1. Introduction

This study investigates the application of restorative practice (RP) and the lived experiences of practitioners within a restorative school in Oxfordshire, England. It is a reflexive thematic analysis conducted using

Braun and Clarke’s (

2006,

2021) six-stage model, in conjunction with

Saunders (

2006) Implementation Staircase. Designed to provide an insight into an established restorative school, this inductive study provides new data offering further clarity on RP in education by describing established and embedded practice. This study explores practitioner viewpoints and is set out into the following components: Context, Restorative Practice: Growing Applications, Methodology, Data and discussion, and Analysis.

Whilst this study does not attempt to offer a definitive model, quantitative data, or to measure the implementation of RP, it does offer further clarity on practitioners’ understanding of RP in education and the discrete practice within an established restorative school. It also provides a foundation for sites of further detailed task analysis. Three clear themes were constructed under the following headings: conceptual, pedagogical, and routine practice. The data and discussion not only provide a wholistic practitioner overview, but also provide examples of how these themes are operationalised in practice. The three themes are not necessarily new to the restorative literature; however, the way in which they are articulated and their combination as a restorative paradigm offer a unique perspective on RP in education. Similar studies have been conducted that articulate practitioner observations (

Bevington 2015;

Kaveney and Drewery 2011); that explore restorative pedagogy (

Vaandering 2015); and/or highlight the conceptual links to restorative justice, such as

Zehr (

1990).

2. Context

The context of this study is a special school in Oxfordshire, England, catering for secondary age children (11–18 years old) with special educational needs and disabilities. This is a community special school for children up to the age of 18 with complex special educational needs and disabilities. All students have Education, Health and Care Plans with a range of needs but primarily, students have moderate cognition and learning difficulties, autism spectrum disorder and/or social, emotional, mental health difficulties. The school was recently included in a national evaluation, looking at embedding RP (

Warin and Hibbin 2020); recognised as the most experienced setting within the evaluation, it could be considered as an optimum site for an inductive study. Restorative justice has a long history in Oxfordshire, situated within the Thames Valley, itself well known for restorative policing (

Hoyle et al. 2002). The school first implemented RP in the early 2000s, gaining the Restorative Service Quality Mark in 2017. This accreditation, awarded by the Restorative Justice Council, an independent third sector membership body for the field of restorative practice, has been replaced by the Registered Restorative Organisation status (

RJC 2019). The school’s reaccreditation process (2021) was the context for this study. ‘Employee Practice Statements’ created during this process became the primary data source.

It was not my intention to enter the study with strident objectivity; this would have been unmanageable since I am not only the researcher, but also the Head Teacher of the research setting. During analysis, I adopted an evaluative approach where I could use cultural competency (

Tarsilla 2010, p. 105) to maximise intense immersion in the data.

McArthur (

2020) argue that “We research the social world because we are a part of it. Thus, distance in the form of strident objectivity or carefully constructed barriers between self and research runs counter to a focus on social justice. What is needed, therefore, are multiple perspectives and movement between them to avoid any distortions from a rigidly fixed position” (

McArthur 2020, p. 28). Multiple perspectives in this study are represented in data from a cross-section of staff linking to the Implementation Staircase (

Saunders 2006), used to organise the data and to structure comparative analysis. It is important, however, to acknowledge the challenges of insider research and to recognise that competing priorities will always guide participants’ accounts and the way in which the themes are constructed.

3. Restorative Practice: Growing Applications

There is a large body of literature on RP in education; however, there is not a universally agreed model, description or set of competencies, with studies suggesting that this multi-layered concept “does not easily lend itself to a universal definition” (

Hollweck et al. 2019, p. 246). Similarly, in other settings, RP is ill defined. Contemporary research of RP in prisons describes “widespread confusion as to the definition of RP and what constitutes RP” (

Calkin 2021, p. 92). Studies include contemporary quantitative analysis (

Darling-Hammond et al. 2020), and a systemic review describing the state of the literature on RP in schools (

Zakszeski and Rutherford 2021). Both studies build on work such as

Anfara et al. (

2013); however, it is frustrating and pertinent to note that whilst they were published albeit almost a decade later, the research is still described as “in a nascent state” (

Darling-Hammond et al. 2020, p. 305) and that “much ambiguity and cross-source variation remain regarding the definition” (

Zakszeski and Rutherford 2021, p. 2). The studies also raise questions about the validity of data and suggest there is “limited research evidenc[ing] the effectiveness of this approach according to established educational evidence standards” (

Zakszeski and Rutherford 2021, p. 13). Recommendations include a need for further research and clarification of definitions. This has been interpreted by others as the need for specific task analysis (

Bevington 2021). Whilst these findings illustrate the fact that growth does not necessarily represent increased understanding, exponential growth, however, is clearly evidenced with the number of studies meeting the criteria for the systemic review increasing dramatically from 2000, reaching its peak in 2020 (increase of 71 studies).

RP is increasingly used in other settings such as prisons (

Calkin 2021), housing (

Hobson et al. 2021) and higher education (

Roberts 2016). The educational literature on RP, however, is described as having “far greater depth” (

Calkin 2021, p. 97) but there is still a perception that it is an “ill-defined practice with little consensus on its applications” (

Fields 2003 cited in

Anfara et al. 2013), and that there is a “sustainment of… practice-to-research gap” (

Zakszeski and Rutherford 2021, p. 13). There are, of course, many prominent explanations of RP in education including: Core Values (

Hopkins 1999); Restorative Definitions (

IIRP 2015); and Restorative Principles (

Anfara et al. 2013). Overlaps from these explanations include: the need to understand ‘affects’ (

Tomkins 1962) and emotions; articulation of an individual’s needs; the aspiration to resolve conflict; and ownership of behaviour. Whilst there are commonalities, research studies evidence wide-ranging informal and formal processes; differing contextual settings; diverse typology; and a graduated application, from informal practice to 1:1 conferencing and family group conferencing. Once again, this reinforces the need for inductive analysis and practitioner-led research.

3.1. Global Links

Global links to the three themes identified in this study (conceptual, pedagogical and routine practice) include

Kelly et al. (

2014), who comprehensively speak to all three themes including routine practice in education;

Fine (

2018) and

Vaandering (

2015), who evidence specific teaching and restorative pedagogy; and

Wong (

2015), who poses key questions linked to the conceptual theme developed in this study, e.g., a way of being. The ideas of ‘how we think and how we act’ are reinforced by

Fine (

2018), whose descriptive account of one Canadian teacher leader embodies the idea of ‘being restorative’, whilst bridging across into the pedagogical theme, beginning with ‘teaching with quiet authority’ using ‘experience as text’, and restorative conversations to facilitate what could be considered as critical pedagogy (

Freire 1996). This direct teaching of restorative pedagogy is far less common in the literature; however, there are examples including where it has been embedded in teacher training (

Hollweck et al. 2019;

Vaandering 2015) and developed into a taught curriculum (

Toews 2013).

3.2. Zakszeski and Rutherford: Five Key Studies

It is highly relevant to this study to return to the work of

Zakszeski and Rutherford (

2021), since their systemic review includes several studies that highlight practitioner viewpoints. This provides the opportunity to contextualise this study and offers comparative data. The 71 studies included in Zakszeski et al.’s study (

Zakszeski and Rutherford 2021) were required to meet the following criteria: “(a) reported on one or more studies examining restorative approaches in a pre-kindergarten through 12th grade educational setting and (b) reported original data related to outcomes of this implementation.” (

Zakszeski and Rutherford 2021, p. 3). These studies are of relevance to this study on both accounts and, therefore, deserve further analysis in context. Within the 71 articles, the

Zakszeski and Rutherford (

2021) review summarises 38 qualitative articles describing: their sample, objective, and main research findings. Of these articles, five explicitly focus on staff experiences (

Bevington 2015;

Cavanagh 2007;

Kaveney and Drewery 2011;

Ortega et al. 2016;

Vaandering 2014). Their focus on experiential reflection appears to suggest that they are highly relevant to this study and, therefore, further analysis has taken place to present their commonalities.

Most importantly, all five studies alluded to the fact that restorative work in schools is cultural and needs to be systemic. This was articulated most clearly by

Cavanagh’s (

2007) ‘climate of school safety’, which explicitly describes links between RP and relationships-based pedagogy. Participants in these studies described RP as an inclusive voluntary activity that was not only for students. Circles were presented as a foundational element to successful implementation alongside other specific tasks/actions, “Combining peace-making circles with restorative conversations allows a group of students and a teacher in a classroom to talk about problems… by engaging in restorative conversations, where the problem is separated from the person, teachers learn to respect the dignity of the person while dealing with the problem…” (

Cavanagh 2007, p. 34).

The five studies show that the restorative process was intended to impact the whole school, not just students. “When conflict arises, both staff and students have the option of initiating a Circle with the goal of helping to repair the harm…” (

Ortega et al. 2016, p. 9). This was not limited to participation, but also related to the learning and benefits of the process. “The benefits of restorative work which the staff reported the children having received were the same benefits that staff had received. Just as restorative conversations had taught the children to be more thoughtful and reflective about their behaviour, so it had made staff more thoughtful and reflective…” (

Bevington 2021, p. 110).

Reinforcing the routine practice theme (highlighted in this study), the five studies also described the role of a facilitator, their ability to use de-constructive questioning and the need to be reflective (

Kaveney and Drewery 2011, p. 9). Whilst discrete practical strategies were outlined, it was also apparent that flexibility was a common factor—studies stressed the importance of “allowing staff to be responsive in dealing with different manifestations of conflict in the school… The staff contributions on this point indicate that they consider it essential for there to be the space for individual professional judgement in applying interventions and systems in school” (

Bevington 2015, p. 111).

From these qualitative studies, it could be argued that the key points included (a) inclusivity (inclusion of both adults and children), (b) examples of specific restorative strategies, e.g., circles, (c) the flexibility to adapt these strategies/exert professional judgement and (d) a values-led whole school culture. It would be reasonable to note that these findings have a broad overlap with the restorative principles described by

Anfara et al. (

2013), whilst possibly offering some further specificity and direct examples of practice.

3.3. Summary

Many other studies attempt to draw value from the restorative process. These studies have not been my focus, as the purpose of this study is not to elicit or assess the value of restorative practice, or the associated outcomes with young people. It is also possible to argue that a quantitative approach is misaligned with restorative practice and that it would be difficult to attribute change to one specific intervention, if you conceptualise restorative work as cultural or as a restorative mindset (

Hopkins 2004) rather than a tool or strategy. The main takeaways from the literature include the need to further define the restorative field, the need for specific task analysis and the gap between practitioner and researcher.

4. Methodology

The methodology of this study was influenced by the constructivist ideas of restorative justice and my own anti-foundationalist ontological approach. These values led to a decision to use an evaluative thematic analysis, where meaning was built from a constructivist stance that considered social phenomena as being “produced through social interaction [and]… in a constant state of revision” (

Bryman 2016 cited in

Grix 2010, p. 61). Evaluation is, by nature, a set of practices that look to attribute value to specific interventions, policies, or activities. However,

Chelimskey (

1997), cited in

Saunders (

2006), sets out three kinds of evaluation: evaluation for accountability; evaluation for development; and evaluation for knowledge. This study is situated within an evaluation for knowledge purpose, with the aim of gaining a deeper understanding of RP in education without trying to attribute value.

As an insider researcher, and as a participant included in the data, there is an opportunity to understand complex issues, including tensions between the specific and the general and what can be presented as paradox and ambiguity (

Costley et al. 2010, p. 3). This study is designed to contribute to the narrative on restorative practice in education from an insider perspective. Despite the benefits of being immersed in the data, it is understood that hierarchy and a power imbalance within the school could influence the activation of different voices. In line with a core value of RP (

Hopkins 1999), all Practice Statements were completely voluntary; however, it would be naive to assume that the hierarchy within the school would not influence a participant’s choice to engage, how they engaged and what they reported. Most of these issues were mitigated by the positive culture in the school and the fact that the school has adopted a “distributed leadership” model, which

Harris (

2008, p. 17) describes as requiring “a shift in power and resources” (

Harris 2008, p. 17). This powershift allowed people to feel that they were not obliged to complete the form, and this school culture can be evidenced through staff survey data and participant feedback; however, it is understood that it is complex to evidence culture, especially from a quantitative perspective. The design of both the RJC’s accreditation process and the subsequent research was that as part of a collective, participants would paint a picture of an institution. Consequently, many school staff invested their time in this, seemingly wanting to highlight and share their practice. To enable anonymity, participants in this study are named as generic role titles; however, it is recognised and was highlighted to participants that within a small community, it is likely that readers who knew the school would be able to identify staff. It is important to recognise that participants, myself included, are situated within the research and that reflexive research is therefore “inevitably and inescapably shaped by the process and practices of knowledge production” (

Braun and Clarke 2021). It is therefore understood that situated interpretation of knowledge could be considered as the driving force when creating themes and when beginning to tell the story of this restorative school.

During the research, participants were asked to produce an Employee Practice Statement, which took the form of a semi-structured questionnaire. This included questions such as “Please explain how you prepare yourself and other individuals for participation in a restorative process”. Participants were then asked to provide 3 examples of how they used restorative practices within their day-to-day work. These examples resulted in extensive responses, providing individualised case studies for thematic analysis. The above questions were provided by the Restorative Justice Council as part of the Registered Restorative Organisation accreditation; only later did they become the framework for this evaluative study. This was partly due to the number of practice statements that were returned (

Table 1) and the extensive amount of data they created. The question asking for three examples was open-ended and there was no limitation on the number of words or what participants could include. Importantly, during the accreditation process, there was no institutional editing; all practice statements were returned to the Restorative Justice Council without amendments, regardless of what the staff member had included.

Building on the evaluative work of

Warin and Hibbin (

2020), it was important that a wholistic picture of the institution was created, not just one classroom or one group of teachers. The practice statements allowed for this, offering a forum for the implementation staircase (

Saunders 2006) as an organisational tool during reflexive analysis. The implementation staircase allows for policy to be depicted as “multiple ‘policy in actions’ through the experiences of different stakeholders” (

Saunders 2006, p. 210), whereby the policies and programmes shift and evolve depending on stakeholder experience (

Saunders 2006). Whilst

Saunders (

2006) primarily shares this metaphor to capture this process of policy implementation, it also allows the possibility for categorical thematic analysis at different levels of the staircase, which could then be generalised and defined as overlapping or step-specific themes.

To support categorical analysis, and to organise the data NVivo was used for data management. The goal was to produce fully realised themes, whereby the generation of themes occurs at the intersection of the data and the researcher’s interpretivist framework taking into account their prior training, skills and assumptions (

Braun et al. 2019), whilst at the same time trying to avoid domain summary. The implementation staircase was used for selecting the sample and organising the data; however, it also allowed for analysis opportunities, identifying shared situated understanding.

It is understood that methodological ‘mash ups’ can be misaligned with the ethos of reflexive thematic analysis, however they also have the potential for interesting and innovative analysis. In relation to these concerns the implementation staircase was primarily used to define the sample and as a way of further reflecting on the reflexive TA in context.

5. Data and Discussion

During the data analysis, as an insider researcher, it was important to listen to all voices with equal value and to look for commonalities, whilst not disregarding differences of opinions, no matter how trivial they may seem. This aligns both with my ontological approach and the core values of restorative practice. Whilst the approach of this study was to create themes by categorising codes to paint a practitioner’s view of a restorative school, it was understood that these were nuanced and permeable themes that overlapped and were interconnected. No intention was made to predetermine categories; however, following extensive data familiarisation, I was able to produce many initial codes, which were then reduced to 25 through merging, clustering and deleting, from which I was then able to develop the final three themes (

Table 2). Initially, I was more interested in developing the ideas around restorative mindset and defaulting to dialogue; these were later merged to create the overarching conceptual theme. Over time, it was also clear that ideas such as how staff fostered students’ emotional literacy were critical to the data. This led to expanding into the pedagogical and routine practice themes.

Whilst these are distinct themes, they are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but permeable themes that more broadly imply a reference to the general culture of the school, the way in which participants defined their restorative organisation and how they articulated a restorative paradigm. Participants talked about the wholistic nature of restorative work, its daily use and how it was embedded practice.

“I have worked at [the school] for over 16 years and feel my restorative practice is a natural process of my everyday work. Being restorative is not something you dip in and out of. The restorative values are embedded within the structures of the school’s ethos and policies… I truly feel that being restorative is about the whole picture…”

—Therapeutic Support Manager

Unpicking this idea of the “whole picture” is a complex business, and this complexity is embodied in the first theme, which is potentially a starting point for all interactions. This is a conceptual realm, one which some participants even described as a “restorative mindset”, similar to the

Hollweck et al. (

2019) description of restorative justice as a “way of being” and as such, is integral to the other themes and is foundational to RP.

5.1. Theme 1: Conceptual

Everyone involved in the study articulated that there was a conceptual element to what they did, and participants clearly described the concepts behind their work. These are defined and categorised into three sub-headings: approaching tasks with a restorative mindset; the desire to default to dialogue; and working with people in a co-constructed way. In practice, they described this as “form[ing] the core of how and what is communicated”.

Participants talked about the first sub-heading, restorative mindset, as restorative practice being more than just a job but being a set of values that they lived by. This concept is reinforced in the literature, perhaps most clearly articulated by

Calkin (

2021) who notes that for RP to be successful in schools “it must not exist as one of a range of optional interventions, but as a central philosophy that informs decisions” (

Calkin 2021, p. 97). Participants attached value to the concepts of RP, and it was important to them that they worked in a restorative school. They described ongoing dialogue and the second sub-heading, defaulting to dialogue, which can be understood as the idea that things can always be discussed in this organisation, that value is given to differing ideas and that there is no one-size-fits-all response to any given situation. This is counter to many educational scenarios where fixed rules guide responses and inflexibility in policy produces a surface-level solution. This, however, does not allow for double loop learning (

Patton 2011, p. 11), a concept that encourages “those involved to go beyond the single loop of identifying the problem and finding a solution, to a second loop which involves questioning the assumptions… values and system dynamics that lead to the problem in the first place”. A desire to default to dialogue challenges staff to ask deeper questions to uncover what is really going on, allowing for fundamental system change and a deep understanding of the perception of others. Participants articulated that dialogue was a norm in this organisation,

“The restorative process involves listening to people to help them understand. People generally tend to like being listen[ed] to, which can help them to be on board with the process”—Therapeutic Support Worker. The idea of being listened to subsequently producing a positive outcome was echoed by many participants. When describing a restorative meeting, a senior leader said:

“It was noted by the facilitator during this meeting that the staff members listening to each other, in regard to how each [person] was feeling was incredibly powerful and this caused a visible shift. Both staff relaxed when understanding and hearing each other, their body language became more united and it was as though they could allow themselves to show empathy to each other.”

—Deputy Head Teacher

Listening is consistently referenced in the restorative literature, for instance how a “willingness to listen before speaking helps temper… tendency towards impassioned debate” (

Fine 2018, p. 104). This concept was systematically reinforced; participants embodied it and valued it, reporting that defaulting to dialogue had a noticeable impact on children. They spoke about children who were ‘happy’ and ‘transformed’ due to being “

listened to, and that any conflict [would] not be brushed under the carpet but managed in a way where all parties can learn and move forward freely and without fear.” This concept links back to the restorative mindset and was described as understanding that, as humans, we all have different perceptions and whilst things may be seen as facts to one person, this may not be so clear to others. An example of this given by a teacher during the study was a child whose grandfather had passed away from coronavirus; on his return to school, everyone was very empathetic, except one student who expressed that coronavirus was not real. Whilst this could have been shut down and addressed from a factual perspective, the class teacher reported that she had individual meetings with both students and the student who made the comment came to realise that it does not matter if coronavirus is real or not, but that the other student was very sad and grieving over his grandfather. Outcomes from the meetings highlighted that that student who lost his grandfather needed understanding and friendship, but the other student needed the same, as he was really worried about the pandemic and had been articulating this by perpetuating (what is considered to most people) a conspiracy theory. The time given to this conflict demonstrates double loop learning.

The above concepts are part of a co-constructed organisation, and make up the third sub-heading, co-construction. Participants described the concept of working with others, rather than doing things ‘for’ or ‘to’ people. They talked about children taking ownership for their behaviours and being a part of the solution.

“All of our students have some concept of restorative processes—they recognise that if something goes wrong then we will look to help them find a way forward rather than ‘telling off’ students, ruling by fear or getting into a battle of wills… They are also reminded that it is their choice to engage with this process… the member of staff is a facilitator and is there to help them come up with the solutions to resolve the issues rather than come up with the answers on their behalf.”

—Pastoral Support Worker

It was also clear from the data that these values-based concepts were not happening by accident. This was a carefully orchestrated plan enacted partly through careful recruitment of staff. Several participants reported that recruitment was important:

“Whilst restorative process is voluntary, the fact that people are choosing to join our community due to the restorative culture is a massive factor. This means that even before they arrive, they know what our expectations are and have signed up to our vision.”

—Head Teacher

These are aspects that could be replicated elsewhere, and that could be implemented in other schools. However, the values that are attached to these concepts have taken time to develop and participants talked about the strength of RP being developed over many years; therefore, any implementation is expected to take time to grow and develop. The findings from the first theme link heavily to the main findings from the five studies set out in the literature review. Restorative practice permeating into culture is clearly a deciding factor when considering implementation, the difference here perhaps is that participants spoke about being restorative themselves and it could therefore be considered that the work transcends culture into the conceptual and ideological realms.

5.2. Theme 2: Pedagogical

Data showed that participants explicitly taught restorative concepts; they continually enhanced their knowledge and included communities of care in these learning opportunities. This is restorative pedagogy: the method and practice of teaching the conceptual and theoretical concepts of restorative practice. Participants talked about formal learning and professional development opportunities for themselves, and some noted the long-standing relationships with the trainer as an important factor. This training also intersected with coaching and supervision, both of which were available to some participants and were included in answers given about training and support. All participants were able to articulate training opportunities, including when restorative concepts were being used in situations where there was a different primary training focus.

“There have been times when whatever the theme… of the whole staff meeting, the facilitator… organised the small group work using a wide range of activity types for example: Pair and Share, Small group discussion Pyramid Build, Concentric Circles and not just reply on circle go-rounds”

—Class Teacher

This was of interest as it demonstrated that participants understood pedagogy and the benefits of active learning and valued the application of knowledge. Others (specifically senior leaders) talked about their links with communities of practice described as a space that

“provide[s] training, sharing of practice and a problem solution forum for professionals involved in restorative approaches”—Deputy Head Teacher. This was echoed by several other senior leaders, and interacting with communities of practice outside of the school seemed to be important. Some participants highlighted that they had additional training to meet the needs of their roles; this included Foundation Degree level study. Learning, however, was not limited to formal situations, and several participants talked about the benefits of discussing problems with colleagues. They said that

“colleagues are very knowledgeable of restorative practice” and that the:

“Senior Leadership Team have an open door policy and are more than happy to offer a reflective space if we need it and if we are involved in a particularly hard piece of work with a family or student we are always offered a space to debrief or talk it through with senior staff”

—Therapeutic Support Worker

Restorative practice was also explicitly taught to students, and participants described how they prioritised emotional literacy as a prerequisite to restorative practice. Others talked about specific resources that they had developed and how circle time, daily check-ins and time spent understanding the needs of others were all built into every-day learning. Restorative practice was also described as being taught as discrete lessons with learning outcomes linked to the core values (

Hopkins 1999) of RP. Other restorative learning was situated within other curriculum subjects, e.g., in English, where children study the book Wonder (

Palacio 2012).

“[The book] tells the story of 10-year-old Auggie Pullman, a fictional boy with facial differences, and his experiences in everyday life dealing with the condition. The story is told through the eyes of other family members and Auggie Pullman’s friends. We place[d] each character in our circle times, at varying points in their story and we pose the question: Auggie… On a scale of 1 to 10, how are you feeling today?’ Based on our knowledge of the character and their various dilemmas in the novel, we begin to empathise with the character, we began to offer suggestions as to how we can restore some brokenness in the relationships between the characters.”

—Class Teacher

Again, these activities reinforce the wider pedagogical literature;

Fine (

2018, p. 117) recounts how teachers built projects in the wake of the Eric Garner grand jury decision that included “a performance task that asked students to

practice activism”. These activities were designed to help students process and understand the impact of these decisions in the context of “race… class and gender…[and] the hyper sexualization of Black male masculinity”. Fine describes these educating moments through two distinct registers, on one hand “the language of planning and pedagogy”, e.g., race as a social construct; the other as a language of intuition, responding to students who were hurting and needing to be understood. These examples highlight the power of restorative work and how “students might experience school differently if more teachers were able to capitalize on the synergies between restorative justice and the tradition of critical pedagogy” (

Fine 2018, p. 118).

Restorative pedagogy also extended to parents. Participants in this study described how they led parent training sessions after school. Whilst the purpose of the training session was to demonstrate the school’s restorative systems, parents were also able to see how the approach could be used in the home setting.

“As a result of this piece of work, a parent felt she could use this… to support her child in [the community]… She reported that the training session made her consider this approach and… she felt she could facilitate a restorative conversation, which {enabled] her child to verbalise his anxiety…”

—Assistant Head Teacher

This is relevant as it demonstrates that pedagogy is extended to communities of care and that a restorative school has a wider responsibility to stakeholders outside of its immediate student population. Students, however, are also mentioned as vehicles for knowledge and, on one occasion, they are mentioned as completing restorative work for other children, acting as champions for restorative practice and facilitating restorative interventions.

“… we had a year 11 student who… had adapted really well over the years to the restorative ethos. He was so used to the restorative process that one day when he was waiting in our [therapeutic] space, a couple of year 7 students came along to find a member of our team to support them… following an issue at break time. While they waited for one of us to arrive he followed the Mend it Meeting process with them. By the time we arrived they had finished and were back in class. He talked me through their meeting. I visited each student in their class to check in and find out how they felt about the meeting, the process and the outcome. The students relayed… how they had discussed their thoughts, feelings and needs, before deciding how they would best move the situation forward. This event has stayed with me since. None of the students could understand why we were so impressed with all of them as they really didn’t think it was anything out of the ordinary for an older student to be supporting them with this.”

—Therapeutic Support Worker

This theme demonstrates how restorative practice is taught to and by participants, that this work is highly valued, and that participants recognise the development of their own knowledge, through the knowledge of others. Participants gave specific examples of how restorative pedagogy can be built into everyday learning, e.g., by building restorative learning objectives and how they explicitly taught parents. These examples reinforce the idea that restorative practice can be embedded in teaching and learning and whilst examples of this are less prevalent in the literature, participants in this study felt this was an important part of their work.

5.3. Theme 3: Routine Practice

The third theme is practical application of RP. This is participants using their restorative tool kit daily, and staff, students and parents expecting to see it as established intuitive practice. Again, this is a common theme in the restorative literature with studies recognising the need for further specificity; “Leaders agree that restorative instruction should prioritize “building and repairing relationships,” but they have not yet specified what doing so entails in terms of observable practice” (

Fine 2018, p. 105).

Participants in this study reported that there was a school-wide culture of helping students build strong positive views of themselves and that specific restorative interventions enabled this to happen. They focussed on circle times, daily check-ins and talked extensively about mend-it-meetings (MIMs). Mend-it-meetings are restorative conversations, usually facilitated by an adult. Participants articulated these meetings as alternatives to punitive sanction-based systems:

“Students are not humiliated or dressed down, they are supported and directed to manage their own behaviour and emotions… if there are any significant incidents or obstacles between students or between a student and a member of staff then, if both parties are willing, it can be resolved through a mend-it meeting where a facilitator supports them to discuss the issue and find a way to move forward.”

—Pastoral Support Worker

Participants were clear that there was no expectation to say sorry during these meetings but that understanding the perception of others was a priority.

“Pupils are taught on entry to school about the restorative approach…. Prior to any mend it meeting, pupils are aware of the expectations and have had 1–1 time to talk through the situation.... Pupils need to feel they are emotionally ready to be part of the restorative process, therefore it is completed on a voluntary basis… The students are aware there is no force to provide an apology and that pupils are expected to work together to find a way to move forward from their conflict.”

—Assistant Head Teacher

This is different to the national media narrative around restorative practice in schools, which centres around students making apologies to staff. Unusually, the MIMs in this study were not just meetings between teachers and students but participants reported resolving conflict between parents, school adults, and included non-teaching staff in these events. One member of the admin team recounted how they had been involved in a MIM with a child who had been ordering lunch but not paying for the food. His parents/carers were unaware that he had been eating lunch every day as they had been sending him in with a packed lunch. “I found the meeting really insightful… The meeting was really calm and a great approach to get the student to understand what was wrong without it being a negative conversation”. Other examples of MIMs included more serious situations such as assaults, and day-to-day situations such as disagreements between pupils.

What is interesting here is that all participants had an awareness and some level of engagement in the process, regardless of whether they were teachers, support staff, administrators, or senior leaders. It was a cultural norm that this process was used to resolve conflict at all levels. This reinforced the first finding from the five studies analysed in the literature review: the restorative process was for everyone in a school, not just students. Similarly, echoing this inclusive model, circles were used in classrooms and senior leadership offices.

“Every single day we have a restorative check in during the leadership team meetings... This is run as a circle... it allows us as a group to all speak before we start our day… and means that we have an understanding of the stress levels of others, what they are dealing with that day and what is important to them.”

—Head Teacher

Participants talked about how circles were part of their everyday routines, built into teaching and learning and used to follow up specific events. They also referenced them during training and this concept was clearly an important part of how the culture was developed. Whilst the notion of circles reinforces the findings from the five studies,

Cavanagh (

2007) talks specifically about peace-making circles being combined with restorative conversations. Participants in this study did not separate the two and it was clear that circles were defined here as RP. Whilst this may seem like semantics, it is important to define the key elements if we aspire to achieve a comprehensive definition. One notable exception from the data was any discussion about exclusions. Not one comment was made about exclusions, the lack of them or the fact that RP is a way of addressing high levels of exclusions; exclusions feature significantly in the narrative of most restorative studies and, therefore, this was unusual. As an insider researcher, I would like to think that exclusions are just not in participants’ vernacular, and whilst this is only an assumption, what is known is that they did not feature in the data.

One other outlier to the data was a code created early in the analysis that I expected to feature heavily in the data. This was the idea of showing vulnerability:

“It is often the little things we do that matter, such as asking them a question about something they told you they were going to do the day before or laughing at a shared joke… sometimes, it is being willing to be a little vulnerable ourselves and share what we are feeling that then allows students to be open themselves.”

—Class Teacher

I know from my experience as an insider researcher that this is commonplace, and that significant change can be evidenced in children who experience adults showing vulnerability. This however was not demonstrated heavily in the data and, therefore, remains an outlier in this study.

Data analysis showed a great deal of continuity in thinking across all steps of the implementation staircase. The language used was idiomatic and situated understanding of conceptual, pedagogical and practical themes was broadly comparable. One assumption that was subsequently challenged was that senior leaders would have a more complex and conceptual understanding of restorative practice. In reality, there were many examples of other participants who clearly demonstrated complex understanding of RP and were able to articulate this from a conceptual as well as practical perspective. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the teaching staff had a greater focus on pedagogy; however, this theme was also embodied with senior leaders and through procedural professional development opportunities for support staff. Much of these commonalities seem to be derived from the fact that this was values based and, therefore, participants saw themselves as being restorative, rather than just carrying out restorative work.

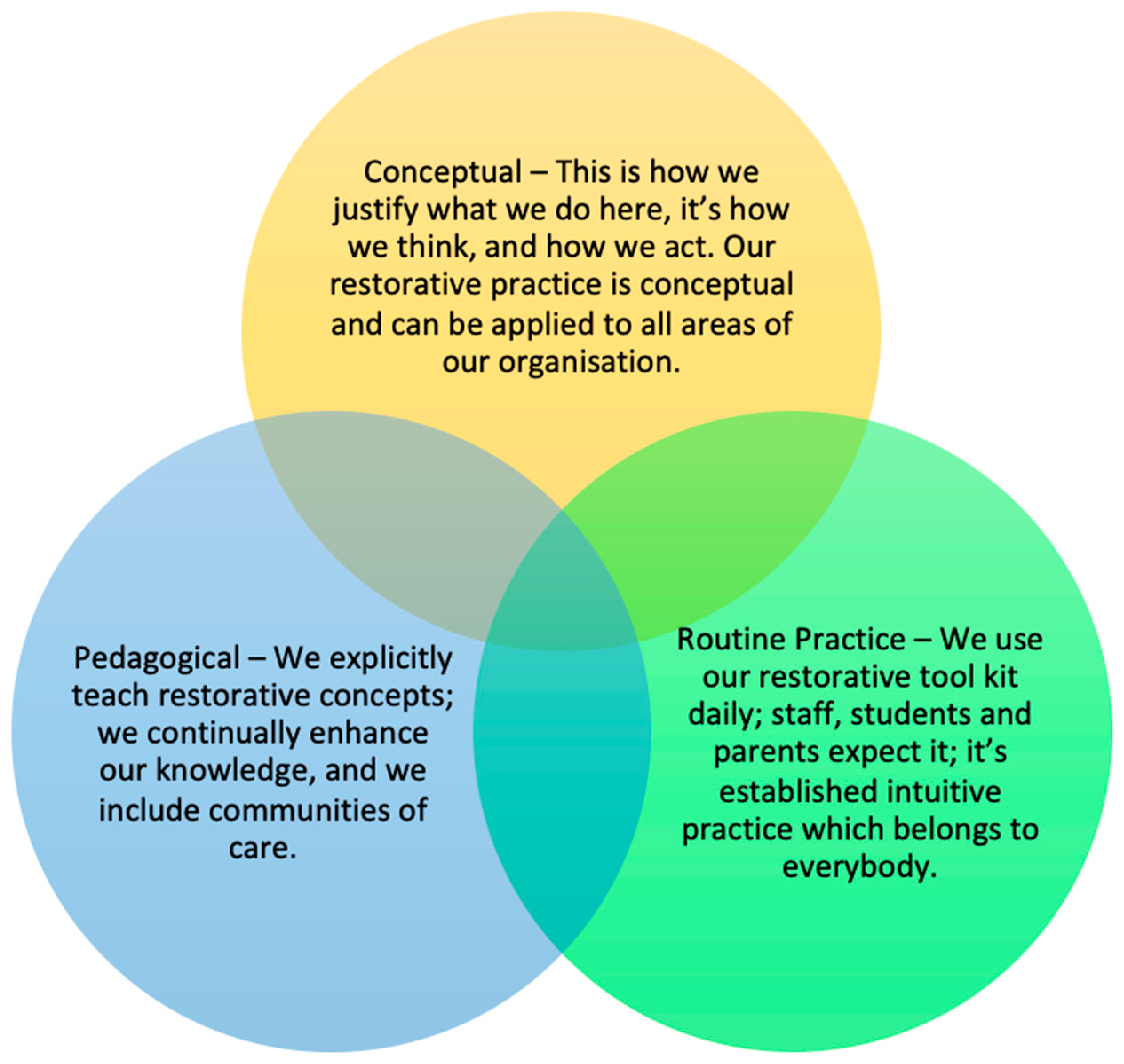

6. Analysis

This study is situated within evaluation for knowledge and provides a deeper understanding of practitioner perspectives of RP in education, allowing for a window into the world of a restorative school. It highlights what participants wanted to share about their practice and categorises these ideas into themes. These themes could be defined as a restorative paradigm, with the diagram below (

Figure 1) showing a visual metaphor of how practitioners understand their restorative school and the quotations above describing how these themes are operationalised in practice.

Much of the narrative provided by participants reinforced other studies, including the five studies explored in the literature review. Themes also linked to other studies such as

Fine (

2018), whose study demonstrates the importance of restorative pedagogy and the conceptual ideas of

Hollweck et al. (

2019), who define restorative practice in education as a way of being and as something that must be experienced (

Hollweck et al. 2019, p. 263). This would suggest that the above themes from an established restorative school may be of interest to other educational professionals considering implementing RP, or those wanting to further understand discrete practice and the definition of RP in education. Whilst a relatively large amount of data was captured, due to the limitations of this study, the explicit detail embodied in the data could still be explored further. For example, specific task analysis has not taken place, but the foundations of this have been laid. A further study that explores task analysis of the three themes could lead to increased understanding of RP in education. It could be argued, however, that the flexibility and permeability of themes is an important aspect of RP in education and, therefore, definitions of practice also need to be informed by situated contextual understandings of individual settings. It was not my intention to provide a comprehensive definition of RP, but this study goes someway to support understanding of embedded RP in education.

An additional critique is that the visual representation of the implementation staircase has several difficulties when used in this study. It could be argued that the staircase implies information is only ever passed in a logical order and the visual representation reinforces a traditional hierarchy. In practice, in this school, participants described collaborative ways of working, with examples of direct interactions between all steps in the staircase. Examples also included similarities in the narrative and whilst participants had differing roles, they seemed to have a shared situated understanding. Participants demonstrated interconnections between all levels of the staircase and situated understanding of RP was in the main uniform. Participants in this study felt that they were restorative people, and these were values that they attributed to themselves rather than the school. This was a comment on their own identity, opposed to a set of skills. This aligns with social capital theory, where shared values bind people together and make cooperative action possible (

Cohen and Prusak 2001 cited in

IIRP 2015). Further understanding of how these values are developed and the links between social capital and RP would be of great interest. This could be derived from a further study that considers commonalities across several schools.

Whilst the research portrays RP as ill-defined, it is not a ‘given’ in any specific context. In this school, for example, this study suggests that RP is clearly defined, well understood by staff and has become routine practice. However, the review implies that restorative work can be complex and explaining that complexity takes time and perhaps even takes experiential learning (

Hollweck et al. 2019). This is one of the driving factors for insider research. By routine practice, I refer to wider work than what is commonly understood as RP. This is wholistic educational practice, which includes but is not limited to “managing the learning environment, teaching subject-matter content through learning trajectories, using tiered intervention approaches… and ensuring follow-through and continuity” (

Committee on the Science of Children Birth to Age 8: Deepening and Broadening the Foundation for Success, Board on Children, Youth, and Families et al. 2015, pp. 239–40).

Finally, this study presents practitioner understanding of RP within one school. This is comprehensive, wholistic practice that runs across the whole school and is part of the wider culture, not just practice as an intervention. The paradigm has the potential to explain this breadth of restorative work and to lead into further operationalising this in context. Moreover, in our school, the paradigm will help us articulate our understanding, acting as an aide memoire, and will become part of staff induction. Most importantly, the paradigm reinforces the key message that RP is not just an intervention or a behavioural strategy. These themes are the connective tissues that run through an organisation and impact on every interaction, policy, process, and relationship, articulated through: the conceptual; the pedagogical; and the practical understanding of restorative practice.