Abstract

In the recent decades, fashion brands and retailers in the West have introduced supplier’s Codes of Conduct (CoC) to strengthen international labour standards in their supply chain. Drawing from the concept of workers’ agency and the theory of reciprocity, this paper examines the implementation of CoC from the workers’ perspective and identifies the mechanism used by the workers to negotiate with their employer. Qualitative data was collected from forty semi-structured interviews with mangers, union representative and workers at a garment factory in Vietnam which manufactures clothes to a few well-known fashion brands in the US and Europe. The findings show that, externally, workers are united with the management in hiding non-compliance practices to pass labour audits while, internally, workers challenge the management about long working hours and low pay. This finding highlights the active roles workers play on the two fronts: towards their clients and towards the management. Their collaboration is motivated by the expectation that the management will return the favour by addressing their demands through a reciprocal exchange principle. This paper sheds light on an alternative approach to understanding collective bargaining and labour activism at the bottom of the supply chain and provides recommendations for further research.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, concerns of labour standards and workers’ rights in global supply chains have resulted in many Western brands and retailers adopting suppliers’ codes of conduct (CoC) as a voluntary-regulatory measure to promote international labour standards in suppliers’ factories. Clothing manufacturing factories in developing countries have long been known to employ low paid young female workers who constantly have to work for long hours under poor workplace conditions, and are often subjected to physical and psychological abuse [1,2]. The introduction of CoC by global brands aims to address these issues.

After more than twenty years of research on CoC implementation, from the early works by Hilozitz [3] and Liubicic [4] to the recent developments by Louche [5], Underhill et al. [6] and Egels-Zanden [7], the improvement in labour standards and workers’ rights in the global supply chain remains questionable. A general consensus from the existing literature points towards the ineffectiveness of CoC implementation using a check and compliance approach which often fails to detect suppliers’ violation of workers’ rights to freedom of association and meaningful workplace unionism [5,8]. Many case studies which investigated the implementation of CoC at manufacturing factories flagged up operational and institutional barriers to the improvement in labour standards and workers’ rights [9,10,11,12]. However, most of the research in this field tends to place the focus on the role of buyers and suppliers in implementing and enforcing the codes while viewing workers as mere victims or beneficiaries of the labour compliance. This paper offers a different perspective to the understanding of CoC implementation by placing the focus on women workers as active agents pursuing their goals in the employment relation. Drawing from the agency concept and the theory of reciprocity, this paper highlights the role workers play in the implementation of CoC and their use of reciprocal exchange as a bargaining tool in the worker–management relation. Although the findings are limited to a single case study and have no implication of generalisation, this paper shed lights onto an alternative conceptualisation of labour activism and collective bargaining at the bottom of the global supply chain.

The following sections of this paper start with a literature review, followed by an overview of the context of the clothes manufacturing in Vietnam. Subsequently, this paper details the research design and presentation of findings. This paper then discusses various implications and ends with a recommendation for further research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Codes of Conduct in Global Supply Chains

Since the 1990s, thousands of companies have adopted voluntary regulatory measures such as CoC to strengthen the application of international labour standards in their supply chains [13,14,15,16]. The implementation of CoC, however, has faced a great deal of criticism of inadequate auditing practices which fail to detect the violation of CoC such as discrimination, harassment and freedom of association [17,18,19]. Some studies also highlight the fact that suppliers have used various ways to deceive labour auditors who are hired by buyers to monitor CoC compliance [20,21,22,23]. Much of these studies suggest the command and control method that Western brands and retailers exert on suppliers is ineffective.

Some research claim that a collaborative approach is needed to improve compliance such as long-term commitment, cost sharing and trust between buyers and suppliers [24,25]. Others, however, are sceptical of this voluntary CoC, arguing that corporate buying practices, such as squeezing suppliers on price, quality and short lead time, to a large extent, force suppliers and their subcontractors into a non-compliance position [26,27]. Pedersen and Andersen [28] point out that the business case of ‘doing good’ does not always extend evenly to all actors in the supply chains. This claim is also supported by Hoang and Jones [23]—in a more complex supply network, the second and third tier of suppliers are found to collude to defy CoC compliance.

Institutional and managerial factors are also discussed as indicators of CoC compliance and improvement in labour standards. The study by Locke et al. [29] suggests that the variation in the level of compliance of CoC by different suppliers reflects the quality of legal regulations in the country where factories are located, while Frenkel and Scott [11] argue that the management styles of suppliers influence the quality of social performance. The role of workers and unions as active stakeholders in pursuing meaningful change is often mentioned as a desirable outcome of CoC that empowers workers and their ability to organise collective actions [10,12].

Only until recently, research, e.g., [5,30,31], has placed more focus on the aspect of agency and empowerment of workers—the implication of autonomy, self-determination, self-direction, participation, mobilisation and self-confidence [32]—as a part of the CoC implementation process. While these studies have laid a good foundation to this under-researched area of CoC, there is still little understanding of the role workers play in the implementation of CoC, and how and whether it influences employment relations at the workplace. This paper aims to offer further detailed explanation to these issues.

2.2. Compliance Dilemmas

Suppliers often claim that compliance with CoC would lead to them losing competitiveness in terms of higher costs, longer lead times and the fear of buyers moving elsewhere [33]. Evidence shows that buyers in apparel sectors can switch suppliers at almost no cost [34]. Once standards are improved, suppliers may lose their contracts as buyers switch to lower cost suppliers [33,35] (p. 54) quote a supplier’s experience “I spent three years getting up to compliance with the SA8000 standard, and then the customer who had asked for it in the first place left and went to China”. But when Chinese labour cost was increased as the result of the labour law introduced in 2008, many international companies have relocated productions to Vietnam saving them a third of the cost they would have to pay to Chinese workers [36].

However, if suppliers are found to not be complying with CoC, they may lose their Western customers based on ethical grounds. Although some buyers may retain their relationship with suppliers despite violations [37], the arm’s length contracting suppliers are more likely to face contract termination than those with obligational contracting arrangements [10]. Suppliers, especially those at the bottom of the supply chain, find themselves disadvantaged either way. For this reason, they either choose to deceive buyers on compliance or both buyers and suppliers implicitly compromise to certain standards in the codes, for example, wages, work hours and freedom of bargaining. Some suppliers claim that they are not paid for complying with work hours and compensation requirements in the codes [38]. As Vogel [34] (p. 95) points out “Non compliance may risk suppliers reduce sale to western market, but compliance does not necessarily increase sale”. This view further reinforces that there is a lack of incentive for CoC compliance across the global supply chain. However, this issue has never been explored from the workers’ perspective. Despite the consensus that the introduction of CoC raises workers’ awareness of their rights to freedom of association and decent working conditions, there are unanswered questions of how or whether workers’ awareness of their position in the global supply chain influences their judgement of CoC and their actions towards the management.

2.3. Workers’ Empowerment and Agency

The term ‘empowerment’ implies a transfer or acquisition of power [31,39,40,41], or the process of awareness and capacity-building, which increases the participation and decision-making power of individuals or groups [42]. Empowerment is necessary to enable individuals to act according to their self-determination. According to Giddens [43], the notion of agency refers to the ability of individuals to “act otherwise”, the autonomy, self-determination and self-direction, participation, mobilisation and self-confidence [32]. This means workers can be active agents with the ability to make things happen through their own actions rather than quietly accepting the conditions imposed by management. Some have argued that workers in the global supply chain can be agents of power and change even in a constrained environment and with restricted choices [5,44].

The ethical discourse of CoC tends to view workers in the supply chain as vulnerable, passive, powerless and desperate individuals [45,46] or victims of management abuse, being coached to report positively, but dishonestly, about compliance practices [20,22]. In contrast, the international development literature overwhelmingly regards workers as active economic actors making economic choices [47,48,49]. For many young people in developing countries, factory work not only provides the opportunity to have a paid job, but also involves their transformation from the agricultural to the industrial working class, and they “not only dream of becoming industrial producers, but also modern consumers” [48] (pp. 13–14). The agency perspective of women workers working in manufacturing in China is also affirmatively portrayed in a study by Ma and Jacobs [49] as:

“[workers] had a set of well-defined criteria for assessing whether a factory is good and worth entering… These women purposefully picked and chose, changing factory when dissatisfied… They had in mind concrete objectives that included gaining new knowledge and skills, seeking promotion opportunities, and earning as much as possible….[49] (p. 830)

Although workers may pursue their work-life objectives within a limited choice set available to them, adopting the agency’s view of workers would enable the examination of CoC implementation in a way that might facilitate or hinder the perceived agency of workers.

Arguably, the introduction of CoC to some extent empowers workers through awareness raising of labour rights and standards [5,9,30] but the agency aspect of workers participation in CoC implementation, their choices and actions are rarely explored. Recent studies of workers’ agency in the global production network [50,51,52] and in the agri-food sector [30] shed a new light to this direction of research but no study has examined workers’ empowerment and agency in a manufacturing context of a multi-layered supply network. This study aims to advance the understanding of this issue by examining, from the workers’ perspective, CoC implementation at the bottom of the supply chain.

2.4. Employment Relation: Negotiated vs. Reciprocal Exchange Perspective

CoC advocates the application of effective collective bargaining and unionism similar to the model of employment relation in the West [53,54], with a formal structure and procedure in place to enable meaningful bargaining with employers. From the social exchange perspective, this form of collective bargaining tends to represent the direct negotiated exchange in which actors jointly negotiate the terms of an agreement that benefits both parties, either equally or unequally [55]. Unions, on behalf of workers, negotiate with management on the terms and conditions of the work and benefits for their members. In this situation, the benefits for workers are pre-determined and agreed upon [56,57]. However, research which adopt this conception of collective bargaining show that this form of labour activism at the bottom of the supply chain remains problematic [5]. This is because some preconditions, such as the recognition of injustice and the willingness to form and lead collective actions, which set a foundation for effective collective bargaining [58], are yet to be materialised at the workplace.

Another perspective in the social exchange literature is direct reciprocal exchange in which actors perform individual acts that benefit another, such as giving assistance or voluntary collaboration, without negotiation and without knowing whether or when or to what extent the other will reciprocate [55]. Relations of reciprocal exchange evolve gradually whereby trust and solidarity between both parties develop, hence, reinforcing the relationship [59]. Unlike negotiated exchange with a bilateral agreement in place, reciprocal exchange is unilateral and has some degrees of risk of nonreciprocity which sees the actor who gives benefits to the other receive little or nothing in return [55]. However, research on reciprocal relationships has shown that reciprocal exchange produces more positive effects on trust, affection, commitment and solidarity than negotiated exchange.

It could be argued that in the case of CoC implementation where workers assist management (either voluntarily or being forced to do so) to hide non-compliance practices [20,23], they (intentionally or unintendedly) enter a reciprocal exchange. Whether or not workers could receive a reciprocal benefits from management might depend on many factors but existing literature on reciprocity has suggested that trust and empathy make both parties more committed to maintain a positive relationship [60,61].

While reciprocal relationships are well studied in sociology and organisational literature [55,59,60,61,62], an understanding of its place in employment relations in the global supply chain context is limited. Most discussions of workplace unionism and collectivism in this field tend to employ the conventional means of collective bargaining in the form of negotiated reciprocity [55]. This paper therefore aims to address this gap by exploring whether reciprocal exchange is an alternative form of bargaining.

3. The Clothing Manufacturing Industry in Vietnam

Labour cost in Vietnam, based on statutory minimum wage, is lower than neighbouring countries in the Southeast Asia region. According to the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) report in 2015, compared to major clothing manufacturing countries in Southeast Asia, the minimum wage in Vietnam across four regions was approximately $121/month, lower than Cambodia and Indonesia while being only approximately half of the minimum wage in China, Thailand and the Philippines [63]. Although the minimum wage is set to increase every year at approximately 5% per annum1, the current wage for Vietnamese workers is still considered significantly less than it is in China (ibid.). This perhaps places Vietnam in an attractive position in the global supply chain, becoming one of the top exporters of clothing products [64].

Since 2014, the garment industry in Vietnam has experienced two digit growths year on year, reaching a total export value of US$30bn in 2018 [65]. The major contributor to this growth is the foreign direct investment (FDI) sector which accounts for 60% of the total value, while only representing 25% of the number of garment and textile enterprises [66]. As of 2017, there were 8770 garment and textile companies in Vietnam (compared to approximately 1000 in 2001) (ibid.). The majority of these enterprises are privately owned enterprises2, established as a result of the privatisation of state-owned companies in the post-Soviet era [66]. It is estimated that approximately 1% of the companies still have the state as a majority shareholder [67]. These statistics show that although the industry is dominated by domestic enterprises, their combined export revenue is significantly less than FDI companies. The reason for this discrepancy could be explained by the type of manufacturing process that most Vietnamese companies are subcontracted to do.

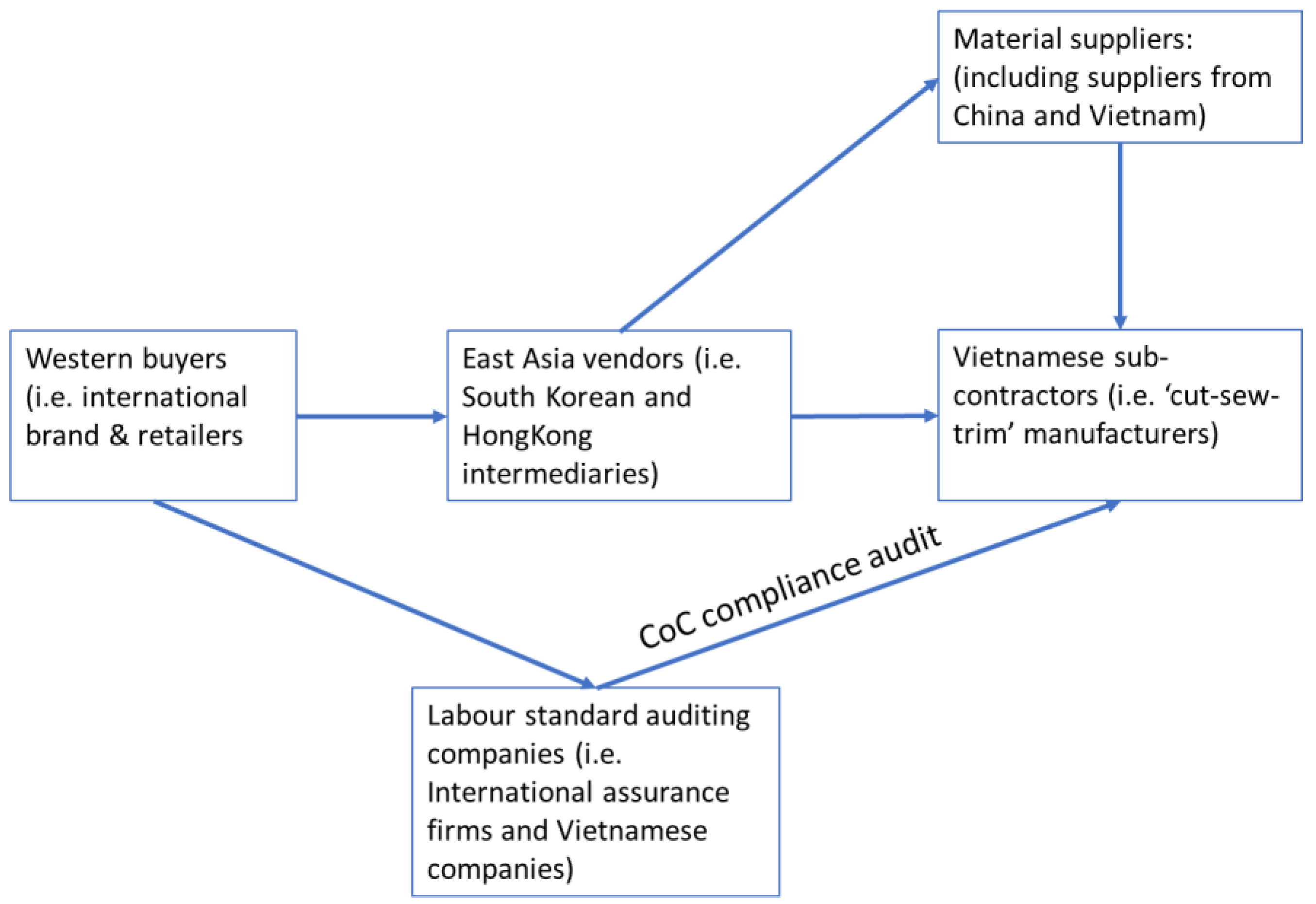

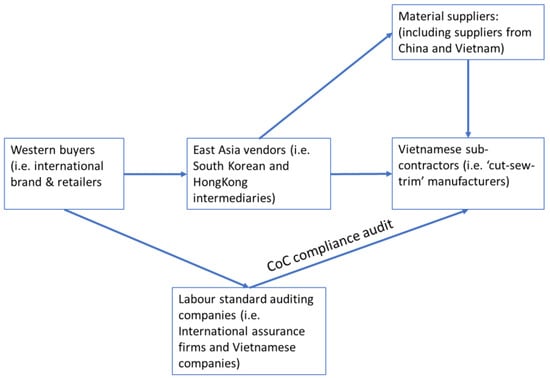

Most Vietnamese producers are ‘cut-make-trim’ subcontractors to East Asian companies, called ‘vendors’ who have direct contracts with Western brands and retailers [68], as illustrated in Figure 1. It is estimated that 70% of total clothing export from Vietnam is produced through ‘cut-make-trim’ orders, while only approximately 9% have direct contract with brands and retailers [69]. The industry employs approximately 2.5 million workers, of which more than 80% are female and 75% are unskilled and untrained workers [70] due to the fact that the majority of the manufacturing work is sewing. CoC compliance audits at Vietnamese sub-contractors are conducted by third-party audits, commissioned by Western buyers [23].

Figure 1.

Position of Vietnamese producers in the supply chain.

There is only one recognised trade union in Vietnam, which is rather a political arm of the ruling Communist Party than a truly workers’ representation body [71]. Most industrial actions are wildcat strikes without going through the formal procedure stipulated by the trade union law, but interestingly, these disputes are mostly over pay and working conditions rather than asking for freedom of association and collective bargaining [72]. CoC introduced by Western buyers consist of nine core areas of labour standards including workers’ right to form or choose their own union (as summarised in the Table 1). Nevertheless, the right to freedom of association is superseded by the national law.

Table 1.

A typical supply chain Codes of Conduct (CoC).

4. Research design

4.1. Case Selection

To understand the implementation of CoC from the workers’ perspective and to identify the role workers play in such contexts, this research employs an explorative approach through a case study [73]. Case studies are well suited to answer ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions and allow for in-depth and context-rich analysis [74], which has been commonly adopted by a number of research studies in this field, for example, [5,9,12,75,76,77,78]. While a case study does not allow for the generalisability of the findings, it enables the collection of rich data which may not have been possible to obtain through other methods, given the commercial and ethical sensitivity of the topic.

To increase the generalisability of the case, the selection criteria for the case was set to reflect what Flyvbjerg [79] refers to as a ‘critical case’. In this approach, the selected case does not only share key characteristics of the industry but is also in a favourable setting. According to Yin [80], if a company in the favourable setting is not in compliance with CoC, it is reasonable to assume that other companies operating in less favourable settings are not in compliance either. Hence, a critical case approach provides a way to generalise from a single case through logical deduction [79].

In this study, the case study is selected based on three main criteria. Firstly, the producer must share the main characteristic of the clothing manufacturing industry in Vietnam as being a sub-contractor to Western buyers doing ‘cut-make-trim’ work. Secondly, the producer is subjected to implement and comply with CoC in their factory premises. And finally, the producer should be an established company with a workplace union as this will allow a fuller understanding of workers’ views of CoC as well as of their union which might be absent in newly established companies, hence in a less favourable setting.

A convenient sampling technique was employed because of the concern that producers may be reluctant to share sensitive information on CoC compliance with the researcher. In many previous CoC research studies, access to producers was predominantly obtained through international brands as a buyer, who introduce researchers to one of their suppliers, e.g., [12,20,29]. This top-down approach may impact on data collection in that factory management and workers could be reluctant to share the views which they do not want their buyers to know. In this study, the author applies a bottom-up approach which identifies a clothing producer making clothes for well-known international brands.

The process of identifying clothing manufacturing companies started with the identification of industrial zones with high concentrations of manufacturing companies as they tend to be export-oriented producers and are likely subjected to CoC compliance by buying clients. Due to logistic constraints, only three garment companies in three industrial zones in the northern provinces, approximately 45 to 90 miles apart, were identified. The researcher then used personal networks, such as connections from local friends and professional networks to get in touch with the management of the factories. An alternative gatekeeping access was considered such as through trade union representatives at the national and regional level. However, after consultation with the union representatives, it was apparent that this route would not lead to an open conversation with the management due to possible tension between management and union in some companies.

Attempts to get in touch with the three identified companies were first made by the gatekeepers who personally know the managers. This was followed by the researcher sending information about the research project, the anonymity and confidentiality assurance which were approved by the university ethical committee. All three companies were reluctant to participate due concerns of the confidentiality of their practices as they all admitted that their companies did not fully comply with buyer’s CoC. Success in gaining access to only one company, which is hereby referred to as VCo, was mainly because one of the gatekeepers managed to persuade VCo’s top manager, which led to his agreement to participate for academic purposes.

As case study requires in-depth information. It is vital that the company fully participates and shares information on its policies and practices. The trust and confidence gained through the gatekeeper’s access enables the management to share their views more freely without fear of being identified by their buyers. Since this study aims to understand workers’ views and their roles in CoC implementation, it is important to capture rich and reliable data as well as data from various sources which allows triangulation [74].

4.2. Data Collection

A total of forty semi-structured interviews were conducted at VCo during the period July–August 2016. They included interviews with two senior managers, one chairperson of the workplace union, and thirty-seven women workers. Details of the sample are presented in Table 2. On average, each interview lasted between 45 and 90 min. Interviews with managers and the union chairperson were conducted face-to-face at VCo’s office, while interviews with workers were partly via telephone and partly face-to-face, conducted outside the factory premise and after working hours to suit workers’ busy work schedules. Semi-structured interview data were collected from three different perspectives, management, union and workers, allowing triangulation and, hence, reinforcement of the validity of the data [81,82].

Table 2.

Summary of the interview sample.

VCo managers and the union leader were aware that the researcher sought to interview workers outside working hours but were not aware of the individual workers who were contacted and participated in the research. Approaching workers was more difficult than anticipated as most workers did not finish work until late in the evening and usually worked six to seven days a week. Contacts with workers were obtained through a convenient sampling where workers were randomly approached in person in several residential areas near the factory premise. After an initial meeting, the researcher arranged an interview schedule with workers at a time of their convenience. This approach enabled the researcher to establish rapport with the interviewees before the interviews took place, which is an important step to acquire detailed and comprehensive information from interviewees [83,84]. In total, fifty-five workers were approached and agreed to being contacted again to arrange an interview but, for unknown reasons, only thirty-seven responded in the subsequent arrangements.

Twenty-two interviews were conducted face-to-face at the workers’ residences, while the remaining were conducted via telephone. The reason for this was because these workers either have young children or family responsibility which takes up their non-work time and makes it impractical to arrange a face-to-face interview late in the evening. Therefore, telephone interviews were the most suitable method for collecting data. Most of these telephone interviews were conducted at approximately 21:00. This arrangement did not weaken the credibility of the data as researchers and interviewees have met face to face and in most cases have been exchanged text messages and phone calls several times, hence developing good rapport, prior to the interviews. All interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed with interviewee’s identities being coded as presented in the Appendix A.

Ethical issues were taken into account, whereby all interviewees were informed about the research and the sensitive nature of the topic, i.e., CoC compliance. They were made aware that the research data when reported will be anonymised to keep the company’s and individuals’ identity confidential. Nevertheless, interviewees were informed that they could withdraw from this study whenever they wished to do so.

4.3. Data Analysis

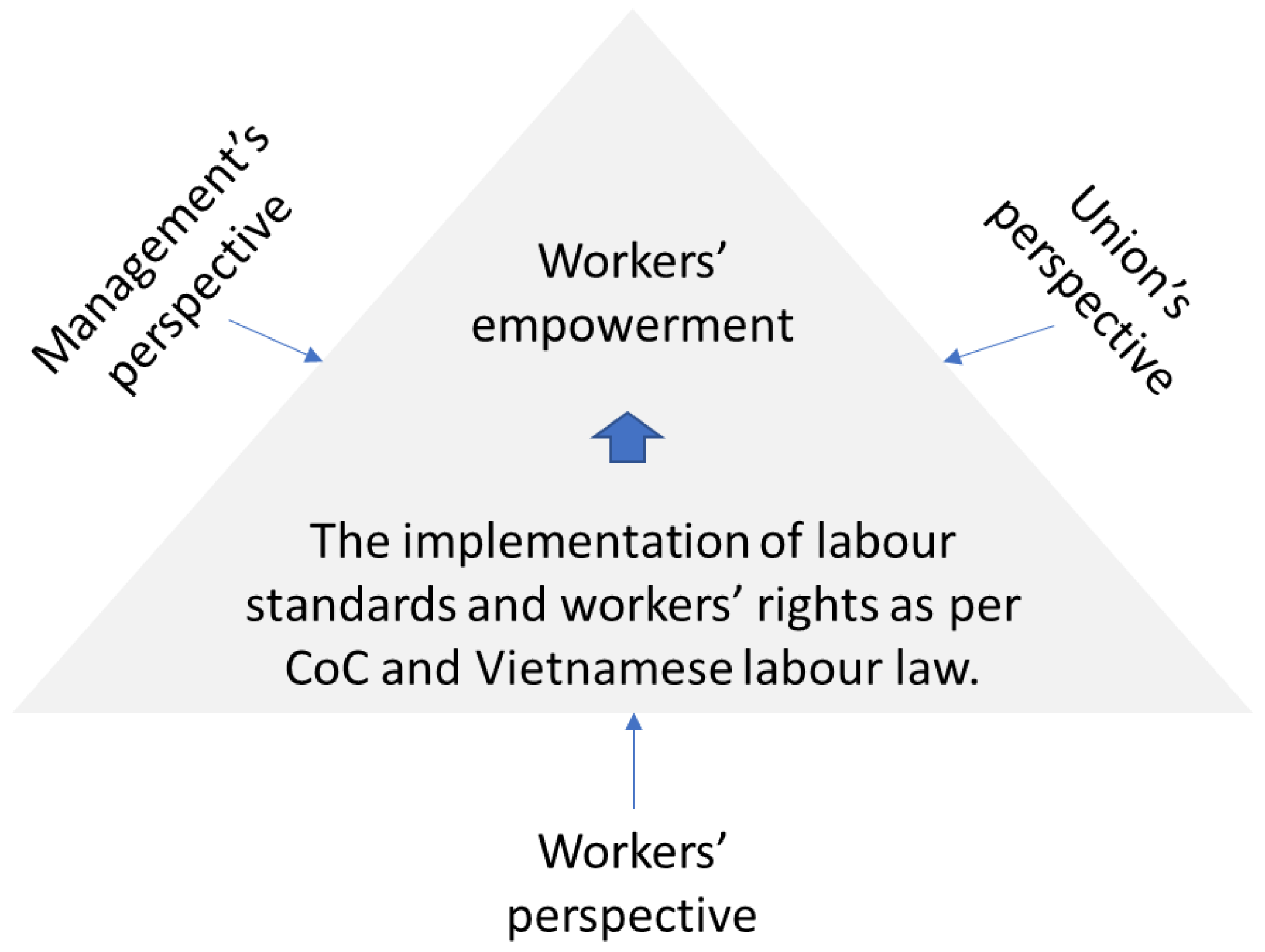

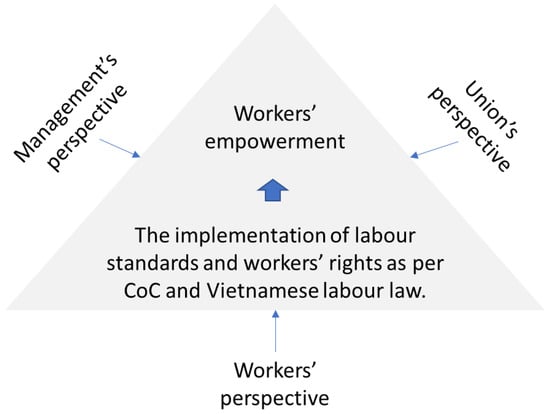

The analysis was guided by the research questions to investigate: (1) How is CoC implemented in the factory? (2) What roles do workers play in the implementation of CoC? (3) What is the nature of labour activism and collective bargaining at the bottom of the supply chain? The research employs thematic analysis and Nvivo was used for coding and organising the data into themes, whereas the process of integrating and triangulating various sets of data from management, union and workers was done manually (as illustrated in the Figure 2) using a mapping procedure proposed by Richie and Spencer [85].

Figure 2.

Data triangulation.

5. Findings

5.1. Overview of VCo, CoC and Vietnam Labour Law

VCo was established in 1967 as a state-owned enterprise. In 2004, the Ministry of Industry and Commerce announced VCo’s privatisation of 49% of the shares, while the government kept 51% under a state-owned corporation called The Vietnam Textile Corporation (Vinatex). However, in 2010, the government sold all of its shares at VCo, making the company a fully privatised enterprise. VCo is located in one of the most industrialised provinces in Northern Vietnam. Being in the heart of the manufacturing zone, VCo could attract workers not only from local and neighbouring districts but also from far afield. However, VCo also faces fierce competition with other manufacturing companies for a quality workforce as the company expands its production capacity.

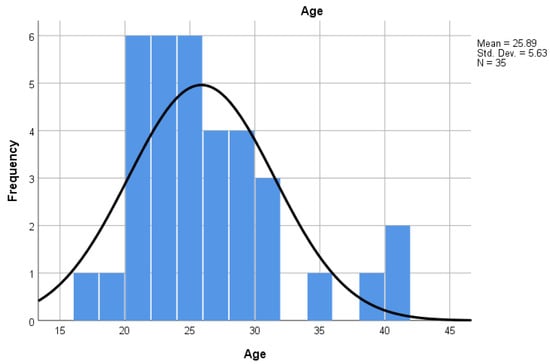

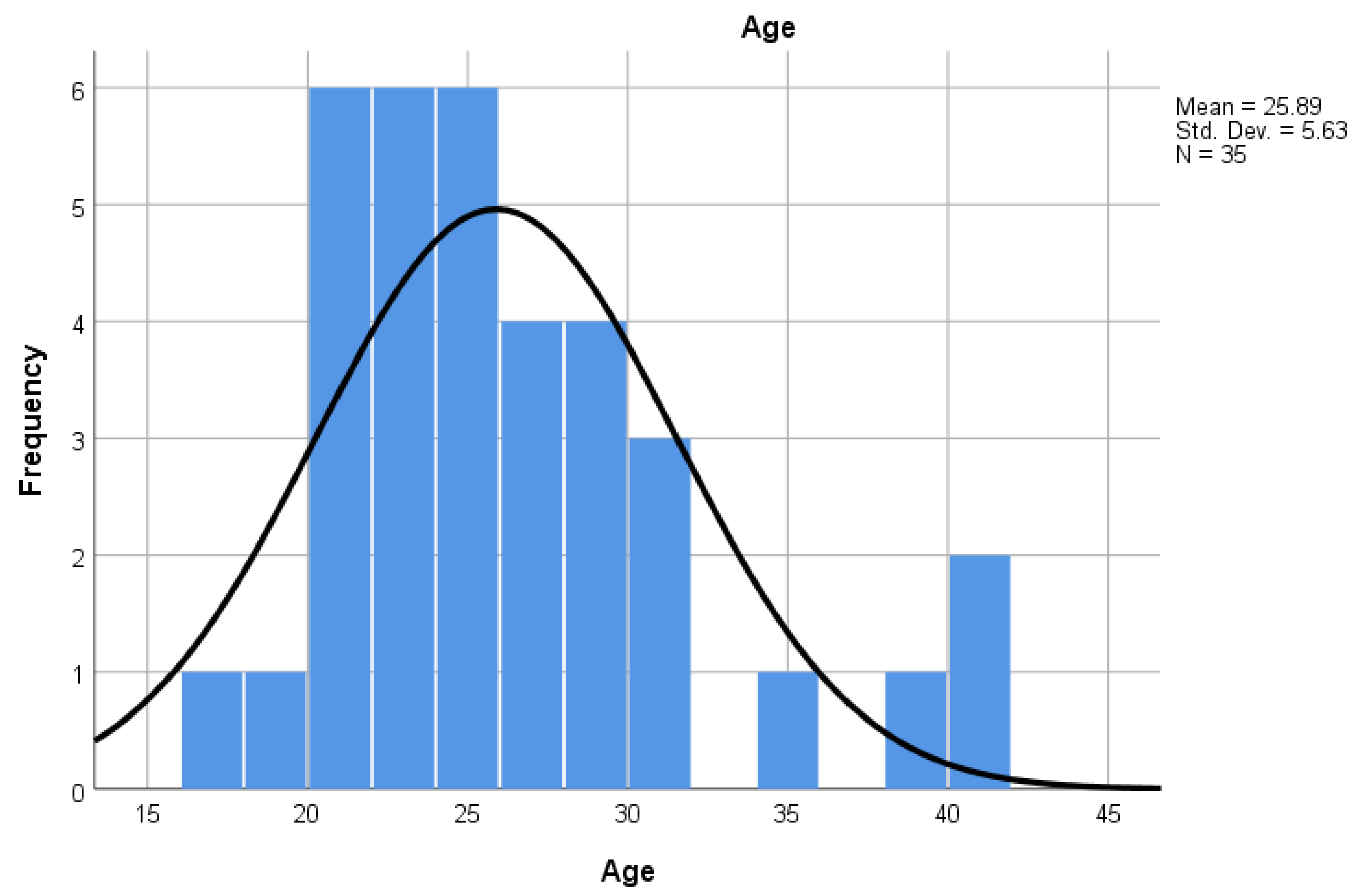

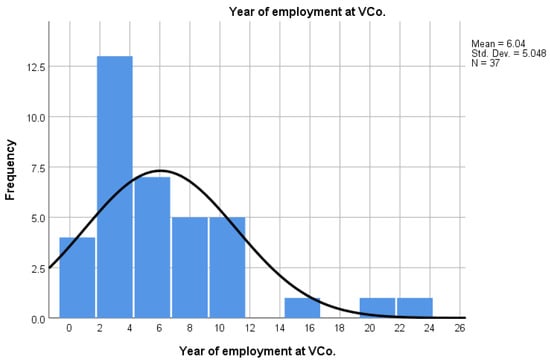

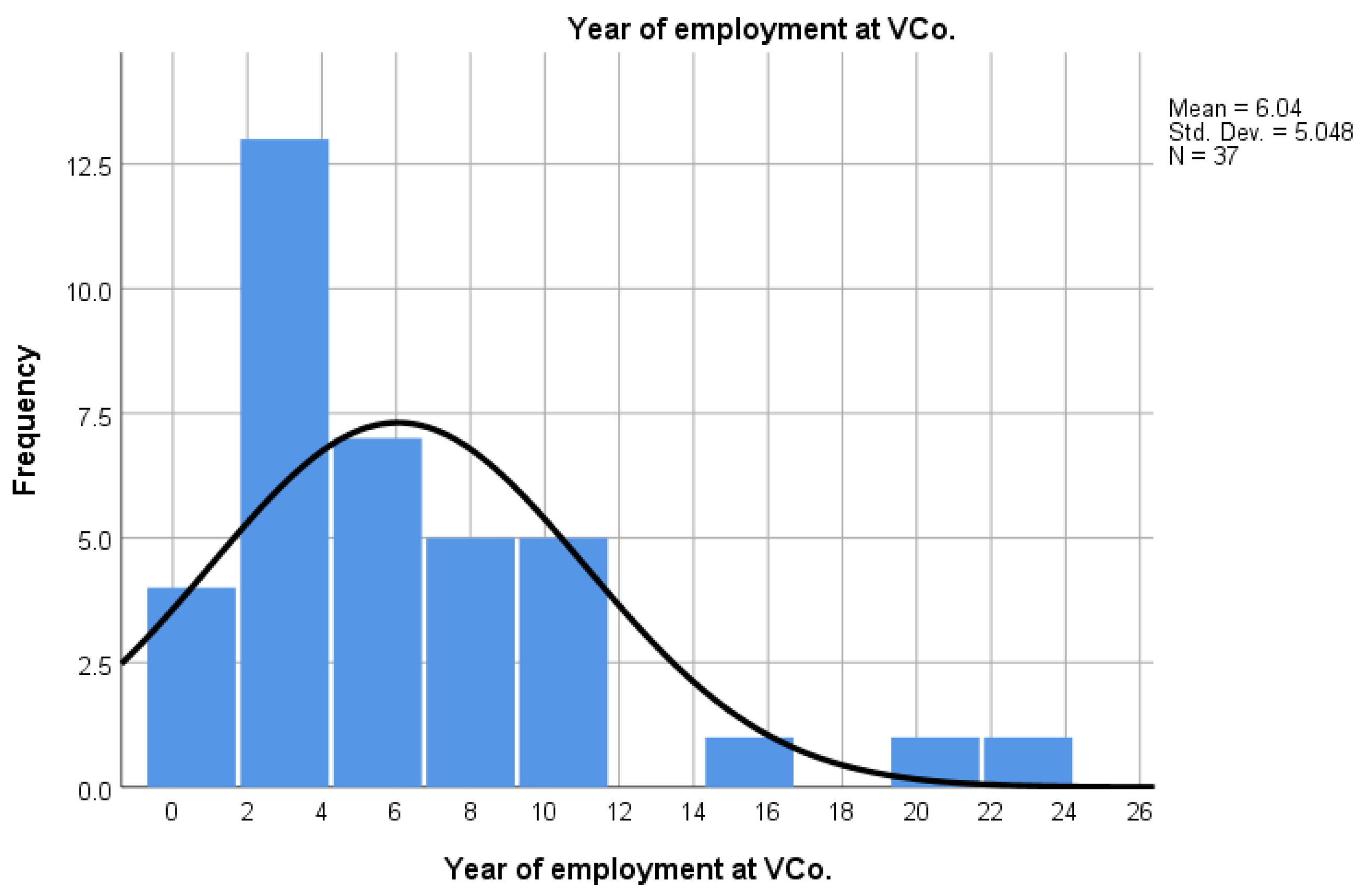

The company has approximately 2300 workers, of which 85% are women, working in its main factory where the company is headquartered. A total of 80% of the workers are working in sewing lines, while the remaining are in various positions from cutting to stock keeping. The average age of the workforce is 27 years due to a large number of new recruits and since older workers left after VCo was privatised. As shown in Appendix B and Appendix C, the average age of workers in the sample is approximately 26 years and the average year of employment is 6 years, with some workers having just started, while others have been with VCo for over twenty years. This distribution, to some extent, reflects the characteristics of VCo’s workforce. Whilst the small sample size is not meant to be representative, interviewing workers from a wide range of ages, employment duration and positions in the factory floor offers a balance of breadth and depth to the data.

One hundred percent of VCo’s products is for export and it makes clothes for approximately 30 to 40 international brands, the majority of which are US and EU brands such as Gap, Wal-mart, Target, Kohl’s, Timberland, C&A, Zara, Next and H&M. VCo never has a direct supply contract with these brands. Instead, all of its supply is made by orders from Singaporean, Hongkong and South Korean vendors, which have offices in Vietnam. These vendors also have buying and quality inspection personnel regularly on site to monitor the orders.

VCo is subjected to multiple CoC introduced by their large portfolio of brand clients. All CoC cover at least nine areas of labour standards as mentioned in Table 1, including child labour, forced labour, discrimination, harassment, employment security, freedom of association and collective bargaining, working time, wages, health and safety. CoC may differ from one to another in detailed requirements but all of the codes recognise Vietnamese labour law which is to a large extent aligned with international labour standards, except that Vietnamese law restricts workers’ freedom of association and collective bargaining. This restriction means workers are, by law, not allowed to form a union of their own choosing, but they are free to join the government-led trade union. Similarly, collective bargaining is allowed if it is carried out via the government-led trade union. Moreover, collective labour disputes must go through a regulated procedure before any lawful industrial action (i.e., strikes) takes place. Hence, as far as workers’ rights are concerned, enterprises in Vietnam are bound to fail on compliance to this CoC standard. Nevertheless, this conflict between the local law and CoC is treated lightly by most brands and retailers. Interviews with factory managers confirm that as long as they do not interfere, obstruct or discriminate against workers pursuing their lawful actions, they will pass the compliance test for this standard. In fact, VCo could also get away with its dysfunctional workplace union where the union chairperson is also the Deputy Head of the Business and Marketing department.

There is another difference between the labour law and CoC, which is the working hours. Vietnamese labour law stipulates 48 regular working hours per week and allows up to 50% overtime, but no more than 30 h of overtime per month or 300 h per annum3. CoC standards, however, on the one hand allow a range from a 60- to 72-h working week depending on the brand, while on the other hand, they recognise and uphold the local standards, which is stricter in this case. Managers and union representation from VCo confess that they never manage to comply with the working hour standards but argue that this is the ‘industry’s wide problem’ and is not just a problem at VCo. Through many audits and feedback from clients, managers have also learned that brands and retailers are not as concerned about the hours as they are about whether the workers receive appropriate overtime rates, which is 150% on a weekday, 200% on a weekend, 300% on a national holiday and a proportionately higher rate is applied for overtime work during night time4. The presence of CoC has been considered as a complementary measure to the weakly enforced national labour law. However, the effectiveness of CoC remains problematic [23].

VCo receives frequent unannounced audit visits from various brands. Depending on an individual client’s requirements and the audit results, a repeat visit in between four and twelve months is scheduled to monitor improvements in compliance. The production manager commented that VCo tries to meet the CoC standards but realistically they could only fulfil some of them. However, with collaboration of workers, VCo manages to hide their non-compliance practices and pass most of the clients’ audits.

Non-compliance and tactical deception are not unexpected as previous studies have reported many deception tactics used by suppliers to pass clients’ audits e.g., [20,25,86]. However, in contrary to our existing knowledge that workers are often being forced to lie to auditors to avoid being punished by the management, findings from this study show a high level of collaboration between the workers, union and management in deceiving labour auditors. In the next section, this paper will present various underlying rationales that motivate workers to collaborate with the management to defy their clients’ CoC, the very mechanism meant to protect them.

5.2. Workers–Management Collaboration

Throughout the interviews, managers, the union leader and workers openly acknowledge that VCo did not comply with many labour standards stipulated in the labour law and CoC. Table 3 presents an overview of CoC compliance by VCo.

Table 3.

Summary of CoC compliance at VCo.

5.2.1. Mandatory Overtime

In principle, workers must not be forced to work more than the regulatory 48 h per week. But workers at VCo do not have a choice. By way of explanation as to why overtime is compulsory, the production manager pointed out that a garment is assembled using dozens of operations and each worker is trained to work on one or two specific ones, and therefore it is impossible to operate half a sewing line. Although workers are aware of their rights, they seem to accept the justification as ‘reasonable’ as they all believe that overtime is the nature of the garment industry. Workers often compared their conditions to those of other garment factories and could see no better alternatives. All workers, when being asked about mandatory overtime, shared a common expression that ‘everywhere the same’. They are not convinced that voluntary overtime was practical to low skill jobs such as sewing clothes. For that reason, they collaborate with management to sign overtime forms in bulk, as one said: ‘every now and then they [line manager] give us a pile of form to sign, so much that my hand ached […giggle]’ (SW19).

‘We all signed a lot of blank forms, I don’t remember what I have signed, they just look the same and I don’t really pay attention to it very much’.(SW14)

5.2.2. Use of Underage Workers

Interviews with the union leader and workers also reveal that the factory sometimes uses underage workers during summer months. But this is mainly because workers and staff want their children to earn some cash to fund school necessities and so, at the same time, they can keep an eye on the youngsters during the summer break. Children as young as 13 years old could work, ‘helping out on light jobs like cutting threads, moving clothing items down the production line, etc.’ (TL35). VCo managers commented that this is a ‘legitimate demand’ by workers but Western clients do not understand. All workers, union and management seem to be aware of the seriousness of this violation as it could lead to the termination of contracts. However, a coordinated effort was used to hide this practice from auditors. The union leader shares that auditors could make an unannounced visit anytime but workers on the factory floor only need a few minutes to discharge the minors through the back doors when auditors register their visit with the security guard at the front gate.

Young workers aged 16 and 17 years old are also employed permanently at the factory. One of the young workers being interviewed said she had worked at VCo for 6 months when she was only 16. The worker shares that she wanted to apply to a foreign direct investment factory close by, but it did not accept worker under 18. Many of her friends fake their IDs to get jobs. According to the worker, VCo is a Vietnamese company therefore the management seems to be more ‘understanding’. She said:

“We don’t have to use fake IDs here … but we must not disclose our real age to auditors… Every time I hear the auditors coming I am shaking. I am very scared if they call me for interview. I am afraid I would say something stupid that revealed my real identity”.(SW9)

5.2.3. Health and Safety

Unlike some descriptions of women workers working under poor conditions such as too much heat, too little light and being locked up in the factory, etc., e.g., [22,87,88], it emerged in this study that VCo workers do not seem to suffer any of these hardships. On the contrary, all those interviewed reported their working environment was cool, nice and clean. From the researcher’s own observation, the factory has proper safety and exit signages. According to the production manager this is one of the areas in the codes that VCo always passed the audit, explaining that he cannot afford to let workers sweat, because it is likely to damage fabrics or that it was important to have sufficient light so that workers could see their sewing clearly. Consistent with some previous studies, e.g., [5,8], most of the observable benefit-based standards tend to have significant improvement, while right-based standards are difficult to detect or enforce.

5.2.4. Discrimination

At the time of the field visit, the factory had a vacancy advertisement at the gate saying the factory is recruiting “women workers aged between 18 to 25”. The production manager made a remark that he did not want male workers, because sewing is not a ‘male’s job’ and that “women are much faster and more diligent”. The reason for the age limit was because of the management’s perception that:

After 30 [years old] productivity decreases. The golden age is between 20 and 30 so if they have had about 15 years of work then they should go.(Production manager)

He shared that the factory aims to gradually discharge ‘old workers’ by asking them to sign up to voluntary redundancy or to transfer 35+ workers to doing other jobs. The 41-year-old team leader said in the interview that she was the oldest person still sewing in the production line (TL35). Another 40-year-old worker (SW18) said she was lucky to get a job at the age of 32 only because the factory expansion was built on her family’s agricultural land so that the local authority made a deal with the factory to employ those affected.

Most interviewed workers thought the age discrimination was ‘normal’ as it was a ‘common practice’ for every company to set criteria of who they want to employ or what job is suitable for certain age group. In addition, workers share similar views as the interviewed manager that sewing is not for mature workers as it would take longer time for them to learn the job and perhaps their performance would be slower compared to younger workers. Even those in their 20s would not see themselves still working on the factory floor in ten or fifteen years’ time. One said:

‘Well, I don’t know if I would be able to continue working like this when I am older. I am already exhausted after three years working here. I can see myself working as a garment worker when I am 30s something’.(SW16)

5.2.5. Harassment and Abuse

There is no report from the interviewed workers that they have experienced or witnessed any form of harassment or abuse at VCo. But some workers said that they have seen workers being told off by team leaders because they were chatty and slow. Others were also being told off because they failed to conceal non-compliance practices when being interviewed by auditors, resulting in the factory being put on notice by clients. Nevertheless, none of the workers considered this as a form of bullying by management.

Interviews with managers and the union leader also show that the management seems to be sympathetic with workers because auditors are ‘very skilful’ and often ask workers ‘tricky questions’ in order to detect inconsistencies and noncompliance practices. According to the production manager:

“They [auditors] sometimes come into the workshop and pick young naïve looking girls to ask about working hours, pay and other issues. These girls are not very good in lying so they [auditors] found out and put us on notice for improvement”.(Production Manager)

As a result, managers, the union and workers themselves coach new workers on how to respond to auditors’ interview questions.

5.2.6. Regular Employment

At the time of the study, VCo had been through a period of significant growth and was planning to open a new factory site a mile away from the existing one. The business development manager shares that the company has received more orders from clients and VCo is constantly recruiting new workers. In order to attract workers, VCo offers a competitive employment package, including long-term employment contracts and competitive pay. Several workers who at the time of the interview had worked for VCo for less than three years commented that they did their research and compared pay and work conditions in several factories before taking the job offer from VCo. None of the interviewed workers thought their job security was under threat.

5.2.7. Working Hours and Overtime

The working hours standard has always been a sticking point for VCo. But with the collaboration of workers, it manages to pass clients’ audits. A worker said:

We sign a blank overtime form every week. They [managers] will then fill in a smaller number of hours. If, say, we work until 8 pm, they put down as 6 pm… to make it realistic.(SW18)

Most workers are unhappy with the amount of overtime they have to do every week. According to the union leader, sometimes workers protest not to work long hours during weekends and the management has to back down. However, workers are willing to falsify the record or lie to auditors in order to protect the management. Interviews with workers show two reasons why workers choose to side with the management. First, they do not believe excessive overtime is entirely the management’s fault. Workers tend to blame their buyers and vendors who set a tight deadline and are unreasonably demanding. One said:

‘Vendors often brought in materials late and still asking us to complete the order on time’.(TL30)

The business manager explains that VCo only does ‘cut-make-trim’ contracts through vendors, so it relies on vendors to supply materials such as fabrics, threads and accessories. Sometimes these supplies arrive late, while the deadline to ship clothes is already fixed, therefore workers are forced to work longer hours to complete the order on time.

The second reason is that there is a sense of collective responsibility for VCo to pass clients’ audits as workers themselves are unconvinced that being audited would make an improvement to their pay and work condition. In addition, workers also dislike the presence of auditors at the factory as one said:

‘It’s worrying and disruptive when they are around, no one likes them. We sometimes complain about vendors to the auditors but nothing happens’.(SW5)

5.2.8. Wage and Benefits

VCo applies a piece rate, which means workers earn their wage based on their productivity. All interviewed workers claimed that their productivity is significantly affected by the types of products and orders, because nowadays they have to switch from one order to another more frequently as a result of an increasing number of small orders and varieties of products. When asked about their wages, a common term expressed by nearly every worker was ‘depending on orders’. Consequently, these workers expressed a preference for large orders which last for a couple of months rather than weeks, for this allows for productivity build up and hence leads to a higher income. However, workers are disappointed that most orders nowadays just require two to four weeks labour, making them constantly on a learning wage.

The unit price paid by vendors is also an important factor that determines the piece rate and thus affects workers’ incomes. With respect to this, some workers claimed that when they achieve high productivity for certain products, vendors gradually reduce the unit price, so workers end up working more for the same income.

We complain to the management, they said because clients [vendors] know we can do more so they cut the price. They wander around here everyday spying us.(SW27)

In fact, most workers were of the belief that their income and working conditions are contingent on clients’ orders instead of management’s behaviour. One said: “some orders are paid so low that we hardly can earn higher than the minimum wage” (SW21), whereas another pointed out that, a “good order” which pays a high unit rate can provide workers “quite a good income” (SW4).

Management also use piece rate pay as a justification for not paying overtime rate. Pay fluctuations and the direct connection between the unit price paid by clients and piece rate wage seem to further workers’ impression that their conditions have much to do with their employers’ ability to win good orders and this tends to increase their support for management. That is, most interviewed workers are enticed by managers to believe that the clients are hypocrites about asking for improved working conditions, when they refuse to offer better deals, such as higher prices and relaxed delivery time.

“Our managers told us if the clients knew [CoC violations] they would ask the factory to do loads of corrective actions, but they won’t offer higher price, so it won’t help”.(SW31)

In sum, the piece rate mechanism aligns workers’ interests with those of their employers’, thus, increasing their loyalty and consequently their willingness to conceal CoC violations practices.

5.2.9. Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining

As mentioned in the previous section, workers’ rights to form unions of their own choosing is restricted by the labour law. The union at VCo is fully registered and relatively well established with a chairperson and several executive members as well as a union representative in each production line. By definition, the function of the union is to represent and protect workers’ rights and interests, as stipulated in the Vietnamese Constitution of 1992, Article 10, but, in practice, VCo’s union is another arm of management. This system is inherited from the time VCo was a state-owned enterprise and the role of the union was to support the management in organising training for workers, with an aim to improve skills and productivity. The union chairperson is also the Deputy Head of the Business and Marketing department, making the boundary between union and the management even less clear.

According to the union chairperson, CoC auditors do not accept that she is involved in the managerial role and advise her to be fully representing the union and workers’ interests. However, in defending her position, she argued that by being part of the senior management team she knows what the strategic and operational direction VCo is pursuing and can have a say on behalf of the workers. If she gave up that role to be an independent union representative, she feared she would never be invited in management meetings and would not have the insight to be able to support the workers. However, the union chairperson admitted that her job is not entirely about representing and protecting workers’ rights, but ‘educating’ workers about the business and what can be reasonably achieved.

To be fair, sometimes workers just have unrealistic demands, you know, and I’ve got to tell them that they’re not going to get what they want all the time.(Union chairperson)

The union’s main activity, funded by the management, is to organise competitions on productivity between production teams. Their moto is to encourage workers to work harder and faster so that their income level could be improved. They offer cash rewards to the most productive workers and the most efficient production teams.

It is notable that despite the close link between union and management, the VCo union remains very popular. The union chairperson said 95% of VCo workers are union members. The other 5% are mainly those who have just started and not yet registered. This is also evidenced in that 36 out of 37 interviewed workers were members of the union. Unlike unions in the West, where the primary function is usually to do with bargaining, the union at VCo, as workers described it, operates mainly as a social club for their members. The union uses members’ fee, equivalent to approximately US$1 per member per month, to organise activities including: buying colleagues birthday and wedding gifts, organising workers’ social activities and offering counselling and financial support to workers and their families on occasions of illness, births or funerals. These forms of social support are psychologically, culturally and in some cases financially significant to many workers and thus motivate them to become union members.

Most interviewed workers appeared to judge union representatives according to the way they carried out such social activities, rather than their performance in representing their employment demands. In fact, many of the interviewed workers sympathised with their representatives, not expecting them to undertake their true role as it could lead to the risk of them being marginalised by the management. A worker said:

‘We pick someone who, you know, kind of knows how to say things clearly so they can pass the message on to the management. If we expect them to do more than that, no one would want to do that job’.(SW33)

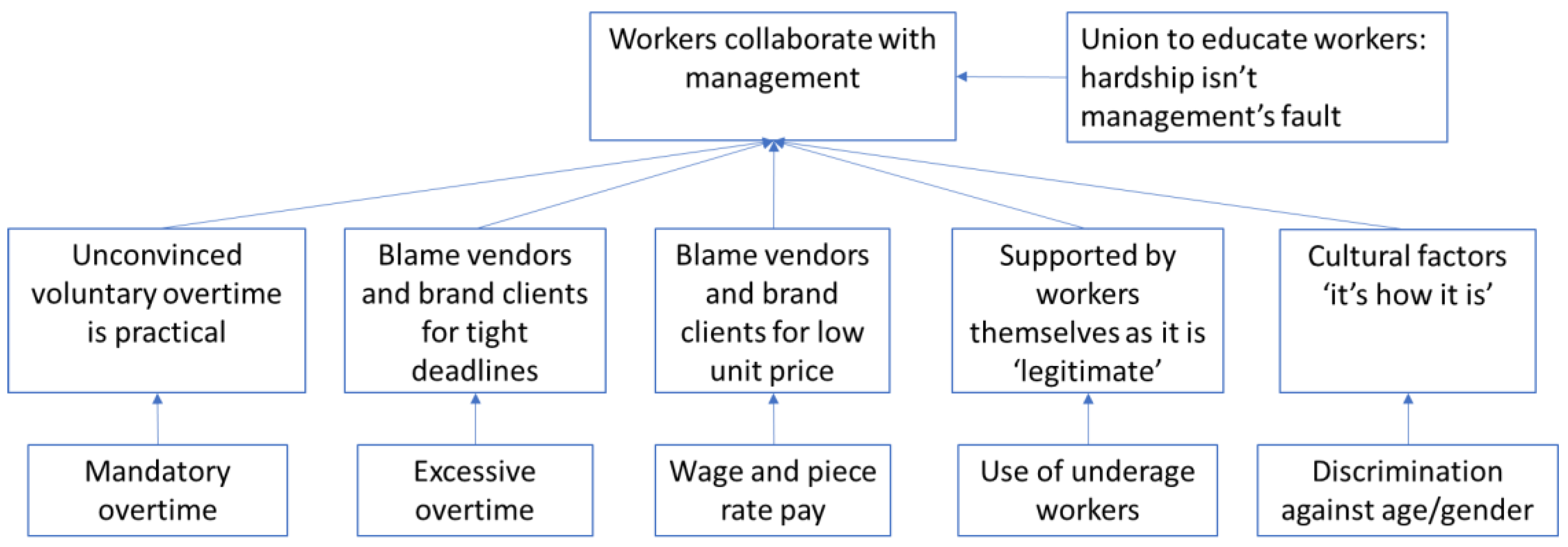

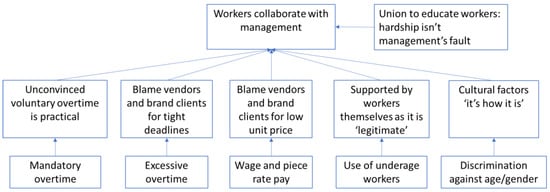

In summary, the findings as illustrated in the Figure 3 show that workers are motivated to collaborate with the management to deceive on non-compliance practices for several reasons. Workers are unconvinced of the CoC requirements and put the blame on buyers for their hypocritical and unreasonable demands. Workers are also subjected to their own social and cultural constraints, whereby unfortunate labour standards such as underage work and discrimination are considered as ‘normal’ or acceptable. Their perception of the employment relations is to a large extent influenced by the management-led union’s propaganda that working conditions are not always dictated by the management.

Figure 3.

Reasons workers collaborate with management to hide non-compliance practices.

5.3. Worker–Management Reciprocal Exchange

A significant finding from this study shows that, externally, workers are united with the management, but, internally, there is tension. Workers are not afraid of voicing their complaints and demands to the management. Most interviewed workers commented that they voiced their concerns to management through union reps at their production team, who they elected to represent them. Workers acknowledge these union reps do not have any negotiating power, but they could act as messengers. One described:

They [union reps] attend meetings and record what managers say and then report back to the workers.(SW11)

When we want to complain or propose some changes, we talk to the union reps and they pass it on to the management.(TL2)

Unlike the description of workers a decade ago as victims, weak and passive, who obey their employers due to a fear of being fired or punished [20,89,90], interviewed workers at VCo are not hesitating to complain and protest against the management by slowing down, work stoppage or not turn up to work if their demands are not sufficiently addressed. Some interviewed workers gave examples that workers refused to come to work on Sunday. Through the union, workers request a ‘red line’ to be established that they should have a Sunday off work regardless how urgent an order needs to be completed. A worker said:

Since privatisation the management just wanted us to work harder and harder. At the beginning we were okay with it because we also could earn more but we all had enough of it now. We need to have a life and time for family. We won’t do it anymore.(SW32)

Workers also complain if they perceive pay rates for some orders as inadequate. One worker shared that sometimes her team has a difficult order which took a long time to complete and with the piece rate pay they took home just barely the minimum wage. They complained to the management and eventually got a top up of 30%. According to the business manager, VCo often has to accept low paying orders from big brands such as Gap and Wal-Mart in order to improve their business profile. The big brands have strict requirements on quality control but do not pay higher to compensate for the time-consuming production. Workers in general do not want to take those orders.

Some orders were complex with many details and took long time to complete. The more famous the brand name, the more difficult it is. Vendors are tough with quality control too. I am not as experienced so sometimes my wage is very low because of that. None of us want to do such orders.(SW22)

Workers do not always get what they want but we make sure that there is a balance amongst production teams so difficult orders are shared between them.(Business manager)

After several years of making clothes for big brands without much profit, VCo now considers diverting their client base to Chinese, Thailand and South Korean brands which offer reasonable rates while not being too strict on quality.

The union has also been active in advocating workers and lobbying the management to consider workers’ requests. The chairperson explained that some of the workers’ demands are legitimate and that management should respect workers’ wishes in order to maintain ‘peace’ in the factory. She refers to the union’s role as to balance the interests of workers and management. Clearly, the union is not representing workers in a Western style of collective bargaining. It relies on the expectation of a returned favour in the reciprocal relationship where workers have been mostly collaborative and supportive to the management in facing labour auditors. Hence, it would be expected that management return the favour by respecting some of their workers’ reasonable demands.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study of CoC implementation at the VCo factory has shown three important implications.

Firstly, from the empirical perspective, non-compliance and deception practices found at VCo are not unexpected. They are consistent with the conditions described in various studies of CoC implementation in supplier factories elsewhere in the global supply chain, e.g., [12,20,37,86,91]. Although the presence of CoC has helped in raising workers’ awareness of their rights and labour standards [34,89,92,93], the persistence of long working hours and violations of labour rights indicates the ineffectiveness of CoC in detecting and resolving such violations [7,8].

Secondly, the findings from this study challenge our existing understanding that workers are being coached by managers to lie to auditors because of a fear of being punished by the management [20,88,94,95]. Instead, practices found at VCo show, on the one hand, workers’ willingness to collaborate with managers to cheat on compliance and they were doing so with clear rationale and thought. On the other hand, workers are not hesitant to protest against the management if their demands are not sufficiently addressed and even when their workplace union does not fully represent workers. This two opposing sets of behaviours from VCo workers have strengthened our understanding of the struggle of labour standards in the global supply chain in recent decades.

On the one hand, the findings reinforce the view that suppliers at the bottom of the supply chain have little to gain from improving labour standards [88,96,97,98]. As long as there remains intricate supply networks with multiple layers of contractors and sub-contractors who are squeezed by Western buyers on price and time [99,100], there will be limited incentive for CoC compliance [23]. Findings from this study therefore complement the existing CoC literature which is dominated by case studies from suppliers who have direct relationships with Western brands [11,12,20,25,101,102].

On the other hand, this study offers a rich insight into why some non-compliance practices are difficult to detect and enforce [5,8,23]. As for when workers do not support CoC, it is harder for auditors and clients to detect suppliers’ misconduct. This finding highlights the agency aspect of workers and supports the view that workers are active economic agents who make conscious decisions within their constrained choices [49,52]. This understanding sheds a new light onto the conceptualisation of how workplace activism is shaped in the global supply chain context, which this paper will discuss next.

Finally, perhaps the most significant finding from this study is the revelation of the way in which workers use the reciprocal exchange principle as a bargaining tool in their employment relations. Western industrial relation literature often observes that several stages are necessary before collective action can materialise [58]:

- (1)

- the development of a collective sense of injustice, that something is “wrong” or “illegitimate” at the workplace (p. 27);

- (2)

- the identification of the employer as the cause of this injustice;

- (3)

- the recognition that collective action could rectify this injustice;

- (4)

- leaders who are willing and able to mobilise.

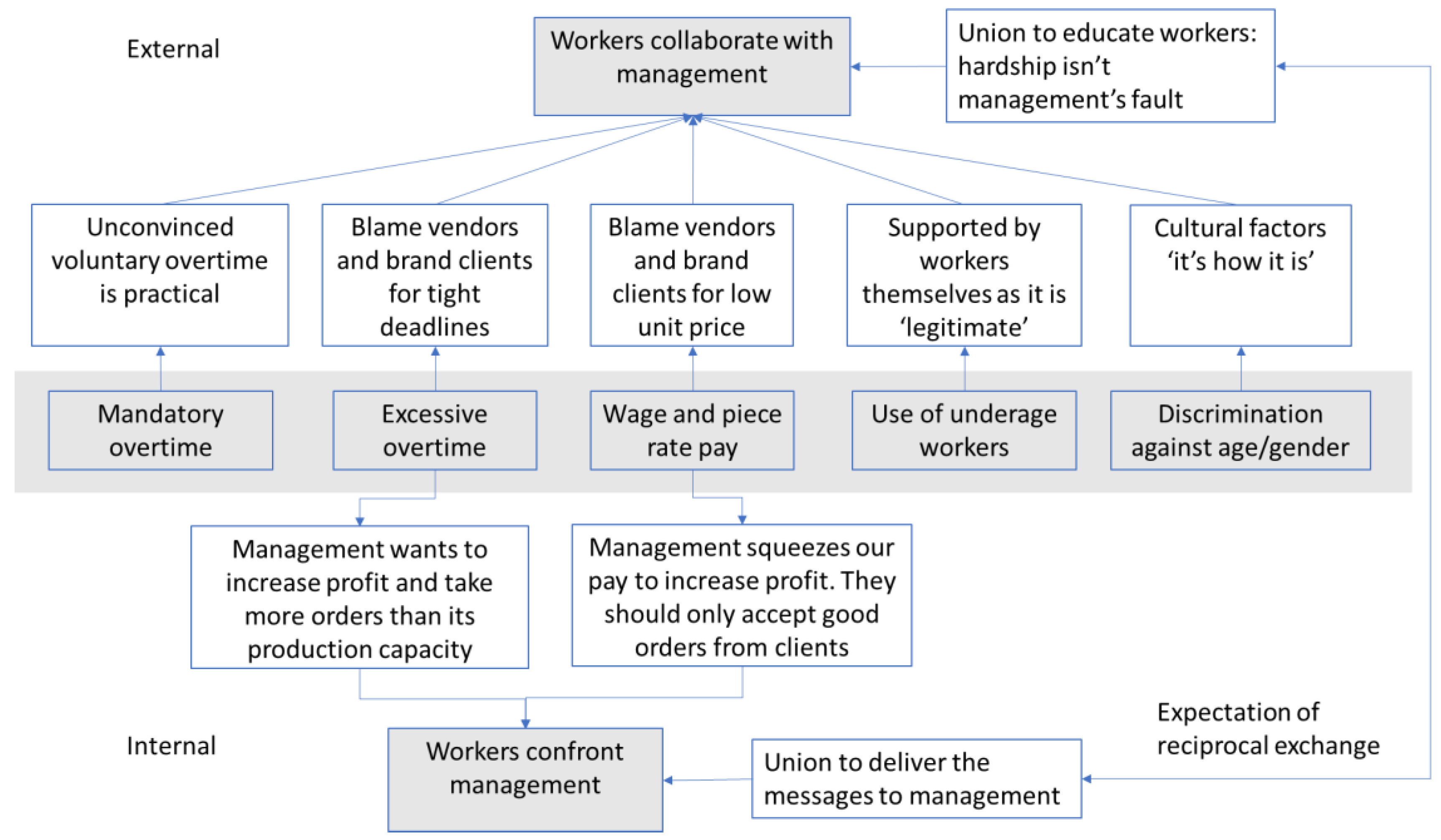

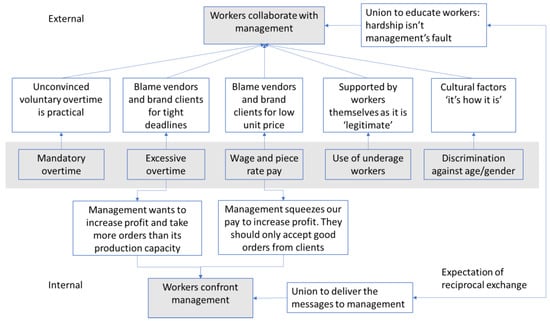

CoC studies which adopt this conceptual perspective could find it hard to see positive evidence of effective unionism and collective bargaining in the global supply chain [5,8,9,10]. Findings from this study suggest that there is a weak, if any at all, sense of injustice as outlined in the stage (1) above. VCo workers still embrace their social and cultural norms which view the use of underage workers and age discrimination as somewhat acceptable or ‘normal’. According to Lao Dong News [103], this problem is not only present at VCo but a widespread phenomenon across the country. However, workers at VCo, instead of demanding for their rights, have empathy towards the management-led union and, as the evidence shows, most workers are members of that union. Next, a notable finding from this study demonstrates that workers perceive the cause of their hardship (e.g., long work hours, low compensation) as the owners of CoC—Western brands and their East Asian contractors. Again, workers and their union share sympathy with the management for having to comply with labour standards, many of which are not necessary under their control.

However, workers recognise the power of collective action which can be mobilised to achieve their goals. Unfortunately, the institutional constraints (e.g., the union system inherited from state-owned enterprise and the restrictive freedom of association by the national labour law) limit workers’ ability to engage in a conventional bargaining method using direct negotiated exchange [55,61]. Evidence from VCo shows workers find their way to negotiate with employers through a reciprocal exchange [59,104], whereby they support management in hiding non-compliance practices and expect the management to return the favour by addressing their concerns regarding work hours and pay as illustrated in the Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Reciprocal exchange in VCo employment relation.

Reciprocal exchange, especially in a unilateral form such as the case of VCo workers, has an inherent risk that workers may not get what they want from the management despite the fact that they have supported them in deceiving CoC compliance. It is worth noting that this is in no way an ideal form of sustainable collective bargaining or an advocation of deception and violation of labour standards, but a recognition that given the disadvantageous position in the global supply chain and weak institutional support for formal unionism, reciprocity is found to be an alternative to confrontation as many suggest that reciprocity reinforces trust and solidarity to achieve common good [55,60].

In conclusion, this paper makes a significant empirical contribution to the existing literature by focusing on CoC practices from the workers’ perspective and paying particular attention to workers participation, their choices and actions. By adopting the agency’s perspective of analysis, this paper contributes to shed light on different aspects of CoC practices at factory levels. The empirical findings highlight the importance of workers as active agents who are adapted to the constraint choice imposed on them from the buyer-driven global clothing supply chain [105,106]. These findings reinforce the idea that negotiations between workers and companies are not exclusively influenced from above by the institutional legacy inherited from the communist unionism [107] or the macro-structural factors of the Western-inspired union that many suppliers have tried to implement [12]. On the contrary, findings from this study reflect the concrete strategies and choices adopted by the different actors5.

7. Limitation and Future Research

This paper draws from a single case study to present a new perspective in understanding the struggle of workplace unionism and the way in which workers circumvent the situation. Although this study has its strength of gathering rich and contextual data which may not be possible to acquire through other methods, this study is not without its limitation.

Firstly, findings from this case study are by no means a representation of working conditions and the labour movement in Vietnam, let alone the global supply chain. It, however, offers a new perspective to future research. Secondly, the characteristics of VCo as a formally a state-owned enterprise also limits the generalisation of findings to other types of suppliers such as newly established private-owned or Foreign Direct Investment, where working conditions and workers’ activism have been found to be distinctly different [23,71,72,108,109]. Nevertheless, given that more than two-thirds of the garment companies in Vietnam were formerly state-owned enterprises and share similar structures as VCo, findings from this case could shed light to future studies which could replicate the study design to multiple cases or use the survey method to provide a more generalised and comprehensive picture of the nature of CoC implementation in Vietnam.

Conceptually, this paper provides an alternative way of examining the nature of collective bargaining, reciprocal and unilateral vs. negotiated and bilateral arrangements, within the global supply chain context and would welcome further research in this direction. For example, future research could focus on identifying a mechanism which enables implicit negotiations and compromises between management and workers, or whether any improvements in working conditions in non-strike factories are a result of mutual trust and empathy in the organisation or due to workers’ inability to organise as claimed by previous research [5,107].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Coding list of interviewed workers.

Table A1.

Coding list of interviewed workers.

| No. | Code | Job Role | Age | Marital Status | Years of Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SW1 | sewing worker | 25 | married, 1 child | 5 |

| 2 | TL2 | sewing worker (team leader) | 23 | single | 5 |

| 3 | SW3 | sewing worker | 24 | single | 5 |

| 4 | SW4 | sewing worker | 23 | single | 4 |

| 5 | SW5 | sewing worker | 21 | single | 2 |

| 6 | SW6 | sewing worker | 23 | married | 3 |

| 7 | SW7 | sewing worker | 24 | married | 5 |

| 8 | SW8 | sewing worker | 25 | married, 1 child | 5 |

| 9 | SW9 | sewing worker | 17 | single | 0.5 |

| 10 | SW10 | sewing worker | 30 | single | 2 |

| 11 | SW11 | sewing worker | 27 | married, 1 child | 7 |

| 12 | SW12 | sewing worker | 22 | single | 1 |

| 13 | CW13 | cutting inspection worker | 19 | single | 1 |

| 14 | SW14 | sewing worker | 21 | single | 3 |

| 15 | SW15 | sewing worker | 20 | single | 2 |

| 16 | SW16 | sewing worker | 22 | single | 3 |

| 17 | SW17 | sewing worker | n/a | single | 3 |

| 18 | SW18 | sewing worker | 40 | married, 2 children | 8 |

| 19 | SW19 | sewing worker | 28 | married, 2 children | 6 |

| 20 | SW20 | sewing worker | 28 | single | 7 |

| 21 | SW21 | sewing worker | 23 | single | 3 |

| 22 | SW22 | sewing worker | 20 | single | 2 |

| 23 | SW23 | sewing worker | 21 | n/a | 2 |

| 24 | SW24 | sewing worker | 25 | married, 1 child | 8 |

| 25 | SW25 | sewing worker | 30 | married, 2 children | 11 |

| 26 | SW26 | sewing worker | 27 | married, 1 child | 10 |

| 27 | SW27 | sewing worker | 27 | married, 1 child | 10 |

| 28 | SW28 | sewing worker | 28 | married, 1 child | 11 |

| 29 | SW29 | sewing worker | 34 | married, 2 children | 16 |

| 30 | TL30 | sewing worker (team leader) | 38 | married, 2 children | 20 |

| 31 | SW31 | sewing worker | 25 | single | 4 |

| 32 | SW32 | sewing worker | 26 | single | 1 |

| 33 | SW33 | sewing worker | 28 | single | 8 |

| 34 | SK34 | store keeper and product safety inspector | 30 | married, 2 children | 10 |

| 35 | TL35 | sewing worker (team leader) | 41 | married, 2 children | 22 |

| 36 | SW36 | sewing worker | n/a | married, 1 child | 5 |

| 37 | SW37 | sewing worker | 21 | single | 3 |

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Distribution of Age of workers.

Figure A1.

Distribution of Age of workers.

Appendix C

Figure A2.

Distribution of Year of employment at VCo.

Figure A2.

Distribution of Year of employment at VCo.

References

- Yanz, L.; Jeffcott, B.; Ladd, D.; Atlin, J. Policy Options to Improve Standards for Women Garment Workers in Canada and Internaionally; Maquila Solidarity Network: Toronto, ON, Canada, January 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.R.; Husain, S. Invisible Hands—The Women Behind India’s Export Earnings. In Indian Women in a Changing Industrial Scenario; Banerjee, N., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1991; pp. 133–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hilowitz, J. Social labelling to combat child labour: Some considerations. Int. Labour Rev. 1997, 136, 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Liubicic, R.J. Corporate codes of conduct and product labelling schemes: The limits and possibilities of promoting international labour rights through private initiatives. Law Policy Int. Bus. 1998, 30, 111–158. [Google Scholar]

- Louche, C.; Staelens, L.; D’Haese, M. When Workplace Unionism in Global Value Chains Does Not Function Well: Exploring the Impediments. J. Bus. Ethics 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, E.; Groutsis, D.; van den Broek, D.; Rimmer, M. Migration Intermediaries and Codes of Conduct: Temporary Migrant Workers in Australian Horticulture. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels-Zandén, N. Responsibility Boundaries in Global Value Chains: Supplier Audit Prioritizations and Moral Disengagement Among Swedish Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels-Zandén, N.; Lindholm, H. Do codes of conduct improve worker rights in supply chains? A study of Fair Wear Foundation. J. Clean Prod. 2015, 107, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. From passive beneficiary to active stakeholder: Workers’ participation in CSR movement against labor abuses. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87 (Suppl. 1), 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S. Globalization, athletic footwear commodity chains and employment relations in China. Organ. Stud. 2001, 22, 531–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S.J.; Scott, D. Compliance, collaboration, and codes of labor practice: The adidas connection. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 45, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Impacts of corporate code of conduct on labor standards: A case study of Reebok’s athletic footwear supplier factory in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C. A Review of UK Company Codes of Conduct; Department for International Development, Social Development Division: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, P.S. Codes of Conduct for Multinational Corporations: An Idea Whose Time Has Come. Bus. Soc. Review 1999, 104, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.; Seyfang, G. New Hope or False Down? Voluntary Codes of Conduct, Labour Regulation and Social Policy in a Globalising World. Global Soc. Policy 2001, 1, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R. Corporate Codes of Conduct Self-Regulation in a Global Economy; UNRISD: Geneva, Switzerland, April 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Carron, M.; Lund-Thomsen, P.; Chan, A.K.K.; Muro, A.; Bhushan, C. Critical perspectives on CSR and development: What we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to know. Int. Aff. 2006, 82, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garavito, C.A. Global governance and Labor rights: Codes of conduct and anti- sweatshop struggles in global apparel factories in Mexico and Guatemala. Politics Soc. 2005, 33, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.; Romis, M. Improving work conditions in a global supply chain. mit Sloan Manag. Rev. 2007, 48, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Egels-Zanden, N. Suppliers’ compliance with MNCs’ codes of conduct: Behind the scenes at Chinese toy suppliers. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Engardio, P.; Bernstein, A. Secrets, Lies, and Sweatshops. BusinessWeek, 27 November 2006; 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty, J. The Price Of A Cheap Suit. CFO 2005, 21, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, D.; Jones, B. Why do corporate codes of conduct fail? Women workers and clothing supply chains in Vietnam. Global Social Policy 2012, 12, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.E.; Spekman, R.E.; Kamauff, J.W.; Werhane, P. Corporate social responsibility in global supply chains: A procedural justice perspective. Long Range Plan. 2007, 40, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.M.; Qin, F.; Brause, A. Does monitoring improve labor standards? Lessons from Nike. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 2007, 61, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B. Implementing Supplier Codes of Conduct in Global Supply Chains: Process Explanations from Theoretic and Empirical Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insight Investment. Building Your Way into Trouble: The Challenge of Supply Chain Management; Insight Investment Limited and Acona: London, UK, 23 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, E.R.; Andersen, M. Safeguarding corporate social responsibility (CSR) in global supply chains: How codes of conduct are managed in buyer-supplier relationships. J. Public Aff. 2006, 6, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.; Kochan, T.; Romis, M.; Qin, F. Beyond corporate codes of conduct: Work organization and labour standards at Nike’s suppliers. Int. Labour Rev. 2007, 146, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.V.A. Worker empowerment through private standards: Evidence from the Peruvian horticultural export sector/Monica Schuster. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 53, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said-Allsopp, M.; Tallontire, A. Pathways to empowerment?: Dynamics of women’s participation in Global Value Chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, D. Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster-Sandoval, R. Workers of the World Unite? The Contemporary Anti-Sweatshop Movement and the Struggle for Social Justice in the Americas. Work Occup. 2005, 32, 464–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D. The Market for Virtue: The Potential and Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K.; Coryndon, A. Trading Away Our Rights: Women Working in Global Supply Chains; Oxfarm International: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P. Low wage costs attract investors to Vietnam. In BBC Asia Business Report, 18 June 2010 ed.; BBC: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, R.; Amengual, M.; Mangla, A. Virtue out of Necessity? Compliance, Commitment, and the Improvement of Labor Conditions in Global Supply Chains. Politics Soc. 2009, 37, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, H.B.; Pruzan-Jørgensen, P.M.; Jungk, M.; Cramer, A. Strengthening Implementation of Corporate Social Responsibility in Global Supply Chains; The World Bank Group & The International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. The Power to Choose: Bangladeshi Women and Labour Market Decisions in London and Dhaka; Verso Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, C.; Bek, D. (Re)politicizing empowerment: Lessons from the South African wine industry. Geoforum 2006, 37, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rowlands, J. Questioning Empowerment; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, J.; Siim, B. Introduction: The politics of inclusion and empowerment: Gender, class and citizenship. In The Politics of Inclusion and Empowerment: Gender, Class and Citizenship; Andersen, J., Siim, B., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure, and Contradiction in Social Analysis; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979; Volume 241. [Google Scholar]

- Cumbers, A.; Helms, G.; Swanson, K. Class, Agency and Resistance in the Old Industrial City. Antipode 2010, 42, 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A. The culture of survival: Lives of migrant workers through the prism of private letters. In Popular China; Link, P., Madsen, R., Pickowicz, P., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Boulder, CO, USA, 2002; pp. 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.K. Gender and the South China Miracle: Two Worlds of Factory Women; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, F.E. The Rise of the Bangladesh Garment Industry: Globalization, Women Workers, and Voice. Natl. Women’s Stud. Assoc. (NWSA) J. 2004, 16, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, P. Made in China: Women Factory Workers in a Global Workplace; Duke University Press: Durham, UK; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Jacobs, F. Poor But Not Powerless: Women Workers in Production Chain Factories in China. J. Adolesc. Res. 2010, 25, 807–838. [Google Scholar]

- Riisgaard, L.; Okinda, O. Changing labour power on smallholder tea farms in Kenya. Competition Chang. 2018, 22, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbers, A.; Nativel, C.; Routledge, P. Labour agency and union positionalities in global production networks. J. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 8, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P. Labor agency in the football manufacturing industry of Sialkot, Pakistan. Geoforum 2013, 44, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. Tripartite consultation in China: A first step towards collective bargaining? Int. Labour Rev. 2008, 147, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincher, R.D. Workplace Dispute Resolution in Vietnam: Perspectives on a Developing Nation. Disput. Resolut. J. 2011, 66, 11–63. [Google Scholar]

- Molm, L.D. The Structure of Reciprocity. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2010, 73, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.S.; Emerson, R.M.; Gillmore, M.R.; Yamagishi, T. The distribution of power in exchange networks: Theory and experimental results. Am. J. Sociol. 1983, 89, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovsky, B.; Willer, D.; Patton, T. Power relations in exchange networks. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1988, 53, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. Rethinking Industrial Relations: Mobilisation, Collectivism and Long Waves; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Molm, L.D.; Collett, J.L.; Schaefer, D.R. Building solidarity through generalized exchange: A theory of reciprocity. Am. J. Sociol. 2007, 113, 205–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A.; Fischbacher, U. A theory of reciprocity. Games Econ. Behav. 2006, 54, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, S.V.; Sommer, Z.L. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Reciprocity, Negotiation, and the Choice of Structurally Disadvantaged Actors to Remain in Networks. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2016, 79, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, B.; De Witte, H. Job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Testing psychological contract breach versus distributive injustice as indicators of lack of reciprocity. Work Stress 2015, 29, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowgill, M.; Luebker, M.; Xia, C. Minimum Wages in the Global Garment Industry: Update for 2015; ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. World Trade Statistical Review 2018; World Trade Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, T.T.D. Textile and Apparel Industry Report 2018; Phu Hung Securities, Vietnam Stockexchange: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 20 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.T. Textile and Apparel Industry Report 2017; FPT Securities, Vietnam stockexchange: Hà Nội, Vietnam, December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, V.T. Textile and Apparel Industry Report 2014; FPT Securities, Vietnam stockexchange: Hà Nội, Vietnam, April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thoburn, J. Vietnam and the End of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement: A Preliminary View. J. Int. Coop. Stud. 2007, 15, 93–107. [Google Scholar]