Abstract

This study explores the comparative employment laws related to migrant worker protection in Indonesia and Malaysia, with a focus on the socioeconomic inequalities faced by migrant workers in both countries. The study identifies key challenges in law enforcement, including migrant workers’ vulnerability to exploitation, poor recruitment procedures, and limited access to adequate legal education and information. A qualitative–interpretive methodology is used to explore in-depth issues related to employment laws and the socio-economic conditions of migrant workers. The study shows that Indonesia’s decentralized system results in fragmented and inconsistent law enforcement across regions, exacerbated by weak institutional capacity, legal gaps, and bureaucratic inefficiencies. Meanwhile, Malaysia’s centralized but pro-employer governance prioritizes economic growth over labor rights, leaving migrant workers—especially in the domestic and informal sectors—exposed to exploitation, wage discrimination, debt bondage, and limited access to social protection. To address these inequalities, bilateral cooperation between Indonesia and Malaysia is needed, including stronger law enforcement and equal protection for local and migrant workers. The study’s key finding is that these institutional weaknesses not only perpetuate migrant workers’ vulnerability, but also deepen structural socioeconomic inequalities between workers, agents, and employers. The study underscores the need for stronger law enforcement, formalization of the informal sector, harmonization with international labor conventions, and stronger bilateral cooperation. This study contributes to labor law studies and policy debates by offering insights into the institutional reforms necessary for more equitable and sustainable migrant worker governance in Southeast Asia.

1. Introduction

The emergence of a comparative institutional perspective, which highlights the interplay of political, social, and economic factors, has facilitated our understanding of how national contexts influence labor laws and policies (Meyer 2010; Meyer et al. 2017; Meyer and Höllerer 2014). Using this framework to analyze labor protection laws in Southeast Asian countries reveals significant variations in the methods used to protect migrant workers and address socioeconomic inequality and worker exploitation. For example, Indonesia still lacks a comprehensive framework to ensure similar worker protections, particularly in remote areas, while the Philippines has implemented the Kasambahay Law as legal protection for domestic workers (Elias 2013; Goh et al. 2017; Rother 2017; Bal and Palmer 2020). These trends highlight the ways in which socioeconomic circumstances and institutional arrangements influence the creation and effectiveness of labor laws. Comparative institutional theory emphasizes the importance of comparative analysis across social science disciplines, particularly political theory and public policy, by analyzing the interactions and changes between institutions over time. The primary goal of comparative institutional theory is to understand how different organizations and systems operate and change in different contexts. This theory highlights the importance of comparing these institutions to understand how they influence socioeconomic issues and governance (Lee 2024; Taniguchi 2025).

Comparative institutional theory in the context of labor migration provides a sophisticated framework for understanding how different institutional structures influence migration patterns and the experiences of migrant workers. According to this theory, governments, labor markets, and social networks are important institutions that influence the conditions of migration and the trajectory of migration (Wright 2012; Meyer 2010; Meyer et al. 2017; Meyer and Höllerer 2014). There is evidence that institutional arrangements significantly influence immigration control policies, affecting not only how migrants are processed but also the rights and protections afforded to them (Meyer et al. 2017). This framework emphasizes how economic conditions and institutional policies in countries of origin and destination create a conducive environment for migrant workers (Wright 2012; Meyer 2010; Meyer et al. 2017; Meyer and Höllerer 2014).

Currently, various strategies and frameworks have been implemented by various countries in efforts to protect and control labor migration at the global level (Newland 2010; Bal and Palmer 2020; Martin and Ruhs 2019; Piper et al. 2017; Meyer et al. 2017; Meyer and Höllerer 2014). This is evident in bilateral labor agreements (BLAs), which are crucial governance instruments that influence the working conditions of migrant workers, a key focus in several countries. Although some agreements support gender equality, Hennebry et al. (2022) examined various BLAs, which sometimes do not align their objectives with international standards for workers’ protection and rights. Furthermore, policy frameworks that do not prioritize the protection of migrant workers and their rights create precarious situations for workers, as Piper (2022) and Piper and Withers (2018) point out in the context of the intra-Asian labor migration system. This condition reflects a broader pattern in the governance of labor migration, which often prioritizes the interests of the state and industry as employers in mobilizing labor rights and the welfare of migrant workers.

The creation of a rights-based framework is a crucial component of efficient labor migration governance (Bal and Palmer 2020; Piper et al. 2017). Martin and Ruhs (2019) argue that, through programs such as employer accountability and no-fee migration agreements, countries’ moves toward equitable, development-based global migration governance are driving increased protection for migrant workers. The fundamental tensions in migration governance are also illustrated by research by Ruhs (2010), which shows how many guestworker programs often involve a trade-off between the number of migrants admitted and the rights granted. This emphasizes the importance of context-specific policies that maximize labor market demand while prioritizing the humane treatment of migrant workers. The Sustainable Development Goals, which promote safe working conditions and protect workers’ rights, align with this (Newland 2010; Bal and Palmer 2020; Martin and Ruhs 2019).

To address labor issues, Malaysia and Indonesia have implemented a number of legislative changes. The Malaysian Employment Act 1955 and the Indonesian Job Creation Act 6/2023 have significantly influenced labor policy. However, the implementation of these laws differs significantly. While Malaysia’s centralized system struggles to provide adequate protection for migrant workers, Indonesia’s decentralized approach has resulted in uneven implementation across the region (Harahap et al. 2024; Tjitrawati and Romadhona 2024). A more thorough examination of labor law governance in both countries is made possible by their differing legal and historical backgrounds. In both Malaysia and Indonesia, socioeconomic inequality is a recurring problem exacerbated by the treatment of migrant workers. There is a lack of adequate labor protection and wage disparities due to Indonesia’s widespread informal sector (Harahap et al. 2024). However, Malaysia’s heavy reliance on migrant labor creates a paradox where economic growth trumps labor rights, leaving migrant workers vulnerable, both socially and financially (Harahap et al. 2024; Santoso et al. 2024). To promote a fair labor market, this gap must be addressed.

Migrant worker management in Malaysia and Indonesia involves a complex interplay of international treaties, national laws, and legal frameworks. Both countries have attempted to protect migrant workers through bilateral agreements and legislative changes. For example, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Indonesia and Malaysia aims to improve conditions for migrant workers and ensure their rights are upheld (Low 2025; Prianto et al. 2023). However, because the implementation of these policies often fails, stronger enforcement mechanisms are needed (Harahap et al. 2024; Prianto et al. 2023; Hamid 2021a; Hamid and Intan 2023; Hamid et al. 2022).

Examining the laws governing migrant workers in Malaysia and Indonesia is crucial given the socioeconomic disparities faced by migrant workers in both countries. There are significant numbers of migrant workers in both countries, many of whom face poor working conditions, exploitation, and minimal legal protection. In Indonesia, decentralization has led to uneven enforcement of labor laws, exacerbating issues of wage inequality and the informal sector (Harahap et al. 2024). Malaysia still faces issues such as weak law enforcement, reliance on labor brokers, and the absence of a social security system, leaving many workers vulnerable to exploitation and abuse despite legislative changes aimed at improving migrant worker welfare (Low 2025; Ab Hamid et al. 2018). Undocumented migrant workers in Malaysia also face serious socioeconomic risks due to their lack of legal status, which prevents them from accessing social and legal protection (Santosa et al. 2024; Asmorojati et al. 2022; Hamid 2021b; Hamid and Intan 2023; Hamid et al. 2022).

Migrant workers’ rights have not been adequately protected through bilateral cooperation between Indonesia and Malaysia, including agreements such as the ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of Migrant Workers’ Rights (Asmorojati et al. 2022; Tjitrawati and Romadhona 2024). Addressing this disparity and ensuring fair treatment and protection for migrant workers requires a strong legal framework and an efficient law enforcement system (Harahap et al. 2024; Low 2025; Prianto et al. 2023; Sianturi et al. 2025).

Several important studies have revealed the challenges workers and migrants face in obtaining adequate protection and decent working conditions. Multiple interpellations occur in service-sector workplaces, reinforced and challenged by routine social practices and employee relations, as described by McDowell et al. (2007). According to Alam et al. (2021), social protection programs must be carefully considered and implemented to reduce workers’ vulnerability, especially during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbates job loss, food insecurity, housing instability, and threats to physical and mental health.

According to Fisher (2021), “migrant care workers” in Italy and Israel face similar challenges in securing decent employment, despite their countries having different immigration and employment laws. This results in power imbalances at the micro level, as domestic workers are routinely overworked, deprived of sleep, and subjected to various forms of violence. This suggests a lack of political will for long-term solutions on a larger scale. Tjitrawati and Romadhona (2024) note that Indonesian migrant workers in Malaysia, particularly those with irregular status, have limited access to healthcare in the Southeast Asian context. To provide healthcare regardless of legal status, they advocate for greater bilateral cooperation. Collectively, these studies suggest that despite efforts by Malaysia and Indonesia to promote good governance and legal protection for workers and migrants, significant barriers remain to be overcome in the implementation and enforcement of labor laws.

Current literature tends to emphasize how institutional interactions influence migrants’ experiences. For example, Istianah and Imelda argue that when discussing the need for comprehensive social protection rights for migrant workers, effective advocacy requires knowledge of the rights and obligations established by sending and receiving countries (Istianah and Imelda 2020). Furthermore, Gunawan et al. and Fathonah et al. highlight gaps in the legal framework that need to be addressed to improve migrant welfare by focusing on the difficulties migrant workers face, such as exploitation and legal protection (Gunawan et al. 2022; Fathonah et al. 2024).

Overall, findings from recent research in comparative institutional theory highlight the importance of institutional context in assessing the performance of migrant worker protection laws, including addressing socioeconomic disparities. While the specific reference to Lee (2024) is unwarranted, as it concerns talent management rather than migrant worker protection, it does support a robust framework that reflects these complex interrelationships. The rights of Indonesian migrant workers are also discussed by Ismail et al. (2021), although their focus is on undocumented workers rather than more general aspects of migrant protection. Consequently, this reference should also be ignored.

The purpose of this study is to examine in depth the comparative labor laws for migrant worker protection and address the institutional governance gaps, as discussed above, including highlighting some policy implications related to the formalization of the informal sector, strengthening law enforcement, compliance with international labor standards, and significant steps to improve protection and fairness for migrant workers in Malaysia and Indonesia. Furthermore, this study will discuss the legal and governance gaps in labor protection between Indonesia and Malaysia through a comparative institutional approach. The research question is: How do structural differences in labor migration governance between Indonesia (decentralized law enforcement) and Malaysia (centralized but pro-employer system) affect the consistency and effectiveness of migrant worker protection, and what institutional reforms are needed to reduce socioeconomic inequality and exploitation? This study also emphasizes the importance of addressing socioeconomic disparities and improving migrant worker governance through a comprehensive examination of labor laws in Malaysia and Indonesia. Ultimately, it is hoped that this research will provide conceptual, theoretical, and practical contributions by providing information that will help practitioners, academics, and policymakers create a more sustainable and equitable labor governance framework, particularly in Southeast Asia.

2. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework of institutional comparative theory focuses on understanding institutions as networks of structures, norms, and practices that influence social behavior and policy outcomes (Lee et al. 2021; Hotho and Saka-Helmhout 2016; Meyer et al. 2017). This framework comprises several interrelated components. Firstly, institutional logics are crucial in determining how organizations perceive their surroundings and make choices, which can differ significantly depending on the situation, offering insights into the variety of organizational behavior (Hotho and Saka-Helmhout 2016; Taniguchi 2025). Secondly, the concept of intra-institutional heterogeneity highlights how variations within the same institutional domain can lead to different practices among comparable organizations across various societies (Hotho and Saka-Helmhout 2016; Taniguchi 2025). This highlights the contextual nature of institutions, allowing scholars to explore the ways in which local circumstances impact institutional reactions and interactions.

Furthermore, because the development of institutions is closely linked to their historical legacies, historical context is essential to institutional comparative theory. It is easier to analyze current policies and practices when one is aware of the historical evolution of institutions (Taniguchi 2025; Hotho and Saka-Helmhout 2016). Furthermore, the framework takes into account the agency of social actors, arguing that people and organizations actively influence institutions through their deeds, enabling modifications to long-standing customs and norms (Ingold et al. 2025).

This conceptual framework can be successfully contextualized in the particular context of migrant worker protection. According to the literature, migrant workers frequently encounter serious institutional obstacles that differ depending on their country of origin and final destination. For instance, contend that the regulations that are in place to protect Indonesian female migrant workers are inadequate and do not specifically address their particular vulnerabilities (Ismail et al. 2021; Gunawan et al. 2022). This illustrates how institutional practices vary and how customized policies that take into account the various settings and customs affecting migrant workers are necessary.

Additionally, Karim (2017), emphasizes how institutional dynamics and regulatory actors govern the hiring of migrant workers, highlighting the significance of local institutional arrangements in determining how these workers are treated and protected. Lapian et al. (2021) address the impact of hegemonic projects on migrant worker protections in the ASEAN region, emphasizing the interaction between national practices and regional policies, indicating that different institutional dynamics determine the efficacy of migrant worker protections in various contexts. A strong lens for evaluating the efficacy of migrant worker protection laws is offered by the institutional comparative theory framework. Scholars can gain a better understanding of the obstacles and required reforms to enhance migrant worker protections worldwide by examining how institutions operate, change, and engage with social actors in diverse contexts. Additionally, Karim’s research emphasizes how institutional dynamics and regulatory actors govern the hiring of migrant workers, highlighting the significance of local institutional arrangements in determining how these workers are treated and protected (Karim 2017). Lapian et al. (2021) address the impact of hegemonic projects on migrant worker protections in the ASEAN region, emphasizing the interaction between national practices and regional policies, indicating that different institutional dynamics determine the efficacy of migrant worker protections in various contexts. A strong lens for evaluating the efficacy of migrant worker protection laws is offered by the institutional comparative theory framework. Scholars can gain a better understanding of the obstacles and required reforms to enhance migrant worker protections worldwide by examining how institutions operate, change, and engage with social actors in diverse contexts.

3. Methods

To assess the extent of existing research in this area, a targeted search was conducted in the Scopus database using the key strings: (“labor law” OR “employment law” OR “workplace regulation”) AND (“Indonesia” OR “Malaysia”) AND (“migrant worker” OR “foreign worker” OR “immigrant labor” OR “guest worker”) AND (“social inequality” OR “economic disparity” OR “income inequality” OR “wealth gap”) AND (“governance” OR “regulation” OR “management” OR “oversight”). A total of 57 pertinent documents published between 2005 and 2024 were found through this search. The comparatively small number of studies conducted over this almost two-decade period highlights the paucity of scholarly attention paid to the relationship between labor law, socioeconomic inequality, and migrant worker governance in Malaysia and Indonesia. By offering conceptual, theoretical, practical, and policy insights that can guide future research and help policymakers strengthen governance frameworks and protections for migrant workers, this study aims to close this gap.

This study employs a comparative labor law approach (Goldman 1986), utilizing the concept of comparative institutional analysis, to conduct a comprehensive comparison of different governance systems in Indonesia and Malaysia. It aims to identify the main limitations in previous labor law studies in the literature that have been developed on labor law, especially in Indonesia and Malaysia, so that it can build a new analytical framework. Focusing on institutional diversity and dynamics, the comparative institutionalism theory employed in this study highlights important factors like the type of institutional arrangements, decision-making procedures, the interplay between structure and agency, and the impact of historical context. In addition to aiding in the analysis of intricate social phenomena, this framework makes it easier to compare how various institutional arrangements influence results in various fields (Lee et al. 2021; Schotter et al. 2021; Hotho and Saka-Helmhout 2016). Goldman (1986) stated that the methodology of comparative labor law studies is intended to adapt to the problem of legal gaps while providing legal solutions from various similar cases in various countries, to overcome domestic problems, such as the protection of individual workers or worker participation.

In this study, research methods can be used in the legal field to answer research questions, by collecting and analyzing relevant documents such as migrant worker law policies, laws and regulations, and reports related to the implementation and enforcement of migrant worker law in Indonesia and Malaysia (data obtained from: JDIH Indonesia Portal: link https://jdihn.go.id/ (accessed on 1 September 2025) and Official Portal of the Parliament of Malaysia: link https://www.agc.gov.my/ (accessed on 1 September 2025) and https://www.parlimen.gov.my/) (accessed on 1 September 2025). In addition, we use the Scopus database to collect various literature by exploring previous studies on employment law in Indonesia and Malaysia. The search and filtering of data in this study refers to several criteria such as: (1) Authenticity; (2) Credibility; (3) Representativeness; (4) Purpose of the Document; (5) Relevance; (6) Time and Context; (7) Completeness; and (8) Document Usage Ethics. These documents will be analyzed to determine the main factors that are obstacles to the implementation and enforcement of labor laws to improve the protection and governance of migrant workers to overcome the socioeconomic disparities of migrant workers in the future.

Comprehensive study analysis and content analysis methods (Krippendorff 2018; Grimmer and Stewart 2013) are used in this study, where this method compares the legal systems of various existing regulations from two countries chosen for their uniqueness in the case of immigrant workers, namely Indonesia and Malaysia. Data on employment law policies, laws and regulations, and migrant worker law enforcement practices will be collected from each country and then compared (by conducting documentation studies, online research methods, and policy surveys at the head of the country). The steps of data analysis in this study refer to the qualitative data analysis of Miles et al. (2018), which conducts data identification, data collection, data reduction, data classification, data display, and data visualization, to conclude. At this stage, we begin by selecting authentic, credible, and relevant documents, then reading them in depth to identify important themes or patterns. Next, the coding process and thematic or discourse analysis are carried out to understand the meaning and context of the document’s contents. The results are interpreted critically and can be triangulated with other data to strengthen the validity of the findings.

To maintain the validity of the data in this research, researchers carried out data triangulation techniques (Schlunegger et al. 2024), by comparing and re-checking the research data collected from various sources, method triangulation by using several data collection methods to test the validity of the data, investigator triangulation by reducing the subjectivity of a single researcher, and also theory triangulation by using several different theoretical perspectives to interpret the data, to increase the validity of the research data.

4. Results & Findings

4.1. Structural Gaps and Impunity: Disparities in the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers (PMI) Amidst Fragmented Governance Between Indonesia and Malaysia

The World Migration Report 2020 reported that in 2019, around 272 million people migrated abroad, with around two-thirds of them moving to find work. Indonesia is the only Southeast Asian country that is home to a large number of migrants. Indonesia is an important country that sends a lot of labor to Southeast Asia. The report shows that as of 2019, around 3.7 million Indonesians were working abroad. The increase in the number of foreign workers choosing to work abroad may be due to the wage gap between job offers in other countries, which is much larger than in Indonesia (Prianto et al. 2023).

The dynamics between sending and receiving countries are influenced by the difference in GDP per capita between Indonesia and Malaysia. Since Malaysia’s GDP per capita is about three and a half times higher than Indonesia’s, workers from Indonesia prefer to move to Malaysia (Prianto et al. 2023). As a result, the flow of migrant workers always depends on the demand and supply of workers in both countries, which causes various problems in both countries. As a result, there is a demand for workers from the destination country, as well as low wages and high unemployment rates in the country of origin (see Table A1).

Indonesia continues to move towards primary products, but Malaysian manufacturing, with a focus on technology, has advanced since the early 1990s. Therefore, Malaysia has attracted many foreign workers. Indonesia sent the most workers to Malaysia in 2022, amounting to 1.67 million people, which is 48.13% of Indonesia’s 3.44 million migrant workers (Prianto et al. 2023). To understand the policy imperatives of strengthening law enforcement mechanisms, formalizing the informal sector, and complying with international labor standards in Indonesia and Malaysia, a comparative study of labor laws in both countries provides several insights, as shown in Table A1.

Table A1 shows that employment laws in Indonesia and Malaysia play an important role in regulating the rights and obligations of migrant workers, but their implementation still reflects quite sharp socioeconomic disparities (Yeoh and Ghimire 2023; Ibrahim et al. 2018; Asadullah 2022). In Indonesia, although there is Law No. 18 of 2017 concerning the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers, the reality on the ground is that most migrant workers come from low-income families who have limited access to adequate education and legal information. This social inequality is exacerbated by poor recruitment governance, the continued prevalence of brokers, and illegal placement practices that trap workers in large debts before leaving (Wickramasekara 2002; Sianturi et al. 2025). Legal protection tends to be weak for undocumented (non-procedural) migrant workers, whose numbers are significant, making them increasingly vulnerable to exploitation, violence, and low wages in the destination country (Yeoh and Ghimire 2023; Ibrahim et al. 2018; Asadullah 2022; Prianto et al. 2023). In addition, Law No. 6 of 2023 tries to provide flexibility for companies to recruit and manage workers. However, this also brings major challenges in protecting workers’ rights, especially related to job security, severance pay, and minimum wages. If not balanced with strict regulations and good supervision, this law could worsen job uncertainty and worker welfare in Indonesia.

In Malaysia, despite the Employment Act 1955, the Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants Act 2007, and several other regulations governing migrant workers, social and economic protection for foreign workers is still far from ideal (Yeoh and Ghimire 2023; Ibrahim et al. 2018; Asadullah 2022). The foreign labor management system in Malaysia tends to position migrant workers as cheap labor with limited access to social security, association rights, and legal protections equal to local workers. In addition, the agency-based recruitment system in Malaysia, which involves high costs, often creates a situation of debt bondage among migrants. Malaysia’s failure to integrate migrant worker protection policies into national economic development policies shows that the socioeconomic disparities faced by migrant workers in Malaysia are not only due to weak laws, but also due to immature labor migration governance that is rife with political economic interests (Yeoh and Ghimire 2023; Ibrahim et al. 2018; Asadullah 2022; Prianto et al. 2023). This comparative study highlights the need for both countries to strengthen law enforcement mechanisms, formalize the informal sector, and ensure compliance with international labor standards to improve labor conditions.

Based on the 2022 report by the Indonesian Human Trafficking Commission (PP-TPPO 2022; MPR RI 2023; UN Migration 2024) and the 2023 report on systemic and uneven law enforcement in the migrant worker migration chain, both in the country of origin (Indonesia) and the destination country (Malaysia), empirical data shows a striking disparity between the volume of violations/victims and legal action against perpetrators. In Indonesia, proxy statistics indicate a failure of law enforcement in areas of origin, indicated by the concentration of migrant worker trafficking victims (up to 37.1%) in West Java and the high number of cases disproportionate to the number of criminal convictions for perpetrators. Meanwhile, a report from BP2MI (2022) stated that in Malaysia, the unevenness of law enforcement is seen in the unequal focus of enforcement, where Malaysia recorded thousands of deportation cases (2036 people from January–October 2024 via Kepri) against illegal migrant workers, while complaints of exploitation and unpaid wages from migrant workers are among the highest, but legal action against rogue employers or agents is reported to be non-transparent and disproportionate, indicating that migrant workers are vulnerable subjects to punishment in the destination country, while perpetrators in the country of origin (Indonesia) and the destination country (Malaysia) are relatively immune from the law.

Both Indonesia and Malaysia struggle with protecting workers, mainly in law enforcement, the informal sector, and compliance with international standards. In Indonesia, decentralization causes uneven enforcement across regions, worsened by weak institutions, legal gaps, and a complicated judicial system that limits workers’ rights protection. The informal sector is large but still overlooked in development policies, and efforts to extend legal protection face implementation challenges. Indonesia also has not fully aligned its laws with ILO standards, especially on wages, severance pay, and migrant worker rights. In Malaysia, despite having the Employment Act 1955, enforcement remains weak, particularly in safeguarding migrant workers and tackling workplace harassment. Heavy reliance on migrant labor further underscores the need to formalize labor practices for stronger regulation. Overall, both countries must improve institutional capacity, update legal frameworks, and harmonize domestic laws with international standards to ensure more effective and sustainable worker protection.

4.2. Comparative Law on Labor Law Against Social–Economic Inequality and Governance of Migrant Workers in Indonesia and Malaysia

In the context of labor migration, Indonesia, as a sending country, and Malaysia, as a receiving country, face major challenges in creating fair and sustainable governance for migrant workers. Labor laws in both countries play an important role in determining how migrant workers’ rights are recognized and protected. However, behind the existence of various legal regulations, there is still a gap between the promised legal protection and the reality faced by migrant workers in the field (Yeoh and Ghimire 2023; Ibrahim et al. 2018; Asadullah 2022; Prianto et al. 2023). The imbalance of power between migrant workers, recruitment agents, employers, and the government has exacerbated the socioeconomic injustice experienced by migrants. A comparative study of labor laws in Indonesia and Malaysia revealed that decentralization in Indonesia has resulted in uneven law enforcement across regions, while centralized administration in Malaysia has failed to protect migrant workers (Harahap et al. 2024; Siddiqui 2012; Revidy and Mustofa 2024). This can be seen in the differences in labor laws in Indonesia and Malaysia in Table A2 below.

Migrant worker laws and regulations in Indonesia and Malaysia show that the governance of labor migration in both countries is still immature. The presence of Law No. 6 of 2023 provides wide room for socioeconomic injustice in Indonesia. In the context of migrant labor in Indonesia, although there is Law No. 18 of 2017 concerning the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers, its implementation is still weak, especially in the supervision of the recruitment process and protection of workers abroad. Many prospective migrant workers are forced to bear high recruitment costs, owe debts to agents or loan sharks, and face non-transparent job information. On the other hand, Indonesian migrant workers in Malaysia are often placed in high-risk sectors with low wages and minimal legal protection, especially domestic workers whose rights are not fully guaranteed in the Malaysian Employment Act 1955. This situation exacerbates the economic inequality between migrant workers and employers or companies that enjoy cheap labor.

In Malaysia, despite the existence of legal frameworks such as the Immigration Act 1959/63 and the Employment Act 1955, these laws focus more on controlling migration than protecting the rights of migrant workers. Migrants are often treated as second-class workers who do not have access to adequate social security, such as occupational health and safety protection on par with local workers. Non-transparent and fee-laden recruitment governance also creates a chain of exploitation, where migrants must pay high prices just to get a job, while their wages are kept as low as possible. The weak coordination between the sending (Indonesia) and receiving (Malaysia) governments, as well as the dominance of private employment agencies, creates a structurally unfair migration system, deepening the economic gap between migrants, agents, and employers. As a result, labor migration, which should be a path to improving welfare, actually reinforces the cycle of poverty and injustice.

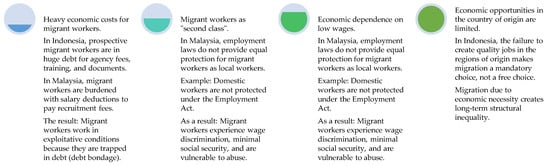

A presentation of the existing conditions of migrant workers in Indonesia and Malaysia is shown in Table A1. The urgency of protecting migrant workers through effective governance and policy and legal interventions stems from the vulnerabilities faced by migrant workers in both Indonesia and Malaysia. First, they bear heavy economic costs, ranging from large debts incurred during the departure process in Indonesia to prolonged wage deductions in Malaysia, trapping them in debt bonds. Second, migrant workers are treated as “second-class” because labor regulations do not provide equal protection to local workers, leaving them vulnerable to wage discrimination, minimal social security, and violence. Third, this situation is exacerbated by the dependence on cheap labor, the economic foundation of destination countries. Fourth, the limited availability of quality jobs in their regions of origin, particularly in Indonesia, drives migration as a necessity rather than a free choice, thus perpetuating long-term structural inequalities.

Based on Figure 1, a comparative study of labor laws in Indonesia and Malaysia revealed that decentralization in Indonesia led to uneven enforcement across regions, while centralized administration in Malaysia failed to protect migrant workers (Harahap et al. 2024). Both Indonesia and Malaysia struggle with various problems related to the informal sector. Indonesia faces various challenges such as a long and complicated judicial system mechanism and differences between theoretical regulations and practical implementation, while Malaysia has a high dependence on migrant workers, especially in domestic sectors such as construction and plantations (Harahap et al. 2024; Isa et al. 2019; Nugroho et al. 2024). The informal sector in Indonesia is characterized by widespread and growing informality, which creates difficulties in developing and resolving problems that originate from formal legal aspects, such as spatial uncertainty, financial constraints, and skill constraints (Zusmelia et al. 2019; Khokhlova 2024).

Figure 1.

Socioeconomic injustice due to immature governance in Indonesia and Malaysia. Source: Processed by the regulation of Indonesia and Malaysia regarding migrant workers, 2025.

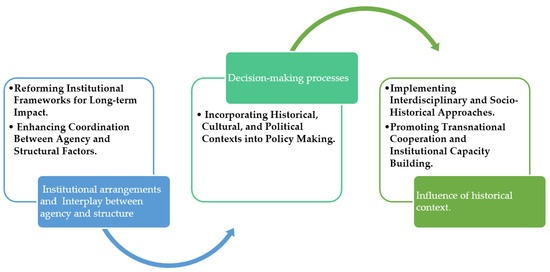

Based on empirical findings that have been linked to comparative institutionalism theory, it is stated that there are differences between Indonesia and Malaysia in terms of the design and implementation of governance structures regarding migrant workers, the cases of Indonesia and Malaysia reveal why migrant workers experience various forms of socioeconomic inequality (See Figure 2). Malaysia frequently imposes stringent immigration controls while providing sporadic, erratic, and short-lived amnesty programs due to its centralized and pro-employer labor governance. These institutional arrangements are a reflection of Malaysia’s state-corporatist model, which prioritizes business interests and economic efficiency over labor rights, particularly for migrants (Piper 2022; Bal and Palmer 2020).

Figure 2.

Comparative institutionalism and migrant workers in Indonesia dan Malaysia. Source: Processed by authors, 2025.

Figure 2 shows how comparative institutionalism can explore new strategies to address socioeconomic challenges faced by migrant workers in Indonesia and Malaysia: (1) A more stable and fairer environment for migrant workers can be achieved by fortifying and harmonizing institutional frameworks, such as governance, policy, and legal arrangements. Instead of focusing on discrete policy fixes, these reforms ought to address systemic inefficiencies such as bureaucratic fragmentation and decentralization problems; (2) Understanding the relationship between ingrained institutional structures and individual and collective agency is essential to addressing socioeconomic disparities. Regional disparities and exploitation can be decreased by enabling local officials and agencies to better enforce protections through improved coordination within sectors and across governmental levels; (3) Recognizing the influence of historical legacies, political will, and cultural attitudes allows for the design of policies that are context-specific and more effective. Tailoring interventions to these factors can help overcome systemic resistance and foster sustainable institutional change; (4) The underlying causes of socioeconomic inequality among migrant workers can be more accurately identified with a comprehensive approach that incorporates legal, political, economic, and cultural analysis. These tactics make it possible to create comprehensive reforms that address both official laws and unofficial practices; and (5) Institutional arrangements across borders can be aligned by updating international standards and fortifying bilateral agreements such as memorandums of understanding (MoUs). This addresses structural vulnerabilities at the regional level by promoting more uniform and enforceable protections when combined with capacity-building programs.

Based on research findings, referring again to the framework of comparative institutionalism theory, it shows that differences in institutional structures and actor dynamics significantly influence the effectiveness of migrant worker protection in Indonesia and Malaysia. In Indonesia, the history of post-reform decentralization gave birth to legal frameworks such as Law No. 39/2004 and Law No. 18/2017, whose normative orientation is oriented towards protection, but their implementation is fragmented due to unclear authority, weak regional capacity, and the dominance of private placement agencies. The interplay between these layered legal structures and the agency of local actors—both local governments and PPTKIS—often creates legal loopholes that leave workers vulnerable to exploitation. In contrast, Malaysia, with its model of legal centralization through the Employment Act 1955, Immigration Act 1959/63, and ATIPSOM 2007, emphasizes strong state control but favors economic efficiency and employer interests. This strict legal structure combined with the practices of migration agencies and business interests results in unequal power relations, in which migrant workers are often positioned as second-class. Historically, colonialism in both countries left a legal legacy oriented toward labor market interests, not worker welfare. This demonstrates that both Indonesia’s decentralization and Malaysia’s centralization have failed to provide effective protection because existing legal structures remain driven by dominant political–economic interests, rather than by principles of social justice.

Indonesia is a country that sends workers abroad, but it has problems with weak institutional capacity and fragmented governance, especially between the national and local levels. Laws like Law No. 18/2017 have been passed to protect migrant workers, but they have not been put into effect because of problems with the bureaucracy and lack of coordination. The way that labor laws and amnesty policies work together in both countries makes the socioeconomic gap that migrant workers face even bigger. Comparative institutionalism stresses that these outcomes are not random, but rather the result of deeply rooted institutional structures that affect how laws are made, enforced, and understood. The theory says that improving the governance of migrant workers requires not only changing certain policies but also looking at the bigger picture of how institutions work (Martin and Ruhs 2019; Piper et al. 2017; Meyer et al. 2017; Meyer and Höllerer 2014).

It shows in a critical way how Malaysia’s selective amnesty policies and pro-growth, low-rights labor regime create two separate labor markets that keep socioeconomic differences between migrant workers. On the other hand, Indonesia’s fragmented government and weak institutions make it hard to consistently enforce protections for migrants. This study shows how different types of governance work together to affect labor outcomes, which highlights the importance of institutional complementarity. However, one criticism of this strategy is that it might oversimplify complex sociopolitical factors that also have a big effect on the experiences of workers and law enforcement, like cultural attitudes and bureaucratic practices. The study talks about these things, but institutional change theory could be used to look at them more closely.

The application of comparative institutionalism from an innovative interpretive perspective demonstrates that improving migrant worker protections over the long term requires addressing the larger institutional contexts rather than just changing specific laws. The results of the study show that when it comes to migrant governance, Malaysia’s state-corporatist model and Indonesia’s decentralized governance represent distinct strategies that produce different results. This point of view holds that in addition to harmonizing current laws, effective policies must alter the institutional logics that support inequality, such as the incentives for law enforcement, political will, and economic priorities. The study urges policymakers to consider institutional dynamics and the cultural underpinnings that influence enforcement and compliance within each country’s unique governance framework, ultimately arguing that systemic change is more significant than discrete legal reforms.

5. Discussion

Structural differences in labor migration governance between Indonesia (decentralized law enforcement) and Malaysia (a centralized but pro-employer system) affect the consistency and effectiveness of migrant worker protection, and the institutional reforms needed to reduce socioeconomic inequality and exploitation. Therefore, Indonesia and Malaysia are expected to comply with international labor standards, as set by the International Labor Organization (ILO). However, there are inconsistencies and gaps between national and international labor regulations in both countries (Newland 2010; Bal and Palmer 2020; Martin and Ruhs 2019; Piper et al. 2017; Meyer et al. 2017; Meyer and Höllerer 2014). For example, provisions in national labor laws may not align with international standards ratified by Indonesia, such as those relating to minimum wages, severance pay, outsourcing, and protection for migrant workers (Mofea 2024). We find that the growth of informality in the Indonesian labor market can be attributed to the sharp increase in the real value of the minimum wage since 2001, when minimum wage setting was decentralized to provincial governments (Comola and De Mello 2011). Malaysia’s labor and migrant law is not far behind, as can be seen in the Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants Act 2007 (Malaysia)/ATIPSOM 2007, the Immigration Act 1959/63 of Malaysia, and the Employment Act 1955 (Malaysia), which state that they protect the human rights of foreign workers in cases of exploitation and also do not effectively address the root causes of human smuggling. Therefore, a key finding of this study based on both countries is the need to improve institutional capacity, update the legal framework, and align domestic legislation with international standards to ensure more effective and sustainable worker protection.

We argue that institutional strategies to address the disproportionate economic burden on migrant workers in Indonesia and Malaysia should focus on eliminating illegal recruitment fees and enforcing contract transparency. In Indonesia, this means strictly monitoring recruitment agencies and punishing excessive debt collection practices from prospective workers, while promoting fair financing schemes. In Malaysia, regulatory agencies should actively inspect workplaces and enforce minimum wage laws to prevent illegal deductions and wage withholding practices. Key to success is bilateral collaboration to establish a single, fair, and transparent fee structure monitored by both governments, effectively breaking the cycle of debt and exploitation. Strengthening bilateral cooperation and harmonizing labor laws between Indonesia and Malaysia will increase legal consistency, reduce exploitation, and create fairer protection mechanisms.

Furthermore, as previously explained, compliance with international labor standards in Indonesia and Malaysia is often hampered by significant institutional weaknesses. These include inadequate monitoring and enforcement capacity by under-resourced labor inspectorates, slow and expensive judicial processes that hinder workers’ access to justice, and problems with corruption and poor inter-agency coordination. Consequently, while strong legal protections may exist on paper, these weaknesses render the laws ineffective in practice, allowing violations to persist and reducing incentives for companies to comply with international standards.

Based on the results and findings presented previously, the urgency of protecting migrant workers through effective governance, policies, and legal interventions is due to the increasing vulnerability caused by legal gaps and labor exploitation faced by migrant workers, both in Indonesia and Malaysia (Harahap et al. 2024; Isa et al. 2019; Nugroho et al. 2024; Zusmelia et al. 2019; Khokhlova 2024). This is evident: First, they (migrant workers) bear heavy economic costs, ranging from large debts incurred during the departure process in Indonesia to prolonged wage deductions in Malaysia, which trap them in debt bondage. Second, migrant workers are treated as “second class” because labor regulations do not provide equal protection to local workers, thus making them vulnerable to wage discrimination, minimal social security, and violence. Third, this situation is exacerbated by dependence on cheap labor, the economic foundation of destination countries. Fourth, the limited availability of quality jobs in their home regions, particularly in Indonesia, encourages migration as a necessity rather than a free choice, thus perpetuating long-term structural inequality.

Several previous studies have argued that a comparison of labor laws in Indonesia and Malaysia outlines policy implications that support strengthening law enforcement mechanisms, formalizing the informal sector, and complying with international labor standards to promote good labor practices (Harahap et al. 2024; Low 2025; Prianto et al. 2023; Santosa et al. 2024; Asmorojati et al. 2022; Ab Hamid et al. 2018). Based on this, we argue that new policies and programs are needed to protect workers’ rights, promote decent work, and provide greater access to social protection in Indonesia and other low- and middle-income countries. In addition, there is a need for reform of labor laws in Indonesia and Malaysia as a positive step in strengthening legal protection against unfair termination of employment, while many workers still experience inequality in access to health insurance, pensions, and work accident insurance (Isa et al. 2019; Nugroho et al. 2024; Febriyanti et al. 2025).

The discourse surrounding labor laws relating to migrant workers in Indonesia and Malaysia has evolved significantly in recent years, reflecting the challenges and efforts of both countries to improve worker protection amidst globalization and labor market dynamics. A synthesis of recent studies reveals various dimensions in this area, ranging from the legal framework and enforcement of the right to access healthcare and the implications of international agreements. First, the regulatory framework governing Indonesian migrant workers (PMI) is prominently shaped by Law No. 18 of 2017, which seeks to uphold their rights, including safe working conditions and fair wages. This law aligns with international conventions such as the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, which Indonesia ratified in 2012 (Azmawati and Azzhara 2022; Iqbal and Wiryani 2020). However, despite this legal framework, its enforcement remains uncertain; many migrant workers experience serious rights violations due to inadequate oversight and exploitative practices, particularly within Malaysia’s labor infrastructure (Fitria 2023; Saefudin 2024). This situation is exacerbated by non-compliance with the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Indonesia and Malaysia, which fails to provide adequate protection, particularly for undocumented workers (Paksi and Renta 2023; Saefudin 2024).

Several previous studies have also highlighted that economic constraints and inadequate access to healthcare significantly impact the well-being of migrant workers. For example, research has documented employers’ reluctance in Malaysia to cover healthcare costs, forcing migrant workers to resort to expensive private healthcare options, leaving many uninsured or hesitant to seek medical attention (Loganathan et al. 2019). This includes documentation of the mental health implications stemming from isolation, long working hours, and lack of access to necessary services (Devkota et al. 2020). Furthermore, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed pre-existing vulnerabilities, exposing gaps in protection and increasing the risk of exploitation (Wahab 2023; Asmorojati et al. 2022). Migration patterns and regulatory challenges are further complicated by the Malaysian government’s perception of migrant labor as a temporary solution to labor shortages, leading to policies that often restrict the rights of these workers. Reliance on flexible employment contracts has been criticized for contributing to the precarious nature of employment, with workers often lacking long-term security and benefits (Wahab 2023; Low 2025). Consequently, efforts to advocate for migrant rights have been underpinned by this vulnerability, with civil society organizations emphasizing the need for regulatory reforms in line with international human rights standards to ensure migrant workers are treated fairly and humanely (Low 2025; Fitria 2023; Siddiqui 2012; Revidy and Mustofa 2024).

Based on various research results that have been explained previously, the law and governance of labor migration in Indonesia and Malaysia are both immature, which results in migrant workers being forced to work in vulnerable conditions; in addition, there are socioeconomic injustices, including low-paid migrants, migrants receiving less legal protection, and migrants who contribute significantly to the Malaysian economy, but do not receive their proper rights (Dhanani et al. 2009; Ngan and Chan 2013; Bartley 2010; Oemar 2020). Another problem is that poor migration governance perpetuates structural exploitation, such as when people migrate forcibly from their country of origin due to poverty and are oppressed in their new country due to weak legal status (Dhanani et al. 2009; Ngan and Chan 2013; Bartley 2010; Oemar 2020). Migrant worker issues can be addressed in Indonesia and Malaysia by strengthening training for monitoring agents, reforming migration governance from rural areas, and other measures (Dhanani et al. 2009; Ngan and Chan 2013; Bartley 2010; Oemar 2020). Harmonizing labor laws to provide equal protection to migrant workers with local workers is another option in Malaysia. Updating the Memorandum of Understanding on migrant workers is crucial for bilateral cooperation between Indonesia and Malaysia, with an emphasis on protection rather than simply providing cheap labor (Dhanani et al. 2009; Ngan and Chan 2013; Bartley 2010; Oemar 2020).

This comparative study of labor laws in Malaysia and Indonesia finds differences in the application of labor laws, the impact on the informal sector, compliance with international labor standards, and the need for policy changes to improve working conditions in both countries. The decentralization of labor law enforcement, which has resulted in regional differences in policy implementation and enforcement, significantly weakens Indonesia’s ability to effectively protect migrant workers. While decentralization is intended to increase responsiveness and bring governance closer to the local context, it often results in fragmented responsibilities, leading to disparities in legal protection, resource allocation, and stakeholder coordination. Migrant workers are already at risk, and in some places, local officials may lack the capacity, expertise, or political will to adequately enforce national labor standards. These structural flaws not only reduce uniformity in legal protection but also provide opportunities for unscrupulous employers and labor agents, facilitating human rights violations and exploitation. To address these issues, centralized oversight and accountability systems must be restored. This will ensure that all levels of law enforcement agencies have the resources, accountability, and training they need to enforce consistent protections across the country.

Based on the findings and discussion, the researcher believes that this study has significant importance for students, especially in the context of politics, economics, and human rights. The reasons are as follows: (1) Politically and administratively, this study not only reveals structural weaknesses in the governance system but also shows how systemic problems arise from protection failures, thus requiring strong policy interventions; (2) Legally and socially, this study emphasizes the need for Indonesia and Malaysia to comply with international labor standards while addressing systemic disorganization. This is crucial to ensure justice for migrant workers (Taran 2001); (3) Economically and politically, this study provides an empirical basis for both countries to strengthen oversight and accountability in order to build effective and sustainable protection. This is in line with Van Ginneken’s (2013) argument that policy reform is crucial for consistent and effective protection of migrant workers by state authorities; and (4) Socially and humanitarianly, this study addresses the core issues of exploitation and human rights violations against migrant workers. By identifying gaps in law enforcement and implementation in both countries, it seeks to strengthen protection mechanisms for vulnerable workers, consistent with the findings of Bosniak (1991) and Foo (1994), who argue that human rights protection for vulnerable workers should be enhanced and guaranteed by state authorities.

6. Implications of Theoretical, Practical, and Policy

Based on the findings and discussions of the research that have been put forward previously, we try to highlight several important implications in this research, such as:

The theoretical implication of this study is the need to advance comparative institutionalism by demonstrating how deeply entrenched governance structures, legal frameworks, and historical legacies shape migrant worker protection in Indonesia and Malaysia. The study observes that differences in labor law enforcement, the informal sector, and institutional complementarities are not superficial, but rooted in systemic and historical foundations. This insight underscores the importance of an interdisciplinary approach that considers legal, political, economic, and cultural dimensions. Thus, the study expands theoretical understanding by arguing that sustainable reform in migrant governance requires examining institutional practices within their socio-historical context, rather than focusing solely on legal prescriptions.

In terms of practical implications, the results of this study suggest that when developing interventions for the protection of migrant workers, stakeholders (including governments, non-governmental organizations, and international organizations) must be aware of the impact of the institutional context. In addition to legal reform, practical steps should also be taken to address the underlying institutional inefficiencies identified by this study, such as gaps in law enforcement and bureaucratic fragmentation. Law enforcement and oversight can be improved, for example, by integrating institutional capacity-building initiatives and enhancing coordination across levels of government. Furthermore, specific strategies that reshape institutional incentives and promote more uniform and equitable protection for migrant workers in both countries are enabled by understanding the systemic underpinnings of informality and compliance.

In “Policy Implications,” this study proposes a comprehensive strategy that considers the institutional foundations of migrant governance from a policy perspective. Reforms that address the coherence and stability of institutional arrangements and the content of laws should be a top priority for policymakers. Examples of such reforms include the reorganization of Malaysia’s dual labor market system and policy coordination across Indonesia. Drawing on insights from comparative institutionalism, policies should seek to integrate reforms into broader institutional frameworks to create long-term institutional change that prevents unfair treatment and exploitative behavior. To ensure that legal and policy interventions are contextually appropriate and effective, international cooperation, including bilateral reform agreements and adherence to international labor standards, must also be grounded in an awareness of each country’s institutional realities.

7. Conclusions and Limitations

This study highlights the significance of institutional structures in determining the protection and governance of migrant workers in Indonesia and Malaysia. Applying the comparative institutionalism theory makes it evident that each country’s unique historical, political, and economic circumstances play a significant role in the variations in labor rights, legal enforcement, and socioeconomic conditions. Ultimately, by affecting how laws are implemented and perceived locally, these institutional differences have an impact on the safety and welfare of migrant workers in both nations.

The findings highlight the persistent challenges faced by migrant workers, including their vulnerability to exploitation, their inability to obtain legal education, and the unequal enforcement of labor laws. Despite existing legal frameworks, the informal sector’s dynamics, fragmented governance, and structural inefficiencies hinder effective protection. The need for systemic reforms that focus on altering the underlying institutional incentives, coordination mechanisms, and enforcement capacities rather than just changing laws is highlighted in order to establish a more equitable workplace.

The study practically encourages greater bilateral cooperation between Indonesia and Malaysia by emphasizing the need to modernize and harmonize agreements, such as the Memorandum of Understanding, to reflect more extensive institutional reforms. Building institutional capacity, improving monitoring systems, and promoting inclusive stakeholder participation are crucial to ensuring that migrant protections are effective and sustainable. Addressing systemic institutional weaknesses can lead to more consistent law enforcement and better adherence to international labor standards.

Ultimately, the study promotes a thorough approach to policymaking that takes institutional and legal reform into account. Recognizing the influence of historical, political, and cultural factors will help policymakers develop interventions that are appropriate for the situation and have the potential to result in long-lasting change. By putting in place more thorough institutional frameworks, Indonesia and Malaysia can develop more robust, inclusive, and equitable systems that safeguard the rights and dignity of migrant workers, promoting social justice and regional economic stability in the process.

This study is limited to an in-depth analysis of the laws and policies chosen by the author in building the study in study. Future research is expected to explore several other policies that can complement this study, so that it can complete and develop the problem of why labor law experiences injustice and many government governance errors in its implementation, which can be applied in various countries, especially in Indonesia and Malaysia. In addition, further research can be focused on transnational cooperation between Indonesia and Malaysia, which emphasizes the importance of updating the Memorandum of Understanding to effectively improve protection for migrant workers. The challenges in the current framework require greater diplomatic engagement to uphold labor rights and improve protection mechanisms (Paksi and Renta 2023; Saefudin 2024; Santosa et al. 2024). Numerous earlier studies have demonstrated that the safety and wellbeing of Indonesian migrant workers in Malaysia can be seriously jeopardized by the agreement’s failure to be updated, particularly when there is abuse or a violation of their rights (Mindarti et al. 2021). In summary, this review of the literature on the comparative labor laws for migrant workers in Malaysia and Indonesia reflects the intricate interactions between legal frameworks, difficulties in enforcing the law, problems with healthcare access, and the socioeconomic realities that workers face. Ensuring that migrant workers receive the protections to which they are legally entitled under both national and international law requires sustained advocacy, extensive policy reform, and international collaboration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and A.A.; Supervision, Y.K. and A.A.; methodology, software, machine learning, and prediction, Y.K. and A.A.; data curation, Investigation, writing—original draft preparation, Y.K. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, Y.K. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone who has helped directly and indirectly in completing this study. This study also acknowledges the use of AI-generated guidance to assist researchers in grammar checking, paraphrasing, proofreading, and improving English style (here, the author uses CHATGPT Pro and GEMINI 2.5 Pro). In addition, the use of AI in research is limited to compiling outlines or initial ideas (such as brainstorming) on research topics, as well as compiling general literature summaries (here, the author uses ChatGPT Pro and Scopus AI). The authors declare that this research is original and that there were no ethical violations in the use of AI tools in our research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Existing and rare conditions are important to be addressed in improving the conditions of migrant workers in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Table A1.

Existing and rare conditions are important to be addressed in improving the conditions of migrant workers in Indonesia and Malaysia.

| No | Countries | Problems/Existing Conditions | Formalizing the Informal Sector | Complying with International Labor Standards | Important Steps to Improve Labor Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indonesia | The decentralization of labor law enforcement in Indonesia has resulted in uneven law enforcement across regions, weakening overall worker compliance and protection (Harahap et al. 2024). Indonesia’s legal system also faces challenges in labor supervision, with weaknesses in substance, structure, and culture impacting the effectiveness of legal protection for workers (Pujiastuti and Purwanti 2018). In addition, the lengthy and convoluted judicial system further complicates the enforcement of workers’ rights (Musakhonovich et al. 2024). | The informal sector in Indonesia is quite large but neglected in economic and development policies, leading to persistent problems such as spatial uncertainty, financial constraints, and skills deficits (Zusmelia et al. 2019; Anggara 2025). Recent legislative reforms aim to include informal sector workers under legal protection, but practical implementation remains a challenge (Setiyono and Chalmers 2018). Institutional strengthening, such as providing space, financial support, and capacity building, is recommended to address these issues (Zusmelia et al. 2019). | There are inconsistencies between national labor laws and international standards (Mofea 2024). Indonesia has ratified several ILO conventions, but aligning domestic laws with these international standards remains a challenge (Mofea 2024). | Strengthen Enforcement (Harahap et al. 2024; Pujiastuti and Purwanti 2018). Formalize the Informal Sector (Zusmelia et al. 2019). Align with International Standards (Mofea 2024). |

| 2 | Malaysia | Malaysia’s centralized government, in particular, has struggled to protect migrant workers, highlighting the need for stronger law enforcement mechanisms (Harahap et al. 2024). Despite laws such as the Employment Act 1955, enforcement remains a challenge, especially in addressing issues such as sexual harassment (Taufiqurrohman et al. 2024). | In Malaysia, the high reliance on migrant workers suggests that formalizing employment practices could assist in better regulation and protection (Harahap et al. 2024). | Similar to Indonesia, Malaysia faces challenges in aligning its labor laws with international standards (Harahap et al. 2024; Taufiqurrohman et al. 2024). | Enhance Protection for Migrant Workers (Harahap et al. 2024). Improve Legal Framework (Taufiqurrohman et al. 2024). Strengthen Centralized Enforcement (Harahap et al. 2024). |

Source: Processed by authors (Taufiqurrohman et al. 2024; Harahap et al. 2024; Zusmelia et al. 2019; Pujiastuti and Purwanti 2018; Musakhonovich et al. 2024; Mofea 2024; Anggara 2025), 2025.

Table A2.

Key Differences in Labor Law Enforcement Mechanisms Between Indonesia and Malaysia.

Table A2.

Key Differences in Labor Law Enforcement Mechanisms Between Indonesia and Malaysia.

| No | Countries | Law | Issues Highlighted | Critical Policy Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indonesia | Law Number 39 of 2004 concerning the placement and protection of Indonesian workers abroad. | One of the main issues that stands out from Law No. 39 of 2004 is its focus which is considered to be heavier on the aspect of placement or sending workers business, rather than on the protection of workers themselves, which results in the vulnerability of Indonesian migrant workers to exploitation and human trafficking crimes, exacerbated by weak coordination between government agencies, minimal supervision and law enforcement against rogue PPTKIS, as well as limited coverage of protection, especially for domestic sector workers and undocumented (illegal) migrant workers. | This policy was indeed a significant milestone because, for the first time, it provided a clear legal basis for the protection of Indonesian migrant workers and structured the roles of the government and the private sector. However, its implementation in the field was often ineffective and actually opened up space for the dominance of profit-oriented private parties. As a result, worker protection was often neglected, and their welfare remained vulnerable. Normative weaknesses inconsistent with international standards ultimately led to legal reform through Law Number 18 of 2017. |

| Law Number 18 of 2017 concerning the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers. | Although aimed at strengthening protection, Law Number 18 of 2017 (the PPMI Law) still faces significant obstacles. The transfer of responsibility to local governments is often underfunded and understaffed, leading to delays in service delivery. Poor coordination between institutions, coupled with sectoral interests, weakens law enforcement against human trafficking and illegal placement. Meanwhile, many migrant workers, especially domestic workers, remain highly vulnerable to exploitation abroad. | Law No. 18 of 2017 marks a positive shift by embedding protection as the core principle of migration governance and broadening who qualifies as a migrant worker under state protection. Yet, its implementation suffers from slow regulatory harmonization, creating overlapping institutional roles and bureaucratic inefficiency. The persistence of high recruitment costs continues to trap workers in debt and exploitative conditions, undermining the law’s protective intent. In essence, the policy reflects strong normative progress but weak operational realization, leaving migrant welfare largely aspirational rather than guaranteed. | ||

| Government Regulation No. 59 of 2021 concerning the Implementation of Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers. | Government Regulation 59/2021 faces significant implementation challenges, particularly in ensuring the readiness and capacity of regional governments at the provincial and district/city levels to fulfill their mandated roles, including financing and administering training and competency certification. Furthermore, a central issue that remains unresolved is the effectiveness of the zero-cost policy, which is regulated in its implementation. Many prospective migrant workers are still burdened with high, unregistered fees (overcharging), as well as the classic problem of overlapping field coordination between agencies that is not yet fully digitally integrated. | Government Regulation 59/2021 represents a step forward by streamlining services through the LTSA system and enhancing migrant workers’ access to social protection programs. However, its implementation often burdens local governments that lack adequate administrative capacity and resources. The regulation also fails to address the persistent influence of brokers and illegal placement networks that exploit unregistered workers. Ultimately, while the policy improves formal structures, it remains limited in tackling the deeper systemic issues of migration governance. | ||

| Presidential Regulation No. 90 of 2019 concerning the Indonesian Migrant Workers Protection Agency. | One of the main issues with this regulation is a major clash between it and a higher-level law, specifically Law No. 18 of 2017. While the law outlines certain authorities for the Ministry of Manpower, this regulation seems to hand some of those very same responsibilities over to BP2MI. This creates a messy situation where legal certainty is up in the air, a problem that could be exploited. This bureaucratic confusion does not just exist on paper; it can also make the already difficult and lengthy process for migrant workers even more complicated, which unfortunately pushes some of them to bypass the official routes and use illegal channels, making them vulnerable to exploitation. | This regulation signifies a major institutional reform by placing migrant worker protection under BP2MI’s centralized authority and direct presidential supervision. Ideally, this structure should enhance coordination and create a unified national strategy for migrant protection. However, poor enforcement and limited control over illegal recruitment continue to undermine its goals. In practice, the regulation’s strong framework has yet to translate into tangible safety or justice for many vulnerable migrant workers. | ||

| Law No. 6 of 2023 concerning the Stipulation of Government Regulation in Lieu of Law Number 2 of 2022 concerning Job Creation into Law. | The most controversial part of Law No. 6 of 2023 lies in the labor cluster, where perceived erosion of workers’ rights has sparked protests and judicial reviews. Key concerns include broader use of fixed-term contracts and outsourcing, a simpler but less favorable wage formula, reduced severance pay, and termination rules seen as making layoffs easier for employers. | Law No. 6 of 2023 reflects the government’s ambition to streamline bureaucracy, attract investment, and stimulate job creation by simplifying overlapping regulations. Proponents view it as a breakthrough that enhances Indonesia’s global competitiveness and supports MSME development. Yet, the law’s deregulatory nature has raised serious concerns about weakened labor protections and growing employer dominance. Ultimately, it exposes a policy trade-off where economic efficiency may come at the expense of workers’ security and social justice. | ||

| 2 | Malaysia | Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Migrant Smuggling Act 2007 (Malaysia)/ATIPSOM 2007 | Enforcement of ATIPSOM 2007 faces gaps, with victims often treated as ‘illegal immigrants,’ risking re-victimization. Key challenges include the high burden of proof in labor trafficking cases, limited specialized training for frontline officers, and weak coordination among agencies handling investigation, prosecution, and victim protection. | The ATIPSOM Act marks significant progress by providing a dedicated and powerful legal framework to combat human trafficking with stricter penalties and a victim-centered approach aligned with global standards. However, its implementation often falls short, as victims are frequently misidentified and detained as offenders. This contradiction weakens the law’s core purpose of protection and discourages victims from seeking justice. Consequently, despite strong legislation, conviction rates remain low, revealing a deep gap between legal intent and practical enforcement. |

| Employees’ Social Security Act 1969 Malaysia/SOCSO Act 1969 or PERKESO Act 1969 | A major challenge in implementing the SOCSO Act is ensuring employer compliance, especially in the informal and SME sectors, leaving many workers unregistered and unprotected. Concerns have also been raised about the sustainability of the Invalidity Pension Scheme, as rising healthcare costs and payouts may outpace contributions, raising doubts about its long-term adequacy amid an aging population | The 1969 Act stands out for establishing a comprehensive social protection system that guarantees lifelong security through structured insurance and medical coverage for workers and their families. It has been instrumental in promoting social welfare and reducing financial vulnerability in cases of workplace injury or death. However, its exclusion of informal and self-employed workers has long left a significant portion of the labor force unprotected. Moreover, by barring employees from pursuing negligence claims, the Act arguably limits workers’ access to full legal justice in favor of administrative efficiency. | ||

| Employment Act 1955 (Malaysia) | The Act continues to face enforcement gaps, especially in protecting vulnerable groups such as domestic workers, gig workers, and migrants, who remain at risk of exploitation, passport retention, and forced labor. Employees earning above RM4,000 are also excluded from benefits like mandatory overtime pay, creating a tiered and uneven system of labor protection. | The Employment Act 1955 serves as a cornerstone of labor protection in Malaysia, ensuring minimum standards for fair treatment, paid leave, and regulated working hours. Its recent amendments have strengthened employee welfare and promoted a healthier work-life balance. However, the frequent updates and added obligations have placed growing pressure on employers, particularly small and medium enterprises. This tension highlights the policy challenge of balancing workers’ rights with business sustainability in a changing labor landscape. | ||

| Industrial Relations Act 1967 in Malaysia | A key challenge of the IRA 1967 is its slow and complex procedures, particularly in union recognition and unfair dismissal cases that can drag on for years through multiple stages of review. Although designed to protect workers, the Act is often criticized as overly formalistic, giving employers room to delay proceedings and weakening union efforts. | The Industrial Relations Act 1967 is pivotal in safeguarding workers from unfair dismissal by emphasizing fairness and equity through the Industrial Court. It offers employees a unique form of job security that goes beyond conventional legal frameworks. However, its stringent restrictions on union activity and the right to strike significantly limit workers’ collective power. As a result, while the Act strengthens individual protection, it simultaneously curtails broader labor freedom under tight government oversight. | ||