Abstract

Unaccompanied immigrant children arrive in the US having fled deteriorating conditions and human rights violations in their home countries. Despite the large numbers of unaccompanied children, there is a lack of research on outcomes for unaccompanied children in the US and particularly for those in the Office of Refugee Resettlement’s (ORR) Long Term Foster Care (LTFC) program. This manuscript begins with a review of the existing laws that influence unaccompanied children (UC) served through the ORR’s LTFC program and a review of the current research on UC in foster care in the US. Notably, this manuscript also visualizes the numbers of UC that have arrived in the US since the early 2000s. These are used to provide a synthesis of recommendations for policy and practice with unaccompanied children.

1. Introduction

Unaccompanied children (UC) have migrated to the United States in record numbers in recent years, but only a small proportion of these children are served by the Office of Refugee Resettlement’s (ORR) Long Term Foster Care (LTFC) program. In this manuscript, the author reviews who unaccompanied children are, how they get to the United States, and the adversities they often face. This manuscript will review the existing literature specific to unaccompanied children served through the ORR’s Long Term Foster Care program. While there is literature on unaccompanied immigrant children in foster care in other countries (e.g., Euillet et al. 2022; Horgan and Ní Raghallaigh 2019; Kalverboer et al. 2017; Rogers et al. 2018; Wade 2019), these studies are not addressed here as this manuscript is focused on policy implications within the US context. This manuscript describes the current political context for immigrants in the United States, especially unaccompanied children and undocumented immigrants. Lastly, the author provides a synthesis of recommendations for policy, research, and practice (with a focus on providing legal services to UC), taking into account how the political climate may influence the possibility of carrying out these recommendations.

The human rights of children around the globe are protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (United Nations 1948) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC 1989). Despite the fact that the US has not ratified these important documents, the author would like to argue that service providers uphold these principles in their work. Therefore, these are used as a framework to explain the human rights of UC throughout this paper. While the US has been a place for vulnerable persons to seek safety from violence and persecution for many years, the current political and anti-immigrant rhetoric in the United States has left us in a situation in which the basic human rights established through the UDHR and CRC are not always upheld for UC (Evans et al. 2020). For example, there have been human rights violations documented for UC who were held for unjustifiably long periods of time in detention (Hauslohner and Sacchetti 2019), denied enrollment in their local school (Booi et al. 2016), and denied medical and/or mental health care while in ORR funded shelters (Krueger et al. 2019). Because of all of these and more, the Human Rights Watch released a report that said the United States has reduced human rights protections for immigrants (Human Rights Watch 2019). Therefore, service providers may find it beneficial to refer back and use these statutes when advocating for the rights of UC.

2. Children Migrating to the United States Unaccompanied

According to 6 U.S.C. § 279 G2, an “unaccompanied alien child”1 is someone who does not have lawful immigration status in the United States, is under the age of 18, and has no parent or legal guardian available to provide care and physical custody. The majority of UC are fleeing deteriorating conditions and human rights violations in their home countries, such as community and gang violence, intractable poverty, social exclusion, and/or child maltreatment (Schmidt 2017; UNHCR 2014). At the same time, many are seeking to reunify with family members living in the US, to obtain a better education, or to find employment and send remittances home (Schmidt 2017; UNHCR 2014). UC have often faced multiple traumatic events during their migration journey, such as physical abuse or violence, sexual abuse, human trafficking, and gang violence (UNHCR 2014) as they travel by foot, by bus, or on top of trains over a period of weeks or months, in search of safety in the US (Griffin et al. 2014). Therefore, the journey itself can be a serious contributor to the toxic stress levels experienced by UC (Derluyn et al. 2009).

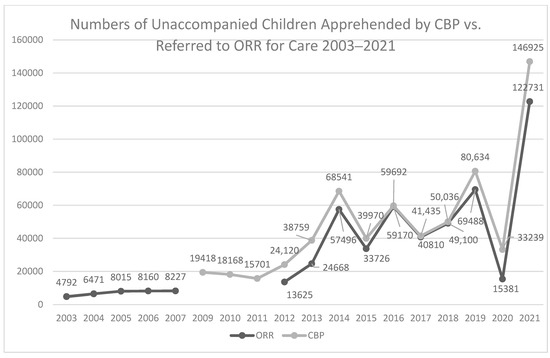

The number of unaccompanied children (UC) arriving at the southern border of the US has risen drastically since the early 2000s, with 146,925 UC apprehended in 2021, after some fluctuations over the past five years (CBP 2022). Figure 1 below shows this trend as illustrated by the number of UC referred to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) for physical care and legal custody between 2004 and 2007 (Congressional Research Service 2009), as well as the number of UC apprehended at the Southwest Border from 2009 to 2021 (CBP 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2022) and the numbers of UC referred to the ORR for placement in 2012–2021 (ORR 2019, 2022a). In each of these years, it is expected that the number of UC apprehended at the border is slightly higher than the number of those referred to ORR custody, as some youth are subject to “voluntary removal” after screening at the border as part of the special policies for children from contiguous countries (Mexico and Canada) as set out by H.R. 7311 sec. 235. For example, in 2018, there were 50,036 unaccompanied children apprehended at the border (CBP 2018) yet only 49,100 of these UC entered ORR care and custody (ORR 2019). The number of unaccompanied minors apprehended by CBP in 2020 was strikingly low due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with only 33,239 apprehensions at the border and 15,381 UC referred to the ORR (CBP 2022; ORR 2022a). However, in 2021 the number of UC is the highest yet, with 146,925 UC apprehended by CBP and 122,731 referred to the ORR (CBP 2022; ORR 2022a), showing an increased need to continue research on this group of vulnerable children.

Figure 1.

Data2 in this figure are compiled from multiple citations including: (Congressional Research Service 2009; CBP 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2022; ORR 2019, 2022a).

2.1. Apprehension and Care in the US

For many years, the care and protection of UC was overseen by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). However, advocates argued that due to cases of neglect, prolonged detention, and detention alongside adults that perhaps UC should be cared for in a manner that was more consistent with child welfare principles (LIRS 2015). This advocacy led to The Flores Settlement Agreement of 1997 which mandated standards of care for immigrant children in detention (Hasson et al. 2019; LIRS 2015). More specifically, it outlined that immigrant children detained at the border need to be moved out within three days, that once in immigration custody they are cared for in a least restrictive environment, and that they are released as quickly as possible (with the suggestion of within 20 days) to a safe caregiver or child welfare provider (Flores Agreement 1997). Additionally, the Flores Settlement outlines care guidelines for UC while in shelter, which includes providing food, shelter, health and mental health care, educational services, age-appropriate recreation, access to religious services, efforts towards family reunification, and case management services to guide all of these (Byrne and Miller 2012).

In 2002, with the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, the care and protection of UC was transferred to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (Homeland Security Act of 2002). Currently, unaccompanied children who are apprehended and lack immigration status in the US enter the care and custody of the ORR and are placed into one of 100 shelters operated by child welfare agencies and funded by the ORR (Byrne and Miller 2012; Diebold et al. 2019; ORR 2022b) as required by William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA) TVPRA § 235(b)(1). TVPRA mandates that children claiming asylum are interviewed by officers trained in hearing children’s issues and, at the same time, expanded pro bono representation to these vulnerable children. Many of these provisions were put into place to try and intercept cases of trafficking and to safeguard the due process that UC deserve (LIRS 2015) as outlined in Article 37(d) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC 1989).

The average length of stay in shelters for UC was 51 days in the 2017 fiscal year (Wagner 2018), 60 days in 2018 (ORR 2019), and 37 days in the 2021 fiscal year (ORR 2022a). All of these are longer than the suggested timeline outlined in the Flores Settlement (1997), and in a 2015 court case, Judge Dolly M. Gee found that the administration failed to uphold best practice (Preston 2015). This is also in violation of UDHR Article 37, which indicates that “The arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time”. During this time in shelter, UC case managers work to identify a safe home in which the youth can be reunified with family members, or assess the need for referral to long term foster care (ORR 2022b). The majority of youth are released from shelters to live with family members across the country (34,815 out of 49,100 apprehensions; 70.9% in 2018) (ORR 2017, 2018). For many years, only about 5–10% of UC have been given comprehensive follow-up services in the community after they have been released from shelters and reunified in communities (Jani et al. 2016); however, the Biden administration has recently allocated funding to help expand the number of youth served in post-release services and enhance the quality of case management (The White House 2023). A small number of youth without viable family reunification options remain in care and transition into a foster care placement. Long Term Foster Care (LTFC) placements provide the least restrictive environment for UC who are unlikely to be released to family members in the community. According to Section 1.2.6 of the ORR’s policy manual, UC are eligible for LTFC services if they are under 17.5 years old, are expected to be in ORR custody longer than four months, and if an attorney has screened them for potential legal relief in the US (ORR 2022b). Placements generally consist of foster homes or group homes where the child can attend school and medical appointments in the community (ORR 2022b). All foster homes are licensed in the state in which they reside, and the UC’s cultural and linguistic needs are taken into account during the placement matching process (ORR 2022b).

While in LTFC, case managers continue to assess family options for UC, but they also make significant efforts to connect UC to attorneys and begin the process of applying for legal status in the US (ORR 2022b). The majority of UC in LTFC programs successfully achieve legal status through the Special Immigrant Juvenile Visa (SIJS), but some qualify for asylum status, a trafficking visa, or a U-Visa (USCCB 2013). UC who are eligible for SIJS have been victims of abuse, abandonment, or neglect by one or both parents in their home country, are unmarried, under the age of 21, and currently under the custody of the ORR or another juvenile court; additionally, it is against their best interests to return to their home country (Immigration and Naturalization Act § 101(a)(27)(J)). An asylum seeker has suffered persecution or faces a significant fear of persecution due to “race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion” (USCIS 2018a, p. 1) and is seeking safety and protection in the USA. UC interested in pursuing a T nonimmigrant visa must have been victim of severe sexual or labor human trafficking and are seeking protection in the USA (H.R. 7311 Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008). UC may be eligible for the U nonimmigrant visa if they have suffered mental or physical abuse due to certain large-scale crimes, and if they are willing to cooperate with law enforcement in the persecution of the perpetrators (USCIS 2018b).

2.2. Legal Process

Upon their arrival at the US border, UC lack proper legal documentation to reside in the US, and this only adds to their aforementioned vulnerabilities. Research shows that the lack of legal status for UC limits their access to community resources and social service resources, negatively impacts their mental well-being, and greatly limits their ability to integrate into their communities because they are ineligible for many social programs and they fear being deported (Crea et al. 2018; Laban et al. 2008; Thommessen et al. 2015). UC are placed in removal proceedings, but are allowed to remain in the US until the conclusion of their court case (8 U.S.C. § 1232(a)(5)(D)(i)). While in shelter care, all UC receive a “know your rights” presentation that helps them to understand their status as an undocumented immigrant, and what to expect in terms of the US legal process (ORR n.d.). Upon their release to family in the community, their legal cases are transferred to a local jurisdiction, and the caregiver is expected to follow through with the immigration court proceedings (ORR n.d.). UC who enter LTFC placements are provided representation and therefore have a higher success rate of achieving legal status in the US than UC in the community (ORR n.d.; TRAC 2014).

3. Review of the Literature

3.1. Policy’s Impact on Hostility towards Immigrants

The past few years have seen public and open hostility towards different immigrant groups in the US. One result has been a large cut in the number of refugees allowed to enter the US annually, offering fewer protections for these vulnerable people (Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions 2019). In the 2020 fiscal year, the US placed the cap on refugee admissions at only 18,000 refugees, compared to 45,000 in the 2018 fiscal year and 70,000 in the 2015 fiscal year (Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions 2014, 2017, 2019). Increasing hate crimes have occurred against different minority groups, including people who identify as Latinx, Muslim, and Jewish, many of whom are immigrants (Fry 2019; Garland 2019; Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights 2019).

Prior to 2018, people who were apprehended at the US border without legal documentation were promptly returned (INA § 235), unless they claimed persecution in their initial screening (INA § 208; 8 U.S. Code § 1158). Trump’s Zero Tolerance Policy (Executive Order 13841) made efforts to deter families from seeking asylum in the US by forcibly separating parents and their children upon their apprehension at the border (SPLC 2022), creating a mental health crisis and causing strain on families that could last decades (NADD 2018; NASW 2018). More than 5400 children were separated from their parents (Associated Press 2019) and landed in the ORR system for UC. On 20 June 2018, after a significant public outcry, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) formally stopped the practice of separating families, unless there were humanitarian, safety, or criminal reasons to warrant a separation (SPLC 2022). However, there is evidence to suggest that the separations continued after this date (Associated Press 2019). More recently, we have learned that the impacts of Title 42 Expulsions and Migrant Protection Protocols have led to children entering the ORR system for UC (American Immigration Council 2022; KIND 2020).

Research shows that unwelcoming communities are increasing discrimination for UC (Androff 2016). Crea et al. (2017) noted that the increase in globalization and transnational migration has led the US to create hostile policies, many of which impact UC because of their lack of legal status in the US.

With the arrival of the Biden Administration, there has been a renewed hope for more open and welcoming US communities. In January of 2020, President Biden reversed the ban on refugees from certain countries, stopped the construction of the wall at the southern US border, restored the DACA program, and increased the number of refugees welcomed into the US (Center for Migration Studies 2017). The Biden Administration has expedited legal pathways for people from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela and has promised to decrease the immigration court backlog (The White House 2023). Specifically related to unaccompanied children, the Administration has expanded access to pro bono counsel for immigration court, expanded access to post-release services so more children can be served, and created a budget plan that better allows for sharp/unexpected increases in the number of UC that may arrive (The White House 2023). Additionally, the wide-ranging support for the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021 (House Bill 1177) shows that now may be an opportune time for community members and service providers to take action and expand our welcome to UC in our communities.

3.2. Unaccompanied Children in Long Term Foster Care

At this time, there is limited research that focuses specifically on UC served through the ORR’s Long Term Foster Care (LTFC) program, as it serves a relatively small proportion of overall UC in the United States in any given year. However, UC eligible for LTFC may be more vulnerable as they have been screened for a lack of family in the United States, and research indicates that family relationships are a predictor of positive mental health for immigrants (Obradović et al. 2013).

Because placement disruption is a well-established risk factor in state/local foster care (Beal et al. 2022; Delaville and Pennequin 2020; Fawley-King et al. 2017), including for ethnic and racially diverse youth (Tyrell et al. 2019), one study chose to examine placement stability among UC in LTFC. Crea et al. (2017), found that UC from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras as compared with UC from other countries, were more likely to have experienced a failed family reunification attempt before entering the foster care program. They also found that UC who experienced violence in their home country or who acted out significantly while in the ORR’s LTFC program in the US were associated with a higher likelihood of changing foster care placements. UC who exhibited a fear of returning to their home country and those suffering trauma unrelated to migration were associated with a lower likelihood of changing placements (Crea et al. 2017). Similarly, Crea et al. (2018) found that UC exhibit a need for stable foster care placements, and that many service providers believe language-matched foster homes are best practice. Promising practices implemented by foster care agencies for UC include personalized case management with dimensions such as culture, education, health, and mental health needs acting as service plan components (Crea et al. 2018).

In order for UC to succeed, be happy, and integrate into US communities, it is important that the community provides a welcoming environment for UC to engage (Evans et al. 2022b). Communities that focus on building capacity, utilizing relationships with community members and organizations, and systematically fighting oppression may provide a more welcoming outset (Reisch 2016). (Evans et al. 2022b) highlights a number of community-level facilitators of adjustment that can assist UC as they adjust to life in the foster care program in the US, including inter-agency collaboration, the church as an institution and bystander training were suggested as ways to inform or change the opinions of community members. Crea et al. (2018) noted a deficiency in basic knowledge about US culture, customs, and how to act among UC, which could be aided by cultural orientation training for UC as well as bystander training to increase the likelihood that UC who act inappropriately can be taught about US norms rather than reprimanded.

Research has demonstrated that schools are a critical component of adjustment and a predictor of well-being for immigrant students (Birman et al. 2007; Crea et al. 2018; Oxman-Martinez and Choi 2014). Evans et al. (2022a) found that there are individual factors that pose challenges to the academic potential of UC, including language barriers, a lack of prior education and preparedness for school in the US, difficulties navigating cultural clashes, and physical and mental health challenges. There are also system-level barriers to their success in schools, including the lack of policies around their enrollment and grade placement, and the lack of the capacity of schools to adequately serve UC (Booi et al. 2016). Schools that offer supports to UC in terms of academics, as well as language, emotional, and behavioral needs are equipping UC with the skills to reach their full potential and succeed, especially when these services are offered in collaboration with other service providers and community members (Evans et al. 2022a).

Many UC have experienced a history of abuse, abandonment, or neglect in their home country, which often prompts their decision to migrate to the US (UNHCR 2014). Hasson et al. (2021) found that a history of sexual abuse and history of neglect were both associated with adverse outcomes for UC in LTFC. Crea et al. (2018) found that UC in foster care were often reluctant to seek formal mental health services, which is consistent with other Latinx and immigrant groups (Espinoza-Kulick and Cerdeña 2022). As in other studies, positive role models and connections to people in the local community were seen as protective factors for UC (Crea et al. 2018). Evans et al. (2023) found that bilingual and bicultural staff, supportive relationships with foster parents, and adapted safety protocols were protective measures for UC in LTFC.

4. Distinctions between ORR Foster Care and Local/State Child Welfare Foster Care

The care and custody of immigrant children following detention are separate from those of US-born children who enter the child welfare system. The systems are parallel in some ways in that they are both working towards the best interest of the child and aim to reduce abuse, abandonment, and neglect for children. However, children apprehended at the border are immediately placed into care due to the lack of an available caregiver and then screening is performed to find an appropriate home/placement. In contrast, a child in a community lives with a caregiver who needs to be determined to be ineligible before the child can be removed from the home and placed into state/local child welfare placement. In both cases, the first goal is to return the children to their biological parents when possible. Similarly, in both cases, the agencies are licensed in the state in which they operate. Another distinction is that monitoring of the programs serving immigrant children is conducted by the Office of Refugee Resettlement and ensures compliance with their policies and procedures as outlined in the “ORR Unaccompanied Children Program Policy Guide” (ORR 2022b). Nonetheless, there is no interaction between these systems on a day-to-day basis. Therefore, drawing upon the literature of the mainstream child welfare system in the US to make assumptions about unaccompanied children in long-term foster care should be done with caution.

For children in state/local foster care, the major outcomes include safety, permanency, and well-being (Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) of 1997). Scholars note that the outcomes need to shift a bit for unaccompanied immigrant children. First, they note that safety needs to include not only physical safety but also emotional safety due to the trauma endured in their home country and during their journey to the USA (Crea et al. 2021). In terms of permanency, they discuss the critical roles that legal permanency and the possibility of remaining in the US play. Lastly, they note that well-being should directly include factors related to cultural integration and mental health (Crea et al. 2021). If the way we measure outcomes for children is shifted, this implies that service provisions are also tailored for UC in the ORR’s long-term foster care system. These nuances provide some rationale for the separate system for immigrant children. This is in part because the staff and foster parents are voluntarily signing up to work with immigrant youth, as well as because they are trained specifically to work with immigrant youth, in addition to the training given to staff and foster parents for state/local child welfare (USCCB 2013).

5. Next Steps: Policy and Legal Services

Scholars have highlighted the need for more work in terms of research, policy, and practice around unaccompanied children (Berger Cardoso et al. 2019). Below are some of the common themes found in their recommendations, which are extended from the information specific to UC in LTFC as well as the author’s synthesis of the state of research on UC in the current political climate in the United States.

5.1. Policy Implications and Recommendations

Title 42 has had an impact on the wellbeing of UC in a few ways over the past few years. Some UC have been unable to enter the US even though this is not how the policy was designed. Others were traveling with their family, and the family voluntarily chose to separate and send the child first, unaccompanied, because the conditions in Mexican border camps are so poor. Others who entered the US and entered ORR care were subject to longer delays in custody and family processing due to COVID restrictions. There is a national movement right now that involves countless organizations trying to end Title 42, recommending that people advocate and call legislators to end this policy (American Civil Liberties Union 2022; Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society 2022; Ignation Solidarity Network 2022).

Unaccompanied children in LTFC spend much of their time in school after their arrival in the US. When considering UC’s well-being in school environments, schools would benefit from having written policies that address the placement of children who lack formal documentation or formal education (Crea et al. 2017; Evans et al. 2022a). However, it has been noted that schools often struggle to make accommodations and changes as they are part of a larger systems and not always able to make changes for their individual school (Berger Cardoso et al. 2019; Pierce 2015). These barriers suggest the need for heightened awareness among policy makers around the unique challenges faced by local schools in terms of grade placement and service delivery. UC in LTFC have an identified caseworker, and in some cases an educational advocate, so they often have more access to services within the school than their UC peers who are not part of the LTFC program. Regardless of their participation in LTFC, all UC could benefit from special attention in schools, so social workers and advocates should clearly articulate the needs of UC in the public sphere. Advocates can mandate that public schools to meet these needs through the use of language access, enrollment, culturally relevant assessments, and tutoring, as well as access to social and emotional support and afterschool programs (Booi et al. 2016; Roy and Roxas 2011; Szlyk et al. 2020).

We know that some UC can enter the child welfare system in their county/state due to abuse, abandonment, or neglect in the US. Crea et al. (2017) recommend that child welfare practitioners work to adopt a global perspective for their work and focus on the mandate to protect UC in the traditional child welfare terms of safety, permanency, and well-being. Global child protection policies and theories clearly articulate that lacking legal status does not negate a child’s inherent human rights. Therefore, there is a need to incorporate transnational cultural competency into existing child protection policy in the US (Crea et al. 2017).

At the national level, it would be beneficial to advocate in favor of comprehensive immigration reform (MPI 2019) and policies that are more welcoming towards immigrants, especially forced migrants, such as unaccompanied children (Androff 2016). There have been attempts to pass legislation that would enable a pathway to citizenship in the US for the undocumented immigrants who came to the US as children, also known as Dreamers (Svajlenka 2019), and passing this legislation would set a precedent that could be extended to other UC. The current Citizenship Act proposal is another way to extend protections to UC and their families.

Coupled with this, in today’s political climate in the US, it is important that we push communities, cities, and states to declare themselves sanctuary cities or welcoming communities (Welcoming America n.d.). The declaration of more sanctuary spaces and bystander training—an intentional effort to provide information about UC to the general public in an effort to increase empathy and knowledge with the hopes of changing the attitudes and behaviors of community members (Evans et al. 2022b)—would help to alleviate fear, enable families to engage in the community, and to help fight against the human rights violations that are happening within the US.

5.2. Practice Implications: Legal Services

Because the circumstances of one unaccompanied child may be different than those of another, there are nuances in every case. Therefore, it is recommended that caseworkers and attorneys conduct thorough research and investigations before making assumptions and carrying out proceedings. When there is a question that is difficult, it is possible to contact the Attorney of the Day service that is provided by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, as they have qualified and knowledgeable staff on hand to assist with answering questions related to UC (Immigrant Legal Resource Center n.d.).

Unaccompanied children who have access to an attorney are far more likely to have a positive experience navigating the US court system, and may receive more favorable outcomes that allow them to stay in the US (TRAC 2014). Therefore, it is recommended that information about UC and their vulnerabilities is given to legal professionals and that more volunteer their time and efforts to take on pro bono cases or offer sliding fees scales to help these families. Additionally, partnerships between nonprofits serving UC and law schools may be a beneficial way to have law students work on cases as part of their education, and to build a pipeline of knowledgeable professionals who will hopefully continue to offer pro bono cases throughout their legal career. Organizations (e.g., International Social Service—USA) provide training to judicial and court staff on family finding, family notification, and family engagement as they relate to immigrant youth in foster care.

6. Conclusions

The United States has long been a place of safety and welcome for immigrants, especially forced migrants fleeing violence, persecution, and/or deteriorating conditions in their home country. However, with the shift in political rhetoric in recent years, many immigrants live in fear even after coming to the US (Crea et al. 2017; Miller 2018; Roth and Grace 2015). Social workers and other mental health professionals have a duty to fight for unaccompanied children’s well-being through a global child welfare perspective (Androff 2016; Crea et al. 2017) while working alongside attorneys and legal organizations to help provide longevity in the US for these children.

There are numerous state and federal policies written to protect the safety, well-being, and permanency of young persons in the child welfare system (e.g., Adoption and Safe Families Act 1997; Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008; Victims of Child Abuse Act Reauthorization Act of 2018). The Convention on the Rights of the Child, which was adopted by the U.N. in 1989, sets out the rights of children around the world and contains guidelines used in global child protection. However, the majority of policies that speak specifically to UC in LTFC are those set out by the Office of Refugee Resettlement for when the children are in their care (ORR 2022b). Within this document, there are few policies to address UC in LTFC who interact with the community where they live, and even fewer for UC who live in the general community and no longer receive any support from the ORR.

Berger Cardoso et al. (2019) emphasized the need for research to reach the hands of practitioners now, rather than waiting years to gather data from an ideal sample. Through this manuscript, the author’s intent was to share research results and use these findings to inform practice in a timely and efficient manner, consistent with the recommendation to “bridge the divide between researchers and the legal system by disseminating research to inform practice” (Miller 2018, p. 5). Moving forward, the research agenda should continue to develop in planned and rigorous ways, including the use of standardized measures and longitudinal designs. We need to encourage a global child protection view to policy making at the state and national level to ensure human rights protections for UC, and also encourage schools and foster care agencies to incorporate policies that are child-friendly and welcoming to immigrants. Policy makers and human service professionals are tasked with the ethical obligation to pursue best practice and to do no harm. As one of the most vulnerable populations currently in the US, unaccompanied children require the best we can offer.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research did not require IRB approval as no data was collected.

Informed Consent Statement

As noted above, no informed consent was required as this manuscript did not involve any data collection.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript does not draw from primary data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to share.

References

Archive Sources

8 U.S.C.A. § 1229 Initiation of Removal Proceedings.Adoption and Safe Families Act 1997American Immigration Council vs. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement & U.S. Customs and Border Protection & U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Case 1:18-cv-01531.Executive Order 13769, 82 FR 8977. Page 8977–82 (2017).Executive Order 13841, 3 C.F.R. page 29435–36 (2018).Flores Settlement Agreement of 1997.Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008. H.R. 6893/P.L. 110–351.H.R. 7311 (110th): William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008.Immigration and Naturalization Act § 101(a)(27)(J).INA § 208. (8 U.S.C. § 1158). Asylum.INA § 235. (8 U.S.C. § 1225). Inspection by immigration officers; expedited removal of inadmissible arriving aliens; referral for hearing.Victims of Child Abuse Act Reauthorization Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-424).William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA). [United States of America], Public Law 110–457, 23 December 2008.Published References

- American Civil Liberties Union. 2022. Tell Biden: End Trump’s Illegal and Inhumane Immigration Policies. Available online: https://action.aclu.org/petition/tell-biden-end-trumps-illegal-and-inhumane-immigration-policies (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- American Immigration Council. 2022. A Guide to Title 42 Expulsions at the Border. May 25. Available online: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/guide-title-42-expulsions-border (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Androff, David. 2016. The human rights of unaccompanied minors in the USA from Central America. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 1: 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associated Press. 2019. More Than 5400 Children Split at Border, according to New Count. NBC News. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/more-5-400-children-split-border-according-new-count-n1071791 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Beal, Sarah J., Robert T. Ammerman, Constance A. Mara, Katie Nause, and Mary V. Greiner. 2022. Patterns of healthcare utilization with placement changes for youth in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect 128: 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger Cardoso, Jodi, Kalina Brabeck, Dennis Stinchcomb, Lauren Heidbrink, Olga Acosta Price, Oscar F. Gill-García, Thomas M. Crea, and Luis H. Zayas. 2019. Challenges to integration for unaccompanied migrant youth in the post-release U.S. context: A call for research. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 273–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birman, Dina, Traci Weinstein, Wing Yi Chan, and Sarah Beehler. 2007. Immigrant youth in U.S. schools: Opportunities for prevention. The Prevention Researcher 14: 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Booi, Zenande, Caitlin Callahan, Genevieve Fugere, Mikaela Harris, Alexandra Hughes, Alexander Kramarczuk, Caroline Kurtz, Raimy Reyes, and Sruti Swaminathan. 2016. Ensuring Every Undocumented Student Succeeds: A Report on Access to Public Education for Undocumented Children. Washington, DC: Georgetown Law Human Rights Institute. Available online: https://www.law.georgetown.edu/humanrights-institute/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2017/07/2016-HRI-Report-English.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2018).

- Byrne, Olga, and Elise Miller. 2012. The Flow of Unaccompanied Children through the Immigration System: A Resource for Practitioners, Policy Makers, and Researchers. Center on Immigration and Justice, Vera Institute of Justice: Available online: https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/the-flow-of-unaccompanied-children-through-the-immigration-system.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- CBP (U.S. Customs and Border Protection). 2016. United States Border Patrol Southwest Family Unit Subject and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions Fiscal Year 2016. Available online: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-children/fy-2016# (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- CBP (U.S. Customs and Border Protection). 2017. U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2017. Available online: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensionsfy2017# (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- CBP (U.S. Customs and Border Protection). 2018. Southwest Border Migration FY2018. Available online: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/fy-2018 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- CBP (U.S. Customs and Border Protection). 2019. Southwest Border Migration FY2019. Available online: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/fy-2019 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- CBP (U.S. Customs and Border Protection). 2022. Nationwide Encounters. Available online: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/nationwide-encounters (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Center for Migration Studies. 2017. Available online: https://cmsny.org/trumps-executive-orders-immigration-refugees/ (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Congressional Research Service. 2009. Report RL33896: Unaccompanied Alien Children: Policies and Issues. Available online: https://www.ilw.com/immigrationdaily/news/2010,1222-crs.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- CRC. 1989. CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Crea, Thomas M., Anayeli Lopez, Robert Hasson, III, Kerri Evans, Caroline Palleschi, and Dawnya Underwood. 2018. Unaccompanied migrant children in long term foster care: Identifying needs and best practices from a child welfare perspective. Children & Youth Services Review 92: 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, Thomas M., Anayeli Lopez, Theresa Taylor, and Dawnya Underwood. 2017. Unaccompanied migrant children in the United States: Predictors of placement stability in long term foster care. Children and Youth Services Review 73: 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, Thomas M., Kerri Evans, Anayeli Lopez, Robert G. Hasson, III, Caroline Palleschi, and Libby Sittley. 2021. Unaccompanied immigrant children in foster care: Identifying and operationalizing child welfare outcomes. Child & Family Social Work 27: 500–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaville, Emeline, and Valerie Pennequin. 2020. Foster placement disruptions in France: Effects on children and adolescents’ emotional regulation. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal 37: 527–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derluyn, Ilse, Cindy Mels, and Eric Broekaert. 2009. Mental health problems in separated refugee adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 44: 291–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebold, Kylie, Kerri Evans, and Emily Hornung. 2019. Educational justice for unaccompanied children in the United States. Forced Migration Review 60: 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Kulick, Mario Alberto Viveros, and Jessica P. Cerdeña. 2022. “We Need Health for All”: Mental Health and Barriers to Care among Latinxs in California and Connecticut. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 12817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Euillet, Séverine, Mej Hilbold, Claire Ganne, Elodie Faisca, and Amélie Turlais. 2022. Emotions and involvement of foster carers preparing to welcome children arriving from war zones. Children & Society 36: 282–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Kerri, Dominique Culley, and Thomas M. Crea. 2023. The Role of the Foster Care Agency and Foster Parents in the Lives of Children who are Unaccompanied Immigrants from Central America. Child Welfare 100: 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Kerri, Gabrielle Oliveira, Robert Hasson, III, Thomas M. Crea, Sarah Neville, and Virginia Fitchett. 2022a. Unaccompanied children’s education in the United States: Service provider’s perspective on challenges and support strategies. Cultura Educación y Sociedad 13: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Kerri, Hasson Robert, III, Samantha Teixeira, Virginia Fitchett, and Thomas M. Crea. 2022b. Unaccompanied immigrant children in the United States: Community level facilitators of adjustment identified by service providers. Child and Adolescent Social Work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Kerri, Thomas M. Crea, and Ximena Soto. 2020. A human rights approach to macro social work field education with unaccompanied immigrant children. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 6: 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawley-King, Kya, Emily V. Trask, Jinjin Zhang, and Gregory A. Aarons. 2017. The impact of changing neighborhoods, switching schools, and experiencing relationship disruption on children’s adjustment to a new placement in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect 63: 141–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, Hannah. 2019. Hate Crimes Targeting Jews and Latinos Increased in California in 2018, Report Says. Los Angeles Times. July 3. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-jewish-latino-hate-crime-report-20190703-story.html (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Garland, Sarah. 2019. After a Hate Crime, a Town Welcomes Immigrants into Its Schools. The Hechinger Report. February 1. Available online: https://hechingerreport.org/after-a-hate-crime-a-town-welcomes-immigrants-into-its-schools/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Griffin, Marsha, Minnette Son, and Eliot Shapleigh. 2014. Children’s lives on the border. Pediatrics 133: e1118–e1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, Robert, III, Thomas M. Crea, Ruth G. McRoy, and Ân H. Lê. 2019. Patchwork of promises: A critical analysis of immigration policies for unaccompanied undocumented children in the United States. Child & Family Social Work 24: 275–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, Robert, III, Thomas M. Crea, Scott D. Easton, and Dawnya Underwood. 2021. Child maltreatment and substance abuse: Unaccompanied children and adverse outcomes in long-term foster care in the United States. Child & Family Social Work 27: 435–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauslohner, Abigail, and Maria Sacchetti. 2019. Hundreds of Minors Held at U.S. Border Facilities Are There Beyond Legal Time Limits. Washington Post. May 30. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/hundreds-of-minors-held-at-us-border-facilities-are-there-beyond-legal-time-limits/2019/05/30/381cf6da-8235-11e9-bce7-40b4105f7ca0_story.html (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. 2022. Take Action to End Title 42. Available online: https://www.hias.org/title42 (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Horgan, Deirdre, and Muireann Ní Raghallaigh. 2019. The social care needs of unaccompanied minors: The Irish experience. European Journal of Social Work 22: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. 2019. World Report 2019. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019 (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Ignation Solidarity Network. 2022. Protect Asylum Seekers: End Title 42. Available online: https://ignatiansolidarity.net/action-alerts/protect-asylum-seekers-title-42/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Immigrant Legal Resource Center. n.d. Technical Assistance. Available online: https://www.ilrc.org/technical-assistance (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Jani, Jayshree, Dawnya Underwood, and Jessica Ranweiler. 2016. Hope as a crucial factor in integration among unaccompanied immigrant youth in the USA: A pilot project. Journal of International Migration and Integration 17: 1195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalverboer, Margrite, Elianne Zijlstra, Carla van Os, Danielle Zevulun, Mijntje Brummelaar, and Daan Beltman. 2017. Unaccompanied minors in the Netherlands and the care facility in which they flourish best. Child & Family Social Work 22: 587–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KIND (Kids in Need of Defense). 2020. Remain in Mexico: Unlawful and Unsafe for Children. January 14. Available online: https://supportkind.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Remain-in-Mexico-Fact-Sheet-FINALv2-1.29.20.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Krueger, Paul, Dorian Hargrove, and Tom Jones. 2019. Former employees at youth migrant facility describe wide-ranging neglect of children and employees. NBC San Diego. July 24. Available online: https://www.nbcsandiego.com/news/local/Former-Employees-at-Youth-Migrant-Facility-Describe-Wide-Ranging-Neglect-of-Children-and-Employees-513167781.html (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Laban, Cornelis J., Ivan H. Komproe, Hajo B. P. E. Gernaat, and Joop T. V. M. de Jong. 2008. The impact of a long asylum procedure on quality of life, disability and physical health in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43: 507–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIRS (Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services). 2015. At the Crossroads for Unaccompanied Migrant Children. Available online: https://www.lirs.org/assets/2474/lirs_roundtablereport_web.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Miller, Allison L. 2018. Research and Policy Perspectives on Separating (and Reconnecting) Children and Parents: Implications for Families on the Border. Center for Human Growth and Development & Zero to Thrive. Available online: https://sph.umich.edu/news/2018posts/family-separation-082218.html (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- MPI (Migration Policy Institute). 2019. Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- NADD (National Association of Deans and Directors of Social Work Programs). 2018. Public Statement against Family Separation by United States Government. June 19. Available online: www.naddssw.org/pages/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NADD_Familyseperation-002.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- NASW (National Association of Social Workers). 2018. NASW Says Plan to Separate Undocumented Immigrant Children from Their Parents Is Malicious and Unconscionable. May 30. Available online: www.socialworkers.org/News/News-Releases/ID/1654/NASW-says-plan-to-separate-undocumented-immigrant-children-from-their-parents-is-malicious-and-unconscionable (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Obradović, Jelena, Nicole Tirado-Strayer, and Janxin Leu. 2013. The importance of family and friend relationships for the mental health of Asian immigrant young adults and their nonimmigrant peers. Research in Human Development 10: 163–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. 2019. United States of America. Available online: http://hatecrime.osce.org/united-states-america?year=2018 (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- ORR (Office of Refugee Resettlement). 2017. Unaccompanied Alien Children Released to Sponsors by State. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/resource/unaccompanied-alien-children-released-to-sponsors-by-state (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- ORR (Office of Refugee Resettlement). 2018. About Unaccompanied Refugee Minors. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/programs/urm/about (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- ORR (Office of Refugee Resettlement). 2019. Facts and Data. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/about/ucs/facts-and-data (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- ORR (Office of Refugee Resettlement). 2022a. Facts and Data. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/about/ucs/facts-and-data (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- ORR (Office of Refugee Resettlement). 2022b. ORR Guide. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/resource/children-entering-the-united-states-unaccompanied (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- ORR (Office of Refugee Resettlement). n.d. Services Provided. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/about/ucs/services-provided (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Oxman-Martinez, Acqueline, and Ye Ri Choi. 2014. Newcomer children: Experiences of inclusion and exclusion, and their outcomes. Social Inclusion 2: 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, Sarah. 2015. Unaccompanied Child Migrants in U.S. Communities, Immigration Courts, and Schools. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/unaccompanied-child-migrants-us-communities-immigration-court-and-schools (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions. 2019. Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2020. November 1. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-determination-refugee-admissions-fiscal-year-2020/ (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2015. 2014. Federal Register p. 391. September 30. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2015-title3-vol1/pdf/CFR-2015-title3-vol1-other-id238.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2018. 2017. Vol. 82, No. 203 Federal Register p. 49083. 2017. October 23. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2017-10-23/pdf/2017-23140.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Preston, J. 2015. Judge Increases Pressure on U.S. to Release Migrant Families. New York Times. August 22. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/23/us/judge-increases-pressure-on-us-to-release-migrant-families.html (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Reisch, Michael. 2016. Why Macro practice matters. Journal of Social Work Education 52: 258–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Justin, Sam Carr, and Caroline Hickman. 2018. Mutual benefits: The lessons learned from a community based participatory research project with unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and foster carers. Children and Youth Services Review 92: 105–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Benjamin J., and Breanne L. Grace. 2015. Falling through the cracks: The paradox of post-release services for unaccompanied child migrants. Children and Youth Services Review 58: 244–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Laura, and Kevin Roxas. 2011. Whose deficit is this anyhow? Exploring counter-stories of Somali Bantu refugees’ experienced in “doing school. Harvard Educational Review 81: 521–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Susan. 2017. “They need to give us a voice”: Lessons from listening to unaccompanied Central American and Mexican children on helping children like themselves. Journal on Migration and Human Security 5: 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern Poverty Law Center. 2022. Family Separation-A Timeline. Available online: https://www.splcenter.org/news/2022/03/23/family-separation-timeline (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Svajlenka, Nicole Prchal. 2019. The Dream and Promise Act Could Put 2.1 Million Dreamers on Pathway to Citizenship. March 26. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2019/03/26/467762/dream-promise-act-put-2-1-million-dreamers-pathway-citizenship/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Szlyk, Hannah S., Jodi Berger-Cardoso, Lois Lane, and Kerri Evans. 2020. Me perdía en la escuela. Latino newcomer youth in the U.S. school system. Social Work 65: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The White House. 2023. Fact Sheet: President Biden’s Budget Strengthens Border Security, Enhances Legal Pathways, and Provides Resources to Enforce Our Immigration Laws. March 9. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2023/03/09/fact-sheet-president-bidens-budget-strengthens-border-security-enhances-legal-pathways-and-provides-resources-to-enforce-our-immigration-laws/ (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Thommessen, S. A. O., P. Corcoran, and B. K. Todd. 2015. Experiences of arriving to Sweden as an unaccompanied asylum-seeking minor from Afghanistan: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology of Violence 5: 374–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TRAC (Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse). 2014. Representation for Unaccompanied Children in Immigration Court. Available online: http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/371/ (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Tyrell, Fanita A., Ana K. Marcelo, Duyen T. Trang, and Tuppet M. Yates. 2019. Prospective associations between trauma, placement disruption, and ethnic-racial identity among newly emancipated foster youth. Journal of Adolescence 76: 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2014. Children on the Run: Unaccompanied Children Leaving Central America and Mexico and the Need for International Protection. Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/about-us/background/56fc266f4/children-on-the-run-full-report.html (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- United Nations. 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- USCCB (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops). 2013. The United States Unaccompanied Refugee Minor Program: Guiding Principles and Promising Practices. Available online: http://www.usccb.org/about/children-and-migration/unaccompanied-refugee-minor-program/upload/united-states-unaccompanied-refugee-minor-program-guiding-principles-and-promising-practices.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- USCIS (United States Citizenship and Immigration Services). 2018a. Asylum. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-asylum/asylum (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- USCIS (United States Citizenship and Immigration Services). 2018b. Victims of Criminal Activity: U Nonimmigrant Status. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/victims-human-trafficking-other-crimes/victims-criminal-activity-u-nonimmigrant-status/victims-criminal-activity-u-nonimmigrant-status (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Wade, Jim. 2019. Supporting unaccompanied asylum-seeking young people: The experience of foster care. Child & Family Social Work 24: 383–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S. 2018. Testimony of Steven Wagner on HHS Responsibilities for the Care and Placement of Unaccompanied Alien Children. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.acfth.hhs.gov/olab/resource/testimony-of-steven-wagner-on-responsiblities-for-the-care-and-placement-of-unaccompanied-alien-children (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Welcoming America. n.d. Certified Welcome. Available online: https://welcomingamerica.org/initiatives/certified-welcoming/ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

| 1 | For the purposes of this manuscript, the word “alien” is being removed from the classification of these children in order to restore their dignity and worth of the person. Therefore, I will hereafter use the term “unaccompanied child” or “UC”. |

| 2 | It should be noted that data from 2008 are unavailable because of changes in reporting and funding that occurred around that time. The author has displayed as much as they could find available. For example, from 2003 to 2007 only ORR data was located, and from 2009 to 2011 only CBP data was found. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).