Abstract

The Marine Pollution Control Act (MPCA) in Taiwan aims to align with international conventions such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC), the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds (FUNDs), and the International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM). However, Taiwan’s particular international status prevents formal participation in these treaties. This study evaluates Taiwan’s legal and institutional frameworks on ship emission control, pollution liability and compensation, and interagency coordination, identifying key gaps compared with global standards. By analyzing Japan’s and South Korea’s best practices in port management, cross-border pollution prevention, and vessel monitoring, this study proposes legal and policy reforms that are tailored to Taiwan. Recommendations include strengthening liability mechanisms, enhancing interagency collaboration, monitoring vessels, and fostering regional cooperation. Our findings suggest that these reforms will improve Taiwan’s marine environmental governance and contribute to regional and global ocean sustainability.

Keywords:

marine environmental governance; marine pollution prevention and control; legal framework for marine protection in Taiwan; international conventions for marine pollution control; marine pollution liability and compensation; marine environmental law and policy reforms; transboundary marine pollution governance 1. Introduction

1.1. The Global Challenge of Marine Pollution

Marine pollution has emerged as one of the most critical global environmental crises, posing severe and multifaceted threats to marine ecosystems, fisheries resources, and the socioeconomic sustainability of coastal communities (Huang 2017). According to United Nations reports, more than eight million metric tons of plastic and other anthropogenic waste is discharged into the oceans annually, substantially degrading marine biodiversity, disrupting trophic structures, and compromising the integrity of marine habitats (Wei and Hsu 2002). Beyond plastic waste, other major pollutants, including oil spills, hazardous substances, and untreated industrial effluents, continue to cause irreversible ecological harm to marine and coastal environments. Notably, catastrophic incidents such as the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill exemplify the long-term environmental, economic, and legal ramifications of petroleum-based marine pollution (Zhu et al. 2022).

In response to the transboundary and complex nature of marine pollution, the global community has developed a comprehensive legal and cooperative framework. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, serves as the foundational legal instrument for the protection of the marine environment. It delineates the jurisdictional rights and obligations of states within territorial waters, exclusive economic zones (EEZs), and the high seas (Nordquist and Nandan 2011). Complementing UNCLOS, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (IMO 1978), administered by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), establishes binding technical standards to minimize pollution from maritime shipping activities, thereby forming a cornerstone of global maritime environmental governance (IMO 1992).

1.2. Taiwan’s Geographical Position and Marine Pollution Risks

Taiwan is an island located in East Asia, surrounded by ocean, with over 1500 km of coastline. Its economy relies heavily on the ocean for international shipping, fisheries, tourism, and energy development (Chiu 2003). However, this geographic condition also exposes Taiwan to significant risks of marine pollution (Shih 2020). Situated along major international shipping routes in East Asia, Taiwan experiences dense maritime traffic, including container ships and oil tankers, which increases the risk of vessel-sourced pollution (Wong 2017).

Although nearshore fisheries and aquaculture provide economic benefits, mismanagement may lead to the discharge of waste and chemicals into the marine environment, posing threats to ecological systems (Walther et al. 2021). Land-based pollution is another major concern, including urban sewage, industrial effluents, and agricultural runoff. These pollutants are carried by rivers into the sea, exacerbating coastal ecological degradation (Chen 2003; Tseng and Ng 2021).

According to a 2020 report by the Ocean Affairs Council of Taiwan, many coastal areas exhibit excessive levels of heavy metals and nutrients in the seawater, indicating the seriousness of the problem of pollution (Ocean Affairs Council 2020).

1.3. The Influence of International Marine Conventions on Taiwan

Within the framework of global ocean governance, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) serve as the primary legal bases for states to address marine pollution (Huang 2017). However, due to Taiwan’s particular international status, it is not a formal signatory to these conventions (Ocean Affairs Council 2023a), which poses challenges in international cooperation and the management of transboundary pollution events (Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2020).

Nevertheless, Taiwan has actively pursued a voluntary alignment approach by referencing the core principles of UNCLOS and MARPOL to revise its environmental legislation and implement proactive measures (Ocean Affairs Council 2020). Key efforts are described below.

- Regulatory alignment: Taiwan has established pollutant discharge standards in accordance with MARPOL provisions (IMO 1992).

- Regional cooperation: Taiwan has sought to participate in the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP) and other informal regional cooperation initiatives to collaborate with neighboring locations such as Japan and South Korea on marine pollution monitoring (Ocean Affairs Council 2023b).

- Strengthening jurisdictional enforcement: Taiwan has improved its environmental regulatory mechanisms to meet international environmental protection standards (Tseng and Ng 2021).

These efforts enhance Taiwan’s marine governance capacity and foster stronger regional and global environmental cooperation (Shih 2020).

1.4. Background and Challenges to Taiwan’s Marine Pollution Control Act

Taiwan enacted the Marine Pollution Control Act (MPCA) in 2000 as its primary legal basis for marine pollution governance. The Act outlines key provisions regarding marine waste discharge management, pollution liability mechanisms, and administrative penalties for violations (Ocean Affairs Council n.d.). Taiwan significantly revised its Marine Pollution Control Act and related regulations on 31 May 2023. Key revisions are as follows:

- 1.

- Reducing Land-based Marine Pollution:

In alignment with the spirit of the United Nations Global Program of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities (GPA), new provisions were added to reduce marine pollution from land-based waste, aiming to achieve marine waste reduction targets.

- 2.

- Prohibiting Incineration at Sea:

Referring to Article 5 of the 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, 1972 (London Protocol), the provisions allowing for “incineration at sea of wastes or other matter” have been deleted, thereby prohibiting such practices.

- 3.

- Regulating Artificial Islands, Installations, and Structures in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ):

Referencing Article 60 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) concerning artificial islands, installations, and structures within the EEZ, and to strengthen sea area management, new rules stipulate that competent authorities, when permitting the deployment, laying, or placement of various marine installations, fishing facilities, and other artificial structures, must conduct verification checks. These facilities and structures must now have a decommissioning plan, which must be executed according to regulations upon the expiration of their permitted term.

- 4.

- Exceptions for Incineration at Sea (Strictly Defined):

Referring to Articles 5 and 8 of the 1996 London Protocol, incineration at sea of wastes or other matter is prohibited, except under the following strict conditions:

- (1)

- Force majeure caused by stress of weather, endangering human lives or the safety of vessels, aircraft, marine installations, or other artificial structures.

- (2)

- Any situation endangering human lives or posing a threat to vessels, aircraft, marine installations, or other artificial structures.

- (3)

- Incineration at sea is the sole method to avoid the threats mentioned in the preceding two points.

- (4)

- The damage caused by incineration at sea is less than that from other disposal methods.

Furthermore, the competent authority may approve incineration at sea in emergency situations where there is an unacceptable threat to human health, personal safety, or the marine environment, and no other feasible alternatives exist.

- 5.

- Clarifying Ship Inspection Procedures:

To clearly define the content of ship inspections, and referencing MARPOL and its amendments, it is now explicitly stated that inspection items for International Sewage Pollution Prevention Certificates and International Oil Pollution Prevention Certificates include documents such as the “Shipboard Oil Pollution Emergency Plan” and the “Garbage Record Book.” Provisions have also been added to impose an obligation on the inspected party to cooperate.

- 6.

- Strengthening Restrictions on Vessel Departure for Violations:

Referring to the spirit of the MARPOL Convention and Article 59 of the Shipping Business Act, to actively prevent marine pollution from vessels and strengthen control over restricting relevant vessels from departing, new provisions stipulate that vessels found in violation of this Act and subject to fines may be prohibited from sailing, departing, or required to move their position until the fine is paid or adequate security is provided.

- 7.

- Increasing Penalties for Significant Marine Pollution Violations:

Referencing MARPOL Annex I and considering the actual size of vessels entering and exiting ports under Taiwan’s jurisdiction, general vessels with a gross tonnage of 400 or more and oil tankers or chemical tankers with a gross tonnage of 150 or more pose a higher risk of marine pollution if they do not adopt appropriate pollution prevention measures (such as preventing discharges). In practical cases, indiscriminate dumping of wastewater or oil into the ocean by vessels often causes severe ecological pollution and damage, requiring significant human and material resources from relevant agencies and businesses for cleanup and treatment. This cost far exceeds the originally stipulated fine amounts. To severely punish such major violations, the fine amounts have been increased and are now categorized into two tiers based on vessel size.

However, as international environmental standards have become more rigorous, the legal framework applicable in Taiwan continues to fall short of full alignment with global norms (Wei and Hsu 2002).

The major challenges are described below:

- Insufficient flag state responsibility: Under UNCLOS, flag states are obliged to ensure that vessels under their registry comply with relevant environmental laws. Taiwan’s regulatory mechanisms lack the robustness to monitor and enforce compliance among foreign-flagged vessels effectively (Wei and Hsu 2002; Doud 1972).

- Pollution by foreign warships: the current legal statutes do not adequately address incidents caused by foreign military vessels, posing serious enforcement challenges in transboundary pollution cases (Chiang 2018; United Nations 2015).

- Lack of interagency coordination: fragmented responsibilities among the Ocean Affairs Council, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Transportation, and local authorities have impeded the implementation and coordination of marine environmental policies (Shih 2020).

To address these challenges, Taiwan must update its legislative instruments to reinforce liability systems and enhance its enforcement capacity (Wei and Hsu 2002; Tseng and Ng 2021).

1.5. Research Objectives and Significance

Given the global trend toward integrated ocean governance1, Taiwan urgently needs to reassess its marine pollution control policies, identify gaps in compliance with international standards, and propose concrete legislative and policy reforms (Wei and Hsu 2002).

The main objectives of this study are as follows:

- To systematically evaluate the consistency between the Marine Pollution Control Act in Taiwan and key international conventions, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), and the Civil Liability Convention (CLC) and International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds (FUNDs) (United Nations 1982; IMO 1978).

- To examine critical gaps in Taiwan’s legislation, such as weaknesses in flag state responsibility and pollution compensation mechanisms (Doud 1972).

- To explore how regional cooperation frameworks, such as the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP), can be leveraged to enhance Taiwan’s international environmental influence (Walther et al. 2021).

Through comparative legal analysis and policy evaluation, this research aims to provide actionable recommendations for legal and policy reforms, supporting the enhancement of Taiwan’s marine environmental governance capacity (Chen 2003; Chiang 2018).

2. Regulatory Advances and Challenges in Marine Environmental Protection

This section explores the development of international marine conventions and their pivotal role in global ocean governance. It also analyzes the evolution of and challenges for the Marine Pollution Control Act in Taiwan since its enactment in 2000. A systematic comparison between Taiwan’s regulatory framework and international standards is conducted to establish the theoretical foundation for the subsequent policy analysis and recommendations (Shih 2020; Chen 2003).

2.1. Overview of International Marine Conventions

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), signed in 1982 and enforced in 1994, is widely regarded as the constitution of the ocean, offering a comprehensive legal foundation for global marine governance (United Nations 1982). UNCLOS defines rights and responsibilities in territorial seas, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones (EEZs), continental shelves, and the high seas (Nordquist and Nandan 2011). It also outlines key obligations for coastal jurisdictions concerning marine environmental protection and pollution control (IMO 1978).

Part XII of the UNCLOS specifically focuses on the protection and preservation of the marine environment, mandating contracting states to take all necessary measures to prevent, reduce, and control pollution. Key aspects include the following:

- Flag state responsibility: flag states must ensure that ships under their registry comply with environmental regulations (IMO 1992).

- Transboundary cooperation: states are encouraged to jointly develop policies and share information and technologies to prevent marine pollution (Stokke and Thommessen 2013).

- Coastal state jurisdiction: coastal jurisdictions have the right to enforce environmental standards in their EEZs while respecting the navigational freedoms of other nations (United Nations 1982).

UNCLOS emphasizes international cooperation, requiring states to transcend national borders to address marine pollution challenges (United Nations 2015).

2.2. International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL)

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78), governed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), is the principal international framework for regulating ship-based marine pollution. It covers various pollution sources, including oil, noxious liquid substances, harmful substances in packaged form, sewage, garbage, and air emissions (IMO 1978). MARPOL obliges contracting parties to carry out the following actions:

- Ensure that vessels comply with discharge standards and undergo regular environmental inspections (IMO 1978).

- Mandate liability insurance for shipowners to guarantee compensation in the event of pollution incidents (IMO 1992).

- Establish port reception facilities for waste management to prevent marine dumping (Doud 1972).

Through these provisions, MARPOL has established international benchmarks for environmental protection in the shipping industry and clarified participating parties’ responsibilities for monitoring compliance (United Nations 2015).

2.3. Civil Liability Convention (CLC) and International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund (FUND)

Together, the Civil Liability Convention (Bergesen et al. 2018) and the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund create a comprehensive liability and compensation regime for oil pollution damage. These conventions are designed to ensure that victims receive fair and timely compensation, and that environmental accountability is upheld (IMO 1992), as described below.

- The CLC imposes strict liability on shipowners for oil pollution, making them responsible even in the absence of proven fault (Doud 1972).

- The FUND provides a supplementary international compensation mechanism to cover damages exceeding shipowner liability, particularly for major oil spill events (Stokke and Thommessen 2013).

These instruments serve to uphold the polluter-pays principle and ensure financial security for coastal jurisdictions that are affected by marine pollution (Wang 2011).

2.4. International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM)

The BWM is an international convention adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 2004 and officially entered into force on 8 September 2017. Its primary objective is to prevent, minimize, and ultimately eliminate the transfer of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens through ships’ ballast water and sediments.

Ships take on ballast water when unladen or partially loaded to maintain stability and balance during voyages. When a ship reaches its destination port or area, this ballast water is discharged, potentially carrying various microscopic organisms, microorganisms, viruses, or pathogens from the original waters. Once these foreign species enter a new ecosystem, they can become invasive species, causing devastating impacts on local marine ecosystems, destroying biodiversity, and even affecting human health and fisheries resources. The BWM convention was specifically developed to address this global environmental issue.

2.5. Implications of International Conventions for Taiwan

Although Taiwan is not a formal signatory to UNCLOS or MARPOL due to its unique political and diplomatic circumstances, these international conventions continue to exert significant influence over its environmental law and marine policy (Ocean Affairs Council 2020). Through a strategy of voluntary alignment, the authorities have progressively harmonized legislation within the jurisdiction with global norms. This alignment not only enhances its credibility in global marine governance but also facilitates informal multilateral collaboration with regional actors such as Japan and South Korea (Walther et al. 2021).

2.6. Evolution of the Marine Pollution Control Act in Taiwan

Enacted in 2000, the Marine Pollution Control Act (MPCA) established the legislative framework for regulating ocean-based and land-based pollution sources within the jurisdiction (Chiang 2018). The MPCA covers the following:

- Pollution from ships: vessels are prohibited from discharging hazardous substances into marine waters.

- Land-based pollution: untreated discharges from municipal and industrial sources are banned.

- Waste disposal: marine litter and toxic materials are restricted from entering coastal zones (Wei and Hsu 2002; Walther et al. 2021).

Revisions in 2014 and 2023 introduced stricter administrative penalties and strengthened the mechanisms for inter-ministerial coordination. However, enforcement challenges and structural gaps persist.

2.7. Deficiencies in Taiwan’s Legal Framework

Taiwan’s Marine Pollution Control Act is a crucial piece of legislation enacted to prevent and control marine pollution, maintain the marine ecological environment, safeguard public health, and ensure the sustainable use of marine resources. Its main chapters and core content are as follows:

Chapter 1, “General Provisions”, establishes the purpose, objectives, competent authorities, and fundamental principles of the entire Act. Chapter 2, “Marine Environment Management”, focuses on preventive measures and planning, aiming to reduce the likelihood of pollution occurring at its source.

Chapter 3, “Management of Polluting Activities”, is one of the core chapters, detailing the control measures for various sources of pollution. Vessel pollution control includes standards and controls for the discharge of oil, hazardous substances, sewage, and garbage from vessels. It also covers requirements for vessel pollution prevention equipment and certificates (such as the International Oil Pollution Prevention Certificate and the International Sewage Pollution Prevention Certificate), regulations for the establishment and use of port reception facilities, and obligations for vessel accident reporting and response. Marine installation pollution control covers pollution prevention requirements for marine installations (such as oil drilling platforms, offshore wind power facilities, and aquaculture farms) during their construction, operation, and decommissioning processes. This includes waste disposal, discharge water quality standards, and pollution response plans. The 2023 amendment, in particular, added requirements for decommissioning plans for artificial structures. Land-based pollution control regulates the discharge of pollutants from land (such as industrial wastewater, municipal sewage, agricultural runoff, and waste) into the ocean. It emphasizes the coordination with land-based regulations like the Water Pollution Control Act and the Waste Disposal Act. The 2023 amendment, referencing the spirit of the GPA (Global Program of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities), strengthened the reduction and prevention of land-based waste. Control of ocean dumping and incineration regulates the permitting system and strict restrictions for the dumping of waste into the ocean. The 2023 amendment, referencing the London Protocol, explicitly prohibits incineration at sea of wastes or other matter and outlines strict exceptional circumstances. Control of other potentially polluting activities includes regulations for special substances and experimental discharges.

Chapter 4, “Response to Pollution Incidents”, specifies response, cleanup, and liability assignment when marine pollution incidents occur. Vessels, marine installations, or any party causing marine pollution must immediately report to the competent authority. It requires vessels, marine installations, and relevant business entities to have pollution response plans and conduct regular drills. The polluter is responsible for cleaning up the pollution; if they fail to do so or do not act promptly, the competent authority may undertake the cleanup and seek reimbursement from the polluter. The competent authority must establish an emergency response mechanism to coordinate relevant units for pollution cleanup. It also stipulates that polluters are liable for compensation for damages to marine ecosystems and fishery resources. Chapter 5, “Penalties”, clearly defines the legal liabilities for violating various provisions of the Act, including administrative fines, criminal penalties, and forfeiture. It also includes provisions for prohibiting sailing, departure, or requiring relocation: for violating vessels, the competent authority has the right to restrict their navigation until the fine is paid or adequate security is provided. Those causing severe marine pollution or committing grave offenses may face imprisonment or a concurrent fine. Joint liability may include legal entities, responsible persons, captains, and direct perpetrators. Chapter 6, “Supplementary Provisions”, contains supplementary regulations, such as the enforcement rules and the formulation of related measures.

As mentioned above, some deficiencies in Taiwan’s legal framework are as follows:

- Lack of Flag State ResponsibilityDespite UNCLOS provisions that obligate flag states to monitor and enforce pollution controls on vessels under their registry, Taiwan’s legal system lacks a robust enforcement framework for both local and foreign-flagged vessels entering its ports (Walther et al. 2021).

- Inadequate Mandatory Insurance MechanismsTaiwan’s legal framework has yet to implement the liability caps and mandatory insurance provisions that are outlined in the CLC and FUND. As a result, shipowners face unlimited strict liability without a structured compensation mechanism, which could hinder fair and timely reimbursement in the event of oil pollution incidents (Wang 2011).

- Limited International CooperationDue to its political isolation, Taiwan’s exclusion from major international marine regulatory bodies weakens its capacity to manage transboundary marine pollution. This limitation restricts access to vital data sharing and joint response protocols, which are required for effective regional environmental governance (Haward and Jackson 2023).

2.8. Gaps Between Taiwan’s Laws and International Conventions

Although Taiwan has established a legal foundation for addressing marine pollution, discrepancies remain between its jurisdictional laws and major international conventions such as the UNCLOS, MARPOL, Civil Liability Convention (CLC), International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund (FUND) (United Nations 1982; IMO 1978; Doud 1972), and International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM).

Notable legal and institutional gaps include the following:

- Insufficient oversight of foreign ships: a weak enforcement capacity limits Taiwan’s ability to regulate foreign vessels entering its waters (Nordquist and Nandan 2011).

- Immunity of military vessels: Taiwan lacks provisions to effectively manage pollution incidents caused by foreign military ships, which are typically exempt from applicable jurisdiction (Huang 2017).

To close these gaps, this study proposes the following:

- Adopting a strict liability regime: Taiwan should incorporate a no-fault liability system to ensure that shipowners are held accountable regardless of negligence (Wang 2011).

- Establishing a jurisdiction-wide compensation fund: a dedicated fund is essential to guarantee financial support in the event of large-scale marine pollution incidents (Stokke and Thommessen 2013).

- Enhancing regional cooperation: Taiwan must proactively participate in regional environmental programs and informal international partnerships (Walther et al. 2021).

2.9. Conclusions

This section examined the core principles of international marine environmental conventions and analyzed their applicability to Taiwan. Despite Taiwan’s effort to reform its Marine Pollution Control Act, major challenges persist, particularly in relation to flag state enforcement, insurance obligations, and multilateral environmental cooperation mechanisms (Walther et al. 2021; Wang 2011). Bridging these regulatory gaps will be essential for aligning Taiwan’s marine governance with global environmental standards and enhancing its presence in regional governance frameworks.

3. Research Methodology

This study adopts a comprehensive research methodology that integrates qualitative analysis, comparative legal analysis, and case study methods. The primary objective is to systematically examine the consistency between the Marine Pollution Control Act enforced by the authorities in Taiwan and major international conventions, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC), the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds (FUNDs) (Chiang 2018; Wei and Hsu 2002), and the International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM).

The comparative legal approach facilitates the identification of legislative gaps and institutional deficiencies in the current marine environmental governance framework in Taiwan. Simultaneously, international case studies, particularly those from Japan and South Korea, are analyzed to extract effective policy practices that can be adapted to the context of Taiwan (Shih 2020; Walther et al. 2021). The methodological framework enables the formulation of context-specific and legally sound recommendations aimed at strengthening regulatory alignment with global marine environmental standards and enhancing its regulatory capacity.

3.1. Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis is a widely adopted approach in both social science and legal research and is particularly suited for interpreting regulatory texts, policy frameworks, and treaty obligations. This study applies qualitative analysis to examine the Marine Pollution Control Act as implemented by the authorities in Taiwan (MPCA) on an article-by-article basis, identifying the structural design and implementation practices. The MPCA is then compared with corresponding provisions in international legal instruments, including the UNCLOS, MARPOL, CLC, and FUND (Chiang 2018; Huang 2017).

This method facilitates the identification of legal strengths and weaknesses, revealing latent policy gaps and inconsistencies with international obligations. Primary sources include the original MPCA, subsequent amendments, as well as key treaties and protocols. Supplementary materials include policy white papers, inter-ministerial guidelines, and civil society reports (Ocean Affairs Council 2020).

The methodological process is structured into two stages:

- Data categorization and thematic coding: legal provisions were systematically categorized under themes such as flag state responsibility, insurance and compensation mechanisms, and transnational cooperation (Wei 2002).

- Interpretative analysis: through iterative reading and contextual interpretation, this study highlights divergences between local regulations and international standards, offering insights into the legislative rationale of the governing authorities in Taiwan and institutional capacity constraints (Wei 2002).

3.2. Comparative Legal Analysis

Comparative legal analysis serves as the second key methodological tool, enabling the evaluation of the MPCA as implemented by the authorities in Taiwan considering the normative contents of the UNCLOS, MARPOL, CLC, and FUND (Huang 2017). This cross-jurisdictional comparison identifies both structural convergence and legal lacunae between the regulatory framework applicable in Taiwan and the global regulatory community.

The comparative analyses focus on three principal areas:

- Flag state responsibility: UNCLOS Article 94 requires flag states to ensure that vessels that are flying their flag conform to international pollution standards. This study assesses the extent to which Taiwan’s regulatory system imposes and enforces such obligations (Wei and Hsu 2002).

- Insurance and compensation mechanisms: The CLC and FUND frameworks impose strict liability and require shipowners to maintain financial security. Taiwan, however, lacks a mandatory insurance regime, leaving potential victims vulnerable to inadequate compensation. Legislative reform proposals are presented to close this gap.

- Sovereign immunity of warships: Although the UNCLOS recognizes the immunity of state-owned warships, it also encourages environmental compliance. Taiwan’s regulatory ambiguity in addressing pollution from foreign naval vessels is critically evaluated within this international legal context (Chiang 2018).

3.3. Case Study Method

To identify exemplary international practices in marine pollution control, this study adopts a comparative case study method, selecting Japan and South Korea as reference countries (Ocean Affairs Council 2023b). These two East Asian nations exhibit geographic, economic, and environmental similarities with the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) and have accumulated considerable experience in oil spill prevention, port governance, and transboundary cooperation (Wei and Hsu 2002; Chiang 2018).

3.3.1. Data Collection and Analysis

This stage involved collecting and analyzing legislative frameworks, official policy documents, and environmental reports from Japan and South Korea. Particular attention was given to their institutional designs regarding liability insurance schemes, cross-ministerial coordination, and regional collaboration mechanisms (Chiang 2018).

3.3.2. Policy Effectiveness Evaluation

By analyzing the practical experiences of selected countries, this study evaluates the effectiveness of their policies in reducing marine pollution and enhancing international cooperation (Chen 2003). Based on the findings from the case studies, this research formulates policy recommendations that are tailored to the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s legal and institutional context, thereby facilitating progress in regulatory reform and global environmental engagement. The rationale for the selection of case countries is as follows:

- Geographic and Economic SimilarityJapan, South Korea, and the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) are all located in the East Asian region and possess extensive coastlines. These jurisdictions rely heavily on ocean-based economic activities, such as fisheries, maritime transportation, and coastal tourism, as pillars of their respective economies. Consequently, they share common challenges in marine environmental protection. A summary of these shared challenges is presented below:

- A high vessel density increases the probability of maritime pollution (Zhu et al. 2022).

- Intensive coastal fisheries require effective regulatory balancing between exploitation and conservation (Ma 2007).

- Rapid urban–industrial development has led to land-based pollution and marine debris challenges (Ocean Affairs Council 2023a).

Given these shared geographical and economic characteristics, the marine policy frameworks of Japan and South Korea offer particularly valuable references for the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s policy development and legal reform.

- 2.

- Advanced Port Management and Marine Pollution ControlBoth countries have implemented the following measures:

- Mandatory insurance and compensation systems under the CLC and FUND (IMO 1992).

- Port State Control (PSC) inspections of foreign vessels for compliance with the MARPOL and national regulations (IMO 1978).

- 3.

- Proven Regional Cooperation Models

- Japan and Korea actively participate in the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP), promoting shared databases, joint emergency drills, and transboundary pollution tracking (Haward and Jackson 2023).

- They also engage in bilateral and multilateral environmental agreements across the region (Ocean Affairs Council 2020).

- 4.

- Alignment with the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s Regulatory Reform NeedsJapan and South Korea emphasize regulatory flexibility and pragmatic policy implementation in their marine environmental governance strategies. These approaches offer critical relevance for Taiwan’s ongoing efforts to modernize its legislative and institutional frameworks. The key insights can be summarized as follows:

- Establishment of Cross-Sectoral Coordination Platforms:Both countries have developed interagency coordination mechanisms that facilitate rapid governmental responses to marine pollution events (Walther et al. 2021). This provides valuable lessons for the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan), where fragmented responsibilities among the Ocean Affairs Council, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Transportation, Taiwan International Ports Corporation, and local governments hinder timely and unified action.

- Public Participation and Environmental Education:Japan and South Korea have achieved notable progress in advancing environmental education and citizen science initiatives (Walther et al. 2021). The jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) can draw upon these experiences to promote public awareness, foster civic engagement, and build a participatory culture in marine pollution monitoring and environmental governance.

- 5.

- Tangible Policy OutcomesJapan and South Korea have achieved notable success in the implementation of marine pollution prevention policies, achieving tangible reductions in oil spill incidents and marine debris. Japan has established a sophisticated coastal monitoring system that is capable of real-time detection and rapid response to pollution events (Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan 2024). In contrast, South Korea has effectively curbed port pollution through stringent enforcement measures and substantial penalties for violations (MLIT Japan 2022).

3.4. Conclusion: Justification for Comparative Jurisdiction Selection

As established in the preceding sections, Japan and South Korea have demonstrated substantial success in marine pollution prevention, port environmental regulation, and regional environmental cooperation. Given their geographic proximity, shared maritime pressures, and similar economic dependencies to those of the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan), they represent highly suitable benchmarks for a comparative analysis (Chiang 2018; Chen 2003; Walther et al. 2021). This study evaluates the core legislative and institutional frameworks of both countries and extracts relevant policy recommendations that are aligned with the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s legal reform priorities and its aspirations to harmonize with international standards.

While future research may incorporate broader comparisons with countries such as EU member states or the United States to increase the diversity, Japan and South Korea currently offer the most contextually relevant and actionable insights for the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s near-term governance challenges.

3.5. Scope and Limitations of Case Selection

This research confines its case study scope to Japan and South Korea, both of which exhibit strong similarities with the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) in terms of maritime geography, environmental governance, and regulatory structure. Although this narrowed scope limits the generalizability of the findings, it enhances the analytical rigor and depth of the policy evaluation.

- 1.

- Limitations of Time and ResourcesAcademic research inevitably faces constraints on time, human resources, and access to primary data. This study prioritizes (Walther et al. 2021) actionable outcomes over broad coverage, aiming to generate feasible and high-impact recommendations within realistic research capacities.

- 2.

- High Relevance and Similarity to TaiwanJapan and South Korea exhibit significant geographical, economic, and environmental similarities with Taiwan, rendering their marine governance experiences particularly relevant for and transferable to the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s legal and policy reform process (Walther et al. 2021). Key commonalities include the following:

- Geographical position: all three jurisdictions are situated in East Asia and located along major international maritime routes, facing elevated risks of vessel-sourced pollution due to significant shipping traffic (Wei and Hsu 2002).

- Economic dependence on marine resources: Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan all rely heavily on the ocean for trade, fisheries, and tourism, necessitating a balance between economic development and environmental sustainability (Ocean Affairs Council 2020).

- Land-based pollution and marine debris: due to dense coastal populations and industrial development, these jurisdictions face substantial challenges in relation to wastewater discharge and marine litter, which require robust regulatory control (Walther et al. 2021).

- Given these structural parallels, the policy successes of Japan and South Korea offer particularly valuable insights that can inform the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s own legislative modernization efforts.

- 3.

- Active Engagement in International CooperationBoth countries are key participants in regional and global frameworks such as the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO), offering valuable insights for the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan), which faces diplomatic constraints (MERRAC/NOWPAP Korea Report 2021).

- 4.

- Need for In-Depth Policy AnalysisInstead of undertaking a shallow comparative review of several countries, this research adopts an in-depth, focused approach. By concentrating on two highly relevant jurisdictions, the study provides a more comprehensive understanding of policy design and implementation.

- 5.

- Constraints Related to the International Status of the Jurisdiction under Study (Taiwan)The jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s exclusion from most formal global environmental agreements necessitates a strategy of emulation and regional alignment. Japan and Korea, which operate within both formal and informal cooperation channels, serve as viable models (Ocean Affairs Council 2023b).

- 6.

- Methodological SoundnessIn comparative legal research, relevance and contextual fit should be prioritized over sheer scope. An overextension of the sample may dilute the clarity of findings. This study adheres to a rigorous and focused comparative design that enhances its policy relevance and analytical robustness.

3.6. Research Limitations

Taiwan’s exclusion from international organizations presents significant challenges in accessing firsthand information relating to global environmental cooperation (United Nations 1982). Furthermore, variations in the jurisdictional implementation of international conventions across jurisdictions may affect the legal comparability of outcomes. Legal traditions and administrative structures differ across countries, often reflecting unique sociopolitical contexts. As such, purely textual comparisons may not capture the underlying legislative rationale. To address this limitation, this study employs a case-based interpretive approach that complements doctrinal legal analysis, thereby improving the contextual sensitivity and analytical robustness of the findings.

3.7. Conclusions

This study employs an integrated research framework combining qualitative analysis, a comparative legal methodology, and case study analysis to examine the Marine Pollution Control Act of the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) in relation to key international conventions, including the UNCLOS, MARPOL, CLC, and FUND. Through this interdisciplinary approach, the study identifies in the legal framework of the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) and offers targeted recommendations based on global best practices. These methods provide a solid empirical and theoretical foundation for policy reform proposals aimed at enhancing the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s alignment with international marine environmental governance standards. Moving forward, the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s proactive engagement in regional partnerships and continued legal modernization will be essential in advancing its environmental diplomacy and strengthening its role in global marine protection (Walther et al. 2021; Ocean Affairs Council 2023b).

4. Research Findings and Discussion

This section provides an in-depth examination of the legal deficiencies and challenges that are embedded in the Marine Pollution Control Act of the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan). It also incorporates comparative insights from international case studies, particularly focusing on Japan and South Korea’s experiences in marine pollution prevention and control. The discussion addresses the regulatory shortcomings of the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) in areas such as liability and compensation mechanisms, ship and port management, and interagency coordination in pollution responses. Drawing on international best practices, this chapter proposes evidence-based policy recommendations to inform and guide future legislative and institutional reforms.

4.1. Legal Deficiencies and Challenges in the Jurisdiction Under Study (Taiwan)

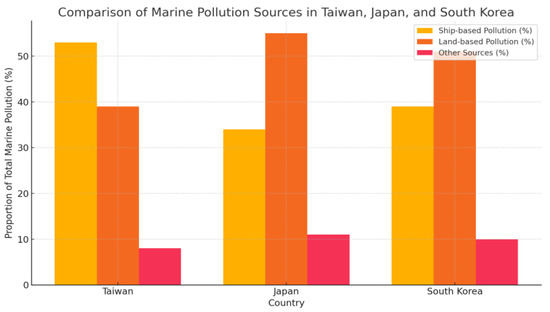

The data presented in Figure 1 demonstrate that ship-based pollution makes up 53% of the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan)’s total marine pollution sources, which exceeds the percentages found in Japan (34%) and South Korea (39%). These two countries have established better regulatory systems for urban discharges and industrial effluents, because land-based pollution makes up 55% and 51% of their total marine pollution. Figure 1 demonstrates through a cross-jurisdictional comparison that the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) needs to strengthen its port management and ship pollution control regulations. This research indicates that the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) must enhance its vessel emission control systems and environmental monitoring infrastructure (Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan 2024; Ocean Affairs Council 2023b).

Figure 1.

Comparison of marine pollution sources in Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea.

Strict liability and compulsory insurance are foundational components of global marine pollution governance, ensuring that victims receive prompt and adequate compensation. International frameworks such as the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC) and the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds (FUNDs) assign strict liability to shipowners, holding them financially responsible for oil pollution damage, regardless of fault (IMO 1992; Stokke and Thommessen 2013).

The current legal regime of the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) lacks equivalent provisions, particularly with respect to mandatory liability insurance. While the Marine Pollution Control Act imposes liability on polluters, it does not require all vessels to carry insurance coverage. Consequently, if a shipowner is unable to pay compensation following a pollution incident, victims may remain uncompensated (IMO 1992). Furthermore, the absence of a centralized compensation fund limits fiscal resilience in Taiwan in addressing large-scale marine pollution emergencies (Stokke and Thommessen 2013).

Port State Control (PSC) is another area in which the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) falls short. According to the MARPOL, contracting states are obligated to implement PSC mechanisms to inspect foreign vessels entering their ports and ensure compliance with environmental regulations (IMO 1978). The PSC regime in the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) remains incomplete, and its enforcement capabilities are limited. Its current port surveillance and discharge control measures are insufficient to prevent pollution from foreign ships (Walther et al. 2021).

Another complex legal issue involves the sovereign immunity of foreign naval vessels. Under Article 32 of the UNCLOS, warships and government vessels enjoy immunity in foreign territorial seas, precluding legal jurisdiction by the host state (United Nations 1982). As a result, the jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) cannot directly sanction or inspect foreign military vessels that are involved in pollution incidents, which necessitates diplomatic resolution (Nordquist and Nandan 2011).

Additionally, the fragmented governance of marine and land-based pollution sources impedes effective policy implementation. The jurisdiction under study (Taiwan) lacks horizontal integration among key legal instruments such as the Marine Pollution Control Act, Waste Disposal Act, and Water Pollution Control Act. This regulatory fragmentation permits unchecked pollution from municipal sewage, industrial discharge, and agricultural runoff to enter marine environments (Wong 2017). Coordination between relevant agencies, including the Ocean Affairs Council, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Transportation, Taiwan International Ports Corporation, and local governments, remains weak. The absence of a unified, cross-sectoral platform slows emergency responses and hinders systemic policy execution (Ocean Affairs Council 2023b).

4.2. Lessons from International Case Studies

Japan offers a comprehensive model for port governance and oil spill compensation. Its implementation of Port State Control (PSC) ensures that foreign vessels entering Japanese ports undergo strict environmental inspections. Non-compliant ships face substantial fines or denial of port entry (Walther et al. 2021). Furthermore, Japan mandates environmental liability insurance and has established compensation funds in alignment with the CLC and FUND frameworks, enabling rapid and coordinated disbursement of reparations between insurers and public agencies (Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan 2024).

South Korea distinguishes itself through regional collaboration and technological integration. The country is a proactive member of the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP), promoting transnational data sharing and cooperative emergency responses (MERRAC/NOWPAP Korea Report 2021). Moreover, South Korea utilizes Internet of Things (IoT)- and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enabled monitoring systems across ports and marine zones to track vessel emissions and detect real-time changes in environmental conditions (Walther et al. 2020).

4.3. Policy Recommendations for Taiwan

Based on the comparative analysis, structural reforms are needed in Taiwan’s marine governance framework in its marine environmental governance. The following policy recommendations are made:

- Adopt strict liability and mandatory insurance: All vessels should be required to obtain sufficient environmental liability insurance. Additionally, a competent authority should establish a jurisdiction-wide compensation fund to guarantee financial capacity for prompt compensation and restoration following oil pollution events (IMO 1992; Stokke and Thommessen 2013).

- Strengthen port regulation and foreign vessel oversight: it is recommended to introduce a comprehensive PSC regime and develop bi- or multilateral mechanisms with neighboring jurisdictions to manage pollution caused by foreign naval vessels (IMO 1978).

- Integrate pollution control systems: Taiwan should establish a centralized coordination platform that unifies marine and land-based pollution management across the Ocean Affairs Council, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Transportation, and other relevant entities to enhance policy coherence and rapid response capabilities (Ocean Affairs Council 2023b).

- Promote regional cooperation and digital technologies: participation in regional frameworks such as NOWPAP should be pursued and deploy advanced monitoring technologies, including AI and IoT, for improved enforcement and environmental surveillance (Walther et al. 2020).

4.4. Conclusions

This section critically examined the structural deficiencies in the Marine Pollution Control Act applicable in Taiwan, focusing on liability systems, insurance mechanisms, port oversight, and interagency collaboration. Drawing on the best practices of Japan and South Korea, it offers a set of evidence-based policy reforms aimed at enhancing marine environmental governance in Taiwan. The findings affirm the urgency of harmonizing applicable regulations within the jurisdiction with international norms to effectively address escalating marine pollution threats (Nordquist and Nandan 2011).

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

5.1. Current Status of and Challenges in Taiwan’s Marine Pollution Control

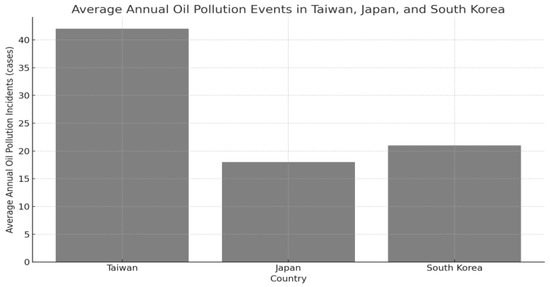

The data presented in Figure 2 demonstrate that Taiwan records 42 annual oil pollution incidents, which exceeds the numbers of Japan and South Korea with 18 and 21 incidents, respectively (MLIT Japan 2022). The data demonstrate fundamental weaknesses in Taiwan’s oil spill prevention systems and its enforcement capabilities and emergency response coordination between agencies (Ocean Affairs Council 2023b; MERRAC/NOWPAP Korea Report 2021). This situation requires immediate action to establish strict liability standards, create a jurisdiction-wide oil pollution compensation fund, and enhance the Port State Control (PSC) system (Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan 2024; Korea MERRAC Annual Statistics 2023).

Figure 2.

Comparison of average number of annual oil pollution incidents in Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea.

Significant ongoing challenges persist in marine pollution control efforts in Taiwan, such as the absence of a comprehensive liability regime, the lack of a jurisdiction-wide compensation system, weak port inspection enforcement, and limited interagency coordination (Chen 2003; Chiang 2018). Under the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC), shipowners are held strictly liable for pollution damage, obligating them to bear the cost of cleanup and compensation, regardless of fault (IMO 1992). Complementing the CLC, the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund (FUND) ensures prompt and adequate victim compensation following large-scale pollution events (Stokke and Thommessen 2013).

However, the Marine Pollution Control Act applicable in Taiwan does not yet fully align with these international norms. As a result, affected parties may face delays or shortfalls in compensation following pollution incidents occurring in Taiwan (Wei 2002). Regarding port regulation, the MARPOL 73/78 requires jurisdictions to establish a Port State Control (PSC) regime to inspect incoming foreign vessels for environmental compliance (IMO 1978). Current PSC implementation remains partial, with some vessels entering ports in Taiwan without meeting international pollution prevention standards (Walther et al. 2021).

It is the major problem that the weakness of institutional control capacities and the limited implementation of Port State Control (PSC) in Taiwan. Some challenges as follows:

- (a)

- Fragmented maritime administration: the distribution of powers between the Ocean Affairs Council, the Ministry of the Environment and the Ministry of Transport, among others, leads to overlap and lack of coordination, hindering the implementation of efficient controls.

- (b)

- Lack of trained inspectors: no information is provided on the number, level of training or resources of inspectors responsible for environmental supervision in ports and on board ships, nor are the consequences of possible inadequacies analyzed.

- (c)

- Budgetary and technical constraints: the article mentions the need to strengthen control and surveillance mechanisms but does not specify budgetary or technological shortcomings that may restrict the ability to respond to incidents or to properly inspect national and foreign-flagged ships.

- (d)

- Systemic causes of ineffectiveness: the structural roots of governance weakness, such as the absence of a systematic administrative culture of environmental compliance, the low priority given to environmental protection, and poor inter-agency coordination, are not sufficiently explored.

5.2. Lessons from International Best Practices

Japan has developed a rigorous port governance system and comprehensive oil spill compensation mechanisms. Under the CLC and FUND frameworks, Japanese law mandates that all incoming vessels maintain liability insurance and participate in a national compensation scheme (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2023). Moreover, Japan’s PSC enforcement is stringent: foreign vessels that are in violation of environmental standards face severe penalties, including large fines or denial of port access (Walther et al. 2021). Authorities in Taiwan could adopt similar protocols to strengthen its maritime oversight and emergency response systems (Ministry of Transportation and Communications n.d.).

In contrast, South Korea stands out for its regional collaboration and integration of smart technologies. Through active engagement in the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP), South Korea has promoted transnational pollution monitoring and joint emergency responses (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2023). The Korean government has also implemented IoT and AI systems to monitor marine environments in real time and ensure rapid intervention when pollution events occur (Walther et al. 2020). Local agencies in Taiwan may benefit from these initiatives by pursuing regional partnerships and leveraging digital technologies to enhance the efficiency of their pollution responses (Ocean Affairs Council 2023b).

5.3. Policy Directions for Taiwan

Given the inability to formally accede to core international maritime conventions such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), it is recommended that the government adopt a non-party voluntary compliance strategy. This strategy should include three institutional measures aimed at achieving functional equivalence, thereby enhancing the legitimacy and credibility of Taiwan’s marine governance framework in the international community.

- Measure One: Establish quasi-accession criteria and a regulatory compliance checklist. Authorities in Taiwan should formulate a Jurisdictional–International Regulatory Mapping Table to regularly assess the consistency between its marine environmental laws and the core obligations under the UNCLOS, MARPOL, and Civil Liability Convention (CLC). Through this legal mapping mechanism, Taiwan can present a transparent compliance alignment that facilitates the assertion of equivalent compliance in international cooperation contexts.

- Measure Two: Promote shadow reporting and voluntary self-assessments.Drawing on the practices of the Paris Memorandum of Understanding (Paris MoU) and the NOWPAP, local agencies may periodically submit non-party shadow reports or voluntary implementation assessments to international organizations such as the IMO and relevant regional platforms. This enhances both transparency and credibility, enabling Taiwan to engage in de facto participation, even without voting rights, by contributing substantively to technical cooperation and information exchange.

- Measure Three: Implement institutional participation in third-party certification and maritime standards systems. Ports and vessels operating in Taiwan should proactively adhere to internationally recognized standards, including those that are enforced through Port State Control (PSC) regimes and authorized by the IMO. Local operators may also pursue certifications such as the ISM Code, Green Award, or ISO 14001 for shipping, serving as functional substitutes for formal treaty participation and demonstrating a commitment to international maritime environmental governance.

This model of non-party functional participation not only improves institutional compatibility with international regulatory frameworks but also strengthens readiness and credibility for potential future re-engagement in formal treaty negotiations.

In regional mechanisms such as the NOWPAP and PEMSEA, as well as in bilateral agreements, this approach will significantly enhance regulatory credibility in Taiwan, fostering policy implementation and transboundary cooperation.

Taiwan should harmonize its jurisdictional legal framework with international standards such as the Civil Liability Convention (CLC) and the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds (FUNDs) by enacting strict liability regulations, mandating vessel insurance coverage, and establishing a jurisdiction-wide compensation mechanism (IMO 1992; Stokke and Thommessen 2013). Furthermore, implementing a comprehensive Port State Control (PSC) regime is essential to inspect all foreign vessels entering or leaving ports in Taiwan and ensure compliance with MARPOL regulations (IMO 1978). Cross-border environmental cooperation must also be intensified through bilateral and multilateral joint monitoring programs and emergency response mechanisms with neighboring jurisdictions (Walther et al. 2021).

Currently, the lack of integration of marine and land-based pollution management in Taiwan results in legal overlaps and fragmented administration (Chen 2003; Wei and Hsu 2002). A unified interagency coordination platform should be developed, encompassing the Ministry of Environment, Ocean Affairs Council, Ministry of Transportation, and other key stakeholders, to strengthen rapid response capacity (Kao 2011). Technological advancement is also critical: Taiwan should invest in AI, big data analytics, and satellite-based surveillance to enhance its marine pollution detection and enforcement capabilities (Walther et al. 2020). Additionally, Taiwan should deepen its participation in regional marine protection frameworks such as the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP) and strengthen emergency partnerships with other East Asian jurisdictions to elevate its international environmental influence (Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2020; Walther et al. 2021).

5.4. Directions for Future Research

To support the transition in Taiwan toward international best practices in marine environmental governance, future research may explore the following topics:

- Assessment of policy reform effectiveness: investigate the implementation outcomes and effectiveness of Taiwan’s updated marine pollution policies (Ocean Affairs Council 2023b).

- Technological innovation in pollution management: examine the potential of AI, IoT, and big data analytics to strengthen marine pollution surveillance and rapid response systems (Walther et al. 2020).

- Strengthening regional cooperation: analyze Taiwan’s opportunities to expand its role in frameworks such as the NOWPAP and promote regional environmental diplomacy (Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2020).

- Updated and specialized references: including literature on ballast water management, marine biosecurity, the effectiveness of PSC inspections, and international governance in contexts of diplomatic exclusion will provide a robust and relevant theoretical and bibliographical basis for the specific problems facing this jurisdiction.

5.5. Conclusions

This jurisdiction faces substantial gaps in its marine environmental governance, particularly in liability and insurance enforcement, port regulation, interagency coordination, and the integration of smart technologies and regional cooperation strategies (Chiu 2003; IMO 1992; Stokke and Thommessen 2013). Drawing on international best practices from Japan and South Korea, the jurisdiction can enact progressive reforms to align its marine pollution control system with global standards. These reforms will be crucial in safeguarding marine ecosystems and securing the sustainable development of oceanic resources (Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2020; Ma 2007; Walther et al. 2021).

6. Conclusions

This study conducted an in-depth analysis of the jurisdiction’s marine pollution prevention policies and legal frameworks. The findings reveal that although the current system has established a preliminary structure, significant gaps remain in legal frameworks, enforcement mechanisms, and international cooperation (Chen 2003). Compared with international standards, this jurisdiction still requires improvements in areas such as liability attribution, insurance mechanisms, port monitoring, and interagency coordination to ensure effective marine pollution prevention (Wei and Hsu 2002). Strengthening these aspects will enhance the comprehensiveness and operational efficiency of the jurisdiction’s regulatory framework for marine pollution control.

6.1. Research Findings and the Need for Policy Reform

This study identifies five core challenges in the jurisdiction’s marine pollution governance:

- Deficiencies in Legal Liability MechanismsInternational frameworks such as the Civil Liability Convention (CLC) and the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund (FUND) establish strict liability and financial compensation mechanisms to guarantee redress for pollution victims (IMO 1992; Stokke and Thommessen 2013). This jurisdiction has not fully adopted these instruments, lacking a mandatory insurance regime and a jurisdiction-wide compensation fund (Wei and Hsu 2002).

- Inadequate Port Regulation and Control of Foreign VesselsUnder the MARPOL 73/78, states must conduct pollution inspections on foreign vessels through Port State Control (PSC) systems (IMO 1978). The PSC regime is only partially implemented, hindering effective oversight of vessel-sourced pollution (Tseng and Ng 2021).

- Weak Interagency Coordination and Environmental MonitoringThe Marine Pollution Control Act is insufficiently integrated with other environmental legislation such as the Waste Disposal Act and the Water Pollution Control Act, resulting in overlaps and regulatory loopholes (Ocean Affairs Council 2020). Moreover, the absence of a centralized environmental monitoring system limits the jurisdiction’s capacity for timely and coordinated responses (Ministry of Environment Taiwan n.d.).

- Insufficient Public Participation and Environmental EducationCitizen science initiatives have been widely adopted in the EU and Japan to empower public environmental monitoring (Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2020; Ma 2007). There is a need to increase environmental education, public data transparency, and community engagement to improve grassroots supervision and awareness (Walther et al. 2021).

- Limited International and Regional Governance EngagementThe inability to formally participate in instruments such as the UNCLOS restricts its global engagement and capacity to address transboundary marine pollution (United Nations 1982; Nordquist and Nandan 2011). Taiwan should prioritize cooperation through regional mechanisms, such as the NOWPAP, and informal multilateral partnerships (Valdes 2017). Some challenges include the following:

- (a)

- Limited participation in regional forums: unlike Japan and Korea, Taiwan cannot legally sign multilateral instruments, which limits its involvement and access to joint protocols, databases, and transnational response exercises.

- (b)

- Practical implications: the consequence of this marginalization is a reduced capacity for coordinated response in the event of spills and restricted access to shared technical, scientific and logistical resources in the region.

- (c)

- Impact on diligence and compliance: the lack of recognition also hinders the validation and reciprocity of Taiwan’s controls on foreign vessels and the international recognition of its compliance standards and inspection protocols.

6.2. Future Outlook

In response to escalating marine environmental threats, the jurisdiction should pursue the following strategic reforms:

- Legal Reform and Mandatory Insurance MechanismFollowing the models of Japan and South Korea, the jurisdiction should institute compulsory liability insurance for vessels operating in its jurisdiction and establish a jurisdiction-wide oil pollution compensation fund (Wang 2011; Stokke and Thommessen 2013).

- Application of Technology and Enhanced MonitoringAdvanced technologies such as AI, IoT, and big data should be applied to real-time marine pollution detection and early warning systems (Rayner et al. 2019). South Korea’s smart monitoring platform demonstrates the potential for AI-driven vessel emission tracking and hotspot prediction (Walther et al. 2021).

- Deepening Regional and International CooperationThis jurisdiction should expand its collaboration with the NOWPAP and other regional frameworks to boost its cross-border pollution response capabilities (Walther et al. 2020). In parallel, this jurisdiction should leverage academic and NGO participation to amplify the jurisdiction’s informal influence in global marine environmental dialogs (DeSombre 2010).

- Strengthening Public Participation and Environmental EducationThrough curricula, social media, and citizen science platforms, public awareness of marine pollution should be elevated (Walther et al. 2021). Collaborative programs involving the government and private entities should be encouraged to bolster corporate social responsibility (CSR) in marine conservation (Biermann and Pattberg 2012).

6.3. Summary

This study has identified persistent regulatory, institutional, and technological gaps in the marine pollution control regime in Taiwan. These include legal inconsistencies, a lack of enforcement capability, fragmented interagency structures, and limited regional engagement (Chiang 2018; United Nations 1982; IMO 1978). To address these challenges, The jurisdiction must urgently align its jurisdictional legislation with global conventions and enhance its implementation capacity through systemic reforms (Wei and Hsu 2002; Ocean Affairs Council 2020; Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2020).

By fostering cross-sectoral collaboration, embracing innovation in environmental monitoring, and reinforcing regional partnerships, this jurisdiction can secure the long-term sustainability of its marine ecosystems (Chiu 2003; Walther et al. 2020, 2021).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.L. and Y.-C.W.; methodology, S.-H.L.; software, S.-H.L.; validation, S.-H.L. and Y.-C.W.; formal analysis, S.-H.L.; investigation, S.-H.L.; resources, S.-H.L.; data curation, S.-H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-H.L.; writing—review and editing, S.-H.L.; visualization, S.-H.L.; supervision, Y.-C.W.; project administration, S.-H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that it does not involve any human participants, animal subjects, or the collection of personally identifiable information. The research is based solely on the analysis of publicly available legal documents, policy reports, and secondary data sources.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bergesen, Hans Olav, Gunnar Parmann, and Øystein B. Thommessen. 2018. International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage 1969 (1969 CLC). In Year Book of International Co-Operation on Environment and Development. London: Routledge, pp. 104–5. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, Frank, and Philipp Pattberg, eds. 2012. Global Environmental Governance Reconsidered. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Chih-Yung. 2003. General Principles of Environmental Law. New Taipei City: Wu-Nan Book Publishing Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Hung-Chih. 2018. International Law of the Sea. Singapore: Yuan Chao Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Wai-Yin. 2003. Theory and Practice of Coastal Management. New Taipei City: Wu-Nan Book Publishing Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- DeSombre, Elizabeth R. 2010. Global Environmental Institutions. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Doud, Alden Lowell. 1972. Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage: Further Comment on the Civil Liability and Compensation Fund Conventions. Journal of Maritime Law and Commerce 4: 525. [Google Scholar]

- Ferse, Sebastian C. A. 2023. Grand challenges in marine governance for ocean sustainability in the twenty-first century. Frontiers in Ocean Sustainability 1: 1254750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haward, Marcus, and Andrew Jackson. 2023. Antarctica: Geopolitical challenges and institutional resilience. The Polar Journal 13: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yu. 2017. The International Law of the Sea. Shanghai: Xin Xue Lin Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). 1978. International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78). London: International Maritime Organization. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Prevention-of-Pollution-from-Ships-(MARPOL).aspx (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). 1992. International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC). London: International Maritime Organization. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-on-Civil-Liability-for-Oil-Pollution-Damage.aspx (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2020. Diplomatic Bluebook 2020; Tokyo: MOFA.

- Kao, Jui-Chen. 2011. Marine Policy and Environmental Management in Taiwan. Cardiff: Cardiff University. [Google Scholar]

- Korea MERRAC Annual Statistics. 2023. Korea MERRAC Annual Statistics. Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan. Available online: https://merrac.nowpap.org/merrac/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ma, Fong-Yi. 2007. The Relationship between Marine Environmental Protection and Ship Pollution Prevention Conventions. Seafarer’s Monthly 408: 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- MERRAC/NOWPAP Korea Report. 2021. NOWPAP MERRAC. Available online: https://merrac.nowpap.org/merrac/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ministry of Environment Taiwan. n.d. Official Website of the Ministry of Environment. Available online: https://www.moenv.gov.tw/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2023. Japan’s “Marine Initiative” toward Realization of the Osaka Blue Ocean Vision. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/content/900457446.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan. 2024. Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/en/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ministry of Transportation and Communications (MOTC). n.d. Laws and Regulations Database. Available online: https://motclaw.motc.gov.tw/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- MLIT Japan. 2022. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/en/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Nordquist, Myron H., and Satya N. Nandan, eds. 2011. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982, Volume VII: A Commentary. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ocean Affairs Council. 2020. National Ocean Policy White Paper; Taiwan: Ocean Affairs Council.

- Ocean Affairs Council. 2023a. 2022 Annual Report on Marine Debris Management in Taiwan. Available online: https://www.oca.gov.tw (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ocean Affairs Council. 2023b. Ocean Affairs Council. Available online: https://www.oac.gov.tw/en/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ocean Affairs Council (OAC). n.d. Official Website of the Ocean Affairs Council. Available online: https://www.oac.gov.tw/ch/index.jsp (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Rayner, Ralph, Chris Jolly, and Carl Gouldman. 2019. Ocean observing and the blue economy. Frontiers in Marine Science 6: 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Yi-Che. 2020. Taiwan’s progress towards becoming an ocean country. Marine Policy 111: 103725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokke, Ole S., and Øystein B. Thommessen. 2013. International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage 1971 (1971 Fund Convention). In Yearbook of International Cooperation on Environment and Development 2001-02. London: Routledge, pp. 130–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, Pei-Hsin, and Man Ng. 2021. Assessment of port environmental protection in Taiwan. Maritime Business Review 6: 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 1982. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, Office of Legal Affairs. 2015. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: A Historical Perspective. New York: United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_historical_perspective.htm (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Valdes, Luis. 2017. Global Ocean Science Report: The Current Status of Ocean Science around the World. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259353 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Walther, Bruce A., Nien-Hwa Yen, and Chen-Sheng Hu. 2021. Strategies, actions, and policies by Taiwan’s ENGOs, media, and government to reduce plastic use and marine plastic pollution. Marine Policy 126: 104391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, Bruce A., Takashi Kusui, Nien-Hwa Yen, Chen-Sheng Hu, and Hsiang Lee. 2020. Plastic pollution in East Asia: Macroplastics and microplastics in the aquatic environment and mitigation efforts by various actors. In Plastics in the Aquatic Environment—Part I: Current Status and Challenges. Edited by Friederike Stock, Georg Reifferscheid, Nicole Brennholt and Evgeniia Kostianaia. Cham: Springer, pp. 353–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Hui. 2011. Civil Liability for Marine Oil Pollution Damage: A Comparative and Economic Study of the International, US and Chinese Compensation Regime. Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Law International BV. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Cheng-Fu. 2002. International and Domestic Law on Marine Pollution Prevention. Shenzhou: Shenzhou Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]