Abstract

This study is a discourse on restorative practice as a divergent epistemological ideology. It explores the field of restorative practice (RP) through thematic analysis of discursive captures from restorative practitioners and researchers within or associated with the Global Alliance for Restorative Justice and Social Justice. It includes elements of what could loosely be considered ethnographic research due to the time spent within restorative spaces, whilst analysing and processing the data. Methods include a restorative approach to research design, using online surveys as prerequisites to in-depth semi structured dialogic interviews. This led to reflexive thematic analysis, whereby three themes were constructed: the importance of congruence; evolution finding spaces for cultivation; and decentralising restorative practice through radical action. It is understood that this study takes a post positivist stance, designed to produce a discourse of participants’ views on RP as a divergent ideology. It is designed to highlight the perceptions of participants from a highly invested group and to promote a wider understanding of how RP interacts with dominant cultures. It would therefore be of interest to those implementing or growing restorative ideas within organisations.

1. Introduction

This study aims to better understand the positionality of restorative practice (RP) as a divergent ideology as articulated by a specific group of participants. Participants included practitioners and researchers within or associated with the Global Alliance for Restorative Justice and Social Justice, an invested group of restorative practitioners and researchers brought together by the Restorative Justice Council (an independent third sector body for the field of RP), Howard University (USA) and University of Gloucester (UK). The goal of the study: to capture this specific group’s discourse on RP as a divergent ideology, was pursued through the inclusion of discursive captures, where meaning is constructed, serving as tangible, visible embodiments of ideas which could then be crafted into a ‘discourse of restorative practice’. It is not designed as an implementation model, nor does it favour one approach above another, but offers a discourse of where the field of RP is now, as articulated by highly invested practitioners and researchers.

Restorative work is highly relevant to me as a Head Teacher within a restorative school and therefore my situated nature as a practitioner researcher is acknowledged within the reflexive thematic analysis (TA). The data in this study suggest that congruence is the most important factor being considered by participants. By this I am referring to harmony between different elements; however, the findings also suggest that depending on the differential between the participant’s locality and the philosophical ideas of RP, evolution or radical action are more or less likely to be selected as a tool to implement ‘oppositional’ or ‘alternative’ ideas. These ideas relate directly to the work of R. Williams (1977), which became a low fidelity theoretical framework used to support analysis. Currently, implementation of RP is highly topical in the UK due to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Restorative Justice, which aims to diversify its evidence base, by capturing how RP is successfully implemented in settings outside the criminal justice system (CJS). This study is presented through the following sections: Restorative Practice—defining the field; Theoretical Framework; Literature review; Methodology; Data and Discussion; and Conclusion. Throughout these sections, the discourse of RP was constructed into three themes, all of which relate to congruence and the local and wider contexts of restorative work. This was both grounded in the data and reflected through careful analysis of the literature. My context is within special education; however, this study would be most relevant to policy makers and leaders who are considering implementing RP.

2. Restorative Practice—Defining the Field

RP continues to be an ill-defined field, with even the most comprehensive quantitative research reviews describing it as “a broad term that encompasses an array of non-punitive, relationship-centred approaches for addressing and avoiding harm” (Darling-Hammond et al. 2020, p. 295). For accuracy, the Darling-Hammond et al. (2020) review actually references ‘restorative justice’, albeit within the education system, which some would describe as restorative practice, due to it being work outside the CJS. This difference could be described as semantics; however, in a field defined by semiotics, where language and communication are a central tool, it is essential to accurately agree the terms. The definition of restorative practice and restorative justice could be simply delineated through the wider context, e.g., restorative justice as work carried out within or alongside the CJS, whereas restorative practice being work carried out primarily in schools, social care, and other community-based settings. Calkin describes how RJ is “broadly understood within the CJS as victim/perpetrator dialogue” whereas RP has a wider remit “and far broader application… through different methods in different situations” (Calkin 2021, p. 93). This is reinforced to some extent by Hobson et al. (2022, p. 3) and Boyes-Watson (2021); others, however, define this distinction as RJ as a set of values, whereas RP becomes the operationalised practice and delivery of these values (Evans and Lester 2013). It is of course clear that “values… [can] not translate into improved outcomes if not for some form of change in professionals’ behavior…” (Zakszeski and Rutherford 2021, p. 2). It is therefore understood that whilst values may have corresponding behaviours, they are not necessarily one and the same. Others conceptualise RJ as “a growing social movement to institutionalize non-punitive, relationship-centred approaches for avoiding and addressing harm” (Fronius et al. 2019, p. 1) but do not go on to define RP, instead talking of ‘RJ practices’. Moreover, A. Williams and Segrott (2017) do not describe RP at all, instead choosing to describe restorative approaches, referencing Hopkins (2004) and the ideas of a shared philosophy and methodology of restorative justice, differing as it can “be adopted to improve the everyday environments of diverse communities and organisations as well as being used to deal with offences and problems as they arise” (A. Williams and Segrott 2017, p. 1).

Considering the above, Carolyn Boyes-Watson (2021, p. 7) asks perhaps the most prominent question: “are we all talking about the same movement?” Therefore, to situate this study, I present a working definition of RP, constructed from the collective understanding of participants.

‘An ideology grounded in relationships, enacted through positive communication, bringing individuals and communities to a place of awareness and accountability’.—Group Data Set definition

This is not presented as values and behaviours or limited to a specific context, but instead provides an ‘umbrella’, to be used in multiple settings. The early focus on definitions is important as the lack of a coherent identity is a reoccurring theme in the data and is highlighted as a key issue in scene setting for restorative literature. It is also clear that RP is a movement far from unity, occupying divergent locations, “it is both a pragmatic foundation and a banner that different sets of reformers have adopted to frame their agenda in creating social change within a particular context” (Boyes-Watson 2021, p. 7); without a clear definition; however, RP is elusive in evaluation. The ‘umbrella’ definition set out above in this study, does not provide the tangible detail or specific task analysis asked for in the work of Zakszeski and Rutherford (2021); however, it does provide a constructed definition which acts as a useful starting point to explore RP as a divergent ideology.

Before moving on, it is worth noting the terms ‘divergent’ and ‘ideology’. Ideology is perhaps best described as a system of ideas; however, in this context I specifically refer to epistemological ideology rather than political ideology. That said, the findings in the third theme (Decentralising restorative practice through radical action) begin to push that boundary. The term divergent, is used in this study to describe the concept of non-normative behaviours and ideas, those that act as alternative or oppositional to the dominant culture. When incorporating the two terms, I am describing RP as an emergent non-normative culture.

3. Theoretical Framework

This study explores the ideas of non-normative culture and RP as a divergent epistemological ideology. It therefore needs to situate itself within an appropriate theoretical framework, albeit a low fidelity model. The theoretical framework that was selected stems from the work of Raymond Williams (R. Williams 1977). For clarity, selecting this theory is designed to situate the study as ‘theory driven reflexive TA’, whereby the “researcher, deliberately seek[s] to explore or develop… analysis in relation to, one or more pre-existing ideas or frameworks” (Braun and Clarke 2021b, p. 208). Williams’ framework was selected during the research and frames the interpretative work in ideas that are “at play in the wider social and scholarly context” (Braun and Clarke 2021b, p. 209). This is a qualitative study and theory driven reflexive TA is not the same as quantitative hypothesis testing and therefore does not look to prove a theory or test the data. Equally, I did not attempt to try to ‘fit’ the data into Williams’ framework, instead “this analytic orientation recognises and acknowledges the conceptual ideas we (always) come to data and a project with, and gives them greater analytic priority in our interpretive process than in inductive-orientated analyses” (Braun and Clarke 2021b, p. 210).

Williams’ work was particularly relevant to a specific moment in time, but his body of work is still relevant and applicable today. His work is described by some as ‘undead’ (Levine 2020), implying that his ideas can exist in a space which does not need a clear lineage of time, and that his ideas, can “become dominant again, to die and then come back to life” (Levine 2020, p. 426). The key ideas applied to this study, stem from Marxism and Literature, where he articulates the idea of ‘residual’, ‘dominant’ and ‘emergent’ culture (R. Williams 1977, p. 122). The ‘residual’, “by definition, has been effectively formed in the past, but it is still active in the cultural process, not only and often not at all as an element of the past, but as an effective element of the present”, whereas the ‘emergent’ is described as where “new meanings and values, new practices, new relationships and kinds of relationship are continually being created” (R. Williams 1977, p. 123). The dominant order “does not have to silence alternatives altogether to be effective; instead it can insist on certain values as real and effective and dismiss others, casting them as purely personal or metaphysical or unthinkable” (Levine 2020, p. 425).

Whilst the description of ‘dominant’ culture is mostly assumed in his work, the residual and emergent are further clarified. Residual is described through examples of ‘organised religion’ and ‘rural life’, distinct from “the ‘archaic’ that which is wholly recognized as an element of the past” (R. Williams 1977, p. 122). The emergent, however, is ‘radically different’, moreover Williams is clear that emergent and residual culture can manifest in different ways and can be either alternative or oppositional to the dominant culture. What is relevant to this study, is that culture changes over time when the dominant culture interacts with emergent or residual ideologies, and therefore it is of interest to consider how RP positions itself within this frame. There is, however, added complexity as the residual, dominant and emergent ideas can all be present—Levine (2020) provides two examples:

“Literary history also means returning to texts from the past. Meanwhile, the academic field of literary studies serves the dominant order by solidifying the cultural capital of elites and providing workplace credentials for students… Teaching Frankenstein in an undergraduate class is therefore residual, dominant, and emergent all at the same time: reading a text that comes to us from the past, drawing on long-standing methods, preparing students to succeed in a capitalist marketplace, and offering them alternatives to dominant capitalist values.”(Levine 2020, p. 427)

This shows how a literary text can position itself across the residual, dominant and emergent. Levine goes on to identify how the emergent can also be mixed with the residual when ideas overlap, providing an example of how the ‘timeline gets scrambled’ when examining William’s own example of residual culture, ‘service to others with no reward’. This concept can of course be associated with ancient ways and organised religion, but Levine argues how it could also be recontextualised in emergent culture such as ‘non-profits’, ‘radical political activists’ and emergent movements such as ‘Black Lives Matter’ (Levine 2020, p. 426) and perhaps in RP. These examples demonstrate the complexity of William’s ideas and the nuance required to understand how culture shifts and evolves.

William’s work is particularly relevant to RP, due to the concept of creativity being distinct from ‘the order of nature’, and how in turn, this allows humans to have individual perceptions which operate within the context of a social construction of the world, “We learn to see a thing by describing it; this is the normal process of perception, which can only be seen as complete when we have interpreted the incoming sensory information either by a known configuration or a rule” (R. Williams 1961, p. 39). This understanding of constructed meaning is, however, developed further through the lens of the individual when considering ‘emergent’ culture, “The organisation of received meanings has to be made compatible with new meanings that are emerging, and this is a process of great complexity. It is not just a matter of a ‘society’ changing, but of real changes in the personal organisation of its members. Moreover, though the members share an area of common meaning, the actual process of organisation, in each individual, is necessarily personal” (R. Williams 1961, p. 48). These personal and organisational responsibilities, when considered within the theoretical framework in this study, offer a unique lens to view RP and are explored further in the data and discussion.

4. Literature Review

In line with reflexive TA, the literature review has been analysed in two phases: initially to situate the study and broadly understand the field; followed by returning to organise and analyse the literature in greater depth after analysis had taken place of the data, and after this study’s themes were constructed. This is somewhat unusual and is contrary to trying to find a gap in the literature to ‘fill’—however, it offers a unique framework for the literature review and matches with the concepts of reflexive TA (Braun and Clarke 2021b, p. 120). Whilst the literature review was not designed to reveal a research gap it does, however, reinforce the idea that RP is not a unified field which in turn drives the goal of this study: to understand the discourse of RP by invested practitioners and researchers. I understand that this is not traditional; however, by seeking the gap researchers can reproduce a “positivist-empiricist idea of research as truth-questing” (Braun and Clarke 2021b, p. 120) and this is counter to the design of this study. With that in mind, an ‘overview and context’ is provided, before discussing the literature in more detail under headings which match the study’s constructed themes.

4.1. Overview and Context

The literature on restorative work has grown extensively and is now situated across the CJS (Skelton 2021), prisons (Calkin 2021), schools (Hopkins 2004), and the wider community including supported housing etc. (Hobson et al. 2021). Within education, there are several systemic reviews (Darling-Hammond et al. 2020; Lodi et al. 2021; Zakszeski and Rutherford 2021). Outcomes of which highlight the need for further clarity of definitions; the need to better understand school readiness for RP, factors that determine implementation fidelity; and the need to gather data on successful and sustainable RJ programs “to uncover the conditions that lead to replicable examples” (Darling-Hammond et al. 2020, p. 306).

Growth of restorative work, and the discussions on implementation and replicability, pose questions regarding culture, the prerequisites for change, and how adaptions can be made to the dominant or emerging norms. These questions of adaption, of one culture or another, link directly to the three themes developed in this study and the theoretical framework set out above.

4.2. The Importance of Congruence

Congruence is central to the findings of this study. What is meant by congruence is harmony between different elements, whereby elements are not competing or in opposition. This study specifically considers congruence of values and practice, and congruence of practice within the wider context, e.g., schools within the educational context. Within schools, congruence in values and practice is highlighted as an important element, “school’s values need… to be in alignment with restorative values… Just as RP promoted and enacted the school’s values so the school’s values enabled RP to flourish. There was a symbiotic relationship between the school’s ethos and RP” (Bevington 2015, p. 110). This idea of congruence influencing culture is explored further by Hollweck et al. (2019) and is one of the arguments in favour of standardising restorative practices (Johnstone 2012). Interestingly, Bevington (2015) also recognises the need for incongruence within restorative work which could be seem as an opposing entity “Analysis of the individual interviews and the group sessions revealed the essential coexistence of apparently mutually excluding elements, e.g., flexible consistency, supported responsibility and gentle strength. Consistency is often reported as an essential element in the successful implementation of any new initiative; however, in this instance the staff interestingly presented a nuanced take on consistency, one that incorporates what may for some be a contradictory element, flexibility” (Bevington 2015, p. 211).

This first theme demonstrates the importance of congruence and how the philosophy behind RP can link to a local context, e.g., the ethos of a school. The studies referenced above show how restorative practitioners value congruence and how RP can be a philosophy in action. This is where there is congruence between what people think and what they do. Whilst this seems like a simplistic idea, there are added complexities and congruence can also mean congruence within a wider context and that some studies value ‘incongruence’, where professional autonomy is important and where RP has flexibility to respond to individual situations.

4.3. Evolution and Finding Spaces for Cultivation

Many research studies demonstrate that implementation can take place alongside the dominant culture, using spaces that are receptive to a restorative ideology. This can be within existing punitive settings such as prisons (Calkin 2021) but may also be reactions to extreme situations—“what is interesting is that societies with the most warlike cultural resources are also those with the richest survivals of restorative resources” (Braithwaite 2016, p. 87). When examining spaces for implementation, Hobson et al. (2022) highlights the importance of the ‘social, the people and communities’; the ‘political, the will for developments’; the ‘physical, the geography and facilities’; and the ‘economic, dependent on the resources available’. Their research suggests that these factors are interlinked and where one element is dominant often there will be a lack in another, e.g., “top-down, instinctually led services are more common where there is a political ‘space’ to fill, often reflected in a desire to do something differently and to improve service outcomes. Top-down services are more likely to have greater access to economic space to develop and may be able to share physical spaces with the services in which they work, for example, in police facilities. However, they may struggle with accessing social spaces, partly because of distance in mission from community needs but also because of the physical distance they may have from the communities in which they are working” (Hobson et al. 2022, p. 16). Similarly, community-led work is more likely to inhabit spaces in the community, often where physical space is available but where political and economic aspects are untrusted or inaccessible.

Education, however, represents perhaps the most fertile ground (Warin and Hibbin 2020). Primary schools and special schools seem particularly receptive to RP, the later having its own literature (Burnett and Thorsborne 2015; Procter-Legg 2022), whereas secondary education seems to offer a structural framework, perhaps in contrast to the congruence of restorative work. Many studies show successful educational outcomes and how a whole school culture can be developed using restorative ideas (Cavanagh 2007), whilst others argue that to fully realise the potential of RP, a more radical paradigm shift is required, “one that moves away from education as training to one that is much closer to the Latin root of education—educere (to lead out)” (Morrison and Vaandering 2012, p. 151). The paradigm shift happens when success is no longer “measured in behavior modification, but by the change in the quality of social relationships…” (Hollweck et al. 2019, p. 250). This notion is reinforced by Vaandering (2014) whose work on implementing RP in schools highlights the culture of control and compliance, and that the “dominant context is the one [that] rj, with its contrasting philosophy, has been seeking to enter” and that when restorative work is “situated in the discourse of behaviour and classroom management, [it] inadvertently reinforces an agenda of compliance and control rather than its intended purpose of building relational, interconnected and interdependent school cultures” (Vaandering 2014, p. 65). So, whilst education is prominent in the restorative literature there is a continuum of expectations on practice.

The second theme suggests that spaces for restorative work can be found within existing systems such as education; however, some applications act as dominant culture reinforcement and others provide emergent or alternative narratives. This is most notable within pedagogy, which could be seen through the development beyond behaviour, into of taught curriculums (Toews 2013), and by embedding restorative work within teacher training (Hollweck et al. 2019). This theme provides examples of how RP can be developed alongside or within the existing dominant culture, highlighting specific spaces for cultivation.

4.4. Decentralising Restorative Work through Radical Action

For some, evolution is not enough. This is where restorative work embodies the full meaning and weight of its principles, and acts as an oppositional force, pushing against the structures and vertical relationships of the state and individuals. Described as non-sovereign justice (Maglione 2021), this radical action is oppositional to the restorative work taking place within punitive systems, such as the CJS, arguing that RP in this context reinforces the power dynamic through the ‘victim-offender’ dichotomy. Some would argue that “restorative justice should provide spaces free from the ethical coercion to conform to idealised models of ‘law abiding citizens’. Ideas such as ‘victim-led’ or ‘offender-led’ interventions and practices such as ‘restorative cautions’ or the guilty plea as condition to enter restorative schemes, are problematic, insofar as being informed by sovereign coercion” (Maglione 2021, p. 28). This idea of a new anthropologic understanding of the ‘victim-offender’ is echoed in Fine (2018), who describes how this more critical-restorative justice treats “perpetrators simultaneously as agents and as victims, a two-fold lens through which to view wrongful behaviour as a reflection of systemic inequalities rather than just as an expression of individual pathology” (Fine 2018, p. 106). Moreover the “idea of harms or conflicts rooted in social inequality or social injustice is completely overwritten by the simplifying criminal justice label of ‘crime’” which again is reinforced by “the victim/offender dichotomy leav[ing] no room for (social, personal, cultural) overlaps between those two positions” (Pali and Maglione 2021, p. 12).

The above perhaps gives reason to believe that critical restorative work can enact social justice. Likewise, Braithwaite (2016) explores in greater detail the understanding of restorative work in terms of forgiveness and how forgiveness offers more or less congruence due to the acceptance of the dominant systems and processes, arguing that residual ideals of restorative culture are oppositional to modern westernised culture as “we do not have justice institutions that are civilized at all in the West today; therefore, we cannot expect a culture of forgiveness” (Braithwaite 2016, p. 81). In contrast RP developed in settler colonies, saw the development of restorative work which “related to local, indigenous and aboriginal traditions (such as the Native American, Hawaiian, Canadian First Nation and Maori cultures). This translated into a diverse range of restorative justice practices being used… such as conferencing and peace-making, healing, and sentencing circles” (Pali and Maglione 2021, p. 12). This is in opposition to the sovereign, victim-offender model which perpetuates rather than challenges dominant culture.

These more oppositional voices take us into the realm of social justice and the work of Davis (2018), where her work articulates the intentionality needed to transfer restorative justice into social justice:

“The essence of restorative justice involves shifting the locus of power from systems and professionals to communities and ordinary people…[therefore] school-based practitioners must develop skilful understandings of how, as a matter of course, schools and school actors produce and perpetuate such systemic inequities as racial disparities… it is essential, especially for white restorative justice practitioners interacting with youth of colour, to constantly ask themselves: ‘In the way I practice restorative justice and interact with students and educators, am I perpetuating or challenging structural inequities?’…”(Davis 2018, p. 430)

Returning to pedagogy these ideas of RP as social justice are echoed in Fine (2018), whose work speaks to authenticity, conviction and critical-restorative pedagogy, describing how RP can be used to ‘practice activism’, with a recount from a school which opened its own ‘activism unit’ after a teacher spent a day as a student. Their reflections were that it was boring and dehumanising, and that the school placed the emphasis on compliance over engagement.

This third theme shows how RP can be enacted as an oppositional ideology, which in turn could address structural inequality, contrasting with sovereign justice and the victim/offender dichotomy. The literature references how residual culture can be a powerful enabler and how the locus of power can be shifted to rethink ownership of conflict. Whilst these themes have been used as a framework for the literature review, it is important to note that they are permeable and interconnected, and that the ideas set out above, often fluctuate between themes. This demonstrates complexity, and that due attention needs to be given to the context of ideas and the way in which they influence culture.

5. Methodology

The methodology is centred on the values of RP with the goal not only to elicit meaning from restorative practitioners, but to create a restorative research process that could be experienced by participants. This ‘need’ to research in a restorative way reinforces the main finding in this study; that congruence is important to restorative practitioners. Matching with reflexive TA, I have refrained from using the term purposive sample. I approached people who are invested in RP, but it is not at all true that this is a sample of a wider population, but moreover a situated and invested group. The purposive group data set began with a community of practice. The snowballing element was launched through the mailing list of The Global Alliance for Restorative Justice and Social Justice, a group of restorative practitioners and researchers brought together by the Restorative Justice Council (an independent third sector body for the field of RP), Howard University (USA) and University of Gloucester (UK). The group is described as global; however, in practice it included 24 individuals predominantly from the UK and the USA. Participants’ occupations ranged from academics, policy makers, practitioners, and trainers. These individuals within the group had wider networks, which were used to increase the group data set size.

The data were collected in two stages: first an online survey (27 responses from the USA, UK and Europe) and then through in-depth semi-structured interviews (9 interviews, details shown below in Table 1).

Table 1.

Group Data Set Participant Information: in-depth interviews 1.

These research tools were chosen due to the geographic locations of the participants and the desire to obtain an initial broad base for which in-depth semi-structured interviews could build upon. The survey questions were designed to capture participants’ ideas in the following two areas:

- A working definition of RP;

- The alignment of RP in both the participants’ setting and their wider context, e.g., a restorative practitioner in a school might reflect on their school and then on the wider education system as a whole;

The initial survey could be completed quickly, but also gave participants the opportunity to expand on their answers. In total, 89% of respondents used these opportunities, and a large amount of qualitative data was created. This is unusual for survey data and my assumptions are that restorative practitioners are reflective people who want to share their stories. An alternative reading of this is that RP continues to be ill-defined and therefore further explanation is needed when exploring the restorative field.

The second phase (in-depth semi-structured interviews) was made up from participants who had already completed the online survey. Everyone in phase two was contacted directly by email, with a personal introduction. This was the beginning of the relational, dialogical approach. Discursive captures from these interviews are used throughout this study, mainly as embodiments of a constructed meaning, but in some cases for illustrative purposes. During the interviews, questions were asked relating to the alignment of RP to the local and wider context, with the goal of exploring restorative work as an enclave of culture. From a methodological perspective these questions were structured through dialogic interviewing (Knight and Saunders 1999). This style of interview is designed to “capture the confusions, complexities and contradictions of people’s thinking about their work” (Knight and Saunders 1999, p. 144) and to avoid ‘over-neat’ accounts, which perhaps limit the depth of the data. This method values individual perspectives, does not assume understanding, and addresses the power imbalance of interviewer and interviewee—again matching with restorative values. Throughout the interviews, I used my skills as a restorative practitioner to reinforce the restorative methodology. My aim, to show I was listening deeply and that I genuinely wanted to understand participants’ perspectives, co-constructing ideas with them, rather than just reinforcing my own set ideas. The in-depth semi-structured interviews added further depth to the survey questions by first allowing the participant to conceptualise non-normative ideas and define their own terms. These were then applied to their work and their wider contexts, e.g., “Tell me more about restorative practice in your daily life, is it important for it to be *different* *non-normative* (insert words the participant has used during the earlier questions).”

Once the data were collected, I was able to begin reflexive thematic analysis (TA). Reflexive TA is constructed through six phases (Braun and Clarke 2006, 2019). Table 2 shows the six phases of reflexive thematic analysis.

Table 2.

Six phases of reflexive thematic analysis.

An example of phase 1 in practice: Repetition was used to gain a broad understanding. As the interviews had been recorded on Teams, I could use headphones to listen back to aid concentration. During this phase, I used a journal, mostly writing down further questions I had about the data and broad observations. I listened to the recordings in a range of different orders, not just in the sequence they were recorded and tried to think about them whilst working in restorative spaces (whilst away from the data). Returning to the data, I continued journaling, made short notes, and started to reflect on how the participants conceptualised a non-normative culture, how they made sense of their realities, and what assumptions I had made about the data due to my own invested nature.

Whilst the six phases set out above may seem formulaic, it is not that simple and when using reflexive TA a researcher is required to go beyond the simplicity of domain summary, and is encouraged to understand constructionist orientations where “Language is conceptualized as active and symbolic, as creating rather than simply reflecting meaning” (Braun and Clarke 2021a, p. 6). This idea suggests that the key elements of reflexive TA (Braun and Clarke 2019), dialogic interviewing (Knight and Saunders 1999) and RP are a good fit, providing an epistemological continuity where there is alignment between research designs and procedures.

Reflexive TA is by its very nature a flexible and situated form of TA, it is therefore the researcher’s subjectivity that is the primary tool, and as a practitioner researcher, was the overriding reasons to select this methodology. Concerns therefore about bias regarding my own ideas, and the bias of a purposive group data set are irrelevant. However, to achieve high-quality analysis, numerous strategies for data immersion are required. Within this study I deployed transcription of interviews, listening back to recordings many times and the use of a journal that documented my reflections during the process. I spent time in restorative spaces documenting the questions that arose, conversations that related to the data but were not captured in surveys or interviews, and my own reflections and observations. The journal became fundamental for interpretation of data and was a prerequisite for formal coding. When reviewing the literature on reflexive TA, it was clear that “creativity is central to the process, within a framework of rigor” and that perhaps most importantly “themes are not waiting in the data to “emerge” when the researcher “discovers” them; they are conceptualized as produced by the researcher through their systematic analytic engagement with the data set, and all they bring to the data in terms of personal positioning and metatheoretical perspectives” (Braun and Clarke 2021a, p. 7).

6. Data and Discussion

The data and discussion have been presented as one section, in line with the dominant style in reflexive thematic analysis (TA). This is designed in contrast to the traditional scientific model of separate results and discussion, which “echoes an objective-scientist-ideal” (Braun and Clarke 2021b, p. 132). This study’s data and discussion present the views of the group data set, as both a narrative and a way of explaining the complexities of RP from participants’ perspectives, creating a discourse on restorative practice (RP). When referring to discourse, I am describing spoken word, how it is understood and how it is used to construct meaning. In this study three main themes were constructed: congruence of values and practice; the need for evolution by finding spaces for cultivation; and decentralising restorative practice through radical action. Other themes were discarded and whilst this study explores ideology and culture, the group data set produced extensive material, which could have been explored through alternative avenues. Themes were constructed initially by considering commonality of codes, and then by creating initial clusters. This was mainly done by hand, whilst relating them back to the theoretical framework and ideas of normative and non-normative culture. The full data set was used for theme construction and clusters were developed further using a visual mapping tool before being reviewed many times for viability. The final three themes feel distinct; however, themes two and three have what seems to be a rigid dichotomy; but can also be seen as permeable and that the discursive captures are not easily sorted into ‘either or’ categories. This highlights the complexity of the ideas that surround advancing RP and how the distinct three themes (set out in Table 3) also work together to offer a comprehensive discourse.

Table 3.

Theme Characteristics.

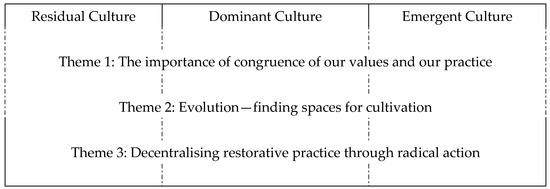

It could be assumed that the three themes fit neatly into the ‘residual’ dominant’ and ‘emergent’ categories of Marxism and Literature (R. Williams 1977); however, this is not intended or directly considered during coding and thematic development. Figure 1 depicts the theoretical framework in action with the constructed themes.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework and thematic interactions, adapted from R. Williams (1977).

6.1. Theme 1: The Importance of Congruence

This theme considers alignment between values and practice, relating to individuals, but also to the alignment of individual practitioner’s work and the systems within which they exist. Throughout the research, RP was described as a philosophy in action, at times specifically with reference to the definition provided by Corrigan (2012). Many participants described RP as ‘a way of being’, and that values translating into actions was important. When considering RP as an ideology the way in which philosophy and action interact, is an essential consideration.

“… we practice out of our philosophy… But I guess the question is… how do we invite other people to this practice if they aren’t aligned in the philosophy or they haven’t experienced it yet? … how do we find congruence between the practice and these institutions that we function in?”—Tenured Associate Professor, USA University

‘Inviting others to this practice’, seems to be a conceptually appropriate way of describing growth, influence on culture and the potential for more people to benefit from RP. This is not ‘how do we replace one system with another’—it is more nuanced. It understands successful communication and that within “workplaces, families and schools, people are happier…when [we work] ‘with’ others rather than [do things] ‘to’ [or for them]” (Boyes-Watson 2021, p. 15). This is a core concept of RP, and it should be noted that participants understood, that for change to take place, the change itself would need to embody the values and principals of RP. It was also understood by participants that by ‘inviting others to this practice’ there were certain risks, and that congruence of values and practice would need to be maintained, ensuring the values of RP were not lost enroute.

“…this push to be mainstream, whilst it comes from good intentions of wanting more people to benefit… I think we need to be careful that that doesn’t then take us into a place… where we lose the connection with the values and the spirit of it”—Restorative Consultant, Trainer, and Evaluator

This is, perhaps, our first interaction with the ideas of R. Williams (1977), where participants started to explore the push pull between how ‘inviting others to this practice’, either reinforces the dominant culture or challenges it through oppositional or alternative ideas held within residual or emergent culture. Participants seemed to be communicating a fear that by becoming more mainstream, RP would have to adapt and align more closely with the dominant culture, reinforcing rather than challenging the system.

During the initial stage of data capture, participants answered survey questions on alignment between the values of RP (self-defined) and their organisations. They also reflected on the alignment of the local and wider context of their organisations, e.g., schools within the education system; prisons within the CJS. Congruence between values and practice, and organisations and systems, was essential to participant’s discourse. Participants reported higher levels of congruence between restorative values and organisations, than between organisations and their wider context.

Participants demonstrated that they were aware of the need for congruence, but also the associated complexity. Moreover, they questioned the notion of context and I found myself rethinking how I defined the wider context.

“So when you talk about… my context, for you immediately education is your context. But I look at you and I think surely there’s so much more context to [you] than just education… for me, I think about it when I’m in the park or when I’m working with my kids when I’m in the shop, when I bump into harm. Wherever harm appears… So the context for me is wherever I find myself required to be present.”—Restorative Justice Practitioner, Forensic Mental Health

All participants felt their organisations had greater congruence with restorative values, than their wider context, and that they highly valued congruence of philosophy and practice. This core concept was mirrored in many different contexts, including academia. I have tried within this study to research in a restorative way; however, this is complex and participants from academia reinforce this complexity. They described an incongruence in the wider systems, processes, and context, and that for a restorative researcher there are systemic barriers which prevent congruence. Systemic barriers to congruence could be related to westernised culture, capitalism, and industrialisation. This is a sweeping statement—however, participants identified that aligning congruence of values and practice, was in opposition to westernised norms.

“RP [as] an ancient tradition that honours humans as social beings whose need to belong, to be seen, to be respected is central to community peace and cooperation… RP matches my beliefs and personal traditions that I follow and have used for many years. RP [has] put a recognisable contemporary name on an ancient way of life.”—Restorative Consultant, providing training to schools in the district of Columbia

Not only do these comments describe RP as an alternative narrative, but they also demonstrate how participants understood restorative work as residual culture. R. Williams (1977) describes how residual culture can relate to ancient ways or organised religion “A residual cultural clement is usually at some distance from the effective dominant culture, but some part of it, some version of—and especially if the residual is from some major area of the past—will in most cases have been incorporated into the effective dominant culture” (R. Williams 1977, p. 123). Participants also acknowledged issues around the hidden nature of RP and how ‘inviting more people to benefit’ was complex in a siloed field.

“We see lots of different practice in lots of different contexts… But it’s always… very siloed and the minute you move out of the criminal justice system… it then almost goes underground…”—CEO, Restorative Organisation

This first theme of congruence is all about alignment and how the restorative philosophy is not lost in action. Participants were clear that this matters and that it crossed the border of their work into their personal lives. Participants articulated that there is a measurable difference in congruence of local and wider contexts and that to enable more people to benefit from RP the field needs to address the siloed nature and ensure stakeholders know and understand what constitutes RP. The final aspect of congruence was the way in which restorative practitioners had congruence with one another. Many participants talked about the influence they had on one another and the positive impact a community of practice was having on their work.

6.2. Theme 2: Evolution—Finding Spaces for Cultivation

The second and third themes have interlinked identities, whilst also occupying binary oppositions. This is the difference between radical change and finding spaces that can evolve within the dominant culture. What makes the second theme distinct, is that this is not about radical system change, but instead multiple systems co-existing and integrating. Participants felt that many sites for cultivation sat outside the CJS highlighting schools as the most fertile ground. They understood that evolution in education could be nuanced, allowing for subtle shifts whilst speaking in a pragmatic and realistic way. In some respects, this felt like a tamer version of RP which would be more palatable to the dominant culture.

“I come to this kind of stuff… [from] a better approach rather than the sort of tear everything down and build everything back up again… You know, you can cling onto your principles of being a purist… Or you can do something that genuinely makes a difference to people’s lives. You can improve the [current] system… yes, it might lose a bit of its radical sting, but perhaps that’s what it needs to do…”—Academic, UK HE institution

These ideas of a ‘tamer’ version of RP could be aligned with other practices which are perhaps more successful, in vogue, or more likely to attract funding. Within education potential sites include trauma informed practice, nurture groups and special education. Participants could also see these links and one broader educational concept that many participants referenced was positive peace (Cremin and Bevington 2017). Some specifically referenced special education, which is my background. For many reasons special schools represent a site for ‘alternative’ culture and often educational professionals talk of ‘alternative provision’ alongside these systems. I would argue that they represent a different narrative within the educational system that can be adapted, a place where the focus can be shifted, and where alternative pedagogical and behavioural strategies are expected.

“I was in special education the same as yourself, so you know, a lot of our class sizes were small which makes that sort of approach far easier. I’m not sure how easy that would be if you’re in a class of 30 plus to do that… The biggest challenge actually was getting the adults to think differently…”—CEO, Restorative Organisation

Whilst there is a perception that small class size is the reason that special schools are receptive to RP, this participant also begins to touch on the ideas around mindset and how adults need to think differently to adopt RP. The issues around class size, are understood by this study, but simply accepting this observation narrows the discourse. If, however, we begin to rethink what we do, there are far greater possibilities. This could be in the form of classroom expectations, pedagogical approaches and where we situate RP, e.g., no longer only situating RP in the behavioural box. This is explored later, but staying with special schools for now, one participant talked of the confusion around RP only being embedded in special education.

“It does seem a little bizarre. Why would you do that [RP] with students whose behaviour is really challenging [in special schools] and not with students who just have challenging behaviours [in mainstream]? …I think some of it has to do with time. [When] you’re working with children who have special needs you’re going to give them more time to do everything…”—Restorative Consultant, providing training to schools in the district of Columbia

This idea of giving time to resolve issues and teaching children to resolve conflict was simply seen by some participants as the basic skills children require. However, returning to the theoretical framework, these spaces for cultivation generally occupy an area of ‘alternative’ narrative rather than being ‘oppositional’. Most of the successful educational examples are not in competition with the mainstream, e.g., they are already alternative spaces where different strategies are expected.

One key area for evolution seems to be pedagogy. This is a subject covered extensively by restorative academics (Vaandering 2015) and it was clear from the data that participants valued the opportunities in this area. They talked about how pedagogy offered an opportunity to ‘repackage’ RP, which could be more palatable to established educational professionals. Repackaging of RP is clearly evolution and not radical action; however, the data and the literature review show that restorative pedagogy has the potential to be radical action and it could be argued that by not acknowledging the oppositional viewpoint of a restorative pedagogy, opportunities are being missed to fully understand the restorative concepts that drive this ideology. This is explored further in the last theme. The ideas around repackaging RP link to its less confrontational side, one which identifies as evolution. Participants spoke of how this would be a better way of getting people on board and one participant found the ideas of a lived experience where congruence impacted all parts of your life, too strong and almost evangelical.

Evolution was also mentioned within the CJS, where all participants talked of areas for evolution, with one participant describing evolution through diversion.

“I guess… it’s more about diverting it out of the penal criminal justice system. So that means…you go through the process of being arrested and then you get processed by the system and then… whether you go to court or whether… it gets settled outside of court… It’s more about this idea of bypassing that whole process”—Senior Lecturer of Criminology, UK University

This may seem to be radical emergent culture where the CJS is being opposed; however, when considering the theoretical framework, I would argue that this example is not ‘oppositional’ (R. Williams 1977, p. 114). Much of the literature reinforces this, arguing that it is a misconception, and that the use of restorative youth disposal orders, can be understood as reinforcing the dominant ideology (Maglione 2021, p. 28). It is, however, an ‘alternative’ method which can be aligned with the dominant culture.

Culture is by its very nature a situated concept and is often cited as a barrier or enabler to further growth of RP. Some participants suggested that RP has greater opportunities within cultures where there are histories of managing conflict (aligning with the core values of RP), whilst others challenged these views. All participants talked about ‘residual’ culture, with over half of the participants specifically referencing Africa and Australasia as places of origin and therefore sites of cultivation. Whilst RP does have roots in indigenous and aboriginal traditions (such as the Native American, Hawaiian, Canadian First Nation and Maori cultures) not all participants reinforced this alignment.

“I think sometimes we in the West… romanticise certain cultures that oh, like, over in Australia, they’re all doing restorative practices and they use the Maori way, and then I’ve talked to people who are studying there, and they’re like, no, it’s really not like that.”—Tenured Associate Professor, USA University

It would be naive to make generalisations from the above; however, we could posit that the ideas of residual culture and historical conflict resolution are important to the field and perhaps offer alignment opportunities for evolution.

Some participants talked of how their organisations were receptive to RP but went on to explain that RP did not change the organisation, providing examples of how things were amended to become more relational, whilst only affecting individuals rather than systems. Others, however, felt these individual interactions could affect change more broadly and had the potential to effect policy.

“So, I’m working right now with the Colorado Department of Corrections and a specific prison to see like, can I create collaborative dialogues within the prison between staff and incarcerated people… result[ing] in better policymaking in the institution that better leads, [and] creates conditions for justice and people inside the institution and the community. So, it’s sort of like on a macro scale. Can I use the practices and the principles of restorative justice…to help to affect the way that the institution makes decisions”—Tenured Associate Professor, USA University

The above ideas were reinforced by the same participant as they reflected on their early work implementing change in the CJS. It seems that they understood that small scale projects and direct interaction with people can affect policy, but likewise policy may not affect practice without the people on the front line living and embodying RP.

“… for me, the major limitation and opportunity is around culture. I think that when I started my work in restorative justice, I started by focusing on understanding how and why restorative justice legislation was adopted in different U.S. states because I just wanted all states to have more restorative justice policy… As I got into that work, I realized that those policy adoptions had very limited impact because what actually happens on the ground… is the day-to-day decisions of people who work… in institutions… so regardless of what laws are passed or policies are passed, if the people who work in those institutions can’t really operate as individuals from a restorative framework… then the application of restorative justice to me is like very [limited]…”—Tenured Associate Professor, USA University

This second theme embodies evolution, rather than radical action. It demonstrates that participants felt that change could occur through small amendments to practice and that you could align RP with the dominant culture, and that RP did not necessarily need to be oppositional. Some participants felt this would be more successful, as radical thought was not always appreciated, especially within education. Education was, however, identified as a site for evolution and there were specific areas of education that were more receptive, e.g., special education. Likewise, other areas outside of the CJS were sites of fertile ground, with participants talking about health and social care, as possible allies to education and RP. These areas for development are reinforced in the literature (Hobson et al. 2022). One of the most powerful thoughts within this theme seemed to be the idea of how you sell RP to people. Participants talked of avoiding a wholesale approach and avoiding concepts such as how RP effects your whole life, but instead demonstrating that evidence supports implementation and that RP has tangible effects on current issues, e.g., staff retention, finance, and wellbeing. In contrast, ideas of a change in ‘ideology of how people approach the world’ is embodied in the third theme, decentralising restorative practice through radical action.

6.3. Theme 3—Decentralising Restorative Practice through Radical Action

The third theme can be described as radical action and demonstrates how RP can sit in direct opposition to the dominant ideology. This can be found in specific RP literature (Maglione 2021) and is in direct contrast to the ideas of evolution in the second theme. It is how RP by its very nature clashes with the sovereign justice ideals of the west and that for RP to be truly embraced it cannot simply sit within, or alongside a contrasting system. RP in this theme becomes a separate ideology, and a belief system that has the potential for significant cultural change. For Christie (1977) in some respects this means abolition. “Maybe we should rather abolish institutes, not open them…My suspicion is that criminology to some extent has amplified a process where conflicts have been taken away from the parties directly involved and thereby have either disappeared or become other people’s” (Christie 1977, p. 1). This was written in 1977, so whilst it could be considered that non-sovereign justice (Maglione 2021) and what I would like to describe as critical RP, is a contemporary theme; it is perhaps more accurate to say that there is a non-linear approach to the restorative literature, whereby evolution and radical action are constantly in competition with one another rather than there being a linear move from one to the other.

The data in this study reinforce the literature’s dichotomy. Some also posit the view that the CJS and education system would have a significant need to pivot and reposition if we were to considered crime as harm on communities rather than individuals. Throughout this theme, participants described a broken system trying to be fixed and talked about the difficulties with evolution over revolution.

“There’s a lot of people across all sorts of sectors where you are, you’re just trying to fix what’s there, that we know is broken. Which makes it very hard to do. It’s almost just like constantly putting sticking plasters [on for]ever. But when you listen to actually it doesn’t matter what’s there, it’s what is it that we want. So, to say not focusing on trying to make something slightly better or something different. It it’s almost having that ability forget that exists and in this ideal world, what is it that we want?”CEO, Restorative Organisation

This theme is radical and could be described as oppositional, emergent culture within William’s theoretical framework. We may also consider some of these voices as brave, to even speak to this theme. Many of the participants were established leaders and it was noted how carefully they chose their language. The idea of radical action and critical RP is perhaps quite extreme, especially when considering wholesale systemic change. In my professional context this more radical side to RP does not seem daunting; however, my reflections are that working in a very specific context (special education) and within an established restorative school, I can perhaps be much more receptive to critical RP. Participants in this study understood that radical RP was an ‘oppositional’ idea, and even described it as ‘disruptive’ and ‘needing to remain outside of the institution’ for it to remain powerful.

“The more you institutionalise restorative justice or restorative practices… the more it loses its transformative and radical element… there’s a decent disruptive element… and once you start absorbing it, once you start institutionalising it. The practice takes on a bit of the flavour… of the system … and there are some people… that have really objected to that… that by institutionalising restorative justice, [it] means it loses its power.”—Academic, UK HE institution

Participants also addressed this point through the lens of complexity. Rather than completely removing one system and replacing it with another they described how RP could be effective through radical action which makes radical change to a system without removing the system. Within education, I would argue that there are significant structural and systemic norms. Addressing these norms can be seen in staffing, pedagogy and zero-tolerance. Zero-tolerance generally refers to not accepting a certain behaviour and having a predefined consequence, e.g., automatic suspensions for knife crime within schools. Reframing this as zero-tolerance on suspensions allows educators to work within the educational frame whilst at the same time offering radical action through implementation of RP. More subtle examples included the discursive capture below, which defines the idea of added complexity.

“…as soon as you step into any organizations, there are choices you have to make which will reduce complexity. [In our school we] wanted to make sure that the relationships have still got the flexibility to be able to respond and allow for that unpredictability… So [at our school]… [which] is just a normal kind of mainstream school, over 50% of our staff are support staff. That’s a deliberate choice, because what it does is it creates capacity in ways that allows for complexity to be held…”—Director of Research and Development, Restorative School

It would be wrong not to acknowledge the link here between the staffing structure of this school and the way in which most special schools are organised (i.e., high proportion of support staff) and the links to a previous participant’s comments on ‘having the time’ to address the social and emotional needs of children. This solution, however, creates complexity which sits in opposition to a behaviourist approach whereby you have simple punitive sanctions for given behaviours. It requires adults to invest in young people and to understand their realities, and at times to accept that the environmental, institutional, and structural factors all have a part to play.

Many participants talked about how RP allowed them to have professional autonomy, and to explore the above ideas of complexity. They described having the confidence to keep the challenge high, not shy away from difficult conversations, but that currently within most mainstream school systems there is a need to reduce the complexity. This issue of reducing complexity was attributed to the way in which these institutions are organised and produce daily challenges that I would argue link to the ideas of Merton (1938) and strain theory.

Strain theory occurs when individuals have limited access to normative means which are culturally celebrated. Much like the police officer who signs up to the false reality of chasing robbers and cleaning up the streets, in reality the “cultural emphasis on police as noble, masculine ‘crime-fighters’ occupies a disproportionate relationship to the availability and/or efficacy of institutionally accepted means” (Parnaby and Leyden 2011, p. 249), therefore their reality within this career is very different to their expectations. Perhaps RP offers the possibility to explore an educational frame where the means match the cultural expectations. These ideas would also explain some of the sites of fertile ground set out in the previous theme, e.g., special schools could be repositioned within the Mertonian lens as either ‘rebellion’ or perhaps ‘innovation’. These are two of the four domains described by Merton (1938): innovation, ritualism, retreatism and rebellion, all of which are a response to when “structure[s] restricts access to the means necessary for achieving success (however, it is culturally defined), the social system becomes anomic and the normative capacity of institutions to regulate human behaviour is diminished” (Parnaby and Leyden 2011, p. 250). The first category of ‘innovators’ reject the institutionalised means but still work towards the ‘culturally prescribed goals’, these people think in different ways and use different strategies to achieve the educational outcomes they are looking for. It would be reasonable to say that within special schools not only are practitioners ‘innovators’, but that their goals are often different or differently articulated to mainstream practitioners. It is understood that strain theory is not designed to be applied in this way to the educational field and that it was originally constructed to understand deviant behaviour within the field of criminology. That said, it may be a useful tool when considering why RP has been successfully implemented in some areas and not others.

RP when implemented in a radical way has great potential to change education. Participants discussed pedagogy and how this had a transformative potential “setting the challenge within the context of engaged and productive pedagogy is a beginning step that uncovers the need for educators, administrators and policy-makers to become conscious of their view of humanity, the underlying motives of the educational institution and the impact they have as adults in their relationships with students and colleagues” (Vaandering 2014, p. 78). This is much bigger than the more simplistic educational environments where complexity has been reduced and I would argue, it has profound impacts on the need for highly reflective practitioners within the educational frame. This is a significant shift from the current normative school culture described by Vaandering (2014, p. 78) as “institutional context[s] designed to instil attitudes of obedience and conformity”.

The third theme, decentralising restorative practice through radical action, describes RP as oppositional to the normative dominant ideology. It does not allow for RP to flex to realign itself within or alongside the dominant culture and holds RP accountable to its core principals. It includes examples of non-sovereign justice, innovative educational organisations and how RP could be considered as an ‘innovative’, ‘ritualist’ or ‘rebellious’ response within the field of strain theory, whilst applied to education. It is also important to note that whilst themes two and three are clearly defined and seem to be in direct contrast, there are many overlapping topics, ideas and some of the discursive captures could quite easily be applied to either theme. It would, therefore, be naive to think that the dichotomy set out in the terminology is also reflected so accurately in the practical examples.

7. Conclusions

This study is situated within the context of restorative work and looks to better understand participants’ perspectives, whilst building a discourse on RP. It also considers culture change, the ideas of a divergent ideology and the notion of inviting more people to benefit from RP. Reflexive TA took place to construct themes from data which were created through a short survey and in-depth semi-structured interviews. This resulted in three themes: the importance of congruence; evolution and finding spaces for cultivation; and decentralising restorative practice through radical action. These three themes have clear overlapping elements and are also reflected in the academic literature which is summarised above using the same three themes. The data show that whilst there are many commonalities, RP is not an aligned movement. Within the field, practitioners have different stances and the work that is being carried out is also highly varied. Whilst these different stances can be drawn into the dichotomous themes of evolution and radical action, it would be unauthentic to say that participants were clearly positioned in either or category. They were, however, able to discuss the push pull between the themes and could see their work at times landing on either side. Likewise, participants did not agree or disagree with one another, instead they articulated the ambiguity of RP and how it could be many things all at once. One key point which seems to be agreed upon is that RP is a philosophy in action, but even this simple descriptor is complex as the main difference between the second and third theme is the depth to which participants embodied the philosophy and enacted it within their practice. It could be assumed that this lack of cohesion within the field is perhaps a reason that RP has not been implemented into the dominant ideology; however, this is a posited idea rather than a clear outcome from the research. What can be shown is that congruence is important to both RP and to its implementation. Themes two and three could also be considered within the frame of congruence and I would argue that the main idea, constructed from the data is congruence and its sub themes.

The data suggest that there are two main routes for growing RP. The first through evolution and the second through radical action. It could be argued that the dichotomy between these two routes has slowed the implementation of RP. The data also suggest that the local setting that the participant is in has a huge effect on where they sit within the three themes. Again, a personal reflection is that I can afford to be more radical within my professional context due to the specialist (alternative) nature of my school. During the data and discussion, this was explored through the lens of Mertonian Strain Theory (Merton 1938) which is not designed to be used in this context but perhaps offers a unique perspective on why RP is ‘allowed’ to grow in specific contexts. Further research conducted in special schools using the Mertonian theoretical framework would be of great interest. Spaces for restorative development are heavily referenced in the literature (Hobson et al. 2022; Warin and Hibbin 2020) mainly focussing on social, political, physical and economic characteristics. All these aspects relate directly to strain theory and reinforce the ideas of this study. Although strain theory was used, it was not the main theoretical framework. The ideas of R. Williams (1977) were used throughout this study as a low fidelity approach. The main findings from this reinforce the push pull between evolution and radical action, and the need to ensure congruence of philosophy and practice is not lost within any kind of implementation. The data in this study showed that often, RP did not match with participants’ wider contexts and that participants were more able to implement ideas within the third theme of radical action where their local contexts were aligned with the philosophy of RP. It is important to note that practitioners implementing RP whilst using the third theme, would need to consider systemic change and would most likely need to address organisational hierarchy, assuming they are looking to successfully implement RP into existing organisations. Practitioners implementing RP through the second theme would need to be highly creative in their approach to ensure RP is aligned to existing practice. These themes are not operationalised in this study and a further study would be needed to provide this level of detail.

This study would, however, be of use to educators considering culture change, researchers, and policy makers alike. Understanding the field is critical to its further development; however, this study suggests that understanding the specific local contexts where RP is being developed is of equal value and is essential to successful change.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Lancaster University on 11 March 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethics.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken as part of the MA in Education and Social Justice in the Department of Educational Research at Lancaster University. I am pleased to acknowledge the contribution of tutors and peers in supporting the development of this study and its reporting. Specifically, I would like to acknowledge the advice of Murray Saunders for comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bevington, Terence. 2015. Appreciative evaluation of restorative approaches in schools. Pastoral Care in Education 33: 105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boyes-Watson, Carolyn. 2021. Looking at the past of restorative justice Normative reflections on the future. In Routledge International Handbook of Restorative Justice. Edited by Theo Gavrielides. New York: Routledge, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, John. 2016. Redeeming the ‘F’ Word in Restorative Justice. Oxford Journal of Law and Religion 5: 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11: 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021a. Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis. Qualitative Psychology 9: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021b. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, Nick, and Margaret Thorsborne. 2015. Restorative Practice and Special Needs: A Practical Guide to Working Restoratively. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Calkin, Charlotte. 2021. An exploratory study of understandings and experiences of implementing restorative practice in three UK prisons. British Journal of Community Justice 17: 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, Tom. 2007. Focusing on relationships creates safety in schools. Set: Research Information for Teachers 1: 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, Nils. 1977. Conflicts as property. The British Journal of Criminology 17: 1–15. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23636088 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Corrigan, Mark. 2012. The Evidence Base for Restorative Practices in NZ. Available online: http://www.rpforschools.net/articles/School%20Programs/NZ%20Ministry%20of%20Education%202012%20Restorative%20Practices%20in%20NZ%20The%20Evidence%20Base.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Cremin, Hilary, and Terence Bevington. 2017. Positive Peace in Schools. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, Sean, Trevor A. Fronius, Hannah Sutherland, Sarah Guckenburg, Anthony Petrosino, and Nancy Hurley. 2020. Effectiveness of Restorative Justice in US K-12 Schools: A Review of Quantitative Research. Contemporary School Psychology 24: 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Fania. 2018. Whole school restorative justice as a racial justice and liberatory practice: Oakland’s journey. The International Journal of Restorative Justice 1: 428–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Katherine R., and Jessica N. Lester. 2013. Restorative justice in education: What we know so far. Middle School Journal 44: 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Sarah M. 2018. Teaching in the Restorative Window: Authenticity, Conviction, and Critical-Restorative Pedagogy in the Work of One Teacher-Leader. Harvard Educational Review 88: 103–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronius, Trevor, Sean Darling-Hammond, Hannah Persson, Sarah Guckenburg, Nancy Hurley, and Anthony Petrosino. 2019. Restorative Justice in US Schools: An Updated Research Review. Available online: https://www.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/resource-restorative-justice-in-u-s-schools-an-updated-research-review.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Hobson, Jonathan, Brian Payne, Kabba Bangura, and Richard Hester. 2022. ‘Spaces’ for restorative development: International case studies on restorative services. Contemporary Justice Review 25: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, Jonathan, Brian Payne, Kenneth Lynch, and Darren Hyde. 2021. Restorative Practices in Institutional Settings: The Challenges of Contractualised Support within the Managed Community of Supported Housing. Laws 10: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollweck, Trista, Kristin Reimer, and Karen Bouchard. 2019. A Missing Piece: Embedding Restorative Justice and Relational Pedagogy into the Teacher Education Classroom. The New Educator 15: 246–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, Belinda. 2004. Just Schools: A Whole School Approach to Restorative Justice. London: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, Gerry. 2012. The Standardisation of Restorative Justice. In Rights and Restoration within Youth Justice. Edited by Theo Gavrielides. Whtby: de Sitter Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, Peter, and Murray Saunders. 1999. Understanding Teachers’ Professional Cultures Through Interview: A Constructivist Approach. Evaluation & Research in Education 13: 144–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Caroline. 2020. Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (1977). Public Culture 32: 423–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, Ernesto, Lucrezia Perrella, Gian Luigi Lepri, Maria Luisa Scarpa, and Patrizia Patrizi. 2021. Use of Restorative Justice and Restorative Practices at School: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maglione, Giuseppe. 2021. Pushing the theoretical boundaries of restorative justice Non-soversign justice in radical political and social theories. In Routledge International Handbook of Restorative Justice. Edited by Theo Gavrielides. New York: Routledge, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, Robert K. 1938. Social Structure and Anomie. American Sociological Revie 3: 672–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Brenda E., and Dorothy Vaandering. 2012. Restorative Justice: Pedagogy, Praxis, and Discipline. Journal of School Violence 11: 138–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pali, Brunilda, and Giuseppe Maglione. 2021. Discursive representations of restorative justice in international policies. European Journal of Criminology 7: 14773708211013025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnaby, Patrick F., and Myra Leyden. 2011. Dirty Harry and the station queens: A Mertonian analysis of police deviance. Policing and Society 21: 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procter-Legg, Thomas. 2022. Practitioner Perspectives on a Restorative Community: An Inductive Evaluative Study of Conceptual, Pedagogical, and Routine Practice. Laws 11: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, Ann. 2021. Human rights and restorative justice. In Routledge International Handbook of Restorative Justice. Edited by Theo Gavrielides. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Toews, Barb. 2013. Toward a restorative justice pedagogy: Reflections on teaching restorative justice in correctional facilities. Contemporary Justice Review 16: 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]