Rural Villagers’ Quality of Life Improvement by Economic Self-Reliance Practices and Trust in the Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Context

2.1. The Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy and Moderation Concepts

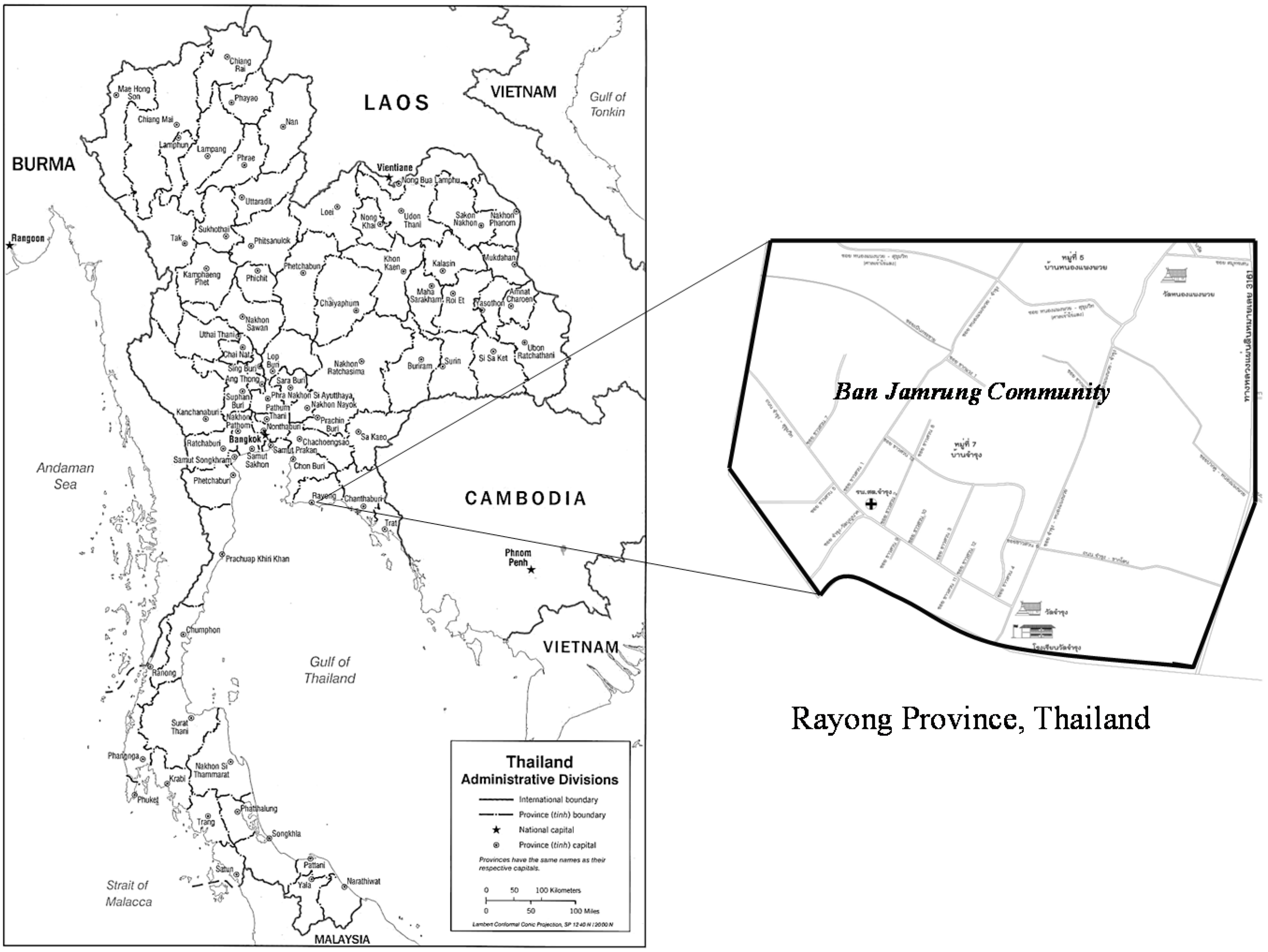

2.2. Practices of Sufficiency Economy in Ban Jamrung Community, Rayong Province, Thailand

2.3. Trust Concepts

2.4. Factors Contributing to Community Trust

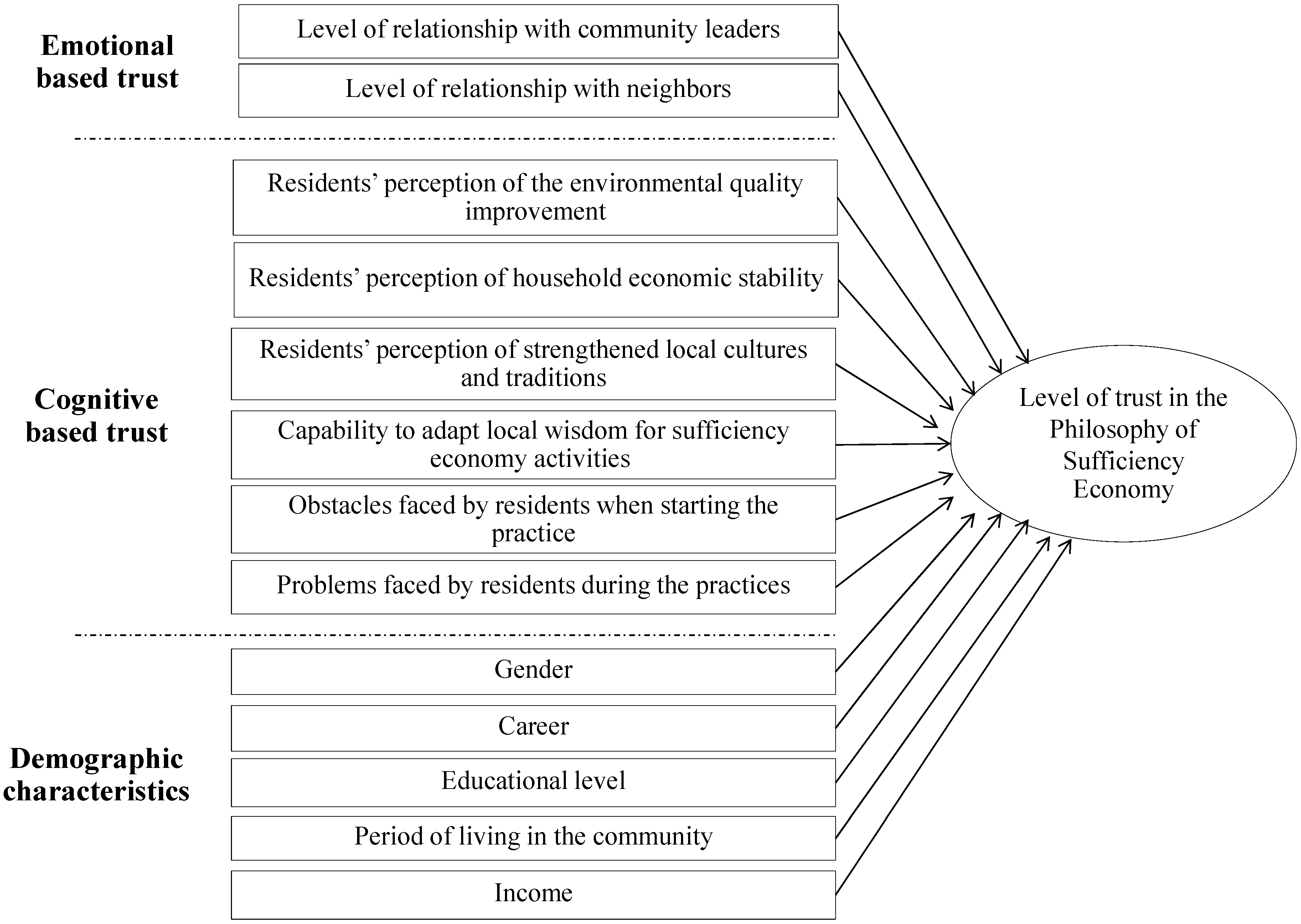

3. Study Framework

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Development of Variables and Measurement

4.2. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Findings and Discussions

5.1. Characteristics of Respondents and the Practices of Sufficiency Economy Philosophy in Ban Jamrung Community

5.2. Contribution of Sufficiency Economy Practices to Sustainability in a Rural Community

5.3. Determinants of Trust towards the Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy

5.4. Implications for Development of Strategies to Maintain and Enhance Trust of People in the Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siltragool, W. Thailand. In Enhancing Income Generation through Adult Education: A Comparative Study; Bagnall, R.G., Ed.; The Asian-South Pacific Bureau of Adult Education: Brisbane, Australia, 2003; pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wongchaum, S. Sufficiency Economy: Basis to the Sustainable Development; Office of National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB): Bangkok, Thailand, 2001.

- Chumpol, W. Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy. In Proceedings of the National Geographic Conference, Chiangmai, Thailand, 12 July 2008.

- Mongsawad, P. The Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy and economic administration. In Proceedings of the 3rd National Conference of Economist Association, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand, 26 October 2007.

- Godfrey, P.C. What is economic self-reliance? ESR Rev. 2008, 10, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnanand, S. The Philosophy of Life. 1992. Available online: http://www.swami-krishnananda.org/phil/Philosophy_of_Life.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2016).

- Office of the Permanent Secretary for Public Health, Ministry of Public Health. 2010. Available online: http://service.nso.go.th/nso/nsopublish/BaseStat/basestat.html (accessed on 22 March 2016).

- Norse, D.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; Zhang, Z. Environmental Costs of Rice Production in China: Lessons from Hunan and Hubei; Aileen International Press: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Norse, D. Non-Point pollution from crop production: Global, regional and national issues. Pedosphere 2005, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.J.; Duan, L.; Mo, J.; Du, E.; Shen, J.; Lu, X. Nitrogen deposition and its ecological impact in China: An overview. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2251–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Ryan, J. Managing Fertilizers to Enhance Soil Health; IFA: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, T.C.; Siegrist, M.; Gutscher, H. Trust, risk perception and the TCC model of cooperation. In Trust in Risk Management, 1st ed.; Siegrist, M., Earle, T.C., Gutscher, H., Eds.; Earthscan: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter, J.B. Interpersonal trust, trustworthiness, and gullibility. Am. Psychol. 1980, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.L. Building trust. Centre for Economic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. Available online: http://web.mit.edu/polisci/research/locke/building_trust.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2016).

- Piboolsravut, P. Sufficiency Economy and a healthy community. In Proceedings of the 3rd IUCN World Conservation Congress, Bangkok, Thailand, 17–25 November 2004.

- Panthasein, A. H.M. the King’s Sufficiency Economy, Analyzed by Economist’s Definitions; Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI): Bangkok, Thailand, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mongsawad, P. Sufficiency Economy: A contribution to economic development. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2008, 2, 474–481. [Google Scholar]

- Mongsawad, P. The Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy: A contribution to the theory of development. Asia-Pacific Dev. J. 2010, 17, 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, F.; Adnan, A. HAMKA’s concept of moderation an analysis. J. Islam Asia 2011, 21, 357–375. [Google Scholar]

- Khunthongjan, S.; Onsibutra, W. Strengthening Thai social value with the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy. Silpakorn Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Arts 2014, 14, 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Chalapati, S. Sufficiency economy as a response to the problem of poverty in Thailand. Asian Soc. Sci. 2008, 4, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruetipibultham, O. The Sufficiency Economy Philosophy and strategic HRD: A sustainable development for Thailand. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2010, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naipinit, A.; Promsaka Na Sakolnakorn, T.; Kroeksakul, P. Sufficiency Economy for social and environmental sustainability: A case study of four villages in rural Thailand. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukamchanoad, P. Guideline for happy living according to Sufficiency Economy Philosophy of people and community leaders in urban communities. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2014, 8, 1921–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Yanbo, W.; Qingfei, M.; Shengnan, H. Understanding the effects of trust and risk on individual behavior toward social media platforms: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Akamavi, R.K.; Mohamed, E.; Pellmann, K.; Xu, Y. Key determinants of passenger loyalty in the low-cost airline business. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 528–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P. Building trust and value in health systems in low- and middle- income countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1430–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher, J.W.; Stephen, G.S. Engaging the public in climate change-related pro-environmental behaviors to protect coral reefs: The role of public trust in the management agency. Mar. Policy 2015, 53, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Huhe, N.; Chen, J.; Tang, M. Social trust and grassroots governance in rural China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 53, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. J. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar]

- Elofson, G. Developing trust within intelligent agents: An explanatory study. In Trust and Deception in Virtual Societies, 1st ed.; Castelfranchi, C., Tan, Y.H., Eds.; Springer: Dordecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q. Trust, Social Capital, and Organizational Effectiveness; Research Report; Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic, Institute and State University: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, A.; Hailes, S. Supportingtrust in virtual community. In Proceedings of the 33rd Hawaii International Conferences on System Science, Hawaii, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2000.

- Strulik, T. Rating agencies, ignorance and the knowledge-based production of system trust. In Towards a Cognitive Mode in Global Finance: The Governance of a Knowledge-Based Financial System, 1st ed.; Strulik, T., Willke, H., Eds.; Campus, Frankfurt am Main: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- Andriani, L.; Sabatini, F. Trust and prosocial behaviour in a process of state capacity building: The case of the Palestinian territories. J. Inst. Econ. 2015, 11, 823–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskova, M.; Blasko, R.; Kozubikova, Z.; Kozubik, A. Trust and reliability in building perfect university. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 205, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.O. Trust in Co-Operative Contracting in Construction; City University of Hong Kong Press: Hong Kong, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.S.P.; Cheung, S.O.; Yiu, T.W.; Pang, H.Y. A framework for trust in construction contracting. Int. J. Project Manag. 2008, 26, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, M.G.; Martinsson, P.; Matzata, D.; Wollbrant, C. The role of beliefs, trust, and risk in contributions to a public good. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 51, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D.; Weigert, A. Trust as a social reality. Soc. Forces 1985, 63, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect-And cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-George, C.; Swap, W. Measurement of specific interpersonal trust: Construction and validation of a scale to assess trust in a specific other. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur, A.; Leckie, C.; Webster, C.M. Cognitive and affective trust between Australian exporters and their overseas buyers. Australas. Market. J. 2012, 20, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.R.; Srivastava, A.; Goal, N.; Nayak, A.R. Building Rlexible Trust Models for E-Commerce Applications. 2006. Available online: http://tecsis.ca/services/2.Trust%20Model.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2016).

- Nicholson, C.Y.; Compeau, L.D.; Sethi, R. The role of interpersonal liking in building trust in long-term channel relationships. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2001, 29, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaojun, L.; Pickles, A.; Savage, M. Social capital and social trust in Britain. Eur. Social. Rev. 2005, 21, 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, R.J.; Stevenson, M.A. Trust development in negotiation: Proposed actions and a research agenda. Bus. Prof. Ethics J. 1997, 16, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorman, C.; Zaltman, G.; Deshpande, R. Relationship between providers and users of marketing research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J. Market. Res. 1992, 29, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Cvetkovich, G. Perception of hazards: The role of social trust and knowledge. Risk Anal. 2000, 20, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, J.; Kardia, S. Public trust in health information sharing: Implications for biobanking and electronic health record systems. J. Personal. Med. 2015, 5, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, C. Do Scientists Understand the Public? American Academy of Arts and Sciences: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D.; Weigert, J. The social dynamics of trust: Theoretical and empirical research. Soc. Forces 2012, 91, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ner, A.; Halldorsson, F. Trusting and Trustworthiness: What are they, how to measure them, and what affects them. J. Econ. Psychol. 2010, 31, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, R.; Javor, A. The biology of trust: Integrating evidence from genetics, endocrinology and functional brain imaging. J. Neurosci. Psychol. Econ. 2011, 5, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.; Kier, C.; Fung, T.; Fung, L.; Sproule, R. Searching for happiness: The importance of social capital. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibov, N.; Afandi, E. Pre- and post-crisis life-satisfaction and social trust in transitional countries: An initial assessment. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanone, M.A.; Kwon, K.H.; Lackaff, D. Exploring the relationship between perceptions of social capital and enacted support online. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2012, 17, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chua, V.; Stefanone, M.A. Social ties, communication channels, and personal well-being: A study of the networked lives of college students in Singapore. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.D. The Impact of Communication Impairments on the Social Relationships of Older Adults. Ph.D. Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 18 May 2015. Available online: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds/2344 (accessed on 3 January 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Mohnen, S.M.; Volker, B.; Flap, H.; Groenewegen, P.P. Health-Related behavior as a mechanism behind the relationship between neighborhood social capital and individual health: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberto, L.M.; Souza, R.K.T.; Eumann, M.A.; David, M.G.; Fernando, R.A. Relationship between social capital indicators and lifestyle in Brazilian adults. Cadernos de SaúdePública 2015, 31, 1636–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Aghdaie, S.F.A.; Piraman, A.; Fathi, S. An analysis of factors affecting the consumer’s attitude of trust and their impact on internet purchasing behavior. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Larysa, T.; Natalya, T. The impact of formal institutions on social trust formation: A social-cognitive approach. Munich Pers. RePEc Arch. 2014, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Adwere-Boamah, J. Predicting social trust with binary logistic regression. Res. Higher Educ. J. 2015, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwuedozie, K.A.; Patience, C.O. The Effects of rural-urban migration on rural communities of southeastern Nigeria. Int. J. Popul. Res. 2013, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cromartie, J.; Christiane, V.R.; Ryan, A. Factors Affecting Former Residents’ Returning to Rural Communities; U.S. Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Suthiwart-Narueput, S.; Charoenpanich, A. Eight Facts about Wages and Labor in Thailand and Their Implications for the Economy; (Advisor white paper); The Offices at Central World: Bangkok, Thailand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Gooby, P. Trust and welfare state reform: The example of the NHS. Soc. Policy Adm. 2008, 42, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pixley, J. Emotions in Finance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lahno, B. On the emotional character of trust. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2001, 4, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Variables | Questions/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Level of trust | Residents’ expectation of beneficial outcomes contributed by practices of the sufficiency economy philosophy | Would your quality of life be enhanced when conducting sufficiency economy activities? |

| Would your community environment be sustainably improved when conducting sufficiency economy activities? | ||

| Would society become more livable when conducting sufficiency economy activities? | ||

| Factors related to emotional-based trust | Level of relationship with community leaders | How frequently do you meet and have conversations with the leader? |

| Level of relationship with neighbors | How many neighbors do you have? | |

| Factors related to cognitive-based trust | Residents’ perception of the environmental quality improvement contributed by the practices of sufficiency economy philosophy | Do you think that having applied the sufficiency economy concept in daily life has yielded environmental improvement in the community? |

| Residents’ perception of household economic stability gained from the practices of sufficiency economy philosophy | Do you think that when conducting sufficiency economy activities, you have earned adequate income for future use in case you face unexpected events such illness, joblessness? | |

| Do you think that having applied sufficiency economy concept in daily life has contributed to adequate income for daily expenditure? | ||

| Residents’ perception of strengthened local cultures and traditions contributed by the practices of sufficiency economy philosophy. | Do you think that having applied the sufficiency economy concept in daily life has supported local culture and traditions? If so, how? | |

| Capability to adapt local wisdom for sufficiency economy activities. | Could you utilize local knowledge or local wisdom to operate sufficiency economy activities? | |

| Obstacles faced by residents when starting the practice such as insufficiency of budgets, lack of water resources, and poor quality of soil | Did you face any obstacles when you changed your lifestyles in accordance with self-sufficiency economy principles? | |

| Problems faced by residents during the practices such as plant disease or low quality and quantity of products | Do you think that applying sufficiency economy concepts in daily life could cause you some problems such as agricultural farm epidemics, or lack of market for agricultural goods? | |

| Characteristics of residents | Gender | Please indicate your gender |

| Career | What is your career? Open-ended question | |

| Educational level | What is your educational level? | |

| Open-ended question | ||

| Periods of living in the community | How long have you lived in the community? | |

| Open-ended question | ||

| Income | How much is your average income per month? |

| Sufficiency Economy Activities | Having Conducted | Have not Conducted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Doing integrated farming | 74 | 59.7 | 50 | 40.3 |

| Decreasing consumption of luxury goods | 50 | 40.3 | 74 | 59.7 |

| Balancing expenditures and incomes | 48 | 38.6 | 76 | 61.3 |

| Decreasing environmental degradation | 31 | 25.0 | 93 | 75.0 |

| Using local resources as a major source for living | 62 | 50.0 | 62 | 50.0 |

| Issues Related to Sustainability | Degree of Change (n/%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significantly Better | Better | Same | Worse Than Before | |

| Improvement of Environmental Quality | 74 (59.68%) | 36 (29.03%) | 10 (8.06%) | 4 (3.23%) |

| Enhancement of Community Relations | 94 (75.81%) | 18 (14.52%) | 10 (8.06%) | 2 (1.61%) |

| Enhancement of Relationship in Family | 73 (58.87%) | 40 (32.26%) | 11 (8.87%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Enhancement of Local Cultures | 65 (52.42%) | 28 (22.58%) | 28 (22.58%) | 3 (2.42%) |

| Adequate Incomes for Daily Expenditures | 36 (29.03%) | 70 (56.45%) | 18 (14.52%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Variables | Mean ± SD | N (%) | Correlation with CT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Trust (CT) | Community Trust (CT) | 3.69 ± 0.49 | - | 1.00 | |

| Emotional-based trust factors | Relationship with community leaders | 3.26 ± 0.82 | - | 0.25 | |

| Relationship with neighbors | 4.89 ± 0.31 | - | 0.17 | ||

| Cognitive-based trust factors | Perception of the environmental quality improvement | 0.21 | |||

| No improvement | - | 8 (6.45%) | |||

| Partially improved | - | 34 (28.33%) | |||

| Significantly improved | - | 82 (66.13%) | |||

| Perception of household financial security | 2.96 ± 0.73 | - | 0.60 | ||

| Perception of balance between incomes and expenditure | 3.19 ± 0.65 | - | 0.21 | ||

| Perception of enhanced local cultures and traditions | 0.37 | ||||

| No enhancement | - | 29 (23.40%) | |||

| Enhancement | - | 95 (76.60%) | |||

| Capability to adapt local wisdom for sufficiency economy activities | 3.28 ± 0.76 | - | 0.33 | ||

| Obstacles faced by residents when starting the practices | 0.22 | ||||

| Many | - | 4 (3.20%) | |||

| Moderate | - | 56 (45.20%) | |||

| Less | - | 64 (51.60%) | |||

| Problems faced by residents during the practices | 0.44 | ||||

| Have | - | 28 (22.60%) | |||

| Not have | - | 96 (77.40%) | |||

| Demographic characteristics | Gender | 0.13 | |||

| Male | - | 75 (60.50%) | |||

| Female | - | 49 (39.50%) | |||

| Career | −0.19 | ||||

| Gardener | - | 66 (53.20%) | |||

| Merchant | - | 20 (16.10%) | |||

| Teacher | - | 6 (4.80%) | |||

| Laborer | - | 25 (20.20%) | |||

| Officer | - | 7 (5.60%) | |||

| Educational level | 0.18 | ||||

| Primary School | - | 65(52.40%) | |||

| Junior High School | - | 28(22.60%) | |||

| Senior High School | - | 13(10.50%) | |||

| Bachelor Degree | - | 18(14.50%) | |||

| Period of time in the community | 0.41 | ||||

| 10–20 years | - | 15 (12.10%) | |||

| 21–30 years | - | 17 (13.70%) | |||

| 31–40 years | - | 19 (15.30%) | |||

| more than 40 years | - | 73 (58.90%) | |||

| Income | - | 12,739 ± 9121 | 0.11 | ||

| Variables | Liner Regression Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | t | VIF | ||

| Emotional-based trust factors | Relationship with community leaders | 0.094 | 0.045 | 0.165 | 2.388 * | 2.065 |

| Relationship with neighbors | 0.122 | 0.160 | 0.075 | 0.761 | 3.484 | |

| Cognitive-based trust factors | Perception of the environmental quality improvement | −0.120 | 0.111 | −0.093 | −1.085 | 2.420 |

| Perception of household financial security | 0.257 | 0.057 | 0.376 | 4.495 ** | 2.448 | |

| Perception of balance between incomes and expenditure | −0.108 | 0.051 | −0.143 | −1.765 | 2.532 | |

| Perception of enhanced local cultures and traditions | −0.079 | 0.083 | 0.068 | -0.950 | 1.638 | |

| Capability to adapt local wisdom for sufficiency economy activities | 0.101 | 0.036 | 0.276 | 2.793 ** | 1.334 | |

| Obstacles faced by residents when starting the practice | 0.127 | 0.057 | 0.144 | 0.906 | 1.408 | |

| Problems faced by residents during the practices | 0.518 | 0.080 | 0.438 | 6.513 ** | 1.496 | |

| Demographic characteristics | Gender | −0.220 | 0.094 | −0.217 | −2.344 * | 2.843 |

| Career | 0.029 | 0.028 | 0.081 | 1.034 | 2.048 | |

| Educational level | 0.050 | 0.032 | 0.133 | 1.894 | 1.625 | |

| Period of time in the community | 0.230 | 0.040 | 0.502 | 5.774 ** | 2.505 | |

| Income | 8.090 × 10 −6 | 0.000 | 0.141 | 1.777 | 2.073 | |

| R2 | 0.670 | |||||

| Adjust R2 | 0.62.80 | |||||

| F | 15.841 | |||||

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janmaimool, P.; Denpaiboon, C. Rural Villagers’ Quality of Life Improvement by Economic Self-Reliance Practices and Trust in the Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy. Societies 2016, 6, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030026

Janmaimool P, Denpaiboon C. Rural Villagers’ Quality of Life Improvement by Economic Self-Reliance Practices and Trust in the Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy. Societies. 2016; 6(3):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030026

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanmaimool, Piyapong, and Chaweewan Denpaiboon. 2016. "Rural Villagers’ Quality of Life Improvement by Economic Self-Reliance Practices and Trust in the Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy" Societies 6, no. 3: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030026

APA StyleJanmaimool, P., & Denpaiboon, C. (2016). Rural Villagers’ Quality of Life Improvement by Economic Self-Reliance Practices and Trust in the Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy. Societies, 6(3), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030026