1. Introduction

Energy market manipulation was defined as intentional (or even “accidental”) actions carried out by natural or legal persons to distort the normal functioning of energy markets in their favor, or which merely have the potential to distort the market (Art. 2, point (2), Regulations (EU) No 1227/2011). As elaborated in the subsequent sections, the European legislator has opted to sanction even the possibility of a behavior that distorts the energy market, the existence of an outcome not being a prerequisite for the existence of the act.

The national regulatory authorities in Romania and the other member states of the European Union continuously monitor and regulate energy market activities with the objective of preventing and sanctioning market manipulations. These penalties may include financial sanctions such as fines, which have been observed to be increasing. Furthermore, trading restrictions and criminal prosecution may be imposed on individuals engaged in manipulation activities. This regulatory framework is codified in the respective national legislation of each member state of the European Union.

Manipulative transactions distort the prices and volumes of energy in the market, misleading other market participants who, without manipulative behaviors, would undoubtedly have behaved differently in those markets. In general, manipulative transactions in the European Union are treated as misdemeanors to severe crimes, and regulators are actively involved in monitoring and enforcing regulations to maintain the integrity and confidence of energy market participants. In a reference study (

Anstey and Fannon 2023), the authors evaluate the role of REMIT as a tool for controlling manipulative behaviors in the energy market, underlining the increasing control exerted by regulatory authorities, with regulation being the primary mechanism that prevents and sanctions such behaviors. Perhaps related is the fact that the jurisprudence, both at the European level and at the level of the member states, is poor in case decisions, which, we could say, denotes a lack of involvement in monitoring and sanctioning the behavior of manipulating the energy market (

De Hauteclocque and De Almeida 2024).

On the other hand, as some authors note (

Cohen et al. 2018, p. 181), “Market manipulation can take many forms, and it is impossible to provide an exhaustive list of the types of manipulation. There are doubtless future and unforeseen cases in which ingenious new forms of manipulation will appear.”

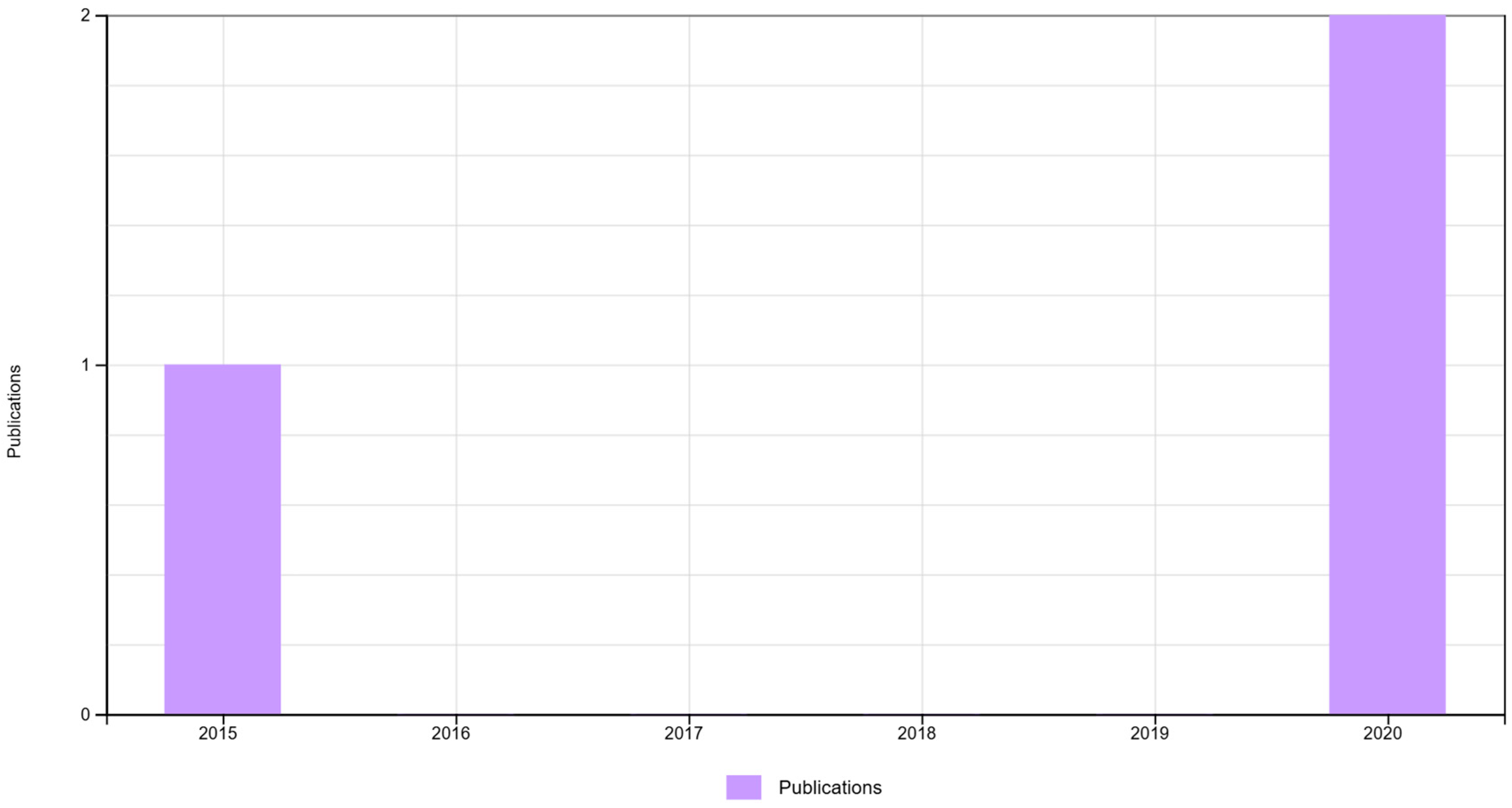

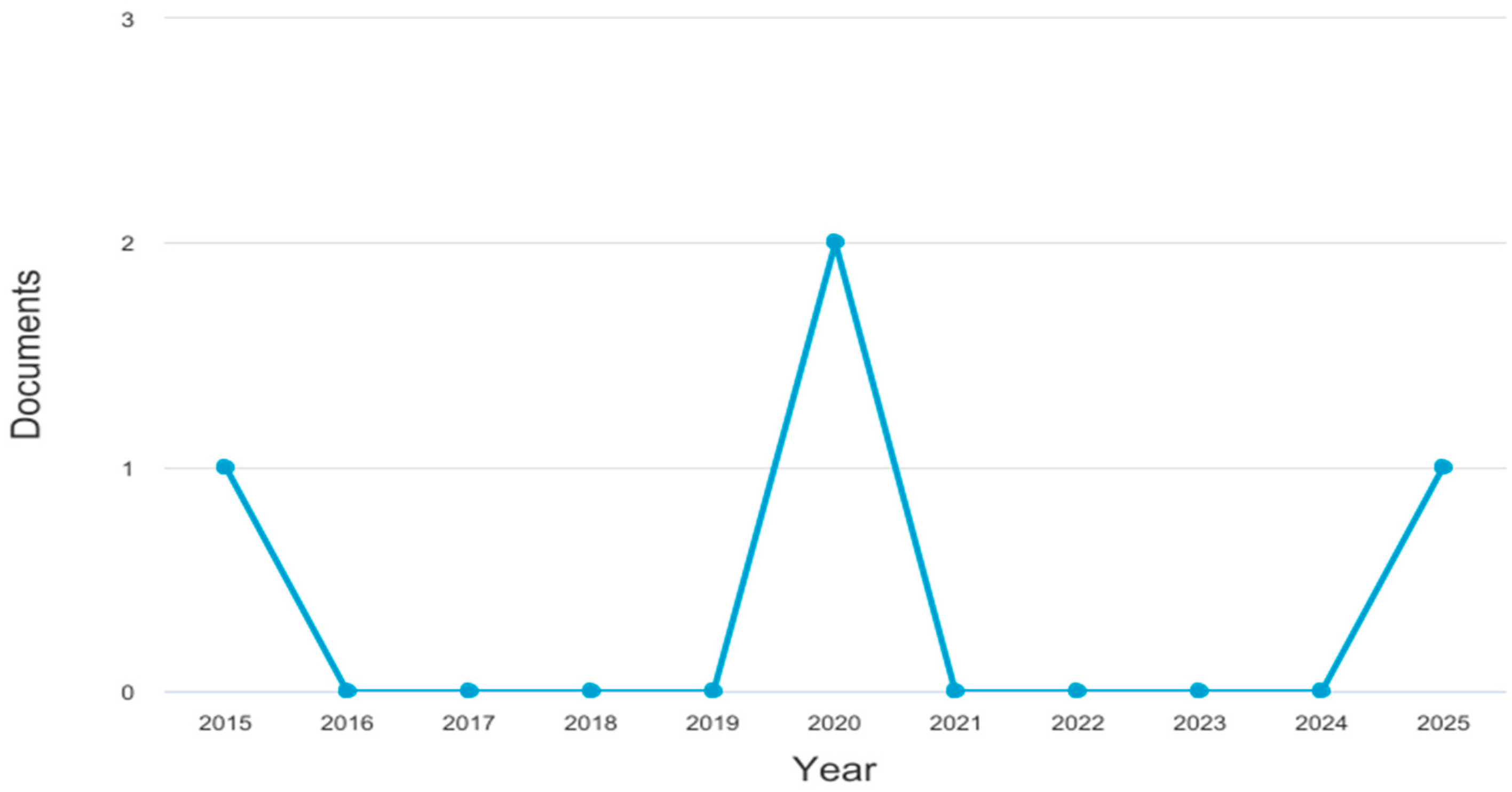

Therefore, an analysis was conducted on the extant literature on the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases, using the following keywords: “energy market,” REMIT”, and “market manipulation” (see

Appendix A). The absence of in-depth doctrinal and comparative analyses is notable. These analyses should examine the sanctioning frameworks under the Regulation on the Internal Market (REMIT). They should also examine the transformation of those sanctioning frameworks under REMIT II.

The extant scholarship on this subject has focused on either the economic or technical dimensions of energy market surveillance or general competition law principles. A paucity of studies has been conducted that analyze the following, and they will therefore be the focus of this study:

The legal framework of the revised sanctioning regime is herein presented.

The present study will examine the degree of cross-border enforcement convergence.

The present study explores the legal efficacy of soft law instruments, such as the guidelines established by the ACER.

This paper addresses the underexplored intersection of regulatory enforcement, harmonization, and legal interpretation, contributing to doctrinal EU law and the field of energy regulation.

Thus, the research objective of this work is to critically evaluate the evolution of the European regulatory framework on energy market manipulation, focusing on the legal, procedural, and enforcement transformations introduced by Regulation (EU) No. 1106/2024 (REMIT II), and to assess their effectiveness in ensuring a harmonized, proportionate, and dissuasive sanctioning regime across EU Member States.

To achieve this objective, the research team developed two hypotheses and two research questions.

H1. The introduction of REMIT II (Regulation No. 1106/2024) has been shown to significantly improve the legal precision and harmonization of sanctioning mechanisms for energy market manipulation across EU Member States.

H2. Despite the non-binding nature of ACER’s guidelines, they have been shown to exert a measurable influence on the enforcement strategies employed by national regulatory authorities. This influence has been demonstrated to promote greater consistency in the application of REMIT provisions.

The following research questions have been posed: Q1: To what extent do the amendments introduced by REMIT II (Regulation No. 1106/2024) enhance the legal clarity and uniformity of the sanctioning regime for energy market manipulation across EU Member States? Q2: What role does the European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) play in facilitating consistent enforcement of REMIT provisions, and how effective are its non-binding guidelines in influencing national regulatory practices?

The research questions formulated address a relevant issue in contemporary scientific discourse. The specialized literature is relatively limited in terms of a comprehensive treatment of these aspects. This limitation confers a valuable character upon the study, as it responds to a significant lack of existing theoretical research.

3. REMIT Framework

3.1. Legal Aspects of REMIT

According to Article no. 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), regulations are defined as possessing general applicability, binding force in their entirety, and direct effect across all Member States (EUR-Lex, consolidated version of the TFEU).

The extant literature, as evidenced by the present study’s findings, has demonstrated that scholarly commentary has been shown to underscore the fact that regulations, in their capacity as instruments of EU law, function as legislative norms and constitute substantive law (

Ernst Sensburg 2022, p. 37). It is important to note that Ernst

Sensburg (

2022) underscores that regulations do not necessitate domestic ratification or transposition. Moreover, the study indicates that these regulations do not permit Member States to alter their applicability or substance through national legislation. Conversely, Member States must enforce regulations precisely, without deviation, while implementing supplementary measures that neither modify nor restrict the regulation’s scope.

Cărăușan (

2012, pp. 184–86), on the nature of regulations under Article 288 TFEU, asserts that the notion of total and full direct effect encompasses both the objectives and the prescribed means for their attainment, thereby rendering the regulation a fully realized normative act. This interpretation aligns with the jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice, which, through a series of landmark decisions (notably Cases C-43/71, Politi v Ministero delle finanze; C-84/71, Marimex v Ministero delle finanze; C-34/73, Fratelli Variola Spa v Amministrazione delle finanze dello Stato; C-65/75, Tasca) has established a mandate for Member States to refrain from obstructing the inherent direct applicability of regulations. Furthermore, the Court has categorically rejected the prospect of incomplete or partial implementation of regulations by Member States, as underscored in the ruling of Case C-39/72, Commission v. Italy (1973).

Regulation (EU) No. 1227/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the integrity and transparency of the wholesale energy market

1 states, from the content of his Preamble, at the Recital (1) that “It is important to ensure that consumers and other market participants can trust the integrity of electricity and gas markets, that prices on wholesale energy markets reflect the balanced and competitive interaction between supply and demand, and that no profits can be made through market abuse”, and at the Recital (2) (Regulation (EU) No. 1227/2011) it is mentioned as the Objective—to enhance the integrity and transparency of wholesale energy markets. So, from the beginning of this act of European legislation, the legislator stressed the importance of trust in the integrity of markets. Also, the Recital (13) (Regulation (EU) No. 1227/2011) underlines the European norm that “The manipulation of wholesale energy markets involves actions by persons who artificially make prices at a level that is not justified by market forces of supply and demand, including the effective availability of production, storage or transport capacity and actual demand. Market manipulation cases include the issuance and withdrawal of false trading orders; the dissemination of false or misleading information or rumors through the media, including the Internet, or other means; the purposeful provision of false information to undertakings, including price assessments or market reports, resulting in misleading market participants who make decisions on the basis of price assessments or market reports; and intentionally leaving the wrong impression that the availability of electricity generation capacity, natural gas volume or transmission capacity would be different from technically available capacity if this information affects or may have consequences on the price of wholesale energy products. Manipulation can also take place and can have consequences on a cross-border basis, on the electricity and gas market and the financial and commodity markets, including the market for trading emission allowances” (Recital 13, Regulation (EU) No. 1227/2011). Examples of cases of manipulation are described as the conduct of a person or persons acting in concert to ensure a dominant position on the supply or demand of a wholesale energy product, having the effect of directly or indirectly fixing the price or creating other unfair trading conditions; and the offering, buying or selling of wholesale energy products for the purpose or intent of, or which result in misleading market participants acting based on reference prices (Recital 14, Regulation (EU) No. 1227/2011).

National regulatory authorities shall apply this Regulation in the Member States. To this end, those authorities must have the necessary investigative powers to perform this function effectively, which shall be exercised by national law.

For Regulation, Article 2, item 2, provides that it represents “market manipulation” as:

- (a)

making any transaction or issuing any trading order with wholesale energy products

- (i)

which offers or is likely to give false or misleading indications as to the supply, demand or price of wholesale energy products;

- (ii)

which establishes or attempts to develop, by the action of one or more persons acting in concert, the price of one or more wholesale energy products at an artificial level, unless the person who carried out the transaction or issued the order considers that the reasons which led to it doing so are legitimate and that the transaction or order is in conformity with the market practices admitted to that wholesale energy market; or

- (iii)

using or attempting to use a fictitious instrument, or any other form of scam or artifice, which transmits or is likely to transmit false or misleading messages concerning the supply, demand or price of wholesale energy products;

and/or

- (b)

the dissemination, through the media, including the Internet, or by any other means, of information that provides or is likely to provide false or misleading messages about the supply, demand or price of wholesale energy products, including the spread of rumors and the dissemination of false or misleading information, in a context in which the person who disseminated the information knew or should have known that the information was false or misleading. Where information is disseminated for journalistic purposes or as artistic expression, such dissemination of information shall be assessed taking into account the rules applying to freedom of the press and freedom of expression in other media, unless

- (i)

such persons derive, directly or indirectly, benefit or benefits from the dissemination of the information in question; or

- (ii)

the disclosure or dissemination of that information is intended to mislead the market about the supply, demand for or price of wholesale energy products. The act is expressly prohibited by the provisions of Article 5 of the Regulation

2, and it is relevant to point out that REMIT prohibits and implicitly sanctions even attempts to manipulate the market (Art. 2 par. 3, Regulation (EU) No. 1227/2011).

Energy market manipulation is an important and sensitive subject, given its impact on prices and the stability of energy markets. REMIT (Regulation on Market Integrity and Transparency) is a European regulation aimed at preventing energy market manipulation, thus protecting consumers and ensuring the proper functioning of energy markets in the European Union.

From the analysis of the text above, we can conclude that REMIT prohibits energy market manipulation, which includes practices such as the following:

Insider trading: The use of non-public information that could influence market prices to gain an advantage in the market. For example, an energy market player could use confidential information about production capacities or consumer requirements to manipulate prices.

Price manipulation: This includes any practice by which a market participant could artificially influence the price of energy, for example, by trading large volumes of energy in a way that causes abnormal price fluctuations.

Examples of energy market manipulation that could breach REMIT include the following:

Front-running: The practice where a market player knows about future transactions and profits from them.

Pump and dump: Creating an artificial increase in price through speculative transactions, followed by a massive sale to make profits.

Wash trading: Buying and selling the same amount of energy to create an illusion of liquidity and manipulate market perception.

National regulators are responsible for monitoring and investigating suspicious behavior in the energy market. In the European Union, the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) plays a key role in collecting and analyzing market data and in reporting possible breaches of the REMIT Regulation.

Where market manipulation practices are identified, authorities can impose significant fines and administrative sanctions. Market participants may also be required to return profits obtained from such illegal activities.

3.2. Comparative Overview of National Legislation

At the level of EU member states, given that REMIT in its initial version did not provide for any specific value of administrative fines but only some individualization criteria, EU states have implemented certain amounts, or rather limits, of them at the national legislative level.

Thus, in Spain, for example, there is a maximum of 10% of the annual turnover from the last fiscal year for electricity (5% for natural gas), regardless of its origin, i.e., the source of their origin (regulated activities or not) is irrelevant. It also establishes a clear minimum limit for the fine, EUR 600,001, which can be reduced depending on the reduced degree of gravity or mitigating circumstances (including in case of recognition of the act, the amount is reduced by 20%). At the same time, the prohibition of profit is a rule that is specified in the natural gas sector, but not in the electricity sector, as well as in the general rules of administrative procedure (Law no. 24/2013, of 26 December, of the Electricity Sector).

Also, in Italy, under art. 22 par. (5) of Law no. 161/2014, the Authority shall impose administrative pecuniary sanctions of between EUR 20,000 and EUR 5 million on persons who engage in one of the market manipulation behaviors defined in Article 5 of Regulation (EU) No. 1227/2011. Under Article 11 of Law No. 689/81—Sanctions Regulation, the quantification of the sanction is carried out by applying the following criteria: the severity of the violation; the work carried out by the company to eliminate or mitigate the consequences of the violation; the economic conditions of the company, etc.

In France, if the infringement does not constitute a criminal offence, the authority shall impose a pecuniary penalty, the amount of which shall be proportionate to the seriousness of the infringement, the situation of the person concerned, the extent of the damage and the benefits resulting from it. This amount may not exceed 3% of the value of the turnover excluding tax during the last closed financial year, increased to 5% in the event of a subsequent infringement of the same obligation in the event of failure to comply with the obligations to transmit information or documents or the obligation to ensure access to accounts, as well as to the economic, financial and social information provided for in Article L.135-1 (Code de l’énergie). In the absence of activity allowing this ceiling to be determined, the amount of the penalty may not exceed EUR 100,000, increased to EUR 250,000 in the event of a subsequent infringement of the same obligation. In the case of other infringements, it may not exceed 8% of the value of the turnover, excluding taxes, during the last closed financial year, increased to 10% in the case of a subsequent infringement of the same obligation. In the absence of an activity allowing the determination of this ceiling, the amount of the penalty may not exceed EUR 150,000, increased to EUR 375,000 in the case of a subsequent infringement of the same obligation.

In Bulgaria, if not subject to a more severe penalty, a pecuniary penalty of up to 10% of the total turnover of the person in the previous financial year shall be applied. Where there is no turnover, the penalty shall be in the amount of BGN 10,000 to 100,000 (Art. 224d, Energy Law). A natural person who infringes or commits acts with the aim of infringing Articles 3 and 5 of Regulation (EU) No. 1227/2011, if not subject to a more severe penalty, shall be punished by a fine of BGN 5000 to 50,000. When determining the amount of the pecuniary penalty provided for in paragraph 1 and the fine provided for in paragraph 2, the commission shall take into account the gravity and duration of the infringement, as well as the mitigating and aggravating circumstances. The specific amount of the sanction and fine is established by the commission through a methodology it has adopted, which is published on its website.

In Romania, the limits of administrative sanctions that can be imposed for acts falling under the scope of Article 5 REMIT are established by Law no. 123/2012 on electricity and natural gas. Thus, failure by market participants to comply with their obligations under the provisions of art. 3 para. (1)–(2) let. (e) and art. 5 of Regulation (EU) no. 1227/2011 was sanctioned with a fine in the amount of between 5% and 10% of the turnover of the year preceding the application of the sanction.

Furthermore, although Regulation REMIT II is relevant to the European Economic Area (EEA), it has not yet been incorporated into the EEA Agreement. Because energy markets are interconnected, regulatory harmonization is necessary to ensure effective policy implementation.

Regarding the Norwegian legislation, it is relevant to note that there has been no amendment to the legislation in order to implement the REMIT II Regulation. Accordingly, pending the formal incorporation of REMIT into the EEA Agreement and Norwegian law, Norway has established provisions on insider trading and market manipulation that align with Regulation (EU) 1227/2011 (REMIT I). This alignment is reflected in Regulation no. 1413 of 24 October 2019, which pertains to network regulation and the energy market (NEM 2019, Forskrift nr. 1413 om nettregulering og energimarkedet). The provisions in NEM are designed to align, to the best extent possible, with those in REMIT I, within the context of the Norwegian Energy Act.

The National Regulatory Authority of Norway (RME—Regulerings Myndighet for Energi) is the entity empowered to mandate the end of unlawful practices and the imposition of a coercive fine. Furthermore, RME reserves the right to impose administrative penalties for the infringement of certain provisions (NEM 2019, sct.-3):

The act of prohibiting market manipulation, as well as any attempts to manipulate the market, is hereby declared to be strictly forbidden.

The act of prohibiting the practice of insider trading is of particular relevance in this context.

The obligation to disseminate information that has been obtained through legitimate channels.

Individuals engaged in professional transactions are obligated to establish and maintain effective arrangements, systems, and procedures for the identification of potential breaches of the prohibitions on insider trading and market manipulation. These individuals are also required to notify the RME of any such breaches.

Criminal sanctions may be imposed in the event of substantial violations of the aforementioned provisions (NEM 2019, sct. 8-4).

The following table (

Table 1) summarizes the comparative study, which aims to enhance our understanding of the various approaches to sanctioning limits and aggravating factors.

The absence of substantive limits on the design of administrative sanctions in the REMIT I regime resulted in disparities across Member States’ national legislations, as highlighted by the comparative synthesis from

Table 1. This divergence reflects the broader doctrinal tension between procedural autonomy—the prerogative of Member States to tailor sanctions to their specific market contexts—and the imperative to ensure the effectiveness of sanctions as a deterrent against market abuse.

As the literature emphasizes (

Roccati 2015;

Galetta 2010), procedural autonomy signifies the capacity of EU member states to regulate their own procedural laws. However, this autonomy is not absolute and is subject to the requirements of EU law, particularly the principles of effectiveness and equivalence.

Procedural autonomy does permit a certain degree of flexibility in sanctioning regimes. However, Article 18(2) REMIT nevertheless circumscribes this autonomy by mandating that sanctions must be effective, proportionate, and dissuasive. In determining the appropriate sanction, it is essential to consider the severity of the infringement, the harm caused to consumers, and the illicit gains derived from the violation.

The European legislator aims to strike a thoughtful balance by acknowledging the procedural autonomy of Member States in establishing their own frameworks for sanctions. This model encourages a more consistent approach to sanctions, recognizing that variations or insufficient measures could potentially hinder REMIT’s overarching goal of achieving uniform deterrence against market manipulation. Thus, the absence of full harmonization may be viewed not solely as a reflection of regulatory flexibility but as an opportunity to navigate the complexities of decentralized enforcement while addressing the collective aspiration for efficacy in the regulatory landscape. Member States are empowered to develop tailored criteria for individualizing sanctions, fostering an environment where both local context and broader objectives can harmoniously coexist.

3.3. European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER)

As previously mentioned, REMIT is a sector-specific framework that aims to provide increased transparency and to achieve effective market surveillance in the wholesale electricity and gas market. The EU has established a system of oversight for the trade of electricity and gas, with the ACER serving as the designated authority for market surveillance within the European Union.

ACER collects data on bids and carries out initial analysis to detect insider trading and market manipulation. To enable this, market participants must register, report data and publish inside information. The prohibition against insider trading, market manipulation and attempted market manipulation applies to all market participants initiating transactions and orders to trade in one or more products on the wholesale electricity or natural gas market.

ACER was established in March 2011 by law as the third energy package, as an independent body to promote the integration and completion of the internal energy market. By stimulating cooperation between national regulatory authorities (NRAs), ACER ensures that integrating national energy markets and implementing legislation in the Member States aligns with EU energy policy objectives and regulatory frameworks. To better understand the Regulation, ACER has developed over time a Guide, which is already in its 6th edition (

ACER 2021).

Thus, the central element of the definition of market manipulation is the likely effect that certain types of conduct have on the demand for, supply of or price of wholesale energy products. The situation is different as regards attempted manipulation, where the central element is the intention underlying the conduct, even if the attempt was unsuccessful.

Therefore, according to the definition of “market manipulation”, “what matters is whether the conduct gave or was likely to provide false or misleading signals about the supply, demand or price of energy products” (Article 2 (2) (a) point (i), Article 2 (2) (a) (iii) and Article 2 (2) (b) of the REMIT) or “have guaranteed the artificially produced price of them” (Article 2 (2) (a) (ii) of the REMIT) (

ACER 2021, p. 70).

This definition does not include any element of intent. In other words, whether the behavior is intentional or not is irrelevant to qualify it as an infringement of Article 5 of the REMIT in the form of “manipulation of the market. As a result, a simple erroneous trading activity may end up being manipulative” (

ACER 2021, p. 70).

By Article 2(2)(a) of REMIT, it is sufficient that conduct is “likely” to give false or misleading signals as to the demand, supply or price of a wholesale energy product and is classified as a breach of Article 5 of REMIT in the form of market manipulation. NRAs do not need to demonstrate that false or misleading signals about wholesale energy products’ demand, supply, or prices have been sent in such cases. In the circumstances of a given case, it is sufficient that the conduct was likely to give these false or misleading signals (

ACER 2021, pp. 70–71). Moreover, the ACER Guidance states, “it is not necessary to show that the suspected person knew that they were violating REMIT. In other words, the deed exists even if it is done ‘by mistake’”. Compared to the above, we note aspects retained in the

ACER (

2021, pp. 73–78)—“to be likely to give or attempt to give false or misleading signals”. False or misleading signals given by certain orders/transactions may lead participants to make trading decisions based on false or misleading information about supply, demand or prices and, therefore, act in a way they would not have considered without manipulative behavior.

When perceived or suspected by other market participants, these orders/transactions may also create distrust of market integrity and, for example, may negatively impact liquidity.

The following orders/transactions examined in their context and light of the trading strategy of market participants could, for example, be considered inauthentic:

Orders/transactions that are erroneous and, therefore, do not reflect a genuine interest in buying or selling at the price considered;

Orders/transactions that are not placed/concluded with a real interest to buy or sell energy but rather with other interests (for example, influencing the behavior of others, influencing price settlements, influencing the price of other products, circumvention of market rules, benefiting positions in other contracts, tax evasion, profit/loss sharing, circumvention of accounting rules, money transfer between market participants);

Orders are placed without the intention of executing them.

If inauthentic orders/transactions send or are likely to send signals to the market, these signals are false or misleading and violate the prohibition of market manipulation. When assessing attempts to manipulate the market by point (a) of Article 2 (3) of the REMIT, NRAs should focus their assessment on whether orders/transactions were intended to give false or misleading signals (whether they gave these signals), because proof of intent is the critical element for this type of violation. A few elements need to be considered by the NRA when assessing whether orders/transactions have given false or misleading signals, whether orders/transactions were likely to provide false or deceptive signals, or whether orders/transactions were meant to give false or misleading signals.

The Guide to the previous section finds that “Article 2 of REMIT prohibits any trading activity that provides a false fact or misleading signals and any trading activity that is likely to give false or misleading signals”.

Thus, for an act of manipulation to occur, it is sufficient that the trading activity has the potential to give false and misleading signals, and it is not mandatory to fulfil this desideratum.

3.4. Characteristics of Market Manipulation

To provide specific guidance points, ACER has drawn up an

ACER (

2019) on applying Article 5 of REMIT.

According to the preamble, this contains the general direction on the interpretation of the application of the definitions referred to in Article 2 of REMIT, and provides examples of types of behavior that may meet the definition of market manipulation provided for in Articles 2 (2) and (3) of the REMIT.

Concerning the phrase wash-trade, ACER notes that it refers to the act of a market participant entering into agreements for the sale or purchase of an energy product, where there is no change in the beneficial interests or market risk or where the beneficiary interest or market risk is transferred between the parties acting in concert or collusion. What is also noteworthy, and we consider it relevant to point out, is that a transaction is likely to qualify as market manipulation under REMIT to the extent that it provides or is expected to give false or misleading signals and/or to provide or attempt to secure the price of wholesale energy products at an artificial level. Emphasis is also placed on the fact that REMIT does not require proof of intention in assessing a washing transaction. Therefore, it is unnecessary to demonstrate that market participants knew they were in breach of REMIT. Note that it even provides concrete examples of market manipulation situations, and to clarify the matter, we will present such an example for the practical understanding of the act of wash-trade A-B-A, which is the most common (

ACER 2019):

By mutual agreement, two market participants place a purchase and sales order to produce wholesale electricity on a trading venue almost at the same time for the same or similar amount and for the same or similar price (match). Then, after some time, the same parties almost simultaneously enter orders in the reverse direction that fit at a price that may be the same or different from the first transaction.

Interpretation: This type of conduct refers to concluding agreements for selling or purchasing an energy product. The transfer of beneficial interest or market risk occurs only between parties (two or more) acting in concert or collusion.

Considerations:

In these washing transactions, prices may differ between the two clearing transactions involving market participants.

More than two market participants may also be involved (i.e., ‘B’ can be interpreted as a chain of market participants).

Article 2 (2) (a) (i) of the REMIT assumes that transactions or orders which give or are likely to provide the market with false or misleading signals as to the supply, demand or price of wholesale energy products constitute market manipulation.

These transactions can give false or misleading signals to the market regarding the supply, demand or price of a wholesale energy product. Indeed, by providing other market participants with a misleading representation of liquidity, price, and price volatility or by creating an expectation of potential changes in available supply or demand, a washing trade may cause (or lead) other market participants to act in a way that they would not have done in the absence of manipulative transactions.

Wash transactions may create false or misleading signals about the liquidity of a particular product. This false or wrong impression could cause other participants to make trading decisions based on misleading information. This practice also excludes other markets, and participants are deprived of the ability to match their orders, thereby reducing competition. This type of transaction can also create false or misleading market signals about the product’s price, leading market participants to make erroneous trading decisions based on inaccurate information. They can also affect price volatility (in particular when they differ from the prevailing market price) and generate market uncertainty regarding price levels. This can lead other market participants to engage in more conservative strategies (changing or postponing decisions), potentially reducing liquidity.

At the same time, transactions with unusual volumes are likely to be interpreted by market participants as reflecting changes in the fundamentals of the market (for example, changes in the unavailability of generation units or forecasts) that are not widely known by all market participants. It may create distrust in the market and cause (or could lead) other market participants to act in a way that they would not have considered in the absence of those transactions.

In addition, transactions of wash-trade, when perceived or suspected by other market participants, may create distrust of market integrity, causing investors to feel that orders in the order book are not representative of the actual market situation, thus negatively influencing liquidity. The likelihood of sending false or misleading signals can be inferred in several ways, for example, from the percentage of average daily/hourly volumes, volume comparisons with previous days or other relevant periods, and the average transaction size or divergence from prevailing market prices.

The specific market circumstances in which the washing transactions are executed must be taken into account. For example, a washing transaction in an illiquid market can increase the likelihood of the aforementioned adverse effects by creating an illusion of liquidity in a product, which should be considered sufficient to trigger the possibility of sending false or misleading signals.

According to REMIT, these transactions, ‘wash trades A to B to A’, are prohibited and considered manipulative because of how they are carried out. Taking into account that the main objective of REMIT is to maintain integrity and transparency in energy markets and to discourage and sanction manipulative practices that may distort the proper functioning of the market, it establishes that such manipulative practices are prohibited and sanctioned, as they may affect the integrity and transparency of the energy market. Such transactions create the illusion of actual business activity without generating a net change in position or ownership of the traded asset (

ACER 2017).

When these wash trade transactions are carried out in the energy market, they can have a manipulative impact on prices or the perception of energy supply and demand. By creating an appearance of intense market activity, wash trades can lead to a distortion of perception about market volatility and also influence the decisions of other participants, all of which lead to misleading both other market participants and entities that analyze the market in terms of demand, supply or direction of prices, affecting market indicators artificially.

In a washing transaction of type A-B-A in the electricity market, where the same participant makes both the purchase (A) and the sale (B) of the same amount of energy or an equivalent quantity, there are specific ways in which the price and quantity of energy can be influenced (

ACER 2017):

Impact on price: The transaction of type ‘wash trades A to B to A’ can create a false impression that there is a higher demand and offer on the market than in reality. By placing washing transactions at specific prices, participants can artificially influence the market price up or down, depending on their goal. Suppose this transaction is carried out at the same or very close price. In that case, it may indicate an apparent interest in trading, which could influence other participants to react to this behavior differently from how they would have responded if the transaction had not been concluded. Therefore, this has led to artificial price fluctuations, creating the impression that there is more demand or supply than there is and may create confusion about the actual supply and demand on the market. This confusion can affect confidence in market fairness and transparency.

Impact on the quantity traded: In the case of transactions of type ‘wash trades A to B to A,’ although the amount of energy is ‘theoretically’ traded, this being included in the total amount of energy traded on the market, as in reality there is no net exchange of amounts of energy (volume ‘0’), these transactions do not contribute to the total amount of energy in the market, resulting in an unreal value of it. Thus, these transactions do not contribute to the actual energy traded on the market. Still, they created the illusion of a more significant amount of trading and, implicitly, the impression of intense commercial activity. The apparent increase in volume transacted has influenced the perception of energy demand and supply, thus affecting its prices.

At the same time, such transactions have created an appearance of a more significant number of transactions than in reality. This led to an artificial increase in the number of transactions, erroneously influencing the market’s perception of supply and demand. In the energy market, such transactions of type ‘wash trades A to B to A’ are considered to be prohibited or against market rules, as they distort the information available to other participants and may incorrectly affect the prices of the traded product, as well as their decisions regarding the quantities of energy in the market, thus affecting transparency and market confidence. Indeed, these transactions can lead to an unfair market environment and affect the proper functioning of the energy market. The primary purpose of such a transaction is to create a false appearance of market activity or of a larger trading volume than the one that exists, which may have a manipulative impact on prices or the perception of energy demand and supply as long as they put into play fictitious volumes of electricity, whereas in reality, there is no physical exchange.

It should be noted that the definition of market manipulation in Article 2 (2) of the REMIT does not require an examination of the intention or mood of the participating market when executing the washing transaction. Therefore, according to this article, showing that market participants knew they were violating REMIT is unnecessary. The intention to manipulate the market will only need to be demonstrated to qualify a washing transaction as an attempt at manipulation, that is to say, the conclusion of transactions to offer false or misleading signals as defined in point (a) of Article 2 (3) of REMIT.

OFGEM (

2020)

3 pointed out that it is visible that an example-based approach was instead adopted in this respect, thus creating space for uncertainty and divergent interpretations, but also provided some key features of the REMIT market manipulation regime:

Market manipulation can occur without impact on supply, demand or price;

It is unnecessary to state the intention to manipulate the market as defined in point (a) of Article 2 (2).

It must, therefore, be borne in mind that specific orders or transactions may be considered market manipulation or attempted market manipulation by Articles 2 (2) and (3) of the REMIT and prohibited by Article 5 of the REMIT, irrespective of the reason behind the orders/transactions or whatever the actual effect on the market (Market manipulation prohibition under REMIT 2013, available online at:

https://emissions-euets.com/market-manipulation-remit, accessed on 8 August 2025).

Market participants should exercise due care to ensure that erroneous transactions do not inadvertently result in outcomes that could constitute a breach of REMIT. Examples of misconduct that energy market regulators have sanctioned are the case when the French energy regulator (CRE) published two sanctions decisions adopted by its Dispute Resolution and Sanctions Committee (CoRDiS) in May 2022 (

ACER 2022), about the operational mistakes of the EDF trading subsidiary, EDFT, in October 2016 and the British case OFGEM from July 2017, regarding the incorrect de-evaluated capacity of National Grid Electricity Transmission plc (

OFGEM 2020).

The Dutch Authority for Consumers and Market (ACM) also points out that sending an order that sends an incorrect or misleading price signal falls within the definition of market manipulation. It is, therefore, important that market participants take preventive measures and that there are procedures in place to correct errors and remove incorrect or misleading signals to the market. However, if such an order is transmitted, market participants must ensure the mistake is discovered quickly and inform the market about it. Following the ACM investigation, Eneco Energy Trade (EET) has made commitments on measures aimed at preventing errors in the future and reimbursing the amount of EUR 2.4 million (

ACM 2023), which the company had gained in error due to an error in writing (the EET market trader added 0 to the price of an offer during a GTS balancing action).

From the recent analysis of the situations of sanctions applied for violation of Article 5 of REMIT (

ACER, Enforcement Decisions n.d.), we note that in 2024, the most considerable fines were imposed by national NRAs. Thus, in Spain, for example, the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC), which is the body that promotes and maintains the proper functioning of all markets, in the interest of consumers and businesses (

ACER News 2024), sanctioned Gesternova SA to the value of EUR 6 million and Axpo Iberia to the value of EUR 1.5 million for manipulating the electricity market by providing false or misleading signals regarding the supply of wholesale energy products, through behavior known as “quote stuffing” and by issuing (and also withdrawing in the case of AXPO IBERIA) inauthentic orders to be in an advantageous position to execute cross-border sales with France.

Concerning the act of market manipulation, it is worth noting that Spanish legislation criminalizes and sanctions such acts as crimes. In a recent decision, the National Court acquitted Iberdrola Generación España SAU and four of its directors, who were accused of market and consumer crimes for having designed a system to increase the price of electricity between 30 November and 23 December 2013.

Also, in Romania, at the beginning of 2024, the most significant fines were imposed by the NRA for acts falling under art. 5 of REMIT. Thus, at the beginning of 2024, the National Energy Regulatory Authority (ANRE) announced the application of cumulative fines exceeding EUR 100 million to four suppliers who had colluded to manipulate the market, with penalties ranging from 5% to 7.5% of their turnover. Notifications from the Energy market operator, OPCOM SA and ACER, triggered the ANRE investigation (

ANRE 2024a). According to the decisions, the four market participants transmitted false and misleading signals on demand, supply and price on the OPCOM Centralized Market with continuous double negotiation for Bilateral Electricity Contracts (PC-OTC) by carrying out multiple “A to B to A” wash trades related to the same electricity product, for the same volume, at different price levels. This type of transaction can transmit false and misleading signals and can seriously affect the integrity and transparency of energy markets, as they constitute orders and transactions that are not representative of the real market situation (liquidity, price, price volatility) (

ANRE 2024b).

Finally, we also mention a decision by the Dispute Resolution and Sanctions Committee (CoRDiS) of the French energy regulator (CRE) which, on 20 January 2025, imposed a fine of EUR 8 million on Danske Commodities A/S and a fine of EUR 4 million on Equinor ASA for manipulating the annual capacity auctions at the virtual interconnection point between France and Spain (PIR Pirineos) in 2019 and 2020

4.

According to the ACER guidelines, within the European Union (EU) it can be observed that, in the application of REMIT, except Romania, which set an absolute record in the value of fines applied (

ACER, Enforcement Decisions n.d.) the remaining National Regulatory Authorities (NRAs) imposed a higher number of fines in instances where the manipulation acts exhibited a cross-border nature, as opposed to those acts occurring within the respective state.

After this section, we present several provisions regarding a concept that may appear similar at first glance, but the differences are significant: market abuse. Specifically for financial markets, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union have established a regulatory framework for market abuse in the European Market Abuse Regulation—MAR (Regulation (EU) no. 596/2014)

5.

As delineated in Recital (7) (Regulation (EU) no. 596/2014), market abuse is defined as a concept encompassing illegal conduct in financial markets and should be understood as consisting of abusive use, unauthorized disclosure of inside information, and market manipulation. Therefore, an initial discrepancy arises from the implementation of these concepts. Although REMIT encompasses market manipulation and the disclosure of inside information (distinct from manipulation) as key sanctioning elements, MAR appears to refer to a whole-to-part relationship. In this regard, market manipulation is understood to be part of a much broader concept: market abuse. Nevertheless, a review of relevant European legal acts reveals a consensus that such conduct undermines the integrity and transparency of the market, irrespective of its categorization as the financial or energy market.

It is also important to note that MAR underscores the connection between the two regulations, stating in Recital (44) (Regulation (EU) no. 596/2014) that its rules complement REMIT, which prohibits the deliberate provision of false information to undertakings, including price assessments or market reports on wholesale energy products, with the intent to mislead market participants who base their actions on these price assessments or market reports. Alternatively, Recital (47) (Regulation (EU) no. 596/2014) refers to the manipulation or attempted manipulation of financial instruments, which may also consist of the dissemination of false or misleading information. This aspect is similar to the provisions of REMIT that are specific to the energy market. However, the MAR framework exclusively pertains to “acts committed with intent”, while the REMIT framework encompasses even “accidental” manipulation.

4. Challenges in Amending REMIT

In the context of a permanent concern of the EU institutions to monitor and sanction the manipulation of the energy market, but also to highlight the effects and seriousness of such acts, to discourage this type of behavior, in February 2023, the European Commission (COM) made public the proposals to amend several normative acts of the European Parliament and the Council on the electricity market, that is the proposal to amend Regulation (EU) 2019/943 and (EU) 2019/942 and Directives (EU) 2018/2001 and (EU) 2019/944 to improve the organization of the Union electricity market and the Proposal to amend Regulations (EU) No 1227/2011 and (EU) 2019/942, respectively, with the stated purpose of improving the Union’s protection against market manipulation in the wholesale market (

Council of the EU 2023).

From the perspective of this approach, it is of interest that the first Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulations (EU) No 1227/2011 and (EU) 2019/942

6 was to improve Union protection against market manipulation in the wholesale energy market. According to the text, Regulation (EU) No 1227/2011 was to be amended to increase public confidence in the functioning of energy markets and to protect the Union effectively against market manipulation attempts, the definition of market manipulation in Regulation (EU) No 1227/2011 should be adapted to include the performance of any transaction or issuance of any trading order, but also any other conduct related to wholesale energy products which (Regulation EU 2024/1106, pp. 22–23)

- (i)

provide, or are likely to provide, false or misleading indications as to the supply, demand or price of wholesale energy products;

- (ii)

fix demand or price of wholesale energy products, or is liable to fix, by a person or persons acting in collaboration, the cost of one or more products of energy wholesale at an artificial level;

- (iii)

resort to a fictitious process or any other form of deception or deceit that provides or may give false or misleading indications as to the supply, demand or price of wholesale energy products.

In such a context, a uniform and more robust framework is required to prevent market manipulation (Regulation EU 2024/1106, p. 26).

Regarding Article 2, from the perspective analyzed in this study, it was proposed to replace it with the following text:

“market manipulation” means the following:

(a) the conduct of any transaction, the issuance of any trading order or the adoption of any other conduct relating to a wholesale energy product;

(b) which offers, or is likely to provide, false or misleading indications as to the supply, demand or price of wholesale energy products.

It can be noted that the REMIT change sanctioned not just “any transaction” or “any order of trading” but expanded the area of facts that can enter under the art. 2 REMIT by sanctioning any other behavior. However, the most crucial change is the content of Article 18 of REMIT

7, the content of which was to be modified as follows manipulation (Regulation EU 2024/1106, pp. 49–50).

Article 18 is replaced by the following:

- (1)

Member States shall lay down rules on penalties applicable to infringements of this Regulation and shall take all necessary measures to ensure their implementation. The penalties must be effective, dissuasive, and proportionate, reflecting the nature, duration, and seriousness of the infringements, the damage caused to consumers, and the potential benefits derived from insider trading and market manipulation. Without prejudice to the criminal sanctions and supervisory powers of national regulatory authorities according to Article 13, they shall, by national law, confer on national regulatory authorities the power to adopt appropriate administrative sanctions and other administrative measures for infringements of this Regulation referred to in Article 13 (1). Member States shall notify the Commission and the Agency of those provisions in detail, notifying them without delay of any subsequent changes affecting them.

- (2)

Member States shall ensure, by national law and the principle of ne bis in idem, that national regulatory authorities have the power to impose at least the following administrative penalties and administrative measures relating to infringements of this Regulation:

- (a)

The adoption of a decision requiring the person concerned to put an end to the infringement;

- (b)

The recovery of the profits derived from the infringement or losses avoided therein, in so far as they can be determined;

- (c)

Issuing warnings or public announcements;

- (d)

Adoption of a decision imposing periodic penalty payments;

- (e)

The adoption of a decision imposing administrative pecuniary sanctions.

As regards legal persons, maximum administrative pecuniary sanctions of at least 15% of the total turnover in the preceding financial year for infringements of Articles 3 and 5 are mandated. As regards natural persons, maximum administrative pecuniary sanctions of at least EUR 5,000,000 for infringements of Articles 3 and 5 are mandated.

Without prejudice to point (e), the amount of the fine shall not exceed 20% of the annual turnover of the legal person concerned in the preceding financial year. For natural persons, the amount of the fine shall not exceed 20% of the yearly income in the prior calendar year. Where the person has obtained, directly or indirectly, financial benefits from the infringement, the amount of the fine must be at least equal to the benefit obtained. Member States shall ensure that the national regulatory authority may make available to the public the measures or sanctions imposed for infringement of this Regulation, unless such publication would create disproportionate damage to the parties involved.

So, at the level of the European institutions, it is emphasized on the one hand the importance of sanctioning energy market manipulations, but also their gravity, by expressly mentioning high values of fines to be applied, but also taking into account the calculation of the quantities of the fine, based on the total turnover of the previous financial year. From this mention, it appears that the European legislator intended to apply the sanction to a turnover that considers all the activities of an operator, not just the turnover obtained from the licensed capacity in respect of which it exhibited manipulative behavior.

On 11 April 2024, Regulation (EU) No 1106/2024 was adopted, which in Recital (23) provided that “A uniform and more robust framework is needed to prevent market manipulation and other infringements of Regulation (EU) No 1227/2011 in the Member States. In order to ensure the consistent application of administrative fines in all Member States for infringement of Regulation (EU) No 1227/2011, that Regulation should be amended in order to establish a list of administrative fines and other administrative measures that should be available to national regulatory authorities and a list of criteria for determining the level of those administrative fines. In particular, the value of administrative fines that may be applied in a specific case should be able to reach the maximum level provided for in this Regulation. However, this Regulation does not limit the possibility for member states to provide for lower administrative fines on a case-by-case basis. The penalties for infringement of Regulation (EU) No 1227/2011 should be proportionate, effective and dissuasive and reflect the type of infringement, taking into account the ne bis in idem principle. The adoption and publication of administrative fines should respect the fundamental rights set out in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (hereinafter referred to as ‘charter). Administrative fines and other administrative measures are complementary elements of an effective enforcement regime. A harmonized supervision of wholesale energy markets requires a consistent approach among national regulators. To carry out its tasks, it is necessary to make the appropriate resources available to national regulatory authorities”.

The proposals have become official and have been inserted into European Union law, making them directly applicable to the laws of the member states.

It is noted that the text of Article 18 is subtly different, with specific nuances, from the proposal to amend REMIT, but essentially the main aspects remained unchanged:

“(1) Member States shall adopt the rules on penalties to be applied in the event of non-compliance with this Regulation and shall take all necessary measures to ensure their application. The penalties provided for must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive and reflect the nature, duration and seriousness of the infringements, the harm caused to consumers and any benefits derived from insider trading and market manipulation.

Without prejudice to the criminal sanctions and supervisory powers of national regulatory authorities pursuant to Article 13, member states shall, in accordance with national law, confer on national regulatory authorities the power to adopt appropriate administrative fines and other administrative measures in relation to infringements of this Regulation as referred to in Article 13 (1).

(3) Member States shall ensure, in accordance with national law and the principle of ne bis in idem, that national regulatory authorities have the power to impose at least the following administrative fines and other administrative measures in respect of infringements of this Regulation, whereby:

(a) require the cessation of the infringement;

(b) order the recovery of the profits derived from the infringement or losses avoided therein, to the extent that they can be determined;

(c) issue warnings or public announcements;

(d) apply periodic penalty payments;

(e) impose administrative fines.

(4) As regards natural persons, the maximum administrative fines referred to in point (e) of paragraph (3) are as follows:

(a) at least EUR 5,000,000 for infringements of Articles 3 and 5; (…).

Notwithstanding point (e) of paragraph (3), the amount of the administrative fine shall not exceed 20% of the annual income of the natural person concerned in the preceding calendar year. Where the natural person has obtained, directly or indirectly, financial benefits from the infringement, the amount of the administrative fine must be at least equal to the benefit obtained.

(5) As regards legal persons, the maximum administrative fines referred to in point (e) of paragraph (3) are as follows:

(a) at least 15% of the total annual turnover in the preceding financial year for infringements of Articles 3 and 5;

(…)

Notwithstanding point (e) of paragraph (3), the amount of the administrative fine shall not exceed 20% of the annual turnover of the legal person concerned in the preceding business year. In the event that legal person has obtained, directly or indirectly, financial benefits from the infringement, the amount of the administrative fine must be at least equal to the benefit obtained.

(6) Member States shall ensure that the national regulatory authority may make available to the public the measures or sanctions applied for infringement of this Regulation, unless such publication would create disproportionate damage to the parties involved.

(7) Member States shall ensure that, when determining the type and level of administrative fines and other administrative measures, national regulatory authorities take into account all relevant circumstances, including where appropriate:

(a) the gravity and duration of the infringement;

(b) the degree of responsibility of the person responsible for the infringement;

(c) the economic strength of the person responsible for the infringement, as indicated, for example, by the total annual turnover of a legal person or the annual income of a natural person;

(d) the importance of the cumulative profits or losses avoided by the person responsible for the infringement, to the extent that they can be determined;

(e) the extent to which the person responsible for the infringement cooperates with the competent authority, without prejudice to the need to ensure the recovery of profits gained or losses avoided by that person;

(f) infringements previously committed by the person responsible for the infringement;

(g) the measures taken by the person responsible for the infringement to prevent a repetition of the infringement; and

(h) duplication of criminal and administrative proceedings and fines for the same infringement against the person liable for the infringement.”

The European legislator aims to raise awareness about the risks posed by energy market participants who engage in manipulative behavior. By far, the most drastic regulation that has ever existed at the European level is undoubtedly a deterrent to the slightest intention of engaging in such behavior, as the new REMIT heavily sanctions it.

Moreover, at the end of this section, we would like to point out that there are European states that, in response to the high gravity of energy market manipulation, have established a more stringent sanctioning regime, criminalizing the act and imposing sanctions.

Although Regulation (EU) no. 1227/2011 does not expressly recommend the criminalization of acts committed on the energy market specifically as contraventions or offences in the Republic of Moldova (Law no. 249/2022), this type of behavior is criminalized as a crime (

Stati 2023).

We also mention the Regulation of the United Kingd bnom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland of 2015 on the integrity and transparency of the electricity and gas market, which establishes criminal sanctions for offences of using inside information about wholesale energy products (art.3) and offences of market manipulation of wholesale energy products (art. 4) (The Electricity and Gas Market Integrity and Transparency Regulations 2015). Additionally, the Criminal Code of Ukraine, in Article 222-2, criminalizes manipulating the energy market (

Botnarenko and Kryzhna 2023).

At the same time, in Denmark, manipulation of the energy market is severely sanctioned

8 (

Würtz 2023).

At the Council of European Energy Regulation—CEER level

9 a document was identified that emphasizes that following the emergence of REMIT II (a name already established at EU level), it is necessary to align the level of administrative sanctions at the level of European states (

CEER 2014).

However, according to Article 18(1) of REMIT II, Member States shall, by national law, confer on national regulatory authorities the power to impose administrative fines and other appropriate administrative measures about infringements of the Regulation and shall notify the Commission and the Agency in detail of those rules and measures and shall communicate to them without delay any subsequent amendment to those provisions. Paragraph (2) also provides for the situation where the legal system of a Member State does not provide for administrative fines, the Article in question may be applied in its entirety so that the penalty procedure is initiated by the competent authority and imposed by the competent national courts, while ensuring that those remedies are effective and have an equivalent effect to that of the administrative fines imposed by the supervisory authorities. In any case, the penalties imposed must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive, and those Member States shall inform the Commission of the national provisions they adopt under paragraph (1). (2) by 8 May 2026 and shall notify the Commission, without delay, of any subsequent amendment to those provisions.

When attempting to identify the EU Member States that have already implemented the new REMIT II rules, we encountered an apparent lack of concern on their part. The only state that has already adopted implementation of REMIT II rules is Romania. Thus, on 18 December, GEO No. 152 of 2024 on the amendment and completion of certain normative acts was issued (Government of Romania 2024), in which we identify essential amendments to the Energy and Natural Gas Law no. 123/2012 regarding the value of fines.

Thus, in the case of individuals, the violation of the provisions of art. 5 of REMIT is sanctioned with a fine of at least EUR 5,000,000

10 (energy offences), for those provided for in point 42, and in the case of legal entities, with a minimum fine of 15% of the total annual turnover in the financial year preceding the application of the sanction. In both situations, the amount of the fines provided for does not exceed 20% of the annual income in the previous calendar year or of the total yearly turnover in the financial year preceding the application of the sanction. If the person or legal entity has obtained, directly or indirectly, financial benefits as a result of the violation, the amount of the fine must be at least equal to the benefit obtained.

Regarding natural gas offences, for individuals, the legislator has established that the fine is a fixed amount of EUR 5,000,000

11, not identifying any explanation regarding the different legal regime compared to the electricity sector. Moreover, in REMIT II the European legislator did not make any such differentiation. We also note that, although REMIT II does not provide for any minimum of the pecuniary sanctions applied to natural or legal persons who commit the act of market manipulation in one of its forms, but only a minimum of the maximum limits, the Romanian legislator has regulated the latter as the minimum limits of the amounts of fines. Thus, we note that as far as natural persons active in the energy sector are concerned, the minimum of the fine is the minimum of the maximum imposed by REMIT II, and in the case of natural persons in the natural gas sector, the same amount is established, but as a fixed amount. From here, the legitimate question may arise in our opinion, how can the individualization criteria be applied objectively and how can such a high amount of a fine be justified in the situation of a natural person who committed the act without knowledge, who admitted it and who did not produce any effect on the market, in comparison with another person who manipulated the market intentionally? This act had a profound impact. The situation is the same in the case of legal persons, which for committing the act under art. 5 REMIT can be sanctioned with the minimum of the maximum provided for by REMIT II, the Romanian legislator choosing the percentage of 15% as the minimum of the sanction; no provision would allow the regulator to reduce this percentage in the process of individualizing the sanction.

We also note that on the same day as the publication of GEO no. 152/2024 in Romania, ACER published the new version of the Guide, no. 6.1

12. For our analysis, especially from the perspective of implementing the sanctioning regime established in REMIT II, the examples provided by the Guide are relevant precisely so that Member States, even if it is not mandatory, can benefit from an aid in understanding how the regulation is implemented. Thus, the Guide shows that the NRA may impose an administrative measure in accordance with Article 18(3) and the Member State may, in its national law, set a maximum threshold for the administrative fine of at least 1% of the total annual turnover of the legal person in the preceding business year or higher, provided that it does not exceed 20% (e.g., 7%). In this case, the NRA could impose a fine up to the maximum amount provided for under its national threshold (e.g., 7% of its total annual turnover in the preceding business year). In this way, the NRA ensures that the administrative fine does not exceed 20% of the operator’s total yearly turnover in the preceding business year (Point 528, ACER Guide, edition 6.1).

The Guide provides a significant clarification, in the sense that if a natural or legal person commits several acts that may be considered market manipulation, then the maximum ceiling of 20% applies to each violation committed by the market participant separately, as the finding of the existence of several violations may entail the imposition of several distinct fines, each time within the limits provided for in Article 18(4) of REMIT (Judgment of the General Court of 28 April 2010 in case T-446/05).

5. Jurisprudential Insights on the Standard of Proof in REMIT-Related Matters

According to the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), “it is not necessary to provide such evidence for each element of the infringement. It is sufficient that the series of indices invoked by the institution, which are globally appreciated and whose various elements can support each other, meet this requirement”

13.

Moreover, the jurisprudence of the CJEU is constant. From its content, it turns out that the existence of an anti-competitive practice or agreement must be inferred from certain coincidences and indications which, taken as a whole, may constitute, in the absence of another coherent explanation, evidence of infringement of the competition rules (see judgment of the Court of 21 September 2006, Nederlandse Federatieve Vereniging voor de Groothandel op Elektrotechnisch Gebied/Commission, C-105/04 P, Rec., p. I-8725, paragraphs 94 and 135 and the case-law cited)

14.

In another case

15, the European Court has held that “it is sufficient that the series of indices invoked by the Commission, taken as a whole, meets this requirement. Given the notorious nature of the prohibition of anti-competitive agreements, it may not require the Commission to submit elements explicitly attesting contact between the operators concerned. The fragmentary and disparate elements available to the Commission should in any case be able to be supplemented by deductions allowing the relevant circumstances to be reconstituted. Therefore, the existence of an anti-competitive practice or agreement may be inferred from certain coincidences and indications which, taken as a whole, may constitute, in the absence of another coherent explanation, evidence of a breach of competition rules.”

In the national case law of other EU countries, too, it is retained in the same sense. For example, the French Council of State, in its decision of 18 June 2021 (on the 2018 decision of the CRE sanctions committee against Vitol S.A.), it confirmed that the mere probability that a transaction or order would give false or misleading signals to the market is sufficient to qualify a conduct as market manipulation. It is not necessary to demonstrate that such signals were given or that there was an intention to manipulate (Conseil d’État 2021).

On the other hand, regarding the standard of proof, we mention a Decision no. 618/2020 of the Constitutional Court of Romania which, even if it concerns legal rules in criminal matters, we appreciate that it is relevant: “Regarding the analysis of the condition regarding the existence of evidence that a person committed an offence, carried out by the prosecutor, found that it is different from the one made by the court called to decide on the accusation brought against the defendant. To fulfil this condition, it must not be ascertained, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the act exists, constitutes an offence and was committed by the defendant, this being within the competence of the court, according to art. 396 para. (2) of the Criminal Procedure Code” (see, mutatis mutandis, Decision no. 551 of 13 July 2017, published in the Official Gazette of Romania, Part I, no. 977 of 8 December 2017, paragraph 26). The Court found applicable those retained in its case law, in the sense that prosecutors are presumed to carry out their work in good faith so as not to infringe the fundamental rights of persons subject to criminal proceedings.

As regards the concept of reasonable doubt, the Court found that it is also of European jurisprudential origin, the meaning being found, for example, in the judgment of 11 July 2006, pronounced in the Boicenco case against the Republic of Moldova, paragraph 104, according to which the standard of proof “’beyond a reasonable doubt’ allows its deduction from the coexistence of sufficiently well-founded conclusions, clare and concordat or similar and undeniable factual presumptions” (Decision no. 778 of 17 November 2015, published in the Official Gazette of Romania, Part I, no. 111 of 12 February 2016).

Last but not least, we also point to a judgment from national jurisprudence (Bucharest Court of Appeal, Civil Judgment no. 1069/26 May 2022), in which the Court held that “it is highly unlikely that such an understanding could have materialized in written form, since the market manipulation agreement, being illicit, does not take the written form of self-incrimination of the parties of the transaction. It is hard to imagine that economic operators such as those concerned by the investigation would have formulated a market manipulation scheme in writing with the steps to be taken. (…) this is indirect evidence resulting from the applicant’s behavior in the market (…) Therefore, in the light of the standard of proof, the authority (n.ns.) must not provide evidence for each element of the infringement; it is sufficient that the series of indices invoked by the institution, which are globally appreciated and whose various elements can support each other, meet this requirement”.