1. Introduction

Citizenship has come to the fore as a key concept in British politics over the past three decades. Since the late 1980s, United Kingdom (UK) governments have sought to develop initiatives designed to promote forms of “active citizenship”. Young people, in particular, have been a clear focus of policy, encouraged to be “good citizens” by engaging in activities such as volunteering, especially in the local community. An important concern of politicians and others is that if young people do not feel like stakeholders in their communities, their sense of citizenship may go “missing” [

1]. The increasing prevalence of discourses of citizenship among politicians, academics, campaigners, and commentators has coincided with a significant shift at a governmental policy level towards a responsibilisation of citizenship [

2], with successive governments arguing for the need for citizens to take increasing personal responsibility for their own individual educational, health, and welfare needs, and for a significantly greater role to be played by the community (or communities) rather than the state in addressing various social problems. Such voluntary and community service is viewed as a crucial means of enhancing social cohesion. As regards young people, the focus on the inculcation of the responsibilities of citizenship has also extended to forms of political participation such as voting and engaging in party politics [

3].

This emphasis can be seen across a range of policies, from the then Conservative Home Secretary Douglas Hurd’s “active citizenship” initiative and its concern with the “diffusion of power”, “civic obligation”, and “voluntary service” [

4] (p. 14); to Labour’s compulsory introduction of citizenship lessons in secondary schools in England in 2002 and its clear stress on volunteering [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]; to the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government’s “Big Society” initiative [

10] and the accompanying National Citizen Service [

11,

12] (which continues to be promoted by the current single party, minority Conservative government), in which young people are encouraged to undertake a variety of community projects. Young people are often seen by policymakers and scholars as citizens of the future, or “citizens in the making”, as the sociologist T.H. Marshall put it in his influential 1950 essay outlining a tripartite schema of civil, political, and social rights,

Citizenship and Social Class [

13] (p. 25). This categorization of young people as “not-yet-citizens” is problematic from the point of view of them “being treated with equality in terms of membership in society”, with young people “positioned as the passive recipients of citizenship policy rather than as active citizens in their own right” [

14] (p. 642). In our view, an inclusive conception of citizenship demands that the perspectives of young people themselves must be heard.

Moreover, despite the great interest in citizenship shown by different governments, the concept has historically been a rather unfamiliar one in the British context, with individuals often having been viewed by constitutional experts not as citizens, but instead as “subjects” of the crown. In the contemporary literature, citizenship is frequently defined in terms of an individual’s membership of a state or of a political community of some kind and their legal and moral rights against, and duties towards, the state and indeed other citizens [

15] (p. xix) [

16] (p. 166]. Citizenship is widely viewed as an “essentially contested concept” [

17] (p. 10) [

18] (p. 3) [

7] (p. 39) [

19] (p. 3) [

20] (p. 82). It may be seen as “a multi-layered construct” [

21] (p. 117) [

22], and indeed some postmodern thinkers have been concerned with deconstructing citizenship, examining the signs and symbols that they argue give the concept meaning [

23]. Certainly, citizenship “is not an eternal essence but a cultural artefact. It is what people make of it” [

24] (p. 11) and it has “multiple meanings” [

24] (p. 13), giving rise to a variety of different perspectives. For Isin and Turner, citizenship ought to be conceptualized in a contemporary context more widely than just a narrow focus on legal rights, but rather as a dynamic, active practice, a struggle for rights at particular times in specific circumstances, “a social process through which individuals and social groups engage in claiming, expanding or losing rights”, which leads “to a sociologically informed definition of citizenship in which the emphasis is less on legal rules and more on norms, practices, meanings and identities” [

25] (p. 4).

Researchers in the discipline of social psychology have the potential to contribute significantly to such a conceptualisation, particularly given their pioneering work developing concepts such as social identity, prosocial behaviour, interpersonal citizenship behaviour, and organizational citizenship. Indeed, the preoccupations of citizenship scholars can also be seen to relate quite closely to the interests of social and community psychologists who seek to understand the individual-group-society nexus [

26], and whose research includes work on, for example, “group cohesion, intergroup conflict, prejudice and discrimination, quality of life, social justice and legitimacy, [and] self-regulation” [

27] (p. 196). However, as Stevenson et al. pointed out in their introduction to a recent special thematic section in a social psychology journal on “The Social Psychology of Citizenship, Participation and Social Exclusion”, despite the “explosion of research on the topic of citizenship across the social sciences” over the past few decades, only “a ripple” has “passed through the discipline of social psychology” [

28] (p. 1). They went on to conclude in their accompanying paper to sum up the special edition that: “Our review of a range of psychological approaches to citizenship…is best characterised by the study of the constructive, active and collective (but often exclusive) understandings of citizenship in people’s everyday lives” [

29] (p. 203) [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. In this vein, our aim is to further develop an understanding of citizenship by exploring these understandings of citizenship in people’s everyday lives, as constructed by the citizens themselves.

In our view, those psychologists who have addressed the concept are right to argue that citizenship ought to be viewed both as a political concept and also a psychosocial concept, one that can be explored through an analysis of an individual’s sense of self and his or her place in a community or society [

43]. In order to develop such a psychological understanding, it is essential to gain significant purchase on what citizenship means to citizens themselves and, in particular, to develop a ground-up understanding of citizens’ views that moves the analysis beyond a discussion of the two core traditions of liberal and republican citizenship that often dominate work in this area, with the former emphasizing citizens’ rights and the latter their civic duties [

44] (p. 254), but which are of only limited use in understanding citizens’ actual constructions of citizenship, which may not fit neatly with these ideal-type theoretical perspectives [

40,

42].

This article is concerned with uncovering the varied perspectives on citizenship of teenagers in England today [

45] (p. 2). Utilising a Q-methodology approach to analysing subjectivities or, more precisely, intersubjectivities, we investigated the different ways in which young people understand citizenship and construct their own identities as citizens. Whereas top-down approaches reify citizenship by abstracting from citizens’ real, lived experiences, the approach adopted here is significant because it offers a ground-up perspective on understanding young people’s different constructions of citizenship, based on their own particular experiences and meanings.

2. Method

2.1. Utilising Q-Methodology

Q-methodology was designed to study the different subjective viewpoints across a group on a particular issue [

46]. Q-methodology is both a quantitative and qualitative approach [

47,

48]. The research participants (

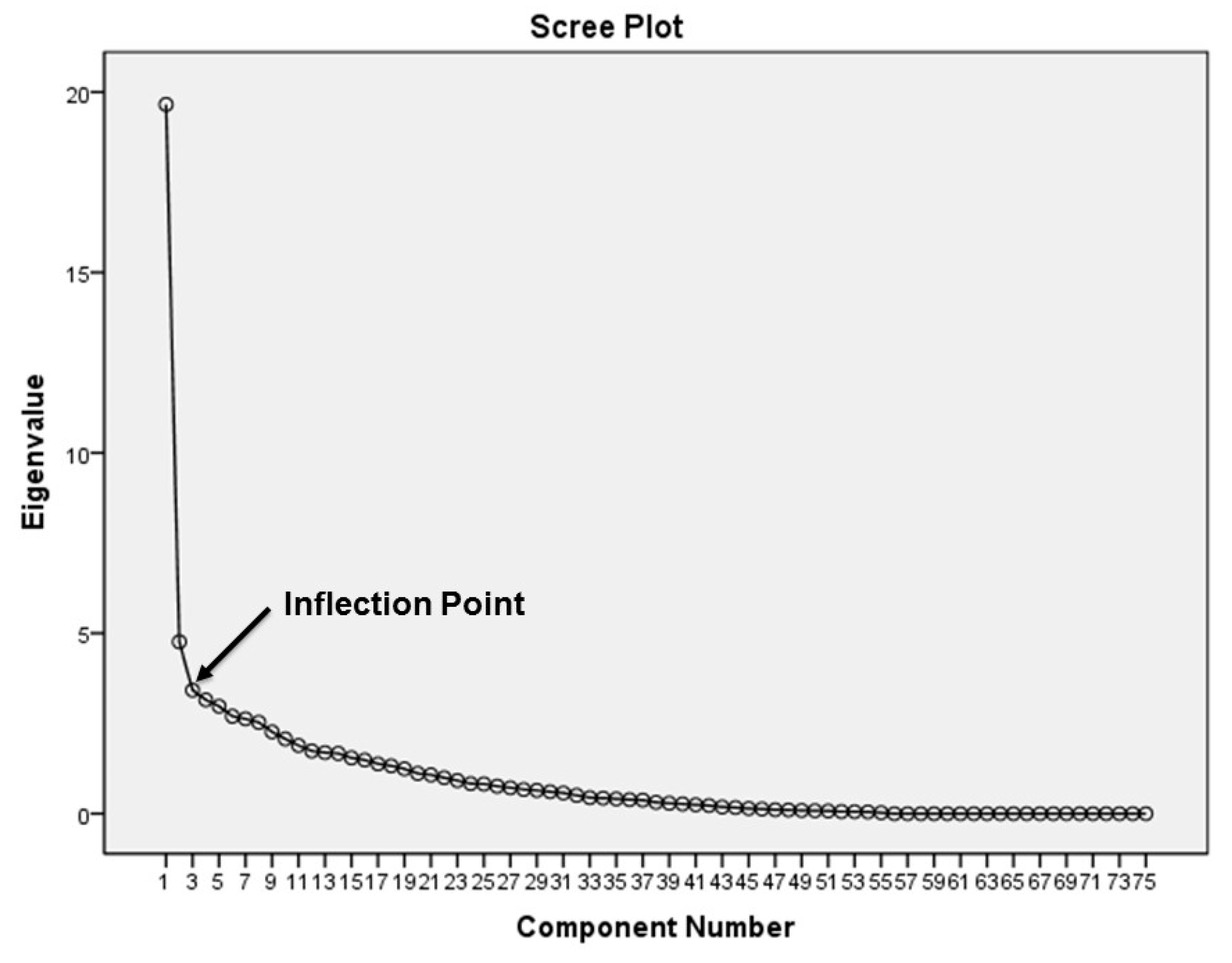

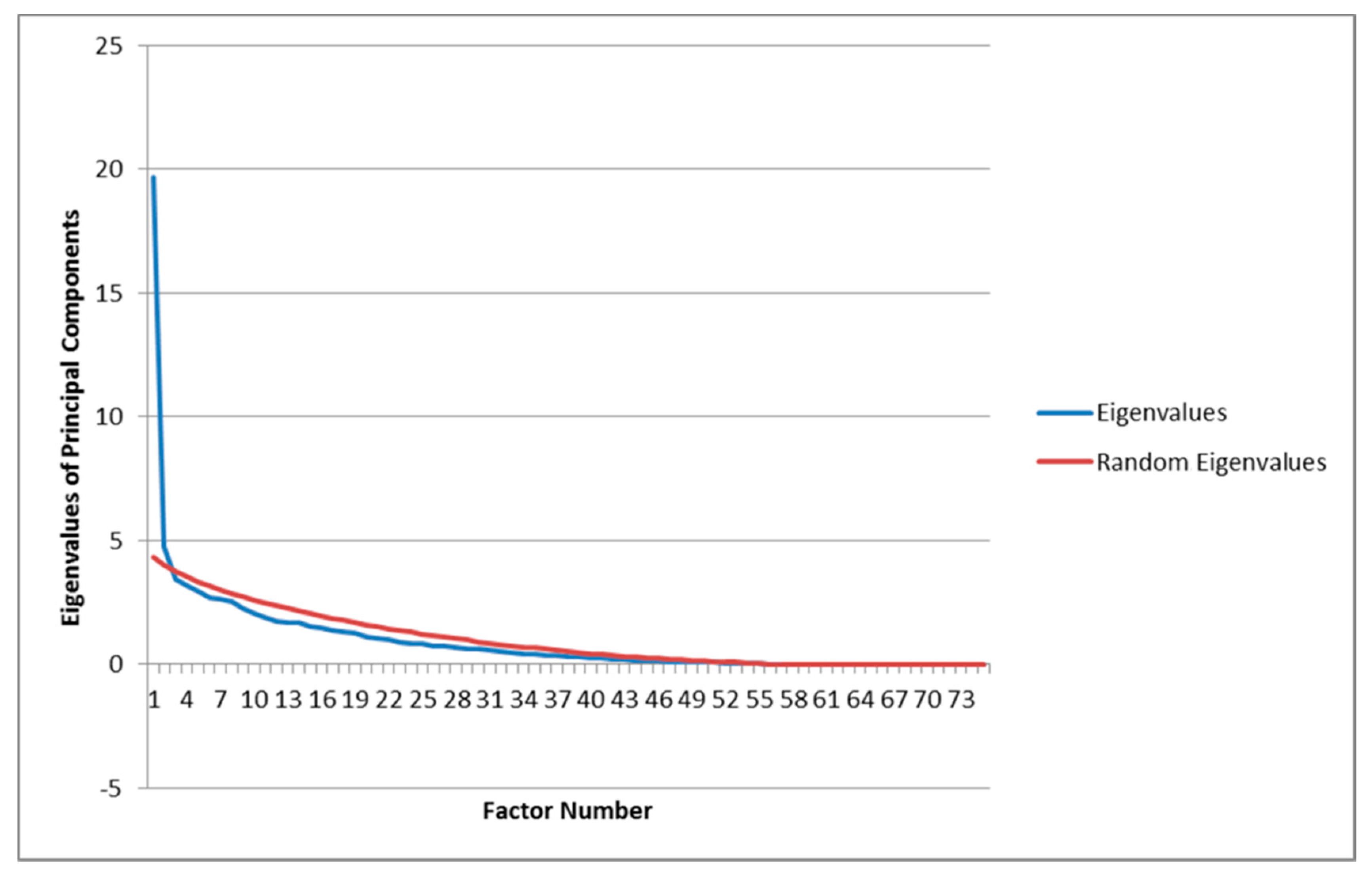

P-set) articulated their understanding of citizenship in Britain by “sorting” items (Q-items). This sorting required participants to rank-order the Q-items (56 statements on a scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”), thus enabling participants to impose meaning and significance onto them [

49] (p. 209). These sorted items were then examined using the quantitative method of factor analysis, which allocated individuals with similar sorting patterns into the same group, thereby identifying the major perspectives on the topic. The qualitative aspect of Q-methodology involved examining how groups of participants organized the Q-item-sample statements and how different individuals’ particular perspectives clustered around the different discourses identified [

50] (pp. 98–117) [

49] (p. 210).

2.2. Participants

Q-methodology does not require demographic representativeness because it is not aiming at making demographic generalisations. Participants were recruited utilising the researchers’ networks and snowballing. The P-set comprised 85 participants of whom 75 completed the task fully (male = 41, female = 34; age M = 17.25 years, SD = 1.41; the 10 other participants’ Q-sorts were excluded from further analysis because of incomplete data). The P-set were recruited from a variety of educational providers and locations in England, targeted to incorporate different views from a diverse sample of members of the group of interest—young people. Twenty-two participants were from Lincolnshire, nine were from Greater Manchester, nine were from Yorkshire; eight were from County Durham, six were from London, five were from Nottinghamshire, five were from Somerset, three were from Bristol, and one was from each of the following: Tyne and Wear, Glamorgan, Oxfordshire, Warwickshire, the West Midlands, Norfolk, Hertfordshire, and Derbyshire. From the information provided, 62.7% (47) were in full-time education, 21.3% (16) were in education and part-time work, 2.7% (two) were unemployed, and 13.3% (ten) did not respond to this question. Their ethnicity was 70.7% (53) White (British, Irish, Other), 6.6% (five) Asian (Pakistani, Bangladeshi, or South Asian), 4.0% (three) Black (Caribbean, African), 8.0% (six) Mixed, 1.3% (one) Chinese or Other, and 9.3% (seven) did not respond. Sixty-two participants stated that they were British (including five who were not born in Britain). Two people said that they were not British, one of whom was born in Britain, and 11 did not state their nationality.

2.3. Materials

The

P-set were the “makers of the meaning” of the citizenship phenomenon under investigation, and it was ensured that “the flow of communicability surrounding any topic [in] the ordinary conversation, commentary, and discourse of everyday life” [

50] (p. 94) was available to them so that they could express themselves. This was achieved by assembling the “concourse” (this comes from the Latin “concursus” and means “a running together”) [

50] (p. 94), which included the ideas, expressions, opinions, and general “chatter” about the issue being investigated. From the initial concourse, a Q-sample was put together.

To ensure that the concourse collected the major themes of citizenship, a range of sources (e.g. academic literature, newspapers, magazines, television programmes, internet sites, and other media outlets) were examined. Since the aim of generating a concourse of statements was to gather as many ideas that could be expressed about citizenship as possible, the exclusion or inclusion criterion was whether the statements could be meaningfully and coherently related to citizenship. The initial concourse (>600 statements) was distilled into the Q-item-sample (

n = 56 statements) to form the materials for the study (see

Appendix A,

Table A1). Content and thematic analysis [

51] were used to ensure that the Q-item-sample statements were representative and comprehensive of the concourse [

50]. The content analysis entailed categorising each Q-item-sample statement by its perceived theme. Each Q-item statement was analysed to make sure it expressed only one recognizable assertion about the nature of citizenship, thereby ensuring that participants could express clearly and decisively their opinion about the statement. This content analysis procedure resulted in a number of categories being constructed. Each category was then analysed to reduce the population of Q-item statements into a manageable Q-item-sample, ensuring that all of the ideas contained in the category were represented. Replication was eliminated, as were Q-item statements that were not specifically focused on the social-personal aspects of being a citizen. An original sample of statements was then piloted on seven first-year undergraduates, chosen because they were still of a similar age to the target

P-set and for their ability to recommend appropriate modifications to the Q-item-sample statements. The pilot study ensured the clarity of the materials and that only one theme was being expressed in a statement. The statements were then typed onto individual cards protected by plastic shields and given a random identification number.

2.4. Procedure

Participants carried out the task in the presence of a responsible figure (their teacher, tutor, or primary carer) and one researcher (Criminal Records Bureau checked). Participants volunteered to take part and were told that the purpose of the research was to find out about young people’s views of being a citizen in Britain, and specifically they were asked to consider the task in terms of: “What does being a ‘citizen’ mean?” and “What does ‘citizenship’ mean to you?” The young people were told:

We are seeking your views about being a citizen in Britain. We are interested in your feelings about such things as your rights, privileges, obligations and duties as members of society. You will be given a number of cards with statements on them about being a citizen. Then you will be asked to sort out these statements according to how much you agree or disagree with them.

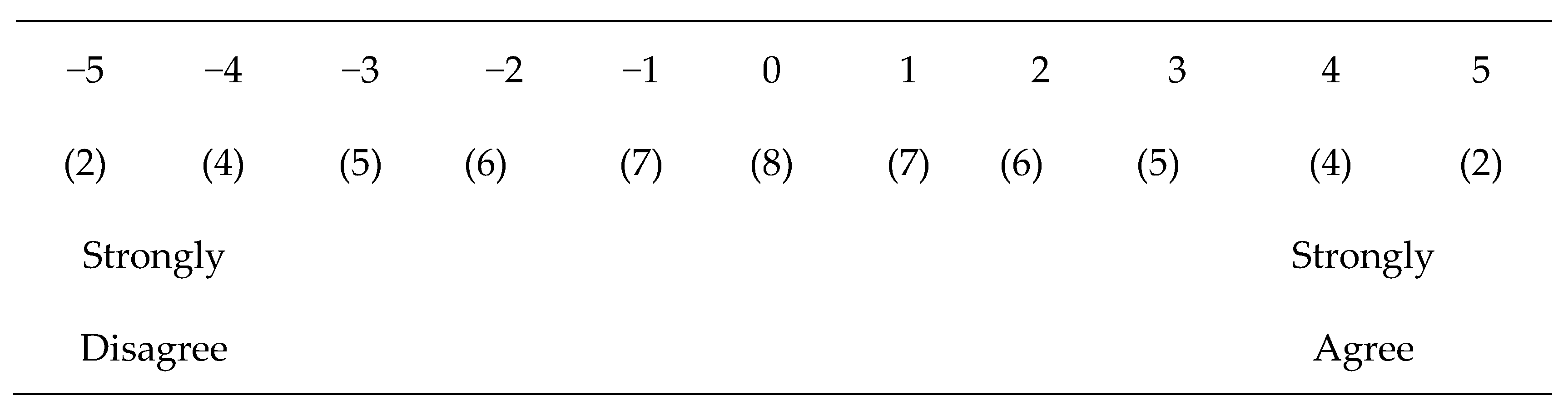

Participants ranked the set of 56 Q-item-sample statements on a fixed quasi-normal distribution that varied between −5 (“strongly disagree”) to +5 (“strongly agree”) (see

Figure 1). The ranking criterion was the extent to which they felt the statement described their view of being a citizen. Sorting of Q-item-sample statements was self-paced and performed individually by each participant. All 56 statements had to be used.

2.5. Ethics

A sample of young people in England were invited to take part in the research through an introductory letter that detailed the research activity and explained that the study had been approved by the School of Psychology’s ethics committee at the University of Lincoln. Participants were reminded of their right to withdraw from the study, but none did so. They were thanked and given a £15 voucher for their time and effort.

4. Discussion

This article has presented the findings of a Q-methodological study of how young people in England understand citizenship in Britain. In so doing, the article has demonstrated Q-methodology’s very clear strengths as an approach for analysing subjective viewpoints, applying this methodology to an important area it has rarely been used to examine before. Despite the plethora of UK government initiatives on citizenship, in particular, directed at young people, insufficient emphasis has been placed on ascertaining the perspectives of young people themselves. In rejecting an

a priori conceptualization of citizenship, this article set out the ways in which young people defined their identities as citizens. For Harré, one requirement for a science is that it should be concerned with “the identification, individuation and classification of the phenomena of the domain of interest” [

79] (p. 4). This research, utilising Q-methodology, conducted such an identification, individuation, and classification process, in which three factors comprising four stances emerged on what it means to be a citizen for the young people in our sample. The research suggests not only that simplistic, top-down approaches advanced by governments (and others) may make it hard for them to relate to young people, but also that understanding the multiple ways in which young people construct citizenship may make possible a more consequential and effective engagement with them that is attuned to their particular experiences and meanings. Such understanding and engagement is essential as a means of ensuring that young people are able to make an impact on, rather than simply being at the receiving end of, the development of citizenship policy in Britain.

4.1. Future Work

An interesting finding of this study was that the different positions described above drew on different aspects of liberal, republican, and communitarian normative theories of citizenship but did not fit neatly with these ideal-type theoretical perspectives. They also drew on considerations not necessarily captured by these three theories. In our view, this is an important point that needs to be borne in mind when designing policy that seeks to promote particular attitudes and behaviour among young people, for example through citizenship classes in schools.

One way forward might be to develop a position-preference type questionnaire that connects the stances outlined to both personal and social factors so as to enable an analysis of the conditions under which different understandings of citizenship are invoked or are possible. Such a questionnaire could be very usefully deployed in citizenship lessons, enabling young people to gain a fuller appreciation of themselves as citizens and aiding the facilitation of the development of the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes they need to engage in civic and political activity so as to address important issues of concern to them. Such an idea is in many respects similar to that employed in the positive psychology approach of Park, Peterson, and Seligman, who initially identified 24 different character strengths and then sought to devise strategies to help people recognise and develop their strengths further [

80].

4.2. Limitations

The use of Q-methodology does not lead to the production of statistically generalizable results across populations, but rather the positions uncovered are themselves generalisations about the universe of discourse [

81] (p. 534). We do not claim that the factors and stances identified are exhaustive of all the possibilities of young people’s understandings of citizenship. Nor do the findings provide general demographic information in relation to young people’s citizen identities. Future work is needed to further understand these stances in relation to particular contexts. The stances could be investigated in terms of, for example, the impact of gender, class, sexuality, and ethnicity, so as to take the essentially contested concept of citizenship and place that abstraction, now given some descriptive form, in a context.