The Influence of Context on Occupational Selection in Sport-for-Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Contextual Background Information

1.1.1. Kicking AIDS Out

1.1.2. Zambia

1.1.3. Trinidad and Tobago

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

- How do you choose/decide which activities to use in programming?

- How do local customs and traditions influence program activities?

- Are there particular activities that you favour/prefer to use in programming?

- What other activities do you think could be used to achieve your program aims?

- Tell me about the knowledge and skills you have that are related to the program activities.

- Have program youth suggested changes to you regarding the program activities?

2.3. Data

2.4. Analysis

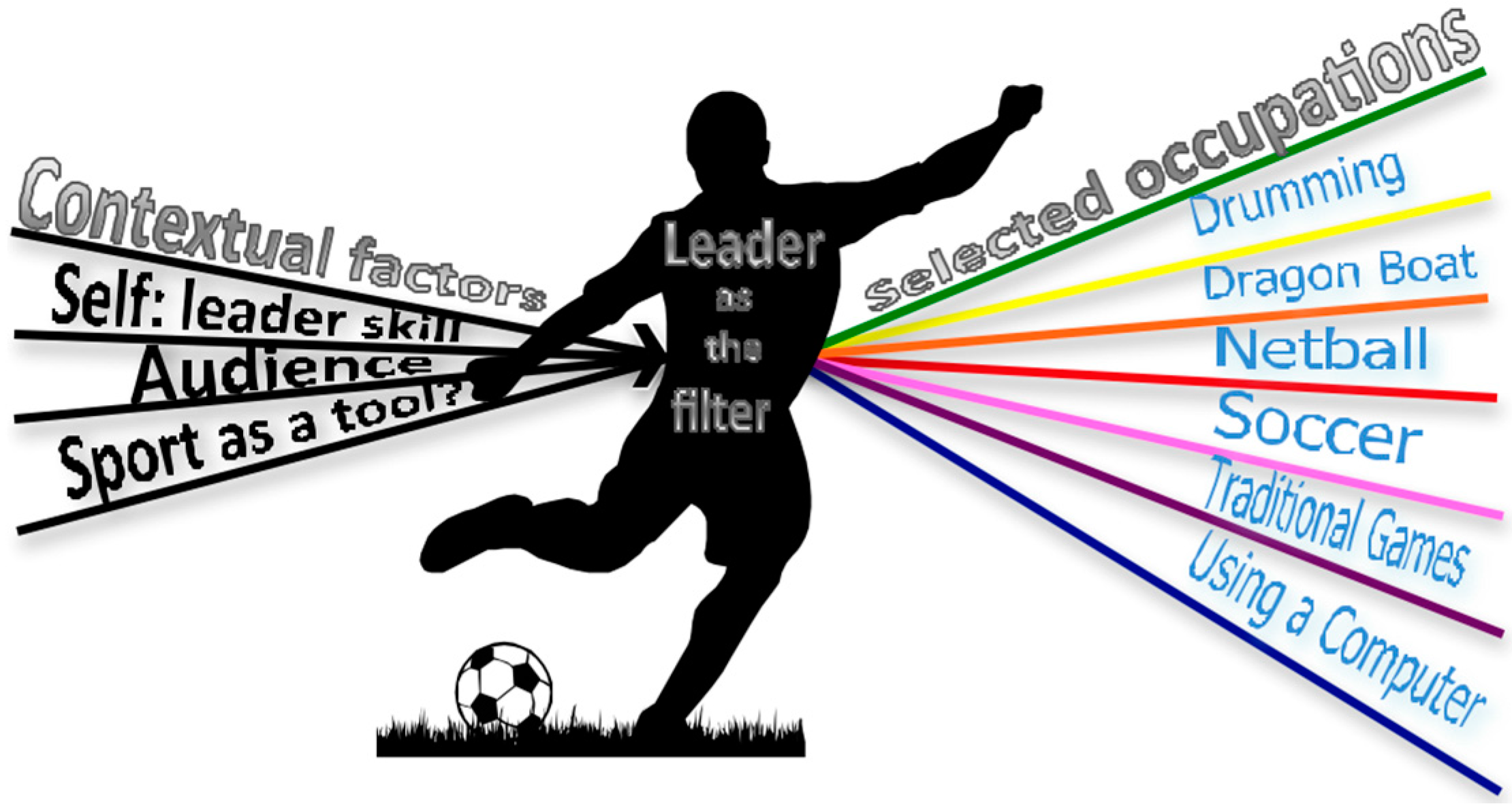

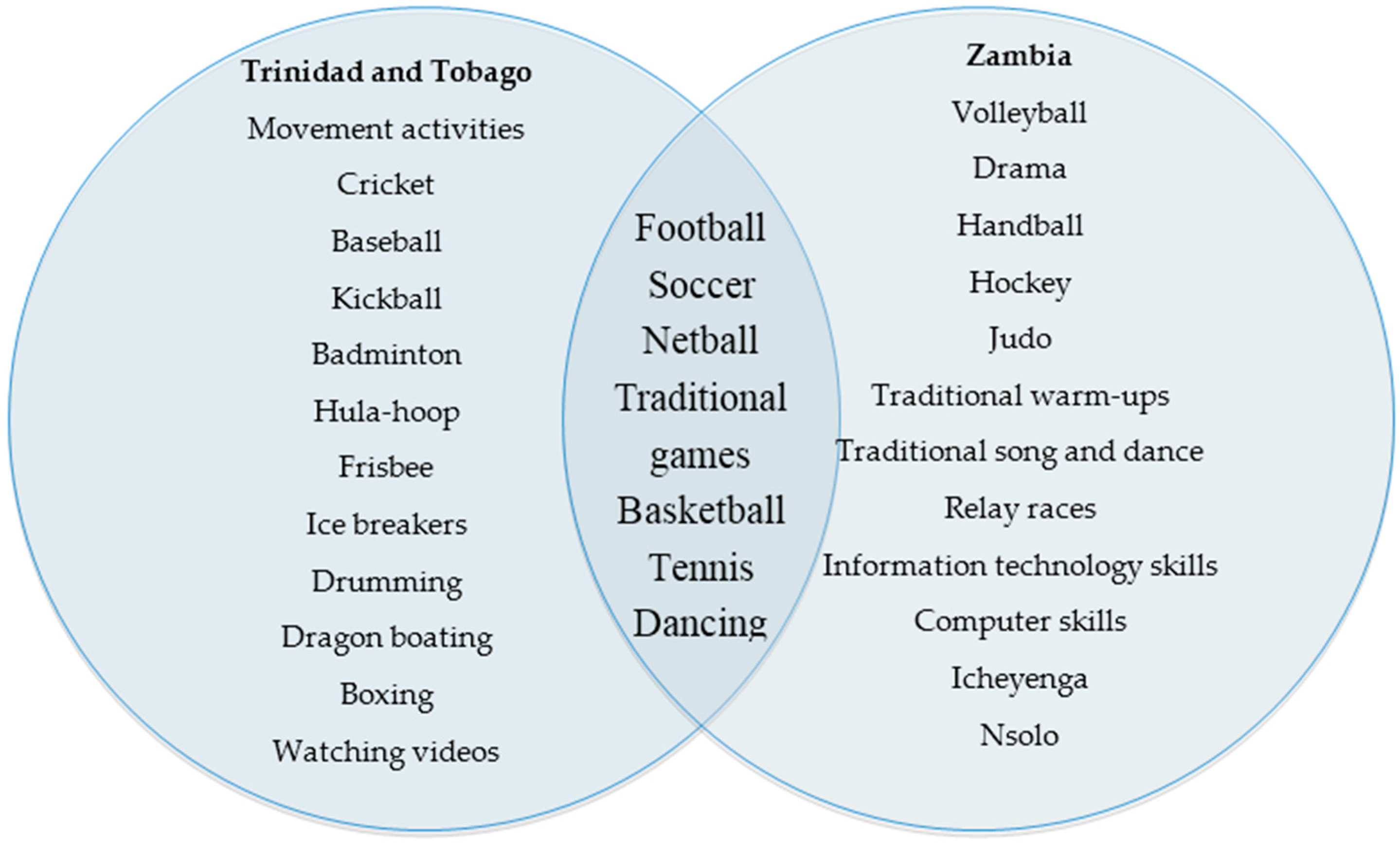

3. Results

3.1. Balancing the Audience and the Self

…so we work with whatever people like to do, and then we add our approach to it… but if the people are already there, work with what they have and then introduce sport to them and in a fun way…again working with their desire.(male, Trinidad and Tobago)

3.2. Sport as a Tool, a Tool for What?

...sport-for-development is really using sport as a medium, as a tool, as a vehicle, to help develop people.... and by extension communities um by developing positive social behaviours and positive values.(male, Trinidad & Tobago)

...here we already had a program for young people that was supposed to be sport oriented but mostly looked at speaking skills… it kind of moved away from sport um but now Kicking AIDS Out brought it back, brought that movement element …which was a great thing.(male, Trinidad and Tobago)

“…we (Zambian’s) appreciate the aspect of personal and economical development through sports, firstly, it enhances social change in an economical aspect and also in the social aspect and development of the use of sport as a tool”.(male, Zambia)

“Football becomes a powerful tool… if these young people work hard using sports they are able to feed their families because they create a career as a result of that…In Zambia the career development for example in music is not as lucrative as it is in sports”.(male, Zambia)

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of the Leaders in Selecting Occupations

4.2. Occupations Used to Achieve Context Specific Development Goals

…authors point to the capacity of local actors to contextualize, reinterpret, resist, subvert and transform international development agendas which, in turn, contributes to a diverse array of development practices emerging within local contexts.

4.3. Limitations of Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| SFD | sport-for-development |

| KAO | Kicking AIDS Out |

References

- Human Development Report 2002: Deepening Democracy in a Fragmented World. United Nations Development Programme. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2002/ (accessed on 18 June 2013).

- Njelesani, J.; Cameron, D.; Polatajko, H.J. Occupation-for-development: Expanding the boundaries of occupational science into the international development agenda. J. Occup. Sci. 2012, 19, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.R. The ambiguities of development: Implications for ‘development through sport’. Sport Soc. 2010, 13, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levermore, R. Sport: A new engine of development? Prog. Dev. Stud. 2008, 8, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, S.E. Review of Kicking AIDS Out: Is Sport an Effective Tool in the Fight against HIV/AIDS? Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation: Oslo, Norway, 2007; Available online: http://www.norad.no/en/tools-and-publications/publications/publication?key=109688 (accessed on 18 June 2013).

- Coalter, F. The politics of sport-for-development: Limited focus programmes and broad gauge problems? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2010, 45, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaanga, O. Sport for Addressing HIV/AIDS: Explaining Our Convictions; Leisure Studies Association Newsletter: Bolton, UK, 2010; Volume 85, pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, P.; Atkinson, M.; Boyle, S.; Szto, C. Sport for development and peace: A public sociology perspective. Third World Q. 2011, 32, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, I.; Banda, D. Sport and the fight against HIV/AIDS in Zambia: A ‘partnership approach’? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2010, 46, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, I.; Grattan, A. An ‘international movement’? Decentring sport-for-development within Zambian communities. Int. J. Sport Policy 2012, 4, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.; Giles, A.R.; Sethna, C. Perpetuating the ‘lack of evidence’ discourse in sport for development: Privileged voices, unheard stories and subjugated knowledge. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2011, 46, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalter, F.; Taylor, J. Sport-for-Development Impact Study: A Research Initiativefunded by Comic Relief and UK Sport and Managed by International Development through Sport; University of Stirling: Stirling, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Njelesani, J.; Tang, A.; Jonsson, H.; Polatajko, H. Articulating an occupational perspective. J. Occup. Sci. 2012, 21, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, E.; Polatajko, H.J. Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-Being & Justice through Occupation, 2nd ed.; Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kicking AIDS out. History. 2009. Available online: http://www.kickingaidsout.net/WhatisKickingAIDSOut/Pages/History.aspx (accessed on 12 June 2013).

- Kicking AIDS out. The Network. 2009. Available online: http://www.kickingaidsout.net/WhatisKickingAIDSOut/Pages/TheNetwork.aspx (accessed on 10 June 2013).

- Central Statistical Office Republic of Zambia. Zambia 2010 Census of Population and Housing; Central Statistical Office: Lusaka, Zambia, 2011; pp. 1–66.

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook—Zambia 2013. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/za.html (accessed on 4 June 2013).

- Njelesani, J. Examining Sport-for-Development Using a Critical Occupational Approach to Research. Ph.D. Dissertation, Graduate Department of Rehabilitation Science University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Country and Lending Groups 2013. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 4 June 2013).

- Africa Region Poverty Reduction and Economic Management. Zambia Economic Brief: Recent Economic Developments and the State of Basic Human Opportunities for Children; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 74382, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations AIDS (UNAIDS). Zambia. 2011. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/zambia/ (accessed on 18 June 2013).

- Joffe, H.; Bettega, N. Social representation of AIDS among Zambian adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations AIDS (UNAIDS). Zambia Country Progress Report. 2015. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/ZMB_narrative_report_2015.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2016).

- Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. Central Statistical Office 2012. Available online: http://www.cso.gov.tt (accessed on 18 June 2013).

- ICON International Group. Trinidad and Tobago Economic Studies; ICON International Group: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook—Trinidad & Tobago 2013. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/td.html (accessed on 4 June 2013).

- Brereton, B. History of Modern Trinidad 1783–1962; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Political Risk Yearbook. In Trinidad and Tobago Country Report; PRS Group Inc.: East Syracuse, NY, USA, 2013.

- Voisin, D.; Baptiste, D.; Martinez, D.; Henderson, G. Exporting a US HIV/AIDS prevention program to a Caribbean island-nation. Int. Soc. Work 2006, 49, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Country Cooperation Strategy at a Glance—Trinidad and Tobago; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 7, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, L.M. Secondary analysis. MEDSURG Nurs. 2010, 19, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, P.S.; Vogel, R.J.; Clarke-Steffen, L. The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qual. Health Res. 1997, 7, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePoy, E.; Gitlin, L.N. Introduction to Research: Understanding and Applying Multiple Strategies; Elsevier/Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Njelesani, J.; Cameron, D.; Gibson, B.E.; Nixon, S.; Polatajko, H. A critical occupational approach: Offering insights on the sport-for-development playing field. Sport Soc. 2014, 17, 790–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangrar, R.; Vaisberg, S.; Njelesani, J.; Polatajko, H. Sport activities as a vehicle for HIV/AIDS prevention in Trinidad And Tobago: Organizer’s perspectives. J. Clin. Res. HIV AIDS Prev. 2014, 1, 2324–7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B.C. Sport as an agent for social and personal change. In Management of Sport Development; Girginov, V., Ed.; Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanes, R. Educating through sport? Examining HIV/AIDS education and sport-for-development through the perspectives of Zambian young people. Sport Educ. Soc. 2011, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaanga, O. Kicking AIDS out through Movement Games and Sports Activities; Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation: Oslo, Norway, 2002; Available online: http://www.sportanddev.org/en/toolkit/manuals_and_tools/?13/1/Kicking-AIDS-Out-Through-Movement-Games-and-Sports-Activities (accessed on 4 June 2013).

- Kicking AIDS out. Kicking AIDS out Curriculum Review and Development. 2009. Available online: http://www.kickingaidsout.net/WhatisKickingAIDSOut/Pages/TrainingCurriculum.aspx (accessed on 14 June 2013).

- Pawson, R. Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective; SAGE: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Long, N. Development Sociology: Actor Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scheurkens, U. The sociological and anthropological study of globalization and localization. Curr. Sociol. 2003, 3, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Dilemmas of development and the environment in a globalizing world: Theory, policy and praxis. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2003, 3, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Separated by common ground? Bringing (post)development and (post)colonialism together. Geogr. J. 2006, 172, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.S. The crucible of cultural politics: Reworking “development” in Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands. Am. Ethnol. 1999, 16, 654–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Statistics Division. Zambia. 2013. Available online: http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=ZAMBIA (accessed on 10 June 2013).

- Coalter, F. Sport-in-development: Accountability or development? In Sport and International Development; Levermore, R., Beacom, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, D.; Kwauk, C. Sport and development: An overview, critique, and reconstruction. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2011, 35, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lusaka, Zambia | Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leader | Gender | Age | Time with KAO | Leader | Gender | Age | Time with KAO |

| 1 | Female | 25 | 2 months | 1 | Female | Unknown | 1 year |

| 2 | Male | 26 | 5 years | 2 | Female | 22 | 3 years |

| 3 | Male | 19 | 7 years | 3 | Male | 41 | 8 years |

| 4 | Female | 54 | 13 years | 4 | Male | Unknown | 8 years |

| 5 | Male | 32 | 8 years | 5 | Male | 28 | Unknown |

| 6 | Male | 41 | Unknown | 6 | Male | 30 | 3 years |

| 7 | Male | 22 | 6 months | ||||

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Njelesani, J.; Fehlings, L.; Tsang, A.; Polatajko, H. The Influence of Context on Occupational Selection in Sport-for-Development. Societies 2016, 6, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030024

Njelesani J, Fehlings L, Tsang A, Polatajko H. The Influence of Context on Occupational Selection in Sport-for-Development. Societies. 2016; 6(3):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030024

Chicago/Turabian StyleNjelesani, Janet, Lauren Fehlings, Amie Tsang, and Helene Polatajko. 2016. "The Influence of Context on Occupational Selection in Sport-for-Development" Societies 6, no. 3: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030024

APA StyleNjelesani, J., Fehlings, L., Tsang, A., & Polatajko, H. (2016). The Influence of Context on Occupational Selection in Sport-for-Development. Societies, 6(3), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030024