Comparative Labor Law Studies in Indonesia and Malaysia: Social–Economic Inequality and Governance of Migrant Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Methods

4. Results & Findings

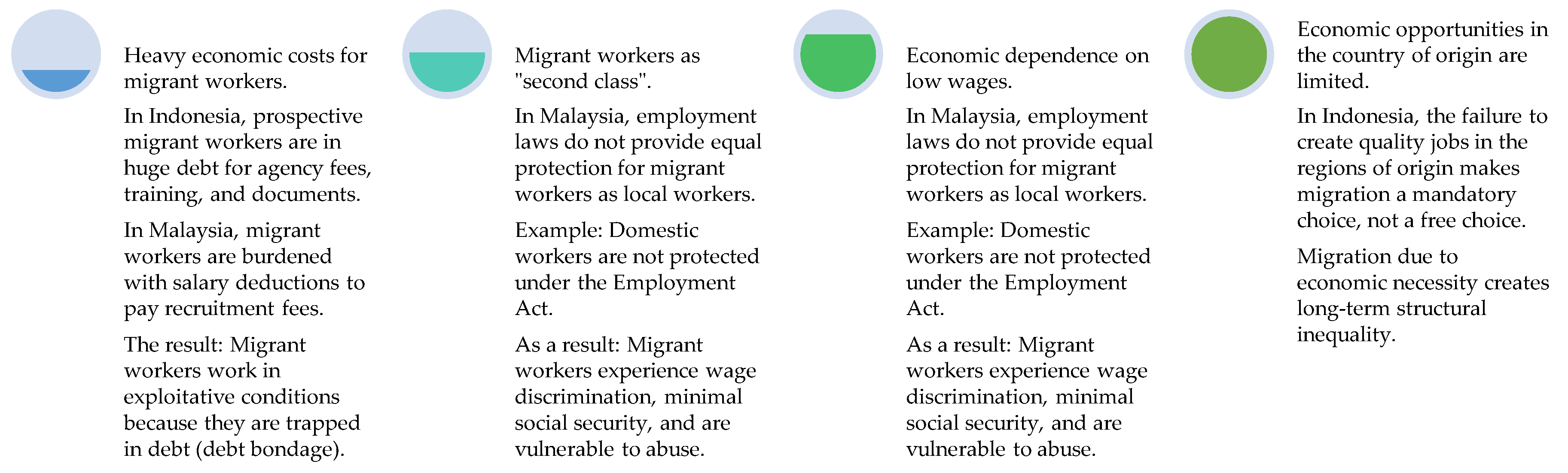

4.1. Structural Gaps and Impunity: Disparities in the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers (PMI) Amidst Fragmented Governance Between Indonesia and Malaysia

4.2. Comparative Law on Labor Law Against Social–Economic Inequality and Governance of Migrant Workers in Indonesia and Malaysia

5. Discussion

6. Implications of Theoretical, Practical, and Policy

7. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Countries | Problems/Existing Conditions | Formalizing the Informal Sector | Complying with International Labor Standards | Important Steps to Improve Labor Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indonesia | The decentralization of labor law enforcement in Indonesia has resulted in uneven law enforcement across regions, weakening overall worker compliance and protection (Harahap et al. 2024). Indonesia’s legal system also faces challenges in labor supervision, with weaknesses in substance, structure, and culture impacting the effectiveness of legal protection for workers (Pujiastuti and Purwanti 2018). In addition, the lengthy and convoluted judicial system further complicates the enforcement of workers’ rights (Musakhonovich et al. 2024). | The informal sector in Indonesia is quite large but neglected in economic and development policies, leading to persistent problems such as spatial uncertainty, financial constraints, and skills deficits (Zusmelia et al. 2019; Anggara 2025). Recent legislative reforms aim to include informal sector workers under legal protection, but practical implementation remains a challenge (Setiyono and Chalmers 2018). Institutional strengthening, such as providing space, financial support, and capacity building, is recommended to address these issues (Zusmelia et al. 2019). | There are inconsistencies between national labor laws and international standards (Mofea 2024). Indonesia has ratified several ILO conventions, but aligning domestic laws with these international standards remains a challenge (Mofea 2024). | Strengthen Enforcement (Harahap et al. 2024; Pujiastuti and Purwanti 2018). Formalize the Informal Sector (Zusmelia et al. 2019). Align with International Standards (Mofea 2024). |

| 2 | Malaysia | Malaysia’s centralized government, in particular, has struggled to protect migrant workers, highlighting the need for stronger law enforcement mechanisms (Harahap et al. 2024). Despite laws such as the Employment Act 1955, enforcement remains a challenge, especially in addressing issues such as sexual harassment (Taufiqurrohman et al. 2024). | In Malaysia, the high reliance on migrant workers suggests that formalizing employment practices could assist in better regulation and protection (Harahap et al. 2024). | Similar to Indonesia, Malaysia faces challenges in aligning its labor laws with international standards (Harahap et al. 2024; Taufiqurrohman et al. 2024). | Enhance Protection for Migrant Workers (Harahap et al. 2024). Improve Legal Framework (Taufiqurrohman et al. 2024). Strengthen Centralized Enforcement (Harahap et al. 2024). |

| No | Countries | Law | Issues Highlighted | Critical Policy Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indonesia | Law Number 39 of 2004 concerning the placement and protection of Indonesian workers abroad. | One of the main issues that stands out from Law No. 39 of 2004 is its focus which is considered to be heavier on the aspect of placement or sending workers business, rather than on the protection of workers themselves, which results in the vulnerability of Indonesian migrant workers to exploitation and human trafficking crimes, exacerbated by weak coordination between government agencies, minimal supervision and law enforcement against rogue PPTKIS, as well as limited coverage of protection, especially for domestic sector workers and undocumented (illegal) migrant workers. | This policy was indeed a significant milestone because, for the first time, it provided a clear legal basis for the protection of Indonesian migrant workers and structured the roles of the government and the private sector. However, its implementation in the field was often ineffective and actually opened up space for the dominance of profit-oriented private parties. As a result, worker protection was often neglected, and their welfare remained vulnerable. Normative weaknesses inconsistent with international standards ultimately led to legal reform through Law Number 18 of 2017. |

| Law Number 18 of 2017 concerning the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers. | Although aimed at strengthening protection, Law Number 18 of 2017 (the PPMI Law) still faces significant obstacles. The transfer of responsibility to local governments is often underfunded and understaffed, leading to delays in service delivery. Poor coordination between institutions, coupled with sectoral interests, weakens law enforcement against human trafficking and illegal placement. Meanwhile, many migrant workers, especially domestic workers, remain highly vulnerable to exploitation abroad. | Law No. 18 of 2017 marks a positive shift by embedding protection as the core principle of migration governance and broadening who qualifies as a migrant worker under state protection. Yet, its implementation suffers from slow regulatory harmonization, creating overlapping institutional roles and bureaucratic inefficiency. The persistence of high recruitment costs continues to trap workers in debt and exploitative conditions, undermining the law’s protective intent. In essence, the policy reflects strong normative progress but weak operational realization, leaving migrant welfare largely aspirational rather than guaranteed. | ||

| Government Regulation No. 59 of 2021 concerning the Implementation of Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers. | Government Regulation 59/2021 faces significant implementation challenges, particularly in ensuring the readiness and capacity of regional governments at the provincial and district/city levels to fulfill their mandated roles, including financing and administering training and competency certification. Furthermore, a central issue that remains unresolved is the effectiveness of the zero-cost policy, which is regulated in its implementation. Many prospective migrant workers are still burdened with high, unregistered fees (overcharging), as well as the classic problem of overlapping field coordination between agencies that is not yet fully digitally integrated. | Government Regulation 59/2021 represents a step forward by streamlining services through the LTSA system and enhancing migrant workers’ access to social protection programs. However, its implementation often burdens local governments that lack adequate administrative capacity and resources. The regulation also fails to address the persistent influence of brokers and illegal placement networks that exploit unregistered workers. Ultimately, while the policy improves formal structures, it remains limited in tackling the deeper systemic issues of migration governance. | ||

| Presidential Regulation No. 90 of 2019 concerning the Indonesian Migrant Workers Protection Agency. | One of the main issues with this regulation is a major clash between it and a higher-level law, specifically Law No. 18 of 2017. While the law outlines certain authorities for the Ministry of Manpower, this regulation seems to hand some of those very same responsibilities over to BP2MI. This creates a messy situation where legal certainty is up in the air, a problem that could be exploited. This bureaucratic confusion does not just exist on paper; it can also make the already difficult and lengthy process for migrant workers even more complicated, which unfortunately pushes some of them to bypass the official routes and use illegal channels, making them vulnerable to exploitation. | This regulation signifies a major institutional reform by placing migrant worker protection under BP2MI’s centralized authority and direct presidential supervision. Ideally, this structure should enhance coordination and create a unified national strategy for migrant protection. However, poor enforcement and limited control over illegal recruitment continue to undermine its goals. In practice, the regulation’s strong framework has yet to translate into tangible safety or justice for many vulnerable migrant workers. | ||

| Law No. 6 of 2023 concerning the Stipulation of Government Regulation in Lieu of Law Number 2 of 2022 concerning Job Creation into Law. | The most controversial part of Law No. 6 of 2023 lies in the labor cluster, where perceived erosion of workers’ rights has sparked protests and judicial reviews. Key concerns include broader use of fixed-term contracts and outsourcing, a simpler but less favorable wage formula, reduced severance pay, and termination rules seen as making layoffs easier for employers. | Law No. 6 of 2023 reflects the government’s ambition to streamline bureaucracy, attract investment, and stimulate job creation by simplifying overlapping regulations. Proponents view it as a breakthrough that enhances Indonesia’s global competitiveness and supports MSME development. Yet, the law’s deregulatory nature has raised serious concerns about weakened labor protections and growing employer dominance. Ultimately, it exposes a policy trade-off where economic efficiency may come at the expense of workers’ security and social justice. | ||

| 2 | Malaysia | Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Migrant Smuggling Act 2007 (Malaysia)/ATIPSOM 2007 | Enforcement of ATIPSOM 2007 faces gaps, with victims often treated as ‘illegal immigrants,’ risking re-victimization. Key challenges include the high burden of proof in labor trafficking cases, limited specialized training for frontline officers, and weak coordination among agencies handling investigation, prosecution, and victim protection. | The ATIPSOM Act marks significant progress by providing a dedicated and powerful legal framework to combat human trafficking with stricter penalties and a victim-centered approach aligned with global standards. However, its implementation often falls short, as victims are frequently misidentified and detained as offenders. This contradiction weakens the law’s core purpose of protection and discourages victims from seeking justice. Consequently, despite strong legislation, conviction rates remain low, revealing a deep gap between legal intent and practical enforcement. |

| Employees’ Social Security Act 1969 Malaysia/SOCSO Act 1969 or PERKESO Act 1969 | A major challenge in implementing the SOCSO Act is ensuring employer compliance, especially in the informal and SME sectors, leaving many workers unregistered and unprotected. Concerns have also been raised about the sustainability of the Invalidity Pension Scheme, as rising healthcare costs and payouts may outpace contributions, raising doubts about its long-term adequacy amid an aging population | The 1969 Act stands out for establishing a comprehensive social protection system that guarantees lifelong security through structured insurance and medical coverage for workers and their families. It has been instrumental in promoting social welfare and reducing financial vulnerability in cases of workplace injury or death. However, its exclusion of informal and self-employed workers has long left a significant portion of the labor force unprotected. Moreover, by barring employees from pursuing negligence claims, the Act arguably limits workers’ access to full legal justice in favor of administrative efficiency. | ||

| Employment Act 1955 (Malaysia) | The Act continues to face enforcement gaps, especially in protecting vulnerable groups such as domestic workers, gig workers, and migrants, who remain at risk of exploitation, passport retention, and forced labor. Employees earning above RM4,000 are also excluded from benefits like mandatory overtime pay, creating a tiered and uneven system of labor protection. | The Employment Act 1955 serves as a cornerstone of labor protection in Malaysia, ensuring minimum standards for fair treatment, paid leave, and regulated working hours. Its recent amendments have strengthened employee welfare and promoted a healthier work-life balance. However, the frequent updates and added obligations have placed growing pressure on employers, particularly small and medium enterprises. This tension highlights the policy challenge of balancing workers’ rights with business sustainability in a changing labor landscape. | ||

| Industrial Relations Act 1967 in Malaysia | A key challenge of the IRA 1967 is its slow and complex procedures, particularly in union recognition and unfair dismissal cases that can drag on for years through multiple stages of review. Although designed to protect workers, the Act is often criticized as overly formalistic, giving employers room to delay proceedings and weakening union efforts. | The Industrial Relations Act 1967 is pivotal in safeguarding workers from unfair dismissal by emphasizing fairness and equity through the Industrial Court. It offers employees a unique form of job security that goes beyond conventional legal frameworks. However, its stringent restrictions on union activity and the right to strike significantly limit workers’ collective power. As a result, while the Act strengthens individual protection, it simultaneously curtails broader labor freedom under tight government oversight. | ||

| Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994 (OSHA 1994) Malaysia | OSHA 1994 faces uneven compliance, especially among SMEs that often lack resources, expertise, or awareness to maintain proper Safety Management Systems. Enforcement is further hampered by limited staff and funding in the Department of Occupational Safety and Health, leaving a gap between the law’s strong framework and actual workplace safety, particularly in high-risk sectors like construction. | The Act represents a progressive shift toward self-regulation, encouraging employers to take active responsibility for identifying and managing workplace risks. By promoting participation through safety committees and empowering workers to refuse unsafe conditions, it fosters a stronger safety culture. However, this approach can overwhelm smaller businesses that lack the resources or expertise for full compliance. In practice, some employers may reduce safety to a box-ticking exercise, undermining the law’s preventive and participatory intent. | ||

| Workmen’s Compensation Act 1952 (WCA 1952) Malaysia | The main challenge with the WCA 1952 was its unequal protection for foreign workers, who received lower lump-sum payments that often excluded full medical or rehabilitation costs. This dual system left them vulnerable to abuse and highlighted clear disparities with Malaysian workers under SOCSO, leading to its eventual repeal and the inclusion of foreign workers in SOCSO’s Employment Injury Scheme. | The Workmen’s Compensation Act 1952 was a landmark in ensuring quick financial relief for injured workers by removing the need to prove employer negligence. Its strict liability framework offered a sense of certainty and efficiency compared to lengthy civil claims. However, the fixed lump-sum payments failed to account for long-term losses or emotional suffering, leaving many workers undercompensated. Over time, administrative inefficiencies and inconsistent enforcement highlighted the need for a more comprehensive system like SOCSO to fill these protection gaps. | ||

| Immigration Act 1959/63 Malaysia | A key challenge with the Act is its punitive approach, which criminalizes undocumented workers, refugees, and asylum seekers who lack legal status. Many face arrest, detention, or deportation—often linked to employer abuses like passport retention or contract breaches. Combined with broad enforcement powers, this fosters exploitation and discourages migrant workers from reporting crimes for fear of immediate detention. | The Act grants the government strong authority to regulate migration, protect borders, and address labor demands in the name of national security and economic stability. It establishes a clear framework for managing entry and deportation, reflecting a firm stance on immigration control. However, its harsh penalties for minor infractions blur the line between criminal and administrative offenses, violating basic human rights principles. This punitive approach not only fuels fear among migrant communities but also enables systemic exploitation and social exclusion. |

References

- Ab Hamid, Z., S. F. A. Shukor, and A. A. Ali Mohamed. 2018. Rights of migrant workers under Malaysian employment law. Journal of East Asia and International Law 11: 359. Available online: https://db.koreascholar.com/Article/Detail/361193 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alam, S., Z. H. Adnan, M. A. Baten, and S. Bag. 2021. Assessing vulnerability of informal floating workers in Bangladesh before and during COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-method analysis. Benchmarking: An International Journal 29: 1677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggara, R. 2025. Communicative adaptation of Indonesian migrant workers: A communication ethnographic study using Dell Hymes SPEAKING framework. Asian Anthropology 24: 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadullah, M. N. 2022. Inequality and public policy in Asia. Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia 56: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmorojati, A. W., M. Nur, I. K. Dewi, and H. Hashim. 2022. The impact of COVID-19 on challenges and protection practices of migrant workers’ rights. Bestuur 10: 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmawati, D., and N. Azzhara. 2022. The efforts of upt bp2mi nunukan, Indonesia, in protecting Indonesian migrant workers’ rights during COVID-19 outbreak. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Innovation on Humanities, Education, and Social Sciences (ICOSI-HESS 2022). Dordrecht: Atlantis Press, pp. 960–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, C. S., and W. Palmer. 2020. Indonesia and circular labor migration: Governance, remittances and multi-directional flows. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 29: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, T. 2010. Transnational private regulation in practice: The limits of forest and labor standards certification in Indonesia. Business and Politics 12: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosniak, L. S. 1991. Human rights, state sovereignty and the protection of undocumented migrants under the international migrant workers convention. The International Migration Review 25: 737–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BP2MI. 2022. Data Penempatan dan Pelindungan PMI. [Document]. Available online: https://www.bp2mi.go.id/uploads/statistik/images/data_20-03-2023_Laporan_Publikasi_Tahun_2022_-_FIX_.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Comola, M., and L. De Mello. 2011. How does decentralized minimum wage setting affect employment and informality? The case of Indonesia. Review of Income and Wealth 57: S79–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, H., B. Bhandari, and P. Adhikary. 2020. Perceived mental health, wellbeing and associated factors among Nepali migrant and non-migrant workers: A qualitative study. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, S., I. Islam, and A. Chowdhury. 2009. The Indonesian Labour Market: Changes and Challenges. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, J. 2013. Foreign policy and the domestic worker: The Malaysia–Indonesia domestic worker dispute. International Feminist Journal of Politics 15: 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathonah, R., H. Siswanto, and D. Harnova. 2024. Legal protection of children of migrant workers. Revista De Gestão Social E Ambiental 18: e08138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febriyanti, D., E. G. Putri, and S. Zubaidah. 2025. Enhancing online claims: Overcoming challenges in BPJS ketenagakerjaan’s digital transformation journey. Government & Resilience 3: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, O. 2021. The impact of micro and macro level factors on the working and living conditions of migrant care workers in Italy and Israel—A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitria, N. 2023. The urgency of human security in protecting the rights of migrant workers: A case study Indonesian migrant workers in malaysia and hong kong. International Journal of Engineering Business and Social Science 1: 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, L. J. 1994. The vulnerable and exploitable immigrant workforce and the need for strengthening worker protective legislation. Yale Law Journal 103: 2179–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C., K. Wee, and B. S. Yeoh. 2017. Migration governance and the migration industry in Asia: Moving domestic workers from Indonesia to Singapore. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 17: 401–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A. L. 1986. Methods of Comparative Labor Law in the United States. Comparative Labor Law 7: 319. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/cllpj7&div=27&id=&page= (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Grimmer, J., and B. M. Stewart. 2013. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis 21: 267–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, Y., L. Farman, L. Jayapraja, M. Taufik, and D. Irrynta. 2022. International law review on the exploitation and neglect of indonesian workers in malaysia. Wacana Hukum 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A. 2021a. A critical study of the job creation law no. 11 of 2020 and its implications for labor in Indonesia. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147–4478) 10: 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A. 2021b. The application of the rights and obligations of workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in Indonesia. International Journal of Business Ecosystem and Strategy (2687–2293) 3: 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A., and A. Intan. 2023. Labor law does not exist in a vacuum in the era of industrial revolution 4.0. Beijing Law Review 14: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A., M. Aldila, and A. Intan. 2022. The urgency of labor law for informal sector workers in the welfare state concept: An evidence in indonesia. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147–4478) 11: 528–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, A. M., R. Efendi, M. N. Daulay, and M. H. Ahmad. 2024. Challenges and problems in labour law from the perspectives of indonesia and malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Syariah and Law 12: 535–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennebry, J. L., N. Piper, H. KC, and K. Williams. 2022. Bilateral labor agreements as migration governance tools: An analysis from a gender lens. Theoretical Inquiries in Law 23: 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotho, J., and A. Saka-Helmhout. 2016. In and between societies: Reconnecting comparative institutionalism and organization theory. Organization Studies 38: 647–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R., J. P. Tan, T. A. Hamid, and A. Ashari. 2018. Cultural, demographic, socio-economic background and care relations in Malaysia. In Care Relations in Southeast Asia. Leiden: Brill, pp. 41–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, K., M. Fischer, R. Freiburghaus, D. Nohrstedt, and A. Vatter. 2025. How patterns of democracy impact policy processes: When lijphart and sabatier meet. European Policy Analysis 11: 254–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M., and F. Wiryani. 2020. Implication of principles in the International Convention on the protection of the rights of migrant workers and Members of their families in law no. In 2017, 18 of 2017, in an effort to protect Indonesian migrant workers abroad. Audito Comparative Law Journal (Aclj) 1: 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, K., N. M. Ngadiran, A. R. Ahmad, M. P. Halilintar, and S. D. Hasnati. 2019. Effect of job experience and job performance among indonesian workforce. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) 8: 465–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H., D. Hakim, and M. Hakim. 2021. The protection of indonesian migrant workers under fiqh siyasah dusturiyah. Lentera Hukum 8: 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istianah, I., and J. Imelda. 2020. The social protection rights from pre & post-placement women migrant workers perpective. Indonesian Journal of Social Work 4: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M. 2017. Institutional dynamics of regulatory actors in the recruitment of migrant workers. Asian Journal of Social Science 45: 440–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhlova, M. 2024. Informal employment in the world. World Eсonomy and International Relations 68: 130–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lapian, E., I. Nurhaeni, and M. Wijaya. 2021. Hegemonic project and the protection of migrant workers in Asean. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding 8: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., K. Yoshikawa, and A. Harzing. 2021. Cultures and institutions: Dispositional and contextual explanations for country-of-origin effects in mnc ‘ethnocentric’ staffing practices. Organization Studies 43: 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. 2024. The role of institutional logics in shaping sustainable talent management: A comparative study of two south korean conglomerates. Systems 12: 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, T., R. Deng, C. Ng, and N. Pocock. 2019. Breaking down the barriers: Understanding migrant workers’ access to healthcare in malaysia. PLoS ONE 14: e0218669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C. C. 2025. Contextualizing fair migration in Malaysia: From sovereign migration governance toward developmental global migration governance. Journal of Population and Social Studies [JPSS] 33: 261–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P., and M. Ruhs. 2019. Labour market realism and the global compacts on migration and refugees. International Migration 57: 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, L., A. Batnitzky, and S. Dyer. 2007. Division, segmentation, and interpellation: The embodied labors of migrant workers in a greater London hotel. Economic Geography 83: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. W. 2010. World society, institutional theories, and the actor. Annual Review of Sociology 36: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. W., R. Greenwood, and C. Oliver. 2017. Reflections on institutional theories of organizations. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 831–52. Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5018766#page=860 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Meyer, R. E., and M. A. Höllerer. 2014. Does institutional theory need redirecting? Journal of Management Studies 51: 1221–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2018. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mindarti, L., C. Saleh, and A. Maskur. 2021. Domestic stakeholders’ aspirations for mou renewal on women migrant workers in malaysia. Jurnal Studi Komunikasi (Indonesian Journal of Communications Studies) 5: 365–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofea, S. 2024. Inconsistencies in the reality of Employment Law in Indonesia in international legal conventions. Journal of Ecohumanism 3: 57–69. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1271882 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- MPR RI. 2023. Tindaka Pidana Perdagangan Orang, Negara Harus Hadir, dan melindungi Warga dari TPPO. [Document]. Available online: https://mpr.go.id/img/majalah/file/1687311127_file_mpr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Musakhonovich, M. M., E. A. Esirgapovich, A. K. Jaelani, W. M. K. F. W. Khairuldin, and R. D. Luthviati. 2024. The protection of labor rights on the court system. Journal of Human Rights, Culture and Legal System 4: 742–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, K. 2010. Governance of international migration: Mechanisms, processes, and institutions. Global Governance 16: 331. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/glogo16&div=31&id=&page= (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ngan, L. L. S., and K. W. Chan. 2013. An outsider is always an outsider: Migration, social policy and social exclusion in East Asia. Journal of Comparative Asian Development 12: 316–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A., I. Ronaboyd, E. Rusdiana, D. E. Prasetio, and S. Zulhuda. 2024. The impact of labor law reform on Indonesian workers: A comparative study after the Job Creation Law. Lex Scientia Law Review 8: 65–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oemar, H. 2020. Legal protection for foreign workers in Indonesia: Opportunities and challenges. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management 8: 1983–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paksi, A., and P. Renta. 2023. Indonesia’s pro-people foreign policy: The protection of indonesian women migrant workers in malaysia in 2022. Otoritas Jurnal Ilmu Pemerintahan 13: 203–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, N. 2022. Temporary labour migration in Asia: The transnationality-precarity nexus. International Migration 60: 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, N., and M. Withers. 2018. Forced transnationalism and temporary labour migration: Implications for understanding migrant rights. Identities 25: 558–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, N., S. Rosewarne, and M. Withers. 2017. Migrant precarity in Asia: ‘Networks of labour activism’ for a rights-based Governance of migration. Development and Change 48: 1089–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PP-TPPO. 2022. Laporan kinerja gugus tugas PP-TPPO 2015–2019. [Document]. Available online: https://aseanactpartnershiphub.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IN-NPA-Report-2015-2019-Bahasa.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Prianto, A., A. Amri, and M. Ajis. 2023. Governance and protection of indonesian migrant workers in Malaysia. Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights 7: 214–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujiastuti, E., and A. Purwanti. 2018. Labor supervision policy in Indonesian legal system based on Pancasila. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Bristol: IOP Publishing, vol. 175, p. 012192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revidy, A., and S. Mustofa. 2024. System maid online as violations of the mou on placement and protection of indonesian migrant workers in the domestic sector in malaysia 2022. Veteran Law Review 7: 174–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rother, S. 2017. Indonesian migrant domestic workers in transnational political spaces: Agency, gender roles and social class formation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43: 956–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhs, M. 2010. Migrant rights, immigration policy and human development. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 11: 259–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saefudin, A. 2024. National Identity in Transnational Life: The case of dual education of Indonesian migrant children in Sabah, East Malaysia. Kajian Malaysia 42: 117–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosa, I., A. Rokhman, A. Sabiq, and I. Y. Hutasuhut. 2024. Empowering undocumented indonesian migrant workers in sarawak through social capital enhancement. Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences 22: 12672–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, M., S. N. Chua, A. M. Radzi, Y. F. Kong, C. Chwa, A. Raffoul, N. Craddock, and S. B. Austin. 2024. Case Method Teaching, Strategic Storytelling, and Social Change: A Pilot Evaluation of an Online Course to Address Colourism in Malaysia. Pedagogy in Health Promotion 10: 222–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlunegger, M. C., M. Zumstein-Shaha, and R. Palm. 2024. Methodologic and data-analysis triangulation in case studies: A scoping review. Western Journal of Nursing Research 46: 611–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schotter, A., K. Meyer, and G. Wood. 2021. Organizational and comparative institutionalism in internationalhrm: Toward an integrative research agenda. Human Resource Management 60: 205–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiyono, B., and I. Chalmers. 2018. Labour protection policy in a third world economy: The case of Indonesia. Development and Society 47: 139–58. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/90020485 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sianturi, H. R. P., R. Anggara, T. Susanto, and F. Hariyanto. 2025. Migrant shot dead: Malaysia-Indonesia confrontation repeated? The Round Table 114: 205–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, K. 2012. Malaysia’s socio-economic transformation in historical perspective. International Journal of Business and General Management 1: 21–50. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/9840859.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Taniguchi, K. 2025. Understanding masahiko aoki’s comparative institutional analysis. Journal of Institutional Economics 21: e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taran, P. A. 2001. Human rights of migrants: Challenges of the new decade. International Migration 38: 7–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufiqurrohman, A. A., D. E. Wibowo, and O. Victoria. 2024. The regulation on sexual harassment in ASEAN workers: Evidence from several countries. Journal of Human Rights, Culture and Legal System 4: 538–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjitrawati, A. T., and M. K. Romadhona. 2024. Living beyond borders: The international legal framework to protecting rights to health of indonesian illegal migrant workers in malaysia. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 20: 227–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Migration. 2024. World Migration Report 2024. [Document]. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2024 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Van Ginneken, W. 2013. Social protection for migrant workers: National and international policy challenges. European Journal of Social Security 15: 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A. 2023. COVID-19 and the precarity of indonesian workers in the oil palm production in sabah, east malaysia. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 32: 475–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasekara, P. 2002. Asian Labour Migration: Issues and Challenges in an Era of Globalization. Geneva: ILO. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/asian-labour-migration-issues-and-challenges-era-globalization-0 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Wright, C. F. 2012. Immigration policy and market institutions in liberal market economies. Industrial Relations Journal 43: 110–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, S. G., and A. Ghimire. 2023. Migrant labour and inequalities in the Nepal–Malaysia corridor (and beyond). In The Palgrave Handbook of South–South Migration and Inequality. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 295–318. [Google Scholar]

- Zusmelia, Z., F. Firdaus, and A. Ansofino. 2019. Strengthening strategies of the informal sector in traditional market: An institutional approach. Academy of Strategic Management Journal 18: 1–10. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/journals/academy-of-strategic-management-journal-home.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurniati, Y.; Abdillah, A. Comparative Labor Law Studies in Indonesia and Malaysia: Social–Economic Inequality and Governance of Migrant Workers. Laws 2025, 14, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14060079

Kurniati Y, Abdillah A. Comparative Labor Law Studies in Indonesia and Malaysia: Social–Economic Inequality and Governance of Migrant Workers. Laws. 2025; 14(6):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14060079

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurniati, Yeti, and Abdillah Abdillah. 2025. "Comparative Labor Law Studies in Indonesia and Malaysia: Social–Economic Inequality and Governance of Migrant Workers" Laws 14, no. 6: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14060079

APA StyleKurniati, Y., & Abdillah, A. (2025). Comparative Labor Law Studies in Indonesia and Malaysia: Social–Economic Inequality and Governance of Migrant Workers. Laws, 14(6), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14060079