Abstract

Access to justice has become an important issue in many justice systems around the world. Increasingly, technology is seen as a potential facilitator of access to justice, particularly in terms of improving justice sector efficiency. The international diffusion of information systems (IS) within the justice sector raises the important question of how to insure quality performance. The IS literature has stressed a set of general design principles for the implementation of complex information technology systems that have also been applied to these systems in the justice sector. However, an emerging e-justice literature emphasizes the significance of unique law and technology concerns that are especially relevant to implementing and evaluating information technology systems in the justice sector specifically. Moreover, there is growing recognition that both principles relating to the design of information technology systems themselves (“system design principles”), as well as to designing and managing the processes by which systems are created and implemented (“design management principles”) can be critical to positive outcomes. This paper uses six e-justice system examples to illustrate and elaborate upon the system design and design management principles in a manner intended to assist an interdisciplinary legal audience to better understand how these principles might impact upon a system’s ability to improve access to justice: three European examples (Italian Trial Online; English and Welsh Money Claim Online; the trans-border European Union e-CODEX) and three Canadian examples (Ontario’s Integrated Justice Project (IJP), Ontario’s Court Information Management System (CIMS), and British Columbia’s eCourt project).

Keywords:

technology; courts; civil procedure; court processes; e-justice; access to justice; Europe; Canada 1. Introduction

Those responsible for administering justice systems in many parts of the world are increasingly turning toward digitization and technological solutions, often with the goal of improving the efficiency and accessibility of justice [1,2,3,4,5,6]. As in other areas in which information systems (IS) have been developed and implemented, there is growing recognition among those working on e-justice initiatives [7] that principles relating to both system design itself (“system design principles”) [8], as well as to designing and managing the process by which systems are created and implemented (“design management principles”), can affect outcomes [3,9]. Moreover, a specialized e-justice literature has focused attention on the impact of law and technology considerations that are uniquely important to both defining what it means to have a successful outcome and enhancing the prospect for making positive choices about the design and implementation of justice sector initiatives in particular [10,11,12,13,14,15].

In this paper, we examine several e-justice initiatives in the EU and Canada with the objectives of illustrating and elaborating upon system design and design management principles in a manner intended to assist an interdisciplinary legal audience to better understand how these principles may affect a system’s ability to improve access to justice. We draw our examples both from functioning national and transnational e-justice systems in the EU, as well as contrasting Canadian experiences with integrated case management systems.

Our examples assist in illustrating some of the impacts of the system design and design management principles from the existing IS and e-justice literature, but also highlight three areas that may be especially important in terms of facilitating access to justice through technological systems, the first of which has not previously been emphasized in the literature: (i) complexity, cost, decentralized systems and the unavailability of paper-based alternatives can lead to differential diffusion and impacts among citizens and therefore impede realization of the justice value of equality of access; (ii) nimble, anticipatory forms of adaptation of legal norms, such as issuance of jargon-free practice directions made available in multiple languages, may better facilitate equitable diffusion and adoption of e-justice initiatives, as well as opportunities for communication and collaboration between key justice sector stakeholders; and (iii) iterative design processes can foster ongoing involvement of and collaboration with key justice sector stakeholders (particularly judges) that can materially affect the design and implementation of e-justice initiatives.

Section 2 summarizes the system design and design management principles focused on in the existing IS and e-justice literature, and explains the basis upon which we selected the six examples explored in Section 3 and Section 4. Section 3 [16,17] examines these principles using three European e-justice system examples: the Italian Trial Online (TOL), the English and Welsh Money Claim Online (MCOL), and the European trans-border system e-Justice Communication via Online Data Exchange (e-CODEX). Section 4 examines the principles using the two very different experiences of Canadian provinces Ontario and British Columbia (BC) with implementing unified case management and publicly accessible e-court systems: Ontario’s Integrated Justice Project (IJP), Ontario’s Court Information Management System (CIMS) and BC’s eCourt. Section 5 summarizes our observations about the impacts of the system design and design management principles with respect to the six examples discussed, and also suggests the importance of taking into account whether system design and design management are carried out in ways that facilitate equitable access to justice for all citizens.

2. System Design and Design Management Principles for Implementing e-Justice

In terms of system design principles, IS scholars have focused on bootstrapping through accessibility and simplicity, adaptability and modularization, while e-justice scholars have focused on the relationship between law and technology (including differences in timing between technological and legal change), and the use of technological and legal installed bases. Both IS and e-justice scholars have also looked beyond system design principles to identify design management principles aimed at minimizing psychological, political, and organizational barriers to success.

2.1. Bootstrapping through Simplicity and Accessibility

Hanseth and Lyytinen ([8]; see also [18,19]) suggest that in the initial phase of implementation designers should focus on a simple design that attracts a critical mass of users. Amassing a large user base is seen as desirable, not only to justify implementation costs, but also in order to demonstrate the “net benefits” [20,21,22] of the system. Initially, the system should target users’ problems and needs without being positioned as a complete solution, allowing for new system requirements to be added as the user base grows [8]. Growing the user base is linked to design simplicity and accessibility.

Simpler legal, technological, and administrative procedures are likely to be accessible to a wider range of users, thus, increasing the number of users the system may attract. Lanzara [23] posits that complex technological systems and difficult-to-understand laws may undermine attempts to reach a critical mass of users, especially given differing levels of technological literacy within any given population. Therefore, he suggests that in order to attract users, “we must design simple online procedures that deliver some value and are perceived by the users as attractive and convenient to use” ([23], p. 28).

While simplicity and accessibility are important, Lanzara [23] also stresses the need to achieve the right balance between a system’s maximum level of feasible simplicity and its maximum level of manageable complexity. As Lanzara notes, systems that are simplified to a point that undermines the functionalities, value, usefulness, and legal validity of a procedure are highly unlikely to attract users, and may in fact drive users to offline procedures ([23], p. 29). On the other hand, systems cannot be so complex as to be beyond the technological capacity of most users. Designers, Lanzara argues, should take into account the two thresholds, and implement strategies for keeping systems in the space between the maximum manageable complexity and minimum feasible simplicity. Overly simple systems should be revised by adding value, functionalities, and responding to more users’ demands, while complex systems may need to delegate functionalities to external agencies [23] that provide offline options for users without the necessary competencies [11] or that assist users in developing those competencies [23].

2.2. Adaptability and Modularization

Hanseth and Lyytinen [8] emphasize that system flexibility and rapid adaptation to meet new users’ needs and demands is essential to establishing critical mass. Both IS and e-justice scholars have focused on modularization as an important design principle. Hanseth and Lyytinen [8], Lanzara [23], and Lupo [24] have all indicated that system development based on an infrastructure composed of different loosely-coupled [15] layers connected by gateways can be essential to positive outcomes. Such an infrastructure fosters rapid evolution; a change in one system component does not require the modification of the entire infrastructure. Moreover, the failure of a single component in a modularized architecture does not undermine the entire system ([25,26]; [27], p. 473). Modularization has also been important to e-justice systems, such as the Case Law Exchange project (Caselex), which aim to distribute access to case law across national borders [28].

2.3. Relationship between Law and Technology

E-justice scholars note a potentially conflicting relationship between the regulatory regimes of law and technology, which are characterized by differently functioning logic [11,12,29]. Technology, like law, constraints and enables human action, and therefore entails its own normativity [30]. While law’s main objective is the legitimacy of actions (legal/illegal), technology’s logic is based on functioning (works/does not work) [31,32]. As a result, an e-justice service may be functional and efficient from a technological point of view, but not legally valid. Similarly, a legally legitimate technology may be considered technologically useless, unsuccessful, or ineffective. Scholars in this area have placed particular emphasis on timing differences between technological and legal change [33], and on the importance of addressing existing legal barriers to implementation [34]. Empirical studies and theoretical arguments [12,24] have stressed the importance of legal procedural change subsequent to, or in parallel with, the development of technology. Simply translating “offline” procedures into technological functions may foster inefficiency and unnecessary complexity.

2.4. Established Installed Technological and Legal Bases

Many IS, organizational theory, and e-justice scholars have focused on the design advantages of working with an existing installed base [8,11,25,29,35,36,37]. The term installed base refers to the technological solutions, institutional arrangements, organizational practices, and legal frameworks already in place when a new e-justice system is developed [11]. Hanseth and Lyytinen [8] posit that designers may reduce adoption barriers and safeguard capabilities already in place by basing the implementation stage of an information system on an existing installed base [38]. However, others have noted that relying on an installed base can also produce problems. For example, some installed base components are resistant to change and may hinder the evolution of an e-justice service. Lanzara [29] captures the dual character of the installed base: on one hand, it “constitutes a pool of available resources that can be turned into convertible and usable materials”; on the other hand, it can foster inertia and hinder “the development of new configurations” ([39], p. 19).

The principle of using an already existing installed base assumes great importance in the cases of trans-border systems due to the necessity of not dismissing systems already implemented at the national level. This has been the case both in relation to e-justice systems providing the public with online access to court processes, such as the e-Codex case (here analyzed in Section 3.3) and also in the case of other kinds of systems, such as the J-Web Collaboration Platform [40], a pilot system for the secure exchange of documents between Italian and Montenegrin justice operators. In both cases, designers opted for connecting already existing systems without dismissing the already implemented technology and the digital and normative procedures associated with them.

2.5. Design Management Principles

While system design and engineering are obviously important components in e-justice and other IS initiatives, so too are “psychological and political/power aspects” of technological change ([3]; [12], p. 257; [41]). This is particularly important for technological systems that are implemented within organizations (whether or not they may also someday be intended for access by others, including members of the public). Through this lens, it is essential to “take into account interactions between organizations, individuals and technology” [9,42]. Best practices here emphasize the advantages of a staged, iterative process that incorporates inclusion and feedback from key stakeholders ([43]; [44], pp. 394, 396), and expands prospects for stakeholder acceptance of technological change, as well as providing motivational opportunities through the achievement of incremental “wins” along the way ([9], p. 258; [41], p. 487). Managing the process of technology design and implementation to achieve small successes also has the potential to “increase ownership in and championing of the success of the [larger] project” ([9], p. 258; [45]). From the viewpoint of organizational psychology, consultation with stakeholders also enhances the prospect of user group acceptance prior to introduction of technology ([9], p. 259). With e-justice initiatives, this will often involve concomitant legal procedural change and adaptation [24] that is sensitive to each court’s own “identity, values and culture” ([3], p. S41), as well as intensive interaction with and involvement of the judiciary [9].

2.6. Selection of Examples

A wide and impressive array of e-justice systems from around the world and an equally impressive literature relating to those systems fully merit comprehensive review in monograph form [46,47]. However, given space constraints, our objectives in this paper are, of necessity, more modest. In Section 3 and Section 4 we examine six examples in order to illustrate and elaborate upon the system design and design management principles discussed above for an interdisciplinary legal audience, highlighting (where applicable) their potential impacts on equitable access to justice. We selected three European/EU trans-border and three Canadian e-justice system examples that involved court management of information and functionalities relating to legal cases (as opposed to case law), all of which either provided or aimed (at some stage) to provide access and functionalities not just for court administrators and judges, but also to members of the public. The specific examples were chosen based on the availability of information relating to them from previous analyses, which are specifically referred to in each section, and, in the case of e-CODEX, on the basis of Lupo’s direct involvement with the project.

3. European National and EU Trans-Border Cases

Section 3.1, Section 3.2, and Section 3.3 deal with three European case studies of e-justice systems: TOL from Italy, the English and Welsh MCOL, and the European trans-border system e-CODEX. The three make helpful comparators because they sought to digitize similar procedures (albeit in different jurisdictions) for e-filing requests for a payment order from a court, but employed different modalities that produced quite different results. Examining these differences assists in better understanding the potential role of design principles in achieving positive outcomes.

3.1. TOL: from Maximum Complexity to Feasible Simplicity

TOL [48] is an Italian information system for the electronic transmission of data, for accessing procedural documents and notifications, and for the payment of fees in civil cases. In 2001, the Italian Ministry of Justice (MoJ), following the success of PolisWeb (a system for external access to the Italian courts’ case management system—CMS) [49,50], started to plan the implementation of an ambitious e-justice project for civil justice by financing a feasibility study in the Courts of Bologna and Rimini. The feasibility study tracked the day-to-day application of the civil procedure, working practices, and roles of the numerous actors involved. The main goal of the project was the creation of the so-called paperless office [49], an e-justice system that allows complete electronic management of any type of civil proceeding, from case filing, to judgment, to final enforcement.

Due to delays in adjudicating the bid for the realization of the technological components [51], TOL was only released at the end of 2004 [52] and completed in 2005 [53]. The system was subsequently tested in seven courts through the establishment of local laboratories composed of public and private experts in informatics, administration, and law [51] with the aims of identifying and solving organizational and technical problems, and fostering the system’s adoption [54].

In order to meet the MoJ’s requirements, the system was designed with a broad range of functionalities: the digitization and e-filing of civil procedural documents, the exchange of information related to civil proceedings (for instance, granting external users access to a court’s repository), the management of case files for the court staff, electronic notification and communication to and from the court, and payments of amounts due and court fees [33,55].

TOL functionalities were accompanied by a complex architecture consisting of a set of internal and external components. External users (e.g., lawyers or experts) connected to the system through a dashboard (or webservice) linked to a point of access. Points of access guaranteed access to internal components, and connection to the Central Gateway that dispatched communications to the Local Gateways located at the court level. Local Gateways managed access to the Court Domain [56].

Unfortunately, the efforts made by the Ministry to develop the system did not bring about the expected results in terms of the system’s diffusion, and the courts involved in the piloting stage disengaged. The roll out of this first version of the system failed for several reasons.

First, the developers placed little attention on the bootstrapping of the system. Adoption was hindered by excessive initial costs that burdened external users. On the one hand, the access points’ hardware and software components were to be bought by bar associations in the free market. On the other hand, lawyers had to buy the software that allowed connection to the system (external users interface) and the device that allowed for digital signing of documents (which consists of a personal smart card and an USB card reader) [57]. These initial costs undermined adoption by external users. Additionally, the legal validity of documents exchanged through the system was subject to question. The Decree of the Ministry of Justice [58] that provided for the legal validity of TOL proceedings and documents exchanged through the system was issued only at the end of 2005, almost one year after the development of the project.

Despite the failure of the first version of TOL, in 2006, an initiative of the Court of Milan (which was not involved as a piloting court in the first stage) and of the Milan Bar Association (MBA) resurrected the project [51]. A mixed commission composed of court staff, lawyers, court ICT specialists, and specialists of the MoJ’s Directorate General worked on a simplified version of TOL. The new system digitized payment orders, a routine bulky procedure, which was one of the main functionalities of the original project. The payment order procedure allows a creditor to request that a judge order payment of a debt upon providing the court with written proof of the debt. Its first phase involves a repetitive set of tasks performed by court staff and a judge, without a hearing [59,60].

In the new TOL, lawyers, when filing a case, use the dashboard to draft the necessary documents, to attach digital copies of paper-based documents (scanned), to include proof of fee payment via a scanned bank transfer, and to apply a digital signature via an MBA-provided smart card. The documents are transmitted through the MBA-managed Point of Access to the court’s clerk who checks the package and sends the data to the judge. Judges use their dashboards to study the case, write and sign decisions, and transmit them to the record office where clerks digitally countersign them [51,61].

Despite initial skepticism from lawyers (in 2007, only 11% of payment orders were filed electronically), system use spread within the MBA so that by 2010, 60% of payment orders were filed electronically. Other Italian courts have followed the Milan example. By 2009, nine courts had implemented TOL, and by 2013 it was used in 32 courts [57].

TOL exemplifies how accessibility, bootstrapping, and diffusion of use may be hindered by a design that exceeds the threshold of maximum manageable complexity [23,51]. The initial project was designed to meet such a broad set of users’ demands that it became too complex for widespread use. As a result, the initial project was abandoned in favor of a scaled back version initiated by a single court and a local bar association. The complexity of the system was reduced primarily by limiting its functionalities, which in turn expanded its usability and fostered its diffusion among several Italian courts. Additionally, the maximum complexity manageable by TOL’s users has been reduced by delegating tasks to external agencies such as the bar association, the Innovation Office [62], and the Unified Front Office [23,63]. The MBA firmly supported the project, particularly by sustaining the costs of the point of access implementation and organizing courses that raised lawyers’ technological literacy related to the new system [51].

The TOL case also demonstrates the significance of the relationship between law and technology emphasized by Contini and Mohr [12]. Over-regulation and the slow change in legislation negatively affected the development and diffusion of the system. Fabri, in 2009, argued that the over-regulation of justice information systems, due in particular to legislators’ excessive attention to security and to the sensitivity of proceedings, increased the complexity of Italian e-justice services and hindered the initial diffusion of systems (bootstrapping) [64,65]. Furthermore, slow introduction of legislative change (such as the delayed issuance of the DM providing for the legal validity of documents exchanged via TOL) has delayed the use of e-justice systems.

TOL’s designers did not rely on a functioning installed base. Instead, the system was based on technological components built from scratch. Further, the implementation of some of the functional components of the infrastructure was left to private initiatives of local bar associations and of lawyers (point of access and external users interface). The project’s technological procedure relied heavily on an existing offline procedure known for its inefficiency and inconsistency [64]. In this case, reliance on the installed legal base constituted a disadvantage that hindered the smooth functioning of the infrastructure.

Over the years, some modifications were made to the system, particularly with respect to document exchange. In 2011, the MoJ issued a Ministerial Decree [66,67] that provided for the switch from the old ad hoc email application used by TOL (called CPEPT) to a new one based on the standard of “certified email” (CEM).

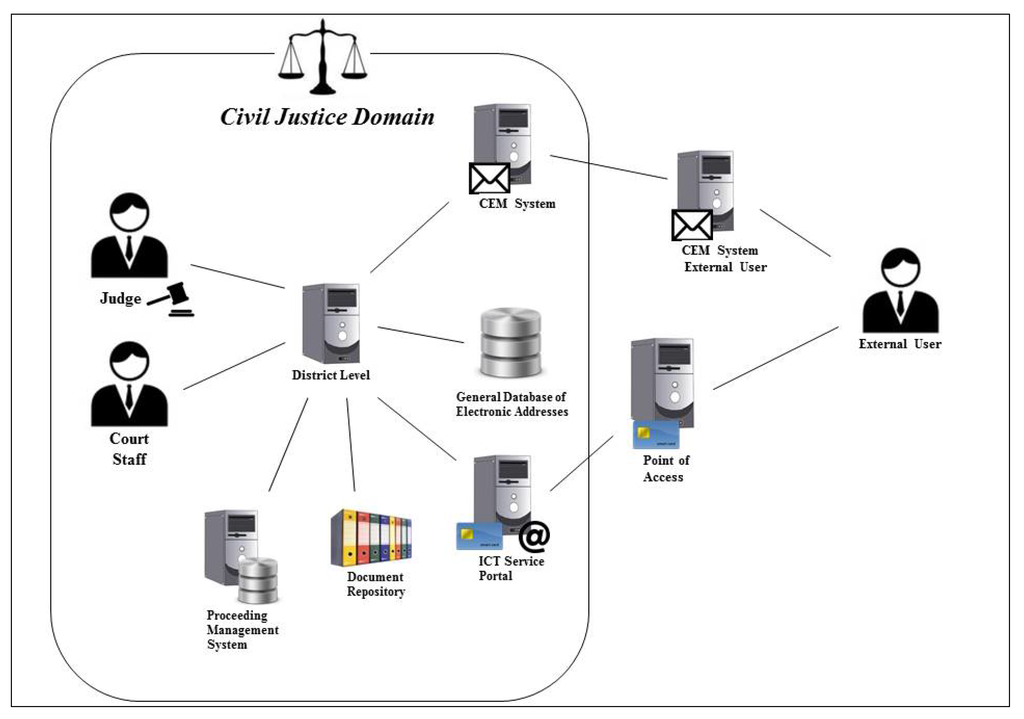

Following this change, the e-filing of documents is no longer pursued through the external user interface and the point of access. Instead, the lawyer uses a standardized CEM e-mail purchased from a private provider. However, the point of access is maintained in order to allow access to the court’s case management system data. The use of CEM led to some architectural modifications. The Central Gateway (located in Naples) was replaced by a Central CEM System (located in Milan), which controls access to the system, and the exchange of communications between the court and lawyers shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

The renewed TOL architecture with certified e-mail system [68].

These interdependencies between the system’s components mean that, in a modularized architecture, the modification of peripheral components may affect the entire architecture, thus raising costs of technological changes. On the other hand, the modularized architecture brought about a certain degree of adaptability to the system. This facilitated the initiative of the Court of Milan and the MBA to scale back the original TOL project from a set of several functionalities to a single one (the payment order). The adaptability of the system also recently allowed for the addition of new system functionalities: e-filing documents for civil procedures other than a payment order, communications between the court and the parties, and the communications between the parties.

The Italian experience with TOL also raises the issue of the organization of system architecture. In particular, it shows how a decentralized architecture can contribute to the unequal delivery of service to citizens of the same nation. In Italy, the jurisdiction for payment orders is generally based on the defendant’s address of residence, with some exceptions [69,70]. Although TOL was developed in a number of Italian courts, its adoption was left up to the discretion of various courts, bar associations, and lawyers. As a result, its diffusion is not assured in every jurisdiction (even with the downgrade of the initial project), thereby causing a disparity of service delivery between users who can apply for a payment order in Milan (where the system is active) and users whose case is within the jurisdiction of a court where TOL is not active. In that sense, TOL’s decentralized architecture presents the further problem of unequal access to justice in Italy.

A recent change in legislation addresses TOL’s unequal accessibility. Legislative Decree 179/2012 [71] provides for the mandatory use of TOL for the deposit of any judicial document in civil cases to an Italian court commencing in June 2014. The mandatory use of TOL may represent an opportunity for those courts that delayed the development of the system. On the other hand, it may pose a risk because courts not currently using TOL will have much less time to implement it than did the Court of Milan. It may be that some courts will be impeded by low technological literacy of users such as court staff, judges, and lawyers, which will make it very difficult to meet the deadline of June 2014. This could exacerbate the inequality between lawyers who operate in courts endowed with TOL systems and those who usually address courts in which TOL is not available, and in which it cannot be developed in such a short period.

3.2. MCOL: Building on an Established Installed Base

MCOL is an online service for the e-filing of money claims in England and Wales. It enables most English and Welsh citizens (with a few exceptions [72]) and lawyers to issue a money claim twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week through a user-friendly website. The website allows for filing documents, checking claim status, and requesting both judgment entry and enforcement (by way of a warrant of execution).

MCOL development started in 1999 and involved cooperation by different types of actors, from public to private: the Department of Constitutional Affairs (DCA; business area and IT team) and EDS (Electronic Data Systems), the private company that implemented and managed MCOL technological components [11,33]. DCA and EDS elaborated the business case and feasibility analysis. These two documents created the basis for the user interface prototypes (screen mock-ups) and for MCOL requirements [11,24]. The DCA office that dealt with required normative changes at the time worked on amending the Practice Directions (in particular, PD 7E), governing small claims procedures. This aspect of MCOL development demonstrates the importance of coordinated activity between multiple public and private stakeholders involved in system development. This strategy facilitates the parallel development of the multiple components of an e-justice system (technological, organizational, and normative).

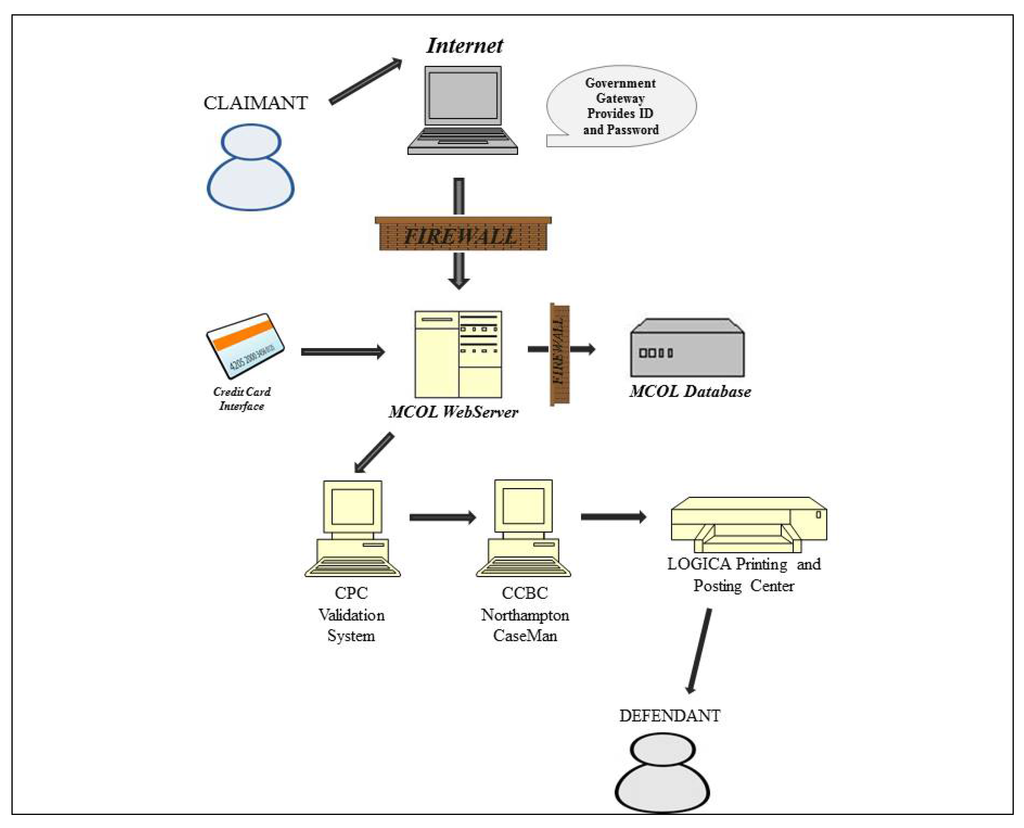

In order to issue a claim in MCOL, a claimant must hold a registered Government Gateway account that provides a single point of access to all government services [73]. The claim is issued through an eight step procedure that corresponds to eight screens on the website [74]. The claim is sent from the website to the court staff of an HMCTS (Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service) agency, the CCBC (County Court Bulk Centre), which manages it in the name of the Northampton County Court [11,37]. The Northampton County Court has jurisdiction over cases filed through the website, thus bypassing geographical jurisdiction rules that bind paper-based money claims. After CCBC staff check the claim, it is transmitted to the offices of Logica, the private company that manages the ICT components of MCOL, which then prints the claim and sends it to the defendant. After service of the claim pack, the defendant may respond to the claim online or by paper within fourteen days using the forms included in the claim pack. The defendant may pursue several actions by paper or online, including: asking for more time to pay, admitting only part of the claim, filing an acknowledgement of service in order to extend the time to respond to the claim, submitting a counterclaim, and disputing pursuit of the claim through MCOL (in which case, the claim is transferred to the competent court) [24]. The defendant may also admit the claim, in full, using paper.

MCOL also allows claimants to seek default judgment in the absence of a response from the defendant within a defined period, and to seek a judgment by admission where the defendant admits the claim. In MCOL, the claimant may also request a warrant of execution in cases where the defendant does not comply with a court judgment.

Users are more likely to e-file money claims through MCOL than to use paper based procedures. In fact, sixty-seven percent of money claims issued in England and Wales in the 2009–2010 period were issued online [24]. MCOL’s fees, which are, on average, 14.64% lower than those associated with traditional paper based procedures, encourage uptake [24].

MCOL is a classic example of building from a pre-existing and functioning installed base [9]. As demonstrated in Figure 2, MCOL developers exploited the functionalities of two HMCTS agencies that were already managing electronically filed money claims: the Claim Production Centre (CPC) and the CCBC.

CPC provides validation functions. MCOL also uses the CCBC’s existing information system, CaseMan, which manages bulk money claims. The exploitation of an already functioning installed base reduced implementation costs and barriers to user adoption, while also speeding up the development of the system. On the other hand, some installed base components, such as the CPC or the CaseMan [24], which were developed well before MCOL, are stable and resistant to change. This could hinder system evolution and MCOL’s capacity to adapt to new user demands in future.

MCOL’s development history also raises principles relating to the parallel change of laws and technology. The joint involvement of both the ICT and the policy office of the DCA led to a legislative change in parallel with the development of technology. The contemporaneous amendment of legal norms and technology reduced complexity, and fostered the implementation of an easy and functional online procedure. In particular, Practice Directions (PD 7E especially) issued by the Lord Chief Justice offered a nimble method for modifying procedural norms, without the lengthy process of involving both houses of parliament that would have been required to pass secondary legislation.

Figure 2.

Map of The MCOL organizational Architecture, adapted from Lupo [37].

MCOL was also designed with accessibility in mind, thereby facilitating bootstrapping. It offers a simple and understandable online procedure, governed by plain language Practice Directions, and offers the option of switching to an offline paper-based procedure at any stage of the claim. The accessibility of digital procedures and of the legal norms that discipline it contributed to reducing the level of maximum manageable complexity [23]. On the other hand, MCOL exceeds the threshold of feasible simplicity by covering the majority of the money claim, from filing to defendant’s options, and from judgement to execution, as noted above.

MCOL’s modularized structure facilitated the system’s evolution and problem solving, and meant that changes to one component did not affect the overall system, despite a transition of the management of the ICT elements of the system from one private entity (EDS) to another (Logica). Finally, MCOL’s centralized architecture fosters a homogeneous service for all the users of the online facility.

3.3. e-CODEX: Trans-Border e-Justice

e-CODEX is a large-scale pilot project co-funded by the EU Commission and coordinated by the Ministry of Justice of the German Land Nordrhein-Westfalen [75]. Actors from numerous groups are involved in the pilot: representatives of 22 national ministries of justice, the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE), the Conseil des Notariats de l’Union Européenne (CNUE), the OASIS non for profit consortium for the adoption of open standards in the Information Society, and the National Research Council of Italy (through two of its institutes—IRSIG-CNR [76] and ITTIG-CNR [77]). Project participants (the functionaries of all Member States’ Ministries of Justice and of other institutions such as CCBE) were organized into several working groups (called work packages (“WPs”)) covering the technical, organizational, legal, policy, and communication areas of the project [78,79]. The Management Board and the General Assembly [80,81] monitor and coordinate the work of WPs.

The e-CODEX governance architecture, characterized by the division of work and the participation of several actors with different backgrounds (ICT specialists, legal experts, stakeholders) introduces a potentially important design management principle related to the division of work among multiple specialist participants. Such division may represent an advantage for the design of an e-justice system characterized by the interconnection of legal, technological, and organizational components. On the other hand, the division of work, necessary for these kinds of large-scale projects, creates high interdependency between the teams. In e-CODEX, each WP’s performance and capacity to respect deadlines often depends upon the work of other WPs [82]. Accounting for the externalities that may arise in terms of interdependent actors in team-based e-justice projects is an important design management issue meriting further research.

e-CODEX’ project designers foresee the implementation of an infrastructure composed of several “building blocks” (in e-CODEX terminology) that supports the exchange of judicial data and documents between EU Member States [80]. This infrastructure has been shaped to allow legally valid electronic communication across different legal domains. The piloting of the infrastructure is done through “use cases”, which comprise the trans-border legal procedures on which the e-CODEX infrastructure is applied and tested. Use cases refer to two judicial areas: civil claims and cross-border mutual legal assistance in criminal matters. In the first area, e-CODEX will focus on the EU Small Claims procedure and the European Payment Order (EPO). In the second area, it will focus on the European Arrest Warrant (EAW), the secure cross-border exchange of sensitive data, and “financial penalties” (court fines related to a criminal case). Additional use cases are being considered both for the civil and mutual legal assistance in criminal matters areas.

Our analysis focuses on the EPO use case both because it is the first piloted e-CODEX project [80,82,83] and because it pertains to civil cases, which are the focus of our other case studies. The EPO procedure stated in Council Regulation 1896/2006 of 12 December 2006 allows creditors to file a claim without appearing before a court using a standardized form that can be filed and sent to the competent court [84]. If the court issues the payment order the defendant must be notified on the basis of national law [84]. The procedure will continue, depending on the defendant’s legal strategy, according to EU and relevant national law.

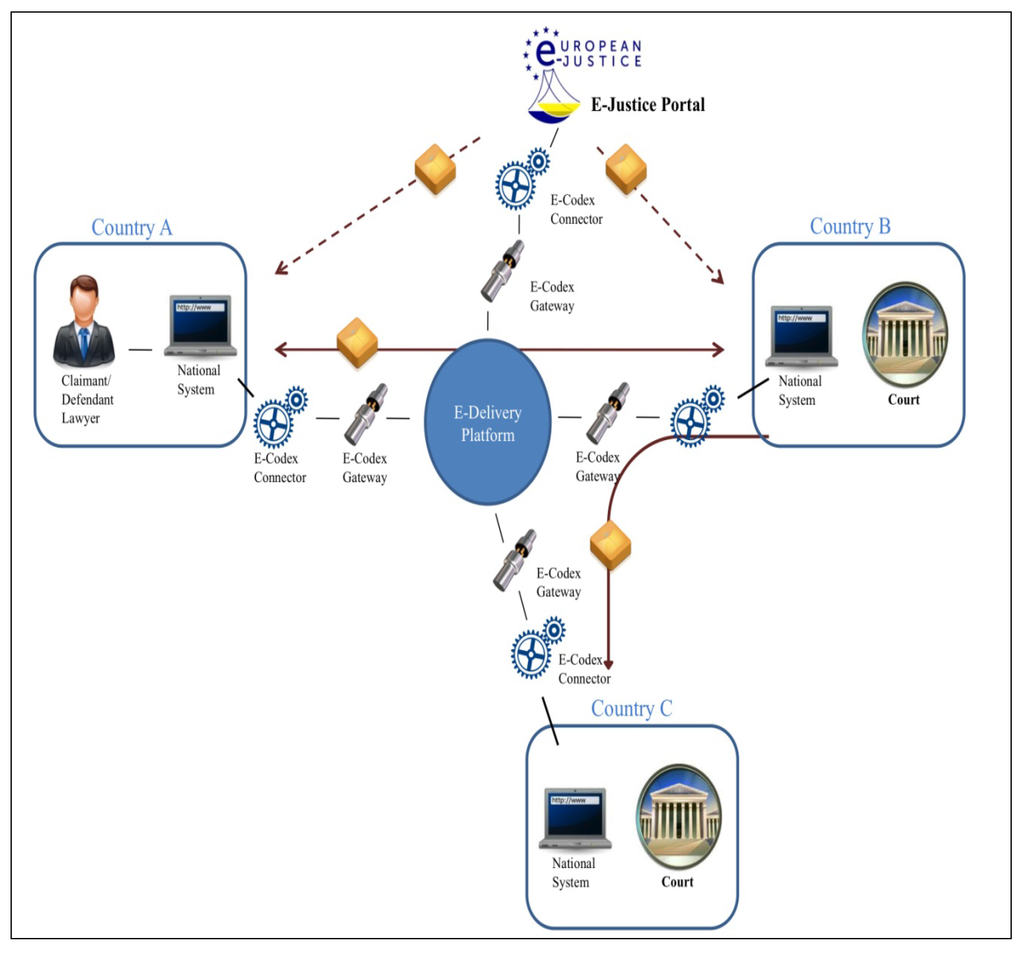

e-CODEX infrastructure permits the filing of an EPO claim through the local national system (for instance TOL in Italy). The system then transmits the claim through its architecture to the court with jurisdiction over the matter. e-CODEX system architecture is decentralized. It is composed of a set of components that allows the translation of a “sender’s” national format into the “receiver’s” national format without requiring any change to the e-justice service already implemented within a single nation [81]. Therefore, this multilevel architecture does not centralize procedure by bypassing already functioning national solutions. Instead, the system has been designed to facilitate communication between different national systems [85]. e-CODEX’ main components are the Service Provider, the Connector, the Gateway, and the e-Delivery platform.

Currently, the national e-filing system of each piloting country functions as a service provider through which documents can be transmitted into the e-CODEX system (e.g., the filing of a possession order). In the future, as shown in Figure 2, the European e-Justice Portal (intended to be an “electronic one-stop-shop in the area of justice” [86]) will be used to create a central European Service Provider, allowing all European citizens access to the e-CODEX system.

In the e-CODEX architecture (see Figure 3), the service provider is linked to the e-CODEX connector, which translates the document produced from the service provider according to national standards, to e-CODEX standards. The connector also performs a security check function. e-CODEX allows the exchange of documents created for different national e-justice solutions. These national solutions involve different types of security levels and signature verification systems. The connector verifies whether the national system that elaborated the document is endowed with an electronic signature or if it uses a different system for accounting. In the latter case, connectors verify whether this system respects the standards of an Advanced Electronic System (“AES”) [87,88] established in the European directive governing the digital exchange of documents [87].

Figure 3.

e-CODEX technological components [89,90].

In cases of documents accompanied by an electronic signature, the connector verifies (on the basis of Directive 1999/93/EC) whether the signature on the document is an AES or a “Qualified Electronic Signature” (QES) [91].

The connector accepts documents endowed with any typology of accounting system, and it also accepts both signatures even though the AES is less rigorous than the QES. The connector indicates the results of his verification in a PDF (human readable) and in an XML (machine readable) document called Trust-Ok Token, which is attached to the file sent. The file exchanged through e-CODEX’ architecture arrives in the judge’s hands whether or not the connector considers it trustworthy. The judge decides whether the file can be accepted by the tribunal, on the basis of what is stated in the Trust-Ok Token document.

National connectors are then linked to national Gateways whose function is to establish a link to other member states’ gateways and connectors, format the content of a message in the e-CODEX standards (eBMS 3.0) for communications between gateways, provide a transport signature, encryption, and a timestamp for outgoing messages, and send an acknowledgment of receipt for incoming messages [92]. Gateways are connected to the e-deliverable platform that permits the secure and reliable transport of data and files by encryption [73].

Five European countries have activated the pilot phase of the e-CODEX use case for EPOs in different modalities: Austria, Greece, Germany, Estonia, and Italy [73]. In Austria, and in Greece, the national e-filing systems have been connected to e-CODEX permitting both sending and receiving EPO claims. In both countries only one court processes all EPO cases coming from other European member states. Therefore, in each country a single national court centrally manages all cases over which Austria and Greece have jurisdiction. In Germany a single national court (the Wedding District Court) also processes all EPO cases incoming from European citizens, but Germany can only receive EPO cases through e-CODEX. The system is not available for German citizens or lawyers who want to send an EPO claim to a court in another piloting country [73]. Estonia developed an interface connected to e-CODEX, which allows citizens to file EPO claims to piloting countries’ courts based on the use of an already developed system of electronic signature [93].

In Italy, only the First Instance Court of Milan is connected to the e-CODEX system through TOL’s infrastructure (see Section 3.1) for judges and court staff. Unlike Greek and Austrian courts, the Court of Milan can only process incoming claims over which the Court of Milan has jurisdiction [73]. This limitation largely reflects the absence of a national Italian court that processes all EPOs. In Italy, incoming EPOs from European citizens outside of Italy must be processed by the Italian courts with jurisdiction over the particular case [94]. Therefore, while EPOs over which the Court of Milan has jurisdiction can be filed digitally, they have to be sent on paper if any other Italian court has jurisdiction over the claim. Additionally, Italy can only receive EPOs and cannot send them to other countries because only TOL’s application dedicated to court staff and judges has been connected to e-CODEX.

The e-CODEX system is strongly modularized, composed of several loosely-coupled sub-systems, which may foster adaptability by allowing each module to evolve independently without hindering the overall infrastructure. However, our analysis of TOL and MCOL and the e-justice literature [5,6,13,15,33,64,95] suggest that modularization alone does not considerably affect the system’s functioning. Centralized or decentralized architectures may be more important. As we have seen, e-CODEX’ decentralized architecture may afford different qualities of service depending upon which national service provider is utilized, thereby fostering unequal conditions between citizens of different member states. For example, EPO claims in Germany, Austria, and Greece benefit from being processed through one online system for any local jurisdiction, rather than being limited to particular courts within those jurisdictions. In Italy, however, the number of cases that will be processed through the system is limited since the Court of Milan may only receive claims over which that particular court has jurisdiction. Similarly, until e-filing systems are connected through the European e-justice portal, German and Italian citizens will be unable to use e-CODEX to digitally send EPOs to other nations. These disparities in national management of EPO claims within the e-CODEX architecture reflect and arguably exacerbate unequal access to justice.

In addition to technological and organizational issues, project participants had to address legal norms that govern the e-filing of trans-border claims. As a result, a Legal Sub-Group (LSSG) composed of legal experts was created to deal with the normative implications of the project and with existing laws. The LSSG drafted an agreement, which defines the principles of a circle of trust between the judicial authorities involved. The main principle on which the circle of trust is based states that judicial authorities should trust the information provided through e-CODEX and mutually recognize electronic documents exchanged within the existing legal framework. e-CODEX infrastructure is based on each member state’s trust of other member states on issues such as confidentiality, eIdentification, eSignature, eDocuments, ePayment, and transport [81,96]. On the basis of this principle, the responsibility for verifying the signature of an exchanged document lays with the sending country so that the receiving country need not repeat the verification process [97]. The agreement, which binds those participating in the pilot, raises Mohr and Contini’s principle about the relationship between law and technology [12]. While the agreement may facilitate future normative change at the European level, it is not a binding European regulation [80].

e-CODEX designers sought the benefits of bootstrapping through efforts to widely disseminate e-CODEX among potential users of the system by involving bar and consumers’ associations, presenting the project at conferences, and dedicating a single work package (WP2) to dissemination activities (Work Package 2-Communication) [98]. Moreover, this approach facilitates consultation with stakeholders, which the design management principles indicate can foster acceptance of technological change.

Despite these efforts, however, e-CODEX developers did not focus on other issues, which may limit the system’s accessibility to external users and users’ acceptance of technological innovation. For instance, they did not simplify the service provided, or work to limit the number of user demands that the system is designed to address. Since the e-CODEX infrastructure is based on pre-existing national e-filing services, its accessibility depends on the accessibility of those national systems. TOL, for example, cannot be considered an example of high accessibility, even though it will function through the Court of Milan as an e-CODEX service provider in the first wave of piloting.

Further, system accessibility will depend heavily on the EPO procedure that has been digitized. As demonstrated in prior studies [80,99,100], several features of existing EPO procedures limit the likelihood of their widespread use, including: difficulties for claimants in identifying the competent court, semantic issues (such as having to complete the claim form in one of the languages accepted by the competent court), and the payment of fees [80,99,100].

4. Canadian Examples—Case Management Systems in Ontario and BC

This section explores three examples involving case management systems in two Canadian provinces: Ontario and BC. All three involved complex integrated systems for case management and public e-services of the type that was eventually abandoned in favor of greater simplicity in the TOL example. Although Ontario and BC were both early experimenters with justice sector technology in Canada, BC is generally considered to have been much more successful in accomplishing case management system integration and public e-services than is Ontario [101].

4.1. Ontario’s Attempts to Integrate and Unify Case Management Systems

Ontario has undertaken two different projects aimed at developing a unified case management system: the Integrated Justice Project (IJP) (1996–2003) and the Court Information Management System (CIMS) project (2009–2013). Neither ultimately resulted in a unified case management system.

4.1.1. The Integrated Justice Project (IJP)

The IJP was initiated in 1996 to streamline then existing justice sector processes, to replace paper based systems with computer based systems, and to create a Common Inquiry System for criminal cases that would allow authorized persons from various justice areas to link to files (e.g., about witnesses, offenders, victims) held in other areas ([102], p. 283). It was expected to affect 22,000 government employees at 825 different locations in Ontario, in addition to police forces, judges, lawyers, and the general public. Like MCOL, the IJP involved public and private sector collaboration. The government and a private sector consortium led by EDS Canada Incorporated (EDS) were both to provide human and financial resources, sharing in “resulting risks and rewards” ([102], p. 283).

However, the IJP was terminated in 2002 due to “significant cost increases and delays”, with the estimated cost of completion doubling from 1998 to 2001, while expected benefits in the same period declined by more than 25% ([102], p. 283). When the work term for the project expired, only the Computer-aided Dispatch and Records Management systems for the police and the Offender Tracking Information System for corrections had been implemented. The Digital Audio Recording, E-file, and Civil and Criminal Case Management System was incomplete and would not be completed as originally planned, and the Common Inquiry System was never achieved ([102], p. 283). EDS ultimately sued the government. The case was reportedly settled by a government payment of $63 million. As then Attorney General David Young said, “we spent a lot of money and had very little to show for it” [103,104].

The IJP case study highlights two key principles: simplicity in design and careful management of the process of designing and implementing technological change, but also suggests the complicating role that sheer scale can play. The Ontario Auditor General stated that the original business case upon which approval had been based had an “aggressive schedule based on a best-case scenario”, and failed to recognize the “magnitude of change introduced by the Project, the complexity of justice administration…or the ability of the vendors [to deliver the computer systems on time]” ([102], p. 283). Further, project management and senior court management had never agreed upon whether the expected court benefits (70% of the overall projected benefits) were actually realizable ([102], p. 284). Other problems identified by the Auditor General included that the billing rates by consortium staff were three times those charged by the Ministries’ staff “for similar work”, and security systems were weak so that confidential data “was vulnerable to unauthorized access” ([102], p. 284).

A special task force (the Ontario Task Force) commissioned by the Minister of Government Services to “offer advice on ways to improve the management of large-scale IT projects in Ontario” reviewed the IJP. Noting that at that time “approximately 40% of IT projects still f[e]ll short of plan in some way”, it was also recognized that IT projects rarely failed due to technology alone ([105], pp. 6, 18). Among other things, the Ontario Task Force called for heightened accountability at senior management levels and formalization of a “gateway review process” so that projects would be broken into stages and reviewed at each stage before being allowed to pass to the next stage ([105], pp. 18–19, 24–25). It also recommended that procurement processes be revised to separate design from build, so that the best vendor can be selected for each phase, to ensure that the business people for whom systems were sought to be procured were driving the project rather than it being driven by procurement leads ([105], p. 26), and that contracts contain “off-ramps” that allowed for the option of terminating a vendor or a project at different stages along the way ([105], p. 27). Off-ramps, it suggested, worked best with “small, manageable projects [that] allow for benefits to accrue along the way while keeping open the option of an exit, thus reducing overall risk ([105], p. 27).” The Ontario government committed itself to implementing the Task Force’s recommendations [106] and publicly updated its I & IT Project Gateway Review Process in 2007 [107].

Sheer scale and complexity may also be key stumbling blocks to an integrated case management system in Ontario. As a Ministry spokesperson noted in 2012:

Ontario is one of the largest court jurisdictions in North America with extensive criminal, family, civil, small claims, and provincial offences operations…In such a complex environment, modernizing the support systems is a large undertaking[108,109,110].

Given this scale and complexity, it may be difficult to identify systems from other jurisdictions adaptable for use in Ontario. Challenges posed by scale and complexity may have also been exacerbated by the lack of a “champion” in government to move a unified case management system forward ([109], p. 26).

4.1.2. Court Information Management System (CIMS)

Although the design and process management flaws cited as complicit in the IJP’s failure seemed to have been addressed in Ontario’s later attempt to develop an integrated Court Information Management System (CIMS), that project also ended without producing a single unified system. In 2009, the Ministry of the Attorney General approved $10 million in funding to create CIMS, with the first version of the system forecast for release in spring 2012 ([109], p. 26). CIMS was ultimately intended to permit enhanced functionality such as e-document management, court scheduling, financial and automated workflow capabilities, and the introduction of online services to the public ([109], p. 26), but first required changes to existing case tracking systems ICON and FRANK [108]. Steps were taken to implement CIMS, including converting all courts to existing installed technological bases ICON and FRANK, updating ICON for enhanced web capability, and updating FRANK to reflect amendments to the Rules of Civil Procedure and to allow for searches at courts province-wide and for production of detailed reports ([111], pp. A5, A17, 48). The Ontario government reportedly spent $13.8 million on existing legacy systems ICON, FRANK, and its Estates Case Management System, and $9.9 million developing CIMS between 2006 and 2012 [108,112].

However, in December 2013, the Ministry of the Attorney General cancelled plans to go ahead with CIMS “as originally conceived” [113]. Instead, a ministry spokesperson advised that in order to “respond to demands for more timely modernization in courts, the ministry has made investments in its current systems to enable a much more agile and responsive approach to its transformation agenda” [113]. As a result, the Ministry has indicated that it will focus on “taking a more incremental approach to deploying technology, including enhancing the capability of the case tracking systems and scheduling” [113]. It will also prioritize remote court appearances, “self-service for filing court documents”, and increasing the availability of information online [113]. Further, the Ministry emphasized its progress on other discrete e-justice initiatives, including implementation of a Digital Audio Recording System (DARS) in 1000 courtrooms across Ontario, the replacement of five case-tracking applications with FRANK, and the justice video network that provides video conference services connecting Ontario courtrooms with “witnesses, interpreters, and the accused from almost anywhere in the world” [113].

Simplicity and modularity seemed certainly to be at play in CIMS’ design, which included four modules to be developed over time: portal technology, document management, common scheduling, and financial management ([114], slide 4). The single portal was intended to simplify by offering one “look and feel” and to “improve user access, security and navigation” by allowing for one entry to multiple applications without the need for separate passwords for each system ([114], slide 5). While the system was intended to simplify certain procedures, however, the overall vision involved a complex system with features not unlike those initially forecast in the first failed attempt at TOL.

CIMS aimed to draw on existing provincial investments (and related internal government expertise) in legacy systems consistent with principles identified by numerous IS and e-justice scholars [8,35]). At the same time, CIMS seemed poised to minimize the kinds of disadvantages Lanzara [29] suggested may flow from full reliance on installed bases by planned adaptation and augmentation of that installed base. A single portal was intended to improve workflows and reduce errors and duplication by avoiding the need to search multiple applications that were characteristic of the existing installed technological base ([114], slide 5). Similarly, the document management module ([114], slide 6), financial management module ([114], slide 7), and scheduling module ([114], slide 8) would have offered a unified approach in each of those areas, thereby reducing duplication and reliance on paper-intensive processes. In these ways, CIMS was not simply designed to translate the installed base offline (allegedly inefficient) procedures into an online system, but rather to improve the procedures themselves, an approach the e-justice literature [12,24] identifies as a contributor to success.

This modular approach to design, following an iterative process and staged implementation using “approved, powerful, cost-efficient software development tools” ([114], slide 9) was intended to provide a base for future functionalities that would accommodate the needs of other user groups. For example, portal technology might in future facilitate self-directed small claims matters, the document management component could facilitate e-filing and e-notices, the financial component would afford online payments, and the scheduling component could permit online booking ([114], slide 10). Again, these features appeared to offer the benefits of bootstrapping identified by Hanseth and Lyytinen [8]. Nonetheless, CIMS did not come to full fruition.

4.2. British Columbia’s eCourt Initiative

By comparison to Ontario (and to TOL), BC’s trajectory toward an integrated case management system and publicly accessible e-services has been rather straightforward. In fact, critiques of Ontario’s situation often refer to the relatively less expensive, but more successful integration of case management systems in BC that eventually paved the way for public access to court documents and e-filing capabilities at all levels of BC courts (including, most recently, the Court of Appeal [115]).

BC’s eCourt program (which has now been replaced by the Court Administrative Technology Suite) was a joint initiative of the Ministry of the Attorney General of BC, the BC Court Services Branch, and all three levels of the BC judiciary (provincial, superior, and appellate courts). The program’s goal was an integrated system providing seamless coordination from e-documents created in law offices to the registry to the judicial desktop and the courtroom, which would include eCourtrooms that have a complete e-court file, an integrated DARS allowing for real time monitoring of the courtroom in the Registry, e-exhibit management, and links to the civil and criminal court information systems [116]. Ultimate goals included supporting public access (including e-searches, online document purchase, court lists, e-filing and a filing assistant), out-of-court access by justice partners such as crown attorneys, police and defense counsel (including document production, routing, signing and distribution), and in-court functionalities such as those mentioned above [117]. Despite the breadth and complexity of the vision, however, design and implementation progressed in incremental stages over a fifteen-year period.

The eCourt initiative underscores the benefits of a “well articulated, documented vision” that allows everyone to understand “where you are going and why” ([117], slide 23). Perhaps equally significant, however, was incremental development of the components that would eventually comprise the overall system, beginning with two key modules that formed the installed base onto which functionalities were layered to gradually expand both the system and its user base, allowing for the benefits of bootstrapping identified by Hanseth and Lyytinen [8].

The Justice Information System (JUSTIN) was the first module in the installed base. Developed in 2001, JUSTIN is an integrated criminal case management system used in BC’s provincial and superior courts. Designed by a private vendor, Sierra Systems [118], JUSTIN, among other things, allows for authorized users of numerous justice sector partners (such as the police, corrections, ministry of justice, and federal crown counsel) to access a variety of information, including reports to crown counsel and an accused’s criminal court file history [119,120]. Authorized users can also gain real time access to court scheduling information. Data is entered only once and then made available to all authorized users. JUSTIN can produce standard format documents and reports, and features security and audit trails allowing tracking of changes and deletions of data ([119], pp. 11–12; [121], p. 85).

The Civil Electronic Information System (CEIS) was the second module that became part of the installed base. Developed in 2003, CEIS is a customized case management system facilitating information management for civil, family, and estates cases in the superior and provincial courts of BC. In 2004, a third module, the Web-based Court of Appeal Tracking System (WebCATS) was implemented to allow for tracking and management of cases in the BC Court of Appeal. WebCATS became available to the public in 2005 through BC’s Court Services Online (CSO) initiative, which is described below ([122], p. 18).

JUSTIN and CEIS are systems that evolved from case tracking mechanisms to case management mechanisms, with the addition of functions such as a document repository, and document and workflow management ([117], slide 4). These systems then became the “essence” of BC’s eCourt project: “an electronic court file with electronic document management and hooks from front end systems into back end case management” ([117], slide 4). They provide the backbone for CSO, a JAVA based application that enables e-search (of civil data and documents, provincial criminal data), online document purchase, access to restricted files (where authorized), as well as access to daily court lists, an online filing assistant for provincial small claims court, and (since 2009) e-filing of PDFs of most Provincial Court and Supreme Court documents by registered CSO account holders using electronic signatures ([117], slide 5; [123]).

In 2009, the Integrated Courts Electronic Documents (ICED) Project expanded the user base of JUSTIN by linking it with the Sheriff Custody Management System and the Corrections Offender Management System. ICED allows for e-faxing between justice partners who are unable to link directly to the case management system ([117], slide 15). It uses an ORACLE database to store PDFs, Web Methods for workflow, i-keys with Entrust Software for digital signatures, and authentication and signature pads to get the electronic signature of an accused.

In terms of in-court functionality, the eCourt initiative envisioned a full e-court system to include transcript management, evidence, and associated materials, and to integrate external resources ([117], slide 19). However, in keeping with best practices around paying attention to the relationship between law and technology [12,17], and updating the installed legal procedural base, initial focus was placed on consultative development of practice directions with respect to e-hearings that were issued prior to e-hearings becoming widely available [124,125]. Similarly, it was also understood that amendment of procedural rules and legislation would be essential to the success of the e-filing initiative, and to ensuring a proper balancing of privacy and access in e-searching functions available to the public, and in expanding user access to sensitive information such as that contained in JUSTIN ([117], slide 23).

Subsequent additions to facilitate in-court technologies included conversion to DARS [126], roll out of evidence presentation carts, and revisions to the role of court clerk ([117], slide 19). Thereafter, functionalities that integrated DARS and case management systems, eliminated paper forms in court rooms, generated exhibit and witness lists for multi-day events, and tracked and managed exhibits were focused upon ([117], slide 20). The BC Supreme Court held its first fully electronic proceeding in 2011 [127], while the BC Court of Appeal conducted its first entirely electronic appeal in 2012. The appeal was facilitated by an e-Appeal Working Group comprised of judges, Court Services Branch employees, a senior policy analyst, and technology and business consultants [122]. Judicial involvement throughout the planning stages in the first e-appeal meant that each of the five judges sitting on the appeal had workspaces organized to suit their individual technological needs and preferences [122].

The eCourt initiative overall demonstrates the critical importance of design management principles that facilitate user acceptance and adoption. Here, incorporating a wide variety of stakeholders (especially the judiciary) in the planning and implementation process was understood as essential ([117], slide 23). Stakeholder consultation and collaboration facilitated better understanding of the “diversity of the client base”, the concomitant diversity of needs and interests of that base, and consistency between system functions and workflow processes ([9], pp. 265–68, 276; [117], slide 23). Attentiveness to user needs and interests is consistent with the design management principles within the IS and e-justice literature, both in relation to transformations in service delivery, but also in terms of human resources ([9], pp. 279–280; [41], p. 487; [117], slide 26).

5. Conclusions

Our analysis of these six European and Canadian e-justice examples illustrates and elaborates upon the ways in which design and design management principles from the IS and e-justice literature can influence the performance of e-justice systems. However, our analysis also highlights additional factors, as well as the ways in which previously identified principles may affect the justice value of equality of access. Therefore, reflection on these principles is not important simply for the sake of thinking about whether, for example, a system will become widely diffused, but also because of the connections between the principles, e-justice systems, and the ultimate goal of achieving equitable access to justice. In this conclusion, we will first highlight some of the key illustrations of the principles from our examples and then in Table 1 (below) provide a comprehensive overview correlating each of the principles with each of our examples.

Many of our case studies confirmed the benefits of accessibility and simplicity as effective mechanisms for bootstrapping e-justice systems in ways that increase system diffusion [8]. MCOL has achieved substantial diffusion by being accessible on a plain language website available for use by all English and Welsh residents. Moreover, it digitizes a single, rote process that does not require a court hearing, and improves equitable access by offering lower filing fees for the online process than its offline equivalent, while at the same time allowing users (such as those who are less technologically literate) to switch to the paper-based procedure at any stage of the process.

In contrast with MCOL, the IJP, CIMS, and the first iteration of TOL demonstrate the negative impacts of unmanageably complex systems on diffusion [23]. The scale and complexity of IJP appears ultimately to have contributed to its demise even before implementation (and perhaps also to that of CIMS). TOL became more widely diffused only when minimized functionalities led to reduced system complexity and the MBA reduced the burden on users by supporting activation costs and technological literacy initiatives that improved system uptake.

Examples such as eCourt and MCOL illustrate the way in which modularization (as discussed by Hanseth and Lyytinen [8], and Lanzara [23]) can facilitate evolution. Interestingly, modularization appears to have permitted eCourt to mediate the complexity of the initiative’s ultimate vision by allowing for staged development that permitted functionalities to be layered on gradually rather than all at once. The MCOL example illustrates that modularity may also be effective in allowing components of a project to move forward independently from other components (which can be especially important where certain components are controlled by private sector partners).

However, the cases of TOL and e-CODEX demonstrate that evolution cannot be presumed to flow from modularity. Unlike eCourt and MCOL, TOL and e-CODEX are decentralized systems. While centralized systems offer homogeneous implementation of the same technological design and nominally equal access to all users, decentralized systems such as TOL and e-CODEX permit different delivery of the same design, and consequentially foster differences in performance and accessibility among citizens. The role of centralization in system diffusion and equality of access is not well developed in the existing literature and merits further research and consideration.

MCOL, eCourt, TOL, and e-CODEX illustrate the importance of the parallel change of norms and technology [12] in order to reduce system complexity and open space for design solutions that would modify pre-existing legal rules and norms in a normatively acceptable way. MCOL and eCourt were facilitated through procedures governed by understandable and jargon-free practice directions (or rules of civil procedure) created through stakeholder consultation rather than lengthy formal procedures. In contrast, in TOL’s case, a complex installed base of procedure and regulations that were sometimes in conflict with one another [33] impeded system development and uptake. Moreover, the failure to adapt pre-existing regulations to validate the digitized process significantly delayed TOL’s use. Similarly, although the circle of trust agreement between piloting nations facilitates e-CODEX by binding the receiving nation to trust the e-signature verification process of the sending nation, extension of e-CODEX beyond the pilot stage will require regulatory amendment.

Table 1.

Overview of system design and design management principles in the six EU and Canadian examples reviewed.

| Design Principle | TOL | MCOL | e-Codex | IJP | CIMS | eCourt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bootstrapping and accessibility | Reduction of original project’s functionalities allowed bootstrapping, raised accessibility and reduced overall complexity. Also, reduction of complexity by delegating to external agencies. | Rapid diffusion thanks to easy to use service, understandable procedure, switch to paper-based procedure. Low complexity of the system. Not below the maximum feasible simplicity: the system covers the entire procedure. | Main focus on advertising the project between potential users. Low focus on reducing system’s complexity and making procedure accessible. | Bootstrapping not verified. High complexity due to the extent of Ontario jurisdiction and to the many objectives of the project (CMS for criminal justice with a common inquiry system accessible to lawyers, staff, judges, and public). | Intention to simplify by creating a single portal for multiple applications first to facilitate internal access with a view to later facilitating public access to certain aspects. | Bootstrapping through the expansion of installed base’s users base. System above the maximum feasible simplicity: the system covers many functions and procedures. |

| Adaptability and Modularization | Modularized system: modification of peripheral components affects whole architecture; however, high adaptability. | Very adaptable (changes in one module did not affect the system): e.g., modification of the accounting system. | Modular architecture: this should ensure the adaptability of the system. However, unequal accessibility of the system. | Modularized systems including for Computer-aided Dispatch ad Records Management, Offender Tracking, DARS, e-Filing, and separate civil and criminal case management systems intended to be integrated with a Common Inquiry System. | Modularized, four modules to be developed: portal technology, document management, common scheduling, and financial management. | Modularized: criminal and civil case management modules foundational to the system. |

| Law & Technology | Hypertrophic regulation, legal formalism, and delays in disciplining the first version of the system contributed to the abandoning of the first project. | Legal change in parallel with technological change. | Simply inscribed EU procedure for possession orders into technology; normative change only regarding an agreement that disciplines the functioning of the system. | N/A | Goal to rationalize and improve upon existing procedures; systems updated to reflect changes in procedural rules. | Normative change in parallel with consultative development of practice directions. |

| Installed Base | Most of the installed base has been implemented from scratch, however, legal installed base remained (installed base that hindered system’s performances). | Used agencies that already were dealing with claims issued electronically: CPC (Claim Production Centre) and CCBC (County Court Bulk Centre). | Installed base constituted by the national systems connected through e-Codex and by the European procedure for possession claims that is affected by many issues. | Intention to replace existing installed base. | Use and update of existing installed base. Project developed by drawing on existing provincial investments (and related internal government expertise). | Creation of two modules that became an installed base: Justice Information System (JUSTIN) and the Civil Electronic Information System (CEIS). |

| Design Management Principles | Both for the first version and for the simplified version: involvement of judges, court staff, lawyers, MoJ officials. Involvement of Milan Bar Association, creation of the Innovation Office. | Involvement of stakeholders during and after development; coordinated activity of multiple private and public actors. | Bootstrapping through involvement of stakeholders: consumers associations, bars, judges. Division of work among multiple specialists with different backgrounds. | Weak interaction among key stakeholders, including failure to agree on feasibility of realizing expected benefits. Involvement of public and private actors, and later proposals for more flexible “gateway review process” for contracting. | Iterative process and staged development allowing for stakeholder input. Involvement of public and private actors. | Stakeholder consultation and collaboration facilitated understanding of the diversity of the user base and support from key actors (especially the judiciary). |

| Architecture | Decentralized: system not present in all Tribunals. Delivery of service is decentralized. | Centralized system: only one website, one agency that manages the claim (CCBC), one court that issues it (Northampton County Court). | Decentralized system. Connects national e-filing systems to Court’s system for cases management. Potential disparity of service between European citizens. | Centralized: intended to cover entire province of Ontario. | Centralized: intended to cover entire province of Ontario. | Centralized: covers the entire province of British Columbia. |

| Project outcomes | First version abandoned. Simplified version active in 32 courts (2013 data). | System very diffused: use of the online procedure overcame the use of the paper based procedure (60% in 2009–2010 period). | Not verified. Pilot became a running project only recently. | Project terminated in 2002 due to significant cost increases and delays. | In December 2013, Ministry of the Attorney General cancelled plans to proceed with CIMS, opting instead for a strategy of incremental development of certain technologies such as videoconferencing. | System used across British Columbia, incorporating not only case management functions internal to courts but also online public access to court records. Project now superseded by Court Administrative Technology Suite. |

The implications of building on an existing installed technological or legal base [8,11,29,35,36,37] were also highlighted in our examples. While MCOL’s reliance on existing installed bases operated by CCBC decreased implementation costs and barriers to adoption, eCourt also benefited from reduced adoption barriers by developing and using an installed base before layering on additional functionality. On the other hand, the IJP and CIMS cases demonstrate the difficulties of working from an outdated installed base of legacy systems, while TOL’s and e-CODEX’ reliance on installed legal bases limited citizens’ equal access to justice.

All of our examples emphasize the importance of design management principles, such as iterative design processes that foster ongoing involvement of, and collaboration with, key stakeholders [9,41]. eCourt also illustrates that consultation with, and understanding of the needs of, judges and other court staff can be critical to achieving positive outcomes in the design and implementation of e-justice initiatives. Similarly, TOL highlights the ways in which engagement with potential system users through bar and consumer associations can assist in system diffusion and acceptance [98].