1. Introduction

The period between 2022–24, and the immediately preceding two years, brought significant and frequent shifts in asylum and protection policy in the UK, as explored throughout this special issue. Those shifts in law and policy have an impact on access to justice in relation to asylum and humanitarian protection, both increasing overall need, and substantially changing the geographies of that need, while the economics of legal aid provision became incrementally less viable and, consequently, neither overall provision nor the geographies of provision were able to adapt to the changed need.

In this article, I analyse the changes brought in by the Nationality and Borders Act (NABA) 2022 and the Illegal Migration Act (IMA) 2023, as well as non-legislative changes to asylum procedure, in relation to their impact on access to legally aided representation. I do so within two analytical frameworks: the legal aid demand framework I have previously set out elsewhere (

Wilding 2021), which borrows concepts from economics to help understand drivers of legal aid need; and spatial justice, a geographical perspective for understanding justice (in a broad sense) in the context of place.

By applying this unusual combination of socio-legal, economic and geographical approaches to the specific legislative and policy changes in the period 2022–24, I argue that the state actively (though not necessarily deliberately) creates legal aid deserts. It does so by placing people who need legal advice and representation into geographical spaces where they have no realistic prospect of obtaining that provision, and by creating market conditions which preclude expansion of legal aid services (either geographically or quantitatively) and failing to intervene in that market failure, while simultaneously adopting policies which increase demand or need for legal advice.

Although there has been research on the viability and economics of legal aid more generally (see for example,

Rickman et al. 1999;

Smith and Cape 2017), there has been no work pulling together the economics and geographies of provision for a particular area of law or set of legal provisions.

1 This article therefore seeks to offer a way to consider the demand consequences of any new legislation and policy, within a spatial framework of the availability and accessibility of legal advice and representation. It draws on the three legal aid jurisdictions of England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland (itself a rare approach in legal aid research), to show how the same set of legal changes were, or were not, addressed in the three different contexts.

NABA and IMA introduced provisions which required the involvement of immigration and asylum lawyers. These include the Differentiation and Priority Removal Notice provisions under NABA (s12 and ss20–25 respectively) and increased powers to detain under IMA (s12). Over approximately the same period, there were substantial (state-enforced) changes to geographical patterns of accommodation, and therefore of legal aid need, for people awaiting asylum decisions (

Wilding 2025b). The legislative changes to asylum and the accommodation policy changes, on the face of it, are two wholly different phenomena, but they coalesce around legal aid and the possibilities of access or lack of access to advice and representation.

This article starts from the premise that legal aid lawyers are absolutely necessary to make legislative and policy changes functional and operational. The system cannot function without lawyers to represent and support applicants and appellants, to assemble the evidence and address the legal issues. On some level, this is accepted by governments, as demonstrated in consultation papers such as that on fees for the new work which accompanied the IMA, and the statement of reasons with which the new government settled the Duncan Lewis judicial review challenge over the failure to raise legal aid rates for asylum (

Duncan Lewis Solicitors 2024). The fact that asylum cases remain within the scope of legal aid, despite the extensive cuts made through the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) Act 2012,

2 also indicates that even the Coalition government of 2010–2015 did not believe it could lawfully deny legal aid to people seeking asylum. Yet when asylum policy is changed for the whole UK, legal aid is rarely treated as a core part of the system, much less taken into account in developing the proposals (as opposed to consulting on what the fee rate should be once the legislative provisions are laid out).

I begin with a brief discussion of the three legal aid schemes, explaining key differences and drawing on data which demonstrates substantial deficits in asylum provision in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, somewhat in contrast to Scotland. I then set out the two theoretical lenses which I draw on throughout the article: first, the legal aid demand framework which facilitates discussion of the consequences for legal aid of the new laws and policies, and second, spatial justice, through which I discuss the shifting geographies of legal advice need brought about by changes in accommodation policy.

I then consider, in broadly chronological order, the changes created by NABA and IMA and non-legislative changes in the form of the Streamlined Asylum Process, framed in terms of the demand and cost consequences. I conclude with some comments on the relevance of this critique of the policies of the recent past for the future policies on both asylum in the UK and legal aid in its three jurisdictions.

2. The Three Legal Aid Systems in the UK

Immigration (including asylum) is a reserved policy area: the Westminster Parliament makes law and policy for the whole of the UK. Justice, however, is a devolved policy area for Scotland and Northern Ireland (not for Wales), meaning they have separate legal aid structures, fee schemes and rules although, in immigration and asylum, the Tribunal’s structure and procedure rules are tied to the England and Wales version, whereas they often diverge in devolved policy areas (

Wilding 2022b).

England and Wales has the most restrictive system of the three in terms of both scope for clients and who is permitted to do the work: only organisations holding a legal aid contract in the specific area of law can take a legal aid case (

Ling et al. 2025). Each contract holder has a geographical area in which it can operate. Fees have not increased since 1996 and were reduced by 10% in 2011; the low fees, combined with the unpaid administrative burden (including a wide range of tasks such as audit preparation, billing, funding applications and file reviews), have caused a loss of legal aid provision across areas of law (

Ling et al. 2025). Following a judicial review challenge over the government’s failure to secure the availability of asylum legal aid (

Fouzder 2024), the government has agreed (though not implemented at the time of writing) a 30% fee increase for immigration and housing work (

Ministry of Justice 2025).

In Scotland and Northern Ireland, legal aid scope is far broader, covering all immigration work, not only asylum, for clients who meet the financial means test (

Wilding 2022b). In Scotland, any solicitor with a practising certificate can register for legal aid in any area of law in which they are competent, and can then undertake as much or as little legal aid work as they wish in that category, in any part of Scotland. In Northern Ireland, any solicitor with a practising certificate may undertake legal aid work in any area of law, without further registration requirements, likewise with no minimum or maximum amount of work and no internal geographical restrictions.

Payment is on hourly rates in both Scotland and NI, in contrast to England and Wales’ fixed fees. Scottish fees have risen somewhat, by 5% in April 2021 and April 2022 and 10.2% in April 2023, but this followed a long period with no inflationary increases. The NI hourly fee remained at £43.25 for civil legal aid work since 1982, until a strike by immigration lawyers in 2025 resulted in an increase to £65 per hour (

Right to Remain 2025). Only a tiny number of firms undertook immigration legal aid work at all, and even fewer have a lawyer (let alone a team) who specialises in this area of law, but anecdotal evidence from Northern Ireland indicates a fairly rapid shift towards more firms and lawyers taking on asylum work since the fee increase.

Scottish solicitors describe ‘stealth cuts’ despite their incremental rate increases, whereby the Legal Aid Board ceases paying for elements of work which were previously billable, and ‘abates’ their bills (

Wilding 2022b). A long-running project to codify all policies on what is chargeable was published in August 2024 and was expected to resolve some of the conflict and inconsistency (

Scottish Legal Aid Board 2024). However, the new guidance created fixed ‘block fees’ for work on clients’ statements, apparently to simplify the payments (

Wilding 2025b), but failing to recognise changes in the way that the Home Office requires information from applicants, and creating a disincentive for solicitors to undertake thorough case preparation with clients—a problem already noted when fixed fees were imposed on criminal solicitors in Scotland (

Tata and Stephen 2006). At the same time, increased salaries for solicitors in Scottish government and public bodies have far outpaced the increases in legal aid fees, meaning firms are unable to retain their newly qualified lawyers (

Wilding 2025b).

Scotland is the only jurisdiction of the three where the body administering legal aid has a responsibility to research need and plan to meet it. The Legal Services Commission, which administered Legal Aid in England and Wales from 2000 until 2013, had a similar mandate to research and plan, but the Legal Aid Agency which replaced it has no such duty, as the LASPO Act did not impose one. Similarly, Northern Ireland’s Legal Services Agency, an executive agency of the Department of Justice established by the Legal Aid and Coroners’ Courts Act (NI) 2014, has no statutory mandate to inform itself as to whether need is being met, and its Framework Document does not refer to any strategy for doing so (

Legal Services Agency Northern Ireland 2024a). For England and Wales, the government has assumed since the Carter reforms in 2006 that its role was to create a market, and the market would expand to meet demand (

Carter 2006), while for Northern Ireland the state takes little role beyond deciding what rate it will pay for work done.

In my research on access to immigration legal advice across the UK, I calculated estimates for demand and provision in each of the three jurisdictions (

Wilding 2024). England and Wales had an overall deficit for the year to 31 August 2024 of at least 57%, or 54,555 main asylum applicants (excluding dependants) between new asylum applications and appeals and new legal aid cases opened. This was an increase on a 51% deficit the previous year and 40% in 2021–22. Applying a broader calculation to take into account matters other than an asylum application or appeal, but still within the scope of legal aid, the deficit was between 60–78,000 people across England and Wales, who could not access a legal aid lawyer for a matter which was likely to have been in scope (

Wilding 2025b). For Wales alone, the deficit was between 2300–3500 (

Wilding 2025b).

For Northern Ireland, overall, in the year to 31 March 2023 there was a deficit of around 1,100 cases, representing about 30% of eligible need. For asylum appeals, however, the deficit was greater, as there were 234 asylum appeals to the Tribunal in 2022–23 but only 83 grants of legal aid for First Tier Tribunal (FTT) appeals.

3 The deficit for the year to 31 March 2024 will certainly have been larger, as there were 846 asylum appeals to the FTT and there were only 186 grants of legal aid in the relevant Representation Higher category, which includes immigration bail as well as appeals (

Legal Services Agency Northern Ireland 2024b). In other words, at appeal level, the deficit was at least 660 cases, or 78%. It is to be hoped that the 2025 fee increase will help to address and reduce this deficit.

By contrast, Scotland does not have an obvious numerical or proportional deficit. The total number of cases opened in the immigration and asylum category outstripped the need estimate for the asylum, post-asylum settlement, domestic abuse and trafficking cases which were used as proxies for need. Although certain case types (particularly fresh asylum claims and refugee family reunion) are very difficult to place with representatives, partly because they are uneconomical, Scotland has avoided the obvious and substantial deficits in provision arising in the rest of the UK.

Within each jurisdiction, however, there are significant spatial inequalities. In Scotland, there is very little specialist immigration and asylum provision outside Glasgow where, until 2022, almost all sanctuary seekers in Scotland were placed. In Northern Ireland, the limited provision available is in Belfast. In England and Wales there is a deficit in every region, including London, with particular shortages in the South West, Wales, parts of the East of England, and the south coast, although the largest numerical deficits are in the North West and Yorkshire and the Humber, which at first glance (i.e., without considering need) appear to have more provision than elsewhere. Having set out the position in the three jurisdictions of the UK, I now consider how we can understand demand for legal aid.

3. The Demand Framework

I have previously set out a framework for understanding demand for legal aid work and its consequences for costs (

Wilding 2021). As I argued then, the failure to structure legal aid around an evidenced and nuanced understanding of legal aid need has led to payment and auditing systems which align to neither the drivers of demand nor the actual needs of clients, and this creates serious difficulties for legal aid providers who want to offer high quality legal representation. This framework enables examination of how the NABA and IMA intensified legal aid shortages and denied access to justice.

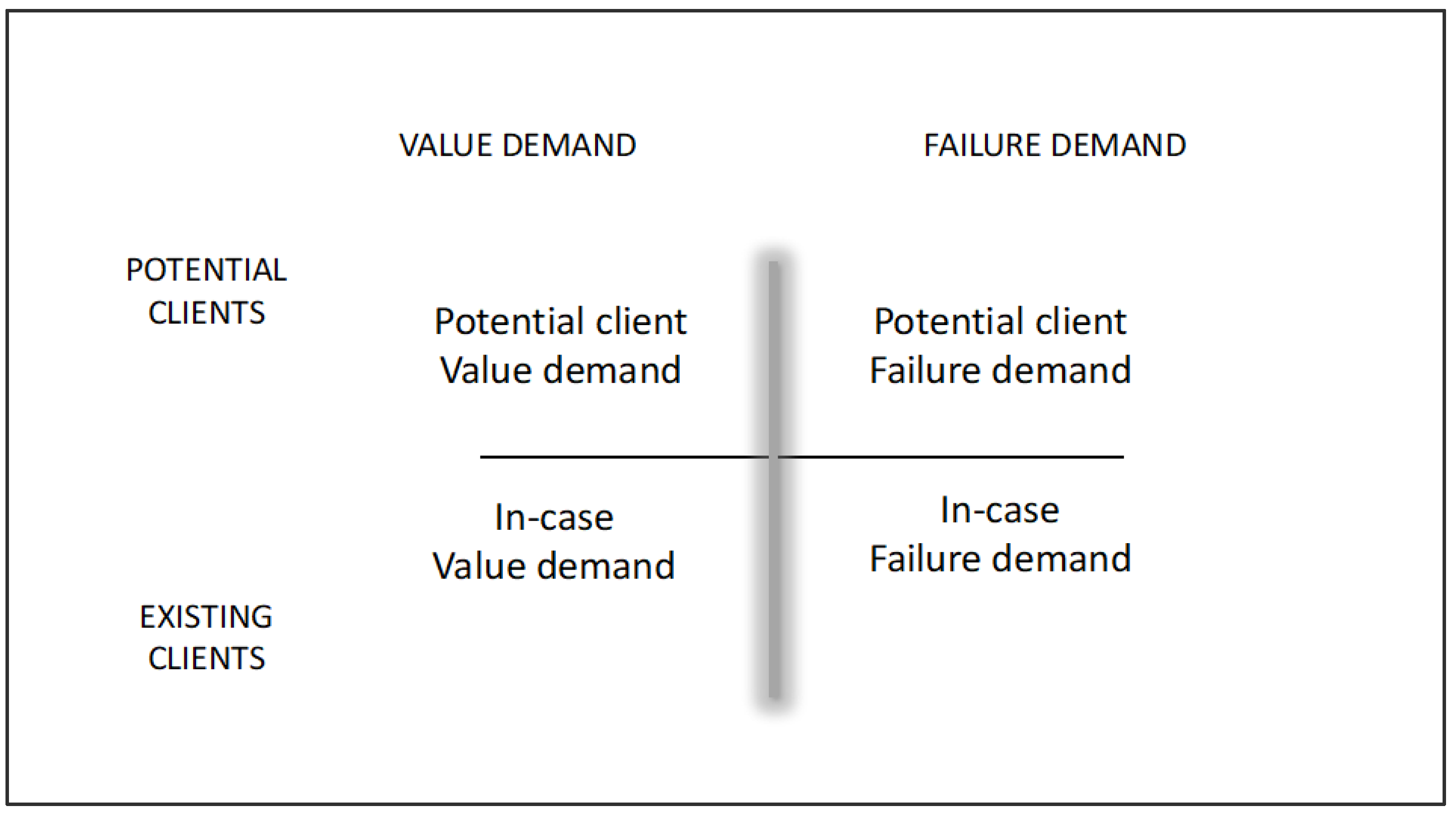

Within this four-square framework (see

Figure 1), demand is divided into potential-client demand on the vertical axis—i.e., that from all the people who would like to obtain the services of the legal aid provider—and in-case demand, which is all of the demand for work within a case which the provider has taken on. Potential client demand in asylum is heavily influenced, of course, by the number of people claiming asylum, but it can also be affected by factors within asylum procedures, including the number and frequency of status renewals required and policy decisions about whether sanctuary seekers from high grant rate countries need to go through the full Refugee Status Determination procedure. In-case demand may be reduced or increased by decisions about what the procedure entails, what steps are required of lawyers and applicants, and timescales.

Demand is also split on the horizontal axis into value demand and failure demand (

Seddon 2008). Value demand is for work that serves the purpose of the system; failure demand relates to work which arises because either the system itself is poorly set up or because some element is not functioning properly. Unless there is an infinite capacity for provision, elevating in-case failure demand reduces the amount of potential-client value work which can be done.

Some demand may be on the borderline between value and failure, and this is represented by a thicker, blurred line representing potential grey areas between the two. Clearly there may also be differing views as to what is or should be the system’s purpose and how it should function, but I argue that these differing views can only cover a small part of the spectrum of demand. This becomes relevant later in the article when discussing points such as the policy of differentiation between recognised refugees by the manner of their arrival in the UK: where there is no evidential basis for a policy which creates or escalates demand, it cannot be categorised as value demand, regardless of the personal or political opinion underpinning it.

This means there are four types of demand: potential-client value demand, potential-client failure demand, in-case value demand and in-case failure demand. Each instance of failure demand has cost consequences. These consequences are not discussed in detail here except to note that when the legal aid funding scheme is not well-attuned to fund all necessary work, frequently the costs generated or escalated by failure demand are shifted onto the legal aid provider. They are rarely borne by either the legal aid funder or the department which created the failure demand (in this case the Home Office).

Using this framework, we can analyse the main elements of the (intended or actual) new work created by NABA and IMA. One could of course argue that almost all of the new work is failure demand, since it represents additional steps whose sole purpose is performative (

Griffiths and Trebilcock 2022;

Clarke 2025), rather than an evidence-based improvement to the asylum system itself (

Hodgson 2024). In particular, those of the new proposals which were highly likely to be unworkable from the outset, such as the plan to move a percentage of people seeking asylum to Rwanda (

UK Government 2022), may be seen as creating failure demand with generated costs since they still required litigation to stop them. However, I discuss the elements of the new work separately to consider their consequences for asylum legal aid.

The purpose of this is to demonstrate why future policy and legislative changes in immigration and asylum (or arguably any area of law) must be accompanied by a thorough analysis of the consequences for legal aid need, provision and costs—and to suggest a structure for that analysis. It is useful to weave together this nuanced understanding of demand with a spatial justice framework, in order to more fully analyse the access to justice consequences of the legislative and policy changes in the 2022–24 period.

4. Spatial Justice

In

Przybylinski’s (

2023, p. 202) exploration of spatial justice as a framework, he describes it as ‘a useful analytical tool for identifying conditions where injustices take place. … [T]he utility of a spatial justice approach lies in the way it analyses potentially unjust conditions and how they are emplaced.’ I refer here to justice in its narrower sense—legal justice—which is denied to those who are physically distant from a source of legal representation and lack both the means to travel and the physical means (or emotional resources) to access it remotely.

4Spatially unequal distribution of access to legal advice and representation results in spatially uneven possibilities of (meaningfully) accessing the legal right to apply for refugee status determination, within the terms of the Refugee Convention: we know that representation significantly enhances prospects of success in immigration and asylum appeals (

Genn and Genn 1989;

Adler and Gulland 2003). Distributional inequalities commonly affect access to basic services, as

Soja (

2013) points out, but each unit of local governance usually makes some kind of effort to ensure access exists in all areas, or for all residents. This, however, is not the case for asylum legal representation, as I will explain below. These distributional inequalities, Soja argues, result in ‘an often self-perpetuating interweaving of spatial injustices that, at least after passing a certain level of tolerance, can be seen as a fundamental violation of urban-based civil rights and legal or constitutional guarantees…’ (

Soja 2013, p. 47).

Specifically in relation to systems of legal justice, Soja notes (in the US context) that their ‘provisioning’ tends to be thought of on a ‘national scale, available in theory to all inhabitants equally’ (

Soja 2013, p. 49). Yet, as Gilmore argues, spatial inequalities are not incidental but are actively produced through state policy (

Gilmore 2022); the withdrawal of state responsibility for addressing those inequalities amounts to what

Harvey (

2010) terms an organised abandonment. The state neglect of a statutory responsibility to secure a minimum level of access is what I have described elsewhere as justice chauvinism (

Wilding 2025a).

The particular utility of combining the spatial justice framing with the demand framework is that, when we look at demand and supply through the geographical lens, the spatiality of access to legal rights becomes evident. If, through changes to procedure or timescales, the government increases the in-case demand for each individual, but there is a limited supply overall, then this necessarily reduces the proportion of potential client demand that can be met. Where regional supply is extremely limited, within a context of limited supply nationally, the result is spatial disadvantage.

I now move to considering the demand consequences of the legislative and non-legislative changes in the 2022–24 period, and the impact which they had on access to legal representation (or would have had if brought into force) in this spatial context.

5. Demand Creation Under NABA 2022

Major demand-generating changes under NABA included the Differentiation provisions (s12), Priority Removal Notices (s20–25), a crime of illegal arrival (s40(2)D1 and E1), and changes to age assessment procedures (s49–57). The introduction of a crime of arrival (as opposed to illegal entry, which previously did not occur if the person claimed asylum at port) is an example of escalating legal aid demand beyond the asylum sphere. The offence is committed even if the person is later recognised as a refugee. This creates both a demand on legal aid and a spatial injustice from the very outset of the asylum process, by denying the right to arrive in a place even if the individual was as a matter of fact entitled to refuge there. Criminal legal aid is needed if the state decides to charge an individual with the offence of arrival, and additional legal advice and representation needs arise if the end consequence is that the person needs more assistance to overcome the obstacle of a criminal conviction establish their right to remain in the UK.

The changes to age assessment (NABA s 59–57) included a new power, rapidly implemented after the Act received Royal Assent in July, to make regulations providing for use of ‘scientific methods’ of age assessment including dental X-rays, bone density scans of the hands and wrists, and MRIs of knees and collar bones (NABA s52). Since all of these ‘scientific methods’ have previously been abandoned as unreliable and unethical (

Garcia and Moodie 2017) all related work must be characterised as failure demand. NABA also gave the Home Secretary the new power to request further evidence of a young person’s age even when it has been accepted by a local authority, effectively to challenge the local authority’s assessment (s50)—an entirely new stage of the process.

In 2021–22, when NABA was going through Parliament, there was a deficit of 40% between new asylum applications by main applicants and the number of new asylum legal aid matters opened by providers, or at least 25,000 people (

Wilding 2022b), but there was no action either during or after the passage of the Act to increase availability of legal aid. The rest of this section focuses on two key changes under NABA which drove up (albeit relatively briefly) asylum legal aid need, and the effects of this for the three jurisdictions.

5.1. Differentiation

NABA differentiated between recognised refugees by mode of arrival. Section 12 created two groups: Group 1 consisted of those who arrived in the UK directly from a country or territory where their life or freedom was at risk, and presented themselves promptly to the UK authorities to claim asylum; Group 2 consisted of anyone else seeking asylum—i.e., those who arrived via any third country in which their life was not at risk. Those in Group 1 would receive the same status, rights and entitlements as before, while Group 2 refugees, despite being recognised as genuine refugees whose life or freedom was at risk in their home countries, would receive Temporary Refugee Permission. That meant only 30 months’ leave instead of five years, a ten-year route to settlement instead of five, with more limited rights to family reunification. This was despite the acknowledgement that a recognised refugee would almost certainly have their renewal applications granted.

Accordingly, a Group 1 refugee needed legal representation at two stages: on arrival, in respect of their asylum application or appeal, and at the five-year point, for their settlement application. A Group 2 refugee needed similar legal representation for their asylum application or appeal, but also to make representations that they should not be treated as a Group 2 refugee, and then (if unsuccessful in the latter) for three renewal applications, plus the settlement application: six instances instead of two, four of which can only be considered failure demand, caused by a poorly designed system. Each of those instances also requires deployment of the Home Office’s decision-making resources.

Each of those refugees might also need legal assistance for a family reunification application, but those in Group 2 faced an additional legal hurdle, i.e., demonstrating ‘insurmountable obstacles’ to family life continuing without reunification. Since family reunification under the Immigration Rules applies only to a pre-flight spouse and minor children, it is difficult to see how those insurmountable obstacles would not apply, meaning the additional work constituted yet more in-case failure demand.

This differentiation by mode of arrival was presented (without evidence) as a deterrent measure which would discourage people from arriving in the UK via other countries (i.e., at all), but the only verifiable change was to escalate in-case demand for legal representation and for Home Office administrative work. The Differentiation provision came into force on 28 June 2022

5 and was abandoned on 8 June 2023 (

Jenrick 2023) because it was to be superseded by the inadmissibility provisions in the IMA (i.e., the refusal to process claims at all). All recipients of Temporary Refugee Protection were then to be contacted and given the standard refugee status.

Could these elements be more generously characterised as value demand within a valid attempt to make systemic change, even if it was ultimately abandoned? I argue not. There was no evidential basis for believing that changes to the form and duration of leave would deter people from attempting to reach the UK in small boats or by other risky methods. As

Colin Yeo (

2023) wrote on the Free Movement blog, it represented ‘the ascendancy of politics over reality.’

5.2. Priority Removal Notices

The Priority Removal Notice (PRN) was also introduced in NABA 2022, in ss20–25, but was never brought into force. According to the explanatory notes, the purpose was to ‘reduce the extent to which people can frustrate removals through sequential or unmeritorious claims, appeals or legal action’.

6 Alternatively, it was ‘to give legislative expression to a quasi-religious belief within the Home Office that evidence submitted late is inherently inferior to evidence submitted early.’ (

Free Movement 2022).

The notice would have had the effect of truncating appeal rights for any claim made within 12 months of the notice and of requiring a decision maker to treat the applicant’s credibility as damaged if they provide any evidence after the deadline given in the PRN. S22(4) states that:

In determining whether to believe a statement made by or on behalf of the PRN recipient, a deciding authority must take account, as damaging the PRN recipient’s credibility, of the late provision of the material, unless there are good reasons why it was provided late.

Even where there was no PRN, s22(5) would have required the Tribunal to amend its procedure rules to compel its judges to include a statement in their reasoning, explaining whether s22 applies and, if so, that it has taken account of the fact the relevant material was provided late.

This creates additional in-case demand (1) for a lawyer to assist the applicant to respond to the notice within a short time, including all evidence which may be relevant, despite the potential complexity of the case and the difficulties in obtaining such evidence; and (2) for additional work within the asylum claim to overcome the adverse credibility presumption or to provide evidence in the form of witness statements or a paper trail explaining why the evidence is ‘late’. Since the intention (in England and Wales) was to allow for seven hours of non-means tested legal work, the cost of this new demand would have rested at least partly with the Legal Aid Agency, though it may have spilled over to the legal representative. In Scotland, with hourly rates, the costs should rest with the Legal Aid Board, while in NI, the (then) very low hourly rate meant the costs would have fallen on both the legal aid funder and the lawyer, though it is doubtful whether the legal aid sector in NI could have met the new demand at all.

For the Tribunal, too, there would have been additional demand in addressing the s22 requirements to consider whether there was ‘late’ evidence and how that had been taken into account. Though relatively time-limited in individual cases, cumulatively it would have been a substantial additional piece of work for an already stretched Tribunal.

7 No doubt it would also have generated substantial litigation over the detailed meaning and scope of the provision.

6. Non-Legislative Changes

During and after the passage of NABA, the next significant changes came from policy, rather than legislation. The first significantly changed the geographies of demand in a way which could not be matched by provision. The second, amending the asylum procedure for certain nationalities, had the potential to significantly reduce demand for legal representation though, sadly, that potential went unrealised.

6.1. Shifts in Geography of Demand

In the period from 2022–24, there were very significant shifts in the geography of demand. The Home Office moved in April 2022 from its practice of the previous two decades of accommodating people seeking asylum in specific parts of the UK, known as ‘dispersal areas’, via a voluntary (for the host local authority) process of ‘widening dispersal’, to the mandatory ‘full dispersal’ model, whereby every local authority in the country would accommodate adults and families in asylum support.

8 That was preceded and accompanied by vast expansion in the use of ‘contingency hotels’ and other large accommodation sites like former barracks, from 2020 onwards, despite these regularly being condemned as unsuitable (See for example

Neal 2021).

The National Transfer Scheme for unaccompanied children also moved from a voluntary to a mandatory basis in late 2021, meaning that every local authority (or every Health and Social Care Trust in Northern Ireland), now has responsibility for the care of unaccompanied children who arrived seeking asylum (

Home Office and Department for Education n.d.). By definition, that means those areas also host newly recognised refugees and people who have been refused asylum but remain in the UK without immigration status.

The obvious unfairness of placing all asylum applicants in one place (or a few places) is that it creates pressure on housing and services, meaning that those people are less likely to have access to support services and potentially further ghettoising the places which are already poorest (

Robinson et al. 2003;

Griffiths et al. 2005;

Wilding 2017). However, the ‘full dispersal’ model could only result in a fair system (for those seeking asylum) if state authorities also have regard to

creating a spatially fair system, including ensuring that legal representation is available everywhere and making sure that (across the whole system) in-case demand is shaped to what is available (in reality, not only in theory).

The geographical pattern of provider offices shows that there are often—though not always—more offices in the historical dispersal areas, which developed capacity at a time when the legal aid fee regime was (at least somewhat) more conducive to beginning or expanding legal aid work. This occurs most visibly in Glasgow, which previously hosted all of the asylum dispersal in Scotland and has very nearly all of the asylum and immigration legal aid provision, but it can also be seen in Birmingham, Liverpool and South Yorkshire, for example, though that provision may still be far below need. Meanwhile other areas have long hosted dispersal without having any concentration of legal aid provision: Hull, Stoke on Trent, Plymouth, Gloucester, for example.

The difficulty is that there is no prospect of a growth in capacity in areas which now host people seeking asylum, even those areas with larger numbers, because the legal aid regime is so hostile that it is near impossible for a new organisation to comply with the conditions to obtain a legal aid contract, recruit suitably qualified staff, manage the overzealous auditing and administrative burdens, and survive financially for the length of time it takes for asylum cases to close and to receive payment, even assuming that the fee is sufficient to break even. Only those which are willing to subsidise a legal aid asylum practice for several years, perhaps indefinitely, or to undertake the bare minimum of work on each case, are able to survive (

Wilding 2021). Far from increasing their capacity and moving into new geographical areas, many providers are withdrawing their capacity from legal aid and asylum appeals.

In this context of severe overall deficit, it is apparent that remote access is not a solution to the spatial inequalities.

9 This is further demonstrated in research on the ‘South West List’ (

Hynes and Summers 2025), which is operated by the Legal Aid Agency and updated weekly or fortnightly, purporting to name legal aid provider offices which have capacity to take on asylum work from the South West of England, which is recognised as a region of severe legal aid desert for immigration and asylum. Yet in twelve rounds of calls by the researchers to enquire about capacity, only 31% on average had capacity to take on any work from clients in the South West, and this was consistently lower for appeals work, with only 11% saying they had capacity for appeals.

In Northern Ireland, the changes to dispersal and care of unaccompanied children have brought about a particularly dramatic increase in need, especially since the Home Office resumed asylum processing for applicants other than those from high grant countries. As has been noted elsewhere, the asylum backlog has moved from applications to appeals stage (

Lenegan 2025), but capacity for appeals representation in Northern Ireland remained minimal, as noted above. Anecdotally, provision is increasing after a recent significant fee increase in March 2025. In Scotland, the shift from placing all those requiring asylum accommodation in Glasgow to accommodating in all parts of the country has created pools of need across a much wider area, including over 500 people accommodated in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire, around 150 miles from the centre of provision in Glasgow. This was the spatial context into which the legislative and procedural changes were introduced.

6.2. The Streamlined Asylum Procedure

The ‘streamlined’ asylum procedure was introduced in February 2023 (

Home Office and Department for Education n.d., updated 2024). The underlying idea was sensible and pragmatic: to deal with asylum applications from countries with a very high grant rate due to conflict or widespread persecution—initially Eritrea, Libya, Syria,

10 Yemen and Afghanistan—with a less intensive procedure. Advocates for this change (including me) pointed out that applicants from certain countries would almost certainly receive a grant of asylum if their nationality was accepted, regardless of details about their experiences before leaving, because of armed conflict, indiscriminate violence or widespread persecution (

Wilding 2022b). It makes little difference whether they are an opposition politician, a satirical cartoonist, a member of a religious minority, or an ordinary citizen.

On that basis, there was no value in requiring them to attend a full asylum interview, make statements or representations, or submit translated versions of documents, and no value in requiring the Home Office decision-maker to undertake a full consideration of the applicant’s case. All work, beyond establishing identity and nationality and carrying out security checks, could be characterised as failure demand if the overall objective was to determine whether or not the person should be granted asylum.

However, the ‘streamlined asylum procedure’ initially consisted of a paper form requiring all of the information that would normally be requested in person during an asylum interview, to be completed in English within 20 working days. This meant that applicants needed legal assistance to fill in the form—although the Home Office stated on the form that they did not—since the information they gave would determine whether or not their case was accepted. Many needed assistance with translation, which would have been provided in an asylum interview. Since legal aid lawyers are not funded to attend asylum interviews with adult applicants (only with unaccompanied children), this created an extra piece of work, as opposed to a mere amendment to manner and form, for the lawyer in effectively carrying out the interview in place of the Home Office.

Instead of meeting its potential to reduce demand for legal representation, therefore, the process suddenly increased demand, through a scheme which Hodgson describes as ‘designed to both downplay the importance of legal advice and make it practically difficult for a person to access legal advice’ (

Hodgson 2024). The Home Office was still requesting information that it did not need, creating failure demand, but it also funnelled a large volume of that demand into a very short period of time. Meanwhile in 2022–23 the deficit between new asylum claims by main applicants and new asylum legal aid cases opened had grown to at least 51%, or 37,450 people (

Wilding 2023).

The streamlined procedure caused further failure demand because numerous questionnaires went astray (

Grey and Garret,

2023;

Greater Manchester Immigration Aid Unit 2023). Despite the Home Office contracting out provision of accommodation to organisations of its choosing, it sent questionnaires to old addresses, so some applicants only received text messages ‘reminding’ them to complete forms which had not arrived. Those who did not complete and return a questionnaire were liable to be treated as having withdrawn their applications—a fact they were typically unaware of until their asylum support was stopped and they were left destitute until their asylum claim was reinstated (after further work by a lawyer and/or local authority and the Home Office).

In other words, the streamlined procedure offered an opportunity to reduce failure demand but instead created more of it. A reformed version now applies to children from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Sudan and South Sudan, whereby a genuinely shorter process aims to identify those who can be granted asylum after a short meeting, with no process for refusal, only for either a grant or re-routing back into the mainstream procedure (

Sella 2025;

Home Office 2024b). The guidance for adults currently only allows the streamlined procedure to be applied to those claiming before 7 March 2023, though claims made after that date no longer fall to be treated as inadmissible (

Home Office 2024a).

Into this context of extreme legal aid shortage and high in-case failure demand, the government introduced the IMA.

7. Demand Creation Under the Illegal Migration Act 2023

With the IMA, the government made a proactive choice to put forward legislation which invited legal challenge, accompanying it with a statement pursuant to s.19(1)(b) of the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), ‘that we believe we have credible legal arguments for the legislation but recognise that because it is novel, ambitious and untested, we cannot be sure we have a better than evens chance of success in the European Court in Strasbourg’ (

Home Office 2023). Only one piece of legislation, the Communications Act 2003, had previously been presented with a s19(1)(b) statement, and that related solely to one clause of the Bill, which prohibited political advertising and sponsorship in broadcast media, after the European Court of Human Rights had found a blanket ban to violate Art 10.

11 Although that did not necessarily mean the provisions of the Act were unlawful (

Kavanagh 2023), the potential incompatibility with the HRA was the broadest ever proposed in the quarter-century since it came into force. In this section, I focus primarily on the detention provisions (s12) and the changes to legal aid (s56).

7.1. Detention Under the IMA

Section 12 of the IMA came into force on 28 September 2023, enlarging the Secretary of State’s already broad powers to detain, encompassing anyone who ‘appears to be’ subject to the (as yet unenforced) duty to remove under s2 of the Act. Before the Act, the Hardial Singh principles

12 created a common law limit on the length and purpose of detention to a period which is reasonable in all the circumstances, for the purpose of removal. The Act removes judicial oversight of detention for the first 28 days (other than habeas corpus), limits the powers of judges to determine what is a reasonable period for detention, and codifies a ‘grace period’ in which continuing detention remains lawful despite a grant of bail while the Home Office makes accommodation arrangements. The Act also allows for an additional period of detention for ill-defined purposes.

Lawyers predicted ‘plenty of litigation about the government’s attempts to expand immigration detention’ and to limit the courts’ jurisdiction (

Schymyck 2023). There has already been litigation particularly on the interaction of the new powers to detain and the Home Office’s Adults at Risk policy, which should protect people who are unsuitable for detention on the basis of factors including physical or mental illness or being a victim of torture.

13 Alongside the increased detention powers in IMA, other policy changes also sought to reduce protections for detainees. For example, the Second Opinion Policy, introduced in June 2022 (and later ruled unlawful

14), instructed Home Office caseworkers to delay release decisions when they receive a medico-legal report indicating that a detainee is a victim of torture, and to seek a second opinion (

Home Office 2022). As with the Home Office power in NABA to challenge local authorities’ age assessments, this policy aimed to go behind existing protections within established decision-making systems. There were 234 judicial review applications relating to immigration detention in 2024—more than any other single category, with homelessness next on 201.

15 The figure in 2024 was a little lower than that in 2023, but higher than in 2022 and 2021,

16 indicating that the exercise of the powers may be creating need for legal intervention.

There is much that could be said about the spatial injustice of immigration detention, as with prison incarceration (

Gilmore 2008) but for current purposes the core problem is that, once a person is detained, access to legal advice is constrained to whichever provider is on the rota for the particular detention centre, and that provider may not have the required expertise to deal with unlawful detention work (

Bail for Immigration Detainees 2021). Not only that, but detention centre legal aid surgeries are now frequently conducted remotely, where previously they were face-to-face (

Bail for Immigration Detainees 2025), and this may not facilitate the relationship of trust needed for detainees who have experienced torture to disclose their experiences to a legal representative, via an interpreter, by telephone (

Creutzfeldt et al. 2024).

7.2. Legal Aid

Section 56(1-5) IMA makes amendments to legal aid legislation and regulations for England and Wales and s56(6–15) does so for Northern Ireland, in respect of fees for work arising under the IMA. Northern Ireland was added to what was then Clause 55 of the Bill by way of amendment in the House of Lords on 3 July 2023, having apparently been forgotten until then.

17 The Scottish Government confirmed it did not require legislative provision to adapt to the new work.

In recognition that the Bill, if enacted, would create discrete additional legal aid need, the government consulted from 27 June to 24 July 2023 on funding for the new work in England and Wales (

Ministry of Justice 2023b), (there does not appear to have been any consultation for Northern Ireland) and the consultation itself was revealing in terms of the government’s attitude to legal aid provision. The consultation document stated:

The IMB introduces additional demand for legal aid because of the number of individuals captured by the Bill and timescales for removal (eight days to make a claim). This new and large volume of work created by the IMB is a unique challenge and we have been considering the most effective way to ensure that all individuals served with a removal notice under the IMB have access to legally- aided advice and representation within the required timescales. This is required in order to support the overall delivery of the IMB, a key Government priority.

The document suggested a 15% uplift on fees to respond to the new work, on the basis that, ‘We understand the challenges posed by the existing caseload and the capacity constraints within the immigration legal aid sector.’ [Paragraph 31] This was at a time when, as above, the asylum legal aid deficit stood at 51% (

Wilding 2022a). The comments quoted above indicate an unequivocal intention that non-IMB work (or ‘the existing caseload’) should, at least in the short term, be displaced in favour of IMB work on the basis of government priority.

The consultation document stated that the aim was ‘to rapidly ramp up market capacity to ensure that all individuals who receive a removal notice have access to legal aid … wherever they are located.’ (

Ministry of Justice 2023b). This shows a remarkable lack of understanding of the immigration and asylum legal aid sector, including its financial position, its ongoing recruitment crisis, and the length of time it takes to train new caseworking staff (

Wilding 2023). This need for new caseworkers arose in a context where the government had expressly acknowledged (in the consultation document itself) the complexity of the new work and the very tight timescales in which it would need to be done. In other words, it was work for skilled and experienced workers, not trainees.

One of the (formerly) largest immigration legal aid providers wrote an open letter in response to the consultation, arguing that a 15% increase on existing rates amounted to ‘fiddl[ing] around at the edges of a massive and ever-growing legal aid representation gap.’ (

Duncan Lewis Solicitors 2023). The letter pointed out that, even taking inflation (on the Consumer Price Index) from 2012 to 2023, the hourly rate should have risen from £52 to £78 per hour, with a much larger increase had fees risen in line with inflation since the last fee increase in 1996 (and had they not been cut by 10% in 2011). Instead they explained that, ‘As a result of these hourly rates, and other structural problems with the civil legal aid system, the Firm’s controlled legal aid work operates at a loss’ and this had gone beyond the point where it became ‘financially unviable’ (

Duncan Lewis Solicitors 2023).

The letter stated that the firm would be ‘unable to provide legal services to people facing removal under the Illegal Migration Bill at anything like the scale that will be required’ (

Duncan Lewis Solicitors 2023). If arrivals continued at the same rate as in 2022, more than 45,000 people per year could face immediate detention, with only eight days to bring a legal challenge to their removal from the UK. This was in a legal aid context where only 35,646 immigration and asylum legal aid cases were opened in total in England and Wales in the year to 31 August 2023.

Public Law Project’s consultation response (

Public Law Project 2023) pointed out that the change would ‘create perverse incentives for providers to undertake Illegal Migration Act work to the detriment of other work, such as assisting clients with initial asylum claims in the backlog.’ The particular salience of this, in the context of the consultation, was set out in Migrant Children’s Legal Centre’s response: a successful outcome on the ‘IMA-work’ would mean the individual was re-routed into the mainstream asylum determination system, where they would be unlikely to be able to access legal representation at the unenhanced fee rate, meaning ‘any investment made by the government in the IMA work would be for nothing’.

18The government’s response in September 2023, post-consultation, paid lip service to the need to ‘respect due process under the rule of law and ensure there is timely and effective access to justice, which is the foundation of fairness in our society.’ (

Ministry of Justice 2023a) In contrast to the overwhelmingly anti-lawyer rhetoric coming from the government during that period, the response document acknowledged ‘their professionalism, commitment and expertise’ and their ‘invaluable… input to this process’ (

Ministry of Justice 2023a). Yet despite the reasoned and costed responses which argued against increasing fees for IMA work alone, and against the 15% figure, the decision was to proceed exactly as set out in the proposal:

19… as the IMA is a top priority for the Government and given the expected and unprecedented demand and timescales that the IMA will bring, the Government intends to raise fees for IMA Work only, as was consulted upon. The current hourly rates and fixed fees for immigration and asylum work under the Regulations will remain unchanged.

In other words, the rest of the asylum system was to be proactively deprioritised in favour of diverting the limited legal aid capacity, rather than taking any action to increase it, in direct defiance of the Lord Chancellor’s statutory duty under LASPO Act 2012, s1 to secure the availability of legal aid for asylum cases (in England and Wales).

8. 2024 Onwards and Concluding Remarks

The core argument in this article is this: the state creates an asylum legal desert (1) by failing to create conditions which support provision, failing to intervene in the shortage or collapse of provision, and deliberately incentivising diversion of capacity to other kinds of work; (2) by creating additional legal need in the form of in-case demand, for example through the Streamlined Asylum Procedure, detention policies, the new work required by NABA and IMA, and the age assessment policies and practices; (3) by the spatial arrangement of this legal need in areas with no legal provision.

We can observe the first two of these also in other areas of social welfare law, insofar as the state creates legal rights but withdraws the means to access them (i.e., funded legal advice) through cuts to the scope of legal aid, the fees paid, the procedure rules which create barriers to access, and failure to intervene when there is evidence of crisis. In other social welfare areas of law, however, the state is less (directly) responsible for the spatial organisation of legal need, as compared with its control of this in the asylum system.

Creating more demand through law, policy and practice multiplies the disadvantage to people in desert and drought areas. At the time of writing, the Differentiation and Priority Removal Notices in NABA have been abandoned, the Streamlined Asylum Procedure continues in a different form, but the detention provisions from the IMA remain in force, and there is overwhelming (Potential Client and In-Case) demand in the appeals system. As of December 2024, there were 41,987 asylum appeals waiting in the (UK-wide) Tribunals system, increasing dramatically from Quarter 2 of 2023–24 (i.e., July 2024) as the Home Office resumed decision making and the refusal rate increased (

Lenegan 2025). An appeal success rate of 46%, despite the serious disadvantage of the lack of appeal representation,

20 suggests that much of this is failure demand caused by flawed Home Office decision making.

In England and Wales, the consequence of legal aid unviability has been a substantial shift of providers’ capacity from legal aid work into privately paying cases or grant-funded projects, from asylum work into asylum-adjacent public law work (both aimed at cross-subsidy) and from appeals work into other parts of the asylum process (to limit financial losses). In Northern Ireland, the survival strategy has been simply not to deploy lawyers as immigration and asylum specialists at all. Anecdotal accounts suggested it was easier in 2023 to find a lawyer to challenge a notice of liability for removal to Rwanda than to find one to take on an in-country asylum appeal once removal to Rwanda was avoided. As set out in the section on The three legal aid systems, above, with an overall deficit of at least 57% in England and Wales and an appeals-stage deficit of at least 78% for Northern Ireland, this is a picture of the respective supply sides being unable to meet either the extent or the type of demand for their work.

I have already argued above that remote access is no solution to geographical shortages in a context of overall lack of capacity. Yet the true consequence of remote access may in fact be worse than simply a non-solution. In the absence of any jurisdiction-wide triaging system which requires the most complex and urgent cases to be prioritised, remote access may simply increase the demand-side competition within a country-sized Floating Catchment Area (

Shen 1998;

Luo and Wang 2003;

Clark 2024). A Floating Catchment Area is one in which the supplier is not bound to a geographical area, and that supplier may be the only one for residents of more than one geographical area, but where not all potential users have equal access in reality.

In a context where suppliers are paid the same for all cases of a particular type, the simplest cases are inherently more attractive; the higher the likely in-case demand for any potential client, the less likely they are to be accepted as a client. The in-case demand can be at least estimated in advance by the case type (asylum application, appeal or settlement application at the end of refugee leave) and the individual’s country of origin, with certain nationalities overwhelmingly likely to obtain asylum. That enables the less scrupulous, or more ‘incentive responsive’ providers (

Wilding 2021) to take on high volumes of the kinds of case which might make profit, reducing the availability of those case types as cross-subsidy for those who also take on the more complex work.

There are two possible solutions to this geographical crisis in access, which should operate concurrently: the first is simply to make it viable—both financially and administratively—for lawyers to undertake the work and rely on private firms and law centres to expand into new geographical areas. Financial viability has to be assessed in line with retention-level salaries: where do the lawyers go who leave the legal aid sector, what do they earn there and what would it have cost to retain them in the legal aid sector? It also requires a period of building trust that the government will not simply change asylum policy again and leave them with financial liabilities, newly trained staff and no work, before organisations are likely to be willing to risk expanding.

The second is to adopt (in England, Wales and NI) and leverage (in Scotland) a mixed model which includes not only the current provider organisations but also centres funded on a non-market model, operating as academies to train new immigration and asylum caseworkers, as well as being supported to locate to new areas of significant need without bearing the financial risk.

The overarching conclusion, however, is that legal aid cannot be an afterthought. The consultations around the IMA-generated legal work explicitly accepted that a functioning immigration and asylum policy needs legal aid lawyers. Asylum policy needs to be shaped to reduce failure demand, while legal aid policy needs to be funded and designed (including by reducing unpaid administrative burdens) so as to pay for the provision that is needed, with careful thought and intervention dedicated to removing the spatial inequalities in access to (legal) justice. This article aims to offer an indication of how, in future policy development, that might be done.