Implementation of Good Practices in Environmental Licensing Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

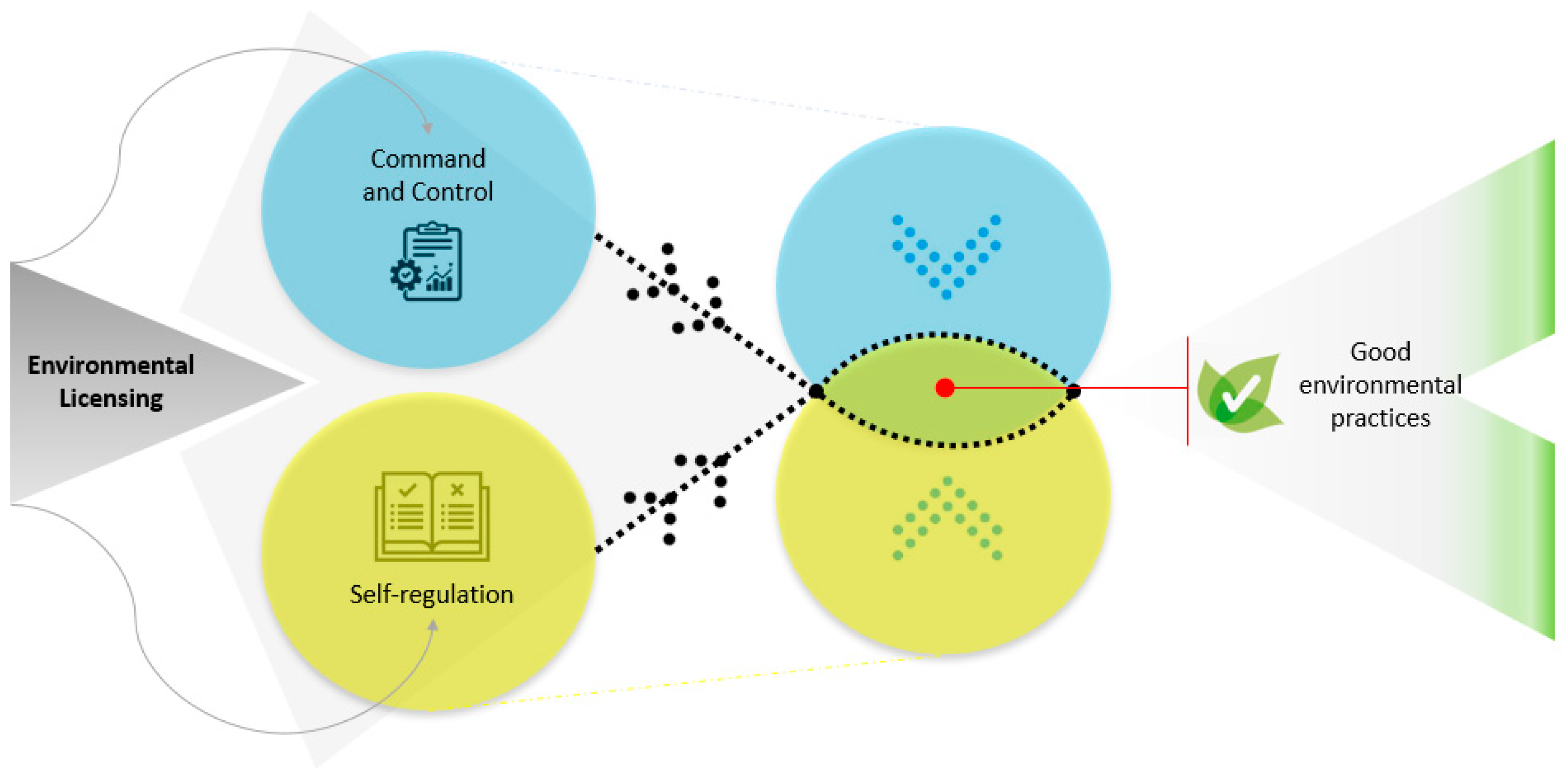

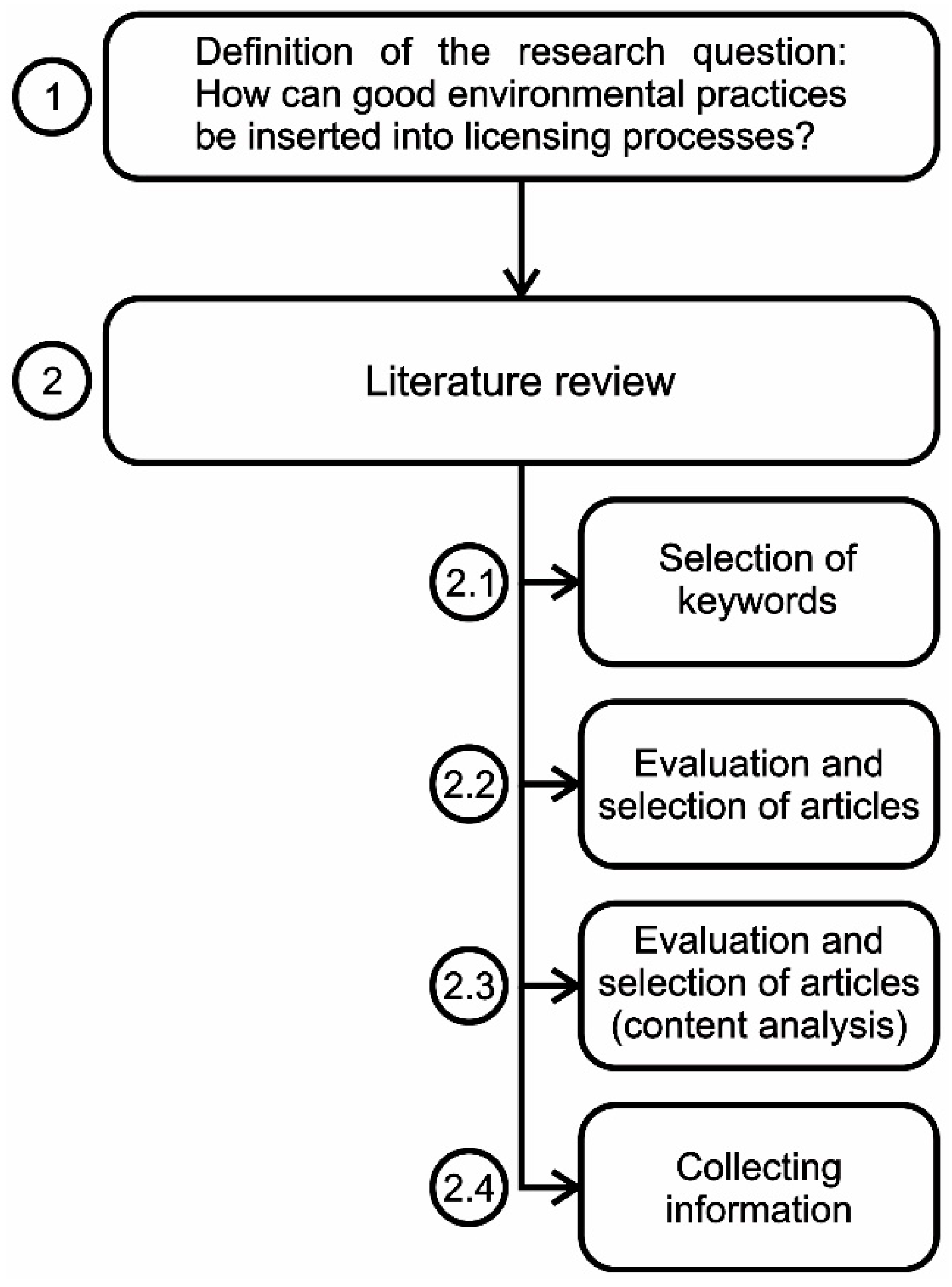

2. Research Method

2.1. Methodological Design and Data Collection

2.2. Study Limitation

3. Findings

3.1. Brazil

- Concession of licenses with extended terms: longer terms for environmental licenses from companies that adopt good environmental practices would allow the entrepreneur to spend less on administrative processes and greater savings in financial resources;

- Reducing bureaucracy (with time gain) of administrative procedures: the excess of documents requested can, in many cases, bring difficulties for the environmental regularization of companies. Thus, it was suggested to review the list of documents required in the case of projects that have had demonstrably good environmental performance;

- Exemption or reduction of fees: the reduction or even withdrawal of fees charged by environmental licensing institutes could encourage entrepreneurs to adopt good environmental practices in their businesses;

- Periodic disclosure of a list of organizations that adopt good practices: considering that environmental practices is a great differential for consumers today, it is suggested that environmental institutes give recognition to companies that adopt good environmental practices.

- Facilitation of financing (applicable to financial institutions): financial agents can encourage the adoption of good environmental practices by establishing differentiated and more attractive values for projects that have proven good environmental performance.

3.2. Chile

3.3. Colombia

3.4. Peru

- The assessment of environmental performance of activities is carried out through compliance with the conditions established in the license;

- The inspections carried out by technicians of the licensing agency in the organizations consider the processes of control and maintenance of environmental records; the adoption of preventive and corrective measures; and awareness programs and employee training;

- The country’s environmental agency has a positive view on including ways to encourage the adoption of good environmental practices in the stages of environmental licensing;

- They are evaluating possible incentives for organizations that have international environmental management certificates.

3.5. Portugal

3.6. Uruguay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Further Reflections

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

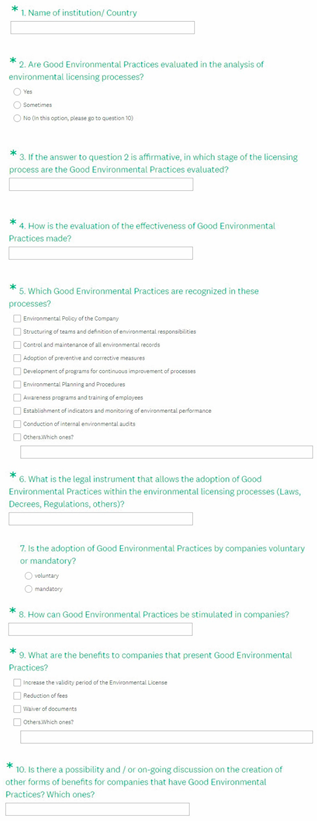

Appendix A

References

- Adams, William C. 2015. Conducting semi-structured interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, 4th ed. Edited by Kathryn E. Newcomer, Harry P. Hatry and Joseph S. Wholey. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agee, Jane. 2009. Developing qualitative research questions: A reflective process. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 22: 431–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athayde, Simone, Alberto Fonseca, Suely. M. V. G. Araújo, Amarilis L. C. F. Gallardo, Evandro M. Moretto, and Luis E. Sánchez. 2022. The far-reaching dangers of rolling back environmental licensing and impact assessment legislation in Brazil. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 94: 106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, Eugene. 2009. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: CQ Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, Alan, Jenny Pope, Angus Morrison-Saunders, Francois Retief, and Jill A. E. Gunn. 2014. Impact assessment: Eroding benefits through streamlining? Environmental Impact Assessment Review 45: 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, Alan, Thomas B. Fischer, and Josh Fothergill. 2017. Progressing quality control in environmental impact assessment beyond legislative compliance: An evaluation of the IEMA EIA Quality Mark certification scheme. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 63: 160–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borioni, Rossana, Amarilis Lucia Casteli Figueiredo Gallardo, and Luis Enrique Sánchez. 2017. Advancing scoping practice in environmental impact assessment: An examination of the Brazilian federal system. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 35: 200–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragagnolo, Chiara, Clara Carvalho Lemos, Richard J. Ladle, and Angela Pellin. 2017. Streamlining or sidestepping? Political pressure to revise environmental licensing and EIA in Brazil. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 65: 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan. 2012. Social Research Methods, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carmo, Aline Borges do, and Alessando Soares da Silva. 2013. Licenciamento ambiental federal no Brasil: Perspectiva histórica, poder e tomada de decisão em um campo em tensão. Confins 19: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEPAL. 2013. Natural Resources in the Union of South American Nations (UNASUL): Situation and Trends for a Regional Development Agenda; Santiago: United Nations. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/3118 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- CONAMA. 1997. Resolution CONAMA No. 237, of December 19 1997. Available online: http://www2.mma.gov.br/port/conama/legiabre,cfm?codlegi-237 (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Creswell, John W. 2014. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Demirel, Pelin, Konstantinos Iatridis, and Effie Kesidou. 2018. The impact of regulatory complexity upon self-regulation: Evidence from the adoption and certification of environmental management systems. Journal of Environmental Management 207: 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, Carla Grigoletto, Ana Paula Alves Dibo, and Luis Enrique Sánchez. 2017. What does the academic research say about impact assessment and environmental licensing in Brazil? Ambiente e Sociedade 20: 261–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, José Luis, Eduardo L. Qualharini, Daniel R. Nascimento, and Andréa S. C. Fernandes. 2017. Una propuesta de integración entre licenciamiento ambiental y gestión de proyectos en la Ciudad de Río de Janeiro-Brasil. Información Tecnológica 28: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Figueiró, Paola Schmitt, and Emmanuel Raufflet. 2015. Sustainability in higher education: A systematic review with focus on management education. Journal of Cleaner Production 106: 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Alberto, and Larissa Resende. 2016. Boas práticas de transparência, informatização e comunicação social no licenciamento ambiental brasileiro: Uma análise comparada dos websites dos órgãos licenciadores estaduais. Engenharia Sanitária e Ambiental 21: 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Alberto, Luis Enrique Sánches, and José Claudio Junqueira Ribeiro. 2017. Reforming EIA systems: A critical review of proposals in Brazil. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 62: 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Robert B. 2012. In full retreat: The Canadian government’s new environmental assessment law undoes decades of progress. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30: 179–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 1994. Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna Sessions Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, vol. 1, pp. 105–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, Philippe, Frank Vanclay, Esther Jean Langdon, and Jos Arts. 2014. Improving the effectiveness of impact assessment pertaining to Indigenous peoples in the Brazilian environmental licensing procedure. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 46: 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, and et al. 2013. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 342: 850–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, Iñaki, Germán Arana, and Olivier Boiral. 2016. Outcomes of Environmental Management Systems: The Role of Motivations and Firms’ Characteristics. Business Strategy and the Environment 25: 545–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Rose Mirian. 2017. Gargalos do Licenciamento Ambiental Federal no Brasil. In Licenciamento Ambiental e Governança Territorial: Registros e Contribuições do Seminário Internacional; Edited by Marco Aurélio Costa, Letícia Beccalli Klug and Sandra Silva Paulsen. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, vol. 1, pp. 31–41. Available online: https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=30344 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Kalamandeen, Michelle, Emanuel Gloor, Edward Mitchard, Duncan Quincey, Guy Ziv, Dominick Spracklen, Benedict Spracklen, Marcos Adami, Luiz E. O. C. Aragão, and David Galbraith. 2001. Pervasive Rise of Small-scale Deforestation in Amazonia. Scientific Reports 8: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasilingam, R. 2020. Opportunities and Challenges in Green Marketing. Studies in Indian Place Names 1: 3412–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Do-Hyung, Joseph O. Sexton, Praveen Noojipady, Chengquan Huang, Anupam Anand, Saurabh Channan, Min Feng, and John R. Townshend. 2014. Global, Landsat-based forest-cover change from 1990 to 2000. Remote Sensing of Environment 155: 178–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koche, José Carlos. 2011. Fundamentos de Metodologia Científica. Petrópolis: Editora Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- Koro-Ljungberg, Mirka, and Sharon Hayes. 2010. Proposing an Argument for Research Questions That Could Create Permeable Boundaries within Qualitative Research. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research 4: 114–24. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, Maria Luisa Telarolli de A., and Barbara Carvalho Neves. 2019. South American regional integration, infrastructure and the environment: Empty spaces. Aldea Mundo 24: 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Ruiqian, and Ramakrishnan Ramanathan. 2018. Exploring the relationships between different types of environmental regulations and environmental performance: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production 196: 1329–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Zhongju, Yan Liu, and Zhixian Lu. 2022. Market-oriented environmental policies, environmental innovation, and firms’ performance: A grounded theory study and framework. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzetti, Julia Vaz, and Rosinha Machado Carrion. 2012. Governança ambiental global: Atores e cenários. Cadernos Ebape. Br Rio de Janeiro 10: 721–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, Nathalie Barbosa Reis, and Elaine Aparecida da Silva. 2018. Environmental licensing in Brazilian’s crushed stone industries. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 71: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Richard K., Andrew Hart, Claire Freeman, Brian Coutts, David Colwill, and Andrew Hughes. 2012. Practitioners, professional cultures, and perceptions of impact assessment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 32: 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, João Pontes, and Nizar Messari. 2005. International Relations Theory: Currents and Debates. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Rafael Santos de. 2010. Asymmetries in environmental regulation in MERCOSUR: Is legislative harmonization possible between its member states? Âmbito Jurídico. Rio Grande, XIII, n. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Cristina, Camilo M. Botero, Ivan Correa, and Enzo Pranzini. 2018. Seven good practices for the environmental licensing of coastal interventions: Lessons from the Italian, Cuban, Spanish and Colombian regulatory frameworks and insights on coastal processes. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 73: 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, Jenny, Alan Bond, Angus Morrison-Saunders, and Francois Retief. 2013. Advancing the theory and practice of impact assessment: Setting the research agenda. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 41: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Gelze Serrat Souza Campos. 2010. A análise interdisciplinar de processos de licenciamento ambiental no estado de Minas Gerais: Conflitos entre velhos e novos paradigmas. Sociedade & Natureza 22: 267–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Ángeles Pereira, and Xavier Vence Deza. 2015. Environmental policy instruments and eco-innovation: An overview of recent studies. Innovar 25: 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Silva, Marta. 2022. Nudging and Other Behaviourally Based Policies as Enablers for Environmental Sustainability. Laws 11: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Mark, Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill. 2012. Research Methods for Business Students, 6th ed. Nova Jersey: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, Joseph O., Xiao-Peng Song, Min Feng, Praveen Noojipady, Anupam Anand, Chengquan Huang, Do-Hyung Kim, Kathrine M. Collins, Saurabh Channan, Charlene DiMiceli, and et al. 2013. Global, 30-m resolution continuous fields of tree cover: Landsat-based rescaling of MODIS vegetation continuous fields with lidar-based estimates of error. International Journal of Digital Earth 6: 427–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, Missifany, and Mário Diniz Araújo Neto. 2014. Licenciamento ambiental de grandes empreendimentos: Conexão possível entre saúde e meio ambiente. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 19: 3829–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleman-Chams, Juliette, and Carlos Javier Velásquez-Muñoz. 2016. La licencia ambiental: ¿instrumento de comando y control por excepción? Vniversitas 132: 483–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taylor, Christopher M., Elaine A. Gallagher, Simon J. T. Pollard, Sophie A. Rocks, Heather M. Smith, Paul Leinster, and Andrew J. Angus. 2019. Environmental regulation in transition: Policy officials’ views of regulatory instruments and their mapping to environmental risks. Science of the Total Environmental 646: 811–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, Francesco, Olivier Boiral, and Fabio Iraldo. 2018. Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders pressures encourage greenwashing? Journal of Business Ethics 147: 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, Javier, Ignacio Requena, and Montserrat Zamorano. 2010. Environmental impact assessment in Colombia: Critical analysis and proposals for improvement. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 30: 247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townshend, John R., Jeffrey G. Masek, Chengquan Huang, Eric F. Vermote, Feng Gao, Saurabh Channan, Joseph O. Sexton, Min Feng, Raghuram Narasimhan, Dobyung Kim, and et al. 2012. Global characterization and monitoring of forest cover using Landsat data: Opportunities and challenges. International Journal of Digital Earth 5: 373–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. 2003. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2012. How to Decrease Freight Logistics Costs in Brazil, Transport Papers Series. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/348951468230950149/pdf/468850ESW0P101000PUBLIC00TP390Final.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Xie, Rong-hui, YI-jun Yuan, and Jing-jing Huang. 2017. Different Types of Environmental Regulations and Heterogeneous Influence on “Green” Productivity: Evidence from China. Ecological Economics 132: 104–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Bin, and Renjing Xu. 2022. Assessing the role of environmental regulations in improving energy efficiency and reducing CO2 emissions: Evidence from the logistics industry. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 96: 106831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2015. Estudo de Caso: Planejamento e Métodos, 5th ed. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [Google Scholar]

- Zhouri, Andréa, and Raquel Oliveira. 2012. Development and environmental conflicts in Brazil: Challenges for anthropology and anthropologists. Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 9: 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Country | Environmental Agency | Survey Response | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Argentina | Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development | X | |

| Bolivia | Ministry of Environment and Water | X | |

| Brazil | Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resource (IBAMA) | X | |

| Chile | Ministry of Environment | X | |

| Colombia | National Authority for Environmental Licenses | X | |

| Ecuador | Ministry of the Environment | X | |

| Guiana | Department of Environment | X | |

| Paraguay | Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development | X | |

| Peru | Agency for Environmental Assessment and Enforcement | X | |

| Suriname | Ministry of Natural Resources | X | |

| Uruguay | Ministry of Housing, Territorial Planning and Environment | X | |

| Venezuela | Ministry of Popular Power for Ecosocialism | X | |

| Portugal | Portuguese Environment Agency (APA) | X | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Godoi, E.L.; Mendes, T.A.; Batalhão, A.C.S. Implementation of Good Practices in Environmental Licensing Processes. Laws 2022, 11, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11050077

de Godoi EL, Mendes TA, Batalhão ACS. Implementation of Good Practices in Environmental Licensing Processes. Laws. 2022; 11(5):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11050077

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Godoi, Emiliano Lobo, Thiago Augusto Mendes, and André C. S. Batalhão. 2022. "Implementation of Good Practices in Environmental Licensing Processes" Laws 11, no. 5: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11050077

APA Stylede Godoi, E. L., Mendes, T. A., & Batalhão, A. C. S. (2022). Implementation of Good Practices in Environmental Licensing Processes. Laws, 11(5), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11050077