Abstract

‘Deepfakes’ and other forms of digital communications disinformation are now on the virtual frontlines of many armed conflicts. Military commanders can potentially gain significant tactical advantages by misleading enemy forces, opposing governments, and civilian populations into believing X when Y is the true state of affairs. Distinct from military propaganda, deliberate deceptions and subterfuge have long been part of warfare. However, a powerful claim is advanced that deepfakes such as announcing surrender, truce declarations, or similar messages that place soldiers and civilians at greater risk are international humanitarian law (IHL) violations, notably under the 1907 Hague Convention and the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions. This four-section critical discussion considers whether, or to what extent, deepfakes are IHL compliant. Selected examples taken from the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war are highlighted to illustrate the potentially grave dangers that deepfakes represent for innocent civilian populations. IHL reform recommendations are made that would reduce deepfake harm—if such reforms are embraced by the international community (an admittedly doubtful prospect).

1. Introduction

This article examines whether and how deepfakes constitute perfidy under International Humanitarian Law (IHL), and what legal reforms might address this emerging challenge. The regulation of warfare under international law has long sought to mitigate the inherent brutality of armed conflict by imposing limits on deception and the targeting of individuals. Yet, the increasing use of synthetic media—particularly deepfakes—introduces a new dimension to the ethics and legality of wartime misinformation. Recent conflicts in Ukraine, the Middle East, and Sudan illustrate how digital technologies can amplify both strategic deception and civilian harm. As General William T. Sherman’s remark that “war is hell” (Sherman 2024) underscores, the horrors of conflict are not diminished by technological sophistication; rather, deepfakes risk intensifying them by obscuring the distinction between truth and falsehood, combatant and civilian, and ruse and perfidy.

This same notional observer might equally conclude that war is a ‘win at all costs’ exercise. It is a universally accepted warfare proposition that defeating, or otherwise neutralising an enemy force determined to capture, compel the surrender, or destroy its opposition is an overarching objective in any military engagement1. It logically follows that trickery, deception, and false information that mislead the enemy into a false belief regarding how such strategies will advance fundamental military and national self-preservation objectives2.

Artificial intelligence has dramatically altered the landscape of modern warfare. Among the most disruptive technologies is the deepfake—synthetic media generated through machine learning techniques such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), capable of producing hyper-realistic but false images, videos, or audio recordings. In the context of armed conflict, deepfakes can serve strategic purposes: disseminating misinformation, manipulating morale, or deceiving adversaries into tactical errors. These impressions are not always entirely aligned with what has become a comprehensive and (in theory) robust international humanitarian law (IHL) sphere3. IHL is also known as ‘the laws of war’ and the ‘laws of armed conflict’ (ICRC 2024d). For centuries before the international community’s early 20th century agreements were made regarding how combatants must treat each other and civilian populations (the 1907 Hague Convention),4 warfare had accepted standards of conduct. The notion that military commanders or their forces could adopt any measures that would help them achieve victory (sometimes described in the relevant authorities as ‘total warfare’, or war waged at all costs) was not an accepted ‘law of war’ principle (Sari 2024).

The following examples illustrate how these traditional limitations are placed on how warfare should be conducted (recognising that IHL theory might not match what happened on every battlefield) (Chelioudakis 2018). IHL customary norms include strict prohibitions against killing, torturing, or otherwise mistreating prisoners of war (POWs) (ICRC 2024b). War had to be formally declared between states before armed force could be directed at an enemy (subject to preemptive strike/self-defence exceptions (‘The Caroline’ test)5. In these respects, warfare could be conducted with the determination to destroy an enemy, but IHL principles emerged after the 1907 Convention that served as presumptive safeguards against the worst, most brutalizing forms of conduct (Warren and Bode 2014).

In 2024 and beyond, digital communications technologies will increasingly be utilized in military operations across the world. For present critical discussion purposes, ‘deepfakes’ are generally defined as intentionally deceptive artificial intelligence (AI)-generated disinformation campaigns directed at an enemy force, its government, or its civilian populations (Chawki 2024). As explored in greater detail in Section 2, deepfakes are conceptually distinct from other communications-based military tactics such as propaganda campaigns that States might direct at enemy States’ armed forces, government leadership, or the broader civilian population. Similarly, where State agencies selectively edit available video footage to convey a specific impression concerning military events, such conduct does not always fall within the umbrella deepfake definition employed here (Hague Centre for Strategic Studies 2023).

In essence, a deepfake is designed to encourage a false belief within an enemy force that its perpetrator will then exploit to its advantage. Of numerous examples explored throughout this critical discussion, video messages declaring that a ceasefire has been reached between two combatants might convince the recipients that a conflict is over. When the targeted forces, government, or civilian population acts on the deepfake communication, the perpetrator’s force then moves to victory when its enemy lowers their guard based on an erroneous deepfake-generated belief (Jensen 2020).

These deepfake communications are now one of the most prominent and controversial of all modern armed conflict tactics when contemporary IHL principles are carefully considered. For their many detractors, deepfakes violate current IHL standards, especially those defined in the Geneva Conventions’ 1977 Additional Protocol I6. It is this contention that provides the entire article with both its commencement point and central research theme. Protocol I (Article 37) sets out the ‘Prohibition against Perfidy’7. This term carries the dictionary definition of ‘untrustworthiness’ or ‘deceitfulness’—a definition that is also given more extensive attention in the later discussion sections (Cambridge Dictionary 2024c). When placed against the armed conflict—so-called total war, ‘win at all costs’ military actions mentality outlined above—this Article 37 language thus raises the primary critical discussion issue: when, or in what specific respects, do deepfakes cross the defined IHL boundaries created between lawful and illegal armed conflict conduct?

Section 1 sets out the key IHL concepts that frame this entire deepfake discussion. In Section 2, the AI technology used to create deepfakes is identified and explained. These section sources contribute to appreciating how the selected Section 3 deepfake examples have proven controversial for many present-day IHL commentators and international policymakers. Russia–Ukraine war deepfakes are given specific Section 3 discussion attention, as these examples have been extensively highlighted in both current academic research and mainstream media commentaries (Twomey et al. 2023a). Section 4 sets out the discussion, conclusion, and law reform recommendations that have an admittedly speculative quality. Significant doubts are expressed that any of the recommended IHL reforms devised to better control deepfake use can be implemented quickly enough to make a meaningful difference regarding how military operations are conducted. In essence, deepfake technology has raced ahead of the international community’s ability to control it (Twomey et al. 2023a). A sobering assertion anchors the discussion conclusion: it seems highly likely that deepfakes are here to stay.

Primary research focus is directed at current IHL provisions governing (or potentially suitable for governing) how deepfake technologies are used by military forces and their governments in armed conflicts. This research direction necessarily requires a review of the legal doctrines that provide IHL and its key instruments with their foundation (Creswell and Creswell 2018). It is likely impossible to do any justice to this topic without concentrating on what the law is today.

However, by its nature, AI and deepfakes have a societal influence that is arguably distinct from how IHL principles apply. For this reason, the research also incorporates socio-legal elements where appropriate (Fox-Williams 2019). The end result is a mixed methods research approach that remains flexible as the project is taken from its initial proposal stage to final submission form. Flexibility is especially important in this research area, given the rapid advances AI applications are making, new scholarly AI analyses then emerge, and new deepfake examples emerge from current warzones.

2. International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and the Geneva Conventions—Key Concepts

2.1. IHL Definitions and Distinctions

As noted in the Introduction, present-day IHL principles have evolved over time from customary public international law (PIL) norms. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) statute confirms that PIL has four potential sources, namely treaties ratified by States, customary international law, high-level legal opinions, and generally accepted legal principles8. This PIL framework aligns with international law, being understood as the ‘law of States’9.

In this important respect, IHL is understood as a PIL subset. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) IHL definition is universally accepted as accurate: a set of rules designed to limit the effects of armed conflict on humanitarian grounds (ICRC 2024d). IHL rules protect any persons “… who are not, or are no longer, directly or actively participating in hostilities, and imposes limits on the means and methods of warfare” (ICRC 2024d). A preliminary observation is prompted here. A ‘deepfake’ as defined above that remains within accepted IHL definition boundaries should not cause or contribute to civilian harm (Meier 2025). This observation is further considered below.

It is important to underscore where IHL is distinct from other PIL frameworks that are connected to war. IHL measures regulate how parties involved in an armed conflict conduct their military operations (jus in bello) (Solis 2021). By contrast, when States may lawfully resort to using armed force when dealing with another State is defined in the 1945 United Nations Charter (jus ad bellum)10. The Charter prohibits States from using such force, with two limited exceptions: (1) self-defence measures taken against an armed attack or (2) when the UN Security Council authorizes such force11. IHL principles are not used to determine whether a State’s involvement in an armed conflict was legitimate. Instead, IHL seeks to impose controls on the opposing parties’ actions once an armed conflict has begun (Crawford 2024).

2.2. The 1949 Geneva Conventions and IHL

These Conventions are widely recognized as part of IHL’s core structure (ICRC 2024c). They build upon the cited 1907 Hague Convention sentiments, ones that were seemingly ignored during the often barbaric World War I battles that were more akin to massive, almost endless human slaughters than armed conflicts governed by accepted legal principles (Cabanes 2020). In 1907, Convention IV provisions were adopted that made killing or wounding ‘treacherously’ an illegal act (Schindler and Toman 1988). The Conference then added acts of ‘capturing’ as part of the perfidy prohibition, and it is possible to draw a straight conceptual line between the 1907 Convention and modern perfidy prohibition concepts that now encompass other acts of war committed in conflict zones (Schindler and Toman 1988).

It is noted that in both World Wars that preceded the 1949 Convention enactments, conduct that today would constitute war crimes under international law (as defined by the 1998 International Criminal Court statute) was widespread12. Of numerous scholarly examples, Bruno Cabanes outlines how war crimes were part of the First World War conflicts (such as rapes committed against civilians, POWs being killed without justification, and genocides) (Cabanes 2020, n 32, pp. 288, 289). One might reasonably conclude that deepfake controversies pale in comparison to such horrific ‘total war’ outcomes (a point that also contributes to the Section 3 commentary) (Cabanes 2020, n 32, pp. 288, 289).

These are important points of emphasis when IHL evolution is carefully considered. Throughout its history, IHL’s true regulatory effect in limiting harm suffered by persons who are not “directly or actively participating in hostilities” or actually limiting warfare methods is legitimately doubted (Williamson 2010). No issue is taken in this IHL deepfake discussion with this proposition: the international community should strive to implement and enforce the IHL measures outlined above. However, as the discussion points developed in here and in Section 3 reinforce, this international law area’s compelling, attractive theoretical rationales are not matched by practical, demonstrated outcomes. The well-known expression, ‘rules that are more honoured in their breach than through their observance’ reflects IHL Geneva Convention realities, as the following selected 1977 Protocol 1 Article 37 provisions also confirm (Ellis 2007).

2.3. Geneva Conventions and the 1977 Protocol I Article 37—A Deconstruction

The project’s Introduction highlights how Article 37 was devised to prevent armed forces from resorting to ‘perfidy’ in their conduct of any military operations directed at an enemy13. The IHL framework outlined above reveals conceptual linkages connecting IHL customary norms, Article 37 perfidy, and how deepfakes are correctly understood (US Department of the Army 2019). It is useful to deconstruct the entire Article and thus gain a fuller appreciation of how military deception tactics involving perfidy and deepfakes have become interconnected concepts for commentators such as Eric Jensen (Jensen 2020) and David Allen (Allen 2022).

Article 37(1) commences with this unambiguous if generally stated prohibition: “… It is prohibited to kill, injure or capture an adversary by resort to perfidy”14. The Article then provides an expanded definition, one that aligns with the Cambridge Dictionary extract cited in the Introduction: Perfidy will include any actions undertaken during an armed conflict “inviting the confidence of an adversary”, where this party is led to believe that they are “entitled to, or is obliged to accord, protection under [IHL] rules applicable to armed conflicts”15. Perfidy is thus equated with an armed force intending to betray its adversary’s confidence.

This definition also assists in appreciating which military deception tactics do not fall within the perfidy definition. Propaganda is arguably the most important of these distinct concepts for present discussion purposes. It is defined as any messaging “…aimed at a specific audience that will try to change their thinking” to align with propagandists’ views (Aswad 2023). Propaganda messages might also contain disinformation promoting specific political beliefs (Aswad 2023). It is noted that under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1967 (ICCPR 1967) Article 20(1) states that any war propaganda shall be legally prohibited16. The following perfidy scenario is presented and understood accordingly.

2.4. A Perfidy Scenario?

This opening Article 37(1) language provides this hypothetical example with its context. States X and Y are in the midst of a declared war. They are historic enemies. There is significant third-party evidence (neutral ICRC conflict observer) that X’s forces have engaged in genocide and war crimes (several hundred male Y citizens have been summarily executed during this conflict; many Y females have been raped by X soldiers).

Y sets a trap for X. A seemingly quiet farming village (Z) located near the X–Y conflict zone is described in Y media broadcasts as having few male residents because they are now fighting in Y’s military units. X’s commanders sent a 500-soldier force to capture Z. Y’s forces are hidden throughout Z and around its perimeters in camouflage uniforms. When X soldiers enter Z, they are attacked and killed by Y’s soldiers. It is apparent that but for this Y misinformation being acted upon by X, the X forces would not have attacked Z. On a literal Article 37(1) reading, Y has committed perfidy. The fact that X’s forces may previously have engaged in criminal conduct does not mean that these X soldiers ordered to capture Z would necessarily do the same (Y cannot establish that Z’s population was at risk of genocide or war crimes being committed by X) (Allen 2022).

However, recalling why Sherman described ‘war is hell’ (Sherman 2024), X is plainly committed to defeating Y. One may ask that when the respective X and Y interests are considered, are Y’s broadcasted messages simply consistent with Y taking all available steps (short of ‘total war’, or other international criminal law prohibitions as outlined above)17 to defeat an adversary (X) representing an ever-present danger to Y’s existence and its people’s safety (Hall 1995)? Many reasonable observers might conclude that Y’s deceptions ultimately contributed to protecting its territory and people from X.

Article 37(1) sets out specific perfidy prohibition examples. The Article language suggests that this list is non-exclusive. It includes: (i) “feigning an intent” to negotiate with the enemy under a flag of truce or of a surrender; (ii) feigning incapacitation (wounds or sickness); (iii) feigning civilian, non-combatant status (thus claiming undeserved IHL protections); (iv) feigning of protected status (such as wearing a United Nations uniform)18. These examples are plainly well-aligned with the Article 37(1) perfidy definition.

The Article 37 unlawful perfidy–lawful armed conflict conduct definition boundary is provided in Article 37(2): “Ruses of war are not prohibited”19. On their comparative literal meanings, perfidy (untrustworthiness, deceitfulness) and a ‘ruse’ might seem similar. However, Article 37(2) explains that ruses are innocent armed conflict activities where the party intends to mislead their adversary or to induce him to act recklessly. The ruse is innocent where perfidy is not so long as the ruse does not infringe any IHL rule, and “…are not perfidious because they do not invite the confidence of an adversary with respect to protection under that law…”20. Article 37(2)’s ruses specifically include “the use of camouflage, decoys, mock operations and misinformation…”21.

Returning to the X–Y–Z scenario presented above, Y can likely successfully argue that its communications made about Z village were ruses, and not perfidy. It seems doubtful that X could ever establish that its soldiers entered Z with false confidence in their IHL protections (the Article 37(2) ruse qualification). However, the key point extracted from this scenario is subtler—the perfidy–ruse definition boundary is plainly challenging to apply in practice. Where this boundary line is drawn in a given case is highly circumstance-specific, as the ICRC examples presented below also confirm. Prior to moving into the case study discussions, it is important to highlight other IHL instruments that contribute to how armed conflict disinformation campaigns are potentially unlawful.

2.5. Other IHL Measures Applicable to Perfidy and ‘Disinformation Wars’

An insightful 2020 Lisa Cohen article and its analysis of modern military ‘disinformation wars’ is highly instructive regarding how IHL frameworks can apply to deepfakes. Cohen emphasises two additional IHL legal sources. The first is Additional Protocol I Article 36—‘New Weapons’ (Cohen 2020). All States assume a positive legal obligation when they have engaged in the “study, development, acquisition or adoption of a new weapon, means or method of warfare” (McClelland 2003). Such States are obliged to determine whether the new development “…would, in some or all circumstances, be prohibited by this Protocol or by any other [international law] rule” (Lawand 2006). Deepfake technologies are logically a ‘means or method of warfare’ (Klonowska 2020).

Secondly, the 2017 Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Operations (Tallinn Manual 2.0) is an accepted, if non-binding, IHL authority explaining how IHL measures apply in cyberspace (virtual world) contexts. Cyberspace is given more intensive Section 2 attention, but the following Tallinn Manual 2.0 guidance directly contributes to why deepfakes demand closer IHL regulatory attention (Schmitt 2013). Under Tallinn Manual 2.0 Rule 80, IHL applicability to cyber operations has a key precondition: an armed conflict must exist (Schmitt 2013, Rule 80).

On this basis, when deepfakes are utilised during an ongoing armed conflict, the same IHL rules necessarily apply as otherwise govern conventional warfare means and methods. These rules will govern deepfakes, even where the rules’ language “might not be sufficient or appropriate in the context of information warfare” (Cohen 2020). The above Article 37 comments collectively confirm that current IHL measures do not directly deal with deepfakes, subject to how one defines the disinformation–ruse boundary.

Deepfakes—synthetically altered media using AI—can be weaponized in armed conflicts to create deceptive battlefield scenarios. If used to misrepresent the location of soldiers or military units, they could feign surrender or civilian status. A deepfake video falsely portraying a surrendering military unit, prompting the adversary to cease hostilities, could be perfidious if the depicted forces use the deception to launch an attack. A deepfake simulating a civilian distress call or false medical evacuation could induce an adversary to lower its guard, making it vulnerable to attack. A deepfake of a military commander issuing fake orders, misleading forces into moving to a compromised position, could result in the unlawful capture or killing of those troops, fulfilling the criteria of perfidy.

Satellite imagery is crucial in military strategy and targeting decisions. Manipulating such data to mislead adversaries raises distinct legal concerns. Altering satellite images to depict civilian areas as military objectives or vice versa could lead to unlawful attacks, violating IHL’s principles of distinction and proportionality. If false satellite imagery depicts military assets as humanitarian sites, it could constitute perfidy if used to shield military operations from attack. Falsified satellite images showing non-existent troop movements may deceive an adversary into deploying forces into an ambush, potentially constituting perfidy if it results in prohibited acts.

A final Additional Protocol I provision supplements this particular discussion point. It is possible that not all misinformation-based ruses, or deepfakes used in contexts that do not involve a direct attack on an enemy force, are automatically (or at least prima facie) lawful (Jensen 2020). A deepfake application employed to “affect, influence, or deceive civilians” is likely an IHL violation on two bases. The first is Additional Protocol Article 57.1, where armed forces must adhere to a standard of constant care regarding how civilians are treated (including treatment of their property)22. Two AP items I restrict the usage of deepfakes significantly. First, a requirement of continuous care for civilians and their property during armed conflict is explicitly established under Article 57.1. Second, Article 51.2 states that in order to propagate terror, civilians cannot be the target of threats or violent acts.

For example, the deepfake’s misleading information that appeared plausible but was ultimately false led Green Republic soldiers to inform citizens that Yellowland was about to surrender. After that, the civilians departed their safe havens. As a result, there were far more civilians caught up in the fighting when Yellowland launched its invasion than there would have been otherwise. It’s possible that Yellowland broke its obligation to provide continuous care for civilians. The use of deception in armed conflicts through the dissemination of false information is a well-established method of warfare. Deepfakes, as a highly sophisticated and hyper-realistic form of this practice, present new legal and ethical challenges, as illustrated by the following examples:

Example 1: State A creates a deepfake in which the military commander of State B orders a retreat from strategically significant locations. State A then disseminates this video to State B’s armed forces via social media, aiming to secure a military advantage. The legality of such deepfakes hinges on their potential impact on civilian populations. The duty of constant care (Article 57(1) API), the principles of distinction (Article 48 API) and proportionality (Article 51(5)(b) API), as well as the prohibition of acts intended to spread terror among civilians (Article 51(2) API, Article 13(2) Additional Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions), could impose legal constraints on their use in armed conflict.

Example 2: State A produces a deepfake simulating a conversation between State B’s president and military commander, falsely suggesting an imminent nuclear attack on the capital of State C. This video is then disseminated via social media, primarily to incite panic among the civilian populations of States B and C.

While the duty of constant care and the principle of distinction apply universally to military operations, the principles of proportionality and the prohibition of terror-inducing acts specifically govern “attacks” and acts of violence or threats thereof. The classification of deepfakes under these principles presents challenges, as there is little precedent defining what constitutes an “attack” in cyber warfare. According to Article 49(1) API, an “attack” involves “acts of violence against the adversary”23. Rule 92 of the Tallinn Manual 2.0 interprets violence in terms of consequences rather than merely physical acts24. However, Rule 98 asserts that a tweet falsely claiming the rapid spread of a deadly disease, aimed at inducing panic, does not qualify as an attack or a threat thereof under Article 51(2) API25. This raises the question: Can fake news never constitute an attack, act of violence, or threat thereof?

Unlike the example in Rule 98, which involves misleading information without direct state attribution, the deepfake in Example 2 is of a different nature. Given the difficulty of detecting deepfakes, they are likely to be perceived as authentic upon initial exposure. Consequently, the deepfake in Example 2 could have an impact on State C and its civilians comparable to that of a real announcement of a nuclear strike. However, under the existing legal framework, Rule 92 of the Tallinn Manual 2.0 permits operations that cause “inconvenience or irritation” without foreseeably resulting in physical harm or property damage26. As such, despite the potential for widespread panic and terror, the deepfake in Example 2 would currently be considered a lawful non-attack.

Similarly, the dissemination of the deepfake in Example 1 through social media raises concerns regarding compliance with the principle of distinction and the prohibition of indiscriminate attacks (Article 51(4) API)27. Given the interconnected nature of cyberspace, it is nearly impossible to ensure that such content remains confined to military audiences, making civilian exposure highly probable. The classification of the deepfake’s objectives as either civilian or military is ultimately dependent on whether it qualifies as an attack. Rule 93 of the Tallinn Manual 2.0 states that operations targeting civilians are only prohibited if they constitute an attack, while operations directed at military targets must adhere to the principle of proportionality—applicable only to attacks28. Additionally, Rule 105 states that cyber weapons causing uncontrollable cascading effects are inherently indiscriminate29. Though social media can spread information unpredictably, a deepfake that does not foreseeably cause injury or damage—such as the one in Example 1—would not be deemed indiscriminate. Therefore, under current legal interpretations, Example 1 would also be considered lawful.

Secondly, under Article 51(2) civilian populations must not be subjected to threats or acts of physical violence that are intended to spread terror. Using the basic X–Y scenario premise, if X created deepfake images of its armed forces raiding, looting, or otherwise causing widespread civilian destruction across Y’s territories and broadcast these to the Y civilian communities, an Article 51(2) violation seems provable30. Jensen and other commentators accept that any deepfakes that are devised to cause panic among civilian populations are unlawful. For non-state actors, like terrorist groups or insurgent movements, deepfakes might be extremely helpful in developing an asymmetrical strategy through the use of highly emotional fake content. This would boost recruitment and hatred toward the targeted opponent. As a result, these actors may use heated words to provide believable but phony audio or video materials of their competitors. Frequently cited examples of disinformation campaigns that would potentially generate civilian hysteria are deepfakes claiming a “nuclear attack, severe natural disaster, or biological attack is imminent” (Jensen 2020). The ICRC case study is now discussed with these further IHL authorities, providing guidance.

2.6. ICRC Case Study—Perfidy or Ruse?

The ICRC is likely the most prolific generator of high-quality IHL analysis and discussion, as the many ICRC sources cited throughout this project collectively confirm. It published a case study based on an actual 1995 event that occurred during the often-vicious Yugoslavian civil wars (‘Bosnia and Herzegovina, Using Uniforms of Peacekeepers’) (ICRC 2024a). In May 1995, Bosnian Serb soldiers donned stolen French uniforms and flack jackets to take control of an UN-controlled bridge in Sarajevo. These Serb forces took 400 UN hostages, 21 armoured personnel carriers, six light tanks and three armoured cars (ICRC 2024a). All UN forces had been deployed as peacekeepers in this conflict—they were not enemy combatants as understood in all conventional IHL—1977 Additional Protocol contexts (ICRC 2024a).

When deepfakes manipulate legally protected signals or communications, they cross into perfidy. The following subcategories illustrate potential violations: (a) Feigned Surrender or Cessation of Hostilities—A deepfake depicting an enemy commander ordering surrender or withdrawal clearly constitutes perfidy, as it invokes the protection accorded to those hors de combat. (b) Abuse of Humanitarian Symbols or Personnel—Fabricating videos or voice messages of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) or United Nations personnel falsely directing civilians could be perfidious under AP I Articles 38–39. (c) False Medical or Civilian Status—A deepfake showing combatants disguised as medics or civilians could equally violate IHL. These examples underscore that intent and context determine liability. The crime of perfidy requires the intent to betray confidence and a causal nexus between that betrayal and death, injury, or capture.

Conversely, deepfakes may serve as legitimate stratagems if they mislead the enemy without invoking legal protections. Psychological operations (PSYOPs) have long used fabricated radio transmissions, false broadcasts, or deceptive communiqués to erode morale. Such operations are permissible provided they respect distinction, do not cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering, and do not abuse IHL-protected trust. In this sense, deepfakes that portray tactical situations (e.g., feigned troop movements or simulated destruction of bridges) are akin to camouflage or decoys—lawful under the tradition of ruses de guerre.

The ICRC case study authors pose these provocative questions, ones that also contribute to understanding why the perfidy–ruse definitional boundary is potentially problematic: Is the Bosnian Serb armed forces wearing of peacekeepers’ uniforms prohibited under IHL, Article 37(1), even if no armed conflict exists between the UN peacekeepers and the Bosnian Serb forces (ICRC 2024a)? One might argue that unless a state of war exists between the two forces, the Article 37 perfidy prohibitions are not applicable—thus leaving a significant IHL gap in these particular circumstances. Specific perfidy and military propaganda interrelationships are now considered.

Propaganda has been part of human warfare for centuries (Guess and Lyons 2020). Consistent with the above-cited Aswand definition (Aswad 2023 (n 46) pp. 1, 8), Guess and Lyons distinguish propaganda from both misinformation (inadvertent or unintentionally incorrect communications) and disinformation—deliberately propagated materials that are intended to deceive their recipients. Modern-day ‘fake news’ is a disinformation subset, as this false media content will often include “… deliberately misleading articles designed to mimic the look of actual articles from established news organizations…” (Guess and Lyons 2020, (n 79), pp. 10, 13). If one recalls Article 37(1) and (2) perfidy prohibitions, disinformation will likely constitute perfidy when placed within an IHL context, but misinformation will potentially support a ‘ruse’ characterization (Katz 2020).

Other international law instruments speak to propaganda—war-related communications. The above-cited ICCPR 1967) Article 20(1) war propaganda prohibition is a notable example. The absence of clear ‘propaganda’ and ‘war’ definitions has prompted extensive scholarly criticisms, ones that indirectly contribute to the present discussion of perfidy–deepfake themes31. International law non-governmental organization (NGO) Article 19 has strenuously lobbied for more extensive anti-propaganda measures. This NGO makes its case based on a sobering, collective international community experience (UN 2023). It persuasively argues that propaganda promoting war often acts as a precursor to grave IHL violations, especially when the communications incitement others “… to commit genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity globally” (UN 2023). When war propagandists enjoy impunity from prosecution for their actions, future propaganda campaigns will likely enjoy greater acceptance (UN 2023).

3. Deepfakes and the Evolving Artificial Intelligence

The introductory deepfake definition is strongly influenced by the numerous ways that AI applications are now employed as military operations’ disinformation tools. The Section 1 disinformation versus misinformation distinction now acquires additional discussion importance. As noted above, deepfakes are deliberately deceptive communications—targeted messages directed at enemy forces, populations, or governments to encourage erroneous beliefs (‘confidence’) regarding the opposing perpetrators’ actual military intentions (Corn and Pascucci 2018).

Corn and Pascucci observed in 2018 (prior to AI applications becoming dominant economic, social, and technological forces) that “… the line [drawn] between permissible and impermissible deception, ruses, perfidy, and the passive obligation of distinction lies has never been entirely clear and has varied with state practice over time…” (Corn and Pascucci 2018). There is clear academic harmony concerning a core proposition: accidental or careless deepfakes are oxymoronic concepts. Deception and deepfake must be regarded as synonymous terms32.

The creation of a deepfake video typically begins with inputting numerous images into a type of machine learning system known as a neural network. This network identifies statistical patterns linking visual features in the images to the output the creator intends to produce. For instance, if the goal is to fabricate a video of former U.S. President Barack Obama delivering a speech he never gave, the neural network will learn how specific words correlate with the movement of his mouth. Similarly, to place Obama’s face onto another person’s body, the network will map the relationship between his facial features and the target body.33

When the objective is to generate entirely new imagery rather than combine existing visuals, a technique called a generative adversarial network (GAN) is used. GANs consist of two competing neural networks: a generator, which produces synthetic content based on the data it has been trained on, and a discriminator, which assesses the authenticity of that output by comparing it to real samples. The discriminator assigns a probability score—close to 1 if it deems the output genuine and 0 if not—and this feedback allows the generator to refine its output, reducing detectable signs of manipulation (Donahue et al. 2019).

GAN-based approaches are also applied to audio deepfakes. One example is WaveGAN, which can synthesize new speech from as little as 40 min of recorded audio of an individual’s voice. Like its visual counterpart, WaveGAN uses a generator to produce speech and a discriminator to assess its authenticity. However, audio synthesis still faces limitations, particularly with phrasing and intonation, and WaveGAN is most effective at producing short, coherent segments of sound.

Because deepfakes involve complex manipulation of visual and auditory data, they often introduce subtle irregularities—such as unnatural shadows, abrupt speech transitions, or inconsistencies in resolution. While these flaws may escape human perception, advanced detection algorithms can sometimes identify them. Yet, such tools have limited reliability over time: as deepfake models continually learn and self-correct, detection methods that work today may quickly become obsolete (Meserole and Polyakova 2018).

A major contribution to the legal and policy literature on deepfakes comes from Danielle K. Citron and Robert Chesney, who provide one of the earliest and most comprehensive analyses of the technology’s social, political, and legal implications. They argue that deepfakes—defined as hyper-realistic, AI-generated falsifications of image, audio, or video—pose severe risks not only to individual rights but also to democratic governance, public trust, and national security. Their discussion of how deepfakes can distort democratic discourse, erode confidence in institutions, and exacerbate social divisions is directly relevant to international humanitarian law, where similar dynamics could heighten the dangers of information operations during armed conflict. Moreover, their identification of the “liar’s dividend,” the phenomenon whereby the mere existence of deepfakes enables wrongdoers to dismiss authentic evidence as fabricated, highlights the evidentiary and accountability challenges such technologies pose in conflict settings. The proliferation of deepfakes and the phenomenon known as the “liar’s dividend”—wherein the existence of synthetic media allows wrongdoers to deny authentic evidence—have significant implications for the core principles of IHL. The principle of distinction requires parties to an armed conflict to differentiate at all times between combatants and civilians, while the principle of trust and good faith underlies prohibitions on perfidy and deceptive conduct that exploit protected status. When deepfakes are used to simulate official communications, falsify surrender messages, or manipulate humanitarian broadcasts, they erode the reliability of information necessary for the protection of civilians and the wounded. In this sense, the liar’s dividend undermines the protective purpose of IHL by fostering general disbelief in legitimate humanitarian signals, thus blurring the line between lawful ruses of war and prohibited acts of perfidy. The technical ease of creating and disseminating deepfakes, therefore, not only generates societal confusion but also poses a structural challenge to the integrity and enforceability of IHL norms in the information environment of modern warfare. This analysis underscores the urgent need to adapt legal frameworks—including the law of armed conflict—to address the operational and normative disruptions deepfakes create (Citron and Chesney 2019).

3.1. How Are Deepfakes Created? Technical and Layperson Explanations

From a terminological standpoint, both “disinformation” and “misinformation” denote false or inaccurate information, but they differ in intent: disinformation is false information shared deliberately to deceive or manipulate, whereas misinformation lacks that element of intention.34 The term “fake news,” while frequently invoked, is ambiguous and therefore used sparingly here; it often falls within one of the two categories above. Related notions such as “propaganda,” “psychological operations,” “influence operations,” “information operations,” “information warfare,” and “cognitive warfare” may also involve various mixtures of deceptive, misleading, or even accurate information.35 To maintain conceptual clarity, this article refrains from using these terms. If one assumes that deepfakes may violate 1977 Protocol I Article 19 perfidy prohibitions, understanding how deepfakes are created is essential to determining how best to build a more robust IHL regulatory framework. There are many AI applications that can conceivably be used for deepfake purposes. OpenAI ChatGPT app is a well-known product and thus suitable for current illustrative purposes (Open AI 2023).

Saudi Arabian scholar Mohamed Chawki explains how two digital technologies are essential to deepfake generation (Chawki 2024). He notes that deepfake technology represents an “… evolution of generative networks in adversarial training”, where training an AI system is achieved through “… simultaneously optimizing two neural networks, one that generates data and another that evaluates the generated data to assess its accuracy” (Chawki 2024). The first network (generative adversarial networks (GANs)) is deployed to manipulate existing images or videos to generate convincing products that make distinguishing them from reality difficult without sophisticated forensic tools (Chawki 2024).

A deepfake developer utilizes a generator network that creates the fake content. At the same time, the developer’s discriminator network is learning (the LLM processes outlined above) to successfully distinguish between real and fake content. The two networks will repeat these processes until the generator produces content approaching an identical match with its real content—a convincing deepfake is now ready for use (Chawki 2024). This GANS–deepfake technology interrelationship is on full display in the Section 3 military campaign IHL examples.

The following non-technical ChatGPT summary explains how a deepfake could be created using this technology. ChatGPT is part of a Large Language Model (LLM) system where its underlying algorithm effectively permits the app to ‘train’ on many billions of accessible internet data sources and digital platforms. When a user prompts ChatGPT for an answer to a question, the app will generate a text response based on its training. For example, the question “What is a deepfake and how is it used in military operations?” generated the answer attached as Appendix A in less than 10 s36.

One may readily imagine how specific text prompts given to ChatGPT would generate more elaborate answers if the user’s intentions are to create disinformation as understood in a 1977 Additional Protocol I, Article 37 context. These AI apps can assist a user in modifying (‘doctoring’) existing video or audio recordings to make them appear real—the essence of ‘deepfake’ objectives37. This specific video modification technique goes beyond simple editing of actual digital content—viewer/audience deception is the goal. Other graphics and sound effects (such as taking a living person’s voice and altering their words to create a disinformation communication) can be added to the final product (Smuha 2021). The Section 3 deepfake examples taken from current global war zones confirm the remarkable potential that deepfakes have to influence their recipients or broader target audiences (Allen 2022, n. 4, pp. 2–5).

3.2. An AI-Generated Military Deepfake Example

Cohen provides this useful military deepfake creation summary. Deepfake algorithms derived from AI and LLM research are used to create new audio and video. An individual’s voice, face, or both are digitally merged or replaced with “manipulated and artificial data” (Blaszkowska 2025). This new material is automatically tailored to match any desired output dimensions and conditions (i.e., what the target audience will see and hear). These AI apps only require a brief voice recording to create a “voice skin”, one that can be reprocessed “to say virtually anything” (Cohen 2020, n 57). Using the Section 1 X–Y scenario example, the deceptive Y media broadcasts might feature a well-known Y government spokesperson ‘speaking’ through a voice skin to add further credibility to the fake Y messaging (Cohen 2020, n 57).

By its nature, AI has become increasingly intuitive. The LLM algorithms have the ability to detect patterns revealed in large datasets. The ChatGPT app thus ‘learns’ from and generates similar products as those it encountered and absorbed through its training cycles (Cohen 2020, n 57). The learning process is also self-replicating, in that ChatGPT also learns from other accessible forensics algorithms that teach the app where improvements can be realized during the next production cycle (Cohen 2020, n 57). Ongoing, non-IHL deepfake regulatory efforts are now considered against this digital technology backdrop.

3.3. Current Deepfake Regulation Outside of IHL

The Section 2 Article 37 discussions confirm that deepfakes, as highlighted throughout this project, are not specifically defined under IHL, nor are their technological parameters necessarily covered by the Article 37(1) prohibitions made against perfidy, or the permitted Article 37(2) ‘ruse’ uses38. The Appendix A ChatGPT text response includes an assertion that inspires this Section 3 subsection: “… It’s important to note that the ethical implications and potential for misuse of deepfakes raise serious concerns, and many nations are exploring ways to combat the risks associated with this technology…” (Appendix A).

While the current discussions are primarily directed at IHL and its present ability to deal effectively with deepfakes, the current efforts being advanced by international community members to control deepfakes in non-armed combat settings deserve independent attention. These regulatory efforts directed at what are largely civilian-controlled cyberspace activities might assist in determining whether, or to what extent, it is possible to control how States and their military leadership use deepfakes (Corn and Pascucci 2018, (n 87), p. 8).

Sheldon makes this important additional point, one that emphasises why deepfake control is not solely an IHL definitional regulatory issue that can be resolved through IHL reforms (Sheldon 2016). Cyberspace is the umbrella term used to describe the contemporary internet–virtual world: “…an electronic system that allows computer users around the world to communicate with each other or to access information for any purpose…” (Cambridge Dictionary 2024a). Deepfakes and any other digital communications employed by States or their military forces thus occur in cyberspace (Cambridge Dictionary 2024a).

For Corn and Pascucci, it is essential to understand that governments and their military organizations are often secondary players when third-party control is asserted over cyberspace activities. They observe that cyberspace is a human-made,

“…globally-interconnected environment stretching across international boundaries, under constant construction and modification, and built on chiefly civilian infrastructure that functions according to its own evolving protocols and logic…” (emphasis added).(Corn and Pascucci 2018, n. 87, p. 8)

When this technically worded definition is taken to its logical conclusion, one would logically expect cyberspace to ultimately remain controlled, or otherwise overseen by humans working for civilian State or international agencies. This point is highly contentious in the current AI deepfake literature, as further reinforced in the Section 3 military operations’ deepfake example discussion (Heikkilla 2024b).

Corn and Pascucci also note that over 90 percent of the networks that constitute cyberspace (including its physical (e.g., computer hardware) and virtual network layers) are “civilian owned and controlled” (Heikkilla 2024b). These systems are therefore usually located within an individual State’s sovereign jurisdiction (or subject to supranational control in the case of European Union cyberspace regulation)39. For this reason, Corn and Pascucci assert that, unlike physical domains, ‘international cyberspace’ is not a valid description of this sphere, given that “nearly all cyber operations occur on, in, or through civilian cyberspace infrastructure” (Corn and Pascucci 2018, n. 87, p. 9). These points further reinforce why a consideration of State cyberspace regulation efforts might usefully influence how the IHF deepfake Section 3 discussions and Section 4 law reform recommendations should be devised and enacted.

3.4. Specific Civilian Cyberspace Infrastructure Regulations

It is noted that in civilian contexts, deepfake technological applications often prompt publicly expressed concerns regarding their potential for harm, but they are not universally regarded as invariably harmful to public and private interests40. US-based technology NGO ‘Responsible AI’ cites the following example. Synthetic media (part of the above-cited deepfake definitions) is now being used to support the development of critical accessibility tools for individuals suffering from serious medical conditions (Responsible AI 2024). Responsible AI cites how a Canadian company has employed “deep synthesis” to assist ALS patients in communicating when these individuals have lost their ability to speak. This synthesis process allows the deepfake app to clone an individual’s voice, thus allowing them to continue “speaking” through the deepfake app (Responsible AI 2024).

Further, American scholar Melissa Heikkilla makes these observations concerning positive US government efforts to control deepfake uses, one that might also influence IHL policymakers (Heikkilla 2024b, n. 111). She outlines how the US Federal Trade Commission announced new rules banning deepfakes that impersonate living people. Further, “leading AI startups and big tech companies” are now making voluntary commitments to combating the deceptive AI use in election campaigns (Heikkilla 2024b, n. 111). These initiatives are consistent with a growing US legislative and public recognition that deepfakes carry risks both in and beyond armed conflict zones.

These positive deepfake technological developments aside, most observers have focused on the need to regulate deepfakes in the public interest, one that in these non-military and armed conflict contexts is similarly focused on disinformation (even where the Additional Protocol I ‘perfidy’ term is not referenced (Pepper 2021)). The following EU and US state-level regulatory initiatives are now considered.

3.5. EU

The European Parliament (EUP) has arguably taken the most assertive deepfake regulatory policy approach of any international community member state (European Parliament 2021). The EUP initiatives also contribute to how the Section 4 law reform recommendations are framed. The EUP deepfake definition is sound, as it is sufficiently flexible yet clear to be applicable in any deepfake context—political campaigns, social media networks, or communications linked to military operations. Paraphrased, the EUP describes deepfakes as any form of manipulated or synthetic audio or visual media with an authentic appearance. This media will invariably depict individuals who “… appear to say or do something they have never said or done, produced using [AI] techniques, including machine learning and deep learning [such as the LLM—ChatGPT models outlined above]” (European Parliament 2021, p. 5).

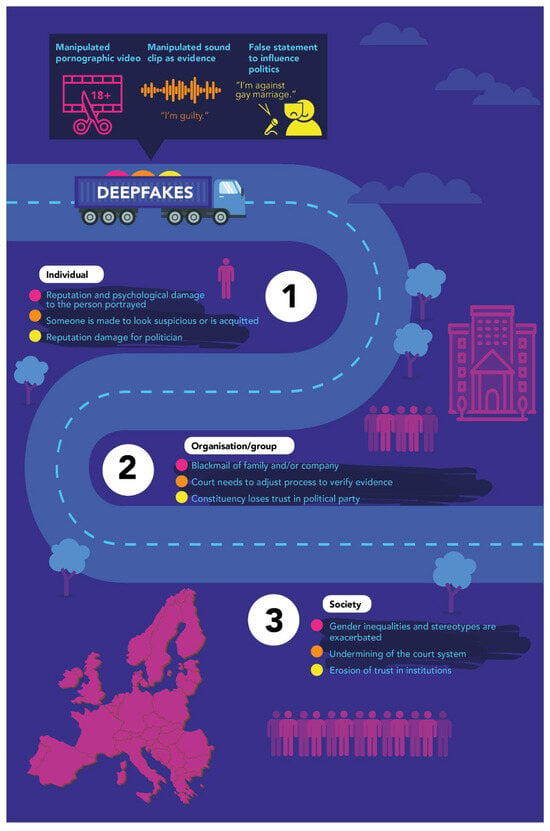

The cited EUP report highlights the positive and negative implications that are now associated with deepfakes. A full review of this detailed report is beyond the current discussion scope. One EUP point of emphasis provides an excellent bridge between the IHL instruments that potentially apply to armed conflict-related deepfakes and the non-military regulatory efforts the EUP endorses. The graphic reproduced here illustrates the ‘cascading effects’ of a successful deepfake disinformation campaign, where the deepfake carries the potential to disrupt the lives of individuals, organizations, groups, and society at large.

The newly enacted AI Act is the EUP Report’s legislative outcome41. The Act provides (among other AI regulatory mandates) that specific transparency risks must be identified by every AI application. Systems such as ChatGPT are now required to inform every user or communications recipient that they are interacting with a machine. Further, most AI-generated content must be labelled accordingly42. A pessimist who has the opportunity to view the remarkably realistic deepfakes created during the Russia–Ukraine war might contend that if one accepts that every ‘war is hell’, even the strongest, most robust, and comprehensive deepfake regulation is unlikely to deter military leaders from using disinformation tools if they can win an armed conflict (Responsible AI 2024, n. 116). This point also receives more concerted attention in Section 3 and Section 4 IHL recommendations.

3.6. US—California

Under its 2004 deepfake law, California has banned deepfakes from any use in political campaigns within 120 days of any fixed election date43. The prohibition extends to any “deceptive, digitally generated or altered content unless the ads are labeled as ‘manipulated’…”44. It is noted that this ban is controversial. Its numerous detractors argue that such bans violate the US constitutional freedom of speech guarantees45.

This California legislative measure and its deepfake ban–freedom of speech interplay has prompted similar IHL questions. It is noted that this personal freedom is also a customary international law norm. The ICCPR 1967 provisions cited above that are relevant to enforcing a disinformation–misinformation distinction were drafted and ratified across the international community, where freedom of speech/expression is defined in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights 1948 as:

“… Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers…”46.

It is noted that Geneva Convention Additional Protocol I Articles 37(1) and (2) disinformation (perfidy) and misinformation (ruse) boundaries are potentially ambiguous and thus difficult to precisely locate47. The same argument is raised regarding armed conflict deepfakes as freedom of expression. The Section 3 selected deepfake examples taken from current international military conflicts are now discussed in this light.

4. Applications of Deepfakes Under International Humanitarian Law

The following Russia–Ukraine war summary is not presented to favour one side over the other. There is ample evidence suggesting that Russia’s 2022 invasion of what the international community has long recognized as Ukraine’s sovereign territory violates international law (Panasyuk 2023). UN Charter 1945 Article 2(4) provides direct international legal authority for this claim: UN member states must refrain from the “use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state”48. Russia has argued that its inherent rights to “individual or collective self-defense” have been triggered, but this claim seems dubious given that little to no objective evidence exists that Ukraine was planning an armed attack against Russia prior to the 2022 invasion49.

It is not necessary to definitively determine which side is ‘right’ regarding the initial Russian invasion to engage in the following deepfake example discussion. These Section 3 points directly contribute to the Section 4 law reform proposals. They equally underscore the pragmatic observation made in the project Introduction—practical, effective IHL deepfake regulation may be impossible in an international community (Responsible AI 2024, n. 116).

The ongoing Russia–Ukraine conflict is likely the most sophisticated and extensive deepfake use in armed conflict history—an unsurprising assertion if one considers how quickly AI technologies have evolved in recent years (Chawki 2024. n. 12, pp. 1, 3). There is no doubt expressed here or in the later standalone Section 3 commentary that ever-accelerating AI technological power is a key reason why specific Deepfake–IHL reforms must be initiated—even if they do not ultimately provide the international community with optimal outcomes. AI power might continue to grow so rapidly that deepfakes might become entirely removed from effective legal oversight (including meaningful remedies when laws are violated) if international community inaction remains the norm.

The examples chosen for inclusion in this section have been curated from many deepfakes employed during the Russia–Ukraine war. The available literature suggests that Russian deepfakes have been more numerous than their Ukrainian-generated counterparts. This observation comes with a strong research methodology qualification. There is significantly more published work regarding Russian disinformation than exists concerning Ukrainian efforts made in this area (Twomey et al. 2023b). The examples are therefore presented in ways that limit the risk that Russian deepfake examples are overemphasized, given biased, pro-Ukraine treatment, or where Russian deepfake conduct is regarded as ‘worse’ than any similar campaigns mounted by its Ukrainian enemy50.

4.1. 18 February 2022

On this date, anyone visiting a Ukrainian news website would have been afforded the opportunity to watch a video of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. The audio and video showed what seemed to be Zelensky’s face, but a careful observer might have noticed that the facial features appeared slightly out of alignment (Twomey et al. 2023b, n. 137). The video captured Zelensky making a dramatic announcement, namely that the war was now over. It is likely that a majority of the Ukrainian population watching this video would immediately know this announcement was false. The video was accompanied by text running at the bottom of the screen, providing the same message of a Ukrainian surrender51.

When the video is reconsidered almost three years later, it might seem this Russian disinformation attempt was clumsily executed. The poor video technical quality seemingly ensured that this material would never stoke the Ukrainian civilian population’s belief in the video as true. It is implausible that such an amateurish message would spread quickly enough to prompt Ukrainian armed units to halt their operations immediately (Allen 2022, n. 4, p. 65). One would also reasonably conclude that its Russian producers knew the video itself would not be a successful deepfake.

If an information or psychological operation does not qualify as an “attack” under international humanitarian law (IHL) because it lacks the element of violence, the question arises as to whether it might nonetheless constitute a “military operation” and therefore fall under certain IHL rules governing the conduct of hostilities. Additional Protocol I requires that parties “direct their operations only against military objectives” and stipulates that “[t]he civilian population and individual civilians shall enjoy general protection against dangers arising from military operations.” It further provides that “[i]n the conduct of military operations, constant care shall be taken to spare the civilian population, civilians and civilian objects.”52 The latter principle is widely accepted as customary IHL and thus applies to all parties to armed conflicts.53

If deepfake videos were invoked as a justification for launching an invasion, such a claim would clearly lack legal validity unless it were supported by an actual incident that meets the threshold of an armed attack. While deepfakes may serve as powerful instruments for shaping perceptions and influencing the psychological state of a targeted population, they cannot, in themselves, establish the factual grounds necessary to trigger the lawful exercise of self-defence. In this regard, their use is analogous to the fabrication of hostile acts in the past—for instance, the 1931 Mukden incident, orchestrated by the Japanese imperial army as a pretext for its occupation of Manchuria, similarly relied on a manufactured event rather than a genuine armed attack.54

If information or psychological operations were to be treated as “military operations” within the meaning of IHL, then the notion that non-violent psychological operations targeting civilians are lawful would be difficult to reconcile with Article 48 of Additional Protocol I, or at minimum, would require nuanced legal justification (Gisel et al. 2020). During the drafting of Additional Protocol I, the term military operations was generally understood to mean “any movements, manoeuvres and other activities whatsoever carried out by the armed forces with a view to combat” or otherwise “related to hostilities” (Bothe et al. 2013). According to the ICRC Commentary, this excludes “ideological, political or religious campaigns” (Sandoz et al. 1987). Based on this interpretation, some scholars contend that activities such as propaganda, espionage, or psychological operations fall outside the scope of hostilities or military operations and are therefore not subject to the principles of distinction, proportionality, or precaution—even when conducted by military forces (Droege 2012). In this view, while such actions may be undertaken by the armed forces, they do not meet the legal definition of military operations for the purposes of IHL.

Other commentators, however, propose a broader interpretation: communicative acts undertaken by armed forces with the aim of advancing military objectives could themselves be considered “military operations” under IHL (Dinstein 2016). Although this reading departs from traditional understandings, it aligns with the ordinary meaning of the term and the underlying object and purpose of the relevant rules. From this perspective, even non-violent information or psychological operations would still be bound by the obligation to exercise constant care to protect civilians.

This broader view is reflected, for example, in the U.S. Department of Defense Law of War Manual, which argues that the prohibition on directing military operations against civilians does not extend to non-violent operations deemed militarily necessary—including efforts to influence enemy civilian populations through propaganda.55 However, given the limited number of authoritative state and expert positions on this issue, it remains challenging to draw definitive conclusions about whether information or psychological operations are subject to IHL rules applicable to military operations short of attacks.

Some states appear to accept that targeting civilians with such operations is lawful, provided all other IHL obligations are observed. Yet this position is difficult to reconcile with fundamental IHL principles if such operations foreseeably place civilians at risk or cause them harm. It implies either that these activities do not qualify as “military operations” in the legal sense, or that principles such as distinction and constant care do not apply to them—both of which are contentious propositions if civilian safety is potentially compromised.

4.2. Deepfake Success by Sowing Doubts?

However, there is a suggested ‘real’ Russian tactical objective hidden in the poor quality, demonstrably ‘fake’ communication. Like any other psychological warfare form, an immediate Ukrainian government, military, or civilian response triggered by the deepfake message is not necessarily determinative of tactical success or failure. In effect, this February 2022 video was designed to plant seeds for future Ukrainian doubts about anything they saw or heard about the war. Doubt and its close cousin uncertainty are powerful, frequently destabilizing forces working on an enemy’s morale in any military campaign (Zerbe 2023).

If this Russian deepfake strategy was adopted at future points in this conflict, Ukrainian civilian audiences might legitimately reach the following conclusions: (1) at some later point (paraphrased) Will we receive other seemingly incredible information (e.g., ‘Ukraine has decided to surrender to Russia’) that is actually true; or (2), if Russia successfully transmits disinformation across Ukraine digital media platforms, can Ukraine counteract these deepfake threats (a possible drain on finite resources necessary to wage war) (Zerbe 2023, p. 65).

The above-cited research tends to confirm a core proposition: at a basic societal level, deepfakes tend to heighten public distrust and suspicion directed towards the ‘real’ media among their viewers (Twomey et al. 2023b, n. 137). When this specific point is taken to its own logical conclusion, an enemy wins the disinformation war simply by engaging in such tactics that fuel public doubts and uncertainty regarding all ultimate conflict outcomes. Further, absent any meaningful IHL enforcement mechanisms that take perfidy–deepfake prohibitions from theory to constructive practice, there is no meaningful international law prevention (Twomey et al. 2023b, n. 137). Deepfakes will seemingly persist unless and until they are banned, and such measures are robustly implemented across the international community. Non-state actors, including terrorist groups, insurgencies, and militias, have increasingly leveraged deepfake technology in modern conflicts. Their use of deepfakes presents unique challenges for IHL and the broader dynamics of warfare. Non-state actors use deepfakes to spread false narratives, manipulate public perception, and incite violence. This exacerbates conflict and complicates efforts to establish truth in war zones. The ability to create realistic but false videos of military leaders or humanitarian actors can sow distrust among forces, disrupt command structures, and erode morale. Non-state actors often operate beyond traditional legal frameworks, making the enforcement of IHL more difficult. The use of deepfakes further obfuscates attribution, enabling actors to deny responsibility for violations. The distortion of information through deepfakes can hinder humanitarian aid delivery by fabricating crises, impersonating aid workers, or misleading humanitarian agencies about battlefield conditions. The application of IHL to non-state actors remains complex, as they are not formal signatories to treaties like the Geneva Conventions. However, customary IHL applies to all parties in conflict, meaning non-state actors could still be held accountable for perfidious uses of deepfakes (Clapham 2006). Contemporary scholarship argues that non-State actors are thus “bound by IHL obligations commensurate with their capacity to implement them” (Sivakumaran 2012). Accordingly, when non-signatory groups employ deepfakes or other deceptive technologies in armed conflict, their conduct must still be assessed under the same IHL principles that prohibit perfidious acts and safeguard civilian trust.

The participation of non-state actors—as well as states operating beyond their own borders—in generating disinformation during armed conflict adds further complexity to the legal assessment. International human rights law (IHRL) is traditionally directed at sovereign states, and non-state entities are generally not recognized as primary duty-bearers under human rights treaties. Nevertheless, they remain bound by peremptory norms of international law (jus cogens), including fundamental rights such as the right to life.56 In addition, the United Nations has taken the view that non-state actors may fall under the scope of IHRL when they perform governmental functions or exercise de facto authority over territory or populations (Bellal 2016). Yet, the absence of a legal foundation for this position leaves the question of IHRL’s applicability to non-state actors unsettled. As a result, while such groups are obliged to respect jus cogens norms like the right to life regardless of context, the extent to which broader human rights obligations apply within areas under their control remains contested.

States, too, may engage in the dissemination of disinformation targeted at civilian audiences outside their own territory. Whether IHRL imposes limits on this conduct depends on how extraterritorial jurisdiction is conceptualized. International courts have generally adhered to the “effective control” and “personal jurisdiction” approaches, under which the applicability of human rights obligations to such activities would likely be excluded (Milanovic 2015). By contrast, some scholars have argued for alternative models, such as those based on the positive–negative rights distinction or on functional considerations (Shany 2013). These more expansive interpretations would provide a stronger basis for extending human rights protections to extraterritorial disinformation operations during armed conflict. However, they remain aspirational proposals (de lege ferenda) rather than established law.

Information operations in armed conflict are not confined to combatants. State officials, government agencies, and civilian institutions may also actively participate in producing and spreading false or misleading narratives. Likewise, private individuals and other non-state actors often play a significant role, sometimes even serving as the main source of disinformation, either independently or on behalf of parties to the conflict. In many recent conflicts, belligerents have organized so-called “troll farms,” “electronic armies,” or “web brigades” to flood the information space with false content (Golovchenko et al. 2018).

Under international humanitarian law (IHL), civilians and civilian objects enjoy special protection. Civilians are defined as those who are not members of the armed forces, while civilian objects are those that do not constitute military objectives (Henckaerts and Doswald-Beck 2005). However, this protected status is not absolute and may be lost if civilians directly participate in hostilities. According to widely accepted criteria, such participation involves three cumulative elements: (1) causing a certain level of harm, such as death, injury, or destruction; (2) establishing a direct causal connection between the act and that harm; and (3) performing the act in support of a party to the conflict—the so-called belligerent nexus.57

Although disinformation that endangers civilian lives or objects might meet the first and third criteria, it often fails to satisfy the direct causation requirement, except perhaps in cases of immediate psychological harm. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) interprets “direct causation” as requiring a close link to actual combat operations, not merely activities that sustain or contribute indirectly to the war effort.58 For example, spreading false information about essential resources such as water or electricity, even if it disrupts their supply, does not qualify as direct participation. Similarly, political propaganda—which in many respects resembles disinformation—is excluded. However, entities that engage in incitement may lose their civilian immunity and become lawful military targets. Whether disinformation is more comparable to propaganda, incitement, or neither will depend on the circumstances (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) 2000).

Even if certain disinformation activities could, in theory, be classified as direct participation in hostilities, targeting individual social media users through military means remains highly improbable. More realistic targets would be civilian infrastructure involved in disinformation campaigns, such as media outlets or government agencies. Yet, their protection would be suspended only for the specific periods during which they are directly engaged in such activities—moments that may be brief or sporadic. Moreover, IHL does not clearly define how long direct participation lasts in cases of repeated acts, such as frequent disinformation publishing (Schmitt 2013). Consequently, justifying military action against civilians or civilian objects on the basis of their involvement in disinformation presents significant legal challenges.

A rhetorical question reinforces the central problems now encountered in this ‘perfidy’ versus mere ‘ruse’ IHL sphere. The Russia–Ukraine war remains highly relevant for this specific discussion point. The UN Security Council is given ultimate international law authority to control how a particular armed conflict is conducted or resolved59. Security Council permanent member Russia has absolute veto power over numerous UN decision-making processes, including all binding UN sanctions and UN peacekeeping operations. It is beyond merely doubtful that Russia would ever willingly accept that its armed forces or government agencies have violated Additional Protocol I Article 37(1), or any other relevant IHL instrument. This UN Charter structure also influences how the Section 4 law reform recommendations are presented.

4.3. May 2023

This purported Russian president, Vladimir Putin, speech was broadcast across national media channels. Among other communications, ‘Putin’ announced a mass mobilization of Russian forces (DW 2023). The video was a deepfake; the Putin speech was never delivered, and the content was fabricated. Russian news media later determined that its platforms were hacked by foreign agencies (almost certainly Ukrainian actors, or parties that are committed to the Ukrainian side of this conflict (DW 2023)).

This deepfake was crafted to promote a subtler message than one conveying threats of invasion or civilian property destruction. There is significant evidence that the war is unpopular with the Russian population (Götz and Ekman 2024). The deepfake was communicated to sow doubt among Russians that the war being waged against Ukraine was going as well as the Russian government claimed. Once again, deepfake success here is not measured in terms of video production quality and its apparent credibility. If a significant Russian public demographic began to believe its forces were not winning, public appetite for a continued, costly Ukraine war would logically decline. Ukraine deepfake perpetrators (assuming this authorship is correct) would ‘win’ if their communication contributed to reduced Russian fighting resolve and a truce (or more permanent peace treaty (Götz and Ekman 2024)).

A further observation concerning this May 2023 disinformation initiative and the relevant Section 2 IHL perfidy legal frameworks merits further discussion attention. This Putin video did not violate Additional Protocol I Article 37(1) terms (ones concerned with an imminent armed attack or related military activity)60. Viewed from a Ukrainian perspective, any Russian population uncertainty or unease about the war’s direction might increase public resistance to joining the military (DW 2023).

4.4. May 2024—US State Department Video

In May 2024, the US Biden administration announced that Ukrainian forces could deploy US-made weapons in limited missile strikes inside Russian territory. A 49-second-long deepfake video of a U.S. State Department spokesperson (Matthew Miller) appearing to explain this policy appeared online on several international media platforms (Crowley 2024). The fabricated video was constructed from actual news conference footage, but its content went beyond mere editing (recalling the Section 1 perfidy–deepfake definitions). Miller speaks and suggests that Ukrainian forces could legitimately target Belgorod, a Russian city located approximately 40 km inside the Ukraine–Russia border (Crowley 2024).

American officials stated that they had no information concerning how the video was made or who had created it. The surrounding circumstances support a reasonable conclusion that only one of two possibilities exists. These are: (1) Russia created this material to “…manipulate opinion around the war in Ukraine or even American political discourse…” (Crowley 2024), or (2), US or Ukrainian agencies produced it to explain why the US arms missile deployment policy was valid (Crowley 2024).

The false Miller statements included the following apparent disinformation: (i) Belgorod “has essentially no civilians remaining”; (ii) Belgorod is “full of military targets at this point, and we are seeing the same thing starting in the regions around there” (thus purporting to justify military strikes by Ukraine); (iii) “Russia needs to get the message that this is unacceptable” (Crowley 2024). A further investigation revealed that Belgorod’s 340,000 residents had not been evacuated from the city (Crowley 2024).