1. Introduction

1.1. Civil Law Colleges in the Shanghai University Rankings and Times Higher Education

A short look at the top 100 law colleges in two of the most reputable university rankings, the Shanghai Ranking of World Universities (Shanghai University Rankings) and Times Higher Education (THE), shows the relevance of this study. While both rankings are mainly focused on universities, their ranking per subject includes rankings of law colleges. The highest-ranked university from a civil law country in the Shanghai Global Ranking of Academic Subjects of 2024 for law (Shanghai ranking) is the Dutch Leiden University, ranked 26. There are only 3 universities in the top 50 universities ranked by law that belong to civil law countries, all 3 from The Netherlands. Overall, only 12 out of the top 100 universities ranked by law belong to civil law countries. Interestingly, the universities from the two arguably most influential civil law countries, France and Germany, do not appear in the top 100. The University of Munich from Germany is ranked 101–150, while the first and only French university in the top 500 only appears in the ranks 201–300, the same as the University of Vienna from Austria. When it comes to other influential civil law countries, the University of Bologna is ranked 75–100; the University of Oslo and the University of Copenhagen are ranked 75–100, the same as the University of Hong Kong and the City University of Hong Kong; and the Autonomous University of Madrid and Complutense University of Madrid are ranked 101–150, the same as the University of Stokholm. There are no Latin American universities on the list by law subject.

A closer look at the ranking methodology (

Shanghai Ranking’s 2024) shows why universities from civil law countries cannot be ranked any better by the subject of law. First, the bibliometric data is collected from the Web of Science (WoS). As will be presented in detail further below, there are currently an insignificant number of journals indexed in WoS in private or public law publishing papers from a civil law perspective. When looking at the concrete criteria, they are very research-oriented and divided into world-class faculty, world-class output, high-quality research, research impact, and international collaboration. The world-class faculty category is estimated based on four indicators: international academic award laureates (Laureate), highly cited researchers (HCR), chief editors of international academic journals (Editor), and international academic organization leadership (Leadership). However, for different subjects, some of these indicators are not considered, so for law, the only indicator measured is the chief editors of international academic journals. World-class output for law is measured solely based on the Academic Excellence Survey, which identified only two journals,

Harvard Law Review and

The Yale Law Journal. Again, civil law publications are completely left out. The high-quality research indicator is based on journals ranked in the WoS in the highest category (Q1), where the research impact counts citations only within WoS, and international cooperations are counted only within WoS.

As a law college belonging to a civil law country, it makes no sense to try to compete in the Shanghai ranking, and vice versa. The Shanghai ranking cannot be understood as a world ranking for the law subject until it finds an appropriate way to include civil law education on equal footing. This will be shown by the study below.

When looking at another prominent ranking that is gaining more and more attention, the Times Higher Education (THE) ranking, it shows that 18 universities from civil law countries are in the top 50, and overall, 37 are in the top 100. While again the Dutch universities lead the way with 4 universities in the top 50, there are 2 German universities in the top 50, the best French university placed 61, the University of Vienna is at 45, the University of Bologna is at 38, Oslo and Lund are at 36, Copenhagen is at 48, and 2 Chinese universities are placed within top 20. Brazil Sao Paolo is 58, while 14 universities from Colombia, Chile, and Peru are represented in the top 500.

What is the main reason for the more prominent inclusion of universities from civil law countries in the law subject ranking in the THE rankings, when compared with the Shanghai rankings? The THE rankings examine research-related criteria based on the data gathered in Elsevier’s Scopus database, which is considered to be more social sciences-friendly. This paper will analyze in detail below how research on civil law, even in the Scopus database, is still heavily underrepresented but better than in WoS. In addition, the methodology used in THE on the law subject is not solely research focused as it is in the Shanghai rankings and includes criteria such as teaching, weighted 32.2%; research environment, weighted 29.8%; research quality, weighted 25%; industry, weighted 4%; and international outlook, weighted 9% (

THE 2025a).

One of the main goals of this paper is to examine the extent to which journals publishing papers written from a civil law perspective are even represented in the WoS and Scopus databases and how it impacts university rankings but also the careers of many academics in law.

1.2. How Does It Look When You Want to Publish Legal Research from a Civil Law Perspective in a Highly Ranked Journal in WoS or Scopus?

Let us discuss the following scenario. You are a lawyer in a civil law jurisdiction. There is new legislation, a judicial decision, or another development in your country that you believe has an important impact on the legal theory published on that matter. You develop an interest in the topic. You first read and analyze the legal research already published on the matter, and it confirms your initial reasoning; the newly issued legislation or judicial decision truly drifts away from what has been the standard thus far, or there is a research gap in the topic. You develop your arguments, and you want to share your thoughts in a publication. Which options do you have for publishing? The most obvious choice would be to look for a national journal focused on your specific field that is most read in your country. But there may be several reasons why an author may want or may have to opt for a publication in a journal indexed in WoS or Scopus instead. It may be required by the university or research institution where the author is employed, by the national rules for academic promotion, by the criteria for a research grant, or by a research award. It may be that the author is not required to publish in WoS or SCOPUS but wants to reach a wider audience and wants the publication to be more easily searchable and accessible, and the author may aim for international recognition and opportunities for international collaborations, conferences, and projects. In particular, projects and conferences focusing on comparative law, private international law, or dispute resolution may invite authors based on their national law expertise published in a recognized and searchable international database.

The difficult task is to find a list of journals where you can publish classic legal research from a purely national law perspective, on either civil law or public law. The term public law for the purposes of this paper is again understood from the perspective of civil law countries and the admittedly somewhat old-fashioned differentiation between public in private law, which is more systematically established in civil law (

Rosenfeld 2013). As an author, you do not want to make any compromises in your research just to fit a certain indexed journal. The idea is to find journals that do not require the authors to make interdisciplinary research, comparative analysis, or an empirical analysis—just pure legal analysis of the law, legal jurisprudence, or a legal institute from a national perspective. You do not want to compare your country’s legislation with US or UK law, just because most of the journals indexed in WoS or Scopus are published in these countries. Sometimes the legal problem you analyze is not suitable for a comparison with a common law country, or it does not require a comparative analysis at all. Similarly, an empirical analysis, for example, on the social or economic impact of certain legislative changes might be appropriate for some topic but certainly not for all. The question that the study in the paper tries to answer is what options are available for such purely civil law publications, and how does this impact the university rankings?

1.3. The Criteria to Find Journals That Publish Civil Law Papers Indexed in WoS and Scopus

The task for this study was to go through all of the legal journals listed in WoS or Scopus, one by one, and to check at least the last five years of the papers published. The goal was to identify journals in Scopus and WoS that published pure legal research from the perspective of a civil law country. The original focus was purely on private/civil law journals, but while conducting the study, it became clear that public law researchers coming from civil law countries had the same problem. Therefore, the study included both civil and public law publications conducted from the perspective of the civil law theory.

However, there were several limitations to consider. Criminal law journals were not included in the study, as there are numerous criminology journals that allow publishing legal papers with different levels of criminological aspects. An appropriate assessment of the journals on criminology that allow legal aspects to a certain degree, but may or may not publish purely legal research, proved too difficult to assess within this study. Due to the importance of criminal law, it is highly recommended that such a study be conducted within a separate research.

The criteria for selection of journals in WoS and Scopus are the following:

The journal allows publications of pure legal research. The journal may allow but does not require interdisciplinary research or empirical studies.

The journal publishes (not just incidentally) papers on a particular national jurisdiction from a civil law-based country without requiring comparison to U.S. or UK law or any other national law.

The journal does not have to exclusively publish papers in law. But legal publications should not be a rare exception out of the overall number of papers.

The journal does not focus on EU or international legal topics but allows purely national law research. The journal publishes papers in traditional fields of law (as discussed above), rather than having its focus on non-traditional fields of law such as environmental law, data protection, IT law, etc. It also does not focus on fields that are international in nature, such as human rights or intellectual property.

Criminal law and criminology journals are excluded as there are a high number of criminology journals that include criminal law publications to a certain degree, and therefore, publishing is not as restricted as in other traditional fields of law.

The papers for the last five years of each journal have been analyzed to assess if the journal meets the criteria above.

2. Research Questions

With the limitations of the research set above, the research aims to answer several important research questions:

How many civil law journals are indexed in the WoS and SCOPUS compared with other legal journals?

How many of these civil law journals allow publications in languages other than English?

How many journals at all are publishing papers in specific areas of civil law and commercial law in Scopus or WoS?

What is the relationship in percentages between civil law journals in WoS and Scopus and the weak ranking of law colleges from civil law countries in international university rankings such as the Shanghai and THE rankings?

4. Conclusions from the Study on the Position of Civil Law Research Within WoS and Scopus

4.1. Conclusions of the Study on Publishing Legal Research in Languages Other than English

Legal science focuses on the interpretation of particular words, legal terms, that have now been interpreted differently in the new law or by the courts or for which the terminology and legal consequences have changed. Such analysis primarily makes sense in the language to which the words belong. Aiming for a publication in English or an Arabic, Bosnian, or German term that has been interpreted differently by the respective courts of these countries may have importance from a comparative law perspective but misses the primary target audience of lawyers in that country.

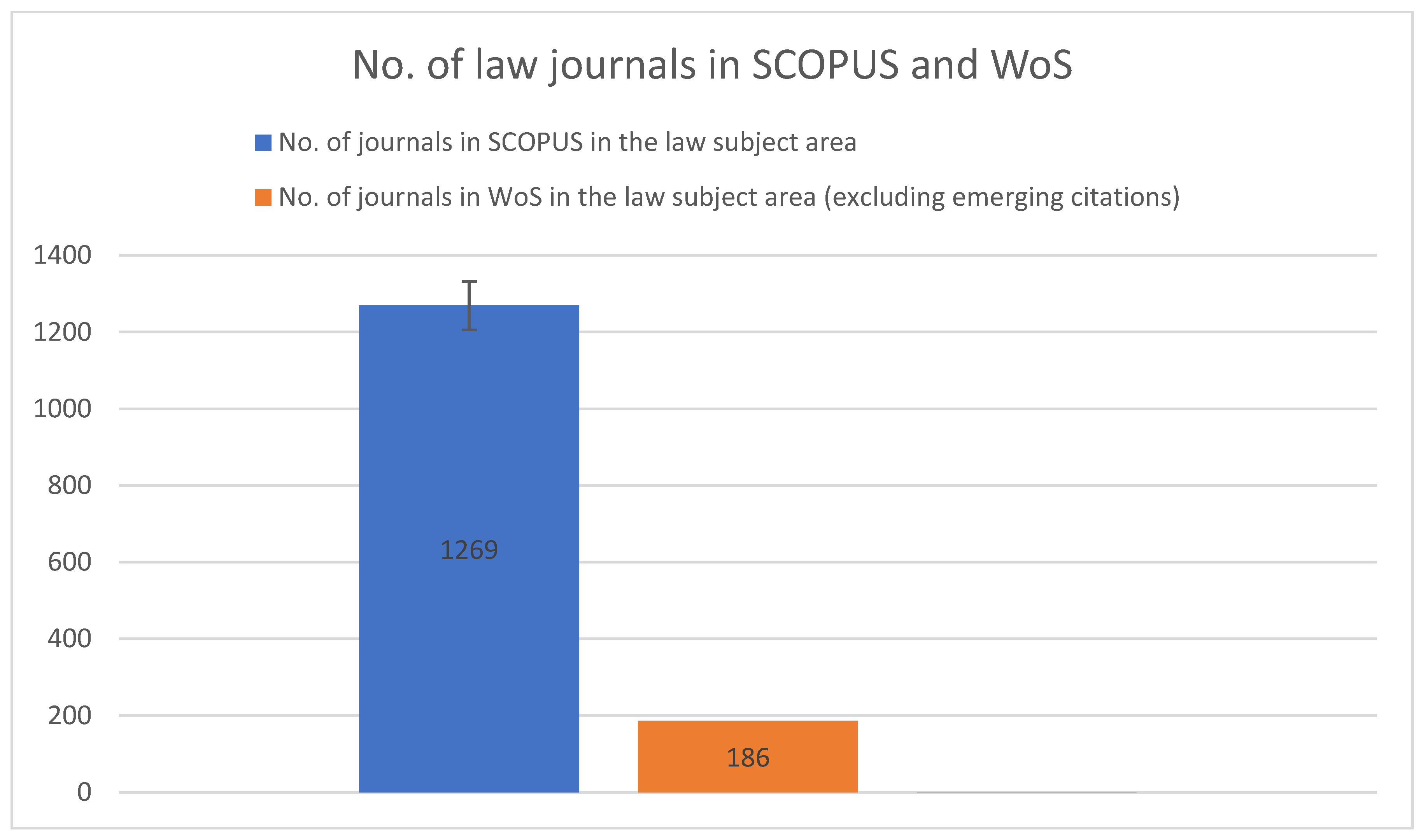

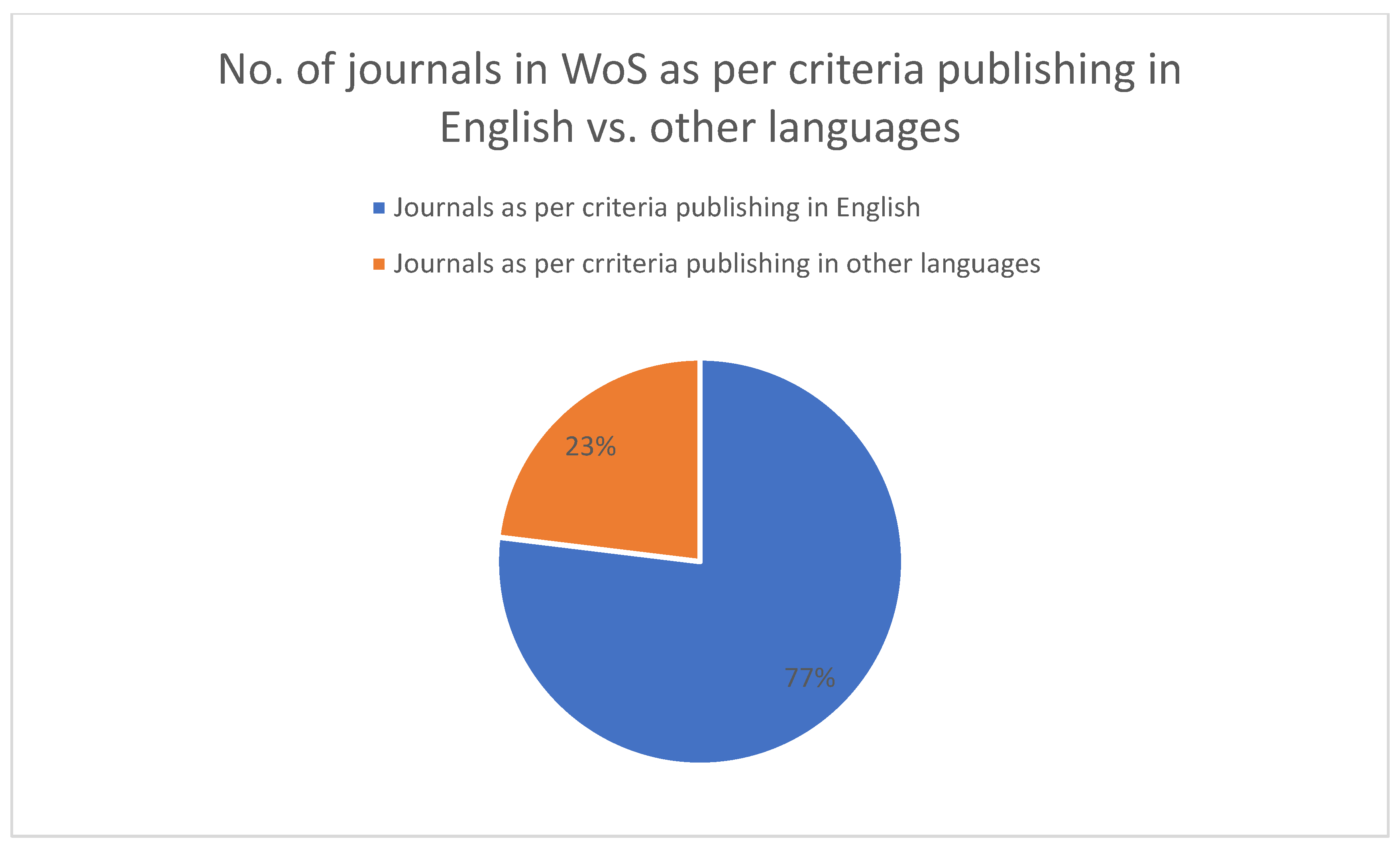

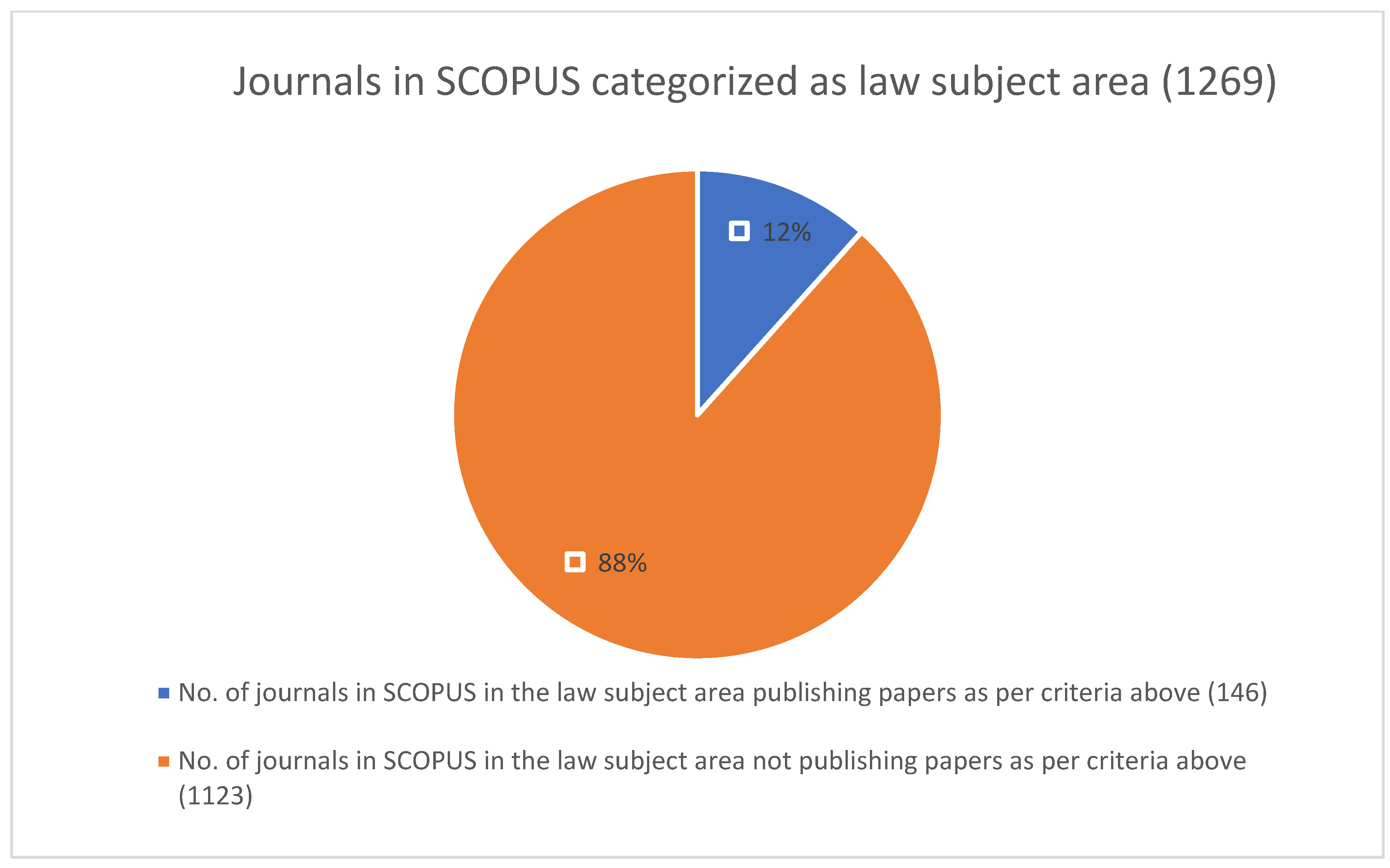

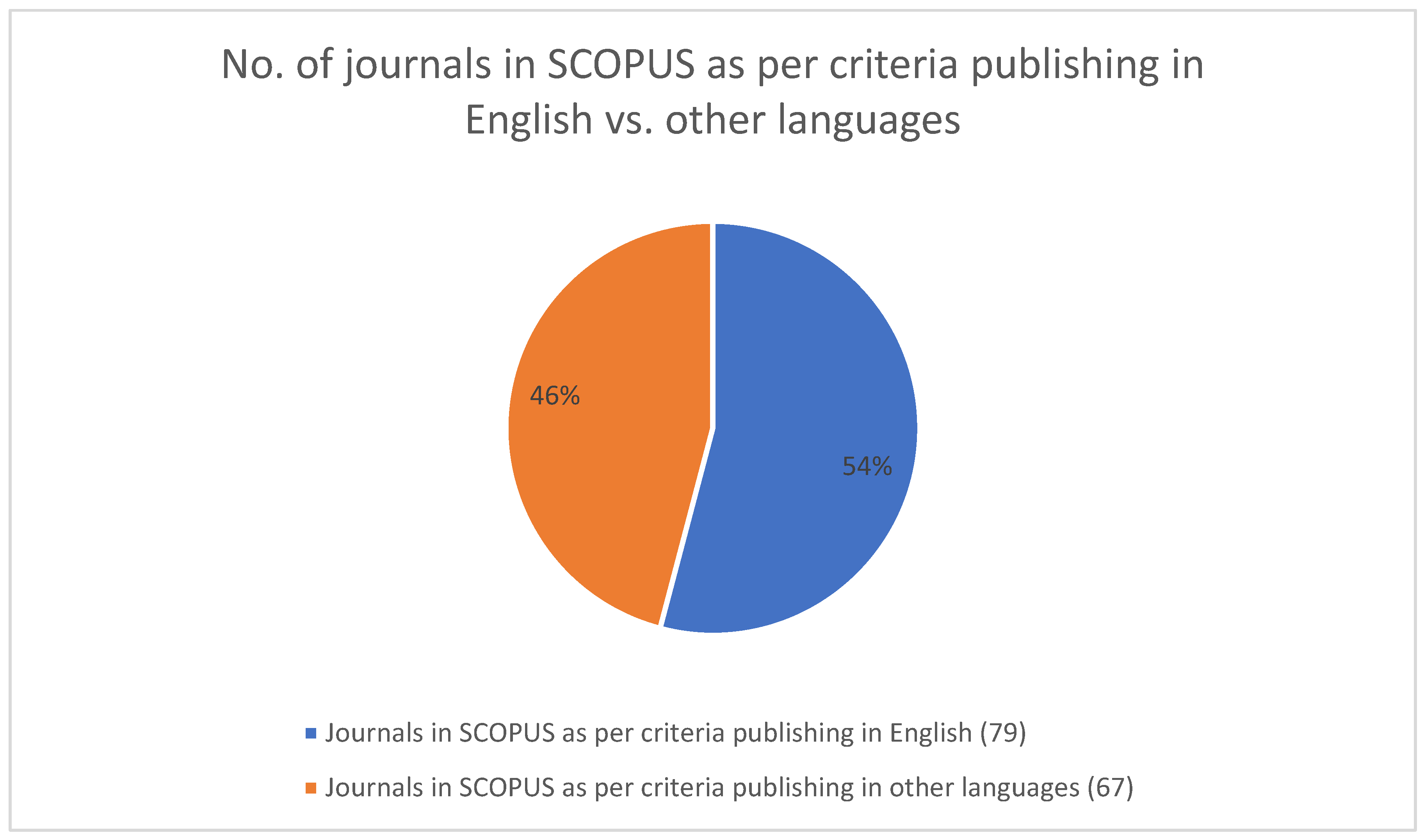

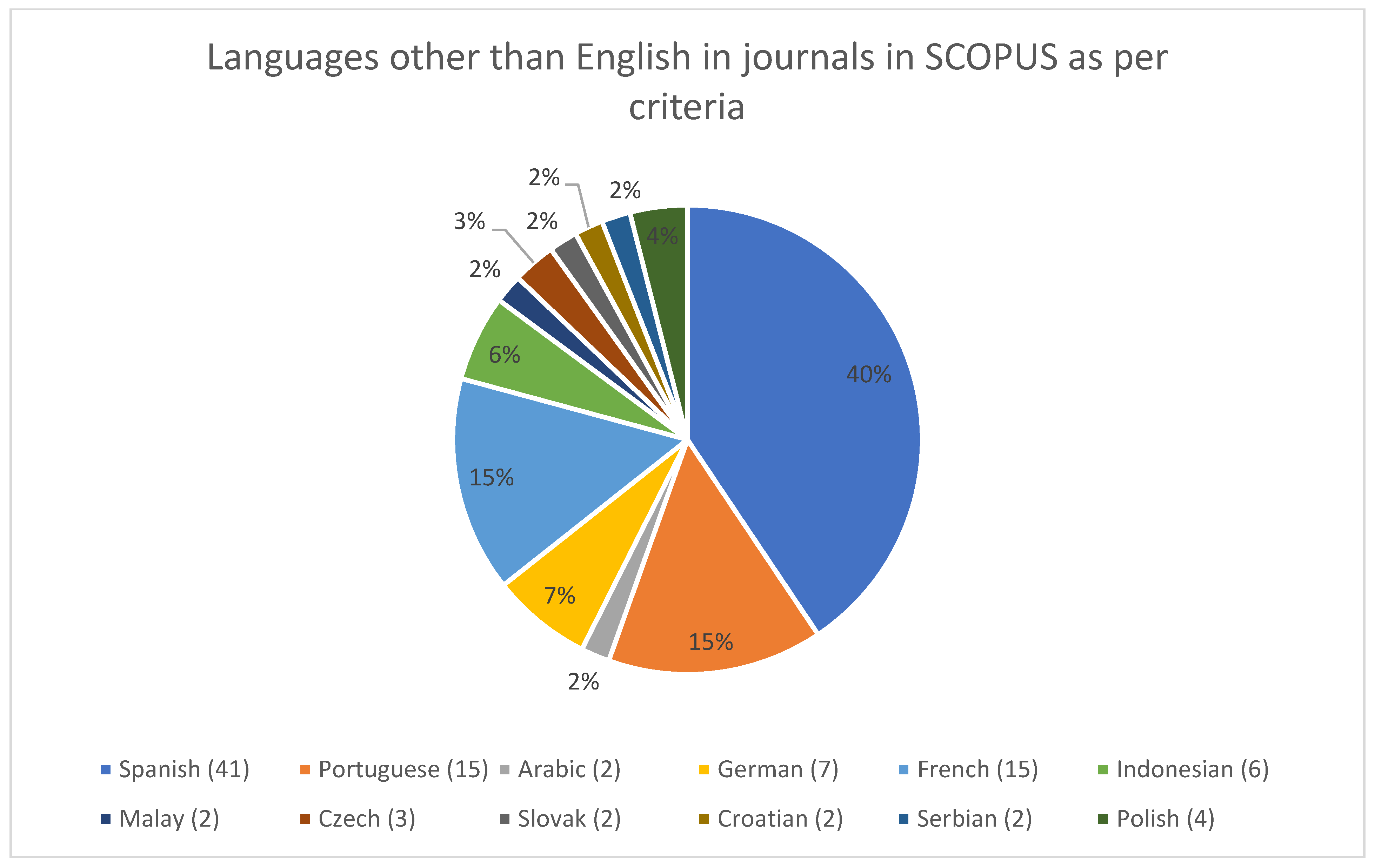

Publishing in any language other than English basically excludes the possibility of publishing in a legal journal in WoS or limits it significantly in Scopus. As an author, one will mostly have to opt for some great national journals that are, however, not listed in WoS or Scopus. The current statistics show that 97.8% of journals in WoS are in the English language. The Scopus database does not show exactly how many journals are published in a foreign language. However, when considering the 1269 journals that are in Scopus classified under law, only 67 journals publish in a language other than English, and most languages are heavily underrepresented.

In a simple search in the Clarivate master list of journals, by including the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), overall, 186 journals are categorized as law. Out of 186 journals in the law category, 182 are in the English language. Out of the other four, three are in Spanish (Anuario de Psicologia Juridica, Revista Chilena de Derecho, and Revista Espanola de Derecho Constitucional), and one is labeled as multilingual (European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context), although all papers are published in English with Spanish abstracts.

To be clear, there are some journals in other languages that do have “Law” in their title, and they publish topics that are at least multidisciplinary, including also legal topics, but are not indexed in WoS for law but for other scientific areas. See, for example, Recht & Psychiatrie, which is in German and has “Law” in its name but is indexed only for psychiatry and criminology/penology. Some further multilingual journals are indexed for law but are categorized only for English as the primary language (see, for example, Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis/Revue d’histoire du droit/The Legal History Review). So it may be that the actual percentage of journals in languages other than English is a bit over 3% but not much higher than that.

At first glance, it may be surprising that 67 out of the 146 law journals indexed in Scopus that are identified by this study allow publications in languages other than English. But it is not surprising at all. The criteria for the choice of journals in this study were to determine journals that allow publication from a civil law perspective, and it is only natural that the majority aim for publications in the official language of the country of the journal. It is commendable that Scopus is indexing more and more law journals publishing in languages other than English.

And what is the number of law journals that are published in legal science outside of Scopus and WoS? It is difficult to obtain actual numbers for many countries. A relatively recent study of 2019 by Van Gestel and Lienhard analyzed legal research in several civil law countries and the UK. And the numbers are quite astonishing. The number of journals in Germany is estimated to be over 1300 (

Purnhagen and Petersen 2019); in Italy, around 250 journals (

Peruginelli 2019); somewhat over 100 journals in Switzerland (

Lienhard et al. 2019); etc. When comparing these numbers to the number of journals from these countries indexed in WoS and Scopus, it becomes clear that only a small fraction of legal journals around the globe are included in WoS and Scopus.

Now let us take a civil law scholar from China, Hungary, Sweden, Greece, Bulgaria, Albania, and many other civil law countries without a single law journal in their native language indexed in WoS or Scopus. The question is not if the legal researchers from those countries are capable of publishing in English but rather if their target audience is capable or willing to read legal analysis about their national legal problems in English and, even more so, if English is the appropriate language to analyze local legal terminology and interpretation. Therefore, can we compare law colleges from countries whose national legal journals are included in neither WoS nor Scopus, based on research by only considering WoS or Scopus? In my firm view, we cannot, and we should not, as the results will simply be wrong.

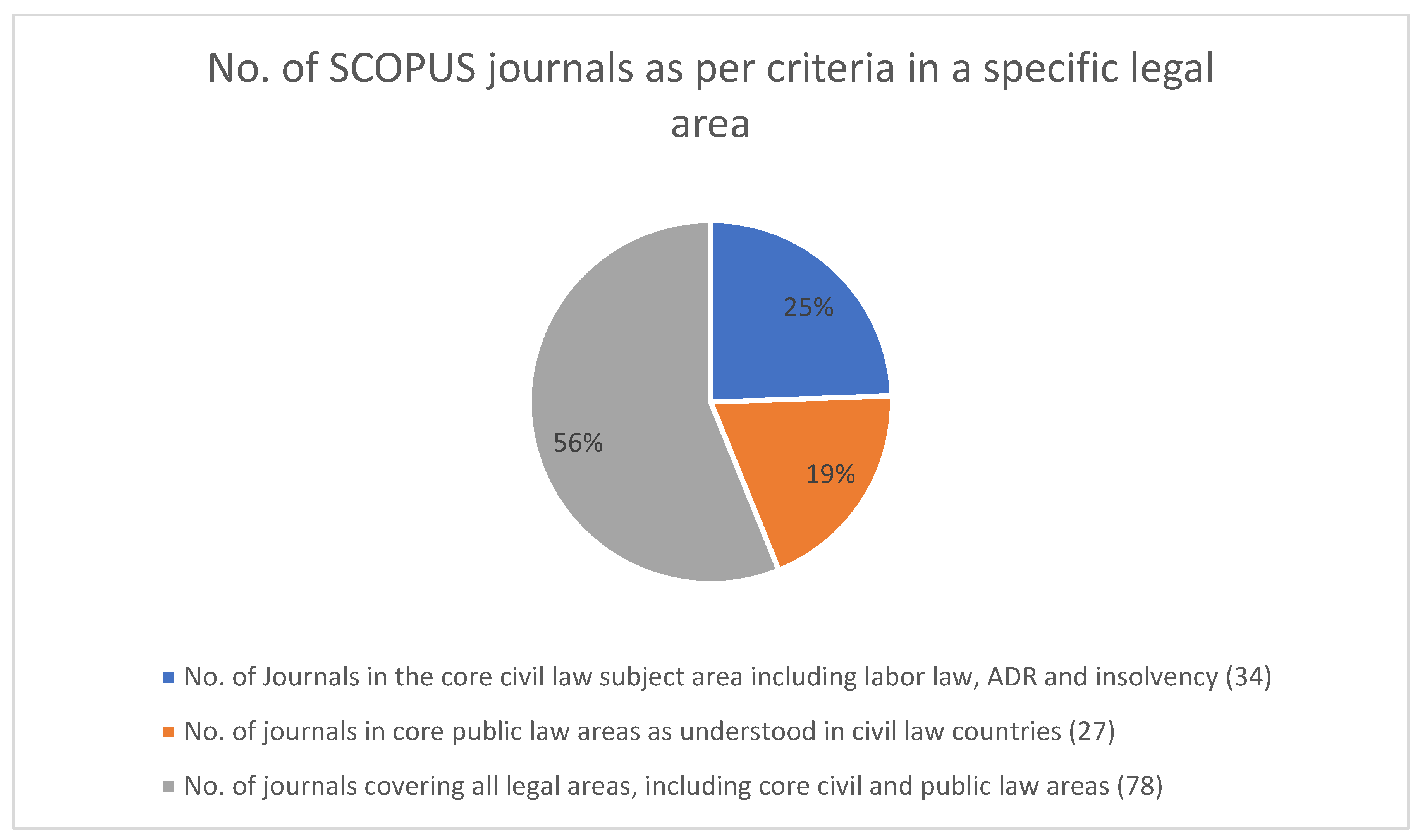

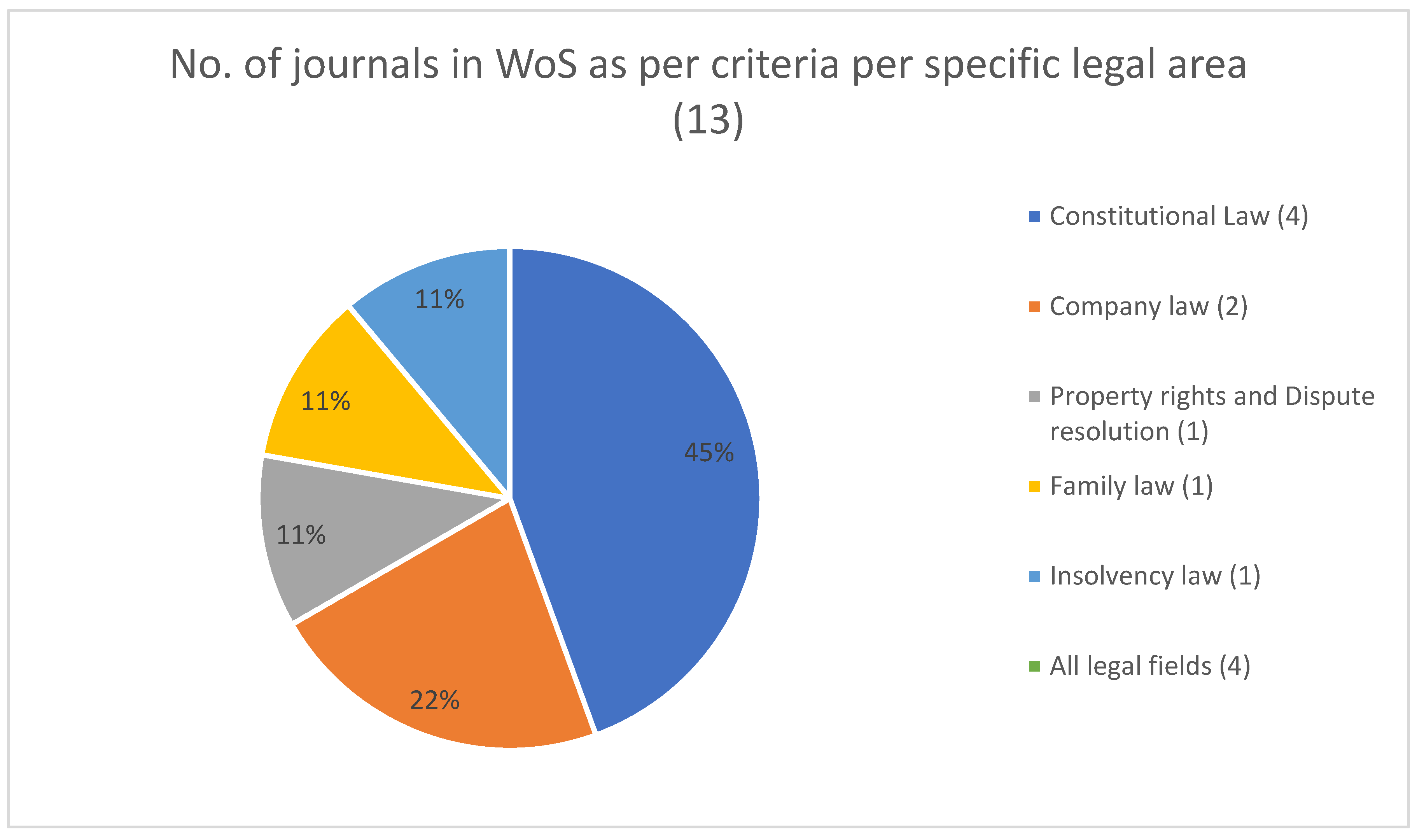

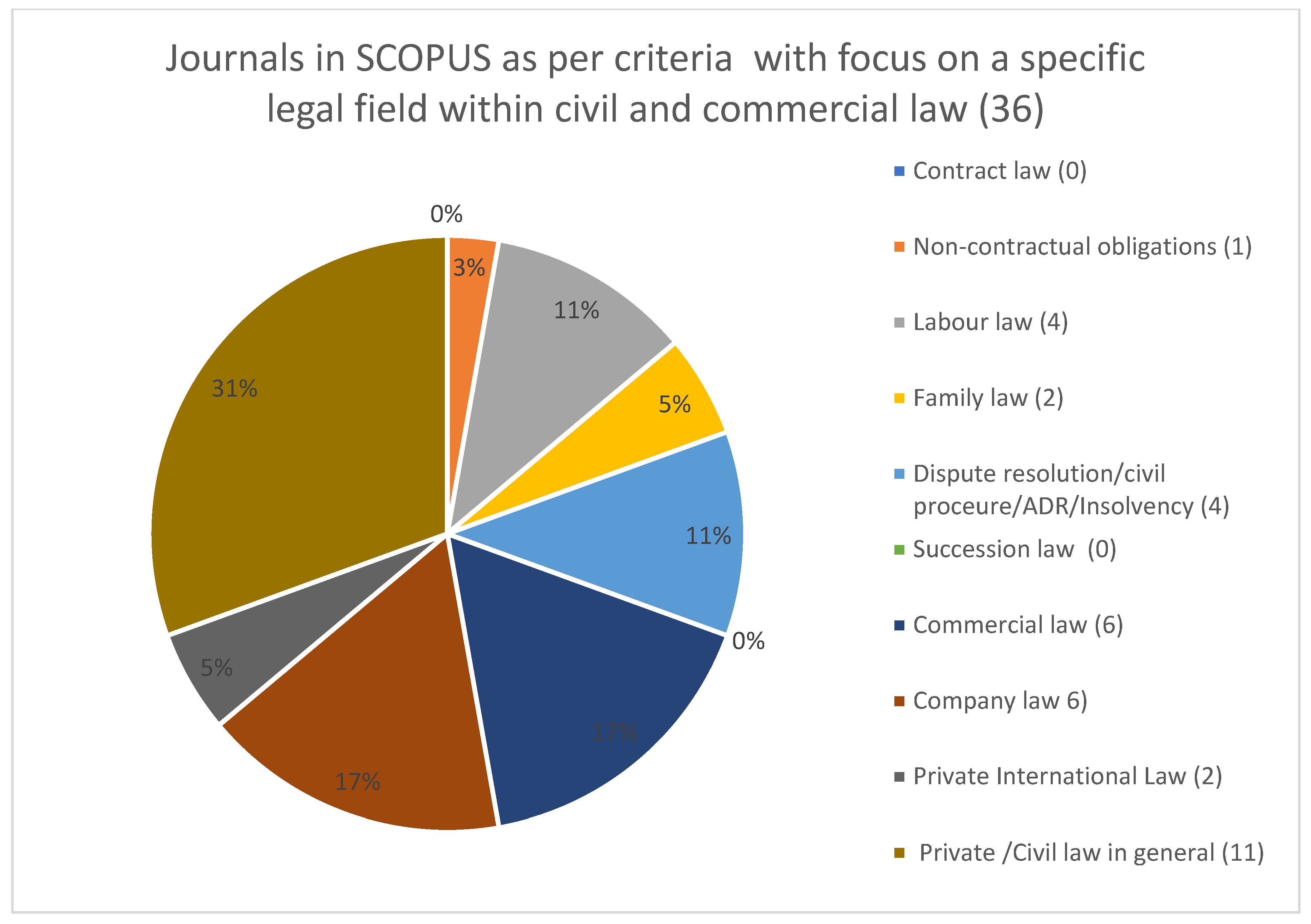

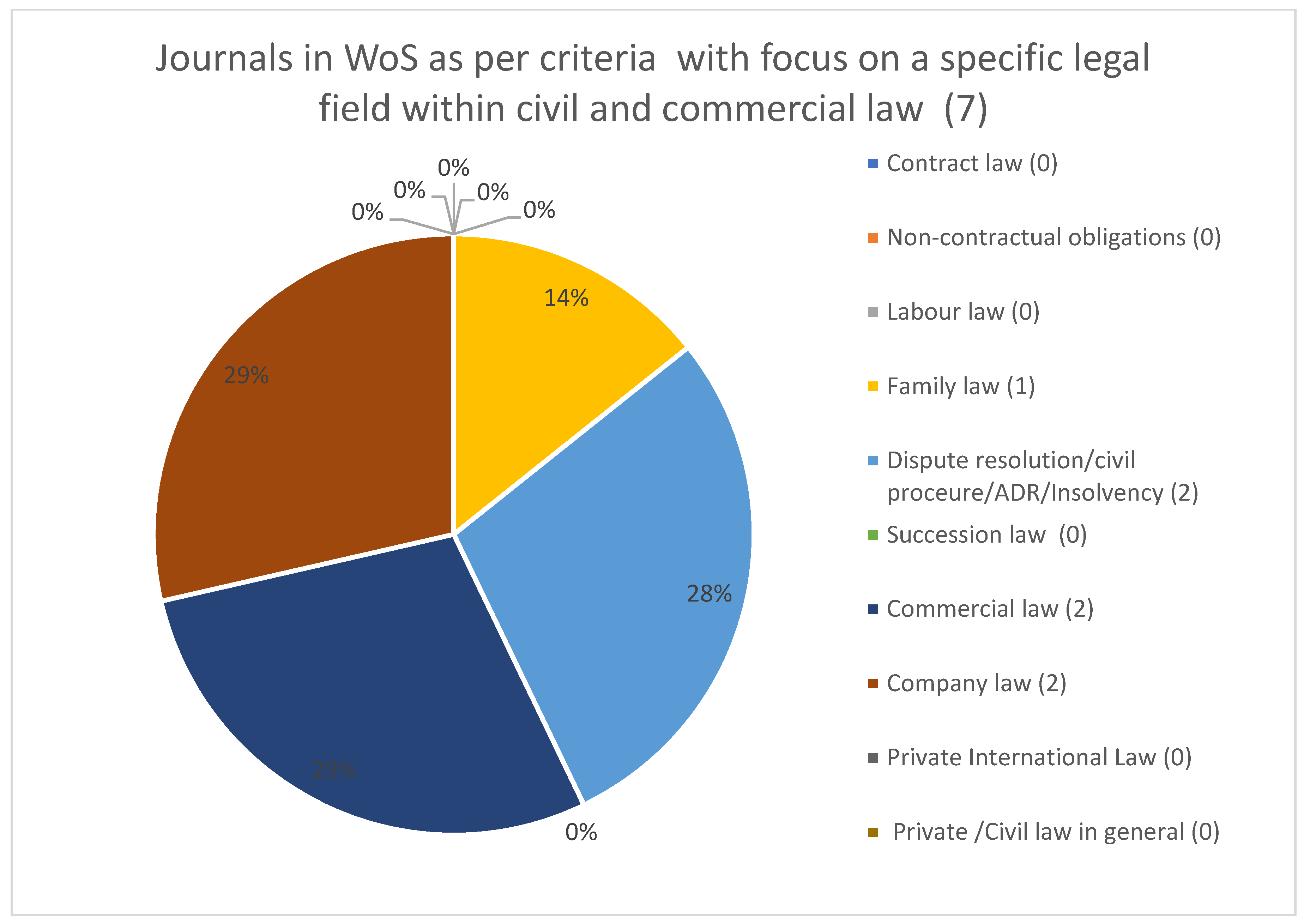

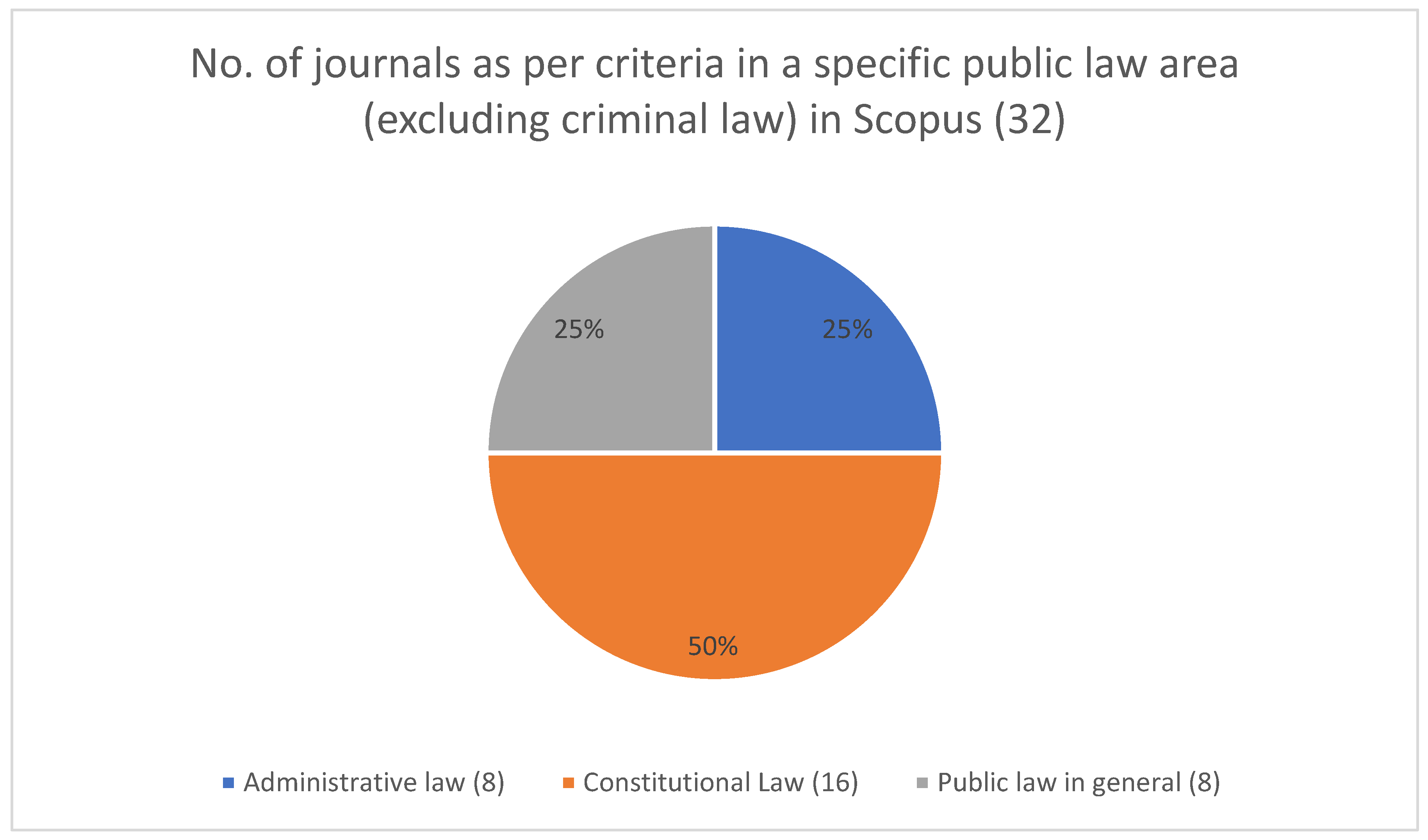

4.2. Conclusions Related to the Legal Area of the Publications

The number of journals that fulfill the above criteria in WoS is so low that, automatically, very few legal areas are covered in WoS. From a civil law perspective, it is most noticeable that the core area of contractual and non-contractual obligations is not covered in WoS. The situation is not much better in Scopus, as only one journal covers non-contractual obligations. But in Scopus, there are 11 journals covering civil law topics in general, while none of these journals are listed in WoS.

To get a bit of perspective, this means that if you want to publish research in the Czech language, you have to choose from three journals. However, according to my analysis, only two of them publish civil law, including all other fields, whereas one specializes in public law. Let us assume that a strong academic in law would like to publish at least three to five papers a year; it would not be possible for a Czech legal scholar to have their full research published in Scopus even for one year. None of the journals would accept the same author issue after issue, which means that the author has to publish the majority of their research outside of the Scopus and WoS journals. As a result, the academic work of the most valuable legal scholars not published in English and published within their core area of expertise will not be published in WoS or Scopus and will not contribute to the university rankings in the Shanghai ranking or THE ranking. This simply means that relying on WoS, or even on Scopus, will not make an accurate ranking related to universities in civil law countries.

4.3. Conclusions Regarding the Civil Law in the University Rankings

The Shanghai ranking and the THE ranking, as well as any other university ranking promoting itself to be a world ranking, need to find a proper way to include civil law journals in their evaluation and to place them on equal footing with the common law system.

The journal impact factor (JIF) is what determines the rank of the journal in the WoS. A publication in a higher-ranked journal directly impacts the university rankings as they are relying on the data from WoS and Scopus. So, how is JIF calculated? It considers the citations from the last two years as a maximum. So basically, the journals are solely ranked based on how many times papers from that journal are cited in the first two years after publishing, while the later citations have no impact on the ranking. If we want to calculate the JIF for a particular year (e.g., 2025), we take citations from 2025 but only related to papers published in the last two years (e.g., 20), and we divide them by the number of papers published by that journal in the last two years (e.g., 40). In this example, the JIF for 2025 will be 0.5.

The Scopus database uses Citescore instead of JIF. It works essentially the same, but the citations from papers published in the last four years are considered, so any citation of a paper published more than four years ago does not contribute to journal rankings. Citescore also includes a larger range of types of documents, such as conference proceedings and book chapters, which makes Scopus more social sciences-friendly.

On average, the JIF of law journals is significantly lower than the JIF of most other sciences. The highest-ranked journal identified by this study to publish papers from a civil law perspective is Asia Pacific Law Review, with a JIF of 1 (as of 1 April 2025). The highest-ranked journal identified by this study to publish papers from a civil law perspective is ranked 66 in the law journals ranking by Scopus, and that is European Business Organization Law Review (as of 1 April 2025) with a Citescore of 4.6. When compared with other disciplines, a journal with such a low score in other areas would not make it to the top 1000 journals ranked in Scopus.

The main problem is the “snowball effect” (

Campbell et al. 2006). The great number of common law journals in WoS or Scopus makes it possible to count citations from common law countries, and furthermore, the publications in the same country in the same language are numerous and much more likely to be mutually cited and to drive the ranking up. It is simply much less likely that a U.S. author in a U.S. journal cites a paper written on civil law in the German language. Only if the number of civil law journals in WoS and Scopus increases will this become a more even playing field.

The question of language has to be mentioned again. If there are only two journals in the Czech language, most likely, one’s paper will be cited in the Scopus database foremost by papers published in the very same journals. This means that the two journals published in Czech are the only ones contributing to their journal rank in Scopus. All of the citations by research papers in journals not listed in Scopus or WoS or in books or book chapters would simply not contribute to the journal ranking and thereby also not contribute to the university ranking. While there are scientific search engines such as Google Scholar that are collecting citations also from sources outside of WoS and Scopus, they do not contribute to the journal ranking within Scopus and WoS. Such exclusion of citations from other sources is hard to justify, considering that citations serve the sole purpose of measuring impact. Both databases, as well as university rankings, completely exclude various other forms of publications from the measurement and thereby obviously do not catch the real “impact” of the publication itself, which is the one thing both promise to deliver. What if a legal publication has been taken as a basis to make a legislative or judicial change? This is one of the greatest impacts a legal publication can have, and it would not be caught by the database itself. Thereby, the databases seem to assume that the only relevant impact is a citation in a journal included in the database itself.

4.4. Conclusions Regarding the Evaluation of Civil Law Science

The need for measurements of the quality of research is understandable. It may matter for academic promotion, research grants, ranking of scientists, or university ranking. The decision makers need an effective and fast tool to determine who deserves financial support or how to assess academic excellence. It is also very understandable that not every university or even every government can make those decisions alone. While it is undeniable that only experts in the field and probably even only from that particular country could give a valid opinion on the quality of a certain publication, such a method is not sustainable. It is impossible to have a committee at a national level reading and examining all publications and attributing to them a certain quality measurement. However, a national ranking of journals that is established to measure quality has been done in several states, including Finland (

JUFO Publication Forum n.d.;

Honjik 2021), the UK (

Campbell et al. 2006), and Serbia (

Republic of Serbia n.d.). While the Finnish and UK models also encompassed foreign journals and thereby created something like their own assessment of worldwide journals, the Serbian model solely focused on ranking Serbian journals.

There are two main approaches to ranking law journals: the perception method and the citation metrics. The perception method usually relies on questionnaires. The THE university rankings use a survey to assess both teaching and research reputation in addition to the dominant method of citation metrics (

THE 2025b). The Finnish model relies on citation metrics for top-quality journals but uses perception methodology where citation metrics are not available; transparency of the peer review method; editors, authors, and readers come from various nationalities; etc. (

JUFO Publication Forum Classification Criteria n.d.).

The legal scientists from civil law states, whether in public or private law, have not offered so far any solution for the evaluation of the quality of research. A justification or excuse may be seen in various factors that will be summarized here:

Legal scholars publish in various forms, not just articles but also essays; case notes; and, most importantly, books and book chapters, all of which are (regularly) not included in WoS or Scopus.

The impact of legal research depends on the targeted audience—academics, judges, legislators, attorneys, or the general public. Is the impact greater if a law is changed based on a paper or if a paper is cited more times in WoS?

Legal scholarship regularly publishes locally relevant content, which is of great importance but will not attract international citation and thus would be considered weak in WoS or Scopus.

Legal scholarship in Europe relies on editorial review, rather than double-blind review (

Van Gestel and Lienhard 2019). European publishers do not believe that double-blind reviews bring better results as in smaller jurisdictions, reviewers may still recognize the author; it is time-consuming and bureaucratic; reviewers are not motivated to do a proper review, as there is no proper reward; reviewers suffer from all sorts of bias; and reviewer selection is not transparent (Van Gestel and Lienhard). For the same reason, some journals do not want to be measured by external databases such as Scopus or WOS, do not see any added value for the quality of the papers, and often do not submit their journal to them (

Honjik 2021).

WoS and Scopus lump together student-edited journals (foremost from the U.S.) with European journals edited by leading scholars and peer-reviewed journals (

Perez et al. 2019)—such a comparison is demotivating European journal editors to submit to WoS and Scopus.

Legal journals in some of the most influential civil law states are still editorially run, meaning that the editors in chief, together with their editorial board, decide whether a paper will be published without any external control over the paper. Insofar, they strongly believe that they are the guarantors of the quality, not some external indicators such as citation metrics. While I do not intend to confuse a double-blind review publication approach with the citation metrics, both of them have in common that they rely on outside factors to confirm the quality of the publications. The civil Europe editorial approach believes that the editors themselves, the readers, and building a long-term reputation of the journal are sufficient quality control. Such an approach does not offer any measurable outputs that a metrics-based university ranking could use.

5. Civil Law in the University Rankings—The Way Forward

The study reveals that currently, two of the most prominent university rankings, the Shanghai and THE rankings, in their evaluation of the law subject, do not accurately consider civil law research. Therefore, they cannot serve as an accurate basis for the measurement of research quality on civil law.

While Shanghai rankings based on WoS almost exclude civil law journals, the THE ranking based on Scopus and a different methodology is going in the right direction but still falls short. The easiest way forward would be to include more journals from civil law countries in WoS and Scopus. Inequalities in the impact between journals from jurisdictions of different sizes would remain a challenge, especially if the language of the journal is used only in one small jurisdiction.

In the meantime, the research methodology for university rankings that set the goal of being true world rankings needs to measure research impact with more differentiated methods than just citation metrics based on WoS and/or Scopus. It is primarily the task of university rankings and research databases to find adequate ways to measure and compare quality as they claim to do it accurately but fail (at least) when it comes to civil law. In the meantime, it is on governments, universities, and other stakeholders to acknowledge that the current research databases and university rankings may not serve as accurate indicators of the quality of research on civil law when it comes to decisions on promotion, awards, research funding, etc.

To improve the measurement of quality and impact of civil law science, the following steps are essential:

- -

Include journals published in the official languages of the respective country and ensure a fair comparison for journals published in languages spoken in small jurisdictions.

- -

Broaden the types of publications and include books, book chapters, and other forms of publications.

- -

Find ways to measure the impacts on legislation and the judiciary while considering that in some jurisdictions, the judiciary will not refer to academic publications in their judgments.

- -

Include citations of journal papers in other forms of publications, such as books and book chapters.

- -

Consider national/regional research awards that better reflect research quality in various languages.

- -

Conduct surveys to fill the gap in data where citation metrics are insufficient.

- -

Find ways to cooperate with the national rankings of journals.

- -

Until a more accurate and inclusive database for civil law research is established, academic promotion in civil law states should not depend (solely) on WoS or Scopus, nor research projects, awards, or scholarships.