Abstract

This article focuses on the structure of female and male crimes and gender disparities in sentencing in Lithuania, which present a significant gap in criminological research. Using Lithuanian court decisions on five types of offenses—murder, grievous bodily harm, actual bodily harm, drug distribution, and theft—we attempt to answer whether women are punished more leniently than men. Our research demonstrates that gender is a significant factor only in some sentences. Only the length of a prison sentence showed a statistically significant difference. When the importance of legal and extralegal factors in imposing prison length is compared, legal factors are found to be more significant predictors. The prison sentence length was mainly affected by the presence of a prior conviction, additional charges, and mitigating and aggravating circumstances. Although the average prison sentence for men in cases of grievous bodily harm and drug distribution was significantly longer than for women, the regression models developed for each offence type revealed that neither gender nor other extralegal factors appeared to be significant in determining the length of the prison sentence. The results allow us to argue that future research should focus more on analyzing extralegal factors and judges’ motives in discretionary sentencing decisions.

1. Introduction

Gender disparities in sentencing have been widely discussed in criminological literature. However, somewhat contradictory results of previous research (Gelsthorpe and Sharpe 2015) point to the need for a further discussion focused on new empirical data. Debates on different sentencing practices of women continue; scholars call for more comprehensive analyses (see Chatsverykova 2017; Pina-Sanchez and Harris 2020) or more profound research into the impact and effectiveness of various forms of punishment (see Hedderman and Barnes 2015; Birkett 2016).

The possible causes of gender disparities in sentencing have been explained using various theoretical arguments and empirical data. A large body of empirical literature demonstrates that female defendants are treated more leniently than male defendants (Hedderman and Gelsthorpe 1997; Curry et al. 2004; Chatsverykova 2017; Pina-Sanchez and Harris 2020). Women are less likely to receive custodial sentences or serve long prison terms (Chatsverykova 2017; Nowacki 2020; Freiburger and Hilinski 2013; Koons-Witt et al. 2014). Women’s lenient sentencing is explained by the difference in criminal records of male and female defendants, namely the severity of offenses committed by men and women or the differences in aggravating circumstances. Male defendants tend to commit more serious offences (Doerner and Demuth 2014, p. 244; see also Griffin and Wooldredge 2006; Cho and Tasca 2019), and they could be punished more harshly because of a previous history of more serious offenses (Pina-Sanchez and Harris 2020). The extralegal factors such as the presence of children, marital status, and financial situation or employment could also impact sentencing decisions (Tillyer et al. 2015). Traditionally, female offenses such as stealing food and clothing have been associated with a lower level of guilt and have long been associated with domestic and family responsibilities as a mitigating factor (Birkett 2016). However, more ‘masculine’ female criminal behavior may be viewed as more inappropriate and deserving harsher punishment (Spohn 1999; Bontrager et al. 2013). Therefore, empirical research strengthens the arguments of double deviance theory, according to which women are viewed as doubly deviant, i.e., those who violate both the law and gendered norms (Carlen 2013; Heidensohn and Silvestri 2012). It allows researchers to assume that women’s sentences may be influenced not only by legal (seriousness of offense or criminal history) and extralegal (having children or dependents, financial situation, or employment) factors but also by the context of gendered norms and expectations.

It is necessary to constantly test all these theoretical and empirical explanations because of the dramatic change in women’s sentencing, particularly custodial sentences imposed on them, during the last thirty years worldwide. At the turn of the century, an increase in incarcerated women reflected a change in female punishment in different Western countries (Malloch and McIvor 2013). For example, the number of women imprisoned in England and Wales doubled in the early 1990s, and the main reason for this jump was not a change in women’s criminal behavior, but an intensified criminal justice response to women’s crime (Hedderman 2004; Hedderman and Barnes 2015). Increased custodial sentences for women are also noticeable worldwide, with the total population of prisoners growing by about 20 percent and that of women prisoners by 50 percent between 2005 and 2015 (Walmsley 2015). In 2017, more than 700,000 women were serving prison sentences worldwide, a 53.3 percent increase in the total population of women in prison since 2000. The number of women imprisoned in Europe increased by 3.5 percent between 2000 and 2017 and was almost the same as the overall increase in the prison population, which stood at 3.7 percent over the period (Walmsley 2017).

According to the statistics on women’s criminal offenses in Lithuania, the share of women in registered criminal offenses has not changed significantly over the last ten years—in 2010, it was 12.6 percent and in 2019, 10.9 percent. The absolute number of suspected women decreased similarly, with an average of 3584 suspects registered per year in 2011–2015 and 2764 women in 2015–2020. In 2015–2020, most women (664) were suspected of property crimes (Art. 178–189 of the Criminal Code, hereafter CC) (Criminal Code of the Republic of Lithuania 2000) and bodily harm (Art. 135–140 of the CC)—an average of 776 per year. Women charged with committing these crimes accounted for more than half of all charged women between 2015 and 2020. The number of women charged with property crimes has been declining in the last decade, as has the number of women charged with drug-related crimes in the last five years. However, both the absolute number of women charged and the percentage of women charged with bodily injury have increased. Although it is observed that more women commit violent crimes (Michailovič 2014), it is important to note that about 90 percent of women are charged with the infliction of bodily pain (Art. 140 of the CC) and that the percentage of men charged with the same crime (Ch. XVIII of the CC) is twice as high as that of women, 20 percent and 10 percent, respectively (Information Technology and Communications Department 2021). Moreover, women tend to commit more crimes that can be attributed to a woman’s social roles or position (for instance, the abuse of rights or responsibilities of a parent, guardian or caregiver or another legal representative of a child, fraudulent bookkeeping, and illegal alcohol production).

Concerning the imprisonment of women, it is essential to mention that from 2004 to 2012, the share of women imprisoned in Lithuania almost doubled (slightly more than 40 percent). However, since 2012 this number has been declining with some fluctuations. The proportion of women incarcerated increased from 3.2 percent in 2004 to 5 percent in 2017. Although the total number of imprisoned persons has decreased by 34.2 percent in the last ten years, the share of imprisoned women has remained relatively stable. The average proportion of women in prison was 4.6 percent and is very close to the European average of 4.7 percent of all prisoners in 2020. However, at the start of 2020, Lithuania remained the country with the highest incarceration rates in the European Union, with 220 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants (Aebi and Tiago 2020). As it has been repeatedly stated, one of the primary reasons for Lithuania’s high prison population is not only the frequent use of imprisonment but also the average length of imprisonment (both imposed by the courts and actually served). The average prison sentence imposed by Lithuanian courts between 2016 and 2018 was the longest of the entire 20-year period from 1998 to 2018, at 80 months, representing a more than 50 percent increase since 2002, and the actually served sentence was also the longest, consisting of 32 months, in 2016. (Sakalauskas et al. 2020). It shows that sentencing trends with particular attention to the length of sentences require a deeper analysis.

Furthermore, gender has never been identified as a significant variable in sentencing research in Lithuania, although some aspects of male and female criminal behavior, including men’s and women’s involvement in the criminal justice system, have previously been controlled (Michailovič 2014; Sakalauskas et al. 2020). Moreover, there is no statistical sentencing data available in Lithuania that includes various offending and sentencing characteristics, and there exists a significant gap in empirical evidence on sentencing practices of men and women. Thus, this article is the first attempt to analyze differences in sentencing between male and female defendants in Lithuania taking into account various legal and extralegal factors. It contributes to research that identifies women’s and men’s sentencing differences and formulates new assumptions related to these differences.

2. Gender and Sentencing: An Overview

Several theoretical perspectives, including the chivalry theory (Herzog and Oreg 2008; Brielle 2016), the judicial paternalism perspective (Belknap 2021; see also Nowacki 2020, p. 675), and the focal concerns perspective (Steffensmeier et al. 1998; Steffensmeier and Demuth 2006), have been used to explain gender disparities in sentencing.

According to the chivalry theory, the judges’ decisions reflect their perception that women are less threatening, dangerous, and guilty than men (Rodriguez et al. 2006, p. 320) as well as weak and in need of protection. It is also believed that women’s criminality is often the result of their victimization, such as their destructive relationships with men or drug use (Steffensmeier and Demuth 2006, p. 246). The chivalry hypothesis also includes the concept of selective chivalry, or the evil woman thesis, that attempts to explain women’s transgressions of traditional gender roles and responses to them (Embry and Lyons 2012; Spivak et al. 2014; Tillyer et al. 2015). According to this thesis, women who break the traditional gender roles are expected to receive more severe punishment for their crimes.

Women are prosecuted equally or even as harshly as males in cases of ‘masculine’ violent actions but are handled protectively and leniently if they are charged with ‘female’ offenses (Chatsverykova 2017). Researchers note that crimes perceived as female-oriented, such as shoplifting, are often viewed more leniently than those that are more associated with men’s criminal behavior (Birkett 2016; Spohn 1999; Bontrager et al. 2013). Thus, women who do not submit to informal control, whether in the family, social relationships, or welfare institutions, receive harsher punishment as they are being punished both for the offence committed and socially unacceptable gender behavior (Carlen 2013).

This theory is closely related to the focal concerns perspective which explains gender effects in sentencing by judges’ assessments of offenders’ liability and blameworthiness, their danger to public safety and the consequences of their sentences (Steffensmeier et al. 1998). This perspective considers factors such as the seriousness of the offence, the defendant’s criminal history, and the likelihood of reoffending. Judges use preconceptions based on the defendant’s age, gender, race, and socioeconomic background to reduce uncertainty in their sentencing decisions (Griffin and Wooldredge 2006).

Empirical studies that specifically analyze judges’ motives suggest that defendants’ social and family circumstances are more likely to play a more important role in sentencing women than men. This approach is developed from the perspective of judicial paternalism (Belknap 2021; Nowacki 2020), primarily based on women’s traditional familial roles. For instance, mothers tend to be sentenced more leniently than men and women without children (Pierce 2013; Cho and Tasca 2019). Daly referred to it as family-based justice, in which judges attempt to protect families from losing sources of care and economic support. Because court officials see more ‘good’ mothers than ‘good’ fathers, female defendants with children receive more compassionate sentencing (Daly and Tonry 1997; Chatsverykova 2017).

All these perspectives are based on similar arguments related to stereotypical gender roles and relations (for instance, the assumption that criminal offences are more natural for men than women) and gender-biased decisions regarding sentencing within the court system (Curry et al. 2004, p. 325). According to most studies following these perspectives, women’s sentences are more lenient than men’s, i.e., gender bias in courts is beneficial for women (Curry et al. 2004; Doerner and Demuth 2010; Doerner and Demuth 2014; Nowacki 2020). However, there is a lack of empirical evidence on the differential treatment of men and women in terms of prison sentence length. As it has been argued, the factors that influence judges’ decisions on women’s sentences might be weighted differently as far the sentence length is concerned (Rodriguez et al. 2006; Cho and Tasca 2019, p. 421). Moreover, the studies on gender disparities in sentencing do not always consider the content of women’s and men’s crimes, their criminal biographies and all relevant extralegal characteristics. For instance, previous research shows that female and male offenders with low social integration (unemployed, single, non-citizens, and non-locals) are more likely to be incarcerated and generally receive longer sentences (Chatsverykova 2017). As a result, a non-exhaustive list of circumstances could influence the sentence of women and men. Furthermore, it is rarely explained whether the gender aspect is relevant only to certain crimes and how it works in sentencing for different crimes (Mustard 2001; Koons-Witt 2002). It is especially evident when assessing more serious crimes (Daly and Tonry 1997, pp. 230–31).

Hence, empirically identifying discrimination in sentencing is a challenging research question. The evidence of gender disparities in sentencing may be influenced by research limitations, insufficient statistical controls, and access to all the relevant legal and extralegal characteristics (Kruttschnitt and Savolainen 2009; Pina-Sanchez and Harris 2020). Kruttschnitt and Savolainen’s (2009) research in Finland found that gender did not affect the decision to incarcerate, regardless of other social or legal case factors. Their findings suggest that shifts in society’s gender order, such as greater gender equality in labor, family-friendly policies, and cultural context, should be considered, as they may reduce gender disparities in sentencing. Therefore, a specific country’s changeable societal environment should be taken into account while analyzing sentencing inequalities.

To sum up, in supporting the traditional discourse of gender roles in the criminal justice process, women are more often seen as having problems and men as causing problems. However, it is less important that women and men are punished equally; it is more crucial to ensure that all social content related to criminal behavior, including all relevant social circumstances, is treated equally in sentencing (Hedderman and Gelsthorpe 1997, pp. 55–56). At the same time, it is not so important to answer whether female and male defendants should be sentenced differently but rather to discuss the preconditions of particular punishment tendencies and how these preconditions can be evaluated.

3. Methodology

The empirical data of this study are based on an analysis of Lithuanian court decisions obtained from the E-service Portal of Lithuanian Courts (LITEKO), which contains all court sentences announced by the state. The period covered one year, from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2018. Because there are no statistical sentencing data or empirical research revealing sentencing tendencies in Lithuania, we intended to identify sentencing patterns of the various types of offenses. Over the last decade (2011–2020), the majority of men and women were suspected of property crimes, bodily harm, drug offenses, and traffic safety violations. As a result, we chose the most commonly reported types of crimes; only offenses against traffic safety were excluded from the analysis due to their distinct characteristics. Hence, property, bodily harm, and drug offenses were studied, and specific offenses from each category were chosen. We chose theft (art. 178) as the most commonly reported type of property crime. The two types of offenses were selected from the bodily harm category—grievous bodily harm (art. 135) and actual bodily harm (art. 138)—in order to cover both more severe and more lenient types of offenses, and murder (art. 129) as the most severe type of offense was also added to the analysis. Drug distribution (art. 260) was also chosen as the most frequently registered offense resulting from drug-related crimes. Hence, the five types of offenses: murder (art. 129), grievous bodily harm (art. 135), actual bodily harm (art. 138), drug distribution (art. 260), and theft (art. 178) were chosen, and separate data searches were carried out for male and female defendants.

Because we chose the most commonly reported types of offenses, it is possible that they reflect crime trends in the general population. However, the analysis did not include all court decisions made in 2018 on the above-mentioned types of offense, but a representative sample was chosen for each offense. Table 1 displays the total number of selected offenses committed in 2018 and the specific number of verdicts chosen for further analysis. The required number of cases was first calculated to obtain a representative sample for each offense, and then simple random sampling was performed. Some cases were discarded during the analysis due to their unsuitability for further examination. The final female sample contained 239 court decisions, whereas the male sample contained 1035 court decisions. Because we used a simple random sampling strategy, there is no way to compare selected samples to the general population, which could be considered a limitation of the study.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

The sample characteristics suggest that violent criminal offenses were more prevalent in the male sample, while women were more prone to be involved in drug distribution and property crime. According to the official national statistics, selected offenses such as property crimes, offenses against people’s health, and drug distribution predominate in both male and female criminal offenses (Tereškinas et al. 2021, pp. 26–28).

No statistical sentencing data are available in Lithuania that include various offending and sentencing characteristics. A 154-item questionnaire with coding instructions was developed, and selected court decisions on 239 women and 1035 men were analyzed using the questionnaire. The questionnaire was divided into six subsets that covered various relevant information, such as administrative case details, defendant’s sociodemographic characteristics, defendant’s criminal history, victim’s characteristics, mitigating and aggravating circumstances, substance abuse, and sentence characteristics. Since this particular study sought to compare the sentencing trends of female and male offenders, further data analysis was limited only to the defendants’ criminal history, mitigating and aggravating circumstances, and other extralegal sentence characteristics (such as having children). The lack of a sentencing dataset in Lithuania and the small number of court decisions analyzed by the research team influenced the research limitations. The statistical analysis was also limited by the number of court decisions included in the study and the lack of control over all relevant factors. The inability to control all relevant factors determined the research strategy.

Our analytical strategy was developed in response to recent research on sentencing consistency and the importance of relevant legal and extralegal (non-legal) factors (Cho and Tasca 2019; Chatsverykova 2017; Pina-Sanchez 2013; Pina-Sanchez and Linacre 2014; Sanchez and Harris 2020). When selecting legal factors, we focused on statutory legal factors defined in sentencing guidelines that were present in researched cases. Extralegal factors, defined as demographic factors and personal circumstances to be considered when deciding on a sentence (Pina-Sanchez 2013), were also limited by the available data in the analyzed cases.

Before the data analysis, we should emphasize that general sentencing guidelines in Lithuania are presented in Article 54 of the CC of the Republic of Lithuania. According to them, the type and length of sentence for each specific offence should correspond to the one specified in the relevant article of the CC. Each article specifies a minimum and maximum (sometimes only maximum) sentence for a specific offense. The minimum and maximum sentence means are set as a starting point for further sentence determination. Article 54 also specifies a list of additional factors that must be considered before deciding on the final sentence. The nature and severity of the crime committed, the offender’s personality, the presence of mitigating and aggravating circumstances, the extent of the harm caused, and other factors should all be considered by the judge. Although the Criminal Procedure Code in Lithuania allows judges to initiate a pre-sentencing evaluation procedure requesting social inquiry reports, such attempts have been relatively rare in local court practice (Michailovič and Girdauskas 2016). As a result, rather than using deeper information collected through pre-sentence reports, sentencing is often tailored based solely on case information. Furthermore, as observed in previous research, Lithuania has a harsh punitive tone that is still characterized by a punitive culture inherited from the Soviet period, as evidenced by high incarceration rates and the dominance of long-term sentences (Sakalauskas 2016; Sakalauskas et al. 2020).

4. Results

4.1. Sentencing Trends for Male and Female Defendants

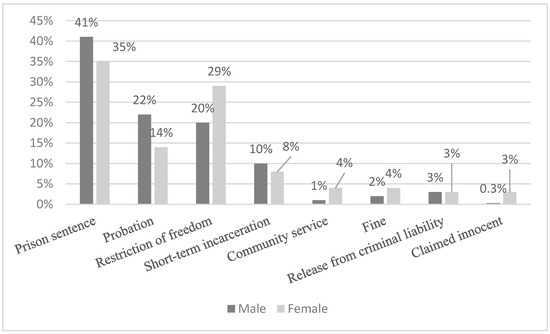

In general, prison sentence, probation1, and restriction of freedom2 were the most prevalent types of sentences in both male and female samples. Prison sentence, as well as probation and short-term incarceration, were more prevalent in the male sample. The restriction of freedom, as well as community service and fine, were more frequent among female defendants. In addition, women were found innocent more often compared to men (see Figure 1). However, as previously stated, violent criminal offenses were more common in the male sample, whereas drug distribution and property crime were more common in the female sample. Because these three types of sentences were the most common in both samples, the following analysis is limited to probation, restriction of freedom, and prison sentence3.

Figure 1.

The comparison of sentence types between male and female defendants (Chi-squared = 48, p < 0.001; ϕ = 0.194, p < 0.001; N = 1274).

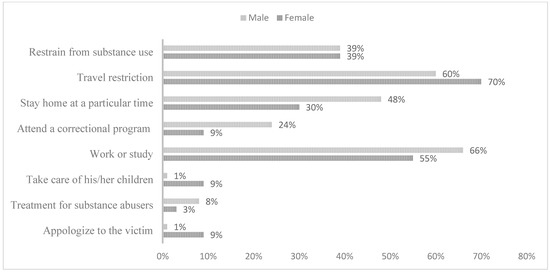

The analysis of conditions imposed along with the probation sentence and the sentence of restriction of freedom revealed statistically significant differences between conditions imposed on men and conditions imposed on women. Women were more often than men obliged to apologize to the victim (χ2 = 5, p = 0.03), and take care of their children (χ2 = 6, p = 0.01). There were also more tendencies observed: men were more likely than women to be required to treat addiction, to take part in a behavioral correction program, to start work or study, and women were more likely to be required not to leave their place of residence (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Probation conditions imposed on men and women.

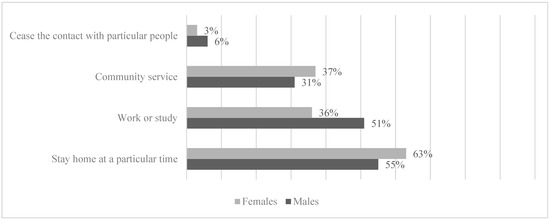

A comparison of conditions imposed along with the restriction of freedom shows that men sentenced to imprisonment were significantly more likely than women to be obliged to start work or study (χ2 = 4, p = 0.03). In addition, the study results show that women sentenced to the restriction of freedom were more likely than men to be required not to leave their homes at a particular time and be involved in community service. Men, meanwhile, were slightly more likely than women to be required not to interact with particular individuals (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Conditions imposed along with the restriction of freedom.

As a result of the analysis, it is possible to conclude that women are more likely to be set with conditions that correspond to traditional gender roles (preservation of relationships and strong family ties, community service), whereas men are more likely to be set with conditions that target their criminogenic needs and involvement in the labor market.

4.2. A Comparison of the Average Sentence Length

The following analysis focuses solely on the three most common types of sentences and the average sentence length. Across the crime types explored, neither the average length of the probation term nor the average length of the restriction of freedom differed between male and female defendants (Table 2 and Table 3). With some exceptions, female defendants usually received shorter probation terms and shorter periods of restriction of freedom.

Table 2.

A comparison of probation terms for male and female defendants.

Table 3.

A comparison of the restriction of freedom imposed on male and female defendants.

Intergroup comparisons have shown some statistically significant differences between males and females regarding the average prison sentence they received in court (Table 4). The general tendency discovered during this study is that male defendants receive longer prison sentences regardless of the crime committed. However, statistically significant differences were determined only among the defendants accused of grievous bodily harm and drug distribution. Men received an average sentence of 46 months for grievous bodily harm, while women received an average sentence of 25 months (p = 0.005, Z = −2.8). In the case of drug distribution, the average sentence for men was 86 months, and for women—59 months (p = 0.02, Z = −2.3). Therefore, it could be assumed that for some criminal offences the defendant’s gender might have an impact on the length of the prison sentence imposed in court.

Table 4.

A comparison of prison sentence length imposed on male and female defendants.

It should be noted that gender might be not the only factor affecting the sentence length imposed in court. According to the results, such legal factors as a prior conviction, additional charges, and mitigating and aggravating circumstances might also influence the final court decision. The results show that the potential impact of the factors mentioned differs depending on the type of crime committed. As the presence of a prior conviction, additional charges, and mitigating and aggravating circumstances mainly affected the prison sentence length, further analysis is focused exclusively on this specific sentence category.

Separate regression models were developed for each offence type to answer whether gender and legal and extralegal factors predict the length of a prison sentence (Table 5)4. The choice of independent variables for the regression analysis was based on the results of previous studies (Pierce 2013; Cho and Tasca 2019; Chatsverykova 2017). Linear regression analysis was used to develop a regression model for each offence type. The model for drug distribution cases was significant (F = 8.60, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.47) and included both legal and extralegal factors. The model reveals that, in cases of drug distribution, the length of a prison sentence was predicted by the presence of additional charges (β = −0.31, p < 0.001), the absence of mitigating circumstances (β = 0.41, p < 0.001), and the presence of aggravating circumstances (β = −0.17, p = 0.05). Therefore, legal variables appeared to be the best predictors of the length of a prison sentence, while gender turned out to be not significant for those accused of drug distribution.

Table 5.

Linear regression models for each offence type.

After regression analysis for the cases of grievous bodily harm, the results showed that the only significant predictor was the presence of additional charges (β = −0.46, p < 0.001). The model was significant (F = 3.47, p = 0.002, R2 = 0.41); neither gender nor other extralegal or legal variables predicted the length of a prison sentence.

In cases of actual bodily harm, regression analysis revealed that only the absence of mitigating circumstances (β = 0.42, p = 0.002) was significantly associated with a longer prison sentence (F = 1.93, p = 0.06, R2 = 0.29). Gender, as well as other legal and extralegal factors, appeared not to be significant in terms of the sentence length imposed in court.

In cases of murder, the defendant’s gender was again an insignificant predictor of the final prison sentence. The regression analysis has shown that the length of a prison sentence imposed in court was predicted by the presence of mitigating circumstances and the history of the prior conviction (F = 2.76, p = 0.01, R2 = 0.33). The absence of mitigating circumstances predicted a longer prison sentence (β = 0.38, p = 0.003), while the presence of prior conviction also predicted a longer prison sentence (β = −0.25, p = 0.04). One of the predictors which indicated alcohol abuse problems did not reach statistical significance (β = 0.23, p = 0.07); however, there could be a tendency that the absence of alcohol abuse problems might indicate a longer prison sentence for those charged with murder.

Finally, the regression analysis for the cases of theft revealed that the length of a prison sentence was predicted by all legal factors while gender remained insignificant factor (F = 6.58, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.24). According to the model, the presence of additional charges (β = −0.33, p < 0.001) and aggravating circumstances (β = −0.18, p = 0.01) as well as the absence of mitigating circumstances (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) and prior conviction (β = 0.14, p = 0.03) were associated with a longer prison sentence.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Sentencing consistency is both a fundamental justice principle and a desirable quality of all legal systems, increasing transparency and predictability of sentencing practices and strengthening public trust in sentencing (Pina-Sanchez and Linacre 2014). However, there still exists a lack of empirical evidence related to sentencing consistency and different sentencing practices, particularly in Lithuania. By analyzing the sentencing of women and men, this study intended to fill this gap.

The comparison of the types of sentences imposed on male and female defendants demonstrates that men received greater prison sentences, probation, and short-term detention. Female defendants were more likely to face restrictions of freedom, community service and a fine. However, such tendencies could be determined by the type of offences: violent criminal offenses were more prevalent in the male sample, whereas drug distribution and property crime were more prevalent in the female sample, representing the overall criminal behavior tendencies.

Our research also shows that probation conditions and the restriction of freedom were imposed in accordance with traditional gender roles. Women were more often than men obliged to apologize to the victim and take care of her children, while men had to work and study, as well as to attend correctional programs. Similar results related to gender norms were attained in previous research in England and Wales, which had shown that women were more likely than men to have supervision and drug treatment requirements attached to community orders and suspended sentences. At the same time, they were less likely to be subject to the requirements of unpaid work and participation in accredited programs (Gelsthorpe and Sharpe 2015). Hence, our findings demonstrate the need for a more in-depth examination of the imposed conditions of community sanctions. As argued elsewhere (Hedderman and Barnes 2015), women who lack the necessary skills and social resources frequently experience difficulties observing conditions imposed in conjunction with community sanctions. Non-custodial conditions that are not tailored to the individual needs ensure women’s failure to comply with them, and the violations result in women’s imprisonment.

Although significant regional differences exist in sentencing practices, many countries worldwide punish repeat offenders more severely. The severity of their offence and their past criminal record can have a variety of distinct effects on the severity of their sentence (Roberts and Pina-Sanchez 2014). Our research findings demonstrate that the presence of a prior conviction, additional charges, and mitigating and aggravating circumstances mainly affected the length of the prison sentence. Comparing the significance of legal and extralegal factors in imposing prison length reveals that legal factors are more significant predictors. For example, when imposing a sentence for drug distribution, all legal factors may be considered, and three of four (the presence of additional charges, mitigating and aggravating circumstances) are considered in cases of theft. However, extralegal factors such as the presence of children, substance abuse, and physical health problems did not appear significant in terms of prison sentence length in any offence type. Only in drug distribution cases did offenders with diagnosed mental health problems receive significantly shorter prison sentences than those without these problems.

The analysis also shows that gender is a significant factor only in some sentences. A statistically significant difference appeared only in the length of a prison sentence; probation terms for men and women and the average length of the restriction of freedom did not differ between male and female defendants. Furthermore, only two types of criminal offenses had a statistically significant difference in prescribed prison terms for male and female defendants: grievous bodily harm and drug distribution. The average prison sentence for men was significantly longer than for women in cases of grievous bodily harm (average sentence for males—46 months and females—25) and drug distribution (for men—86 months, and for women—59 months). Previous research has discovered similar tendencies, such as male offenders being 2.8 times more likely to receive a custodial sentence and receiving 14.7 percent longer sentences than female offenders. However, these tendencies are only found in assault offenses. Such gender differences found by comparing violent offenses may be justified by the fact that male offenders are perceived to be more violent and hence pose a greater danger of harm to the public. Furthermore, more serious prior sentences of male defendants may result in more severe male sentencing (Sanchez and Harris 2020).

However, a more in-depth examination of prison sentences by developing separate regression models for each offence type revealed that neither gender nor other extralegal factors appeared to be significant in determining the length of the prison sentence. Only a few legal factors were found to be significantly predictive of sentence length in each offence type. For example, in cases of drug distribution, actual bodily harm, murder, and theft, mitigating circumstances were significant predictors, and prior conviction was a significant predictor in drug distribution, murder, and theft cases. Our findings support previous research (Nikartas and Jarutienė 2022) that the individualization of sentencing should be used more widely in Lithuania, taking into account factors other than only legal ones.

Although the regression analysis has produced few significant results in terms of extralegal predictors of a prison sentence length, some of the findings might have been affected by a rather small sample size, for instance, in the case of murder and grievous bodily harm, since these two samples included 70 and 106 cases respectively. In the case of murder, some of the predictors (e.g., alcohol and drug abuse problems) did not reach statistical significance, while in the case of grievous bodily harm, there were also several predictors (i.e., gender and mitigating circumstances) that might have reached significance with larger sample size.

Our study has some limitations, as we examined only women’s and men’s sentences from 2018. Therefore, assessing women’s sentences from other years is impossible. Moreover, the sample of women compared to the sample of men was relatively small, which prevented us from applying more complex statistical procedures in our analysis. Since our research was based only on the information provided by the courts, some important characteristics of women’s sentences and the circumstances of their crimes might have been omitted.

Although our study only covers a subset of female and male sentencing tendencies, it provides implications for future research. It should focus on a more in-depth examination of the preconditions for sentencing tendencies and a more comprehensive analysis of judges’ motives in discretionary sentencing decisions, particularly those related to community sanctions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and R.V.; methodology, R.V. and L.J.; writing—A.T., R.V. and L.J.; writing—review and editing, A.T., R.V. and L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT), agreement number S-MIP-19-39.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aebi, Marcelo F., and Mélanie M. Tiago. 2020. Prisons and Prisoners in Europe in Pandemic Times: An Evaluation of the Medium-term Impact of the COVID-19 on Prison Populations. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Belknap, Joanne. 2021. The Invisible Woman. Gender, Crime, and Justice, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett, Gemma. 2016. ‘We have no awareness of what they actually do’: Magistrates’ knowledge of and confidence in community sentences for women offenders in England and Wales. Criminology and Criminal Justice 16: 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontrager, Stephanie, Kelle Barrick, and Elizabeth Stupi. 2013. Gender and sentencing: A meta-analysis of contemporary research. The Journal of Gender, Race & Justice 16: 349–72. [Google Scholar]

- Brielle, Francis. 2016. The Female Human Trafficker in the Criminal Justice System: A Test of the Chivalry Hypothesis. Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004–2019. Available online: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5116 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Carlen, Pat. 2013. Introduction: Women and Punishment. In Women and Punishment. The Struggle for Justice. Edited by Pat Carlen. New York: Routledge, pp. 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chatsverykova, Iryna. 2017. Severity and leniency in criminal sentencing in Russia: The effects of gender and family ties. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 41: 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Ahram, and Melinda Tasca. 2019. Disparities in women’s prison sentences: Exploring the nexus between motherhood, drug offense, and sentence length. Feminist Criminology 14: 420–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criminal Code of the Republic of Lithuania. 2000. No. VIII-1968, Last Amendments on 5 November 2020. Available online: https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/TAR.2B866DFF7D43/ZpNMZQSaRN (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Curry, Theodore R., Gang Lee, and S. Fernando Rodriguez. 2004. Does Victim Gender Increase Sentence Severity? Further Explorations of Gender Dynamics and Sentencing Outcomes. Crime and Delinquency 50: 319–43. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Kathleen, and Michael Tonry. 1997. Gender, race, and sentencing. Crime & Justice 22: 201–52. [Google Scholar]

- Doerner, Jill K., and Stephen Demuth. 2010. The independent and joint effects of race/ethnicity, gender, and age on sentencing outcomes in U.S. Federal Courts. Justice Quarterly 27: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerner, Jill K., and Stephen Demuth. 2014. Gender and sentencing in the federal courts: Are women treated more leniently? Criminal Justice Policy Review 25: 242–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embry, Randa, and Phillip M. Lyons. 2012. Sex-based sentencing: Sentencing discrepancies between male and female sex offenders. Feminist Criminology 7: 146–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiburger, Tina L., and Carly M. Hilinski. 2013. An examination of the interactions of race and gender on sentencing decisions using a trichotomous dependent variable. Crime & Delinquency 59: 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gelsthorpe, Loraine, and Gillian Sharpe. 2015. Women and sentencing: Challenges and choices. In Exploring Sentencing Practice in England and Wales. Edited by Julian V. Roberts. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 118–36. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Timothy, and John Wooldredge. 2006. Sex-based disparities in felony dispositions before versus after sentencing reform in Ohio. Criminology 44: 893–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedderman, Carol. 2004. The ‘criminogenic’ needs of women offenders. In Women Who Offend. Edited by Gillian McIvor. London: Jessica Kingsley, pp. 228–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hedderman, Carol, and Loraine Gelsthorpe, eds. 1997. Understanding the Sentencing of Women. London: Home Office. [Google Scholar]

- Hedderman, Carol, and Rebecca Barnes. 2015. Sentencing women: An analysis of recent trends. In Exploring Sentencing Practice in England and Wales. Edited by Julian V. Roberts. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Heidensohn, Frances, and Marisa Silvestri. 2012. Gender and crime. In The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Edited by Mike Maguire, Rod Morgan and Robert Reiner. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 336–69. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, Sergio, and Shaul Oreg. 2008. Chivalry and the moderating effect of ambivalent sexism: Individual differences in crime seriousness judgments. Law & Society Review 42: 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Information Technology and Communications Department. 2021. Information Technology and Communications Department under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania. Available online: https://ird.lt/lt/paslaugos/tvarkomu-valdomu-registru-ir-informaciniu-sistemupaslaugos/nusikalstamu-veiku-zinybinio-registro-nvzr-atviri-duomenys-paslaugos/nusikalstamumo-duomenu-rinkiniai/family.ASM (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Koons-Witt, Barbara A. 2002. The effect of gender on the decision to incarcerate before and after the introduction of sentencing guidelines. Criminology 40: 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koons-Witt, Barbara A., Eric L. Sevigny, John D. Burrow, and Rhys Hester. 2014. Gender and sentencing outcomes in South Carolina: Examining the interactions with race, age, and offense type. Criminal Justice Policy Review 25: 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruttschnitt, Candace, and Jukka Savolainen. 2009. Ages of chivalry, places of paternalism: Gender and criminal sentencing in Finland. European Journal of Criminology 6: 225–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloch, Margaret, and Gill McIvor, eds. 2013. Women, Punishment and Social Justice: Human Rights and Penal Practices. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Michailovič, Ilona. 2014. Moterų nusikalstamo elgesio problematika. Teisė 93: 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailovič, Ilona, and Mindaugas Girdauskas. 2016. Socialinio tyrimo išvada nagrinėjant baudžiamąsias bylas. In Baudžiamoji Justicija Ir Verslas. Edited by Gintaras Švedas. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto Teisės fakultetas, pp. 417–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mustard, David B. 2001. Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in sentencing: Evidence from the US Federal courts. Journal of Law and Economics 44: 285–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikartas, Simonas, and Liubovė Jarutienė. 2022. Individualising probation conditions in cases of domestic violence: The study of sentencing practice in Lithuania. European Journal of Probation 14: 20662203221106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, Jeffrey S. 2020. Gender equality and sentencing outcomes: An examination of state courts. Criminal Justice Policy Review 31: 673–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, Mari B. 2013. Examining the impact of familial paternalism on the sentencing decision: Gender leniency or legitimate judicial consideration? In Perceptions of Female Offenders. Edited by Brenda L. Russell. New York: Springer, pp. 181–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pina-Sanchez, Jose. 2013. Sentence consistency in England and Wales: Evidence from the Crown Court sentencing survey. British Journal of Criminology 53: 1118–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina-Sanchez, Jose, and Lyndon Harris. 2020. Sentencing gender? Investigating the presence of gender disparities in Crown Court sentences. Criminal Law Review 1: 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pina-Sanchez, Jose, and Robin Linacre. 2014. Enhancing consistency in sentencing: Exploring the effects of guidelines in England and Wales. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 30: 731–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Julian V., and Jose Pina-Sanchez. 2014. Previous convictions at sentencing: Exploring empirical trends in the Crown Court. Criminal Law Review 8: 575–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, Fernando S., Theodore Curry, and Gang Lee. 2006. Gender differences in criminal sentencing: Do effects vary across violent, property, and drug offenses? Social Science Quarterly 87: 318–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalauskas, Gintautas. 2016. Nusikaltimų prevencijos programų Lietuvoje nuostatos: Tarp absurdo ir kokybės. Kriminologijos Studijos 4: 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sakalauskas, Gintautas, Liubovė Jarutienė, Vaidas Kalpokas, and Rūta Vaičiūnienė. 2020. Kalinimo Sąlygos ir Kalinių Socialinės Integracijos Prielaidos. Vilnius: Teisės institutas. [Google Scholar]

- Spivak, Andrew L., Brooke M. Wagner, Jennifer M. Whitmer, and Courtney L. Charish. 2014. Gender and status offending: Judicial paternalism in juvenile justice processing. Feminist Criminology 9: 224–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, Cassia. 1999. Gender and sentencing of drug offenders: Is chivalry dead? Criminal Justice Policy Review 9: 365–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensmeier, Darrell, and Stephen Demuth. 2006. Does gender modify the effects of race–ethnicity on criminal sanctioning? Sentences for male and female white, black, and Hispanic defendants. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 22: 241–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensmeier, Darrell, Jeffery Ulmer, and John Kramer. 1998. The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: The punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology 36: 763–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereškinas, Artūras, Rūta Vaičiūnienė, Simonas Nikartas, and Liubovė Jarutienė. 2021. Moterys Lietuvos Baudžiamojo Teisingumo Sistemoje: Nuo Baudimo Praktikų Iki Baudimo Patirčių. Vilnius: LSMC Teisės institutas. [Google Scholar]

- Tillyer, Rob, Richard D. Hartley, and Jeffrey T. Ward. 2015. Differential treatment of female defendants: Does criminal history moderate the effect of gender on sentence length in federal narcotics cases? Criminal Justice and Behavior 42: 703–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, Roy. 2015. World Prison Population List—Eleventh Edition. Birkbeck: Institute for Criminal Policy Research. Available online: http://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_prison_population_list_11th_edition_0.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Walmsley, Roy. 2017. World Prison Population List—Twelfth Edition. Birkbeck: Institute for Criminal Policy Research. Available online: https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/wppl_12.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

| 1 | Only one type of probation was considered in the study, which is known as full suspension of custodial sentence under the CC and is specified in the CC art. 75, part 2. Persons sentenced to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six years for negligent offenses or up to four years for one or more minor or serious intentional offenses may be granted full suspension of a custodial sentence for a period of one to three years (Article 75, part 2 of the CC). |

| 2 | When imposing the restriction of freedom, the court usually assigns intensive supervision to the convict, which is the control of the convict’s whereabouts according to a set time through electronic surveillance, according to Article 48 of the CC. The court may impose certain obligations in addition to or instead of intensive supervision. A prison sentence ranging from three months to two years may be imposed. |

| 3 | As the Criminal Code of Lithuania provides several sentencing options for some offence types included in the analysis but not for others, it would not be correct to search for the predictors of incarceration. |

| 4 | In our opinion, it would not be suitable to combine severe offences (such as murder) with minor ones (such as theft of actual bodily harm) in the same regression model. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).