Abstract

Debates about the diversity of the judiciary in the UK have been dominated by gender, race and ethnicity. Sexuality is notable by its absence and is perceived to pose particular challenges. It is usually missing from the list of diversity categories. When present, its appearance is nominal. One effect of this has been a total lack of official data on the sexual composition of the judiciary. Another is the gap in research on the barriers to the goal of a more sexually diverse judiciary. In 2008 the Judicial Appointment Commission (JAC) for England and Wales undertook research to better understand the challenges limiting progress towards judicial diversity. A central gaol of the project was to investigate barriers to application for judicial appointment across different groups defined by “sex, ethnicity and employment status”. Sexual orientation was again noticeable by its absence. Its absence was yet another missed opportunity to recognise and take seriously this strand of diversity. This study is based on a response to that absence. A stakeholder organisation, InterLaw Diversity Forum for lesbian gay bisexual and transgender networks in the legal services sector, with the JAC’s approval, used their questionnaire and for the first time asked lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender lawyers about the perceptions and experiences of barriers to judicial appointment. This paper examines the findings of that unique research and considers them in the light of the initial research on barriers to judicial appointment and subsequent developments.

1. Introduction

In 2008 the Judicial Appointments Commission for England and Wales (JAC) commissioned a piece of research to examine barriers to application for judicial appointment. Its overarching purpose was to generate data to help the JAC better understand what attracts people to apply for judicial office and what deters people from applying ([1], p. 1). The particular goal of the project was to investigate these barriers across different groups. The groups were defined by “sex, ethnicity and professional status” ([1], p. 8). 1 This connected with the JAC’s statutory duty under section 64 of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 to, “...encourage diversity in the range of persons available for selection for appointments.” The findings of the Barriers to Application for Judicial Appointment Research Report (Barriers Report) [1] generated much needed diversity data, with over 2000 responses. This article is about one response to that report. The research did not include sexual orientation as one of the strands of diversity. One of the primary aims of the research was to be able to look at differences between key groups. The phrase “key groups” refers to categories of persons “under-represented in the current judiciary” ([1], p. 6). Lesbian gay and bisexual (LGB) were not considered a “key group” despite the fact that at the time the judiciary appeared to be 99.9% heterosexual. In response to the publication of the JAC study, a lesbian gay bisexual transgender (LGBT) legal sector networking group, the InterLaw Diversity Forum for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Networks (InterLaw Diversity Forum)2, with the support of the Equality and Diversity Committees of the Law Society and the Bar Council, approached the JAC with a proposal; to use the JAC Barriers Report questionnaire in a new study to generate data about the ‘missing’ LGBT experiences and perceptions of barriers to application for judicial appointment. The JAC generously gave its support. The InterLaw Diversity Forum questionnaire closely followed that used in the JAC Barriers study and a number of questions were added to explore particular sexual equality issues in the specific context of judicial office and the selection process. Before discussing the detail of the InterLaw Diversity Forum research findings a brief overview will be provided of recent judicial diversity reforms and initiatives. What profile has sexual orientation had in the judicial diversity debates and initiatives? What data exists on the sexual diversity of the judiciary? Why is sexual diversity data important within the judicial diversity policy domain? Turning then to the InterLaw Diversity Forum research, after a brief introduction to the methods used to contact LGBT respondents and some information about the demographic profile, an overview, touching on three key areas of the research, will be provided. This is followed by a commentary on the findings. Post 2010 developments will be considered and the essay will conclude with some modest recommendations for change.

2. Background: Recent Judicial Diversity Reforms and Initiatives

In 2010 the then Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Lord Judge, in his “Judicial Studies Board Lecture”, noted the judiciary in that jurisdiction has been undergoing major reforms some of which he described as ‘revolutionary’ ([2], p. 4). A key driver of the ‘revolutionary’ changes is the Constitutional Reform Act 2005. One of the reforms introduced in that Act of relevance here is the established a new judicial appointments mechanism: the Judicial Appointments Commission. Connected to that is section 64 of the Act. It introduces judicial diversity as a particular goal attached to the work of the JAC. ‘Diversity’ occupies a special position in the new appointments system. The legislation draws a distinction between judicial appointment, which is to be based solely on merit, section 63(2), and the process leading up to appointment. ‘Diversity’ is a goal associated with the pre-appointment stages of the appointments process, ‘...to encourage diversity in the range of persons available for selection for appointments.’ The 2005 reforms mark the first Parliamentary recognition of the goal of a more diverse judiciary. In the wake of the 2005 reforms there has been ongoing concern and debate about the slow progress being made towards a more diverse judiciary, particularly at the higher levels of the judiciary [3,4,5,6]. The separation of ‘merit’ from ‘diversity’ has attracted particular critical attention [7,8]. Judicial appointments to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom are one example of the slow progress being made. Of the 12 Justices that make up the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom only one is a woman. First appointed to the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords and then in 2009 to the new Supreme Court, Baroness Hale remains the only woman ever appointed to these two institutions, the UK’s highest courts. Lack of progress towards a more diverse judiciary in the Supreme Court is certainly not evidence of lack of opportunity to appoint more women. Since the court opened for business, in October 2009, eight of the 12 Justices of the Supreme Court have been replaced. While women have applied for at least some of these posts none of new appointees is a woman. None of the new appointees is from a black of visible ethnic minority background. None come from the solicitors’ branch of the profession. All are assumed to be heterosexual ([9], pp. 578–83). In response to concerns about the progress being made to achieve the goal of a more diverse judiciary more generally a series of reviews and research initiatives have been undertaken. Reporting in 2010, the Ministry of Justice’s Advisory Panel on judicial diversity concluded that a coherent and comprehensive strategy to promote diversity has been ‘lacking’ ([10], p. 4). A Judicial Diversity Task Force was set up in the wake of the advisory panel’s report to oversee the implementation of its recommendations. In the ‘Foreword’ to the 2013 report noted that while progress is being made, ‘the Taskforce recognises that there is no longer room for complacency...’ ([11], p. 5); more and some would suggest much more needs to be done [3,4,5,6,7,8]. In 2013 the Crime and Courts Act introduced further reforms to address some of the identified problems. One change, in schedule 13 part 2 of the Act, introduces a ‘tipping point’ provision. Where two applicants for a judicial post have satisfied the appointment on merit requirement and are found to be of equal merit the JAC may prefer one of them over the other for the purpose of increasing diversity within that group of judicial officers. Another reform, adding a new sub clause s. 137A to section 137 of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, creates a new duty on the Lord Chancellor, who is the government officer with overall responsibility for the justice system and the Lord Chief Justice, Head of the Judiciary to, “...take such steps as that office-holder considers appropriate for the purpose of encouraging judicial diversity.” These legislative changes and administrative initiatives are welcome. But problems remain. The one to be addressed in this paper relates to the different profiles of various strands of diversity. One of the findings that arose out of Advisory Panel’s discussions with stakeholder groups was, “There is a lot of focus on gender and ethnicity, but other strands such as disability and sexuality are not visible—all strands need to be considered.” ([10], p. 103). The focus of this essay is sexual diversity.

Sexual diversity is perceived to pose particular challenges [9]. An interview undertaken with a senior judge as part of an earlier project on sexual diversity in the judiciary [9] sheds some light on this. During the course of a discussion on the collection of data on sexual orientation from the judiciary the interviewee suggested a call for information would, “...go down like a lead balloon; probably worse amongst the men than the women...” ([12], p. 5). The judge speculated further that heterosexuals would find the question more problematic than non heterosexuals. The reason for the “lead balloon” response was explained in the following terms; the judiciary would regard the question as a reference to, “...part of their private life...” and the judge added, that “...raises all sorts of interesting questions about the extent to which the judiciary’s private lives are public property or should be.”([12], p. 5) Two closely related factors emerge from this response. The first is a neat distinction between the private and the public. The second is the association between sexual orientation and ‘private life’ rather than as an identity category. Together they work to put this strand of diversity in stark opposition to judicial office; sexual orientation is strictly extra judicial.3 The desire to secure this apparent private/public boundary is a related practical stumbling block, taking the form of governmental and judicial resistance, and at worst outright refusal, to call for and to respond to calls for information on sexual orientation.

One manifestation of the connection between sexual orientation and “private life” is the total lack of official data on the sexual composition of the judiciary. In 2006 the Lord Chancellor, Lord Chief Justice and the JAC Chairman issued a joint statement entitled, “Judicial Diversity: Measures of Success” [14]. It makes reference to four categories. One diversity category is professional status. The other three are gender, ethnic background and disability. The joint statement concludes:

...we will collect statistics for each level of the judiciary in relation to the ethnic origin, gender, disability status and professional background of:

This suggests the collection of diversity data, relating to all the key aspects and stages of the judicial appointments decision making process, is vital; for benchmarking purposes to monitor the effectiveness of operations and to map progress towards a more diverse judiciary. Sexual orientation is notable by its absence from this 2006 declaration. This has resulted in a total lack of official data on the sexual composition of the judiciary. The Ministry of Justice Advisory Panel stressed the importance of data:

We need to know what works, track progress and identify areas that may be lagging behind. The current problem is sometimes as fundamental as not collecting or publishing the data at all...([10], p. 21)

One of the data gaps singled out by the Advisory Panel was the total lack of information on sexual orientation ([10], p. 21).4

3. Barriers to Application for Judicial Appointment Research: LGBT Data

3.1. Introduction

The objective of the InterLaw Diversity Forum Barriers research initiative was to engage in a modest way with that ‘fundamental’ problem by using the JAC Barriers questionnaire to generate new data to fill the data gap produced by limits of the original JAC Barriers study. The goal was to add the ‘missing’ experiences and perceptions of the barriers to application for judicial appointment of members of the legal profession who identified as LGBT. The data was generated by means of a questionnaire using Survey Monkey.5 Details of the survey and how to access it were circulated via email though existing LGBT legal professional networks, including the InterLaw Diversity Forum, the Bar Lesbian and Gay Group (“BLAGG”) and the Lesbian and Gay Lawyers Association (“LAGLA”). To widen the pool of LGBT respondents outside of these groups information was circulated to all solicitors by The Law Society via their Professional Update newsletter. The Bar Council also circulated details of the survey through the Council’s Equality and Diversity Committee and via Chambers’ Equal Opportunities Officers. The questionnaire was electronically accessible for a two month period, from the beginning of December 2009 until the end of January 2010. The survey generated 188 responses.

3.2. A Demographic Snapshot ([15], Appendix)

Just under three-quarters of respondents (73%) indentified as gay men. Around a fifth of respondents (22%) identified as a gay woman or lesbian. The remaining respondents identified themselves as bisexual (3%) or other (2%). The demographic section of the questionnaire also included a question about gender identity. Although all respondents claim they were living the gender identity they were assigned at birth, one respondent self-identified as ‘transgender’ by way of the category ‘other’ when asked about sexual orientation.6 Seven percent reported being black Asian minority ethnic (BAME) respondents, 93% were white. Almost nine out of 10 respondents are ‘out’ at work. There was little variation between subgroups. The one exception to this is levels of sexual orientation self-disclosure by BAME LGB respondents. One in four BAME LGB respondents reported not being ‘out’ at work. The majority of respondents (76%) indicated that they were involved in an LGBT legal professional organisation. Half of those respondents (50%) indicated involvement in an LGBT employee network or employee resource group. Sixty-three per cent reported involvement in the InterLaw Diversity Forum.

Unlike the JAC Barriers study, no corrective weightings were used in the InterLaw Diversity Forum study to compensate for the over-representation of respondents from particular subgroups.

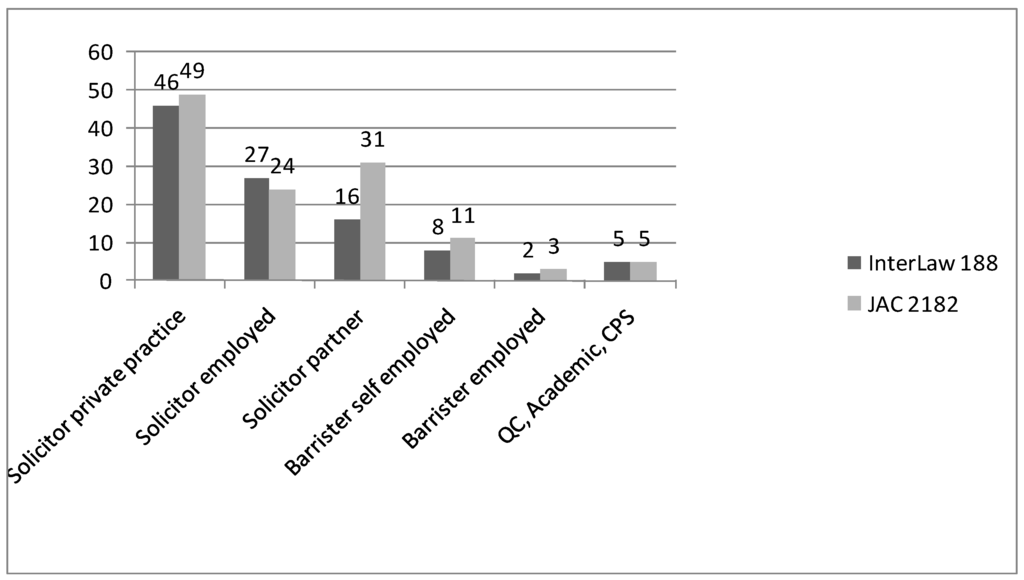

Figure 1 shows that both surveys have a preponderance of solicitor respondents, the majority of whom are in private practice (46% LGBT and 49% JAC). A similar percentage of solicitors in each group of respondents reported working outside private practice. Likewise the major of barristers in both groups are self employed. The greatest difference is in the percentage of respondents that report they are partners (16% LGB and 31% of respondents to the JAC Barriers study. One reason for this difference is the different age profile of respondents in the two studies. Table 1 below sets out the age profile of respondents to the two surveys.

Figure 1.

Professional background as a percentage of respondents to the two surveys.

Table 1.

Age of Respondents.

| InterLaw Diversity Forum Questionnaire JAC Questionnaire () | |

| 18–24 | 4% |

| (0%) | |

| 25–34 | 40% |

| (6%) | |

| 35–44 | 39% |

| (35%) | |

| 45–54 | 13% |

| (32%) | |

| 55–64 | 3% |

| (21%) | |

| 65+ | 1% |

| (1%) | |

Over 40% of respondents to the InterLaw diversity Forum survey are under 34 in contrast to 6% in the JAC study. This is a reflection of the fact that the JAC Barriers study targeted legal professionals over seven years qualified, the minimum legal qualification period for judicial appointment. As a result only a small number of respondents in that study were under 34 years of age. The differences in the professional career in the JAC study, 31% were partners in contrast to 16% of InterLaw respondents is likely to reflect the fact that 53% of JAC respondents were aged between 45 and 64. But it is also important to note, a majority of respondents to the InterLaw Diversity Forum survey (56%) were over the age of 35. A reason for the different age profiles is the InterLaw survey did not use a minimum qualification as a prerequisite for participation in the study. In part “minimum qualification” was not used because of a desire to maximise the opportunities to obtain LGBT data. Existing research on LGB legal professionals suggests that those who have been in the legal profession for the longest may experience a greater chilling effect making it less likely that they will be ‘out’ and thereby potentially more difficult to access [16,17]. Greater age diversity in the InterLaw sample also allowed data on perceptions to barriers to judicial careers to be obtained from a wider age range of respondents.

4. Key Findings

I now want to examine the data relating to three key aspects of LGB experiences and perceptions of barriers to judicial careers and the judicial appointments process. The first focuses on data relating to perceptions of judicial work and judicial office more generally. The second examines attitudes to a judicial career. The third focuses on perceptions of the selection process. What can this data tell us about the barriers that may be preventing applications to the judiciary by LGB people? What, if any are the differences between LGB subgroups? How does the LGB data compare with that found in the JAC Barriers research?

4.1. Perceptions of the Judiciary ([15], Chapter 4)

One of the factors influencing career pathways identified in the JAC study of barriers to judicial careers is overall perceptions of judicial office. Negative associations attached to judicial office are likely to work against the inclusion of the judiciary as a career option ([1], p. 25). To explore LGBT perceptions of judicial office the InterLaw Diversity Forum questionnaire closely followed the questions used in the JAC study. Using a number of statements such as, ‘judicial work would be enjoyable’ respondents were asked to identify characteristics of judicial office that were ‘appealing’ as well as ‘unappealing’. This is also an area of the questionnaire in which the InterLaw Diversity Forum study added some new questions. One sought to examine the significance of ‘a strong work place commitment to equality and diversity’ as an ‘appealing/unappealing’ aspect of judicial office. Another asked respondents to consider ‘hostility to gender and sexual diversity in the judicial workplace’ upon perceptions of judicial office.

Overall LGB perceptions of judicial office are very positive. Eighty-five per cent of LGB respondents indicated that judicial work would be enjoyable: see Table 2 below ([15], p. 6). This is a higher percentage than reported by respondents in the JAC Barriers Report (74%).

Table 2.

Judicial work would be enjoyable.

| % of ALL Respondents 153 LGB respondents (2,182 JAC respondents) | By Respondent Sub-groups | |||||||

| Gay Men (110) JAC Men | Gay Women/ Lesbians (33) JAC Women | White LGB (139) JAC White | BAME LGB (13) JAC BAME | LGB Solicitors (111) JAC Solicitors | LGB Barristers (14) JAC Barristers | LGB 7 Years PQ (84) JAC 7 Years PQ | ||

| Agree strongly | 44% | 46% | 33% | 45% | 39% | 39% | 72% | 49% |

| (32%) | (32%) | (33%) | (32%) | (34%) | (30%) | (42%) | (32%) | |

| Agree slightly | 41% | 44% | 39% | 43% | 23% | 43% | 21% | 38% |

| (42%) | (44%) | (40%) | (43%) | (42%) | (43%) | (40%) | (42%) | |

| Disagree slightly | 9% | 7% | 18% | 8% | 15% | 13% | 0% | 7% |

| (10%) | (9%) | (10%) | (10%) | (7%) | (10%) | (8%) | (10%) | |

| Disagree strongly | 1% | 1% | 0% | 1% | 7% | 2% | 0% | 1% |

| (4%) | (5%) | (3%) | (4%) | (4%) | (5%) | (4%) | (4%) | |

LGB respondents who were seven years post qualification and thereby eligible to be considered for judicial appointment also report a very positive attitude. The overwhelming majority of that group (87%) feel that judicial work would be enjoyable. Table 2 reveals some differences between LGB subgroups based on professional background. LGB barristers are more likely than solicitors to agree and to agree strongly that judicial work would be enjoyable. BAME LGB respondents are less likely to believe that judicial work would be enjoyable than white LGBT respondents (52% compared to 88%).

Over nine in 10 LGB respondents indicate that the interesting nature of the work undertaken by the judiciary is an appealing aspect of judicial office. As such it is the most commonly identified positive attribute of judicial office by LGB respondents. In this regard they do not differ from the respondents in the JAC Barriers Report research who also most frequency identified this aspect of judicial work as ‘appealing’. But the data represented in Figure 2 below indicates there is some evidence that LGB respondents differ in the characteristics and qualities of judicial office they find appealing.

Figure 2.

Aspects of Judicial Office that are appealing.

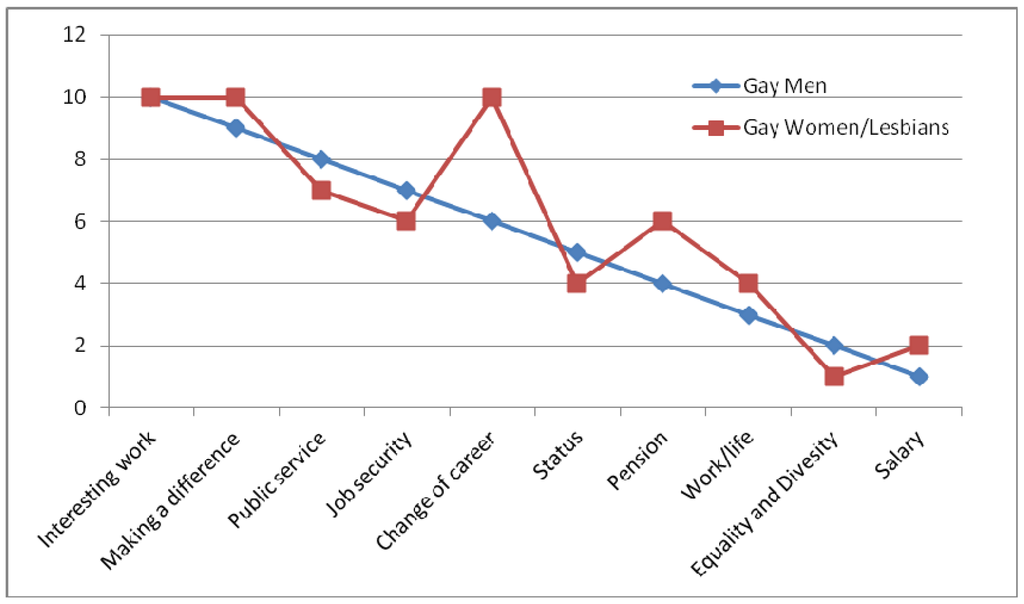

The data offers some evidence of differences between different LGB sub-groups. Figure 3 below is a comparison between the responses from gay men and gay women/lesbians.

Figure 3.

Gay men / Gay women, lesbians comparison.

For example more gay women/lesbians than gay men identify salary (82% compared to 59%), work/life balance (85% compared to 75%) and pension arrangements (89% compared to 77%) as aspects of judicial office that are appealing. All gay women/lesbians identify ‘change of career’ as an appealing dimension of judicial office (compared to 91% of gay men). The data and analysis presented in the JAC Barriers Report offers limited opportunity for comparison in this context but the author of that report also notes that there may be gender differences, noting that female respondents are more likely than male respondents to identify ‘making a difference to the law’ as being important ([1], p. 28). This is also reflected in the InterLaw Diversity Forum research data.

Two out of three LGB respondents (67%) indicate a strong workplace commitment to equality and diversity would be an appealing dimension of judicial office. Comparing the responses of gay men and gay women/lesbians suggests some differences between them on this matter. While both identify it as an appealing aspect of judicial office less frequently than other characteristics, there is also some evidence that gay women/lesbians may consider it less significant than gay men. There is no comparable data on this issue in the JAC Barriers study.

LGB respondents were also asked to select from a list of characteristics of judicial office those they found unappealing. Figure 4 ranks them in order of frequency of response and shows a comparison between InterLaw and JAC responses.

In common with the findings of the JAC study, aspects of judicial office relating to the general nature of the role of the judge are frequently identified as unappealing. For example almost two-thirds of LGB respondents (63%) identify the isolated nature of the role of judge as unappealing. This is similar to the response rate in the JAC study (66%). But there are also differences with regard to responses to these characteristics of judicial office. LGB respondents are less likely than JAC respondents to identify loss of flexibility as unappealing (44% compared to 58%).

Figure 4.

Which aspects of judicial office are unappealing.

One point of difference between the two groups of respondents relates to judicial establishment and culture. LGB respondents more frequently identified this as an unappealing aspect judicial office in comparison to JAC respondents. It ranked second amongst LGB respondents and 4th by the JAC respondents. There is also some divergence between LGB subgroups on this matter. Gay women/lesbians and BAME respondents are the two subgroups most likely to report ‘judicial establishment and culture’ as unappealing. More LGB solicitors (50%) than barristers (29%) indicate that it is unappealing. This echoes the findings in the JAC Barriers Report which notes that women and BAME respondents are also most likely to find judicial establishment and culture an unappealing aspect of judicial office. BAME JAC respondents also rank this higher than other respondents ([1], p. 30).

The responses from gay women/lesbians also suggest that different women may have different perceptions of the unappealing aspects of judicial office. For example more gay women/lesbians than women respondents to the JAC survey identify judicial culture as unappealing (71% compared to 54%).

The data also suggests a number of other differences. For example gay women/lesbians and BAME are the two LGB subgroups most likely to say that increased workload is an unappealing aspect of judicial office. BAME LGBT respondents and LGBT barristers were more likely to identify ‘reduction of earnings’ as one of the most unappealing aspects. BAME respondents are more likely to identify potential gender/sexual hostility as unappealing. Gay women /lesbians are the subgroup most likely to say increased workload is unappealing.

4.2. Attitudes to a Judicial Career([15], Chapters 4 and 6)

The JAC Barriers Report argues that whether a respondent sees being a judge as part of a career path is one of the key determining factors informing future application behaviour ([1], p. 32). Is judicial office a career option LGBT respondents have in mind?

More LGB respondents than JAC respondents (33% compared to 28%) indicate that they see a judicial office as part of their career path. Seven years post-qualified LGBT respondents are more likely than the general sample of LGBT respondents to see the judiciary as a part of their career path (40% compared to 33%). Gender seems to play a significant role in LGBT responses. Gay women/lesbians are much less likely to see judicial office as part of their career path than gay men (17% compared to 36%).

Respondents were asked whether they had ever applied for judicial office and those that had not applied were asked whether they had ever considered it. The results and a comparison with the JAC data are set out in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Whether ever applied for judicial office.

| % of ALL Respondents 154 LGB respondents (2,182 JAC respondents) | By Respondent Subgroups | |||||||

| Gay Men (112) JAC Men | Gay Women/ Lesbians (32) JAC Women | White LGB (140) JAC White | BAME LGB (13) JAC BAME | LGB Solicitors (112) JAC Solicitors | LGB Barristers (14) JAC Barristers | LGB 7 YEARS PQ (86) JAC 7 Years PQ | ||

| Yes—has applied | 16% | 15% | 12% | 16% | 15% | 13% | 21% | 28% |

| (17%) | (18%) | (14%) | (17%) | (11%) | (13%) | (35%) | (17%) | |

| No—has considered | 28% | 28% | 28% | 28% | 31% | 31% | 28% | 24% |

| (32%) | (33%) | (31%) | (31%) | (40%) | (31%) | (33%) | (32%) | |

| No—has not considered | 55% | 57% | 53% | 56% | 46% | 54% | 43% | 48% |

| (49%) | (48%) | (52%) | (50%) | (47%) | (53%) | (30%) | (49%) | |

A similar percentage of LGB respondents (44%) than JAC respondents (49%) have either applied or considered application for judicial appointment. When the LGB sample is confined to those who had the necessary seven years post-qualified experience, LGB respondents report higher rates (52% compared to 49%). LGB barrister respondents are much less likely than JAC barrister respondents to have applied in the past (21% compared to 35%). LGB barrister respondents are far more likely than LGB solicitor respondents to have applied for judicial office (21% compared to 13%).

The JAC Barriers Report found that white respondents are more likely to have applied in the past than BAME respondents ([1], p. 19). This is not the case in the data from the InterLaw Diversity Forum Report. There is little evidence that ethnicity makes a difference for LGB respondents when it comes to those who have applied or would consider making an application. White LGB respondents are, however, more likely than BAME respondents to have not considered application (57% compared to 46%).

The JAC Barriers Report concludes that there is evidence that gender appears to be a factor influencing judicial career decisions ([1], p. 19). There is some evidence in support of this in the context of LGB respondents. Gay men are more likely to have actually applied compared to gay women/lesbians (15% compared to 12%). Lesbians indicate the lowest level of past application for judicial office of any LGB subgroup.

However, it remains the case that a minority of applicants in both studies have applied for judicial office. In response to a statement about intention to apply for judicial office, the majority of both sets of respondents indicated that they were not likely to apply for judicial office: 61% LGB and 60% JAC respondents. So in both studies the majority are not likely to have included a judicial appointment on their career pathway. What does InterLaw Diversity Forum’s study reveal about the reasons for this? Do the reasons given by LGBT respondents differ from those reported in the JAC study?

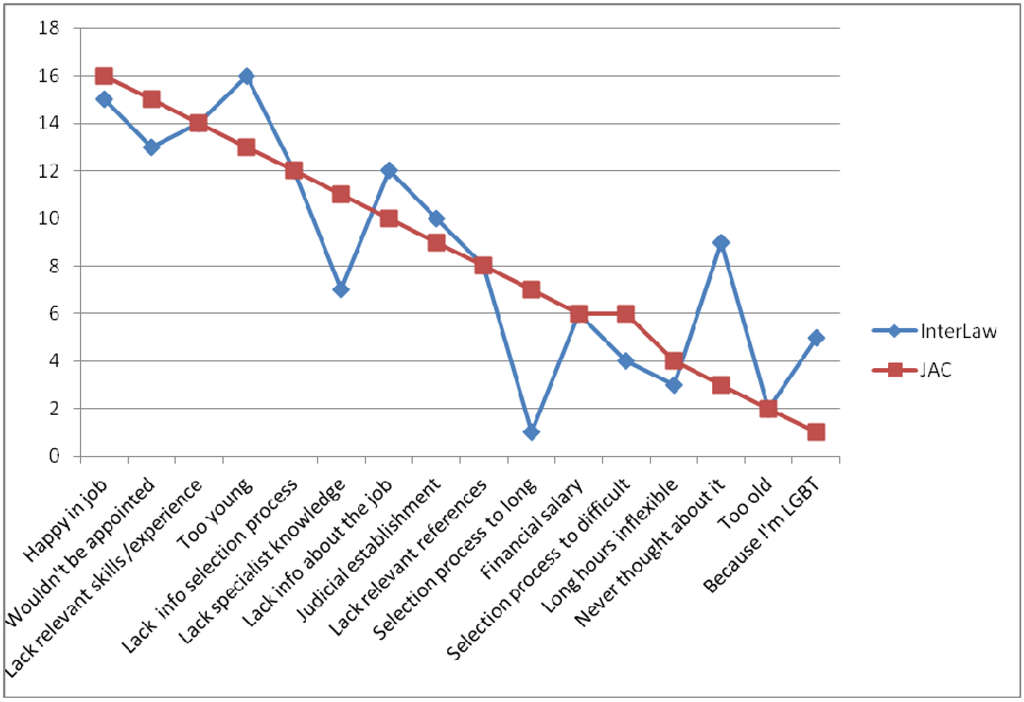

In both studies those who had never applied for judicial office were asked to give their response to a range of ‘reasons’ for this. The InterLaw Diversity Forum list contained an additional “reason”, “because I am LGB”. Figure 5 (below) shows the distribution of responses and provides a comparison of LGB and JAC data.

Figure 5.

Reasons for never applying.

The most frequently given reason for not having applied for judicial office by LGB respondents is that respondents are too young (56%). This differs from the most frequent reason given by respondents to the JAC questionnaire, where “happy in their current job” is the most frequent explanation (51%). As noted above, the age composition of the two samples is different with a larger percentage of LGB respondents under 35 years of age.

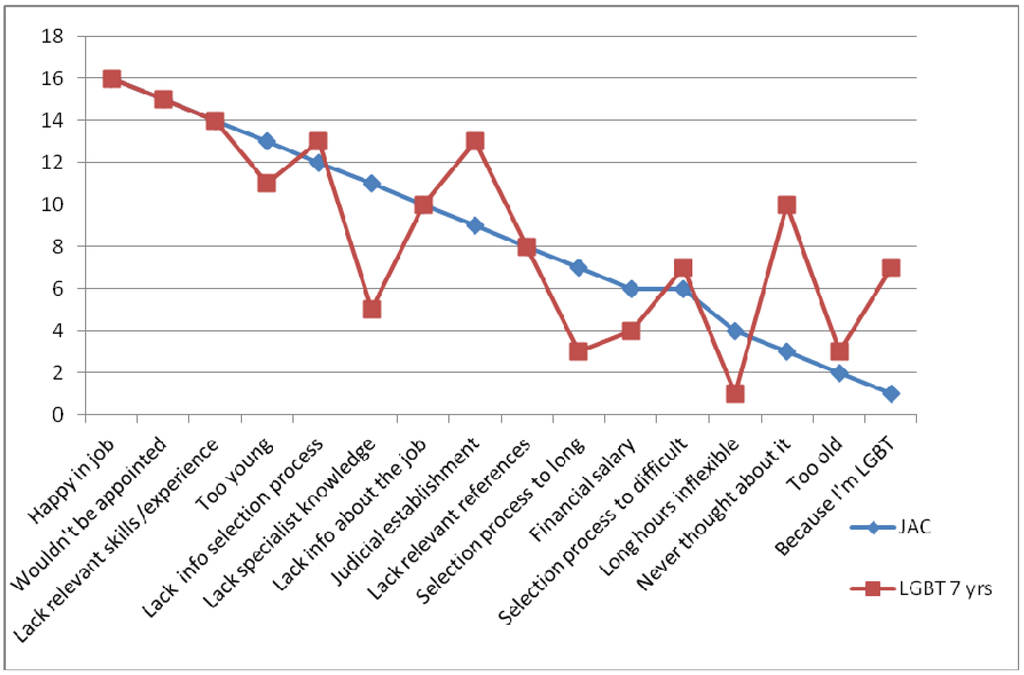

When the LGB sample is limited to seven years post-qualified respondents, see Figure 6 below, the main reasons given for not considering an application are the same as those given by JAC respondents “Happy in current job”, “Don’t think I would be appointed” and “Don’t have the relevant skills/experience”.

Figure 6.

Reasons for never applying JAC/InterLaw 7 yr P Q.

LGB seven years post-qualified respondents are more likely than JAC respondents to identify “judicial establishment and culture” as a reason why they have never applied (29% compared to 17%). This is reproduced when the LGB respondents as a whole are compared with JAC respondents (25% compared to 17%). LGB seven years post-qualified respondents are also more likely to identify ‘judicial establishment’ and ‘Because I am LGB’ as reasons for not considering a judicial career, than LGB respondents as a whole. Seven years post-qualified respondents and gay women/lesbians7 were the LGB subgroups most likely to identify the difficulties of the selection process as a reason why they never applied.

A higher proportion of LGB respondents than JAC respondents have not applied because they do not think they have relevant skills or experience (48% compared to 38%). The JAC Barriers Report data indicate that women (44%) are more likely than men (34%) to say that they have not applied because they do not have the relevant skills ([1], p. 21). This is not reproduced in the InterLaw Diversity Forum data gay men and gay women/lesbians gave equal significance to this (50%).

Being LGB is given as a reason for not applying by 11% of the InterLaw survey respondents.

Data from the InterLaw Diversity Forum Report did show a number of differences between LGBT sub groups. A higher proportion of BAME LGB respondents (46%) in contrast to white LGB respondents (23%) report that they have never considered judicial office. BAME LGB respondents (55%) were the subgroup most likely to indicate ‘judicial culture’ as a reason why they had never applied for judicial office. BAME LGB (18%) and gay women/lesbians (15%) were the subgroups most likely to give being LGB as a reason why they never applied for judicial office. Lesbians are more likely than gay men to cite long hours and inflexibility as a reason for non-application (12% compared to 1%). Gay men are more likely than gay women/lesbians to give judicial establishment and culture as a reason why they have never applied (30% compared to 15%).

Respondents were asked about their perceptions of support available in their practice or set of chambers if an application for judicial office was made. A smaller number of LGB respondents (40%) than JAC respondents (51%) indicate a belief that their practice or chambers would support their application for judicial office. This remains true even when questioning only seven years post-qualified LGB respondents. LGB barristers (75%) are by far the most likely to report feeling they would be supported in their application by their place of work (compared to 38% of LGB solicitors). This mirrors findings in the JAC Barriers Report. The difference between gay women/lesbians and gay men is much greater (3% compared to 39%) than that found in the JAC Barriers Report (47% women compared to 54% men). BAME LGB respondents (46%) are more likely to feel they would be supported in their workplace than white LGB respondents (33%). This also mirrors responses in the JAC Barriers Report data.

Another factor that may influence reasoning about judicial careers was presented to those undertaking the questionnaire by way of the statement, ‘a judicial career is not for people like me’. Figure 7 below represents the responses.

Figure 7.

A judicial career is not for people like me.

The InterLaw Diversity Forum Report data suggests there is some similarity between the number of LGBT and JAC respondents who agreed with the statement, ‘a judicial career was not for people like me’ (38% compared to 33%). This picture differs when considering responses from LGB people with seven year’s post qualification experience. They were more likely than JAC respondents to indicate that a judicial career is not for people like me; 41% compared to 33%.

LGB solicitors are more likely than LGB barristers (41% compared to 21%) to ‘agree’ that a judicial career is not for people like them. There is less difference between LGB solicitors and barristers and JAC respondent solicitors and barristers.

This picture begins to change when you examine the LGB respondents by way of gender. The JAC Barriers Report finding that ‘[W]omen were also more likely than men to feel that a judicial career is not for people like them (36% compared to 29%)’ ([1], p. 31) is not reproduced in the InterLaw Diversity Forum Report data. Gay women/lesbians are like gay men in their response. Both groups indicate a similar level (36% compared to 39%) of agreement with the statement, ‘a judicial career is not for people like me’. BAME LGB respondents are much more likely to indicate that ‘a judicial career is not for me’ than BAME JAC respondents (54% compared to 28%).

In a related question respondents were asked to evaluate the statement ‘It’s more difficult for certain types of people to apply successfully for judicial office’. The InterLaw Diversity Forum Report data suggests there is some similarity between the number of LGB and JAC respondents who agreed with the statement (75% compared to 72%). LGB BAME and gay women/lesbians are exceptions to this. Both are more likely to agree with the statement than BAME and women respondents to the JAC survey; LGB BAME 92% in contrast to JAC BAME 78% and Gay women/lesbians 86% compared to 73% JAC women).

4.3. The Appointments Process ([15], Chapters 7–9)

In this section I want to focus on some of the data relating to perceptions of the appointments process and more specifically to perceptions of the fairness of the selection process. To begin with a positive note, the InterLaw Diversity Forum survey identified considerable LGB support for the establishment of the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC). LGB respondents were more likely than JAC Barriers respondents to identify the creation of this appointment’s mechanism as a positive development (86% in comparison to 75%). Gay women/lesbians are more likely than gay men to consider it a positive initiative (90% compared to 85%). BAME LGB respondents have more polarised opinions. They are least likely to consider it positive and the subgroup most likely to indicate ‘don’t know’. BAME LGB respondents are also more likely to indicate it is not a positive development than white LGB respondents (9% compared to 2%).

The survey included a number of questions designed to examine perceptions of the fairness of the selection and appointment process. LGB respondents are less likely to believe that the selection process is fair than JAC respondents. Gay women/lesbian and BAME LGB respondents are most likely to disagree with the statement, ‘the selection process is fair’. The JAC Barriers Report also finds that BAME respondents are most likely to not feel that the process is fair ([1], p. 58). BAME LGB respondents and LGB barristers have the strongest opinions on the fairness of the process, with small percentages of respondents indicating they ‘don’t know’ (7% and 2%, respectively).

An important aspect of the fairness of the judicial appointments process introduced in the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 is the obligation to appoint the judiciary on the basis of merit. Merit is in law the sole basis for judicial selection and appointment. The response to the statement ‘I believe judges are selected on the basis of merit only’ set out in Table 4 below, offers an opportunity to explore LGB perceptions of the success or otherwise of this statutory basis for judicial appointment.

Table 4.

I believe judges are selected on the basis of merit only.

| % of ALL Respondents 167 LGB respondents (2182 JAC respondents) | By Respondent Sub-groups | |||||||

| Gay Men (121) JAC Men | Gay Women/ Lesbians (36) JAC Women | White LGB (153) JAC White | BAME LGB (13) JAC BAME | LGB Solicitors (124) JAC Solicitors | LGB Barristers (14) JAC Barristers | LGB 7 Years PQ (92) JAC 7 Years PQ | ||

| Agree strongly | 12% | 14% | 0% | 12% | 8% | 14% | 7% | 14% |

| (20%) | (22%) | (16%) | (20%) | (23%) | (19%) | (24%) | (20%) | |

| Agree slightly | 29% | 34% | 13% | 31% | 8% | 24% | 43% | 31% |

| (31%) | (33%) | (28%) | (32%) | (21%) | (31%) | (33%) | (31%) | |

| Disagree slightly | 31% | 26% | 50% | 32% | 17% | 33% | 36% | 32% |

| (25%) | (24%) | (28%) | (25%) | (26%) | (25%) | (24%) | (25%) | |

| Disagree strongly | 24% | 22% | 31% | 21% | 58% | 27% | 7% | 20% |

| (12%) | (11%) | (13%) | (11%) | (18%) | (12%) | (12%) | (12%) | |

| Don’t know | 4% | 4% | 6% | 4% | 8% | 3% | 7% | 3% |

| (12%) | (10%) | (15%) | (12%) | (10%) | (13%) | (7%) | (12%) | |

Over half of the InterLaw Diversity Forum respondents (55%) do not believe judges are selected on the basis of merit only. This is a larger percentage than in the JAC Barriers Report, which reported that 37% do not believe this but 51% do indeed believe judges are appointed on merit. A much smaller percentage of LGB respondents than JAC respondents ‘don’t know’—4% compared to 12%. LGB seven years post-qualification were more likely to disagree with the statement that ‘judges are selected on the basis of merit only’ than JAC respondents (52% compared with 37%).

A number of findings in the InterLaw Diversity Forum Report mirror those in the JAC Barriers Report. LGB barristers are more likely than LGB solicitors to believe that selection is purely merit based (50% compared to 38%). Gay men (48%) are more likely than gay women/lesbians (13%) to believe that selection is purely merit based. Ethnicity also generated differences. White LGBTs (43%) are more likely than BAME LGBs (16%) to believe judicial appointment is made purely on merit.

Respondents were asked about a number of statements designed to explore their perceptions of a range of other factors influencing appointment. A larger percentage of LGB respondents than JAC respondents (70% compared to 55%) indicate that they believe that there is prejudice in the selection process. A smaller number of LGB respondents than JAC respondents (14% compared to 22%) do not feel that there is prejudice within the selection process, and a smaller number of LGB respondents say they ‘don’t know’ (17% compared to 23%) LGB barristers are the subgroup most likely to express uncertainty about their belief (29% compared to 14% solicitors). Gay women/lesbian respondents (100%) are most likely to feel that there is prejudice in the process of appointment and most likely to feel strongly about this. BAME LGB respondents (85%) similarly believe that prejudice plays an important role in the judicial appointments process.

The JAC Barriers Report notes that in the past judicial appointment was associated with the operation of an ‘old boys’ network’; that ‘it’s not what you know but who you know’ that counted ([1], p. 63). That study included a statement to test current beliefs on this point and the InterLaw Diversity Forum questionnaire followed in its footsteps. More than four out of five (84%) LGB respondents feel that networking is important if you want to be successful in an application for judicial office. This is higher than in the JAC Barriers Report (69%). LGB respondents are also more likely to strongly agree that networking is needed (47% in comparison to 28%). LGB respondents who have the necessary seven years post-qualified experience are also more likely than JAC respondents to feel strongly that you need to network to apply successfully for judicial office (44% in comparison to 28%).

The JAC Barriers Report finds that gender and ethnicity produce major differences in believing whether one needs to network for successful judicial appointment ([1], p. 64). The InterLaw Diversity Forum Report data offers more evidence in support of this conclusion. Gay women/lesbians are the subgroup most likely to agree (and to strongly agree 68%) that you need to network for successful judicial appointment. In the InterLaw Diversity Forum Report data BAME LGB respondents are most likely to express strong agreement with the statement that networking is important (69%).

LGB barristers are less likely to agree that you need to network than LGB solicitors (79% compared to 87%). This echoes the findings in the JAC Barriers Report ([1], p. 63).

Related to the idea of networking as a powerful factor influencing appointment is the role of references and the weight attached to them. Both questionnaires included the following statement: ‘too much weight is placed on references in the selection process’. One of the findings of the JAC Barriers Report is that there is a high number of respondents who are unable to respond to this statement—half of those taking part in the survey (51%) ([1], p. 65). A smaller number of LGB respondents are unable to answer the question (43%). A larger number of LGB respondents than JAC respondents agree with the statement that too much weight is placed on references (42% compared to 31%). Gay men and white LGB respondents are least able to respond to the statement.

In the JAC Barriers Report one of the ’key barriers to application’ was the perception—and what they describe as the ‘misperceptions’—of the judicial establishment and culture amongst potential candidates ([1], p. 69). In an effort to generate new comparable information about LGBT perceptions and ‘misperceptions’ of influences on success the InterLaw Diversity Forum Report questionnaire also included questions asking respondents to rate a number of factors on the basis of whether they thought they were positive or negative influences on the successful outcome of an application for judicial office. In addition to the work-related and biographical factors included in the JAC questionnaire, the InterLaw Diversity Forum questionnaire asked respondents whether they thought “being LGBT”, “being out at work” and “being involved in LGBT organisations’ would have a positive or negative influence on the successful outcome of an application for judicial office. The results are set out in Table 5 below.

The table, following the approach adopted in the JAC Barriers Report, organises the responses into four groups depending on how positive or negative the respondents are ([1], pp. 69–70). The scores are based on a simple calculation, subtracting the proportion of those who rated the factor as a negative influence from the proportion who rated the factor as a positive influence. Each factor is then allocated a score out of 100 to show its relative influence. The higher the score the more likely it is to be seen as a positive influence on successful application to judicial office. The authors of the JAC Barriers Report note that although rudimentary, the scoring offers a clear view of underlying preconceptions of the judiciary and the selection process.

Table 5.

Which factors positively or negatively influence outcome.

| Strong positive influence | Positive influence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| InterLaw Diversity Forum Questionnaire | JAC Questionnaire | InterLaw Diversity Forum Questionnaire | JAC Questionnaire |

| -being a barrister (+96) -known to senior judiciary (+95) -having High Court experience (+94) -in the right social networks (+92) -right educational background (+92) | -known to senior -judiciary (+89) -having High Court -experience (+87) -being a barrister (+87) -right educational -background (+79) | -middle/upper class (+67) -41-50 (+53) -over 50 (+50) - male (+47) -in private practice (+36) -a specialist (+36) | -in 40’s (+56) -in private practice (+49) middle/upper class (+38) -a specialist (+34) -over 50 (+27) -male (+27) -BAME group (+21) |

| Neutral | Negative influence | ||

| InterLaw Diversity Forum Questionnaire | JAC Questionnaire | InterLaw Diversity Forum Questionnaire | JAC Questionnaire |

| -being from an minority -ethnic group (-5) | -being a solicitor (+12) -having a disability (+2) -female (+1) | -under 40 (-59) -working class (-56) -being LGBT (-52) -being out at work (-50) -in an LGBT network (-38) -a solicitor (-24) -a disability (-23) -female (-20) | -aged under 40 (-43) -working class (-25) |

There is considerable similarity between the pattern of LGB responses and the responses of those in the JAC Barriers Report. Perceptions and ‘misperceptions’ of the factors which have the most positive and most negative influences appear to be similar. So there is a strong perception amongst both LGB and JAC respondents that achieving a judicial appointment is dependent upon professional background and contacts: being a barrister with experience, contacts in the higher courts, a particular educational background (i.e., Oxbridge educated). Being male, middle-aged and middle class are also positive factors. In short respondents to both surveys continue to perceive the judiciary as being made up of professional and social elites.

There is also much consensus on negative influences. For example, LGB respondents consider being female and being disabled as having negative influences, but even more so than JAC respondents do.

There are other parallels between LGB responses and those identified in the JAC Barriers Report. LGB solicitors and gay women/lesbians are more likely than LGBT barristers and gay men to believe that having the right educational background exerts a strong influence on a successful application. LGB barristers are the least likely to indicate that the right educational background has a strong positive influence.

Being male is seen as a positive factor by more LGB respondents than JAC respondents. Gay women/lesbians indicate that they consider being male to have a strong positive influence. This echoes the finding in the JAC Barriers Report whereby being a man is overwhelmingly seen as a positive influence by women. Being middle or upper class is overwhelmingly seen as a positive influence by more gay women/lesbians than gay men.

LGB respondents only identify one factor as neutral: being from a minority ethnic background. One subgroup, LGB barristers identify it as a positive influence. LGBT barristers and gay men are the subgroups who identify ‘being female’ as a neutral factor.

There is some overlap between LGB respondents and JAC respondents in relation to negative factors. All agree that a “working class background” and “being under 40” have a negative influence on whether an application has a successful outcome. LGB respondents identify a wider range of factors having a negative influence than JAC respondents. Being female, being disabled and being a solicitor are all perceived to be negative factors by LGB respondents. JAC respondents categorised them as “neutral”. Gay women/lesbians and BAME LGB respondents are the demographic groups most likely to associate negative effects with categories of difference. For example, both subgroups identify ‘being from a minority group’ as a negative influence. Both are also more likely than other subgroups to identify ‘being female’ as a negative influence.

Finally, the responses to the statements relating to sexual orientation produced interesting results. Being LGBT, being out at work and being a member of an LGBT network are considered to be factors with negative effects on the judicial selection process. Lesbians and BAME LGB respondents are most likely to consider them negative factors. All LGB subgroups consider being a member of a group such as The InterLaw Diversity Forum to be a negative influence on the outcome of an application for judicial office. LGB barristers and BAME respondents are the least likely to indicate that it would have a negative influence.

5. Commentary

The InterLaw Diversity Forum Barriers project was a first step in a much longer process of adding experiences and perceptions of judicial office and the judicial appointments that have been missing from or lay silent within existing data and research. It is important to acknowledge that these were hesitant and in some respects flawed, first steps; the data must be treated with some caution. The number of respondents that participated in the LGBT survey is relatively small. When broken down into a variety of subgroups within that general population some of these groups are made up of little more than a handful of people. The project failed to connect with legal professionals who identify as transgender. Clearly these limits suggest more research on the LGBT legal professional population as a whole and subsets within that diverse ‘group’ is needed. However, to dismiss or ignore the data generated by the InterLaw Diversity Forum Barriers project on that basis would be to return to and reinforce existing silences and exclusions and would be to miss an opportunity to examine, albeit with some caution the new data that has been produced and to reflect on the issues emerging in that data. With these points in mind I want to add a number of reflections on the InterLaw Diversity Forum data and its fit with the data and analysis that makes up the JAC Barriers report.

There is evidence here of similarities between the experiences and expectations of InterLaw Diversity Forum respondents and JAC respondents across a range of matters. With regard to perceptions of judicial office, both share a largely positive view of that institutional position and have in common a perception that judicial work is enjoyable, interesting work. Perhaps more surprisingly a similar number of respondents to both questionnaires indicate that they have applied in the past or would consider applying in the future for judicial office. Similarities continue in relation to reasons given for not considering an application for judicial office. Both groups indicate that current job satisfaction, uncertainty of appointment and lack of skills and experience are the most frequently identified reasons for not considering judicial office. LGB perceptions of the key barriers to application are also similar to those listed the JAC Barriers Report. ‘Being a barrister’, ‘knowing senior members of the judiciary’, ‘being involved in the right social networks’, ‘having the right educational background’ and ‘prior experience before higher judges’ are all strongly associated with judicial careers by both groups of respondents. In short both groups of respondents continue to perceive the judiciary as a group made up of professional and social elites.

One of the factors linking LGB experiences and perceptions to those groups that populated the JAC study is the impact of legal professional background. For example, LGB barristers are more likely than LGB solicitors to have a judicial career in mind, just as is the case with barristers from the JAC respondents. LGB barristers are by far the most likely (75%) to feel they would be supported in their application by their place of work, while only 38% of LGB solicitors feel that this would be the case. Again, this mirrors the findings in the JAC Barriers Report ([1], p. 34).

There is also evidence that gender may bring the experiences of those who self identify as LGB close to those who are presumed to be heterosexual. Some of the gender differences noted in the JAC Barriers Report are mirrored in the different experiences reported by gay women/lesbians and gay men. For example both InterLaw Diversity Forum female respondents and women responding to the JAC Barriers survey are more likely than male respondents (gay or presumed straight) to identify ‘making a difference’ as an important positive aspect of judicial office.

But it is far from the case that LGB experiences and perceptions are the same as those in the groups investigated by through the JAC Barriers survey. There is some evidence that suggests sexual orientation may well be factor generating differences. In some respects these differences may potentially bode well for the future progress of judicial diversity. For example LGB respondents are more positive in their perception of judicial office. There is also some indication that LGB respondents are more positive about judicial careers, being more likely than JAC respondents to consider judicial office as a possible career option.

But at the same time the attractions of judicial office may differ between L, G, and B and heterosexual legal professionals. ‘Making a difference’ scores higher among LGB respondents than among JAC respondents. LGB respondents identify ‘status and prestige’ more frequently than JAC respondents as an appealing dimension of judicial office.

At the same time the attractions of judicial office coincide with the chilling effect of LGB perceptions and expectations relating to barriers to appointment. When comparing seven years post-qualified InterLaw Diversity Forum respondents with seven year’s post-qualified JAC respondents, LGB respondents (40%) are more likely to indicate that a judicial career is not for them than the JAC respondents (33%). One difference between LGB and JAC respondents relates to the judicial workplace as a hostile environment. Seven years post-qualified LGB respondents are more likely than seven years post-qualified JAC respondents to identify ‘judicial culture’ as a reason why they never applied for judicial office (29% compared to 17%).

LGB respondents indentify a wider range of factors as negative influences on judicial career aspirations. Not only is being ‘lesbian, gay or ‘bisexual’ rated by LGB respondents as a negative influence on the outcome of an application but ‘being female’, ‘being disabled’ and ‘being a solicitor’ are also perceived as negatives, while JAC respondents view gender, disability and legal professional background as neutral factors. Does this suggest that the chilling effect of structures of discrimination are more keenly felt and acted on by LGB legal professionals than by JAC respondents? It is certainly one issue that calls for further research.

In some cases, sexual orientation may create bonds that seem to diminish the effects of other differences, such as gender, race and ethnicity. The JAC Barriers Report finding that ‘[W]omen were also more likely than men to feel that a judicial career is not for people like them (38% compared to 30%)’ ([1], p. 31) is not reproduced in the InterLaw Diversity Forum Report. Among LGB respondents, women’s responses tend to correspond more with men’s than in the JAC Barriers Report. For example both gay women/lesbians and gay men indicate a similar level (33% compared to 34%) of agreement with the statement: ‘A judicial career is not for people like me’.

At the same time there is evidence of the opposite effect; gender and ethnicity in combination with sexual orientation may have an amplifying effect, making elite positions seem more entrenched and the barriers to change even higher. For example, gay women/lesbians and BAME LGB respondents are the subgroups most likely to associate negative effects with being members of various strands of diversity. Both subgroups identify ‘being from a minority group’ as a negative influence and are also more likely than other subgroups to identify “being female” as a negative influence. Gay women/lesbians and BAME LGB respondents are the two subgroups most likely to indicate “judicial establishment and culture” as an unappealing aspect of judicial office. Among LGB respondents, gay women/lesbians are less likely than gay men to indicate they will apply in the future. The JAC Barriers Report finds no differences between male and female respondents in this regard. BAME LGB respondents are much more likely to indicate that ‘a judicial career is not for me’ than BAME JAC respondents (54% compared to 28%). BAME LGB respondents are also less likely to indicate they will apply in the future. This is contrary to findings in the JAC Barriers Report where BAME respondents indicate they are more likely to apply in the future.

The data that sexual orientation may shape understanding of the qualities and nature of judicial office or assumptions and expectations attached to selection and appointments processes takes us back to the question of the relationship between sexual orientation and judicial office. These perceptions go against the grain of the argument that sexual orientation is a private matter and thereby hermetically sealed from the public institution of judicial office. Seven out of 10 LGB respondents indicate that more open LGB members of the judiciary would make them more likely to apply for judicial office. Two in three indicate that a stronger public commitment to equality and diversity by the judiciary and JAC would make them more likely to apply. These are not calls to bring what has been perceived by many to have been previously strictly extra-judicial into the institution of the judiciary [15] but in part an appreciation of the heterosexual status quo [9] and a call to change to adapt the sexual politics of that institution to give due recognition to sexual diversity.

6. Two Steps Forward and Two Steps Back; the Story Continues

Subsequent to the publication of the InterLaw Diversity Forum Barriers report the JAC announced that from July 2011 the JAC would monitor the sexual orientation of candidates for judicial appointment [18]. Subsequent to that the JAC commissioned further research to “update and refresh” ([19], p. i) the data on barriers to application for judicial appointment. Sexuality was added to the demographic categories. Having regard to the absence of sexual orientation and LGBT as “key groups” in the original survey the addition of sexuality in the second survey is not so much an ‘update and refresh’ exercise but more a new departure. Both of these JAC initiatives were important changes in the JAC’s approach to taking sexual orientation as a strand of diversity more seriously. As such they are both welcome developments.

In general the findings from the JAC “update and refresh” research, the Barriers to application to judicial appointment 2013 (Barriers 2013) report [19] provide more support for the findings first reported by the InterLaw study. This suggests little has changed in the albeit short period between the InterLaw and Barriers 2013 study. For example the 2013 JAC study reports that compared to “straight or heterosexual” ([19], p. 8) respondents, it remains the case that “LGBT respondents” are less likely to believe judges are selected on the basis of merit only ([19], pp. 8, 65). They are likely to not apply because of a belief that their sexual orientation will affect chance of being selected ([19], p. 8). They are more likely to believe that being from a BAME background, having a disability, being “LGBT” or a working class background has a negative impact on likelihood of successful application ([19], pp. 8, 79). On a more positive note “LGBT respondents” are more likely to go to the JAC for information. The data also suggests that more information on equality/diversity policies, more diverse role models and more openly LGBT members of the judiciary will have a positive effect making LGBT legal professionals more likely to apply for judicial office ([19], p. 9). Last but not least statements from the JAC about their commitment to equality and diversity will encourage applications ([19], p. 9).

The inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity is to be welcome. However, there are ongoing concerns. One problem is the way the research was undertaken. The sample size for the new study was 4,051 members of the legal profession with the minimum judicial appointment qualification of five years of legal practice experience. Black Asian Minority Ethnic legal professionals were oversampled ([19], Appendix B). The rationale being that they were a group “of particular interest” ([19], p. i). Despite the fact that this was the first time “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” had been introduced as a diversity category in JAC research and the first time that efforts had been made by the Judicial Appointments Commission to gather information about lesbian and gay perceptions of barriers to application, it is surprising and disappointing that LGBT did not attract the status of groups ‘of particular interest’. No explanation is offered for the decision not to afford that group some priority in the 2013 initiative.

More surprising is the fact that the 2013 report contains no clear statement about the size and composition of the “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” survey respondents. Appendix B, which outlines the methodology gives details of the numbers of questionnaires dispatched and returned and analyses this information. It includes the number of respondents categorised by professional background, gender, race and ethnicity and age. Breakdowns on the basis of “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” are missing. Appendix C contains the demographic data. The total numbers of men and women, white and black and minority respondents is provided. The same is the case for professional background. Disability, religion and sexuality and gender identity are treated differently. They are only ever referred to as categories within other distinctions. So sexuality is presented only as a percentage of solicitors, barristers, legal executive. As a result it is difficult to establish the numbers within the sample population as a whole that identified as heterosexual, lesbian, gay male, female bisexual, male bisexual, and transgender. These figures are missing, hidden. Again no explanation is given for treating some strands of diversity differently than others.

At best, the LGBT input is just over 200 respondents. This is approximately 5% of the sample. As a result of over-sampling black and minority ethnic respondents make up 16% of the sample. The failure to apply a similar strategy with regard to sexuality is unexplained in the report. The failure to oversample by reference to LGBT in this study is a missed opportunity.

Beyond the second Barriers study there are other signs suggesting that at worst there is a stubborn resistance to taking sexual diversity of the judiciary seriously and at best change is slow. For example while the JAC has been collecting data on the sexual diversity of applicants for judicial appointment since 2011 [18] there continues to be no published data available on the sexual composition of the pool of potential applicants or the sexual composition of those who apply and are eventually appointed. In a report published in December 2013 containing statistical data on Judicial Selection and Recommendations for Appointment for the period April 2013 to September 2013 [20] the data is analysed by way of gender, race and ethnicity, disability, age and professional background. Demographic data on sexual orientation continues to be notable by its absence. The same Bulletin announces that sexual orientation data will be included as from the next bulletin which will be published some time in 2014 ([20], p. 5).

Another troubling silence is to be found in the 2013 Annual Report of the Judicial Diversity Task Force [11]. The Task Force has the job of pursuing and monitoring progress towards the recommendations contained in the Ministry of Justice’s Advisory Group report [10]. “Appendix 4” of that 2013 Task Force report contains ‘Diversity Statistics’ relating to the make-up of the Legal Professions and the Judiciary. ‘Appendix 5’ brings together data on the ‘diversity of the eligible pool’ with data on the ‘diversity of current office holders’. In both the only categories of diversity mentioned are gender and BAME. Data on professional background is also included under the term ‘diversity’. There is no information about the sexual composition of the judiciary or the pool of possible appointees. There is also no mention of the progress, or lack of progress, being made towards a sexually diverse judiciary.

It is particularly surprising therefore to read in the 2013 report that the “essential”’ work of “...capturing, handling, sharing and regular updating of judicial data between the Ministry of Justice, Judicial Appointments Commission, and the Directorate of Judicial Offices” is “complete”’([18], p. 13). The Task Force’s conclusion that the current state of diversity information is sufficiently robust to provide a baseline against which it will measure future progress ([18], p. 14) is also open to serious doubt. With regard to sexual diversity it is clearly incorrect. Another goal of the Task Force is to ensure that there is systematic, consistent monitoring and evaluation of what works and what does not. Work on the achievement of this goal is described as “ongoing” ([18], p. 14). While this conclusion is welcome serious doubts must be raised about the nature of that ongoing project when there is an ongoing absence of any data on the sexual or gender identity composition of the judiciary or of the pool of eligible applicants. “Ongoing” doesn’t quite capture the fact that data collection has in many respects yet to start.

7. Concluding Remarks and Some Modest Proposals for Future Reforms

There are signs that change is beginning to happen. The JAC’s annual report for 2010 published in July 2011 includes a case study of a gay man newly appointed to the role of Deputy District Judge (Civil) ([21], p. 36). These and the other initiatives referred to above are welcome. However, it remains the case that the judicial family, almost without exception, appear to be heterosexual [22]. Another initiative undertaken by the JAC working with InterLaw Diversity Forum has been to conduct a number of outreach events for LGBT legal professionals to raise awareness about the work of the JAC and the judicial appointments process. Again this is a welcome development but the InterLaw Diversity Forum data suggests a need for caution when it comes to working with neat divisions between LGBT and other groups currently under represented in the pool of applicants and judicial appointees. A silo mentality may work against recognition that LGBT experiences are shaped by ethnicity, gender, disability and so on. Likewise initiatives that target the other groups also need to incorporate awareness of the impact of sexual orientation upon those groups resisting the assumption of heterosexuality. The changes to the judicial appointments process introduced in the 2013 Crime and Courts Act in Schedule 13 part 2 of the Act are welcome but they are unlikely to have significant effect on the status quo. The likelihood of such a position ever arising is minimal. At best the reform is symbolic of a ‘commitment’ to promoting a more diverse judiciary without compromising appointment on merit. Despite these changes the fundamental problem of lack of data on the sexual composition of the judiciary is ongoing and needs to be addressed as a matter of urgency. The Ministry of Justice, the Lord Chief Justice, the JAC and all those organisations that represent the various branches of the legal profession who are eligible to pursue a career in the judiciary need to progress towards collecting data. In many respects when it comes to sexual orientation this is a first step still waiting to happen.

The InterLaw Diversity Forum Report contained some modest proposals to address the slow pace of reform and ongoing reluctance to embrace sexual diversity and gender identity in judicial settings. One proposal is that renewed efforts need to be made to ensure that a commitment to equality and the recognition of all strands of diversity is better embedded within the appointment mechanisms and related judicial institutions. Current statements about commitment to diversity need to be reviewed and refreshed with the objective of ensuring that all demonstrate in a clear and positive way a commitment to all strands of diversity including sexual diversity. Another is that the composition of the various decision making bodies involved in judicial appointments, particularly the JAC and the management of the judiciary must better incorporate and address all diversity strands, including sexual orientation. Related to this is a proposal that focuses upon the openness and transparency of the appointments process. Currently the appointment of the senior judiciary takes place behind closed doors. More needs to be done to open up the process and to make it more transparent. A proposal to change this is for a transcript of the appointment interview of the successful candidate for senior judicial appointments, to be published, made available via the new appointee’s judicial biographical web page together with a full CV. 8

Related to publicity concerning appointment is another proposal; to improve judicial representation in the public domain. There is currently little biographical data available about the senior judges in the High Court and above. If the current diversity of the judiciary is to be recognised then the individual members that make up the judicial family need to be more effective communicators of that fact. Other jurisdictions, such as South African [24] and Canada [25] are much more effective than the courts in England and Wales [26] or the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom [27] not only describing the professional virtues of current and past office holders but integrating diversity into that portrait of the senior judiciary and communicating the significance of this for the judicial institution. In relation to sexual diversity this is far from a proposal to get the judiciary to expose their private life to public scrutiny. As I have explored in other research [15], information about a judicial office holder needs to be dedicated to represent the virtues of the office holder and thereby the office of the judge. What is needed here is rigorous thinking about the value of diversity and its contribution to judicial practice, the legitimacy of judicial authority and the institution more generally.

Acknowledgments

The data at the heart of this project and the analysis of that data on which this paper is based would not have been possible without the support and co-operation of many individuals especially Stephen Ward, who was at the time of the project the Law Society’s diversity champion, Simon Robinson, Andrew Daum, Lee Smith, Pamela Bhalla of the Bar Council Equality and Diversity Committee, Ben Summerskill, Chief Executive of Stonewall, and Laura Hodgson, then co-chair of the InterLaw Diversity Forum and Jonathan Leonhart whose generosity and diligence ensured the publication of the original research report. The Judicial Appointments Commission played a key role in facilitating the research. Their consent to our use of a questionnaire developed for earlier research commissioned by the JAC was of vital importance to the success of this project. Particular thanks are due to all those who completed the online questionnaire. Without your gift of time, experience and insight none of this would have been possible. Daniel Winterfeldt, founder and co-chair of the InterLaw Diversity Forum deserves special thanks. His tireless efforts to establish, facilitate and fund this project played a fundamental role in this initiative.

Conflics of Interest

The original research was undertaken in conjunction with InterLaw Diversity Forum for LGBT networks and the use of the questionnaire had JAC approval. This paper has been produced independently of those organisations. The author reports no conflict of interest with any parties or institutions mentioned in this work.

References and Notes

- Anthony Allen. Barriers to Application for Judicial Appointment Research. Prepared for: Judicial Appointments Commission; London: British Market Research Bureau, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Igor Judge. “The Judicial Studies Board Lecture 2010.” In Inner Temple; 17 March 2010. http://www.judiciary.gov.uk/media/speeches/2010/jsb-2010-lecture. [Google Scholar]

- Erica Rackley. Women, Judging and the Judiciary from Difference to Diversity. Abingdon: Routledge-Cavendish, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lady Brenda Hale. “Equality in the Judiciary.” 21 February 2013. Available online: http://www.supremecourt.gov.uk/docs/speech-130221.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lizzie Barmes, and Kate Malleson. “The Legal Profession as Gatekeeper to the Judiciary: Design Faults in Measures to Enhance Diversity.” Modern Law Review 74, no. 2 (2011): 245–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kate Malleson. “Diversity in the Judiciary: The Case For Positive Action.” Journal of Law and Society 36, no. 3 (2009): 376–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kate Malleson. “Rethinking the Merit Principle in the Judicial Appointments Process.” Journal of Law and Society 33, no. 1 (2006): 126–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaret Thornton. “‘Otherness’ on the Bench: How Merit is Gendered.” University of Sydney Law Review 29, no. 3 (2007): 391–413. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie J Moran. “Judicial diversity and the challenge of sexuality: Some preliminary findings.” Sydney Law Review 28, no. 4 (2006): 565–98. [Google Scholar]

- Baroness Julia Neuberger. The Report of the Advisory Panel on Judicial Diversity; London: Ministry of Justice, 2010.

- Ministry of Justice. “Improving Judicial Diversity—Judicial Diversity Taskforce Annual Report 2013. ” Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-judicial-diversity-judicial-diversity-taskforce-annual-report-2013 (accessed on 26 September 2013).

- England and Wales Judge 2. Interview 20th October 2006. Copy on file with the author.

- Leslie J. Moran. “Forming sexualities as judicial virtues.” Sexualities 14, no. 3 (2011): 273–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Judicial Diversity Strategy: Measures of Success.” In Joint statement from the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chief Justice and the Judicial Appointments Commission Chairman; July 2006. Available online: http://jac.judiciary.gov.uk/static/documents/JAC_Statement_Judicial_diversity_strat_succ_0706.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2013).

- Leslie J. Moran, and Daniel Winterfeldt. “Barriers to application for judicial appointment: Lesbian gay, bisexual and transgender research.” Interlaw Diversity Forum for LGBT Networks. 2011. Available online: http://core.kmi.open.ac.uk/display/107049 (accessed on 22 October 2013).

- Tara Chittenden. Career Experiences of Gay and Lesbian Solicitors. Law Society of England and Wales Research Report. London: The Law Society, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Law Society, and Interlaw Diversity Forum. “Career experiences of gay and lesbian solicitors, Law Society of England and Wales Research Report.” The Law Society. 11 November 2010. http://www.lawsociety.org.uk/practicesupport/equalitydiversity/reports.page#lgb.

- Judicial Appointments Commission. “JAC expands its diversity monitoring.” 7 July 2011. Available online: http://jac.judiciary.gov.uk/about-jac/1365.htm (accessed on 29 February 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Accent. “Barriers to application to judicial appointment Report.” July 2013. Available online: http://jac.judiciary.gov.uk/static/documents/barriers_to_judicial_appointment_research_2013.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Judicial Appointments Commission Statistical Bulletin. “Judicial selection and recommendations for appointment statistics April to December 2013.” 5 December 2013. Available online: http://jac.judiciary.gov.uk/static/documents/JAC_publication_official_statistics_2013.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Judicial Appointments Commission. “Annual report 2012–13.” 11 July 2013. Available online: http://jac.judiciary.gov.uk/about-jac/167.htm (accessed on 29 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Leslie J. Moran. “To Be Judged ‘Gay’.” In Out of the Ordinary: Representation of LGBT Lives. Edited by Ian Rivers and Richard Ward. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Constitutional Court of South Africa. “Judges: Justice Thembile Skweyiya.” Available online: http://www.constitutionalcourt.org.za/site/judges/justicethembileskweyiya/index1.html (accessed on 15 December 2013).

- Constitutional Court of South Africa. “Judges: Current Judges.” Available online: http://www.constitutionalcourt.org.za/site/judges/currentjudges.htm (accessed on 16 December 2013).