Abstract

There are many risks that students face while abroad; from tragic accidents, illness, and disease to becoming victims of violent crimes. Human trafficking is an international threat facing everyone. While victims of human trafficking come from all walks of life, in particular, individuals belonging to vulnerable populations are often targeted for this method of exploitation. Cultural competency, language barriers, and ignorance as to resources are all factors which contribute to the increased vulnerability of students studying abroad. An institution providing opportunities for international study should develop an effective approach to mitigate the risk of human trafficking through programs designed to enable students to protect themselves and others effectively. This paper comments on best practices for risk management, and explores different avenues and relevant law for increased transparency in study abroad risk.

1. Introduction

Study abroad has become increasingly popular among American students. More than 335,000 students participated in study abroad programs in the 2014–2015 academic year, a three percent increase from the year prior1. Technological advancements have resulted in an increasingly interconnected, globalized workforce that places an emphasis on international study experience. The importance of international collaboration in the booming tech industry, for example, is reflected in national data demonstrating that students in STEM fields are the largest proportion of students studying abroad (IIE 2016b). Given that these majors are steadily increasing in popularity and utility, it is likely that the number of students studying abroad will continue to increase as well. Furthermore, there has been a push from employers in the private sector, as well as political figures in the public sector, to encourage study abroad participation2. With the globalization of higher education, risk management strategies should be supplemented with an understanding of institutional obligations under international law. This paper focuses on human trafficking as just one example of risk that students may encounter while studying abroad which implicates domestic and international law.

The United Nations define human trafficking as the “recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons” by means of “using methods of threat, force, fraud, or coercion, for the purpose of exploitation”3. Factors associated with an increased risk of human trafficking include economic vulnerability, natural disaster, sudden changes in social structure, war or political conflict, corruption among State officials, and social inequality (World Health Organization 2012). It makes sense that human trafficking would pose a credible risk in the context of study abroad programs, given characteristics common among college students as well as the mission statements of study abroad programming. Many study abroad programs with charitable or development-oriented missions specifically seek out work with vulnerable communities ravaged by the very factors associated with human trafficking risk.

Furthermore, students today are subject to increasing economic vulnerability. As higher education budgeting faces deep cutbacks, scholarship amounts are decreasing and tuition rates have been steadily on the rise. Even students subsisting on student loans to bear the cost of higher education are finding borrowers’ protection and forgiveness programs on the political chopping block. Due to the time and effort involved in studying, many students are unable to take on full-time employment, and may be pushed to seek employment in riskier, informal occupations. Such occupations may allow for increased flexibility; however, they also may be more prone to targeting by traffickers, for instance, those working in transient farming operations, “under the table” childcare and domestic work, or in the sex industry. Thus, college students are often financially vulnerable, making them more at risk to fall victim to trafficking.

As a mobile and untraceable population, precise statistics on the number of trafficked persons are unavailable, including those specific to higher education abroad or in the United States (Meinecke 2013). There have, however, been reported instances of traffickers targeting campuses within the U.S. Traffickers have been known to send recruiters to colleges and universities to recruit students into trafficking by promising that they will make money (Horgan 2014). When studying abroad, this vulnerability is magnified by the compounding factors of being in an unfamiliar environment, with little local connections or knowledge of the area.

There is an unsettlingly sparse body of literature addressing the problem of human trafficking in the context of higher education generally, as well as in the context of study abroad. The lack of attention paid to this issue has likely been exacerbated by the lack of transparency required on part of universities. It is the responsibility and duty of universities engaged in international study abroad programming to ensure that they both protect their students from becoming trafficking victims themselves, as well as to ensure that these programs are free of forced labor at all levels of operation.

2. Relevant Law

2.1. Trafficking Victim Protection Act

The Trafficking Victim Protection Act (TVPA) is the main United States federal legal instrument to address the issue of human trafficking4. The TVPA provides for the prosecution of perpetrators of trafficking in persons and their respective punishments; protection of victims via a victims’ bill of rights; and prevention of trafficking by allowing for programs and grants to increase awareness of the problem posed by human trafficking.

In the study abroad context, it is of particular importance to know the extent to which host countries are in compliance with the basic requirements of the TVPA. In particular, where a student falls victim to human trafficking, the victims’ bill of rights is of immense importance. Universities must be aware of whether or not host countries have formal legal structures providing victim students with the right to medical care and shelter, as well as the opportunity for restitution and other civil remedies against their trafficker. In the absence of these protocols, institutions should take measures to provide formal structures of support through contractual agreements and other appropriate means. Furthermore, it is important that students are working in study abroad programs within countries that take seriously the prosecution of perpetrators of trafficking, as well as their obligation to engage in preventative efforts.

2.2. Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972

Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 states, in part, that no student shall be denied, on the basis of sex, access to the educational benefits and opportunities provided at an institution receiving federal funding5. Title IX operates by conditional offer of federal funding on a promise by the recipient not to discriminate, in what amounts essentially to a contract between government and recipient6. Congress enacted Title IX with the objective of avoiding the use of federal resources to support practices deemed discriminatory on the basis on sex7. Sexual discrimination includes sexual harassment, and sexual violence, including sexual exploitation of another, is deemed one of the most severe forms of sexual harassment8. Where trafficking is for the purposes of sexual exploitation, this is a clear instance of sexual violence, and thus falls under the purview of Title IX.

Under Title IX, a university is obligated to respond to complaints of sexual discrimination with prompt and equitable measures aimed at alleviating any hostile learning environment9. That is to say, universities must respond in a manner that allows the victim student to continue learning effectively in their environment. A student who has been the victim of a violent crime may be unable to focus on their schoolwork, for example. Additionally, a university is required to put policies and practices in place to educate the student body on sexual discrimination, and to prevent its occurrence10. As a violent sexual crime, trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation should be included in this approach: both in responding to students falling victim to this crime, as well as in preventative educational efforts.

Furthermore, a university’s duties and responsibilities under Title IX are not limited to incidents which occur on campus. Instead, a school has a duty under Title IX where a violation occurs in the course of any school-sponsored activity, a definition which includes incidents occurring in any school-sponsored study abroad program11. Thus, Title IX has already placed an obligation on universities to respond to allegations of sex trafficking of students participating in their programs, both on campus as well as in international study abroad programs.

2.3. Executive Order 13,627: “Strengthening Protections against Trafficking in Government Contracting”

Executive Order 13,627 “Strengthening Protections Against Trafficking in Government Contracting” imposes a responsibility on behalf of the Government to ensure that taxpayer dollars do not contribute to trafficking in persons12. As taxpayer dollars directly contribute to Title IV funding, which universities receive from the federal government to allow their students to take out student loans, universities are engaged in a business that directly implicates taxpayer money. Thus, universities must ensure that their programs do not contribute to trafficking in persons under the directive of this order.

The Executive Order requires that, for work exceeding $500,000 that is performed abroad, federal contractors and subcontractors must maintain compliance plans appropriate for the nature and scope of the activities performed13. Such plans must include: an employee awareness program, a process for employees to report trafficking violations without fear of retaliation, and recruitment and housing plans. Each of these contractors and subcontractors must also certify that neither it nor any of its contractors has engaged in trafficking-related activities14.

In the context of study abroad programs, it is essential that universities apply the mandate of this executive order toward ensuring that their foreign accommodation partners, and all other components of their programming delivery, do not support nor engage in trafficking-related activities.

2.4. Clery Act/Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013

The Clery Act requires institutions to record and publish the incidents of certain types of crimes and risks that are occur on campus15. Throughout the academic year, incidents of dating violence, domestic violence, sexual assault, rape, hate crimes, criminal homicide, burglary, vehicle theft, arson, drug and liquor law violations, and weapon law violations are recorded, and these data are compiled into the annual Clery Report. The report is published so that current and prospective students, parents, and governmental agencies may review their findings16. The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 included amendments to the Clery Act, requiring primary prevention and awareness programs for incoming students and employees and ongoing prevention and awareness campaigns for students and employees with regard to dating violence, domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking17. This approach should also include human trafficking, as a crime of violence, and where the purpose is sexual exploitation, a clear instance of sexual assault.

An institution must only disclose in its annual security report statistics for those incidents which occurred on or within its Clery geography. Clery geography includes buildings and property that are part of an institution’s campus, and public property within or immediately adjacent to and accessible from the campus; the term “campus” is defined as any building or property owned or controlled by an institution within the same reasonably contiguous geographic area18. Study abroad programs do not qualify as Clery geography under these definitions, and thus incidents occurring abroad need not be disclosed in the annual security report.

3. Risk

3.1. Risk One: Presence of Study Abroad Programs in Countries More Prone to Human Trafficking

While not all trafficked persons come from vulnerable populations, vulnerability is one of the main root causes of human trafficking, including vulnerability due to poverty; marginalization; social, cultural, and/or economic exclusion; armed conflicts which result in populations of migrants, and/or stateless, displaced communities; discrimination against ethnic minorities; infringements of children’s rights; and gender inequality.

Study abroad programs are present in both destination and origin countries for human trafficking. So, often, study abroad programs target vulnerable areas: a trip to volunteer in a post-natural disaster rebuilding effort, to provide educational services to underserved areas, to tackle social issues faced by international communities which cause economic, social, and political strife. This vulnerability allows of trafficking to flourish, as people in more desperate states seek possible means of survival. These countries are often “origin” countries, meaning that people are trafficked from those countries to “destination” countries, where they are exploited.

For example, study abroad programs have advertised opportunities to travel to post-conflict areas to learn about the underlying conflict, as well as to assist in efforts to rebuild communities impacted by war. Post-war regions and societies can be areas of origin, destination, and transit of trafficking in persons (Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime 2004). After the conclusion of formal fighting, post-war regions are often rife with political instability; dysfunction among law enforcement institutions and systems of community accountability offer ideal conditions for criminal trafficking networks to flourish19. For example, former militia, ex-combatants, or war lords may turn to trafficking in humans to compensate for revenue losses at the conclusion of war20.

The presence of international troops as well as non-governmental organizations contributes to the demand for trafficking as destination areas21. Studies have shown that the presence of foreign troops usually brings a demand for sexual services and domestic labor22. Members of civilian forces may unknowingly or knowingly be clients of trafficked women, or even play an active role in the trafficking. Once outsiders have established a clientele base, locals often also become involved as clients23.

3.2. Risk Two: Study Abroad Programs in Countries with Varying Degrees of Anti-Trafficking Enforcement

Human trafficking flourishes when governments fail to protect and promote people’s human rights. Inadequate laws and policies which minimize the risk of perpetrators getting caught contribute to the supply of persons in the trafficking chain, particularly when aided by corruption at the hands of the state. Therefore, it is important to determine the extent of formal legal prevention, protection, and prosecutorial efforts combatting human trafficking in host counties. This paper utilizes the Trafficking in Persons Report as just one method of assessing host country anti-trafficking measures24. Based upon this analysis, there are many programs currently being offered in countries that are not in full compliance with the TVPA standards.

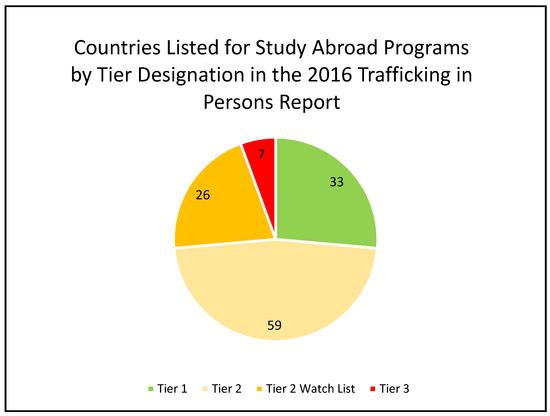

The annual Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP Report) designates countries to a tier as a means of indicating countries’ compliance with TVPA standards (Department of State 2016). It is important for a university to keep up to date with the designations of host countries for the purposes of study abroad. Currently, there are many programs being offered in countries that are not in full compliance with the TVPA standards. A designation of “Tier 1” is given to countries whose governments fully meet the Trafficking in Victims Protection Act’s minimum standards25. Countries whose governments do not fully meet the TVPA’s minimum standards, but are making significant efforts to do so, are designated as “Tier 2”26. The “Tier 2 Watch List” designation is assigned to countries whose governments do not fully meet the TVPA’s minimum requirements, but are making significant efforts to meet those standards AND either the absolute number of victims of severe forms of trafficking is very significant or is significantly increasing; there is a failure to provide evidence of increasing efforts to combat severe forms of trafficking in persons from the previous year27; OR the determination that a country is making significant efforts to meet the minimum standards was based on commitments by the country to take additional future steps over the year28. Finally, countries whose governments do not fully meet the minimum standards and are not making significant efforts to do so are given a “Tier 3” designation29.

The website studyabroad.com (www.studyabroad.com) is a popular resource for students looking to see what study abroad programs are being offered, and where. The website allows for users to “search by country.” Using this feature, data were gathered to determine all of the different countries listed by the website with university-sponsored study abroad programs. A total of 125 different countries were listed. Using this list, the tier designations in the 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report were identified for each individual country provided by studyabroad.com (Department of State 2016). To see the list broken down by specific countries, refer to the Appendix A.

The results of this process are indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Countries Listed for Study Abroad by Trafficking in Persons Report Tier.

A total of 125 countries listed on studyabroad.com were also included in the 2016 TIP Report. Of these countries providing study abroad programs, the majority were hosted in Tier 2 countries, at 59 countries or 47.2%. Programs were offered in Tier 1 countries at the second highest rate, with a total of 33 countries or 26.4%. Closely following at 26 countries, or 20.8%, were programs offered in Tier 2 Watch List countries. Finally, a total of 7 countries, or 5.6%, were designated Tier 3. In other words, nearly three-fourths (73.6%) of the countries listed on studyabroad.com were found not to meet the basic requirements of the TVPA.

That a study abroad program is located in a country that did not receive a Tier 1 designation in the TIP report does not necessarily mean that it should be altogether avoided; instead, it serves as notice to an institution that formal structures typically available to U.S. citizens may not be readily available to their students while abroad. Thus, institutions should work to fill in the potential gaps in the formal legal structure to promote and protect the rights of their students. This process might include, for example, entering into a memorandum of understanding between the institution, program provider, and local law enforcement at study abroad sites to detail how risk should be managed and response protocols for when harm actually occurs.

It is important to be aware of the reason that a country has not received a designation of Tier 1, so as to best tailor an institution’s risk management strategy. For example, if a student is studying in a country that has a formal victim’s bill of rights in place, yet received a Tier 2 watch list designation for an increase in the absolute number of trafficking victims, then there may be less of a need for institutions to put in place formal structures detailing appropriate response and support services. Instead, an institution might focus its efforts on assessing the areas in which risk is most heavily concentrated and providing students with their findings.

3.3. Risk Three: Understanding of Local Risk, Cultural and Community Competency

The lack of mandated reporting for harms experienced by students overseas has likely contributed to the dearth of information regarding local and culturally specific knowledge of risks present at individual study abroad program sites. Institutional reliance on information reported by or about United States universities is insufficient for the purposes of risk assessment. True expert knowledge comes from local communities, and their understandings of risk, crime, and signs of danger. Institutions should employ a collaborative, community-based approach in assessing danger. This process should include working with local magistrates, conducting public records searches, and consulting with law enforcement, tribunals, and business owners. Such an approach is in line with the obligations already imposed by Executive Order 13,627 “Strengthening Protections Against Trafficking in Government Contracting”, and also supports effective risk management strategy implementation.

This information should be publicized to allow students and their families to make informed decisions as to which programs they wish to study at, as well as utilized in pre-departure student training. Sexual crimes are one of the main risks presented in the study abroad context. For example, in Bloss v. The University of Minnesota Board of Regents, a student was raped at knifepoint by a taxi driver while studying abroad in Mexico30. She had initially entered the taxi after flagging the driver down on the street: this fact is essential31. Within the area, it was understood that those seeking taxi services were to call a reputable line to be picked up. Criminals were known to pose as legitimate taxi drivers on the streets32. Thus, the student victim’s lack of knowledge as to the specific risks that were known throughout the community caused her to be unable to take measures to appropriately protect herself from the attack.

Students in study abroad programs must be aware of human trafficking, and culturally competent within their host country, in order to protect themselves from risks overseas. As demonstrated by the Bloss case, students who are not aware of the community understandings of risk, and the culturally specific manners of identifying (knowing taxi on the street is not trustworthy) and avoiding them (calling a reputable agency) may not be sufficiently prepared to protect themselves against harm. In the context of human trafficking, it is essential that students know the cultural and community-specific manners of identifying risks of human trafficking and how to protect themselves against falling victim to this crime.

Students embarking on an international trip require training both so that they may protect themselves, as well as to avoid contributing to the exploitation of others. For example, suppose a student goes to The Hague for a study abroad trip in Amsterdam. During the free time that has been allotted for the students to go out and explore the area, the student travels to the red light district out of curiosity. While there, the student purchases sex from a person on the street who is being forced to sell sex. This student may not have been aware that the person working in the red light district was being trafficked; however, training in cultural competency may have revealed that the purchase of sex on the streets is not the typical method used in the area, and does not have the same anti-trafficking measures that legal, brothel sex work has.

Studies have shown that the more people are aware of this problem, the more likely they are to report suspected human trafficking crimes (Mattar and Van Slyke 2010). For students and faculty working with vulnerable populations, it is essential that they be informed as to how to identify signs of human trafficking, and the proper method of reporting these crimes. Such training should also be required of all foreign partnership agencies involved in the provision of accommodation overseas, including hotels and hostels, travel agencies, and companies providing transportation arrangements.

3.4. Risk Four: Lack of Reporting/Transparency Allows for Universities to Refuse to Respond

Limited reporting requirements while abroad have served to obscure the extent of this problem from the public. The Clery Act requires colleges and universities to publicize an annual report listing the crimes and harms that occurred in the context of their educational programming33. The mandatory Clery Act reporting requirements have historically been geographically limited to acts which occurred on the college campus34. Without these statistics, institutions lack the necessary data to properly engage in risk management. Furthermore, students and families are not able to prepare themselves to face the risks inherent in their study abroad program. Because these statistics are not collected or publicized, students are often going into a program unaware of the measures they should be taking to protect their own safety. Universities should voluntarily extend their reporting to incidents occurring off campus, in particular, in the context of study abroad programs.

3.5. Risk Five: Lack of a Centralized Study Abroad Program Vetting System

The executive order expressly prohibits federal contractors, subcontractors, and their employees from engaging in certain trafficking-related practices, such as misleading or fraudulent recruitment practices; charging employees recruitment fees; and destroying or confiscating an employee’s identity documents, such as a passport or a driver’s license35. Given the varying degrees of formal legal structures and/or compliance with those structures to combat human trafficking across the globe, it is important that universities carefully screen the programs with which they contract for study abroad sessions. A study abroad program advertisement has been used as a means of conducting misleading or fraudulent recruitment practices. For example, students coming from Kazakhstan to work at an advertised study abroad program in Florida were trafficked for sex upon arrival (Mettler 2016).

Furthermore, the suggested best practices enumerated in this paper require wide-scale, dedicated work and resources. To best serve the mission of study abroad risk management and transparency, the formation of a dedicated national workforce to share the burden of these measures would be an invaluable resource in crafting a manageable, realistic approach to international risk management.

3.6. Risk Six: Study Abroad Subcontracting with Facilities That Are Engaged in Human Trafficking

Universities sponsoring study abroad programs are responsible for providing basic means of living to their participants, such as shelter, food, and medical care. Such amenities may be provided by the program, or subcontracted for in addition to the overarching contract with the program provider itself. For example, many short-term study abroad programs use hotels and hostels. Hotels and hostels represent a primary industry in which trafficking occurs, as they are often used as the location in which victims are harbored, as well as the location where sexual exploitation can occur. Universities should carefully screen the company policies regarding human trafficking before contracting with a hotel or hostel for their students’ living arrangements abroad.

4. Integrating Anti-Trafficking into a University’s Programs and Reporting

4.1. Certification: Require Certification by Direct Suppliers That Materials Incorporated into Company Products Comply with the Laws Regarding Slavery and Human Trafficking of the Country or Countries in Which They Are Doing Business

It is necessary to hire a well-informed, trusted foreign travel company to provide updates on regional events and to make itinerary arrangements (Malveaux 2016). In hiring an agent, universities should specifically request information regarding their anti-trafficking awareness and training programs. It is not enough for the program to be located in a “Tier 1” designated country; within these countries, individual corporations may be failing to take measures to combat human trafficking, or even actively supporting the practice themselves.

4.2. Verification and Auditing: Verify Product Supply Chains to Evaluate and Address Risks of Human Trafficking and Slavery; Perform Supplier Audits to Evaluate Compliance with Company Standards

Universities should take it upon themselves to stay up to date regarding current events in their study abroad host countries. Where there are incidents of war or political conflict, natural disaster, sudden economic collapse, or a scarcity of resources, universities should be aware that the resulting vulnerability within such communities will contribute to the risk of human trafficking. As a result, universities should conduct specified inquiry into all of the agencies involved in their study abroad programs that are located in that zone of risk. University representatives should have frequent communications with agencies providing accommodations for their study abroad programs. Study abroad coordinators should closely scrutinize accommodations provided by foreign partnering agencies, and frequent communications can aide these efforts.

4.3. Training: Train Relevant Company Employees and Management on Human Trafficking and Slavery, Particularly Concerning the Mitigation of Risk within Supply Chains

A university should give supervising faculty members appropriate information and training to understand the scope of their responsibilities, as well as potential safety issues that they must navigate36. Included in this training should be information on the prevalence of human trafficking within the communities hosting the study abroad program. Leaders should be instructed as to how to identify signs of human trafficking, the proper methods of reporting such instances, and how best to protect one’s self and others from human trafficking in culturally appropriate and effective ways within the community.

Students also need pre-trip training that specifically addresses the resources available to U.S. citizens overseas. The United States Department of State has instituted the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program, a free service that allows students who travel abroad to be able to get in contact with the nearest U.S. Embassy or Consulate where they will be studying (STEP n.d.). The onus should not be on students to seek out this service; instead, pre-trip orientation should include information as to where the nearest United States embassy is located in reference to where they will be staying.

In preparing educational materials about the risks specific to certain study abroad sites, institutions should cooperate with local law enforcement to gather statistics on the prevalence of certain types of crimes, to be presented in conjunction with any faculty- and student-generated data from reported incidents. To get a full picture of the risks specific to a community, the community itself needs to be engaged.

4.4. Extend Reporting Requirements to Study Abroad Programs

For universities seeking to establish themselves on the cutting edge of best practices, it is a wise move to extend Clery Act reporting to incidents occurring in off-campus study abroad programs. Included in these reports should be statistics regarding instances of human trafficking against students occurring in the context of study abroad programs.

4.5. Increased Monitoring of Students and Faculty Abroad

Although educational efforts are essential to combatting the issue of human trafficking, the enforcement of anti-trafficking initiatives is key to actualizing the messages that students and faculty receive during such trainings. In the context of higher education, institutions have broad discretion in the articulation of their conduct standards. In particular, the study abroad context represents an environment in which students may be exposed to increased risk and thus justifies increased institutional regulation of student conduct. In particular, where a university sends a student to an approved off-campus site to participate in university-sponsored programming, the institution may be held liable where it has knowledge of risk.

5. Conclusions

Institutions of higher education should supplement their compliance with domestic law by shifting their understanding of their legal obligations to incorporate international law, protocol, and treatises with regard to their study abroad programming. Institutions should take a cooperative, community-based approach with local sources of knowledge in assessing the unique risks to individual study abroad sites. Furthermore, institutions should guide the formation of contractual agreements with program providers by assessing the formal legal structures put in place by host countries for the prevention, protection against, and prosecution of human trafficking. Finally, pre-trip training should be delivered that provides students with comprehensive, site-specific knowledge regarding local risk.

While the recommendations put forth in this paper are manageable for an institution to implement acting alone, ideally a centralized agency, taskforce, or transnational effort would be best suited to a truly comprehensive risk assessment and management strategy. Human trafficking is just one example of risk that this paper utilizes to bring light to the larger, underlying issue of study abroad risk transparency. There is no centralized agency, system, or legal obligation on part of institutions to collect and publicize statistics of risk and harm occurring overseas in study abroad programs (Jain 2017). There is a moral and ethical imperative to provide the information necessary for students and their parents to make informed consent in deciding upon a study abroad program. Furthermore, this lack of transparency stunts research efforts into the magnitude of risks posed overseas, and thereby curtails attempts to formulate risk management practices.

Acknowledgments

I have not received any funds for covering the costs to publish in open access.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Countries Listed by Tier Designation

Table A1.

Countries Listed in Studyabroad.com by Tier.

Table A1.

Countries Listed in Studyabroad.com by Tier.

| Tier | Countries Providing Study Abroad Programs Listed in Studyabroad.com | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 |

|

|

|

|

| Tier 2 |

|

|

|

|

| Tier 2 WL |

|

|

|

|

| Tier 3 |

|

|

|

|

References

- Ali, Russlynn. 2011. Assisysny Sec’y for Civil Rights, U.S. DEP’T OF EDUC, Sexual Violence. Available online: http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201104.html (accessed on 4 April 2011).

- Department of State. 2016. Trafficking in Persons Report. Available online: https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2017).

- Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime. 2004. Armed Conflict and Trafficking in Women. Available online: http://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/cso-gtz-armed-conflict-and-trafficking-in-women.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2017).

- Horgan, Sean. 2014. Human Trafficking Still Prominent in North County. The Telescope. December 8. Available online: http://www2.palomar.edu/telescope/2014/12/08/human-trafficking-still-prominent-in-north-county/ (accessed on 24 October 2016).

- IIE (Institute of International Education). 2016a. IIE Releases Open Doors 2016 Data. Available online: https://www.iie.org/Why-IIE/Announcements/2016-11-14-Open-Doors-Data (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- IIE (Institute of International Education). 2016b. Fields of Study of U.S. Study Abroad Students, 2004/05-2014/15. Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange. Available online: https://www.iie.org/Research-and-Insights/Open-Doors/Data/US-Study-Abroad/Fields-of-Study (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- Jain, Rishabh. 2017. When Study Abroad Ends in Death, U.S. Parents Find Few Answers. Available online: https://apnews.com/95305ca19f8f4e5da3da45dd5602d402 (accessed on 7 August 2017).

- Malveaux, Gregory. 2016. Look before Leaping: Risks, Liabilities, and Repair of Study Abroad in Higher Eduication. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mattar, Mohammed, and Shanna Van Slyke. 2010. Improving Our Approach to Human Trafficking. Criminology & Public Policy 9: 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Meinecke, Elisabeth. 2013. Human Trafficking on Your Campus. Townhall. July 20. Available online: https://townhall.com/tipsheet/elisabethmeinecke/2013/07/20/human-trafficking-your-child-might-be-a-target-n1641321 (accessed on 7 August 2017).

- Mettler, Katie. 2016. They Signed Up to Be Exchange Students. They Wound Up Being Sold for Sex. The Washington Post. May 12. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/05/12/these-foreign-exchange-students-were-told-theyd-be-working-at-a-florida-yoga-studio-for-the-summer-instead-they-were-sold-for-sex/ (accessed on 26 October 2016).

- NAFSA. 2017. The Senator Paul Simon Study Abroad Program Act. Available online: http://www.nafsa.org/Policy_and_Advocacy/What_We_Stand_For/Education_Policy/Senator_Paul_Simon_Study_Abroad_Program_Act/ (accessed on 4 August 2017).

- STEP. n.d. Available online: https://step.state.gov/step/ (accessed on 7 August 2017).

- World Health Organization. 2012. Understanding and Addressing Violence Against Women, Human Trafficking. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77394/1/WHO_RHR_12.42_eng.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2017).

| 1 | Over 313,000 received credit and 22,000 in non-credit work, internships, and volunteering. See: (IIE 2016a). |

| 2 | For example, see: (NAFSA 2017). |

| 3 | Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. Opened for Signature, 12 December 2000, S. TREATY DOC NO. 108-16, 2237 U.N.T.S. 319 (entered into force 25 December 2003). |

| 4 | Pub. L. No. 106-386, div. A, 114 Stat. 1466 (Trafficking Victim Protection Act of 2000); see also, VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2013, PL 113-3, 7 March 2013 127 Stat 54 (Trafficking Victim Reauthorization Act of 2013). |

| 5 | 18 U.S.C. 1681(a). |

| 6 | Gebser v. Lago Vista Indep. Sch. Dist., 524 U.S. 274, 286 (1998). |

| 7 | Id. |

| 8 | “Dear Colleague” Letter from (Ali 2011). |

| 9 | Id. |

| 10 | Id. |

| 11 | Id. |

| 12 | Executive Order 13627 (25 September 2012). |

| 13 | Id. |

| 14 | Id. |

| 15 | 20 U.S.C. 1092(f). |

| 16 | 34 C.F.R. § 668.46(c)(1). |

| 17 | Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (Public Law 113-14). |

| 18 | 34 C.F.R. § 668.46(a). |

| 19 | Id. |

| 20 | Id. |

| 21 | Id. |

| 22 | Id. |

| 23 | Id. |

| 24 | It should be noted that this approach is not the only, nor the most comprehensive, manner that anti-trafficking efforts might be assessed. The TIP report has been criticized by many as being a political tool used by the United States government to put pressure on countries. |

| 25 | Id at 55. |

| 26 | Id. |

| 27 | Including increased investigations, prosecutions, and convictions of trafficking crimes, increased assistance to victims, and decreasing evidence of complicity in severe forms of trafficking by government officials. |

| 28 | Id. |

| 29 | Id. |

| 30 | Bloss v. University of Minnesota Board of Regents, 590 N.W.2d 661 (1999). |

| 31 | Id. |

| 32 | Id. |

| 33 | 20 U.S.C. 1092(f). |

| 34 | Id. |

| 35 | Executive Order 13627 (25 September 2012). |

| 36 | Id at 44. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).