Abstract

Courts are high-stakes environments; thus, the impact of implementing legal technologies is not limited to the people directly using the technologies. However, the existing empirical data is insufficient to navigate and anticipate the acceptance of legal technologies in courts. This study aims to provide evidence for a technology acceptance model in order to understand people’s attitudes towards legal technologies in courts and to specify the potential differences in the attitudes of people with court experience vs. those without it, in the legal profession vs. other, male vs. female, and younger vs. older. A questionnaire was developed, and the results were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Multigroup analyses have confirmed the usefulness of the technology acceptance model (TAM) across age, gender, profession (legal vs. other), and court experience (yes vs. no) groups. Therefore, as in other areas, technology acceptance in courts is primarily related to perceptions of usefulness. Trust emerged as an essential construct, which, in turn, was affected by the perceived risk and knowledge. In addition, the study’s findings prompt us to give more thought to who decides about technologies in courts, as the legal profession, court experience, age, and gender modify different aspects of legal technology acceptance.

Keywords:

legal technology; technology acceptance; trust in technology; courts; court experience; TAM; PLS-SEM 1. Introduction

Technologies promise more accessibility to justice and less complexity (; ), as courts face many issues. For example, Brazil has a staggering backlog of 78 million lawsuits (). A great disruptor of life for the past two years—COVID-19—has also pushed courts to use technologies (), revealing practical issues and the need for simple tools (). Ideally, the decisions on whether to implement technologies in courts would be based mostly on hard jurimetrics data, such as a scrupulous analysis of the judicial decisions both with and without the technological tool using a set of clearly defined criteria. However, such data might not be available for the initial decisions to build or to test the tools.

Moreover, most of the matters that are discussed in the field, such as algorithmic justice or the regulation of artificial intelligence, are navigated by people. People differ regarding their role within the legal system and their potential influence on court decisions. For example, a regulatory body member might decide to implement specific court tools due to their progressive attitudes. At the same time, a litigant might file a case regarding an unfair process because they think that the algorithms violate their right to due process (; ). Moreover, a judge might over-rely on a decision aid (). In addition, a citizen might join a protest against a seemingly unjust use of technology in courts (). Furthermore, judges are a part of society and have a role in shaping it (). Despite these factors, there is a shortage of empirical investigations into how different people feel about legal technologies in courts. Thus, this paper explores whether the technology acceptance model can be applied in order to investigate the attitudes towards legal technologies in courts among people with different characteristics, such as court experience, the legal profession, age, and gender.

Although the most sensational tools—such as a robot judge—might not be a possible or desirable option for the foreseeable future (), the legal technologies for courts are already quite progressive. Some countries were using such technologies in courts even before the pandemic. For example, some provinces of Canada were already settling small claims by using algorithms. Estonia claimed to be creating an algorithm for small claims in order to help with the court backlog. The USA used programs that help with recommendations on risk assessments (). Lithuania already had an e-filing system (). In addition, China employed a database in order to warn a judge if a sentence significantly differed from the sentences of similar cases and had launched an e-court (; ).

It is essential to explore people’s attitudes towards legal technologies before their implementation. Notably, both court clients and lawyers might be unsatisfied with the most state-of-the-art technology (; ). For example, in 2019, France made it illegal to engage in judicial analytics for predicting individual judicial behavior, i.e., “the identity data of judges and members of the judicial registry cannot be used to aid in evaluating, analyzing, comparing or predicting their professional practices” (). In the Netherlands, civil rights organizations brought the fraud detection system that has been used in Dutch courts since 2014 to the District Court of The Hague, which decided that it violates Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (the right to respect for private and family life) (). The infamous Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) faced substantial public, scholarly, and legal criticism regarding its racial bias (; ). However, there are only a handful of studies regarding in-advance legal technology perception; one study was conducted in order to capture the ethical concerns for technologies in law () and there were a couple of qualitative studies on robot lawyer acceptance in private legal practice (; ).

Technology development, as well as use, depends on humans, and technologies might challenge humans. For example, legal technologies require new knowledge and skills (; ), but only a few educational institutions offer legal technology courses or modules (). While some lawyers are more likely to adapt to the growing competition of legal services that are aided by technologies, others are skeptical about the change (; ; ). In addition, human cognitive and behavioral peculiarities might distort the tool’s intended use (). Understanding the human perceptions and attitudes towards related technologies might be crucial to the successful development and implementation of legal technologies in courts.

A critical question regarding legal technologies in courts is what people expect from the technologies concerning fairness. From the perspective of perceived fairness, people need distributive and procedural fairness in order to be satisfied with courts (). On one hand, algorithmic fairness discusses the substance of the algorithm (; , ; )—in a sense, distributive justice. There is already some exciting research on moral judgment, suggesting that people think that it is more likely that an algorithm would make a conviction than a human judge (). On the other hand, procedural fairness provides one of the primary sources of trust and legitimacy in courts (; ). The principal procedural fairness concerns, such as voice, neutrality, respect, and trust, might become even more critical with the automation of courts (). The emerging studies of automated decisions find that human involvement in decision-making makes a qualitative difference in the sense of fairness (). Thus, it is crucial to investigate the fairness expectations for the court processes involving technology.

This study contributes to the expanding field of legal technologies by exploring the technology acceptance in courts among various groups of people. Firstly, this research provides a theoretical input by examining the validity of the technology acceptance model (TAM) (, ; ; ) in the court’s context for different groups of people. Furthermore, the TAM is extended with relevant constructs, such as the perceived risk and trust in technologies. Adding fairness expectations for technologies in courts to the research model contributes to the theorizing about fairness perceptions in courts. Finally, exploring personal innovativeness, age, court experience, and profession (lawyers vs. others) helps us to understand the potential differences in different groups of people.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

The technology acceptance concept is not new (). One of the most parsimonious and favored models that is used in order to investigate the intention to use technology in various domains () is the technology acceptance model (TAM) (; ; ; ). There are already about 20 meta-analyses of the TAM (), and many studies exploring technology acceptance in various fields. The TAM has been used within the legal field (; ), however, only in qualitative studies, and only focused on a specific question of a robot lawyer. In accordance with the aim of the study, the main TAM variables, as well as the TAM extensions, have been specified and the hypotheses have been stated further.

2.1. Main TAM Variables

The original TAM posits that a few core variables affect the behavioral intention to use technology (BI)—such as the attitude toward using technologies (ATT), the perceived ease of use (PEOU), and the perceived usefulness (PU) (). Later versions (), as well as most of the extensions of the TAM, omit the attitude toward using technology (; ; ; ) and replace it with various external variables, i.e., variables that were not originally included in the TAM, such as self-efficacy and subjective norms (). Following the TAM, the perceived usefulness and ease of use (construct definitions are presented in Table 1) are expected to positively influence the attitudes toward using technologies (; ). Additionally, the perceived ease of use positively affects the perceived usefulness. Therefore, the following three main hypotheses have been tested:

Hypothesis 1.

The perceived usefulness significantly positively affects the behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts.

Hypothesis 2.

The perceived ease of use significantly positively affects the behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts.

Hypothesis 3.

The perceived ease of use significantly positively affects the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts.

Table 1.

Definitions of the constructs of the current study.

2.2. TAM Extensions

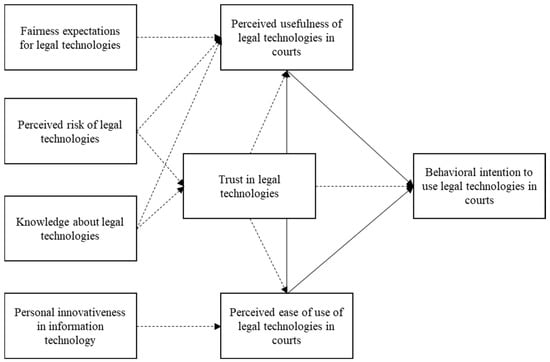

The first version of the TAM already indicated the possible influences of other variables (); additionally, subsequent reviews of the models TAM2 () and TAM3 () systematically added more external variables and relationships within the TAM. Various additions to the TAM are quite frequent in literature (; ; ; ; ). However, the external variables significantly differ across study fields (). The current study has explored the impacts of trust, perceived risk, fairness expectations, knowledge about legal technologies, and personal innovativeness (the proposed model is presented in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed research model. The solid lines represent original TAM relationships; the dashed lines represent relationships proposed in the current study.

2.2.1. Trust in Legal Technologies

Trust is essential, especially in the early stages of technology adoption (). Furthermore, trust in technologies may be an even more critical issue in the legal domain (). On the one hand, the legal sector, in general, might be characterized as being risk-averse, conservative, and slow to change (). On the other hand, the careful evaluation and consideration of the advantages and disadvantages of any innovation are crucial to legal services. Trust is often linked to the TAM in various fields of study (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

A meta-analysis was carried out in order to better understand the role of trust in information systems (). The effect sizes for the relationships between trust and the perceived ease of use, the perceived usefulness, the attitude, and the behavioral intention to use technology were analyzed using data from 128 articles. The results revealed that trust is significantly related to all of the primary TAM constructs, as follows: trust–behavioral intention (r = 0.483), trust–perceived usefulness (r = 0.511), and trust–perceived ease of use (r = 0.472). The current research has explored the relationships between trust and the behavioral intention to use technologies in courts, the perceived ease of use, and the usefulness of legal technologies in courts with the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4.

Trust in legal technologies significantly positively affects the behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts.

Hypothesis 5.

Trust in legal technologies significantly positively affects the perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts.

Hypothesis 6.

Trust in legal technologies significantly positively affects the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts.

2.2.2. Knowledge about Legal Technologies

In addition, this study has attempted to capture the cognitive component of beliefs about legal technologies. In this study, the cognitive component was defined as the knowledge that an individual holds about the state of legal technologies (). According to the diffusion innovation theory (; ), the first stage of technology adoption begins with the knowledge or awareness stage, when an individual is exposed to the innovation but lacks complete information. Therefore, although legal technologies are progressing rapidly in many corners of the world and often appear in the media, the general population should not be expected to be very knowledgeable about the topic, as reflected in the shortage of research. More importantly, the trust in legal technologies may be based on the knowledge about them. Therefore, the following two hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 7.

Knowledge about existing technologies for courts has a significant positive influence on the trust in legal technologies.

Hypothesis 8.

Knowledge about existing technologies for courts has a significant positive influence on the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts.

2.2.3. Perceived Risk of Legal Technologies

New technologies, in general, are associated with many risks, such as confidentiality, uncertainty, and unpredictability (; ). These concerns are critical in the legal domain (; ; ), especially when considering the magnitude of damage in the case of a bias or a mistake.

Risk is an often-used addition to the TAM in various domains (; ; ; ). The perceived risk may predict the perceived usefulness () and the intention to use the technology directly (; ). In the variant of TAM extension with both trust and risk, the risk directly influences the trust (). According to the hypothesizing of the TAM, the external variables would affect the behavioral intention to use technology through the perceived ease of use or the perceived usefulness of the technology. Therefore, the following two hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 9.

The perceived risk of legal technologies has a significant negative effect on the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts.

Hypothesis 10.

The perceived risk of legal technologies has a significant negative effect on the trust in legal technologies.

2.2.4. Fairness Expectations for Legal Technologies in Courts

There is a heated debate about algorithmic fairness issues (; ; ; , ; ). Within the debate, distributive fairness receives most of the attention. Indeed, the fair distribution of resources, e.g., regarding discrimination issues (), is critical. At the same time, procedural fairness is making its way into the discussion (; ; ). It is important to stress that procedural fairness—which is the fairness of the decision-making process—is not less important than the fairness of the outcomes, especially in the legal domain (). Moreover, the fairness expectations play an essential role in shaping the fairness perceptions on their own when the justice event occurs, e.g., when the litigant goes to trial (). Arguably, the procedural fairness expectations are just as crucial as the distributive fairness expectations, and the latter are difficult to adequately assess for a layperson (; ). Fairness is the key feature of any court service, and it is strongly related to trust in courts (). Thus, it could be expected that fairness expectations have an impact primarily on the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts, as follows:

Hypothesis 11.

Fairness expectations for legal technologies in courts have a significant positive effect on the perceived usefulness of legal technologies.

2.2.5. Personal Innovativeness in Information Technology

Individual characteristics, such as personal innovativeness in information technology (see definition in Table 1), might predict the core TAM variables, such as the behavioral intention to use technology (; ). In the case of legal technologies, however, the degree to which an individual is relatively early in adopting new ideas might be more related to their experience of using various technologies in their daily life and, in turn, may have a direct influence on the perceived ease of use instead of the attitude toward using technology, as follows:

Hypothesis 12.

The personal innovativeness in information technology has a significant positive effect on the perceived ease of use of legal technologies.

2.3. TAM Moderators

In this section, moderators are explored—which are the variables that affect the strength of the relationship between the dependent and the independent variables, such as trust and the behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts.

2.3.1. Profession

Previous literature has indicated the importance of contextual factors in predicting technology acceptance (; ); particular to the legal domain are the court experience and the legal profession factors. However, the attitudes of the representatives of the legal profession are rarely studied within these contexts. As lawyers are generally skeptical of any innovations (), the legal profession might play a role in legal technology acceptance. Thus, all hypotheses have been tested and compared between legal professionals and others.

2.3.2. Court Experience

Court experience is a known factor impacting the perceived trust, legitimacy, and fairness of the court and legal system (; ; ). Most people do not understand how courts operate, nor what to expect in a court hearing. Only a handful of citizens have been to court, and it provides a much stronger basis for attitudes than the media and other sources of information. Hence, court experience might also be critical for the TAM relations. Thus, all hypotheses have been tested and compared between people with and without court experience.

2.3.3. Age

Although chronological age might be problematic in understanding the attitudes toward technologies (), age might influence the attitude toward implementing and using legal technologies in courts. For example, age is related to court perceptions (; ) and fairness expectations (). Older people are expected to trust courts less, at least in Lithuania (). Therefore, it might be expected that older people may believe that it is more difficult to use legal technologies in courts, due to them being digital immigrants (i.e., people who were born or brought up before the widespread use of digital technology) and being more used to courts with little to no technological aid. Thus, all hypotheses have been tested and compared between younger and older age groups.

2.3.4. Gender

Another commonly researched demographic characteristic is gender. Gender has also been studied within the context of the TAM (; ; ). However, the results are split in the following way: some studies show no gender effects (; ; ; ), while others detect some (; ). Due to the lack of data in the legal technology acceptance field, gender differences have been explored throughout the paths of the proposed model in this study.

3. Methods

A quantitative research strategy, in particular, surveying, was chosen for this study. Surveying suffers from several shortcomings, such as self-report biases, discrepancies in how the participants understand the survey items, and others, which may undermine the quality and the potential implications of the obtained results. Nevertheless, there are several reasons why it is crucial to analyze people’s perceptions empirically and quantitatively. First, empirical data on different people’s attitudes towards technologies in courts are needed to better address people’s concerns. Moreover, quantitative analysis allows testing whether a technology acceptance model, which is helpful in understanding and predicting people’s behavioral intentions to use technologies in other high-stakes environments, such as healthcare (), is also applicable to a court context. Testing the TAM statistically and verifying its components across different groups of participants in the study has helped us to achieve an initial understanding of the limits of the model’s applicability. In addition, a structural analysis of the model has enabled the assessment of the relationships among the constructs, thus helping us to better understand the significant points regarding how people think about technologies in courts. While quantitative analysis is not the most effective at capturing the individuals’ personal views of courts and technologies, it can provide evidence of people’s perceptions and a sound basis for further, more in-depth research.

3.1. Study Sample

The proposed research model was tested using survey data collected online. The study had only one exclusion criterion, i.e., being under 18 years of age. However, there were several criteria for inclusion in the study, as follows: legal profession, court experience, and age. It was preferable to survey younger people (18–39 years of age) and relatively older people (40 years of age and older). The age threshold was relative, based on previous research showing differences in TAM variables within 30 to 40 years (). Next, it was preferable to have a substantial part of the sample with a legal background, i.e., in the legal profession. Along the same lines, court experience was significant. The snowballing method was used to survey people from the relevant groups.

3.2. Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire included several sections—the first section evaluated participants’ knowledge of legal technologies related to courts. Participants were presented with six statements about various legal technologies. Therein, six types of relatively more complex technologies were listed, such as document submission and initial classification regarding the presence of a legal basis, a decision support system that suggested appropriate penalties for the case, and algorithms for solving small claim disputes. For example, participants of the study read the following statement: “In some countries, judges have access to a program that provides the judge with a detailed analysis of the case, evaluates arguments, and identifies possible outcomes of the case”. Then, the participants were asked to indicate their level of knowledge on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. The following five values reflect the meaningful differences in the knowledge levels of people with various backgrounds: “I know absolutely nothing about this”, “I have heard something about this”, “I have taken a closer look into these technologies”, “I am quite knowledgeable in these technologies”, and “I have tried this or a similar technology”.

The second section of the questionnaire measured participants’ technology acceptance constructs on a scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Seven values for a scale assessing technology acceptance are prevalent with the use of the TAM and are usually better in terms of statistical issues, e.g., distribution normality. These, and all other items, were revised or adopted from previous research, except for the knowledge about legal technologies construct and an item in the ATT scale (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Constructs of the study, items, and their sources.

The third and fourth sections concerned the additional constructs, such as perceived risk, fairness expectations, trust in technology, and personal innovativeness, and were also measured using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree).

Lastly, participants were asked for their demographic information, such as age, sex, court experience, and the legal profession.

A modest pilot study (N = 37) was conducted to test the comprehensibility and reliability of the items. The pilot study participants filled in the survey and commented on each questionnaire block’s comprehensibility, wording, and content. There were also lawyers, people with court experience, and people from all three age groups. The reliability of the questionnaire items was satisfactory as the internal consistency coefficient, Cronbach’s alpha, was above 0.7 for all scales.

3.3. Data Analysis

The PLS-SEM approach was chosen for this study as it is more suitable for exploratory analyses and theoretical extensions than the CB-SEM (; ). In addition, the PLS-SEM is known for greater statistical power to detect truly significant relationships (). Following recommendations for PLS-SEM analysis (; ; ), firstly, the measurement model was evaluated and then the structural model was evaluated. Lastly, multigroup analyses were performed to assess potential structural differences between the groups. SmartPLS v. 3.3.3 () software was used.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The study was conducted in Lithuania. A total of 408 people participated in the study and Table 3 contains the characteristics of the study sample. The range of participants’ age was from 19 to 81 years, with an average of 37.44 years (SD = 13.28). There were 145 lawyers and law students in the sample (35.8%; 79 lawyers and 66 law students). More than half of the sample had court experience—245 people (60.2%), including 111 lawyers and law students who had been to court (45.7% out of the 245 who had court experience), and 132 others (54.3% out of the 245 who had court experience).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study sample.

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

The evaluation of the measurement model consisted of an assessment of the internal consistency, the convergent validity, and the discriminant validity (; ; ). The results revealed a satisfactory internal consistency and convergent validity (see Table 4) as follows: the Cronbach’s α values were mainly in the range of 0.7–0.95, the composite reliability values were 0.7 < CR > 0.95, the average variance extracted was AVE > 0.5, and the factor loadings were all larger than 0.708 (). The discriminant validity indicator Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) did not exceed 0.9 () (see Table 5).

Table 4.

Means (M), standard deviations (SD), factor loadings, Cronbach’s Alphas (α), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) of the constructs.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity of the constructs: Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT).

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

The structural model was assessed adhering to the following steps (): checking for collinearity issues, evaluating the model’s overall quality, and testing the hypotheses. Notably, the analysis revealed that there were no critical levels (see Table 6) of collinearity among any of the predictor variables (VIF < 3) (; ; ).

Table 6.

Variance inflation factor (VIF) among variables.

The overall quality of the research model was reflected in the coefficient of determination (R2) (; ; ). The research model was able to explain the changes in the behavioral intention (R2 = 0.648), the perceived usefulness (R2 = 0.536), and the trust in legal technologies moderately well (R2 = 0.412) (see Table 7). The model was weaker in explaining the perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts (R2 = 0.296).

Table 7.

Hypothesis testing results: path coefficient estimation and bootstrapping results.

Another critical measure of the quality of the research model was the Stone–Geiser’s Q2 value (; ). Blindfolding was performed in SmartPLS (). The research model had considerable predictive relevance for the behavioral intention (Q2 = 0.573), moderate relevance for the trust in legal technologies (Q2 = 0.324), and moderate perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts (Q2 = 0.421). Again, it was weaker for the perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts (Q2 = 0.211).

The last step in evaluating the quality of the research model was to evaluate its predictive performance. Thus, following (), a 10-fold cross-validation was conducted with the PLSpredict function (). The root mean squared error (RMSE) was compared between the partial least squares (PLS) and the linear regression model (LM) for each indicator of those variables (). The results revealed that the research model had a medium predictive power. The PLS model yielded lower prediction errors in terms of RMSE than LM for most of the indicators (see Appendix A Table A1).

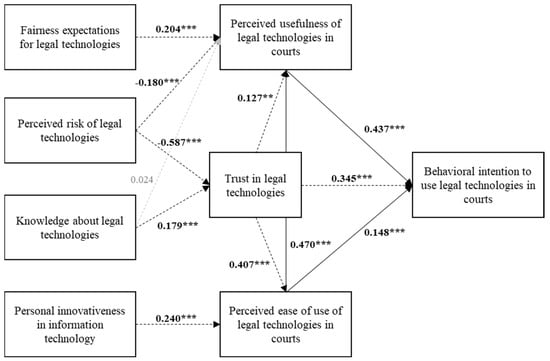

This study tested the relationships between the dependent and the independent variables using the path coefficient (β) and t-statistics (). Bootstrapping with 5000 samples was performed in order to obtain the significance of the path coefficients. Table 7 and Figure 2 represent the hypothesis testing results.

Figure 2.

Structural model assessments results. The solid lines represent original TAM relationships; the dotted lines represent relationships proposed in the current study. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01.

The primary hypotheses regarding the TAM relationships were supported (H1: β = 0.437, p < 0.001, H2: β = 0.148, p < 0.001, H3: β = 0.127, p < 0.001). Next, all three of the hypotheses regarding the trust in legal technologies were supported, suggesting that trust significantly positively affects all of the main TAM constructs (H4: β = 0.345, p < 0.001, H5: β = 0.407, p < 0.001, H6: β = 0.470, p < 0.001). Although the knowledge about legal technologies affects the trust in legal technologies (H7: β = 0.179, p < 0.001), this is not true for their perceived usefulness (H8: β = 0.024, p = 0.441). Moreover, the perceived risk of legal technologies in courts significantly negatively affects their perceived usefulness (H9: β = −0.180, p < 0.001) as well as the trust in legal technologies (H10: β = −0.587, p < 0.001). In addition, as expected, the fairness expectation for legal technologies significantly positively affects the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts (H11: β = 0.204, p < 0.001). Lastly, the personal innovativeness in information technology has a significant positive effect on the perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts (H12: β = 0.240, p < 0.001).

4.4. Multigroup Analyses

The multigroup analyses were performed in order to explore the role of age, gender, the legal profession, and court experience. The missing cases were not included in the analyses and each subsample fulfilled the sample size requirements (). The path coefficients (see Appendix B Table A2, Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5) and the coefficient of determination (R2) were compared between the groups (see Appendix B Table A6). In addition, cross-tabulation and a comparison of means between the groups were performed (see Appendix B Table A7 for cross-tabulation and Table A8 for mean comparisons).

4.4.1. Legal Profession

The multigroup analysis did not reveal significant differences among the research model paths (see Appendix B Table A2). Moreover, the proposed model was able to explain the behavioral intention to use and the perceived usefulness of technologies in courts similarly for both the legal (R2 = 0.665) and the other professions (R2 = 0.647) (see Appendix B Table A6). However, it was less suited to explain the perceived ease of use for the legal professions (R2 = 0.198) than the other professions (R2 = 0.360). Interestingly, the model explains the trust in legal technologies better for the legal professions (R2 = 0.528) than the other professions (R2 = 0.374).

4.4.2. Court Experience

The trust in legal technologies (TRST) had a more significant effect on the behavioral intention to use legal technologies (BI) in courts for people with no court experience (β = 0.487, p < 0.001) compared to people with court experience (β = 0.254, p < 0.001) (see Appendix B Table A3). Accordingly, the proposed model explained the perceived usefulness of legal technologies significantly better for people without court experience (R2 = 0.643) compared to those with court experience (R2 = 0.474) (see Appendix B Table A6). What is even more interesting is that in the group without court experience, the perceived ease of use (PEOU) did not affect the behavioral intention to use technologies in courts (BI) (β = −0.031, p = 0.607). In the group with court experience, the effect was present (β = 0.263, p < 0.001) (see Appendix B Table A3).

4.4.3. Age

The multigroup analysis by age yielded even more exciting results. The effect that was insignificant in all of the analyzed models was present in the group of 18–39-year-olds; the knowledge about legal technologies had a slight but significant positive effect on the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts (β = 0.087, p = 0.042), while it was still non-significant for the older people (>40 years old) (β = −0.053, p = 0.278) (see Appendix B Table A4). Moreover, the model better explained the beliefs about the perceived ease of use (R2 = 0.451) and the usefulness of legal technologies for the older people (R2 = 0.666) compared to the younger people (PEOU: R2 = 0.225, PU: R2 = 0.485) (see Appendix B Table A6).

4.4.4. Gender

Lastly, the gender effects were tested. The path analysis revealed no significant differences between females and males (see Appendix B Table A5). The proposed model explained the male intentions to use legal technologies better (R2 = 0.743) compared to females (R2 = 0.580) (see Appendix B Table A6).

4.5. Interaction between Profession and Court Experience

The analysis of the mean differences in Appendix B Table A7 prompted testing the interaction effects. A two-way analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) was performed in order to test the interaction effects of the profession and court experience (see Table 8). The interaction was significant for the trust in legal technologies and the behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts. Although the profession and court experience both affected the knowledge about legal technologies, there was no interaction effect.

Table 8.

Interaction effects of the legal profession and court experience.

The results in Table 9 show that people with court experience, both lawyers and others, similarly trusted legal technologies. However, if a person did not have court experience, their profession became important, for example, the lawyers without court experience trusted legal technologies less than other people. The results in Table 10 show a similar pattern of results—having no court experience or legal profession resulted in the lowest intention to use legal technologies in courts. Meanwhile, the lawyers with court experience were the most inclined to use legal technologies in courts. Notably, the 34 participants with the legal profession and without court experience were mostly law students (31 students).

Table 9.

Means of trust in legal technologies according to court experience and profession.

Table 10.

Means of behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts according to court experience and profession.

5. Discussion

The research that is presented in this paper offers a small window into people’s perceptions of legal technologies in courts. While the study cannot encompass the depth and variety of concerns about technology in courts, and in society as a whole, the results revolve around the issue of how much people would be willing to support technologies in courts. The technology acceptance approach allows us to answer some questions about how various people think of technologies in courts. Importantly, the research does not imply that courts should implement more technologies, instead, the attitudes of various people are examined.

Technology acceptance models were present before 2000 () and have been applied to many different fields (; ; ; ; ; ). Although some legal technologies have been in use for more than 20 years, the public perceptions of those technologies have not been researched. Further complications come from the legal technologies themselves—as some are designed only for lawyers, some are made to automate document submission, and other processes and involve clients, not lawyers. Moreover, there is no definite answer to the question of the extent of the public influence on courts and artificial intelligence, given that they may not have the relevant experience or expertise (). Technology acceptance seems to be the most appropriate concept, as it interests scientists, developers, and stakeholders—the factors of technology acceptance may guide the design of the technology and predict the response that it receives ().

At the beginning of the current research, only one paper presented an empirical study of legal technology acceptance (); now, there are two (). Taken together, the results of both the aforementioned studies (; ) and the current study support the idea that the widely used technology acceptance model (; ; ) is also applicable to the legal technology field. The hypotheses on the primary TAM constructs—the behavioral intention to use technologies, the perceived usefulness, and the ease of use—were confirmed in the overall sample. Notably, in this study, the behavioral intention to use technologies was operationalized as the strength of one’s intention to support legal technologies in courts. Thus, the results imply that in order to be willing to support legal technologies in courts, people have to perceive the technologies as both useful and easy to use.

5.1. Trust in Technologies

Every field has its peculiarities and contextual factors that are usually taken into account in the TAM. In this study, the TAM was extended with several legal technology-relevant constructs. Firstly, the trust in legal technologies was chosen because trust in technologies is a crucial and exceptionally researched construct in the context of technology acceptance (). Notably, the trust in legal technologies scale does not specify the type of or the other characteristics of the legal technologies, and the participants of the study were introduced to several kinds of more complex legal technologies, such as a decision support tool for judicial decision making, or a document automation tool that also classified the documents into having a legal basis and not. It was found that the trust in legal technologies affects how much people would support legal technologies in courts, how they see the usefulness, and the perceived ease of use of legal technologies. Interestingly, trust is more important for the perceived ease of using legal technologies in courts—possibly because courts might be seen as very complicated systems. In turn, trust is affected by the knowledge about legal technologies and the perceived risk.

5.2. Perceived Risk

People will likely have little in-depth knowledge about legal technologies. Therefore, the general risk that was associated with legal technology use in courts was measured in this study. The perceived risk negatively affected the trust and the perceived usefulness of legal technologies. These results reflect the findings of technology acceptance research in other fields (; ). Given the effect size of risk on trust, the perceived risk of legal technologies seems to be quite crucial for people. Notably, other studies measure the direct influence of perceived risk on the behavioral intention to use technologies (; ). Clarifying the role of the perceived risk in people’s intentions to support technology use in courts could be valuable for a better understanding and navigation of people’s attitudes towards legal technologies. In addition, this study did not focus on the particular facets of risk, e.g., financial or privacy risks (only sensitive information was mentioned) (). The particular facets of risk could be explored in a more detailed study where people were given more detailed information about the legal technologies in courts.

5.3. Knowledge about Legal Technologies

Another contextual variable that was added to the model is the knowledge about legal technologies. The cognitive component of knowledge is missing in some technology acceptance studies (). The TAM does not explicitly anticipate the role of knowledge about a particular technology. Therefore, a construct for entry-level knowledge was borrowed from the diffusion of innovation theory (; ; ; ). Arguably, the knowledge factor is vital in the legal field, especially in the court context, as people usually lack the legal and practical knowledge about how courts work and how to measure their performance. Thus, it is expected that people would not be very knowledgeable in the legal technology field either. Indeed, this was the case in this study.

Moreover, knowledge about legal technologies affects the trust in those technologies. In particular, knowledge about the existing legal technologies boosts the trust in them. However, knowledge did not affect the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts in this study, except for a subsample of 18–39-year-old people (the effect was relatively weak). The lack of a strong relationship between the knowledge and the perceived usefulness could suggest that the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts may have come from sources other than the knowledge about what technologies exist. For example, understanding how courts work in general, the trust in courts, and the fairness expectations for court processes with legal technologies might have a more prominent effect on the perceived usefulness of legal technologies than just the knowledge about existing legal technologies.

5.4. Fairness Expectations

The fairness expectations for legal technologies are a new potential component of attitudes toward technologies in courts. Given that the main focus of court work is justice, the fairness expectations directly relate to the perceived usefulness of the legal technologies that are used in courts. In this study, the fairness expectations were based in the procedural fairness paradigm (; ; ; ). Therefore, the participants were asked to evaluate how they would see the ethicality, the voice, and other features of court processes where legal technologies would be incorporated. People have high fairness expectations for court processes involving legal technologies. The fairness expectations directly influence the perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts. That is, the more fairness that is expected of the processes involving legal technologies, the more useful they seem. The high fairness expectations do not mean that people are not concerned about the fairness of the automated processes. The results might indicate that people have high hopes for the automated processes and that they anticipate that courts would solve any arising issues. The relationship between the fairness expectations for court processes with incorporated legal technologies and the perceived usefulness of those technologies emphasize the need to explore the components of the perceived usefulness regarding legal technologies.

5.5. Personal Innovativeness

Given the relatively conservative nature of the legal field, personal innovativeness in information technology was added to the model of this study. Interestingly, it was found that the people with legal professions were not less innovative than the people with other professions. The personal innovativeness in information technology positively affects the perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts. Thus, the more innovative a person is, the easier it seems for them to use legal technologies in courts. These results mirror those from other fields (; ).

5.6. The Legal Profession, Court Experience, Age, and Gender

The profession, the court experience, the age, and the gender moderate some of the relationships of the analyzed model. Most importantly, the legal profession and court experience affect the trust and the behavioral intention to support legal technology use in courts. Surprisingly, lawyers without court experience trust legal technologies less than others and are the least supportive of legal technology use in courts. Similarly, lawyers with court experience are the most supportive of legal technologies in courts. One possible explanation for these discrepancies in the perceptions of legal technologies is that the lawyers are more knowledgeable about legal technologies than the other people in this study1. However, it would be interesting to explore why legal knowledge and no court experience affect the legal technology acceptance. In this study, most of the lawyers without court experience are law students; however, this does not mean that they should be the least trusting of legal technologies in courts simply because they are young. It is feasible that academics could have influenced these students in the university. Not many universities teach about legal technologies yet (). Possibly, academics, and sometimes even researchers of legal technologies, might be more or less accepting of legal technologies.

Additionally, the people with legal professions had lower fairness expectations than the other people. The fairness expectations might be lower due to the general skepticism towards legal technologies. An alternative explanation is that lawyers might feel that court processes are less fair, and, together with some skepticism, they might not think that legal technologies would add much fairness to them. Lawyers are rarely included in studies of court fairness perceptions; therefore, studying both the public and lawyers’ perceptions could enrich our understanding of fairness in courts.

Moreover, for people without court experience (both lawyers and others), the perceived ease of use does not affect the behavioral intention to support legal technologies in courts. The lack of relationship between the perceived ease of use and the behavioral intention suggests that it would be essential to investigate the perceived ease of use of legal technologies further. It could be hypothesized that the people without court experience do not care about the ease of use of legal technologies in courts. Undoubtedly, the ease of use predicts the behavioral intention to support legal technologies for people with court experience. Therefore, it is crucial to take into account the court experience factor.

Furthermore, both age and gender might be other factors to consider in legal technology acceptance. For the younger people, knowledge about legal technologies slightly affected the perceived usefulness of the legal technologies, but there was no such effect for the older people. In essence, these results suggest that knowledge about legal technologies might change the opinions of younger people more than the opinions of older people. More research should be conducted in order to address the age differences in the perceptions of legal technologies, as human perceptions of AI might vary with age ().

Interestingly, the analyzed model is better suited to explain the male intentions than the female intentions to support legal technologies in courts. Although more participants were female, gender was distributed relatively evenly through all of the subsamples (profession, court experience, and age). Therefore, gender should not be related to the other sample characteristics. In this study, the females thought that the technologies were more helpful than the males. However, there were no other differences in the perceptions between the gender groups.

5.7. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study is important in building the knowledge base on legal technology acceptance, it has some limitations. One of the limitations is related to the sample that was used. In particular, this study made use of a mixed subsample of lawyers by adding in law students. It could be argued that law students might quickly become technology users and even decision makers. However, additional investigations with more concentrated samples would greatly benefit future work in this area.

The results of the current study highlight the need for more in-depth research. Some of the variations in the attitudes toward legal technologies in courts could be found in different cultures. For example, the support for legal technologies might depend on the trust in courts, not only on the trust in the legal technologies themselves. Lithuania is a post-Soviet country with a tradition of a general distrust of the legal system. It would be helpful to compare Eastern European countries with others. However, distrust of courts might also appear due to well-known cases and other events, such as the discovery of a fraud detecting system in the Netherlands ().

However, would some distrust in courts ensure the support for automation? Research into other settings suggests that people might want to exchange the consistency that is provided by automation for the ability to influence decisions due to human factors (; ). These fascinating assumptions could be tested in experimental studies within court contexts.

Personal innovativeness might also vary according to the cultural values (). In particular, Lithuania has many online public services in health care, migration, taxes, and other areas. Thus, the state of the technological advancement in the country could also play a role. For example, being used to technical solutions in daily affairs might lead to more positive attitudes towards legal technologies.

Notably, technological progress has not been even among different countries; different levels of automation that have already been reached in courts may impact the behavioral intention to use legal technologies.

The presented model might strongly benefit from data on actual judicial decision-making, both before and after the implementation of a certain tool. The combination of jurimetrics, along with people’s perceptions of the different characteristics of the tool, might provide the best insights into the actual usefulness of the tool. Additionally, people’s opinions and perceptions might change given the hard data. Therefore, more studies are needed in order to address these issues.

Finally, the technology acceptance model and the quantitative strategy of this study cannot fully address the underlying influences on people’s attitudes and their awareness of them. This study risks construing cognitive processes that were never there (), e.g., some people might never think about technologies in courts. At the same time, following the innovation diffusion theory, technology awareness is the first stage of the innovation diffusion process, and the study participants were, first and foremost, made aware of several types of technologies that are used in courts. Moreover, people form expectations toward courts, even if they are unaware of the legal processes and if their expectations do not match reality. Given the complexity of the awareness concept, this research cannot be used in order to analyze the need for technologies in courts critically.

6. Conclusions

What are people’s attitudes towards legal technologies in courts? What is the most critical factor in predicting people’s willingness to adopt such technologies, given their potentially limited knowledge? How do individual differences factor into people’s opinions about AI and other technologies in courts? This paper adds to the growing research on people’s perceptions and attitudes towards legal technologies by providing data on people’s intentions to support legal technologies in courts.

The perceived usefulness of legal technologies is the most crucial factor in predicting the intentions to support legal technologies in courts. The perceived usefulness, in turn, may form through the trust in legal technologies, the perceived risk, and the knowledge about legal technologies. The results suggest that people are concerned with the usefulness, the ease of use, and other issues, similarly to other technologies in other settings, such as health or education. In addition, the fairness expectations play a role in the acceptance, for example higher expectations may strengthen the perceptions of usefulness. Notably, having more in-depth knowledge and data on the performance of technologies could alter the perceptions. Nevertheless, people with different levels of knowledge may still hold a variety of opinions, depending on other factors. Additionally, the multigroup analyses that were conducted in this study have allowed us to assume that the technology acceptance model could be used in order to investigate both lawyers’ and the general populations’ technology acceptance. This provides guidance for the implementation and the design of technologies.

To the author’s knowledge, this study is one of the first steps toward having theory-driven empirical data on the legal technology acceptance in courts, given its rapid progress. A qualitative exploration of people’s perceptions regarding technologies in courts could reveal some more specific concerns. A study into whether judges and other court staff need technology is clearly overdue. In general, more studies are needed in order to better grasp the differences in opinion that various groups of society might have towards legal technologies in courts. The current research shows that personal innovativeness, the legal profession, the court experience, the age, and even gender might direct people’s opinions. These results might have various implications for the development and the implementation of technology. Thus far, it could be advised to carefully choose the members of AI committees and other regulatory bodies.

Funding

This project has received funding from European Social Fund (project No. 09.3.3-LMT-K-712-19-0116) under grant agreement with the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Psychological Research Ethics Committee of Vilnius University (protocol code no. 26/(1.3) 250000-KP-25 and date of approval: 13 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study will be openly available in MIDAS repository at 10.18279/MIDAS.AttitudestowardslegaltechnologiesincourtsusingTAM.csv.189143s.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparison of the root mean squared error (RMSE) for the partial least squares (PLS) and linear regression model (LM).

Table A1.

Comparison of the root mean squared error (RMSE) for the partial least squares (PLS) and linear regression model (LM).

| Indicator | RMSEPLS | RMSEML | RMSEPLS–RMSEML |

|---|---|---|---|

| BI1 | 1.323 | 1.267 | 0.056 |

| BI2 | 1.24 | 1.144 | 0.096 |

| PEOU1 | 1.419 | 1.456 | −0.037 |

| PEOU2 | 1.323 | 1.33 | −0.007 |

| PEOU3 | 1.469 | 1.5 | −0.031 |

| PU1 | 1.298 | 1.282 | 0.016 |

| PU2 | 1.29 | 1.299 | −0.009 |

| PU3 | 1.187 | 1.159 | 0.028 |

| TRST1 | 1.296 | 1.309 | −0.013 |

| TRST2 | 1.324 | 1.335 | −0.011 |

| TRST3 | 1.267 | 1.273 | −0.006 |

Note. BI = behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts, PEOU = perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts, PU = perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts, and TRST = trust in legal technologies.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Multigroup analysis by legal profession (legal vs. other).

Table A2.

Multigroup analysis by legal profession (legal vs. other).

| Hypothesis | β (Legal) (n = 145) | β (Other) (n = 260) | β (Legal)–β (other) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 PU → BI | 0.402 | 0.454 | −0.053 | 0.577 |

| H2 PEOU → BI | 0.189 | 0.118 | 0.071 | 0.395 |

| H3 PEOU → PU | 0.141 | 0.121 | 0.020 | 0.826 |

| H4 TRST → BI | 0.377 | 0.343 | 0.033 | 0.758 |

| H5 TRST → PEOU | 0.342 | 0.438 | −0.096 | 0.324 |

| H6 TRST → PU | 0.505 | 0.456 | 0.049 | 0.637 |

| H7 KNW → TRST | 0.220 | 0.186 | 0.034 | 0.617 |

| H8 KNW → PU | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.039 | 0.562 |

| H9 PR → PU | −0.112 | −0.208 | 0.097 | 0.350 |

| H10 PR → TRST | −0.654 | −0.550 | −0.104 | 0.125 |

| H11 FE → PU | 0.155 | 0.228 | −0.073 | 0.357 |

| H12 PIIT → PEOU | 0.190 | 0.270 | −0.081 | 0.422 |

Note. BI = behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts, PU = perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts, PEOU = perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts, TRST = trust in legal technologies, KNW = knowledge about legal technologies, PR = perceived risk of legal technologies in courts, FE = fairness expectations for legal technologies in courts, and PIIT = personal innovativeness in information technology.

Table A3.

Multigroup analysis by court experience (yes vs. no).

Table A3.

Multigroup analysis by court experience (yes vs. no).

| β (No) (n = 162) | β (Yes) (n = 245) | β (Yes)–β (No) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 PU → BI | 0.404 | 0.457 | 0.052 | 0.569 |

| H2 PEOU → BI | −0.031 | 0.263 | 0.293 | 0.000 |

| H3 PEOU → PU | 0.134 | 0.131 | −0.003 | 0.973 |

| H4 TRST → BI | 0.487 | 0.254 | −0.234 | 0.026 |

| H5 TRST → PEOU | 0.412 | 0.401 | −0.011 | 0.892 |

| H6 TRST → PU | 0.567 | 0.379 | −0.188 | 0.059 |

| H7 KNW → TRST | 0.119 | 0.240 | 0.121 | 0.074 |

| H8 KNW → PU | 0.003 | 0.061 | 0.058 | 0.334 |

| H9 PR → PU | −0.153 | −0.208 | −0.055 | 0.546 |

| H10 PR → TRST | −0.609 | −0.580 | 0.028 | 0.687 |

| H11 FE → PU | 0.241 | 0.181 | −0.059 | 0.407 |

| H12 PIIT → PEOU | 0.156 | 0.289 | 0.132 | 0.179 |

Note. BI = behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts, PU = perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts, PEOU = perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts, TRST = trust in legal technologies, KNW = knowledge about legal technologies, PR = perceived risk of legal technologies in courts, FE = fairness expectations for legal technologies in courts, and PIIT = personal innovativeness in information technology; statistically significant R2 coefficients appear in bold.

Table A4.

Multigroup analysis by age (18–39 y. vs. > 40 y.).

Table A4.

Multigroup analysis by age (18–39 y. vs. > 40 y.).

| Hypothesis | β (18–39) (n = 236) | β (>40) (n = 149) | β (18–39)–β (>40) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 PU → BI | 0.419 | 0.488 | −0.068 | 0.495 |

| H2 PEOU → BI | 0.110 | 0.240 | −0.130 | 0.126 |

| H3 PEOU → PU | 0.088 | 0.189 | −0.100 | 0.251 |

| H4 TRST → BI | 0.405 | 0.192 | 0.213 | 0.064 |

| H5 TRST → PEOU | 0.354 | 0.497 | −0.143 | 0.128 |

| H6 TRST → PU | 0.439 | 0.555 | −0.116 | 0.204 |

| H7 KNW → TRST | 0.143 | 0.219 | −0.076 | 0.274 |

| H8 KNW → PU | 0.087 | −0.053 | 0.140 | 0.030 |

| H9 PR → PU | −0.162 | −0.148 | −0.014 | 0.882 |

| H10 PR → TRST | −0.607 | −0.606 | −0.001 | 0.999 |

| H11 FE → PU | 0.238 | 0.160 | 0.079 | 0.291 |

| H12 PIIT → PEOU | 0.224 | 0.280 | −0.056 | 0.577 |

Note. BI = behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts, PU = perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts, PEOU = perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts, TRST = trust in legal technologies, KNW = knowledge about legal technologies, PR = perceived risk of legal technologies in courts, FE = fairness expectations for legal technologies in courts, and PIIT = personal innovativeness in information technology; statistically significant R2 coefficients appear in bold.

Table A5.

Multigroup analysis by gender (male vs. female).

Table A5.

Multigroup analysis by gender (male vs. female).

| Hypothesis | β (Female) (n = 245) | β (Male) (n = 153) | β (Female)–β (Male) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 PU → BI | 0.445 | 0.458 | −0.013 | 0.884 |

| H2 PEOU → BI | 0.173 | 0.088 | 0.085 | 0.293 |

| H3 PEOU → PU | 0.112 | 0.131 | −0.020 | 0.827 |

| H4 TRST → BI | 0.285 | 0.406 | −0.121 | 0.249 |

| H5 TRST → PEOU | 0.370 | 0.485 | −0.115 | 0.230 |

| H6 TRST → PU | 0.405 | 0.522 | −0.117 | 0.213 |

| H7 KNW → TRST | 0.231 | 0.147 | 0.084 | 0.198 |

| H8 KNW → PU | 0.017 | 0.058 | −0.041 | 0.540 |

| H9 PR → PU | −0.228 | −0.154 | −0.074 | 0.421 |

| H10 PR → TRST | −0.553 | −0.649 | 0.095 | 0.168 |

| H11 FE → PU | 0.247 | 0.172 | 0.076 | 0.305 |

| H12 PIIT → PEOU | 0.281 | 0.164 | 0.117 | 0.249 |

Note. BI = behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts, PU = perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts, PEOU = perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts, TRST = trust in legal technologies, KNW = knowledge about legal technologies, PR = perceived risk of legal technologies in courts, FE = fairness expectations for legal technologies in courts, and PIIT = personal innovativeness in information technology.

Table A6.

Comparison of coefficients of determination (R2) in models by groups: legal profession, court experience, gender, and age.

Table A6.

Comparison of coefficients of determination (R2) in models by groups: legal profession, court experience, gender, and age.

| BI | PEOU | PU | TRST | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The proposed model | R2 (overall) | 0.648 | 0.296 | 0.536 | 0.412 |

| Legal profession | R2 (legal) | 0.665 | 0.198 | 0.510 | 0.528 |

| R2 (other) | 0.647 | 0.360 | 0.551 | 0.374 | |

| R2 (legal)–R2 (other) | 0.018 | −0.162 | −0.042 | 0.154 | |

| p-value | 0.764 | 0.048 | 0.577 | 0.048 | |

| Court experience | R2 (yes) | 0.667 | 0.335 | 0.474 | 0.438 |

| R2 (no) | 0.674 | 0.241 | 0.643 | 0.413 | |

| R2 (yes)–R2 (no) | −0.006 | 0.094 | −0.169 | 0.025 | |

| p-value | 0.900 | 0.257 | 0.022 | 0.765 | |

| Gender | R2 (female) | 0.580 | 0.288 | 0.483 | 0.394 |

| R2 (male) | 0.743 | 0.329 | 0.622 | 0.482 | |

| R2 (female)–R2 (male) | −0.163 | −0.040 | −0.139 | −0.088 | |

| p-value | 0.005 | 0.634 | 0.063 | 0.279 | |

| Age | R2 (18–39 years) | 0.637 | 0.225 | 0.485 | 0.427 |

| R2 (>40 years) | 0.679 | 0.451 | 0.666 | 0.441 | |

| R2 (18–39 y.)–R2 (>40 y.) | −0.042 | −0.226 | −0.181 | −0.014 | |

| p-value | 0.476 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.867 |

Note. BI = behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts, PU = perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts, PEOU = perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts, and TRST = trust in legal technologies; statistically significant R2 coefficients appear in bold.

Table A7.

Cross-tabulation of the study sample.

Table A7.

Cross-tabulation of the study sample.

| Legal | Other | χ2 | No | Yes | χ2 | Male | Female | χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 23.4% (34) | 49.2% (128) | 25.78 ** | |||||||

| Yes | 76.6% (111) | 50.8% (132) | ||||||||

| Male | 41.4% (58) | 36.3% (93) | 0.998 | 35.0% (56) | 40.8% (97) | 1.340 | ||||

| Female | 58.6% (82) | 63.7% (163) | 65.0% (104) | 59.2% (141) | ||||||

| 18–39 y. | 82.7% (115) | 48.8% (119) | 42.97 ** | 67.9% (108) | 56.6% (128) | 5.012 * | 65.0% (93) | 57.9% (135) | 1.869 | 100% (236) |

| >40 y. | 17.3% (24) | 51.2% (125) | 32.1% (51) | 43.4% (98) | 35.0% (50) | 42.1% (98) | 100% (146) | |||

| 100% (145) | 100% (260) | 100% (162) | 100% (246) | 100% (153) | 100% (245) |

** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05.

Table A8.

Comparison of means between groups.

Table A8.

Comparison of means between groups.

| Profession | Legal | Other | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p-value | |

| BI | 4.68 | 1.79 | 4.56 | 1.59 | 0.766 | 402 | 0.444 |

| PEOU | 4.25 | 1.65 | 4.31 | 1.53 | −0.227 | 403 | 0.820 |

| PU | 4.98 | 1.57 | 5.24 | 1.52 | −1.566 | 403 | 0.118 |

| TRST | 4.51 | 1.63 | 4.83 | 1.47 | −1.954 | 403 | 0.052 |

| FE | 6.23 | 1.14 | 5.97 | 1.22 | 2.341 | 402 | 0.020 |

| PR | 3.55 | 1.63 | 3.45 | 1.66 | 0.127 | 402 | 0.899 |

| PIIT | 5.34 | 1.45 | 5.14 | 1.53 | 1.156 | 403 | 0.248 |

| KNW | 2.06 | 1.09 | 1.67 | 0.83 | 4.324 | 403 | 0.000 |

| COURT EXPERIENCE | YES | NO | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p-value | |

| BI | 4.93 | 1.49 | 4.66 | 1.57 | 1.736 | 404 | 0.083 |

| PEOU | 3.97 | 1.38 | 3.88 | 1.32 | 0.702 | 405 | 0.483 |

| PU | 5.3 | 1.32 | 5.31 | 1.38 | −0.583 | 405 | 0.560 |

| TRST | 4.55 | 1.38 | 4.60 | 1.43 | −0.349 | 405 | 0.727 |

| FE | 6.14 | 1.08 | 6.16 | 1.07 | −0.150 | 404 | 0.881 |

| PR | 3.95 | 1.43 | 4.04 | 1.35 | −0.655 | 404 | 0.513 |

| PIIT | 4.70 | 1.42 | 4.43 | 1.42 | 1.867 | 405 | 0.063 |

| KNW | 1.78 | 0.81 | 1.50 | 0.61 | 3.747 | 405 | 0.000 |

| AGE | 18–39 | >40 | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p-value | |

| BI | 4.85 | 1.52 | 4.77 | 1.54 | 0.474 | 382 | 0.636 |

| PEOU | 3.94 | 1.34 | 3.87 | 1.39 | 0.455 | 383 | 0.650 |

| PU | 5.34 | 1.27 | 5.14 | 1.46 | 1.395 | 383 | 0.164 |

| TRST | 4.63 | 1.42 | 4.31 | 1.39 | 0.813 | 383 | 0.416 |

| FE | 6.36 | 0.91 | 5.94 | 1.19 | 3.884 | 382 | 0.000 |

| PR | 4.00 | 1.31 | 4.00 | 1.55 | 0.018 | 382 | 0.986 |

| PIIT | 4.70 | 1.39 | 4.42 | 1.47 | 1.881 | 383 | 0.061 |

| KNW | 1.73 | 0.75 | 1.58 | 0.77 | 1.905 | 383 | 0.058 |

| GENDER | MALE | FEMALE | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p-value | |

| BI | 4.78 | 1.60 | 4.82 | 1.47 | −0.209 | 396 | 0.835 |

| PEOU | 3.99 | 1.39 | 3.88 | 1.34 | 0.768 | 396 | 0.443 |

| PU | 5.05 | 1.51 | 5.39 | 1.22 | −2.339 | 396 | 0.014 |

| TRST | 4.51 | 1.54 | 4.59 | 1.28 | −0.555 | 395 | 0.579 |

| FE | 6.18 | 1.04 | 6.12 | 1.11 | 0.517 | 395 | 0.606 |

| PR | 3.83 | 1.43 | 4.03 | 1.37 | −0.682 | 395 | 0.496 |

| PIIT | 4.69 | 1.48 | 4.52 | 1.39 | 1.161 | 396 | 0.246 |

| KNW | 1.72 | 0.80 | 1.61 | 0.69 | 1.425 | 396 | 0.155 |

Note. BI = behavioral intention to use legal technologies in courts, PU = perceived usefulness of legal technologies in courts, PEOU = perceived ease of use of legal technologies in courts, TRST = trust in legal technologies, M = mean, SD = standard deviation, t = t-statistic, and df = degrees of freedom; statistically significant mean differences appear in bold.

References

- Abdul Jalil, Juriah, and Shukriah Mohd Sheriff. 2020. Legal Tech in Legal Service: Challenging the Traditional Legal Landscape in Malaysia. IIUM Law Journal 28: 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarie, Benjamin, Anthony Niblett, and Albert H. Yoon. 2018. How Artificial Intelligence Will Affect the Practice of Law. University of Toronto Law Journal 68 Suppl. 1: 106–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alda, Erik, Richard Bennett, Nancy Marion, Melissa Morabito, and Sandra Baxter. 2020. Antecedents of Perceived Fairness in Criminal Courts: A Comparative Analysis. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 44: 201–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammenwerth, Elske. 2019. Technology Acceptance Models in Health Informatics: TAM and UTAUT. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 263: 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballell, Teresa Rodríguez De Las Heras. 2019. Legal Challenges of Artificial Intelligence: Modelling the Disruptive Features of Emerging Technologies and Assessing Their Possible Legal Impact. Uniform Law Review 24: 302–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Bradford S., Ann Marie Ryan, Darin Wiechmann, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. 2004. Justice Expectations and Applicant Perceptions. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 12: 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Bradford S., Darin Wiechmann, and Ann Marie Ryan. 2006. Consequences of Organizational Justice Expectations in a Selection System. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 455–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benesh, Sara C. 2006. Understanding Public Confidence in American Courts. Journal of Politics 68: 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, Daniel W., and Margaret Hagan. 2020. Redesigning Justice Innovation: A Standardized Methodology. Stanford Journal of Civil Rights & Civil Liberties 16: 335–84. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, Reuben, Max van Kleek, Michael Veale, Ulrik Lyngs, Jun Zhao, and Nigel Shadbolt. 2018. ‘It’s Reducing a Human Being to a Percentage’; Perceptions of Justice in Algorithmic Decisions. Paper presented at the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, April 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blader, Steven L., and Tom R. Tyler. 2003. A Four-Component Model of Procedural Justice: Defining the Meaning of a ‘Fair’ Process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29: 747–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, Katie, Momori Hirabayashi, Clara Langevin, Bernardo Rivera Munozcano, Katsumi Sekizawa, and Jiayi Zhu. 2020. The Future of AI in the Brazilian Judicial System. Available online: https://itsrio.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/SIPA-Capstone-The-Future-of-AI-in-the-Brazilian-Judicial-System-1.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Brooks, Chay, Cristian Gherhes, and Tim Vorley. 2020. Artificial Intelligence in the Legal Sector: Pressures and Challenges of Transformation. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 13: 135–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Kevin S. 2020. Procedural Fairness Can Guide Court Leaders. Court Review 56: 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kevin S., and Steven Leben. 2020. Procedural Fairness in a Pandemic: It’s Still Critical to Public Trust. Drake Law Review 68: 685–706. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Andreas. 2012. UTAUT and UTAUT 2: A Review and Agenda for the Future Research. Journal The WINNERS 13: 106–14. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Jong Kyu, and Yong Gu Ji. 2015. Investigating the Importance of Trust on Adopting an Autonomous Vehicle. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 31: 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, Olenaand, Katerina Berezina, and Minsoo Kang. 2021. Effect of Personal Innovativeness on Technology Adoption in Hospitality and Tourism: Meta-Analysis. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021. Edited by Jason L. Stienmetz, Wolfgang Wörndl and Chulmo Koo. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 162–74. [Google Scholar]

- Clothier, Reece A., Dominique A. Greer, Duncan G. Greer, and Amisha M. Mehta. 2015. Risk Perception and the Public Acceptance of Drones. Risk Analysis 35: 1167–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, Jason A. 2001. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Fred D. 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems 13: 319–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Fred D. 2014. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/35465050 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Davis, Fred D., Richard P. Bagozzi, and Paul R. Warshaw. 1989. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Management Science 35: 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cremer, David, and Tom R. Tyler. 2007. The Effects of Trust in Authority and Procedural Fairness on Cooperation. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 639–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, James W., and Jeffrey G. Cox. 2018. Diffusion of Innovations Theory, Principles, and Practice. Health Affairs 37: 183–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, Ashley. 2019. The Judicial Demand for Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Columbia Law Review 119: 1829–50. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26810851 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Dhagarra, Devendra, Mohit Goswami, and Gopal Kumar. 2020. Impact of Trust and Privacy Concerns on Technology Acceptance in Healthcare: An Indian Perspective. International Journal of Medical Informatics 141: 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirsehan, Taşkın, and Ceren Can. 2020. Examination of trust and sustainability concerns in autonomous vehicle adoption. Technology in Society 63: 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, Christophe. 2021. How Do Lawyers Engineer and Develop LegalTech Projects? A Story of Opportunities, Platforms, Creative Rationalities, and Strategies. Law, Technology and Humans 3: 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Bireswar, Mei Hui Peng, and Shu Lung Sun. 2018. Modeling the Adoption of Personal Health Record (PHR) among Individual: The Effect of Health-Care Technology Self-Efficacy and Gender Concern. Libyan Journal of Medicine 13: 1500349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejdys, Joanna. 2018. Building technology trust in ICT application at a university. International Journal of Emerging Markets 13: 980–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, Christoph, and Nina Grgić-Hlača. 2021. Machine Advice with a Warning about Machine Limitations: Experimentally Testing the Solution Mandated by the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Journal of Legal Analysis 13: 284–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, Sarah D., Stephanie Denison, and Ori Friedman. 2021. The Computer Judge: Expectations about Algorithmic Decision-Making. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 43: 1991–96. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1866q7s7 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- European Judicial Network. 2019. How to Bring a Case to Court. Lithuania. Available online: https://e-justice.europa.eu/home?action=home&plang=en (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Fabri, Marco. 2021. Will COVID-19 Accelerate Implementation of ICT in Courts? International Journal for Court Administration 12: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqih, Khaled M.S., and Mohammed Issa Riad Mousa Jaradat. 2015. Assessing the Moderating Effect of Gender Differences and Individualism-Collectivism at Individual-Level on the Adoption of Mobile Commerce Technology: TAM3 Perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 22: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, Mauricio S., and Paul A. Pavlou. 2003. Predicting E-Services Adoption: A Perceived Risk Facets Perspective. International Journal of Human Computer Studies 59: 451–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Guangchao Charles, Xianglin Su, Zhiliang Lin, Yiru He, Nan Luo, and Yuting Zhang. 2021. Determinants of Technology Acceptance: Two Model-Based Meta-Analytic Reviews. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 98: 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Katherine. 2016. Algorithmic Injustice: How the Wisconsin Supreme Court Failed to Protect Due Process Rights in State v. Loomis. North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology 18: 75–106. [Google Scholar]

- Galib, Mohammad Hasan, Khalid Ait Hammou, and Jennifer Steiger. 2018. Predicting Consumer Behavior: An Extension of Technology Acceptance Model. International Journal of Marketing Studies 10: 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, David, and Elena Karahanna und Detmar W Straub. 2003. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Quarterly 27: 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasinghe, Asanka, Junainah Abd Hamid, Ali Khatibi, and S. M. Ferdous Azam. 2020. The Adequacy of UTAUT-3 in Interpreting Academician’s Adoption to e-Learning in Higher Education Environments. Interactive Technology and Smart Education 17: 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Meirong. 2021. Internet Court’s Challenges and Future in China. Computer Law and Security Review 40: 105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F. 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equations Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanham, José, Chwee Beng Lee, and Timothy Teo. 2021. The Influence of Technology Acceptance, Academic Self-Efficacy, and Gender on Academic Achievement through Online Tutoring. Computers and Education 172: 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, Imane, Razane Chroqui, Chafik Okar, Mohamed Talea, and Ahmed Ouiddad. 2017. Literature Review: All about IDT and TAM. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317106305_Literature_review_All_about_IDT_and_TAM (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Hauenstein, Neil M. A., Tim Mcgonigle, and Sharon W. Flinder. 2001. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Procedural Justice and Distributive Justice: Implications for Justice Research. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 13: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, Deborah. 2020. Measuring Algorithmic Fairness. Virginia Law Review 106. Available online: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2019/02/aoc-algorithms-racist-bias.html (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Hongdao, Qian, Sughra Bibi, Asif Khan, Lorenzo Ardito, and Muhammad Bilawal Khaskheli. 2019. Legal Technologies in Action: The Future of the Legal Market in Light of Disruptive Innovations. Sustainability 11: 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Chi Yo, Hui Ya Wang, Chia Lee Yang, and Steven J.H. Shiau. 2020. A derivation of factors influencing the diffusion and adoption of an open source learning platform. Sustainability 12: 7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhsan, Khairul. 2020. Technology Acceptance Model, Social Influence and Perceived Risk in Using Mobile Applications: Empirical Evidence in Online Transportation in Indonesia. Jurnal Dinamika Manajemen 11: 127–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoski-Haehlen, Emily. 2019. Robots, Blockchain, ESI, Oh My!: Why Law Schools Are (or Should Be) Teaching Legal Technology. Legal Reference Services Quarterly 38: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]