Abstract

This paper addresses the possible roles of private actors when privacy paradigms are in flux. If the traditional “informed consent”-based government-dominated approaches are ill-suited to the big data ecosystem, can private governance fill the gap created by state regulation? In reality, how is public–private partnership being implemented in the privacy protection frameworks? This paper uses cases from APEC’s Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as models for exploration. The analysis in this paper demonstrates the fluidity of interactions across public and private governance realms. Self-regulation and state regulation are opposing ends of a regulatory continuum, with CBPR-type “collaboration” and GDPR-type “coordination” falling somewhere in the middle. The author concludes that there is an evident gap between private actors’ potential governing functions and their current roles in privacy protection regimes. Looking to the future, technological developments and market changes call for further public–private convergence in privacy governance, allowing the public authority and the private sector to simultaneously reshape global privacy norms.

1. Introduction: Informed Consent in a Datafied World

Global governance of privacy is in flux. For decades, privacy self-management based on informed consent (commonly known as notice-and-consent or “notice-and-choice”), has been the key component of privacy regulatory regimes. As reflected in the privacy protection frameworks of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the European Union (EU), and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), concepts such as “purpose specification” and “use limitation”, together with individuals’ positive consent to personal data collection practices, legitimize almost all types of collection and use of personal data.1

Along the path of technological developments and market changes, this consent-centric regime is facing increasing challenges, primarily regarding its feasibility, if not its legitimacy. In these critiques,2 the central question is how to ensure that consent is meaningful in a manner that serves the purpose of giving people purposeful control over their data.3 Commentators contend that the notice-and-consent mechanism may function well in situations where consumers always devote sufficient time and attention to their privacy choices, and where service providers completely adhere to their privacy terms.4 In the real world, however, both the “notice” and the “consent” components are problematic in today’s complex information society, where data collection from cameras, microphones, sensors, and new facial recognition technologies is too ubiquitous to be sufficiently described under meaningful “notice”. We are now living in a datafied world.5 It is simply unrealistic to issue a notice and obtain consent from every individual whose images are captured by facial recognition cameras installed on sidewalks or in supermarkets. The reality is that more and more personal data is passively obtained.6 For example, retail stores across the country are increasingly using facial recognition systems in their stores for security and operational purposes. With facial recognition technology installed, retailers are able to bar people with criminal records from entering, recognize shoppers upon entry into the store, provide personalized information and services, monitor staff members who take too many breaks, and, more importantly, collect information for future targeted marketing.7 To summarize, an increasing proportion of personal data is now being passively collected through constant surveillance and tracking.8 In daily life, people’s faces are often scanned without being provided proper “notice”. When data collection occurs passively through surveillance technologies, how can individuals be meaningfully informed and thus consent to it?

At the same time, the “consent” component is equally if not more troubling in our daily lives. It has been empirically proven that privacy policies are “notoriously” long.9 Twitter’s privacy policy, as an illustration, is 19 pages in length.10 There are endless examples of privacy statements that are impossible, or at least impractical, for consumers to read, much less comprehend their legal implications. In most cases, consumer consent is arguably illusory, with consumers allocating only a few seconds of very limited attention to quickly scan the “offer” and then “accept” it without an adequate understanding of the transaction.11

In short, global governance on privacy is becoming increasingly complicated in the age of big data. In particular, the trend towards ubiquitous data collection and the explosive volume and variety of data processed today make the “notice and consent” framework, which has been an important pillar of privacy regulation, more and more problematic in practice. This paper begins by exploring how the “notice” and the “consent” components operate in a datafied world and arguing that new technological capabilities are accelerating the problems associated with privacy self-management as defined by Solove. The second part of this paper addresses the interaction between public and private actors in the context of privacy governance. We borrow the analytical framework from Cashore et al.’s “typology of interactions of private authority with public policy” and stress that the public and private sectors can either collaborate or coordinate in privacy governance, depending on the degree of state involvement. The main part of this paper uses cases from the APEC/CBPR and EU/GDPR as models for exploration and to demonstrate the fluidity of interactions across public and private governance realms. The final part points out the gap between private actors’ potential governing functions and their current roles in privacy protection regimes.

2. Privacy Paradigm in Flux: Calling for Innovative Approaches

2.1. In Defense of Big Data

Big data analytics has intensified the dysfunction of the privacy informed-consent regime. In the age of big data, even well-informed and duly diligent individuals may not be able to meaningfully control their data usage. First, privacy policies are growing longer and becoming “blank” in response to the potential of big data analytics. Service providers tend to craft policy statements that cover every possible future use and reserve the maximum space for data aggregation. Written privacy policies that contain information regarding how service providers collect and share data with each other are too vague to represent meaningful notice.12 Blank consent that allows for an unlimited array of data aggregation is socially undesirable.13 After all, how can we meaningfully consent to the use the raw data if the fruit of the analysis remains a mystery?

Indeed, the aggregation of personal data over a period of time by different service providers has brought privacy risks to a new level. Privacy harms might result from cumulative and holistic data usage. To illustrate, an individual consents to Service Provider A’s use of his/her non-sensitive data at one point in time and reveals other equally non-sensitive data to Service Provider B and Service Provider C at later points in time. Service Provider A, which has access to multiple sources of this individual’s partial personal information, may be able to effectively piece data together (from Service Provider B and Service Provider C) to analyze and profile sensitive facts about this individual. Considering such an aggregation effect, managing personal data in every isolated transaction with separate service providers is no longer an effective way to prevent privacy harms which may be the result of cumulative and holistic data usage.14

On the other hand, privacy self-management based on informed consent may constitute an unnecessary barrier to the potential use of data that could promote public interests and social values.15 In the big data ecosystem, it is difficult for service providers, when providing services, to predict how the collected data might be aggregated in the future. As for the innovation sectors, a privacy regime that requires informed consent before data collection reflects an outdated technological landscape. Innovations in data aggregation and analysis are rapidly being introduced, a fact which may not be apparent when the data is collected.16 To a certain extent, the benefits of innovative and unexpectedly powerful uses of data enabled by big data analytics are defeated by the informed consent system. After all, big data drives social benefits, from public infrastructure to medical innovations. Commentators therefore argue that the timing of consent should be more heavily focused on downstream uses rather than on the time of the data collection.17 Indeed, consent surrounding the time of data collection might serve as a de facto prohibition on potential big data applications.

2.2. Possible Roles of Private Actors

This paper aims to address the possible roles of private actors when privacy paradigms are in flux, especially from the viewpoint of the ineffectiveness of the notice-and-consent process. How can private sector actors contribute to privacy governance? If the traditional “informed-consent”-based government-dominated approaches are ill-suited to the big data ecosystem, can private governance fill the gap created by state regulation? What about a hybrid governing framework in which the public and private sectors work together to reshape the landscape of the data protection regime?

First, as this paper explores in the next section, privacy certifications operated by the private sector have been developed to vouch for a service provider’s compliance with certain privacy standards.18 Over the past two decades, although notable attempts at privacy certification have not been popularly adopted on a global scale, certification has been gradually incorporated into the privacy practices of many transnational corporations.19 Have such attempts effectively complemented state regulations? The case studies in Section 3 of this paper discuss the role of third-party privacy certification in existing legal frameworks.

Second, innovative approaches have been proposed to enhance the role of private actors in privacy governance. Policymakers contend that the fundamental problem with the informed consent system is that it places a heavy burden of privacy protection on consumers.20 To address the “non-level playing field in the implicit privacy negotiation between provider and user”,21 substitutes for informed consent have been proposed to ensure that individuals have meaningful choices in managing their personal data. One such direction is to empower individuals to “negotiate” with service providers with the assistance of a mutually accepted intermediary.22 It is necessary to create a new mechanism under which individuals can “delegate” their privacy preferences to a private actor they trust, such as an App store, industry organization, or private association.23 Such a private actor would negotiate on behalf of consumers with other providers of similar services for a preferred level of privacy protection. In other words, individuals would delegate, on a commercial or non-commercial basis, the management of their personal data to a third party who would then carefully read the service provider’s privacy “offer”, ensure that the privacy statement is sufficiently clear, negotiate the terms, formulate a meaningful consent to “accept” the transaction, and investigate the service provider’s privacy practices. Ideally, such a third-party service would create a “privacy watchdog” marketplace for privacy negotiation and management.24 Under the intermediation of these third parties, which represent critical masses of consumers, the problems with the informed consent system can largely be solved. In such a marketplace, the third party would negotiate on behalf of its clients with service providers, including Big Tech, to adjust their offerings. Individuals would be able to withdraw and delegate the work to different private actors in the market.25

Finally, from the angle of industry-specific techniques, privacy protection in the context of big data requires a third party to carry out de-identification and re-identification tests. De-identification is an increasingly central technique that is being used for big data applications.26 However, as the amount and sources of data grow, the likelihood of individuals being re-identified is increasing. As previously illustrated, non-sensitive data might be re-associated into sensitive data or become identifiable information. Nonetheless, privacy regulations are generally technology-neutral legislation in that the law itself does not specify de-identification procedures and techniques. For example, the Recital of GDPR stipulates that “in order to determine whether a natural person is identifiable”, consideration should be given to “all the means reasonably likely to be used”.27 In this regard, “all objective factors” should be taken into account to evaluate whether certain means are likely to be used to identify individuals, including “the amount of time required for identification, the available technology at the time of processing, and future technological developments”.28 Therefore, how to de-identify a particular segment of data in a particular context and how to better manage the risk of anonymized data being used to identify a natural person require sectoral technical standards.29 Private actors, such as a certification body or industry association with the necessary technical expertise, can carry out de-identification assessments, apply state-of-the-art technology to maintain anonymization, and reduce the risk of re-identification.

3. Typologies: Public–Private Interactions

3.1. Collaboration and Coordination

Private actors are playing an increasingly important role in global governance alongside state regulations. Private and public authority dynamics emerge in complex ways, and various efforts have been devoted to classifying them into types, namely, the complementary type and competition type.30 In the context of privacy governance, to what extent is private governance filling the gaps in state regulations? To answer this question, it is important to identify how public authority and the private sector can simultaneously shape global privacy norms as well as which type of public–private partnership (PPP) model is best suited for data governance in light of technological uncertainty. In reality, how is PPP being implemented in the privacy protection frameworks?

As Cashore et al. point out in their recent work, the middle ground between complementary and competitive should be identified in order to capture complex PPP. Cashore et al. contend that the conceptualization of public policy and private authority as either complementary or competitive might be an oversimplified approach. They suggest that we should move beyond this dichotomy and map “a fuller suite of mechanisms through which public and private governance interact”.31 To this end, they have created more detailed sub-types of public–private interaction.32 In their view, “collaboration” and “coordination” are the main forms within complementary-type PPP. Collaboration is an active partnership which is built upon effective communications. This type of PPP works better if both parties are on equal footing, that is, there is no clear hierarchy between them. Conceptually different from collaboration, coordination refers to the “delegation” of political authority to private actors, which in most cases involves hierarchy.33 In addition, Cashore et al. stress that the main sub-type within competition-type PPP is “substitution”, which generally describes the substitution effects of private governance.34 In other words, private actors intend to displace state regulation by industry self-regulation, such as a Code of Conduct (CoC). The cybersecurity co-regulatory model can be a good example in this context. Significant roles have been attached to the third-party certification mechanisms in cybersecurity governance. The National Institute for Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework (hereinafter “The NIST Framework”), for instance, serves as a platform for the public and private sectors to work together. According to its mission statement, the NIST’s Cybersecurity for the Internet of Things (IoT) Program aims to “supports the development and application of standards … to improve the cybersecurity of connected devices…by collaborating with stakeholders across government, industry, international bodies, academia, and consumers”.35 Such an approach to PPP represents a compromise between public regulatory interference and private regulation which falls within the category of “collaboration”, if not “substitution”.

With respect to privacy governance, the public and private sectors can either “collaborate” or “coordinate” on governance, both falling in the center of the public versus private continuum. On one end of the continuum is top-down, government-dominated, command-and-control state regulation, and on the other end is bottom-up, voluntary-based self-regulation. Collaborative and coordinative governance, each with a different proportion of private governance, are hybrid approaches that rely on both governmental enforcement power and private participation. Depending on the degree of state involvement, the public and the private sectors collaborate or coordinate in privacy governance. Under the form of collaborative governance,36 the state works hand in hand with the private sector, remains involved as a dynamic facilitator to “nudge” private sector participation, and uses a traditional enforcement mechanism such as a penalty only when necessary to complement the governance framework. Under the form of coordinative governance, on the other hand, the government delegates oversight to private actors.37 Traditional command-and-control remains the backup authority driving the governance structure.38

3.2. Substitution

Finally, under the form of “substitutive” governance, private efforts such as industry self-regulation may in certain situations “preempt” state regulations.39 In these cases, private governance can substitute for public regulation. Commentators have even pointed out that the private authority can assume a “competitive role” in which it competes directly with and even attempts to replace the government standards.40

In this context, a particularly important angle is whether private privacy norms are alternatives to state regulations under international economic law. Are private certifications “less trade-restrictive measures” to “hardish” state privacy laws? At the multilateral level, several WTO provisions that provide an exception to justify public policies require that the state regulation in dispute be the least “trade restrictive means” of contributing to the desired policy objectives. Article 2.2 of the Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement (TBT Agreement), for example, requires that technical regulations, arguably including privacy standards,41 not be “more trade restrictive than necessary to fulfil a legitimate objective”. In another example, WTO jurisprudence makes it clear that whether a data-restrictive state regulation is necessary for its public policy objectives, arguably under GATS Article XIV(a) or Article XIV(c)(ii) general exceptions provisions, includes the consideration of “less trade restrictive” alternatives for contributing to that objective. The Appellate Body has repeatedly stated that the “necessity test” requires the consideration of alternatives to the measure at issue so as to determine whether existing options are “less trade restrictive” while “providing an equivalent contribution to the achievement of the objective pursued”.42

At the regional level, the analysis of alternatives is a key component of the exceptions in the Electronic Commerce/Digital Trade Chapters of free trade agreements. For example, Article 14.11 of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), “Cross-Border Transfer of Information by Electronic Means”, requires parties to “allow the cross-border transfer of information by electronic means, including personal information, when this activity is for the conduct of the business of a covered person”. The same article, however, allows a party to deviate from the rules to achieve a legitimate public policy objective provided that the measure “does not impose restrictions on transfers of information greater than are required to achieve the objective”. Therefore, a trade tribunal must consider whether alternative, less trade-restrictive measures proposed by the complaining party are reasonably available and can achieve the desired policy goal of the responding party.

Here, a complaining party might argue that an anonymization certification granted by a trusted private body or other credible industry self-regulation associations is a less trade-restrictive alternative to data-restrictive measures. A complaining party might propose self-certification programs as feasible and less trade-restrictive alternatives.43 The responding party, on the other hand, may argue that private governance cannot achieve the equivalent level of protection that state regulation achieves.44 Do private actors directly compete or displace state regulation in the realm of privacy governance? Can private privacy norms constitute “less trade restrictive alternative measures” in a trade dispute? How the tribunal determines such an issue will depend on the public–private interactions in a particular privacy governance regime.

4. Case Studies: The Public and Private Sectors in Privacy Governance

4.1. APEC/CBPR: Moving from Self-Regulation to “Collaboration”?

This paper uses cases from the APEC’s Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as models for exploration. The APEC CBPR system is a self-regulatory initiative designed to facilitate cross-border data flow while protecting consumer data privacy. To be brief, CBPR is a certification system of privacy protection that service providers can participate in to demonstrate compliance with privacy “principles” reflected in the APEC Privacy Framework (hereinafter “Privacy Framework”).45 The Privacy Framework, as the title indicates, establishes the minimum standards for privacy protection. Led by the United States as preferable to the EU approach to data protection, it is not surprising that the CBPR system is now recognized in the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) as “a valid mechanism to facilitate cross-border information transfers while protecting personal information”.46 There are currently nine participating countries in the CBPR, each of which are at different stages of implementing the CBPR System.47

Essentially, the CBPR is a voluntary-based scheme that requires acceptance at the state level followed by certification of the service providers wishing to be part of the system.48 Indeed, the key component of the CBPR is that third parties are to inspect and certify the privacy practices of the service providers against the APEC Framework and to manage privacy-related dispute resolution for certified service providers. A service provider applying to join the CBPR must establish its privacy statement and practices to be consistent with either the basic standards in the Privacy Framework or domestic regulation. Following assessment, service providers certified by an APEC-recognized Accountability Agent may display a seal, a trust mark, or otherwise claim to qualify under the CBPR System.49 To maintain the system in operation, the APEC economies should select and endorse the “accountability agents” who certify the privacy practices of service providers that wish to join the scheme. Currently, there are nine APEC-recognized accountability agents: TrustArc (US), Schellman (US), BBB National Program (US), HITRUST (US), NCC Group (US), JIPDEC (Japan), IMDA (Singapore), KISA (Korea) and III (Taiwan).50 In practice, accountability agents such as Schellman and Company in the US typically provide certification services in accordance with APEC privacy standards. Schellman and Company, for example, perform testing to evidence the certification’s minimum requirements. The testing procedures include inquiry into the relevant personnel of service providers wishing to join the CBPR, observation of the relevant process, and the inspection of relevant records.51 In addition, certified service providers are monitored throughout the certification period, including periodic reviews of the service provider’s privacy policies, to ensure compliance with the APEC Privacy Framework. In this regard, annual re-certification is required in order to update the CBPR Questionnaire. Certification is suspended if a certified service provider is found to have violated the CBPR requirements and if such a breach has not been resolved within certain time frames.52

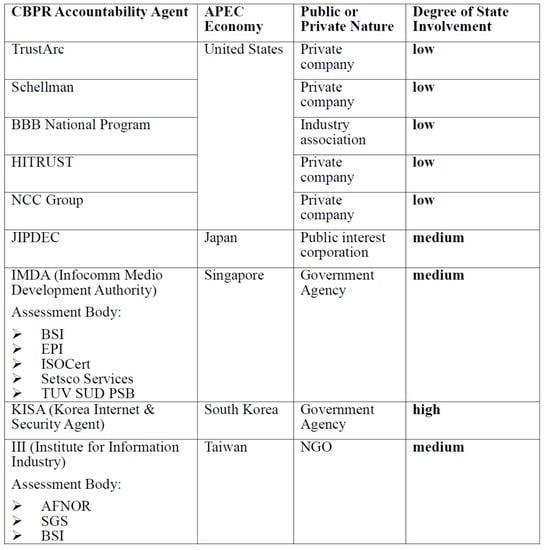

In the context of PPP, several angles deserve further exploration. First, in terms of the nature of the “Accountability Agents”, Figure 1 features a hybrid system of public and private organizations. While the five US-based accountability agents have private characteristics, other Asia-based agents are either government agencies or government-affiliated organizations. The Internet and Security Agency (KSIA) is the South Korean Ministry of Science and ICT’s sub-organization;53 the Japan Institute for Promotion of Digital Economy and Community (JIPDEC) is a public-interest corporation in Japan, which has long been in close cooperation with Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry;54 and Singapore’s ICT regulator—the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA)—is a statutory board under the Singapore Ministry of Communications and Information. When appointing an assessment body such as the BSI Group to determine whether a service provider’s data protection practices conform to the CBPR requirements, the IMDA remains the Accountability Body under the Privacy Framework, and the certification application fee is payable to the IMDA.55 The Institute for Information Industry (III) in Taiwan is a non-governmental organization which has long acted as an ICT “Think Tank” for the government.56 Evidently, the degree of state involvement is more than nominal.

Figure 1.

CBPR Accountability Agents.

Another angle worth noting with regard to public–private interactions under the CBPR regime is the role of governmental enforcement authorities. The CBPR, by its very nature, is an instrument of self-regulation. The main deficiency that hampers its overall effectiveness is the lack of sufficient governmental guidance and supervision. Nevertheless, there are encouraging stories demonstrating that national regulators may sometimes act as “privacy cops” to sustain the integrity of the CBPR system. One striking example is the US Fair Trade Commission (FTC), which in 2014 fined TRUSTe (now TrustArc) for failing to promote timely re-certification of the participating companies on an annual basis, which violates its own certification policy.57 Another example involves the FTC, which in 2016 alleged Vipvape’s practice of deception in its privacy statement. Vipvape had falsely advertised that it was a certified participant in the CBPR scheme, which it was not. The bilateral settlement between the FTC and Vipvape bans Vipvape from misleading the public about its certification status under the Privacy Framework. According to the FTC, “the governmental oversight and enforceability of the CBPR are mandated by the terms of the system itself”.58

Nevertheless, public enforcement under the CBPR remains limited. The low degree of state involvement has resulted in a lack of accountability. For consumers, there is no strong incentive to seek out those service providers that are CBPR certified. In turn, there are weak incentives for service providers to invest in and obtain a CBPR certification. To conclude, the CBPR system falls between “collaborative governance” and “self-regulation” on the public versus private spectrum. In moving towards an accountable and collaborative form of governance, the future success of the CBPR depends on whether systemic and aggregate accountability over public–public interactions can be established.59 Such accountability requires a higher degree of state involvement and, in particular, requires national regulators to act as “privacy cops”.

4.2. EU/GDPR: Moving from State Regulation to “Coordination”?

The GDPR, on the other hand, is fundamentally of a “hard law” nature, and is backed by enforcement penalties.60 Nonetheless, the regime seems to include room for PPP in allowing private actors to complete the details of how to comply with the legal requirements through the CoC or certification mechanisms. Both the CoC and certification require an independent third-party body to assess conformity with the normative documents and require the assessor to be accredited. In addition, both the approved CoC and certification are recognized by the GDPR as factors when national regulators assess penalties for non-compliance. Furthermore, both CoC and certification, if coupled with binding and enforceable commitments to apply appropriate safeguards, can be used by controllers and processors in third countries as a legitimate basis for cross-border transfers of data.61

With respect to the CoC, associations or “other bodies representing categories of controllers or processors” are encouraged to draw up sector-specific CoCs to “facilitate the effective application” of the GDPR.62 The CoC may cover many aspects of the GDPR, such as “the pseudonymization of personal data” and “the transfer of personal data to third countries”.63 Wherever feasible, associations should consult stakeholders when preparing the CoC.64 The monitoring of compliance with the CoC may be carried out by a body, including a private body, which is accredited by the national regulator.65 Each regulator should “draft and publish the criteria for accreditation of a body for monitoring codes of conduct”.66 An accredited CoC monitoring body should “take appropriate action”, for example, to suspend the controller or processor “in cases of infringement of the code by a controller or processor”. A monitoring body should also report such actions to the regulator.67 It should be noted that such “action” of the accredited CoC monitoring body does not take the place of possible actions that can otherwise be activated by the authorities for non-compliance. Finally, for service providers, “adherence to approved codes of conduct” is an element for data controllers to demonstrate compliance with the GDPR obligations,68 and is a factor when the regulator determines whether to impose an administrative fine, as well as the amount of the fine.69

With respect to certification, the GDPR expressly recognizes certification and data protection seals and/or marks as a mechanisms of demonstrating compliance and enhancing transparency.70 Certifications may be issued by either the European Data Protection Board, a national regulator, or a private third party that is an accredited certification body.71 The certification bodies should conduct a “proper assessment leading to the certification”, or the withdrawal of certification in the case of non-compliance.72 The certification body should inform the regulator and provide reasons for granting or withdrawing certification. More importantly, a certification does not “reduce the responsibility of the controller or the processor for compliance with this Regulation”.73 National regulators have the investigative powers to “order the certification body not to issue certification” when the requirements for the certification are not met. National regulators retain the power to withdraw a certification or to order the certification body to withdraw a certification “if the requirements for the certification are no longer met”.74 Finally, similar to the CoC, adherence to approved certification mechanisms is a key factor to consider when regulators impose administrative fines on certified service providers for non-compliance.75

At the crux of the matter is whether the GDPR relies on PPP in governing data. Can the CoC and certification systems work better in coordinative-type PPP? To what extent do EU member states delegate authority to private actors in terms of governance? Obviously, there is a hierarchical relationship between public and private actors in the GDPR framework. National regulators are entitled to approve or disapprove the certification requirements. Arguably, the accredited private bodies’ certifying power is conditional,76 as the certification can be withdrawn at any time by the regulator if the conditions of issuance are no longer met. Overall, the CoC and certification mechanisms under the GDPR remain in a top-down, command-and-control arrangement.

Moreover, the GDPR has serious “teeth” with regard to an accredited private body’s obligations. Infringements on the obligations of the CoC’s monitoring body or the certification body are subject to administrative fines of up to EUR 10,000,000 or up to 2% of the “total worldwide annual turnover of the preceding financial year”, whichever is higher.77 This results in weak incentives for private actors to actively participate in the governing scheme.

Additionally, the role of a private certification body is further weakened by the GDPR certification’s lack of presumption of conformity. GDPR certifications are not considered as offering a “presumption of conformity” with the obligations under the GDPR.78 In other words, the assessment by the certification body that processing is in line with the certification criteria merely grants a “stamp of approval” for the accountability of the certified service provider. The presence of such accountability, however, does not “reverse the burden of proof”, and it does not provide “presumed compliance” with the GDPR.79 In summary, GDPR certification does not prima facie entail full compliance with the GDPR. It does not act as a safe harbor from GDPR enforcement, nor does it provide the benefit of reduced regulatory scrutiny.80 In conclusion, the CoC and the certification systems rely too heavily on public governance and invoke private governance at a minimal level. The GDPR-type public–private “coordination” risks being too command-and-control minded.81

5. Conclusions: The Future of Public–Private Convergence

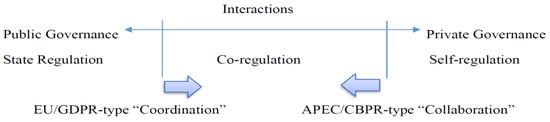

The above analysis demonstrates the fluidity of interactions across the public and private governance realms. As shown in Figure 2, self-regulation and state regulation are opposing ends of a regulatory continuum, with CBPR-type “collaboration” (moving from self-regulation to collaborative governance) and GDPR-type “coordination” (moving from state regulation to coordinative governance) falling somewhere in the middle.

Figure 2.

Public–Private Convergence in Privacy Governance.

The author raises the following questions at the outset of this paper: If the traditional informed-consent based and government-dominated approaches are ill-suited to the big data ecosystem, can private governance fill the gap created by state regulation? This paper explores the issues of how private actors can play more important roles when privacy paradigms are in flux. After assessing whether PPP is now being implemented in privacy protection, the author concludes that there is an evident gap between private actors’ potential governing functions, as described in Section 2 of this paper, and their current roles in privacy protection regimes, as examined in Section 4. Looking to the future, technological developments and market changes call for further public–private convergence in privacy governance, allowing the public authority and the private sector to simultaneously reshape global privacy norms.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Yi-hsuan Chen for her excellent research assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Cashore, Benjamin, Jette Steen Knudsen, Jeremy Moon, and Hamish van der Ven. 2021. Private Authority and Public Policy Interactions in Global Context: Governance Spheres for Problem Solving. Regulation & Governance 15: 1166–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, McKay. 2014. Next Generation Privacy: The Internet of Things, Data Exhaust, and Reforming Regulation by Risk of Harm. Groningen Journal of International Law 2: 115–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hintze, Mike. 2017. In Defense of the Long Privacy Statement. Maryland Law Review 76: 1044. [Google Scholar]

- Kamara, Irene. 2017. Co-Regulation in EU Personal Data Protection: The Case of Technical Standards and the Privacy by Design Standardization “Mandate”. European Journal of Law and Technology 8: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kamara, Irene. 2020. Misaligned Union Laws? A comparative Analysis of Certification in the Cybersecurity Act and the General Data Protection Regulation. In Privacy and Data Protection: Artificial Intelligence. Edited by Dara Hallinan, Ronald Leenes and Paul Hert. London: Hart Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, Margot E. 2019. Binary Governance: Lessons from the GDPR’s Approach to Algorithmic Accountability. Southern California Law Review 92: 1529–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanetake, Machiko, and André Nollkaemper. 2014. The Application of Informal International Instruments Before Domestic Courts. The George Washington International Law Review 46: 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lachaud, Eric. 2020. What GDPR Tells about Certification. Computer Law and Security Review 38: 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, Sergio. 2020. How Facial Recognition Will Change Retail, Forbes. May 8. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2020/05/08/how-facial-recognition-will-change-retail/?sh=13abb5563daa (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Mitchell, Andrew D., and Neha Mishra. 2019. Regulating Cross-Border Data Flows in a Data-Driven World: How WTO Law Can Contribute. Journal of International Economic Law 22: 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundie, Craig. 2014. Privacy Pragmatism: Focus on Data Use, Not Data Collection. Foreign Affairs 93: 28. [Google Scholar]

- Reidenberg, Joel R., N. Cameron Russell, Vlad Herta, William Sierra-Rocafort, and Thomas B. Norton. 2019. Trustworthy Privacy Indicators: Grades, Labels, Certifications, and Dashboards. Washington University Law Review 96: 1409–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rothchild, John A. 2018. Against Notice and Choice: The Manifest Failure of the Proceduralist Paradigm to Protect Privacy Online (Or Anywhere Else). Cleveland State Law Review 66: 559. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, Ira S. 2018. The Future of Self-Regulation Is Co-Regulation. In Consumer Privacy. Edited by Evan Selinger, Jules Polonetsky and Omer Tene. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 503. [Google Scholar]

- Solove, Daniel J. 2013. Privacy Self-Management and The Consent Dilemma. Harvard Law Review 126: 1879. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Clare. 2019. EU GDPR or APEC CBPR? A Comparative Analysis of the Approach of The EU and APEC to Cross Border Data Transfers and Protection of Personal Data in the IoT Era. Computer Law & Security Review 35: 380–97. [Google Scholar]

- United States President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST). 2014. Executive Office of the President, Report to the President, Big Data and Privacy: A Technological Perspective; Hereinafter “the PCAST Report”. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the U.S. President, May.

- Weber, Rolf H. 2021. Global Law in Face of Datafication and Artificial Intelligence. In Artificial Intelligence and International Economic Law. Edited by Shin-yi Peng, Ching-Fu Lin and Thomas Steinz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for A Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See generally Solove (2013). |

| 2 | See e.g., Reidenberg et al. (2019). See also United States President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) (2014). Cf., Hintze (2017). |

| 3 | Hintze, ibid, p. 1045. |

| 4 | Rothchild (2018), p. 647. |

| 5 | See generally Weber (2021). |

| 6 | Cunningham (2014). |

| 7 | See, e.g., Mannino (2020). |

| 8 | See generally Zuboff (2019). |

| 9 | Reidenberg et al., supra footnote 2, p. 1412. |

| 10 | Twitter Privacy Policy, available online: https://cdn.cms-twdigitalassets.com/content/dam/legal-twitter/site-assets/privacy-aug-19th-2021/Twitter_Privacy_Policy_EN.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 11 | Cunningham, supra footnote 6. |

| 12 | See, e.g., the WhatsApp Privacy Policy, which states “[…] As part of the Facebook Companies, WhatsApp receives information from, and shares information with, the other Facebook Companies. We may use the information we receive from them, and they may use the information we share with them, to help operate, provide, improve, understand, customize, support, and market our Services and their offerings […]”, available online: https://www.whatsapp.com/legal/privacy-policy/?lang=en (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 13 | Solove, supra footnote 1, p. 1881. |

| 14 | Ibid. |

| 15 | Ibid., p. 1889. |

| 16 | Ibid., p. 1895. |

| 17 | Ibid. |

| 18 | Reidenberg et al., supra note 2, p. 1413. |

| 19 | Ibid., p. 1412. |

| 20 | The PCAST Report, supra note 2, p. 38. |

| 21 | Ibid. |

| 22 | Ibid. |

| 23 | See generally Mundie (2014). |

| 24 | Ibid., p. 4. |

| 25 | The PCAST Report, supra footnote 2, p. 38. |

| 26 | See, e.g., Guidance Regarding Methods for De-identification of Protected Health Information in Accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, available online: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/special-topics/de-identification/index.html (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 27 | Recital 26: Not Applicable to Anonymous Data, available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/recitals/no-26/ (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 28 | Ibid. |

| 29 | Kamara (2017). |

| 30 | See, e.g., Kaminski (2019). |

| 31 | See Cashore et al. (2021). |

| 32 | Ibid. First, under the category of complement, Benjamin Cashore et al. further divide the group into “collaboration”, “coordination”, and “isomorphism”. Second, under the category of competition, they further distinguish the types into “substitution” and “cooptation”. Third, they introduce a third main conceptualization, “coexistence”, which contains two sub-types: “layered institutions” and “chaos”. |

| 33 | Ibid., p. 1172. |

| 34 | Ibid. |

| 35 | National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce, NIST Cybersecurity for IoT Program, available online: https://www.nist.gov/itl/applied-cybersecurity/nist-cybersecurity-iot-program (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 36 | Kaminski, supra footnote 30, at 1561–1563. |

| 37 | Ibid., at 1563, 1596. |

| 38 | Ibid., at 1562–1564. |

| 39 | Benjamin Cashore et al., supra footnote 31, at 1172. |

| 40 | Ibid. |

| 41 | The list of exemplary legitimate objectives in TBT Article 2.2 is non-exhaustive. |

| 42 | See, e.g., Appellate Body Report, European Communities—Measures Prohibiting the Importation and Marketing of Seal Products (EC – Seal Products), WT/DS400/AB/R, WT/DS401/AB/R, 18 June 2014, paras. 5.260–5.264. |

| 43 | On 25 March 2022, the US and the EU jointly announced an “agreement in principle” to new Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework. Similar to its predecessors, the Privacy Shield and Safe Harbor provisions, the new Framework requires companies to self-certify their adherence to the Principles through the U.S. Department of Commerce. See the Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework, available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/FS_22_2100 (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 44 | See Mitchell and Mishra (2019). |

| 45 | APEC, APEC Privacy Framework, available online: https://www.apec.org/publications/2017/08/apec-privacy-framework-(2015) (accessed on 8 October 2022). See also APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules System, available online: https://www.apec.org/publications/2020/02/apec-cross-border-privacy-rules-system-fostering-accountability-agent-participation (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 46 | USMCA, Article 19.8: Personal Information Protection: “6. Recognizing that the Parties may take different legal approaches to protecting personal information, each Party should encourage the development of mechanisms to promote compatibility between these different regimes. The Parties shall endeavor to exchange information on the mechanisms applied in their jurisdictions and explore ways to extend these or other suitable arrangements to promote compatibility between them. The Parties recognize that the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules system is a valid mechanism to facilitate cross-border information transfers while protecting personal information”. |

| 47 | Australia, Canada, Chinese Taipei, Japan, Republic of Korea, Mexico, the Philippines, Singapore and the United States. |

| 48 | APEC, What is the Cross-Border Privacy Rules System, available online: http://www.cbprs.org/ (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 49 | APEC CBPR, available online: http://cbprs.org/business/ (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 50 | Ibid. |

| 51 | Schellman and Company, APEC Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) Certification Process and Minimum Requirements, available online: https://www.schellman.com/apec/cbpr-process (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 52 | Ibid. |

| 53 | The Internet and Security Agency (KSIA), available online: https://www.kisa.or.kr/eng/main.jsp (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 54 | The Japan Institute for Promotion of Digital Economy and Community (JIPDEC), available online: https://english.jipdec.or.jp/ (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 55 | The Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), available online: https://www.imda.gov.sg/regulations-and-licensing-listing/ict-standards-and-quality-of-service/IT-Standards-and-Frameworks/Compliance-and-Certification (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 56 | The Institute for Information Industry (III), available online: https://www.tpipas.org.tw/ (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 57 | To date, the FTC has brought four actions to enforce companies’ promises under APEC CBPR. See FTC Report to Congress on Privacy and Security (13 September 2021), available online: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/ftc-report-congress-privacy-security/report_to_congress_on_privacy_and_data_security_2021.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 58 | “Good news” for the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules: FTC settles with Vipvape on CBPR privacy policy deception. Data Protection Law and Policy (June 2016) https://www.informationpolicycentre.com/uploads/5/7/1/0/57104281/good_news_for_the_apec_cross-border_privacy_rules_dplp_-_june_2016.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022). |

| 59 | Kaminski, supra footnote 30, pp. 1568–80. See generally Rubinstein (2018). |

| 60 | Kaminski, id., p. 1611. |

| 61 | See generally Lachaud (2020). See also Sullivan (2019). |

| 62 | GDPR Recital 98. |

| 63 | GDPR Article 40 |

| 64 | GDPR Recital 99. |

| 65 | GDPR Article 41. |

| 66 | GDPR Article 57. |

| 67 | GDPR Article 41. |

| 68 | GDPR Article 24. |

| 69 | GDPR Article 83. |

| 70 | GDPR Recital 100. |

| 71 | GDPR Article 42. |

| 72 | GDPR Article 43. |

| 73 | GDPR Article 42. |

| 74 | GDPR Article 58. |

| 75 | GDPR Article 83. |

| 76 | Lachaud, supra note 61. |

| 77 | GDPR Article 83. |

| 78 | See Kamara (2020). |

| 79 | Cf, Lachaud, supra footnote 61, p. 7. |

| 80 | See also Kanetake and Nollkaemper (2014). |

| 81 | Kaminski, supra footnote 30, pp. 1599–601. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).