Human Rights at the Climate Crossroads: Analysis of the Interconnection between Human Rights, Right to Climate, and Intensification of Extreme Climate Events

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Theoretical Background and Key Concepts

3.1. Human Rights

3.2. Right to Climate

3.3. Right to Climate Protection and the Human Right to Climate Adaptation

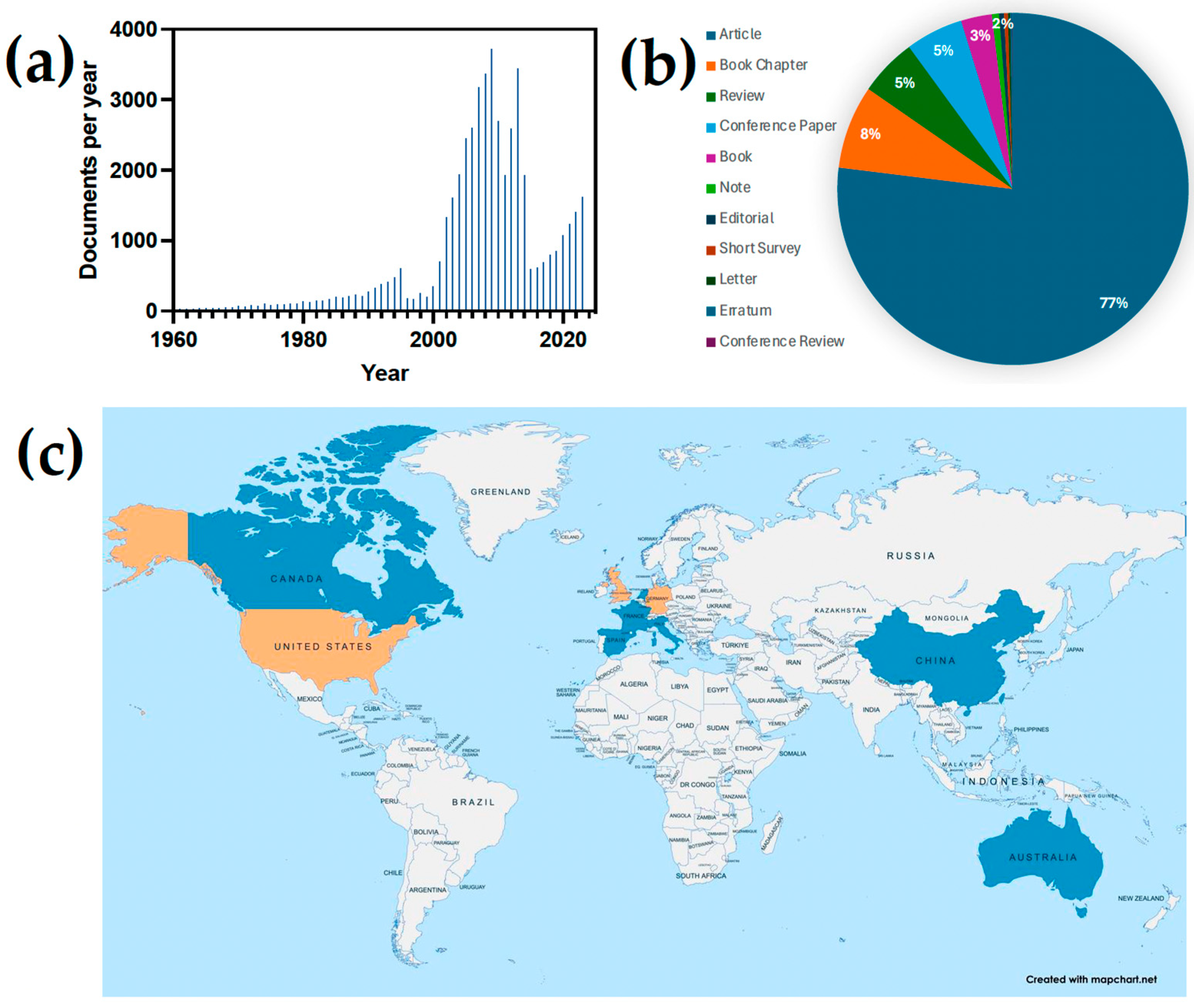

4. Bibliometric Analysis

5. Intensification of Extreme Events as a Catalyst for the Recognizing of the Right to Climate as a Human Right

5.1. Interconnection between Human Rights, Right to Climate and the Intensification of Extreme Weather Events

- The right to life, due to the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, such as storms, floods, and heatwaves, which put the lives of millions of people at risk. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress (Luporini and Kodiveri 2021; Luporini and Savaresi 2023; World Health Organization 2023; Solntsev 2024);

- The right to health is also severely affected. Extreme weather events impact people’s physical and mental health. Heatwaves can cause heat-related illnesses and deaths, while floods can spread waterborne diseases (Wewerinke-Singh and Doebbler 2022; World Health Organization 2023);

- The right to food is at risk because climate change affects agricultural production, which can lead to food insecurity. Droughts and floods can destroy crops, reduce food availability, and increase prices, especially affecting poorer communities (Rueda Abad and Vargas Castilleja 2021);

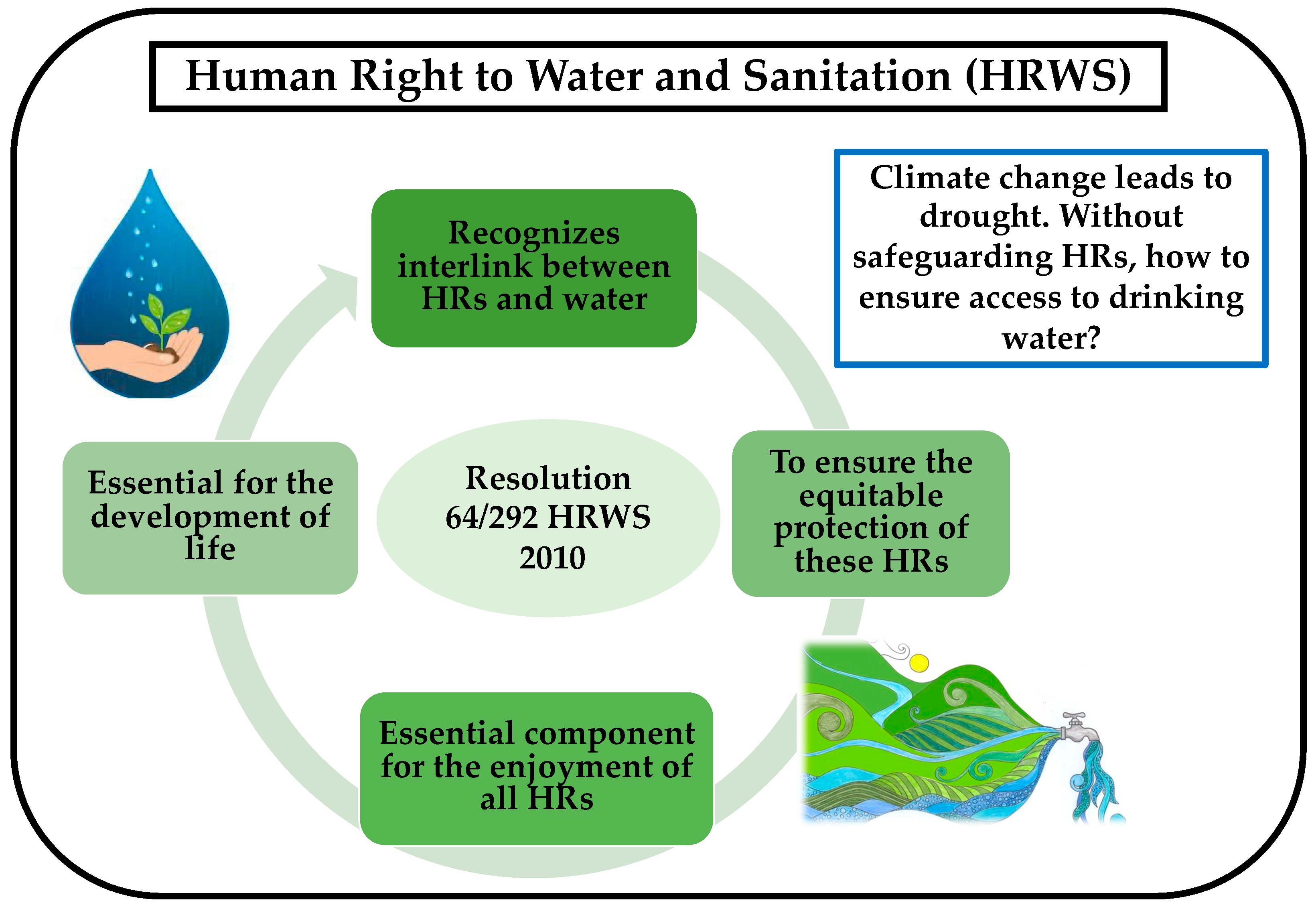

- The rights to water and sanitation is another human right that is compromised as the availability of drinking water is affected by climate change. Prolonged droughts and water contamination due to floods affect access to clean and safe water (Aller and Luis Romero 2015). The importance of clean water in sustaining human life and promoting health is also crucial. Indeed, water contamination remains a pressing issue worldwide. Anthropogenic activities, including urbanization, industrial processes, and agricultural practices, significantly contribute to water pollution (Babuji et al. 2023; Adeosun et al. 2016; Negrete-Bolagay et al. 2021; Zamora-Ledezma et al. 2021);

- The right to housing is in danger, as natural disasters destroy homes and displace entire communities. Rising sea levels threaten to flood coastal areas, forcing people to abandon their homes (Cooper et al. 2018).

Case Study: Cumbre Vieja Volcano

6. Recognition of the Right to Climate as a Human Right: An Imperative for Climate Justice

Enactment of the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation (HRWS) as a Case Study

7. Analyses, Discussion, and Preliminary Insights

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adeosun, F. I., T. F. Adams, and M. O. Amrevuawho. 2016. Effect of anthropogenic activities on the water quality parameters of federal university of agriculture Abeokuta reservoir. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 4: 104–8. [Google Scholar]

- Aller, Celia Fernández, and Elena De Luis Romero. 2015. The human right to water and sanitation. Ambienta 113: 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea Lozano Barragán et al. v the Presidency of the Republic et al. STC4360-2018. 2018. April 5. Available online: https://n9.cl/ojpkv (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Anisah, Siti, and Sahid Hadi. 2023. The Human Right to a Fair Trial in Competition Law Enforcement Procedures: A Rising Issue in Indonesian Experiences. Laws 12: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquae Fundación. 2024. How Climate Change Affects the Water Cycle. March 28. Available online: https://www.fundacionaquae.org/cambio-climatico-agua/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Arnaud, Gael, Yann Krien, Stéphane Abadie, Narcisse Zahibo, and Bernard Dudon. 2021. How Would the Potential Collapse of the Cumbre Vieja Volcano in La Palma Canary Islands Impact the Guadeloupe Islands? Insights into the Conse-quences of Climate Change. Geosciences 11: 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arturo, Larena. 2023. The Right to a Stable Climate. By (*) Carlos García Soto. December 1. Available online: https://efeverde.com/el-derecho-a-un-clima-estable-por-carlos-garcia-soto/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Asunción, Fernando. 2023. Almost 1300 Affected by the Eruption of La Palma Will Have to Return the Government Aid. November 21. Available online: https://www.vozpopuli.com/espana/casi-1300-afectados-erupcion-palma-devolver-ayudas-gobierno.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Babuji, Preethi, Subramani Thirumalaisamy, Karunanidhi Duraisamy, and Gopinathan Periyasamy. 2023. Human Health Risks due to Exposure to Water Pollution: A Review. Water 15: 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra Ramírez, José de Jesús, and Irma Salas Benítez. 2016. The human right to access to drinking water: Philosophical and constitutional aspects of its configuration and guarantee in Latin America. Prolegómenos 19: 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodansky, Daniel. 2016. The Paris Climate Change Agreement: A New Hope? American Journal of International Law 110: 288–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordner, Autumn, Jon Barnett, and Elissa Waters. 2023. The human right to climate adaptation. NPJ Climate Action 2: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, Claire, and Karin Buhmann. 2021. Risk-Based Due Diligence, Climate Change, Human Rights and the Just Transition. Sustainability 13: 10454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronte-Moreno, Olaia, Francisco-Javier González-Barcala, Xavier Muñoz-Gall, Ana Pueyo-Bastida, Jacinto Ramos-González, and Isabel Urrutia-Landa. 2023. Impact of Air Pollution on Asthma: A Scoping Review. Open Respiratory Archives 5: 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busayo, Emmanuel Tolulope, Ahmed Mukalazi Kalumba, Gbenga Abayomi Afuye, Olapeju Yewande Ekundayo, and Israel Ropo Orimoloye. 2020. Assessment of the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction studies since 2015. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 50: 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibieger Byskov, Morten. 2024. The Right to Climate Adaptation. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle Aguirre, María Clara. 2021. The environmental effects left by the Cumbre Vieja volcano on the island of La Palma. France 24, October 11. Available online: https://www.france24.com/es/programas/medio-ambiente/20211010-medio-ambiente-efectos-volcan-cumbre-vieja-palma (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Carracedo, Juan Carlos, Simon Day, Hervé Guillou, and Philip Gravestock. 1999a. Later stages of volcanic evolution of La Palma, Canary Islands: Rift evolution, giant landslides, and the genesis of the Caldera de Taburiente. Geological Society of America Bulletin 111: 755–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracedo, Juan Carlos, Simon Day, Hervé Guillou, and Francisco Pérez Torrado. 1999b. Giant Quaternary landslides in the evolution of La Palma and El Hierro, Canary Islands. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 94: 169–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands, Climate Change Litigation; Case 19/00135. 2019. Available online: https://n9.cl/kyr2g (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Cooper, Claire, Graeme Swindles, Ivan Savov, Anja Schmidt, and Karen Bacon. 2018. Evaluating the relationship between climate change and volcanism. Earth-Science Reviews 177: 238–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Evan, and Slobodan Simonovic. 2005. Climate Change and the Hydrological Cycle. Presented at the 17th Canadian Hydrotechnical Conference, Edmonton, AB, Canada, August 17–19; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- DW News. 2021. La Palma Volcano emitted as much SO2 as the entire EU in 2019. November 18. Available online: https://www.dw.com/es/volc%C3%A1n-de-la-palma-emiti%C3%B3-tanto-so2-como-toda-la-ue-en-2019/a-59853485 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Ekardt, Felix, and Marie Bärenwaldt. 2023. The German Climate Verdict, Human Rights, Paris Target, and EU Climate Law. Sustainability 15: 12993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Debate. 2023. Two Years of Catastrophes on La Palma: From the Volcano to the Fires without the Aid Promised by the Government. July 19. Available online: https://www.eldebate.com/sociedad/20230719/dos-anos-catastrofes-palma-volcan-incendios-ayudas-prometidas-gobierno_129034.html (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Fioletov, Vitali, Chris McLinden, Debora Griffin, Iha Abboud, Nickolay Krotkov, Peter Leonard, Can Li, Joanna Joiner, Nicolas Theys, and Simon Carn. 2023. Version 2 of the global catalogue of large anthropogenic and volcanic SO2 sources and emissions derived from satellite measurements. Earth System Science Data 15: 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargani, Julien. 2023. Relative sea level and coastal vertical movements in relation with volcano-tectonic processes in Mayotte. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparri, Giulia, Yassen Tcholakov, Sophie Gepp, Asia Guerreschi, Damilola Ayowole, Élitz-Doris Okwudili, Euphemia Uwandu, Rodrigo Sanchez Iturregui, Saad Amer, Simon Beaudoin, and et al. 2022. Integrating Youth Perspectives: Adopting a Human Rights and Public Health Approach to Climate Action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of the Canary Islands. 2021. The Treasury Sends the State an Evaluation of Damages from the Eruption for 842.33 Million Euros. December 4. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/noticias/hacienda-remite-al-estado-una-evaluacion-de-danos-de-la-erupcion-por-84233-millones-de-euros/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Government of the Canary Islands. 2022. Ángel Víctor Torres thanks the entire country for the expressions of solidarity and support for the reconstruction of La Palma. January 24. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/noticias/tag/fiesta-nacional/feed/?format=pdf (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Ingeoexpert. 2018. The Most Recent Volcanic Eruptions and Their Types. May 8. Available online: https://ingeoexpert.com/2018/05/08/erupciones-volcanicas/ (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- National Geographic Institute. 2022. Volcanology. January 19. Available online: http://www.ign.es/resources/docs/IGNCnig/VLC-Teoria-Volcanologia.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Jicha, Brian, Michael Garcia, and Charline Lormand. 2023. A Possible sea-level fall trigger for the youngest rejuvenated volcanism in Hawái. GSA Bulletin 135: 2478–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, Verena. 2022. A human right to climate protection—Necessary protection or human rights proliferation? Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 40: 158–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalis, Michael, and Anna-Lena Priebe. 2024. The right to climate protection and the essentially comparable protection of fundamental rights: Applying Solange in European climate change litigation? Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 33: 265–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey Cascada Rose Juliana et al. v United States of America. 6:15-cv-01517-TC, 18-36082. 2016. November 10. Available online: https://climatecasechart.com/case/juliana-v-united-states/ (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Limon, Marc. 2010. Human Rights Obligations and Accountability in the Face of Climate Change. Georgia Journal of International & Comparative Law 38: 544–92. [Google Scholar]

- Łuków, Paweł. 2018. A Difficult Legacy: Human Dignity as the Founding Value of Human Rights. Human Rights Review 19: 313–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luporini, Riccardo, and Arphita Upendra Kodiveri. 2021. The Increasing Role of Human Rights Bodies in Climate Litigation. London: The British Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Luporini, Ricardo, and Annalisa Savaresi. 2023. International Human Rights Bodies and Climate Litigation: Don’t Look Up? Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 32: 267–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maly, Elizabeth, and Anawat Suppasri. 2020. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction at Five: Lessons from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 11: 167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavhura, Emmanuel, and Komal Raj Aryal. 2023. Disaster mortalities and the Sendai Framework Target A: Insights from Zimbabwe. World Development 165: 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melley, Brian. 2024. U.K. Judge Acquits Climate Activist Greta Thunberg Over Oil Industry Conference Protest. Time, February 2. Available online: https://time.com/6632293/greta-thunberg-court-case-dismissed-uk-oil-protest/ (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Méndez Rocasolano, María. 2019. Law, climate manipulation through geoengineering techniques and objective 13 of sustainable development, action for the climate. the voice that calls in the desert. Revista Opinião Jurídica 17: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milford, Celia, Carlos Torres, Jon Vilches, Ann-Kathrin Gossman, Frederik Weis, David Suárez-Molina, Omaira E. García, Natalia Prats, África Barreto, Rosa García, and et al. 2023. Impact of the 2021 La Palma volcanic eruption on air quality: Insights from a multidisciplinary approach. Science of The Total Environment 869: 161652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Vargas, Ricardo, and Alfonso Liao Lee. 1999. Volcanic threats in Costa Rica: A prevention strategy. Revista Costarricense de Salud Pública 8: 15. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Dietmar, Maria Sdrolias, Carmen Gaina, Bernhard Steinberger, and Christian Heine. 2008. Long-Term Sea-Level Fluctuations Driven by Ocean Basin Dynamics. Science 319: 5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, Lawan Rukayya, Da’u Abdulrazak, Haruna Sani Uumar, and Alkali Saifullahi Auwalu. 2023. Effects of Air Pollution on Human Health: A Review. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science 5: 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrete-Bolagay, Daniela, Camilo Zamora-Ledezma, Cristina Chuya-Sumba, Frederico B. De Sousa, Daniel Whitehead, Frank Alexis, and Victor H. Guerrero. 2021. Persistent organic pollutants: The trade-off between potential risks and sustainable remediation methods. Journal of Environmental Management 300: 113737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, Lauren. 2022. Obligaciones de adaptación y movilidad adaptativa. Migraciones Forzadas Revista 69: 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Novel, Anne-Sophie. 2023. The Climate, a New Subject of Law. UNESCO. April 21. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/es/articles/el-clima-nuevo-sujeto-de-derecho-0 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Paez, Paula Andrea, Marisa Cogliati, Alberto Tomâs Caselli, and Ana Maria Monasterio. 2021. An analysis of volcanic SO2 and ash emissions from Copahue volcano. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 110: 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Sonny, Bernard McCaul, Gabriela Cáceres, Laura Peters, Ronak Patel, and Aaron Clark-Ginsberg. 2021. Delivering the promise of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction in fragile and conflict-affected contexts (FCAC): A case study of the NGO GOAL’s response to the Syria conflict. Progress in Disaster Science 10: 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, José Luis Rey. 2007. The nature of social rights. Derechos y Libertades 16: 137–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda Abad, Jose Clemente, and Rocío del Carmen Vargas Castilleja. 2021. Los derechos humanos ante la emergencia climática. Revista Internacional de Cooperación y Desarrollo 8: 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satow, Chris, Agust Gudmundsson, Ralf Gertisser, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Mohsen Bazargan, David M. Pyle, Sabine Wulf, Andrew J. Miles, and Mark Hardiman. 2021. Eruptive activity of the Santorini Volcano controlled by sea-level rise and fall. Nature Geoscience 14: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaresi, Annalisa. 2020. Human rights and the impacts of climate change: Revisiting the assumptions. Oñati Socio-Legal Series 11: 231–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solntsev, Alexander. 2024. The Growing Importance of Human Rights Treaty Bodies in Environmental Dispute Resolution. In International Courts versus Non-Compliance Mechanisms: Comparative Advantages in Strengthening Treaty Implementation. Edited by Christina Voigt and Caroline Foster. Studies on International Courts and Tribunals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 361–82. [Google Scholar]

- Special Plan for Civil Protection and Emergency Response due to Volcanic Risk in the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands (PEVOLCA). 2021. Report of the PEVOLCA Scientific Committee. Update on Volcanic Activity in Cumbre Vieja (La Palma). Available online: https://info.igme.es/eventos/la-palma/pevolca/211225_Informe-Comite-Cientifico-PEVOLCA.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Sternai, Pietro, Luca Caricchi, Daniel Garcia-Castellanos, Laurent Jolivet, Tom E. Sheldrake, and Sébastien Castelltort. 2017. Magmatic pulse driven by sea-level changes associated with the Messinian salinity crisis. Nature Geoscience 10: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindles, Graeme, Elizabeth Watson, Ivan Savov, Ian Lawson, Anja Schmid, Andrew Hooper, Claire Cooper, Charles Connor, Manuel Gloor, and Jonathan Carrivick. 2018. Climatic control on Icelandic volcanic activity during the mid-Holocene. Geology 46: 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Planetary Health. 2024. A human right to climate protection. The Lancet Planetary Health 8: e284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. 1948. Resolution 217 (111). International Bill of Human Rights. A Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Adopted by the General Assembly. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/670964 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- United Nations. 1976. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI). Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/es/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- United Nations. 1993. Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/vienna-declaration-and-programme-action (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- United Nations. 2010. Resolution 64/292. The Human Right to Water and Sanitation. Adopted by the General Assembly. (A/RES/64/292). Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/687002#record-files-collapse-header (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- United Nations. 2015. Resolution 29/15. Human Rights and Climate Change. Adopted by the General Assembly. (A/HRC/RES/29/15). Available online: https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2FHRC%2FRES%2F29%2F15&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- United Nations. 2016a. Resolution 32/33. Human Rights and Climate Change. Adopted by the General Assembly. (A/HRC/RES/32/33). Available online: https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2FHRC%2FRES%2F32%2F33&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- United Nations. 2016b. UNEP Implementing Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration. UN Environment Programme. August 19. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/unep-implementing-principle-10-rio-declaration (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- United Nations. 2017. Messengers of Peace. Malala Yousafzai. Available online: https://www.un.org/es/mensajeros-de-la-paz/malala-yousafzai (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- United Nations. 2020. Resolution 44/7. Human Rights and Climate Change. Adopted by the General Assembly. (A/HRC/RES/44/7). Available online: https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2FHRC%2FRES%2F44%2F7&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- United Nations. 2022a. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in the Context of Climate Change—Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in the Context of Climate Change Mitigation, Loss and Damage and Participation (A/77/226). Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/es/documents/thematic-reports/a77226-promotion-and-protection-human-rights-context-climate-change (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- United Nations. 2022b. Round Table on the Adverse Effects of Climate Change on the Full and Effective Enjoyment of Human Rights by People in Vulnerable Situations—Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (A/HRC/52/48). Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/es/documents/thematic-reports/ahrc5248-panel-discussion-adverse-impact-climate-change-full-and (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- United Nations. 2022c. The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment: A Catalyst for Accelerated Action to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (A/77/284). Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/thematic-reports/a77284-human-right-clean-healthy-and-sustainable-environment-catalyst (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- United Nations. 2022d. The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment—Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly (A/RES/76/300). Available online: https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2F76%2FL.75&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). 2023. First Meeting of the Committee to Support Implementation and Compliance of the Escazú Agreement Will Take Place at ECLAC. United Nations. August 4. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/en/news/first-meeting-committee-support-implementation-and-compliance-escazu-agreement-will-take-place (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Valdés De Hoyos, Elena Isabel Patricia, and Enrique Uribe Arzate. 2016. The Human Right to Water. A Question of Interpretation or Recognition. Cuestiones Constitucionales 34: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Volcano Active Foundation. 2022. How does a volcanic eruption affect the environment and health? February 14. Available online: https://volcanofoundation.org/es/como-le-afecta-una-erupcion-volcanica/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Wahi, Namita. 2022. The Evolution of the Right to Water in India. Water 14: 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wewerinke-Singh, M., and C. Doebbler. 2022. Protecting Human Health from Climate Change: Legal Obliga-tions and Avenues of Redress under International Law. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2023. Climate Change. October 12. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Young, Jessica. 2018. Escazú, the most important environmental agreement in history. United Nations Development Program, Panama. September 27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/es/panama/blog/escazu-el-acuerdo-ambiental-mas-importante-de-la-historia (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Zamora-Ledezma, Camilo, Daniela Negrete-Bolagay, Freddy Figueroa, Ezequiel Zamora-Ledezma, Ming Ni, Frank Alexis, and Victor H. Guerrero. 2021. Heavy metal water pollution: A fresh look about hazards, novel and conventional remediation methods. Environmental Technology & Innovation 22: 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acronym | Keywords | Number of Documents per Year (NDPY) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HR | Human rights | 2,165,039 |

| 2 | RC | Right and climate | 50,149 |

| 3 | HR & RC | Human rights and right and climate | 10,136 |

| HR | RC | HR & RC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National Institutes of Health | National Science Foundation | National Science Foundation |

| 2 | National Cancer Institute | European Commission | European Commission |

| 3 | National Natural Science Foundation of China | Natural Environment Research Council | National Natural Science Foundation of China |

| 4 | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute | National Natural Science Foundation of China | National Institutes of Health |

| 5 | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft | Natural Environment Research Council |

| 6 | National Institute of Mental Health | Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada | Australian Research Council |

| 7 | National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases | National Aeronautics and Space Administration | Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft |

| 8 | Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft | Seventh Framework Programme | Seventh Framework Programme |

| 9 | Medical Research Council | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | Economic and Social Research Council |

| 10 | Japan Society for the Promotion of Science | U.S. Department of Energy | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| Volcanic Eruption | Country | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Anak Krakatoa | Indonesia | 2018 |

| Kilauea | Hawaii Island | 2018 |

| Volcán de Fuego | Guatemala | 2018 |

| Whakaari | New Zealand | 2019 |

| Stromboli | Italy | 2019 |

| Sinabung | Indonesia | 2019 |

| Taal | Philippines | 2020 |

| Cumbre Vieja | Spain | 2021 |

| Nyiragongo | Democratic Republic of Congo | 2021 |

| La Soufriere | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 2021 |

| Fagradalsfjall | Iceland | 2021 |

| Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai | Tonga | 2022 |

| Fagradalsfjall | Iceland | 2023 |

| Sundhnúkur | Iceland | 2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz-Cruces, E.; Méndez Rocasolano, M.; Zamora-Ledezma, C. Human Rights at the Climate Crossroads: Analysis of the Interconnection between Human Rights, Right to Climate, and Intensification of Extreme Climate Events. Laws 2024, 13, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws13050063

Díaz-Cruces E, Méndez Rocasolano M, Zamora-Ledezma C. Human Rights at the Climate Crossroads: Analysis of the Interconnection between Human Rights, Right to Climate, and Intensification of Extreme Climate Events. Laws. 2024; 13(5):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws13050063

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz-Cruces, Eliana, María Méndez Rocasolano, and Camilo Zamora-Ledezma. 2024. "Human Rights at the Climate Crossroads: Analysis of the Interconnection between Human Rights, Right to Climate, and Intensification of Extreme Climate Events" Laws 13, no. 5: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws13050063

APA StyleDíaz-Cruces, E., Méndez Rocasolano, M., & Zamora-Ledezma, C. (2024). Human Rights at the Climate Crossroads: Analysis of the Interconnection between Human Rights, Right to Climate, and Intensification of Extreme Climate Events. Laws, 13(5), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws13050063