Community Cornerstones: An Analysis of HBCU Law School Clinical Programs’ Impact on Surrounding Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

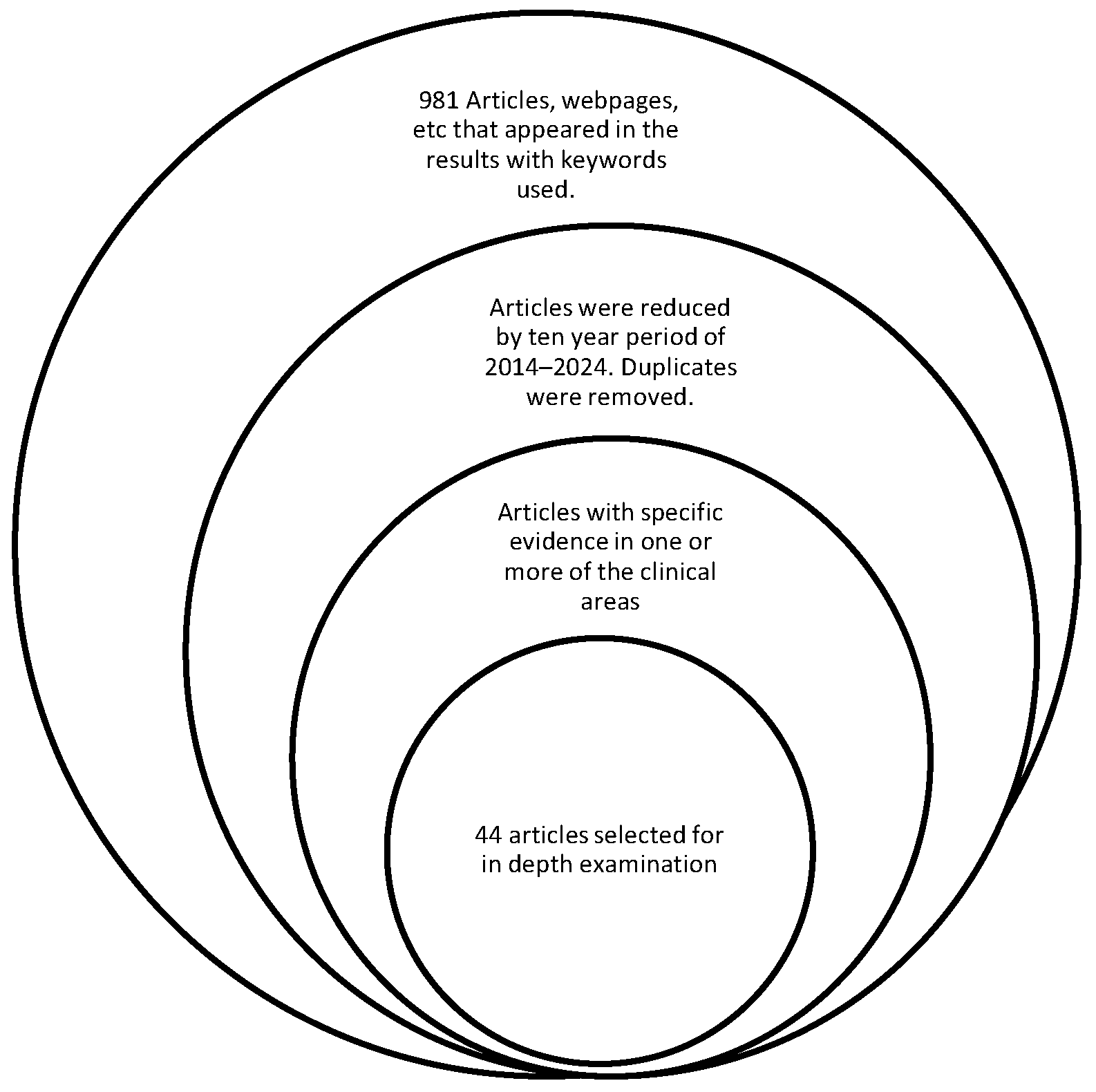

2. Materials and Methods

3. Analysis

3.1. Clinical Programs at HBCU Law Schools

3.2. Community Impact Measures

4. Discussion

Overall Analysis of the Six HBCUs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abernethy, Macy. 2023. Law School Pro Bono Service Award: NCCU School of Law Elder Law Project—North Carolina Bar Association. June 12. Available online: https://www.ncbar.org/member/focus/law-school-pro-bono-award-nccu-school-of-law-elder-law-project/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Alexander, Ames. 2023. Salisbury, Rowan Settle Suit with Elderly Woman Who Was Pulled by Hair at Police Stop. Charlotte Observer. September 28. Available online: https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/crime/article279863834.html (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- American Bar Association. 2024. ABA Profile of the Legal Profession. Available online: https://www.americanbar.org/news/reporter_resources/profile-of-profession/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Anderson, Monica, and Jenn Hatfield. 2024. A Look at Historically Black Colleges and Universities in the U.S. Pew Research Center (blog). October 2. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/10/02/a-look-at-historically-black-colleges-and-universities-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Bailer, Brittany. 2023. Howard University Law Students Campaign Against the Criminalization of Hip-Hop. The Dig at Howard University. December 11. Available online: https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/howard-university-law-students-campaign-against-criminalization-hip-hop (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Bloomgarden, Alan H. 2017. Out of the Armchair: About Community Impact. International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement 5: 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, Glenn A. 2009. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal 9: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, Joe. 2021. FAMU College of Law Will Begin Initiative to Support Minority-Owned Businesses with Grant from Wells Fargo. Central Florida Public Media. November 16. Available online: https://www.cfpublic.org/2021-11-16/famu-college-of-law-will-begin-initiative-to-support-minority-owned-businesses-with-grant-from-wells-fargo (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Cahn, Edgar S., and Jean C. Cahn. 1964. The War on Poverty: A Civilian Perspective. The Yale Law Journal 73: 1317–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Ailsa. 2021. Senators Discuss Their Proposal That Would Repair the Infrastructure of HBCUS and NPR, sec. National. October 5. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2021/10/05/1043458075/senators-discuss-their-proposal-that-would-repair-the-infrastructure-of-hbcus-an (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Charnosky, Christine. 2022. Florida A&M Law Launches Economic Justice Initiative to Support Minority-Owned Businesses. Daily Business Review. March 22. Available online: https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/2022/03/22/florida-am-law-launches-economic-justice-initiative-to-support-minority-owned-businesses/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Conville, Richard L., and Ann M. Kinnell. 2010. Relational Dimensions of Service-Learning: Common Ground for Faculty, Students, and Community Partners. Journal of Community Engagement & Scholarship 3: 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, Misha. 2019. Howard Law Students, Faculty Experts Respond to HUD’s Move to Restrict Fair Housing Regulations. The Dig at Howard University. October 28. Available online: https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/howard-law-students-faculty-experts-respond-huds-move-restrict-fair-housing-regulations (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Cornelius, Misha. 2020. Howard University’s Clinical Law Center Calls Out Racial Discrimination in Sewell v. State of Maryland. The Dig at Howard University. April 10. Available online: https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/howard-universitys-clinical-law-center-calls-out-racial-discrimination-sewell-v-state-maryland (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Crowell NNPA, Charlene. 2015. Supreme Court to Review Fair Housing Law: [3]. University Wire, sec. Politics. February 15. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1771568092/abstract/E3D1BDDF7A3A4CE9PQ/1 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Davis, Akilah. 2024. NC Central School of Law One of 6 at HBCUs in the Country; a Legacy That Started in 1939. ABC11 Raleigh-Durham. February 2. Available online: https://abc11.com/bhm-nccu-law-school-hbcu-experience-unc-no-black-students-allowed/14381466/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Dyson, Michael Eric. 2007. Debating Race: With Michael Eric Dyson, 1st ed. New York: Basic Civitas Books. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Adrian, and Ross Hyams. 2008. Independent evaluations of clinical legal education programs: Appropriate Objectives and Processes in an Australian Setting. Griffith Law Review 17: 52–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falati, Shahrokh. 2020. The Makings of a Culturally Savvy Lawyer: Novel Approaches For Teaching and Assessing Cross-Cultural Skills in Law School. Journal of Law and Education 49: 627–84. [Google Scholar]

- FAMU’s Legal Interns Get Their Day in Court. n.d. The Florida Bar (blog). Available online: https://www.floridabar.org/the-florida-bar-news/famus-legal-interns-get-their-day-in-court/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Florida A & M University. 2023. Law News Releases. October. Available online: https://law.famu.edu/newsroom/news-releases/new-citizens-welcomed-at-naturalization-ceremony-at-famu-law.php (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Florida A & M University. 2024a. About Us. Available online: https://law.famu.edu/about-us/index.php (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Florida A & M University. 2024b. Spotlight. Available online: https://law.famu.edu/spotlight.php (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Franklin, Robert, Sinead Younge, and Kipton Jensen. 2023. The Role of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in Cultivating the next Generation of Social Justice and Public Service-Oriented Moral Leaders during the Racial Reckoning and COVID-19 Pandemics. American Journal of Community Psychology 71: 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathright, Jenny. 2021. Advocates Say New D.C. Clemency Rules Give Too Much Power to the Feds. DCist (blog). September 11. Available online: https://dcist.com/story/21/09/11/dc-clemency-proposed-regulations-rules-statehood/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Gittell, Ross, and Margaret Wilder. 1999. Community Development Corporations: Critical Factors That Influ-ence Success. Journal of Urban Affairs 21: 341–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groark, Christina J., and Robert B. McCall. 2018. Lessons Learned from 30 Years of a University-Community Engagement Center. Journal of Higher Education Outreach & Engagement 22: 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, George S. 1973. Clinical Legal Education: History and Diagnosis. Journal of Legal Education 26: 162–93. [Google Scholar]

- Habitat for Humanity. 2024. ‘Reforming How We Look at Housing’ Habitat for Humanity. Available online: https://www.habitat.org/stories/reforming-how-we-look-housing (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Harris, Lindsay Muir. 2018. Clinical Law Prof Blog: UDC Law’s Immigration & Human Rights Clinic’s Pro Se Asylum Filing Workshop with Human Rights First. September 29. Available online: https://lawprofessors.typepad.com/clinic_prof/2018/09/udc-laws-immigration-human-rights-clinics-pro-se-asylum-filing-workshop-with-human-rights-first-.html (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Howard Newsroom Staff. 2016. President Barack Obama Grants Clemency to Howard University School of Law Client. The Dig at Howard University. June 20. Available online: https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/president-barack-obama-grants-clemency-howard-university-school-law-client (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Howard University. 2024. The Clinical Law Center Howard University School of Law. Available online: https://law.howard.edu/academics/clinical-law-center (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Howard University School of Law. 2023. Howard Law Movement Lawyering Clinic Work to Push PG County Courts to Continue Making Proceedings Virtually AccessibleThurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center. Available online: https://thurgoodmarshallcenter.howard.edu/howard-law-movement-lawyering-clinic-work-push-pg-county-courts-continue-making-proceedings (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Howard University School of Law. 2024a. Consumer Information (ABA Required Disclosures) Howard University School of Law. Available online: https://law.howard.edu/resources/consumer-information-aba-required-disclosures (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Howard University School of Law. 2024b. Faculty Developments & Recent Scholarship Howard University School of Law. Available online: https://law.howard.edu/faculty/faculty-developments-recent-scholarship (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Howard University School of Law. 2024c. Intellectual Property Patent Clinic Howard University School of Law. Available online: https://law.howard.edu/academics/clinical-law-center/intellectual-property-patent-clinic (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Howard University School of Law. 2024d. Our Mission Howard University School of Law. Available online: https://law.howard.edu/about/our-mission (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Hyams, Ross. 2006. Student Assessment in the Clinical Environment—What Can We Learn from the US Experience? International Journal of Clinical Legal Education 10: 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, Terry. 2024. NCCU School of Law Partners with HUD to Grow next Generation of Fair Housing Leaders and Increase Access to Fair Housing in North Carolina North Carolina Central University. October 23. Available online: https://www.nccu.edu/news/nccu-school-law-partners-hud-grow-next-generation-fair-housing-leaders-and-increase-access (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Igbokwe, Justice Chika, Rosita Ebere Daraojimba, Beatrice Adedayo Okun-ade, Ololade Elizabeth Adewusi, Bukola A. Odulaja, and Foluke Eyitayo Adediran. 2024. Community Engage-ment in Local Governance: A Review of USA and African Strategies. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 21: 105–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingman, Benjamin, Katie Lohmiller, Nick Cutforth, and Elaine Belansky. 2022. The Potential of Service Learning in Rural Schools: The Case of the Working Together Project. The Rural Educator 43: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Service for Human Rights. 2019. IACHR The US Must Keep Funding Human Rights Body. ISHR. March 1. Available online: https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/iachr-us-must-keep-funding-human-rights-body/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Israel, Nicole. 2014. Law School Nation. Student Lawyer 42: 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Joyce. 2010. FAMU Law Students Transform Theory Into Potential Legislation. Diverse: Issues In Higher Education. December 22. Available online: https://www.diverseeducation.com/demographics/african-american/article/15090139/famu-law-students-transform-theory-into-potential-legislation (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Keeler, Bonnie L., Kate D. Derickson, Hannah Jo King, Keira B. Leneman, Adam F. Moskowitz, Amaniel Mrutu, Bach Nguyen, and Rebecca H. Walker. 2022. Community-Engaged Scholarship for Graduate Students: Insights from the CREATE Scholars Program. Journal of Higher Education Outreach & Engagement 26: 125–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, Lindsey N., Danielle MacCartney, and Andrea Miller. 2014. Facilitating Student Engagement: Social Responsibility and Freshmen Learning Communities. Teaching & Learning Inquiry: The ISSOTL Journal 2: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujovich, Gil. 1993. Public Black Colleges: The Long History of Unequal Funding. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education 2: 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, DaQuan. 2023. Howard Law Students Present Research at United Nations Conference—The Hilltop. January 18. Available online: https://thehilltoponline.com/2023/01/18/howard-law-students-present-research-at-united-nations-conference/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Legal Service Corporation. 2023. Section 2: Today’s Low-Income America. In The Justice Gap Report (blog); December 2. Available online: https://justicegap.lsc.gov/resource/section-2-todays-low-income-america/ (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Legal Services Corporation. 2025. Executive Summary. In The Justice Gap Report (blog). Available online: https://justicegap.lsc.gov/resource/executive-summary/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Levkoe, Charles Z. 2020. Questioning the Impact of Impact: Evaluating Community-Campus Engagement as Contextual, Relational, and Process Based. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 26: 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomax, Dr Michael. 2024. Don’t Just Witness History; Seize the Opportunity to Shape It. UNCF (blog). November 4. Available online: https://uncf.org/the-latest/dont-just-witness-history-seize-the-opportunity-to-shape-it (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Miles College of Law. 2024. Our Story. Miles Law. Available online: https://mlaw.edu/our-story (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2024. The NCES Fast Facts Tool Provides Quick Answers to Many Education Questions (National Center for Education Statistics). National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=667 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- National Jurist. 2024. Washington Becomes Fourth State to Adopt Alternative Pathways to Practice Law—Nationaljurist. March 25. Available online: https://nationaljurist.com/national-jurist/news/washington-becomes-fourth-state-to-adopt-alternative-pathways-to-practice-law/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Nelms, Charlie. 2010. HBCU Reconstruction. Presidency 13: 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nhlapo, Molise David, and Dipane Joseph Hlalele. 2021. Successes and Failures of the University-Community Partnership: A Case Study of Imbali Semi-Rural Settlement. Education and Urban Society 55: 222–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North Carolina Central University. 2020. NCCU School of Law—NCCU LAW. July 1. Available online: https://law.nccu.edu/about/nccu-school-of-law/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- North Carolina Central University. 2020a. ABA Required Disclosures—NCCU LAW. July 9. Available online: https://law.nccu.edu/admissions/aba-required-disclosures/ (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- North Carolina Central University. 2020b. Juvenile Law Clinic—NCCU LAW. July 15. Available online: https://law.nccu.edu/clinics/juvenile-law-clinic/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- North Carolina Central University. 2022a. Juvenile Law Students Serve Local Community—NCCU LAW. December 2. Available online: https://law.nccu.edu/juvenile-law-students-serve-local-community/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- North Carolina Central University. 2022b. List of Issued Patents by IP Clinic—NCCU LAW. November 18. Available online: https://law.nccu.edu/clinics/intellectualpropertyclinic/list-of-issued-patents-by-ip-clinic/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- North Carolina Central University. 2022c. NCCU Wills Clinic/Elder Law Project—NCCU LAW. September 28. Available online: https://law.nccu.edu/events/nccu-wills-clinic-elder-law-project/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Opara, Anais. 2023a. Criminal Defense and Racial Justice Clinic Students Pursue Equity through Defense Representation and Reentry Advocacy—UDC David A. Clarke School of Law. November 2. Available online: https://law.udc.edu/2023/11/02/criminal-defense-and-racial-justice-clinic-students-make-strides-in-criminal-defense-and-reentry-advocacy/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Opara, Anais. 2023b. Tax Clinic Provides Valuable Assistance and Community Outreach at the Tax Court—UDC David A. Clarke School of Law. October 30. Available online: https://law.udc.edu/2023/10/30/tax-clinic-at-the-tax-court-providing-valuable-assistance-and-community-outreach/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Opara, Anais. 2023c. The Impactful Work of the Immigration and Human Rights Clinic Students—UDC David A. Clarke School of Law. October 30. Available online: https://law.udc.edu/2023/10/30/the-impactful-work-of-the-immigration-and-human-right-clinic-students/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Opara, Anais. 2023d. UDC Law Community Development Law Clinic Empowering Housing Cooperatives and Providing Entrepreneurial Support—UDC David A. Clarke School of Law. November 2. Available online: https://law.udc.edu/2023/11/02/udc-community-development-law-clinics-impactful-year-in-housing-cooperatives-and-entrepreneurial-support/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Opara, Anais. 2023e. Youth Justice Clinic Takes Holistic Approach to Reform—UDC David A. Clarke School of Law. October 30. Available online: https://law.udc.edu/2023/10/30/youth-justice-clinic-led-by-professor-saleema-snow-takes-holistic-approach-to-reforming-youth-justice/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Paschall-Brown, Gail. 2023. FAMU Setting up Legal Clinic to Support Small Businesses. WESH. January 14. Available online: https://www.wesh.com/article/famu-legal-clinic-businesses/42494914 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- PR Newswire. 2014. UH Law Center Poised to Help Unaccompanied Central American Immigrant Children: Immigration, Civil Law Clinics Assist Undocumented Minors With Complex Legal System. July 29. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1549349147/abstract/2778E1C60EBB4244PQ/1 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Robert, Amanda. 2023. Outside Perspectives. ABA Journal 109: 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Scholefield, Kylie, and Joseph Tulman. 2015. Reversing The School-To-Prison Pipeline: Initial Findings From The District of Columbia On The Efficacy of Training and Mobilizing Court-Appointed Lawyers to Use Special Education Advocacy on Behalf of At-Risk Youth. University of the District of Columbia Law Review 18: 215. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, John Y. 1963. The Politics of the Morrill Act. Agricultural History 37: 103–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, Karen, and Karen Sloan. 2023. Civil Legal Aid Attorneys in Short Supply, ABA Report Finds. Reuters, sec. Government. November 30. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/legal/government/civil-legal-aid-attorneys-short-supply-aba-report-finds-2023-11-30/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Southern University Law Center. 2020. Southern University Law Center, DCFS Enter Poverty Innovation Project—Southern University Law Center. February 21. Available online: https://www.sulc.edu/news/3254 (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Southern University Law Center. 2024a. Disaster Response—Southern University Law Center. Available online: https://www.sulc.edu/page/disaster-response (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Southern University Law Center. 2024b. Mission & Values—Southern University Law Center. Available online: https://www.sulc.edu/page/mission-values (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Southern University Law Center. 2024c. Southern University Law Center: Free Legal Clinic for Estate Planning & Disaster Preparedness. Targeted News Service. February 22. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2929526619/citation/16582A683C494681PQ/1 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Staff, WI Web. 2023. JPMorgan Chase Helps Fund Howard Law School Clinic at $500K. The Washington Informer. October 3. Available online: http://www.washingtoninformer.com/jpmorgan-chase-howard-university-heirs-property-clinic/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Stanford Law School. 2019. Marcy Karin, JD ’03, Receives Clinical Legal Education Association (CLEA) Award. Stanford Law School. November 4. Available online: https://law.stanford.edu/stanford-lawyer/articles/marcy-karin-jd-03-receives-clinical-legal-education-association-clea-award/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- St. John the Baptist Parish. 2021. Southern University Law Donates Printers to St. John FastTrac. February 24. Available online: https://www.sjbparish.gov/News-articles/Southern-University-Law-Center-donates-Printers-to-St.-John-Parish-FastTrac-Graduates (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Strong, Stephanie. 2019. FAMU Law Partners with Orange TV to Produce Legal Connections. OCFL Newsroom. September. Available online: https://newsroom.ocfl.net/media-advisories/press-releases/2019/09/famu-law-partners-with-orange-tv-to-produce-legal-connections/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Targeted News Service. 2020. University of District of Columbia Clarke School of Law Issues Public Comment on Executive Office for Immigration Review Proposed Rule. April 2. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2385424855/citation/4051898647BF411CPQ/1 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Texas Southern University. 2023. Texas Southern University The Earl Carl Institute for Legal and Social Policy Immigration Clinic at Texas Southern University Receives $1 Million Grant from Houston Endowment. October. Available online: https://www.tsu.edu/news/2023/#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Department%20of%20Energy's,Marshall%20School%20of%20Law's... (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Texas Southern University. 2024. Linking Generational Wealth-Wills & Estate Planning Clinic. Available online: https://www.tsulaw.edu/centers/ECI/Wheeler-church-Wills-Clinic-Webpage_registration%202024.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2020. NCCU and UNC-Chapel Hill Partner to Revive Veterans Clinic UNC-Chapel Hill. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. June 15. Available online: https://www.unc.edu/posts/2020/06/15/nccu-and-unc-chapel-hill-partner-to-revive-veterans-clinic/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Thurgood Marshall School of Law. 2024. About Thurgood Marshall School of Law in Houston, Texas. Available online: https://www.tsulaw.edu/welcome/about_tmsl.html#mission (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Travis, Bobbie. 2022. Splunk Legal Global Affairs Donates $10K to Technology & Entrepreneurship Clinic—Southern University Law Center. Splunk. May 24. Available online: https://www.splunk.com/en_us/blog/splunklife/splunk-legal-global-affairs-donates-10k-to-technology-and-entrepreneurship-clinic-southern-university-law-center.html (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- UNCF. 2024. HBCU Economic Impact Report—UNCF. Available online: https://uncf.org/programs/hbcu-impact (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- University of the District of Columbia. 2021. Dean’s Welcome. UDC David A. Clarke School of Law. March 4. Available online: https://law.udc.edu/welcome/ (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- University of the District of Columbia. 2023. Clinic Landing Page. UDC David A. Clarke School of Law. January 11. Available online: https://law.udc.edu/clinicintro/ (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2021. Assessing the Impact of Community-Level Initiatives: A Literature Review. Available online: https://acf.gov/opre/report/assessing-impact-community-level-initiatives-literature-review (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- WAFB Staff. 2016. SU Law Center Opens Free Disaster Recovery Clinic for Flood Victims. WAFB Staff. August 31. Available online: https://www.wafb.com/story/32932007/su-law-center-opens-free-disaster-recovery-clinic-for-flood-victims (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Whitty, RaNeeka. 2023. Justice Sotomayor Issues Dissent in Reaction to the Denial of a Cert Petition Filed by Howard Law Civil Rights Clinic. The Dig at Howard University. July 10. Available online: https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/justice-sotomayor-issues-dissent-reaction-denial-cert-petition-filed-howard-law-civil-rights-clinic (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Williams, Krystal L., Brian A. Burt, Kevin L. Clay, and Brian K. Bridges. 2019. Stories Untold: Counter-Narratives to Anti-Blackness and Deficit-Oriented Discourse Concerning HBCUs. American Educational Research Journal 56: 556–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRAL. 2015. Lawsuit Claiming Racial Profiling Filed against Durham Police. WRAL.Com. April 29. Available online: https://www.wral.com/story/lawsuit-claiming-racial-profiling-filed-against-durham-police/14613538/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

| 1 | FAMU Law produces Legal Connections TV programming to inform the community about legal services and issues (Strong 2019). |

| 2 | FAMU Law hosts pop-up legal service clinics (Florida A & M University 2023). |

| 3 | FAMU Law produces Legal Connections TV programming to inform community about legal services and issues (Strong 2019) |

| 4 | FAMU Racial Justice Fellows and legal clinic filed an amicus brief “in support of a constitutional challenge to Daytona Beach’s anti-panhandling ordinance.” The amicus brief “focused on providing additional context and insight into the relevant First Amendment jurisprudence that relates to the issue before the court” (Florida A & M University 2024b). |

| 5 | FAMU Economic Justice Clinic helps small business owners with free legal services (Paschall-Brown 2023). |

| 6 | FAMU Law partners with Wells Fargo to assist small business owners (Byrnes 2021; Charnosky 2022). |

| 7 | FAMU Law Clinic students draft legislation impacting children who are wards of the state (Jones 2010). |

| 8 | FAMU Law produces Legal Connections TV programming to inform community about legal services and issues (Strong 2019) |

| 9 | FAMU Law hosts pop up legal service clinic (Florida A & M University 2023) |

| 10 | FAMU Law produces Legal Connections TV programming to inform community about legal services and issues (Strong 2019) |

| 11 | FAMU Law Clinic hosts naturalization ceremony for 20 new citizens (Florida A & M University 2023). |

| 12 | FAMU Law hosts pop up legal service clinic (Florida A & M University 2023) |

| 13 | FAMU Law Criminal Defense Clinic students win case for client (FAMU’s Legal Interns Get Their Day in Court n.d.). |

| 14 | FAMU Law produces Legal Connections TV programming to inform community about legal services and issues (Strong 2019) |

| 15 | FAMU Law hosts pop up legal service clinic (Florida A & M University 2023) |

| 16 | The HUSL Fair Housing Clinic students, in collaboration with the D.C. Housing Authority, provided testimony for the D.C. Council Oversight Hearing (Howard University School of Law 2024b). |

| 17 | HUSL Law Clinic writes to HUD in response to a new rule “that would severely constrain a critical tool for confronting housing discrimination” (Cornelius 2019). |

| 18 | HUSL Law Clinic submits amicus brief in support of safeguarding the Fair Housing Act of 1968 (Crowell NNPA 2015). |

| 19 | Law Clinic Student discusses preventing eviction for her client (Habitat for Humanity 2024). |

| 20 | HUSL Intellectual Property Patent Clinics “prepare actual patent applications which will be filed for inventors under the supervision of a licensed patent attorney” (Howard University School of Law 2024c). |

| 21 | HUSL Clinic provides free legal estate planning services through student-led clinics via funded grant (Staff 2023). |

| 22 | HUSL Clinic presents to the UN on the inclusion of African Americans and other marginalized groups in the Sustainable Development Goals (Lawrence 2023). |

| 23 | HUSL Movement Lawyering Clinic surveys PG County Court system and advocates for fair treatment and bail (Howard University School of Law 2023). |

| 24 | HUSL signs petition in support of the International Service for Human Rights (International Service for Human Rights 2019). |

| 25 | HUSL Law Clinic Client was granted clemency by President Barack Obama (Howard Newsroom Staff 2016). |

| 26 | HUSL Criminal Justice Clinic: Four third-year law students at the clinic worked on People of the State of California v. Ronnie Louvier in San Francisco (Bailer 2023). |

| 27 | HUSL Human and Rights Clinic wrote an amicus brief in Sewell v. State of Maryland (Cornelius 2020). |

| 28 | HUSL Law clinic students wrote a petition that received support from Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor (Whitty 2023). |

| 29 | HUSL Law Clinic students campaign for local clemency (Gathright 2021). |

| 30 | HUSL Movement Lawyering Clinic advocated to require each court in the state to provide remote audio–visual access to all public proceedings (Robert 2023). |

| 31 | NCCU Housing Clinic launches partnership with HUD to promote community awareness and advocacy for fair housing (Hyman 2024). |

| 32 | NCCU Law Intellectual Property Clinic displays a list of patents it successfully filed for clients (North Carolina Central University 2022b). |

| 33 | NCCU Law Elder Law Project represents clients over 60 (Abernethy 2023). |

| 34 | NCCU Law Clinic partners with UNC Chapel to represent veterans (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2020). |

| 35 | NCCU Wills Clinic participates in Lawyer on the Line in collaboration with Duke Law’s Pro Bono program and Legal Aid in North Carolina (North Carolina Central University 2022c). |

| 36 | NCCU Law represented 23 clients for first appearances in Juvenile Court (North Carolina Central University 2020b). |

| 37 | NCCU Law Clinic students provided a holiday meal for youth housed in the detention center (North Carolina Central University 2022a). |

| 38 | NCCU Law Civil Litigation Clinic wins settlement for client (Alexander 2023). |

| 39 | NCCU Law Civil Litigation Clinic files suit against Durham Police on behalf of a client who claims that his vehicle was illegally searched (WRAL 2015). |

| 40 | SULC Disaster Recovery Clinic represents clients with housing insecurity after flood (WAFB Staff 2016). |

| 41 | Student attorneys assist clinic clients with legal matters associated with obtaining relief measures/recovery assistance resulting from natural disasters (Southern University Law Center 2024a). |

| 42 | SULC Entrepreneurship Clinic donates printers to graduates of entrepreneurship program (St. John the Baptist Parish 2021). |

| 43 | Southern University Law Center hosts wills and estate clinic (Southern University Law Center 2024c). |

| 44 | SULC Technology and Entrepreneurship Clinic given donation in support of their work, including forming 33 new businesses and serving 140 clients (Travis 2022). |

| 45 | SULC partners with the DCFS to provide legal services like expungement, tax credit assistance, etc. (Southern University Law Center 2020). |

| 46 | TSU Wills Probate and Guardianship Clinic takes on 40-70 cases per semester based on 8–10 students per semester taking on 5–7 cases each semester (Texas Southern University 2024). |

| 47 | TSU Wills, Probate, and Guardianship Clinic takes on 40-70 cases per semester based on 8–10 students per semester taking on 5–7 cases each semester (Texas Southern University 2024). |

| 48 | TSU Law Clinic partners with other Houston Law schools and organizations to provide continuing education to help lawyers represent undocumented minors (PR Newswire 2014). |

| 49 | TSU Law receives grant to represent clients in the naturalization process (Texas Southern University 2023). |

| 50 | UDC Law Community Development Clinic represents housing co-ops (Opara 2023d). |

| 51 | UDC Law Tax Clinic represents clients during calendar call (Opara 2023b). |

| 52 | UDC Law Legislation Clinic provides menstrual supplies for women in shelters and schools (Stanford Law School 2019). |

| 53 | UDC Law Special Education Clinic conducts intervention for youth at risk (Scholefield and Tulman 2015). |

| 54 | UDC Law Clinic students advocate for youth that have long-term suspensions (Israel 2014). |

| 55 | UDC Law Youth Justice Clinic teaches paralegal course at youth detention center (Opara 2023e). |

| 56 | UDC Law Youth Justice Clinic represents clients to process name and gender changes (Opara 2023e). |

| 57 | UDC Law Immigration and Human Rights Clinic issues comment on the Executive Office for Immigration Review‘s proposed rule entitled “Fee Review” (Targeted News Service 2020). |

| 58 | UDC Law Immigration and Human Rights Clinic successfully secured asylum “for a young man from the Caribbean based on his LGBTQ+ identity”, obtained a work permit for an East African D.C. resident facing homelessness, and successfully dismissed removal proceedings for three clients (Opara 2023c). |

| 59 | UDC Law Immigration and Human Rights Clinic represents asylum seekers (Harris 2018). |

| 60 | UDC Law Criminal Defense and Racial Justice Clinic hosts expungement clinic for DC residents (Opara 2023a). |

| Legal Clinic | FAMU | HUSL | NCCU | SULC | TSU | UDC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Law | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Estates Wills and Trusts | X | X | X | |||

| Tax | X | X | X | X | ||

| Housing | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Immigration | X | X | ||||

| Civil Rights | X | X | ||||

| Community | X | X | X | |||

| Youth Justice | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Intellectual Property | X | X | X | |||

| Criminal Defense | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Economic Justice | X | X | X | |||

| Worker’s Compensation | X | X | ||||

| Mediation Clinic | X | |||||

| Movement Lawyering | X |

| Affordable Housing and Displacement | Does the HBCU law school help to reduce the displacement/eviction of marginalized communities? Does the HBCU law school promote affordable housing, property improvements/repairs for marginalized communities? |

|

| Poverty and Economic Inequities | Does the HBCU law school provide entrepreneurship support, training, or aid in the prevention of loss of generational wealth (i.e., wills and estates)? |

|

| Youth Justice Involvement | Does the HBCU law school advocate for youth under 18 years of age or work on initiatives that aim to reduce youth involvement in the justice system and advocate for alternatives to incarceration? |

|

| Immigration Advocacy | Does the HBCU law school help asylum seekers and/or undocumented immigrants navigate the path to naturalization? |

|

| Crime and Public Safety | Does the HBCU law school help to promote awareness and equitable safety measures and help to reduce disparities in the justice system? |

|

| HBCU Law School | Affordable Housing and Displacement Prevention | Poverty and Economic Inequities | Youth Justice Involvement | Immigration Advocacy | Crime and Public Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAMU Law | Housing Clinic | Tax Clinic Economic Justice Mediation Clinic | Youth Justice Clinic | Criminal Defense Clinic | |

| HUSL | Housing Clinic | Estates, Wills, and Trusts Civil Rights Intellectual Property Economic Justice | Youth Justice Clinic Family Law | Movement Lawyering Civil Rights Criminal Defense Clinic | |

| NCCU Law | Housing Clinic | Tax Clinic Community Development Clinic Intellectual Property | Family Law Youth Justice | Criminal Defense Clinic | |

| SULC | Housing Clinic | Tax Clinic Community Development Clinic Intellectual Property Workers’ Compensation Clinic | Family Law Youth Justice Clinic | Criminal Defense Clinic | |

| TSU Law | Youth Justice Clinic | Family Law | Immigration Clinic | Criminal Defense Clinic | |

| UDC Law | Housing Clinic | Tax Clinic Community Development Clinic Workers’ Compensation Clinic | Family Law Youth Justice Clinic | Immigration Clinic | Civil Rights Criminal Defense Clinic |

| HBCU Law School | Affordable Housing and Displacement Prevention | Poverty and Economic Inequities | Youth Justice Involvement | Immigration Advocacy | Crime and Public Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAMU Law | Engagement1 Representation2 | Engagement3 Advocacy4 Representation5,6 | Advocacy7 Engagement8 Representation9 | Engagement10 Client Outcomes11 Representation12 | Client Outcomes13 Engagement14 Representation15 |

| HUSL | Advocacy16,17,18 Client Outcomes19 | Client Outcomes20 Representation21 Advocacy22,23 | Advocacy24 | Client Outcomes25 Representation26 Advocacy27,28,29,30 | |

| NCCU Law | Engagement31 | Client Outcomes32 Representation33,34,35 | Representation36 Engagement37 | Client Outcomes38 Representation39 | |

| SULC | Representation40 Client Outcomes41 | Engagement42,43 Client Outcomes44 Representation45 | Representation46 | ||

| TSU Law | Representation47 | Advocacy48 Representation49 | |||

| UDC Law | Representation50 | Representation51 Engagement52 | Advocacy53,54 Engagement 55 Representation56 | Advocacy57 Representation/Client Outcomes58,59 | Representation60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akintobi, A.; O’Hara, S.; Harrison, E.; Brittain, J. Community Cornerstones: An Analysis of HBCU Law School Clinical Programs’ Impact on Surrounding Communities. Laws 2025, 14, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14040048

Akintobi A, O’Hara S, Harrison E, Brittain J. Community Cornerstones: An Analysis of HBCU Law School Clinical Programs’ Impact on Surrounding Communities. Laws. 2025; 14(4):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14040048

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkintobi, Adeshola, Sabine O’Hara, Elgloria Harrison, and John Brittain. 2025. "Community Cornerstones: An Analysis of HBCU Law School Clinical Programs’ Impact on Surrounding Communities" Laws 14, no. 4: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14040048

APA StyleAkintobi, A., O’Hara, S., Harrison, E., & Brittain, J. (2025). Community Cornerstones: An Analysis of HBCU Law School Clinical Programs’ Impact on Surrounding Communities. Laws, 14(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14040048