Examining the Conservative Shift from Harsh Justice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

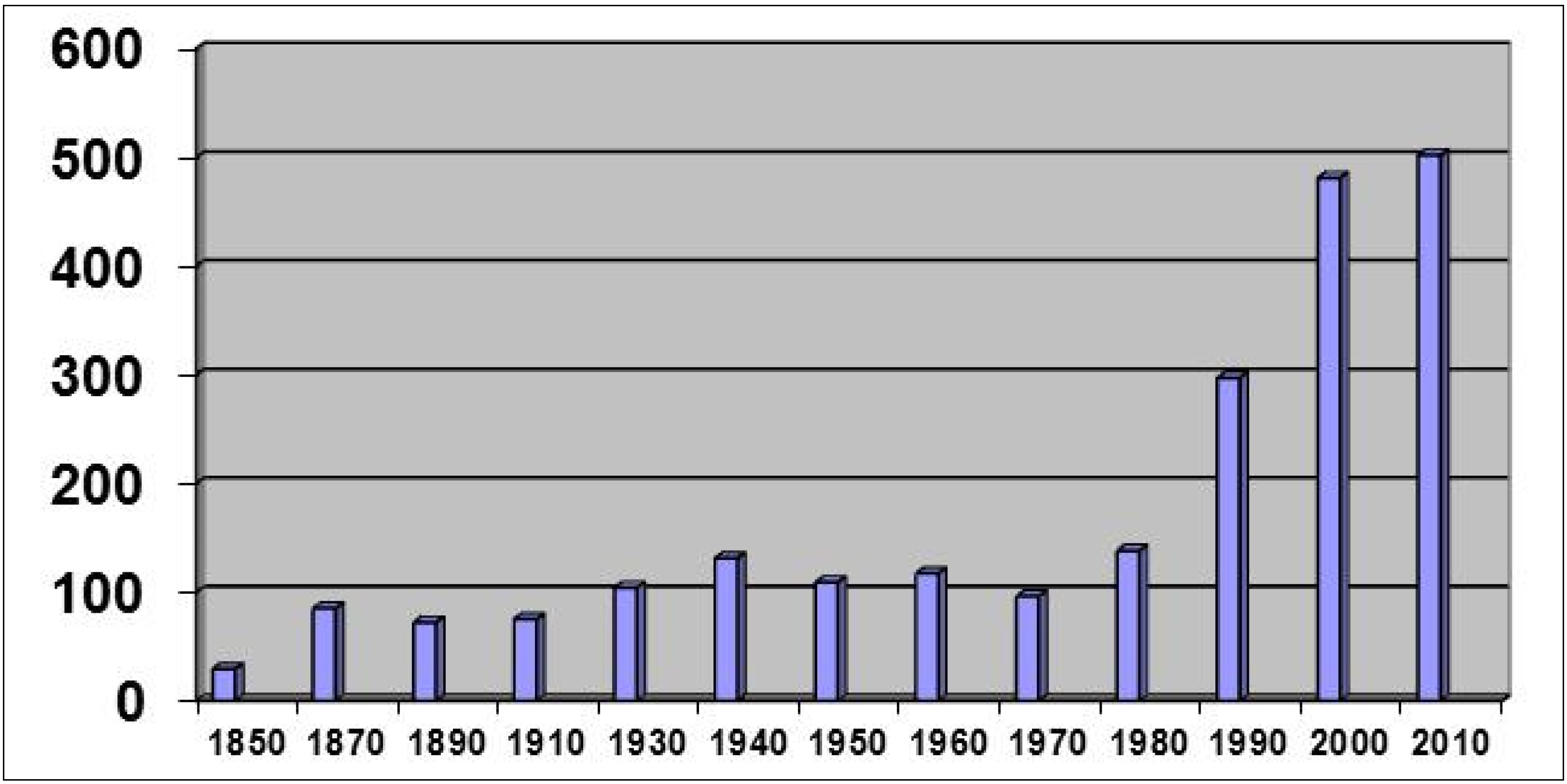

2. United States: A Leader in Incarceration

3. Factors Contributing to Mass Incarceration

4. Effects of Mass Incarceration

5. Calls in the Wilderness: Liberal Support for Diversion

6. The Conservative Shift from Harsh Justice

6.1. What Does the Movement Look Like?

6.2. What Changes Will It Insist upon?

6.3. What Are Its Motivations?

The Pew Charitable Trusts recently reported that states that have cut their imprisonment rates (coupled with other reforms) have experienced a greater crime drop than those that increased incarceration. Between 2007 and 2012, the 10 states with the largest decreases in imprisonment rates had a 12 percent average reduction in crime, while the 10 states with the largest imprisonment rate increases saw crime fall 10 percent.[60]

I think there’s also—in addition to the fiscal motivations, there are also motivations of, look, I mean, every major religious faith believes in redemption and the opportunity for people to turn their lives around and not every offender is amenable to rehabilitation, but many are.

...I mean there’s been a mountain of research over the last few decades that has shown that different alternatives to prison work, whether it’s problem-solving courts, electronic monitoring, treatment diversions for the mentally ill, we’ve had huge advances in risk assessment instruments that can better match offenders with the right programs.[62]

But as Levin points out, there’s just one last thing for Republicans and Democrats working on the issue to sort out: “The only disagreement sometimes is who’s gonna get the credit.”([18], p. 1)

6.4. How Durable Is It?

7. Local versus National Venues

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Centre for Prison Studies. “Highest to lowest—Prison population rate.” Available online: http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison_population_rate (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- E. Ann Carson. “Prisoners in 2013.” September 2014. Available online: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p13.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014). [Google Scholar]

- E. Ann Carson, and Daniela Golinelli. “Prisoners in 2012—Advance counts.” July 2013. Available online: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p12ac.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Paul Guerino, Paige M. Harrison, and William J. Sabol. “Prisoners in 2010.” February 2012. Available online: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p10.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Joycelyn Pollock. Prisons and Prison Life: Costs and Consequences. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Justice Policy Institute. “The punishing decade: Prison and jail estimates at the millennium.” May 2000. Available online: http://www.justicepolicy.org/images/upload/00-05_rep_punishingdecade_ac.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- John Pfaff. “The micro and macro causes of prison growth.” Georgia State University Law Review 28 (2011): 1237–72. [Google Scholar]

- Steven Raphael, and Michael Stoll. Do Prisons Make Us Safer? The Benefits and Costs of the Prison Boom. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan James. “The federal prison population buildup: Overview, policy changes, issues, and options.” April 2014. Available online: http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/ R42937.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Joan Petersilia. “Prisoner reentry: Public safety and reintegration challenges.” The Prison Journal 81 (2001): 360–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katherine J. Rosich, and Kamala Mallik Kane. “Truth in sentencing and state sentencing practices.” In National Institute of Justice Journal; 2005, 252, pp. 18–21. Available online: http://www.nij.gov/journals/252/Pages/sentencing.aspx (accessed on 22 October 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Wildeman, and Bruce Western. “Incarceration in fragile families.” Future of Children 20 (2010): 157–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelle Alexander. The New Jim Crow: Mass Imprisonment in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce Western. Punishment and Inequality in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Michelle Alexander. “In prison reform, money trumps rights.” New York Times. 14 May 2011. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/opinion/15alexander.html?pagewanted=all (accessed on 23 October 2014).

- Ted Chiricos, and George Crawford. “Race and imprisonment: A contextual assessment of the evidence.” In Ethnicity, Race and Crime: Perspectives across Time and Place. Edited by Darnell F. Hawkins. Albany: SUNY Press, 1995, pp. 281–309. [Google Scholar]

- Marie Gottschalk. The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Emma Roller. “How Republicans Stopped Being ‘Tough on Crime’.” National Journal Daily. 2 October 2014. Available online: http://www.nationaljournal.com/congress/how-republicans-stopped-being-tough-on-crime-20141001 (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Christian Henrichson, and Ruth Delaney. “The price of prisons: What incarceration costs taxpayers.” July 2012. Available online: http://www.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/Price_of_Prisons_updated_version_072512.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. “Bureau of Prisons: Information on efforts and potential options to save costs.” September 2014. Available online: http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/666254.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Nancy La Vigne, and Julie Samuels. “The growth and increasing cost of the federal prison system: Drivers and potential solutions.” December 2012. Available online: http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/412693-the-growth-and-increasing-cost-of-the-federal-prison-system.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Christopher Wildeman. “Parental incarceration, child homelessness, and the invisible consequences of mass imprisonment.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 65 (2014): 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc Mauer, and Meda Chesney-Lind, eds. Invisible Punishments: The Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment. Washington: The Sentencing Project, 2002.

- Julie Reilly. “Sesame Street reaches out to 2.7 million American children with an incarcerated parent.” Pew Research Center. 22 June 2013. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/06/21/sesame-street-reaches-out-to-2-7-million-american-children-with-an-incarcerated-parent/ (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- National Conference of State Legislators. “Children of incarcerated parents.” May 2009. Available online: http://www.ncsl.org/documents/cyf/childrenofincarceratedparents.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Michael E. Roettger, Raymond R. Swisher, Danielle C. Kuhl, and Jorge Chavez. “Parental incarceration and trajectories of marijuana and other illegal drug use from adolescence into young adulthood: Evidence from longitudinal panels of males and females in the United States.” Addiction 106 (2010): 121–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joycelyn Pollock. Women’s Crimes, Criminology and Corrections. Long Grove: Waveland Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce A. Arditti. Parental Incarceration and the Family: Psychological and Social Effects of Imprisonment on Children, Parents, and Caregivers. New York: New York University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beth M. Huebner, and Regan Gustafson. “The effect of maternal incarceration on adult offspring involvement in the criminal justice system.” Journal of Criminal Justice 35 (2007): 283–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph Murray, David P. Farrington, and Ivana Sekol. “Children’s antisocial behavior, mental health drug use, and educational performance after parental incarceration: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 138 (2012): 175–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emily B. Nichols, and Ann B. Loper. “Incarceration in the household: Academic outcomes of adolescents with an incarcerated household member.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41 (2012): 1455–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross Parke, and K. Alison Clarke-Stewart. “Effects of parental incarceration on young children.” 2001. Available online: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/410627_ParentalIncarceration.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Megan Comfort. “Punishment beyond the legal offender.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 3 (2007): 271–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery D. Morenoff, and David J. Harding. “Incarceration, prisoner reentry, and communities.” Annual Review of Sociology 40 (2014): 411–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innocent Project. “About the Organization.” Available online: http://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/Exoneration-by-Year.aspx (accessed on 26 January 2015).

- Brandon Garrett. Convicting the Innocent: Where Criminal Prosecutions Go Wrong. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany Cox, Shannon Cunningham, and Joycelyn Pollock. “A closer look at prosecutor misconduct and good faith error.” Unpublished work. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mike Ward. “Tab for wrongful convictions in Texas: $65 million and counting.” Austin American Statesman. 10 February 2013. Available online: http://www.statesman.com/news/news/tab-for-wrongful-convictions-in-texas-65-million-a/nWLQM/ (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Franklin Zimring, and Gordon Hawkins. Imprisonment. London: Oxford Publishing Company, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nora Klapmuts. Community Alternatives to Prison. Hackensack: National Council on Crime and Delinquency, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- David S. Greenberg. The Problem of Prisons. Philadelphia: American Friends Service Committee, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- American Friends Service Committee. Struggle for Justice: A Report on Crime and Punishment in America. New York: Hill & Wang, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Gendreau, and Robert Ross. “Effective correctional treatment: Bibliotherapy for cynics.” Crime and Delinquency 25 (1979): 463–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Gendreau, and Robert Ross. Effective Correctional Treatment. Toronto: Butterworth Publishing, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Gendreau, and Robert Ross. “Revivication of Rehabilitation: Evidence from the 1980s.” Justice Quarterly 4 (1987): 349–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank Cullen. Reaffirming Rehabilitation. Cincinnati: Anderson, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ted Palmer. A Profile of Correctional Effectiveness and New Directions for Research. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Norval Morris. The Future of Imprisonment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- William G. Nagel. The New Red Barn: A Critical Look at the Modern American Prison. New York: Walker and Company, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Johnson. Hard Time: Understanding and Reforming the Prison. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Eric Schlosser. “The Prison Industrial Complex.” The Atlantic. December 1999. Available online: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1998/12/the-prison-industrial-complex/304669/ (accessed on 23 October 2014).

- Christian Parenti. Lockdown America: Police and Prisons in the Age of Crisis. New York: Verso New Left Books, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pat Nolan. “Testimony of Pat Nolan before the U.S. Sentencing Commission.” June 2014. Available online: http://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/amendment-process/public-hearings-and-meetings/20140610/TestimonyNolanRevised.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2014). [Google Scholar]

- David Weigel. “Forgive and forget: On drug sentencing, a growing number of Republicans are ready to shed the party’s law and order image in favor of reform.” Slate. 6 February 2014. Available online: http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/politics/2014/02/republicans_are_favoring_going_easy_on_drug_offenders_the_young_gop_leaders.single.html (accessed on 20 October 2014).

- Martha Moore. “Conservatives, liberals unite to cut prison populations.” USA Today. 17 March 2014. Available online: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2014/03/16/conservatives-sentencing-reform/6396537/ (accessed on 20 October 2014).

- Shane Bauer. “How Republican conservatives learned to love prison reform.” Mother Jones. April 2014. Available online: http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/02/conservatives-prison-reform-right-on-crime (accessed on 20 October 2014).

- David Dagan, and Steven M. Tele. “The conservative war on prison.” Washington Monthly. November–December 2012. Available online: http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/novemberdecember_2012/features/the_conservative_war_on_prison041104.php?page=all# (accessed on 20 October 2014).

- Newt Gingrich, and Pat Nolan. “Prison reform: A smart way for states to save money and lives.” The Washington Post. 7 January 2011. Available online: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/01/06/AR2011010604386.html (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Peter Betnartaug. “This time it’s different: The conservative response to Ferguson.” The Atlantic. August 2014. Available online: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/08/this-time-its-different-the-conservative-response-to-ferguson/378546/ (accessed on 21 January 2015).

- Ken Cuccinelli, and Deborah Daniels. “Less incarceration could lead to less crime.” Washington Post. 19 June 2014. Available online: http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/less-incarceration-could-lead-to-less-crime/2014/06/19/03f0e296-ef0e-11e3-bf76-447a5df6411f_story.html?hpid=z6 (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Alex Seitz-Wald, and Elahe Izadi. “Criminal justice reform, brought to you by CPAC.” The National Journal. March 2014. Available online: http://www.nationaljournal.com/domesticpolicy/criminal-justice-reform-brought-to-you-by-cpac-20140307 (accessed on 25 January 2015).

- Marc Levin. “Is ‘tough on crime’ no longer a talking point? ” National Public Radio. 20 September 2012. Available online: http://www.wbur.org/npr/161475623/is-tough-on-crime-no-longer-a-talkingpoint?ft=3&f=161475623 (accessed on 22 October 2014).

- Roy Wenzl. “Charles Koch’s views on criminal justice system just may surprise you.” Wichita Eagle. 27 December 2014. Available online: http://www.kansas.com/news/special-reports/koch/article5050731.html#storylink=cpy (accessed on 21 January 2015).

- Katherine Beckett, and Theodore Sasson. The Politics of Injustice: Crime and Punishment in America. Pine Forge: Sage Publications, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mike Ward. “Officials: Two Private Prisons to /Close.” Austin American Statesman. 11 June 2013. Available online: http://www.statesman.com/news/news/officials-two-private-prisons-to-close/nYH3w/ (accessed on 16 March 2015).

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pollock, J.; Glassner, S.; Krajewski, A. Examining the Conservative Shift from Harsh Justice. Laws 2015, 4, 107-124. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4010107

Pollock J, Glassner S, Krajewski A. Examining the Conservative Shift from Harsh Justice. Laws. 2015; 4(1):107-124. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4010107

Chicago/Turabian StylePollock, Joycelyn, Steven Glassner, and Andrea Krajewski. 2015. "Examining the Conservative Shift from Harsh Justice" Laws 4, no. 1: 107-124. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4010107

APA StylePollock, J., Glassner, S., & Krajewski, A. (2015). Examining the Conservative Shift from Harsh Justice. Laws, 4(1), 107-124. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4010107