspiration. Recent investigations have also brought to light an interesting new reference to a late Hellenistic marble bust housed in the Liviano Museum in Padua (

Figure 2).

The technical–formal characteristics of the Paduan

Torsetto directly correspond to Leonardo’s prototype, allowing us to consider this production as one of those directly involved in the process of iconographic assimilation of Leda, and more generally of a new female canon (

Ghedini 1984), by those Renaissance artists most sensitive to the reinterpretation of the ancient, including Leonardo. Between the 15th and 16th centuries, a lively collectors’ trade fostered the concept of recovering classical art. This phenomenon facilitated the circulation of Hellenistic-Roman artefacts, often reproductions of lost Greek collections, helpful in activating creative processes of iconographic reworking of the antique. This impulse was also fostered by visits to archaeological sites, a sort of

ante-litteram grand tour among classical wonders. Documents testify that Leonardo and Raphael also made journeys for this purpose. The artists went to Tivoli, at different times, to admire the sculptures and pomp belonging to the archaeological complex of Hadrian’s Villa. Leonardo’s visit to Tivoli would have allowed the artist to observe the statues of the

Muses found in the theatre of the Villa (now in the Prado Museum in Madrid). The period would have been between 1497 and 1503, during the pontificate of Pope Alexander VI.

Leonardo’s presence in Tivoli is certified in a folio of the

Codex Atlanticus. In f. 618 verso, on the right-hand side of the page, Leonardo notes:

«A Roma. A Tivoli vecchio, casa d’Adriano». Below the sheet fold, there is also the following indication:

«Laus deo 1500, a dì 10 marzo». Restated by the adoption of the Florentine style of dating (

ab Incarnatione Domini), the date should be understood as 10 March 1501 (

Marani 2003, p. 259) even if at first this note by “another hand” (not Leonardo), was transcribed by Marinoni “albeit with some doubt” as 20 March 1500 (Leonardo

da Vinci 2006, vol. 11, pp. 175–76). The name of the locality

“Tivoli Vecchio” confirms that it is indeed Hadrian’s Villa, because this was the name by which the villa was generally identified during the transitional period between 500 AD and 1400 while it was used as a brick and marble quarry (

De Franceschini 1991, p. 5). Even during the Renaissance, the toponym remained in force when the area became a popular archaeological site for studying classical architecture and art. News of Raphael’s pilgrimage, on the other hand, comes from Pietro Bembo, a skilled scholar and poet, and a close friend of the Urbino painter:

«Io col Navagero col Beavano e con M. Baldassar Castiglione e con Raffaello domani anderò a riveder Tivoli, che io vidi già una altra volta vintisene anni sono. Prenderemo il vecchio e il nuovo, e ciò che di bello fia in qualla contrada». The letter is dated 3 April 1516 and is addressed to Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena (

Bembo 1809, p. 45).

How Raphael gained access to Leonardo’s studies for the Leda has yet to be clarified, but the opportunity may have occurred in the city of Florence. Although there is no firm evidence of direct contact between Raphael and Leonardo, some of Raphael’s writings speak of a meeting with Leonardo, whom he described as hospitable and welcoming, to the point of inviting the young colleague into his studio (

Duò 2020, pp. 18–19). The meeting may have taken place in Florence between Autumn 1504, Raphael’s arrival in the city, and June 1506, when Leonardo departed for Milan (

Zöllner 2016, p. 247). It is also possible that Raphael viewed Leonardo’s drawings and cartoons for Leda outside the artist’s studio and through the mediation of a pupil or trusted person who had access to the master’s material. The hypothesis of an engagement between the two artists in Rome (1513–1516) is less probable since Raphael’s style is restricted to the Florentine period and 1508 at the latest (

Clayton 1999, p. 57). Between 1504–1506, Leonardo was in the city to follow the demanding commission of the

Battle of Anghiari for the Sala del Gran Consiglio in Palazzo della Signoria.

Leonardo would have started thinking about the composition of

Leda at the time of the

Battle of Anghiari around 1504. This fact can be seen on sheet RCIN 912337 at Windsor (ca. 1503–1504). On the recto of the sheet, next to the main drawing of a prancing horse with rider, an apparent reference to the

Battle scene for the mural painting in the Sala del Gran Consiglio, are three sketches with a figure of a kneeling woman with children. The woman’s crouching position is very reminiscent of the Chatsworth and Rotterdam proposals, which are unanimously regarded as studies for an early version of Leda. Two of the female sketches are bordered by a frame to indicate a different subject from the main one on the sheet (the horse) and perhaps relate to the proportions of the figures from a pictorial work. The third is depicted in an outline and is not overlaid in pen, making it difficult to read. Critics have discussed the study of this sheet widely in relation to the genesis of the Leda studies. The horse’s position in the centre of the page speculates that it was drawn chronologically prior to the others on the sheet. This fact could set the execution of the three Leda miniatures to a historical period not earlier than 1504. The watermark in RCIN 912337, with the motif “ladder in oval with 6-pointed star”, close to Briquet 5920 and 5922, confirms a Tuscan provenance of the paper and a historical reference period between 1495 and 1506 (

Briquet 1907, vol. 2, p. 345).

Vasari says that the direct comparison with Leonardo’s art struck Raphael to the point of wanting to interiorise the most distinctive features of Leonardo’s poetics. Here is a passage from

Le Vite… (

Vasari 2019, pp. 636–37):

«Perciò che vedendo egli l’opere di Lionardo da Vinci, il quale nell’arie delle teste, così di maschi come di femmine, non ebbe pari e nel dar grazia alle figure e ne’ moti superò tutti gl’altri pittori, restò tutto stupefatto e maravigliato; et insomma, piacendogli la maniera di Lionardo più che qualunche altra avesse veduta mai, si mise a studiarla e lasciando, se bene con gran fatica a poco a poco la maniera di Pietro, cercò, quanto seppe e poté il più, d’imitare la maniera di esso Lionardo. Ma per diligenza o studio che facesse, in alcune difficultà non poté mai passare Lionardo; e se bene pare a molti che egli lo passasse nella dolcezza et in una certa facilità naturale, egli nondimeno non gli fu punto superiore in un certo fondamento terribile di concetti e grandezza d’arte, nel che pochi sono stati pari a Lionardo. Ma Raffaello se gli è avvicinato bene più che nessuno altro pittore, e massimamente nella grazia de’ colori». Rendered into English: «Therefore, when he saw the works of Leonardo da Vinci, who had no equal in the rendering of the heads of both males and females, and who surpassed all other painters in giving grace to the figures and in the movements, he was completely astonished and amazed; In short, liking the manner of Leonardo more than any other he had ever seen, he began to study it and, leaving behind the manner of Pietro, albeit with great effort, he tried, as much as he could, to imitate the manner of Leonardo. However, no matter how hard he tried or how much he studied, he was never able to surpass Leonardo in certain difficulties; and if it seems to many that he surpassed him in gentleness and certain natural ease, he was nevertheless not superior to him in a certain powerful foundation of concepts and greatness of art, in which few have been equal to Leonardo. Nevertheless, Raphael came closer to him than any other painter, and especially in the grace of the colours».

Nevertheless, in the case of Leda, Leonardo’s work must have fascinated Raphael not only from a methodological point of view of recovering ancient culture, through original reinterpretations or from a purely formal point of view, but also for its beauty. In this sense, the results of such convincing artistic modelling in spatial terms are also enhanced by Leonardo’s ability to transfer into drawing a three-dimensional vision of sculptural forms, a quality he developed as a young man during his apprenticeship with his master Verrocchio. The lesson learnt from the ancients was valuable to Leonardo in appropriating a more monumental language full of pathos, never transferred in a slavish way, but sublimated according to a ‘natural’ and scientific meaning of art, which would gradually become increasingly conceptual. According to comparisons with surviving paintings by Leonardo’s pupils, Raphael’s desire to make a copy of Leonardo’s Leda is a response to his falling in love with this subject. It is perhaps also the reflection of a Raphael who was not fully mature and therefore sensitive to absorbing the most convincing figurative inventions from outside to form his own iconographic-stylistic technique from which he could rework new and personal languages.

8. Conclusions

This article has highlighted the value of the watermark as an investigative tool to support art historians in the process of understanding a drawing or manuscript. Technical analyses aimed at recording the physical properties of the paper were necessary to access a more comprehensive order of understanding about the cultural artefact. As with “archaeological excavations”, these operations, which sought to uncover the stratigraphy of the paper element, have led to improvements in knowledge on various levels: both on the papermaking features of the artefact, and indirectly on the contextual elements of the graphic work. In the humanities, and particularly in art history, awareness of the paper used by an artist helps to confirm or reject attributions not only chronologically but also in terms of authorship, especially in the case of seminal protagonists in their cultural field—such as Raphael and Leonardo who had pupils and followers.

A key point of this work was to express the importance of the concept of access to information. The design process develops a model for extracting, digitally retracing and archiving the mould lines of the paper’s sheet successfully and with a simple solution. The article highlighted the need to scientifically account for the results achieved by instrumental investigations with a view to dissemination and generating new research. Hence, the importance of a data cataloguing system includes the paradigmatic references of the analyses, complete with bibliographic sources and supplemented by academically accepted international archiving and classification parameters. The output scenario covers a wide range of applications in the context of graphic oeuvre for authentication, enhancement, monitoring, archiving and dating and, therefore, is useful for cultural institutions, museums, archives, libraries and private collections.

Future research in this project intends to make the paper data cataloguing system more effective by implementing the watermark representation diagram with an interface that communicates the primary quantitative data of the paper in an informative-visual format. In parallel, the project plans to continue sampling watermarks in Raphael and Leonardo drawings. The consequences of the new research could have relevance to constitute a corpus of information concerning the operating habits of a specific artist concerning the paper used, quality preferences, format, place of production and frequency of use. Finally, these investigations can actively contribute to enriching the repertoires of watermarked papers. Although the excessive proliferation of new types of marks may in the future complicate the choice of the most suitable comparative sample, the community of scholars will only be able to increase the effectiveness of historical attributions through an exhaustive and constantly updated cultural heritage of watermarks.